Abstract

In this article, we estimate expenditures by businesses, households, and governments in providing financing for health care for 1987-2000 and track measures of burden that these costs impose. Although burden measures for businesses and the Federal Government have stabilized or improved since 1993, measures of burden for State and local governments are deteriorating slightly—a situation that is likely to worsen in the near future. As health care spending accelerates and an economywide recession seems imminent, businesses, households, and governments that finance health care will face renewed health cost pressures on their revenue and income.

Introduction

In this article, we estimate health care spending by sponsor type—businesses, households, governments, and other private funds; track trends in spending over time; and analyze the burden that these expenditures impose on the sponsoring entities. The basis for these estimates is the national health accounts (NHA), the official Federal Government estimates of total U.S. health care spending (Levit et al., 2002).

This presentation differs from the usual NHA arrangement of sources of funding. The NHA structure includes both expenditures for health care services and sources that pay for these services. These sources generally define an entity, usually a third-party insurer, that is responsible for paying the health care bill. These funding sources are broadly classified into private health insurance (PHI), out-of-pocket spending, and specific government programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid. A small portion of expenditures is estimated for other private revenues—philanthropic giving and revenues received by some health care providers from non-health services (e.g., cafeteria and gift shop sales and revenue from educational services). This structure is useful for tracking changes in who (or what public program) is paying for different types of health care services. It is also useful in analyzing the impact of specific public program policy changes on public or private insurance.

For certain financing decisions and policy issues, however, this structure is not optimal. Often the financial burden of paying for coverage resides not with the bill-paying entity, but with the businesses, households, and governments paying insurance premiums or financing health care through dedicated taxes. These entities frequently decide what health care plan is offered to whom, what cost-sharing arrangements (premiums, copayments, and deductibles) will be imposed, and the breadth and depth of coverage. As health care cost burdens change, the decisions made by businesses, households, and governments in these respects are altered, as are policy responses by government to these decisions. Thus, for many purposes, it is helpful to focus not just on who pays the bills for health care services (as tracked in the traditional NHA) but also on the underlying source of financing for health care.

To estimate the burden of health care, the existing NHA estimates for health services and supplies have been disaggregated and rearranged into categories reflecting the sponsors of health care—businesses, households, and governments. This process includes separately estimating PHI premiums paid by private employers, Federal employers, State and local employers, employees, and individuals. In addition, financing sources for Medicare are estimated and counted with their respective sponsors. These sources include private, Federal, State, and local employer and employee contributions through the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes to the Federal Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund. It also includes Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) premiums paid by individuals and Medicaid “buy-ins.” (Medicaid buy-ins are payments by State Medicaid programs of Medicare Part A and Part B premiums for eligible individuals.) Finally, workers' compensation spending and temporary disability insurance are reallocated to employers who sponsor these benefits.

Although we categorize sponsors into businesses, households, and governments, individuals ultimately bear the responsibility of paying for health care through taxes, reduced earnings, and higher product costs.

This article is an update of earlier articles (Cowan and Braden, 1997; Cowan et al., 1996; Levit and Cowan, 1991; Levit et al., 1989). Consistent definitions have been used throughout these articles. However, revisions to the NHA, the basis for the estimates presented in this article, have resulted in revisions to these sponsor estimates. In addition, data sources have evolved, and consequently the methodology used to produce these estimates has changed. In this article, a major data source change involves information used in the estimation of employer-sponsored health insurance and the shares paid by employers and employees. Since these estimates were last produced, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has released results for the 1996-1999 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey—Insurance Component. Estimates for employer and employee spending for employer-sponsored health insurance depend heavily on this source (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001).

Summary

Businesses, households, and governments are responsible for paying health care costs. The burden that these costs place on the resources of each sponsor can cause them to alter their decisions about the types of PHI plans that are offered or selected, the scope of benefits, and various cost-sharing arrangements. In this article, we have constructed measures to track changes in the burden imposed on these sponsors.

Changes instituted by businesses, including the proliferation of managed care plans, slowed cost growth and halted the upward creep in business burden measures. Similarly, legislative and administrative changes imposed on Medicare, along with a strong economy, led to a decline in the Federal burden measures since 1993. For State and local governments, however, increased pressure from Medicaid has caused burden measures to creep upward slightly despite the use of creative Medicaid financing schemes.

A strong increase in burden measures is anticipated in the future for all sponsors. Early reports from 2001 indicate that premium costs and Medicaid spending are rising at double-digit rates at a time of slowing economic growth, intensified by the events of September 11, 2001, and slowing revenue growth for these sponsors.

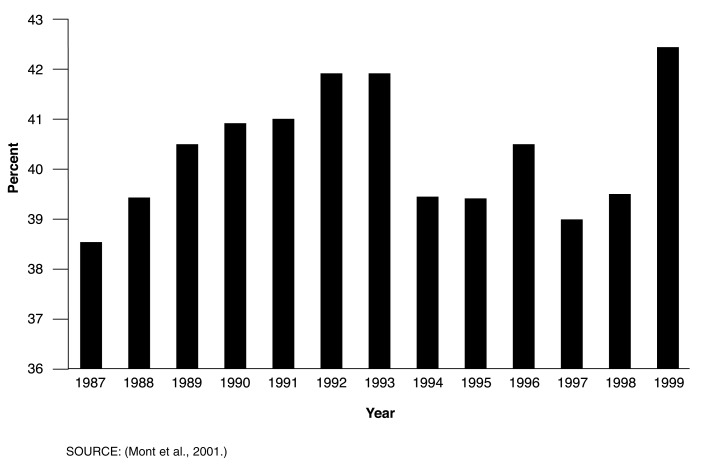

Figure 1. Workers' Compensation Medical Benefits as a Share of Total Workers' Compensation Benefits: United States, 1987-1999.

- Workers' compensation, financed by employers, provides benefits (including medical and rehabilitative expenses and partial wage replacement) to workers sustaining occupational injuries or diseases and survivor benefits to dependents. In 2000, medical benefits of $19.0 billion were paid through Federal and State programs; additional administrative and underwriting costs bring total expenditures to $23.3 billion (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2002).

- All States except Texas mandate and set requirements for workers' compensation. Plans cover most, but not all, workers. The Federal Government maintains its own workers' compensation programs covering Federal civilian employees; longshore, harbor, and other maritime workers; and coal miners with black lung disease.

