Abstract

Background

Ratiometric analysis with H+-sensitive fluorescent sensors is a suitable approach for monitoring apoplastic pH dynamics. For the acidic range, the acidotropic dual-excitation dye Oregon Green 488 is an excellent pH sensor. Long lasting (hours) recordings of apoplastic pH in the near neutral range, however, are more problematic because suitable pH indicators that combine a good pH responsiveness at a near neutral pH with a high photostability are lacking. The fluorescent pH reporter protein from Ptilosarcus gurneyi (Pt-GFP) comprises both properties. But, as a genetically encoded indicator and expressed by the plant itself, it can be used almost exclusively in readily transformed plants. In this study we present a novel approach and use purified recombinant indicators for measuring ion concentrations in the apoplast of crop plants such as Vicia faba L. and Avena sativa L.

Results

Pt-GFP was purified using a bacterial expression system and subsequently loaded through stomata into the leaf apoplast of intact plants. Imaging verified the apoplastic localization of Pt-GFP and excluded its presence in the symplast. The pH-dependent emission signal stood out clearly from the background. PtGFP is highly photostable, allowing ratiometric measurements over hours. By using this approach, a chloride-induced alkalinizations of the apoplast was demonstrated for the first in oat.

Conclusions

Pt-GFP appears to be an excellent sensor for the quantification of leaf apoplastic pH in the neutral range. The presented approach encourages to also use other genetically encoded biosensors for spatiotemporal mapping of apoplastic ion dynamics.

Keywords: GFP, Genetically encoded biosensor, Plant bioimaging, Apoplast, pH, Salinity, Nitrogen forms, Stress, Signaling, Ptilosarcus gurneyi, Three-channel ratio imaging

Introduction

The pH in the aqueous phase of the leaf apoplast controls multiple metabolic processes and is related to signaling cascades [1, 2]. Changing environmental conditions can alter the leaf apoplastic pH, consequently affecting processes that depend upon the apoplastic H+ concentration. Among these are the proton motive force driven transport of metabolites and mineral nutrients across the membrane. Equally important is the effect of a changing pH on the protonation state of peptides or proteins [3–7]. The protonation state of amino acid residues can alter the protein’s structure, leading to pH related conformational changes (misfolding) that impair the affinity to binding sites or its function [8]. For hormones that behave according to the anion trap mechanisms for weak acids (e.g. abscisic acid), the state of protonation is of particular importance for the compartmental distribution [9–11] and their affinity to receptors [12].

Biotic and abiotic environmental factors that influence the leaf apoplastic pH include, among others, the nitrogen nutrition [13, 14], the onset of drought, hydric stress, salinity or anoxia [15–21] and the colonisations and associations by e.g. fungal pathogens or mutualistic mycorrhiza [18, 22, 23]. Developmental and physiological processes like acid-growth, light-sensing, gravitropism or the nitrate assimilation in combination with a production of OH− after cytosolic nitrate reduction are related to apoplastic pH changes [24–30]. In this light, the need for methods that enable an in planta quantification of leaf apoplastic pH dynamics with a high spatiotemporal resolution becomes evident. Quantitative ratiometric analyses that combine H+-sensitive fluorescent dyes with microscopy based imaging techniques represent a suitable approach for spatiotemporal monitoring of pH dynamics [31–34]. However, since pH-fluorophores are not sensitive over the whole physiological pH range that can exist in the leaf apoplast, the technique of ratio imaging has some limitations. Detection of the leaf apoplastic pH value in its full span that ranges from relative neutral (6.5 to 7.0) to more acidic (below 4.0 to 5.0) [1, 27, 35–37] is not possible, because all available ratiometric pH indicators only cover a limited range of approx. 2–2.5 pH units over which pH sensitivity is most dynamic.

For the acidic pH range, the pH-sensitive dextranated fluorescein derivative Oregon Green 488 is well suited because (i) it has a pKa of 4.7 at which its pH sensitivity is most dynamic [12] and (ii) it has a tremendous photostability in combination with a good fluorescent brightness [34]. Apoplastic pH measurements in the more neutral pH range that last over hours, however, are more problematic. Besides the requirements for a pH sensitivity in the near-neutral pH range, the dye must be photostable over hours and large enough to avoid migration from the apoplastic space across the plasmalemma membrane into the cytosol. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-based dyes that are chosen for measurements in this rage (pKa of 5.92; [38]) have a low photostability and are prone to photobleaching [39], excluding them from long term measurements. 2′,7′-Bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(6)-carboxy fluorescein (BCECF), another fluorescein-based dye also appears promising as it has a pKa of 7.0 [40], but has the disadvantage that it photobleaches relatively quickly [40]. Schulte et al. [1] presented a fluorescent pH reporter protein from the orange seapen Ptilosarcus gurneyi (Pt-GFP) that, when expressed in Arabidopsis thaliana, is used as a genetically encoded pH sensor in the relatively neutral cytosol [41]. Due to its good pH responsiveness at neutral pH (pKa of 7.3), Pt-GFP is ideal for pH recordings in the near neutral range that prevails in the leaf apoplast of some plant species.

Unfortunately, these self-expressed biosensors can almost exclusively be inserted into plants that are readily transformable. This impairs the usage of these powerful genetically encoded ion sensors in crop research since almost all agricultural relevant plants are not straightforward to transform.

In this study an approach was elaborated that allowed to use Pt-GFP for ratiometric analysis of the pH in the leaf apoplast of crops such as field bean (Vicia faba L.) and oat (Avena sativa L.) that, otherwise, would need to be transformed very laborious.

It was our strategy to purify Pt-GFPs from a bacterial expression system and to test whether this ratiometric dual-excitation pH indicator can (i) be non-invasively loaded directly into the apoplast of intact plants through the stomata and whether (ii) Pt-GFPs are suitable for detecting stress-related apoplastic pH changes in the near-neutral pH range.

Material and methods

Plant cultivation

Vicia faba L., minor cv Fuego (Saaten-Union GmbH, Isernhagen, Germany) was grown under hydroponic culture conditions in a climate chamber (14/10 h day/night; 20/15°C; 60/50% humidity; Vötsch VB 514 MICON, Vötsch Industrietechnik GmbH, Balingen-Frommern, Germany) as described in detail by Geilfus and Mühling [37]. The nutrient solution had the following composition: 0.1 mM KH2PO4, 1.0 mM K2SO4, 0.2 mM KCl, 2.0 mM Ca(NO3)2 or as given in the figure legends, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 60 μM Fe-EDTA, 10 μM H3BO4, 2.0 μM MnSO4, 0.5 μM ZnSO4, 0.2 μM CuSO4, 0.05 μM (NH4)6Mo7O24. Hydroponic cultivation of Avena sativa L. was conducted in an structurally identical climate chamber with the settings and growth conditions given elsewhere [42, 43]. After 10–20 d of plant cultivation, in vivo pH recording was performed as described below.

