Abstract

The authors present a modular set of patient classification systems designed for medical rehabilitation that predict resource use and outcomes for clinically similar groups of individuals. The systems, based on the Functional Independence Measure, are referred to as Function-Related Groups (FIM-FRGs). Using data from 23,637 lower extremity fracture patients from 458 inpatient medical rehabilitation facilities, 1995 benchmarks are provided and illustrated for length of stay, functional outcome, and discharge to home and skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). The FIM-FRG modules may be used in parallel to study interactions between resource use and quality and could ultimately yield an integrated strategy for payment and outcomes measurement. This could position the rehabilitation community to take a pioneering role in the application of outcomes-based clinical indicators.

Introduction

Category one medical rehabilitation, which generally occurs in distinct-part units in larger hospitals and in freestanding rehabilitation hospitals, is intended to minimize impairment, disability, and handicap in people who become disabled because of illness or injury. It involves a 24-hour coordinated program of integrated medical and rehabilitation services for people who are expected to return to the community with or without support. To be eligible for this high level of service intensity, by definition, patients must need, be able to tolerate, and receive at least 3 hours of therapy daily and must be at high risk of medical instability (Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities, 1997). Because it is hospital-level, category one rehabilitation is referred to as inpatient rehabilitation to distinguish it from subacute therapy services generally provided in lower intensity postacute care settings such as SNFs.

Medicare's prospective payment system (PPS) could not be applied to inpatient rehabilitation because the diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) failed to predict resource requirements accurately in this setting (Hosek et al., 1986). Thus, distinct-part rehabilitation units and hospitals continue to be paid according to the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (TEFRA, Public Law 97-248) on the basis of cost per case, limited by a hospital-specific target amount per discharge. The amount is calculated as the cost per discharge in a base year, adjusted annually by an update factor. During testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Health, April 10, 1997, concerns were expressed about the TEFRA payment system.1

TEFRA appears to have failed to curb rising expenditures. Since implementation of the PPS in acute care hospitals, increasing numbers of patients are being discharged to TEFRA facilities. There has been a 28.9-percent increase in the number of Medicare-certified facilities over 6 years (1990-96),2 and Medicare payments to rehabilitation facilities increased from $1.9 billion in 1990 to $3.9 billion in 1994 (Prospective Payment Assessment Commission, 1997). In addition, TEFRA methodology creates incentive for newly established hospitals to inflate base-period costs to establish higher target rates, likely providing unfair advantage to newer hospitals and those with inefficient operations. High-limit facilities receive six or more times the amount allowed per discharge, compared with low-limit facilities (Sutton, DeJong, and Wilkerson, 1996). Disparities in payment may translate into inequities for people with disabilities who need treatment. Because they lack any measure of clinical severity, TEFRA limits bear no relationship to the types of patients actually treated. As Medicare fee-for-service payments become tighter, these inequities in the provision of medical rehabilitation will only increase. The adjustment of payment rates to reflect case-mix differences could, in part, stem such inequities.

The Functional Independence Measure

The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) was developed as part of the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (UDSmr) (Granger et al., 1986; Hamilton et al., 1987; Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, 1995), which was designed specifically as a centralized repository for clinical information on rehabilitation. It compiles information about patient diagnoses, functional status, length of stay (LOS), and social demographics. As of August 1997, the clinicians in 570 facilities in the United States had passed a certifying examination for administering the FIM and were submitting data to the UDSmr. In addition, a growing number of SNFs in this country, along with facilities in several European countries, are submitting data.

The FIM is a standard measure of the type and amount of human assistance required for a person to perform basic life activities. Thirteen national organizations endorsed or supported its development. It contains 18 items, each of which has 7 explicitly defined performance levels (Table 1). The FIM describes two dimensions of disability: one involving physical tasks, referred to as “motor,” and the other involving communication and cognition, referred to as “cognitive” (Linacre et al., 1994). These dimensions, expressed as subscales, have excellent internal consistency, with Chronbach's alpha coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.97, across 20 categories of impairment (Stineman et al., 1996b). FIM scoring also shows excellent agreement between raters. The total intraclass correlation coefficients for the motor and cognitive subscores were 0.96 and 0.91 (Hamilton et al., 1994). The 13-item motor score ranges from 13 to 91, where 13 indicates total dependence in all items and 91 total independence. The cognitive ranges in value from 5 to 35, with 5 specifying total dependence and 35 total independence in the functions.

