Highlights

-

•

The Tet-On 3G system is useful for conditional gene overexpression studies in DT40.

-

•

The Tet-On-I-SceI effectively induces DSB formation in vertebrate cells.

-

•

BRC4 overexpression induces chromosomal breaks and G2-arrest.

-

•

BRC4 cytotoxicity is mediated by endogenous BRCA2, but independent of NHEJ.

-

•

BRC4 inhibits cancer cell proliferation and exacerbates the effects of chemotherapy.

Keywords: Homologous recombination, RAD51, BRC4, BRCA2, Tet-On system, DT40 cells

Abstract

Transient induction or suppression of target genes is useful to study the function of toxic or essential genes in cells. Here we apply a Tet-On 3G system to DT40 lymphoma B cell lines, validating it for three different genes. Using this tool, we then show that overexpression of the chicken BRC4 repeat of the tumor suppressor BRCA2 impairs cell proliferation and induces chromosomal breaks. Mechanistically, high levels of BRC4 suppress double strand break-induced homologous recombination, inhibit the formation of RAD51 recombination repair foci, reduce cellular resistance to DNA damaging agents and induce a G2 damage checkpoint-mediated cell-cycle arrest. The above phenotypes are mediated by BRC4 capability to bind and inhibit RAD51. The toxicity associated with BRC4 overexpression is exacerbated by chemotherapeutic agents and reversed by RAD51 overexpression, but it is neither aggravated nor suppressed by a deficit in the non-homologous end-joining pathway of double strand break repair. We further find that the endogenous BRCA2 mediates the cytotoxicity associated with BRC4 induction, thus underscoring the possibility that BRC4 or other domains of BRCA2 cooperate with ectopic BRC4 in regulating repair activities or mitotic cell division. In all, the results demonstrate the utility of the Tet-On 3G system in DT40 research and underpin a model in which BRC4 role on cell proliferation and chromosome repair arises primarily from its suppressive role on RAD51 functions.

1. Introduction

Homologous recombination (HR) is essential for genome integrity as it protects against DNA lesions derived from both endogenous and exogenous sources. The recombination mediator RAD51, the homologue of yeast Rad51 and bacterial RecA, plays central roles in HR in all organisms studied to date. Its coating of single strand (ss) DNA, exposed at stalled replication forks or formed during resection of double strand breaks (DSBs), leads to the formation of a nucleoprotein filament that can invade a homologous duplex to promote DNA repair [1]. HR and RAD51 activities need to be tightly regulated in the cell: low levels of RAD51 cause chromosome breakage and reduced cell proliferation, but increased levels of RAD51 also lead to genomic rearrangements by its ability to induce aberrant or ectopic recombination with repeats or non-homologous chromosomes [2], [3].

The BRCA2 tumor suppressor, which is associated with a substantial fraction of familial breast cancers, participates in DNA recombination and repair processes, and is well known for its recombination mediator function [4]. Critical for the function of BRCA2 is its interaction with RAD51 [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], which is largely mediated by the eight internal BRC repeats contained in BRCA2 [9], [10]. Of these BRC repeats, BRC3 and BRC4 have been thoroughly characterized biochemically. They bind to RAD51 [5], [7], [8], [10], [11], and whereas low concentrations of BRC4 and BRC3 enhance RAD51 binding to ssDNA and stimulate RAD51-mediated strand exchange [10], [12], [13], high concentrations of BRC4 and BRC3 disrupt RAD51 filament formation [6], [11], [12]. Consistent with these in vitro biochemical observations, both BRCA2 knockout cells and BRC4 overexpressing cells are defective in RAD51 foci formation and HR repair [7], [8], [14], [15].

In this study, we examined the function of BRC4 on HR by conditionally overexpressing BRC4 in chicken DT40 cells using a tetracycline-inducible Tet-On 3G system. The Tet-On system is especially useful when applied to cell lines in which the transfection efficiency of expression plasmids is low, as is the case of nerve and lymphocyte cell lines. While the bursal DT40 cell line has multiple valuable features for research [16], the transfection efficiency of expression plasmids is usually very low. Here, we employed a recently developed Tet-On 3G system and applied it to p53, presupposed to induce apoptosis-mediated cell cycle arrest, and to BRC4 and I-SceI to study their effect on recombinational repair. In all cases, we achieved high enough induction to cause cell death in the presence of doxycycline (Dox) and detected no leaky expression in its absence, thus demonstrating the general utility of the Tet-On 3G system in DT40 research for studies of conditional or transient induction of genes.

Using these new tools, here we report that conditional induction of the BRC4 repeat of BRCA2 impairs cell proliferation of chicken DT40 cells by inducing a G2 damage checkpoint-mediated arrest and an accumulation of chromosome gaps and breaks. BRC4 induction suppresses HR and reduces cellular resistance to DNA damaging agents. These effects are mediated by BRC4 binding to RAD51 and counteracted by RAD51 overexpression. Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) was not responsible for the phenotypes associated with BRC4 induction, nor was required to sustain viability in these cells, indicating that NHEJ is actively suppressed in G2 even when the HR pathway is defective. Moreover, we find that endogenous BRCA2 is required for BRC4 cytotoxicity, suggesting a possible crosstalk between BRC4 and other BRCA2 domains in regulating DNA repair or mitotic cell division.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture techniques and cell viability/drug sensitivity assays

Cells were cultured at 39.5 °C in D-MEM/F-12 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2% chicken serum (Sigma), Penicillin/Streptomycin mix, and 10 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco) in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml Dox. The cell lines used in this study are shown in Table 1. To plot growth curves, each cell line was cultured in three different wells of 24 well-plates and passaged every 12 h. Cell number was determined by flow cytometry using plastic microbeads (07313-5; Polysciences). Cell solutions were mixed with the plastic microbead suspension at a ratio of 10:1, and viable cells determined by forward scatter and side scatter were counted when a given number of microbeads were detected by flow cytometry. mCherry positive cells were detected by FL2-H as shown in Fig. 2A.

Table 1.

Cell lines used in this study.

| Genotype | Selective marker | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| WT CL18 | [16] | |

| WT + DR-GFP + I-SceI (Tet-On) | Puro/Neo | This study |

| WT + DR-GFP + I-SceI and BRC4 (Tet-On) | Puro/Neo/Bsr | This study |

| WT + BRC4 (Tet-On) | Neo | This study |

| WT + BRC4 A1504S (Tet-On) | Bsr | This study |

| WT + BRC4 (Tet-On) + hsRAD51 | Neo/Bsr | This study |

| BRCA2+/− | Bsr/Puro | [15] |

| BRCA2+/− + BRC4 (Tet-On) | Bsr/Puro/Neo | This study |

| XRCC4/− + DR-GFP + I-SceI (Tet-On) | Neo/Puro/His | This study |

| XRCC4/− + BRC4 (Tet-On) | Puro/Neo/His | This study |

| XRCC3−/− | Bsr/His | [17] |

| RAD51−/− + hsRAD51 | Puro/Bsr/Neo/Hyg | [18] |

Fig. 2.

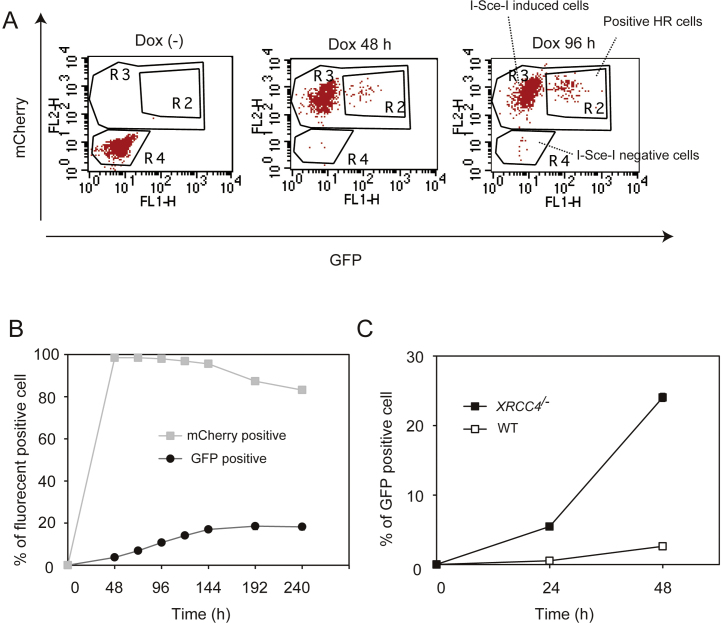

Measurement of homologous recombination-dependent DSB repair. (A) WT + I-SceI (Tet-On) cells containing the DR-GFP construct were incubated with Dox. mCherry and GFP expressing fractions were measured at the indicated time points. The vertical axis represents the expression level of mCherry and horizontal axis represents the expression level of GFP. R2, R3 and R4 indicate cells that underwent recombination, I-SceI -induced cells and I-SceI negative cells, respectively. (B) The percentage of the cell population expressing mCherry and GFP are plotted.

