Abstract

Gastric cancer remains the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide. About half of the incidence of gastric cancer is observed in East Asian countries, which show a higher mortality than other countries. The effectiveness of 3 new gastric cancer screening techniques, namely, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, serological testing, and “screen and treat” method were extensively reviewed. Moreover, the phases of development for cancer screening were analyzed on the basis of the biomarker development road map. Several observational studies have reported the effectiveness of endoscopic screening in reducing mortality from gastric cancer. On the other hand, serologic testing has mainly been used for targeting the high-risk group for gastric cancer. To date, the effectiveness of new techniques for gastric cancer screening has remained limited. However, endoscopic screening is presently in the last trial phase of development before their introduction to population-based screening. To effectively introduce new techniques for gastric cancer screening in a community, incidence and mortality reduction from gastric cancer must be initially and thoroughly evaluated by conducting reliable studies. In addition to effectiveness evaluation, the balance of benefits and harms must be carefully assessed before introducing these new techniques for population-based screening.

Keywords: Gastric cancer screening, Mortality, Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, Upper gastrointestinal X-ray, Serum pepsinogen test, Helicobacter pylori antibody

Core tip: The effectiveness of new gastric cancer screening technique has remained limited to date. The present review of 3 new gastric cancer screening techniques, namely, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, serological testing, and “screen and treat” method provides invaluable insights on how screening tests should be instituted. To effectively introduce new techniques for gastric cancer screening in a community, incidence and mortality reduction from gastric cancer must be initially and thoroughly evaluated by conducting reliable studies. In addition to effectiveness evaluation, the balance of benefits and harms must be assessed before introducing these new techniques for population-based screening.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer remains the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Over the last 3 decades, the incidence of gastric cancer has decreased around the world, and a similar trend can be observed in Asian countries. However, although mortality from gastric cancer has markedly improved, its burden remains substantial.

In 2012, an estimated 1 million new cases of gastric cancer have occurred, with half of the world total occurring in Eastern Asia[1]. The age-standardized incidence rates are about three times as high in men as in women; 35.4 for 100000 men and 13.8 for 100000 women in the world. The highest mortality rates are observed in Eastern Asia, occurring at 24.0 per 100000 men and 9.8 per 100000 women.

In Japan, there are more than 360000 cancer deaths, with gastric cancer accounting for 13.6% of the total number of cancer deaths[2]. In 2012, the reported age-standardized mortality rate of gastric cancer was 17.6 per 100000 men and 6.7 per 100000 women. Over the last 2 decades, the cancers causing mortality have changed. Particularly, mortality from gastric cancer in men has decreased. In 2005, the gastric cancer mortality rate was half that in 1975.

HISTORY OF GASTRIC CANCER SCREENING

Gastric cancer screening using upper gastrointestinal series (radiographic screening), which was developed in Japan, has been conducted since the 1960s[3]. In 1983, nationwide cancer screening programs were started under the Health Service Law for the Aged. These programs have been conducted as a public policy for the last 3 decades. In 2000, Hisamichi[4] assessed the effectiveness of radiographic screening based on a literature review, and they recommended this screening technique in their report. In 2005, the Japanese guidelines for gastric cancer screening also recommended radiographic screening based on a systematic review[5]. In the guidelines, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and serological testing [i.e., Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) antibody and serum pepsinogen screening] were also evaluated. These were not, however, recommended because of insufficient evidence.

Since the introduction of population-based screening, radiographic equipment has been improved and radiation exposure has gradually decreased. In the last decade, filming has efficiently progressed to digital imaging. High-density barium has been used for radiographic screening in the 2000s. Compared with previous techniques, the sensitivities of new screening techniques remain equal, but their specificities have seen a considerable improvement[6]. Although radiographic screening has been conducted in most municipalities in Japan, the screening rate has gradually decreased nationwide over the last decade[7]. On the other hand, endoscopic screening has been performed in clinical settings as opportunistic screening[8-10]. The serum pepsinogen method has been used mainly in clinical settings with multiphasic health check-ups[11-13], but the use of this method has been limited to communities[14,15].

