Abstract

In this article, the authors examine why low-income persons choose a managed care plan and the effects of choice on access and satisfaction, using data from the 1995-96 Kaiser/Commonwealth Five-State Low-Income Survey. Two-thirds of those choosing a managed care plan cited costs or benefits as their primary reason. Logistic regressions indicate that choice of plan had a neutral or positive effect on access and satisfaction. Medicaid enrollees with choice were less likely than those without to have difficulty obtaining particular services, more likely to rate plan quality highly, and less likely to report major problems with plan rules.

Introduction

Choice among health plans was initially viewed by policy analysts as a means of injecting competition into a market in which consumers were insulated from the cost of their purchases. The underlying premise was that, by selecting plans that best fit their individual needs, informed consumers would force health plans to improve their products. Ideally, the choice-competition scenario should have an impact on plans' cost and quality. Whether this is, in fact, occurring is still being evaluated (Hibbard and Jewett, 1997).

Consumers attempting to select the “best” plan are faced with a difficult decision, in part because of changes in the level and dimensions of choices available. Choice of plan is moving from the arena of large and sophisticated purchasers (primarily benefits managers at large companies) across the spectrum to poor and relatively less informed Medicaid enrollees; although selecting a plan is difficult regardless of personal circumstances, it is likely to be a particularly complex process for those with fewer resources available and for whom the consequences of the selection may be more serious.

Moreover, with the growth of managed care plans on the health plan menu, consumers must select more than just a financing system or means of protecting themselves from financial risk; they are also selecting an organization and delivery system (Scanlon, Chernew, and Lave, 1997). Consumers must now look beyond price to other dimensions of the plan, including quality, convenience, and provider choice. And the added uncertainty surrounding restrictions within a managed care framework may exacerbate the consequences of a “bad” choice. The issue of what information consumers need in selecting a plan—as well as how that choice affects the health plan market—is thus increasingly important. At issue is whether individuals are indeed able to obtain and fully evaluate the information available to them and make a choice that is appropriate to their situation. Without these “appropriate” selections by consumers, choice will not lead to better individual or market outcomes.

The purpose of this article is to add to the existing empirical work on choice of health plan by examining (1) the reasons why low-income persons choose a managed care plan and (2) the effects of choice of plan on access to health care services and satisfaction with care. It is particularly important to have this sort of empirical information pertaining to low-income populations. This knowledge may be useful to those designing programs involving choice for the low-income population and State policymakers as they oversee the Medicaid population moving into managed care.

Background

Increased consumer choice among health plans has prompted a variety of studies of how choices are made as well as the effects of having choice. In terms of reasons cited for choosing a particular health plan, study findings vary as do the approaches to gathering information, though it is clear that cost plays an important role in the decisionmaking process for many privately insured persons. In a review of 35 published articles on health plan choice, Scanlon, Chernew, and Lave (1997) report that “(a)lmost all authors found price (usually premium or employee contribution to premium) to have a statistically significant negative effect on the probability of enrolling in a health plan.” Davis and colleagues (1995) reported that 31 percent of families choosing managed care plans said that the main reason for their choice was related to cost. Compared with the Davis study (1995), an Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) study (1996), which included persons in both fee-for-service (FFS) and managed care plans, found that a much lower proportion (18 percent) of adults selected their plan because of cost considerations. Gibbs, Sangl, and Burrus (1996), in designing focus groups to explore consumer's information needs for choosing among health plans, sorted by income based on “know(ledge) from recent groups … as well as from the literature … that the health plan choices of lower-income purchasers are largely determined by financial considerations.”

In addition to cost, quality has often been cited as a reason for plan selection. In the AHCPR study (1996), 42 percent of adults reported that their most important concern in choosing a health plan was quality. With respect to recommendations from others or published plan ratings used in evaluating plan differences, findings from the AHCPR study (1996) indicate that personal physicians and family and friends have the most influence on people's plan selection.

Individual characteristics can also be important in affecting plan choice. A study by Rice, McCall, and Boismier (1991) examining the quality of Medicare supplemental plans purchased found that persons with higher levels of education were more likely to purchase high-quality plans. Another study (Research Triangle Institute, Health Economics Research, and Benova, 1996) with a broader focus on a range of plan types reported that “… [K]nowledge [about health care options] tended to be higher among persons with a higher education.” Gibbs and colleagues (1996) noted that privately insured consumers with chronic disease in their family paid more attention to benefits than did healthier families.