2.2. Plasmid construction and transfection

Tet-On® 3G Inducible Expression System (with mCherry) containing pTRE3G-mCherry and pCMV-Tet3G vectors was purchased from Clontech. Chicken BRC4 cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription PCR using 5′-GGAACTTATCTGACTGGTTTCTGTACTGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-ATCTGCATCACAATGAGCAGTACTGTCC-3′ (antisense) primers. The NdeI site and NLS to its N-terminal end and a FLAG tag and BamHI site to its C-terminal end were added by PCR using 5′-CATATGCCAAAGAAGAAACGCAAGGTGGGAACTTATCTGACTGGTTTCTGTACTGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGATCCTTACTTGTCGTCATCGTCTTTGTAGTCTGCATCACAATGAGCAGTACTGTCC-3′ (antisense) primers. BRC4 was then cloned into the pTRE3G-mCherry vector. The amino acid sequence of BRC4 used in this study except for NLS and FLAG is GTYLTGFCTASGKKITIADGFLAKAEEFFSENNVDLGKDDNDCFEDCLRKCNKSYVKDRDLCMDSTAHCDAD (amino acid residues 1495–1566 of chicken BRCA2). Similarly, p53 cDNA was amplified using 5′-GAATTCCGAACGGCGGCGGCGGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCTGAAGGGAAAGGGGGCGTGGTAAAGG-3′ (antisense) primers, then an NdeI site to its N-terminal and a FLAG tag and BamHI site to its C-terminal were added by PCR using 5′-CATATGGCGGAGGAGATGGAACCATTGCTGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGATCCTTACTTGTCGTCATCGTCTTTGTAGTCCATGTCCGAGCCTTTTTGCAGCAGTTTCTTCC-3′ (antisense) primers. After cloning p53 into the pTRE3G-mCherry vector, the premature stop codon of p53 was corrected by site directed mutagenesis using 5′-CTGTTGGGGCGGCGCTGCTTCGAGGTGCGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCGCACCTCGAAGCAGCGCCGCCCCAACAG-3′ (antisense) primers. I-SceI was tagged with an NdeI site N-terminally and a FLAG and BamHI site C-terminally by PCR using 5′-CATATGGGATCAAGATCGCCAAAAAAGAAGAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGATCCTTACTTGTCGTCATCGTCTTTGTAGTCCATTTTCAGGAAAGTTTCGGAGGAGATAGTG-3′ (antisense) primers, and cloned into the pTRE3G-mCherry vector. These expression vectors were transfected to DT40 cells with pCMV-Tet3G vectors in the ratio (6:1), and cells expressing the target genes in the presence of Dox were selected. BRC4-A1504S cells were obtained by transfecting an identical BRC4 construct containing the A1504S mutation engineered by QuickChange Site Directed Mutagenesis using 5′-CTGACTGGTTTCTGTACTTCTAGTGGCAAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTTGCCACTAGAAGTACAGAAACCAGTCAG-3′ (antisense) primers. hsRAD51 overexpression clones were obtained as previously described [17]. The XRCC4 knockout constructs are previously reported [19]. Briefly, the 110–165 amino acid fragment of XRCC4 (full length 283 amino acids) was replaced by drug resistance marker genes.

2.3. DNA fragmentation assay

DNA fragmentation assay was performed as previously described [19]. Cells were lysed, and genomic DNA was extracted using Easy DNA kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA was quantified and 4 μg was electrophoresed in a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml). DNA ladders were visualized under an ultraviolet light and photographed.

2.4. Western blotting

Western blotting were performed as previously described [19] using antibodies against MCM7 or RAD51 (Santa Cruz), α-tubulin or FLAG-M2 (Sigma), pCHK1 S345 (Cell Signaling), γ-H2AX (Millipore) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-rabbit, or anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Cell Signaling). Proteins were visualized using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Scientific).

2.5. Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described [18]. Cells were cultured in the presence of BrdU for 15 min, fixed in 70% ethanol, incubated with anti-BrdU antibody (BD Biosciences), and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Sigma) and propidium iodide. For PI single staining analysis, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol and stained with propidium iodide.

2.6. mRNA isolation, reverse transcription and qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and converted to cDNA with Superscript III (Invitrogen). The cDNA was amplified with GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega) and LightCycler® 480 system (Roche). Normalization of the amount of cDNA was done with β-actin. The primers used to amplify BRC4 were 5′-CAATTGCTGATGGATTTTTGGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTCACGGTCTTTAACATAGC-3′ (antisense), and the primers used to amplify β-actin were 5′-CGTGCTGTGTTCCCATCTATCGTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TACCTCTTTTGCTCTGGGCTTCATC-3′ (antisense).

2.7. Immunofluorescent visualization of subnuclear RAD51 foci formation

Immunocytochemical analysis was performed as described in [17]. Briefly, DT40 cells (105 cells) were treated with MMC (500 ng/ml) for 1 h, washed with warm medium 3 times and cultured for an additional 1 h at 39.5 °C. Cells were washed with PBS and spun onto Nunc® Lab-Tek® II Chamber Slide system by centrifugal attachment. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, and permeabilized with 0.5% triton/PBS. After blocking with 3% BSA, fixed cells were treated with RAD51 antibodies (1:500; Santa Cruz) followed by Alexa488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:100; Molecular Probes). In Fig. 8D and E, in order to detect RAD51 foci even in the presence of overexpressed RAD51, cells were treated with MMC for 6 h and pre-extracted by 0.1% triton/PBS for 3 min prior to fixation. At least 100 morphologically intact cells were examined. Cells with more than four brightly fluorescing foci were scored as positive.

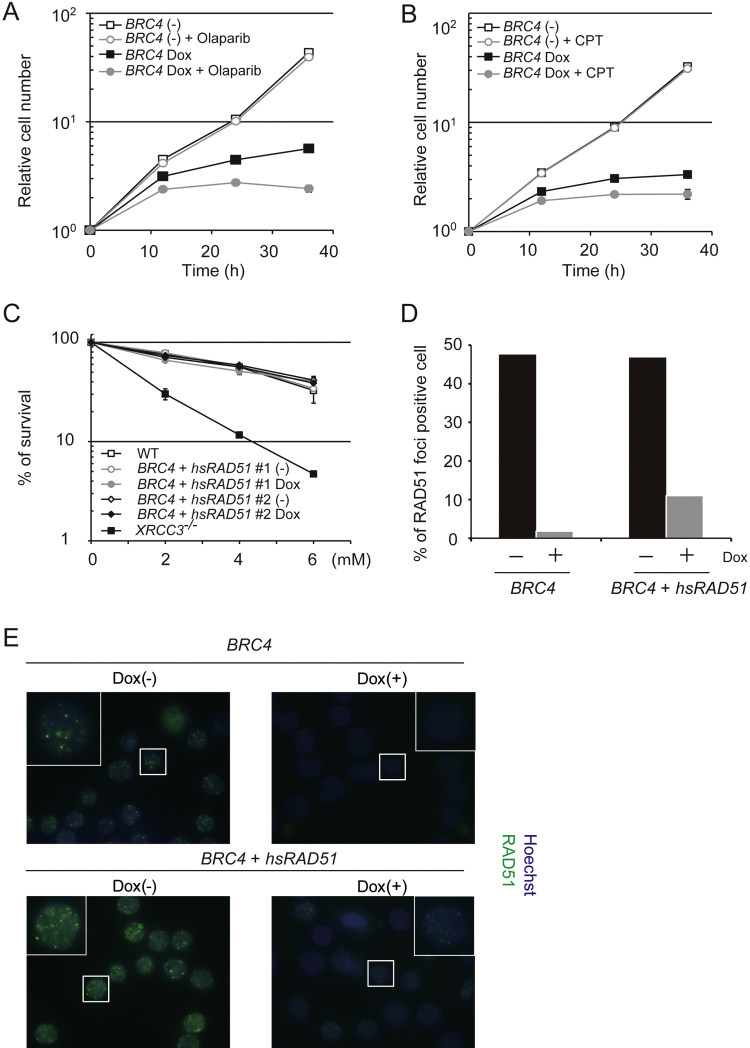

Fig. 8.