In other Asian countries, gastric cancer screening using both methods has been performed as opportunistic screening[16]. Both radiographic screening and radiographic screening and endoscopic screening has been introduced as national programs since 2000 in South Korea[17]. Although the target age group is the same as in Japan, the screening interval is every 2 years in South Korea. People can choose the screening method at their own preference, and a high selection preference for endoscopic screening has been observed.

CURRENT STATUS OF GASTRIC CANCER SCREENING IN JAPAN

Five cancers, namely, stomach, colon and rectum, lung, breast and cervical cancer have been screened by nationwide screening programs in Japan. The results of population-based screening are shown in Table 1[7]. Interestingly, the rate of gastric cancer screening has been shown to be lower than that of other organs, although the rates of all cancer screening programs are below 25%. Since the introduction of gastric cancer screening in 1983, the screening rate has gradually decreased and remained at about 10%. Except for cervical cancer, the target groups in these screening programs are individuals 40 years and over. There is no upper age limit in these programs and individuals over 70 years have constituted about 35% of the participants in gastric cancer screening. The screening interval for gastric, colorectal, and lung cancer is every year. For gastric cancer screening, about 4 million people participate each year. The positive rate is about 10% and further examination is needed for definitive diagnosis. The participant rate of diagnostic examinations is approximately 80% and is higher than that for colorectal cancer screening. There were 6769 newly detected gastric cancers in 2011. However, the detection rate in gastric cancer screening has remained at 0.1% to 0.2%.

Table 1.

Results of population-based screening in Japan

| Stomach | Colon and rectum | Lung | Breast | Cervix | |

| Total participants | 3874128 | 6975281 | 7059318 | 2541993 | 4666826 |

| Screening rate | 9.6% | 16.8% | 17.2% | 18.8% | 23.7% |

| Positive rate | 9.4% | 7.3% | 2.8% | 8.6% | 1.6% |

| Participant rate of diagnostic examination | 81.1% | 63.6% | 77.7% | 83.5% | 66.2% |

| Cancer detection rate | 0.17% | 0.23% | 0.06% | 0.32% | 0.08% |

| Positive predictive value | 1.9 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 4.9 |

Adapted from reference [7].

There are several problems with the continued use of nationwide radiographic screening in Japan. The upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) with double-contrast study was originally adopted for radiographic screening. Special training is needed for the interpretation of UGI radiographs in gastric cancer screening. The use of UGI has now seen a rapid decrease in the clinical setting and is presently replaced by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, which becomes a requisite technique for general physicians, particularly for the young generation. Inadequate manpower for radiographic screening will become evident in the future because of the advanced age of experts who can interpret UGI radiographs. Since the burden of gastric cancer still remains substantial, new techniques, including endoscopy, serological tests for H. pylori antibody and serum pepsinogen, a maker of atrophy have been anticipated for gastric cancer screening. A “screen and treat” strategy is also anticipated for H. pylori eradication and surveillance for the high-risk group.

NEW CANCER SCREENING METHODS

Endoscopic screening

Endoscopic screening for gastric cancer was not recommended in the 2005 version of the Japanese guidelines[5]. Although new studies have been reported since the publication of the Japanese guidelines, these studies were insufficient to validate the effectiveness of endoscopic screening[8-9,18-20]. Endoscopic screening has been performed in 18.3% of municipalities as population-based screening in Japan[21]. Several studies have reported that endoscopic screening has a higher detection rate than radiographic screening[8-10]. Endoscopic screening can detect cancer earlier which can be adopted for endoscopic submucosal resection.

