Abstract

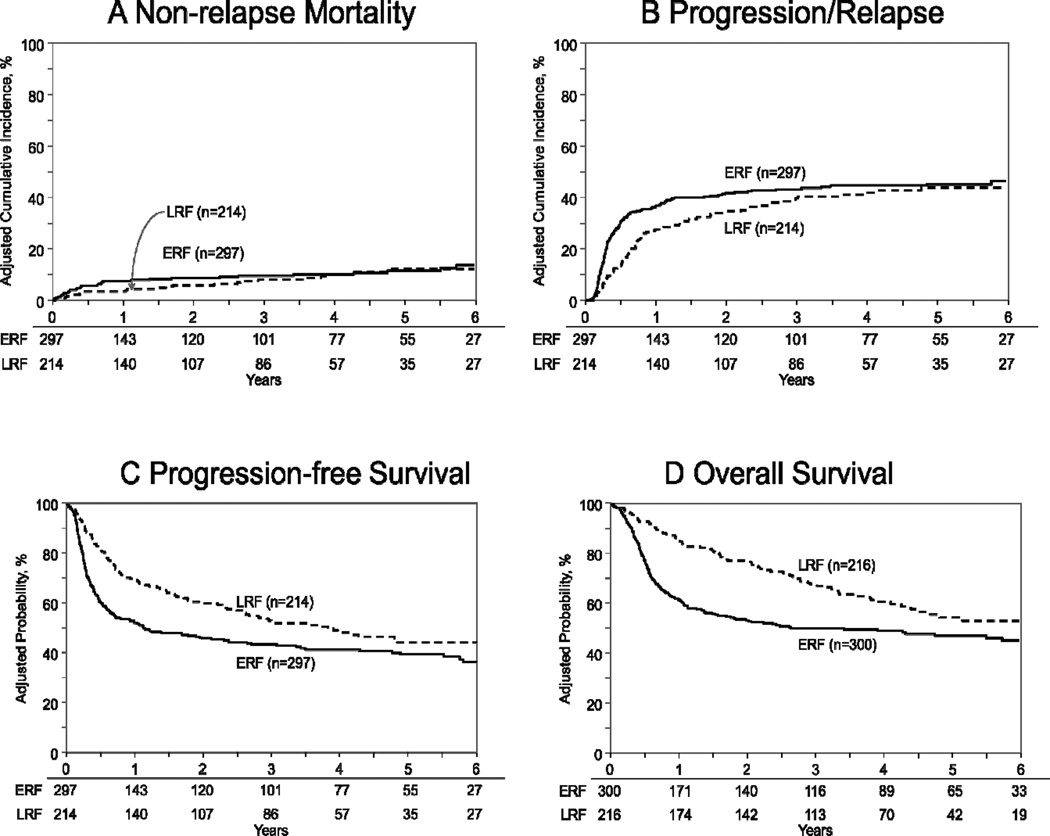

The poor prognosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients relapsing within 1-year of initial diagnosis after first-line rituximab-based chemoimmunotherapy has created controversy about the role of autologous transplantation (auto-HCT) in this setting. We compared auto-HCT outcomes of chemosensitive DLBCL patients between 2000 and 2011 in two cohorts based on time to relapse from diagnosis. The early rituximab failure (ERF) cohort consisted of patients with primary refractory disease or those with first relapse within 1-year of initial diagnosis. The ERF cohort was compared with those relapsing >1-year after initial diagnosis (Late Rituximab Failure [LRF] cohort). ERF and LRF cohorts included 300 and 216 patients, respectively. Non-relapse mortality (NRM), progression/relapse, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of ERF vs. LRF cohorts at 3-years were 9% (95%CI 6–13) vs. 9% (95%CI 5–13), 47% (95%CI 41–52) vs. 39% (95%CI 33–46), 44% (95%CI 38–50) vs. 52% (95%CI 45–59) and 50% (95 CI 44–56) vs. 67% (95%CI 60–74), respectively. On multivariate analysis, ERF was not associated with higher NRM (relative risk (RR) 1.31, p=0.34). ERF cohort had a higher risk of treatment failure (progression/relapse or death) (RR 2.08, p<0.001) and overall mortality (RR 3.75, p<0.001) within the first 9 months post auto-HCT. Beyond this period, PFS and OS were not significantly different between ERF and LRF cohorts. Auto-HCT provides durable disease control to a sizeable subset of DLBCL despite ERF (3-year PFS 44%), and remains the standard-of-care in chemosensitive DLBCL regardless of the timing of disease relapse.

Keywords: Autologous transplantation, rituximab, early failure, high dose therapy, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, aggressive lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

High dose therapy (HDT) and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is the treatment of choice for patients with relapsed chemosensitive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and appears to be curative for 40–45% of the patients [1–3]. The incorporation of rituximab in the first line chemotherapy has significantly improved survival outcomes of both elderly and younger DLBCL patients [4–7]. However, despite modern chemo-immunotherapies, some patients still do not achieve complete remission ([CR] induction failure), or relapse after the initial chemotherapy [8].