Rad51 overexpression rescues BRC4-induced homologous recombination repair defects. (A) and (B) growth curves. BRC4 cells (1 × 105) were inoculated in 1 ml of medium and passaged every 12 h. Dox and olaparib (A) or CPT (B) were added at time 0. (C) Sensitivity of indicated cells to olaparib. Dox was added 24 h before the experiment. Cell survival percentage is displayed as the ratio of the number of surviving cells following olaparib treatment relative to the untreated control. Each line and error bar represents the mean value and SD from three independent experiments, respectively. (D) and (E) Rad51 focus formation. BRC4 cells and BRC4 + hsRAD51 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Dox for 20 h. Then cells were exposed to 500 ng/ml of MMC for 6 h. Cytoplasmic RAD51 was washed out by pre-triton treatment prior to fixation to reduce the background. At least 100 cells were scored for each preparation. Identical trends were observed in independently conducted experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of the Tet-On 3G system in DT40 cells

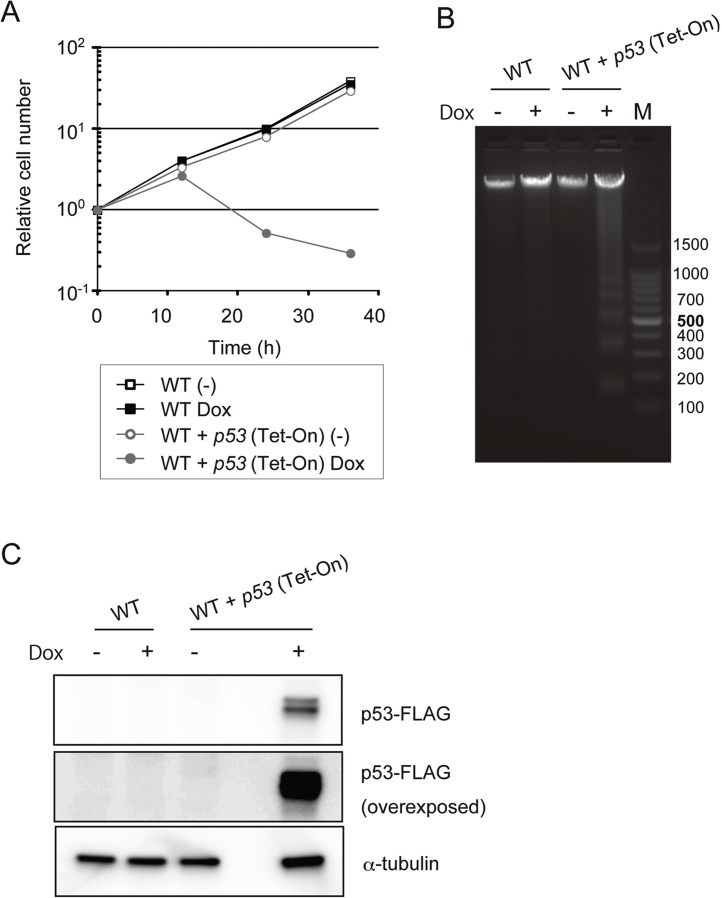

To establish a good conditional expression system in DT40 cells, we applied the newly developed Tet-On 3G system in which both the tetracycline response elements present in the promoter [20] and the tetracycline-controlled transactivator protein [21] were optimized to achieve low background and high expression. We first examined the effects of expressing p53, thought to be inactive in DT40 cells [22]. p53 expression is likely detrimental to DT40 cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis, similarly to its effect in other cancer cell lines [23]. To this purpose, we cloned amplified chicken p53 using a DT40 cDNA library made by the reverse transcription reaction. Cloned p53 was sequenced and we found mutations in both alleles of p53 in DT40 cells. One is a premature stop codon mutation that leads to a C-terminal truncated protein (1–254 amino acids), the other is a deletion mutation in the C-terminus further accompanied by a frame shift (Supplementary Fig. 1). To obtain intact chicken p53, the premature stop codon of the first allele of p53 was corrected by site directed mutagenesis and the new allele was cloned into the pTRE3G mCherry vector, which allows monitoring of the expression of target proteins by detecting the concurrently expressed mCherry. Wild-type (WT) DT40 cells were co-transfected with p53/TRE3G mCherry construct and the pCMV-Tet3G vector, which contains a Neo resistant marker, and several clones that expressed mCherry after Dox addition were selected. Expression of p53, induced by addition of Dox, immediately blocked cell growth (Fig. 1A) and led to apoptosis as detected by DNA ladder formation (Fig. 1B). In the absence of Dox, the cells containing Tet-On-p53 grew as fast as WT (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that the Tet-On 3G system is proficient at inducing p53 at levels high enough to kill DT40 cells. In addition, no detectable leaky expression of p53 in the absence of Dox was observed as assessed by examining protein levels by Western blotting (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Cellular effects associated with inducible p53 in chicken DT40 cells. (A) Growth curves. WT or WT + p53 (Tet-On) cells (1 × 105) were inoculated in 1 ml of medium and passaged every 12 h. Dox was added at time 0. (B) DNA fragmentation assay. Genomic DNA was prepared and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA ladders were detected by staining with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide. M indicates the 100 bp DNA Ladder marker. (C) Monitoring of p53-FLAG. Whole cell lysates were prepared from cells cultured in the absence or the presence of Dox for 12 h. p53-FLAG and α-tubulin (loading control) were detected by Western blotting.

3.2. Measurement of HR-dependent DSB repair using Tet-On 3G I-SceI system

By using a similar approach, we next expressed I-SceI, a homing endonuclease commonly used in various reporter assay (such as DR-GFP) that are based on induced DSBs at I-SceI sites [24]. Repair by HR restores a functional cassette, in this case GFP, the expression levels of which can be conveniently monitored via FACS. In these assays, I-SceI is usually introduced by transfection. However, the transfection efficiency varies greatly with the cell line and the transfection procedure itself causes cytotoxicity. Furthermore, the expression levels of I-SceI in each cell are not constant, being dependent on the level of transfected plasmids. To overcome these caveats, we applied the Tet-On 3G system described above also to I-SceI. After transfection of 30 μg of I-SceI/TRE3G mCherry vector together with 5 μg of pCMV-Tet3G vector to 107 of cells and following drug selection by G418, we got 22 drug resistance clones, 10 of which expressed mCherry after Dox addition. mCherry expression ratios of these clones were from 99.26% to 99.9%, 72 h after Dox addition. None of these clones displayed leaky expression monitored by mCherry in the absence of Dox. One clone out of the ten that expressed high levels of mCherry was picked up and further characterized phenotypically. In the absence of Dox, no cells expressing mCherry (or I-SceI) could be detected (Fig. 2A). Addition of Dox, however, induced mCherry on 98.5% of living population within 48 h (Fig. 2A and B). mCherry induction was kept in 96.9% of living population even after 120 h (Fig. 2A and B). Expressed I-SceI efficiently elicited recombination in the DR-GFP construct, making 3.7% of the living population GFP positive already after 48 h. The induction frequency is much higher than that induced by transient transfection using the Amaxa Nucleofector, so far thought to achieve maximum transfection efficiency in DT40 cells [24]. Notably, an advantage of the Tet-On 3G system is its ability to ensure consistent and continuous expression levels of I-SceI, compared to the ones achieved by transient transfection [24]. Because the population of GFP positive cells increased gradually following I-SceI induction (Fig. 2B), we concluded that most of DSBs are repaired without base pair change and therefore are likely re-cut by I-SceI again. GFP positive population reached a plateau around 20%, 8 days after the addition of Dox (Fig. 2B). Likely, at this time, I-SceI sites were either replaced by upstream donor sequences (20%) or mutated due to the DSB end processing (the rest of 80%). DSBs are generally repaired by two major pathways: NHEJ that ligates broken DNA ends with no regard for homology, and by homology-directed repair that relies on DSBs being processed to expose single strand ends, which can then either invade homologous double-stranded (ds) DNA, a process known as HR, or anneal with other homologous ssDNA, a process known as single-strand annealing [1]. The I-SceI -induced recombination frequency is highly up-regulated in NHEJ-deficient mutants, suggesting that the DSBs induced by I-SceI are predominantly repaired by NHEJ in DT40 cells, and in the absence of NHEJ activity, they are funneled toward HR [25].

To recapitulate this feature in our system, we expressed I-SceI in the NHEJ mutant XRCC4/− containing the DR-GFP reporter assay. NHEJ depends on the LigaseIV/XRCC4/XLF ligation complex activity [26]. We note that chicken XRCC4 is located on chromosome Z and therefore only one targeting disruption is enough to obtain XRCC4 deficient cell lines [19]. In line with the notion above on the predominance of NHEJ in repairing I-SceI -induced DSBs, XRCC4/− cells showed highly elevated levels of HR, with about 25% of total cell population being GFP-positive 48 h after I-SceI induction as compared to about 5% in WT cells (Fig. 2C). Altogether, these results indicate that the Tet-On 3G system is a powerful tool that can be successfully applied to induce the expression of various types of genes without leaky expression in the absence of Dox.

