Medicare in 1965

For persons who are trying to understand what we were up to, the first broad point to keep in mind is that all of us who developed Medicare and fought for it had been advocates of universal national health insurance. We all saw insurance for the elderly as a fallback position, which we advocated solely because it seemed to have the best chance politically Although the public record contains some explicit denials, we expected Medicare to be a first step toward universal national health insurance, perhaps with “Kiddicare” as another step… President Franklin Roosevelt feared that health insurance was so controversial, because of doctors' opposition, that if he included it in his program for economic security he might lose the entire program.

Robert M. Ball, Social Security Commissioner under Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, 1995

Enactment of Medicare

After President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided not to include health insurance in his proposed Social Security Act in 1934, he authorized his staff to do additional work on the proposal, including consultations with a broad array of groups (Corning, 1969). This work was subsequently incorporated into a national health insurance bill introduced in the Congress in 1943—commonly referred to as the Wagner, Murray, Dingell bill (Congressional Quarterly Almanac, 1965). In 1945, President Truman endorsed this bill and became the first president to send a national health insurance bill to the Congress. By the end of Truman's term, in 1952, Medicare was proposed as a scaled down version of national health insurance that would cover all Social Security beneficiaries—the elderly, widows, and orphans. President Eisenhower was opposed to social insurance for health care; in 1954, he proposed a Federal reinsurance plan for private insurance companies. President Kennedy's 1963 proposal for health care for the elderly passed the Senate in 1964, but failed in the House.

After more than a decade of debate on health insurance for the elderly, when Johnson was elected President in 1964, he asked Congress to give Medicare top priority. The earlier efforts towards national health reform finally resulted in coverage for the elderly (Medicare) and the poor (Medicaid), with advocates hoping that coverage would be expanded to other population groups at a later date. In honor of President Truman's leadership, President Johnson flew to the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri to sign the bill into law on July 30, 1965 and presented the first two Medicare cards to former President Truman and Mrs. Truman. Reflecting on the amount of time that had transpired, Johnson noted at the ceremony: “We marvel not simply at the passage of this bill, but what we marvel at is that it took so many years to pass it.” (Harris, 1966a).

Medicare Covers the Elderly in 1965

I am one of your old retired teachers that has been forgotten. I am 80 years old and for 10 years I have been living on a bare nothing, two meals a day, one egg, a soup, because I want to be independent. I am of Scotch ancestry, my father fought in the Civil War to the end of the war, therefore, I have it in my blood to be independent and my dignity would not let me go down and be on welfare. And I worked so hard that I have pernicious anemia, $9.95 for a little bottle of liquid for shots, wholesale, I couldn't pay for it.

Hearings of the Subcommittee on Problems of the Aged and Aging of the Committee of Labor and Public Welfare, 1959 (Stevens, 1996)

When Medicare was enacted in 1965, America was in many ways a different place than it is today.

Poverty

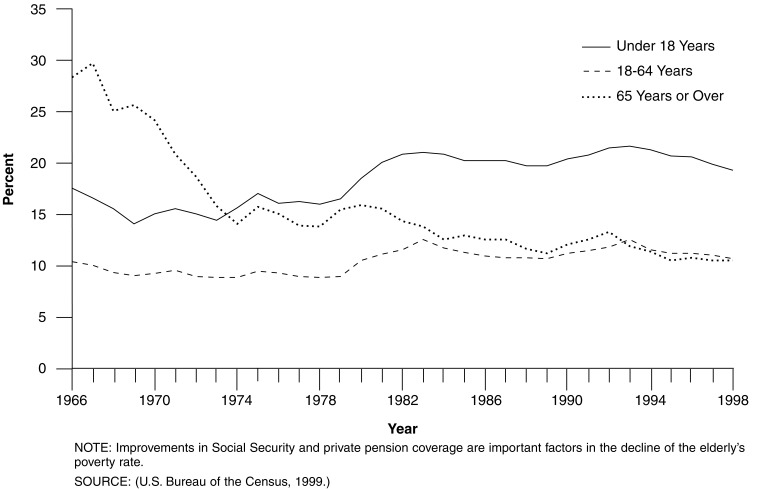

In 1965, the elderly were the group most likely to be living in poverty—nearly one in three were poor (Figure 1). Today, the poverty rate for the elderly is similar to that of the age group 18-64—about 1 in 10 are poor. Children are now the group most likely to be living in poverty.

Figure 1. Poverty Rates, by Age: 1966-1998.

Access to Care for Minorities

Before a hospital could be certified for Medicare, it had to do more than have a plan to end discrimination: It had to demonstrate nondiscrimination.

Segregation denied minorities access to the same health care as white persons. With the passage of the Civil Rights Act (recipients of Federal funds are prohibited from discrimination based on race) in 1964 and Medicare (the source of the Federal funds) in 1965, minorities were able to receive health care in the same hospitals and clinics used by white persons. More than 1,000 Medicare and Public Health Service staff worked with hospitals to make sure they understood they would have to serve all Americans when they signed up for the federally funded Medicare program.

Black hospitalization rates were about 70 percent of white hospitalization rates in the program's first few years. Over the next several years, hospitalization rates rose to comparable levels. In 1963, minorities age 75 or over averaged 4.8 visits to the doctor; by 1971, their visits grew to 7.3, comparable with white utilization rates (National Center for Health Statistics, 1963-1964; 1971).

While Medicare and Medicaid have contributed to considerable progress in the health of minorities, there is still room for improvement as disparities in health status, utilization, and outcomes persist today (Gornick, 2000).

Insurance Coverage

About one-half of America's seniors did not have hospital insurance prior to Medicare. By contrast, 75 percent of adults under age 65 had hospital insurance, primarily through their employer. For the uninsured, needing hospital services could mean going without health care or turning to family, friends, and/or charity to cover medical bills. More than one in four elderly were estimated to go without medical care due to cost concerns (Harris, 1966b).

Medicare, along with other programs, notably Social Security, and a strong economy, have greatly improved the ability of the elderly and the disabled to live without these worries. Medicare covers nearly all of the elderly (about 97 percent), making them the population group most likely to have health insurance coverage. Today, the groups least likely to have health insurance coverage are young people, Hispanics, and low-wage workers.

Medicare Modeled on Private Insurance Plans

We proposed assuring the same level of care for the elderly as was then enjoyed by paying and insured patients; otherwise, we did not intend to disrupt the status quo. Had we advocated anything else, it never would have passed.

Medicare's benefit package, administration, and payment methods were modeled on the private sector insurance plans prevalent at the time, such as Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans and Aetna's plan for Federal employees (the model for Medicare Part B) (Ball, 1995). Hospitals were allowed to nominate an intermediary (a private insurance company) to do the actual work of bill payment and to be the contact point with the hospitals. Payment methods for facilities (hospitals, nursing home, and home health) were based on reasonable costs. Payments for physicians and other suppliers were based on the lower of the area's prevailing or their own customary or actual charge. These payment methods were designed to make sure Medicare beneficiaries would have access to care on the same terms as privately insured patients. When Medicare began, there was concern, which did not turn out to be the case, that demand for services would strain the capacity of the health care system (Gornick, 1996).

Advantages of this approach included: faster implementation—and with 11 months between enactment and implementation that was no small consideration—and political acceptability: The program looked familiar to providers, insurance companies who would administer the new program, and beneficiaries.