Autologous HCT is frequently considered for patients with primary refractory DLBCL (i.e. patients not achieving a CR after first-line therapies). Registry data from the pre-rituximab era [9], suggested that such high-risk primary refractory DLBCL patients can achieve durable disease control with HDT and autologous HCT, provided they demonstrate evidence of chemosensitive disease following pre-transplant salvage therapies (5-year progression-free survival [PFS] and overall survival [OS] of 31% and 37%, respectively). These data [1,2,9] derived mainly before the advent of chemo-immunotherapies, form the basis of current clinical practice of considering HDT in relapsed chemosensitive DLBCL patients, including those with primary refractory disease. However, the validity of this paradigm in patients treated with rituximab-based first line chemoimmunotherapies has come under recent scrutiny, owing largely to observations made in the CORAL (Collaborative Trial in Relapsed Aggressive Lymphoma) study [8,10]. The CORAL trial [11] data, while in general supporting the role of autologous HCT in relapsed chemosensitive DLBCL, identified a subset of high-risk patients (i.e. ones treated with rituximab-based first line chemoimmunotherapies and either not achieving CR or experiencing a relapse within a year of initial diagnosis) with an extremely poor prognosis with standard salvage approaches (3-year PFS of ~20%) [11]. The disappointing outcomes of DLBCL patients experiencing early rituximab failure (ERF) in this study, have led several groups to question the utility of HDT in this particular setting [10]. We therefore utilized the observational database of Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) to evaluate the role of autologous HCT in DLBCL patients experiencing ERF (defined as DLBCL patients treated with rituximab-based 1st line chemo-immunotherapies who either had primary refractory disease or relapsed within 1-year of initial diagnosis), relative to the outcomes of patients receiving first line rituximab-based therapies and relapsing >12months after initial diagnosis (Late Rituximab Failure [LRF]).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources

The CIBMTR is a working group of more than 450 transplantation centers worldwide that contribute detailed data on HCTs to a statistical center at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Centers report HCTs consecutively, with compliance monitored by on-site audits. Patients are followed longitudinally with yearly follow-up. Observational studies by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with federal regulations with ongoing review by the institutional review board of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Patients

The study population included all patients with a histologically proven diagnosis of DLBCL treated with rituximab-based first line chemo-immunotherapies, who underwent an autologous HCT reported to the CIBMTR between 2000 and 2011. Patients not responding (i.e. patients not achieving a CR or partial remission [PR]) to the last salvage chemotherapy prior to autologous HCT were excluded (n=58). Pediatric patients (age <18 year, n=2), DLBCL representing transformation from indolent histologies (n=18) and those receiving bone marrow grafts (n=9) were not included in the analysis. DLBCL patients achieving a CR with first line rituximab-containing therapies and then undergoing upfront autologous HCT consolidation, without ever experiencing rituximab-failure were also excluded (n=52). ERF group consisted of: a) DLBCL patients with primary refractory disease after rituximab-based 1st chemo-immunotherapies (but eventually undergoing autologous HCT with chemosensitive disease) and b) patients who received rituximab-based first line chemo-immunotherapies and then relapsed within 12-months of initial diagnosis. LRF consisted of all other patients with chemosensitive disease at transplant, receiving rituximab-containing first line chemoimmunotherapies and then relapsing beyond 12 months from initial diagnosis.

Study Endpoints

CR to salvage therapies was defined as complete resolution of all known disease on radiographic (CAT-scan) assessments, while CR undetermined (CRu) represented patients meeting CR criteria with persistent scan abnormalities of unknown significance. PR required ≥ 50% reduction in the greatest diameter of all sites of known disease and no evidence of disease progression. Primary outcomes were non-relapse mortality (NRM), progression/relapse, PFS and OS. NRM was defined as death from any cause during the first 28 days after transplantation or death without evidence of lymphoma progression/relapse; relapse was considered a competing risk. Progression/relapse was defined as progressive lymphoma after HCT or lymphoma recurrence after a CR; NRM was considered a competing risk. For PFS, a patient was considered a treatment failure at the time of progression/relapse or death from any cause. For relapse, NRM, and PFS patients alive without evidence of disease relapse or progression were censored at last follow-up. The OS was defined as the interval from the date of transplantation to the date of death or last follow-up. Neutrophil recovery was defined as the first of 3 successive days with absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 500/µL after post-transplantation nadir. Platelet recovery was considered to have occurred on the first of three consecutive days with platelet count 20,000/µL or higher, in the absence of platelet transfusion for 7 consecutive days. For neutrophil and platelet recovery, death without the event was considered a competing risk.

Statistical analysis

Probabilities of PFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator with variance estimated by the Greenwood formula. Probabilities of NRM, lymphoma progression/relapse, and hematopoietic recovery were calculated using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate for competing risks (25). Patient-, disease- and transplant- related factors were compared between ERF and LRF groups using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon two sample test for continuous variables. Associations among patient-, disease, and transplantation-related variables and outcomes of interest were evaluated using multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression. A stepwise selection multivariate model was built to identify covariates that influenced outcomes. Covariates with a p-value <0.05 were considered significant. The proportionality assumption for Cox regression was tested by adding a time-dependent covariate for each risk factor and each outcome. Covariates violating the proportional hazards assumption were stratified in the Cox regression model. Results are expressed as relative risk (RR) or the relative rate of occurrence of the event.

The variables considered in multivariate analysis included ERF vs. LRF (the main effect), age (considered as continuous and categorical), Karnofsky performance status (KPS) at transplant, disease stage at diagnosis, age-adjusted international prognostic index (aaIPI) at the pre-HCT time point, LDH at diagnosis, number of lines of chemotherapies prior to HCT, extranodal involvement at any time prior to HCT, bone marrow involvement at any time prior to HCT, prior history of radiation therapy, remission status at HCT (CR vs. PR) and HCT conditioning regimens. The potential interactions between main effect and all significant covariates were tested and no interaction was detected.

