Abstract

We report the screening and characterization of EPS produced by LAB identified as Leuconostoc kimchii isolated from pulque, a traditional Mexican fermented, non-distilled alcoholic beverage produced by the fermentation of the sap extracted from several (Agave) maguey species. EPS-producing LAB constitutes an abundant bacterial group relative to total LAB present in sap and during fermentation, however, only two EPS-producing colony phenotypes (EPSA and EPSB, respectively) were detected and isolated concluding that despite the high number of polymer-producing LAB their phenotypic diversity is low. Scanning electron microcopy analysis during EPS-producing conditions revealed that both types of EPS form a uniform porous structure surrounding the bacterial cells. The structural characterization of the soluble and cell-associated EPS fractions of each polymer by enzymatic and acid hydrolysis, as by 1D- and 2D-NMR, showed that polymers produced by the soluble and cell-associated fractions of EPSA strain are dextrans consisting of a linear backbone of linked α-(1→6) Glcp in the main chain with α-(1→2) and α-(1→3)-linked branches. The polymer produced by the soluble fraction of EPSB strain was identified as a class 1 dextran with a linear backbone containing consecutive α-(1→6)-linked D-glucopyranosyl units with few α-(1→3)-linked branches, whereas the cell-associated EPS is a polymer mixture consisting of a levan composed of linear chains of (2→6)-linked β-D-fructofuranosyl residues with β-(2→6) connections, and a class 1 dextran. According to our knowledge this is the first report of dextrans and a levan including their structural characterization produced by L. kimchii isolated from a traditional fermented source.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/2193-1801-3-583) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pulque, Lactic acid bacteria, Leuconostoc kimchii, Exopolysaccharides, Dextran, Levan

Background

The analysis of the microbial diversity in traditional fermented beverages, cereal doughs and vegetables has revealed the presence of a remarkable diversity of LAB involved in the development of the characteristic sensorial properties of fermented foods (Giraffa 2004). A wide diversity of EPS and genes encoding biosynthetic enzymes from naturally occurring LAB in traditional fermented foods and beverages have been extensively studied for their role in the physicochemical and sensorial characteristics of final fermented products (viscosifying, stabilizing or water-binding agents). This has led to the discovery of a remarkable structural diversity of EPS produced by LAB, particularly of the genus Leuconostoc and Weissella (Chellapandian et al. 1998; Uzochukwu et al. 2001; Olivares-Illana et al. 2002; Uzochukwu et al. 2002; van Hijum et al. 2006; Eom et al. 2007; Van der Meulen et al. 2007; Bauer et al. 2009; Bounaix et al. 2009; Bounaix et al. 2010; Amari et al. 2012; Vasileva et al. 2012). EPS have received additional attention as valuable products because of their potential economic applications that include natural, safe-food additives or natural functional food ingredients for their properties as soluble fiber and prebiotics, and the possibility that they can replace or reduce the use of hydrocolloids (Giraffa 2004; Tieking et al. 2005; Vu et al. 2009; Leemhuis et al. 2013).

Pulque is a traditional Mexican, non-distilled alcoholic fermented beverage currently produced and consumed mainly in the Central Mexico Plateau. It is obtained from the fermentation of a fresh sap, known as aguamiel, which is extracted from several maguey (Agave) species, such as Agave atrovensis and A. americana. The production of this traditional beverage requires for the freshly collected aguamiel to be deposited in large open containers where previously fermented pulque acts as seed for a new batch. Fermentation time varies from a few hours, overnight, or even for several days. Fermented pulque is gradually retired from the container but always leaving a residual volume of the fermented beverage to start a new fermentation. The viscosity resultant from EPS synthesis and the alcohol content of the beverage are the main parameters used to determine the extent of fermentation as they define its distinctive sensorial properties (Escalante et al. 2008; Escalante et al. 2012).

The LAB L. mesenteroides has been traditionally considered one of the most important microorganisms during pulque fermentation as a result of its ability to synthesize EPS, primarily dextrans produced by a glucosyltransferase from sucrose present in aguamiel and pulque (Sanchez-Marroquin and Hope 1953; Chellapandian et al. 1998; Escalante et al. 2012). Although EPS production by Leuconostoc species isolated from pulque was first reported in 1953, no detailed information was available concerning the properties or structure of these polymers (Sanchez-Marroquin and Hope 1953). Nevertheless, the structure of an EPS produced by L. mesenteroides strain IBT-PQ isolated from pulque, revealed the presence of a soluble linear dextran with glucose molecules linked primarily by α-(1→6) bonds with branching from α-(1→3) bonds, in a 4:1 ratio, and was produced by a cell-associated dextransucrase displaying a similar biochemical behavior to that reported for this enzyme obtained from the industrial strain L. mesenteroides NRRL B512F (Chellapandian et al. 1998).

We have previously reported a great LAB diversity in aguamiel and pulque samples from different geographical origins, that is composed mainly of Lactobacillus and Leuconostoc species (Escalante et al. 2004). Among them L. citreum and L. kimchii were reported for the first time to be the most abundant LAB present in aguamiel and during the early stages of pulque fermentation (Escalante et al. 2008). This remarkable abundance of L. citreum and L. kimchii in aguamiel and pulque, suggests the presence of a possible diversity of EPS produced by these LAB during fermentation contributing to the final sensorial properties of the beverage. The aim of the present work was to screen and characterize the EPS diversity associated to the LAB L. kimchii isolated during traditional pulque fermentation. Screening of LAB was based in their ability to produce EPS from sucrose; this method resulted in the identification of two unique EPS-producing colony types. Structural characterization of these polymers including SEM during EPS production conditions, enzymatic and acid hydrolysis, as 1D- and 2D- 1H- and 13C-NMR allowed the detection of dextran and levan polymers produced by this LAB.

Results and discussion

Isolation and identification of EPS-producing LAB

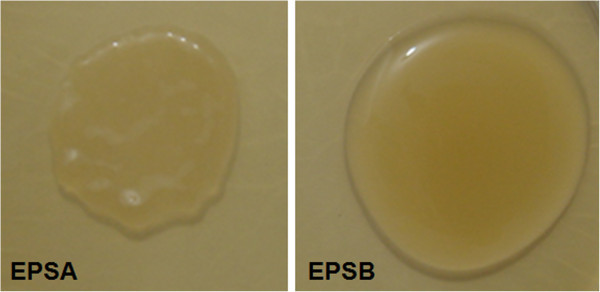

The total EPS-producing LAB CFU/mL detected by growth on APTS plates was 50% in previously fermented pulque, 47% in aguamiel, 50.8% at T0, 70.4% at T3, and 50% at the end of the fermentation (T6), compared to the total LAB CFU/mL grown on APT plates. These results indicated a great abundance of EPS-producing LAB in pulque, aguamiel, and during the fermentation process. The visual analysis of purified EPS-producing colonies for unique morphology grown on APTS, allowed the identification of only two EPS colony phenotypes, leading to the conclusion that despite the high number of polymer-producing LAB, phenotypic diversity is low. The fastest growing colony of each EPS type was selected and designated as EPSA (compact colony morphology) and EPSB (creamy colony morphology) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phenotypic traits of EPS produced by pulque isolated Leuconostoc kimchii strains. Compact left colony or EPSA and creamy right colony or EPSB grown on APT plates supplemented with 20% sucrose.