Table 1. The Functional Independence Measure.

| Items | Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor | No Helper | ||

| A. | Eating | 7. | Complete independence |

| B. | Grooming | 6. | Independent with the use of a device, taking more time, or some safety risk |

| C. | Bathing | ||

| D. | Dressing-Upper Body | ||

| E. | Dressing-Lower Body | Helper | |

| F. | Toileting | 5. | Supervision or prior preparation |

| G. | Bladder Management | 4. | Minimal assistance (with the patient providing three-quarters or more of the combined effort) |

| H. | Bowel Management | ||

| I. | Bed, Chair, Wheelchair Transfer | 3. | Moderate assistance (with the patient providing one-half to less than three-quarters of the combined effort) |

| J. | Toilet Transfer | ||

| K. | Tub or Shower Transfer | ||

| L. | Walking or Wheelchair | Complete Dependence | |

| M. | Stairs | 2. | Maximal assistance (with the patient providing one-quarter to less than one-half of the combined effort) |

| 1. | Total assistance (with the patient providing less than one-quarter of effort) | ||

| Cognitive | |||

| N. | Comprehension | ||

| O. | Expression | ||

| P. | Social Interaction | ||

| Q. | Problem Solving | ||

| R. | Memory | ||

The FIM-Function Related Group Systems

The FIM-FRGs are a family of case-mix measures being developed and validated for inpatient medical rehabilitation. The modular components are intended to classify patients into groups that are clinically meaningful and homogeneous with respect to resource use and functional outcomes. The International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps (World Health Organization, 1980) provides the conceptual foundation for these systems. Each FIM-FRG system classifies patients first by the World Health Organization dimension of impairment and then by level and type of disability, both of which are necessary to adequately explain differences in rehabilitation resource use and outcomes. Impairment describes the primary anatomical defect, disease, or psychological state for which the individual is receiving rehabilitation services. The most recent FIM-FRG versions include 20 impairment categories (Stineman et al., 1997c), which, whenever possible, were designed to be classifiable within the DRG Major Diagnostic Categories to encourage continuity of classification across acute and postacute inpatient services (Stineman, 1997). Disability refers to any resulting restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in a way or range that is considered normal. Severity of disability in the FIM-FRG systems is described by the person's admission performance on the motor- and cognitive-FIM subscales. Certain FRG groups are further subdivided by age. All FIM-FRG modules incorporate the same classifying variables.

FIM-FRG nomenclature includes a prefix abbreviating the parameter being predicted. In the context of this nomenclature, the length-of-stay FRG systems (LOS-FRGs) combine patients expected to have similar lengths of stay (LOS) (Stineman et al., 1994; Stineman et al., 1997c). The discharge-motor FIM-FRGs (DMF-FRGs) combine patients expected to have similar motor-FIM scores at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation (Stineman etal., 1997a). The gain-FRGs identify patients expected to have similar degrees of functional recovery as expressed by the difference between motor-FIM scores at admission and discharge (Stineman et al., 1997b). These three FIM-FRG modules are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Resource Use and Outcomes Used to Develop Functional Independence Measure Function-Related Groups (FIM-FRGs).

| Resource Use | Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | LOS-FRGs1 | DMF-FRGs2 | Gain-FRGs |

| Dependent Variable | Inpatient Length of Stay | Discharge Motor FIM | Motor FIM Gains (Discharge Score - Admission Score) |

| Input Classification Variables |

|

Same as LOS-FRGs | Same as LOS-FRGs |

| When FIM Measures Are Taken | Admission Only | Admission and Discharge | Admission and Discharge |

| Uses | Establish groups of patients expected to require similar lengths of inpatient rehabilitation | Establish groups of patients expected to achieve specific levels of function by discharge from inpatient rehabilitation | Establish groups of patients expected to have similar degrees of functional gain over the course of inpatient rehabilitation |

Length-of-Stay Function-Related Groups.

Discharge-Motor FIM Function-Related Groups.

SOURCE: (Length of stay) Stineman et al. 1994, Stineman et al., 1997c; (Discharge motor FIM) Stineman et al., 1997a; (Gain FRGs) Stineman et al., 1997b.

There are two versions of LOS-FRGs. The first LOS-FRGs (Version 1.1) (Stineman et al., 1994) were developed from 1990 discharges. The second (Version 2.0) (Stineman et al., 1997c) were developed from more than 82,000 records of patients discharged from 252 medical rehabilitation facilities in 1992. The 2.0 system includes 67 FRGs and explains 31.7 percent of the variation in LOS. Charges and LOS for inpatient rehabilitation are substantially correlated (Hosek et al., 1986), justifying the use of LOS in approximating rehabilitation resource use. The association between LOS and total charges was shown to be R = 0.89 at the time of developing the first LOS FRGs (Stineman et al., 1994). Use of LOS was further justified by the 3-hour rule (Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities, 1997), specifying the provision of at least 3 hours of daily therapy. Although average LOS is dropping, the amount of variation in LOS explained over time by the LOS-FRGs appears to be stable. As it stands, this module could be used as a management tool to identify groups of patients expected to have similar LOS. For applications to payment, LOS-FRGs would need to be converted to a cost-based classification system.

The DMF-FRGs (Stineman et al., 1997a) and gain-FRGs (Stineman et al., 1997b) were developed from the same set of records as the LOS-FRGs Version 2.0. The DMF-FRGs system includes 139 groups that explain 63 percent of the variation in patients' motor-FIM discharge scores. The gain-FRGs system includes 74 groups that explain 21 percent of the variation in patients' change in motor FIM. From a mathematical standpoint, the gain- and DMF-FRGs are interchangeable. Because admission FIM is one of the classifying variables, there is an induced correlation making the DMF-FRG R2 higher. The choice of DMF-FRGs over gain-FRGs depends on the analytic objectives. Knowledge about expected functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, as established by the DMF-FRGs, will be important when planning services for groups of people once they leave the hospital setting. Knowledge about risk-adjusted expected functional gains as established by the gain-FRG system will be more compelling when attempting to study changes in status associated with specific rehabilitation services.

