Abstract

Long-term care (LTC) eligibility criteria are applied to a sample of 8,437 people with dementia enrolled in the Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration. The authors find that mental-status-test cutoff points substantially affect the pool of potential beneficiaries. Functional criteria alone leave out people with relatively severe dementia and with behavioral problems. It is therefore important to consider both behavioral and mental-status-test criteria in establishing eligibility for community-based services for people with dementia.

Introduction

The most common dementing disorders that affect elderly persons are Alzheimer's disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD), with AD accounting for 60-80 percent of dementia in the elderly (Knopman, 1998). AD is a degenerative disease of the brain characterized by gradual onset and progressive intellectual, cognitive, and functional decline (Bartels and Colenda, 1998; Small et al., 1997). Comorbid conditions associated with AD, such as incontinence, psychosis, depression, and behavioral disturbances, are common and complicate the management of the disease (Small et al., 1997). There is no cure for AD, although pharmacologic treatments may retard the progression of symptoms (Rogers, Friedhoff, and Donepezil Study Group, 1996). Most treatment modalities attempt to assist people with the disease using psychosocial interventions.

The prevalence of AD increases with age. Current estimates suggest that more than 2 million people over age 65 have AD and that this number will increase to 3.2 million by the year 2015 (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1998). Within the U.S. elderly population, the fastest growing segment is the cohort age 85 or over, almost one-half (48 percent) of whom have AD (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1998; Evans, 1990). More than 50 percent of nursing home residents are estimated to have some form of dementia (Rovner et al., 1986), and the supply of nursing home beds is expected to fall far short of the demand in the near future (Manton and Liu, 1984). Because of the progressive course of many dementing disorders such as AD or VaD that result in increasing incapacity (Schore and Good, 1987; Zarit, Orr, and Zarit, 1985), 24-hour care or supervision may be required for years (Aronson and Lipkowitz, 1981; Blass, 1985; Cohen, Kennedy, and Eisdorfer, 1984). It is important to consider LTC eligibility criteria for persons with cognitive impairments because it is likely that the need for formal community-based services for people with AD and related diseases will increase over time.

Care costs associated with AD may include formal services such as physician services, inpatient care (hospital and nursing home), medications, adult day care, personal care, homemaker services, and transportation services, but currently the vast majority of LTC is provided informally by relatives and friends (Hu, Huang, and Cartwright, 1986; Hay and Ernst, 1987; Huang, Cartwright, and Hu, 1988; Welch, Walsh, and Larson, 1992; Rice et al., 1993; Gray and Fenn, 1993; Weinberger et al., 1993a; Ernst and Hay, 1994; Østbye and Crosse, 1994; Stommel, Collins, and Given, 1994; Max, Webber, and Fox, 1995; Souetre et al., 1995; Max, 1996; Cavallo and Fattore, 1997; Wimo et al., 1997). Formal services are financed through a variety of sources, including Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, philanthropy, and out-of-pocket payments (Rice et al., 1993). It has been estimated that the annual formal and informal cost of caring for people with AD in the United States is $100 billion, with an average per person lifetime cost of $174,000 (Alzheimer's Association, 1996).

LTC is assistance provided to people with chronic conditions over extended periods of time to assist them in everyday activities such as bathing, dressing, eating, and taking medications. The United States does not have a uniform national program with the primary purpose of paying for LTC. Instead, publicly funded LTC services are paid for by many Federal and State government programs. Virtually all the programs have eligibility criteria based on age and/or the presence of particular diseases and conditions. These criteria create six major categories of people eligible to receive services: (1) elderly people; (2) people with chronic physical diseases and conditions; (3) people with mental illness; (4) people with mental retardation and other developmental disabilities; (5) people with human immunodeficiency virus or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; and (6) children with chronic illnesses and special health care needs.

Out-of-pocket spending and Medicaid are the primary financing mechanisms for formal LTC in the United States. Although nursing home expenditures account for the majority of Medicaid spending (Gottlieb, 1996), States are expanding the portion that covers home care services (from 10.8 percent in 1987 to 24 percent in 1997) (Burwell, 1998). Projections indicate that Medicaid expenditures will more than double between 1993 and 2018 as the population ages and costs of care rise in excess of the general inflation rate (Wiener and Stevenson, 1997). Cost-of-care studies indicate that as much as 60 percent of the services provided to the AD population living in the community or in LTC facilities are paid out of pocket by patients and their families (Rice et al, 1993; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1994; Wiener and Stevenson, 1997). However, Medicaid programs are the primary public funding source for these services (Bartels and Colenda, 1998).

For older adults, the primary Federal programs other than Medicaid that pay for LTC services are Medicare, the Older Americans Act, and Department of Veterans Affairs programs. Although most Medicare payment covers medical care, benefits such as home health care services and durable medical equipment are increasingly considered LTC for some beneficiaries. States also use Federal social services block grant funds to pay for LTC services that reduce dependency, maintain self-sufficiency prevent abuse and neglect for children and adults, and reduce inappropriate institutionalization. States and localities determine the population subgroups that are eligible to receive such services. States may also use State general revenue funds to pay for LTC services for elderly people.

As awareness and concern about the care of people with AD and related dementias has grown over the past 15 years, advocates have increasingly sought to include these people in publicly funded programs that pay for LTC services. A major concern of advocates and policymakers is the identification of appropriate criteria to determine home and community-based LTC eligibility for older adults with cognitive impairments resulting from AD and related disorders. Various eligibility criteria have been proposed, and different programs are using different criteria (O'Keeffe, 1996; Lewin-VHI, 1995). Advocates and experts in AD and related dementias disagree about what criteria best identify people with dementia who need LTC services or other benefits such as tax deductions for LTC expenses.

Until recently eligibility criteria for most publicly funded programs that pay for LTC services were based on medical criteria, including the presence of particular diseases and conditions and needs for particular medical and skilled nursing treatments. Some people with AD and related dementias received services, but only if it could be shown that they had the specified diseases and conditions or treatment needs. Other people with dementia who clearly needed LTC services were not eligible.

As awareness of this problem has increased (Fox, 1989), this approach has come into question. Many publicly funded programs that pay for LTC services now use eligibility criteria based on functional limitations instead of, or in addition to, medical criteria. A major argument for using functional rather than medical criteria is that the former allow better targeting of people in need of long-term assistance. This approach assumes that the degree of functional limitation or disability is the important consideration, not the specific disease or condition that may be causing or contributing to the disability.

Functional-eligibility criteria are often based on need for assistance because of limitations in ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). Even these criteria can be problematic for people with dementing disorders. In the late 1980s, advocates and experts on AD and related dementias pointed out that ADL-based criteria defined in terms of physical assistance (as they usually were at the time) do not necessarily reflect the problems that cause a need for LTC in many people with dementia. Disability levels may even have to be high enough to qualify the client for nursing home placement. Adaptations to the definitions were proposed based on the idea that people with dementia may be physically capable of performing ADLs but require supervision, verbal reminding, or physical cueing to perform the functions. Wording incorporating these new definitions has been included in many congressional and other recommended proposals for new LTC programs since then.