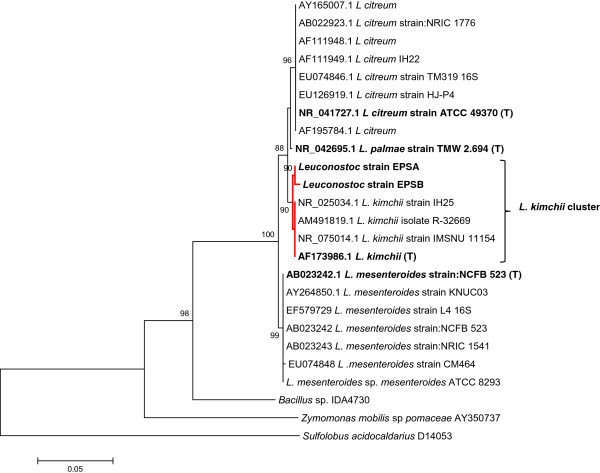

Analysis of the 16S rDNA sequence of strains EPSA and EPSB in the non-redundant database of the NCBI archive database showed that the closest matching sequences found, corresponded to L. kimchii strain IMSNU 11154 (an isolated LAB from Korean kimchi), L. palmae strain TMW 2.694, and diverse L. citreum 16S rDNA sequences in both cases. To precise identity of EPS isolates, a phylogenetic analysis was performed using several Leuconostoc 16S rDNA reference sequences retrieved from the GenBank database, such as L. citreum, L. kimchii, L. mesenteroides, and L. palmae including type strains. The resulting neighbor-joining tree clearly demonstrated that the 16S rDNA sequences of the EPSA and EPSB isolates were placed in a cluster in which only L. kimchii sequences were included. However, the 16S rDNA sequence from L. palmae strain: TMW 2.694, isolated from palm wine (Ehrmann et al. 2009), was placed in the closest single terminal node separated from the well-defined clusters of the 16S rDNA sequences from L. kimchii, L. citreum, and L. mesenteroides (Figure 2). The 16S rDNA sequences corresponding to the EPSA and EPSB L. kimchii strains isolated from pulque were deposited into the GenBank database and accession numbers KC424437 and KC424438 were assigned to strains EPSA and EPSB, respectively. L. kimchii strain IMSNU 11154 was originally isolated from traditional Korean kimchi, a traditional fermented vegetable food (Kim et al. 2000). Complete genome sequencing of the EPS-producing L. kimchii strain IMSNU 11154 was reported and demonstrated the presence of genes corresponding to GTFs capable to produce dextran from sucrose (Oh et al. 2010).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of 16S rDNA sequences of EPSA and EPSB isolates and 16S rDNA reference sequences. Some 16S rDNA sequences of L. citreum, L. palmae, L. kimchii, and L. mesenteroides strains deposited in the GenBank database including type strains of each genus (bold) are included as references. Accession numbers of reference sequences are indicated. The 16S rDNA sequences of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and Zymomonas mobilis are included as outgroups. The percentage of 1000 bootstrap samplings supporting each topological element in the neighbor-joining analysis is indicated. No values are given for groups with bootstrap values less than 80%. L. kimchii cluster including EPSA and EPSB sequences is highlighted.

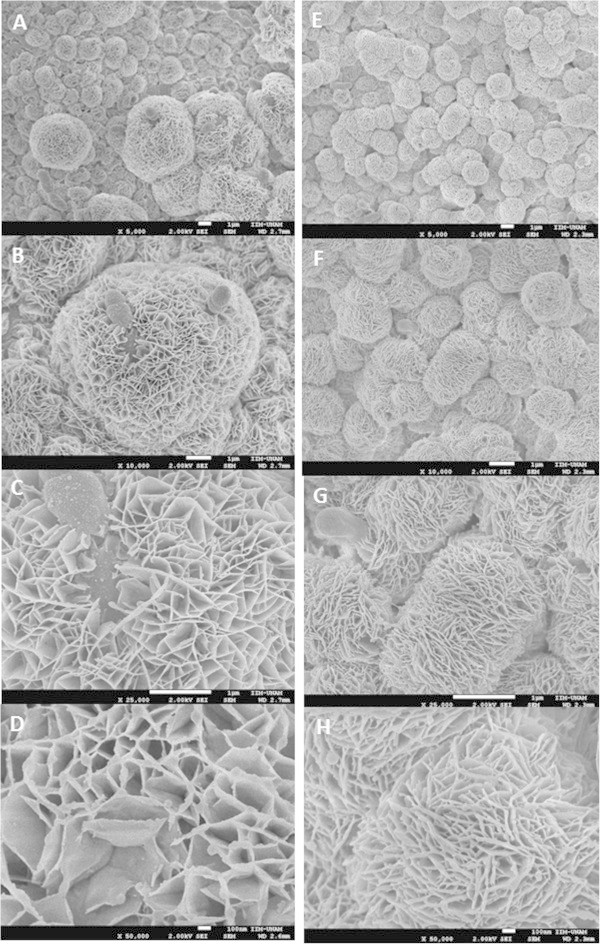

Scanning electronic microscopy of EPS-producing LAB

The SEM observation of EPS-producing colonies of EPSA and EPSB growing on APTS plates showed the presence of porous -“cocoon-like” structures associated with the cells (cocci) in both strains. These structures surround the bacterial cells and have different sizes depending on the colony, with larger structures observed for EPSA (Figure 3). Although for both strains a surrounding hollow porous structure is observed, the polymer matrix produced by the EPSB strain appears more compact when compared to the EPSA polymer matrix. No other dextran produced by LAB has been previously analyzed by SEM, although a rather similar porous structure was previously reported for the dried cell-free insoluble dextran produced by L. mesenteroides NRRL B-1149 (Shukla et al. 2011).

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis of EPS-producing Leuconostoc kimchii. Images A-D, correspond to different fields of EPSA producing strain at 5 000X, 10 000X, 25 000X, and 50 000X, respectively. Images E-H, correspond to different fields of EPSB producing strain at 5 000X, 10 000X, 25 000X, and 50 000X, respectively.

Evidence of glycosyltransferase activity

Total GTF activity was determined either in the cell culture supernatant or associated to the cell fraction of cultures for L. kimchii EPSA and EPSB isolates on APTS broth. For the EPSA isolate, a maximum of 3.2 U/L was observed in the supernatant after 6 h of fermentation, when the pH decreased to 4.4. GTF activity was also found to be associated with the cultures´s cell fraction showing a maximum activity of 1.8 U/L after 4 h. When the culture supernatant reached pH 5.5; the insoluble activity was approximately 36% of the total GTF activity produced by the cells. The total GTF activity was found higher in a similar analysis performed with the EPSB strain. In this case the soluble GTF activity reached 11.21 U/L after 6 h of fermentation when the culture supernatant pH was 4.6, while the cell-associated GTF activity reached a maximum of 5.57 U/L after 6 h, representing 33% of the total GTF activity. These culture conditions were selected to produce soluble and cell-associated polymers for structural characterization. It was also found that the isolated strains EPSA and EPSB showed higher residual total GTF activity in the temperature range of 30°C - 40°C, both in soluble and cell-associated fractions. Regarding the pH, both EPSA and EPSB-soluble fractions showed higher residual total GTF activity at pH 5.4, while both EPSA and EPSB cell-associated fractions showed higher residual total GTF activity at pH 6.0.

