Abstract

The Oregon Health Plan (OHP), Oregon's section 1115 Medicaid waiver program, expanded eligibility to all residents living below poverty. We use survey data, as well as OHP administrative data, to profile the expansion population and to provide lessons for other States considering such programs. OHP's eligibility expansion has proved a successful vehicle for covering large numbers of uninsured adults, although most beneficiaries enroll for only a brief period of time. The expansion population, particularly childless adults, is relatively sick and has high service use rates. Beneficiaries are also likely to enroll when they are in need of care.

Introduction

The size of the uninsured U.S. population has been a persistent concern, even during recent years of strong economic growth and low unemployment. Expanding Medicaid eligibility has been adopted as one approach to reducing the ranks of the uninsured, particularly among children and pregnant women. A few States have adopted a broader Medicaid strategy, using it to cover low-income populations generally. Among these is Oregon's section 1115 Medicaid waiver program, OHP, which expands Medicaid eligibility to include all residents with incomes below 100 percent of the Federal poverty level (FPL). Other important innovations adopted as part of OHP include the use of a prioritized list of medical conditions and treatments to define the benefit package and mandatory enrollment in managed care for nearly all eligibles.

The OHP expansion population includes adults age 19 or over and is divided into two groups: adults with children and childless adults.1 Prior to Oregon's implementation in July 1998 of the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), which covers all children under age 19, up to 170 percent of the FPL, the adults with children category also included children born before October 1, 1983.2 Although the two categories of expansion beneficiaries are subject to the same eligibility standards and receive the same benefits, OHP distinguished the two groups because it was assumed that their utilization would differ substantially. Adults with children were thought to closely resemble traditional Aid to Families with Dependent Children (now Temporary Assistance for Needy Families [TANF]) eligibles, whereas, childless adults initially were expected to resemble a commercially insured population. However, after the program was implemented, it became evident that childless adults were far sicker and more costly than anticipated.

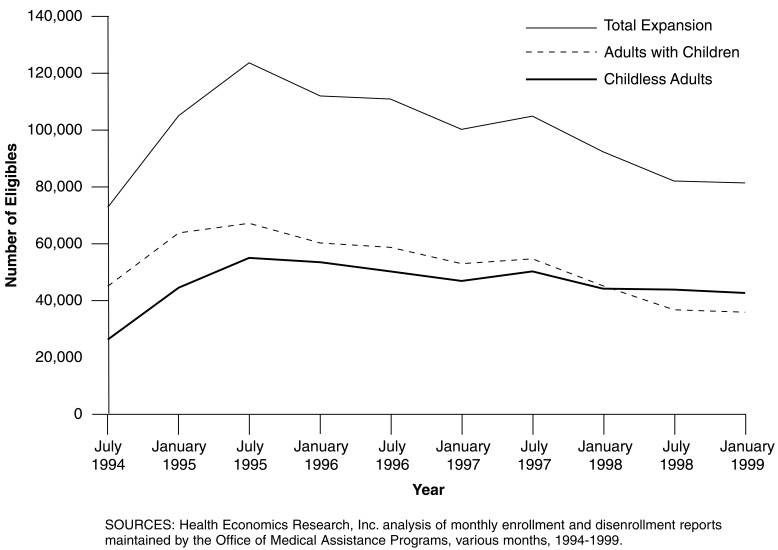

The expansion program has been extremely successful at enrolling uninsured Oregonians in Medicaid. It is estimated that the program enrolled 64 percent of the potentially eligible population in 1996 (Lipson and Schrodel, 1996). Over the first 5 years of OHP operation, the eligibility expansion extended Medicaid coverage to nearly 428,000 individuals. The vast majority (over 80 percent) were adults. The expansion population grew far more rapidly than anticipated, peaking during the program's second year at more than 134,000 eligibles. However, it subsequently declined to just over 81,000 by January 1999, the end of the fifth year (Figure 1).3 The decrease in the number of eligibles occurred among both adults with children and childless adults. However, as shown in Figure 1, the decline between July 1997 and July 1998 was far more precipitous for the adults with children category. This is partly explained by the movement of children out of this category following the implementation of Oregon's SCHIP program. A variety of other explanations have been advanced to explain the declining size of the expansion population, including the imposition of a premium requirement (Haber, Mitchell, and McNeill, 2000), a robust economy, and several changes in eligibility requirements.4

Figure 1. Trends in Number of Expansion Eligibles: 1994-1999.

The expansion population quickly became a very significant portion of Oregon's Medicaid program. In mid-1995, expansion eligibles comprised 40 percent of the Phase 1 population5 and 33 percent of the total Medicaid population. Despite the reduction in the number of expansion eligibles, they still accounted for 32 percent of Phase 1 eligibles and 24 percent of all Medicaid eligibles in January 1999.

This article describes Oregon's experience with its eligibility expansion, including sociodemographic and other characteristics of the expansion population, its service use, and the continuity of coverage provided. In addition to profiling the expansion population generally, we contrast experience for adults with children and childless adults. OHP's experience with adults with children is of particular policy relevance in light of new opportunities for covering higher income families under the SCHIP program. Oregon's experience can help answer the following important questions for other States looking to Medicaid eligibility expansions as a way of covering adult populations that fall outside of traditional eligibility categories: How effective are Medicaid expansions for increasing insurance coverage? Do they crowd out private insurance? Do they provide continuous insurance coverage or do beneficiaries enroll episodically when they become ill? Do these programs enroll sick populations with high service use? Are there systematic differences between adults with and without children?

Previous Research on Eligibility Expansions

Many States have expanded Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women and children by raising allowable income and asset levels or otherwise relaxing eligibility criteria. Far fewer have targeted the populations that fall outside of traditional Medicaid eligibility categories: adults under age 65 in two-parent families6 and childless adults under age 65. To date, 11 States (including Oregon) and the District of Columbia have enacted such expansions.7

Interest in public sector initiatives to expand coverage of higher income and two-parent families has grown in recent years, particularly since the advent of the SCHIP program. States may use SCHIP funds to purchase family coverage if (1) they can demonstrate that it is more cost effective than covering only the children, and (2) the coverage meets Title XXI of the Social Security Act standards, including minimum benefit and maximum cost-sharing requirements. Although there is considerable interest in making use of this option, States have found it difficult to meet these SCHIP requirements and, to date, only Massachusetts, Wisconsin, and Mississippi have approved programs that cover parents. Since welfare reform, Section 1931 of the Social Security Act also gives States the option of covering two-parent families without a waiver.