- From 1960 to 1981, medical benefits accounted for roughly 33 percent of total State workers' compensation benefits, before rising sharply to 42 percent in the early 1990s (Mont et al., 2001).

- Rising medical costs prompted employers to adopt managed care workers' compensation plans, a step that is in part credited with slowing cost growth. Additionally, lower injury rates, benefit changes, safety and return-to-work programs, anti-fraud measures, and tightening of eligibility standards likely contributed to slowing growth (Mont et al., 2001; American Academy of Actuaries, 2000).

- After several years of slowing, expenditure growth is rising again. The waning influence of managed care in controlling costs and an uptick in claim frequency are likely contributors to this trend. In addition, rising copayments and deductibles in non-workers' compensation medical plans may have resulted in some cost-shifting to workers' compensation plans (American Academy of Actuaries, 2000; Mont et al., 2001).

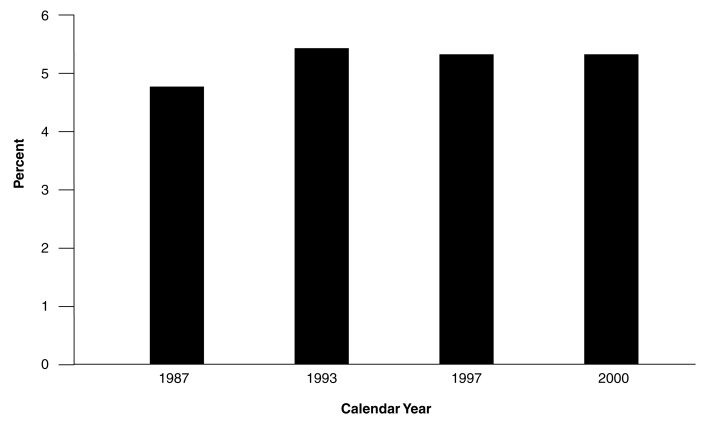

Figure 2. Household Health Spending1 as a Percent of Adjusted Personal Income2: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-2000.

1 Health spending includes premiums for the employee share of employer-sponsored health insurance and individually purchased private health insurance plus contributions and premiums for Medicare and out-of-pocket expenditures.

2 Personal income includes wages and salaries, other labor income, proprietor's income, rental income, dividend and interest income and transfer payments less personal contributions for social insurance. Adjustments to personal income include the addition of Medicare contributions and the exclusion of health benefits payments from Medicaid, Medicare, temporary disability insurance, and workers' compensation.

SOURCES: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: Data from the National Health Statistics Group and (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2001).

- The impact of health care costs on households has remained relatively constant since 1987. Households paid between 4.8 and 5.2 percent of their adjusted personal income for health care. (Adjustments to personal income include the addition of Medicare contributions and the exclusion of health benefit payments from Medicaid, Medicare, temporary disability insurance, and workers' compensation.)

- Overall spending as a share of income masks disparities among households. The poor and the elderly pay a larger share of their income for health care. In 1999, households in the lowest income quintile paid 18 percent of their after-tax income for health care, and households in the highest income quintile paid only 3 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2001). Similarly, households headed by individuals age 65 or over paid 12 percent of their after-tax income for health care in 1999, but households headed by people under age 65 paid only 4 percent.

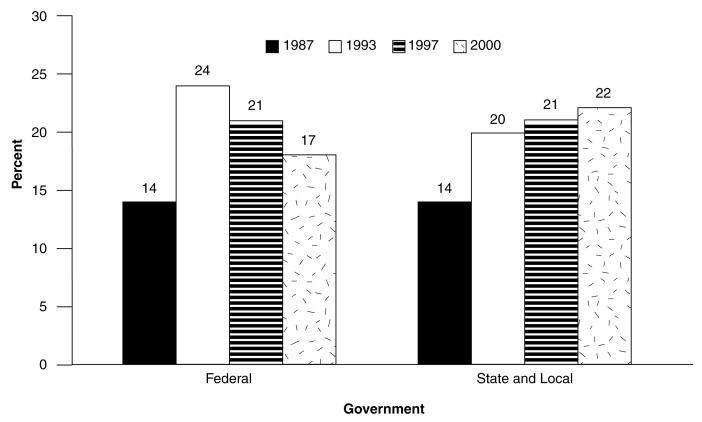

Figure 3. Health Expenditures1 as a Percent of Federal, State, and Local Government Revenues: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-2000.

1 Health expenditures for government include employer contributions to private health insurance for employees, Medicare, Medicaid, and other Federal, State, and local programs.

SOURCES: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: Data from the National HealthStatistics Group and (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2001).

- State and local health care spending as a percent of State and local revenues rose from 14 percent in 1987 to 22 percent in 2000, driven mostly by Medicaid expenditures. This share continued to rise for States despite the use of creative financing and strong State economic growth.

- State and local governments' health care burden is likely to worsen in the near term. In many States, balanced budgets are required. These States are facing budget shortfalls caused by fading economic growth and are considering tightening Medicaid eligibility and cutting benefits to meet this balanced-budget requirement. Every year, the share of Medicaid spending reimbursed by the Federal Government (called the “match rate”) is recalculated. A State's match rate is inversely related to the State's personal income per capita relative to the nationwide average personal income per capita. In other words, States with per capita personal income higher than the average will have lower match rates than States with per capita personal income that are lower than the average. This annual recalculation can reduce the Federal Government's share of Medicaid expenditures in some States while increasing it in others. In addition, Federal Medicaid matching rates in some States declined as of October 2001. At the same time, demands on Medicaid were heightened because of rising unemployment (Ku and Park, 2001; Ku and Rothbaum, 2001).

- Recent cost increases in the Medicaid program have come from the rapidly rising prescription drug and long-term care (including nursing homes and home and community-based waivers) expenditures and increased utilization of services by children (an offshoot of the State Children's Health Insurance Program outreach programs) (Milbank Memorial Fund, 2001).

- Federal health care spending as a percent of revenues peaked in 1993 at 24 percent and then declined to 17 percent in 2000. Medicaid is also a major component of Federal health spending, but it did not place as great a burden on Federal receipts as it did on receipts of State governments.