Bacterial expression of GFPs

Pt-GFP (Acc.No. AY015995) was expressed as described in Schulte et al. [1] using the bacterial expression vector pRSETb (Invitrogen GmbH; Karlsruhe, Germany). The 6xHis-tagged fluorescent protein was purified and concentrated through a Ni2+/NTA-agarose column (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) followed by gel filtration through a NAP-25 column (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). The protein was stored frozen in PBS. Before apoplast loading, the Pt-GFP proteins were dialysed over night against Mes-buffer (5 mM MES Roth # 4256; 5 mM K2SO4; Merck # 5153) with a MWCO of 10 kDa.

Loading of pH indicators into the intact leaf apoplast

For means of in planta recording of leaf apoplastic pH values, 7.5 μg/ml of the fluorescent pH indicator Pt-GFP or 25 μM of the pH-sensitive dye Oregon Green 488-dextran (Invitrogen GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) were loaded into the leaf apoplast of intact plants following the step-by-step instructions that were given elsewhere [34]. Measurements were started 2 hours after loading.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

To visualize the Pt-GFP distribution within the leaf apoplast, CLSM imaging via a Leica TCS SP5 confocal laser scanning system (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) was carried out. For Pt-GFP excitation, the 488 nm beam line of an argon laser was chosen. Emission bandwith was 498–540 nm. Chloroplast autofluorescence was excited at 633 nm by a helium-neon laser (emission bandwith was 650 nm–704 nm). A planapochromatic objective (HC PLAN APO 20.0 × 0.70; Leica Microsystems) was used for image collection.

Image acquisition for in vivopH-recording

Fluorescence images were collected as a time series with a Leica inverted microscope (DMI6000B; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) connected to a DFC camera (DFC 360FX; Leica Microsystems) via 5-fold magnification (0.15 numerical aperture, dry objective; voxel size = 0.002 mm; HCX PL FLUOTAR L, Leica Microsystems). An HXP lamp (HXP Short Arc Lamp; Osram, Munich, Germany) was used for illumination at excitation wavelengths 387/11, 440/20 and 490/10 nm. The exposure time was 25 ms for all channels. Emission was collected at 510/84 for both Pt-GFP channels and 535/25 for both OG channels using band-pass filter in combination with a dichromatic mirror (LP518; dichroit T518DCXR BS; Leica Microsystems). Plants were supplied with aerated nutrient solution.

Ratiometric analysis

The fluorescence ratios F490/F387 (Pt-GFP) and F490/F440 (Oregon Green 488) were obtained as a measurement of pH on a pixel-by-pixel basis. Image analysis was carried out using LAS AF software (version 2.3.5; Leica Microsystems). In order to take into account a potential variability in the leaf apoplastic pH that might exist across the imaged leaf detail, ratio image was divided in 6 ROIs per ratio image and time point. Background values were subtracted at each channel. For conversion of the fluorescence ratio data gained with the Oregon Green dye into apoplastic pH values, an in vivo calibration was conducted. In brief, Oregon Green dye solutions were pH buffered and loaded into the leaf apoplast. The Boltzmann fit was chosen to fit sigmoidal curves to the calibration. Fitting yielded an area of best responsiveness in the range pH 3.9–6.3 for the Oregon Green dye [34]. When the leaves were loaded with pH buffer, all regions of the apoplast showed the same ratio signal at the same buffered pH. Despite this uniformity, the absolute pH values quoted should be viewed as approximations of the apoplastic pH [44], because we cannot exclude the possibility that the buffer reaches equilibrium with the steady-state pH environment within the leaf. Nevertheless, this does not preclude a biological interpretation of leaf apoplastic pH responses to experimental treatments, because it was demonstrated that manipulation of the PM proton pump ATPase (PM-H+-ATPase) activity with fusicoccin or vanadate lead to the expected effects on the apoplastic pH as measured by a ratiometric dye [37]. For pseudo-color display, the ratio was color-coded ranging from purple (no signal) over blue (lowest detectable pH signal) to pink (highest detectable pH signal). The Pt-GFP ratio signal was calibrated following the same procedure using citric acid/sodium citrate (3.5 ≤ pH ≤ 5.5; 10 mM), MES (5.5 ≤ pH ≤ 6.5; 50 mM), PIPES (6.0 ≤ pH ≤ 7.5; 50 mM), HEPES (7.0 ≤ pH ≤ 8.5; 50 mM) and TRIS-base/MES (8.5 ≤ pH ≤ 10.5; 50 mM).

Results and discussion

Plants respond to stress through complex signaling networks that regulate and coordinate transcriptional and physiological processes initiating adaptations that help the plant to endure under unfavorable conditions [45] and references therein; [46] and references therein. Choi et al. [46] report in accordance to other authors [2, 36, 47, 48] that apoplastic pH is one of the key factors in transmitting information regarding stress to distant unaffected plant organs [12, 18]. After all, alterations in pH have an impact on protein folding, hormone distribution, channel and transporter activity or on membrane integrity and traffic [12, 49].

There is increasing evidence that pH dynamics in the apoplast are involved in stress perception and systemic communication [2, 20, 45, 50]. To better understand the role of transient pH dynamics, the need for indicators that allow the detection of apoplastic pH in its full span ranging from relative neutral to more acidic becomes evident. While the more acid range can easily be covered by the dextranated dye Oregon Green 488, there is lack in photostable dyes that allow ratiometric dual-excitation measurements in the relatively neutral range.

The fluorescent pH reporter protein from the orange seapen Ptilosarcus gurneyi (Pt-GFP) may provide a solution since it has a very broad pH-responsiveness that also covers relatively neutral pH values and an excellent dynamic ratio range [1]. However, it has the drawback that this genetically encoded pH sensors can only be used in plants that can be genetically transformed. For this reason, the abundance of self expressed biosensors which is currently available cannot readily be used for some agricultural crop plants without considerable expenditure. In order to make these valuable indicators available, we tested an approach for non-invasively loading bacterially produced Pt-GFP into the leaf apoplast of intact plants. In order to test the suitability of this strategy, leaf apoplastic pH dynamics were induced by salt stress at the roots of field bean (Vicia faba L.) and oat (Avena sativa L.).