3.3. Characterization of the cytotoxic effect of the BRC4 peptide

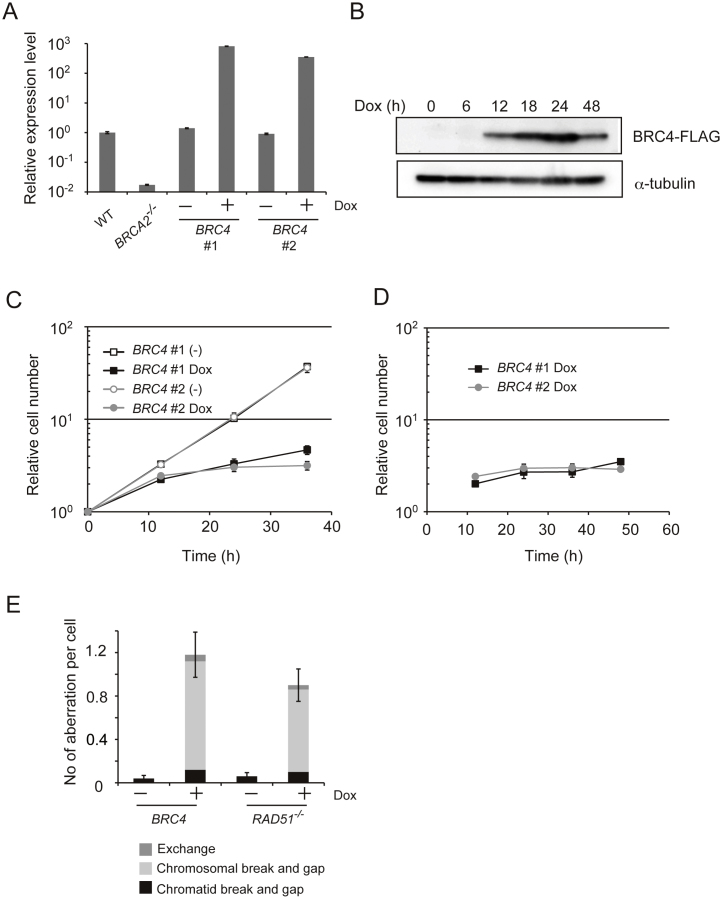

With the purpose of examining in vivo the effects of the BRC repeats of BRCA2 on DNA repair/recombination and cell viability, we next applied the Tet-On 3G system to BRC4. The amino acid sequence identity of chicken BRCA2 with that of the human homolog is 40%, and while human BRCA2 has eight BRC repeats, chicken BRCA2 contains only the BRC-1, 2, 4, 7, and 8 repeats [27]. Because BRC3 and BRC4 repeats in human were characterized biochemically [5], [7], [8], [10], [11], but only BRC4 is conserved in chicken, we chose BRC4 for our study. To this end, the BRC4 peptide was tagged with the SV40 nuclear localization signal (NLS) in its N-terminus and with FLAG in its C-terminus, and expressed by the Tet-On 3G System. After transfection, several clones expressing BRC4–FLAG were obtained. Hereafter, we refer to these WT cells containing the NLS–BRC4–FLAG (Tet-On) construct as ‘BRC4′ cells. Dox addition efficiently induced mRNA and protein of BRC4 cells (Fig. 3A and B). The expression level of BRC4 mRNA at 12 h after addition of Dox is 500 to 1000-fold higher than the one observed without Dox (Fig. 3A). We then examined the growth curve of BRC4 cells and observed that BRC4 induction severely blocked cell growth already after one cell-cycle (Fig. 3C). If toxic proteins such as BRC4 are induced over a long time, the rate of Dox resistant population appears increased because of the ensuing cell death (Fig. 3B, 48 h time point). To eliminate the Dox resistant population from our analysis, we repeated the experiment counting the number of mCherry expressing cells, which should also express BRC4 peptide simultaneously, and found that BRC4 expressing cells clearly stopped growing (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

High levels of BRC4 cause cytotoxicity. (A) Relative BRC4 expression level measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). WT, BRCA2−/− (negative control), and individually obtained 2 clones of BRC4 cells (WT + BRC4 (Tet-On) cells) were incubated in the presence or absence of Dox for 12 h when RNA was isolated and converted to cDNA. The cDNA was amplified with GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix. (B) Expression of the BRC4–FLAG peptide. Whole cell lysates were prepared from BRC4 #1 cells cultured in the presence of Dox for the indicated times. BRC4–FLAG and α-tubulin (loading control) were detected by Western blotting. (C) Growth curves. Individually obtained 2 clones of BRC4 cells (1 × 105) were inoculated in 1 ml of medium and passaged every 12 h. Dox was added at time 0. (D) Growth curves of mCherry positive cells. The number of cells expressing mCherry was counted every 12 h. (E) Number of chromosomal aberrations in RAD51−/− cells expressing hsRAD51 from a Tet-inducible promoter and in BRC4 cells after treatment with Dox for 18 h (RAD51−/− + hsRAD51 cells) or for 24 h (BRC4 cells).

In addition to cytotoxicity, expression of BRC4 also induced a large number of chromosomal aberrations of both gap and break types (Fig. 3E). This phenotype is reminiscent of the chromosomal aberrations accumulating upon inhibition of RAD51 in vertebrate and murine cells [18], [28], although no major effects on RAD51 levels were observed upon BRC4 induction (data not shown and see below). DT40 cells knocked out for the essential RAD51 gene, but expressing the Homo sapiens RAD51 transgene (hsRAD51) under the control of a Tet-repressible promoter, showed a similar pattern of chromosomal aberrations with the one observed upon BRC4 overexpression (Fig. 3E) and [18]). Thus, BRC4 induction leads to cytotoxicity that is associated with chromosome aberrations.

