Abstract

Health care quality measurement initiatives often use health plans as the unit of analysis, but plans often contract with provider organizations that are managed independently. There is interest in understanding whether there is substantial variability in quality among such units. We evaluated the extent to which scores on the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS®) survey vary across: health plans, regional service organizations (RSOs) (similar to independent practice associations [IPAs] and physician/hospital organizations [PHOs]), medical groups, and practice sites. There was significant variation among RSOs, groups and sites, with practice sites explaining the greatest share of variation for most measures.

Introduction

Many national efforts to assess health care quality (e.g., Health Plan Employer Data and Information System® and CAHPS®) have focused on health plans as the unit of analysis (Crofton, Lubalin, and Darby, 1999; Meyer et al., 1998; Scanlon et al., 1998; Corrigan, 1996; Epstein, 1996). Large organizations have a substantial influence on provider behavior (Moorehead and Donaldson, 1964; Flood et al., 1982; Burns et al., 1994; Shortell, Gillies, and Anderson, 1994), but several studies have shown that local culture and sub-unit structure are more important determinants of care quality than characteristics of the larger organization (Shortell and LoGerfo, 1981; Flood and Scott, 1978; Flood et al., 1982). Medical groups and doctors' offices hire and fire physicians, shape and reinforce practice culture, and determine the pace and flow of patient visits. Thus, medical groups may be a more meaningful unit of analysis for assessing healthcare quality than health plans (Landon, Wilson, and Cleary, 1998; Palmer et al., 1996; Donabedian, 1980; Health Systems Research, 1999). Medical groups are more likely than health plans to have common norms (Mittman, Tonesk, and Jacobson, 1992) and usually have distinct organizational, administrative, and economic arrangements (Landon, Wilson, and Cleary, 1998; Krawleski et al., 1999, 1998; Freidson, 1975). Indeed, a growing appreciation that medical groups may be a more appropriate unit of accountability has encouraged several group-level performance measurement initiatives, including recent surveys of medical group patients in California and Minnesota. In Minnesota, where direct care is dominated by a few large health plans, the medical group is replacing the health plan as the unit for quality reporting.

Mechanic and colleagues (1980) and Roos (1980) provided early evidence that the structure of medical group practices influences patients' experience of care beyond the influence of payment arrangements. Medical Outcomes Study investigators found that differences in patient evaluations of care among practice type (solo versus multi-specialty group) were larger than differences between payment types (prepaid versus fee-for-service), with practice type having particularly large effects on items relating to access and wait times (Rubin, 1993; Safran et al., 1994). Thus, practice type may be more important than health plan type, although differences in data collection methods across practice types may have biased the results (Seibert et al., 1996).

The larger entities to which medical groups belong, such as PHOs and IPAs, may also influence patients' experience of care through the financial incentives they put into place, their involvement in utilization management and specialty referrals and their role in key practice management decisions such as hiring and training of office staff and implementation of scheduling systems (Krawleski et al., 1999; Welch, 1987, Morrisey et al., 1996).

Zaslavsky and colleagues (2000a) evaluated variation in patients' assessment of care by geographic region, metropolitan statistical area, and health plan. They found that health plans explain a small share of variation for quality measures related to care delivery.

A standardized measure of consumer experiences with care is the CAHPS® survey (Goldstein et al., 2001; Hays et al., 1999). CAHPS® is now the most widely used health care survey in the U.S. It is a requirement for accreditation by the National Committee of Quality Assurance (Schneider et al., 2001) and is administered to probability samples of all managed and fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries each year by CMS (Goldstein et al., 2001). Recently, a version of CAHPS® suitable for administration at the medical group and practice site level was developed (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001). In this article, we evaluate variation in CAHPS® scores among health plans and different levels of physician organizations using this new instrument. The organizational units we evaluated are: health plans, groups of affiliated medical groups and hospitals called RSOs, medical groups, and individual practice sites.

We expected that the relative amount of variation at different levels would vary across measures based on the key functions performed by health care organization at each of these levels. First, we hypothesized that differences among practice sites in patients' assessments of care would be significant for all measures, and that sites would explain the largest proportion of variance in these measures. This hypothesis reflects our expectation that local practice management decisions, practice styles, organizational culture, and other contextual factors would have the most direct effect on patients' experience of care. Second, we hypothesized that differences in performance among medical groups would be significant for all measures, but that group effects would be small relative to site-level effects. A third hypothesis was that quality differences among RSOs would not be significant, with the exception of measures related to access and office staff functions. Small, but significant differences were expected in these measures given the role RSOs play in practice management, utilization management, and specialty care referrals. Lastly, we hypothesized that quality differences among health plans would not be significant, with the exception of measures related to access. We expected significant effects for access due to plan-level differences in benefit design and referral processes.