In 1990, for example, the U.S. Bipartisan Commission on Comprehensive Health Care (1991), also known as the Pepper Commission, recommended the creation of a new LTC program that would provide nursing home and home and community-based services for people who “need hands-on or supervisory assistance with three out of five ADLs.” The Commission also recommended two other eligibility criteria that would include people with dementia: (1) “need for constant supervision because of cognitive impairment that impedes a person's ability to function;” and (2) “need for constant supervision because of behaviors that are dangerous, disruptive, or difficult to manage.”

From 1993 to 1996, numerous proposals were introduced in Congress to create new LTC programs (e.g., American Health Security Act of 1993, Long-Term Care Reform and Deficit Reduction Act of 1995, Secure Choice Act of 1993, Health Security Act of 1993, Affordable Health Care for All Americans Act of 1995, Welfare and Medicaid Responsibility Exchange Act of 1995, Quality Care for Life Act of 1995, Comprehensive Long-Term Care Reform Act of 1995). All of these proposals used ADL-based eligibility criteria and wording intended to include people with dementia (e.g., the person needs “hands-on or standby help, supervision, or cueing to perform two or more ADLs”). Some also used criteria based on mental-status-test scores (e.g., the person has “a severe cognitive or mental impairment as measured by a specified score on a mental-status test and needs hands-on or standby help, supervision, or cueing to perform one or more ADLs or specified IADLs [instrumental ADLs] or needs supervision because of serious behavioral symptoms”). A few of the proposals used additional eligibility criteria based on behavioral problems alone and combined with need for supervision (e.g., the person “needs supervision because of behavioral symptoms that are caused by a cognitive or mental impairment and create health or safety hazards for the person or others”). None of these proposals have been enacted to date.

In August 1996, Congress passed and President Clinton signed the Health Coverage Availability and Affordability Act of 1996, also known as the Kennedy-Kassebaum bill. This law allows Federal income tax deductions for expenditures for LTC services. The deductions are available for people of any age who: (1) are unable to perform, without substantial assistance from another person, two or more ADLs for a period of at least 90 days due to loss of functional capacity; or (2) have a level of disability similar to those just described in (1); or (3) require substantial supervision to protect the person from threats to health and safety due to severe cognitive impairment. The law also allows Federal income tax deductions for certain private LTC insurance policies (i.e., policies that pay for LTC services for people who meet one or more of the same criteria).

To implement this law, Internal Revenue Code section 213 and Treasury Regulations section 1.213 have been developed by the Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury with advice from the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The regulations allow itemized deductions for expenses for medical care for the taxpayer, his or her spouse, and dependents. The deduction is only allowed for expenses incurred during the year that are greater than 7.5 percent of adjusted gross income. This amount includes the sum of qualified LTC expenses plus other medical expenses, such as unreimbursed physician's bills, health insurance premiums including those for Medicare Part B, and unreimbursed prescription costs. These expenses are deductible only if the taxpayer itemizes deductions and the expenses have not been reimbursed by insurance (O'Neill, 1998).

In addition to publicly funded programs and Federal income tax deductions, many private LTC insurance policies now have benefit triggers intended to include people living with dementia. A 1995 survey found that the three types of benefit triggers that were being used were based on: (1) ADL limitations; (2) cognitive impairment, often defined in terms of mental-status-test scores; and (3) physician certification of medical necessity for LTC benefits (Alecxih and Lutzky, 1996). All of the policies have combinations of benefit triggers (e.g., the person needs assistance with two or more of five ADLs or has a score above a certain point on a mental-status test).

Although advocates, experts on LTC, and policymakers agree that people with AD and related dementias should be eligible for LTC services depending on their condition and need, there is disagreement and uncertainty about the criteria that should be used to identify them. It is generally assumed that ADL-based criteria will be used and that these criteria will be defined in terms intended to include people with dementia. The disagreement and uncertainty center on four questions:

How many and which specific ADL limitations should be used?

Should criteria based on limitations in IADLs also be used?

Should criteria based on mental-status-test scores also be used?

What, if any other criteria should be used?

Based on an analysis of Oregon Medicaid records, Kane, Saslow, and Brundage (1991) concluded that ADLs, with wording to include a need for supervision or cueing to perform them, would identify most people with dementia who need LTC services. Data from the HCFA Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration provide the opportunity for a more through assessment of the adequacy of ADLs and other criteria for determining eligibility for LTC and other benefits for people with dementia. The demonstration has extensive data on a sample of 8,437 people with AD and related disorders. We use these data to estimate the proportion of people with these conditions that would be defined in or out by eligibility criteria based on the following factors: (1) need for assistance due to ADL limitations; (2) need for assistance due to IADL limitations; (3) mental-status-test scores; (4) behavioral problems; and (5) need for supervision.

Using this information, we identify the effects of alternative eligibility criteria on modifying the sample pool of people with dementia who would be eligible for some benefit. Eligibility criteria that define subsets of people entitled to an LTC benefit only suggest the potential for utilization of the benefit. Nevertheless, the findings are valuable for Federal and State policymakers who must select eligibility criteria for public programs; for policy analysts who advise them; for those who select eligibility criteria for privately funded services and benefit triggers for private LTC insurance; and for advocates who are interested in obtaining benefits for people with dementia and families who are most in need of assistance.

Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration

The demonstration was mandated by Congress in response to awareness of caregiver problems in obtaining adequate and appropriate services to assist Medicare beneficiaries with dementia. It was administered at the Federal level by HCFA and implemented in 57 counties in Florida, Illinois, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and West Virginia. From December 1989 to November 1994, the demonstration offered case man agement and expanded in-home and community-based care for people with dementia and their informal (unpaid) caregivers by means of Medicare waivers. The demonstration was evaluated using an experimental design. Participants were randomized into a treatment group that received expanded Medicare benefits and a control group that did not.

To be enrolled in the demonstration, applicants had to have a physician-certified diagnosis of an irreversible dementia, be enrolled in or eligible for both Parts A and B of the Medicare program, have service needs due to cognitive and/or functional impairment, and reside in a site's catchment area. Demonstration participants were enrolled using a variety of techniques including host-agency waiting lists; host-agency staff networking; newspaper and radio advertisements; feature stories in local newspapers; informational flyers in telephone bills; presentations to community groups; and referrals from local medical, health, and social service providers (e.g., physicians, hospital discharge planners, social workers, nurses, and information and referral providers).

Two case management models were implemented. These differed by case manager-to-client ratio and per month service expenditure ceilings for each client. Model A sites operated with a target case manager-to-client ratio of 1:100 and had a monthly community service reimbursement limit or cap of $290-$489 per month per client. Model B sites operated with a target case manager-to-client ratio of 1:30 and had a higher reimbursement limit of $430-$699 per month per client. The per month reimbursement caps in each model varied by site over time because of regional cost variations and inflation adjustments. Acute care and other skilled care services usually covered under Medicare continued to be paid as part of the regular Medicare benefit.

