Abstract

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released by soil microorganisms influence plant growth and pathogen resistance. Yet, very little is known about their influence on herbivores and higher trophic levels. We studied the origin and role of a major bacterial VOC, 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BD), on plant growth, pathogen and herbivore resistance, and the attraction of natural enemies in maize. One of the major contributors to 2,3-BD in the headspace of soil-grown maize seedlings was identified as Enterobacter aerogenes, an endophytic bacterium that colonizes the plants. The production of 2,3-BD by E. aerogenes rendered maize plants more resistant against the Northern corn leaf blight fungus Setosphaeria turcica. On the contrary, E. aerogenes-inoculated plants were less resistant against the caterpillar Spodoptera littoralis. The effect of 2,3-BD on the attraction of the parasitoid Cotesia marginiventris was more variable: 2,3-BD application to the headspace of the plants had no effect on the parasitoids, but application to the soil increased parasitoid attraction. Furthermore, inoculation of seeds with E. aerogenes decreased plant attractiveness, whereas inoculation of soil with a total extract of soil microbes increased parasitoid attraction, suggesting that the effect of 2,3-BD on the parasitoid is indirect and depends on the composition of the microbial community.

Keywords: 2,3-butanediol; acetoin; induced systemic resistance; maize; volatile organic compounds

INTRODUCTION

Terrestrial plants are exposed to at least three of the four ‘Empedoclian elements’, soil, water, and air, and through these, they are constantly interacting with a multitude of organisms (van Dam 2009). Some of these organisms are mutualistic, whereas others are parasitic or pathogenic. To survive among such a diverse community of consumers, plants have evolved various defence strategies, including an inducible immune system that recognizes microbes and insects and reprogrammes the metabolism to withstand the attack (Howe & Jander 2008; Thomma et al. 2011; Marti et al. 2012; Huffaker et al. 2013). An integral component of many plant defence responses is the formation and release of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (D’Alessandro et al. 2006). VOC signalling is not limited to the phyllosphere, but occurs also belowground in the rhizosphere, for instance between plants and entomopathogenic nematodes (Rasmann et al. 2005), as well as between plants and microorganisms (Kai et al. 2009).

Certain rhizobacteria have been reported to emit VOCs that promote growth and influence the defence responses of their host plants (Bailly & Weisskopf 2012). Among the first bacterial volatiles that were found to confer plant resistance was 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BD; Ryu et al. 2004). Microbes synthesize 2,3-BD from pyruvate by a condensation and oxidation step, which yields the precursor acetoin. Acetoin is then reduced to 2,3-BD by an NADH-dependent dehydrogenase (Nielsen et al. 2010). Various combinations of the three different stereoisomers (R,R-, S,S- and meso-2,3-BD) are produced by different microorganisms. Since the original demonstration that exogenous application of a racemic mixture of 2,3-BD or the exposure to 2,3-BD-producing strains of Bacillus subtilis triggers resistance against the bacterial pathogen Erwinia carotovora in Arabidopsis thaliana (Ryu et al. 2004), several studies have demonstrated a positive effect of this volatile compound on plant resistance. In tobacco, 2,3-BD produced by the rhizobacterium Pseudomonas chlororaphis induced resistance against E. carotovora (Han et al. 2006). The stereochemistry of 2,3-BD was found to be important for this effect, as S,S-2,3-BD, contrary to R,R-2,3-BD, did not activate plant resistance (Han et al. 2006). Application of 2,3-BD to Nicotiana benthamiana primed the expression of genes encoding for basic PR-proteins and increased resistance against the hemibiotrophic fungus Colletotrichum orbiculare, supporting the hypothesis that 2,3-BD triggers a defence response similar to ‘induced systemic resistance’ (ISR) (Cortes-Barco et al. 2010). Recently, the precursor acetoin was also demonstrated to trigger ISR against Pseudomonas syringae in A. thaliana (Rudrappa et al. 2010). Strikingly, most experiments on the role of bacterial VOCs in plant–environment interactions, including the studies on the role of microbial 2,3-BD, have been conducted in a sterile Petri dish environment, and little information is available about the importance of microbial volatiles in a soil context.

Whereas the effects of bacterial volatiles on pathogen resistance and plant growth promotion are well documented (Bailly & Weisskopf 2012), few studies have addressed their plant-mediated effects on insects and their natural enemies. ISR, which can also be triggered by bacterial volatiles (Ryu et al. 2004), has been associated with increased insect resistance in A. thaliana: Plants growing in the presence of the ISR-inducing Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS417r were more resistant to the generalist herbivore Spodoptera exigua, whereas the specialist Pieris rapae was not affected. The attraction of the parasitic wasp Cotesia rubecula remained unaffected by the presence of the bacterium (Van Oosten et al. 2008). From these results and a number of other studies on microbial effects (Pineda et al. 2010; Neal & Ton 2013), it can be expected that volatiles of soil-borne bacteria may increase plant resistance against insects, but remain neutral for higher trophic levels. Bacterial volatiles can also have direct behavioural effects on herbivores and their natural enemies (Davis et al. 2013). The Mexican fruit fly Anastrepha ludens for instance was attracted by volatiles produced by the Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus (Robacker & Flath 1995). In addition, bacteria in the honeydew of pea aphids were found to increase the attraction of predatory hoverflies (Leroy et al. 2011). Whether soil-borne microorganisms have similar effects remains unknown.

In this study, we demonstrate that healthy maize seedlings occasionally emit considerable amounts of an isomeric mixture of 2,3-BD, which is absent in plants cultivated in autoclaved soil. We isolated various endophytic bacteria from microorganism-inoculated seeds and identified one 2,3-BD-emitting isolate as Enterobacter aerogenes. We showed that E. aerogenes-derived emission of 2,3-BD influences resistance to pathogens and herbivorous insects, and affects tritrophic interactions. Together, our study reveals a considerable impact of microbial volatiles from enodphytic bacteria on interactions between plants, pathogens, herbivores and even the natural enemies of these herbivores.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plants, microbes and insects

Most experiments in this study were conducted in growth chambers under non-sterile conditions. Maize (Zea mays var. Delprim) seeds were rinsed with 70% ethanol followed by rinsing with sterile deionized water and placed individually in plastic pots (10 cm high, 4 cm diameter) filled with autoclaved potting soil (Aussaaterde; Ricoter, Aarberg, Switzerland; 121 °C for 1 h, repeated after 24 h). For some experiments, the soil was re-inoculated with 25 mL of a water extract with soil microorganisms. The extract was prepared by incubating 50 mg potting soil (1:1 mix of ‘Aussaat- und Pikiererde 191’ and ‘Zimmerpflanzenerde’, Ricoter, Aarberg, Switzerland) for 4–5 h into 250 mL of tap water before passing it over a house-hold sieve. The ‘Aussaat und Pikiererde’ consisted of a mixture of 25% garden compost (composted at 70–75%°C), 12% vol sand and 63% vol white peat, with a pH of 7 and a salt content of 1.5 mS. The ‘Zimmerpflanzenerde’ consisted of an equal mix of compost, wood-fibre and cocopeat at a pH of 6.8. Taken together, this resulted in a rich substrate that was found to be ideal for the healthy growth of maize seedlings while at the same time harbouring a rich community of microorganisms, including both bacteria and fungi. Control soil received 25 mL of tap water without soil microbes. To obtain endophyte-colonized plants, maize seeds were first incubated for 3–4 h in an autoclaved 10 mm MgSO4 solution containing 108 cfu mL−1 of an overnight culture of E. aerogenes or in MgSO4 solution before planting them in autoclaved soil. Bacteria for plant treatments were cultivated in plastic tubes (50 mL 114 × 28 mm, PP microtubes; Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) containing 20 mL LB medium (Difco, LB broth, Miller, Le Pont de Claix, France) overnight at 28 °C and 250 r.p.m. (Innova 4230; New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, NJ, USA). Bacterial pellets were washed three times with MgSO4 before incubation to remove residual LB medium. All plant seedlings were grown in a growth chamber at 30 °C, 60% relative humidity (RH), 16L:8D and 25 000 lm m−2. All seedlings were screened for the presence/absence of 2,3-BD prior to the experiments (see below). The caterpillars Spodoptera littoralis (Boisduval) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and the solitary endoparasitoid Cotesia marginiventris (Cresson) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) were reared as described before (Turlings et al. 2004). Adult parasitoids were kept in plastic cages at a sex ratio of approximately 1:2 (male:female) and were provided with moist cotton wool and honey as food source. The cages were kept in an incubator (25±1 °C; 16L:8D) and transferred to the laboratory 30 min before the experiments.