3.4. Characterization of the recombination and proliferation defects of BRC4 cells

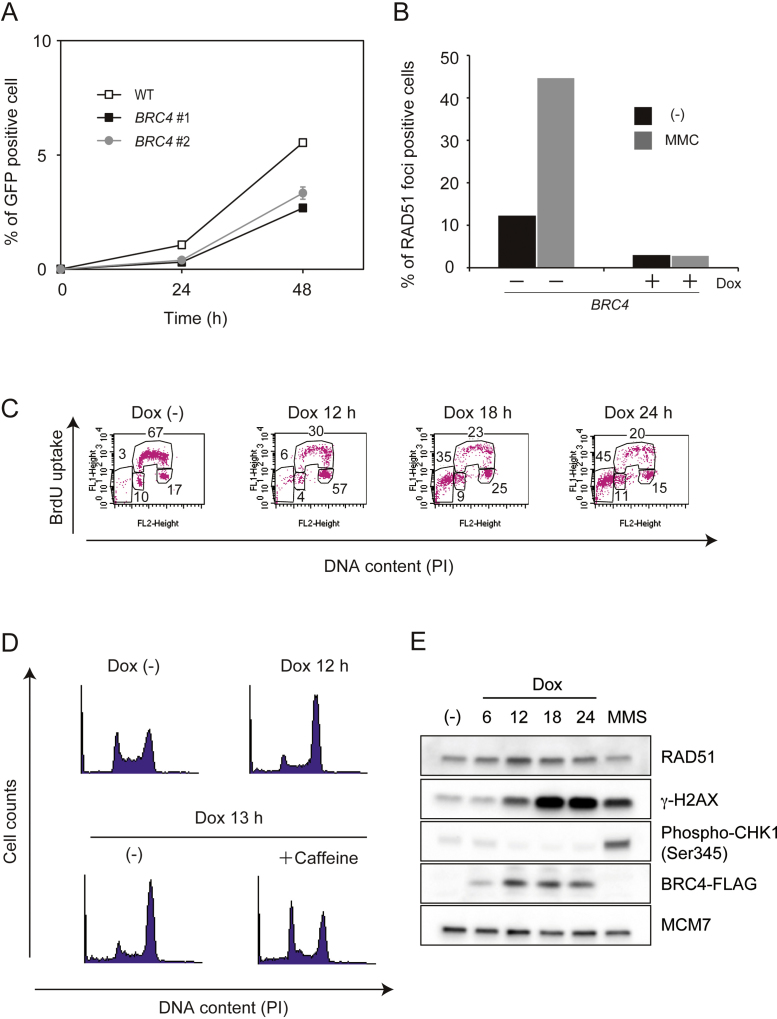

BRC4 binds RAD51, inhibits its polymerization and suppresses HR [6], [10]. To address whether inhibition of HR underlies the cytotoxicity associated with BRC4 overexpression, we examined the effect of BRC4 overexpression on I-SceI -induced HR. To this end, we constructed cell lines co-expressing I-SceI and BRC4. The HR frequency – assessed as GFP positive cells – was reduced almost by half in BRC4 cells (Fig. 4A). In addition, BRC4 induction also suppressed RAD51 foci formation both in unperturbed conditions or mitomycin C (MMC)-treated cells (Fig. 4B). Together, these results indicate that BRC4 overexpression suppresses HR. To address if cell-cycle arrest underlies the cytotoxicity associated with BRC4 overexpression, we monitored the cell cycle distribution by FACS analysis using the Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) antibody and propidium iodide (PI). BRC4 cells showed a prominent G2/M arrest 12 h after Dox addition, with the percentage of subG1 population increasing at later time points (Fig. 4C). To understand whether BRC4 cells arrested in the G2 phase of the cell cycle because of damage checkpoint activation or rather accumulated in M phase, BRC4 cells were incubated with caffeine, an ATM/ATR inhibitor, 12 h after Dox addition. The G2/M arrest associated with BRC4 overexpression was suppressed by caffeine addition (Fig. 4D), indicating that the BRC4-induced cell cycle arrest involved the G2/M checkpoint. We further monitored which branch of the damage checkpoint is induced upon BRC4 overexpression. BRC4 did not cause ATR-dependent CHK1 phosphorylation, but induced ATM-dependent γ-H2AX phosphorylation [29] (Fig. 4E). These results indicate that BRC4 mainly creates DSBs in G2 without prior activation of the replication checkpoint, and that the accumulation of chromosomal breaks and gaps (see Fig. 3E) triggers ATM-mediated arrest in the G2 phase of the cell cycle.

Fig. 4.

BRC4 suppresses homologous recombination and activates the G2/M checkpoint, but not the ATR replication checkpoint. (A) Homologous recombination (HR) repair assay using the I-SceI induced DSB formation at the DR-GFP reporter (see Fig. 2). Percentage of cells that underwent HR (measured as cells expressing GFP) is plotted. (B) Rad51 focus formation. BRC4 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Dox for 18 h. Cells were exposed to 500 ng/ml of MMC for 1 h, then washed, and sampled after 1 h. At least 100 cells were scored for each preparation. Identical trends were observed in two independent experiments. (C) Cell cycle distribution of BRC4 cells. Cells were cultured in the presence of Dox for the indicated times, pulse-labeled with BrdU for 15 min, and harvested. The cells were stained with FITC anti-BrdU to detect BrdU uptake and with propidium iodide (PI) to detect DNA. The vertical axis represents BrdU uptake and horizontal axis represents total DNA. The gates represent SubG1 (apoptotic cells), G1, S and G2/M phase from left to right, in this order. Numbers show the percentage of cells falling in each gate. (D) BRC4 cells were cultured in the presence of Dox for 12 h, further cultured in the presence or absence of Caffeine for 1 h and used for FACS analysis. (E) BRC4 cells were cultured in the presence of Dox for indicated times and whole cell lysates were prepared from each time points. RAD51, γ-H2AX, pCHK1 S345, BRC4–FLAG and MCM7 (loading control) were detected by Western blotting.

3.5. BRC4 cytotoxicity is dependent on the amount of BRCA2

The role of BRCA2 in HR is crucial and very complex. BRCA2 does not simply stimulate RAD51 binding to DNA, but modulates the DNA binding affinity of RAD51 based on the structural characteristics of DNA [10]. In addition, by keeping RAD51 in a minimal oligomeric state, the C-terminal domain of BRCA2 also impinges on RAD51 ability to assemble nucleofilaments required to initiate HR strand exchange [30], [31], [32], [33]. Furthermore, while RAD51 overexpression compensates the deficiency in RAD51 paralogs and BRCA1 in terms of cellular sensitivity to cisplatin (CDDP) and MMC [17], [34], it negatively affects cell growth and aggravates the hypersensitivity of BRCA2tr/− cells (BRC3 truncated BRCA2 mutant) to genotoxic agents [35]. These observations were interpreted as to indicate that BRCA2 has a role in suppressing “inappropriate” binding of RAD51 to DNA, whereas RAD51 paralogs and BRCA1 simply facilitate RAD51 polymerization. This idea, together with the effects observed following BRC4 induction (Fig. 3), made us hypothesize that endogenous BRCA2 might also suppress RAD51 function through its BRC repeats and/or C-terminal domain or that the observed cytotoxicity associated with BRC4 induction might be dependent on the presence of other BRC repeats or the C-terminus of BRCA2, proposed to play a regulatory role in BRC repeat-mediated RAD51 nucleofilament disassembly [31], [32] or formation [33].

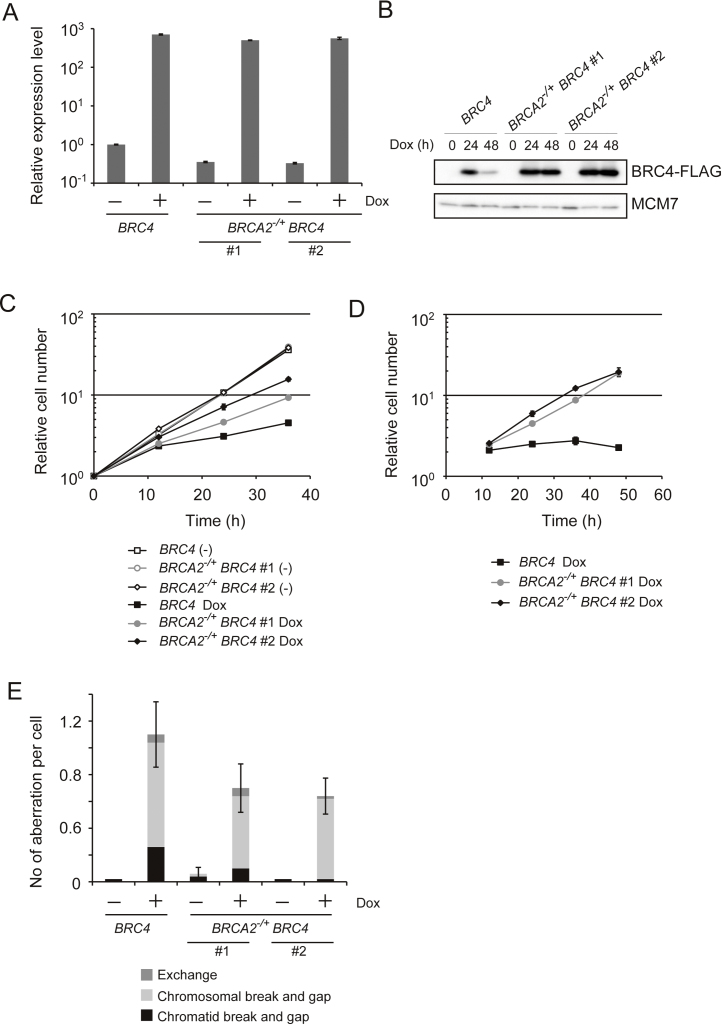

To test the above hypotheses, we introduced BRC4 into BRCA2−/+ heterozygous cells as BRCA2−/− cells are very slow growing [15], making it difficult to evaluate the cytotoxic effects associated with BRC4. Quantitative real time PCR revealed that two individual clones of BRCA2−/+ BRC4 cells expressed about half the level of BRC4 mRNA in the absence of Dox (Fig. 5A), indicating that both alleles of BRCA2 are equally active in DT40 cells. In the presence of Dox, comparable levels of BRC4 mRNA and protein were induced in BRCA2−/+ BRC4 cells and BRC4 cells (Fig. 5A and B, 24 h). Notably however, BRCA2−/+ BRC4 cells grew much better than BRC4 cells in the presence of Dox (Fig. 5C). By eliminating the mCherry negative fraction (and therefore the Dox resistant population), the difference in growth became even more prominent (Fig. 5D). The chromosomal breaks/gaps associated with BRC4 induction were also reduced in BRCA2−/+ cells (Fig. 5E). These results demonstrate that endogenous BRCA2 contributes to BRC4 cytotoxicity, most likely by suppressing RAD51 polymerization or RAD51 nuclear filament formation.

Fig. 5.