Methods

Data

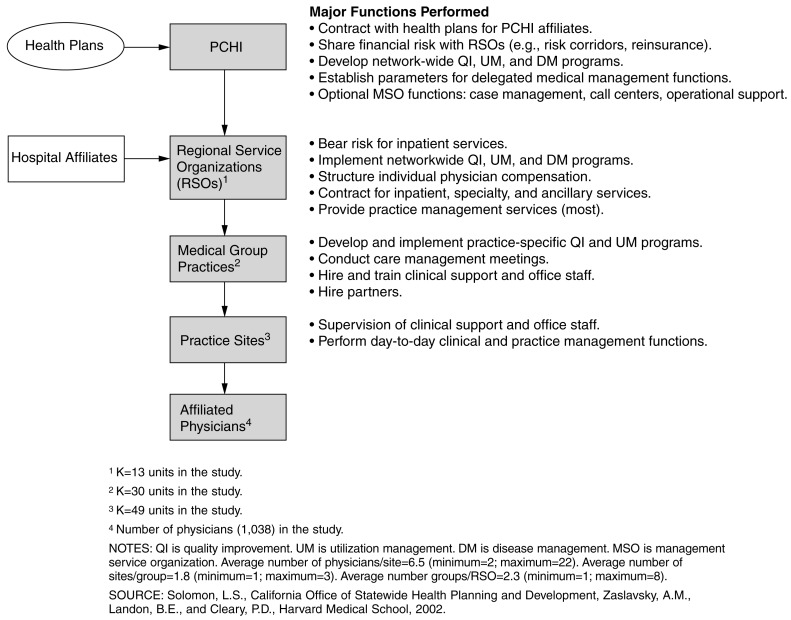

Data for this study come from a survey of patients who received care from Partners Community Healthcare, Inc. (PCHI), a network of 1,038 primary care physicians located in eastern Massachusetts. Within PCHI, 16 RSOs receive a capitated payment for each PCHI patient, and are responsible for providing the full range of covered inpatient and outpatient services. (Three RSOs did not participate in the study: one declined to participate, another had insufficient volume to be included, and a third was excluded because it did not have adequate information for sampling.) Approximately one-half of the 13 RSOs participating in this study are PHOs, with the remaining RSOs consisting of either freestanding medical groups or IPAs that partner with a local hospital for inpatient services. While these entities are somewhat unique to PCHI, they perform many of the same functions as PHOs or IPAs in other systems of care. Each RSO includes one or more medical groups, with physicians located in one or more primary care practice sites, such as a doctor's office or clinic. Thus, PCHI has a hierarchical organizational structure in which physicians are nested within practice sites, sites are nested within medical groups, and groups are nested within RSOs (Figure 1). During the study period, PCHI contracted with three managed care plans. Most PCHI groups contract with all three plans.

Figure 1. Partners Community Healthcare Inc.'s (PCHI) Organizational Structure.

A subset of 30 PCHI medical groups was selected for participation in this study by RSO medical directors. These groups, which represent approximately 40 percent of all PCHI providers, were selected either because they had previously collected similar survey data that could be used to estimate trends, or because the medical directors thought they would be most able to use study data for quality improvement activities.

These 30 groups provide care in 49 distinct practice sites (i.e., doctor's office and clinics) included in our study. In order to designate sub-RSO units as groups or practice sites, PCHI managers were interviewed about the structure of these practices. Practices were identified as a medical group or sites affiliated with a medical group on the basis of several criteria including: (1) the group's history, including the duration of organizational affiliations and current legal structure; (2) the centralization of practice administration and staffing decisions; (3) the centralization of or uniform standards for medical records and information systems; (4) the presence or absence of centralized medical management; and (5) the locus of financial risk and decisionmaking over physician compensation. These criteria operationalize a frequently used definition of medical group practice (American Medical Association, 1999).

We assigned each patient to a practice site based on the location of each patient's primary care physician, using addresses from PCHI's physician credentialing database, which reflects locations where patient care is delivered. In the case of three groups, our data indicated that physicians practiced in multiple practice sites. For one of these groups, we assigned patients to a practice site based on where the majority of visits occurred. This information was not available for the other two groups, which we excluded from the analyses presented here.

Patient Sample

A probability sample of patients covered by the three PCHI managed care contracts was drawn in each of 28 groups participating in the study. For two groups, all-payer samples were drawn, as these groups did not have active health maintenance organization contracts in place during the sampling period. Sampled patients had to be age 18 or over and have had at least one primary care visit between March and December, 1999. A primary care visit was defined as any visit with the patient's primary care physician or a covering physician in which one or more billing codes for evaluation and management was generated. (Current Procedural Terminology [American Medical Association, 1999] codes for evaluation and management services used as sampling criteria included: 99201-99205 [illness office visit for a new patient]; 99212-99215 [illness office visit for an established patient]; 99385-99387 [preventive care delivered to a new patient], and; 99391-99397 [preventive care delivered to an established patient].)

Patients were selected using a multi-stage stratified sampling design. Patients were sampled from each of the 13 RSOs that participated in the study. The number of sampled groups in each RSO was based on the RSO's share of PCHI's total enrollment, with larger RSOs sampling patients from a larger number of groups. For selected groups, all known sites of care with more than two physicians were included in the sampling plan. Patients from smaller sites were oversampled so that the precision of site-level estimates would be comparable.

Two hundred patients were sampled at each single-site group, and approximately 285 patients were sampled per site at each multi-site group. In three sites, we sampled all eligible patients before reaching the target sample size. Within each site, the sample was stratified by plan and allocated in proportion to each plan's share of total enrollment in the RSO to which the site is affiliated. This sample was supplemented by a 100-percent sample of patients participating in PCHI's disease management programs (n= 598).

Measures

The questionnaire used in this study is a version of the CAHPS® instrument modified for use in medical group practices. The group-level CAHPS® (G-CAHPS®) instrument contains 100 questions; 50 ask patients for reports about their experiences with their medical group and 5 ask for global evaluations of care (rating of specialist, personal doctor or nurse, all care, the medical group, and recommendation of the practice). Other questions ask about patient demographics, health status and use of services, or are used to determine the applicability of other items (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001).

G-CAHPS® items were assigned to composites based on factor analyses and reporting considerations (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001). These composites assess: (1) getting needed and timely care, (2) communication between doctors and patients, (3) courtesy and respect shown by the office staff, (4) coordination between primary care physicians and specialists, (5) preventive health advice, (6) patient involvement in care, (7) patients' trust in their physician, (8) caregivers' knowledge of the patient, and (9) preventive treatment. (For additional information on the summary questions used in our analysis and the composites to which each item was assigned, contact the authors.)