Intake assessments were completed at the time of application to these programs. Applicants completing assessments were randomly assigned into the demonstration treatment group (where they were eligible for case management and service coverage) or into a control group (where they continued to receive their usual care). No restrictions were placed on a participant's ability to use community services; however, persons receiving case management services at the time of application (for example, through Medicaid home and community-based care programs) were generally not accepted into the demonstration. Treatment- or control-group members becoming eligible for such programs after enrollment remained in the demonstration. It is unlikely that the exclusion of people already enrolled in Medicaid community-based waiver programs affected the results of the study. In a study of Medicaid home and community-based waiver programs, O'Keeffe (1996) found that each of the 42 States surveyed used unique health and functional criteria for LTC eligibility determination. All of the States had a medical bias in their eligibility criteria in that functional impairment without a medical or nursing need was typically not sufficient to receive waivered services.

The availability of the demonstration's LTC benefit did not increase overall average formal service use but did shift reimbursement for the services from the private to the public sector. Demonstration enrollees, regardless of group assignment, were generally able to effectively obtain and pay for community-based LTC services, irrespective of case manager involvement or the level of service reimbursement available under the demonstration. Although treatment-group members had a higher probability than their control-group counterparts of accessing services with case manager support, the interventions did not result in a greater average amount of services used by the treatment group. Beneficiaries who had access to the demonstration benefit generally did not augment the service level by paying for additional services but merely substituted the Medicare reimbursement for out-of-pocket payments (Newcomer et al., to be published).

The data presented in this article are not generalizable to the U.S. population of older adults with dementia and only pertain to clients enrolled in the demonstration. However, it is one of the largest samples of people with dementia drawn from geographically diverse areas in the United States for which detailed sociodemographic, functional, cognitive, and caregiver data are available.

Measures

The data reported in this article were collected at entry into the demonstration, prior to randomization. Sociodemographic information on the demonstration sample includes age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education, income, Medicaid eligibility, type of health care coverage, living arrangement, and home ownership, which was reported by the primary caregiver of the person with dementia. The enrollee's physician provided data on the type of dementia in six diagnostic categories: (1) AD, (2) VaD, (3) dementia caused by degenerative disease, (4) dementia caused by central nervous system infection, (5) dementia caused by head trauma, and (6) other types of irreversible dementia.

Functional limitations were measured using the primary caregiver's report about the demented person's need for help to perform 10 ADLs, including the 5 specified by Katz et al. (1963) (i.e., bathing, dressing, transferring, using the toilet, and eating), 5 additional functions categorized as ADLs in the demonstration (continence, walking, wheelchair mobility, grooming, and transportation), and 8 IADLs adapted from Lawton and Brody (1969) (meal preparation, shopping, doing routine housework, managing money, doing laundry, managing medications, using the telephone, and doing heavy home chores). Table 1 displays the list of functional measures and associated coding guidelines that were used in the demonstration. For each ADL or IADL, caregivers were asked: Even if someone usually helps, could the client currently do the task without assistance? If not, then the caregiver was asked whether the client required some or maximum assistance. For each ADL or IADL, the probes listed in Table 1 were used by interviewers to help the respondent differentiate between “some” and “maximum” assistance. If some or maximum assistance was required, then the caregivers were asked whether the need for assistance was primarily attributable to physical, cognitive, or a combination of physical and cognitive impairments.

Table 1. Functional Status Coding Guidelines1.

| Instrumental Activity of Daily Living Coding Guidelines | |

| Meal Preparation | |

| • Can client prepare and cook a full meal? | 1 |

| • Can manage light snack meals by him/herself (not a full meal - i.e., breakfast, lunch)? | 2 |

| • Can client prepare any part of the meal him/herself? | 2 |

| • Does client need help with all/most of meal preparation tasks? | 3 |

| Shopping | |

| • How does client get groceries? | |

| - Can client shop for groceries him/herself? | 1 |

| - Does someone go along with client? | 2 |

| - Can client order by telephone and then put groceries away when delivered? | 2 |

| - Does client make his/her own shopping list then have someone purchase, deliver and put away the groceries? | 3 |

| - Does client need help with all shopping activities? | 3 |

| Routine Housework | |

| • Can client do all routine housework such as vacuuming, mopping floors, cleaning kitchen, and bathroom? | 1 |

| • Can client do light housework, such as dusting, tidying up, washing dishes? | 2 |

| • Is client unable to do housework at all? | 3 |

| Managing Money | |

| • Does client need help managing his/her own money? | 1 |

| • Does client need help writing his/her own checks? | 2 |

| • Does client need help balancing his/her own account? | 2 |

| • Does client need help paying his/her own bills? Can client keep track of them (does all of the above)? | 2 |

| • Can client manage day-to-day purchases? | 2 |

| • Is client unable to handle money at all? | 3 |

| Doing Laundry | |

| • Can client launder his/her own clothes? | 1 |

| • Can client do small items by him/herself? | 2 |

| • Does someone else do client's laundry? | 3 |

| Taking Medications | |

| If client does not currently take medications, try to estimate whether or not help would be needed and code accordingly. | |

| • Can client take his/her medications by him/herself? | |

| • Does client need reminders? | 1 |

| • Does anyone set them up for client? | 2 |

| • Does client need any one to give him/her his/her medications? | 2 |

| Using the Telephone | |

| • Can client use the telephone by him/herself? | 1 |

| • Does client need help with dialing, looking up numbers? | 2 |

| • Is client completely unable to use the telephone? | 3 |

| • Does client have vision or hearing problems that prevent him/her from using the phone? | 3 |

| Heavy Chores | |

| • Can client do the heavy chores around the house such as window washing, gardening, mowing the lawn? | 1 |

| • Who does general repairs? | |

| - Can client do any of this him/herself? | 2 |

| - Is client completely unable to do any heavy chores? | 3 |

| Activity of Daily Living Coding Guidelines | |

| Transportation Out of Walking Distance | |

| • When client has to travel to places out of walking distance, how does s/he usually get there? (For example, if client had to go to the doctor today, how would s/he get there?) | |

| •Does client need help in: | |

| - Getting to and from the car/bus/taxi (including stairs)? | 2 |

| - Getting in or out of the car/bus/taxi? | 2 |

| - Does someone always go along with client? | 2 |

| - If you were not available, could client go alone by bus or taxi? | 1 |

| - Does client need special arrangements such as ambulance; specially equipped vehicle; maximum help from one or more people; travel only for medical appointments? | 3 |

| Walking | |

| • Can client walk indoors without anyone helping him/her? | 1 |

| • Does client need: | |

| - Support just now and again? | 2 |

| - Just standby supervision? | 2 |

| - Continuous physical support of another person or does not walk? | 3 |

| Wheelchair Mobility | |

| • Can client propel the wheelchair indoors by him/herself (get to the bathroom, kitchen etc., independently) | 1 |