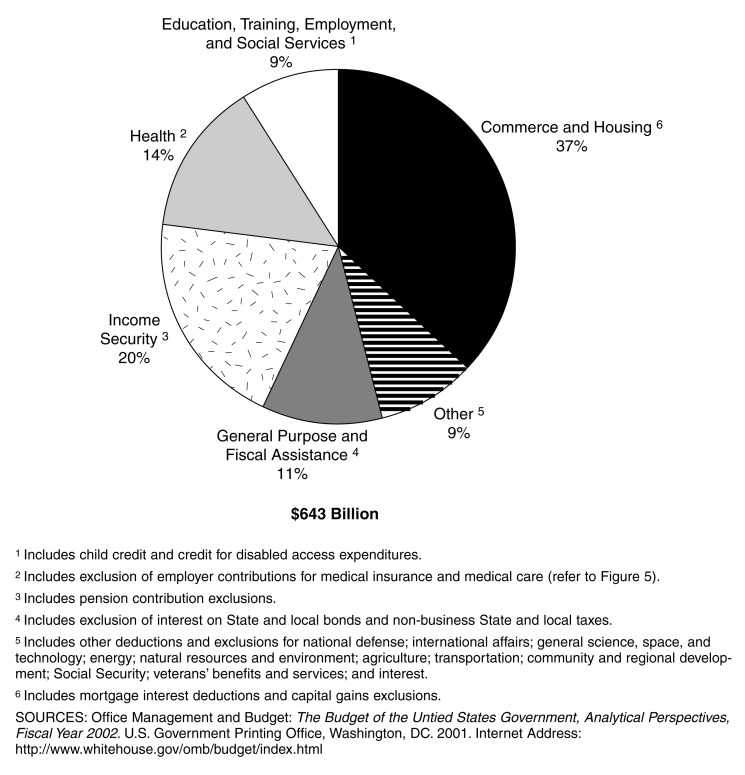

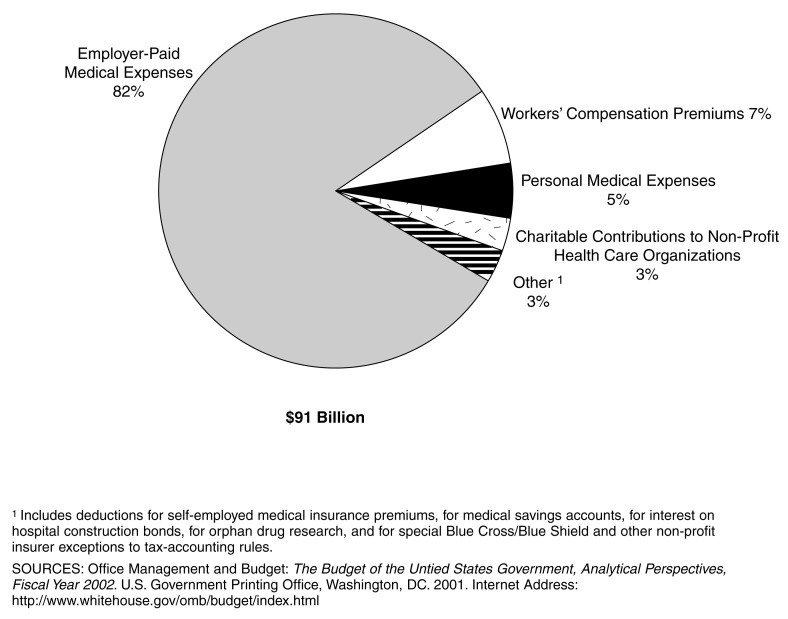

Figure 4. Distribution of Income Tax Loss, by Type of Deduction and Exclusion: United States, Fiscal Year 2000.

- Individuals and corporations are granted preferential treatment under Federal income tax laws that are designed to encourage specific types of economic decisionmaking by taxpayers to achieve social and economic objectives of the Federal Government without direct expenditure of Federal funds. This forgone tax revenue resulting from preferential tax treatment is termed “tax expenditures.”

- In fiscal year 2000, tax expenditures amounted to $643 billion in estimated uncollected revenue due to tax deductions and exclusions (Executive Office of the President, 2001)

- Some policy analysts suggest that these forgone taxes should be included as Federal spending in this and other national health accounting analyses (Fox and Fronstin, 2000; Fronstin and Ostuw, 2000). Such alternative accounting would assign a large share of health insurance premiums currently counted as private spending to the public sector, increasing the share of overall public spending for health care. The accounting principles underlying this seemingly plausible suggestion need careful assessment (Levit, 2000).

- Although the preferential tax treatment is designed to achieve specific social and economic goals set forth by government, it is not included in these types of national income and health accounting formats, such as NHA, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis National Income and Product Accounts, the United Nation's System of National Accounts, and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Health Accounts.

- One reason is that no monetary transaction or flow occurs with tax expenditures. Government expenditures that are counted represent money collected by government that is subsequently distributed to purchase health care. In tax expenditures, the government collects no revenue and makes no purchase of health care. In other words, tax expenditures do not meet the standard definitions used to organize and include funding sources. In the NHA, sources of payment expenditures are defined as the funding sources of financial flows between health care bill payers (third-party insurers or households) and health care providers. In this article, expenditures measure the monetary transactions between health care sponsors and third-party bill payers. Forgone tax revenues do not fit the definitions of these taxonomies.

- It is worth noting that the OECD has constructed a net social expenditure series that recognizes preferential tax treatment in accounts separate from the OECD Health and National Income Accounts (Adema, 2001).

Figure 5. Distribution of Income Tax Loss from Deduction and Exclusions for Health Expenditures: United States, Fiscal Year 2000.

- Various health care-related deductions and exclusions—covering the exclusion of employer-paid medical insurance premiums and medical care from individuals' taxable incomes—account for 14 percent of these tax expenditures. The largest health category of tax expenditure is employer-paid premiums spent for employee and dependent health insurance coverage (Figure 5). In fiscal year 2000, estimated forgone Federal tax revenue from this source reached $77 billion.

- When estimates of forgone tax revenue are discussed in a policy context, they can be misinterpreted. The most common misinterpretation is that repealing specific provisions of the tax law would result in a commensurate increase in Federal revenues, giving rise to the notion that repeal of these provisions could fund health coverage for the uninsured. Tax law provisions provide incentives that are designed to alter economic behavior of individuals and businesses, but these provisions also produce other effects in the health care system and beyond (Executive Office of the President, 2001).