Collection and analyses of VOCs

VOCs of 10- to 12-day-old maize seedlings were collected using either the MAD-VOC-collection system as described (Ton et al. 2007). In the first experiment, the headspace volatiles from seedlings grown in autoclaved soil with and without added soil microorganisms and with and without infestation by S. littoralis caterpillars for 24 h (n = 12).Volatile compounds were then analysed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and quantified by gas chromatography with flame ionization detector (GC-FID) on an apolar column (HP-1MS) as described (D’Alessandro & Turlings 2005). The isomeric composition of 2,3-BD was determined by analysing VOC extracts on a chiral column (CycloSil-B, 30 m, 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 μm film thickness; Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) installed in the GC-MS and compared with authentic standards, including an isomeric mixture of 2,3-BD, meso (R,S)-2,3-BD (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), (2R,3R)-(−)- and (2S,3S)-(+)-BD (Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland). To determine the exact source of the 2,3-BD emission, maize seedlings grown in the presence of soil microorganisms were washed with autoclaved water and different parts (third leaf, sheath, and root, seed and soil) were excised and placed into a glass vial (75.5 × 22.5 mm; LDZ, Marin-Epagnier, Switzerland) with a septum in the lid. A solid phase microextraction (SPME) fibre (75 μm, carboxen-polydimethylsiloxane; Supelco, Buchs, Switzerland) was inserted through the septum and VOCs were adsorbed for 20 min at 40 °C. Subsequently, the fibre was automatically inserted in the injector port (250 °C), which was connected to a polar column (Innowax, 30 m, 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 μm film thickness; Agilent) of a GC-MS (Agilent 5973; transfer line 230 °C, source 230 °C, ionization potential 70 eV, scan range 33–250 amu). Helium at constant flow (0.9 mL min−1) was used as the carrier gas. Following injection, the column temperature was maintained at 40 °C for 3 min and then increased to 250 °C at 8 °C min−1, followed by a post-run of 5 min at 250 °C. Mass spectra were compared with those of the NIST 02 library, and retention times and spectra were compared with those of authentic standards. Compounds that were not identified by comparing retention times and spectra with those of pure standards are labelled with an N. To screen the seedlings for 2,3-BD for olfactometer experiments (see below), volatile collections were run for 1.5–3 h and VOCs were analysed by GC-FID as described above using a fast gradient (starting temperature 40 °C, ramp 8 °C min−1 to 60 °C, post-run 280 °C for 5 min).

Isolation and identification of E. aerogenes

To identify 2,3-BD-producing endophytic bacteria, seeds of the 10-day-old maize seedlings grown in the presence or absence of soil microbes were harvested and rinsed with water. Subsequently, seeds were vapour-phase sterilized for 3–5 h by placing them in a 10-L desiccator with a 250-mL beaker containing 100 mL bleach [10% Ca(ClO)2] and 3 mL concentrated HCl. After sterilization, seeds were rinsed with sterile water. Seeds were cut into two parts and one part of each seed was placed on an LB agar plate (Difco, LB Broth, Miller) and the other one on a PDA agar plate (potato dextrose agar; Difco, Brunschwig, Basel, Switzerland) and incubated for 24 h at 28 °C (LB plates) or room temperature (approximately 25 °C, PDA plates; n = 6). Subsequently, bacteria from both types of plates were cultivated in LB medium (Difco, LB Broth, Miller) in plastic tubes (50 mL 114 × 28 mm, PP; Sarstedt) overnight at 28 °C and 250 r.p.m. (Innova 4230, New Brunswick Scientific). These overnight cultures were again plated on LB and PDA plates and incubated as described previously. Twenty-four single colonies were randomly selected and transferred into liquid LB medium. All bacteria were stored in 25% glycol solution at −76 °C. DNA of the isolated bacterial strains was extracted (Promega Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit, Madison, WI, USA) and the 16S rRNA gene was PCR-amplified using universal eubacterial primers (GM3f, GM4r; Muyzer et al., 1995). Five strains were selected for identification based on their restriction fragment length pattern after digestion with HaeIII and TaqI, respectively, and the potential for 2,3-butanediol production in tyndallized maize seeds. Purified PCR products (Wizard PCR Clean-up; Promega) of the 16S rRNA gene were sent for sequencing (MWG-Biotech, Germany). Sequences, between 960 base pair (bp) and 1350 bp length were analysed using online tools available from RDP II (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). All five isolates turned out to be closely related Enterobacteriaceae. Partial and nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequences of isolated strains have been submitted to the EMBL database under the ENA accession numbers HG326201-HG326205. As the phylogenetic information of the 16S rRNA gene sequence is often insufficient for unambiguous identification of Enterobacteria to the species level, one isolate was further characterized by physiological tests using Enterobacteria-specific API 20E test strips (Bio Merieux, Nürtingen, Germany). Furthermore, morphology and motility of the isolate was determined by microscopy of cells grown at 35 °C on nutrient agar and LB plates. This isolate was termed ‘isolate 8’ and used for all further experiments. To confirm the identification of the isolate at the species level using an additional orthologous method, an overnight culture of isolate 8 was analysed with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization/time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI/TOF-MS) at Mabritec (Riehen, Switzerland) as described (Ziegler et al. 2012), and the obtained fingerprints of protein masses were analysed with SARAMIS™ (Spectral Archive and Microbial Identification System; AnagnosTec, Potsdam-Golm, Germany).

Plant colonization by E. aerogenes

To study endophytic colonization of 2,3-BD-producing E. aerogenes, we plated 100 μL of an overnight culture of the isolated strain (~108 cfu mL−1) on LB plates with a gradient of increasing concentrations of Rifampicin (0 < 150 mg mL−1). We then selected single colonies growing in the highest concentration of Rifampicin and subsequently inoculated maize seeds in an overnight culture of one of these Rifampicin-resistant strains (rif+), as described earlier. Similar to the maize seedlings treated with the wild-type strain (rif−), this resulted in seedlings that released high amounts of 2,3-BD into the phyllosphere. Various thin slides of different parts of surface-sterilized [vapour phase 30% Ca(ClO)2] and surface-disinfected (70% ethanol) seedlings without added bacteria were then incubated at room temperature on LB agar plates with Rifampicin (150 mg mL−1, rif+), and bacterial growth was visually examined during several days. This procedure enabled us to determine whether the resistant strains had colonized the plant and in which tissues the bacteria were present. The identity of the re-isolated bacteria was verified with API 20E test strips and restriction pattern analysis with HaeIII and TaqI, as described previously.

VOC emission by E. aerogenes

To confirm the capacity of E. aerogenes isolate 8 to produce 2,3-BD and its precursor acetoin from maize, we measured the release of both compounds by SPME, as described earlier. Maize seeds (n = 6) were tyndallized by boiling them three times for 10 min at 24 h intervals. Half of the seeds were then infected with E. aerogenes as described earlier, and volatile production was measured 3 d after infection.

Experiments with the Northern corn leaf blight Setosphaeria turcica

To test whether 2,3-BD influences pathogen resistance in maize, we measured plant colonization by the necrotrophic fungus S. turcica (anamorph: Exserohilum turcicum, Ascomycota: Pleosporaceae). The isolate was kindly provided by Michael Rostás (University of Würzburg, Germany) and cultivated on V8 agar in darkness under laboratory conditions. In the first experiment, we added 25 mL of 2,3-BD in water (2 mg mL−1, isomeric mixture, Fluka, ≥99%) to 8-day-old maize seedlings grown in autoclaved soil on the evening before the experiment. This concentration was chosen based on preliminary calibration experiments and resulted in maize seedlings that emitted similar amounts of 2,3-BD in the phyllosphere as seedlings with the added bacteria (Table 1). Additional seedlings were prepared with the same amounts of (±)-acetoin (3-hydroxy-2-butanone, Fluka, purum, mixture of monomer and dimer, ≥97.0%), (±)-2-butanol (Fluka, ≥99.5%) or water (n = 12). In addition, we selected E. aerogenes-colonized maize plants that released 2,3-BD (n = 12) and others that did not (n = 6). The following day, an 8-week-old Petri-dish culture of S. turcica was flooded with approximately 10 mL of an autoclaved 10 mm MgSO4 solution containing 0.015% Silwet L-77 and then brushed gently with a small paintbrush in order to detach the spores from the mycelium. The density of the spore suspension was determined by a Neubauer chamber and adjusted to approximately 5 × 104 spores mL−1. Maize plants were then inoculated by applying 100 μL spore suspension to the first, second and third leaf. The spores were spread homogeneously using a paintbrush. Seedlings of the same treatment were placed together in a moistened, closed plastic box (30 × 70 × 50 cm) for 16 h at >90% RH and ambient temperatures. The following morning, all plants were transferred to a climate chamber (23 °C, 60% RH, and light:dark 16:8 h, 25 000 lm m−2). Disease symptoms were allowed to develop for 3 d, after which the strength of infection was estimated by measuring the total necrotic and chlorotic areas measured using the program ‘Surface’ (Rostas et al. 2006). In the second experiment, we inoculated maize plants with spores of a 3-week-old Petri-dish grown culture of S. turcica, as described earlier. The 9-day-old plants were either treated with water or with synthetic 2,3-BD, and disease symptoms were measured 3 d after inoculation by collecting 5 leaves per treatment and staining with lactophenol trypan blue (Koch & Slusarenko 1990). The lengths of S. turcica germination hyphae were examined under a microscope (Olympus BX50W1, Olympus, Volketswil, Switzerland) and quantified using AnalySIS-D software (Soft Imaging System GmbH, Münster, Germany). In the third experiment, we tested the effect of 2,3-BD on S. turcica growth in vitro. Petri dishes filled with V8 agar were supplemented with different concentrations of 2,3-BD that were either directly dissolved in the medium (0–200 μg mL−1) or released into the headspace of the dish after inoculation (0–10 μg mL−1). The Petri dishes were inoculated with spores of S. turcica (approximately 5000 spores per Petri dish), sealed with parafilm, and mycelial growth was quantified 7 d after inoculation at room temperature (n = 5–6).