| • Does client need help with: | |

| - Locking/unlocking brakes? | 2 |

| - Getting through doorways? | 2 |

| - Getting up and down ramps? | 2 |

| - Is client pushed on occasion only for longer distances or outdoors? | 2 |

| - Does someone push client all or most of the time? | 3 |

| Activity of Daily Living Coding Guidelines | |

| Transfers (Bed/Chair) | |

| • Can client get in/out of bed/chair by him/herself? | 1 |

| • Does client need: | |

| - Support just now and again? | 2 |

| - Standby supervision? | 2 |

| - Does client have to be lifted by another person? | 3 |

| Grooming | |

| • Can client comb and shampoo his/her hair by him/herself? | 1 |

| • Can client shave himself? | 1 |

| • What about taking care of fingernails and toenails? | 1 |

| • Does client need help with: | |

| - Any of these activities? | 2 |

| - Some part of the activity? | 2 |

| - Is client unable to do any of these? | 3 |

| Bathing | |

| • Can client take his/her own bath? | 1 |

| • Does client need any help with: | |

| - Getting in/out of tub/shower? | 2 |

| - Turning on or bringing the water? | 2 |

| - Washing any part of the body? | 2 |

| - Towel drying? | 2 |

| - Sandby supervision, someone just to be there? | 2 |

| • Does someone have to bathe client? | 3 |

| Dressing | |

| • Can client get dressed by him/herself? | 1 |

| • Does client need any help with: | |

| - Getting clothes from the drawer or closet? | 2 |

| - Putting on pants ot shirt? | 2 |

| - Fasteners? | 2 |

| - Shoes (except for tying shoes)? | 2 |

| • Is client mainly dressed by a helper? | 3 |

| • Does client often stay partly or completely undressed? | 3 |

| Eating | |

| • Can client feed him/herself? | 1 |

| • Does client need help with: | |

| - Cutting meat, buttering bread? | 2 |

| - Opening cartons, pouring liquid? | 2 |

| - Holding glass or cup? | 2 |

| • Does someone feed client? | 3 |

| Using the Toilet | |

| • Can client go to the bathroom and use the toilet by him/herself? | 1 |

| • Does client need help with: | |

| - Getting there? | 2 |

| - Cleaning him/herself? | 2 |

| - Getting on or off the toilet seat? | 2 |

| - Arranging his/her clothes? | 2 |

| If client uses bedpan or commode: | |

| • Does client need help with this at night or help in disposing of contents? | 2 |

| • Is client unable to use the bathroom at all? | 3 |

| • Does someone help client with a bowel or bladder program? | 3 |

| If client has catheter/ostrmy: | |

| • Does client take full care of it? | 1 |

| • Does client need help with cleaning, changing bag, or disposing of contents? | 2 |

| • Is client unable to do any of this? | 3 |

| Bowel/Bladder Accidents | |

| • Is client able to control urination and bowel elimination all the time? | 1 |

| • If client has bowel or bladder accidents: | |

| - Does client have occasional accidents (once a week or less)? | 2 |

| - Is client incontinent frequently or most of the time (more than once a week)? | 3 |

1-No help needed; 2-some help needed; 3-maximum help needed.

SOURCE: UCSF/IHA Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration and Research Project, 1989.

Cognitive status was directly measured by asking the person with dementia the 30-item Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE), developed by Folstein, Folstein, and McHugh (1975). Behavioral symptoms were measured by caregiver report using an adaptation of the index developed by Zarit, Orr, and Zarit (1985). Caregivers were asked whether the person with dementia typically exhibited each of the 19 behaviors that make up the index. Need for supervision was measured by asking caregivers whether, in a typical week, the person with dementia required minimal supervision, daytime supervision, or round-the-clock supervision. The level of primary and secondary caregiver involvement in assisting was measured by asking the primary caregiver the total average number of hours per week spent helping the person with dementia.

Results

Study Sample

A total of 8,437 persons with dementia are included in this analysis. They were enrolled between December 1, 1989, and November 30, 1991, and followed for up to 36 months in the community or for 1 year following admission to a nursing home. Table 2 describes the sociodemographic and diagnostic characteristics of the sample.

Table 2. Sociodemographic and Dementia Diagnosis Characteristics of the Sample.

| Client Characteristics | Percent |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |

| Female | 60.1 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 87.3 |

| Black | 8.6 |

| Hispanic | 3.9 |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 55.0 |

| Widowed | 38.3 |

| Never Married | 2.3 |

| Elementary or High School Education | 73.0 |

| Income Less than $15,000 | 56.1 |

| Medicaid-Eligible | 6.8 |

| HMO Health Care Coverage | 20.8 |

| Living Arrangement | |

| Lives Alone | 14.9 |

| Lives with Spouse Only | 44.1 |

| Lives with Spouse and Other Relatives | 5.7 |

| Lives with Relatives Other than Spouse | 29.0 |

| Homeowner | 47.8 |

| Lives with a Relative at No Charge | 34.3 |

| Dementia Diagnosis | |

| Alzheimer's Disease | 69.3 |

| Vascular Dementia | 22.7 |

| Other Irreversible Dementia | 8.0 |

NOTES: N = 8,437; mean age = 79.0, standard deviation = 8.0. HMO is health maintenance organization.

SOURCE: IHA/UCSF Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration Baseline Data, 1995.

ADLs

Table 3 shows the proportion of the sample who were reported by their primary caregiver as needing assistance with each of the 10 ADLs included in the study. For the demonstration, need for ADL assistance was defined as due to either a physical or mental impairment. The term “mental impairment” was used because it was believed to be easily understood by the general population of older adults and therefore preferable to a more technical term such as “cognitive impairment.”

Table 3. Proportion of the Sample Needing Assistance with Activities of Daily Living.

| Activities of Daily Living | Number | Percent Needing Assistance |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation1 | 7,821 | 92.7 |

| Grooming | 6,246 | 74.0 |

| Bathing | 6,235 | 73.9 |

| Dressing | 5,884 | 69.7 |

| Continence | 4,307 | 51.0 |

| Eating | 4,045 | 47.9 |

| Using the Toilet | 3,755 | 44.5 |

| Walking | 3,153 | 37.3 |

| Transferring | 2,837 | 33.6 |

| Wheelchair Mobility | 1,557 | 18.4 |

Out of walking distance.

NOTE: N = 8,437.

SOURCE: IHA/UCSF Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration Baseline Data, 1995.

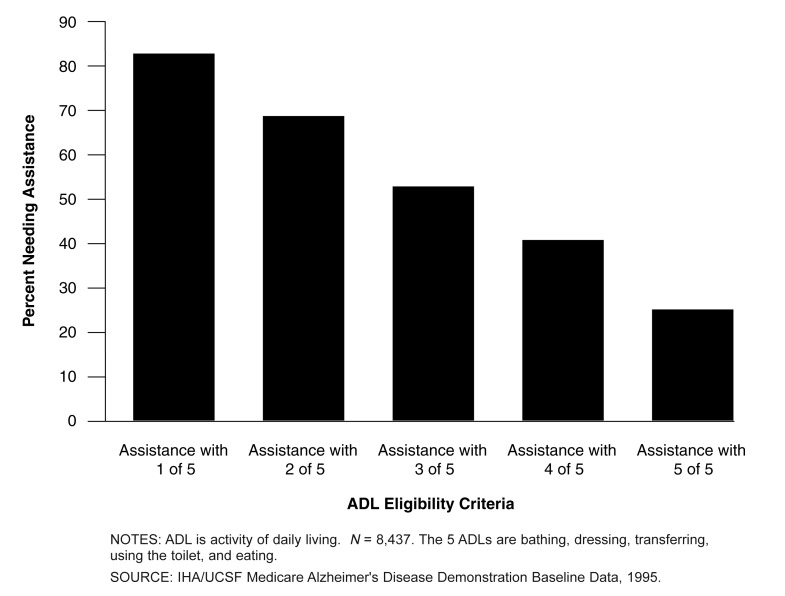

Need for assistance with at least two or at least three of five basic ADLs (bathing, dressing, transferring, using the toilet, and eating) is used to determine eligibility for LTC services in many existing and proposed programs. Figure 1 shows the proportion of the sample that would be eligible based on a need for help using these and other ADL criteria. Sixty-nine percent would be eligible using a two-of-five criterion, and 54 percent would be eligible based on a three-of-five criterion. One-quarter of the sample needed help with all five ADLs.