A comparison of the sensitivity of endoscopic and radiographic screenings has been reported[22,23]. In a Korean study, the sensitivity of endoscopic screening was reported as 69.4% (95%CI: 66.4-72.4) for the first round and 66.9% (95%CI: 59.8-74.0) for the subsequent round[23]. On the other hand, the sensitivity of radiographic screening was reported as 38.2% (95%CI: 35.9-40.5) for the first round and 27.3% (95%CI: 22.6-32.0) for the subsequent round[23]. Although the definition of interval cancer was different between South Korea and Japan, the sensitivity of endoscopic screening was always higher than that of radiographic screening. However, there are possibilities of an increase in the frequency of overdiaganosis by endoscopic screening because it can detect cancer earlier than radiographic screening. Although the detection method is commonly used to measure the sensitivity of the screening method, it cannot exclude cases of overdiagnosis. The incidence method was developed to calculate sensitivity, avoiding cases of overdiaganosis[24]. Screening for breast, lung, and colorectal cancers has been evaluated using the incidence method[25-27]. In a Japanese study, the sensitivities of endoscopic and radiographic screening were calculated by both methods[22] (Table 2). By the detection method, it was found that the sensitivity of endoscopic screening was higher than that of radiographic screening in both rounds (prevalence screening: P = 0.255, incidence screening: P = 0.043). By the incidence method, the sensitivity of endoscopic screening for prevalence and incidence screenings was also higher than that of radiographic screening (prevalence screening: P = 0.626, incidence screening: P = 0.117). Even if the incidence method is used, the sensitivity of endoscopic screening was always higher than that of radiographic screening in both rounds.

Table 2.

Sensitivity of endoscopy and radiography for gastric cancer screening

| Screening round | Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity |

| By the detection method | By the detection method | By the incidence method | ||

| Prevalence screening | Endoscopic screening | 0.955 | 0.851 | 0.886 |

| (0.875-0.991) | (0.843-0.859) | (0.698-0.976) | ||

| Radiographic screening | 0.893 | 0.856 | 0.831 | |

| (0.718-0.977) | (0.846-0.865) | (0.586-0.964) | ||

| Incidence screening | Endoscopic screening | 0.977 | 0.888 | 0.954 |

| (0.919-0.997) | (0.883-0.892) | (0.842-0.994) | ||

| Radiographic screening | 0.885 | 0.891 | 0.855 | |

| (0.664-0.972) | (0.885-0.896) | (0.637-0.970) |

Adapted from reference [22].

Recently, the results of a community-based case-control study of endoscopic screening have been reported[28,29]. Based on the results of a larger case-control study, the findings suggest a 30% reduction in gastric cancer mortality by endoscopic screening compared with no screening within 36 mo before the date of diagnosis of gastric cancer[28]. Although the sample size is small in the Nagasaki study, a higher mortality reduction from gastric cancer by 80% was reported[29]. Although these results suggest that gastric cancer mortality could be reduced by endoscopic screening, prudence must be observed in interpreting positive results because these case-control studies may have included self-selection bias.

TARGETING THE HIGH-RISK GROUP

Although serologic testing has been used for targeting the high-risk group for gastric cancer, the effectiveness of these screenings has not been fully clarified. A small case-control study reported mortality reduction from gastric cancer using serum pepsinogen screening[30]; however, this screening is insufficient to confirm the effectiveness of serological testing. In a meta-analysis by Dinis-Ribeiro et al[31], they found that the sensitivity of serum pepsinogen screening for gastric cancer was 77% and that the specificity was 73% using pepsinogen I ≤ 70 and pepsinogen I/II ratio ≤ 3 as cut-off values for atrophy. Since high specificity is a major requirement for cancer screening[32], tests with lower specificity such as serum pepsinogen testing are not suitable for primal screening.