Analysis

For each item, we calculated the mean, the standard deviation, standard error, and the item response rate among returned surveys. For composites with different number of missing items (getting needed care and getting care quickly), the variance of each site's mean score was estimated using the Taylor linearization method for the sum of ratios (Sarndal, Swensson, and Wretman, 1994; Zaslavsky et al., 2000b). Each question was weighted equally when calculating composite scores.

We calculated F-statistics to assess differences among health plans, RSOs, groups, and sites. First, we estimated F-statistics for simple comparisons among different organizational subunits with a oneway random effects ANOVA (analysis of variance) model. Next, we estimated F-statistics for each level of analysis using a nested model specifying practice sites as the lowest level error term, and then adding higher-level effects as random main effects. Group-level F-statistics were estimated in a model containing both groups and sites; and F-statistics for RSOs were estimated in a model containing RSOs, groups, and sites. These models control for the variability among higher-level units that is attributable to lower-level units. Consistent with CAHPS® reporting standards (Zaslavsky, 2001), these statistics were adjusted for patient-level factors demonstrated to influence CAHPS® scores including age, education, and self-reported health status.

We estimated variance components using restricted maximum likelihood estimation (REML) to assess the share of total variation in composite scores and global ratings beyond patient-level variation attributable to differences among plans, RSO, groups, and sites. (This fraction is referred to as “explainable variation” in the remainder of this article.) We used REML because this technique provides more efficient and less biased estimates of the variance components than other algorithms for data with small and unequal numbers of groups and of respondents per group (Snijders and Bosker, 1999). The variance components model can be expressed as

where yprgs = mean adjusted score for patients from plan p seen at site s of group g of RSO r, αp∼N(0,τ2p) is the plan effect with variance τ2p. Similarly βr∼N(0,τ2R),γrg ∼N(0,τ2G),δrgs∼N(0,τ2S) are RSO, group, and site effects, and εprgs∼N(0,Vprgs) represents sampling error. The variance components of interest are τ2P,τ2R, τ2G and τ2S.

We calculated group- and site-level reliability coefficients with a one-way random effects ANOVA model, using the formula: (MSbetween − MSwithin) / MSbetween, where MS represents the mean square in the ANOVA. This reliability index represents the ratio of the variance of interest over the sum of the variance of interest plus measurement error (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979; Snijders and Bosker, 1999). To assess the proportion of total variance in G-CAHPS® scores explained by organization-level effects, we calculated intraclass correlation coefficients using the ratio of the sum of variance components for site, group, RSO, and plan effects to the sum of those components and the residual variance component (representing patient-level variation not attributable to any organizational level).

Results

Respondents

The overall response rate was 45 percent (n=5,870). After eliminating 286 respondents who could not be assigned to a specific site of care, there were 5,584 respondents. Response rates by medical group ranged from 22 to 62 percent. We were able to compare the characteristics of responders and non-responders for a limited number of measures based on administrative data that were available for all patients in the sample frame (Table 1). Respondents were significantly older and more likely to be female than non-respondents. Respondents also had significantly more primary care visits at their medical group over the 9-month window for encounters triggering eligibility for the sample, although this difference was small (2.5 versus 2.2 percent). Respondents also had small, but significantly higher numbers of total visits (2.7 versus 3.1 percent). These results are similar to findings from a non-response analysis of data from other G-CAHPS® field test sites (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Characteristics of G-CAHPS® Survey Respondents and Non-Respondents.

| Characteristic | Survey Respondents | Non-Respondents | t-statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 5,864 | 7,496 | — |

| Percent | |||

| Female | 62.8 | 56.8 | **7.05 |

| Age | |||

| 18-29 Years | 9.9 | 20.0 | **16.12 |

| 30-39 Years | 15.1 | 25.8 | **15.19 |

| 40-49 Years | 17.0 | 20.8 | **5.57 |

| 50-64 Years | 25.7 | 17.9 | **-10.90 |

| 65 Years or Over | 32.3 | 15.5 | **-23.51 |

| Primary Care Visits1 | 2.5 | 2.2 | **-8.18 |

| Total Visits1 | 3.1 | 2.7 | **-6.92 |

| Some College Education | 65.2 | — | — |

| Race | |||

| White | 92.7 | — | — |

| African-American | 1.6 | — | — |

| Hispanic | 2.0 | — | — |

| Other | 5.2 | — | — |

| Health Status | |||

| Excellent | 14.6 | — | — |

| Very good | 35.4 | — | — |

| Good | 35.4 | — | — |

| Fair | 11.1 | — | — |

| Poor | 1.7 | — | — |

Significant t-value at p<0.001.

Time period corresponds to a 9-month window in which a patient must have had a visit to be eligible for the survey; primary care visit defined as visit for which an evaluation and management billing code was generated.

SOURCE: Solomon, L.S., California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, Zaslavsky, A.M., Landon, B.E., and Cleary, P.D., Harvard Medical School, 2002.

Most respondents (92.7 percent) were white. More than 65 percent reported having at least some college education, and 50 percent rated their general health as excellent or very good. (Data on these characteristics were not available for non-respondents.)

Mean Scores and Item Non-Response

Consistent with findings from other CAHPS® studies (Zaslavsky et al., 2000; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001), mean scores for items were skewed towards the high end of response scales. Item-level non-response averaged 67 percent across all items in the instrument, mainly due to skip patterns for items not applicable to all respondents.

Between-Unit Variability

Our one-way analysis indicates significant between-site variation in all G-CAHPS® measures with the exception of the patient involvement in care composite, the chronic care composite, and the specialist rating (Table 2). F-statistics for site effects range from a high of 5.21 (p < 0.01) for the continuity composite to a low of 1.16 for the chronic care composite (p > 0.05).