There has been relatively little research on characteristics of the expansion populations covered under existing State programs, in part because most are relatively new. Several studies have examined one of the older programs, Washington's Basic Health Plan (BHP), which was implemented in 1988. BHP enrolled both adults and children, and findings reported here include both groups.

One BHP study found substantial differences between enrollees and those who were eligible, but not enrolled, in terms of education, age, income, employment status, race, and insurance status (Diehr, Madden, Martin, et al., 1993). However, they did not differ on most measures of health status and the few significant differences tended to show that enrollees were in better health. Enrollees also had similar or lower utilization at baseline compared with eligible non-enrollees and, after 1 year of enrollment, compared with insured non-enrollees. A later study found no evidence of pent-up demand (Martin, Diehr, Cheadle, et al., 1997). Although 85 percent of BHP members had some service use during their first year of enrollment, use was fairly stable when measured in 6-month blocks over the course of the first 2 years of enrollment. A third study found that BHP enrollees had similar utilization patterns compared with employer-sponsored groups enrolled in the same health maintenance organizations, although their health status was somewhat poorer (Kilbreth, Coburn, McGuire, et al., 1998). However, the absence of adverse selection and pent-up demand in the BHP may be explained by the program's exclusion of coverage for pre-existing conditions during the first year of enrollment. In contrast, OHP provides immediate coverage once eligibility is approved.

A study of a non-Medicaid program compared members that enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Colorado through a premium subsidy program for the uninsured (sponsored by Kaiser) with a random sample of new commercial enrollees (Bograd, Ritzwoller, Calonge, et al., 1997). The groups did not differ in their use of hospital services or outpatient laboratory, pharmacy, and radiology services. After controlling for age and sex differences, enrollees in the premium subsidy program were 30 percent more likely to have an outpatient visit. This difference was mostly attributable to specialty care. One-half of the difference in outpatient use was explained by the poorer health status of the premium subsidy population, although the explanatory power of health status was largely confined to children, and only had a small effect for adults. Both the premium subsidy and commercial populations had higher rates of service use early in their enrollment; however, this start-up effect was similar for the two groups.

Data Sources

The analyses in this article rely on two complementary data sources. Some analyses draw on a telephone survey of OHP expansion beneficiaries. In addition, we analyze Medicaid eligibility, claims, and encounter data maintained by the Office of Medical Assistance Programs (OMAP), the State agency that administers OHP. To the extent that survey and administrative data provide overlapping information, we draw on both to enrich our profile of the expansion population.

The survey provides richer data on many issues, such as sociodemographic characteristics and health status, than are available in the administrative data. However, the survey only reflects experience at a point in time and, as described later, it is restricted to OHP recipients with essentially a full year of continuous eligibility. Many Medicaid beneficiaries receive episodic coverage and the majority of the expansion population is eligible for less than a year. It is likely that there are systematic differences within the expansion population based on length of eligibility.8 As a result, the survey sample may not be representative of the full OHP population. However, we are able to address some of the limitations of survey data by also analyzing administrative data that provide information on eligibility and service use. Unlike the survey data, administrative data are available for multiple years, which allows us to capture experience over the life of the program. Furthermore, these data include the universe of OHP recipients, including those eligible for less than a full year.

The survey includes data on self-reported utilization and information on service use (e.g., prescription drugs) that is not available in claims and encounter data. However, because of difficulties in obtaining accurate self-reports of utilization, respondents are mostly asked whether they received a given type of service, but not the quantity of services. In contrast, claims and encounter data allow us to measure the number of services received, which reflects both the probability of use and intensity of use. However, encounter data may substantially underrepresent the volume of services actually provided. Underreporting of encounter data by managed care plans has been a persistent problem in OHP, as it is in most managed care programs. We mainly use claims and encounter data to compare utilization of adults with children to that of childless adults. Since we are interested in relative utilization, rather than absolute levels of service use, and we do not have any reason to suspect that underreporting varies by eligibility category, this mitigates concerns about the completeness of encounter data reporting.9

All analyses are restricted to adults age 19 or over because the expansion population has been primarily adult since its inception. With the implementation of Oregon's SCHIP program, the expansion population is now exclusively adult.

Survey Design and Analytic Method

Survey data are drawn from a 1998 telephone survey of a statewide, random sample of expansion-eligible OHP adults age 19-64.10 State eligibility files were used to construct the sampling frame. The sampling frame was defined as people eligible in one of the expansion categories in January 1998 and who had been enrolled in OHP for at least 10 of the previous 12 months. A total of 903 expansion beneficiaries responded to the survey, representing a response rate of 76 percent. This response rate meets or exceeds those achieved in other published surveys of Medicaid populations (Coughlin and Long, 1999; Sisk, Gorman, Reisinger, et al., 1996). The response rates for adults with children and childless adults were 75 and 77 percent, respectively.

Among other issues, the survey included questions on respondent sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and service use. Within the expansion population, we compare adults with children to those without. Chi-square tests were used to determine the statistical significance of all categorical variables and t-tests were used for continuous variables. We also used logistic regression to analyze the probability of using a variety of services, holding constant sociodemographic and health status characteristics that could explain utilization differences. Covariates included age, race, sex, marital status, education, employment status, geographic location, and health status. All survey data analyses are weighted to adjust for non-response in order to represent the study population. Due to the complex sample design, descriptive and multivariate analyses used SUDAAN to make weighting and standard error adjustments.