The four FRG modules were developed by combining statistical findings with the judgments of a national panel of expert clinicians. Once candidate classifying variables were selected, the FRG groups were defined by recursive partitioning, using classification and regression trees (Breiman et al., 1984), and the numbers of splits were optimized by either the tenfold cross-validation or test-sample methods, depending on the sample size.

In the fall of 1995, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) awarded a contract to Carter and colleagues at the RAND Corporation to evaluate LOS-FRGs Version 1.1 (Stineman et al., 1994) and, if feasible, to develop an FRG-basedbPPS. Carter and colleagues (1997b) concluded that LOS-FRGs are robust, effective predictors of both LOS and Medicare costs and are stable over time, as demonstrated by using FRGs fit on 1990 data to predict 1994 resource use. RAND improved on the original FRGs by adding a binary variable indicating the presence of one or more of a selected set of comorbidities and complications. They also designated a variable to distinguish whether a patient's stay in rehabilitation was interrupted by temporary transfer to an acute hospital service. The explanatory power at the case level of the FRGs with comorbidity and interrupted-stay effects added is approximately equal to the fifth revision of the DRGs and exceeds that of the medical DRGs. RAND's FRG-based PPS follows the general structure of the DRG-based PPS (Carter et al., 1997a). Depending on design, the system would explain 60-65 percent of the variance in costs at the hospital level. Should cost-based-FRGs be used within a PPS structure, then hospitals would be allocated higher payments if they managed a higher-than-usual proportion of patients with certain catastrophic impairments, such as spinal cord injury, or if they treated patients with more severe disabilities.

The Budget Reconciliation Act of 1997 (Public Law 105-33) calls for the implementation of a PPS for inpatient rehabilitation by the year 2000. Here we illustrate how information from the LOS-FRG and outcome FRG modules might be combined to establish an integrated technology for resource-use monitoring and patient-outcomes measurement. This approach will be particularly valuable, should RAND's FRG-based PPS be implemented.

Methods

Data

This study was limited to data from patients discharged in 1995 from distinct-part units and freestanding rehabilitation hospitals. All patients' FIM scores were rated by clinicians at admission to and at discharge from medical rehabilitation. To ensure high quality, only data from the 458 UDSmr facilities whose clinicians had passed FIM credentialing criteria were used. Credentialing involves a written examination that tests clinicians' abilities to code the FIM appropriately. The 20 FIM-FRG impairment categories and the number and proportion of cases in each among the 1995 UDSmr discharges is shown in Table 3. Lower-extremity-fracture patients were chosen to illustrate the integrated monitoring approach because of the large number of discharges (12.6 percent of inpatient UDSmr records from 1995) and because their care is commonly paid through Medicare. A similar approach could easily be established for the other 19 FIM-FRG impairment categories. Lower-extremity-fracture cases were selected based on the same sampling criteria used to originally develop the FIM-FRG systems. These criteria eliminated patients 16 years of age or under, admitted for evaluation only, transferred to a different hospital service, with stays longer than 1 year or shorter than 4 days, and who died during rehabilitation. These criteria were developed to select patients whose rehabilitation stays were typical, as described in earlier publications (Stineman et al., 1994; Stineman et al., 1997c). Out of the 25,501 patients with lower extremity fracture, there were 23,637 (93 percent) who met the sampling criteria.

Table 3. The 20 FIM-FRG Impairment Categories with the Number of Cases and Percent Discharged in 1995 from UDSmr Facilities.

| Impairment Category | Observations | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 187,772 | — |

| Neurological | ||

| Stroke | 55,530 | 29.57 |

| Brain Dysfunction, Non-traumatic | 5,341 | 2,84 |

| Brain Dysfunction, Traumatic | 6,791 | 3.62 |

| Neurological Conditions, Other | 8,006 | 4.26 |

| Guillain-Barreacute; Syndrome | 811 | 0.43 |

| Spinal Cord Injury, Non-traumatic | 5,961 | 3.17 |

| Spinal Cord Injury, Traumatic | 3,625 | 1.93 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Amputation, Lower Extremity | 7,155 | 3.81 |

| Amputation, Other | 555 | 0.30 |

| Arthritis, Osteo | 2,397 | 1.28 |

| Arthritis, Rheumatoid and Other | 1,628 | 0.87 |

| Pain Syndrome | 2,389 | 1.27 |

| Orthopedic: Lower Extremity Fracture | 23,637 | 12.59 |

| Orthopedic: Lower Extremity Joint Replacement | 34,208 | 18.22 |

| Other Orthopedic | 7,229 | 3.85 |

| Other or Combined Organ | ||

| Cardiac | 4,726 | 2.52 |

| Pulmonary | 3,353 | 1.79 |

| Major Multiple Trauma (MMT) | 1,414 | 0.75 |

| MMT with Brain and/or Spine Involvement | 1,332 | 0.71 |

| Other Impairments | 11,684 | 6.23 |

NOTE: UDSmr is Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation.