The 3 current serological screening methods commonly used to identify the high-risk group are as follows: (1) serum pepsinogen screening; (2) H. pylori antibody screening; and (3) a combination of the serum pepsinogen and H. pylori antibody screening. Although cytotoxin associated gene A (cagA) has also been anticipated as a new biomarker for gastric cancer, its use has been limited to research-based screening[33]. Most of the reported studies are cross-sectional studies in which the serologic test was performed simultaneously with upper endoscopic screening. Although several studies have been reported from European countries, their outcomes were mainly for chronic atrophic gastritis which is a surrogate endpoint even if it can be a precursor of gastric cancer[33-35]. Lomba-Viana et al[36] previously reported the results of a 5-year follow-up study of the serum pepsinogen test for the early detection of gastric cancer in Portugal. The constraint of their study was that the subjects were limited only to 4% of the primary subjects who were screened by the serum pepsinogen tests. For the successful introduction of a screening procedure for population-based screening, a direct evaluation of the reduction in gastric cancer incidence is required. Therefore, a long-term follow-up for the whole target population is needed to evaluate the possibility of predicting the incidence of gastric cancer.

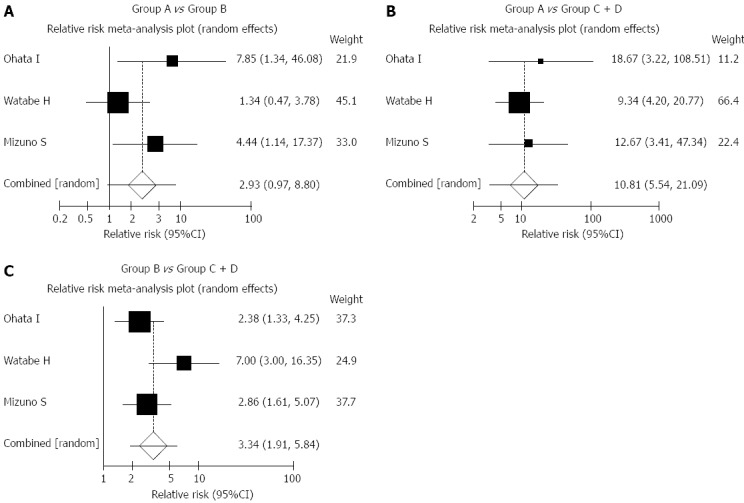

At present, the most commonly used strategy for serologic testing is a combination of serum pepsinogen and H. pylori antibody screening, or the so-called “ABC method”[37]. This combination method has been most anticipated since it can theatrically stratify the risk of gastric cancer. However, the effects of long-term follow-up have not yet been clarified. Thus far, there are 3 studies on predicting the incidence of gastric cancer based on long-term follow-up[38-40]. In all of these studies, the follow-up periods were less than 10 years. Moreover, the incidence rates of gastric cancer were different among these studies (Table 3). The 4 groups identified on the basis of serum pepsinogen and H. pylori infections were as follows: Group A = negative H. pylori infection and negative atrophy; Group B = positive H. pylori infection and negative atrophy; Group C = positive H. pylori infection and positive atrophy; Group D = negative H. pylori infection and positive atrophy. As shown in Figure 1, a meta-analysis was conducted on the base of the results of these studies using a random effect model by Stats Direct3 (Stats Direct Ltd. Cheshire United Kingdom). Although there was no cancer in group A in Wakayama study by Ohata et al[38], it assumed that there was 1 cancer in group A in this study for meta-analysis. Because of the small number of group D, groups C and D were combined. Although the risk of gastric cancer of group C + D was higher than that of group A [relative risk (RR) = 10.81, 95%CI: 5.54-21.09], the difference in gastric cancer risk between group A and group B cannot be identified (RR = 2.93, 95%CI: 0.97-8.80). Group C + D was clearly divided by group B (RR = 3.34, 95%CI: 1.91-5.84). Although serologic testing could be used to detect the high-risk group for gastric cancer, the exclusion of the low-risk group remains difficult. Gastric cancer usually developed during the follow-up even in individuals localized to Group A by the first testing.

Table 3.