Table 2. F-Values1 for Composites, Single Items, and Global Ratings in G-CAHPS® Data.

| Variable | Health Plan | Regional Service Organization | Medical Group | Individual Practice Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composites | ||||

| Getting Needed Care | 0.87 | *3.45 | **2.85 | **2.33 |

| Getting Quick Care | 1.73 | **4.78 | **5.38 | **4.99 |

| Communication | 1.43 | **2.84 | **2.80 | **2.90 |

| Office Staff Courtesy | 1.90 | **4.04 | **3.20 | **3.93 |

| Involvement in Care | 0.26 | 1.13 | 1.34 | 1.30 |

| Trust in Physician | 1.04 | *1.99 | **2.65 | **1.57 |

| Whole Person Knowledge | **2.33 | **3.28 | **3.49 | **3.55 |

| Primary Care Physician/Specialist Coordination | 1.55 | **2.96 | **2.62 | **2.41 |

| Continuity of Care | 1.15 | **5.54 | **4.41 | **5.21 |

| Advice | **5.21 | **7.29 | **4.89 | **4.43 |

| Chronic Care | 0.86 | 0.60 | 1.18 | 1.16 |

| Single Items | ||||

| Flu Shot Over 65 Years | 1.47 | 0.72 | *1.50 | **1.65 |

| Recommend Office | 1.62 | **2.83 | **4.01 | **3.76 |

| Global Ratings | ||||

| Specialists | *2.03 | 0.64 | 1.44 | 1.23 |

| Personal Doctor or Nurse | 0.72 | **3.73 | **3.70 | **3.54 |

| All Care | 0.59 | **2.26 | **3.07 | **2.95 |

| Office | 1.67 | **3.22 | **4.01 | **4.11 |

Significance at p<0.05.

Significance at p<0.01.

F-statistics estimated with a 1-way random effects ANOVA (analysis of variance) with case-mix adjustment for age, education, and self-reported health status.

NOTES: N = 5,584. G-CAHPS® is a modified version of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study used in medical group practices survey.

SOURCE: Solomon, L.S., California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, Zaslavsky, A.M., Landon, B.E., and Cleary, P.D., Harvard Medical School, 2002.

There also were a large number of significant group- and RSO-level effects. At the group level, F-statistics ranged from a high of 5.38 (p < 0.01) for the timeliness of care composite to a low of 1.18 (p > 0.05) for the chronic care composite. RSO-level F-statistics range from a high of 7.29 (p < 0.01) for the advice composite to a low of 0.60 (p > 0.05) for the chronic care composite.

There is little between-plan variation in G-CAHPS® measures. F-statistics were significant at the health plan level only for advice (F=5.21, p < 0.01) and whole person knowledge (F=2.33, p < 0.01) composites. Among the global rating items, between-plan variation was only significant for the specialist rating (F=2.03, p < 0.01).

Our nested analysis (Table 3) indicates that group and RSO effects do not explain a significant amount of variability above and beyond the portion explained by sites. F-statistics for group-level effects range from 0.78 for continuity to 1.92 for getting needed care. F-statistics for RSO-level effects range from 0.49 for the chronic care composite to 2.12 for the office staff composite. Site-level F-statistics remain the same as those presented in Table 2. Similarly, plan-level estimates are identical to those presented in Table 2, as plans are a cross-network level of analysis.

Table 3. F-Values1 and Variance2 Components for Composites, Single Items, and Global Ratings: Nested Analysis.

| Variable | F-Value | Percent of Variance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Health Plan | Regional Service Organization | Medical Group | Practice Site | Health Plan | Regional Service Organization | Medical Group | Individual Practice Site | |

| Composites | ||||||||

| Getting Needed Care | 0.87 | 1.39 | 1.92 | **2.33 | 0 | 45.5 | 34 | 20.5 |

| Getting Quick Care | 1.73 | 0.62 | 1.27 | **4.99 | 0 | 0 | 31.9 | 68.1 |

| Communication | 1.43 | 1.19 | 0.92 | **2.90 | 0 | 4.6 | 18.2 | 77.2 |

| Office Staff Courtesy | 1.90 | 2.12 | 0.80 | **3.93 | 13.6 | 21.4 | 0 | 65.0 |

| Involvement in Care | 0.26 | 0.81 | 1.06 | 1.30 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Trust in Physician | 1.04 | 0.63 | 1.03 | **1.57 | 0 | 5.7 | 30.9 | 63.5 |

| Whole Person Knowledge | **2.33 | 0.73 | 0.95 | **3.55 | 0 | 1.8 | 0 | 98.2 |

| Primary Care Physician/Specialist Coordination | 1.55 | 1.54 | 1.10 | **2.41 | 0 | 20.8 | 0 | 79.2 |

| Continuity of Care | 1.15 | 1.63 | 0.78 | **5.21 | 0 | 7.7 | 0 | 92.3 |

| Advice | **5.21 | 2.03 | 1.44 | **4.42 | 16.9 | 22.9 | 0 | 60.10 |

| Chronic Care | 0.86 | 0.49 | 0.96 | 1.16 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Single Items | ||||||||

| Flu Shot Over 65 Years | 0.20 | 0.87 | 0.91 | **1.65 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Recommend Office | 1.62 | 0.65 | 1.10 | **3.76 | 4.3 | 0 | 19.6 | 76.10 |

| Global Ratings | ||||||||

| Specialist | *2.03 | 0.43 | 1.46 | 1.23 | 27.6 | 0 | 72.4 | 0 |

| Personal Doctor or Nurse | 0.72 | 0.85 | 1.15 | **3.54 | 0 | 0 | 30.2 | 69.8 |

| All Care | 0.59 | 0.39 | 1.13 | **2.95 | 0 | 0 | 15.2 | 84.8 |

| Office | 1.67 | 0.60 | 1.02 | **4.11 | 18.4 | 1.5 | 15.2 | 65.0 |

F-value is significant at p<0.05.