SOURCE: Stineman, M., University of Pennsylvania, and Granger, C.State University of New York at Buffalo, 1997.

1995 Benchmark Norms

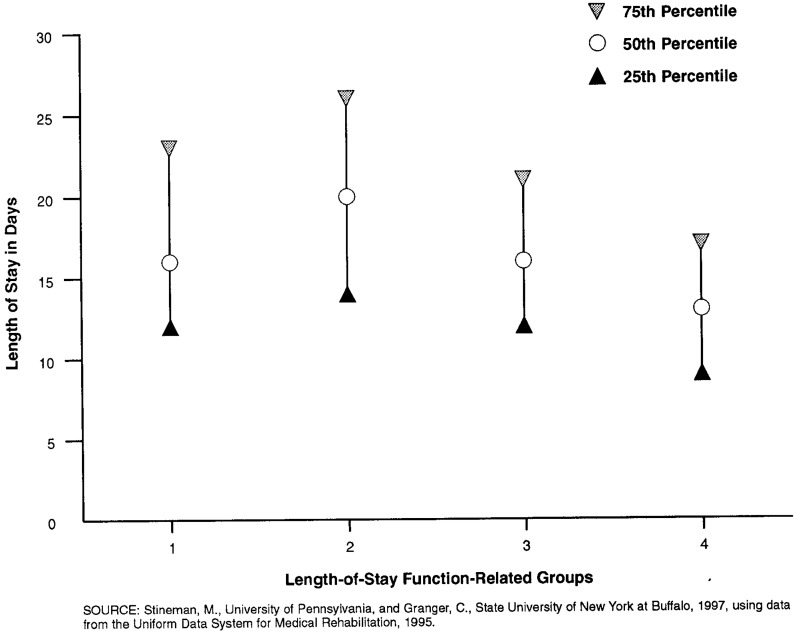

To illustrate benchmark norms, the 23,637 cases were first classified into their appropriate DMF-FRGs and LOS-FRGs, after which the actual 25th-, 50th-, and 75th-percentile motor-FIM discharge scores and LOS for each FRG cluster of patients were obtained. Selection of the 25th and 75th percentiles is arbitrary. Alternatively, narrower or broader ranges could be established. In addition to LOS and functional outcome, disposition norms were determined as the proportion of patients discharged to various settings. These benchmark norms are provided to illustrate the relationships among patient severity, expected LOS, functional outcome, and ultimate discharge destination.

Results

Benchmark Norms

Medicare was the primary source of payment for 84.5 percent of lower-extremity-fracture patients. The sample characteristics are shown in Table 4. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the lower-extremity-fracture LOSFRGs consist of 4 groups, and the DMF-FRGs consist of 18 groups. The gain-FRGs consist of six groups (not shown). Median 1995 LOS, number of cases, and percent in each group are shown in the columns to the right of the LOS-FRG classification tree (Figure 1).The 1995 median discharge motor-FIM scores, number of cases, and percent in each group are shown in the columns to the right of the DMF-FRGs classification tree (Figure 2). The 1995 home and SNF discharge rates are provided for each of the DMF-FRGs (Table 5). The proportions do not add to 100 percent because only the two most frequent disposition locations are provided. A patient is classified into the FIM-FRG modules by one or more of the following: impairment, performance on the motor-FIM upon admission to rehabilitation, performance on the cognitive-FIM upon admission, and age. For example, a man 82 years of age entering rehabilitation following lower extremity fracture with a motor-FIM score of 42 and a cognitive FIM score of 30 would be in LOS-FRG 2 and in DMF-FRG 12. The 1995 median LOS for clinically similar patients in 1995 was 20 days, the median motor-FIM score at discharge was 68 points, and the home-discharge rate was 82.2 percent.

Table 4. The Clinical Characteristics of Patients1.

| Characteristic | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Lower-Extremity-Fracture Types | ||

| Hip Fracture | 17,344 | 73.4 |

| Fracture of Femur | 2,953 | 12.5 |

| Pelvic Fracture | 1,532 | 6.5 |

| Major Multiple Fracture | 1,808 | 7.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 5,851 | 24.8 |

| Female | 17,786 | 75.2 |

| Admission Source | ||

| Home | 629 | 2.7 |

| Board and Care Facility | 34 | 0.1 |

| Transitional Living Facility | 13 | 0.1 |

| Intermediate Care Facility | 43 | 0.2 |

| Skilled Nursing Facility | 494 | 2.1 |

| Acute Unit of Same Hospital | 8,530 | 36.1 |

| Acute Unit of Different Facility | 13,800 | 58.5 |

| Chronic Hospital | 17 | <0.1 |

| Alternative Level of Care | 16 | <0.1 |

| Other Rehabilitation Facility | 6 | <0.1 |

| Other | 27 | 0.1 |

| Discharge Source | ||

| Home | 19,032 | 80.5 |

| Board and Care | 638 | 2.7 |

| Transitional Living Facility | 139 | 0.6 |

| Intermediate Care Facility | 324 | 1.4 |

| Skilled Nursing Facility | 3,217 | 13.6 |

| Chronic Hospital | 8 | <0.1 |

| Alternative Level of Care | 100 | 0.4 |

| Other | 179 | 0.8 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Age | 76.5 | 13.3 |