The GTF activity level associated only to the soluble or cell-associated fractions, or in both fractions ranging 0.8 to 2 U/mL was previously detected in several Leuconostoc and Weissella isolated strains from fermented sources (Bounaix et al. 2009; Vasileva et al. 2012). Our results showed that the GTF activity detected in the soluble fractions of L. kimchii EPSA and EPSB strains, was higher than the activity found in the cell-associated fractions was but low when compared with previous reports (Bounaix et al. 2010; Bounaix et al. 2009; Vasileva et al. 2012). EPS production by LAB from sucrose was reported that depends on diverse factors such as the cultivation conditions (aerobic, anaerobic and temperature) and media composition (liquid or solid media, rich media such as MRS or APT or mineral media supplemented with phosphate sources, tryptone or yeast extract) (Maina et al. 2008; Minervini et al. 2010). While further investigation is required to determine the fine enzymatic properties of GTF responsibles for soluble and cell-associated EPS production in both EPSA and EPSB L. kimchii isolates, to our knowledge, these results provide evidence that GTF is involved in EPS production by this LAB isolated from a traditional alcoholic fermented beverage for the first time. Previous studies involving both glucosyltransferase and fructosyltransferase characterization have been performed particularly in diverse EPS-producing Leuconostoc, Weissella, and Lactobacillus species isolated from fermented beverages, cereal doughs, and vegetables (Table 1).

Table 1.

EPS produced from sucrose by LAB isolated from traditional fermented products

| EPS type | EPS structure (producing LAB) | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dextran | Linear backbone linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with branching in α-(1→3) D-Glcp produced by a cell-associated GTF (L. mesenteroides IBT-PQ strain) | Pulque (fermented alcoholic beverage) | (Chellapandian et al. 1998) |

| Dextrana | Linear backbone linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with branching in α-(1→2) (L. mesenteroides). | Palm wine | (Uzochukwu et al. 2001) |

| Linear backbone linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with branching in α-(1→3) with minor α-(1→4) linked branches (L. dextranicum). | |||

| Linear backbone linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with branching in α-(1→3) (Lactobacillus spp. AW strain) | |||

| Fructan | Inuline-like structure with β-(2→1) glycosidic linkages produced by a cell-associated fructosyltransferase (L. citreum) | Pozol (maize fermented dough) | (Olivares-Illana et al. 2002) |

| Dextrana | Dextran type I containing α-(1→2) D-Glcp and α-(1→3) linked branches (L. citreum VTT E-93497 strain). | Malting process | (Maina et al. 2008) |

| Dextran type I containing few α-(1→3) linked branches (W. confusa VTT E-90392 strain) | Soured carrot mash | ||

| Dextran | Dextran type I linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with few α-(1→3) linked branches produced by soluble GTF (Several L. mesenteroides and Weissella spp isolates) | Traditional French wheat sourdough | (Bounaix et al. 2009) |

| Dextran type I linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with α-(1→2) linked branches produced by soluble GTF (several L. mesenteroides and L. citreum isolates) | |||

| Dextran type I linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with high α-(1→3) linked branches produced by soluble GTF (Several L. citreum isolates) | |||

| Dextran/levan mixture | Dextran type I linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with high α-(1→3) linked branches produced by soluble and cell-associated GTF mixed with a levan (several L. mesenteroides isolates) | Traditional French wheat sourdough | (Bounaix et al. 2009) |

| Dextran | Dextran type I linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with few α-(1→2) linked branches (W. confusa LBAE C39-2) | Traditional French wheat sourdough | (Amari et al. 2012) |

| Dextrana | Linear backbone linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp (Lactobacillus curvatus 69B2 strain and Leuconostoc lactis 95A strain) | Wheat sourdough | (Palomba et al. 2012) |

| Dextran | Linear backbone linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with α-(1→3) linked branches produced by soluble and cell-associated GTF (L. mesenteroides) | Bulgarian fermented vegetables | (Vasileva et al. 2012) |

| Dextran/levan mixture | Dextran linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp (56%) and a levan (44%) (L. mesenteroides URE and Lm 17 strains) | Bulgarian fermented vegetables | (Vasileva et al. 2012) |

| Dextrana | Linear backbone linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp (L. mesenteroides and W. confusa) | Kimchi (traditional fermented vegetable food) | (Park et al. 2013) |

| Dextran | Linear backbone linked mainly in α-(1→6) D-Glcp with α-(1→2) and α-(1→3) linked branches produced by a soluble and cell-associated GTF (L. kimchii EPSA strain) | Pulque | This work |

| Dextran type I containing few α-(1→3) linked branches produced by a soluble GTF (L. kimchii EPSB strain) | |||

| Levan/dextran mixture | Polymer mixture composed by linear chains of (2→6)-linked β-D-fructofuranosyl residues with connections β-(2→6) (79%), and a dextran Type I (21%) produced by the cell-associated GTF fraction (L. kimchii EPSB strain) | Pulque | This work |

aNo information about GTF producing enzymes is provided.

EPSA and EPSB characterization

Hydrolysis of soluble and cell-associated EPS fractions

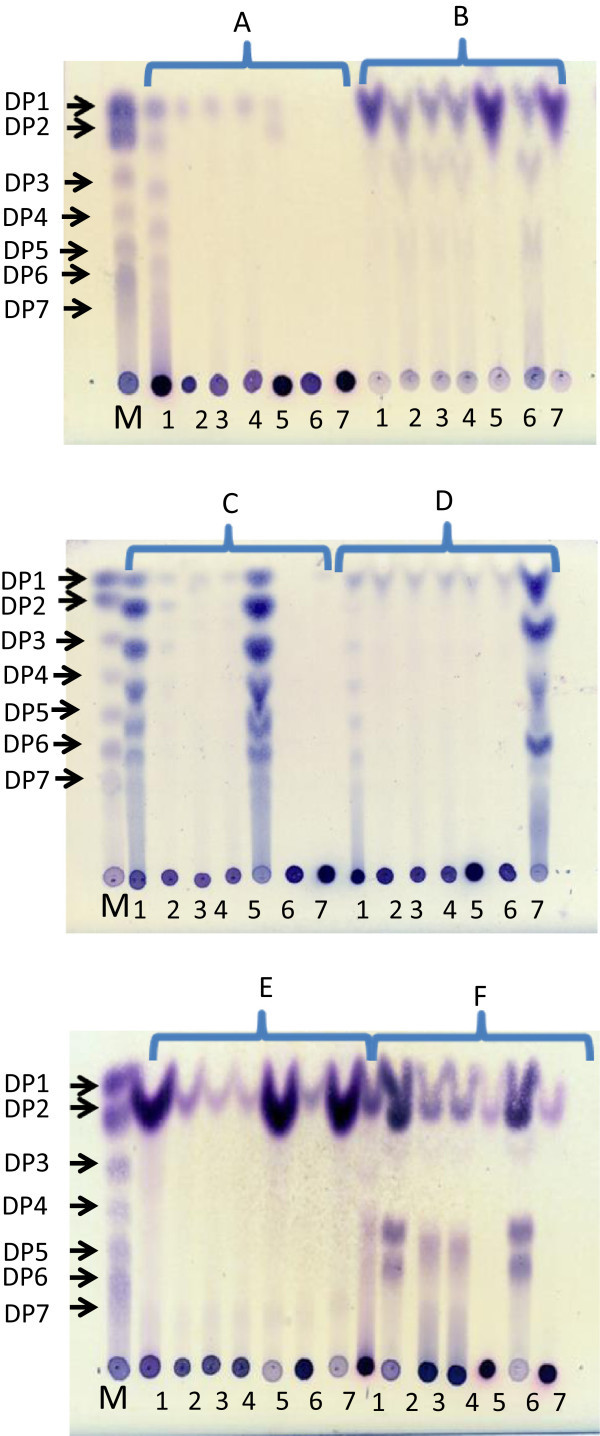

Enzymatic hydrolysis assays of the cell-associated and soluble EPSA and EPSB polymer samples showed that polymers produced by the EPSA-soluble and cell-associated GTF were hydrolyzed only by dextranase but not by endolevanase, inulinase or Fructozyme®. These results indicated the presence of a dextran with α-(1→6) D-Glcp linkages (Figure 4), similar to dextrans that result from GTF synthesis. Similarly, the polymer produced by the EPSB-soluble fraction was also only hydrolyzed by dextranase, demonstrating the presence of α-(1→6) D-Glcp linkages as in dextran. Nevertheless, the polymer produced by the EPSB cell-associated fraction was degraded by dextranase, endolevanase and Fructozyme® but not by inulinase, indicating the presence of a polymer mixture composed of a linear dextran and a levan. Furthermore, acid treatment of EPS with H2SO4 yielded hydrolysis giving the expected monomers.