RESULTS

Patient, Disease-, and Transplant-Related Variables

Between 2000 and 2011, 516 DLBCL patients receiving rituximab-containing frontline chemo-immunotherapies underwent autologous HCT. 300 patients are included in the ERF group, while 216 constitute the LRF cohort. 150 patients included in the ERF group had primary refractory disease (Table 1), while an additional 150 patients experienced relapse within 12 months from initial diagnosis. Median follow up of survivors for ERF and LRF groups was 48 months and 47 months, respectively. Completeness of follow up at 3 years was 88% in both groups (26) [12].

Table 1.

Characteristics of ≥ 18 years old patients who underwent autologous transplantation for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma after rituximab-containing first line chemoimmunotherapy from 2000–2011 reported to the CIBMTR

| Variable | Early Rituximab Failure |

Late Rituximab Failure |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 300 | 216 | |

| Age at transplant | 0.004 | ||

| Median (range) | 58 (19–77) | 62 (20–76) | |

| 18–29 years | 16 ( 5) | 2 ( 1) | |

| 30–39 years | 18 ( 6) | 10 ( 5) | |

| 40–49 years | 48 (16) | 29 (13) | |

| 50–59 years | 84 (28) | 47 (22) | |

| ≥60 years | 134 (45) | 128 (59) | |

| Male Sex | 189 (63) | 129(60) | 0.450 |

| Karnofsky performance score | 0.257 | ||

| <90% | 95 (32) | 54 (25) | |

| 90–100% | 185 (62) | 146 (68) | |

| Missing | 20 ( 7) | 16 ( 7) | |

| Doxorubicin containing 1st line chemotherapy | 277(92) | 204(94) | 0.215 |

| Kinetics of relapse | N/A | ||

| Primary refractory disease (primary induction failure)* | 150 (50) | 0 | |

| ≤12m from diagnosis to initial relapse (early failure) | 150 (50) | 0 | |

| All others (late failure) | 0 | 216 | |

| Rituximab received with 2nd line chemotherapy | 187 (62) | 153 (71) | 0.045 |

| Time from diagnosis to initial relapse, months | <0.001 | ||

| Median (range) | 8 (<1–12) | 24 (12–125) | |

| Disease stage at diagnosis | 0.150 | ||

| I–II | 60 (20) | 59 (27) | |

| III–IV | 219 (73) | 143 (66) | |

| Unknown | 21 ( 7) | 14 ( 6) | |

| Disease status pre-HCT | <0.001 | ||

| PR | 199 (66) | 68 (31) | |

| CR | 101 (34) | 148 (69) | |

| Age-adjusted IPI score (pre-HCT) | 0.001 | ||

| Low | 145 (52) | 135 (68) | |

| Low-Intermediate | 111 (40) | 56 (28) | |

| High-Intermediate | 25 ( 9) | 6 ( 3) | |

| High | 0 | 1 ( 1) | |

| Missing | 19 | 18 | |

| History of bulky disease | 29 (10) | 10 (5) | <0.001 |

| Number of patients | 300 | 216 | |

| B Symptoms at diagnosis | 110(37) | 85(39) | 0.824 |

| LDH elevated at diagnosis | 83(28) | 48(22) | 0.324 |

| Unknown | 179 (60) | 135 (63) | |

| LDH elevated at transplant | 110(37) | 59(27) | 0.069 |

| Unknown | 34 (11) | 32 (15) | |

| Total number of chemotherapy lines | 0.526 | ||

| Median (range) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (2–4) | |

| ≤2 | 161 (54) | 122 (56) | |

| >2 | 139 (46) | 94 (44) | |

| Extranodal involvement at any time prior to HCT | 198 (66) | 140 (65) | 0.488 |

| CNS involvement at any time prior to HCT | 12 (4) | 7 (3) | 0.452 |

| Bone marrow involvement at any time prior to HCT | 44 (15) | 44 (20) | 0.192 |

| Missing | 111 (37) | 80 (37) | |

| Radiation prior to HCT | 102 (34) | 65 (30) | 0.349 |

| Conditioning regimen | 0.488 | ||

| TBI-based-without R | 33 (11) | 15 ( 7) | |

| BEAM*** and similar-with R | 48 (16) | 40 (19) | |

| BEAM*** and similar-without R | 171 (57) | 125 (58) | |

| CBV or similar-with R | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| CBV or similar-without R | 34 (11) | 26 (12) | |

| BuMEL/BuCy-with R | 0 | 2 ( 1) | |

| BuMEL/BuCy-without R | 9 ( 3) | 6 ( 3) | |

| Others-without R**** | 4 ( 1) | 2 ( 1) | |

| Year of transplant | 0.680 | ||

| 2000 | 3 ( 1) | 0 | |

| 2001 | 4 ( 1) | 3 ( 1) | |

| 2002 | 11 ( 4) | 8 ( 4) | |

| 2003 | 11 ( 4) | 7 ( 3) | |

| 2004 | 23 ( 8) | 13 ( 6) | |

| 2005 | 36 (12) | 14 ( 6) | |

| 2006 | 46 (15) | 36 (17) | |

| 2007 | 45 (15) | 35 (16) | |

| 2008 | 70 (23) | 54 (25) | |

| 2009 | 31 (10) | 27 (13) | |

| 2010 | 9 ( 3) | 9 ( 4) | |

| 2011 | 11 ( 4) | 10 ( 5) | |

| Median follow up of survivors, months | 48 (3–147) | 47 (3–126) |

Abbreviations: BuMel=busulfan and melphalan; BuCy=busulfan and cyclophosphamide; CNS=central nervous system; CR=complete remission; ERF=early rituximab failure; HCT=hematopoietic cell transplantation; aaIPI=age adjusted international prognostic index; LDH=lactate dehydrogenase; LRF=late rituximab failure; PR=partial remission; R=rituximab; TBI=total body irradiation,

Primary refractory disease includes 23 patients with non-response (or stable disease) to 1st line therapy, 28 patients with progressive disease after 1st line therapy and 99 patients not achieving a CR following 1st line therapy (i.e. primary induction failure-sensitive patient).