Administrative Data

Monthly Medicaid eligibility files, which identify eligible beneficiaries as of the first of the month, were used to identify characteristics of the expansion population and to construct eligibility spells. A spell is defined as a period of uninterrupted eligibility. Because Medicaid beneficiaries may lose eligibility briefly (e.g., if they do not reapply on time) we consider people with a 1-month break in coverage to be continuously eligible. In addition, we linked claims and encounter data to eligibility data to examine service use.11

Eligibility data were available from the initiation of OHP in 1994-1998. Claims and encounter data were available for services provided in 1996 and 1997. As previously noted, encounter data may substantially underreport the quantity of services actually provided. The quality of encounter data reporting improved considerably after OMAP announced that they would use encounter data from 1996 onward to set capitation rates and risk adjust payments to plans. Thus, the completeness of encounter data for the early years of OHP (1994 and 1995) is considerably poorer than for subsequent years. However, previous analyses indicated that the quality of encounter data reported for 1996 and 1997 was adequate for use in this study. Because of the lag in reporting encounters, complete data for 1998 were not available in time for inclusion in this study.

Administrative data are used to profile characteristics, services use, and eligibility patterns of the expansion population generally, and to contrast adults with and without children. Because data represent the universe of expansion beneficiaries, we do not test for the statistical significance of differences between these groups. In addition, we estimated a proportional hazard model for length of eligibility. Because Medicaid beneficiaries are eligible for differing lengths of time, and service use is observed over varying periods, utilization was transformed to annual use rates.12 Observations are then weighted by the fraction of the year a person was eligible to accurately estimate average annual costs.

Expansion Population Characteristics

Table 1 displays survey findings on characteristics of the expansion population, overall, and by eligibility category. On average, expansion population survey respondents were age 42. Sixty percent are female and over one-third are married. Reflecting the Oregon population as a whole, the vast majority of expansion beneficiaries in both categories are white and non-Hispanic. Almost 80 percent of expansion beneficiaries have a high school education or higher and, of these, nearly one-half have some college education. A surprisingly high percentage of expansion beneficiaries reported that they were employed (45 percent), and in more than one-half of the expansion households either the respondent or spouse was working. Despite the reasonably high employment rate, income levels are low, with nearly two-thirds earning $6,000 or less annually.

Table 1. Characteristics of Expansion Population Survey Respondents.

| Characteristic | All Expansion (n=903) |

Adults with Children (n=349) |

Childless Adults (n=554) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age | 42.3 | 36.9 | **45.8 |

| Percent | |||

| Female | 60.4 | 68.6 | **55.0 |

| Married | 35.8 | 58.5 | **21.1 |

| Race/Ethnicity1 | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 86.5 | 85.2 | 87.4 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| Hispanic | 3.6 | 5.5 | 2.4 |

| Asian | 2.3 | 3.0 | 1.8 |

| Native American | 5.5 | 4.5 | 6.2 |

| Other | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Education1 | |||

| Less than High School | 22.6 | 18.1 | 25.4 |

| High School Graduate | 39.8 | 43.7 | 37.2 |

| Attended College/College Graduate | 37.7 | 38.2 | 37.3 |

| Respondent Employed | 44.9 | 56.2 | **37.5 |

| Respondent and/or Spouse Employed | 53.9 | 74.5 | **40.5 |

| Family Income1 | |||

| Less than $6,000 | 63.7 | 46.2 | **75.1 |

| $6,001-$10,000 | 14.8 | 13.7 | 15.5 |

| $10,001-$18,000 | 15.4 | 28.1 | 7.2 |

| More than $18,000 | 6.0 | 12.0 | 2.2 |

| SF-12 Score2 | |||

| Physical Health | 44.4 | 47.9 | **42.2 |

| Mental Health | 48.4 | 49.6 | *47.6 |

| Disability Prevents Respondent from Working (Percent Yes) | 26.5 | 11.1 | **36.5 |

Significant at p<0.05 compared with adults with children.

Significant at p<0.01 compared with adults with children.

Percentages sum to 100 percent within category by column.

A higher score indicated better health status.

SOURCE: Health Economics Research, Inc. and Research Triangle Institute Survey, 1998.

The expansion population is in fairly poor health. Table 1 reports three measures of health status: (1) the SF-12 physical health score; (2) the SF-12 mental health score; and (3) whether a disability prevents the respondent from working. The last variable may capture chronic conditions or impairments not captured by either of the SF-12 scales. SF-12 scores are scaled to a mean of 50 for the U.S. population as a whole, with a higher score indicating better health. The expansion population reports somewhat poorer physical and mental health status than the general population. In addition, just over one-quarter of expansion population respondents indicated that they could not work because of a disability.13

Adults without children differed significantly from adults with children on nearly every dimension examined. Adults without children are, on average, nearly 10 years older than those with children and they are significantly less likely to be female. Adults without children are about one-third as likely to be married (21 percent compared with 59 percent for adults with children). Childless adults were significantly less likely to be employed; 41 percent reported that either they or their spouse was employed compared with three-quarters of those with children. In addition, adults without children have a significantly lower income distribution, with three-quarters earning $6,000 or less as compared with 46 percent of adults with children. Adults without children report significantly poorer health status than those with children along all three dimensions. Most strikingly, more than one-third (and nearly 60 percent of those who are unemployed) report that a disability prevents them from working. By comparison, just over 10 percent of adults with children (one-quarter of those who are unemployed) had such a disability.

One concern about using Medicaid eligibility expansions to cover the uninsured is the potential for publicly provided insurance to crowd out private insurance. Based on survey responses (Table 2), this does not appear to be a major problem in OHP. Overall, less than 9 percent of expansion beneficiaries reported having access to employer-based insurance and 74 percent were uninsured prior to joining OHP. Only 15 percent were insured through an employer before they joined OHP and, of these, only 27 percent (approximately 4 percent of all expansion respondents) enrolled because their employer dropped their insurance coverage. Childless adults were only one-third as likely as those with children to have access to employer-based insurance (5 percent versus 15 percent) and were more likely to have been uninsured prior to enrolling in OHP (78 percent versus 68 percent). Adults without children were less likely than those with children to have been insured by an employer prior to joining OHP (13 versus 18 percent). Of those with employer-based insurance, childless adults were significantly less likely to have joined OHP because their employer stopped offering insurance (24 versus 29 percent).