Disadvantages of this approach included: payment methods that turned out to be inflationary, prompting considerable legislative activity in subsequent years to control escalating costs; and using private insurance companies to administer the program without allowing for their selection on a competitive basis, which hampered control of the program. Medicare's benefit package was not designed for some of the specific needs of the elderly. For instance, today, nearly one-third have hearing impairments, nearly 20 percent have visual impairments, and nearly one-third have no natural teeth (National Center for Health Statistics, 1999). Yet, hearing aids, eyeglasses, dentures, outpatient prescription drugs, and long term nursing home care were not generally covered by private insurance and so were not covered by Medicare. There was no limit on beneficiary liability, leaving beneficiaries vulnerable to catastrophic expenses. Nor was there provision in the statute for what are now known as preventive services. Only medical care that was necessary for the treatment of an injury or an illness was covered.

Medicare Covers the Disabled in 1972

In 1972, Congress extended Medicare coverage to the disabled on Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and those with end stage renal disease (ESRD). After receiving SSDI, the disabled have a lengthy waiting period, 24 months, before Medicare coverage begins. In 1973, nearly 2 million persons with disabilities and ESRD enrolled in Medicare. People with ESRD needed very expensive dialysis services to stay alive; concerns about their access to such life-saving services motivated the expansion of Medicare coverage. ESRD remains the only disease-specific group eligible for Medicare coverage; although others have been proposed, notably human immunodeficiency virus acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, none has been enacted.

Legislative History

When Medicare was enacted, the original statute comprised 58 pages of text. Over the subsequent 35 years, the statute has grown nearly tenfold to more than 500 pages. Highlights by type of reform include:

Eligibility—Significant expansion of eligibility occurred once, when the disabled and those with ESRD were included in 1972. Public-sector employees were required to pay Medicare payroll taxes in the early 1980s.

Financing—Part A revenue sources were expanded several times in the 1980s and 1990s to delay insolvency of the Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund. Part B premiums were initially set at one-half of the program's cost, but due to program spending growing faster than Social Security benefit increases, premiums were limited to the growth in the Social Security cost of living adjustment and are now set by statute at 25 percent of program spending.

Payment Policy—Most of the major legislative activity in the 1980s and 1990s focused on payment policy, in an effort to control rapidly escalating program spending. Hospitals and other Part A providers were moved from cost-based payment to prospective payment systems (PPSs). Physicians and many other Part B suppliers were moved from charge-based payment to fee schedules. Managed care plans' risk-based payment was modified at the end of the 1990s to reduce the geographic variation in payment amounts and to adjust for the relative health status of their patients.

Benefits—The benefit package was substantially updated in the 1988 Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act (MCCA) to include coverage of outpatient prescription drugs and other changes. It was repealed in 1989 after higher income elderly protested a new tax to partially finance the new benefits. As the importance of preventive benefits became clear, many have been added by the Congress on an incremental basis. Other changes in covered services have included the addition of hospice care, improved coverage for mental health services, and expanded home health benefits.

Chronology of Major Legislative Activity

July 30, 1965—The Medicare program, authorized under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act, was enacted to provide health insurance coverage for the elderly.

July 1, 1966—Medicare benefits began for more than 19 million individuals enrolled in the program.

1972—Medicare eligibility was extended to individuals under age 65 with long-term disabilities after 24 months of Social Security disability benefits and to individuals with ESRD after a 3-month course of dialysis; 2 million such individuals enrolled in the program in 1973.

1980—The home health benefit was broadened; the prior hospitalization requirement was eliminated as was the limit on visits. Medicare supplemental insurance, also called “medigap,” was brought under Federal oversight.

1982—A prospective risk-contracting option for health maintenance organizations (HMOs) was added to facilitate plan participation. Hospice benefits for the terminally ill were covered. Medicare was made secondary payer for aged workers and their spouses. Medicare utilization and quality-control peer review organizations were established. Rate-of-increase limits were placed on inpatient hospital services.

1983—An inpatient hospital PPS, in which a pre-determined rate is paid based on patients' diagnoses, was adopted to replace cost-based payments. (The PPS was subsequently adopted by other payers and other countries.) Federal employees were required to pay the HI payroll tax.

1985—Medicare coverage was made mandatory for newly hired State and local government employees.

1988—The MCCA was the largest expansion of Medicare benefits since the program was enacted. It included an outpatient prescription drug benefit, a cap on patient liability for catastrophic medical expenses, expanded skilled nursing facility (SNF) benefits, and modifications to the cost-sharing and episode-of-illness provisions of Part A Expansions were funded in part by an increase in the Part B premium and a new supplemental income-related premium for Part A beneficiaries. Under Medicaid, States were required to provide assistance with Medicare cost-sharing to low-income Medicare beneficiaries.

1989—The MCCA was repealed after higher-income elderly protested the new tax. A new fee schedule for physician services, called the resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS), was enacted. Physicians were required to submit bills to Medicare on behalf of all Medicare patients. Beneficiary liability for physician bills, above and beyond what Medicare pays, was limited. (The RBRVS was subsequently adopted by other payers.)

1990—Additional Federal standards for Medicare supplemental insurance policies were added. The Part B deductible was increased and prospective payments for inpatient hospital capital expenditures replaced payments based on reasonable costs. Screening mammography was covered and partial hospitalization services in community mental health centers were covered.

1993—The HI payroll tax was applied to all wages, rather than the lower Social Security capped amount; and a new tax on Social Security benefits was imposed above a threshold, with revenues placed in the HI Trust Fund. Under Medicaid, States were required to cover Medicare Part B premiums for specified low-income Medicare beneficiaries.

1996—The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act contained a number of provisions regarding fraud and abuse and established a mandatory appropriation to secure stable funding for program integrity activities and opened program integrity contracts to competitive procurement.

-

1997—The Balanced Budget Act (BBA) included the most extensive legislative changes since the program was enacted. It:

Reduced payment increases to providers, thereby extending solvency of the HI Trust Fund.

Established Medicare+Choice, a new array of managed care and other health plan choices for beneficiaries, with a coordinated annual open enrollment process, a major new beneficiary education campaign, and significant changes in payment rules for health plans.

Expanded coverage of preventive benefits.

Created new home health, SNF, inpatient rehabilitation and outpatient hospital PPSs for Medicare services to improve payment accuracy and to help further restrain the growth of health care spending.

Created new approaches to payment and service delivery through research and demonstrations.

1999—The Balanced Budget Refinement Act increased payments for some providers relative to the payment reductions in the BBA 1997.

Medicare in 2000

During the past 35 years, Medicare has provided health care coverage to more than 93 million elderly and persons with disabilities; more than 39 million are alive today. As a consequence, Medicare has made important contributions to improvements in health status for elderly and disabled beneficiaries.