BEAM and similar includes combination of BCNU or cyclophosphamide or etoposide or melphalan or cytarabine.

Others: Early failure: carboplatin+thiotepa+etoposide (n=3); melphalan only (n=1). Late failure: melphalan only (n=1), melphalan+mitoxanterone (n=1).

Table 1 describes patient-, disease- and transplant related characteristics of two cohorts analyzed. No significant difference at baseline was observed between the two groups in terms of patient gender, KPS, disease stage at diagnosis, LDH level, bone marrow or extranodal involvement, history of central nervous system involvement, doxorubicin use in the frontline setting, total lines of therapies pre-HCT, prior radiation therapy and types of HCT conditioning regimens. Median age was significantly different between the two cohorts (median age ERF 58 years vs. LRF 62 years; p=0.004). Compared to ERF, significantly more patients in the LRF cohort had low pre-HCT aaIPI score (52% vs. 68%; p=0.001) received rituximab-containing salvage (62% vs. 71%; p=0.045) and were in CR at the time of HCT (34% vs. 69%; p<0.001).

Hematopoietic recovery

The cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery at day +28 was 100% (95% CI 97–100) for both ERF and LRF cohorts (p=0.82) (Table 2). The cumulative incidence of platelet recovery at day +28 for ERF and LRF groups was 82% (95% CI 77–86) and 85% (95% CI 79–89) (p=0.39), respectively.

Table 2.

Outcomes after autologous transplant.

| Outcomes | Early Rituximab Failure N Prob (95%CI) |

Late Rituximab Failure N Prob (95%CI) |

Univariate P- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANC≥0.5 × 109/L | 300 | 216 | |

| @ 28 days | 100 (97–100) | 100 (97–100) | 0.823 |

| Platelet ≥ 20 × 109/L | 293 | 212 | |

| @ 28 days | 82 (77–86) | 85 (79–89) | 0.394 |

| @ 100 days | 94 (90–96) | 98 (94–99) | 0.022 |

| NRM | 297 | 214 | |

| @ 1 year | 7 (5–11) | 4 (2–7) | 0.064 |

| @ 3 years | 9 (6–13) | 9 (5–13) | 0.795 |

| @ 5 years | 11 (8–16) | 13 (8–19) | 0.616 |

| Progression/Relapse | 297 | 214 | |

| @ 1 year | 40 (34–45) | 27 (21–33) | 0.003 |

| @ 3 years | 47 (41–52) | 39 (33–46) | 0.109 |

| @ 5 years | 49 (43–55) | 43 (36–51) | 0.258 |

| PFS | 297 | 214 | |

| @ 1 year | 53 (47–58) | 69 (62–75) | 0.001 |

| @ 3 years | 44 (38–50) | 52 (45–59) | 0.085 |

| @ 5 years | 40 (34–46) | 44 (36–51) | 0.449 |

| Overall survival | 300 | 216 | |

| @ 1 year | 62 (56–67) | 85 (80–89) | <0.001 |

| @ 3 years | 50 (44–56) | 67 (60–74) | <0.001 |

| @ 5 years | 47 (41–53) | 54 (46–62) | 0.179 |

Abbreviations: ANC = absolute neutrophil count; NRM = non-relapse mortality; PFS = progression-free survival; PROB = probability; CI = confidence interval.

Non-relapse mortality

Cumulative incidence of 3-years NRM was similar at 9% (95% CI 6–13) for the ERF cohort and 9% (95% CI 5–13) for the LRF cohort (p=0.79) (Table 2) (Figure 1A). On multivariate analysis, KPS <90 (RR=2.03, 95% CI 1.18–3.49; p-value=0.01), age ≥60 years (RR=1.82, 95% CI 1.03–3.21; p-value<0.03) and history of bone marrow involvement (RR=1.96, 95% CI 1.06–3.61; p-value<0.03) were associated with an increased risk of NRM. ERF was not associated with NRM (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.75–2.28; p-value=0.34).

Figure 1. Autologous transplantation outcomes for DLBCL, relative to the timing of rituximab failure.

(1A) Cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality, (1B) cumulative incidence of disease progression/relapse, (1C) progression-free survival and (1D) overall survival.

LRF = interrupted curves; ERF = solid curves.