| Physical Disability | ||

| Motor FIM Score | ||

| Admission | 45.9 | 10.6 |

| Discharge | 67.4 | 13 |

| Cognitive Disability | ||

| Cognitive FIM Score | ||

| Admission | 29.3 | 6.5 |

| Discharge | 30.7 | 5.7 |

| Length of Stay in Days | 17.4 | 8.6 |

N = 23,637

NOTES: FIM is Functional Independence Measure. Twenty-eight cases were missing admission source. Patients who died, were discharged to different rehabilitation units, or went to acute hospital services were not included in these data because they were not used to develop functional outcome norms. Those cases would need to be studied separately.

SOURCE: Stineman, M., University of Pennsylvania, and Granger, C, State University of New York at Buffalo, 1997.

Figure 1. Lower-Extremity-Fracture (LEFX) Length-of-Stay Function-Related Groups.

Figure 2. Lower-Extremitv-Fracture (LEFX) Discharqe-Motor Functional Independence Measure Function-Related Groups (DMF-FRGs).

Table 5. Percent of Patients Discharged to Home or Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF).

| DMF-FRG | Home | SNF |

|---|---|---|

| LEFX- 1 | 42.2 | 44.6 |

| LEFX- 2 | 44.6 | 44.6 |

| LEFX- 3 | 95.7 | 4.3 |

| LEFX- 4 | 50.6 | 38.7 |

| LEFX- 5 | 44.4 | 42.1 |

| LEFX- 6 | 51.0 | 36.3 |

| LEFX-7 | 62.0 | 30.5 |

| LEFX- 8 | 54.9 | 34.4 |

| LEFX- 9 | 60.7 | 29.6 |

| LEFX-10 | 75.9 | 18.2 |

| LEFX-11 | 65.7 | 24.5 |

| LEFX-12 | 82.2 | 12.2 |

| LEFX-13 | 65.9 | 24.3 |

| LEFX-14 | 85.6 | 9.5 |

| LEFX-15 | 77.7 | 12.8 |

| LEFX-16 | 90.9 | 5.4 |

| LEFX-17 | 93.2 | 3.8 |

| LEFX-18 | 95.0 | 1.9 |

NOTES: FRG is Function Related Group. FIM is Functional Independence Measure. LEFX signifies a Lower Extremity Fracture FRG. DMF-FRG indicates a discharge motor-FIM FRG. Percents do not add to 100.0 because only the two most-frequent disposition locations are provided.

SOURCE: Stineman, M., University of Pennsylvania, and Granger, C, State University of New York at Buffalo, 1997.

Figures 3 and 4 display the 1995 LOS and motor-FIM benchmarks graphically. The 25th-, 50th-, and 75th-percentile LOS and motor-FIM scores are presented for each FRG. These benchmarks, in combination with the LOS-FRG and DMF-FRG trees shown in Figures 1 and 2, detail patients' prognoses for functional recovery and provide an anticipated LOS range with respect to initial severity of motor and cognitive disability and age.

Figure 3. 1995 Lower-Extremity-Fracture Length-of-Stay Norms.

Figure 4. 1995 Lower-Extremity-Fracture Functional Outcome Benchmarks.

Discussion

Predictors of Rehabilitation Outcomes and LOS

The general predictive associations in patients with hip fracture are consistent with other categories of impairment and with other reports (Harada, Sofaer, and Kominski, 1993; Heinemann et al., 1994; Hosek et al., 1986). Severity of physical disability following lower extremity fracture is the most important determinant of functional level at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. In line with clinical expectations, patients who present with less severe disabilities tend to function at higher levels at discharge. Age and/or cognitive disabilities modify this primary association such that those who present with similar degrees of physical disabilities who are young and who have few if any cognitive deficits tend to achieve greater recovery. Patients classified in DMF-FRGs associated with less severe disabilities and younger age are also more likely discharged home as opposed to an SNF. The LOS-FRGs have a simpler structure, requiring only four patient groups to explain variation in LOS.

Although for most impairment categories the dominant predictive association is between greater disability and longer stay, there was a non-linear relationship between functional ability and LOS in those with lower extremity fracture. The fact that patients with very severe physical and cognitive disabilities, as a group, had shorter stays than those with more moderate disabilities is justifiable if, by virtue of severity, they were unable to achieve gains comparable to those with less severe disabilities and if they legitimately required shorter episodes of rehabilitation to realize more limited potential. Conversely, the shorter stays may also reflect clinician bias against more severe deficits.