Figure 4.

Enzymatic and acid hydrolysis of EPSA and EPSB polymers. 1. EPSB cell-associated fraction; 2. EPSB-soluble fraction; 3. EPSA cell-associated fraction; 4. EPSA-soluble fraction; 5. Levan from B. subtilis; 6. Dextran from L. mesenteroides B-512; 7. Inulin from L. citreum. M. Glucose + fructose + maltodextrins standards; A. Non-treated samples; B. Acid hydrolysis treatment; C. Endolevanase treatment; D. Endoinulinase treatment; E. Fructozyme® treatment; F. Dextranase treatment. DP = Degree of polymerization.

1H- and13C-NMR analysis of soluble and cell-associated EPSA and EPSB fractions

As enzymatic hydrolysis demonstrated that soluble and cell-associated fractions of EPSA are the same polymer, only the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra of the EPSA-soluble fraction was determined, whereas for the soluble and cell-associated polymers of L. kimchii EPSB strain both spectra were obtained. Resultant NMR spectra were compared with those previously reported for diverse polymers produced by several L. mesenteroides, L. citreum, and Weissella sp. strains (Colson et al. 1974; Seymour et al. 1976; Seymour et al. 1979; Shimamura et al. 1987; Uzochukwu et al. 2001; Uzochukwu et al. 2002; Maina et al. 2008; Bounaix et al. 2009; Vasileva et al. 2012).

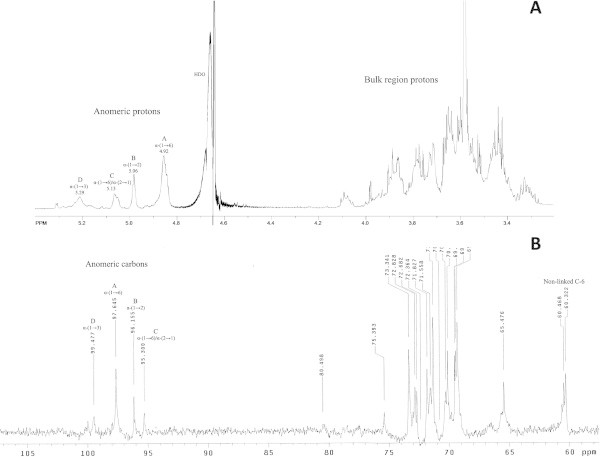

Comparison of the NMR results with previously reported spectra for dextrans produced during palm wine fermentation (Uzochukwu et al. 2002) revealed that EPSA is a dextran with a linear backbone of linked α-(1→6) D-glucopyranosyl units in the main chain confirming enzymatic hydrolysis assay results, but with α-(1→2) and α-(1→3) D-Glcp linked branches. The 1H-NMR spectra showed four anomeric proton signals at δ 4.92, 5.06, 5.13, and 5.29 labeled A-D, respectively (Figure 5A) corresponding to the α-(1→6) D-Glcp, the α-(1→2) branching D-Glcp, the 2,6 di-O-substituted α-D-Glcp, and the α-(1→3) D-Glcp units, respectively. The relative intensities of the A-D peaks were 15.30%, 12.41%, 16.86%, and 55.43%, respectively, resulting proportional to the degree of branching. HSQC of EPSA (Additional file 1) showed their attachment to the anomeric carbons at δ 97.64, 96.15, 95.30, and 99.47 corresponding respectively to 1H anomeric signals at δ 4.92, 5.06, 5.13, and 5.29 (Figure 5B). These signals characteristically served as the starting point for the analysis of the 1H–1H COSY and TOCSY experiments for connectivities within the spin system.

Figure 5.

NMR spectra of EPSA soluble fraction. (A) 1H-NMR spectrum. (B) 13C-NMR spectrum. Anomeric protons are labeled A–D according to the increasing chemical shifts.

The C-H correlation spectrum (HSQC) indicated that 13C resonances at δ 65.48 split into two peaks (Additional file 1). The correlation peak showed the 1H resonance at δ 3.70 and δ 3.93. The other 13C peaks at δ 60.32, 60.47, and 60.65 showed their protons as a multiplet at δ 3.78 and δ 3.66 which corresponded to non-linked C-6. The previous characterization of dextrans from fermented palm wine showed that its backbone contains a bound C-6 with a chemical shift at δ 66.6 (Uzochukwu et al. 2002), whereas for EPSA polymer it was found at δ 65.48, resulting farthest downfield than a free C-6 at δ 61.4 (δ 60.32, 60.47, and 60.65 for EPSA polymer). Finally, the long-range correlation between H-3 (δ 3.81) and the anomeric carbon at δ 99.47 of EPSA polymer in the HMBC spectrum allowed to confirm the presence of α-(1→3)-linked branches (Additional file 1).

Furthermore, in the δ 68–74 region of the 13C-NMR spectrum of EPSA, were found characteristic branching signals for linked C-2 and C-3 at branching points, which split in three peaks found in δ 71.83, 71.56, and 71.31; and in the region at δ 69.53, 69.46, and 69.31, respectively (Figure 5b). These data were consistent with previous results of spectra for the series of dextrans B1254, B1355S, and B1099L (Seymour et al. 1976). The split in the free C-6 around δ 60-61 represents C-6 in different chemical environments with two possible sources of branch-terminating residues: α-(1→2) and α-(1→3) branching. Free C-6 signals in EPSA polymer were detected at δ 60.32, 60.47, and 60.65, respectively and were associated with branching at C-2 and C-3, respectively, indicating that in EPSA polymer the linkage is present both as branch point and intra chain linkages as reported previously for palm wine dextran (Uzochukwu et al. 2002).

