Abstract

AIM: To investigate the benefits of endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) before stent placement by meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

METHODS: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Science Citation Index databases up to March 2014 were searched. The primary outcome was incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) and successful stent insertion rate. The secondary outcomes were the incidence of post-ERCP bleeding, stent migration and occlusion. The free software Review Manager was used to perform the meta-analysis.

RESULTS: Three studies (n = 338 patients, 170 in the EST group and 168 in the non-EST group) were included. All three studies described a comparison of baseline patient characteristics and showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups. Three RCTs, including 338 patients, were included in this meta-analysis. Most of the analyzed outcomes were similar between the groups. Although EST reduced the incidence of PEP, it also led to a higher incidence of post-ERCP bleeding (OR = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.12-0.93, P = 0.04; OR = 9.70, 95%CI: 1.21-77.75, P = 0.03, respectively).

CONCLUSION: EST before stent placement may be useful in reducing the incidence of PEP. However, EST-related complications, such as bleeding and perforation, may offset this effect.

Keywords: Biliary stent, Endoscopic sphincterotomy, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Malignant biliary obstruction

Core tip: It is unclear whether patients with malignant biliary obstruction who receive stent placement benefit from endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST). The present meta-analysis was performed to investigate the clinical outcomes of patients who did and did not undergo EST before stent placement.

INTRODUCTION

Malignant biliary obstruction is often caused by pancreatic carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma and metastatic disease. The majority of these patients will require non-surgical treatment because of the advanced nature of the disease or significant co-morbidity associated with surgery[1]. A biliary stent is often the only feasible therapeutic option for such patients. Some studies have reported the effectiveness of endoscopic biliary stent placement in relieving jaundice and improving quality of life[2,3]. Currently, there is still controversy regarding the use of endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) before the placement of biliary stents. The idea of carrying out EST before stent insertion may stem from previous studies that suggested that the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) may be lower[4,5] and stent placement may be easier[6]. However, EST may pose several risks, especially bleeding and perforation, even when performed by experienced endoscopists[7]. Therefore, it is unclear whether patients with malignant biliary obstruction who receive stent placement benefit from EST. The present meta-analysis was performed to investigate the clinical outcomes of patients who did and did not undergo EST before stent placement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

Electronic databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library and the Science Citation Index up to March 2014, were searched. Literature references were hand-searched during the same period. The search terms used were “stent or endoprosthesis and endoscopic sphincterotomy”.

Study selection

The initial inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) RCTs irrespective of blinding used or not; (2) the treatment group received biliary stenting with EST; and (3) a parallel control group received biliary stenting without EST. Studies that met the initial inclusion criteria were further examined. Those with duplicate publications, unbalanced matching procedures or incomplete data were excluded. When publication duplication occurred, or the studies were reported in conference proceedings, the earliest publications were excluded.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (Cui PJ and Yao J) independently extracted the data according to the prescribed selection criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers. The following data were extracted: the baseline trial data (e.g., mean age, gender, primary disease, type of stent and interventions during stent deployment); and the outcomes of ERCP (incidence of PEP and successful stent insertion rate, the incidence of post-ERCP bleeding, and stent migration and occlusion). Wherever necessary, the corresponding authors were contacted to obtain supplementary information.

Study quality

The Jadad composite scale[8] assessed the quality of the included trials in addition to a description of an adequate method for allocation concealment. The Jadad score assesses descriptions of randomization, double-blinding, and withdrawals or dropouts. It ranges from 0-5 points, with a low-quality study having a score of ≤ 2 and a high-quality study having a score of ≥ 3[9]. Two authors (Cui PJ and Yao J) independently assessed the quality if the studies, and any discrepancies in interpretation were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using the free software Review Manager (Version 4.2.10, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). Differences observed between the two groups were expressed as the OR with a 95%CI. A fixed effects model was used to pool data when statistical heterogeneity was absent. If statistical heterogeneity was present (P < 0.05), a random effects model was used.