Uses in Quality Improvement

Rehabilitation is intended to achieve optimal function, even if the underlying pathology cannot be completely reversed (DeLisa, Martin, and Currie, 1988). This involves attempts to forestall or reduce the need for long-term institutionalization whenever feasible. Postacute rehabilitation is distinct from and functionally intermediate between the acute and chronic care paradigms. Improved physical ability and discharge to the community are among the most measurable and clinically meaningful patient outcomes, and, thus, degree of functional recovery and home-discharge rates can provide valuable benchmarks for quality monitoring in rehabilitation medicine. Once clinicians and managers of health care systems know more about the determinants of these outcomes and the mechanisms by which they occur, creative attempts to enhance their achievement at multiple points in the causal pathway may be possible, making outcomes management a reality (Wilson and Kaplan, 1995).

The DMF-FRGs present clinical profiles for which severity-adjusted norms can be established and periodically updated. These benchmarks permit comparison of groups of patients whose outcomes (discharge function and community-discharge rates), adjusting for risk, are higher or lower than expected. When combined with norms from the LOS-FRGs, the benchmarks can approximate associations between resource use and quality. One approach, Efficiency Pattern Analysis (EPA) (Stineman et al, 1995; Stineman et al., 1996a), yields a matrix whereby resource use and outcomes are directly linked in such a way as to define distinct groups of patients who demonstrate differing patterns of efficiency. In the high-efficiency pattern, for example, patients have shorter-than-expected LOS (or lower costs) and higher-than-expected levels of functional recovery. Case-mix-adjusted rates of home discharge or any other measurable outcome might be added to EPA. This approach can be used to quantify variations in process associated with differences in quality, cost, and fiscal policy (Jewell, 1995). The FIM-FRG modules can also be used within guidelines or to study the impact of clinical pathways. Expected LOS, expected costs, and/or outcome norms from the modules can be embedded as benchmarks within pathways. Such an approach was piloted for stroke rehabilitation by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (1995) Although studies based on FIM-FRGs show promising predictive associations at the patient level, facilities submitting data to the UDSmr are not the full universe of Medicare inpatient rehabilitation facilities, and benchmarks provided do not represent all providers in the Nation at large.

Uses in Monitoring

If quality of care criteria based on outcomes are to be credible, it must be demonstrated that differences in outcome will result from changes in the processes of care under the control of health care professionals or in the configuration of health systems under the control of policy analysts (Brook, McGlenn, and Cleary, 1996). The analysis of FIM-FRG benchmark quality indicators could provide regulatory agencies, managed care organizations, health plans, or any sufficiently large group of facilities with explicit criteria for determining whether the results of care are consistent with statistically and clinically established expectations (Brook, McGlynn, and Cleary, 1996). We might expect that facilities providing excellent care would discharge a larger proportion of patients to home or have higher functional outcomes after adjusting for patient severity. When comparing the adjusted outcomes of small facilities with large facilities, it may be necessary to combine patient records across similar impairment categories because of the smaller number of cases across which averaging can occur. One approach might first classify and then combine all lower-extremity-fracture, joint replacement, and other orthopedic patients into a set of closely related musculoskeletal impairments. Policy analysts could explore regional differences, the impact of specific policy decisions, the influence of managed care penetration, or the results of substitution of care in one setting for care in another. Should the postacute management of hip fracture patients largely shift to nursing homes, for example, the FIM-FRGs might address the degree to which patient outcomes are maintained.

Because the FIM-FRG systems provide distinct clinical profiles, these or similar systems might yield quality monitors spanning the full postacute care continuum as illustrated in Figure 5. Should a comprehensive FIM-based patient information system be established across the full continuum, expected patterns of resource use and outcomes could be established at set points along the treatment trajectory. Those time points might include analyses at any change in venue, such as admission to and discharge from the hospital and at the conclusion of formal home or outpatient rehabilitation services. This would track costs and outcomes associated with each episode along the trajectory of care. Alternatively, or in addition, data collection time frames might be set at fixed intervals following onset of a disabling condition, for example, at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after a fracture. This bundled approach would provide more of an epidemiological focus, tracking total costs and outcomes at set periods after an event. Groups of patients stratified by functional severity along impairment-specific lines would need to be followed using a standard core set of parameters relevant to treatment processes and rehabilitation goals. This standardization would, for the first time, provide the opportunity to compare patient outcomes achieved by various subcontractors, service providers, or health plans, irrespective of the mix and costs of services provided. Expansion across the postacute care continuum would require ongoing modifications of the FIM-FRG modules to include additional predictors, outcomes, and measurement indices relevant to the broader postacute care population.

Figure 5. A Framework for Monitoring Rehabilitation Postacute Care.

The selection of outcomes and classifying variables will require a proper match of measures appropriate to the goals of each segment of the treatment program. Measures of comorbidity and social supports available in the community would be paramount, because those factors influence rehabilitation need, process, and outcomes. The analysis of outcomes and resource use is a dynamic process. Indicators of quality must be updated periodically to reflect advances in medical knowledge and changing systems of health care. Yet certain measures must remain unchanged to allow assessment of progress over time. New measures should be added that reflect quality across different dimensions (Epstein, 1995), thus creating a topology of outcomes relevant to people with disabilities across all settings.