Table 1. Mean amounts ± SE (ng) of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) detected in the blends of 10-day-old healthy maize seedlings during a 3 h collection period.

| Treatment |

||

|---|---|---|

| Compounds | Without microorganisms |

With soil microorganisms |

| (R,R)-2,3-butanediol | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 154.6 ± 25.2 |

| (R,S)-2,3-butanediol | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 853.6 ± 142.5 |

| β-Myrcene | 11.2 ± 2.2 | 9.0 ± 0.7 |

| Linalool | 99.9 ± 17.3 | 98.5 ± 13.0 |

|

| ||

| Without microorganisms |

Without microorganisms and BD in airflow |

|

|

| ||

| (R,R)- and (S,S)-2,3-butanediol | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 304.6 ± 53.7 |

| (R,S)-2,3-butanediol | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1151.2 ± 503.0 |

| β-Myrcene | 11.7 ± 3.4 | 8.7 ± 1.6 |

| Linalool | 94.7 ± 23.0 | 79.9 ± 14.7 |

|

| ||

| Without microorganisms |

Without microorganisms and BD in soil |

|

|

| ||

| (R,R)- and (S,S)-2,3-butanediol | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 261.1 ± 86.2 |

| (R,S)-2,3-butanediol | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 384.1 ± 109.2 |

| β-Myrcene | 16.5 ± 1.9 | 12.2 ± 2.6 |

| Linalool | 121.0 ± 32.4 | 115.6 ± 35.2 |

BD, butanediol.

Experiments with the herbivore S. littoralis

To determine whether the addition of soil microorganisms affects larval feeding rate, 12 seedlings with or without soil microorganisms were infested with 20 L2 S. littoralis larvae and the leaves were excised after 24 h feeding and scanned into Adobe Photoshop (7.0). The consumed leaf-area was determined as described previously. We further compared the weight gain of S. littoralis larvae feeding on maize seedlings that were either grown in autoclaved soil with E. aerogenes, in autoclaved soil with synthetic 2,3-BD or in autoclaved soil only. For this, six second instar S. littoralis larvae were weighed (Mettler Toledo MX5 micro-balance, Greifensee, Switzerland) and placed into the whorl of a potted 10- to 12-day-old maize seedling. A cellophane bag (Celloclair, Liestal, Switzerland) over each plant prevented caterpillars from escaping, while permitting gas exchange. A total of 12 plants per treatment were prepared in this way and, subsequently, infested seedlings were placed in a completely randomized design in an incubator and kept at 30 °C, 60% RH, 16L:8D, and 25 000 lm m−2. Over 5 d, larvae were weighed daily and maize seedlings were replaced each day.

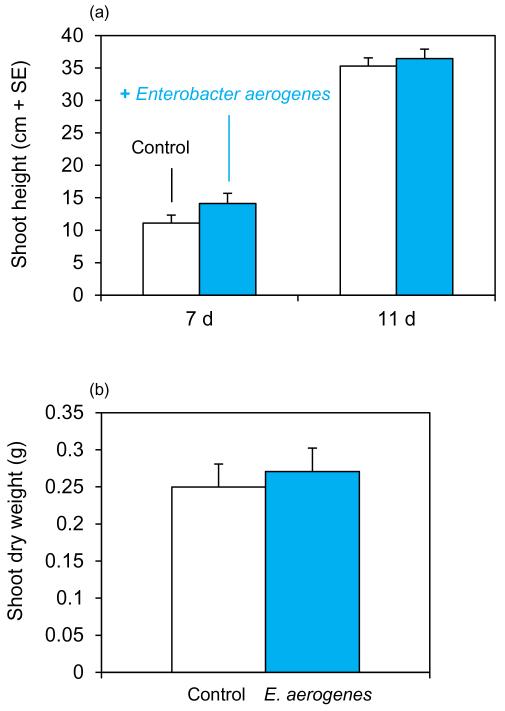

Plant growth promotion experiment

2,3-BD of bacterial origin has been reported to have plant growth-promoting effects in a Petri dish environment. To test whether colonization by the 2,3-BD-producing endophyte E. aerogenes improves maize growth, we measured the shoot height and shoot biomass accumulation of control and E. aerogenes-inoculated maize plants grown in autoclaved soil (n = 9–10).

Parasitoid experiments

To determine the influence of microbial volatiles on the attractiveness of maize plants to natural enemies of herbivores, we conducted several olfactometer experiments. We tested mated 2- to 4-day-old naïve and experienced C. marginiventris females. The latter were given experiences by allowing them to oviposit three to five times into second instar S. littoralis larvae while simultaneously being exposed to different HIPV blends as specified below. The different groups of wasps were kept separately in small plastic boxes with moist cotton wool and honey and released in a 4-arm olfactometer 1–3 h after their oviposition experience. Experiments were carried out using the 4-arm olfactometer (D’Alessandro & Turlings 2005). Cleaned and humidified air entered the different odour source vessels at 1.2 L min−1 (adjusted by a manifold with four flow-meters; Analytical Research System, Gainesville, FL, USA) via Teflon tubing and carried the VOCs through the arms to the olfactometer compartment. Half of the air (0.6 L min−1/olfactometer arm) was pulled out via a volatile collection trap. Wasps were released in groups of 6 into the central part of the olfactometer, and after 30 min, the wasps that had entered an arm of the olfactometer were counted and removed. Wasps that did not enter an arm after this time were removed from the central part of the olfactometer and considered as ‘no choice’. Six groups each of 6 wasps were tested during a 3 h sampling period by alternating between groups of naïve and experienced wasps. Each experiment was replicated at six different days with freshly prepared odour sources placed in different positions of the olfactometer. All parts of the olfactometer as well as the odour source vessels were washed with water and two solvents and dried at 200 °C after every replicate. All experiments were carried out between 1000 h and 1600 h. Using this set-up, four different experiments were conducted. Firstly, the influence of E. aerogenes on the attractiveness of S. littoralis-infested plants was tested by offering females of the parasitoid C. marginiventris a choice between the odours of caterpillar-infested plants with and without seed inoculation of E. aerogenes. Plants were infested with 20L2 S. littoralis larvae 24 h before the start of the experiments. The E. aerogenes-treated plants were first screened for volatile emission and only 2,3-BD volatile emitting plants were used in the olfactometer assay. Similarly, control plants were verified to be 2,3-BD free before the experiment. In the second experiment, the effect of soil inoculation with microorganisms on the attractiveness of maize plants to C. marginiventris was tested by offering naïve and experienced parasitoids a choice between the odours of S. littoralis-infested plants grown in autoclaved soil and re-inoculated soil as described earlier. Again, plants were first screened for 2,3-BD emissions. In the third experiment, naïve parasitoids were given a choice between similarly treated plants, but without S. littoralis infestation. In the fourth assay, we tested the direct and indirect effects of 2,3-BD on parasitoid attraction. For this, an isomeric mixture of synthetic 2,3-BD (Fluka) was added to odour source bottle with a healthy maize plant, either by directly releasing it into the air flow of via a microcapillary dispenser (D’Alessandro et al. 2006) or by adding it to the soil dissolved in water the evening before the experiment (500 μmol/pot). The concentrations of 2,3-BD in the headspace in both treatments corresponded to the ones found in the natural blend released by a plant growing in autoclaved soil with added microorganisms (Table 1).