BRC4 cytotoxicity depends on endogenous BRCA2. (A) Relative BRC4 expression level measured by qPCR. BRC4 cells and individually obtained 2 clones of BRCA2−/+ BRC4 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Dox for 12 h and RNA was isolated. Isolated cDNA was used for qPCR. (B) Expression of BRC4–FLAG peptide. Whole cell lysates were prepared from each cell line cultured in the presence of Dox for the indicated times. BRC4–FLAG and MCM7 (loading control) were detected by Western blotting. (C) Growth curves. BRC4 or individually obtained 2 clones of BRCA2−/+ BRC4 cells (1 × 105) were inoculated in 1 ml of medium and passaged every 12 h. Dox was added at time 0. (D) Growth curves of mCherry positive cells. The number of cells expressing mCherry was counted every 12 h. (E) Number of chromosomal aberrations in BRC4 and BRCA2−/+ BRC4 cells after treatment with Dox for 24 h.

3.6. BRC4 cytotoxicity is independent of the NHEJ pathway

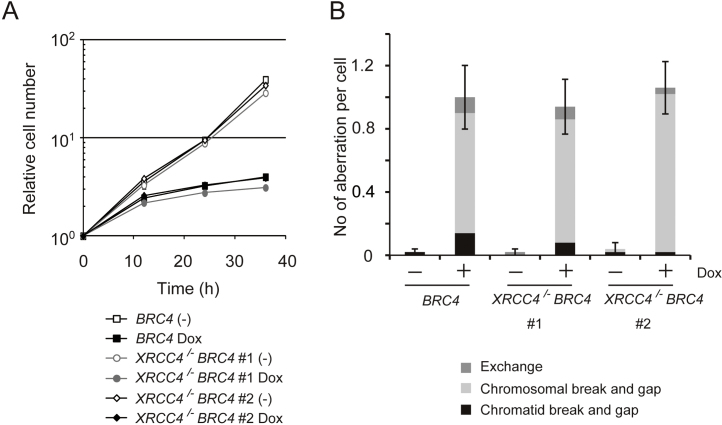

NHEJ acts by joining, often in an error-prone manner, the two ends of a DSB through the activation of the LigaseIV/XRCC4/XLF ligation complex [26]. We asked if BRC4-induced DNA damage/cytotoxicity, which appeared to be related to disruption of RAD51 and therefore to HR activity (Figs. 3C–E and 4A and B), is mediated by NHEJ. To address this question, we disrupted the XRCC4 gene, an essential co-factor of LigaseIV, in BRC4 cells. Differently from BRCA2+/− BRC4 cells (see Fig. 5), XRCC4/− BRC4 cells were indistinguishable from BRC4 cells as assessed by cell growth and chromosomal aberration phenotypes (Fig. 6A and B). These results indicate that NHEJ is neither involved in repairing the DNA damage associated with high levels of BRC4 (in which case XRCC4/− BRC4 cells are expected to have more severe phenotypes than BRC4 cells) nor responsible for the cytotoxicity and chromosomal aberrations observed in BRC4 cells (in which case XRCC4/− BRC4 cells would be expected to have alleviated phenotypes).

Fig. 6.

BRC4-induced cytotoxicity is not dependent on non-homologous end joining. (A) Growth curves. BRC4 and individually obtained 2 clones of XRCC4/− BRC4 cells (1 × 105) were inoculated in 1 ml of medium and passaged every 12 h. Dox was added at time labeled 0. (B) Number of chromosomal aberrations in BRC4 and XRCC4/− BRC4 cells after treatment with Dox for 24 h.

3.7. BRC4 cytotoxicity is dependent on the RAD51 amount

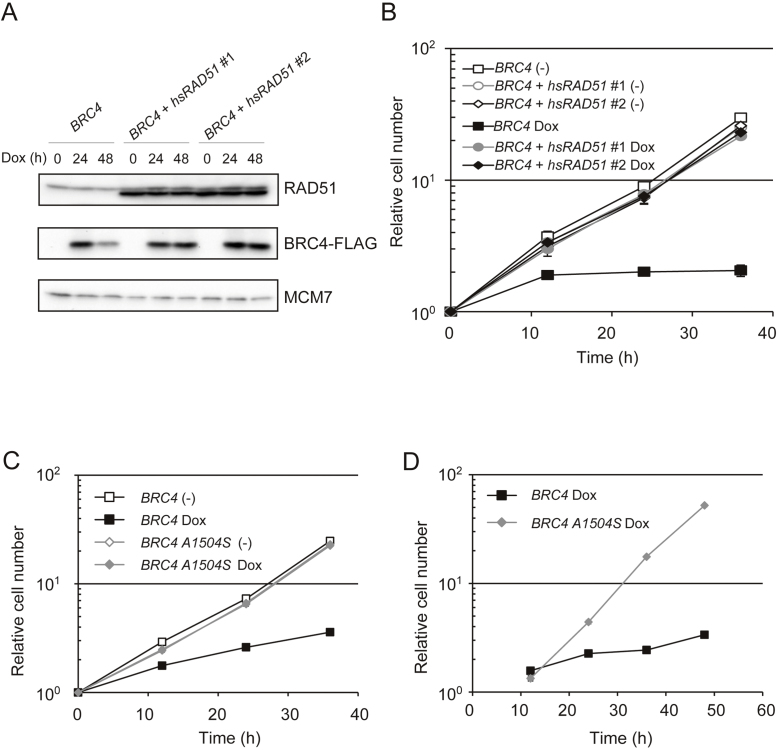

In vitro and structural studies have shown the highly selective binding of BRC4 peptide to RAD51 [6], [8]. To address the selectivity of BRC4 for RAD51 in vivo and assess if this accounts for its cytotoxicity (Fig. 3) and suppressive effect on HR (Fig. 4), we overexpressed hsRAD51 in BRC4 cells (described as BRC4 + hsRAD51) (Fig. 7A). In contrast to BRCA2 deficient cells, whose growth rate and cisplatin sensitivity are aggravated by RAD51 overexpression [35], excess amount of RAD51 completely rescued the lethality of BRC4-induced cells (Fig. 7B). While both BRCA2−/− cells and BRC4-induced cells show defects in RAD51 foci formation ([15] and see Fig. 4B), the above phenotype clearly separates BRCA2−/− cells from BRC4-induced cells. We further confirmed the selectivity of BRC4 for RAD51 by using a BRC4 variant, BRC4-A1504S, deficient for RAD51 interaction [36]. Differently from BRC4, overexpression of BRC4-A1504S did not affect cell growth (Fig. 7C and D). These results, taken together with the ones above, substantiate the notion that the cytotoxicity associated with high levels of BRC4 arises specifically from its inhibitory binding to RAD51.

Fig. 7.

RAD51 overexpression rescues BRC4-induced cytotoxicity. (A) Expression of RAD51 and BRC4–FLAG peptide. Whole cell lysates were prepared from each cell lines cultured in the presence of Dox for the indicated times. RAD51, BRC4–FLAG and MCM7 (loading control) were detected by Western blotting. The upper and lower bands of RAD51 show chicken and human RAD51, respectively. (B) Growth curves. BRC4 and individually obtained 2 clones of BRC4 + hsRAD51 cells (1 × 105) were inoculated in 1 ml of medium and passaged every 12 h. Dox was added at the time point labeled 0. (C) Growth curves of BRC4 and BRC4-A1504S cells in the presence or absence of Dox. 1 × 105 cells of the indicated genotype were inoculated in 1 ml of medium and passaged every 12 h. Dox was added at time 0. (D) Growth curves of mCherry positive BRC4 and BRC4-A1504S cells. The number of cells expressing mCherry was counted every 12 h.

3.8. BRC4 cytotoxicity is enhanced by DNA damaging agents, but counteracted by RAD51 overexpression

RAD51 is essential for both cell survival and HR repair. Previous studies showed that BRC4 expression induces hypersensitivity to γ-irradiation and DNA damaging agents such as CDDP [7], [14]. We examined if, similarly to RAD51 deficiency, BRC4 induction would affect not only cell growth (Fig. 3) but also the cellular response to DNA damage. Because HR deficient mutants such as BRCA2 or RAD51 paralog knockout cells are highly sensitive to olaparib and camptothecin (CPT) [15], [37], we incubated BRC4 cells with either of these drugs in the presence or absence of Dox (Fig. 8A and B). We used low concentrations of drugs, 0.5 μM for olaparib and 5 nM for CPT, respectively, that do not impact on cell growth in WT cells. Indeed, BRC4 cells showed normal growth in the absence of Dox, but BRC4-induced cells showed growth defects (see also Fig. 3C) that were exacerbated following treatment with low doses of these drugs (Fig. 8A and B). These results show that inhibition of RAD51 function by BRC4 not only induces chromosomal damage, but also inhibits DNA repair [7], [14]. Because RAD51 overexpression counteracted the cytotoxicity associated with BRC4 induction (Fig. 7), we tested if it may also counteract the DNA repair defects of BRC4-induced cells. Differently from XRCC3−/− cells, used here as control because of their hypersensitivity to olaparib [37], BRC4 cells overexpressing RAD51 did not show high sensitivity to olaparib either in the absence or presence of Dox that induces BRC4 (Fig. 8C). These results indicate that both the cytotoxicity and the DNA repair defects associated with BRC4 induction are related to its inhibitory effect on RAD51 and can be overcome by increasing RAD51 amounts. These results thus suggest that HR is proficient in cells overexpressing both BRC4 and RAD51. Surprisingly, bright RAD51 foci induced by MMC were abolished in cells overexpressing both RAD51 and BRC4, whereas faint foci could still be observed (Fig. 8D and E). Collectively, these results indicate that BRC4 affects RAD51 polymerization even if RAD51 is overexpressed in the cells, but that the small RAD51 factories assembled under these conditions are proficient in mediating HR-mediated DNA repair.