Integrating Outcome Technology and Payment

A PPS for inpatient rehabilitation using cost FRGs, in the short term, could relieve some of the inequities of service access and payment encouraged by the TEFRA system (Carter et al., 1997a). As in the DRG-based PPS, an FRG-based PPS would reward hospitals for the timely discharge of patients but not for the quality of outcomes achieved (Stineman et al., 1994; Sutton, DeJong, and Wilkerson, 1996). Quality outcomes could be encouraged either through payment or through the development of standardized monitoring systems for outcomes. Although implementation of an FRG-based PPS appears feasible in the short term, outcome-based payment would require further evaluation. A logical first step would be development of a standardized outcome monitoring system, using gain- or DMF-FRGs. The resulting quality indicators could be used either with or without a PPS to provide incentives for providers to maintain or improve patient outcomes while containing costs. Eventually, assuming appropriate payment simulations, adjustments for facility-level factors, accommodation of interrupted stays, and successful quality monitoring, it might be possible to develop a payment scheme incorporating clinical outcomes.

In one payment approach, patients would be assigned a DMF-FRG upon admission to medical rehabilitation. Hospitals would be paid based on the extent to which patients achieved levels of function that were less than, within, or greater than a specified range as established for their DMF-FRGs. In a second approach, patients would be assigned to an LOS-FRG upon admission and to a gain-FRG at discharge. A standardized basic payment rate would be established prospectively as the average national costs used to treat cases in the patient's LOS FRG. This rate would then be adjusted to reflect the extent to which patients achieved gains less than, within, or greater than a national average range established by gain-FRGs. This payment design involves an EPA-like matrix across which expected resource use (costs) and outcomes are superimposed. By using separate but parallel classification schemes, the interaction between payment and quality can be monitored and adjusted by changing the relative contributions of the cost and outcomes portions to the calculated payment rates. A final approach described by Sutton and colleagues (1996) would withhold a fixed proportion of the standard FRG payment amount, placing that amount in a “quality of care” pool and distributing that pool annually to providers whose case-mix-adjusted outcomes are attained at the facility level. Case-mix-adjusted outcomes could be determined from either the gain-or DMF-FRGs. A unified model of functional status-based payment and quality review could improve rehabilitation care by encouraging optimal outcomes in the context of incentives to reduce costs.

Because FIM ratings depend on judgment, clinicians may game the FRGs through subtle scoring manipulations. The FIM-FRGs by design were categorical rather than index-based to minimize gaming. Although an index would optimize use of statistical information from the FIM, it would be more susceptible to manipulation, because any small change in function would have an impact on payments received. In the FIM-FRGs, any coding manipulation would yield differences in payment only at the boundaries of the FRG groups. Because they have fewer groups, gain-FRGs may be less vulnerable to gaming than the DMF-FRGs. The LOS-FRGs may be the least susceptible because functional status is coded once rather than twice. External methods for monitoring FIM coding could be designed to detect facilities in which coding manipulation appears excessive.

Unified Models Across Postacute Care Providers

There is some overlap in the types of patients treated by inpatient rehabilitation facilities and SNFs (Kramer et al., 1997). One option in dealing with that overlap would be to determine the feasibility of modifying FRGs to include all patients receiving restorative-level rehabilitation within the full postacute continuum, regardless of setting. Such an approach to quality monitoring and payment could enhance continuity of care and discourage unnecessary shifts of patients across settings. All patients admitted to distinct-part units and rehabilitation hospitals would receive level-one rehabilitation, which, by definition, is high-intensity and restorative. In SNFs where service intensity varies and the clinical attributes and needs of populations are more heterogeneous, the overwhelming challenge would be distinguishing persons prospectively who have the potential for restorative rehabilitation from the larger group of nursing home residents who need either long-term care or a short convalescence. Like acute medical management, functional restoration requires intensive rehabilitation that is costly but time-limited and episodic. In contrast, long-term care requires an ongoing but lower daily investment of therapy and care-giving services. Among those with the capacity for functional restoration, an episodic payment approach such as an FRG-based PPS would tend to encourage timely discharge from the SNF to the community. In contrast, a per diem rate adjusted for severity of disability may provide financial incentives to maintain residents in their most dependent state. Although a unified payment system has appeal, its development presents challenges. One approach might combine elements of an episode-based system for short-term restorative-level rehabilitation patients within a larger per diem-based scheme.

Footnotes

Margaret G. Stineman is with the University of Pennsylvania; Carl V. Granger is with the State University of New York at Buffalo. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant Number R01-HD34378 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NICHD, the University of Pennsylvania, the State University of New York at Buffalo, or the Health Care Financing Administration.

Statements were made by Patrick A. Foster, Senior Vice President Inpatient Operations, HEALTHSOUTH Corporation, on behalf of the Federation of American Health Systems; Joseph P. Newhouse, Ph.D., Chairman, Prospective Payment Assessment Commission; Barbara Wynn, Acting Director, Bureau of Policy Development, Health Care Financing Administration; and Kathleen C Yosko, President/CEO, Schwab Rehabilitation Hospital and Care Network, on behalf of the American Rehabilitation Association.

Testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Health, April 10,1997.