Progression/relapse

Cumulative incidence of progression/relapse at 3-years was 47% (95% CI 41–52) for the ERF cohort and 39% (95% CI 33–46) for the LRF cohort (p=0.10) (Table 2) (Figure 1B). In multivariate models, ERF displayed a time-varying effect on the risk of lymphoma progression/relapse, with an increased risk during the first 6 months after autologous HCT (RR 2.86, 95% CI 1.89–4.33; p-value<0.001). Beyond 6 months post HCT the risk of progression/relapse was similar between groups (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.46–1.01; p-value=0.054). No other variables were associated with increased risk for progression/relapse (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis.

| N | Relative risk (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-relapse Mortality | |||

| Main Effect: ERF vs LRF | 297 vs 214 | 1.31 (0.75 – 2.28) | 0.342 |

| Other significant covariates: | |||

| Karnofsky performance status at transplant: | |||

| 90–100% vs. <90% | 328 vs. 147 | 2.03 (1.18 – 3.49) | 0.011 |

| 90–100% vs. Unknown | 328 vs. 36 | 0.31 (0.04 – 2.26) | 0.246 |

| Age at transplant: ≥60 vs <60 years | 258 vs 253 | 1.82 (1.03 – 3.21) | 0.039 |

| BM involvement at any time prior HCT: | |||

| No vs. Yes | 235 vs. 88 | 1.96 (1.06 – 3.61) | 0.031 |

| No vs. Missing | 235 vs. 188 | 0.51 (0.26 – 1.02) | 0.057 |

| Progression/relapse | |||

| Main Effect: ERF vs LRF | |||

| ≤6 months within transplant | 297 vs 214 | 2.86 (1.89 – 4.33) | <0.001 |

| >6 months beyond transplant | 157 vs 151 | 0.68 (0.46 – 1.01) | 0.054 |

| Treatment Failure (PFS) | |||

| Main Effect: ERF vs LRF | |||

| ≤9 months within transplant | 297 vs 214 | 2.08 (1.52 – 2.85) | <0.001 |

| >9 months beyond transplant | 157 vs 151 | 0.71 (0.47 – 1.07) | 0.101 |

| Other significant covariates: | |||

| Karnofsky performance status at transplant: | |||

| 90–100% vs. <90% | 328 vs. 147 | 1.33 (1.03 – 1.72) | 0.028 |

| 90–100% vs. Unknown | 328 vs. 36 | 1.07 (0.68 – 1.68) | 0.777 |

| Age at transplant: ≥60 vs <60 years | 258 vs 253 | 1.34 (1.06 – 1.71) | 0.017 |

| Mortality (OS) | |||

| Main Effect: ERF vs LRF | |||

| ≤9 months within transplant | 300 vs 216 | 3.75 (2.38 – 5.92) | <0.001 |

| >9 months beyond transplant | 191 vs 186 | 0.86 (0.59 – 1.26) | 0.438 |

| Other significant covariates: | |||

| Karnofsky performance status at transplant: | |||

| 90–100% vs. <90% | 149 | 1.50 (1.14 – 1.98) | 0.004 |

| 90–100% vs. Unknown | 36 | 1.13 (0.68 – 1.88) | 0.629 |

| Age at transplant: ≥60 vs <60 years | 262 vs 254 | 1.40 (1.07 – 1.81) | 0.013 |

Abbreviations: ERF=early rituximab failure; LRF=late rituximab failure;

Progression free survival

Three year PFS for ERF group was 44% (95% CI 38–50) compared to 52% (95% CI 45–59, p=0.08) in the LRF group (Table 2) (Figure 1C). On multivariate analysis, a time differential effect was noted on the risk of treatment failure. An increased risk of treatment failure (i.e. inferior PFS) for the ERF cohort was apparent only during the first 9 months after post autologous HCT (RR 2.08, 95% CI 1.52–2.85; p-value<0.001). Beyond 9 months after HCT, the risk of treatment failure was not significantly different between the ERF and LRF cohorts (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.47–1.07; p-value=0.10). Other variables associated with inferior PFS included KPS <90 (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.03–1.72; p-value=0.02) and age >60 years (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.06–1.71; p-value=0.01).

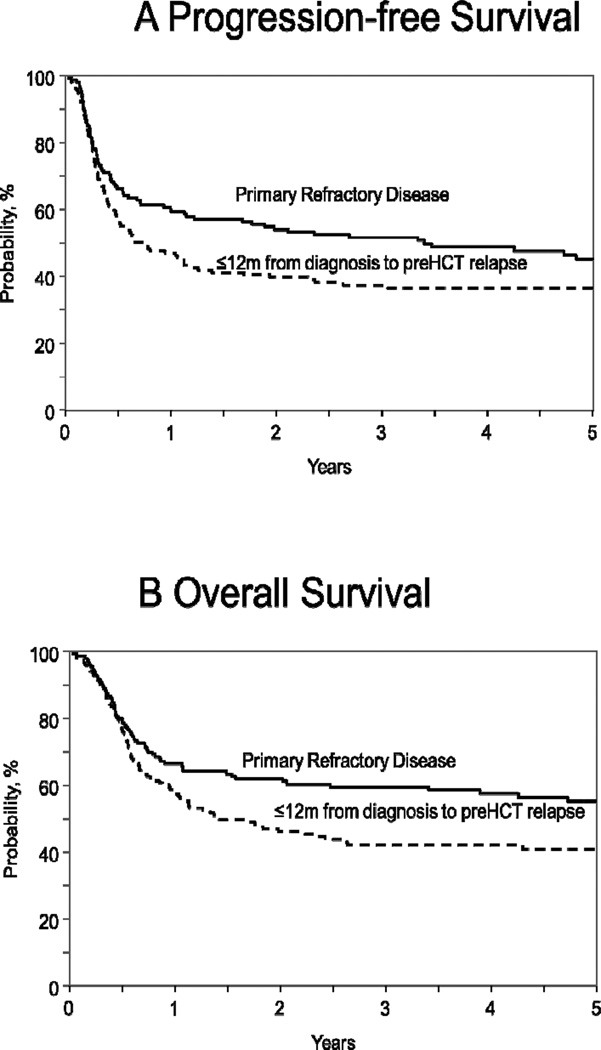

Subgroup analysis of ERF cohort only, showed that patients with primary refractory disease had superior PFS compared to ERF patients attaining a CR and then experiencing relapse within 12months of initial diagnosis (3-year PFS 51% vs. 37% respectively; p-value=0.01) (Table S1 in Supplemental Appendix, Figure 2A). This difference in PFS was however not confirmed on multivariate analysis (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.57 – 1.05; p-value=0.10, Table S2 in Supplemental Appendix).