Localisation of leaf apoplastic loaded Pt-GFP

Studies on leaf apoplastic ion concentrations require an ion indicator that is reliably localized in the apoplast and not unintentionally in cellular compartments, the cytosol or the vacuole. Otherwise, signals from the e.g. neutral cytosol or the very acidic vacuole would affect the apoplastic pH estimations. Additionally, it must be ensured that the bacterially produced Pt-GFP proteins can be inserted into the leaf apoplast by liquid mass flow through stomatal pores, following the protocol to which was referred in the material and methods-section. To visualize the indicator’s localization after apoplast loading, CLSM imaging was carried out. Confocal imaging (Figure 1) revealed that the Pt-GFP could easily be loaded into the apoplast following the protocol described by Geilfus and Mühling [34]. Moreover, images proved that Pt-GFP had not unintentionally entered the symplast at 2–4 minutes after loading, as otherwise signals would be detectable from the cells. It is very likely that the size of the Pt-GFP that is approximately 105 kDa in its native form [1] ensured that it did not access the symplast by crossing the plasma lemma from the apoplast. Images in Figure 2 demonstrated that in longer periods of time in which experiments are conducted, e.g. 2.5 hours after loading, the Pt-GFP still maintained to be exclusively apoplastically located. Moreover, it can be seen that the apoplast is not flooded (and thus not anoxic) during measurements and that Pt-GFP behaves like Oregon green because it is attached outside of the palisade cells as it was previously observed for the fluorescent dye ([37], Figure number eight therein).

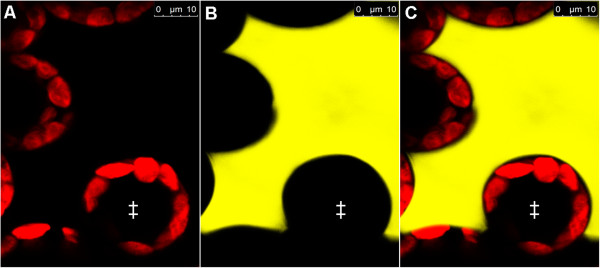

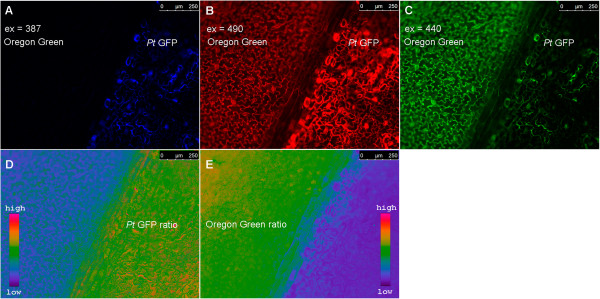

Figure 1.

Apoplastic distribution of the Pt -GFP in a Vicia faba leaf infiltrated 2–4 minutes prior image acquisition. Pt GFP is exclusively located in the apoplast. Confocal image in (A) shows adaxial view on palisade cell chloroplasts (exited at 633 nm; pseudo-red). Image in (B) shows same detail with Pt-GFP (excited at 488 nm; pseudo-yellow). (C) Overlay of (A) and (B) demonstrates that the Pt GFP is only located in the apoplast. No Pt GFP signal is emitted from between the chloroplasts, indicating that the Pt-GFP did not enter the cytosol. Moreover, the inside of the palisade cells remained black, proving that Pt-GFP did not enter the vacuole or other symplastic organelles, as otherwise signals would be detectable from the cells. Symplastic Pt GFP location was negated in several leaves derived from different plants. ‡, palisade cells.

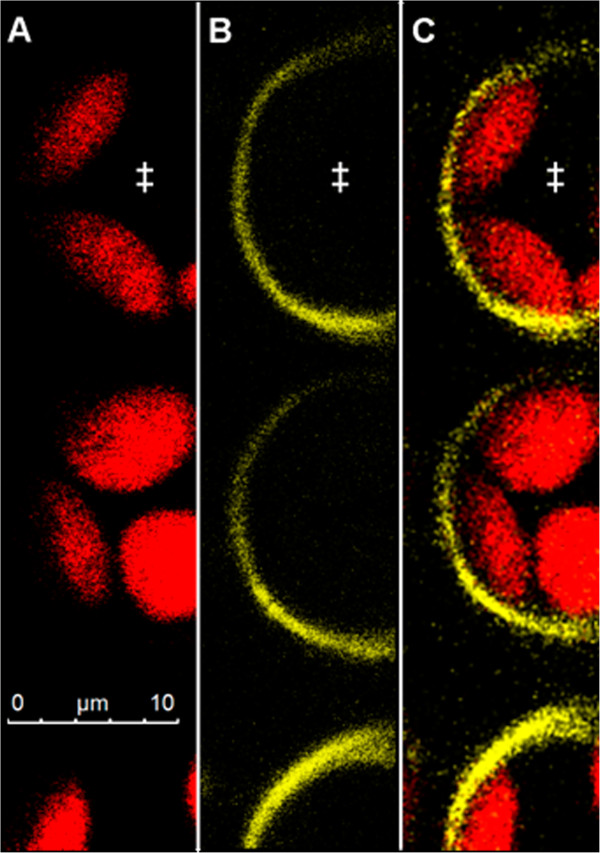

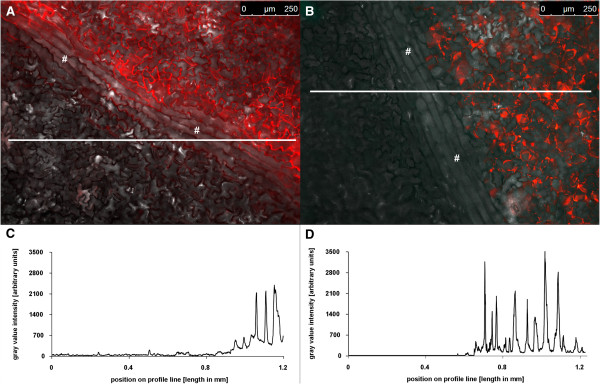

Figure 2.

Apoplastic distribution of the Pt -GFP in a Vicia faba leaf infiltrated 2.5 h prior image acquisition. Pt GFP is exclusively located in the apoplast. Confocal image in (A) shows adaxial view on palisade cell chloroplasts (exited at 633 nm; pseudo-red). Image in (B) shows same detail with Pt-GFP (excited at 488 nm; pseudo-yellow). (C) Overlay of (A) and (B) verifies the apoplastic distribution of the Pt-GFP that is attached outside of the palisade cells and, by this means, outlines the cell boundaries at 2.5 hours after loading. No Pt-GFP signal is emitted from between the chloroplasts, proofing that no Pt-GFP had entered the cytosol. Symplastic Pt GFP location was negated in several leaves derived from different plants. ‡, palisade cells.