Reprint requests: Margaret G. Stineman, M.D., Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 101 Ralston-Penn Center, 3615 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-2676.

References

- Breiman L, Freidman J, Olshen R, Stone C. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth International Group; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Cleary PD. Part 2: Measuring Quality of Care. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996 Sep;335(13):966–970. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter G, Buchanan J, Donyo T, et al. A Prospective Payment System for Inpatient Rehabilitation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND/UCLA/Harvard Center for Health Care Financing Policy Research; Jun, 1997a. PM-683-HCFA. A project memorandum prepared for the Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Carter G, Relles D, Buchanan J, et al. A Classification System for Inpatient Medical Rehabilitation Patients: A Review and Proposed Revisions to the Functional Independence Measure-Function Related Groups. Santa Monica, CA: RAND/UCLA/Harvard Center for Health Care Financing Policy Research; Jun, 1997b. PM-682-HCFA. A project memorandum prepared for the Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities. Standards Manual and Interpretive Guidelines for Medical Rehabilitation. Tucson, AZ.: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- DeLisa JA, Martin GM, Currie DM. Rehabilitation Medicine: Past, Present, and Future. In: DeLisa JA, editor. Rehabilitation Medicine. Principles and Practice. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein A. Performance Reports on Quality-Prototypes, Problems, and Prospects. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995 Jul;333(1):57–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Keith RA, et al. Advances in Functional Assessment for Medical Rehabilitation. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 1986 Apr;1(3):59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BB, Granger CV, Sherwin FS, et al. A Uniform National Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. In: Fuhrer MJ, editor. Rehabilitation Outcomes: Analysis and Measurement. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BB, Laughlin JA, Fiedler RC, Granger CV. Interrater Reliability of the 7-level Functional Independence Measure (FIM) Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 1994 Sep;26:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada ND, Sofaer S, Kominski G. Functional Status Outcomes in Rehabilitation: Implications for Prospective Payment. Medical Care. 1993 Apr;31(4):345–357. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199304000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann AW, Linacre JM, Wright BD, et al. Prediction of Rehabilitation Outcomes with Disability Measures. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1994 Feb;75(2):133–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek S, Kane R, Carney M, et al. Charges and Outcomes for Rehabilitative Care. Implications for the PPS. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Jewell MA. Quantitative Methods for Quality Improvement. Pharmacotherapy. 1995 Jan-Feb;15(1):27S–32S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer AM, Steiner JF, Schlenker RE, et al. Outcomes and Costs After Hip Fracture and Stroke: A Comparison of Rehabilitation Settings. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997 Feb;277(5):396–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD, et al. The Structure and Stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1994 Feb;75(2):127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prospective Payment Assessment Commission. Medicare and the American Health Care System: Report to the Congress. Washington, DC.: Jun, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stineman MG. Measuring Case Mix, Severity, and Complexity in Geriatric Patients Undergoing Rehabilitation. Medical Care. 1997 Jun;35(6):JS90–JS105. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199706001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stineman MG, Escarce JJ, Goin JE, et al. A Case Mix Classification System for Medical Rehabilitation. Medical Care. 1994 Apr;32(4):366–379. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199404000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stineman MG, Goin JE, Hamilton BB, Granger CV. Efficiency Pattern Analysis for Medical Rehabilitation. American Journal of Medical Quality. 1995 Winter;10(4):190–199. doi: 10.1177/0885713X9501000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stineman MG, Goin JE, Granger CV, et al. Discharge Motor-FIM-Function Related Groups. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1997a Sep;78(9):980–985. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stineman MG, Goin JE, Tassoni CJ, et al. Classifying Rehabilitation Inpatients by Expected Functional Gain. Medical Care. 1997b Sep;35(9):963–973. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stineman MG, Granger CV, Goin JE, Hamilton BB. Efficiency Pattern Analysis per la Medicina Riabilitativ: Una Versione Rapida per L'analisi de Efficienenza. Ricerca in Riabilitazione. 1996a Sep;5(2):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Stineman MG, Shea JA, Jette A, et al. The Functional Independence Measure: Tests of Scaling Assumptions, Structure, and Reliability Across 20 Diverse Impairment Categories. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1996b Nov;77(11):1101–1108. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stineman MG, Tassoni CJ, Escarce JJ, et al. Development of Function Related Groups Version 2.0: A Classification System for Medical Rehabilitation. Health Services Research. 1997c Oct;32(4):527–546. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton JP, DeJong G, Wilkerson D. Function-based Payment Model for Inpatient Medical Rehabilitation: An Evaluation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1996 Jul;77:693–701. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guide for the Use of the Uniform Data Set for Medical Rehabilitation (Adult FIM), Version 4.0. Buffalo, NY: State University of New York at Buffalo; 1995. The Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The Stroke/Amputee Rehabilitation Clinical Guideline Project. Rehabilitation Strategic Health Group, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Section; Memphis, TN: 1995. Unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IB, Kaplan S. Clinical Practice and Patients' Health Status: How Are the Two Related? Medical Care. 1995 Apr;33(4S):AS209–AS214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps. Geneva: 1980. [Google Scholar]