Figure 1. Proportion of the Sample Eligible for Long-Term Care Using Different ADL Criteria.

As previously mentioned earlier, the Health Care Coverage Availability and Affordability Act of 1996 allows eligibility for people who need help with at least two ADLs, but the law includes six ADLs, the five basic already listed and continence. Adding continence increases the proportion of the sample that is eligible from 69 to 72 percent. If the requirement were for at least three of six ADLs, adding continence would increase the proportion that would be eligible from 54 to 59 percent.

Some congressional proposals for new LTC programs use criteria based on need for help with at least two or at least three of six ADLs, including the five basic ones previously listed and walking. Adding walking to the five basic ADLs would increase the proportion of the sample that would be eligible from 54 to 56 percent. Adding grooming or transportation out of walking distance to the basic five ADLs would increase the proportion of the sample that would be eligible by slightly greater amounts (7 and 12 percent, respectively). If using the three-of-five criterion, adding walking, grooming, or transportation out of walking distance to the basic five ADLs would also increase the proportion that would be eligible (by 3, 12, and 14 percent, respectively).

IADLs

Many advocates for people with AD-related dementias believe that criteria based on need for help with some IADLs should be used in addition to ADL criteria to determine eligibility for LTC services. For example, an IADL eligibility criterion that is included in some private LTC insurance products is the person's ability to take medications (Lewin-VHI, 1995). Some State Medicaid programs use IADL criteria such as a person's ability to shop or manage money (Snow, 1995). If a criterion based on need for help with two or more IADLs were used, 99 percent of the sample would be eligible. If a criterion based on need for help with three or more were used, 98 percent would be eligible. Almost three-quarters (73.2 percent) of the sample is impaired in all eight IADLs.

Mental-Status Tests

The MMSE was used to measure cognitive status (Folstein, Folstein, and McHugh, 1975). We used the MMSE cutoff scores of 23 and above (mild) and 17 and below (severe) that were used by Kramer et al. (1985) in the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program Survey conducted in Baltimore, Maryland. We also used a lower cutoff of 12 and below that clinicians traditionally use as a guide for identifying very severe levels of cognitive impairment. Using these cutoffs, 86.5, 60.5, and 40.9 percent of the sample, respectively, would be included in eligibility pools.

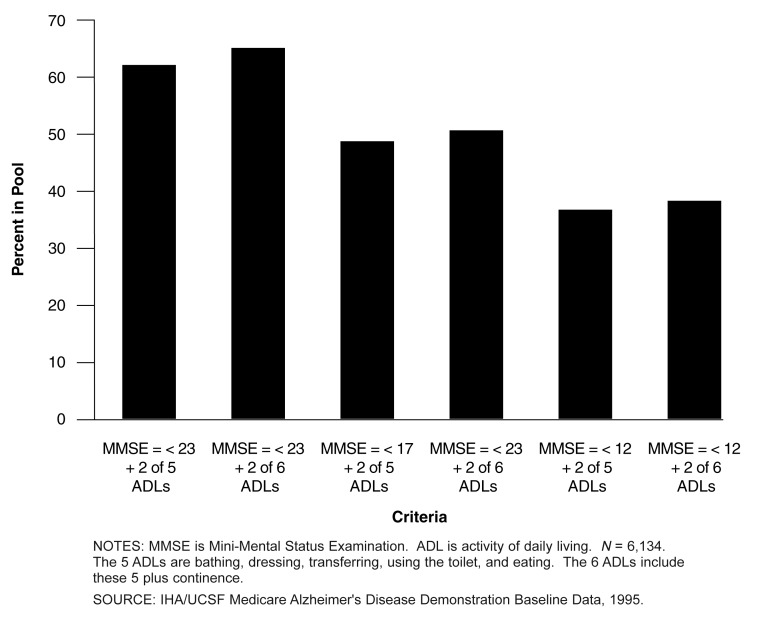

Functional and Mental-Status Criteria Combined

Figure 2 shows changes in the size of the eligible pools of sample members using various combinations of ADL and MMSE inclusion criteria. Using a cutoff of 23 and below, combined with a need for help with two of five or two of six ADLs (adding continence), 61.2 percent and 64.5 percent of the sample, respectively, would be eligible for benefits. Using a cutoff of 17 and below, and the same ADL criteria, 48.7 percent and 50.4 percent of the sample, respectively, would be eligible for benefits. Using a cutoff of 12 and below and the ADL criteria, 36.3 and 37.1 percent of the sample, respectively, would be included.

Figure 2. Proportion of the Sample Eligible Using Combined MMSE/ADL Criteria.

If the eligibility criteria specify that a person needs to have ADL impairments or a particular score on a mental-status test, a larger proportion of the sample is included than if the criteria are used in combination. For example, using the criteria of an MMSE score of 23 or less makes an additional 25 percent of the sample eligible over ADL criteria alone. Using 17 or greater or 12 or greater also increases the proportion of the sample that is eligible (12 and 5 percent, respectively). Even though a mental-status-test criterion increases the proportion of the sample that would be eligible compared with the ADL criterion alone, as already noted, there are significant proportions of the sample that would be eligible based on both criteria.

Behavioral Problems

Many advocates and experts on AD and related dementias believe that criteria based on potentially harmful behavioral problems should be used to determine eligibility for LTC services. The proportion of people that would be eligible based on behavioral problems depends on which problems are included. Table 4 shows the proportion of the sample that has each of the 19 behavioral problems measured in the demonstration.

Table 4. Proportion of the Sample Having Behavioral Problems.

| Behavioral Problem | Number | Percent with Problem |

|---|---|---|

| Forgets what day it is | 7,872 | 93.3 |

| Loses or misplaces things | 6,362 | 75.4 |

| Asks repetitive questions | 5,771 | 68.4 |

| Has trouble recognizing familiar people | 4,775 | 56.6 |

| Leaves tasks uncompleted | 4,623 | 54.8 |

| Is suspicious or accusative | 4,379 | 51.9 |

| Relives situations from the past | 4,176 | 49.5 |

| Hides things | 4,033 | 47.8 |

| Wakes you up at night | 3,873 | 45.9 |

| Has episodes of unreasonable anger | 3,889 | 46.1 |

| Is constantly restless | 3,864 | 45.8 |

| Sees or hears things that are not there | 3,628 | 43.0 |

| Does things that embarrass you | 3,350 | 39.7 |

| Is constantly talkative | 2,303 | 27.3 |

| Wanders or gets lost | 2,227 | 26.4 |

| Has episodes of combativeness | 2,168 | 25.7 |

| Engages in behavior potentially dangerous to self | 1,783 | 21.2 |

| Destroys property | 937 | 11.1 |

| Engages in behavior potentially dangerous to others | 911 | 10.8 |

NOTE: N = 8,437.