Results of prediction based on a combination of Helicobacter pylori antibody and serum pepsinogen screening

| Ohata et al[38] | Watabe et al[40] | Mizuno et al[39] | |

| Basic characteristics | |||

| Year published | 2004 | 2005 | 2009 |

| Location | Wakayama | Chiba | Kyoto |

| Total number | 4655 | 6983 | 2859 |

| Men/Women | 4655/0 | 3320/2260 | 1011/1848 |

| Age | 48.3 (average) | 48.9 (average) | ≥ 35 |

| Follow-up (yr) | 7.7 (average) | 4.7 (average) | 10 (maximum) |

| HP positive rate (%) | 78.6 | 46.1 | 75 |

| PG positive rate (%) | 28.9 | 21.8 | 39.2 |

| Number of detected cancer | 45 | 43 | 61 |

| Incidence of gastric cancer (/1000) | 9.67 | 6.16 | 21.3 |

| HP-/PG- | |||

| Total number | 967 | 3324 | 647 |

| Number of detected cancer | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| Incidence of gastric cancer (/1000) | - | 2.11 | 3.09 |

| HP+/PG- | |||

| Total number | 2341 | 2134 | 1094 |

| Number of detected cancer | 19 | 6 | 15 |

| Incidence of gastric cancer (/1000) | 8.12 | 2.81 | 13.71 |

| HP+/PG+ | |||

| Total number | 1316 | 1082 | 1054 |

| Number of detected cancer | 24 | 18 | 41 |

| Incidence of gastric cancer (/1000) | 18.24 | 16.64 | 38.9 |

| HP-/PG+ | |||

| Total number | 31 | 443 | 69 |

| Number of detected cancer | 2 | 12 | 3 |

| Incidence of gastric cancer (/1000) | 64.52 | 27.09 | 43.48 |

HP: Helicobacter pylori antibody; PG: Serum pepsinogen.

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of 3 studies predicting gastric cancer risk. Meta-analysis was conducted on the base of the results of previous studies using the random effect model by Stats Direct3 (Stats Direct Ltd. Cheshire United Kingdom). Subjective studies are shown in Table 3. Although there is no cancer in group A in the Wakayama study by Ohata et al[38], it assumed that three was 1 cancer in group A in this study for meta-analysis. Because of the small number of group D, groups C and D were combined. The relative risk of group B was calculated and referred to that of group A. The relative risk of group C + D were calculated and referred to those of group A and group B.

A serum pepsinogen I value of ≤ 70 mL and a serum pepsinogen I/II ratio of ≤ 3.0 are defined as the criteria for atrophy in Japan[11,12]. Yanaoka et al[41] reported that gastric cancer incidence differs when a criterion of the serum pepsinogen cut-off value was changed. The risk of gastric cancer development remains in long-term follow-up even if the results were negative on the basis of the standard cut-off values.

The Japanese government has decided to adopt H. pylori eradication for chronic gastritis under the national fee schedule for all types of health insurance in 2013. H. pylori eradication has rapidly expanded after this adoption, and patients receiving treatment are now classified under the “pseudo low-risk group” both for atrophy and H. pylori infection. In such a setting, it has become difficult to stratify gastric cancer risk by serologic testing.

“SCREEN AND TREAT” METHOD

A chemoprevention program has been highly anticipated for the community with high incidence of gastric cancer. However, randomized controlled trials of H. pylori eradication for asymptomatic patients have not so far identified a significant reduction in gastric cancer[42,43]. In 2004, the “screen and treat” program was introduced on the Matsu Island, Taiwan, which has a high incidence of gastric cancer[44]. Compared before the introduction of this program, the incidence of gastric cancer has been reduced by 25% during the “screen and treat” period (rate ratio = 0.753; 95%CI: 0.372-1.524). However, the effects of cancer screening are not to be expected within a short period of time after its introduction[45]. A long-term follow-up is needed to evaluate the reduction of incidence and mortality from gastric cancer by the “screen and treat” method.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