4. Discussion

Conditional expression systems are powerful tools to study the molecular mechanisms underlying the cytotoxicity associated with specific proteins. Though the expression of target proteins should be completely repressed in ‘off state’, old Tet-On systems suffered of leaky expression problems. In this study, we applied the newly developed Tet-On 3G system to chicken DT40 cells to study three proteins. The expression of p53, I-SceI and BRC4 analyzed here was completely repressed in the absence of Dox, whereas Dox addition induced expressions of these genes, thus establishing the Tet-On 3G system as suitable in DT40 research. Analysis of the phenotypes associated with specific gene inductions also revealed novel aspects on the mode of action of these proteins, particularly on the mode of action of BRC4 and BRCA2, which are discussed below.

High levels of BRC4 induced cell lethality and chromosomal type breaks, reminiscent of the cytotoxicity associated with radiation or RAD51 deficiencies (Fig. 3). Although none of the past studies using BRC4 or other Brc repeats reported their cytotoxicity [7], [8], [14], the difference between the past studies and ours likely comes from the expression levels of BRC4 as in our system high amounts of BRC4 were induced (Fig. 3A). Another possible reason for this new phenotype revealed here may be due to species differences and related changes of critical residues within the BRC repeats that impact on the strength of the BRC4–Rad51 interaction [38]. One of these examples is the V1532 residue of the BRC4 repeat of human BRCA2, which is substituted by isoleucine in canine species as well as in chicken BRCA2 [27]. In this vein, a recent study reported enhanced binding of human BRC4 to RAD51 as well as RAD51–DNA dissociation activity by replacing several amino acids of BRC4 [36].

The cytotoxic effect of BRC4 was further enhanced by the addition of low concentrations of olaparib and CPT (Fig. 8A and B), indicating that BRC4 not only induces chromosomal breaks (Fig. 3E) but that it also inhibits DNA repair simultaneously. The cytotoxicity and inhibition of DNA repair by BRC4 completely depended on RAD51 (Fig. 7, Fig. 8). These results indicate that the target of BRC4 in cells is RAD51 and that BRC4 blocks RAD51 polymerization in a competitive manner, together with endogenous BRCA2, likely in a fashion that depends on the presence of other BRC repeats or C-terminal residues of BRCA2 (Fig. 5). Alternatively, the effect of BRC4 induction may be dependent on the endogenous BRC4 repeat. In this regard, we note that although the level of BRC4 mRNA induced by the Tet-On 3G system was much higher than that of endogenous BRCA2 mRNA, the stability of the BRC4 peptide may be lower than that of BRCA2. Further studies will be required to examine whether full length BRCA2 also inhibits RAD51 polymerization when overexpressed and to clarify a possible interplay between BRC4 and other BRCA2 domains in inhibiting RAD51-mediated DNA repair.

On the other hand, the interplay between BRC4 and BRCA2 in mediating cytotoxicity might reflect that distinct BRC repeats have separate activities in controlling genome integrity. Thus, while BRC4 plays a prominent role in regulating recombination repair, other BRC repeats may be involved in controlling mitotic cell cycle arrest, as it has been recently suggested for the BRC5 repeat of human BRCA2 [39]. While the BRC5 repeat itself is not conserved in chicken BRCA2, it is possible that analogous mechanisms exist, or that other BRC repeats of chicken BRCA2 substitute for human BRC5 in what regards the interaction with factors implicated in cell division. The finding that BRC4 overexpression induces both lesions and ATM-mediated cell-cycle arrest (Fig. 3) does not exclude this view, but other explanations remain possible. For instance, BRC4 and other domains of BRCA2 may coordinately modulate DNA repair, either by similar or divergent roles. Interestingly, our results indicate that NHEJ is not involved in processing BRC4-induced DNA damage (Fig. 6), even in the absence of proper HR function. While this could simply reflect a cell cycle-mediated down-regulation of NHEJ in G2, similarly to what has been reported in yeast [40], [41], [42], it is also possible that other BRC repeats or domains of BRCA2 play a role in suppressing alternative error-prone repair mechanisms, such as NHEJ, thus explaining the tumor suppressor function of BRCA2.

In addition to shedding new light on the BRCA2 and BRC4 function in vivo, the results of this study indicate that BRC4 is proficient at killing proliferating cancer cells as well as enhancing the cytotoxic effects of olaparib and CPT (Fig. 8A and B) in a manner completely dependent on its inhibitory activity on RAD51. These features of BRC4 may be useful as a molecularly-targeted adjunctive agent to enhance the effect of other anti-cancer drugs. It is of note that over 35% of breast, ovarian and prostate carcinoma associated with germline BRCA mutations do not respond to olaparib [43] nor do the sporadic breast cancers not associated with BRCA mutations. It is likely that (concomitant) inhibition of RAD51 function in tumors that depend on HR for viability would lead to improved drug therapy. Although there is a considerable barrier to efficiently deliver peptide medicines to the focus of disease in patients, developments in drug delivery systems may make such peptide medications feasible in the future. Several specific RAD51 inhibitors have been reported recently [44], [45], [46]. Although it is still unknown if similarly to BRC4 these reagents specifically inhibit RAD51, together with BRC4 peptides, they constitute attractive anti-cancer drug candidates and useful in vitro tools to study the interplay between different repair pathways and their impact on genome integrity.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

-

•

Takuya Abe is in the

-

•

IFOM, The FIRC Institute for Molecular Oncology Foundation, IFOM-IEO Campus, Via Adamello 16, 20139 Milan, Italy. Tel.: +39 02 574 303 259; e-mail: takuya.abe@ifom.eu.

-

•

Dana Branzei is in the

-

•

IFOM, The FIRC Institute for Molecular Oncology Foundation, IFOM-IEO Campus, Via Adamello 16, 20139 Milan, Italy. Tel.: +39 02 574 303 259; e-mail: dana.branzei@ifom.eu.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. S. Takeda (Kyoto University) for the gifts of BRCA2−/+, XRCC3−/−, RAD51−/− + hsRAD51 cells and DR-GFP/chicken OVA targeting construct, Dr. H. Arakawa (IFOM) for helpful discussions, and Dr. H. Kajiho (IFOM) for technical advice on microscope experiments. This work was supported by the European Research Council [REPSUBREP 242928]; the Italian Association for Cancer Research [AIRC IG grant 10637]; Fondazione Telethon [grant GGP12160]; and FIRC. T. Abe was partly supported by the Structured International Post Doc Program (SIPOD) fellowship co-funded in the context of the FP7 Marie Curie Actions—People.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.08.003.

Contributor Information

Takuya Abe, Email: takuya.abe@ifom.eu.