Figure 2.

(2A) Progression-free survival and (2B) overall survival of early rituximab failure DLBCL patients with primary refractory disease (solid curve), compared to DLBCL relapsing within 12 months of initial diagnosis (interrupted curve).

Overall survival

Three year OS was significantly better in LRF group at 67% (95% CI 60–74) compared to 50% (95% CI 44–56, p<0.001) in the ERF group (Table 2) (Figure 1D). On multivariate analysis ERF cohort had an increased risk of mortality during the first 9 months after autologous HCT (RR 3.75, 95% CI 2.38–5.92; p-value<0.001). Beyond 9 months after HCT, the risk of mortality was not significantly different between the ERF and LRF cohorts (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.59–1.26; p-value=0.43). Other variables associated with inferior OS included KPS <90 (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.14–1.98; p-value=0.004) and age >60 years (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.07–1.81; p-value=0.01).

Among ERF cohort, patients with primary refractory disease had superior OS compared to ERF patients relapsing within 12 months of initial diagnosis (3 year OS 59% vs. 41% respectively; p-value=0.002) (Table S1 in Supplemental Appendix, Figure 2B). This difference in OS was not confirmed on multivariate analysis (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53 – 1.02; p-value=0.07, Table S2 in Supplemental Appendix).

Landmark analysis

Landmark analysis of ERF and LRF patients alive and progression-free at 9months post autologous HCT is described in Supplemental Appendix and figures 1S-2S.

Causes of death

Disease relapse and/or progression accounted for 72% (n=112) mortality in the ERF cohort and 52% (n=63) in the LRF cohort. Causes of death are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Causes of death.

| Early Rituximab Failure |

Late Rituximab Failure |

|

|---|---|---|

| Number of deaths | 155 | 82 |

| Primary disease | 112 (72) | 52 (63.4) |

| Infection | 7 (4.5) | 4 (5) |

| Pulmonary complications | 2 (1) | 1 (1.2) |

| Graft-versus-host disease (autologous) | 0 | 2 (2.4) |

| Organ failure | 12 (8) | 10 (12) |

| 2nd malignancy | 6 (4) | 2 (2.4) |

| Hemorrhage | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Other/missing | 15 (10) | 11 (13.4) |

DISCUSSION

The aims of the present study were to examine outcomes of DLBCL patients after autologous HCT, relative to the patterns of treatment failure following rituximab-containing upfront therapies. This large cohort of DLBCL patients receiving modern chemo-immunotherapies and transplanted across multiple centers in a contemporary era provides several important observations. First, relapsed DLBCL patients experiencing LRF have excellent outcomes following HDT and autologous HCT. Second, despite ERF, HDT can provide durable disease control in almost half of such chemosenstive patients, underscoring its continued utility in the current therapeutic armamentarium. Third, HDT is appropriate for patients with primary refractory disease who are responsive to subsequent salvage therapies. Fourth, our analysis identifies an extremely high (3–4 fold higher) risk of lymphoma relapse and death in the initial 6–9 months period following autologous HCT in the ERF cohort compared with the LRF cohort. Following this timeframe the risk of lymphoma progression/relapse and death were similar between the cohorts.

The estimated 5-year PFS of LRF cohort of 44% in our analysis is in line with historical rates observed in PARMA trial (5-year event-free survival 46%) [2] or in registry data from the rituximab-era [13], and serve to endorse HDT as the treatment-of-choice in such patients. The primary goal of this analysis was to evaluate if autologous HCT can salvage a subset of chemosensitive DLBCL patients with ERF. At the outset it is important to emphasize that CIBMTR registry does not capture information about relapsed DLBCL patients who never underwent HCT (e.g. due to lack of chemosensitive disease) and that our study excluded DLBCL patients who received HCT with chemorefractory disease. The dismal outcomes of such chemorefractory DLBCL patients with or without HDT are, however, well known [9,13,14] and not a subject of controversy. The primary message of our study is that in chemosensitive DLBCL patients, despite ERF, consolidation with autologous HCT is not an exercise in futility. This analysis provides critical data to validate current practice and addresses concerns present in transplant community [8,10]. In fact, the 3-year PFS of 44% of ERF cohort of our study is comparable to the 3-year PFS of 68 CORAL study patients who actually underwent autografting after ERF [11].

Early therapy failure, across hematological malignancies, is a well-known surrogate marker of biologically more aggressive disease and DLBCL is no exception. In fact, the association of early relapse in DLBCL with inferior outcomes is not uniquely limited to patients treated in rituximab-era and has also been seen in rituximab-naïve patients [15,16]. Even in our current analysis, while outcomes of ERF cohort are encouraging, they clearly underperform when compared with the LRF cohort. However, our data support that HCT should not be abandoned in this group but can be used instead to form the basis of prospective strategies to improve outcomes of these adverse-risk patients, including; (a) new modalities providing high salvage therapy response rates in ERF DLBCL (to increase patient-pool eligible for HDT) and (b) peri-autologous HCT therapy modifications to prevent disease relapse. The low response rates (~40–45%) of ERF DLBCL to salvage chemotherapies [11,17] often precludes HDT consolidation in these patients. Evaluation of alternate salvage strategies including novel antibody-based regimens [18], antibody-drug conjugate-based regimens [19], or cytarabine-containing options in germinal center B–like cases [20] warrant investigation to improve response rates in these adverse-risk patients.