Background and photostability

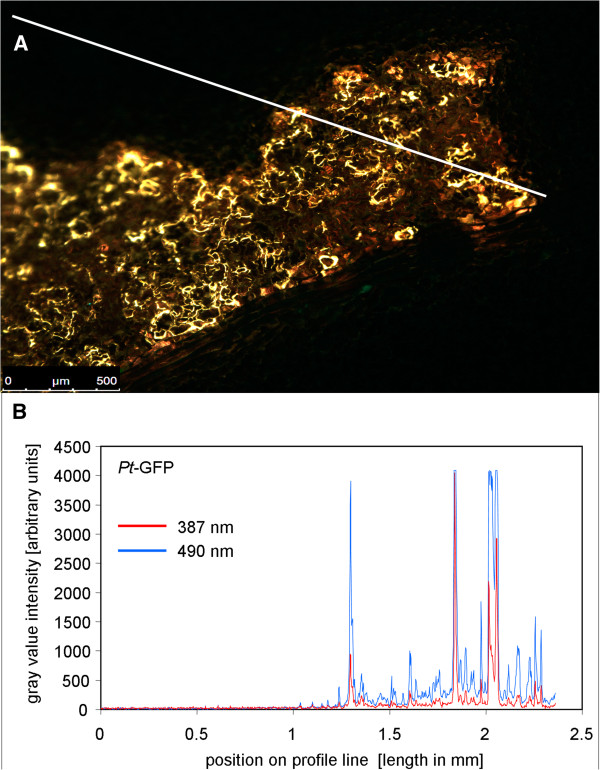

In planta measurements of apoplastic ion dynamics using microscopy-based ratio analysis require a signal-to-background ratio that is large enough to coherently reflect changes in the analyte concentration in the natural environment of the specimen. Background is all the light in the optical system that is not specifically emitted from the pH sensors and, if not considered, might introduce errors in quantitation. Background signals sum up from autofluorescence coming from the measuring devices (i.e., lens elements), the specimen (i.e., chloroplasts or cell wall compounds such as oxidized phenols), the shot background associated with sampling of the signal [32, 51], and the avoidable background arising from residual light in the laboratory (i.e., computer LEDs, monitor screens). In order to evaluate whether the signal-to-background ratio of the Pt-GFP is large enough for ratio analysis, the specimen without the dye was illuminated (background signal intensity) and was compared with the specimen plus dye (signal intensity). In result, only negligible background was detectable (Figure 3; less than 1‰ of the weakest fluorescence signals). The emission signal stood out clearly from the background. This test revealed that the emitted analyte signal was strong enough to allow ratiometric analysis.

Figure 3.

Pt -GFP emission signals are markedly higher than unspecific background signals. (A) Overlay of ex 490 nm (pseudo-green) and ex 387 nm (pseudo-blue) fluorescence images shows adaxial leaf apoplast that was partially loaded with the Pt-GFP. Under illumination, dye-loaded areas appear yellowish because pseudo-green and pseudo-blue are mixed within the overlay. Areas that were not loaded with the pH reporter protein appear black when illuminated and serve to compare the amount of unspecific signals (background) to signals that are specifically emitted from the proteins. For this comparison, the intensity of grey values was chosen as a measure for signal intensity. A profile of the intensity values was taken from the white line in (A) and is presented in (B). Profiles are displayed for both fluorescence excitation channels (F 490 and F 387). Only negligible signals were emitted from the area without dye and signals were much higher in the dye-loaded areas. Twelve separate images captured from different plants proved the low background intensity.

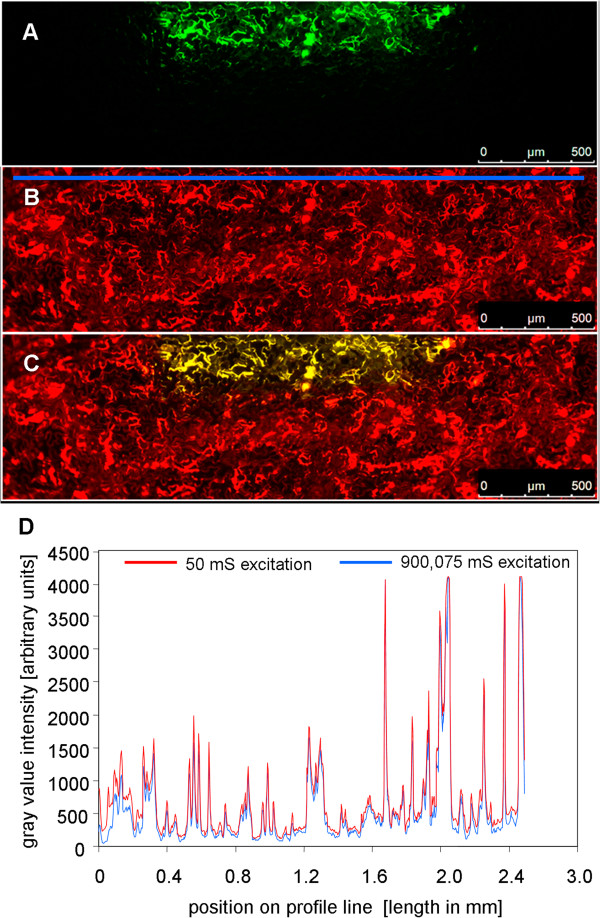

Besides a large signal-to-background ratio, the Pt-GFP needs to have a high photostability allowing to record pH dynamics over a period of several hours without (photo-) bleaching. In order to test whether Pt-GFP was prone to bleaching, the leaf apoplast was loaded with Pt-GFP proteins and continuously excited by 490 nm illumination over a period of 15 min. Subsequently, signal emission intensity was compared between bleached and non-bleached areas. This comparison revealed that no dye-bleaching had occurred to a relevant extent after 15 min of continuous illumination (Figure 4), which is satisfactory because in the present work leaves were illuminated about approximately 4000 ms in maximum. Pt-GFP was extremely photostable under continuous F490-light exposure (same was true for the F387-light channels; data not shown). This means that Pt-GFP is suitable for hours of pH recording in the apoplast of intact plants.

Figure 4.

Pt -GFP is photostable. (A) The leaf apoplast of Vicia faba was loaded with Pt-GFP. To test whether Pt-GFP is prone to bleaching, a selected area (pseudo-green) was designated to be continuously excited by 490 nm illumination over a period of 15 min (=900,000 ms). The outer edges of the specimen were protected against continuous illumination by foreclosing the field diaphragm (non-bleached are appears black). Prior bleaching was started, initial signal intensity of the specimen was documented (image not shown). (B) After 900,000 ms continuous excitation, the field diaphragm was opened for collecting an image at ex 490 nm (exposure time was 25 mS). The image is presented in pseudo-red and contains the part of the specimen that was continuously illuminated (in total 3*25 ms illumination from three image acquisitions plus 900,000 ms from bleaching treatment) plus the area of the specimen that was not bleached (exposed in total to 2*25 ms illumination from two acquisitions). (C) Merged overlay of (A) and (B). The yellow area (mixing pseudo-red and pseudo-green yields orange) represents the part that was continuously exposed to light treatment (in total 900,075 ms) and, thus, contains the possibly bleached proteins. Pseudo-red area represents the non-bleached part of the leaf with only 50 ms illumination in total (due to image acquisition cycles). Image (B) was used to create a profile of the emission intensity values from the area tagged by the blue line as a measure for the photostability. This line covers the bleached and non-bleached areas. The intensity values are presented in (D). A comparison of the intensity values derived from the bleached and non-bleached areas revealed that no significant bleaching occurred after 15 min of continuous illumination. Eight separate bleaching experiments proved photostability of Pt-GFP.