Dana Branzei, Email: dana.branzei@ifom.eu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Moynahan M.E., Jasin M. Mitotic homologous recombination maintains genomic stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:196–207. doi: 10.1038/nrm2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein H.L. The consequences of Rad51 overexpression for normal and tumor cells. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2008;7:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costantino L., Sotiriou S.K., Rantala J.K., Magin S., Mladenov E., Helleday T., Haber J.E., Iliakis G., Kallioniemi O.P., Halazonetis T.D. Break-induced replication repair of damaged forks induces genomic duplications in human cells. Science. 2014;343:88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1243211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venkitaraman A.R. Chromosome stability, DNA recombination and the BRCA2 tumour suppressor. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001;13:338–343. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong A.K., Pero R., Ormonde P.A., Tavtigian S.V., Bartel P.L. RAD51 interacts with the evolutionarily conserved BRC motifs in the human breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31941–31944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.31941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies A.A., Masson J.Y., McIlwraith M.J., Stasiak A.Z., Stasiak A., Venkitaraman A.R., West S.C. Role of BRCA2 in control of the RAD51 recombination and DNA repair protein. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C.F., Chen P.L., Zhong Q., Sharp Z.D., Lee W.H. Expression of BRC repeats in breast cancer cells disrupts the BRCA2–Rad51 complex and leads to radiation hypersensitivity and loss of G(2)/M checkpoint control. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:32931–32935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellegrini L., Yu D.S., Lo T., Anand S., Lee M., Blundell T.L., Venkitaraman A.R. Insights into DNA recombination from the structure of a RAD51–BRCA2 complex. Nature. 2002;420:287–293. doi: 10.1038/nature01230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bork P., Blomberg N., Nilges M. Internal repeats in the BRCA2 protein sequence. Nat. Genet. 1996;13:22–23. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carreira A., Hilario J., Amitani I., Baskin R.J., Shivji M.K., Venkitaraman A.R., Kowalczykowski S.C. The BRC repeats of BRCA2 modulate the DNA-binding selectivity of RAD51. Cell. 2009;136:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nomme J., Takizawa Y., Martinez S.F., Renodon-Corniere A., Fleury F., Weigel P., Yamamoto K., Kurumizaka H., Takahashi M. Inhibition of filament formation of human Rad51 protein by a small peptide derived from the BRC-motif of the BRCA2 protein. Genes Cells. 2008;13:471–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galkin V.E., Esashi F., Yu X., Yang S., West S.C., Egelman E.H. BRCA2 BRC motifs bind RAD51–DNA filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:8537–8542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407266102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shivji M.K., Davies O.R., Savill J.M., Bates D.L., Pellegrini L., Venkitaraman A.R. A region of human BRCA2 containing multiple BRC repeats promotes RAD51-mediated strand exchange. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4000–4011. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan S.S., Lee S.Y., Chen G., Song M., Tomlinson G.E., Lee E.Y. BRCA2 is required for ionizing radiation-induced assembly of Rad51 complex in vivo. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3547–3551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qing Y., Yamazoe M., Hirota K., Dejsuphong D., Sakai W., Yamamoto K.N., Bishop D.K., Wu X., Takeda S. The epistatic relationship between BRCA2 and the other RAD51 mediators in homologous recombination. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buerstedde J.M., Takeda S. Increased ratio of targeted to random integration after transfection of chicken B cell lines. Cell. 1991;67:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90581-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takata M., Sasaki M.S., Tachiiri S., Fukushima T., Sonoda E., Schild D., Thompson L.H., Takeda S. Chromosome instability and defective recombinational repair in knockout mutants of the five Rad51 paralogs. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;21:2858–2866. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2858-2866.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonoda E., Sasaki M.S., Buerstedde J.M., Bezzubova O., Shinohara A., Ogawa H., Takata M., Yamaguchi-Iwai Y., Takeda S. Rad51-deficient vertebrate cells accumulate chromosomal breaks prior to cell death. EMBO J. 1998;17:598–608. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abe T., Ishiai M., Hosono Y., Yoshimura A., Tada S., Adachi N., Koyama H., Takata M., Takeda S., Enomoto T., Seki M. KU70/80, DNA-PKcs, and Artemis are essential for the rapid induction of apoptosis after massive DSB formation. Cell. Signal. 2008;20:1978–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loew R., Heinz N., Hampf M., Bujard H., Gossen M. Improved Tet-responsive promoters with minimized background expression. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:81. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou X., Vink M., Klaver B., Berkhout B., Das A.T. Optimization of the Tet-On system for regulated gene expression through viral evolution. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1382–1390. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takao N., Li Y., Yamamoto K. Protective roles for ATM in cellular response to oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2000;472:133–136. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine A.J. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X., Takenaka K., Takeda S. PTIP promotes DNA double-strand break repair through homologous recombination. Genes Cells. 2010;15:243–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukushima T., Takata M., Morrison C., Araki R., Fujimori A., Abe M., Tatsumi K., Jasin M., Dhar P.K., Sonoda E., Chiba T., Takeda S. Genetic analysis of the DNA-dependent protein kinase reveals an inhibitory role of Ku in late S-G2 phase DNA double-strand break repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:44413–44418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahaney B.L., Meek K., Lees-Miller S.P. Repair of ionizing radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks by non-homologous end-joining. Biochem. J. 2009;417:639–650. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takata M., Tachiiri S., Fujimori A., Thompson L.H., Miki Y., Hiraoka M., Takeda S., Yamazoe M. Conserved domains in the chicken homologue of BRCA2. Oncogene. 2002;21:1130–1134. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim D.S., Hasty P. A mutation in mouse rad51 results in an early embryonic lethal that is suppressed by a mutation in p53. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:7133–7143. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burma S., Chen B.P., Murphy M., Kurimasa A., Chen D.J. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:42462–42467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petalcorin M.I., Galkin V.E., Yu X., Egelman E.H., Boulton S.J. Stabilization of RAD-51–DNA filaments via an interaction domain in Caenorhabditis elegans BRCA2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:8299–8304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702805104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies O.R., Pellegrini L. Interaction with the BRCA2 C terminus protects RAD51–DNA filaments from disassembly by BRC repeats. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:475–483. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esashi F., Galkin V.E., Yu X., Egelman E.H., West S.C. Stabilization of RAD51 nucleoprotein filaments by the C-terminal region of BRCA2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:468–474. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holthausen J.T., van Loenhout M.T., Sanchez H., Ristic D., van Rossum-Fikkert S.E., Modesti M., Dekker C., Kanaar R., Wyman C. Effect of the BRCA2 CTRD domain on RAD51 filaments analyzed by an ensemble of single molecule techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6558–6567. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin R.W., Orelli B.J., Yamazoe M., Minn A.J., Takeda S., Bishop D.K. RAD51 up-regulation bypasses BRCA1 function and is a common feature of BRCA1-deficient breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9658–9665. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hatanaka A., Yamazoe M., Sale J.E., Takata M., Yamamoto K., Kitao H., Sonoda E., Kikuchi K., Yonetani Y., Takeda S. Similar effects of Brca2 truncation and Rad51 paralog deficiency on immunoglobulin V gene diversification in DT40 cells support an early role for Rad51 paralogs in homologous recombination. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:1124–1134. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1124-1134.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nomme J., Renodon-Corniere A., Asanomi Y., Sakaguchi K., Stasiak A.Z., Stasiak A., Norden B., Tran V., Takahashi M. Design of potent inhibitors of human RAD51 recombinase based on BRC motifs of BRCA2 protein: modeling and experimental validation of a chimera peptide. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:5782–5791. doi: 10.1021/jm1002974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murai J., Huang S.Y., Das B.B., Renaud A., Zhang Y., Doroshow J.H., Ji J., Takeda S., Pommier Y. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5588–5599. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ochiai K., Yoshikawa Y., Yoshimatsu K., Oonuma T., Tomioka Y., Takeda E., Arikawa J., Mominoki K., Omi T., Hashizume K., Morimatsu M. Valine 1532 of human BRC repeat 4 plays an important role in the interaction between BRCA2 and RAD51. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1771–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee M., Daniels M.J., Garnett M.J., Venkitaraman A.R. A mitotic function for the high-mobility group protein HMG20b regulated by its interaction with the BRC repeats of the BRCA2 tumor suppressor. Oncogene. 2011;30:3360–3369. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Symington L.S., Gautier J. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011;45:247–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y., Shim E.Y., Davis M., Lee S.E. Regulation of repair choice: Cdk1 suppresses recruitment of end joining factors at DNA breaks. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2009;8:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ira G., Pellicioli A., Balijja A., Wang X., Fiorani S., Carotenuto W., Liberi G., Bressan D., Wan L., Hollingsworth N.M., Haber J.E., Foiani M. DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature. 2004;431:1011–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature02964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fong P.C., Boss D.S., Yap T.A., Tutt A., Wu P., Mergui-Roelvink M., Mortimer P., Swaisland H., Lau A., O’Connor M.J., Ashworth A., Carmichael J., Kaye S.B., Schellens J.H., de Bono J.S. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu J., Zhou L., Wu G., Konig H., Lin X., Li G., Qiu X.L., Chen C.F., Hu C.M., Goldblatt E., Bhatia R., Chamberlin A.R., Chen P.L., Lee W.H. A novel small molecule RAD51 inactivator overcomes imatinib-resistance in chronic myeloid leukaemia. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013;5:353–365. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott D.E., Ehebauer M.T., Pukala T., Marsh M., Blundell T.L., Venkitaraman A.R., Abell C., Hyvonen M. Using a fragment-based approach to target protein-protein interactions. ChemBioChem. 2013;14:332–342. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Budke B., Kalin J.H., Pawlowski M., Zelivianskaia A.S., Wu M., Kozikowski A.P., Connell P.P. An optimized RAD51 inhibitor that disrupts homologous recombination without requiring Michael acceptor reactivity. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:254–263. doi: 10.1021/jm301565b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.