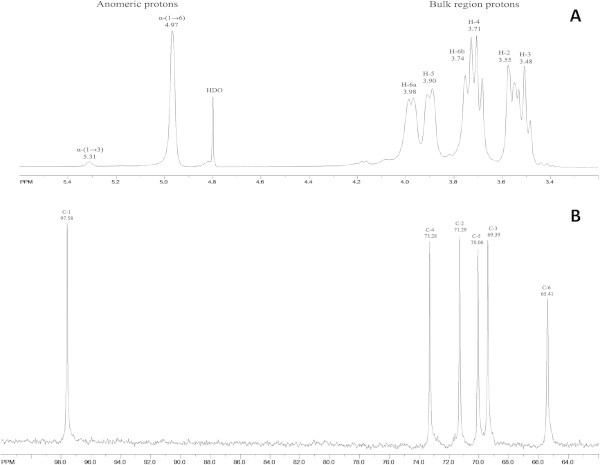

NMR spectra results for EPSB polymers corroborated that its soluble fraction is a dextran with a linear backbone containing consecutive α-(1→6)-linked D-glucopyranosyl units with few α-(1→3)-linked branches, structure characteristic of class 1 dextrans (Maina et al. 2008; Amari et al. 2012). The 1H-NMR spectrum for EPSB-soluble fraction (Figure 6A), revealed anomeric signals characteristic of glucosyl residues linked through α-(1→6) (98.5%) and α-(1→3) (1.5%) linkages appeared at δ 4.97 and δ 5.3, respectively. The other protons appeared from δ 3.4 to 4.1: δ = 3.55 (dd, 1H, J = 3.2 Hz, J = 9.8 Hz, H-2), 3.48 (t, 1H, J = 9.2 Hz, J = 9.6 Hz, H-3), 3.71 (t, 1H, J = 9.2 Hz, J = 9.6 Hz, H-4), 3.90 (d, J = 8.4, 1H, H-5), 3.74 (d, J = 7.48, H-6a), 3.98 (d, J = 9.76, 1H, H-6b). The 13C-NMR spectrum (Figure 6B) shows six signals, among them, those appearing at δ 97.56 and δ 65.41, corresponding to C-1 and C-6, which are involved in α-(1 → 6) linkages. The linkage carbon resonance at δ 65.41 showed two correlation peaks (δ 3.74 and δ 3.98) in the HSQC spectrum (Additional file 1). The four remaining signals observed at δ 73.28, 70.06, 69.39, and 71.29 corresponded to C-4, C-5, C-3, and C-2, respectively. Full assignments of the proton and carbon resonances were secured from the TOCSY, COSY, NOESY, and HMBC data.

Figure 6.

RMN spectra of EPSB-soluble fraction. (A) 1H-NMR spectrum. (B) 13C-NMR spectrum.

These results are consistent with previous reported 1H- and 13C-NMR data for the dextran produced by W. confusa C39-2 strain with 97.6% α-(1 → 6) and 2.4% α-(1 → 3) linkages, respectively (Bounaix et al. 2009). The structure of the soluble EPSB dextran also resembled that of dextrans produced by W. confusa VTT E-90392 (0DSM 20194) (Maina et al. 2008) and W. cibaria CMGDEX3 (Ahmed et al. 2012).

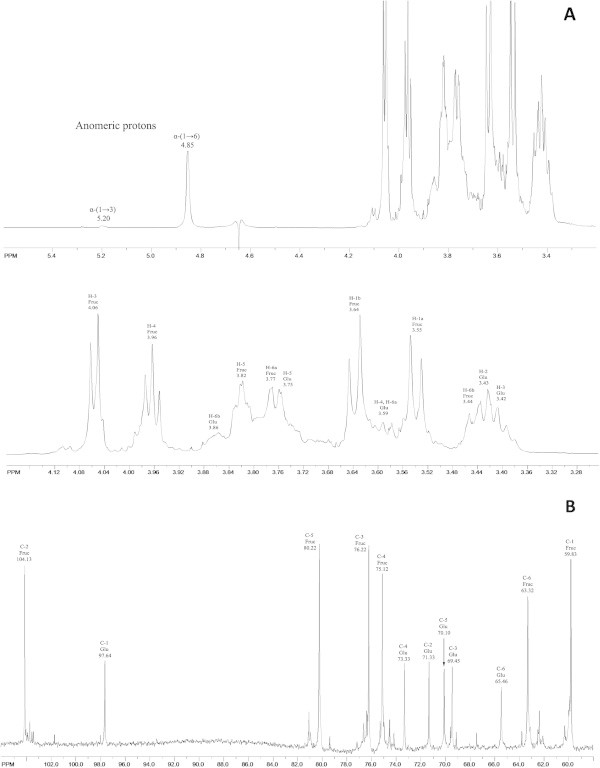

In other hand, the 1H- and 13C-NMR chemical shifts observed suggest that the polymer from the cell-associated fraction of isolated strain EPSB is a mixture that consist of a levan (79%) composed of linear chains of (2→6)-linked β-D-fructofuranosyl residues with β-(2→6) linkages, and a polymer of class 1 dextran (21%). The assignments of methylene and methine carbons were determined by a DEPT analysis (Additional file 1). The 13C-NMR spectrum gave three upfield resonances which were methylene (δC 59.83, 63.32, 65.46) while the remaining resonances were methines and one quaternary carbon (δC 104.13).

The 1H-NMR spectrum showed intense signals associated to the fructose moieties in the levan fraction (Figure 7A), which were detected at δ 3.77 (d, J =12.6 Hz, H-6a), 3.44 (d, J =11.2 Hz, H-6b), δ 3.55 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, H-1a), δ 3.64 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, H-1b), δ 3.82 (ddd, J = 2.8 Hz, J = 7.7 Hz, J = 7.7 Hz, H-5), δ 3.96 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, J = 8.4 Hz, H-4), δ 4.06 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-3). The COSY spectrum was used to detect cross peaks between H-3/H-4, H-4/H-5, and H-5/H-6. The HMBC spectrum (Additional file 1) showed the presence of cross peaks between H3/C4, H4/C6, H4/C3, H1/C3, and H1/C2 as it was reported previously (Dahech et al. 2013). This result allowed to confirm the presence of β-(2→6) linkage between two fructofuranosyl moieties, but the β-(2→6) linkage was confirmed only by the presence of a downfield shifted signal at δ 63.32 (C-6) in the 13C-NMR spectrum as reported previously (Tomašić et al. 1978). It has been shown that normally glycosylation induces a downfield shift of δ 4-10 (Newbrun and Baker 1968). In the 13C-NMR spectrum (Figure 7B) of the EPSB cell-associated polymer were detected six main resonance shifts at δ 59.83 (C-1), δ 63.32 (C-6), δ 75.12 (C-4), δ 76.22 (C-3), δ 80.22 (C-5), and δ 104.13 (C-2) relating to a quaternary anomeric carbon, corresponding to levan. These results are also similar to those observed previously in levan produced by L. mesenteroides B-512 F (Morales-Arrieta et al. 2006) and Streptococcus mutans (Shimamura et al. 1987).

Figure 7.

RMN spectra of EPSB-soluble and cell-associated fractions. (A) Full 1H NMR spectrum (upper graph) and region between 4.2 and 3.1 nm (bottom graph). (B) 13C-NMR spectrum.

According to 1D- and 2D-NMR analysis, the second polymer in the mixture corresponded to dextran. The chemical shifts for the 6 carbons of the dextran were linked to those of the seven hydrogens as determining by using HSQC (Additional file 1). The characteristically downfield anomeric carbon (δ 97.64) and anomeric hydrogen (d, δ 4.85, J = 1.4 Hz) was considered as the starting point for the analysis of the 1H-1H COSY (Additional file 1) for connectivity within the spin system. The two diasterotopic H-6 hydrogens at δ 3.86 (m) and at δ 3.59 (m) in the 1H spectrum were also useful markers and attached to the carbon at δ 65.46 in the 13C spectrum. The other protons appeared in the spectrum at: δ = 3.43 (H-2), 3.42 (H-3), 3.59 (H-4 and H-6a), 3.75 (H-5), 3.86 (H-6b). In the 13C-NMR spectrum, the peaks corresponding to individual carbons were identified at δ C-4 (73.33), C-2 (71.33), C-5 (70.10), C-3 (69.45), and C-6 (65.46), respectively (Figure 7B).