Table 2. Availability of Insurance to Expansion Population Survey Respondents.

| Coverage | All Expansion (n=903) |

Adults with Children (n=349) |

Childless Adults (n=554) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Percent | |||

| Currently Eligible for Insurance Through Employer | 8.7 | 14.6 | **4.9 |

| Kind of Insurance Prior to Joining OHP1 | |||

| Uninsured | 73.9 | 68.1 | **77.7 |

| Through Employer | 15.1 | 18.3 | 13.0 |

| Medicaid | 3.4 | 5.5 | 2.0 |

| Purchased Directly from Insurer | 3.4 | 4.3 | 2.8 |

| Other | 4.2 | 3.6 | 4.5 |

| Joined OHP Because Employer Dropped Coverage2 | 26.5 | 29.2 | **23.5 |

Significant at p<0.01 compared with adults with children.

Percentages sum to 100 percent within category by column.

Of those insured through employer prior to OHP.

NOTE: OHP is Oregon Health Plan.

SOURCE: Health Economics Research, Inc. and Research Triangle Institute Survey, 1998.

Analyses of OHP eligibility files revealed some important differences in the demographic characteristics of the expansion population compared with survey findings. Eligibility data show that the expansion population has a mean age of 35, considerably younger than 42, as reported in the survey. Eligibility data also indicate a more equal sex mix in the expansion population, with only 53 percent female, as compared with 60 percent in the survey data. Indeed, based on eligibility files, the majority of new adults/couples are male. In addition, the eligibility files show that Hispanics comprise twice as large a share of the expansion population than is indicated by the survey data (7.2 percent versus 3.6 percent).

Inconsistencies between survey data and the eligibility files are explained by a variety of factors, including different reference periods and differences between the survey population and the overall population of expansion eligibles. As previously discussed, the survey includes only beneficiaries with essentially a full year of eligibility and these beneficiaries are not representative of the overall expansion population. As discussed later, eligibility spell length increases with age and the female sex, so that expansion beneficiaries with a full year of eligibility are older and more likely to be female than the overall population. In addition, eligibility files show that females constitute an increasing share of the expansion population over time, while Hispanics constitute a declining share of the expansion population. Therefore, one would expect a greater representation of females and a lesser representation of Hispanics in the survey, which reflects eligibles as of January 1998, compared with eligibility data covering 1994-1998.

Service Use

As previously mentioned, expansion beneficiaries are in relatively poor health. Indeed, service use by expansion beneficiaries, particularly childless adults, has been higher than initially projected. In addition, plans contend that the expansion program is subject to adverse selection because beneficiaries tend to become eligible during an episode of illness and, in many cases, do not re-enroll at the end of their guaranteed 6-month period of eligibility unless they have ongoing service needs.14 The following sections use survey data, as well as claims and encounter data, to examine the level of service use by expansion beneficiaries and evidence of adverse selection.

Several important differences between survey and administrative data should be kept in mind when comparing utilization findings from these two data sources. Most importantly, a number of factors will tend to produce higher utilization estimates from the survey compared with encounter and claims data. The survey sample included only beneficiaries with a full year of eligibility, and these beneficiaries are likely to be higher service users than the expansion population as a whole. Our analyses of administrative data, on the other hand, did not place any restrictions on length of eligibility. Second, about 15 percent of expansion beneficiaries have some period of OHP eligibility in a non-expansion category during the course of a year.15 To eliminate complications introduced by these eligibility transitions, our estimates of service use based on claims and encounter data are confined to beneficiaries that are exclusively eligible in an expansion category. Some survey respondents, however, may have had some period of coverage in a non-expansion category during the year. Analyses of claims and encounter data showed that these beneficiaries have higher annual service use than those eligible exclusively in expansion categories. Finally, as discussed earlier, encounter data underreport services provided. Therefore, we expect that our claims and encounter data analyses understate levels of service use; however, we do not expect this underreporting to bias comparisons of relative service use between groups.

Levels of Service Use

Survey Data

Table 3 shows survey findings on utilization of health services for the expansion population, overall, and by eligibility category. More than two-thirds of expansion beneficiaries visited a physician within 3 months of responding to the survey. Those who reported visiting a physician averaged three visits during the 3-month period. Of expansion beneficiaries 15 percent had visited the emergency room during the past 3 months. Healthy, non-pregnant adults are unlikely to visit the physician more than once a year so that the percent with a physician visit in the past 12 months may be a more useful measure. Looking back over a 1-year time period, 90 percent of expansion beneficiaries saw a physician at least once.

Table 3. Utilization of Health Care Services, by Expansion Population Survey Respondents.

| Health Care Service | All Expansion (n=903) |

Adults with Children (n=349) |

Childless Adults (n=554) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician Visits in Past 3 Months | |||

| Percent with at Least 1 Visit | 68.8 | 64.5 | *71.6 |

| Number of Visits (Users Only) | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.5 |

| Percent with Emergency Room Visits in Past 3 Months | 14.6 | 10.6 | **17.2 |

| Percent with Use in Past 12 Months | |||

| Physician Visit | 89.2 | 88.0 | 90.0 |

| Routine Physical/Check-up | 55.4 | 53.1 | 56.9 |

| Blood Pressure Check | 86.2 | 82.3 | *88.7 |

| Pap Test (Females Only) | 58.9 | 59.8 | 58.1 |

| Mammography (Females Age 40 or Over) | 47.9 | 35.7 | *52.1 |

| Visit to Specialist | 43.3 | 34.6 | **49.0 |

| Hospital Admission | 11.6 | 9.1 | 13.2 |

| Visit to Dentist | 57.3 | 62.5 | *54.0 |

| Prescription for Medicine | 84.0 | 81.4 | 85.7 |

| Mental Health/Substance Abuse Treatment | 14.6 | 12.5 | 16.0 |

Significant at p<0.05 compared with adults with children.

Significant at p<0.01 compared with adults with children.

SOURCE: Health Economics Research, Inc. and Research Triangle Institute Survey, 1998.

Slightly over one-half of expansion beneficiaries received a routine physical exam in the past 12 months, and almost 90 percent had their blood pressure checked. Females were asked whether they had two preventive tests during the past year: a Pap smear; and for those age 40 or over a mammogram. Nearly 60 percent of expansion beneficiaries had a Pap smear, and just under one-half received a mammogram.