In terms of Medicaid, it has become clear through a number of State efforts to implement managed care programs that the Medicaid population may require special assistance in making choices among health plans. Gold, Sparer, and Chu (1996) note that enrollment and marketing to Medicaid enrollees requires explaining how to make choices and the implications of those choices. In addition, they found that “(h)igher-than-expected telephone volume, illiteracy among beneficiaries, marketing abuses, low rates of plan selection, and inappropriate selections of plan because of poorly designed enrollment forms were among the problems States encountered” in implementing Medicaid managed care programs (Gold, Sparer, and Chu, 1996). Gibbs, Sangl, and Burrus (1996) reported that, for the Medicaid population, convenience of location was the single factor most frequently mentioned in influencing plan choice, and ability to visit the doctor of their choice was a common secondary reason.

The effects of plan choice on satisfaction, as measured by ratings of health care plans by consumers, have also been examined in the literature; the two studies described here have both found strong relationships between plan choice and satisfaction. In the study by Davis et al. (1995), satisfaction with managed care was explored. Because there is likely to be self-selection into managed care (i.e., those most likely to be satisfied with managed care are most likely to choose it), designers of the study chose comparison groups of persons in managed care and FFS who had selected to be in that plan (rather than persons with no choice). Their conclusion was that plan choice appears to be strongly related to satisfaction; the authors conclude that “plan choice itself, including an FFS option, may help to protect access and quality. The freedom to change plans is likely to strengthen the voice of enrollees and the ability of their physicians to act in the best interest of their patients” (Davis et al., 1995). Despite overall greater satisfaction among persons with choice, the Davis study also found that there was a persistent pattern of lower ratings by low-income enrollees.

In a separate study of enrollee satisfaction, Ullman et al. (1997) analyzed data from a survey of enrollees in four large health maintenance organizations (HMOs). Available options included point-of-service and network-only plans; some survey respondents were able to choose between these two types of plans, but others had no choice. Similar to the Davis et al. (1995) study, the authors found that the availability of choice led to increased satisfaction regardless of which plan was chosen; those enrolled in the point-of-service plan who had not been given a choice were not any more satisfied than the network-only respondents who had no choice. The conclusion was, then, that “what mattered [for satisfaction] was having choice at enrollment, not at the point of service” (Ullman et al., 1997).

Data and Methods

This study is based on a survey of health insurance coverage and access to care administered to a probability sample of low-income, non-elderly adults in five States. The study was jointly funded by The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund, with the survey conducted by Louis Harris and Associates. Approximately 2,000 low-income, non-elderly adults were interviewed in each of the following five States: Florida, Minnesota, Oregon, Tennessee, and Texas. The States were selected to provide varying examples of rapid as well as slower movement toward managed care, and Medicaid programs with innovative expansions and those structured more traditionally.

Interviews were conducted by telephone, with fieldwork taking place from summer 1995 through spring 1996. Within each State, areas were stratified by telephone exchanges. Telephone exchanges in areas with median household incomes of $27,000 or less were included in the sampling frame, from which telephone numbers were randomly selected (within each telephone exchange in proportion to the number of households served by the selected telephone exchanges). Interviewers screened households by age (18-64 years of age) and income (less than or equal to 250 percent of poverty). The overall survey response rate was 54 percent of those likely to be eligible for the survey based on the income and age criteria. Exclusive reliance on telephone interviewing may underrepresent access problems (because of lack of coverage of non-telephone households) or may overrepresent these problems because of systematic non-response to telephone surveys by persons for whom access is not an issue of interest (Berk and Schur, 1998). All data presented in this article are weighted to reflect known distributions for gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, number of adults in the household, and urbanization for the low-income, adult population in each State; as is customary, because of survey non-response, weights are adjusted to 2-year averages of data from the March 1994 and March 1995 Current Population Surveys (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1994, 1995). The final sample is representative of low-income adults under age 65 living in all but the wealthiest areas of these States.

Information was gathered about basic demographic characteristics, health status, health insurance coverage, access to care, and use of services. Specifically of interest to this analysis, respondents were asked: (1) whether they had a choice of health insurance plan; (2) the primary reason they had chosen the plan in which they were enrolled; and (3) ratings of various aspects of their plan. During the survey pretest, many respondents appeared to have trouble indicating whether or not they had a choice of plan. This difficulty was primarily with Medicaid respondents who failed to elect a specific plan and were, therefore, administratively assigned. For this analysis, respondents who were assigned to a plan—irrespective of whether they were offered the opportunity to choose—were classified as having no choice because they did not, in fact, exercise one. Although this categorization combines two somewhat different groups (those who were not given choice and those who had choice available but did not actively choose), the policy focus here is on whether those who exercise choice are better off (e.g., in terms of access or satisfaction) than those who do not exercise choice. To examine this issue, we believe the comparison used in our analysis—between persons who actively selected their plan and those who did not—is appropriate.