Statistical analyses

The amounts of VOCs were analysed using t-tests. The disease symptoms on maize seedlings after inoculations with S. turcica and the weight of the S. littoralis larvae were analysed using one-way anovas. Differences between groups were analysed using the Tukey’s post-hoc test. Data that did not fulfil assumptions for parametric statistics were log-transformed prior to analysis. All comparisons were run on spss (14.0; SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). The functional relationship between the parasitoids’ behavioural responses and the different odour sources offered in the 4-arm olfactometer was examined with a log-linear model [a general linear model (GLM)]. As the data did not conform to simple variance assumptions implied in using the multinomial distribution, we used quasi-likelihood functions to compensate for the overdispersion of wasps within the olfactometer (Turlingset al. 2004). The model was fitted by maximum quasi-likelihood estimation in the software package R (version 1.9.1) and its adequacy was assessed through likelihood ratio statistics and examination of residuals. We tested treatment effects for naïve and experienced wasps individually.

RESULTS

Soil microorganisms modify aboveground volatile emissions of maize seedlings

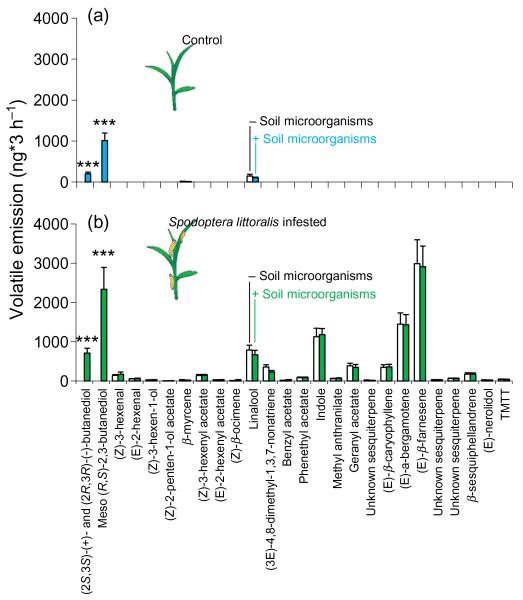

We compared VOCs emitted by plants growing in autoclaved soil supplemented with an extract of soil microorganisms to VOCs emitted by plants growing in autoclaved soil. GC-FID analyses of these blends showed that the addition of soil microorganisms caused the emission of large amounts of (2R,3R)-(−)- and (2S,3S)-(+)-BD and even more of meso (R,S)-2,3-BD in the aboveground part of maize seedlings, whereas the emission of two constitutively emitted terpenoids, β-myrcene and (S)-linalool, was not affected by the microorganisms (Table 1; Fig. 1). After infestation of seedlings with larvae of S. littoralis, the blend of seedlings exposed to microorganisms still included large amounts of 2,3-BD. The amounts of herbivore-induced plant-derived VOCs were not affected by the presence of the microorganisms (Fig. 1). Compared with healthy seedlings, herbivore-infested seedlings emitted significantly larger amounts of the optically active isomers of 2,3-BD (t-test; t22 = 3.32, P = 0.003).

Figure 1. Volatiles emitted by non-infested and Spodoptera-infested maize seedlings grown in autoclaved soil or autoclaved soil that was re-inoculated with extracted soil microorganisms.

Volatile compounds are ordered according to their retention time on a reverse-phase capillary column (HP-1MS). (2S,3S)-(+)- and (2R,3R)-(−)-butanediol (BD) were separated on a chiral column and identified by comparing the retention times with those of authentic synthetic standard. Stars denote compounds that are significantly different between plants with and without soil microorganisms (***P > 0.001).

Endophytic bacteria are the source of the 2,3-BD emission

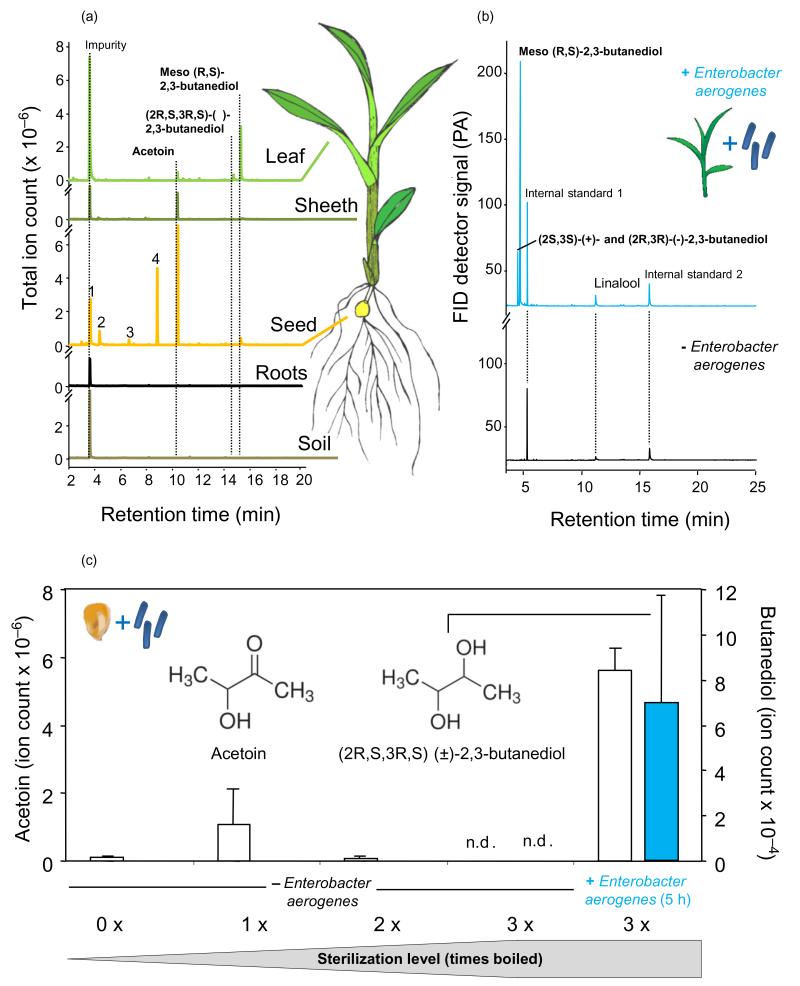

To localize 2,3-BD production, we measured VOC emissions of different parts of 2,3-BD-releasing seedlings as well as the surrounding soil. Qualitative SPME analyses showed that 2,3-BD is released from leaves, sheaths and seeds, but not from the roots and soil (Fig. 2a). Additionally, the seeds released other typically known bacteria-derived compounds, such as ethanol and 2-methyl-1-propanol, and contained considerable amounts of acetoin, the precursor of 2,3-BD, which was only detected in trace amounts in sheaths and leaves of the plants (Fig. 2a). From these results, we hypothesized that endopytic microorganisms that colonize the above- and belowground tissues of maize may be responsible for the release of 2,3-BD from the leaves. To test this hypothesis, we plated surface-sterilized germinated maize seeds on LB and PDA agar. We found ample bacterial growth on plates with seeds of 2,3-BD-releasing seedlings, but only sporadic growth on plates with seeds of seedlings without 2,3-BD (data not shown). We cultivated several isolates and identified one as E. aerogenes (synonymous with Klebsiella mobilis) based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence (identity >99%), API 20E metabolic tests for Enterobacteria (identity 97.7%), microscopy (morphology, motile cells) and MALDI/TOF-MS (identity 88%). E. aerogenes is known to produce 2,3-BD (Ji et al. 2011). Incubating surface-disinfected maize seeds into a suspension (~108 cfu mL−1) of the isolated E. aerogenes strain caused the emission of substantial amounts of (2R,3R)-(−)- and (2S,3S)-(+)-BD and very large amounts of meso (R,S)-2,3-BD in the aboveground parts of 10-day-old maize seedlings (Fig. 2b). Moreover, the isolated E. aerogenes strain also fermented tyndallized maize seeds (sterilization by three times boiling in autoclaved water) to 2,3-BD (Fig. 2c). Quantitative analyses indicated that maize seedlings inoculated with E. aerogenes released 2,3-BD in the same range as seedlings inoculated with the soil microorganism extract (Table 1). Interestingly, seedlings with added E. aerogenes emitted significant lower amounts of β-myrcene and linalool compared with control plants (t-test; β-myrcene: t22 = 2.37, P = 0.027; linalool: t22 = 2.30, P = 0.031).