RESULTS

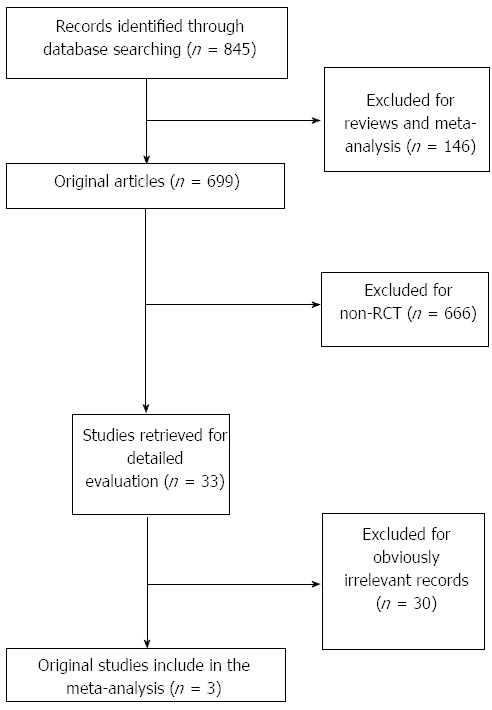

Three studies (n = 338 patients, 170 in the EST group and 168 in the non-EST group) were included; all were published in English (Figure 1). Tables 1 and 2 show the clinical details for each trial. All three studies described a comparison of baseline patient characteristics and showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups. Table 3 presents the quality analysis of the included trials. The outcomes were measured as follows.

Figure 1.

Search protocol for the meta-analysis. RCT: Randomized controlled trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included trials in the meta-analysis

| Ref. | Definition of | Group | Age (yr) |

Diagnosis (n) |

Gender | Endoscopist | Type of | Sedation | Prophy | ||

| complications | Pancreatic | Cholangio- | Others | (M/F) | stent | lactic | |||||

| cancer | carcinoma | antibiotics | |||||||||

| Giorgioet al[10] | According to the criteria of Cotton et al[32] | EST | 72 ± 6 | 64 | 31 | 1 | 51/35 | Two experienced endoscopists | Plastic stent | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Non-EST | 75 ± 6 | 67 | 28 | 1 | 47/39 | ||||||

| Artifon et al[11] | According to the criteria of Cotton et al[32] | EST | 72.1 | 30 | 0 | 7 | 18/19 | Three experienced endoscopists | Covered SEMS | Midazolam and fentanyl | Before ERCP |

| Non-EST | 65.4 | 30 | 0 | 7 | 12/25 | ||||||

| Zhou et al[12] | According to the criteria of Cotton et al[32] | EST | 65.1 ± 9.5 | 11 | 26 | 4 | 24/17 | Two experienced endoscopists | Uncovered SEMS | Not mentioned | During ERCP |

| Non-EST | 64.0 ± 7.5 | 10 | 27 | 4 | 23/18 | ||||||

SEMS: Self-expandable metal stent; EST: Endoscopic sphincterotomy; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Table 2.

Characteristics of randomized comparisons of endoscopic sphincterotomy and non-endoscopic sphincterotomy groups n (%)

| Ref. | Group | Successful stent insertion | Pancreatitis | Bleeding | Acute cholangitis | Stent occlusion | Stentmigration | Duodenal perforation |

| Giorgio et al[10] | EST | 92 (95.8) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.3) | NR | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.3) | NR |

| Non-EST | 90 (93.7) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.3) | |||

| Artifon et al[11] | EST | 37 (100) | 0 (0) | 5 (13.5) | NR | 3 (8.1) | 6 (16.2) | 4 (10.8) |

| Non-EST | 37 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Zhou et al[12] | EST | 41 (100) | 4 (9.8) | NR | 24 (58.5) | 5 (12.2) | NR | NR |

| Non-EST | 41 (100) | 13 (31.7) | 13 (31.7) | 4 (9.8) |

NR: Not reported; EST: Endoscopic sphincterotomy.

Table 3.