Plans were classified as to whether or not they were managed care, based on a series of checks including verification of plan name. Respondents were classified as being in managed care based on one of the following criteria: The respondent reported a health plan name certified as an HMO according to the directory of HMOs in the Group Health Association of America guide or reported by one of the States as a Medicaid HMO; the respondent reported that he/she was in an HMO or preferred provider organization; the respondent reported that he/she was required to choose from a list of doctors or clinics and was not in FFS; the respondent reported that he/she was required to choose from a list of doctors and was in FFS, but reported out-of-plan use in the past year.

A list of reasons for selecting their health plan was compiled from the responses of survey participants and regrouped into the following eight categories for this analysis: (1) cost/less expensive; (2) good/better benefits or includes dental benefits; (3) suggested by social services worker, information provided by plan at social services office, family/friend suggested it, suggested by employer benefits counselor, plan had good reputation or familiar with plan; (4) job change or change in family; (5) doctor participates/suggested it; (6) plan offered gift, saw advertising, information provided by plan in door-to-door marketing; (7) plan easy to use or good location; and (8) not sure. These reasons are analyzed only for those persons who selected a managed care plan.

Reasons for choosing a managed care plan are examined separately for the privately insured and those covered by the Medicaid program because of underlying population differences and differences in programmatic features. Variation in reasons for choosing a plan are also examined by sociodemographic characteristics and across States. In general, cost-sharing under Medicaid is minimal, with the most extensive cost-sharing in the Tennessee program. We used two different health-status indicators: (1) a person is classified as being in worse health if he or she reports fair or poor health or has a serious illness; (2) the second measure indicates the presence of a chronic condition in the family (either heart disease, asthma, or diabetes). Because the survey is clustered in five States, standard errors were computed with SUDAAN, which uses the Taylor series linearization method to account for the complex survey design (Shah, Barnwell, and Bieler, 1995). Tests of statistical significance were used to assess whether differences in population estimates exist at specified levels of confidence. Only differences that are statistically significant at a 95-percent confidence level are discussed herein.

To examine how having choice affects individuals' access to health care services and their satisfaction with care, we constructed a multivariate model in which the primary independent variable of interest was whether or not the person had a choice of plan. The purpose is to look at the effect of choice on access and satisfaction, controlling for the type of delivery system (i.e., managed care versus FFS) as well as other person-level sociodemographic and health-status characteristics.

Access to care and satisfaction with the plan were measured using eight dependent variables, as shown in Table 1. Table 2 contains means for all dependent and independent variables in the models. Given that the Medicaid and privately insured populations themselves as well as the underlying parameters facing these populations are distinctly different, we ran both separate and combined models. For each dependent variable, a Chow test was used to assess if pooling of the two populations was statistically appropriate (Green, 1990). The final sample sizes for these two groups were 2,024 Medicaid enrollees and 5,246 privately insured.

Table 1. Access and Satisfaction Indicators.

| Access Indicators | Satisfaction Indicators |

|---|---|

| Regular Place to Get Care | Rated Plan Quality as Good or Excellent |

| Unable to Obtain Needed Care | Rated How Doctor Cares About Respondent as Good or Excellent |

| Unable to Obtain Needed Specialty, Diagnostic, or Mental Health Care or Prescription Medicines | Rated Cost of Plan (Copayments and Deductibles) as Good or Excellent |

| Rated Time to Get Appointment or Wait to See Physician as Poor or Fair | Reported Major Problem With Plan Rules, Delay in Approval, or Problem With Covering Service or Physician |

SOURCE: Schur, C., and Berk, M., Project HOPE, Bethesda, MD, 1997.

Table 2. Means of Dependent and Independent Variables for Study Population, Weighted.

| Variable | Medicaid Enrollees | Privately Insured |

|---|---|---|

| All | 2,024 | 5,246 |

| Percent | ||

| Dependent Variables - Access | ||

| Has Regular Place to Get Care | 68 | 66 |

| Unable to Obtain Needed Care | 14 | 7 |

| Problems With Time to Get Appointment or Office Waiting Times | 42 | 38 |

| Problem Getting Medication, Mental Health Care, Specialist Care, or Diagnostic Test | 10 | 5 |

| Dependent Variables - Satisfaction | ||

| Rated Plan Quality as Good or Excellent | 78 | 78 |

| Rated How Doctor Cared as Good or Excellent | 79 | 82 |

| Rated Cost of Plan as Good or Excellent (Copayment/Deductible) | 67 | 60 |

| Reported Major Problem With Rules, Coverage of Services, Coverage of Doctor, or Delay While Waiting for Approval | 17 | 11 |