Figure 2. Typical chromatographic traces of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) of 10-day-old maize seedlings.

(a) Volatile profiles detected in various parts of maize seedlings and soil that contained an extract of soil microorganisms. VOCs were adsorbed on a solid phase microextraction (SPME) fibre and analysed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) on a polar column. (b) Volatile profiles detected in the phyllosphere of undamaged maize seedlings with and without Enterobacter aerogenes bacteria (108 cfu mL−1). VOCs were adsorbed on Super-Q traps and analysed by GC-MS on an apolar column. (c) Relative amounts (mean of selective ion counts ± SE) of acetoin and 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BD) detected in the headspace of maize seeds. Seeds were sterilized by boiling and incubated in an overnight culture of E. aerogenes (108 cfu mL−1) or in autoclaved water only for 5 h. Single maize seeds were placed in vials sealed with a Teflon cap and VOCs were sampled 3 d after incubation by SPME and analysed by GC-MS similarly as described in the manuscript, but in selective ion mode with ion 88 for acetoin and ion 75 for 2,3-BD.

E. aerogenes bacteria colonize below- and aboveground parts of maize seedlings

To investigate which plant tissues are colonized by E. aerogenes, we selected a colony for Rifampicin (rif+) resistance, infected maize seeds and re-isolated rif+-resistant bacteria from different tissues after 10 d of plant growth. Identities of re-isolated cells were confirmed by comparing their 16S DNA restriction fragment length patterns and API 20E test results to the original strain. Rif+ E. aerogenes bacteria were not only present in seeds, but also in the aboveground sheath of 10-day-old maize seedlings (Table 2), demonstrating that the bacteria were able to colonize the aboveground parts after seed inoculation. No rif+-resistant bacteria were detected in non-infected maize seedlings.

Table 2. Re-isolation of bacteria from different parts of 10-day-old healthy maize seedlings.

| Strain for inoculation |

Surface treatment |

Re-isolatation on Rifampicin medium |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Sheath | Seeds | Root | ||

| None | Sterilized | − | − | − | − |

| Rif− | Sterilized | − | − | − | − |

| Rif+ | Sterilized | − | + | + | − |

| Rif− | Disinfected | − | − | + | − |

| Rif+ | Disinfected | − | + | + | + |

E. aerogenes and 2,3-BD increase pathogen resistance

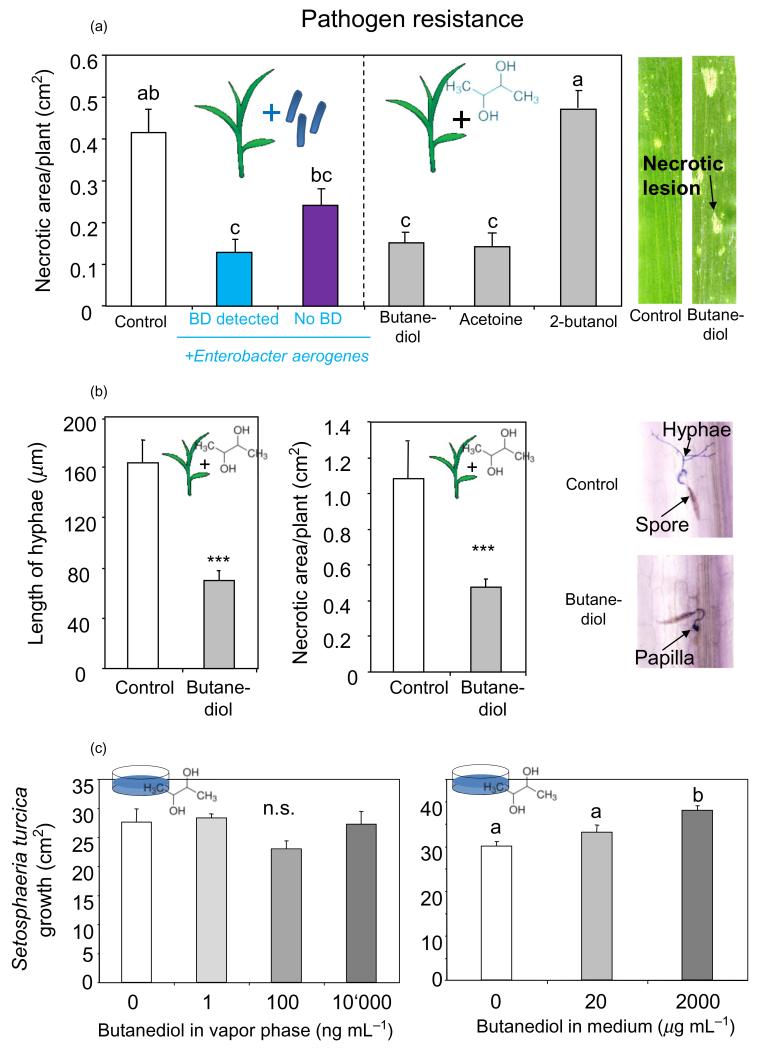

As 2,3-BD has been shown to enhance pathogen resistance in A. thaliana (Ryu et al. 2004), we hypothesized that the volatile may also have a positive effect in soil-grown maize plants infected with 2,3-BD-producing endophytes. An evaluation of the macroscopic disease symptoms of maize leaves inoculated with conidiospores of the Northern corn leaf blight S. turcica revealed that E. aerogenes and its volatile metabolites significantly enhanced the resistance of maize seedlings against the fungus (Fig. 3a, one-way anova: F5,58 = 16.64, P < 0.001). Maize seedlings with the 2,3-BD-producing E. aerogenes bacteria showed a threefold reduction in total necrotic and/or chlorotic leaf-area 3 d after infestation with conidiospores of S. turcica compared with control seedlings grown in autoclaved soil (Tukey’s test: P < 0.001). Treating seedlings with a synthetic isomeric mixture of 2,3-BD or acetoin also resulted in a strong reduction of the diseased leaf-area (P < 0.001 for both treatments), whereas seedlings treated with 2-butanol, a structural mimic of 2,3-BD, did not show any enhanced resistance against the fungus (P = 0.909). The enhanced resistance was less pronounced for the few seedlings that we inoculated with the bacteria, but that did not release 2,3-BD the day before treatment with the pathogen (P = 0.090). In the second experiment, we further characterized the nature of the induced resistance by staining the infected leaves with lactophenol trypan blue and examining the colonization by the pathogen microscopically. As shown in Fig. 3b, the mean length of the hyphae of the germinated conidiospores of S. turcica was significantly reduced in plants treated with synthetic 2,3-BD compared with control plants (one-way anova: F2,129 = 14.75, P < 0.001). This reduction in pathogen growth was often associated the formation of papillae-like cell wall apposition in the epidermal cell layer of the leaves (Fig. 3b; one-way anova: F2,28 = 3.45, P = 0.047). To investigate whether the enhanced resistance is plant mediated or caused by the volatiles directly, we tested direct antimicrobial activity of 2,3-BD by exposing Petri dishes containing spores of S. turcica to various concentrations of the volatile. No negative effect of 2,3-BD on S. turcica growth was observed (Fig. 3c). On the contrary, the growth of the pathogen was significantly enhanced in 2,3-BD-supplemented agarose (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Influence of 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BD) and Enterobacter aerogenes on pathogen resistance.

(a) Necrotic and chlorotic leaf area (±SE) 3 d after inoculation with conidiospores of the pathogen. Seedlings were grown in autoclaved soil (control), with E. aerogenes-infected plant with detectable (‘BD detected’) and no. 2,3-BD release (‘No BD’), or treated with bacterial volatiles (right). Different letters indicate significant differences between the treatments (one-way anova, P < 0.05). Right: Typical pictures of maize leaves 3 d after inoculation with spores of the pathogen. (b) Left: Average length (±SE) of hyphae of germinated spores on maize with or without 2,3-BD application. Right: Mean necrotic and/or chlorotic leaf area (±SE) of seedlings. Photographs show typical stained hyphae and papilla of Setosphaeria turcica growing on maize leaves. (c) Growth of S. turcica mycelium in vitro with different concentrations of 2,3-BD in the agarose medium (left) and the headspace (right). Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (one-way anova, P < 0.05).