F-value is significant at p<0.01.

Site and plan effects estimated with a 1-way random effects model; group and regional service organization effects estimated with a random effects model including site (for group effect) and site and group (for regional service organization effect).

Estimates with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. Scores are adjusted for age, education, and self-reported health status.

NOTES: N = 5,584. NA is not available.

SOURCE: Solomon, L.S., California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, Zaslavsky, A.M., Landon, B.E., and Cleary, P.D., Harvard Medical School, 2002.

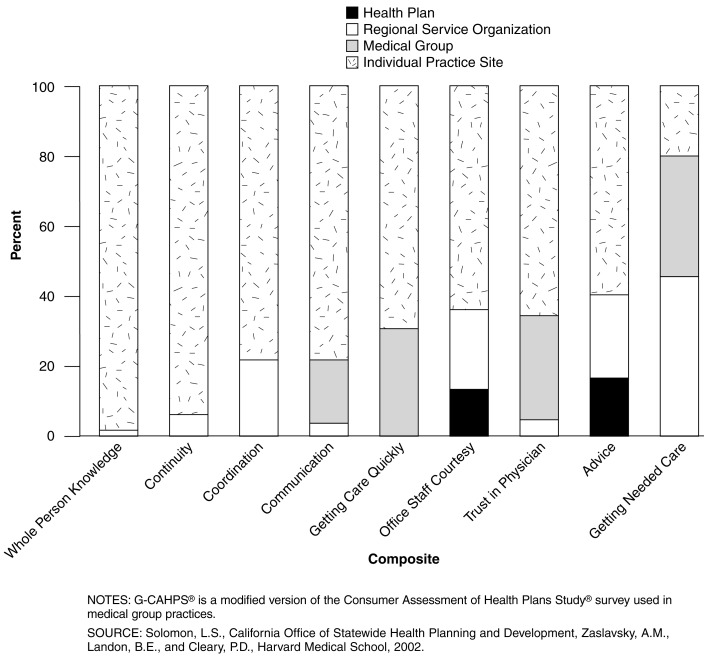

Variance Components

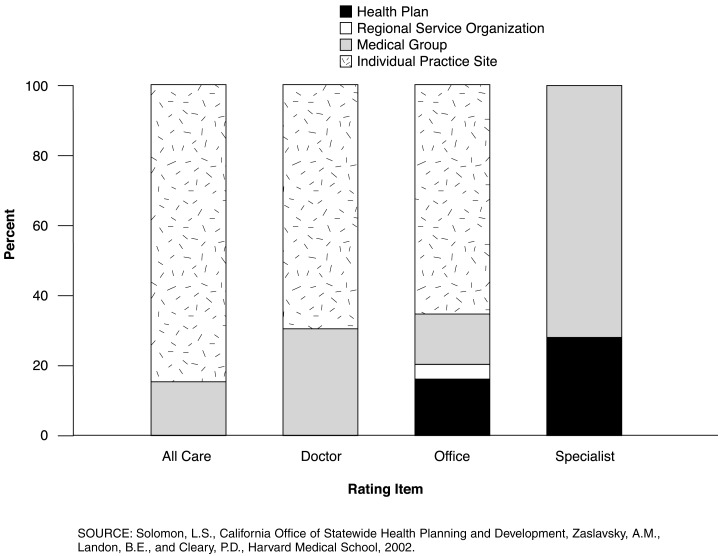

Practice sites account for more than one-half of the variance above the individual level for all but one of the G-CAHPS® composites (Table 3; Figure 2). The one exception is the getting needed care composite for which RSOs and groups both explained a larger share of variability than site. For the remaining composites, the share of explainable variance attributable to individual practice sites ranges from a low of 60 percent for advice to a high of 98.2 percent for whole person knowledge. Individual practice sites also explain the greatest share of variability in rating items, with the exception of the specialist rating where sites make no detectable contribution. (Figure 3). For the remaining rating items, the proportion of variance attributable to sites ranges from a low of 65 percent for the office rating to a high of 84.8 percent for the rating of all care.

Figure 2. Variance Components, by Organizational Level for G-CAHPS® Composites.

Figure 3. Variance Components, by Organizational Level for Rating Items.

Groups and RSOs explain most of the remaining variance for the majority of composites, although these effects are not statistically significant. The share of explainable variance attributable to groups ranges from a high of 30.9 percent for trust to a low of 18.2 percent for communication, with groups making no detectable contribution to variance for office staff, coordination, continuity, advice, and whole person knowledge composites. For ratings of personal doctor or nurse and all care, groups explained the second largest share of variation after sites (30.2 and 15.2 percent of explained variance, respectively). Groups explain about the same amount of variation in office ratings as plans (15.2 versus 18.4 percent). Groups are the largest source of variation in specialist ratings (72.4 percent).

The percent of explainable variance due to RSOs ranges from a low of 1.8 percent for whole person knowledge to a high of 45.5 percent for getting needed care, representing the single largest component for the latter composite. There was no detectable variation between RSOs for the getting care quickly composite. Similarly, RSOs make a relatively small contribution to variability in global ratings. RSOs contribute 1.5 percent to explainable variation in office ratings and no observable contribution to variation in other rating items.