SOURCE: IHA/UCSF Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration Baseline Data, 1995.

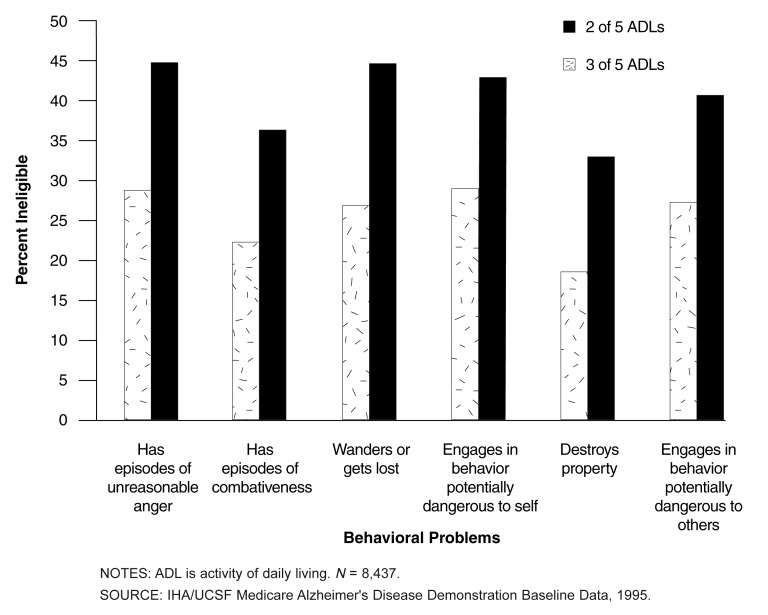

Proposals that use criteria based on behavioral problems focus on behaviors that create threats to the health or safety of people with dementia, their caregivers, or others. Behavioral problems from Table 4 that generally fit this definition are “has episodes of unreasonable anger,” “has episodes of combativeness,” “wanders or gets lost,” “destroys property,” “engages in behavior potentially dangerous to others,” and “engages in behaviors potentially dangerous to self.” ADL criteria would not include all the members of the sample who typically have these five behavioral problems. Figure 3 shows the proportion of the sample that have each of the five behavioral problems but would not be eligible based on ADL criteria. If behavioral criteria were combined with ADL criteria, relatively large proportions of people in both the two-of-five and three-of-five ADL impairment groups would be eligible for benefits.

Figure 3. Proportion of the Sample with Health and Safety-Related Behavioral Problems Ineligible for Long-Term Care Using ADL Criteria Alone.

Need for Supervision

Caregivers were asked whether, in a typical week, the person with dementia required minimal supervision, daytime supervision, or round-the-clock supervision. One-quarter of the sample needed minimal, 19 percent needed daytime, and 56 percent required round-the-clock supervision. Of the sample who needed round-the-clock supervision, 14 percent would not be eligible using the criterion of need for help with two of five ADLs, and 27 percent would not be eligible using the three-of-five criterion.

Total Caregiving Hours and Eligibility Criteria

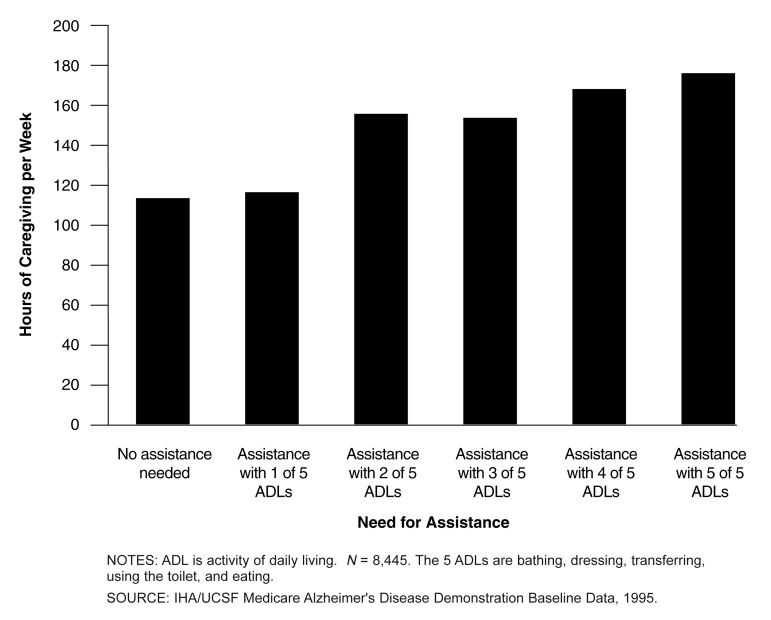

We examined the relationship between hours of informal caregiving and ADL-based eligibility criteria, MMSE scores, and need for supervision. As shown in Figure 4, there is essentially no difference in total caregiving hours using the two-of-five or three-of-five ADL criteria (154 versus 153 hours, respectively). However, as need for supervision increases, hours of informal help increase substantially. As shown in Table 5, sample members who need minimal supervision require an average of 79 fewer informal hours of help per week than those who need round-the-clock supervision.

Figure 4. Relationship Between Caregiver Hours and Need for ADL Assistance.

Table 5. Relationship Between Caregiver Hours and Level of Supervision Needed.

| Level of Supervision | Number | Hours of Caregiving per Week | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | ||

| Minimal | 2,096 | 97.1 | 270.9 |

| Daytime | 1,581 | 129.0 | 264.7 |

| Round-the-Clock | 4,739 | 176.3 | 297.7 |

NOTE: N = 8,416.

SOURCE: IHA/UCSF Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration Baseline Data, 1995.

As would be expected, the greater the cognitive impairment of sample members, the greater their need for supervision (data not shown). Those who need round-the-clock supervision on average score eight MMSE points lower than those who need minimal supervision. As MMSE scores decline, increased hours of informal help are also provided. For example, caregivers of sample members with an MMSE score of less than 13 spend an average of 120 hours per week helping; 94 hours with a score between 13 and 23; and 75 hours for those with scores above 23.

Conclusions

These data have several potential policy implications. The clearest is that using impairments in the basic five ADLs alone as the basis for determining eligibility for home and community-based LTC benefits for this sample, even if impairments are assessed for both physical and cognitive difficulties, will leave out people with relatively severe dementia (based on MMSE scores) as well as those with behavioral problems that may pose health or safety risks to themselves or others. In this sample of people with irreversible dementia, there is a direct relationship between declines in MMSE scores (roughly indicating more severe impairment) and increased hours of informal assistance. The behavioral problems of the sample were reported by caregivers as typical and so heighten the possibility that certain behaviors may pose real health and safety risks to the person with dementia and/or the caregiver. It is therefore important to include behavioral criteria related to safety issues (e.g., has unreasonable anger, has combativeness, wanders or gets lost, destroys property, engages in behavior potentially dangerous to others, and engages in behaviors potentially dangerous to self) and mental-status criteria.