Pt-GFP as leaf apoplastic pH indicator

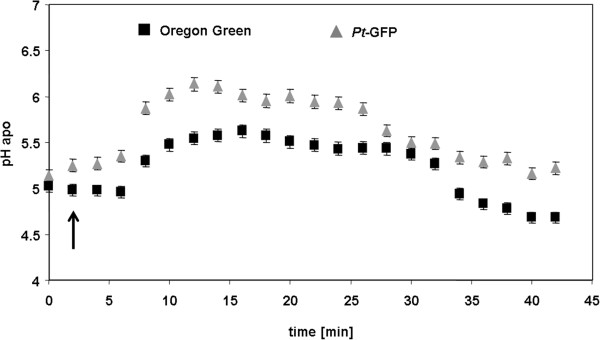

The suitability and responsiveness of apoplastically loaded Pt-GFP to pH changes was evaluated by a comparison to the established fluorescent pH indicator Oregon Green 488-dextran. In order to enable a proper comparability, measurements were conducted simultaneously side by side within the apoplast of the same field bean leaf. For this purpose, the Pt-GFP was loaded adjacent to a region loaded with Oregon Green (Figure 5A-C). The leaf veins clearly separated the GFP proteins from the dye and thus prevented the mixture of both H+-indicators (Figure 6). Thereby, leaf regions loaded with different indicators could be monitored within a single image frame and ratios were calculated according to the optimal wavelength of the respective indicator (Figure 5D-E). Following this loading strategy, the dynamics of two different ions/analytes could be visualized simultaneously in the identical leaf and in planta by “three-channel ratio imaging”. For the sake of comparison, pH changes in the leaf apoplast were specifically induced in a controlled manner by adding chloride into the nutrient solution harbouring the roots. This was done because chloride is carried from the roots to the shoot where it probably primes a systemic transient alkalinization in the leaf apoplast [21, 34]. As visualized by the Oregon Green dye, the addition of 50 mM Cl− via L-cysteinium chloride into the nutrient solution resulted in the expected transient leaf apoplastic alkalinization (Figure 7, black kinetic) that might reflect the action of a Cl−/nH+ symporter. A chloride symport across the PM [52–54] possibly results in a decrease of the leaf apoplastic [H+] caused by the co-transfer of protons together with chloride anions from the apoplast into the cytosol. However, the Pt-GFP ratios did not reflect this alkalinization from pH 4.3 to 5.0 that was indicated by the peak in the Oregon Green ratios (Figure 7, grey kinetic). It seems that the apoplastic pH in field bean leaves was below the range of best responsiveness for the engineered Pt-GFP which ranges from approx. 4.0 to 8.0 as measured by Schulte et al. [1] in vitro with a fluorescence spectrometer and organic buffers adjusted to the desired pH. This raises the question as to whether Pt-GFP is still functional and sensitive to high proton concentrations when used in vivo. In order to conduct an in planta calibration with the aim to test whether the Pt-GFP reacts in vivo on pH increments from pH 4.5 to 5.0, we buffered the V. faba apoplast to pH values ranging from 4.5 to 10.5 in increments of 0.5 pH units. It turned out that a pH below 5 can not be measured in vivo with the Pt-GFP (Figure 8), finally explaining the discrepancies in the comparative measurement presented in Figure 7. Based on the in vivo calibration, only pH changes ranging from values > 5 to 8 can be monitored.

Figure 5.

Principle of ratiometric analysis using two pH indicators within a single image frame. Fluorescence images shows adaxial view of Vicia faba leaf as excited at (A) F 387, (B) F 490 and (C) F 440. Leaf apoplast as loaded with the pH-indicator protein Pt-GFP (right of leaf vein) and the pH-indicator dye Oregon Green-dextran 488 (left of leaf vein). Images were captured approximately 3 hours after loading. The fluorescence ratios (D) F 490/F 387 (Pt-GFP) and (E) F 490/F 440 (Oregon Green 488-dextran) were obtained as a measurement of pH. Emission was collected at 510/84 for both Pt-GFP channels and 535/25 for both OG channels. For this reason, the F 490 channel was captured two times, once with emission 510/84, then with emission 535/25 (only the 535/25 emission image is shown in this figure). The ratios were coded by hue on a spectral colour scale ranging from purple (no signal) to blue (lowest signal) to pink (highest signal). Following this new loading strategy, leaf regions loaded with different indicators could be monitored and ratios were calculated according to the optimal wavelength of the respective indicator.

Figure 6.

Leaf vein as a structural barrier that separates apoplastically located dyes. Adaxial leaf apoplast partially loaded with (A) Oregon Green 488-dextran or with (B) Pt-GFP. Overlay of pseudo-red fluorescence image at F490 and corresponding bright field image captured approximately 3 hours after loading. Dye-loaded areas in (A) and (B) appear red. Areas that were not loaded with the fluorescent pH reporter appear grey when illuminated and serve as a suitable area to compare the amount of unspecific signals (background) to specific signals being emitted from the pH reporters. For this, the intensity of grey values was chosen as a measure for emitted signal intensity. A profile of the intensity values was taken from the white line in (A) and is presented in (C). The same was done for the Pt-GFP: The intensity values were taken from the white line in (B) and are presented in (D). Only negligible signals were emitted from the areas without pH indicator that were separated by the leaf vein from the loaded apoplast. Signals were markedly higher in the dye-loaded areas. #, leaf vein. Results were confirmed by 10 replicates captured from different plants.

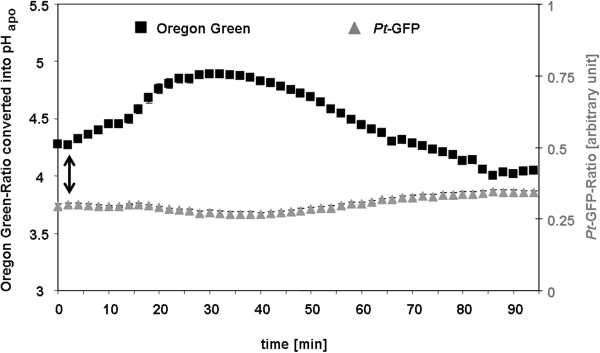

Figure 7.

Unsuitability of Pt -GFP in the acid leaf apoplast of Vicia faba . Comparison between the responsiveness of the pH indicator protein Pt-GFP (grey) and the pH indicator dye Oregon Green (black) to apoplastic pH changes as induced by the addition of 50 mM Cl− via L-cysteinium chloride to the roots of Vicia faba. Time point of chloride addition is indicated by the arrow. pH, as quantified at the adaxial face of Vicia faba leaves is plotted over time. Fluorescence ratio data obtained by Pt-GFP were below the linear range of the in vivo pH calibration and, therefore, could not be converted into pH data. Leaf apoplastic pH quantification was averaged (n = 6 ROIs per ratio image and time point; mean ± SE of ROIs). Representative kinetics of eight equivalent recordings of plants gained from 8 independent experiments.