Health plans make a modest contribution to variation in G-CAHPS® measures compared with provider organizations. Plans contribute 13.6 percent to explainable variation in the office staff composite and 16.9 percent to the advice composite. Variance components are estimated to be zero for the remaining composites. For two of the four rating items, however, plans are the second largest contributor to explainable variance. Plans explain 27.6 percent of variance in the specialist rating, and 18.4 percent of explainable variance in the office rating.

Inter-unit Reliabilities and Intraclass Correlations

Four of the 11 composites achieved group-level reliability values in excess of 0.70 given the number of responses yielded in this study, with five additional composites achieving reliabilities between 0.60 and 0.70 (Table 4). Composites with group-level reliability values exceeding 0.70 include access to quick care (0.81), advice (0.80), inter-visit continuity (0.77) and whole person knowledge (0.70). For global rating items, both ratings of personal doctor or nurse (0.73) and rating of the doctor's office (0.75) exceeded reliability levels of 0.70. Results are similar for site-level reliabilities with an additional measure, the office staff composite, achieving a site-level reliability in excess of 0.70. Intraclass correlation coefficients were exceedingly small, ranging from 0.0 for chronic care composite to 0.06 for the advice composite.

Table 4. F-Values, Inter-Unit Reliabilities and Intraclass Correlations for Composites, and Single Item, Global Ratings.

| Variable | Medical Group-Level Statistics | Individual Practice Site-Level Statistics | Intraclass Correlation2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Average Number of Respondents | Reliability1 | Average Number of Respondents | Reliability1 | ||

| Composites | |||||

| Getting Needed Care | 176 | 0.65 | 108 | 0.57 | 0.017 |

| Getting Quick Care | 179 | 0.81 | 109 | 0.80 | 0.036 |

| Communication | 164 | 0.64 | 100 | 0.66 | 0.018 |

| Office Staff Courtesy | 163 | 0.69 | 100 | 0.75 | 0.046 |

| Involvement in Care | 167 | 0.26 | 102 | 0.23 | 0.003 |

| Trust in Physician | 154 | 0.62 | 95 | 0.36 | 0.016 |

| Whole Person Knowledge | 154 | 0.71 | 95 | 0.72 | 0.026 |

| Primary Care Physician/Specialist Coordination | 113 | 0.62 | 69 | 0.59 | 0.021 |

| Continuity of Care | 136 | 0.77 | 83 | 0.81 | 0.061 |

| Advice | 178 | 0.80 | 109 | 0.77 | 0.041 |

| Chronic Care | 94 | 0.15 | 57 | 0.14 | 0 |

| Single Item | |||||

| Flu Shot (Over 65 Years) | 178 | 0.33 | 109 | 0.39 | 0.001 |

| Global Ratings | |||||

| Specialists | 111 | 0.31 | 68 | 0.19 | 0.008 |

| Personal Doctor or Nurse | 174 | 0.73 | 107 | 0.72 | 0.025 |

| All Care | 175 | 0.67 | 107 | 0.66 | 0.020 |

| Office | 175 | 0.75 | 108 | 0.76 | 0.041 |

Inter-unit reliability = (F-1)/F; F ratios estimated with a 1-way random effects ANOVA (analysis of variance) with case-mix adjustment for age, education, and self-reported health status.

ICC = (variance component site + variance component group + variance component RSO + variance component plan) / (variance component site + variance component group + variance component RSO + variance component plan + variance component residual) estimated with REML specifying random nested effects.

NOTES: ICC is intraclass correlation coefficient. RSO is regional service organization. REML is restricted maximum likelihood estimation.

SOURCE: Solomon, L.S., California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, Zaslavsky, A.M., Landon, B.E., and Cleary, P.D., Harvard Medical School, 2002.

Discussion

This study provides strong evidence that patient-reported quality is strongly influenced by site of care. While group and RSO effects are significant when analyzed by themselves in single-level models, these effects are not significant in a nested analysis that controls for variability attributable to organizational subunits. This highlights the importance of multi-level analysis when assessing the performance of complex health care organizations.

Practice sites account for at least 60 percent of explainable variation for eight out of the nine composites for which there are significant between-site differences, likely reflecting the importance of site-level practice management strategies and the local environment over patients' experience of care. Any variation due to the characteristics of individual providers also is incorporated into site-level variation in this analysis. Sites also account for the largest share of explainable variation for three of the four global ratings items, and the one patient recommendation item included in the survey (willingness to recommend). These findings suggest that plan- and group-level performance measures currently being reported may mask substantial sub-unit variation.

Groups account for the second largest share of variability for most measures, but these effects are modest relative to site-level effects. Medical groups have relatively strong influence on access, accounting for more than 30 percent of the explainable variance for both the access to needed care composite and the timeliness of care measure. Thus, medical groups may be an appropriate focus for interventions designed to improve access, although the particular types of interventions necessary to improve scores in these two areas are likely to be quite different. Group-level effects on the communication and trust composites were smaller. Medical groups also have a strong and consistent influence on global ratings of care. This likely reflects the fact that access and communication scores are the strongest predictors of patients' overall assessment of care (Zaslavsky et al., 2000b).

Our results indicate that higher-level organizations including RSOs and health plans have a more limited effect on those aspects of care measured by the G-CAHPS® instrument. RSOs are the largest source of variability for the measure of getting needed care and explain a sizeable share of variability in both the office staff and coordination of care composites. RSOs' influence over the office staff composite may reflect the role many of these organizations play in the training and hiring of front office staff, a role akin to that played by many physician hospital organizations and management service organizations (Morrisey et al., 1996). Similarly, the substantial influence of these entities over the getting needed care measures may reflect different approaches to utilization management that stem from the de facto delegation of key medical management functions from PCHI to the RSOs, and the role played by many RSO-level medical directors in implementing PCHIs' care management programs.