| Independent Variables | ||

| Had Choice of Plan | 45 | 43 |

| Enrolled in Managed Care | 67 | 58 |

| Enrolled in Plan Less than 2 Years | 54 | 40 |

| Age | ||

| Under 30 Years | 38 | 30 |

| 30-44 Years | 37 | 42 |

| 45-64 Years | 25 | 27 |

| Female | 63 | 52 |

| Years of Education | ||

| Not Completed High School | 27 | 11 |

| High School | 44 | 44 |

| Beyond High School | 28 | 45 |

| Fair/Poor Health or Serious Illness | 49 | 26 |

| Chronic Condition in Family | 41 | 29 |

SOURCE: Project HOPE tabulations based on the Kaiser/Commonwealth Five-State Low-Income Survey, 1995-96.

Findings

Choosing a Managed Care Plan

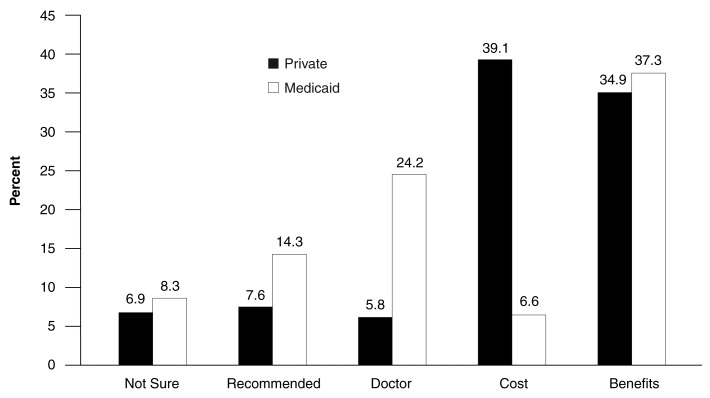

Overall, the range of covered services available and the costs of joining a plan and obtaining services were cited as the most important reasons for choosing a plan, with almost two-thirds of survey respondents who chose a managed care plan citing one of these two reasons. Although benefits remained an important reason for both groups (more than one-third of each group), when we looked separately at persons covered by Medicaid and by private insurance, there was a difference in terms of the proportion of respondents citing cost as their primary reason for choice (Figure 1). Approximately 39 percent of the privately insured choosing a managed care plan cited cost as their main reason; in contrast, among Medicaid enrollees choosing a managed care plan, only 7 percent stated that cost was the primary factor. This is not surprising given that Medicaid enrollees are, in general, protected from significant cost-sharing requirements.

Figure 1. Primary Reason for Choosing a Managed Care Plan 1.

1 Of those currently enrolled in managed care.

NOTE: Percentages do not sum to 100 because of other reasons, not listed in figure.

SOURCE: Project HOPE estimates from the Kaiser/Commonwealth Five-State Low-Income Survey, 1995-96.

Almost one-quarter of those in the Medicaid program stated that they chose a particular plan either because their doctor participated in that plan or their doctor recommended it. The proportion of the privately insured population citing this reason was much lower, only 5.8 percent. Medicaid enrollees were also more likely than those with private insurance to select a plan based on a recommendation, either from family, friends, a social services worker, or an employee benefits counselor. Less than 1 percent of either group responded that they had chosen their plan based on advertising, door-to-door marketing, or the offer of a gift.

In addition to comparing persons covered by Medicaid and private insurance, within each of these groups, we examined the primary reason for choice among various population subgroups. Differences by sociodemographic characteristics are discussed later and shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Primary Reason for Choosing a Managed Care Plan, by Selected Characteristics.

| Choosing Managed Care Plan for: | Benefits | Cost | Doctor Participates or Recommended | Recommended1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Private Insurance | Medicaid | Private Insurance | Medicaid | Private Insurance | Medicaid | Private Insurance | Medicaid | |

|

| ||||||||

| Percent | ||||||||

| All Persons | 34.9 | 37.3 | 239.1 | 6.6 | 25.8 | 24.2 | 27.6 | 14.5 |

| Persons With Chronic Condition | ||||||||

| Yes | 37.7 | 41.8 | 36.5 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 23.8 | 6.5 | 12.9 |

| No | 33.6 | 33.8 | 40.3 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 24.4 | 8.1 | 15.7 |

| Persons With Serious Illness or in Fair/Poor Health | ||||||||

| Yes | 34.5 | 38.7 | 37.1 | 5.4 | 7.8 | 27.6 | 6.9 | 11.5 |

| No | 35.1 | 36.0 | 39.8 | 7.7 | 5.1 | 21.1 | 7.6 | 17.0 |

| Persons With More Than a High School Degree | 34.1 | 41.8 | 341.2 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 23.2 | 6.5 | 14.1 |