- When employers allocate part of employee compensation to the purchase of health insurance premiums for their workers, part of total compensation is transferred from taxable to tax-exempt income of workers.

- Employers also provide an additional benefit to workers by lowering the average cost of health insurance by creating larger pools of enrollees to share risk.

- By increasing affordability of health insurance, Federal social and economic goals of protection from catastrophic health costs, increased access to health care, and improved health and productivity of workers are assumed to be advanced.

- Among other effects, repeal of these provisions could increase the cost of health insurance, reduce after-tax compensation, swell the roles of the uninsured and the publicly insured, and reduce health status and productivity.

Table 1. Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies, by Type of Sponsors: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-2000.

- Spending for health services and supplies reached $1.3 trillion in 2000, almost three times the 1987 spending level of $477.8 billion. There are two main sponsor components of health services and supplies: private and public.

- The private share of health services and supplies, including spending by business and households, declined significantly between the late 1980s and 1993 (from 69 to 64 percent) and then remained at 63-64 percent through 2000.

- The percent of spending by private business remained relatively stable over the 14-year time span, at around 26 percent. Private business spending includes employer contributions to PHI premiums and to the Medicare HI Trust Fund, as well as expenditures for workers' compensation, temporary disability insurance, and industrial inplant health services.

- Household spending as a share of health services and supplies has declined from 39 percent in 1987 to 34 percent in 1993 and then remained at about that level through 2000. Household spending covers employee contributions to PHI as well as individual policy premiums. Employee contributions and premiums paid by individuals to the Medicare HI Trust Fund and to the Medicare SMI Trust Fund are also included. Out-of-pocket spending is also found in this category.

- Spending by public sponsors (including Federal, State, and local governments) as a portion of total health services and supplies spending rose from 31 percent in 1987 to 36 percent in 1993 and then remained approximately constant over the next 7 years (1994-2000). Medicare and Medicaid are the largest health care programs sponsored by the government. The portion of Medicare costs not financed by earmarked payroll taxes and premiums is counted as Federal Government expenditures in this article. In addition to health insurance premiums paid as a benefit to Federal, State, and local government workers, programs such as maternal and child heath, vocational rehabilitation, and Indian Health Services, as well as services provided through the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense, are incorporated into this category.

| Type of Sponsor | 1987 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| Total | $477.8 | $856.3 | $904.8 | $957.7 | $1,005.7 | $1,053.9 | $1,111.5 | $1,175.0 | $1,255.5 |

| Private | 331.5 | 548.8 | 573.0 | 607.3 | 633.4 | 666.3 | 716.4 | 754.8 | 806.3 |

| Private Business | 123.3 | 223.7 | 237.8 | 251.2 | 265.5 | 270.2 | 288.1 | 307.6 | 334.5 |

| Household | 185.8 | 288.9 | 297.5 | 314.4 | 323.2 | 347.7 | 376.5 | 393.9 | 418.8 |

| Other Private Revenues | 22.4 | 36.2 | 37.7 | 41.7 | 44.7 | 48.5 | 51.8 | 53.3 | 53.0 |

| Public | 146.2 | 307.5 | 331.8 | 350.4 | 372.3 | 387.6 | 395.1 | 420.2 | 449.3 |

| Federal Government | 75.1 | 175.5 | 184.9 | 196.6 | 213.0 | 218.9 | 214.9 | 223.7 | 237.1 |

| State and Local Government | 71.1 | 132.0 | 146.9 | 153.8 | 159.3 | 168.7 | 180.3 | 196.5 | 212.1 |

| Percent Distribution | |||||||||

| Share of Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Private | 69 | 64 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| Private Business | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 27 |

| Household | 39 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 33 |

| Other Private Revenues | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Public | 31 | 36 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| Federal Government | 16 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| State and Local Government | 15 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 17 |

| Percent Growth from Prevous Year Shown | |||||||||

| Growth | — | 10.2 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 6.9 |

| Private | — | 8.8 | 4.4 | 6.0 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 7.5 | 5.4 | 6.8 |

| Private Business | — | 10.4 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 8.7 |

| Household | — | 7.6 | 3.0 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 4.6 | 6.3 |

| Other Private Revenues | — | 8.3 | 4.1 | 10.6 | 7.4 | 8.4 | 6.8 | 2.9 | -0.6 |

| Public | — | 13.2 | 7.9 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 4.1 | 1.9 | 6.3 | 6.9 |

| Federal Government | — | 15.2 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 8.3 | 2.8 | -1.8 | 4.1 | 6.0 |

| State and Local Government | — | 10.9 | 11.2 | 4.7 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 6.9 | 9.0 | 7.9 |

NOTE: Columns may not add to figures shown because of rounding.

SOURCE: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: Data from the National Health Statistics Group.

Table 2. Private Business Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-2000.

- Private business spending equaled $334.5 billion in 2000. The largest component of private business expenditures is the employer contribution to PHI. As a share of businesses' health care expenses, employer contributions for health insurance premiums grew from 69 percent in 1987 to 73 percent in 1993, where they remained almost unchanged through the end of the decade.

- Business contributions to workers' compensation and to temporary disability insurance dropped as a percentage of total private business health services and supplies expenditures from 9 percent in 1987 to 7 percent in 2000. Most of this decline occurred between 1995 and 1997.

- In addition, private employers contribute to the Medicare HI Trust Fund by paying one-half of the FICA taxes on employees' earnings, a portion of which goes into the Medicare Trust Funds. In 2000, these taxes amounted to 18 percent of business' health care expenditures, down from 20 percent in 1987.