Over 40 percent of expansion beneficiaries saw a specialist during the preceding 12 months and 12 percent were hospitalized. Nearly three-fifths visited a dentist. Utilization of prescription drugs is quite high, with 84 percent having at least one prescription during the past year. Fifteen percent received mental health/substance abuse (MH/SA) treatment services.

Childless adults generally have higher service use than those with children. For example, 72 percent of adults without children, compared with 65 percent of adults with children, had at least one physician visit in the past 3 months; however, the difference disappears over a 12-month recall period. Nearly one-half of adults without children saw a specialist, while only about one-third of those with children did so. Childless adults were also more likely to have an emergency room visit. However, service use differences between these groups disappear after controlling for sociodemographic and health status characteristics in multivariate analyses.16 Based on the regression findings it appears that higher service use by childless adults is largely driven by their poorer physical and mental health status.

Claims and Encounter Data

Average annual service use for the expansion population based on claims and encounter data is shown in Table 4. Expansion beneficiaries have approximately 11 inpatient admissions per 100 beneficiaries during the course of a year. There is an average of 8 emergency room visits annually per 100 expansion beneficiaries. The evaluation and management visit rate is fairly high, 303 per 100 beneficiaries, or more than 3 per person each year. Expansion beneficiaries also have high use of MH/SA services, making nearly three visits, per person, each year. These extremely high utilization rates are explained by use of methadone treatment services. Beneficiaries may receive treatment on a daily basis, and each visit is reported separately. Dental services are also widely used, with each beneficiary having an average of almost 1.5 visits per year. The need for dental services was often cited as an important motivation for enrolling in OHP in focus groups of expansion beneficiaries.17

Table 4. Annual Service Use for Expansion Beneficiaries1.

| Service Use | All Expansion (n=185,011) |

Adults with Children (n=78,901) |

Childless Adults (n=106,110) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient Admissions | 11 | 6 | 15 |

| Emergency Room Visits | 8 | 5 | 10 |

| Evaluation and Management Visits | 303 | 258 | 336 |

| Mental Health/Substance Abuse Visits | 272 | 117 | 384 |

| Dental Visits | 146 | 139 | 151 |

Rates per 100 beneficiaries.

NOTES: Analyses only include beneficiaries who are exclusively eligible in an expansion category. Significance levels are not reported because data represent the universe of these expansion eligibles.

SOURCE: Health Economics Research, Inc. analysis of claims, encounter, and eligibility files maintained by Office of Medical Assistance Programs, 1996 and 1997.

Claims and encounter data show that childless adults consistently use more of all types of services than do those with children. Childless adults have more than twice as many inpatient admissions, twice as many emergency room visits, more than three times as many MH/SA visits, and 30 percent more evaluation and management visits. Encounter data generally confirm survey findings of higher service use by childless adults. The exception is dental services—while survey data showed that adults with children were significantly more likely to visit the dentist at least once, encounter data show that childless adults use slightly more dental services during the course of the year. Because the survey only reports the probability of using a dental service, these conflicting findings could be explained by greater service intensity for those childless adults with service use.

Adverse Selection

In focus groups of expansion beneficiaries, the need for emergency care was most often mentioned as the motivation for joining OHP. In addition, many of those who allowed their coverage to lapse did not want to complete the paperwork necessary to renew their eligibility if they did not have an immediate need for services, particularly because they knew they could re-enroll in the future if they became ill. Analyses reported in Haber, Mitchell, and McNeill (2000) show that beneficiaries who use services are significantly more likely to recertify at the end of a 6-month eligibility period. The impact of prior service use is particularly strong for childless adults.

Our survey asked respondents to identify the most important reason for having insurance. The expansion population most commonly cited the need to pay for a current medical condition (40 percent), followed by the need to pay for a possible accident or illness (34 percent). The remaining 27 percent identified the need to pay for routine check-ups. Childless adults were significantly more likely than those with children to cite the need to pay for a current medical condition (49 percent compared with 25 percent). In contrast, the predominant reason for adults with children was paying for a possible accident or illness (41 percent, compared with 29 percent of childless adults).

These responses give credence to the contention that expansion beneficiaries, particularly childless adults, are likely to enroll when they have an immediate need for services. In order to assess whether expansion beneficiaries do, in fact, enroll during episodes of illness, we analyze service use during the first month of an expansion eligibility spell. If expansion beneficiaries are likely to enroll in OHP because they become ill, their service use in the first month of a spell should be disproportionately high relative to average use over the course of a spell. Table 5 shows the percentage of expansion eligibles with selected measures of service use during the first month of an eligibility spell, and service use in the first month of a spell relative to average monthly use over the course of a spell.18

Table 5. Service Use During the First Month of an Eligibility Spell.

| Service Use | All Expansion | Adults with Children | Childless Adults |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Month of Eligibility Spell | Percent | ||

| Any Use | 50.3 | 43.5 | 55.8 |

| Any Inpatient Admissions | 1.5 | 0.8 | 2.1 |

| Any Emergency Room Visits | 1.6 | 1.1 | 2.1 |

| Any Evaluation and Management Visits | 23.3 | 21.2 | 25.0 |

| Any Mental Health/Substance Abuse Visits | 4.5 | 2.2 | 6.4 |

| Any Dental Visits | 9.6 | 8.7 | 10.3 |

| First Month of Eligibility Spell Relative to Average Monthly Use | Ratio | ||

| Inpatient Admissions | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.7 |

| Emergency Room Visits | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.7 |

| Evaluation and Management Visits | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Mental Health/Substance Abuse Visits | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| Dental Visits | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

NOTES: Analyses only include beneficiaries who are exclusively eligible in an expansion category. Significance levels are not reported because data represent the universe of these expansion eligibles.

SOURCE: Health Economics Research, Inc. analysis of claims, encounter, and eligibility files maintained by Office of Medical Assistance Programs, 1996 and 1997.

Of expansion beneficiaries 50 percent use some services during their first month of eligibility. Evaluation and management services are the most commonly provided, with 23 percent of expansion beneficiaries receiving at least one. The next most prevalent are dental services, used by 10 percent of expansion eligibles in the first month. Less than 2 percent have a hospital admission during the first month.19 Childless adults are more likely to have service use in the first month than adults with children and this greater likelihood is found in all categories of use.