In the development of a new cancer screening technique and in its actual introduction, a step-by-step evaluation is required. In line with this, Pepe et al[32] proposed a strategic process for biomarker development for cancer screening. This process was conceptualized in 5 phases: Phase 1 (Preclinical exploratory), Phase 2 (Clinical assay and validation), Phase 3 (Retrospective longitudinal), Phase 4 (Prospective screening), and Phase 5 (Cancer control) (Table 4). These phases can be useful in the development of a new cancer screening technique. After validation in the clinical setting in Phases 2 and 3, additional studies on cancer screening are required in Phases 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Biomarker development process

| Phase No. | Aim | Detail |

| Phase 1 | Preclinical Exploratory | Promising directions identified |

| Phase 2 | Clinical Assay and Validation | Clinical assay detects established disease |

| Phase 3 | Retrospective Longitudinal | Biomarker detects disease early before it becomes clinical and a “screen positive” rule is defined |

| Phase 4 | Prospective Screening | Extent and characteristics of disease detected by the test and the false referral rate are identified |

| Phase 5 | Cancer Control | Impact of screening on reducing the burden of disease on the population is quantified |

Adapted from reference [32].

Maintaining a high specificity is a major priority for population-based screening because a false-positive rate translates into a large number of people subjected to unnecessary diagnostic examinations. Even if a high sensitivity could be obtained in Phase 3, the target population is different in cancer screening. In Phase 4, the operating characteristics of the new biomarker-based screening in a relevant population and the false referral rate should be determined. Finally, cancer mortality reduction must be evaluated by the new screening technique.

Sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic screening have already been evaluated in South Korea and Japan. Although mortality reduction from endoscopic screening has been reported in several studies, the results remain insufficient to confirm its effectiveness. Research on endoscopic screening is on its way to Phase 5 (Table 4). On the other hand, serological testing is on its way only to Phases 3-4 because of lack of studies to evaluate the incidence and mortality reduction from gastric cancer. The “screen and treat” method has been limited to Phases 4-5 because evaluation study has been limited in the Matsu Island. Therefore, new techniques for gastric cancer screening needs to be further developed, with their effectiveness assessed in Phases 4 and 5.

To effectively introduce new techniques for gastric cancer screening in a community, incidence and mortality reduction from gastric cancer must be evaluated by conducting reliable studies. In addition to evaluating effectiveness, the balance of benefits and harms must also be carefully assessed before introducing population-based screening.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Ms. Kanoko Matsushima and Ms. Junko Asai for secretarial work. I am also grateful to Dr. Edward F. Barroga for the editorial review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant-in-Aid for H22-Third Term Comprehensive Control Research for Cancer 022 from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

P- Reviewer: Balaban YH, Chmiela M, Federico A, Velayos B S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2012Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/

- 2.National Cancer Center. Center for Cancer Control and Information Services. Available from: http://ganjoho.ncc.go.jp/professional/statistics/index.html.

- 3.Oshima A. A critical review of cancer screening programs in Japan. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1994;10:346–358. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300006590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hisamichi S. Guidelines for cancer screening Programs. Tokyo: Japan Public Health Association; 2000. p. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamashima C, Shibuya D, Yamazaki H, Inoue K, Fukao A, Saito H, Sobue T. The Japanese guidelines for gastric cancer screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:259–267. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka M, Matsuda K. Comparisons of the accuracies of conventional and new X-ray methods for gastric cancer screening using the regional cancer registry. J Gastroenterol Mass Sur. 2013;51:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health, Welfare and Labour. The report of Health Promotion and Community Health 2011. Available from: http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/GL08020103.do?_toGL08020103_&listID=000001106953&disP = Other&requestSender=dsearch.