Polymers synthesized by GTF from sucrose by diverse LAB isolated from different traditional fermented sources include linear and branched dextrans, dextran and levan mixtures, and also inulin like polymers, indicating a high natural diversity of these EPS, particularly interesting considering the wide geographical distribution of these fermented products: palm wine from Africa, cereal sourdoughs and fermented vegetables from Europe, traditional kimchi from Korea, and maize sourdough and a fermented pulque beverage from Mexico (Table 1). The production of a dextran and levan polymers mixture was previously detected in the cell-associated fraction of cultures on MRS-sucrose of L. mesenteroides G15 strain isolated from a French cereal sourdough as revealed by 13C-NMR spectroscopy (Bounaix et al. 2009). Interestingly, detection of genes coding for glucosyltransferase and enzymes demonstrated their respective presence in isolated L. mesenteroides strains from Bulgarian fermented vegetables, but activity of putative fructosyltransferase was detected only in the presence of raffinose instead sucrose (Vasileva et al. 2012). Additionally, the production of an inulin-like polymer with β-(2→1) glycosidic linkages, was demonstrated by 13C-NMR in a cell-associated fructosyltrasferase in cultures containing 20 g/L sucrose of L. citreum strain CW isolated from pozol, a Mexican fermented maize sourdough (Olivares-Illana et al. 2002) (Table 1).

Several polymers described in Table 1 have relevant potential applications, as it has been proposed that branched dextrans possess prebiotic properties, demonstrating that these polymers and their oligodextrans may be substrates for butyric acid production by intestinal microbiota. Additionally, highly linear dextrans are considered highly soluble and were proposed to confer viscosity properties associated to their molecular weight (Maina et al. 2008). Furthermore, levans were shown to exhibit prebiotic effects, attracting attention for its antitumor properties, cholesterol-lowering properties and application such eco-friendly adhesive and as a promising bio-thickener in food industry (Patel et al. 2011). Pulque beverage is consumed directly from the fermentation vessel without further antimicrobial treatment such as pasteurization or filtration, as a consequence, living microorganisms are consumed. Additionally, pulque has been traditionally considered has a healthy beverage due to its nutrient content and used as a natural medicine to control several diseases (Escalante et al. 2012). Even though proposed healthy effects have been limited to traditional pharmacopoeia, further evidence on the possible probiotic effect of LAB involved in the fermentation process as the possible prebiotic activity of dextran or dextran and levan mixture produced by LAB such L. kimchii EPSA and EPSB strains requires further investigation.

Conclusions

EPSA and EPSB producing strains of L. kimchii isolated from traditional Mexican pulque and their polymers described in this contribution are to our knowledge the first study reporting the production and characterization of EPS produced by this LAB isolated from traditional fermented sources. L. kimchii was previously identified as the main LAB present in agave sap aguamiel and during the first hours of pulque fermentation. Although further studies are required to provide additional information concerning the enzymatic properties of the GTF responsibles for the synthesis of dextrans and levan by L. kimchii EPSA and EPSB strains, results presented in this contribution are highly relevant for pulque microbiology. In effect, while L. mesenteroides has traditionally been considered the main bacteria responsible for polymer production during pulque fermentation, this study provides new evidence regarding the diversity of EPS produced by LAB involved in the production of this traditional Mexican beverage.

Methods

Aguamieland pulquesampling

Fresh aguamiel and fermented pulque were collected from the town of Hiutzilac, State of Morelos, Mexico (Central Mexico Plateau) and transported to the laboratory, where controlled fermentations were performed by the addition of fresh sap to previously fermented pulque as described before (Escalante et al. 2008). Samples of aguamiel, after inoculation (mixing of sap with previously fermented pulque) (sample T0) and after 3 and 6 h of fermentation, were serially diluted in 0.1% tryptone water (DIFCO), and aliquots of 0.1 mL were plated on APT-agar (DIFCO) and APT-agar supplemented with 20% (w/v) sucrose (APTS). Plates were then incubated at 30°C for 24 h to determine the total count of LAB and EPS-producing LAB, respectively.

EPS-producing LAB isolation and identification

An average of 100 colonies of EPS-producing LAB from representative plates of aguamiel and each pulque sample were isolated, Gram stained, observed with a light microscope to verify colony purity, and tested for catalase activity. The purified isolated colonies were grown on APTS plates (4 colonies per plate), where the colony morphology and size were visually screened. Fast growing colonies were selected and visually screened for unique EPS-producing phenotypes resulting in the identification of two distinct EPS-producing colonies designated as EPSA and EPSB. Finally, selected isolates were conserved in 50% glycerol at -70°C and identified by 16S rDNA sequencing as described previously (Escalante et al. 2004; Escalante et al. 2008) by using fd1 + rd1 primer set resulting in the amplification of the entire 16S rRNA gene (Weisburg et al. 1991). Comparison was performed against the non-redundant nucleotide database using the online nucleotide BLAST application in the NCBI homepage. To corroborate their molecular identity, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 6 software (Tamura et al. 2013) including reference and type 16S rDNA sequences retrieved from the NCBI database.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis of EPS-producing LAB

EPS-producing LAB were grown on APTS plates until a viscous morphology was observed. Collodion-coated electron microscope grids were placed on growing colonies, and maintained for four additional days at room temperature to promote LAB adhesion to the grid. The grids were then lifted from the APTS plates and placed on a porcelain spot dish for further processing. Fixation was performed by 1 h of exposure to 1% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in pH 7.4, 0.1 M phosphate buffer, followed by washing with the same buffer, post-fixing with 1% osmium tetroxide in buffer for 30 min and dehydration with graded alcohols. Throughout the procedure, special care was taken when changing solutions to avoid EPS dispersion and damage to the grid surface. The samples were then dried under critical CO2 (Sandri-780; Tousimis), gold coated (JFC-110 ion sputter; JEOL), and observed with a JEOL JSM-7600 F Field Emission SEM.

Growth kinetics of EPS-producing strains

Flask cultures were performed in 50 mL of APT broth at 30°C and 150 rpm to define optimum growth conditions for selected LAB isolates and to achieve adequate enzyme activities and EPS production. The OD600nm was determined and adjusted to 0.2 before inoculation in a 2.8 L flask with 560 mL of APT broth and incubation for 6 – 8 h at 30°C and 150 rpm. Microbial growth was followed by the OD600nm measurements and the pH was monitored each hour.

GTF activity assay

GTF activity was determined in cell-free supernatants and in harvested cell fractions by measuring the release of reducing sugars using the DNS technique (Sumner and Howell 1935) in the presence of 10% (w/v) sucrose in 100 mM, pH 5.4 acetate buffer. Incubation was performed in an Eppendorf Thermomixer Comfort device (Eppendorf, Hamburg) at 30°C. One activity unit (U) of total GTF activity is defined as the amount of enzyme producing 1 μmol of glucose per minute from GTF activity under the assay reaction conditions (Morales-Arrieta et al. 2006). Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bradford 1976), using the Bio-Rad reagent and BSA (BioRad) as standards.