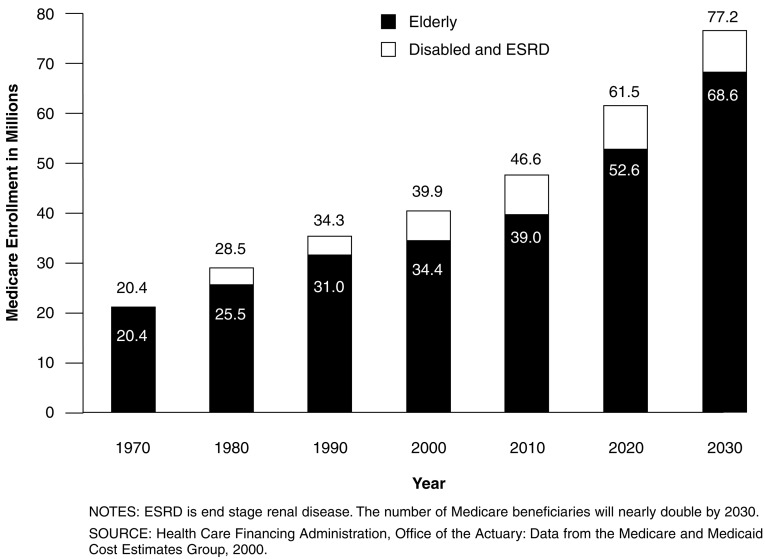

Medicare Beneficiaries

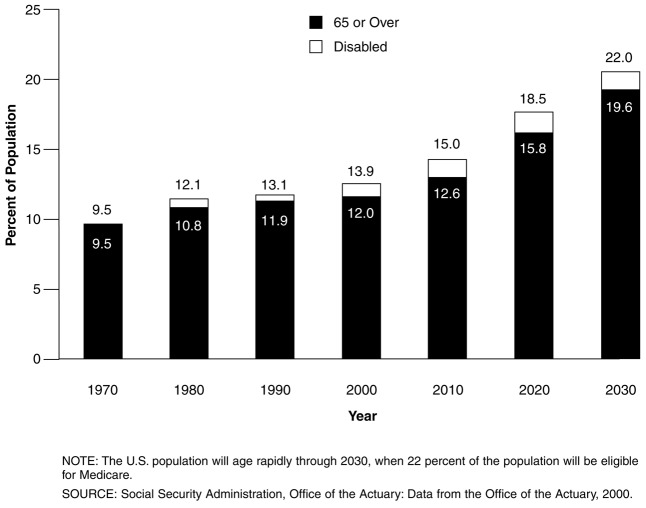

The Medicare program provides health insurance coverage to a diverse and growing segment of the U.S. population (Figure 2). Over its history, the population that is covered under the program has not only expanded in numbers, but has grown more complex in composition and health care needs. More than 19 million elderly entered Medicare in 1966; today, Medicare provides insurance coverage for 34 million older Americans. The number of elderly and disabled enrollees has more than doubled since 1965 to 39 million today. The Medicare population is expected to nearly double again to more than 77 million in 2030 (22 percent of the population) (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Number of Medicare Beneficiaries: 1970-2030.

Figure 3. Aging of the U.S. Population: 1970-2030.

Medicare quickly expanded access to care for the elderly. Hospital discharges averaged 190 per 1,000 elderly in 1964 and 350 per 1,000 by 1973; the proportion of elderly using physician services jumped from 68 to 76 percent from 1963-1970. Currently, more than 94 percent of elderly beneficiaries receive a health care service paid for by Medicare. Similarly, Medicare has improved access for disabled enrollees.

Sex, Marital Status, Race, and Age

Within the elderly population, there are more females than males enrolled in Medicare, primarily because of the longer life expectancy of females. The proportion that is female increases with age: females are more than 70 percent of the population age 85 or over, according to the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. However, the relationship is reversed in the disabled population, where more males are enrolled, reflecting the makeup of the SSDI program population.

Older females are much more likely to be widowed and to live alone than older males due to a number of factors, including females' longer life expectancy, the tendency for females to marry males who are slightly older, and higher remarriage rates for widowed males. Among people age 85 or over, about one-half of the males were still married compared with only 13 percent of the females. (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2000).

The majority of the elderly Medicare population is white (84 percent), black comprise 7 percent, Hispanic 6 percent, and all other races/ethnicities 3 percent. Among disabled enrollees, 69 percent are white, 17 percent are black, and 11 percent are Hispanic.

The living arrangements of the elderly vary by racial and ethnic group. Older white females are much less likely to live with other relatives than older minority females (15 percent compared with 30-40 percent) (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2000). Living alone is a risk factor for nursing home placement, as the elderly grow older.

Over 13 percent, or 4.5 million, of the Medicare elderly population is age 85 or over. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that more than 70,000 Americans are age 100 or over (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1999).

Economic Status

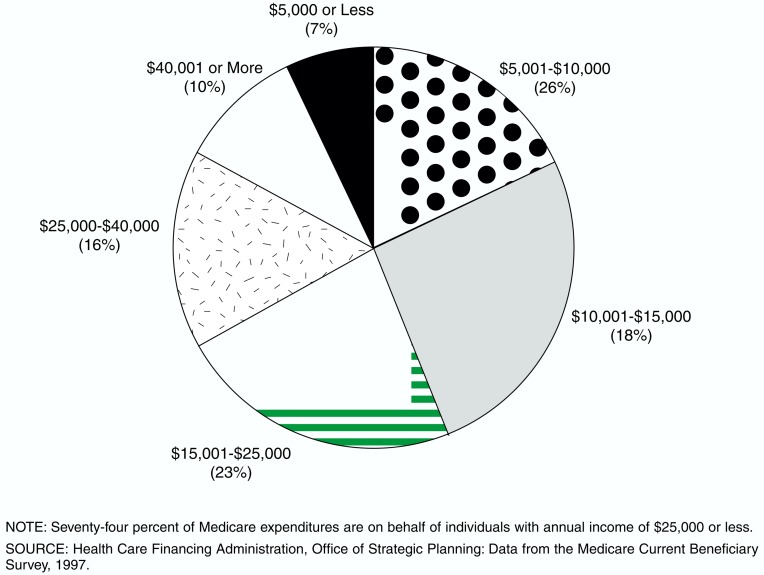

Although the economic status of the elderly as a group has improved over the past 35 years, most elderly individuals have modest incomes. Reflecting the income distribution of beneficiaries, the majority of Medicare spending is for beneficiaries with modest incomes: 33 percent of program spending is on behalf of those with incomes of less than $10,000 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Medicare Spending for Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries, by Income: 1997.

Many elderly Medicare beneficiaries depend upon their Social Security benefits for much of their income. The reliance on Social Security income is greater among single elderly individuals, and increases dramatically as individuals age: Social Security is one-half of the average 85 year old's income. In 1998, Social Security benefits provided about two-fifths of the income of older persons; asset income, pensions, and personal earnings each provided about one-fifth of total income (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2000).

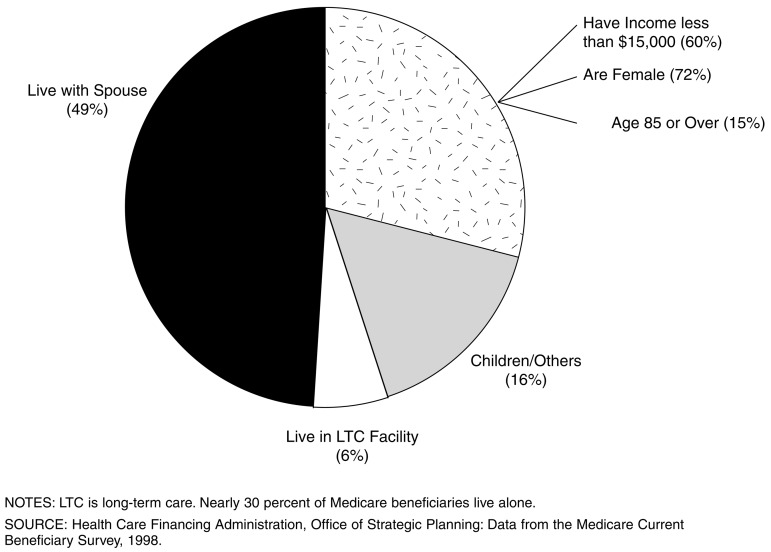

Nearly 30 percent of Medicare beneficiaries live alone, and they are disproportionately female and poor: 72 percent are female, 60 percent have incomes under $15,000. About 15 percent of those who live alone are age 85 or over (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Living Arrangements of Medicare Beneficiaries: 1998.