- Employers provided onsite health care services in the workplace valued at $4.2 billion in 2000. Expenditures for industrial inplant health services remained relatively constant at around 1 percent of business spending from 1987 to 2000.

| Private Business Spending Category | 1987 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| Private Business | $123.3 | $223.7 | $237.8 | $251.2 | $265.5 | $270.1 | $288.1 | $307.6 | $334.5 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 85.3 | 163.9 | 172.6 | 183.4 | 194.9 | 197.0 | 210.5 | 224.3 | 246.2 |

| Employer Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Payroll Taxes1 | 24.6 | 35.8 | 40.5 | 43.1 | 45.8 | 49.6 | 53.6 | 57.4 | 61.4 |

| Workers' Compensation and Temporary Disability Insurance | 11.7 | 21.1 | 21.6 | 21.4 | 21.4 | 20.0 | 20.2 | 22.0 | 22.7 |

| Industrial Inplant Health Services | 1.7 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.2 |

| Percent Distribution | |||||||||

| Share of Private Business Spending | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 69 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 74 |

| Employer Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Payroll Taxes1 | 20 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 18 |

| Workers' Compensation and Temporary Disability Insurance | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Industrial Inplant Health Services | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Percent Growth from Previous Year Shown | |||||||||

| Growth in Private Business Spending | — | 10.4 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 8.7 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 11.5 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 9.8 |

| Employer Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Payroll Taxes1 | — | 6.5 | 13.0 | 6.5 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 7.0 |

| Workers' Compensation and Temporary Disability Insurance | — | 10.4 | 2.6 | -1.0 | 0.0 | -6.4 | 1.0 | 8.5 | 3.2 |

| Industrial Inplant Health Services | — | 8.8 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.6 |

NOTE: Columns may not add to figures shown because of rounding.

Includes one-half of self-employment contribution to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund.

SOURCE: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: Data from the National Health Statistics Group.

Table 3. Private Business Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies as a Percent of Business Expense or Profit: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-2000.

- Changing health care cost burden can alter the decisions made by health care sponsors. By comparing business health care costs to other input costs and to profits, aggregate changes in burden faced by businesses can be monitored.

- When measured as a share of employee compensation, business burden measures show a jump between 1987 and 1993 but very little change between 1993 and 2000.

- Between 1987 and 1993, employers faced rapid increases in the largest component of business health care costs: health insurance premiums. Real economywide growth was slow or declining, and medical-specific inflation was high (Levit et al., 2001).

- Many employers began offering cost-controlling managed care plans as alternatives to traditional fee-for-service indemnity plans (Levitt et al., 2001). Eager to acquire new business, managed care insurers kept premium growth low for most employers, resulting in strong enrollment growth in these plans.

- By 1997, business health spending as a share of corporate profits fell to its lowest level: 34 percent of before-tax profits and 49 percent of after-tax profits.

- Beginning in 1998 and continuing through 2000, growth in employer-sponsored health care premiums accelerated, as managed care plans tried to cover benefit cost increases and boost profit margins by increasing premiums. The improved economy increased businesses' willingness to absorb premium growth, and the increasingly tight labor market encouraged employers to offer less restrictive (and more expensive) health plans desired by workers (Levit et al., 2001).

- A small increase in corporate profit burden measures resulted, although no difference in business compensation burden measures occurred, as wage growth kept pace with premium increases.

| Year | Business Health Spending as a Share of: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Labor Compensation1 | Corporate Profits2 | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Total Compensation | Wages and Salaries | Before Tax | After Tax1 | |

|

| ||||

| Percent | ||||

| 1987 | 6 | 7 | 39 | 66 |

| 1993 | 7 | 9 | 44 | 65 |

| 1994 | 7 | 9 | 41 | 61 |

| 1995 | 7 | 9 | 38 | 55 |

| 1996 | 7 | 9 | 37 | 53 |

| 1997 | 7 | 8 | 34 | 49 |

| 1998 | 7 | 8 | 40 | 60 |

| 1999 | 7 | 8 | 40 | 59 |

| 2000 | 7 | 8 | 40 | 58 |

For employees in private industry.

A similar concept of “profits” for sole proprietorship and partnerships is not available.

SOURCES: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: Data from the National Health Statistics Group and (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2001).

Table 4. Expenditures of Private Health Insurance, by Sponsor: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-2000.

- In 1987, 91 percent of all PHI was obtained through employer-sponsored health plans. Employers and their workers paid $135.3 billion in premiums. By 2000, employer-sponsored health insurance was 94 percent of total PHI premiums, or $415.6 billion.

- As employees moved into managed care, employers reduced their share of employer-sponsored health insurance premiums from 78.8 percent in 1987 to 74.8 percent in 1998. Despite the more rapid pace of premium growth and employees opting for less managed and more expensive health plans, the tight labor market encouraged employers to pick up a larger share of premiums. By 2000, the employers' share of health insurance premiums increased to 76.4 percent. The level of spending by employers for employer-sponsored health insurance increased from $106.6 billion in 1987 to $317.5 billion in 2000.

- In 1999, 16 million Americans under the age of 65 bought individual health care coverage directly from insurance companies or through non-employer groups (Pollitz, Sorian, and Thomas, 2001).

- Individuals sometimes have difficulty qualifying and paying for individually purchased health insurance. To protect themselves from adverse financial consequences of “anti-selection” by individuals seeking insurance, insurance carriers may decline to cover people who have pre-existing medical conditions. When carriers do offer coverage to such individuals, there may be limitations on coverage or additional charges (Pollitz, Sorian, and Thomas, 2001).

- In 1987, $12.6 billion, or 9 percent of PHI premiums, were individually purchased. By 2000, individually purchased insurance was $28.2 billion, and the share had dropped to 6 percent.

| Sponsor | 1987 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amounts in Billions | |||||||||

| Total Private Health Insurance Premiums | $147.9 | $298.1 | $312.1 | $330.1 | $344.8 | $359.4 | $383.2 | $409.4 | $443.9 |

| Employer-Sponsored Private Health Insurance Premiums | 135.3 | 274.5 | 289.6 | 308.0 | 323.0 | 334.5 | 357.3 | 383.1 | 415.6 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 106.6 | 211.7 | 223.5 | 234.6 | 248.0 | 252.5 | 267.1 | 289.5 | 317.5 |

| Federal Employers | 4.9 | 11.5 | 11.9 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 13.2 | 14.3 |

| Non-Federal Employers | 101.7 | 200.2 | 211.6 | 223.2 | 236.7 | 241.0 | 255.7 | 276.2 | 303.2 |

| Private | 85.3 | 163.9 | 172.6 | 183.4 | 194.9 | 197.0 | 210.5 | 224.3 | 246.2 |

| State and Local | 16.4 | 36.3 | 39.0 | 39.8 | 41.8 | 44.1 | 45.2 | 52.0 | 56.9 |

| Employee Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 28.7 | 62.8 | 66.1 | 73.4 | 75.0 | 82.1 | 90.2 | 93.6 | 98.2 |

| Federal Employers | 2.4 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.3 |