In this study, health plans account for much less of the variation in measures of patient-reported quality compared to other units of analysis. Exceptions are the office staff and advice composites and the global rating of specialists and office. These results are inconsistent with our hypothesis that plan effects would be restricted to the access composite. The between plan variation in specialist ratings may be due to the fact that the plans in our study contract with different networks or groups of specialists, although we have no information on such contractual arrangements. The differences in advice may well be due to the fact that many plans mail information to members with health promotion and disease prevention advice (e.g. nutrition and cancer screening advice), but we could not measure such activities. We have no explanation for the differences on the office rating and office staff composite. Plans do not hire or train office staff, nor do they directly manage front-line workers.

Our findings have potentially important policy implications. Organizations that routinely monitor care quality, such as the National Committee on Quality Assurance (Beaulieu and Epstein, 2002) and CMS (Goldstein et al., 2001; Zaslavsky et al., 2001) typically assess quality at the plan level. Our results indicate that such assessments may miss substantial intraplan variability. Furthermore, the more closely quality assessments correspond to organizations that individual physicians are associated with, the more salient they are likely to be for consumers (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001) and quality improvement (Berwick, 1991). In Minnesota, the State's health data organization decided to change the unit of analysis for CAHPS® from the health plan to the clinic level because plans' provider networks had become too large and too overlapping to identify meaningful differences at the health plan level. This shift also reflects a change in the purchasing strategy of the area's major purchasing coalition, which now emphasizes direct contracting with clinic-based provider groups.

A major impediment to generating data at the practice site level is that this approach would be considerably more expensive than plan-level assessments. One policy option would be to aggregate data over multiple years to accrue sufficient sample sizes, although long lag times between data collection and reporting may limit the data's usefulness, particularly as a quality improvement tool.

A limitation of this study is that it included only three major health plans and a primary care network that overlaps almost entirely across those plans. Moreover, those plans delegate many critical care management functions to PCHI. Thus, it is not surprising to see little between-plan variation in our quality measures. Zaslavsky and colleagues (2000a) recently found highly significant between-plan variation in CAHPS composites and ratings for a national sample of Medicare managed care enrollees. Although Medicare risk plans provided the least amount of discriminatory power for the delivery system composite compared to other composites, the share of variability attributed to plans for this measure exceeded 35 percent.

The non-random selection of groups also may limit the generalizability of the results. For instance, selection of groups that had the highest improvement potential may result in higher average scores than would a random selection of providers. This potential source of bias is unlikely to influence our estimates of the proportion of variance attributable to each unit of analysis, however.

Independent of any sampling or selection biases, it is important to emphasize that the relative amount of variability in quality due to different organizational units will depend on local conditions and the policies and management strategies of the organizations studied, which usually are area specific. Thus, results in other areas might be quite different. For example, eastern Massachusetts is dominated by academic teaching hospitals and subspecialists with relatively high degrees of physician autonomy and low levels of physician participation in group practices (Center for Studying Health System Change, 1996; American Medical Association, 1999). PCHI's organizational structure is also somewhat unique, especially the structure and function of PCHI's RSOs. However, PCHI and its RSOs are not that different from other “middle-tier” organizations that have been described in the literature (Hillman, Welch, and Pauly, 1992; Welch, 1987; Robinson, 1998).

This study suggests a number of areas for further research. A large share of variance in patients experience of care remains unexplained after accounting for plan-, RSO-, group- and site-level effects. The proportion of variance not explained by health care organizations represents the combined influence of physician- and patient-level variation in patient-reported quality. Additional research is needed to understand the relative influence of individual physicians on patients' assessment of care. Second, a larger study including a greater number of health plans could yield important insights into the influence of plans relative to other health care organizations on key dimensions of quality. Third, more work needs to be done to develop an operational typology of middle-tier organizations based on their structure and the functions they perform. Such a typology could be used to understand how these different types of organizations vary with respect to their influence on care. Finally, we need a better understanding of the mechanisms used by health care organizations to influence care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Terry Lied for his support and guidance during an initial project that examined these issues. We thank the members of the CAHPS® consortium who provided valuable advice regarding the project. We also thank PCHI's Sarah Pedersen and individuals at the practices included in this study for their time and invaluable insights.

Footnotes

Loel S. Solomon is with the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Alan M. Zaslavsky, Bruce E. Landon, and Paul D. Cleary are with the Harvard Medical School. The research in this article was supported under HCFA Contract Number 500-95-0057/TO#9 and Cooperative Agreement Number HS-0925 with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, Harvard Medical School, or the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Reprint Requests: Paul D. Cleary, Ph.D., Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115-5899. E-mail: cleary@hcp.med.harvard.edu