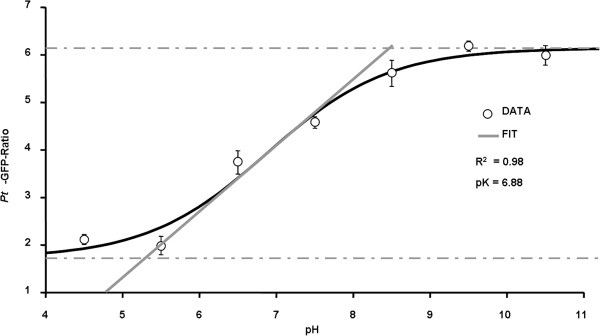

Figure 8.

In vivo calibration of Pt -GFP fluorescence ratio (F 490 /F 387 ). The Boltzmann fit was chosen for fitting sigmoidal curves to calibration ratio data. Fitting resulted in an optimal dynamic range for pH measurements between 5.3 and 8.4. In vivo calibration was conducted on six different plants, each biological replicate was technically replicated. Data are mean of n = 6 ± SE.

Nitrate nutrition alkalizes the leaf apoplast of Vicia fabaL

In a next experiment, the leaf apoplastic pH was alkalized by increasing the nitrate concentration in the nutrient solution from 4 mM up to 15 mM nitrogen (Figure 9). This nitrogen form-related nutrition increased the permanent apoplastic pH from approx. 4.5 up to approx. 5.0 (compare initial pH in Figures 7 and 9). In this way, the leaf apoplastic pH was lifted to the range of best responsiveness for Pt-GFP. The subsequent addition of 20 mM Cl− via L-cysteinium chloride into the nutrient solution resulted in the expected transient apoplastic alkalinization as reflected by the Oregon Green fluorescent dye (Figure 9, black kinetik). This transient alkalinization was also indicated by the Pt-GFP (Figure 9, grey kinetik). However, the absolute pH values measured with Oregon Green and Pt-GFP differed at the maximum peak height. It is possible that e.g. the cell wall did somehow modify the responsiveness of one of the dye system to pH. Another explanation could be that the indicators are localized in different regions of the apoplast were slightly different pH values prevail [20, 21]. Nevertheless, this does not detract from the interpretation of the effects of Cl−-treatment on leaf apoplastic pH because both indicators uniformly recorded the chloride-induced transient leaf apoplastic alkalinization.

Figure 9.

Nitrate nutrition alkalized the leaf apoplast into Pt -GFP’s range of responsiveness. Comparison between the responsiveness of Pt-GFP (grey) and Oregon Green (black) to apoplastic pH changes as induced by the addition of 25 mM Cl− via L-cysteinium chloride to the roots of Vicia faba. Time point of chloride addition is indicated by the arrow. Plants were cultivated with 15 mM nitrate in the nutrient solution given as Ca(NO3)2. pH as quantified at the adaxial face of Vicia faba leaves is plotted over time. Leaf apoplastic pH was averaged (n = 6 ROIs per ratio image and time point; mean ± SE of ROIs). Representative kinetics of six equivalent recordings of plants gained from independent experiments (n = 6 biological replicates).

The experiments presented in Figures 7 and 9 demonstrated that under conditions of 4 mM nitrate fertilization the leaf apoplastic pH was too acidic, so that the Pt-GFP did not act in a range of good responsiveness, possibly due to a fluorescence quench at all wavelengths that caused irreversible conformational changes due to too low pH [1]. Increasing nitrate concentration in the nutrient solution of the beans and the associated alkalinization of the extra cellular space that is partially known to be caused by a nitrate cotransport with H+ across the PM [13, 14] increased the leaf apoplastic pH to a range that can be monitored with the Pt-GFP.

Pt-GFP as apoplastic pH indicator in Avena sativaL.

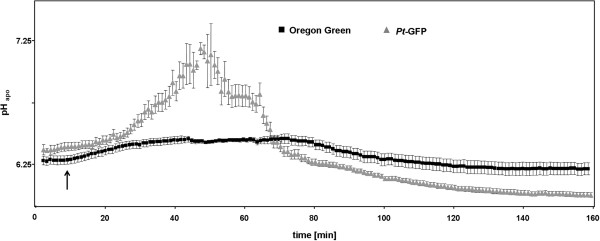

Once oat (Avena sativa L.) with its less acidic apoplast [35, 55] was chosen for analyzing the formation of the NaCl-induced leaf apoplastic pH peaks, the acidotropic [56] Oregon Green 488 dye seemed to be the wrong choice: Regardless of the fact that the leaf apoplastic pH response was challenged by the addition of 25 mM Cl− given via L-cysteinium chloride into the nutrient solution, the expected transient alkalinization was not reflected by the Oregon Green ratio (Figure 10). It appears that the Oregon Green ratios has reached a ‘plateau phase’ that cannot be exceeded. In contrast, the Pt-GFP ratio clearly reflected the transient alkalinization by peaking from an initial pH of approx. 6.25 up to a neutral pH of almost 7.25 (Figure 10). This clearly showed that knowledge about the prevailing pH is mandatorily necessary for choosing the suitable pH indicator. If, for example, Oregon Green would be selected as pH indicator under near neutral conditions, an alkalizing response of the biological system to the stimulus could not be detected and would be misinterpreted as being absent. The experiment has shown that the chloride induced transient alkalinizations which are thought to play a role in the root-to-shoot communication of salt stress [19] are also present in the leaf apoplast of oat. This new finding delivers further indication that the salt-stress induced pH response may occur universally in different plant species.

Figure 10.

Near neutral leaf apoplast in Avena sativa requires Pt -GFP for detecting alkalizing effects. Leaf apoplastic pH response of Avena sativa as provoked by the addition of 25 mM Cl− via L-cysteinium chloride into the nutrient solution. Time point of chloride addition as indicated by the arrow. pH, as quantified at the adaxial leaf face is plotted over time. Pt-GFP, grey curve; Oregon Green, black curve. Plants were cultivated with 15 mM nitrate in the nutrient solution given as Ca(NO3)2. Leaf apoplastic pH was averaged (n = 6 ROIs per ratio image and time point; mean ± SE of ROIs). Representative kinetics of eight equivalent recordings of plants gained from independent experiments (n = biological replicates).

Bypassing the cellular secretion pathway

The expression of genetically encoded pH sensors in plants that are targeted to the apoplast is accompanied by the problem that the proteins have to pass the cellular secretion pathway. From here they may also emit fluorescence. These signals from the cytosol, the ER or from Golgi vesicles average with signals from the acid apoplast and may thus lead to incorrect apoplastic pH values [1]. Since there is a pronounced proton gradient between cytosol and apoplast, this problem cannot be neglected. The presented approach of infiltrating bacterially produced and purified pH-sensitive Pt-GFP proteins through the stomatal pores into the leaf apoplast bypasses this problem. Moreover, the new approach describes how to use fluorescent reporter proteins for the measurement of leaf apoplastic ion relations in plants that are not readily transformable such as some of the agricultural relevant crop plants. In the light of the increasing availability of self-expressed biosensors [12, 36, 46, 57–64], the presented approach should be seen as example and could also be applied to other genetically encoded sensor proteins or synthetic dyes for spatiotemporal mapping of ion relationships in the intact apoplast.