Quality analysis of the included trials

Primary outcome

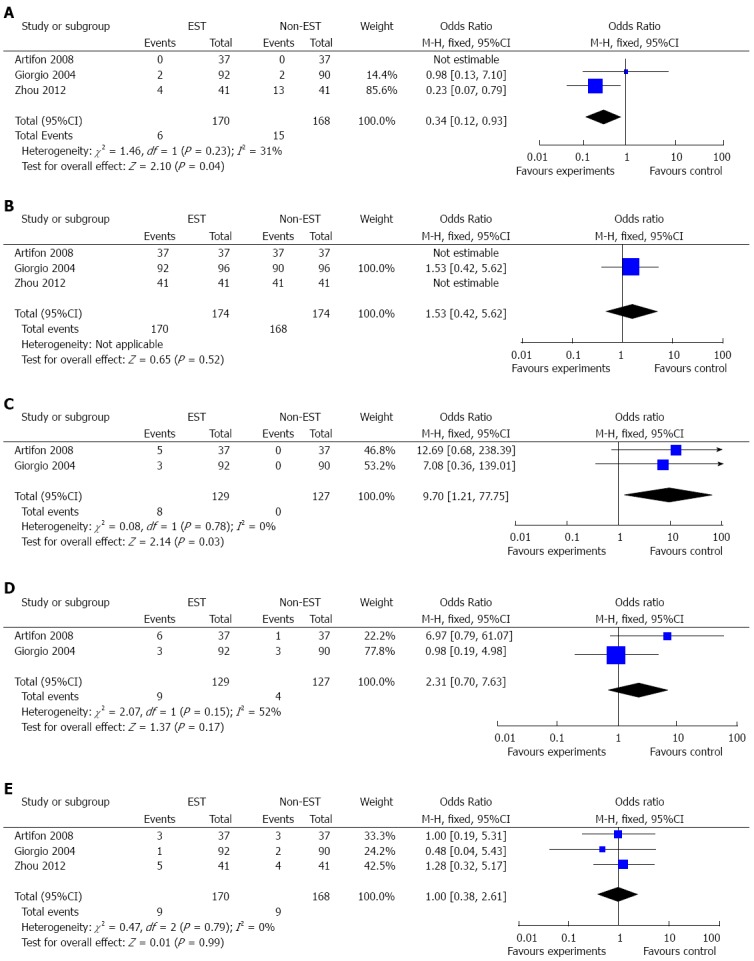

The purpose of performing EST before stent placement is to lower the incidence of PEP and to make stent insertion easier.; therefore, we considered the rates of PEP and successful stent insertion to be the primary outcomes. All three studies[10-12] reported these data, and 170 patients received EST and 168 were allocated to the non-EST group. A comparison of PEP between the groups showed that the incidence was significantly lower with EST than without EST [6/170 (3.5%) vs 15/168 (8.9%), P = 0.04, OR = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.12-0.93] (Figure 2A). No significant difference in the rate of successful stent insertion was observed between the two groups [170/174 (97.7%) vs 168/174 (96.6%), P = 0.52, OR = 1.53, 95%CI: 0.42-5.62] (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Forest plot. A: Comparison of the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) between the endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) and non-EST groups; B: Comparison of the rate of successful stent insertion between the EST and non-EST groups; C: Comparison of the rate of post-ERCP bleeding between the EST and non-EST groups; D: Comparison of the rate of stent migration between the EST and non-EST groups; E: Comparison of the rate of stent occlusion between the EST and non-EST groups.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were the incidence of post-ERCP bleeding, stent migration and occlusion. The post-ERCP bleeding rate was derived from two RCTs[10,11]. These trials included 256 patients, 129 of whom received EST. Eight patients experienced bleeding after ERCP, and all were in the EST group. The incidence was significantly higher in this group [8/129 (6.2%) vs 0/127 (0%), P = 0.03, OR = 9.70, 95%CI: 1.21-77.75] (Figure 2C). Two RCTs[10,11] reported 13 cases of stent migration, of whom nine received EST. There was no significant difference between the two groups [9/129 (7.0%) vs 4/127(3.1%), P = 0.17, OR = 2.31, 95%CI: 0.70-7.63] (Figure 2D). Three RCTs[10-12] reported 18 cases of stent occlusion, nine of which received EST. There was no significant difference between the two groups [9/170 (5.3%) vs 9/168 (5.4%), P = 0.99, OR = 1.00, 95%CI: 0.38-2.61] (Figure 2E).

DISCUSSION

Endoscopic biliary stenting is a useful technique for the relief of malignant lower bile duct obstruction, particularly in patients who are not eligible for surgery[13]. However, controversy has existed for a long time regarding the use of EST before stent placement. Those who prefer to perform EST based their choice on the fact that it was easier to place stents[14,15] and EST would decrease the incidence of PEP[4,5]. Others have indicated that the risks of EST might outweigh any potential benefits for the patient because of EST-related complications[16].