E. aerogenes increases herbivore growth

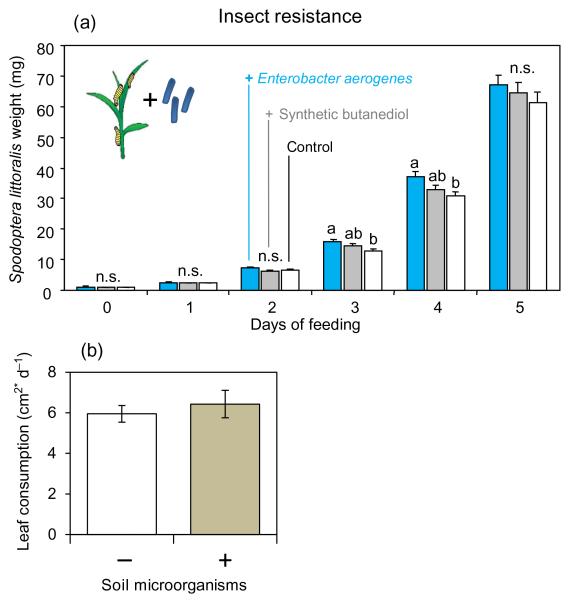

To test whether 2,3-BD affects herbivore resistance in maize, we monitored the growth of S. littoralis on treated maize seedlings. The larvae gained slightly more weight when feeding on maize seedlings colonized by E. aerogenes than on maize seedlings without the bacteria (Fig. 4a).This difference in larval weight was statistically significant after 3–4 d of continuous feeding (one-way anova: day 3, F2,203 = 4.42, P = 0.013; day 4, F2,193 = 4.05, P = 0.019). Exposing the plants to synthetic 2,3-BD led to an intermediate larval phenotype: Weight gain was not different from controls or E. aerogenes-infested plants (Fig. 4a). We furthermore tested whether inoculation with soil microorganisms affects short-term feeding activity of S. littoralis. The herbivore was found to consume similar amounts of leaf material over 24 h irrespective of the presence of soil microbes (t-test: t20 = −0.15, P = 0.882; Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Influence of 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BD) and Enterobacter aerogenes on insect resistance.

(a) Mean weight (±SE) of Spodoptera littoralis larvae feeding on maize seedlings grown in autoclaved soil only (control), with synthetic 2,3-BD, or with E. aerogenes bacteria. Different letters indicate significant differences of the larval weights (one-way anova, P < 0.05). (b) Average leaf consumption of S. littoralis larvae over 24 h on plants grown in autoclaved soil with and without supplementation of soil microbes.

E. aerogenes does not promote plant growth

2,3-BD has been shown to promote growth of A. thaliana seedlings in vitro (Ryu et al. 2003). To test whether colonization of the plant with the 2,3-BD-producing bacterium E. aerogenes improves plant growth, we measured plant height and biomass of maize seedlings 11 d after planting. No difference in plant height or final shoot biomass was detected (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Effect of Enterobacter aerogenes on plant growth.

(a) Average plant height of colonized and non-colonized seedlings. (b) Shoot biomass (dry weight) after 11 d of plant growth.

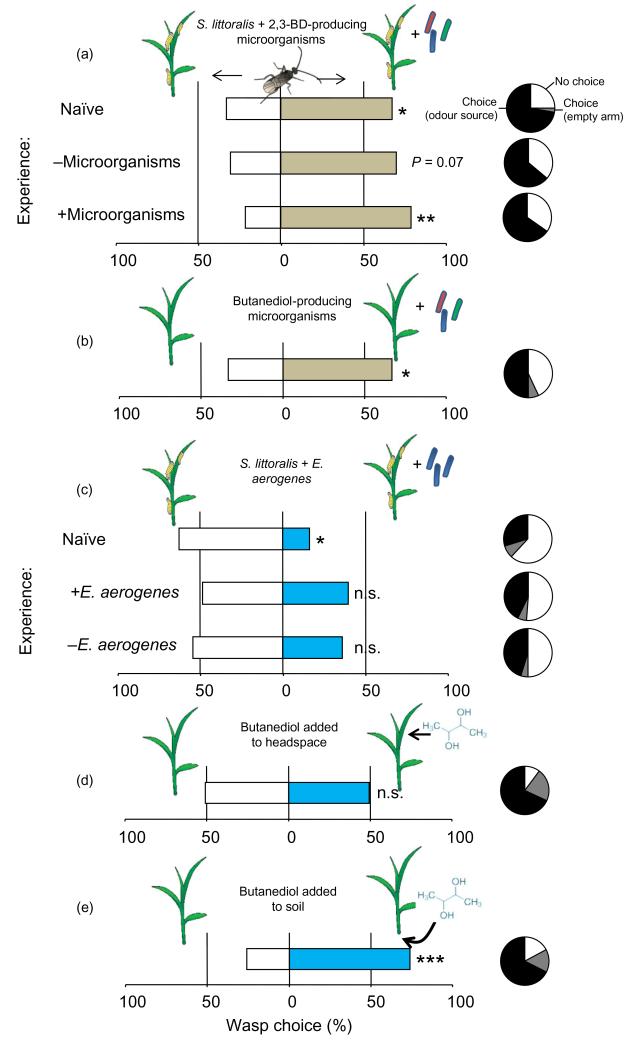

Microbial volatiles influence parasitoid behaviour

To investigate whether bacterial volatiles and 2,3-BD affect the attraction of higher tropic levels to herbivore-infested plants, we conducted a series of olfactometer bioassays. In the first experiment, C. marginiventris females with and without previous oviposition experience were given a choice between the volatile blends from S. littoralis-infested maize seedlings with or without added soil microorganisms (Fig. 6a). Naïve females significantly preferred the odour released by caterpillar-infested plants that were inoculated with 2,3-BD-producing microorganisms (GLM: naïve, F1,11 = 5.39, P = 0.04). This preference was even more pronounced after they were given experience with the same odour blend, and still showed a similar tendency after experiencing the odour of caterpillar-infested plants that were not inoculated (F1,11 = 11.74, P = 0.006; F1,11 = 4.01, P = 0.07). Moreover, naïve C. marginiventris females showed a significant preference for a blend released by healthy uninfested maize seedlings inoculated with 2,3-BD-producing soil microorganisms (GLM: F1,35 = 5.97, P = 0.02; Fig. 6b). From these results, we hypothesized that C. marginiventris should also be attracted to plants grown in autoclaved soil and colonized with 2,3-BD-producing E. aerogenes. However, contrary to this expectation, we found that S. littoralis-infested plants that harboured E. aerogenes and released 2,3-BD from their foliage were less attractive to naïve parasitoids (Fig. 6c). Experienced C. marginiventris wasps, on the contrary, did not show any preference any more. Similar to inoculation with soil microorganisms (Fig. 1), the release of herbivore-induced plant volatiles was not altered by E. aerogenes infestation (Supporting Information Fig. S1). To consolidate these conflicting results, we carried out additional olfactometer experiments with pure 2,3-BD. When added to the headspace of plants at physiologically relevant doses, C. marginiventris did not distinguish between 2,3-BD-releasing and 2,3-BD-free plants (Fig. 6d). On the contrary, when 2,3-BD was added to the soil, the parasitoids preferred 2,3-BD-treated plants (Fig. 6e). From these results, we conclude that 2,3-BD has an indirect, plant-mediated positive effect on plant attractiveness, but that independent of 2,3-BD, other behaviourally active volatiles released in small amounts are likely to be altered by the presence of E. aerogenes.

Figure 6. Effect of microbial volatiles on parasitoid attraction.

Percentages of female Cotesia marginiventris wasps choosing one of two odour sources in a six-arm olfactometer are shown. Circles denote the proportion of wasps that did not make a choice (white) or those that entered an empty arm of the olfactometer (grey). The following choice tests were offered: (a) infested plants with and without supplementation of soil microorganisms; (b) healthy plants with and without soil microorganisms; (c) infested plants with and without Enterobacter aerogenes colonization; (d) healthy plants with and without synthetic 2,3-butanediol (2,3-BD) in the headspace; (e) healthy plants with and without synthetic 2,3-BD added to the soil. Stars denote significant differences between odour sources (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Over the past two decades, aboveground VOCs emitted by green parts of plants have been studied in great detail (Kant et al. 2009). In the current study, we demonstrate that leaf volatile bouquets of maize seedlings also contain VOCs of microbial origin, which affect plant resistance and interactions with antagonists and higher tropic levels. The effects of bacterial volatiles on plant growth and pathogen resistance have been described in detail (Ryu et al. 2004; Kai et al. 2009; Cortes-Barco et al. 2010). However, most experiments involving microbial VOCs were conducted in Petri dishes in which plant seedlings were co-cultured with volatile-producing bacteria. The current study shows that soil-borne microorganisms, including the isolated bacterium E. aerogenes, colonize soil-grown maize seedlings and produce 2,3-BD, which is subsequently released in high quantities from the foliage of the plant. Manipulating the microbial community by autoclaving the soil and re-inoculating it with soil-borne microorganisms was sufficient to achieve the release of 2,3-BD from maize plants. For approximately 20% of all sampled seedlings to which we had added the bacteria, we never detected 2,3-BD during the 14 d of sampling (data not shown). This could be explained by the fact that 2,3-BD fermentation seems to be affected by N-acyl-L-serine lactone-dependent quorum sensing (Van Houdt et al. 2006). Although we incubated seeds in a relatively high concentration of E. aerogenes (approximately 108 cfu mL−1), in some cases, this inoculate might not have been adequate to build up a large enough bacterial population to induce 2,3-BD fermentation. Furthermore, low oxygen levels promote 2,3-BD production, and variation in the abiotic environment of the different colonized maize tissues may have contributed to the observed variation. On the contrary, we rarely but occasionally detected 2,3-BD in control seedlings, which could be due to bacteria that were already present in the seeds or the re-colonization of the sterilized soil by 2,3-BD-producing bacteria from the environment.