In vitroEPS production

EPS were produced from the supernatant and cell-associated enzyme fractions. For this purpose, the soluble GTF fraction was precipitated from the supernatant cultures by the addition of one volume of 50% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 5000 and centrifugation (7,000 × g, 5 min at 4°C). The pellet of cells containing the cell-associated GTF fraction, was washed three times and resuspended in a minimal volume of 0.1 mM, pH 5.4 acetate buffer (Quirasco et al. 1999). Polymer was produced in both fractions in the same buffer conditions containing 10% sucrose in final volume of 600 μL and incubated at 30°C and 100 rpm for 14 h (New Brunswick Scientific G24 shaker). The polymers produced from the cell-associated fraction were centrifuged as above to separate them from the cell whereas polymer produced from the supernatant fraction was precipitated by the addition of one volume of absolute ethanol and harvested by centrifugation (2,367 × g, 5 min at 4°C). Both polymers were resuspended in a minimum volume of distilled water and dialyzed against distilled water, eluted in a cellulose membrane (Mw cutoff of 12,400 Da SIGMA-ALDRICH), and dried in a LABCONO FreeZone 5.4 freeze-dryer.

Hydrolysis of EPS

Soluble and cell-associated ESPA and EPSB polymer fractions were subjected to enzyme hydrolysis with Fructozyme L® (kindly provided by Novozymes), a commercial enzymatic preparation obtained from Aspergillus niger combining endo- and exoinulinase activities toward β-(2→1) and endo-β-(2→6) D-Frup linkages, in pH 5, 0.05 M, acetate buffer, at 60°C; Dextranase (Enzimas y Productos Químicos S.A. de C.V., Mexico City), which hydrolyses α-(1→6) D-Glcp linkages, in 0.05 M acetate buffer, pH 5, at 50°C; recombinant E. coli (levB) endolevanase from Bacillus licheniformis, which degrades endo-β-(2→6) D-Frup linkages (kindly provided by Dr. A. López-Munguía) in pH 6, 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer at 37°C; and endoinulinase Novozym® 960 (Batch KNN00120 from Novozymes), which degrades endo-β-(2→6) D-Frup linkages, in pH 6, 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer at 60°C. Acid hydrolysis was performed with H2SO4 5% (v/v) at 95°C, 1 hr.

Enzymatic and acid hydrolysis assays were performed in a volume of 0.5 mL containing 2% w/v of EPS and were incubated for 12 h. Inulin from L. citreum, levan of B. subtilis (Ortiz-Soto et al. 2004) and dextran of L. mesenteroides B-512 PM 69,000 Da (Sigma) were used as controls. Hydrolyzed samples were analyzed by TLC using pre-coated TLC-sheets of Alugram® Xtra Sil G/UV254 with a mobile phase of 11:3:11:1 acetic acid:chloroform:ethanol:water mixture. The spots of products were detected by spraying with an alcoholic solution of α-naphthol and sulfuric acid, followed by heating at 120°C for 3 min.

1H- and 13C-NMR analysis of EPS

The freeze-dried samples of each polymer were dissolved in 1.0 mL of D2O (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.). NMR spectrum of soluble EPSA polymer was recorded on an Advance 700 MHz spectrometer (Varian) operating at 700 MHz for 1H-NMR and 175 MHz for 13C-NMR. NMR spectra of both EPSB fractions were recorded on an Advance 400 MHz spectrometer (Varian) operating at 400 MHz for 1H-NMR and 100 MHz for 13C-NMR. All measurements were performed at room temperature and were obtained using a 1.0 s relaxation delay. The data were acquired and processed using VNMRJ 2.0 software. Chemical shifts are listed in parts per million (ppm) and were made on the basis of 1H-1H COSY, 1H-1H TOCSY, NOESY, DEPT, HSQC, and HMBC spectral analysis (Additional file 1).

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: 2-D NMR analysis of EPSA and EPSB polymers. 1H-1H COSY, 1H-1H TOCSY, NOESY, HSQC, and HMBC spectral analysis of EPSA and EPSB-soluble fractions and DEPT, 1 H- 1H COSY, 1H-1H TOCSY, NOESY, HSQC, and HMBC spectral analysis of EPSB-soluble and cell-associated fractions. (PDF 1 MB)

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by PAPIIT-UNAM project IN207914. We thank to Mercedes Enzaldo (IBT-UNAM); Alejandro Camacho Cruz and Ma. Antonieta Silva (Facultad de Química, UNAM), for their technical support; Dr. Fernando García Hernández (IFC-UNAM), for biological sample preparation for SEM observation; Dr. Omar Novelo Peralta (IIM-UNAM) for SEM support of EPS samples; and M.C. Silvia Marquina Bahena (CIQ, UAEM) for RMN sample analysis support; Oscar Martínez for the critical review of this document.

Abbreviations

- EPS

Extracellular polysaccharides

- LAB

Lactic acid bacteria

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- GTF

Glycosyltransferase(s).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ITR and MRA, characterized the growth profile of L. kimchii, preformed GTF activity assays, produced in vitro both EPSA and EPSB polymers, and performed structural characterization of EPS by enzymatic and acid hydrolysis. AMM, performed 1H- and 13C-NMR structural characterization of both EPSA and EPSB polymers. MGG and RCM performed pulque fermentation, EPS-producing LAB screening, purification and identification of studied LAB strains. MRA, MGG, ALM, FB, and AE conceived this study and designed experiments. MRA, AMM, ALM, FB, and AE wrote the paper. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ingrid Torres-Rodríguez, Email: ingrid88@comunidad.unam.mx.

María Elena Rodríguez-Alegría, Email: maelena@ibt.unam.mx.

Alfonso Miranda-Molina, Email: amiranda@ibt.unam.mx.

Martha Giles-Gómez, Email: margiles@unam.mx.

Rodrigo Conca Morales, Email: roy_er8@hotmail.com.

Agustín López-Munguía, Email: agustin@ibt.unam.mx.

Francisco Bolívar, Email: bolivar@ibt.unam.mx.

Adelfo Escalante, Email: adelfo@ibt.unam.mx.

References

- Ahmed RZ, Siddiqui K, Arman M, Ahmed N. Characterization of high molecular weight dextran produced by Weissella cibaria CMGDEX3. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;90:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amari M, Arango LFG, Gabriel V, Robert H, Morel S, Moulis C, Gabriel B, Remaud-Siméon M, Fontagné-Faucher C. Characterization of a novel dextransucrase from Weissella confusa isolated from sourdough. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;97:5413–5422. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Bekker JP, van Wyk N, du Toit C, Dicks LMT, Kossmann J. Exopolysaccharide production by lactose-hydrolyzing bacteria isolated from traditionally fermented milk. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;131:260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounaix M-S, Gabriel V, Morel S, Robert H, Rabier P, Remaud-Siméon M, Gabriel B, Fontagné-Faucher C. Biodiversity of exopolysaccharides produced from sucrose by sourdough lactic acid bacteria. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:10889–10897. doi: 10.1021/jf902068t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounaix M-S, Gabriel V, Robert H, Morel S, Remaud-Siméon M, Gabriel B, Fontagné-Faucher C. Characterization of glucan-producing Leuconostoc strains isolated from sourdough. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;144:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chellapandian M, Larios C, Sanchez-Gonzalez M, Lopez-Munguia A. Production and properties of a dextransucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides IBT-PQ isolated from “pulque”, a traditional Aztec alcoholic beverage. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;21:51–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.2900560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colson P, Jennings HJ, Smith IC. Composition, sequence, and conformation of polymers and oligomers of glucose as revealed by carbon-13 nuclear magentic resonance. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:8081–8087. doi: 10.1021/ja00833a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahech I, Fakhfakh J, Damak M, Belghith H, Mejdoub H, Belghith KS. Structural determination and NMR characterization of a bacterial exopolysaccharide. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;59:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrmann MA, Freiding S, Vogel RF. Leuconostoc palmae sp. nov., a novel lactic acid bacterium isolated from palm wine. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:943–947. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.005983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom H-J, Seo DM, Han NS. Selection of psychrotrophic Leuconostoc spp. producing highly active dextransucrase from lactate fermented vegetables. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;117:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante A, Rodríguez ME, Martínez A, López-Munguía A, Bolivar F, Gosset G. Characterization of bacterial diversity in Pulque, a traditional Mexican alcoholic fermented beverage, as determined by 16S rDNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;235:273–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante A, Giles-Gómez M, Hernandez G, Cordova Aguilar M, Lopez-Munguia A, Gosset G, Bolivar F. Analysis of bacterial community during the fermentation of pulque, a traditional Mexican alcoholic beverage, using a polyphasic approach. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;124:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante A, Giles-Gómez M, Esquivel Flores G, Matus Acuña V, Moreno-Terrazas R, López-Munguía A, Lappe-Oliveras P. Pulque Fermentation. In: Hui YH, editor. Handb. Plant-Based Fermented Food Beverage Technol., Second Edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012. pp. 691–706. [Google Scholar]