In the present meta-analysis, most baseline characteristics in the two groups were similar in all the studies included. Apart from the incidence of PEP (OR = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.12-0.93, P = 0.04) and the incidence of post-ERCP bleeding (OR = 9.70, 95%CI: 1.21-77.75, P = 0.03), other outcomes were not significantly different between the EST and non-EST groups.

On the one hand, our results seem to go against the idea that EST performed before stent placement will make the procedure easier. Usually, in patients with a malignant biliary obstruction, the biliary stricture is narrow and rigid, especially in those with pancreatic cancer. However, in the studies of Giorgio et al[10] and Zhou et al[12], the number of pancreatic cancer cases was similar between the two groups. Artifon et al[11] enrolled patients with pancreatic cancer, and their results indicated that stent insertion will presumably be difficult in patients with a malignant biliary obstruction; however, insertion should be possible even without EST. On the other hand, our results seem to support the idea that EST may decrease the rate of PEP. However, we realize that this result may result from biases. Firstly, unlike large plastic stents and covered self-expandable metal stents (SEMS), which are considered to cause occlusion of the pancreatic duct orifice by physical compression by the stent covered section[4], partially covered or uncovered SEMS will not close the pancreatic duct orifice[17]. Thus, the type of stent deployed will influence the possible development of PEP. Secondly, the various illnesses being treated may also have contributed to the biases in these results. For malignant tumors involving the head of the pancreas or the ampulla, partial or complete obstruction of the pancreatic duct outflow, diversion of pancreatic juice through the accessory pancreatic duct and diminished pancreatic function because atrophy of the distal pancreatic parenchyma may all lead to a low rate of PEP after stent placement, even if the stenting was to obstruct the opening of the main pancreatic duct. In contrast, in the presence of cholangiocarcinoma or lymph node metastasis, the potential for PEP may be higher as a result of compression of the orifice of the pancreatic duct. Some retrospective studies[18-20] suggested that in the presence of pancreatic duct obstruction associated with a malignant tumor, the risk of developing PEP is low, regardless of whether EST is performed, or whether plastic or metal stents are used. Biases may also occur because of different EST procedures and the experience of the endoscopists: when stents are deployed by skilled endoscopists, the overall rate of PEP may be low[19]. However, in this meta-analysis, we were unable to perform separate subgroup analyses of the outcome in patients with plastic vs metal stents, covered SEMS vs uncovered SEMS and pancreatic cancer vs cholangiocarcinoma or lymph node metastasis because of insufficient data.

Stent migration and occlusion are late complications of biliary stent placement. Biliary stenting may involve proximal or distal migration, which occurs in 5%-10% of patients[21-23]. There are few data on whether undergoing EST before placement of a biliary stent affects the risk of migration. Results based on clinical trials are contradictory. Some studies showed that EST did not significantly affect the frequency of stent migration[10,24]. One of the trials included in this meta-analysis showed that EST led to a higher rate of stent migration; however, this finding was not statistically significant (16.2% vs 2.7%, P = 0.075). In contrast, another trial indicated a higher frequency of stent migration in the non-sphincterotomy group vs the sphincterotomy group (8.5% vs 0%, P = 0.03)[25]. In our meta-analysis, only two trials reported the rate of stent migration and there was no significant difference between the two groups (OR = 2.31, 95%CI: 0.70-7.63, P = 0.17). The higher rate of migration in patients with EST could be explained by EST before stent deployment preventing the stent from embedding in the common bile duct[11]. However, multiple factors, such as stent diameter, length[22], bile duct diameter, stent design and even the definition of stent migration, may influence the final results[11]. Possible reasons for stent occlusion may include the formation of biliary sludge, tumor ingrowth or overgrowth, and epithelial hyperplasia inside the stent[26,27]. A breached sphincter in patients with EST may lead to bacterial invasion from the duodenum[28], and an increased risk of acute cholangitis at the early stage of stent placement[12]. With the expansion of stent and tumor growth, this phenomenon may decrease gradually. This may partially explain the result obtained in our meta-analysis where EST did not influence the incidence of stent occlusion.