Expansion beneficiaries tend to use services most intensively during the initial month of an eligibility spell (Table 6). All categories of service show proportionately higher use in the first month compared with average monthly use over the course of the spell. Notably, inpatient and emergency room use is more than twice as high in the first month. Adults without children use proportionately more services in the first month compared with those with children.

Table 6. Patterns of Oregon Health Plan Eligibility: 1994-1998.

| Patterns of Eligibility | All Expansion | All Adults with Children | All Childless Adults | Expansion Only |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Months of Eligibility per Spell1 | 9.5 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 10.0 |

| Total Months of Eligibility1 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 14.2 |

| Percent | ||||

| 1 Eligibility Spell1 | 67.9 | 66.2 | 69.6 | 69.0 |

| 6 or Fewer Months of Eligibility1 | 39.8 | 38.8 | 40.7 | 39.9 |

| Potential Eligibility Period Covered2 | 45.0 | 46.2 | 43.9 | 39.6 |

For expansion beneficiaries with some period of coverage in non-expansion categories, includes only periods of coverage in expansion eligibility categories.

Percent of time from when a beneficiary is first eligible through December 1998 is used as a gross measure of maximum potential eligibility. This may understate or overstate the actual time period during which a beneficiary met Oregon Health Plan's eligibility requirements.

SOURCE: Health Economics Research, Inc. analysis of eligibility files maintained by Office of Medical Assistance Programs, 1994-1998.

These findings support the hypothesis that expansion beneficiaries tend to enroll when they are in need of services. They particularly reinforce the impression that an immediate need for care is a more important factor in the enrollment decision for childless adults than for those with children. However, only a small proportion have an emergency room visit or a hospitalization, suggesting that critical care needs are not driving the decision to enroll. Similarly, we did not find that the diagnosis related groups for admissions that occurred during the first month of an eligibility spell were associated with traumas or emergency conditions.

Continuity of Coverage

In this section, we examine whether expansion beneficiaries receive continuous coverage through OHP or whether they enroll episodically, dropping out after their immediate need for services ends and re-enrolling if they become ill later. Continuity of coverage is particularly important in capitated programs such as OHP because plans do not have an opportunity to manage care if their members only enroll when they are ill.

To examine this issue, we used OHP eligibility files to analyze eligibility spells for expansion beneficiaries with some eligibility in the first 5 years of OHP. Although eligibility data are truncated at December 1998, our analyses included only beneficiaries who first became OHP-eligible prior to August 1998. Therefore, we should be able to observe the full extent of at least one 6 month period of guaranteed OHP eligibility for everyone in these analyses.20

Patterns of OHP Eligibility

In general, the expansion population receives fairly brief coverage under OHP. Expansion eligibles are covered an average of 10 months per spell, and an average of 14 months across all spells (Table 6). Forty percent have 6 or fewer months of eligibility, indicating that they did not re-enroll after an initial 6-month period of guaranteed eligibility. On the other end of the spectrum, 2 percent have 4 or more years of eligibility and have been enrolled virtually continuously since the program's inception.

We do not find patterns of repeated enrollment and disenrollment among expansion eligibles. Over two-thirds have a single spell of expansion coverage. However, 9 percent have three or more spells. For those with multiple spells, the gap between spells averages just under 10 months. Expansion beneficiaries are covered less than one-half of the time that they potentially could be covered. We count the time from when a beneficiary is first eligible through the end of our study period (December 1998) as a gross measure of maximum potential eligibility.21 Using this definition, on average, expansion eligibles were covered 45 percent of the potential eligibility period.22

Although we expected childless adults to enroll more episodically because they are responding to an immediate need for care, descriptive analyses show that they are covered for somewhat longer periods than adults with children. They are also more likely to have a single eligibility spell. The distribution of spell lengths appears to be somewhat more skewed for childless adults, with higher proportions having both very short and very long periods of coverage

Expansion beneficiaries that are eligible exclusively in expansion categories receive slightly more continuous coverage through the expansion program than do those with mixed eligibility. They are somewhat more likely to have a single eligibility spell and to be eligible for 4 or more years. However, they are covered for a shorter portion of the time they potentially could be covered (40 percent).

Duration of Expansion Eligibility Spells

We estimated a proportional hazard model to identify the impact of beneficiary characteristics on the duration of an expansion eligibility spell.23 The proportional hazard model takes into account right-hand censoring of spell duration for beneficiaries with an eligibility spell that was ongoing in December 1998.24 Demographic characteristics included dummy variables for age (26-34, 35-44, 45-54, and age 55 or over, with age 19-25 constituting the omitted category), being white, female, and English-speaking. Two dummy variables captured location of residence: whether the respondent lived in an urban area outside of the tri-county Portland metropolitan statistical area or in a rural area (with residents of the tri-county area as the omitted group).25 An additional dummy variable controlled for whether the beneficiary qualified as an adult with children rather than a childless adult. We hypothesized that childless adults might be more likely to seek coverage episodically during a spell of illness. We further hypothesized that beneficiaries who had been eligible for long periods in the past are likely to have subsequent spells of longer duration. Therefore, we also controlled for the number of months of OHP eligibility in any eligibility category prior to the current spell.

The results of the proportional hazard model are presented in Table 7. A negative coefficient, and a risk ratio less than 1, indicates a smaller likelihood of a spell ending and, hence, a longer eligibility spell. Nearly every variable in our model is highly significant. Dummy variables for age indicate that spell duration increases with age. White persons have longer spells than non-white persons and females have longer spells than males. Surprisingly, English-speaking individuals have significantly shorter spells.26 However, this is consistent with findings reported in Haber, Mitchell, and McNeill (2000) that English-speaking expansion eligibles are less likely to recertify their OHP coverage at the end of a 6-month eligibility period. As compared with beneficiaries residing in the Portland metropolitan statistical area, residents of other urban counties have significantly longer spells, whereas, there is no difference for residents of rural counties. As predicted (and in contrast to our descriptive findings), after controlling for other characteristics, expansion beneficiaries with children have significantly longer eligibility spells than those without children. On the other hand, the duration of an eligibility spell was significantly shorter for those who had long periods of prior eligibility.