- 8.Ogoshi K, Narisawa R, Kato T, Fujita K, Sano M. Endoscopic screening for gastric cancer in Niigata City. Jpn J Endosc Forum Dig Dis. 2010;26:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsumoto S, Yamasaki K, Tsuji K, Shirahama S. Results of mass endoscopic examination for gastric cancer in Kamigoto Hospital, Nagasaki Prefecture. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4316–4320. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i32.4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shabana M, Hamashima C, Nishida M, Miura K, Kishimoto T. Current status and evaluation of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. Jpn J Cancer Det Diag. 2010;17:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miki K, Ichinose M, Kawamura N, Matsushima M, Ahmad HB, Kimura M, Sano J, Tashiro T, Kakei N, Oka H. The significance of low serum pepsinogen levels to detect stomach cancer associated with extensive chronic gastritis in Japanese subjects. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1989;80:111–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1989.tb02276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miki K, Ichinose M, Ishikawa KB, Yahagi N, Matsushima M, Kakei N, Tsukada S, Kido M, Ishihama S, Shimizu Y. Clinical application of serum pepsinogen I and II levels for mass screening to detect gastric cancer. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1993;84:1086–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1993.tb02805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohata H, Oka M, Yanaoka K, Shimizu Y, Mukoubayashi C, Mugitani K, Iwane M, Nakamura H, Tamai H, Arii K, et al. Gastric cancer screening of a high-risk population in Japan using serum pepsinogen and barium digital radiography. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:713–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watase H, Inagaki T, Yoshikawa I, Furihata S, Watanabe Y, Miki K. Five years follow up study of gastric cancer screening using the pepsinogen test method in Adachi city. J Jpn Assoc Cancer Det Diag. 2004;11:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito F, Watanabe Y, Miki K. Effect of two-step serum pepsinogen test method of reducing stomach cancer mortality among the urban residents. J Jpn Assoc Cancer Det Diag. 2007;14:156–160. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung WK, Wu MS, Kakugawa Y, Kim JJ, Yeoh KG, Goh KL, Wu KC, Wu DC, Sollano J, Kachintorn U, Gotoda T, Lin JT, You WC, Ng EK, Sung JJ; Asia Pacific Working Group on Gastric Cancer. Screening for gastric cancer in Asia: current evidence and practice. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:279–287. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y, Jun JK, Choi KS, Lee HY, Park EC. Overview of the National Cancer screening programme and the cancer screening status in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosokawa O, Miyanaga T, Kaizaki Y, Hattori M, Dohden K, Ohta K, Itou Y, Aoyagi H. Decreased death from gastric cancer by endoscopic screening: association with a population-based cancer registry. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1112–1115. doi: 10.1080/00365520802085395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosokawa O, Hattori M, Takeda T. Decrease in the rate of gastric cancer death due to repeated endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Cancer Screen. 2008;46:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosokawa O, Shimbo T, Matsuda K, Mayanaga T. Impact of opportunistic endoscopic screening on the decrease of mortality from gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Cancer Screen. 2011;49:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health, Welfare and Labour. The report of cancer screening implementation in 2011, Report of implementation of cancer screening, 2013. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file.jsp?id=147922&name=0000013913.pdf.