Although IADL eligibility criteria may be useful for differentiating potential users of an LTC benefit, they do not appear useful when applied to people with dementia. IADL-based criteria for determining eligibility for home and community-based care do not differentiate among groups of persons with dementia whose needs may be greater than others. For practical purposes, IADL impairments are present in all persons in the sample and so have limited utility as eligibility criteria if the purpose is to discriminate among the impairment levels of people with dementia.

Using both mental-status criteria such as MMSE cutoffs and ADL criteria result in smaller eligibility pools. Within the pools created by using each MMSE cutoffs (≤ 23, ≤ 17, and ≤ 12), there is little variation in the proportion of eligible beneficiaries added when applying either ADL criteria. There is, however, substantial variation in the size of the eligible pools when the different MMSE cutoffs are used. For example, the highest MMSE cutoff (≤ 23) used alone incorporates 86 percent of the sample. If the two-of-five ADL criterion is used alone, the eligible pool is 69 percent of the sample. Used together, the eligible pool shrinks to 61 percent of the sample, because the MMSE cutoff a priori reduces the pre-ADL criteria pool by about 13 percent.

It is interesting to note that the relatively simple caregiver report of need for supervision (i.e., minimal, daytime, round-the-clock) identified somewhat similar categories of people with dementia when compared with ADL criteria. For example, 2,096 people were included in the group requiring minimal supervision (an average of 97.1 hours per week) versus 2,656 people requiring minimal assistance (an average of 114 hours per week) with up to one of five ADLs. The 1,581 people with dementia requiring daytime assistance (an average of 129 hours per week) were a smaller group with fewer care needs than the 2,386 people who required assistance (an average of 153 hours per week) using the two-of-five or three-of-five ADL criteria. Finally, 4,739 people requiring round-the-clock assistance (an average of 176 hours per week) is roughly equivalent to the average 172 hours per week caregivers spend helping the 3,403 people with dementia requiring assistance with four of five or five of five ADLs.

The identification of people eligible for a potential LTC benefit using mental-status, ADL, or behavioral criteria presumably requires some type of professional assessment that contributes to program administrative costs. Although using a mental-status score in conjunction with the relatively simple caregiver report of need for supervision would be a much simpler and less costly way of determining eligibility, it would tend to underestimate those who need assistance using the most common ADL criteria (i.e., two of five or three of five). Although it is possible that a need-for-supervision eligibility criterion may be applicable to other than demented population groups who may need LTC, other criteria would likely be needed. For example, the need for hands-on assistance because of physical impairments in a cognitively intact person would not necessarily be classified as a “need for supervision.”

Eligibility criteria reflect societal judgments about who should receive a benefit and can be used to expand or restrict access to them. We used average total caregiver hours spent helping people with dementia as an indicator of the potential effect of various eligibility criteria on caregivers. Time spent helping a person with dementia may vary considerably given individual caregiver anxieties, preferences, and motivation. But average caregiving time is a rough indicator of LTC resources expended to maintain the person with dementia in the community, which is the primary goal of a community-based LTC benefit. As with functionally impaired people in general, and especially those with irreversible dementing disorders, informal caregivers provide the vast majority of LTC. It has been estimated that approximately three-quarters of the total cost of caring for community-resident persons with AD is borne by the informal care system (Rice et al., 1993).

Although the characteristics of the person with dementia are the eligibility triggers, caregivers are also presumed to benefit from policies affecting people with dementia. When viewed from a caregiver-hours perspective, there is no difference in the average amount of time spent helping people with dementia who qualify using the two-of-five or three-of-five ADL criteria. But lowering the criterion to two-of-five ADL impairments expands the eligible pool by 15 percent. If a policy goal is to limit potential benefit costs, for example, then using the three-of-five criterion may be appropriate.

The analysis presented herein only suggests a potential for utilization of LTC and other benefits based on an expansion or contraction of the eligible pool of this sample of people with dementia using combinations of criteria. Studies of the service-utilization patterns of people with dementia suggest that this group mirrors the rest of the elderly population in that they use minimal amounts of formal services (Yordi et al., 1997; Weinberger et al., 1993b; Biegel et al., 1993; Malone Beach, Zarit, and Spore, 1992; Bass, Looman, and Ehrlich, 1992; Gonyea and Silverstein, 1991; Coyne 1991; Montgomery and Borgatta, 1989; Lawton, Brody, and Saperstein, 1989). The use of a benefit such as LTC services is not addressed by these analyses, and so it is not possible to assess what effect different eligibility criteria may have on the actual use of a benefit.

Footnotes

Patrick Fox and Xiulan Zhang are with the University of California, San Francisco. Katie Maslow is with the Alzheimer's Association. This research was supported by a grant from the United States Congress Office of Technology Assessment. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of California, San Francisco, the Alzheimer's Association, or the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA).

Reprint Requests: Patrick Fox, Ph.D., Professor of Sociology in Residence, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143-0646. E-mail: pf1965@itsa.ucsf.edu