| Non-Federal Employers | 26.3 | 59.0 | 62.2 | 69.6 | 71.0 | 78.0 | 85.0 | 88.7 | 92.9 |

| Private | 22.8 | 51.2 | 54.0 | 60.3 | 61.7 | 67.6 | 73.7 | 76.0 | 79.5 |

| State and Local | 3.5 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 10.3 | 11.3 | 12.7 | 13.4 |

| Individual Policy Premiums | 12.6 | 23.6 | 22.5 | 22.1 | 21.7 | 24.9 | 25.9 | 26.3 | 28.2 |

| Percent Growth from Previous Year Shown | |||||||||

| Total Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 12.4 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 8.4 |

| Employer-Sponsored Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 12.5 | 5.5 | 6.3 | 4.9 | 3.6 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 8.5 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 12.1 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 5.8 | 8.4 | 9.7 |

| Federal Employers | — | 15.4 | 3.2 | -4.8 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 15.7 | 8.2 |

| Non-Federal Employers | — | 11.9 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 1.9 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 9.7 |

| Private | — | 11.5 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 9.8 |

| State and Local | — | 14.2 | 7.6 | 2.1 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 15.0 | 9.6 |

| Employee Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 13.9 | 5.3 | 11.1 | 2.2 | 9.4 | 9.9 | 3.8 | 4.9 |

| Federal Employers | — | 8.0 | 2.7 | -1.2 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 25.5 | -4.4 | 7.2 |

| Non-Federal Employers | — | 14.4 | 5.5 | 11.9 | 2.1 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| Private | — | 14.4 | 5.5 | 11.8 | 2.2 | 9.7 | 9.0 | 3.2 | 4.6 |

| State and Local | — | 14.4 | 5.4 | 12.4 | 1.4 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 11.9 | 5.6 |

| Individual Policy Premiums | — | 11.0 | -4.5 | -1.7 | -1.9 | 14.7 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 7.2 |

| Employer Contribution as a Percent of Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Premiums | |||||||||

| Employer-Sponsored Private Health Insurance | 78.8 | 77.1 | 77.2 | 76.2 | 76.8 | 75.5 | 74.8 | 75.6 | 76.4 |

| Federal Employers | 67.0 | 75.2 | 75.3 | 74.6 | 73.7 | 73.5 | 68.9 | 72.9 | 73.0 |

| Private Employers | 78.9 | 76.2 | 76.2 | 75.2 | 76.0 | 74.4 | 74.1 | 74.7 | 75.6 |

| State and Local Employers | 82.5 | 82.3 | 82.6 | 81.2 | 81.7 | 81.0 | 80.0 | 80.4 | 81.0 |

SOURCES: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: Data from the National Health Statistics Group and U.S. Office of Personnel Management.

Table 5. Household Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-2000.

- Households spent $418.8 billion on health care in 2000. The largest portion of these expenditures was out-of-pocket payments ($194.5 billion), including copayments and deductibles and payments for services not covered by health insurance. Households spent an additional $126.4 billion for PHI premiums, either for individually purchased policies or for the employee share of employer-sponsored PHI.

- From 1987 to 2000, out-of-pocket payments as a share of household spending declined from 59 to 46 percent, while the PHI share increased from 22 to 30 percent. Most of this offsetting change in share occurred from 1987 to 1993. Since then, the out-of-pocket and PHI shares have remained relatively constant.

- Starting in 1993, the share of household health spending for payroll taxes and voluntary premiums paid to the Medicare HI Trust Fund has increased from 15 to 19 percent in 2000. In 1994, the maximum annual HI taxable wage limit was removed. This caused a jump in the share of household spending for HI payroll taxes. Also beginning in 1994, the Medicare HI Trust Fund received income from the taxation of Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) benefits for Social Security beneficiaries whose income exceeds certain thresholds (Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, 2001). In addition, the strong economy and low unemployment rate increased the amount of wages and salaries subject to HI payroll taxes.

| Household Spending Category | 1987 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| Household | $185.8 | $288.9 | $297.5 | $314.4 | $323.2 | $347.7 | $376.5 | $393.9 | $418.8 |

| Employee Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums and Individual Policy Premiums | 41.3 | 86.4 | 88.6 | 95.6 | 96.8 | 107.0 | 116.1 | 120.0 | 126.4 |

| Employee and Self-Employment Payroll Taxes and Voluntary Premiums Paid to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund1 | 29.4 | 43.7 | 50.6 | 55.9 | 59.2 | 62.9 | 68.8 | 74.8 | 81.5 |

| Premiums Paid by Individuals to Medicare Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund | 6.2 | 11.9 | 14.4 | 16.4 | 15.1 | 15.4 | 17.0 | 14.8 | 16.3 |

| Out-of-Pocket Health Spending | 108.9 | 146.9 | 143.9 | 146.5 | 152.1 | 162.3 | 174.5 | 184.4 | 194.5 |

| Percent Distribution | |||||||||

| Share of Household Spending | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Employee Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums and Individual Policy Premiums | 22 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 30 | 30 |

| Employee and Self-Employment Payroll Taxes and Voluntary Premiums Paid to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund1 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 19 |

| Premiums Paid by Individuals to Medicare Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Out-of-Pocket Health Spending | 59 | 51 | 48 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 46 | 47 | 46 |

| Percent Growth from Previous Year Shown | |||||||||

| Growth in Household Spending | — | 7.6 | 3.0 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 4.6 | 6.3 |

| Employee Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums and Individual Policy Premiums | — | 13.1 | 2.6 | 7.8 | 1.3 | 10.6 | 8.5 | 3.3 | 5.4 |

| Employee and Self-Employment Payroll Taxes and Voluntary Premiums Paid to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund1 | — | 6.9 | 15.8 | 10.4 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 9.0 |

| Premiums Paid by Individuals to Medicare Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund | — | 11.5 | 21.0 | 14.1 | -7.6 | 2.0 | 10.3 | -13.2 | 10.2 |

| Out-of-Pocket Health Spending | — | 5.1 | -2.1 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 5.7 | 5.5 |

Includes one-half of self-employment contribution to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund and taxation of Social Security.

NOTE: Columns may not add to figures shown because of rounding.

SOURCE: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: Data from the National Health Statistics Group.

Table 6. State and Local Government Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-2000.

- State and local health expenditures reached $212.1 billion in 2000. Medicaid is the largest component, accounting for 41 percent of all State health care outlays in 2000, up from 32 percent in 1987.