| Persons With a High School Degree | 34.0 | 34.6 | 39.1 | 8.3 | 5.4 | 27.4 | 9.0 | 13.9 |

| Persons With Less Than a High School Degree | 44.3 | 37.3 | 26.1 | 5.0 | 3.8 | 20.0 | 7.1 | 15.8 |

| Persons Below 100 Percent of Poverty Level | 37.8 | 39.2 | 38.4 | 6.1 | 3.0 | 22.5 | 10.4 | 14.9 |

| Persons at 100-150 Percent | 34.8 | 33.1 | 35.9 | 3.5 | 47.5 | 30.9 | 8.7 | 15.0 |

| Persons at 150-200 Percent | 34.4 | NA | 41.4 | NA | 46.3 | NA | 45.4 | NA |

| Persons at 200-250 Percent | 32.4 | NA | 41.2 | NA | 5.6 | NA | 6.1 | NA |

| Persons Living In: | ||||||||

| Minnesota | 33.3 | 37.4 | 40.1 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 28.6 | 3.3 | 56.5 |

| Oregon | 38.4 | 35.9 | 38.2 | 6.1 | 3.6 | 633.2 | 5.6 | 59.0 |

| Tennessee | 43.6 | 37.1 | 32.7 | 6.9 | 5.6 | 19.7 | 7.4 | 18.8 |

| Florida | 529.3 | 49.0 | 41.1 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 16.5 | 710.6 | 11.4 |

| Texas | 531.4 | NA | 542.4 | NA | 7.2 | NA | 79.0 | NA |

Recommended by family, friend, social services worker, or employee benefits counselor.

Different from Medicaid.

Differerent from less than high school.

Different from less than 100 percent Federal poverty level.

Different from Tennesee.

Different from Florida.

Different from Minnesota.

NOTES: NA is not applicable. Differences between persons on private insurance and Medicaid were tested for “All Persons” only. All other tests were between subgroups within type of coverage. All differences noted are at 95-percent confidence level.

SOURCE: Project HOPE tabulations based on the Kaiser/Commonwealth Five-State Low-Income Survey, 1995-96.

Across the five survey States, there was little variation in the reasons for choice. For the privately insured, persons in Tennessee were more likely than those in either Texas or Florida to choose based on benefits (44 percent versus 31 percent and 29 percent, respectively). And a larger percentage of the privately insured in Texas compared with Tennessee made their selection based on cost (42 percent versus 33 percent, respectively).

Variation among Medicaid enrollees was also small with few statistically significant differences across States. It should be noted that the Medicaid managed care population was substantial in only two of the States—Tennessee and Oregon—with no Medicaid managed care enrollees at all in Texas. Oregon Medicaid enrollees were more likely than those in Florida to choose their managed care plan based on a doctor's recommendation or participation (33 percent in Oregon versus 16 percent in Florida). And Medicaid enrollees in Oregon and Minnesota were less likely than those in Tennessee to choose based on the recommendation of family or friends (19 percent in Tennessee, compared with 9 percent in Oregon and 6.5 percent in Minnesota).

Variation by Demographic Characteristics

We also examined variation in reason for choice by respondent health status, poverty status, and level of education. The literature suggests that poor persons are more likely to choose plans based on cost; this effect might be masked somewhat because the survey sample is limited to those with low incomes. One might expect that persons in poor health would choose differently, perhaps more likely to choose based on the availability of specific benefits or in order to remain with a trusted doctor. Finally, we expected that education would play a role in choice, with persons with more education less likely to be influenced by recommendations or marketing, and less likely to be “unsure” as to why they made their choice. Some evidence from the literature suggests that persons with chronic conditions are more likely to choose a plan based on benefits and that the less educated may choose plans of lesser quality.

As previously described, we used two different health-status indicators-one indicating the reporting of fair or poor health or of a serious illness, and the other indicating the presence of a chronic condition in the family (either heart disease, asthma, or diabetes). We found that persons classified as being in poor health based on the first measure did not vary significantly in the reason given for choosing a health plan compared with those categorized as healthier. Neither did the family-level chronic condition indicator appear to influence the reason for choice, with no statistically significant differences in the privately insured or Medicaid populations.

We examined differences in reason for choice by education where education was a tri-level variable as follows: less than high school education, completed high school, some schooling beyond high school. For those with private insurance, the more educated were more likely to report cost as the reason for choosing; 41 percent of persons with more than a high school degree based their selection on cost, compared with 26 percent with less than a high school education. There were no other significant differences by level of education.