Table 7. Proportional Hazards Model for Duration of Expansion Eligibility Spell, by Independent Variable.

| Independent Variable | Mean | Risk Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 26-34 Years | 0.298 (0.457) |

***0.860 |

| 35-44 Years | 0.273 (0.445) |

***0.743 |

| 45-54 Years | 0.140 (0.347) |

***0.623 |

| 55 Years or Over | 0.059 (0.236) |

***0.561 |

| White | 0.841 (0.366) |

***0.907 |

| Female | 0.481 (0.500) |

***0.896 |

| English-Speaking | 0.939 (0.240) |

***1.105 |

| Resident of Urban Area (Excluding Portland) | 0.287 (0.452) |

***0.982 |

| Resident of Rural Area | 0.361 (0.480) |

1.005 |

| Adults with Children | 0.450 (0.498) |

***0.973 |

| Prior Months of OHP Eligibility | 6.074 (10.078) |

***1.008 |

Significant at p <0.0001.

NOTES: N =412,068. Standard deviations are in parenthesis. OHP is Oregon Health Plan.

SOURCE: Health Economics Research, Inc. analysis of eligibility files maintained by Office of Medical Assistance Programs, 1994-1998.

Conclusions

Based on Oregon's experience, Medicaid eligibility expansions can be an effective mechanism for providing health care coverage to low-income uninsured populations. OHP rapidly enrolled large numbers of people through its expansion program, far exceeding the state's estimates in the early years. While the size of the expansion population has tapered off subsequently, it remains a very significant component of Oregon's Medicaid program. Nonetheless, OHP's eligibility expansion has not eradicated the problem of the uninsured in Oregon—although the rate dropped as low as 17 percent in 1996, it is estimated that 23 percent of the population living below the FPL remained uninsured in 1998 (Office for Oregon Health Plan Policy and Research, 1999).

Discussions of programs designed to reduce the uninsured population through expansion of public insurance, most notably the recent SCHIP legislation, have been marked by debate about the extent to which they will crowd out private insurance. Although OHP did not incorporate any special provisions to mitigate crowd out, it does not appear that this has been a serious problem. The vast majority of beneficiaries covered under OHP's eligibility expansion were uninsured prior to enrolling, and only a small fraction had an alternate source of employment-based insurance. Indeed, only about one-half of the expansion population had an employed family member.

The extent to which Oregon's experience can apply, in general, to other States depends, in part, upon certain key program features, such as whether all adults are covered or only those with children, the length of guaranteed eligibility, and whether there is immediate coverage of all services without a waiting period. Oregon also has a more ethnically homogeneous population than many States. With these caveats in mind, Oregon provides a number of important lessons for other States.

Although OHP's eligibility expansion has been an effective mechanism for extending some coverage to low-income populations, the goal of providing continuous insurance coverage is more elusive. Most expansion beneficiaries are covered for brief periods of time and two-fifths never re-enroll after an initial 6-month guaranteed eligibility period. This episodic enrollment is particularly problematic for managed care plans that rely on continuity of coverage in order to control service use. On the other hand, it does not appear that a large proportion of expansion beneficiaries have a pattern of repeated enrollment and disenrollment.

Unfortunately, States may face serious challenges to encouraging more continuous enrollment. Procedurally, OHP has not made the re-enrollment process particularly onerous, although the imposition of premiums appears to have shortened the average length of eligibility. Nonetheless, beneficiaries have little incentive to re-enroll since they know they can receive immediate coverage in the future if they need it. While excluding coverage of pre-existing conditions or instituting a waiting period before benefits begin would reduce this disincentive to re-enroll, it would undoubtedly increase providers' uncompensated care burden. One simple option is to increase the period of guaranteed eligibility to a year, for example. However, in addition to increasing the likelihood that a person who is no longer eligible will remain enrolled, in a managed care program such as OHP, this also increases the likelihood that a State will continue making capitation payments for enrollees who are no longer using services through the program because they have moved out-of-State or have obtained private insurance.

Other States considering eligibility expansions similar to Oregon's should recognize that they will be enrolling a relatively unhealthy population with high service use rates. They are also likely to enroll in the program when they are sick and in need of care. While our findings differ from previous studies of Washington's Basic Health Plan (Dier, Madden, and Martin et al., 1993; Martin, Diehr, and Cheadle et al., 1997; and Kilbreth, Coburn, and McGuire et al., 1998) this may be explained by that program's exclusion of pre-existing conditions during the first year of enrollment, whereas OHP covers services from the date of application. As OHP has recognized, the adult expansion population is comprised of two very distinct groups. Childless adults who enrolled in OHP were significantly sicker and higher service users than adults with children. Their poorer health status and greater use may reflect higher levels of pent-up demand as they were also more likely to be uninsured prior to enrolling in OHP. While childless adults may be motivated to enroll by an immediate need for health care, parents of children may have been brought into the system when they were enrolling their children. Although children are covered under non-expansion categories, a caseworker who is enrolling a child in OHP may inform the parents of their own eligibility under the expansion program. Oregon's experience covering adults with children is of particular interest to other States that are exploring options for expanding coverage of families, e.g., through their SCHIP programs. Based on Oregon's experience, uninsured parents will be a less costly population for these States to include in their Medicaid program than other uninsured adults.

Footnotes

The authors are with Health Economics Research, Inc. The research presented in this article was performed under Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) Contract No. 500-94-0056. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Health Economics Research, Inc. or HCFA.

These eligibility groups are called OHP families and OHP adults/couples, respectively.

Poverty-level children born after this date already received Medicaid coverage under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act OBRA of 1989 and 1990 expansions that required all States to cover pregnant women and children under age 6 in families below 133 percent of the FPL, and children born after October 1, 1983, in families below 100 percent of the FPL.

Oregon's section 1115 waiver cost estimate assumed that the expansion would cover an average of 78,300 beneficiaries per month in the second year, increasing to 117,600 in the fifth year.

Beginning October 1, 1995, the basis for calculating financial eligibility was changed from the previous month's income only to the average of the most recent 3 months and an asset limit of $5,000 was imposed. Full-time college students were also excluded from expansion eligibility, although they were later reinstated on January 1, 1999.