- 22.Hamashima C, Okamoto M, Shabana M, Osaki Y, Kishimoto T. Sensitivity of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer by the incidence method. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:653–659. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi KS, Jun JK, Park EC, Park S, Jung KW, Han MA, Choi IJ, Lee HY. Performance of different gastric cancer screening methods in Korea: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Day NE. Estimating the sensitivity of a screening test. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1985;39:364–366. doi: 10.1136/jech.39.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fletcher SW, Black W, Harris R, Rimer BK, Shapiro S. Report of the International Workshop on Screening for Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1644–1656. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.20.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zappa M, Castiglione G, Paci E, Grazzini G, Rubeca T, Turco P, Crocetti E, Ciatto S. Measuring interval cancers in population-based screening using different assays of fecal occult blood testing: the District of Florence experience. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toyoda Y, Nakayama T, Kusunoki Y, Iso H, Suzuki T. Sensitivity and specificity of lung cancer screening using chest low-dose computed tomography. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1602–1607. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamashima C, Ogoshi K, Okamoto M, Shabana M, Kishimoto T, Fukao A. A community-based, case-control study evaluating mortality reduction from gastric cancer by endoscopic screening in Japan. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumoto S, Yoshida Y. Efficacy of endoscopic screening in an isolated island: a case-control study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014;33:46–49. doi: 10.1007/s12664-013-0378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshihara M, Hiyama T, Yoshida S, Ito M, Tanaka S, Watanabe Y, Haruma K. Reduction in gastric cancer mortality by screening based on serum pepsinogen concentration: a case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:760–764. doi: 10.1080/00365520601097351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinis-Ribeiro M, Yamaki G, Miki K, Costa-Pereira A, Matsukawa M, Kurihara M. Meta-analysis on the validity of pepsinogen test for gastric carcinoma, dysplasia or chronic atrophic gastritis screening. J Med Screen. 2004;11:141–147. doi: 10.1258/0969141041732184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, Potter JD, Thompson ML, Thornquist M, Winget M, Yasui Y. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1054–1061. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adamu MA, Weck MN, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Incidence and risk factors for the development of chronic atrophic gastritis: five year follow-up of a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1652–1658. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Filomena A, Saieva C, Lucchetti V, Santacroce F, Falorni P, Francini V, Carrieri P, Zini E, Ridolfi B, Belli P, et al. Gastric cancer surveillance in a high-risk population in tuscany (Central Italy): preliminary results. Digestion. 2011;84:70–77. doi: 10.1159/000322689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dinis-Ribeiro M, Lopes C, da Costa-Pereira A, Guilherme M, Barbosa J, Lomba-Viana H, Silva R, Moreira-Dias L. A follow up model for patients with atrophic chronic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:177–182. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.11270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lomba-Viana R, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Fonseca F, Vieira AS, Bento MJ, Lomba-Viana H. Serum pepsinogen test for early detection of gastric cancer in a European country. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:37–41. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834d0a0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inoue K, Fujisawa T, Haruma K. Assessment of degree of health of the stomach by concomitant measurement of serum pepsinogen and serum Helicobacter pylori antibodies. Int J Biol Markers. 2011;25:207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohata H, Kitauchi S, Yoshimura N, Mugitani K, Iwane M, Nakamura H, Yoshikawa A, Yanaoka K, Arii K, Tamai H, et al. Progression of chronic atrophic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection increases risk of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:138–143. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizuno S, Miki I, Ishida T, Yoshida M, Onoyama M, Azuma T, Habu Y, Inokuchi H, Ozasa K, Miki K, et al. Prescreening of a high-risk group for gastric cancer by serologically determined Helicobacter pylori infection and atrophic gastritis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3132–3137. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watabe H, Mitsushima T, Yamaji Y, Okamoto M, Wada R, Kokubo T, Doi H, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Omata M. Predicting the development of gastric cancer from combining Helicobacter pylori antibodies and serum pepsinogen status: a prospective endoscopic cohort study. Gut. 2005;54:764–768. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.055400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yanaoka K, Oka M, Mukoubayashi C, Yoshimura N, Enomoto S, Iguchi M, Magari H, Utsunomiya H, Tamai H, Arii K, et al. Cancer high-risk subjects identified by serum pepsinogen tests: outcomes after 10-year follow-up in asymptomatic middle-aged males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:838–845. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, Bravo LE, Ruiz B, Zarama G, Realpe JL, Malcom GT, Li D, Johnson WD, et al. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti-helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, Lai KC, Hu WH, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Fong DY, Ho J, Ching CK, Chen JS; China Gastric Cancer Study Group. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee YC, Chen TH, Chiu HM, Shun CT, Chiang H, Liu TY, Wu MS, Lin JT. The benefit of mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: a community-based study of gastric cancer prevention. Gut. 2013;62:676–682. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Conell-Price J, O’Brien S, Walter LC. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ. 2013;346:e8441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]