Health, Chronic Conditions, and Functional Status

Nearly 30 percent of the elderly reported that they were in fair or poor health, compared with 17 percent of those aged 45-64. The percentage reporting fair or poor health was higher for minority groups and increased with age: About 35 percent of those age 85 or over considered themselves in relatively poor health. (National Center for Health Statistics, 1999).

Differences in self-reported health status are reflected in Medicare per capita spending. Not surprisingly, the beneficiaries who reported their health status as poor spent five times as much as the beneficiaries reporting excellent health. Medicare per capita spending also increases as functional status declines.

The incidence of chronic conditions among the elderly, defined as prolonged illnesses that are rarely cured completely, varies significantly by age and racial group. For instance, about 1 in 10 of the elderly has diabetes. However, both the incidence of diabetes and the mortality rates from it are higher for minority groups: Diabetes is the third leading cause of death for elderly American Indians, the fourth leading cause of death among elderly black and Hispanic persons, and the sixth leading cause of death for white persons (National Center for Health Statistics, 1999). The majority of the elderly report arthritis, which has important implications for the ability to care for oneself while living in the community. About 1 in 10 of those who need assistance with the tasks of daily living report arthritis as one of the causes of their need for assistance (National Center for Health Statistics, 1999). Hypertension and respiratory illnesses each affect about one in three of the elderly. About one in four of the elderly have heart disease (National Center for Health Statistics, 1999).

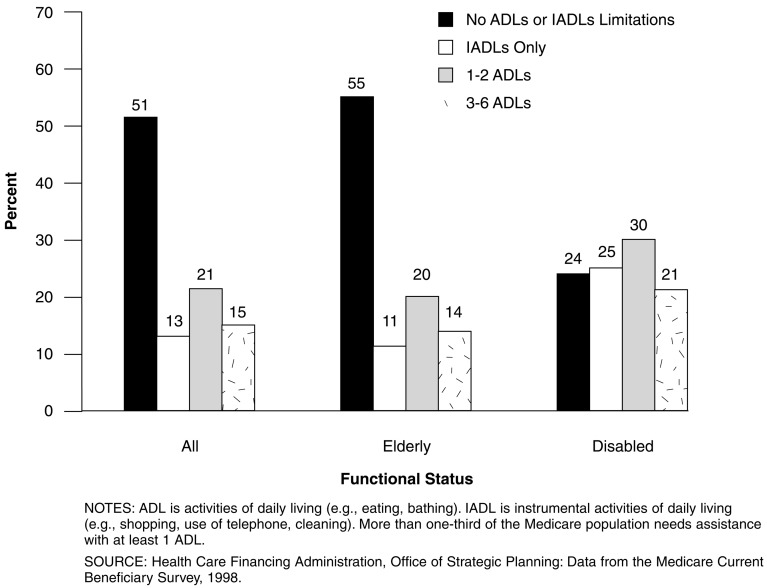

Nearly one in three of the elderly reported limitations with 1 or more activities of daily living (ADLs).1 About 11 percent of the elderly report limitations in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs).2 About 30 percent of the disabled Medicare beneficiaries had difficulties with 1 or more ADLs (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Distribution of Medicare Enrollees, by Functional Status: 1998.

Medicare Spending

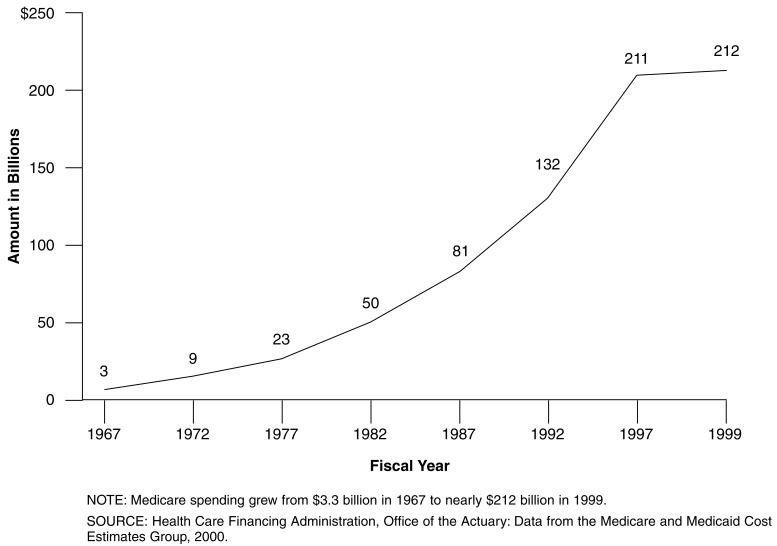

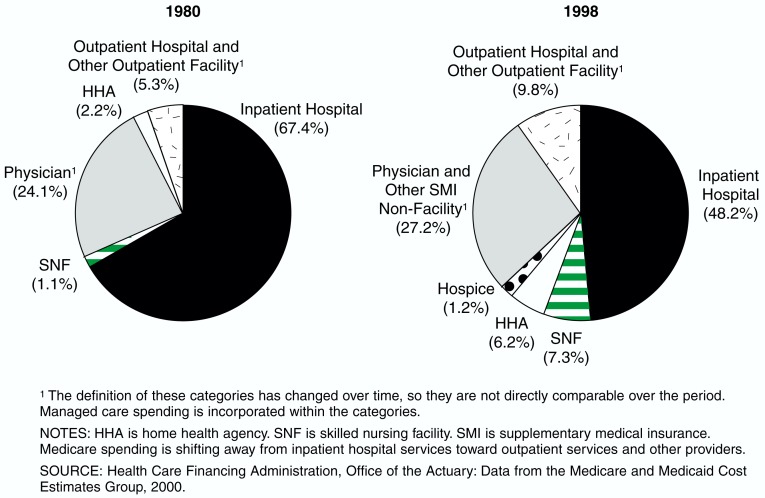

Medicare benefit spending for fiscal year (FY) 1967 was $3.3 billion and for FY 1999 is estimated at nearly $212 billion (Figure 7). The largest shares of spending are for inpatient hospital services (48 percent) and physician services (27 percent) (Figure 8). As medical care has moved to the outpatient setting, these numbers have changed significantly over time. For example, inpatient hospital services accounted for a much higher share of spending, 67 percent, in 1970.

Figure 7. Medicare Spending: Fiscal Years 1967-1999.

Figure 8. Where the Medicare Dollar Went: 1980 and 1998.

Medicare Spending per Beneficiary

In FY 1999 Medicare spent an average of $5,410 per beneficiary. The amount varies on the basis of eligibility and masks considerable variation across individuals. Like other insurance programs, a small percentage of beneficiaries account for a disproportionate share of Medicare spending. More than 75 percent of Medicare's payments for elderly and disabled beneficiaries in 1997 were spent on the 15 percent of enrollees who incurred Medicare payments of $10,000 or more. A similar distribution of payments has existed for much of the program's history.