- Some States have used various creative financing schemes to divert Medicaid funds to fungible State budget accounts for use in financing other health and non-health spending.

- The most notable schemes are the disproportionate share hospital arrangements that allow States to pay higher rates to certain hospitals serving a disproportionate share of poor people. The cost of these higher payments is shared with the Federal Government. States have used various tax, donation, and intergovernmental transfer mechanisms to recoup a portion of these payments, thereby raising Federal spending for Medicaid and reducing State and local costs. This controversial practice was limited by congressional action in 1991, 1993, and 1998 (Coughlin, Ku, and Kim, 2000).

- More recently, States have used loopholes in upper payment limits rules affecting local government-owned hospitals and nursing homes to return funds to State general revenues. This practice, too, has caught the attention of the legislative and executive branches of the Federal Government and is being gradually curtailed.

- In the NHA, an adjustment is made to remove disproportionate share hospitals and upper payment limits monies not used directly for patient care from the State portion of Medicaid reimbursements for hospitals and nursing homes. This has generally slowed the growth in State Medicaid expenditures below the growth level for Federal Medicaid spending in the estimates presented in this article.

- The second-largest share of State and local government health expenditures, after Medicaid, is the employer portion of health insurance for State and local government employees. These expenditures amounted to $56.9 billion in 2000.

| State and Local Spending Category | 1987 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| State and Local Government | $71.1 | $132.0 | $146.9 | $153.8 | $159.3 | $168.7 | $180.3 | $196.5 | $212.1 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 16.4 | 36.3 | 39.0 | 39.8 | 41.8 | 44.1 | 45.2 | 52.0 | 56.9 |

| Employer Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Payroll Taxes | 3.1 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 7.3 |

| Health Expenditures by Program | 51.6 | 90.7 | 102.6 | 108.4 | 111.7 | 118.5 | 128.6 | 137.7 | 147.9 |

| Medicaid1 | 22.8 | 45.8 | 53.7 | 59.2 | 61.5 | 66.4 | 73.4 | 80.1 | 86.1 |

| Hospital Subsidies | 10.2 | 11.6 | 12.4 | 11.0 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 11.8 |

| Other Programs2 | 18.6 | 33.4 | 36.5 | 38.1 | 39.8 | 42.1 | 44.4 | 46.5 | 50.0 |

| Percent Distribution | |||||||||

| Share of State and Local Spending | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 23 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| Employer Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Payroll Taxes | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Health Expenditures by Program | 73 | 69 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 71 | 70 | 70 |

| Medicaid1 | 32 | 35 | 37 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 41 | 41 | 41 |

| Hospital Subsidies | 14 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Other Programs2 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 |

| Percent Growth from Previous Year Shown | |||||||||

| Growth in State and Local Spending | — | 10.9 | 11.2 | 4.7 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 6.9 | 9.0 | 7.9 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 14.2 | 7.6 | 2.1 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 15.0 | 9.6 |

| Employer Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Payroll Taxes | — | 8.1 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.4 |

| Health Expenditures by Program | — | 9.9 | 13.0 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 6.1 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 7.4 |

| Medicaid1 | — | 12.3 | 17.2 | 10.3 | 3.9 | 7.9 | 10.6 | 9.0 | 7.6 |

| Hospital Subsidies | — | 2.1 | 7.0 | -10.7 | -6.1 | -3.4 | 7.2 | 3.7 | 5.6 |

| Other Programs2 | — | 10.2 | 9.3 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 7.6 |

Includes Medicaid buy-in premiums for Medicare.

Includes other public and general assistance, maternal and child health, vocational rehabilitation, public health activities, and State Children's Health Insurance Program.

NOTE: Columns may not add to figures shown because of rounding.

SOURCE: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: Data from the National Health Statistics Group.

Table 7. Federal Government Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-2000.

- Federal spending for health care reached $237.1 billion in 2000. Medicaid spending consumes the largest portion (51 percent) of Federal health spending, up from 37 percent in 1987. The adjustments to the State and local Medicaid estimates for the disproportionate share hospitals and the upper payment limits schemes do not apply to the Federal estimates of Medicaid. The result is a boost in the implied Federal matching rates and a more rapid increase in the Federal Medicaid spending than would occur in the absence of these schemes.

- Medicare, the second largest component, accounts for 25 percent of Federal health spending. Federal Government Medicare expenditures equal Trust Fund interest income and Federal general revenue contributions to Medicare less the net change in Trust Fund balances (Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, 2001;Board of Trustees of the Federal Supplementary Insurance Trust Fund, 2001).

- The negative growth in Medicare expenditures in 1998 and 1999 was due to the low growth in disbursements for the Medicare program as legislative changes took affect, heightened fraud and abuse measures, and increased household and employer contributions to the Trust Funds resulting from escalating wages. These factors combined to produce significant increases in Medicare HI Trust Fund assets, which (in effect) are lent back to the Federal Government and serve to offset the Federal financing otherwise required for Medicare. The growth in assets in 1998 and 1999 exceeded the growth in interest payments and general fund payments, thereby reducing the net level of Federal Medicare expenditures in those years.

| Federal Spending Category | 1987 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| Federal Government | $75.1 | $175.5 | $184.9 | $196.6 | $213.0 | $218.9 | $214.9 | $223.7 | $237.1 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 4.9 | 11.5 | 11.9 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 13.2 | 14.3 |

| Employer Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Payroll Taxes | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| Medicare1 | 18.1 | 49.6 | 52.8 | 59.3 | 69.3 | 71.4 | 62.3 | 58.8 | 60.0 |

| Health Program Expenditures (Excluding Medicare) | 50.4 | 112.1 | 118.0 | 123.6 | 130.2 | 133.4 | 139.9 | 151.8 | 165.0 |

| Medicaid2 | 28.1 | 78.1 | 83.1 | 88.1 | 94.2 | 97.1 | 101.9 | 110.8 | 120.8 |

| Other Programs3 | 22.3 | 33.9 | 34.9 | 35.5 | 36.0 | 36.3 | 38.0 | 40.9 | 44.2 |

| Percent Distribution | |||||||||

| Share of Federal Spending | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Employer Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Payroll Taxes | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Medicare1 | 24 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 33 | 33 | 29 | 26 | 25 |