2,3-BD has been documented to improve plant pathogen resistance in A. thaliana, Nicotiana tabacum and N. benthamiana by activating the plant’s immune system (Ryu et al. 2004; Han et al. 2006; Cortes-Barco et al. 2010). Our results show that 2,3-BD also improves resistance of maize against S. turcica: Seedlings treated with 2,3-BD-producing E. aerogenes as well as synthetic 2,3-BD showed reduced fungal infection symptoms. One possible explanation for this phenomenon would be an antimicrobial effect of 2,3-BD. Microbial VOCs have indeed been reported to directly kill or inhibit the growth of a wide variety of pathogens (Strobel 2006; Kai et al. 2007). However, in our experiments, synthetic 2,3-BD had no direct antimicrobial effect on S. turcica (Fig. 3c), which suggests a plant-mediated effect similar to what has been proposed for other plant models (Cortes-Barco et al. 2010). Further experiments will be necessary to pinpoint the mode of action of 2,3-BD. Given the conserved mode of action, model plants for which more extensive molecular tools have been developed and with well-characterized pathogen recognition systems may be best suited for this task. In this context, it is important to point out that 2,3-BD may not be the only mechanism by which E. aerogenes triggers pathogen resistance (Partida-Martínez & Heil 2011). Assessing the relative contribution of 2,3-BD relative to other induction mechanisms would require the creation of transgenic E. aerogenes strains that are unable to produce the volatile, an approach that has been taken in other systems before (Ryu et al. 2004).

Compared with pathogen resistance, virtually nothing is known about the impact of volatiles from soil-borne bacteria on herbivorous insects. Spodoptera caterpillars have been found to be attracted to VOCs (Carroll et al. 2008; von Mérey et al. 2013), despite the fact that in some cases they can be directly toxic (Vaughan et al. 2013). Furthermore, ISR, as it is triggered by bacterial volatiles (Cortes-Barco et al. 2010), may lead to indirect effects of bacterial volatiles on herbivores (Van Oosten et al. 2008).Volatiles from endophytic fungi have been discussed as insect resistance factors, even though little experimental evidence exists so far (Yue et al. 2001). In general, fungal volatiles can have strong effects on herbivore attraction (Davis et al. 2013). In our experiments, we did not find evidence that 2,3-BD enhances plant resistance against herbivores as leaf consumption rates by S. littoralis caterpillars were unaffected by the presence of soil microorganisms. By contrast, S. littoralis caterpillars displayed increased growth on E. aerogenes-colonized maize seedlings, whereas treatment of the plants with synthetic 2,3-BD caused marginally increased caterpillar performance, which was not statistically significant in comparison to the control treatment; therefore, the actual contribution of 2,3-BD to the E. aerogenes-induced susceptibility remains to be determined. The fact that S. littoralis induced the release of same amounts of plant-derived VOCs independently of the presence of soil microbes indicates that this indirect defensive response was not compromised by the microbes. It is also possible that E. aerogenes alters the nutritional quality of the plant. Fungal endophytes for instance are known to increase leaf nitrogen levels (Omacini et al. 2001), and many bacterial VOCs have plant growth-promoting effects in vitro (Bailly & Weisskopf 2012). Although E. aerogenes did not increase the growth of maize seedlings in our experiments, it is still possible that subtle alterations in the plant’s primary metabolism may have contributed to the observed increase in S. littoralis growth.

Bacterial volatiles may not only affect plants and herbivores, but may also influence foraging behaviour at higher trophic levels (Davis et al. 2013). Volatile collections showed that S. littoralis attack increases the emission of 2,3-BD, and the volatile may therefore be used as a host-location signal by parasitoids. On the contrary, as the emission of bacterial volatiles is likely to be unpredictable in nature, parasitoids may have evolved to ignore the microbial noise that otherwise may distract them from foraging for suitable hosts. Surprisingly, our olfactometer results favour neither of the above hypotheses: Whereas C. marginiventris preferred plants growing with soil borne microorganisms, plants that were infested with E. aerogenes were less attractive. This demonstrates that soil microbes and bacterial endophytes indeed influence the attractiveness of plants to parasitoids, but the direction of the effect depends on the microbial identity and community composition. The soil microbe extract likely contained a variety of bacteria and fungi, which may have contributed to the observed patterns. Neither the repellent nor the attractive effect measured in these experiments can be attributed to 2,3-BD emission only, as the volatile failed to have an effect on C. marginiventris when added to the plant headspace in physiologically relevant concentrations. Therefore, other volatile compounds that are produced by the bacteria are likely to affect the wasp’s behaviour. As we did not find any other bacterial VOCs in the headspace collections, highly volatile substances that are not detected with conventional volatile trapping like ethylene are possible candidates in this context. Endopythic bacteria are well known to modulate plant ethylene levels (Hardoim et al. 2008), which may directly impact parasitoid attraction. We also have indications that certain key attractants are released in undetectable amounts (D’Alessandro et al. 2009) that can be enhanced by plant treatments (Sobhy et al. 2012). Curiously, when 2,3-BD was added to the rhizosphere, maize seedlings became more attractive to C. marginiventris. This could either be because of a dose–response phenomenon by which only low concentrations of 2,3-BD are attractive, or because of an influence of 2,3-BD on the release of key attractants. It is also possible that 2,3-BD affects the microbial community itself. Indeed, 2,3-BD can be used as a source of energy by microbes (Ji et al. 2011), and watering the soil with this compound may have accelerated microbial colonization, which may then have rendered seedlings more attractive to the parasitoids. From the current set of experiments, it becomes clear that the effect of 2,3-BD as well as bacterial endophytes is strongly context dependent and possibly indirect. Further experiments will be required to clarify whether other bacterial volatiles affect the behaviour of parasitoids and if 2,3-BD may act as a bacterial signal.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that volatiles produced by soil-borne microbial endopyhtes affect consumers and higher trophic levels via plant-mediated processes in vivo. Considering the ubiquitous presence of endophytic bacteria in most plants (Hallmann et al. 1997), it seems pertinent that future studies on plant–insect and plant–pathogen interactions should take into account that microbial endophytes and their volatiles can have crucial effects on the outcome of the interactions among members of entire food webs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Matthias Held and colleagues of the FARCE Laboratory (University of Neuchâtel) for their valuable comments on statistical and experimental aspects of this work. We are grateful to Dr. Brigitte Mauch-Mani of the Laboratory of Cell and Molecular Biology (University of Neuchâtel) for providing laboratory space and equipment. We also thank Dr. Michael Rostás (Lincoln University, Christchurch) for S. turcica cultures and Syngenta (Stein, Switzerland) for the weekly supply of S. littoralis eggs and artificial diet. Neil Villard helped with the MALDI-TOF identification. Three anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments that contribute to improving the manuscript. This project was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant No. 31-058865.99) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research ‘Plant Survival’. M.E. is currently supported by a Marie Curie Intra European Fellowship (Grant No. 273107). JT’s research is currently supported by a grant from the European Research Council (ERC; no. 309944; ‘PRIME-A-PLANT’) and a Research Leadership Award from the Leverhulme Trust (no. RL-2012-042).