Historical Spending Growth Comparison

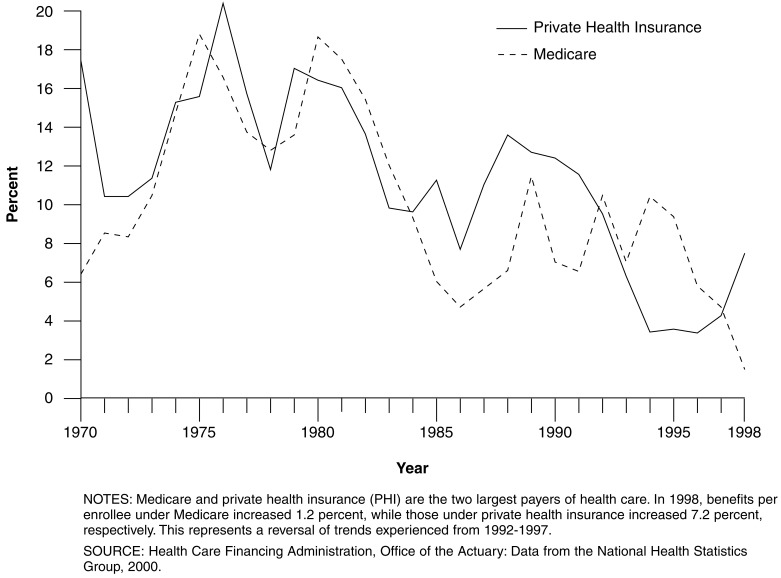

Policymakers have often gauged Medicare's success by measuring program spending against the growth in private health insurance (PHI) spending, the source of insurance for the majority of the working population under age 65. Medicare and PHI are the two largest sources of payment for health care.

Over the 1969-1998 period, Medicare and PHI benefits have grown at similar average annual rates—10.0 and 11.2 percent respectively (Figure 9). During selected periods, however, the growth rates have diverged dramatically. Divergence in growth rates is not unusual between the two major health care payers. Growth rates have often differed, with Medicare alternatively being charged with not “paying its fair share” or “cost-shifting” (1985-1991-1997-1998) or with being “unable to control costs” (1993-1997). Private and public sector forces act to bring spending growth into balance over the long run.

Figure 9. Rate of Growth in Per Enrollee Medicare and Private Health Insurance Spending: 1970-1998.

Supplemental Insurance, Access to Care, and Out-of-Pocket Spending

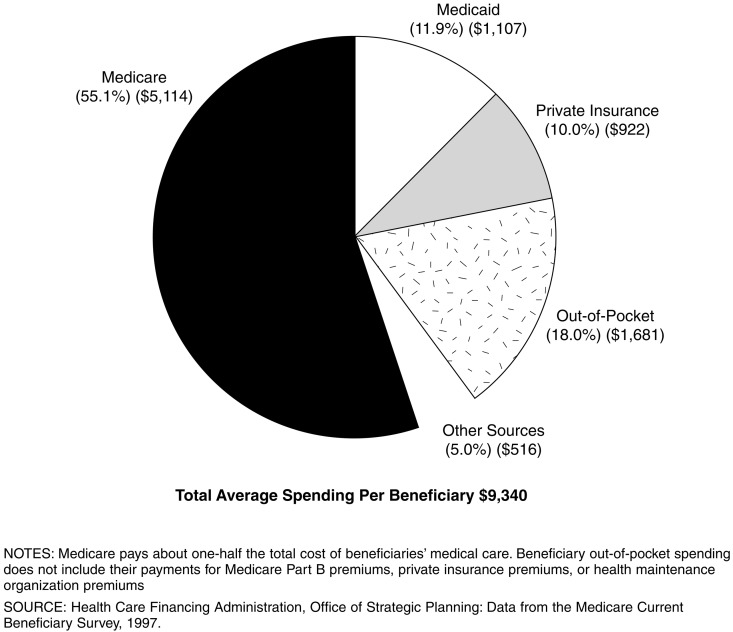

While Medicare is a very important program for the elderly, its benefit package has not kept up with changes in PHI coverage and consequently is less generous than most health plans offered today by large employers. Only about one-half of the personal health care expenditures of the elderly (not including Medicare Part B or private supplemental insurance premiums) are paid by Medicare (Figure 10). Total annual health care spending, from all sources, averaged $9,340 per Medicare beneficiary in 1997. This total masks considerable variation: For instance, total health spending for those who lived in the community averaged $7,181, compared with $43,131 for those who lived in a facility.

Figure 10. Sources of Payment for Medicare Beneficiaries' Use of Medical Services: 1997.

Supplemental Insurance

Medicare has been a life saver with a stroke, two heart attacks and removal of one kidney. There is no way I could've paid for all of that without the help of Medicare and supplemental insurance.

Medicare beneficiary in Richmond, VA. (Health Care Financing Administration, 2000.)

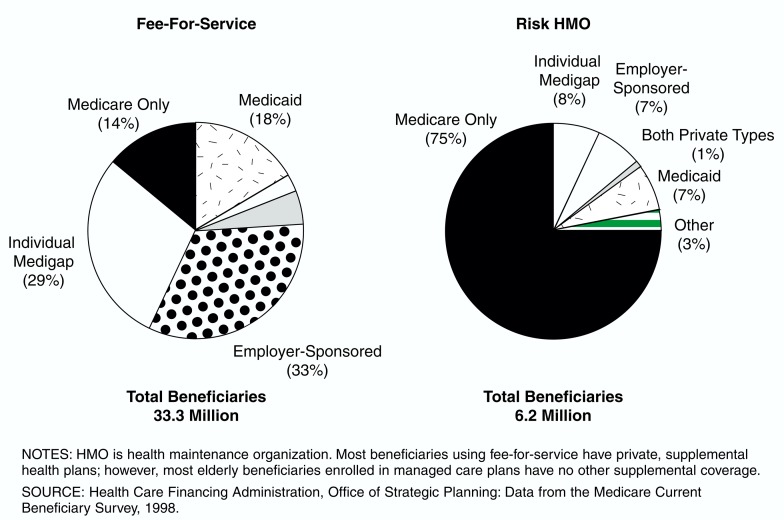

Most beneficiaries have other supplemental insurance (e.g., private medigap policies, retiree coverage, or Medicaid) to supplement their Medicare benefits (Figure 11). About 14 percent of Medicare beneficiaries have no supplemental coverage; groups most likely to rely solely on Medicare are the disabled, minorities, and those with low incomes. Supplemental insurance reduces beneficiaries' out-of-pocket expenditures associated with the use of health care services including Medicare cost sharing.

Figure 11. Type of Supplemental Health Insurance Held, by Medicare Beneficiaries: 1998.

The majority (approximately 67 percent) of Medicare's elderly beneficiaries in fee-for-service (FFS) have private supplemental insurance, either through an employer and/or purchased individually. Most of the elderly enrolled in managed care plans (about 75 percent) do not have any other type of coverage, in part because managed care plans tend to have more generous benefits, making a medigap policy duplicative.

While Federal law guarantees the availability of supplemental insurance policies to elderly beneficiaries (through a limited 6-month open enrollment period upon reaching age 65), only a few States guarantee medigap availability for the Medicare disabled population. This may account in part for the lower levels of medigap coverage for the disabled.