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Development and Testing of the Group-Level Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study Instrument: Results from the National G-CAHPS® Field Test. Rockville, MD.: 2001. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. Medical Group Practices in the U.S.: A Survey of Practice Characteristics. Chicago, IL.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology. Chicago, IL.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu ND, Epstein AM. National Committee on Quality Assurance Health-Plan Accreditation: Predictors, Correlates of Performance, and Market Impact. Medical Care. 2002;40(4):325–337. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200204000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM. Controlling Variation in Health Care: A Consultation from Walter Shewhart. Medical Care. 1991;29(12):1212–1225. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Studying Health System Change. Results from Round II of the Health Tracking Project: Boston Site Visit Report. Washington, DC.: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JM. How Do Purchasers Develop and Use Performance Measures? Medical Care. 1996;33(1):JS18–JS24. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofton C, Lubalin JS, Darby C. Foreword on the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Medical Care. 1999;37(3):MS1–MS9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. The Definition of Quality and Approaches to Its Assessment: Vol 1: Explorations of Quality Assessment and Monitoring. Health Administration Press; Ann Arbor, MI.: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AE. Performance Reports on Quality: Prototypes, Problems and Prospects. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(4):251–256. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood AB, Scott RW, Ewy W, Forrest WH. Effectiveness in Professional Organizations: The Impact of Surgeons and Surgical Staff Organization on the Quality of Care in Hospitals. Health Services Research. 1982;17(4):341–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood AB, Scott WR. Processional Power and Professional Effectiveness: The Power of the Surgical Staff and the Quality of Surgical Care in Hospitals. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19(3):240–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidson E, editor. Doctoring Together: A Study of Professional Social Control. Elsevier Press; New York, NY.: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein E, Cleary PD, Langwell KM, et al. Medicare Managed Care CAHPS®: A Tool for Performance Improvement. Health Care Financing Review. 2001 Spring;22(3):101–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Shaul JA, Williams VSL, et al. Psychometric Properties of the CAHPS® 1.0 Survey Measures. Medical Care. 1999;37(3):MS22–MS31. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Systems Research Inc. Summary of Discussions: Interest and Issues Associated with the Development of Sub-Health Plan Consumer Assessment Surveys. Washington, DC.: 1999. Meeting Summary Prepared for the U.S. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman AL, Welch WP, Pauly MV. Contractual Arrangements Between HMOs and Primary Care Physicians: Three-Tiered HMOs and Risk Pools. Medical Care. 1992;30(2):136–148. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199202000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralewski JE, Wingert TD, Knutson DJ, Johnson CE. The Effects of Medical Group Practice Organizational Factors on Physicians' Use of Resources. Journal of Healthcare Management. 1999;44(3):167–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralewski JE, Rich EC, Bernhardt T, et al. The Organizational Structure of Medical Group Practices in Managed Care Environment. Healthcare Management Review. 1998;23(2):76–96. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199804000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon BE, Wilson IB, Cleary PD. A Conceptual Model of the Effects of Health Care Organizations on the Quality of Medical Care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(17):1377–1382. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, Greenley JR, Cleary PD, et al. A Model of Rural Health Care: Consumer Response Among Users of the Marshfield Clinic. Medical Care. 1980;18(6):597–608. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JA, Wicks EK, Rybowski LS, Perry MJ. Report on Report Cards: Initiatives of Health Coalitions and State Government Employers to Report on Health Plan Performance and Use Financial Incentives. Economic and Social Research Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mittman BS, Tonesk X, Jacobson PD. Implementing Clinical Practice Guidelines. Social Influence Strategies and Practitioner Behavior Change. Quality Review Bulletin. Dec;18(2):413–421. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorehead MA, Donaldson R. A Study of the Quality of Hospital Care Secured by a Sample of Teamster Family Members of New York City. Columbia University School of Public Health and Administrative Medicine; New York, NY.: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey MA, Alexander J, Burns LR, Johnson V. Managed Care and Physician/Hospital Integration. Health Affairs. 1996;15(1):62–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.15.4.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernsetin IH. Psychometric Theory: 3rd Edition. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Orav JE, Wright EA, Palmer RH, Hargraves LJ. Issues of Variability and Bias Affecting Multi-Site Measurement of Quality of Care. Medical Care. 1996;34(9):SS87–SS101. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199609002-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RH, Wright EA, Orav JE, et al. Consistency in Performance Among Primary Care Physicians. Medical Care. 1996;34(9):SS12–SS28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199609002-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JC. Consolidation of Medical Groups into Physician Practice Management Organizations. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(2):144–149. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos NP. The Impact of Organization of Practice on Quality of Care and Physician Productivity. Medical Care. 1980;18(4):347–359. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198004000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin HR, Gandek B, Rogers WH, et al. Patient's Ratings of Outpatient Visits in Different Practice Settings: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270(7):835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran DG, Tarlov AR, Rogers WH. Primary Care Performance in Prepaid and Fee-for-Service Settings: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271(20):1579–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarndal CE, Swensson B, Wretman J. Model Assisted Survey Sampling. Springer-Verlag; New York, N.Y.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon DP, Chernew M, Scheffler S, Fendrick AM. Health Plan Report Cards: Exploring Differences in Plan Ratings. Journal on Quality Improvement. 1998;24(1):5–20. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, Landon BE, et al. National Quality Monitoring of Medicare Health Plans: The Relationship Between Enrollees' Reports and the Quality of Clinical Care. Med Care. 2001;39(12):1305–1312. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert JH, Strohmeyer JM, Carey RG. Evaluating the Physician Office Visit: In Pursuit of a Valid and Reliable Measure of Quality Improvement Efforts. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 1996;19(1):17–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA. The New World of Managed Care: Creating Organized Delivery Systems. Health Affairs. 1994;13(15):47–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.13.5.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortell SM, LoGerfo JP. Hospital Medical Staff Organization and Quality of Care: Results for Myocardial Infarction and Appendectomy. Medical Care. 1981;19(10):1041–1053. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass Correlations: Uses in Assessing Rater Reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86(2):420–429. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Welch WP. The New Structure of Individual Practice Associations. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1987;12(4):723–739. doi: 10.1215/03616878-12-4-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaslavsky AM, Landon BE, Beaulieu ND, Cleary PD. How Consumer Assessment of Managed Care Vary Within and Between Markets. Inquiry. 2000a;37(2):146–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaslavsky AM, Beaulieu ND, Landon BE, Cleary PD. Dimensions of Consumer-Assessed Quality of Medicare Managed-Care Health Plans. Medical Care. 2000b;38(2):162–174. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaslavsky AM, Zaborski LB, Ding L, et al. Adjusting Performance Measures to Ensure Equitable Plan Comparisons. Health Care Financing Review. 2001 Spring;22(3):109–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]