References

- Alecxih LM, Lutzky S. How Do Alternative Eligibility Triggers Affect Access to Private Long Term Care Insurance? Washington, DC.: American Association of Retired Persons; 1996. Pub. No. 9605. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer's Association. National Public Policy Program to Conquer Alzheimer's Disease. Chicago, IL.: Alzheimer's Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson MK, Lipkowitz R. Senile Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type: The Family and Health Care Delivery System. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1981 Dec;29(12):568–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1981.tb01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Colenda CC. Mental Health Services for Alzheimer's Disease: Current Trends in Reimbursement and Public Policy and the Future Under Managed Care. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1998;6(2):S85–S100. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199821001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass DM, Looman W, Ehrlich P. Predicting the Volume of Health and Social Services: Integrating Cognitive Impairment and the Modified Andersen Framework. The Gerontologist. 1992 Feb;32(1):33–43. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigel D, Bass D, Schulz R, et al. Predictors of In-home and Out-of-home Service Use by Family Caregivers of Alzheimer's Disease Patients. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993 Nov;5(4):419–438. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blass JP. Alzheimer's Disease. DM Disease of the Month. 1985 Apr;31(4):1–69. doi: 10.1016/0011-5029(85)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell B. Medicaid Long Term Care Expenditures in FY 1997. Cambridge, MA.: The MEDSTAT Group; Apr 6, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo MC, Fattore G. The Economic and Social Burden of Alzheimer Disease on Families in the Lombardy Region of Italy. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 1997 Dec;11(4):184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Kennedy G, Eisdorfer C. Phases of Change in the Patient with Alzheimer's Disease: A Conceptual Dimension for Defining Health Care Management. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1984 Jan;32(1):11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1984.tb05143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne AC. Information and Referral Usage Among Caregivers of Dementia Patients. The Gerontologist. 1991 Jun;31(3):384–389. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst RL, Hay JW. The U. S. Economic and Social Costs of Alzheimer's Disease revisited. American Journal of Public Health. 1994 Aug;84(8):1261–1264. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. Estimated Prevalence of Alzheimer's Disease in the United States. Milbank Quarterly. 1990;68(2):267–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox P. From Senility to Alzheimer's Disease: The Rise of the Alzheimer's Disease Movement. The Milbank Quarterly. 1989;67(1):58–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonyea JG, Silverstein NM. The Role of Alzheimer's Disease Support Groups in Families' Utilization of Community Services. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1991;16(3/4):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb GL. Financial Issues. In: Sadavoy J, Lazarus LW, Jarvik LF, editors. Comprehensive Review of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2nd. Washington, DC.: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. pp. 1065–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Gray A, Fenn P. Alzheimer's Disease: The Burden of the Illness in England. Health Trends. 1993;25(1):31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JW, Ernst RL. The Economic Costs of Alzheimer's Disease. American Journal of Public Health. 1987 Sep;77(9):1169–1175. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.9.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T, Huang L, Cartwright W. Evaluation of the Costs of Caring for the Senile Demented Elderly: A Pilot Study. The Gerontologist. 1986 Apr;26(2):158–163. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Cartwright W, Hu T. The Economic Cost of Senile Dementia in the United States, 1985. Public Health Reports. 1988 Jan-Feb;103(1):3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane R, Saslow M, Brundage T. Using ADLs to Establish Eligibility for Long-Term Care Among the Elderly. The Gerontologist. 1991 Feb;31(1):60–66. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of Illness in the Aged: The Index of ADL, a Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Functioning. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963 Sep;185(12):94–101. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman D. The Initial Recognition and Diagnosis of Dementia. The American Journal of Medicine. 1998 Apr;104(4A):2S–12S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M, German P, Anthony J, et al. Patterns of Mental Disorder among the Elderly Residents of Eastern Baltimore. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1985 Apr;33(4):236–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb07110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of Older People: Self-Maintaining and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. The Gerontologist. 1969 Autumn;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM, Saperstein AR. A Controlled Study of Respite Service for Caregivers of Alzheimer's Patients. The Gerontologist. 1989 Feb;29(1):8–16. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin-VHI. Private Long Term Care Insurance Benefit Eligibility Triggers: The Implications of Alternative Definitions. Washington, DC.: The Lewin Group; Sep 5, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Malone Beach E, Zarit S, Spore D. Caregiver's Perceptions of Case Management and Community-based Services: Barriers to Service Use. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1992 Jun;11(2):146–159. doi: 10.1177/073346489201100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manton K, Liu K. The Future Growth of the Long Term Care Population. Unpublished paper presented at the Third National Leadership Conference on Long Term Care Issues; Washington, DC.. March 7-9, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Max W. The Cost of Alzheimer's Disease: Will Drug Treatment Ease the Burden? PharmacoEconomics. 1996 Jan;9(1):6–10. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199609010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max W, Webber PA, Fox PJ. Alzheimer's Disease. The Unpaid Burden of Caring. Journal of Aging and Health. 1995 May;7(2):179–199. doi: 10.1177/089826439500700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJ, Borgatta EF. The Effects of Alternative Support Strategies on Family Caregiving. The Gerontologist. 1989 Aug;29(4):457–464. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer R, Yordi C, Fox P, et al. Effects of the Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration on the Use of Community-Based Services. Health Services Research. to be published. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keeffe J. Determining the Need for Long term Care Services: An Analysis of Health and Functional Eligibility Criteria in Medicaid Home and Community Based Waiver Programs. Washington, DC.: American Association of Retired Persons, Public Policy Institute; Nov, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill J. Are the Costs of Caring for a Person with Alzheimer's Disease Deductible? Chicago, IL.: The Alzheimer's Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Østbye T, Crosse E. Net Economic Costs of Dementia in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1994 Nov;151(10):1457–1464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D, Fox P, Max W, et al. The Economic Burden of Caring for People with Alzheimer's Disease. Health Affairs. 1993 Summer;12(2):164–176. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT, Donepezil Study Group The Efficacy and Safety of Donepezil in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease: Results of a U S Mulicenter, Randomized, Double-blind Placebo Controlled Trial. Dementia. 1996 Nov-Dec;7(6):293–303. doi: 10.1159/000106895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovner B, Kafonek S, Filipp L, et al. Prevalence of Mental Illness in a Community Nursing Home. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986 Nov;143(11):1446–1449. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.11.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schore J, Good T. Literature Review for Design of the Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration. Princeton, NJ.: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Small G, Rabins P, Barry P, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders: Consensus Statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer's Association, and the American Geriatrics Society. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997 Oct 22/29;278(16):1363–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow KI. How States Determine Nursing Facility Eligibility for the Elderly: A National Survey. Washington, DC.: American Association of Retired Persons, Public Policy Institute; Nov, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Souetre EJ, Qing W, Vigoureux I, et al. Economic Analysis of Alzheimer's Disease in Outpatients: Impact of Symptom Severity. International Psychogeriatrics. 1995 Spring;7(1):115–122. doi: 10.1017/s1041610295001906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stommel M, Collins CE, Given BA. The Costs of Family Contributions to the Care of Persons with Dementia. The Gerontologist. 1994 Apr;34(2):199–205. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bipartisan Commission on Comprehensive Health Care. A Call for Action. Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Cost Estimates for the Long Term Care Provisions under the Health Security Act. Washington, DC.: Mar, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Alzheimer's Disease: Estimates of Prevalence in the United States. Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jan, 1998. Pub. No. HEHS-98-16. [Google Scholar]

- Welch HG, Walsh JS, Larson EB. The Cost of Institutional Care in Alzheimer's Disease: Nursing Home and Hospital use in a Prospective Cohort. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992 Mar;40(3):221–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger M, Gold DT, Divine GW, et al. Expenditures in Caring for Patients with Dementia who Live at Home. American Journal of Public Health. 1993a Mar;83(3):338–341. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.3.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger M, Gold D, Divine G, et al. Social Service Interventions for Caregivers of Patients with Dementia: Impact on Health Care Utilization and Expenditures. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1993b Feb;41(2):153–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener JM, Stevenson DG. Long-Term Care for the Elderly and State Health Policy. No A-17. Washington, DC.: The Urban Institute; 1997. (A). [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Karlsson G, Sandman PO, et al. Cost of Illness Due to Dementia in Sweden. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997 Aug;12(8):857–861. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199708)12:8<857::aid-gps653>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yordi C, DuNah R, Bostrom A, et al. Caregiver Supports: Outcomes from the Medicare Alzheimer's Disease Demonstration. Health Care Financing Review. 1997 Winter;19(2):97–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit S, Orr N, Zarit J. The Hidden Victims of Alzheimer's Disease: Families Under Stress. New York: New York University Press; 1985. Understanding the Stress of Caregivers: Planning an Intervention. [Google Scholar]