For those ERF patients responsive to salvage therapies and able to undergo HDT, majority of the relapses appear to happen early post HCT (progression/relapse rate of 40% at 1-year compared to 47% at 3-years in our study), underscoring the need to provide better disease control in the immediate post-transplant period. The results of the recent BMT-CTN 0401 study [21] suggest that mere intensification of HCT conditioning with radioimmunotherapy may not be the best strategy to achieve this goal. The observation from our multivariate analysis that differences in outcomes of ERF and LRF are more pronounced during the first 6–9 months post HCT is hypothesis generating and argues for developing strategies addressing the heightened treatment-failure risk in the early post HCT period in ERF DLBCL patients. While results with post-HCT rituximab maintenance in relapsed DLBCL in general have not been impressive [22], investigation of novel consolidation and/or maintenance strategies (e.g. programmed death-1 blockade [23], ibrutinib [24], PI3K inhibitors [25]) for ERF DLBCL may improve HCT outcomes. Allogeneic HCT is another modality that can potentially improve outcomes of ERF patients. In a recent prospective study, Glass et al [26] reported 3-year OS of approximately 35% OS for aggressive B-cell lymphoma patients with either primary refractory disease or relapse within 12months after first-line treatment (as opposed to <12months of initial diagnosis in CORAL study and our analysis). In this study the authors did not report the outcomes of patients with chemosensitive and chemotherapy-unresponsive disease at the time of HCT, separately. With this limitation in mind, the 3-year OS of 50% for ERF patients with chemosensitive disease in our current report compares favourably with the 3-year OS of 35% (estimated from the figures in the supplemental appendix of manuscript) in the study by Glass et al [26]. However these data by Glass et al are very important, as they confirm the prior observations of CIBMTR registry studies, that allogeneic HCT can provide durable disease control (3-year OS of ~25–35%) in a subset of DLBCL patients with either chemosensitive [27] or chemotherapy-unresponsive disease [28] at transplantation.

The subgroup analysis of ERF cohort in our study showed that patients with primary refractory disease had superior OS and PFS compared to ERF patients attaining a CR and then experiencing relapse within 12months of initial diagnosis. However, it is important to highlight that after adjusting for confounding variables in multivariate models, this observation was not confirmed. Baseline characteristics of these two sub-groups are shown in Supplemental Table S3. Patients with primary refractory disease, were significantly younger than those relapsing within 12months of initial diagnosis (median age 56 vs. 60 years respectively; p=0.001). Since patient age was an independent predictor of OS and PFS of these two sub-groups on multivariate analysis (please see Supplemental Table S2) it is possible that after adjusting for age (and other covariates) in the multivariate model, the observed differences in the OS and PFS seen on univariate analysis between the ERF patients with primary refractory disease vs. those with early relapse, was not confirmed.

A number of biologic features impact DLBCL outcome, including cell-of-origin (COO) [29] or c-myc expression [30]; however these data are not available in the CIBMTR registry. It however, merits mention here that while COO clearly impacts the success of salvage chemo-immunotherapies [20,31], its impact on the prognosis of relapsed, chemosensitive DLBCL post autologous HCT has not been demonstrated, thus far [32–34]. Another possible limitation of our data is lack of functional imaging (PET scanning) status pre HCT [35]. It is plausible that even among chemosensitive ERF DLBCL, patients achieving a PET negative state may enjoy superior outcomes post HCT.

In conclusion, our analysis shows that autologous HCT provides durable disease control in a clinically significant subset of chemosensitive DLBCL with ERF. These results are practice validating and strongly support the continued use of HDT as the treatment of choice in relapsed, chemoresponsive DLBCL patients, regardless of the timing of relapse. Our data identify first 6–9 months post HCT as a period of heightened vulnerability to relapse and therapy failure, where investigation of novel consolidation and/or maintenance strategies is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank additional co-authors, Onder Alpdogan, Amanda Cashen, Christopher Dandoy, Robert Finke, Robert Peter Gale, John Gibson, Jack W. Hsu, Nalini Janakiraman, Mary J. Laughlin, Michael Lill, Mitchell S. Cairo, Reinhold Munker, Phil A. Rowlings, Harry C. Schouten, Thomas C. Shea, Patrick J. Stiff and Edmund K. Waller, for their helpful comments and insights as members of the study writing committee.