Out-of-Pocket Health Care Spending

I'm thankful for Medicare, but I do have a problem with prescriptions. I have supplemental insurance, but it pays some of it but not that much. That's what really gets me. Now, you go to the drugstore to get medicine—$80, well…

Female Medicare beneficiary in Richmond, VA (Health Care Financing Administration, 2000.)

Medicare and other sources of health insurance have covered a growing share of the Nation's health spending on the elderly. Before Medicare was enacted, the elderly paid 53 percent of the cost of their health care; that share dropped to 29 percent in 1975 and 18 percent in 1997 (Social Security Administration, 1976; Health Care Financing Administration, 2000). The elderly's health costs consumed 24 percent of the average Social Security check shortly before Medicare; by 1975, that share dropped to 17 percent (Social Security Administration, 1976.)

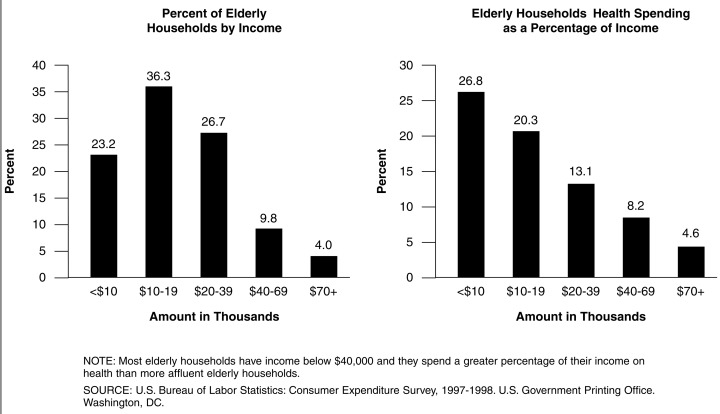

The elderly spend a higher proportion of their income on health than the general population, both because they have higher health care costs (on average four times that of the under age 65 population) and because they have lower incomes. Lower-income elderly spend a higher proportion of their income on health than higher-income elderly: Those with incomes below $10,000 spent one-quarter of their income on health care, those with incomes above $70,000 spent about 5 percent of their income on health care (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Elderly Health Spending as a Percentage of Income: 1998.

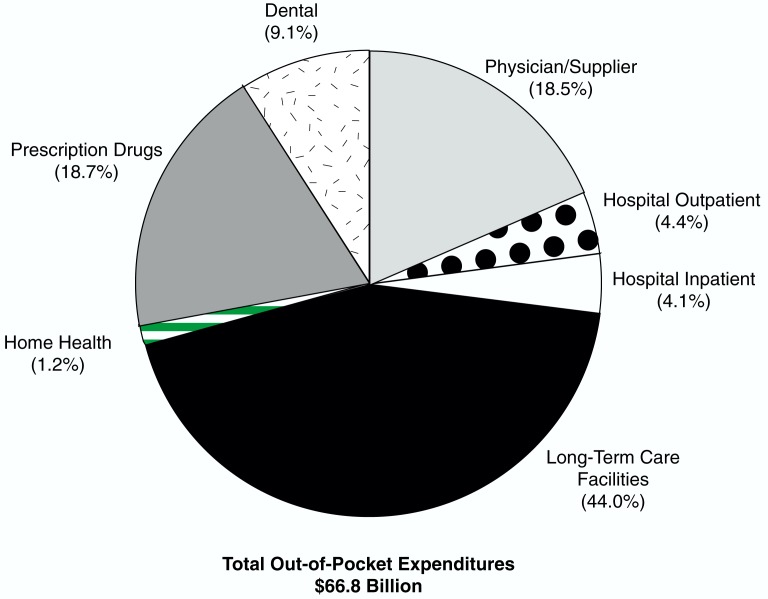

The vast majority of beneficiary out-of-pocket spending on health care is concentrated on three services: long- term facility care accounts for the largest share at 44 percent, with outpatient prescription drugs tied with spending on physician and other supplier services at nearly 19 percent each (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Distribution of Beneficiary Out-of-Pocket1 Expenses: 1997.

1 Beneficiary out-of-pocket does not include their payment for Medicare Part B premiums, private insurance premiums, or health maintenance organization premiums.

NOTE: Institutional long-term care services account for the highest share of beneficiary out-of-pocket payments, followed by outpatient prescription drugs, and physician services.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Strategic Planning: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, 1997.

Vulnerable Populations and Access to Care

If it was not for Medicare, I could not go to the doctor.

Medicare Beneficiary (Health Care Financing Administration, 1999.)

Certain vulnerable populations historically have experienced problems with access to care. The groups include the disabled, Medicare beneficiaries who are eligible for Medicaid (dual eligibles), beneficiaries with low incomes, those age 85 or over, minorities, persons living in rural areas, or in areas designated as health professional shortage areas. A variety of population groups have significantly higher rates of hospitalization for “ambulatory care sensitive” conditions. These are medical conditions that are responsive to good and continuous ambulatory care, like asthma or diabetes. For instance, black beneficiaries are more than three times as likely as white beneficiaries to have a lower limb amputated—often a result of diabetes complications; they are more than two times as likely as white beneficiaries to be treated for wound infections and skin breakdowns, also associated with poor quality care (Gornick, 2000).

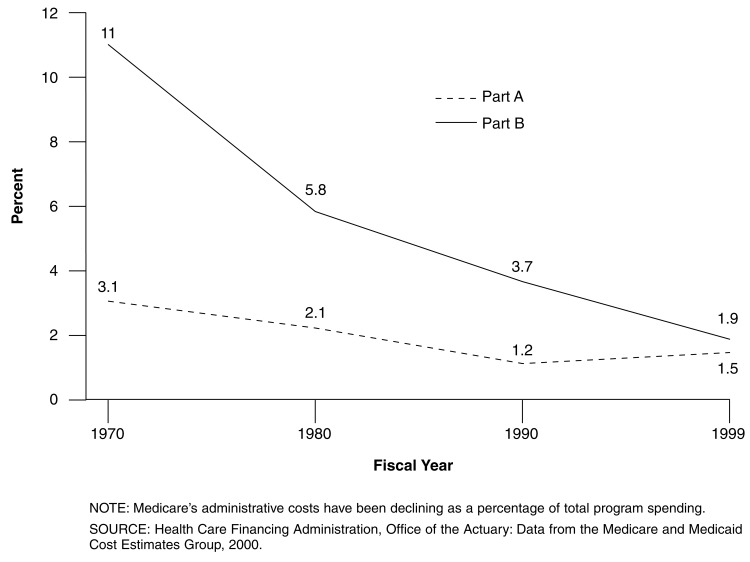

Administrative Costs

Medicare's overall administrative costs are less than 2 percent of total benefit payments (Figure 14). Medicare's administrative costs are significantly lower than private insurers, which the Blue Cross/Blue Shield Association estimates at 12 percent for their plans. Medicare's administrative costs have been declining, reflecting greater efficiency through high levels of electronic claims processing.

Figure 14. Medicare Administrative Expenses as a Percent of Benefit Payments: Fiscal Years 1970-1999.