Variation by poverty status was only examined for the privately insured because the vast majority of the Medicaid population have incomes below 150 percent of the poverty level. Among the privately insured, those with incomes below 100 percent of the Federal poverty level were half as likely to have chosen a plan based on the doctor participating or recommending it and were somewhat more likely to choose because of advice from family and friends. There was no variation by poverty status in the proportion of persons choosing based on the cost of the plan.

Access and Satisfaction

To explore how having a choice of plan affects both access to health care services and satisfaction with the plan selected, a multivariate model was specified with the eight indicators of access and satisfaction listed in Table 1 as dependent variables. In addition to whether an individual had a choice of plan, a number of independent variables were included (Table 2). In particular, both managed care and FFS enrollees were included in the models to determine whether managed care might have an independent effect on access and satisfaction. The insured population examined consists of both those with private insurance as well as persons enrolled in the Medicaid program. Because the composition of these populations is quite different and their behaviors in response to a given stimulus (e.g., choice) may be different, we used a Chow test to assess whether the observations should be pooled or whether separate models should be run.

For all of the dependent variables, the test allows us to reject the hypothesis that these groups are structurally similar enough to be considered one population group. Thus the information provided by this test leads us to conclude that there is a loss of information when these groups are analyzed jointly rather than separately and that the separately estimated models are more precise and more sensitive to the structural characteristics of the individual groups. In a practical sense, these results indicate that there are underlying differences in how the privately insured and those on Medicaid interface with the health care delivery system.

In the following sections, we discuss findings with respect to both access and satisfaction, separately for the Medicaid and privately insured populations. Odds ratios (OR) and indications of significance are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4. Effect of Plan Choice on Access to Care, Results From Logistic Regression Model (Odds Ratios).

| Variable Description | Dependent Variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Has Regular Provider | Inability to Obtain Care | Problems With Waiting Times | Difficulties With Other Services | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Medicaid | Private | Medicaid | Private | Medicaid | Private | Medicaid | Private | |

| Choice | NS | **1.28 | **0.65 | NS | NS | ***0.71 | ***0.54 | NS |

| Managed Care | *1.45 | **1.10 | **1.82 | *1.41 | *1.39 | NS | ***2.86 | **1.70 |

| Time in Plan | **0.67 | **0.75 | *1.40 | **1.64 | NS | *1.20 | NS | NS |

| Age Under 30 Years | ***0.36 | ***0.49 | NS | **2.10 | ***2.36 | ***1.72 | NS | NS |

| Age 30-44 Years | **0.56 | **2.77 | ***2.29 | ***2.06 | ***2.44 | ***1.70 | **1.79 | NS |

| Female | ***2.53 | ***2.10 | NS | **1.53 | NS | NS | NS | *1.42 |

| High School Not Completed | **0.61 | **0.61 | *1.55 | NS | NS | NS | **0.53 | **0.44 |

| High School Completed | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | *0.66 |

| Sicker | **1.48 | NS | ***1.97 | ***3.91 | NS | ***1.55 | ***3.22 | ***3.32 |

p < 0.10.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

NOTE: Odds ratios are not given where coefficient is not statistically significant (NS).

SOURCE: Project HOPE estimates based on the Kaiser/Commonwealth Five-State Low-Income Survey, 1995-96.

Table 5. Effect of Plan Choice on Satisfaction, Results From Logistic Regression Model (Odds Ratios).

| Variable Description | Dependent Variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Plan Quality | Doctor Cares | Plan Costs | Plan Hassle | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Medicaid | Private | Medicaid | Private | Medicaid | Private | Medicaid | Private | |

| Choice | ***2.09 | ***1.77 | **1.54 | NS | *1.35 | ***1.72 | ***0.43 | NS |

| Managed Care | **0.38 | NS | ***0.39 | NS | NS | ***1.36 | ***2.80 | *1.60 |

| Time in Plan | NS | *0.76 | NS | NS | *1.34 | NS | NS | NS |

| Age Under 30 Years | NS | NS | **0.44 | ***0.58 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Age 30-44 Years | *0.69 | **0.78 | **0.52 | ***0.64 | NS | **0.81 | *1.73 | ***2.12 |

| Female | *1.36 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | **1.67 |

| High School Not Completed | NS | **0.64 | NS | NS | **0.63 | *0.75 | NS | NS |

| High School Completed | NS | **0.79 | NS | NS | NS | *0.84 | **0.53 | NS |

| Sicker | *0.16 | ***0.61 | *0.70 | ***0.59 | NS | ***0.59 | NS | ***2.94 |

| Chronic Condition in Family | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

p < 0.10.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

NOTE: Odds ratios are not given where coefficient is not statistically significant (NS).

SOURCE: Project HOPE estimates based on the Kaiser/Commonwealth Five-State Low-Income Survey, 1995-96.