The most important outcomes of this meta-analysis were the incidence of EST-related bleeding and perforation. The rates of bleeding and perforation have been estimated to be less than 1% and 2%. However, in patients with obstructing lesions of the common bile duct, such complication rates may be higher than expected. For those undergoing therapeutic interventions such as precut, the rate of these complications may be even higher[11]. One study[11] included in our meta-analysis reported a higher rate of bleeding and duodenal perforation (13.5% and 10.8%, respectively) in the patients undergoing needle-knife sphincterotomy before stent placement. Moreover, coagulopathy has been found to be an independent risk factor for hemorrhage after EST[29] and its incidence increases in cholestasis[30]. As with the previous studies, bleeding and perforation, which can sometimes be severe and life threatening, were only observed in those undergoing EST. In contrast, the reported PEP rate was only around 1.2%-6.3%[25,31] in patients with stent placement, regardless of whether EST was performed or the type of stents used. Most episodes were mild, and were not associated with any long-term pancreatic injury. It seems reasonable that EST should be avoided unless other indications, such as the insertion of a medical device into the bile duct for biopsy or brushing cytology, are required.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis showed that EST before stent placement may be useful in reducing the incidence of PEP. However, the possible biases and EST-related complications, such as bleeding and perforation, may offset this reduction in PEP. Further large multicenter RCTs are required.

COMMENTS

Background

Endoscopic biliary stenting is a useful technique for the relief of malignant lower bile duct obstruction, particularly in patients who are not eligible for surgery. However, there is still controversy over the use of endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) before the placement of a biliary stent.

Research frontiers

A biliary stent is often the only feasible therapeutic option for patients with malignant biliary obstruction. Some studies have reported that EST prior to stent insertion may lower the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP) and make stent placement easier. However, it is unclear whether patients with malignant biliary obstruction who undergo stent placement benefit from EST.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The present meta-analysis was performed to investigate the clinical outcomes in patients who did and did not undergo EST before stent placement based on available clinical trials.

Applications

The present meta-analysis showed that EST before stent placement may be useful in reducing the incidence of PEP. However, the possible biases and EST-related complications may offset this effect. Further large multicenter randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are required.

Terminology

EST, a method to provide access to the biliary system for therapy, is used by some biliary endoscopists as a common practice before stent placement.

Peer review

In this article, the authors investigated the clinical outcomes in patients who did or did not undergo EST before stent placement by a meta-analysis of available RCTs. The results showed that the EST before stent placement may be useful to reduce the incidence of PEP. However, the authors were unable to perform a separate subgroup analysis because of insufficient data; therefore, further large multicenter RCTs are required.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Abdel-Salam OME S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Stewart GJ E- Editor: Du P