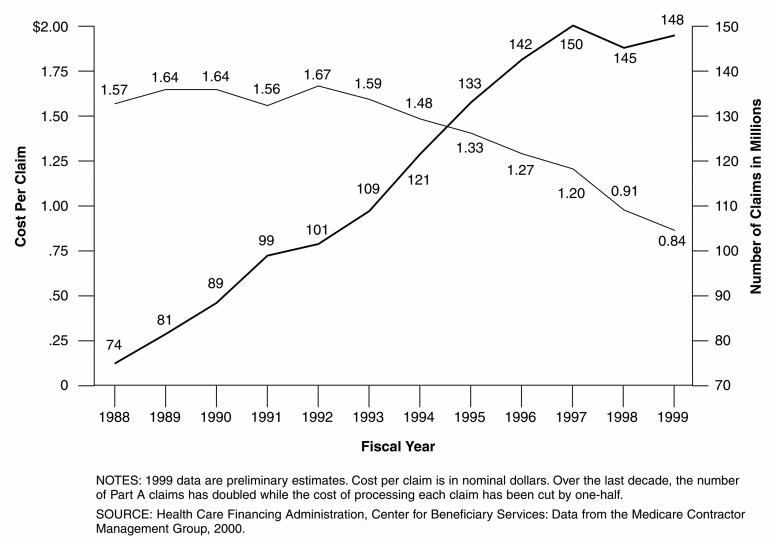

In FY 1999 Medicare processed over 850 million claims at a unit cost per claim of $.84 for Part A fiscal intermediaries and $.77 for Part B carriers (Figure 15). Cost per Part A claim has declined by 50 percent in nominal dollars (if the dollars were adjusted for inflation, the decline would be even larger) over the past 10 years, while the number of claims has doubled.

Figure 15. Medicare Part A Cost Per Claim and Number of Claims: Fiscal Years, 1988-1999.

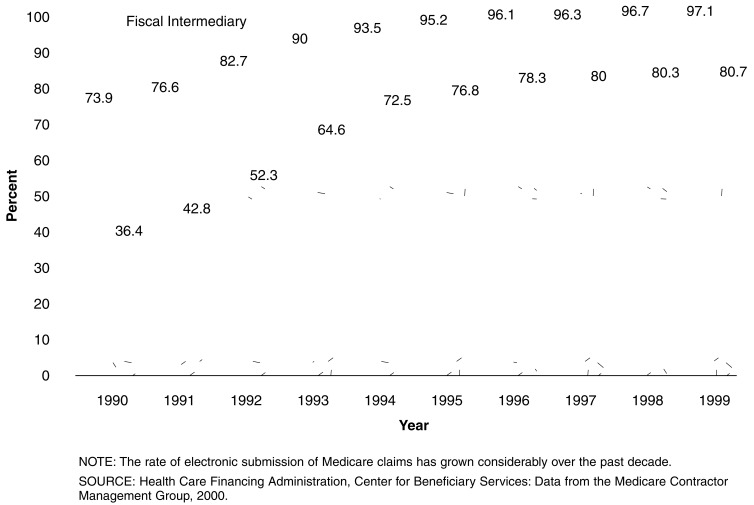

Electronic claims processing is a key reason that the cost per claim has significantly declined (Figure 16). Electronic submission of claims increased from 74 percent of Part A claims in 1990 to 97 percent in 1999, Part B rates rose from 36 percent to 80 percent over the same period.

Figure 16. Percent of Medicare Electronic Claims, by Calendar Years: 1990-1999.

Medicare+Choice

The vast majority of Medicare beneficiaries (83 percent) rely on Medicare's traditional FFS benefits, while 15 percent are enrolled in Medicare+Choice plans. By contrast, in the private sector nearly 80 percent of insured individuals receive their coverage through a managed care plan such as a preferred provider organization (PPO), point-of-service plan, or traditional HMO.

Enrollment in Medicare+Choice

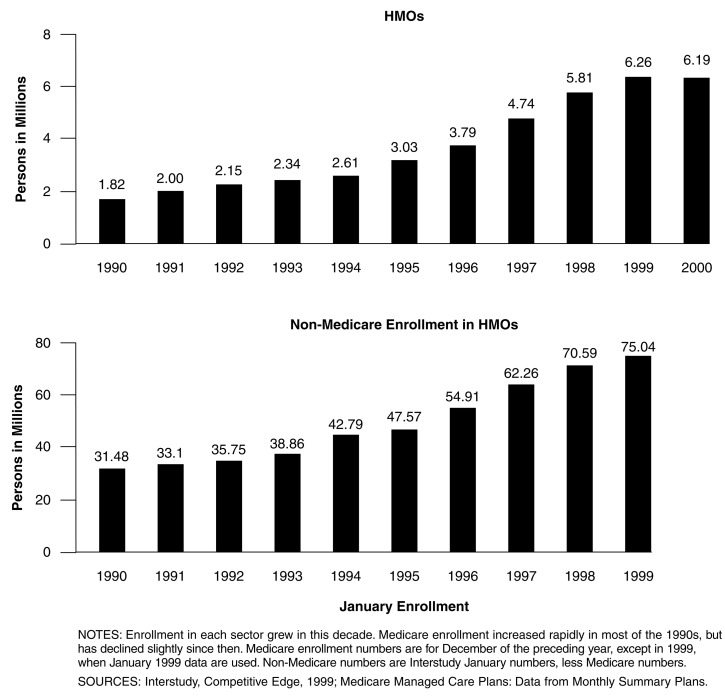

Enrollment in Medicare+Choice, and before that under the risk HMO program, increased every year since the beginning of the risk program in 1985. Increases in enrollment accelerated significantly in the late 1990s, though in recent months, growth has tapered off or even declined. By the end of 1999, 17 percent of Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in risk HMOs (Figure 17). The trend in Medicare HMO enrollment is similar to that of the private sector.

Figure 17. Medicare and Non-Medicare Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) Enrollment Growth: 1990-1999.

Access Under Medicare+Choice

HMO interest in Medicare contracting resulted in dramatic increases in the number of contractors in the mid-1990s. The number of risk contracts more than tripled from 1990-1997. Over the decade of the 1990s, the increase in the availability of plans with benefits more generous than FFS Medicare, coupled with increasing medigap premiums, led more Medicare beneficiaries to enroll in HMOs. Today, about 70 percent of Medicare beneficiaries live in an area with at least one Medicare +Choice plan available. Medicare+Choice enrollment is highly concentrated in certain areas of the country and in certain plans.

Medicare+Choice enrollees are less likely to be eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, and are less likely to be institutionalized. Medicare+Choice enrollees also have better-than-average health and are less likely to be very poor or very wealthy.

Benefits Available to Medicare+Choice Enrollees

Most Medicare+Choice enrollees are provided with extra services not covered by Medicare, such as preventive care beyond what Medicare covers and prescription drugs. Some Medicare+Choice plans charge no premium, and in almost all cases, Medicare+Choice premiums are significantly lower than medigap premiums for similar benefits.