Access to Health Care Services

Our findings with respect to the effect of choice of plan on access to care are mixed. For both Medicaid enrollees and low-income persons with private insurance, having a choice of plan increases access to care as measured by two of the four access indicators used and has no effect on access for the other two indicators. Of interest, the two access measures showing an effect differ between the two populations.

For Medicaid enrollees, having a choice of plan had no effect on the likelihood of an individual having a regular place to go for care or of an individual reporting that waiting time—either for scheduling an appointment or in the physician's waiting room—was poor or fair. In contrast, for the privately insured population, those with choice were more likely to have a regular provider (OR = 1.28) and less likely to have problems with waiting times (OR = 0.71).

In terms of inability to obtain different types of care, Medicaid enrollees with choice were less likely than those without choice to report having a problem obtaining all of the medical care they needed (OR = 0.65) and were also less likely to have an unmet need for at least one other type of care asked about (OR = 0.54). For the low-income population with private insurance, choice of plan had no effect on ability to obtain any of the types of health care services.

Offering choice of plan often involves an “open season” or periodic opportunity for switching from one plan to another. A variable measuring length of time enrolled in the plan was included in the model to see if new plan members had different experiences in terms of access to care. We found that persons who had been in the plan for less than 2 years were less likely to have a regular provider and more likely to report inability to obtain medical care than longer term enrollees. The effect of time in plan was not statistically significant in terms of problems gaining access to other services, and waiting times were reported to be more of a problem only for the privately insured.

Satisfaction With Plan

Plan choice appears to have a more consistent effect on satisfaction for Medicaid enrollees but presents a mixed picture again for low-income persons with private insurance.

For all four satisfaction indicators, plan choice appears to increase satisfaction for Medicaid enrollees. Compared with Medicaid enrollees who did not choose their plan, those with choice were substantially more likely to rate the overall plan quality as good or excellent (OR = 2.09), more likely to think their doctor cared about them (OR = 1.54), less likely to experience a major problem with rules or delays in payment (OR = 0.43), and more likely to be satisfied with plan costs (OR = 1.35).

Neither the likelihood of rating the doctor's care as good or excellent nor that of having a problem with the plan's administration were affected by plan choice for the privately insured. With respect to satisfaction with both plan quality and plan cost, the privately insured with choice were substantially more likely to give a rating of good or excellent than those without choice (OR of 1.77 and 1.72, respectively).

Discussion and Summary

The results reported here add to the body of empirical work aimed at understanding how individuals select a health plan and the impact of increased choice of health plans on two outcomes of interest to policymakers—access and satisfaction. We find that the majority of low-income persons who chose a managed care plan based their choice on plan benefits or costs. The privately insured population was about equally split between these two reasons, and Medicaid enrollees were most concerned with benefits, probably because they are more insulated from cost-sharing requirements. Ability to remain with one's doctor or choose a particular doctor did not appear to be as important a response as one might expect given previous attention to this issue; this may be the result, at least in part, of this survey population consisting exclusively of low-income persons who are more focused on the basics of health insurance rather than the extras.

In terms of the effects on access and satisfaction, for all eight measures employed here, choice of plan had either a positive or neutral impact. For four of the eight access-insurance combinations (two measures for each insurance group), choice increased access to care. The effects on satisfaction were somewhat stronger in that choice appeared to enhance satisfaction in six of the eight possible cases (all four indicators for one insurance group and two of four for the other). We should note that there has been no effort in this study to examine the effect of choice of plan on total health care costs or health-status outcomes.

Our finding that short-term enrollees have somewhat worse access is worth noting. It is important to recognize that—to the extent that increases in choice involve more frequent plan changes—choice may have a deleterious effect on access through its effects on average length of time in plan. In other words, if choice decreases average plan tenure and those who have been in the plan for a shorter time have worse access, then this may be another aspect of choice that should be more closely considered. It may be that this problem will dissipate over time—as consumers become more knowledgeable about the available options, plan-switching may occur with less frequency. On the other hand, enrollment changes may continue both because employers will continue to change their offerings and competitive markets will change the array of plans in operation.

Several caveats should be mentioned. It is important to note that, as with previous studies, we have not identified the mechanism that links plan choice to better outcomes. One possible mechanism is the quality of the plans on the choice menu—we have not been able to control for differences in actual features or quality of the plans being offered and/or chosen. If, in fact, those with choice simply have “better” plans, then it is possible that people are more satisfied or have better access because they have “good” plans rather than because they have choice. If choice continues as a major policy focus, then future studies of plan choice should consider the plan not taken. Without more fully evaluating available options (i.e., features of the plans that were not selected), any conclusions drawn about the impact of choice are less than definitive.