| Health Program Expenditures (Excluding Medicare) | 67 | 64 | 64 | 63 | 61 | 61 | 65 | 68 | 70 |

| Medicaid2 | 37 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 44 | 47 | 50 | 51 |

| Other Programs3 | 30 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 19 |

| Percent Growth from Previous Year Shown | |||||||||

| Growth in Federal Spending | — | 15.2 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 8.3 | 2.8 | -1.8 | 4.1 | 6.0 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 15.4 | 3.2 | -4.8 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 15.7 | 8.2 |

| Employer Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Payroll Taxes | — | 4.7 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 5.5 |

| Medicare1 | — | 18.3 | 6.3 | 12.4 | 16.7 | 3.0 | -12.7 | -5.5 | 2.0 |

| Health Program Expenditures (Excluding Medicare) | — | 14.2 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 4.9 | 8.5 | 8.7 |

| Medicaid2 | — | 18.6 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 6.9 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 8.8 | 9.0 |

| Other Programs3 | — | 7.2 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 4.8 | 7.6 | 8.0 |

Excludes Medicare Hospital Trust Fund payroll taxes and premiums, Medicare supplementary medical insurance premiums, and Medicaid premium payments.

Includes Medicaid buy-in premiums for Medicare.

Includes maternal and child health, vocational rehabilitation, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Indian Health Service, Federal workers' compensation, and other miscellaneous general hospital and medical programs, public health activities, Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, and State Children's Health Insurance Program.

NOTE: Columns may not add to figures shown because of rounding.

SOURCE: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: Data from the National Health Statistics Group.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mark Freeland and Richard Foster for their helpful comments. In addition, we would like to thank John Sommers of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for his help with the MEPS-IC data.

Footnotes

The authors are with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CMS.

Reprint Requests: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, 7500 Security Boulevard, N3-02-02, Baltimore, MD 21244-1850. E-mail: along1@cms.hhs.gov

References

- American Academy of the Actuaries. The Workers' Compensation System: An Analysis of Past, Present, and Potential Future Crisis. American Academy of Actuaries; Washington, DC.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Adema W. Net Social Expenditures. Paris, France: Aug 29, 2001. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Labour Market and Social Policy Occasional Papers No. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. Rockville, MD.: Apr, 2001. Data from the Medical Panel Expenditure Survey–Insurance Component, 1996-1999. Internet address: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/Data_Pub/IC_TOC.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. The 2001 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. Washington, DC.: Mar 19, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Board of Trustees of the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund. The 2001 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund. Washington, DC.: Mar 19, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC.: Jan, 2002. Data from the National Health Accounts, 1960-2000. Internet address: http://www.hcfa.gov/stats/nhe-oact/ [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin T, Ku L, Kim J. Reforming the Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Program. Health Care Financing Review. 2000 Winter;22(2):137–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CA, Braden BR. Business, Households, and Government: Health Care Spending, 1995. Health Care Financing Review. 1997 Spring;18(3):195–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CA, Braden BR, McDonnell PA, Sivarajan L. Business, Households, and Government: Health Spending, 1994. Health Care Financing Review. 1996 Summer;17(4):157–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Executive Office of the President, Office of Management and Budget. Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2002. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fronstin P, Ostuw P. National Health Spending Up 5.6 Percent. Employee Benefit Research Institute Notes. 2000 Jul;21(7):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fox DM, Fronstin P. Public Spending for Health Care Approaches 60 Percent. Health Affairs. 2000 Mar-Apr;19(2):271–273. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.2.271-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan J, Liska D. The Slowdown in Medicaid Spending Growth: Will It Continue? Health Affairs. 1997 Mar-Apr;16(2):157–163. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku L, Park E. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; Washington, DC.: Oct 26, 2001. Federal Aid to State Medicaid Programs is Falling While the Economy Weakens. Internet address: http://www.cbpp.org/10-11-01health.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Ku L, Rothbaum E. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; Washington, DC.: 2001. Many States Are Considering Medicaid Cutbacks in the Midst of the Economic Downturn. Internet address: http://www.cbpp.org/10-24-01health.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Levit KR. The “Right” Accounting Approach: Author's Response. Health Affairs. 2000 Mar-Apr;19(2):273–274. [Google Scholar]

- Levit KR, Cowan CA. Businesses, Households, and Governments: Health Care Costs, 1990. Health Care Financing Review. 1991 Winter;13(2):83–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levit KR, Freeland MS, Waldo DR. Health Spending and Ability to Pay: Business, Individuals, and Government. Health Care Financing Review. 1989 Spring;10(3):1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levit KR, Smith C, Cowan C, et al. Inflation Spurs Health Spending in 2000. Health Affairs. 2002 Jan-Feb;21(1):172–181. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt L, Holve E, Wang J, et al. Employer Health Benefits 2000 Annual Survey. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Research and Educational Trust; Menlo Park, CA.: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Milbank Memorial Fund National Association of State Budget Officers and the Reforming States Group: 1998-1999. Milbank Memorial Fund; New York, NY.: Mar, 2001. State Health Care Expenditure Report. Internet address: http://www.milbank.org/1998shcer/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Mont D, Burton JF, Jr, Reno V, Thompson C. Workers' Compensation: Benefits, Coverage and Costs, 1999 New Estimates and 1996-1998 Revisions. National Academy of Social Insurance; Washington, DC.: May, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitz K, Sorian R, Thomas K. Henry J. Kaiser Foundation; Washington, DC.: Jun, 2001. Individual Health Insurance for Consumers in Less-than-Perfect Health? Internet address: http://www.kff.org. [Google Scholar]

- Smith V, Ellis E. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Oct, 2001. Medicaid Budgets Under Stress: Survey Findings for State Fiscal Year 2000, 2001, and 2002. Internet address: http://www.kff.org/content/2001/4020/4020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. U.S. Department of Commerce; Washington, DC.: Oct, 2001. Data from the National Income and Product Accounts, 1987-2000. Internet address: http://www.bea.doc.gov/bea/dnl.htm. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Department of Labor; Washington, DC.: Oct, 2001. Data from the Consumer Expenditure Integrated Survey Results for 1987-2000. Internet address: http://www.bls.gov/cex/home.htm. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Medicaid: Sustainability of Low 1996 Spending Growth is Uncertain. Washington, DC.: Jun 6, 1997. Letter Report. GAO/HEHS-97-128. [Google Scholar]