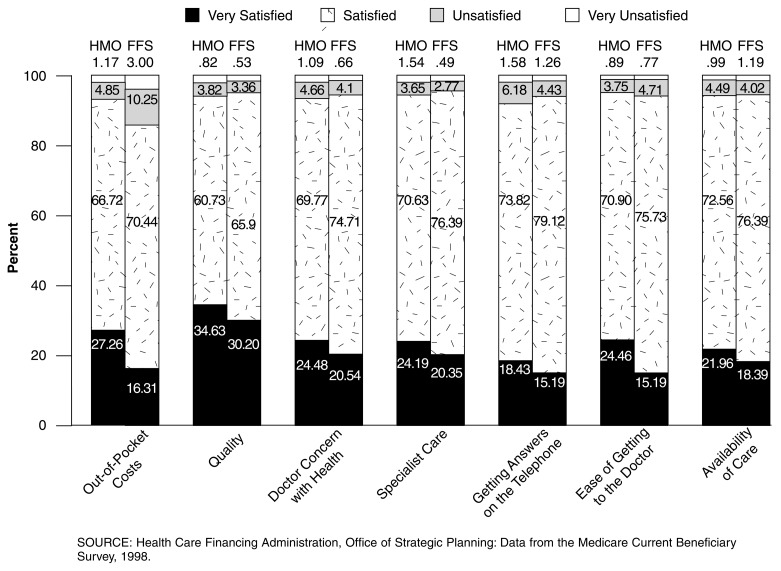

Medicare Beneficiary Satisfaction

Medicare beneficiaries, whether enrolled in FFS or a Medicare+Choice plan, are generally well satisfied with their medical care (Figure 18). Members of Medicare+ Choice plans are somewhat more likely to be satisfied or very satisfied with their out-of-pocket costs than FFS beneficiaries (94 percent versus 87 percent). About 13 percent of FFS beneficiaries were unsatisfied with their out-of-pocket costs, compared with 6 percent of Medicare+Choice enrollees. While Medicare+ Choice members were slightly more unhappy about their ability to get answers to their questions by telephone, they found the ease of getting to a doctor and the availability of care comparable with that experienced by FFS beneficiaries.

Figure 18. Beneficiary Attitudes Towards Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO) and Fee-for-Service (FFS): 1998.

Medicare's Role in the Broader Health System

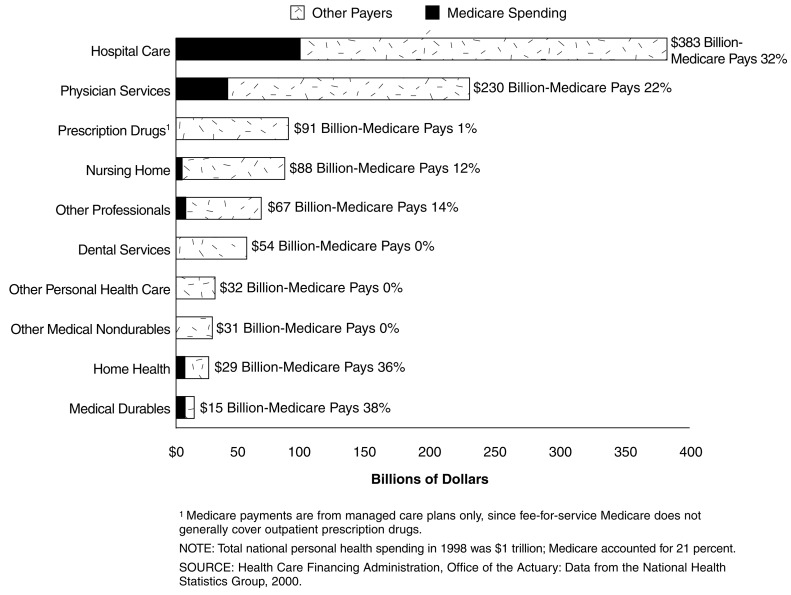

Medicare covers about 14 percent of the population, but because of the extensive health care needs of the elderly and disabled, finances about 21 percent of the Nation's health spending, up from 11 percent in 1970 (Figure 19). Medicare's share varies significantly by type of service and has changed over time as Medicare has become a more important source of financing of health care. For example, in 1970, Medicare paid for 19 percent of all hospital spending; by 1998, Medicare's share rose to 32 percent.

Figure 19. National Personal Health Expenditures, by Type of Service and Percent Medicare Paid: 1998.

Medicare spending finances care for its beneficiaries and also has important ramifications for the health system as a whole. Special payments for rural, inner-city, and teaching hospitals and other safety net providers help to guarantee access to care for other population groups who live in those areas. Medicare's role in quality assurance in hospitals, nursing homes, and other settings helps to assure that all Americans receive high-quality health care services from those providers. Medicare plays an important role in educating the Nation's physicians by financing a portion of the costs of graduate medical education at teaching hospitals, where much of the country's medical research occurs.

Medicare spending is a growing share of the Federal Government's budget: This year, it will account for 12 percent of the budget, compared with 10 percent in 1993 and 4 percent in 1970 (De Lew, 1995).

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the assistance of numerous HCFA staff including: Gerry Adler, Nicole Carey, Frank Eppig, Dave Gibson, Chris Klots, Helen Lazenby, Linda Lebovic, Katharine Levit, Rick McNaney, Solomon Mussey, Andrew Shatto, Sharman Stephens, and Dan Waldo, without whom this article would not have been possible.

Footnotes

The author is with the Office of Strategic Planning, Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA). The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of HCFA.

ADLs, e.g. eating, bathing, toileting.

IADLs, e.g. making telephone call, paying bills, shopping.

Reprint Requests: Nancy De Lew, M.A., M.A.P.A., Health Care Financing Administration, Room 323H, Hubert H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC. 20201. E-mail: ndelew@hcfa.gov

References

- Ball R. What Medicare's Architects Had In Mind. Health Affairs. 1995 Winter;14(4):62–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.4.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Quarterly Almanac: 89th Congress 1st Session 1965. XXI. Washington: Congressional Quarterly News Features; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Corning P. The Evolution of Medicare…from idea to law. Social Security Administration; Baltimore, MD.: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- De Lew N. The First 30 Years of Medicare and Medicaid. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274(3):262–267. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2000: Key Indicators of Well-Being. 2000. Chartbook. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick M, Warren JL, Eggers PW, et al. Twenty Years of Medicare and Medicaid: Covered Populations, Use of Benefits, and Program Expenditures. Health Care Financing Review. 1985 Dec;(1985 Annual Supplement) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornick M, Warren JL, Eggers PW, et al. Thirty Years of Medicare: Impact on the Covered Population. Health Care Financing Review. 1996 Winter;18(2):179–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornick M. Plausible Explanations for Disparities in the Use of Medicare Services and Ways to Effect a Change. Health Care Financing Review. 2000 Summer;21(4):23–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. Annals of Legislation. Medicare I: All Very Hegelian. The New Yorker. 1966a Jul 2;:29–62. [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. Annals of Legislation. Medicare II: More Than a Lot of Statistics. The New Yorker. 1966b Jul 9;:30–77. [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Financing Administration: Office of Strategic Planning. Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Baltimore, MD.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Financing Administration: Center for Beneficiary Services. Baltimore, MD.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Manton KG, Corder L, Stallard E. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 94. Washington, DC.: 1997. Chronic Disability Trends in Elderly United States Populations: 1982-1994; pp. 2593–2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Volume of Physician Visits by Place of Visit and Type of Service. No. 18. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: 1964. (10). Public Health Service. July 1963-June. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Physician Visits. Volume and Interval Since Last Visit. No. 97. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: 1971. (10). Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States,1999. U.S. Government Printing Office; Hyattsville, MD.: 1999. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS)-99-1232. Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Administration. Social Security Bulletin. Baltimore, MD.: Jul, 1976. Ten Years of Medicare: Impact on the Covered Population. Pub. No. (SSA) 76 11700. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RA. Health Care in the Early 1960s. Health Care Financing Review. 1996 Winter;18(2):11–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Current Population Reports. No. 199RV. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: 1999. Centenarians in the United States. (P23). [Google Scholar]