We also examined differences (for each type of insurance) between those who exercised choice and those who did not. In terms of age, gender, education, and measured health status, there were no differences between these two groups. For both Medicaid enrollees and those with private insurance, persons with choice were more likely to be enrolled in a managed care plan than in FFS. Medicaid enrollees with choice (but not persons with private coverage) were more likely than those who had not exercised choice to have been enrolled in their plan for less than 2 years. The implications of short tenure in a plan have already been discussed. It is possible that there are other differences between those with choice and those without choice that would affect the relationship being examined here. For example, for the privately insured population, persons with choice are more likely to work for larger firms. To the extent that there are systematic differences between those who work for large and small firms and that these differences affect the relationship between choice and access/satisfaction, our results may be biased. Given the similarities observed among the groups and the homogeneity in terms of income, we would not expect these biases to be large.

Our findings indicate that, with respect to satisfaction, choice appears to have a more consistent effect for Medicaid enrollees than for the privately insured. This may be, in part, attributable to our classification of who has “no choice.” For the privately insured, the “no choice” variable comprises primarily persons whose employers have made only one plan available. For the Medicaid population, the “no choice” group includes those who reside in one of the States where Medicaid does not offer a choice of plan as well as those who are automatically assigned by the State—perhaps because they lacked the knowledge or motivation to choose a plan on their own. Thus, those who are currently choosing under Medicaid may be those most capable of making an appropriate selection, thereby increasing the odds of their being satisfied.

It would seem, however, that from a policy perspective, the end result of having no choice is what is of interest; we are, at least initially, trying to learn whether choice per se is a good thing. If we learn that this is indeed the case, then offering options should be encouraged for as many groups as can benefit by it. On the other hand, policymakers should recognize that there may be some persons who are unable to benefit from choice, either because they are unwilling or unable to choose effectively on their own.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared for the Kaiser/Commonwealth Low-Income Coverage and Access Project. Helpful comments were provided by Cathy Schoen of The Commonwealth Fund, Barbara Lyons of The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, and Harriet Komisar of the Georgetown University Institute for Health Care Research and Policy. The authors gratefully acknowledge the programming assistance of Elizabeth Dorosh and manuscript and table preparation of Janis Berman of the Project HOPE Center for Health Affairs.

Footnotes

Claudia L. Schur and Marc L. Berk are with Project HOPE Center for Health Affairs. Support for this research was provided by The Commonwealth Fund and The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation through the Georgetown University Institute for Health Care Research and Policy. The opinions presented here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of The Commonwealth Fund, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Project HOPE, or the Health Care Financing Administration.

Reprint Requests: Claudia L. Schur, Ph.D., Project HOPE Center for Health Affairs, 7500 Old Georgetown Road, Suite 600, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

References

- Agency for Health Care Policy & Research and The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Chart Pack, Americans as Health Care Consumers: The Role of Quality Information. Oct, 1996. Conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Berk ML, Schur CL. Measuring Access To Care: Improving Information For Policymakers. Health Affairs. 1998 Jan-Feb;17(1):180–186. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K, Collins KS, Schoen C, Morris C. Choice Matters: Enrollees' Views of their Health Plans. Health Affairs. 1995 Summer;14(2):99–112. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs DA, Sangl JA, Burrus B. Consumer Perspectives on Information Needs for Health Plan Choice. Health Care Financing Review. 1996 Fall;18(1):55–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M, Sparer M, Chu K. Medicaid Managed Care: Lessons From Five States. Health Affairs. 1996 Fall;15(3):153–166. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.15.3.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WH. Econometric Analysis. New York, NY.: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard J, Jewett J. Will Quality Report Cards Help Consumers? Health Affairs. 1997 May-Jun;16(3):218–228. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute (RTI), Health Economics Research (HER), and Benova. Information Needs For Consumer Choice Literature Review/Research Design. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1996. Report submitted to the Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Rice T, McCall N, Boismier JM. The Effectiveness of Consumer Choice in the Medicare Supplemental Health Insurance Market. Health Services Research. 1991 Jun;26(2):223–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon DP, Chernew M, Lave JR. Consumer Health Plan Choice: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Annual Review of Public Health. 1997;18:507–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS. SUDAAN User's Manual: Software for Analysis of Correlated Data, Release 6.4.0. Research Triangle Park, NC.: Research Triangle Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman R, Hill JW, Scheye EC, Spoeri RK. Satisfaction and Choice: A View from the Plans. Health Affairs. 1997 May-Jun;16(3):209–217. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Current Population Survey. Washington, DC.: 1994, 1995. [Google Scholar]