Concluding remarks

In summary, confocal laser scanning imaging showed that the tested loading technique is suitable for inserting bacterially produced Pt-GFPs into the apoplast of intact plants and negates the unintended presence of the Pt-GFP proteins in the symplast. The emission signal stood out clearly from the background and the Pt-GFP was characterized by a high photostability allowing ratiometric dual-excitation measurements over hours. Pt-GFP appeared to be a very good choice for the in planta quantification of leaf apoplastic pH-dynamics in plants that exhibit a relative neutral apoplastic pH. By using this approach, it was found that chloride-induced alkalinizations are not only formed in field beans [20] but also in oat. A strategy is presented that explains how to use bacterially expressed biosensors for the ratiometric in planta quantification of apoplastic ion kinetics in real time.

Abbreviations

- CLSM

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- Pt

Ptilosarcus gurneyi

- PM

Plasma membrane

- ROI

Region of interest

- OG

Oregon Green.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Christoph-Martin Geilfus, Email: cmgeilfus@plantnutrition.uni-kiel.de.

Karl H Mühling, Email: khmuehling@plantnutrition.uni-kiel.de.

Hartmut Kaiser, Email: hkaiser@bot.uni-kiel.de.

Christoph Plieth, Email: cplieth@zbm.uni-kiel.de.