REFERENCES

- Bailly A, Weisskopf L. The modulating effect of bacterial volatiles on plant growth current knowledge and future challenges. Plant Signaling and Behavior. 2012;7:79–85. doi: 10.4161/psb.7.1.18418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll MJ, Schmelz EA, Teal PEA. The attraction of Spodoptera frugiperda neonates to cowpea seedlings is mediated by volatiles induced by conspecific herbivory and the elicitor inceptin. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2008;34:291–300. doi: 10.1007/s10886-007-9414-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Barco AM, Goodwin PH, Hsiang T. Comparison of induced resistance activated by benzothiadiazole, (2R,3R)-butanediol and an isoparaffin mixture against anthracnose of Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Pathology. 2010;59:643–653. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro M, Turlings TCJ. In situ modification of herbivore-induced plant odors: a novel approach to study the attractiveness of volatile organic compounds to parasitic wasps. Chemical Senses. 2005;30:739–753. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bji066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro M, Held M, Triponez Y, Turlings T. The role of indole and other shikimic acid derived maize volatiles in the attraction of two parasitic wasps. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2006;32:2733–2748. doi: 10.1007/s10886-006-9196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro M, Brunner V, von Merey G, Turlings TCJ. Strong attraction of the parasitoid Cotesia marginiventris towards minor volatile compounds of maize. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2009;35:999–1008. doi: 10.1007/s10886-009-9692-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam NM. How plants cope with biotic interactions. Plant Biology. 2009;11:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TS, Crippen TL, Hofstetter RW, Tomberlin JK. Microbial volatile emissions as insect semiochemicals. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2013;39:840–859. doi: 10.1007/s10886-013-0306-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann J, QuadtHallmann A, Mahaffee WF, Kloepper JW. Bacterial endophytes in agricultural crops. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 1997;43:895–914. [Google Scholar]

- Han SH, Lee SJ, Moon JH, Park KH, Yang KY, Cho BH, Kim YC. GacS-dependent production of 2R, 3R-butanediol by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6 is a major determinant for eliciting systemic resistance against Erwinia carotovora but not against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci in tobacco. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2006;19:924–930. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardoim PR, van Overbeek LS, Elsas JD. Properties of bacterial endophytes and their proposed role in plant growth. Trends in Microbiology. 2008;16:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GA, Jander G. Plant immunity to insect herbivores. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2008;59:41–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffaker A, Pearce G, Veyrat N, Erb M, Turlings TCJ, Sartor R, Schmelz EA. Plant elicitor peptides are conserved signals regulating direct and indirect antiherbivore defense. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:5707–5712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214668110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X-J, Huang H, Ouyang P-K. Microbial 2,3-butanediol production: a state-of-the-art review. Biotechnology Advances. 2011;29:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai M, Effmert U, Berg G, Piechulla B. Volatiles of bacterial antagonists inhibit mycelial growth of the plant pathogen Rhizoctonia solani. Archives of Microbiology. 2007;187:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s00203-006-0199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai M, Haustein M, Molina F, Petri A, Scholz B, Piechulla B. Bacterial volatiles and their action potential. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2009;81:1001–1012. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1760-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kant MR, Bleeker PM, Van Wijk M, Schuurink RC, Haring MA. Plant volatiles in defence. Plant Innate Immunity. 2009;51:613–666. [Google Scholar]

- Koch E, Slusarenko A. Arabidopsis is susceptible to infection by a downy mildew fungus. The Plant Cell. 1990;2:437–445. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.5.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy PD, Sabri A, Heuskin S, Thonart P, Lognay G, Verheggen FJ, Haubruge E. Microorganisms from aphid honeydew attract and enhance the efficacy of natural enemies. Nat Commun. 2011;2:348. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti G, Erb M, Boccard J, Glauser G, Doyen GR, Villard N, Wolfender J-L. Metabolomics reveals herbivore-induced metabolites of resistance and susceptibility in maize leaves and roots. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2012;36:621–639. doi: 10.1111/pce.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyzer G, Teske A, Wirsen CO, Jannasch HW. Phylogenetic relationships of Thiomicrospira species and their identification in deep-sea hydrothermal vent samples by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of 16S rDNA fragments. Archives of Microbiology. 1995;164:165–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02529967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal AL, Ton J. Systemic defense priming by Pseudomonas putida KT2440 in maize depends on benzoxazinoid exudation from the roots. Plant Signaling and Behavior. 2013;8:120–124. doi: 10.4161/psb.22655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen DR, Yoon S-H, Yuan CJ, Prather KLJ. Metabolic engineering of acetoin and meso-2, 3-butanediol biosynthesis in E. coli. Biotechnology Journal. 2010;5:274–284. doi: 10.1002/biot.200900279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omacini M, Chaneton EJ, Ghersa CM, Muller CB. Symbiotic fungal endophytes control insect host-parasite interaction webs. Nature. 2001;409:78–81. doi: 10.1038/35051070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partida-Martínez LP, Heil M. The microbe-free plant: fact or artifact? Frontiers in Plant Science. 2011;2:100. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda A, Zheng S-J, van Loon JJA, Pieterse CMJ, Dicke M. Helping plants to deal with insects: the role of beneficial soil-borne microbes. Trends in Plant Science. 2010;15:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmann S, Köllner TG, Degenhardt J, Hiltpold I, Toepfer S, Kuhlmann U, Turlings TCJ. Recruitment of entomopathogenic nematodes by insect-damaged maize roots. Nature. 2005;434:732–737. doi: 10.1038/nature03451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robacker DC, Flath RA. Attractants from Staphylococcus aureus cultures for Mexican fruit fly, Anastrepha ludens. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 1995;21:1861–1874. doi: 10.1007/BF02033682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostas M, Ton J, Mauch-Mani B, Turlings TCJ. Fungal infection reduces herbivore-induced plant volatiles of maize but does not affect naive parasitoids. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2006;32:1897–1909. doi: 10.1007/s10886-006-9147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudrappa T, Biedrzycki ML, Kunjeti SG, Donofrio NM, Czymmek KJ, Paul WP, Bais HP. The rhizobacterial elicitor acetoin induces systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Communicative and Integrative Biology. 2010;3:130–138. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.2.10584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu CM, Farag MA, Hu CH, Reddy MS, Kloepper JW, Pare PW. Bacterial volatiles induce systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2004;134:1017–1026. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu C-M, Farag MA, Hu C-H, Reddy MS, Wei H-X, Paré PW, Kloepper JW. Bacterial volatiles promote growth in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:4927–4932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730845100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobhy I, Erb M, Sarhan A, El-Husseini M, Mandour N, Turlings TJ. Less is more: treatment with bth and laminarin reduces herbivore-induced volatile emissions in maize but increases parasitoid attraction. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2012;38:348–360. doi: 10.1007/s10886-012-0098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel G. Harnessing endophytes for industrial microbiology. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2006;9:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma BPHJ, Nürnberger T, Joosten MHAJ. Of PAMPs and effectors: the blurred PTI-ETI Dichotomy. The Plant Cell Online. 2011;23:4–15. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton J, D’Alessandro M, Jourdie V, Jakab G, Karlen D, Held M, Turlings TCJ. Priming by airborne signals boosts direct and indirect resistance in maize. The Plant Journal. 2007;49:16–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turlings TCJ, Davison AC, Tamo C. A six-arm olfactometer permitting simultaneous observation of insect attraction and odour trapping. Physiological Entomology. 2004;29:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Van Houdt R, Moons P, Buj MH, Michiels CW. N-acyl-L-homoserine lactone quorum sensing controls butanediol fermentation in Serratia plymuthica RVH1 and Serratia marcescens MG1. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188:4570–4572. doi: 10.1128/JB.00144-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oosten VR, Bodenhausen N, Reymond P, Van Pelt JA, Van Loon LC, Dicke M, Pieterse CMJ. Differential effectiveness of microbially induced resistance against herbivorous insects in Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2008;21:919–930. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-7-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan MM, Wang Q, Webster FX, Kiemle D, Hong YJ, Tantillo DJ, Tholl D. Formation of the unusual semivolatile diterpene rhizathalene by the Arabidopsis class I terpene synthase tps08 in the root stele is involved in defense against belowground herbivory. The Plant Cell Online. 2013;25:1108–1125. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mérey GE, Veyrat N, D’Alessandro M, Turlings T. Herbivore-induced maize leaf volatiles affect attraction and feeding behaviour of Spodoptera littoralis caterpillars. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2013;4:209. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Q, Wang C, Gianfagna TJ, Meyer WA. Volatile compounds of endophyte-free and infected tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.) Phytochemistry. 2001;58:935–941. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler D, Mariotti A, Pflüger V, Saad M, Vogel G, Tonolla M, Perret X. In situ identification of plant-invasive bacteria with MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.