- Giraffa G. Studying the dynamics of microbial populations during food fermentation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Chun J, Han H-U. Leuconostoc kimchii sp. nov., a new species from kimchi. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1915–1919. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-5-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemhuis H, Pijning T, Dobruchowska JM, van Leeuwen SS, Kralj S, Dijkstra BW, Dijkhuizen L. Glucansucrases: Three-dimensional structures, reactions, mechanism, α-glucan analysis and their implications in biotechnology and food applications. J Biotechnol. 2013;163:250–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maina NH, Tenkanen M, Maaheimo H, Juvonen R, Virkki L. NMR spectroscopic analysis of exopolysaccharides produced by Leuconostoc citreum and Weissella confusa. Carbohydr Res. 2008;343:1446–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minervini F, De Angelis M, Surico RF, Di Cagno R, Gänzle M, Gobbetti M. Highly efficient synthesis of exopolysaccharides by Lactobacillus curvatus DPPMA10 during growth in hydrolyzed wheat flour agar. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;141:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Arrieta S, Rodríguez ME, Segovia L, López-Munguía A, Olvera-Carranza C. Identification and functional characterization of levS, a gene encoding for a levansucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-512 F. Gene. 2006;376:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbrun E, Baker S. Physico-chemical characteristics of the levan produced by Streptococcus salivarius. Carbohydr Res. 1968;6:165–170. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)81506-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H-M, Cho Y-J, Kim BK, Roe J-H, Kang S-O, Nahm BH, Jeong G, Han H-U, Chun J. Complete genome sequence analysis of Leuconostoc kimchii IMSNU 11154. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:3844–3845. doi: 10.1128/JB.00508-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares-Illana V, Wacher-Rodarte C, Le Borgne S, López-Munguía A. Characterization of a cell-associated inulosucrase from a novel source: A Leuconostoc citreum strain isolated from Pozol, a fermented corn beverage of Mayan origin. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;28:112–117. doi: 10.1038/sj/jim/7000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Soto ME, Olivares-Illana V, López-Munguía A. Biochemical properties of inulosucrase from Leuconostoc citreum CW28 used for inulin synthesis. Biocatal Biotransformation. 2004;22:275–281. doi: 10.1080/10242420400014251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palomba S, Cavella S, Torrieri E, Piccolo A, Mazzei P, Blaiotta G, Ventorino V, Pepe O. Polyphasic screening, homopolysaccharide composition, and viscoelastic behavior of wheat sourdough from a Leuconostoc lactis and Lactobacillus curvatus exopolysaccharide-producing starter culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2737–2747. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07302-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J-H, Ahn H-J, Kim S, Chung C-H. Dextran-like exopolysaccharide-producing Leuconostoc and Weissella from kimchi and its ingredients. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2013;22:1047–1053. doi: 10.1007/s10068-013-0182-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Majumder A, Goyal A. Potentials of exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria. Indian J Microbiol. 2011;52:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0148-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirasco M, Lopez-Munguia A, Remaud-Simeon M, Monsan P, Farres A. Induction and transcription studies of the dextransucrase gene in Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-512 F. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5504–5509. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5504-5509.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Marroquin A, Hope PH. Agave juice, fermentation and chemical composition studies of some species. J Agric Food Chem. 1953;1:246–249. doi: 10.1021/jf60003a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour FR, Knapp RD, Bishop SH. Determination of the structure of dextran by 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res. 1976;51:179–194. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)83325-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour FR, Knapp RD, Jeanes A. Structural analysis of levans by use of 13C-n.m.r. spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res. 1979;72:222–228. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)83940-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura A, Tsuboi K, Nagase T, Ito M, Tsumori H, Mukasa H. Structural determination of D-fructans from Streptococcus mutans, serotype b, c, e, and f strains, by 13C-n.m.r. spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res. 1987;165:150–154. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(87)80091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla R, Shukla S, Bivolarski V, Iliev I, Ivanova I, Goyal A. Structural characterization of insoluble dextran produced by Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-1149 in the presence of maltose. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2011;49:291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner JB, Howell SF. A method for determination of saccharase activity. J Biol Chem. 1935;108:51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieking M, Kaditzky S, Valcheva R, Korakli M, Vogel RF, Ganzle MG. Extracellular homopolysaccharides and oligosaccharides from intestinal lactobacilli. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;99:692–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomašić J, Jennings HJ, Glaudemans CPJ. Evidence for a single type of linkage in a fructofuranan from Lolium perenne. Carbohydr Res. 1978;62:127–133. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)83384-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uzochukwu S, Balogh E, Loefler RT, Ngoddy PO. Structural analysis by 13 C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of glucans elaborated by gum-producing bacteria isolated from palm wine. Food Chem. 2001;73:225–233. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00291-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uzochukwu S, Balogh E, Loefler RT, Ngoddy PO. Structural analysis by 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of glucan extracted from natural palm wine. Food Chem. 2002;76:287–291. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00274-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meulen R, Grosu-Tudor S, Mozzi F, Vaningelgem F, Zamfir M, Font de Valdez G, De Vuyst L. Screening of lactic acid bacteria isolates from dairy and cereal products for exopolysaccharide production and genes involved. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;118:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hijum SAFT, Kralj S, Ozimek LK, Dijkhuizen L, van Geel-Schutten IGH. Structure-function relationships of glucansucrase and fructansucrase enzymes from lactic acid bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:157–176. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.157-176.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileva T, Iliev I, Amari M, Bivolarski V, Bounaix M-S, Robert H, Morel S, Rabier P, Ivanova I, Gabriel B, Fontagné-Faucher C, Gabriel V. Characterization of glycosyltransferase activity of wild-type Leuconostoc mesenteroides strains from bulgarian fermented vegetables. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;168:718–730. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9812-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu B, Chen M, Crawford RJ, Ivanova EP. Bacterial extracellular polysaccharides involved in biofilm formation. Molecules. 2009;14:2535–2554. doi: 10.3390/molecules14072535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: 2-D NMR analysis of EPSA and EPSB polymers. 1H-1H COSY, 1H-1H TOCSY, NOESY, HSQC, and HMBC spectral analysis of EPSA and EPSB-soluble fractions and DEPT, 1 H- 1H COSY, 1H-1H TOCSY, NOESY, HSQC, and HMBC spectral analysis of EPSB-soluble and cell-associated fractions. (PDF 1 MB)