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-12-1-0142 and N00014-13-1-0039 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from *Actinium Pharmaceuticals; Allos Therapeutics, Inc.; *Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Ariad; Be the Match Foundation; *Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; *Celgene Corporation; Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc.; *Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.;*Gentium SpA; Genzyme Corporation; GlaxoSmithKline; Health Research, Inc. Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Jeff Gordon Children’s Foundation; Kiadis Pharma; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Medac GmbH; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck & Co, Inc.; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Co.; *Milliman USA, Inc.; *Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Perkin Elmer, Inc.; *Remedy Informatics; *Sanofi US; Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Soligenix, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; StemCyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics Co.; Stemsoft Software, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; *Tarix Pharmaceuticals; *TerumoBCT; *Teva Neuroscience, Inc.; *THERAKOS, Inc.; University of Minnesota; University of Utah; and *Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

*Corporate Members

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Philip T, Armitage JO, Spitzer G, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation after failure of conventional chemotherapy in adults with intermediate-grade or high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N.Engl.J.Med. 1987;316:1493–1498. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706113162401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N.Engl.J.Med. 1995;333:1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verdonck LF, van Putten WL, Hagenbeek A, et al. Comparison of CHOP chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow transplantation for slowly responding patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N.Engl.J.Med. 1995;332:1045–1051. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504203321601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N.Engl.J.Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040–2045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trumper L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Osterborg A, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:379–391. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gisselbrecht C. Is there any role for transplantation in the rituximab era for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma? Hematology Am.Soc.Hematol.Educ.Program. 2012;2012:410–416. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vose JM, Zhang MJ, Rowlings PA, et al. Autologous transplantation for diffuse aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in patients never achieving remission: a report from the Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry. J.Clin.Oncol. 2001;19:406–413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gascoyne RD, Moskowitz C, Shea TC. Controversies in BMT for lymphoma. Biol.Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:S26–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, et al. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J.Clin.Oncol. 2010;28:4184–4190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet. 2002;359:1309–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenske TS, Hari PN, Carreras J, et al. Impact of pre-transplant rituximab on survival after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Biol.Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1455–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus HM, Zhang MJ, Carreras J, et al. A comparison of HLA-identical sibling allogeneic versus autologous transplantation for diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a report from the CIBMTR. Biol.Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mounier N, Canals C, Gisselbrecht C, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in first relapse for diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: an analysis based on data from the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Registry. Biol.Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:788–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guglielmi C, Gomez F, Philip T, et al. Time to relapse has prognostic value in patients with aggressive lymphoma enrolled onto the Parma trial. J.Clin.Oncol. 1998;16:3264–3269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.10.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin A, Conde E, Arnan M, et al. R-ESHAP as salvage therapy for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the influence of prior exposure to rituximab on outcome. A GEL/TAMO study. Haematologica. 2008;93:1829–1836. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matasar MJ, Czuczman MS, Rodriguez MA, et al. Ofatumumab in combination with ICE or DHAP chemotherapy in relapsed or refractory intermediate grade B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2013;122:499–506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-472027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fayad L, Offner F, Smith MR, et al. Safety and clinical activity of a combination therapy comprising two antibody-based targeting agents for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: results of a phase I/II study evaluating the immunoconjugate inotuzumab ozogamicin with rituximab. J.Clin.Oncol. 2013;31:573–583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.7211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thieblemont C, Briere J, Mounier N, et al. The germinal center/activated B-cell subclassification has a prognostic impact for response to salvage therapy in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a bio-CORAL study. J.Clin.Oncol. 2011;29:4079–4087. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vose JM, Carter S, Burns LJ, et al. Phase III randomized study of rituximab/carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM) compared with iodine-131 tositumomab/BEAM with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the BMT CTN 0401 trial. J.Clin.Oncol. 2013;31:1662–1668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gisselbrecht C, Schmitz N, Mounier N, et al. Rituximab maintenance therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with relapsed CD20(+) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final analysis of the collaborative trial in relapsed aggressive lymphoma. J.Clin.Oncol. 2012;30:4462–4469. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.9416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armand P, Nagler A, Weller EA, et al. Disabling immune tolerance by programmed death-1 blockade with pidilizumab after autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results of an international phase II trial. J.Clin.Oncol. 2013;31:4199–4206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Shaffer AL, 3rd, Emre NC, et al. Exploiting synthetic lethality for the therapy of ABC diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer.Cell. 2012;21:723–737. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathews Griner LA, Guha R, Shinn P, et al. High-throughput combinatorial screening identifies drugs that cooperate with ibrutinib to kill activated B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2014;111:2349–2354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311846111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glass B, Hasenkamp J, Wulf G, et al. Rituximab after lymphoma-directed conditioning and allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DSHNHL R3): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:757–766. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bacher U, Klyuchnikov E, Le-Rademacher J, et al. Conditioning regimens for allotransplants for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: myeloablative or reduced intensity? Blood. 2012;120:4256–4262. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-436725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamadani M, Saber W, Ahn KW, et al. Impact of pretransplantation conditioning regimens on outcomes of allogeneic transplantation for chemotherapy-unresponsive diffuse large B cell lymphoma and grade III follicular lymphoma. Biol.Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:746–753. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savage KJ, Johnson NA, Ben-Neriah S, et al. MYC gene rearrangements are associated with a poor prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. Blood. 2009;114:3533–3537. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuccuini W, Briere J, Mounier N, et al. MYC+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is not salvaged by classical R-ICE or R-DHAP followed by BEAM plus autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119:4619–4624. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-406033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moskowitz CH, Zelenetz AD, Kewalramani T, et al. Cell of origin, germinal center versus nongerminal center, determined by immunohistochemistry on tissue microarray, does not correlate with outcome in patients with relapsed and refractory DLBCL. Blood. 2005;106:3383–3385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa LJ, Feldman AL, Micallef IN, et al. Germinal center B (GCB) and non-GCB cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphomas have similar outcomes following autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br.J.Haematol. 2008;142:404–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu K, Weisenburger DD, Fu K, et al. Cell of origin fails to predict survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Hematol.Oncol. 2012;30:143–149. doi: 10.1002/hon.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armand P, Welch S, Kim HT, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma and transformed indolent lymphoma undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation in the positron emission tomography era. Br.J.Haematol. 2013;160:608–617. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.