References

- 1.Stern N, Sturgess R. Endoscopic therapy in the management of malignant biliary obstruction. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.07.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knyrim K, Wagner HJ, Pausch J, Vakil N. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of metal stents for malignant obstruction of the common bile duct. Endoscopy. 1993;25:207–212. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss AC, Morris E, Mac Mathuna P. Palliative biliary stents for obstructing pancreatic carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD004200. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004200.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarnasky PR, Cunningham JT, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ, Uflacker R, Vujic I, Cotton PB. Transpapillary stenting of proximal biliary strictures: does biliary sphincterotomy reduce the risk of postprocedure pancreatitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:46–51. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70301-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmons DT, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Baron TH. Risk of pancreatitis following endoscopically placed large-bore plastic biliary stents with and without biliary sphincterotomy for management of postoperative bile leaks. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1459–1463. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ang TL, Kwek AB, Lim KB, Teo EK, Fock KM. An analysis of the efficacy and safety of a strategy of early precut for biliary access during difficult endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in a general hospital. J Dig Dis. 2010;11:306–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilcox CM, Canakis J, Mönkemüller KE, Bondora AW, Geels W. Patterns of bleeding after endoscopic sphincterotomy, the subsequent risk of bleeding, and the role of epinephrine injection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:244–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Tugwell P, Moher M, Jones A, Pham B, Klassen TP. Assessing the quality of reports of randomised trials: implications for the conduct of meta-analyses. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3:i–iv, 1-98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giorgio PD, Luca LD. Comparison of treatment outcomes between biliary plastic stent placements with and without endoscopic sphincterotomy for inoperable malignant common bile duct obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1212–1214. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artifon EL, Sakai P, Ishioka S, Marques SB, Lino AS, Cunha JE, Jukemura J, Cecconello I, Carrilho FJ, Opitz E, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy before deployment of covered metal stent is associated with greater complication rate: a prospective randomized control trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:815–819. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31803dcd8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou H, Li L, Zhu F, Luo SZ, Cai XB, Wan XJ. Endoscopic sphincterotomy associated cholangitis in patients receiving proximal biliary self-expanding metal stents. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012;11:643–649. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(12)60238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith AC, Dowsett JF, Russell RC, Hatfield AR, Cotton PB. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bileduct obstruction. Lancet. 1994;344:1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leese T, Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL. Successes, failures, early complications and their management following endoscopic sphincterotomy: results in 394 consecutive patients from a single centre. Br J Surg. 1985;72:215–219. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaira D, D’Anna L, Ainley C, Dowsett J, Williams S, Baillie J, Cairns S, Croker J, Salmon P, Cotton P. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in 1000 consecutive patients. Lancet. 1989;2:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909–918. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Togawa O, Sasahira N, Kogure H, Sasaki T, Matsubara S, Yamamoto N, Hirano K, et al. Risk factors for pancreatitis following transpapillary self-expandable metal stent placement. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:771–776. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1950-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakahara K, Okuse C, Suetani K, Michikawa Y, Kobayashi S, Otsubo T, Itoh F. Covered metal stenting for malignant lower biliary stricture with pancreatic duct obstruction: is endoscopic sphincterotomy needed? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:375613. doi: 10.1155/2013/375613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilcox CM, Kim H, Ramesh J, Trevino J, Varadarajulu S. Biliary sphincterotomy is not required for bile duct stent placement. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:87–92. doi: 10.1111/den.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee N, Hilden K, Baron TH, Adler DG. Endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy is not required for transpapillary SEMS placement for biliary obstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:591–595. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1317-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deviere J, Baize M, de Toeuf J, Cremer M. Long-term follow-up of patients with hilar malignant stricture treated by endoscopic internal biliary drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(88)71271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johanson JF, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE. Incidence and risk factors for biliary and pancreatic stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:341–346. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davids PH, Groen AK, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Randomised trial of self-expanding metal stents versus polyethylene stents for distal malignant biliary obstruction. Lancet. 1992;340:1488–1492. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92752-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Güitrón A, Adalid R, Barinagarrementería R, Gutiérrez-Bermúdez JA, Martínez-Burciaga J. Incidence and relation of endoscopic sphincterotomy to the proximal migration of biliary prostheses. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2000;65:159–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margulies C, Siqueira ES, Silverman WB, Lin XS, Martin JA, Rabinovitz M, Slivka A. The effect of endoscopic sphincterotomy on acute and chronic complications of biliary endoprostheses. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:716–719. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Brien S, Hatfield AR, Craig PI, Williams SP. A three year follow up of self expanding metal stents in the endoscopic palliation of longterm survivors with malignant biliary obstruction. Gut. 1995;36:618–621. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.4.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmassmann A, von Gunten E, Knuchel J, Scheurer U, Fehr HF, Halter F. Wallstents versus plastic stents in malignant biliary obstruction: effects of stent patency of the first and second stent on patient compliance and survival. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:654–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung JY, Leung JW, Shaffer EA, Lam K, Olson ME, Costerton JW. Ascending infection of the biliary tract after surgical sphincterotomy and biliary stenting. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1992;7:240–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1992.tb00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabenstein T, Schneider HT, Bulling D, Nicklas M, Katalinic A, Hahn EG, Martus P, Ell C. Analysis of the risk factors associated with endoscopic sphincterotomy techniques: preliminary results of a prospective study, with emphasis on the reduced risk of acute pancreatitis with low-dose anticoagulation treatment. Endoscopy. 2000;32:10–19. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minemura M, Tajiri K, Shimizu Y. Systemic abnormalities in liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2960–2974. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahaleh M, Tokar J, Conaway MR, Brock A, Le T, Adams RB, Yeaton P. Efficacy and complications of covered Wallstents in malignant distal biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:528–533. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02593-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]