Phase 1 of OHP, which began in February 1994, included TANF, OBRA, general assistance, and expansion eligibles. In January 1995, the aged, blind, disabled, and children in foster care were brought into OHP under Phase 2.

States may elect to cover adults in two-parent households where one of the parents is incapacitated or where the principal wage-earner works less than 100 hours per month. Prior to welfare reform, the principal wage earner also had to meet certain work history requirements (Guyer and Mann, 1998).

Refer to Lipson and Schrodel (1996) for information on State eligibility expansions. Information on section 1115 waiver programs implemented after this report was issued and is available at Internet address: http://www.hcfa.gov/medicaid

Results of analyses reported in Haber, Mitchell, and McNeill (2000) show that beneficiaries who used services were significantly more likely to recertify at the end of their 6-month guaranteed eligibility period than those who did not. Thus, the survey population, which has a full year of eligibility and has recertified at least once, will have higher service use than the overall OHP population.

Although managed care plans differ in the completeness of their encounter data reporting, there is no difference in the distribution of adults with children and childless adults across plans. Therefore, comparisons between these groups are not biased by differences across plans in the completeness of encounter date reporting.

The complete survey sample also included TANF beneficiaries and a comparison sample of Food Stamp recipients who were not enrolled in Medicaid. In addition, the survey covered children as well as adults. The analyses reported here are based on adult expansion population respondents only.

In order to capture all services received, our analyses include claims and encounter data. Services are reported in encounter data for the vast majority of expansion beneficiaries who are enrolled in a managed care plan. Claims data are reported for those beneficiaries who are not enrolled in a managed care plan. In addition, there is typically a lag between the time a beneficiary becomes eligible and the date enrollment in a plan becomes effective. However, beneficiaries may receive services as soon as they become eligible. Services delivered prior to plan enrollment are incurred as a fee-for-service liability to OHP and are reported in claims data.

The exception is utilization analyzes that are restricted to the first month of an eligibility spell since utilization was measured for a uniform time period for all beneficiaries. In addition, it is not possible to annualize the probability of using a service. The logistic regressions include a variable for length of eligibility to control for the greater likelihood of using services as the observation period increases.

This is self-reported disability; presumably these individuals do not satisfy the requirements for Medicare or Medicaid eligibility due to disability.

Plans assert that this pattern has been exacerbated by the imposition of premiums for the expansion population. Refer to Haber, Mitchell, and McNeill (2000) for a more detailed discussion.

The most common transitions are between TANF and expansion eligibility, which could occur because of changes in income.

Full results of our regression analyses are available from the authors.

Focus groups of expansion beneficiaries were conducted in Portland and Eugene, Oregon, in February 1999.

Beneficiaries who become eligible during the course of a hospital admission may not appear in the eligibility files for a month or so, although they receive retroactive coverage from the date of admission. In order to capture this service use, we counted either services received in the first month of an eligibility spell or services received in the month prior, if any.

It is likely that the understatement of hospital use is more serious than other services because underreporting of hospital encounters has been especially severe.

Nonetheless, 27 percent had fewer than 6 months of expansion eligibility, with most of these having 5 months. This is probably explained by beneficiaries who became eligible during the course of a hospital admission. While these beneficiaries receive retroactive coverage from the date of admission, they do not appear in the eligibility files for another month or so.

This is a gross measure of potential eligibility because it assumes that the individual still meets OHP eligibility criteria, has not obtained insurance outside of OHP, still resides in Oregon, and could not have been eligible prior to their first period of eligibility. The first three assumptions tend to overstate the potential eligibility period, while the fourth understates it.

This includes periods of coverage in non-expansion eligibility categories.

The model included only pure expansion eligibility spells (i.e., those that did not include any months in a non-expansion category) so that impacts on expansion eligibility would not be contaminated by time trends in Medicaid eligibility for other eligibility categories. For example, welfare reform may have decreased the duration of TANF eligibility.

Sixteen percent of the observations in our model were censored.

The tri-county Portland metropolitan area is defined as Multnomah, Clackamas, and Washington counties. Counties in a metropolitan statistical area outside of the tri-county area were categorized as “other urban.”

Language was not reported for eligibility spells in 1994. If a beneficiary had some period of eligibility in a later year, we assigned the language variable from those records to the 1994 observation. Observations for which we could not identify language (less than 4 percent of our sample) were omitted from our regressions.

Reprint Requests: Susan G. Haber, Sc.D., Health Economics Research, Inc., 411 Waverley Oaks Road, Suite 330, Waltham, MA 02452-8414. shaber@her-cher.org

References

- Bograd H, Ritzwoller DP, Calonge N, et al. Extending Health Maintenance Organization Insurance to the Uninsured: A Controlled Measure of Health Care Utilization. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997 Apr 2;277(13):1067–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin T, Long S. Impacts of Medicaid Managed Care on Adults: Evidence from Minnesota's PMAP Program. The Urban Institute; Washington, DC.: Feb, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Diehr P, Madden CW, Martin DP, et al. Who Enrolled in a State Program for the Uninsured: Was There Adverse Selection? Medical Care. 1993 Dec;31(12):1093–1105. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer J, Mann C. Taking the Next Step: States Can Now Take Advantage of Federal Medicaid Matching Funds to Expand Health Care Coverage to Low-income Working Parents. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; Washington DC.: Aug, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haber SG, Mitchell JB, McNeill A. Effects of Premiums on Eligibility for the Oregon Health Plan. Health Economics Research Inc.; Waltham, MA.: Oct, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbreth EH, Coburn AF, McGuire C, et al. State-Sponsored Programs for the Uninsured: Is There Adverse Selection? Inquiry. 1998 Fall;35(3):250–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipson DJ, Schrodel SP. State-Subsidized Insurance Programs for Low-Income People. Alpha Center; Washington, DC.: Nov, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Diehr P, Cheadle A, et al. Health Care Utilization for the “Newly Insured”: Results from the Washington Basic Health Plan. Inquiry. 1997 Summer;34(2):129–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for Oregon Health Plan Policy and Research. The Uninsured in Oregon. Salem, OR.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sisk JE, Gorman SA, Reisinger AL, et al. Evaluation of Medicaid Managed Care: Satisfaction, Access and Use. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996 Jul 3;276(1):50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]