References

- 1.Schulte A, Lorenzen I, Bötcher M, Plieth C. A novel fluorescent pH probe for expression in plants. Plant Methods. 2006;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monshausen GB, Miller ND, Murphy AS, Gilroy S. Dynamics of auxin-dependent Ca2+ and pH signalling in root growth revealed by integrating high-resolution imaging with automated computer vision-based analysis. Plant J. 2011;65:309–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders D. Generalized kinetic analysis of ion driven cotransport systems: II. random ligand binding as a simple explanation for non-Michaelis kinetics. J Membr Biol. 1986;90:67–87. doi: 10.1007/BF01869687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemoine R, Delrot S. Proton-motive-force-driven sucrose uptake in sugar beet plasma membrane vesicles. FEBS Lett. 1989;249:129. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80030-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush DR. Proton-coupled sugar and amino acid transporters in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1993;44:513–542. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.44.060193.002501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marschner H. Mineral nutrition of higher plants. 2. London: Academic; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maathuis FJ, Sanders D. Plasma membrane transport in context – making sense out of complexity. Cur Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:236–243. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Shimon A, Shalev DE, Niv MY. Protonation States in molecular dynamics simulations of peptide folding and binding. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(23):4173–4181. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319230003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartung W. Die intrazelluläre Verteilung von Phytohormonen in Pflanzenzellen. Hahenheimer Arbeiten. 1983;129:64–80. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartung W, Solvik S. Physicochemical properties of plant growth regulators and plant tissues determine their distribution and redistribution: stomatal regulation by abscisic acid in leaves. New Phytol. 1991;119:361–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1991.tb00036.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daeter W, Slovik S, Hartung W. The pH-gradients in the root system and the abscisic acid concentration in xylem and apoplastic saps. Philos T Roy Soc B. 1993;341:49–56. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1993.0090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swanson SJ, Choi WG, Chanoca A, Gilroy S. In vivo imaging of Ca2+, pH, and reactive oxygen species using fluorescent probes in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2011;62:273–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerendás J, Ratcliffe RG. Intracellular pH regulation in maize root tips exposed to ammonium at high external pH. J Exp Bot. 2000;51(343):207–219. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.343.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mühling KH, Läuchli A. Influence of chemical form and concentration of nitrogen on apoplastic pH of leaves. J Plant Nutr. 2001;24:399–411. doi: 10.1081/PLN-100104968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Volkenburgh E, Boyer JS. Inhibitory effects of water deficit on maize leaf elongation. Plant Physiol. 1985;77:190–194. doi: 10.1104/pp.77.1.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartung W, Radin JW, Hendrix DL. Abscisic acid movement into the apoplastic solution of water-stressed cotton leaves: role of apoplastic pH. Plant Physiol. 1988;86:908–913. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.3.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson S, Davies WJ. Xylem sap pH increase: a drought signal received at the apoplastic face of the guard cell that involves the suppression of saturable abscisic acid uptake by the epidermal symplast. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:559–573. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felle HH, Hermann A, Hückelhoven R, Kogel KH. Root-to-shoot signalling: apoplastic alkalinization, a general stress response and defence factor in barley (Hordeum vulgare) Protoplasma. 2005;227:17–24. doi: 10.1007/s00709-005-0131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felle HH. pH regulation in anoxic plants. Ann Bot. 2005;96:519–532. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geilfus CM, Mühling KH. Transient alkalinization in the leaf apoplast of Viciafaba L. depends on NaCl stress intensity: an in situ ratio imaging study. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35(3):578–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geilfus CM, Mühling KH. Microscopic and macroscopic monitoring of adaxial– abaxial pH gradients in the leaf apoplast of Vicia faba L. as primed by NaCl stress at the roots. Plant Sci. 2014;223:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felle HH, Herrmann A, Hanstein S, Hückelhoven R, Kogel KH. Apoplastic pH signalling in barley leaves attacked by the powdery mildew fungus Blumeria graminis f.sp. hordei. Mol Plant Microbe In. 2004;17:118–123. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schäfer P, Pfiffi S, Voll LM, Zajic D, Chandler PM, Waller F, Scholz U, Pons- Kühnemann J, Sonnewald S, Sonnewald U, Kogel KH. Manipulation of plant innate immunity and gibberellin as factor of compatibility in the mutualistic association of barley roots with Piriformospora indica. Plant J. 2009;59:461–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hager A, Menzel H, Krauss A. Versuche und Hypothese zur Primärwirkung des Auxins beim Streckenwachstum. Planta. 1971;100:47–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00386886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raven JA, Farquhar GD. Leaf apoplast pH estimation in Phaseolus vulgaris. In: Dainty J, De Michelis MI, Marre E, Rasi-Caldogno F, editors. Plant membrane transport: the current position. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1989. pp. 607–610. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ullrich WR. Transport of nitrate and ammonium through plant membranes. In: Mengel K, Pilbeam DJ, editors. Nitrogen Metabolism in Plants. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mühling KH, Plieth C, Hansen UP, Sattelmacher B. Apoplastic pH of intact leaves of Vicia faba as influenced by light. J Exp Bot. 1995;16:377–382. doi: 10.1093/jxb/46.4.377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mühling KH, Läuchli A. Light-induced pH and K + changes in the apoplast of intact leaves. Planta. 2000;212:9–15. doi: 10.1007/s004250000374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monshausen GB, Bibikova TN, Messerli MA, Shi C, Gilroy S. Oscillations in extracellular pH and reactive oxygen species modulate tip growth of Arabidopsis root hairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(52):20996–21001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708586104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toyota M, Gilroy S. Gravitropism and mechanical signaling in plants. Am J Bot. 2012;100(1):111–125. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1200408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fricker MD, Plieth C, Knight H, Blancaflor E, Knight MR, White NS, Gilroy S. Fluorescent and luminescent techniques to probe ion activities in living plant cells. In: Mason WT, editor. Fluorescent and luminescent probes. London: Academic; 1999. pp. 569–596. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fricker MD, Parsons A, Tlalka M, Blancaflor E, Gilroy S, Meyer A, Plieth C. Fluorescent probes for living plant cells. In: Hawes C, Satiat- Jeunemaitre B, editors. Plant Cell Biology: A Practical Approach. 2. Oxford: University Press; 2001. pp. 35–84. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilroy S. Fluorescence microscopy of living plant cells. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geilfus CM, Mühling KH. Real-time imaging of leaf apoplastic pH dynamics in response to NaCl stress. Front Plant Sci. 2011;2:13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grignon C, Sentenac H. pH and ionic conditions in the apoplast. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.42.060191.000535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao D, Trewavas AJT, Knight MR, Sattelmacher B, Plieth C. Selfreporting Arabidopsis thaliana expressing pH- and [Ca 2+]-indicators unveil ion dynamics in the cytoplasm and in the apoplast under abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:898–908. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geilfus CM, Mühling KH. Ratiometric monitoring of transient apoplastic alkalinizations in the leaf apoplast of living Vicia faba plants: chloride primes and PM-H+-ATPase shapes NaCl-induced systemic alkalinizations. New Phytol. 2013;197(4):1117–1129. doi: 10.1111/nph.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffmann B, Kosegarten H. FITC-dextran for measuring apoplast pH and apoplastic pH gradients between various cell types in sunflower leaves. Physiol Plant. 1995;95:327–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1995.tb00846.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahmoudi AR, Shaban E, Ghods R, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Emami S, Rabbani H, Zarnani AH, Mahmoudian J. Comparison of photostability and photobleaching properties of FITC- and dylight 488 conjugated Herceptin. Int J Green Nanotech. 2011;3(3):264–270. doi: 10.1080/19430892.2011.633480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han JY, Burgess K. Fluorescent Indicators for Intracellular pH. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2709–2728. doi: 10.1021/cr900249z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen J, Zeng Y, Zhuang X, Sun L, Yao X, Pimpl P, Jiang L. Mol Plant. 2013. Organelle pH in the Arabidopsis endomembrane system. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geilfus CM, Zörb C, Neuhaus C, Hansen T, Lüthen H, Mühling KH. J Plant Growth Regul. 2011. Differential transcript expression of wall-loosening candidates in leaves of maize cultivars differing in salt resistance. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zörb C, Geilfus CM, Mühling KH, Ludwig-Müller J. The influence of salt stress on ABA and auxin concentrations in two maize cultivars differing in salt resistance. J Plant Physiol. 2013;170(2):220–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bibikova TN, Jacob T, Dahse I, Gilroy S. Localized changes in apoplastic and cytoplasmic pH are associated with root hair development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 1998;125:2925–2934. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Felle HH. pH: signal and messenger in plant cells. Plant Biol. 2001;3:577–591. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-19372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi WG, Swanson SJ, Gilroy S. High-resolution imaging of Ca2+, redox status, ROS and pH using GFP biosensors. Plant J. 2012;70:118–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bacon MA, Wilkinson S, Davies WJ. pH-regulated leaf cell expansion in droughted plants is abscisic acid dependent. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1507–1511. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilkinson S. pH as a stress signal. Plant Growth Regul. 1999;29:89–99. doi: 10.1023/A:1006203715640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:50–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monshausen GB. Visualizing Ca2+ signatures in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15(6):677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fricker MD, Errington RJ, Wood JL, Tlalka M, May M, White NS. Quantitative confocal fluorescence measurements in living tissues. In: Van Duijn B, Wiltnik A, editors. Signal Transduction - Single Cell Research. Heidelberg: Springer- Verlag; 1997. pp. 569–596. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanders D, Hansen UP. Mechanism of Cl − transport at the plasma membrane of Chara corallina. part II. transinhibition and the determination of H+/Cl − binding order from a reaction kinetic model. J Membrane Biol. 1981;58:139–153. doi: 10.1007/BF01870976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Felle HH. The H+/CI− -symporter in root-hair cells of Sinapis alba. an electrophysiological study using ion-selective microelectrodes. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1131–1136. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.3.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lorenzen I, Aberle T, Plieth C. Salt stress-induced chloride flux: a study using transgenic Arabidopsis expressing a fluorescent anion probe. Plant J. 2004;38:539–544. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-7412.2004.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rayle DL. Auxin-induced hydrogen-ion secretion in Avena coleoptiles and its implications. Planta. 1973;114(1):63–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00390285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DiCiccio JE, Steinberg BE. Lysosomal pH and analysis of the counter ion pathways that support acidification. J Gen Physiol. 2011;137:385–390. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miesenböck G, de Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent protein. Nature. 1998;394:192–195. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanson GT, McAnaney TB, Park ES, Rendell MEP, Yarbrough DK, Chu SY, Xi LX, Boxer SG, Montrose MH, Remington SJ. Green fluorescent protein variants as ratiometric dual emission pH sensors. 1. structural characterization and preliminary application. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15477–15488. doi: 10.1021/bi026609p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bizzarri R, Arcangeli C, Arosio D, Ricci F, Faraci P, Cardarelli F, Beltram F. Development of a novel GFP-based ratiometric excitation and emission pH indicator for intracellular studies. Biophys J. 2006;90:3300–3314. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.074708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meyer AJ, Brach T, Marty L, Kreye S, Rouhier N, Jacquot JP, Hell R. Redox- sensitive GFP in Arabidopsis thaliana is a quantitative biosensor for the redox potential of the cellular glutathione redox buffer. Plant J. 2007;52:973–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Young B, Wightman R, Blanvillain R, Purcel SB, Gallois P. pH-sensitivity of YFP provides an intracellular indicator of programmed cell death. Plant Methods. 2010;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gjetting KS, Ytting K, Karkov C, Schulz A, Fuglsang AT. Live imaging of intra- and extracellular pH in plants using pHusion, a novel genetically encoded biosensor. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(8):3207–3218. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gjetting KS, Schulz A, Fuglsang AT. Perspectives for using genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:234. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martinière A, Desbrosses G, Sentenac H, Paris N. Development and properties of genetically encoded pH sensors in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:523. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]