Abstract

As part of a CMS-funded study, case studies were conducted in Alabama, Indiana, Washington, Wisconsin, Maryland, Michigan, and Kentucky to assess the major features of the home and community-based services system for older people and younger adults with physical disabilities in each State. The case studies analyzed the financing of services; administrative systems; eligibility, assessment, and case management structures; the services provided, including consumer-directed home care and group residential care; cost-containment efforts; and quality assurance. The role that Medicaid plays in home and community-based services is a major focus of the study.

Introduction

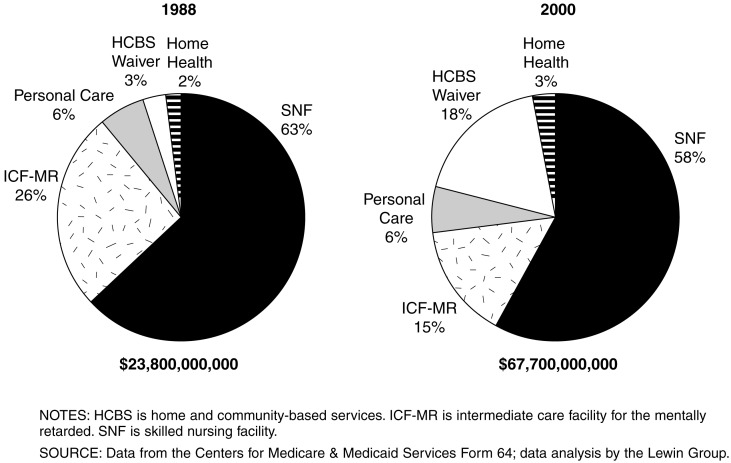

Home and community-based services, such as home health care, personal care, adult day care, respite care, and assisted living facilities, have grown in importance to the long-term care (LTC) system over the past two decades. In 2000, Medicaid non-institutional LTC services constituted 25 percent of total Medicaid LTC expenditures, up from about 10 percent in 1988 (Figure 1) (The Lewin Group, 2000). Among the older population, home and community-based services were estimated to constitute about 30 percent of total LTC expenditures in that same year (U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1999). Despite rapidly growing expenditures for these services, there is a dearth of research documenting the effects of these services on cost, quality of care, or quality of life of both recipients and their families (Lutzky et al., 2000).

Figure 1. Distribution of Medicaid Long-Term Care Spending, by Type of Service.

In the coming years, it is likely that expenditures and utilization of home and community-based services will increase substantially for both demographic and policy reasons. Demographically, largely because of the aging of the population, the number of people with disabilities will increase substantially. Using the 1994 National Health Interview Survey, Rice (1996) projected that the number of people age 65 or over with activity limitations will increase from 12 million in 1994 to 28 million in 2030.

From a policy perspective, creation of a more balanced delivery system by expanding home and community-based services is a major policy goal in almost all States. States' rationales for this shift are that people want to remain in their own homes rather than enter institutions, that the quality of care at home is better than in nursing homes and other institutions, and the belief that these services will save money. In addition, consumer groups for both older people and younger adults with physical disabilities, have pushed for more non-institutional services. The U.S. Supreme Court's Olmstead decision (Olmstead v. L.C. ex. rel. Rimring, 119 S. Ct. 2176 [1999]) found that inappropriate institutionalization was illegal under the Americans with Disabilities Act and established a limited right to home and community-based services, thus providing additional impetus for this policy choice (Rosenbaum, 2000).

States have considerable flexibility in designing their systems of home and community-based services. The aim of this article is to describe and analyze how States address the major issues in the supply, administration, organization, and financing of home and community-based care for older people and younger adults with physical disabilities. After discussing the methodology and providing some basic background information on the seven States, six issues are addressed:

What are the roles of Medicaid and State-funded programs in the financing of home and community-based services; and within Medicaid, what are the roles of mandatory, optional, and waiver services? Although Medicaid provides States with Federal funds, these funds come with a set of requirements with which States must comply.

How are States administratively coordinating the numerous funding streams that finance services, and what is the role of local entities in designing and administering services? The fragmentation of financing may have consequences for the ability of persons with disabilities to access the services they need.

How do States use financial and functional eligibility criteria and the assessment and case management processes to allocate resources? Given the large number of disabled people in the community, States must find ways to decide who will receive services and how much.

What services do States provide under Medicaid and other programs? A major policy issue has been whether and how to broaden the array of services beyond those that have traditionally been covered. States have been particularly interested in exploring consumer-directed home care and non-medical residential settings, such as assisted living facilities.

How do States control expenditures for home and community-based services? Fear of runaway spending has been a major constraint on service expansion, especially at the national level.

Given the chronic problems of quality in LTC, how do States make sure that home and community-based services are adequate? Although the Federal Government overwhelmingly dominates quality assurance in nursing homes, States have enormous flexibility in how they regulate home and community-based services.

Methodology

As part of a research project funded by CMS, The Lewin Group and its subcontractors, the University of Minnesota Research and Training Center on Community Living, The Urban Institute, Mathematica Policy Research, and The MEDSTAT Group, are studying Medicaid financing and delivery of services to older people and younger adults with physical disabilities, as well as to individuals with mental retardation and developmental disabilities.

The study seeks to examine a broad range of State systems of home and community-based services, concentrating on the role of Medicaid. States chosen for inclusion in the study include ones with well-developed systems and States that are still in the process of developing their non-institutional services. The overall goal of the project is to study selected programs to assess their effects on quality of care, quality of life, and cost. CMS seeks to better understand how States organize their LTC systems, their use of Federal Medicaid financing for home and community-based services, and their supplementation with State programs. CMS also hopes to identify features of programs that are associated with favorable outcomes in an ongoing effort to improve service delivery. In addition, information about the effect of individual characteristics and care patterns on outcomes will assist States in targeting and designing their programs.

The first portion of the project involved case studies of the broad range of the supply, administration, organization, financing, and quality assurance of home and community-based services in seven States. In-person site visits were conducted during 1999 and 2000 in States chosen for the study of home and community-based services programs targeted to aged individuals and younger individuals with physical disabilities; visits were also conducted in six States chosen for study of programs targeted to individuals with mental retardation and/or developmental disabilities. Interviews were conducted with State officials, advocacy groups, provider representatives, and other key stakeholders.

This information was supplemented by Web site review, public documents, and newspaper articles. In this article, we present the major case-study findings for the seven States with programs for the aged and physically disabled included in the study. These States were Michigan, Wisconsin, Washington, Indiana, Maryland, Kentucky, and Alabama. Separate reports were written on the home and community-based services system for each State (Wiener and Goldenson, 2001; Wiener and Lutzky, 2001a,b; Tilly and Goldenson, 2001; Tilly, 2001; Tilly and Kasten, 2001a,b).1 The second portion of the project, which is not reported in this article, will survey Medicaid beneficiaries receiving home and community-based services.

Background on State LTC Systems

The publicly funded LTC systems in all of the case-study States spent the substantial majority of their funds on institutions. Although the extent to which States relied on home and community-based services varied greatly, nursing facilities remained the dominant source of care for older persons and younger adults with physical disabilities in all of the States. In recent years, some States have taken aggressive steps to change the balance of care. States expanded home and community services in response to advocates' pressure to provide alternatives to institutionalization, the Supreme Court's Olmstead decision, and as a result of States' efforts to cope with increasing nursing home costs.

The case-study States fell into two broad camps in terms of per capita Medicaid expenditures for home and community services (Table 1). Including Medicaid LTC expenditures for people of all ages, Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Maryland spent less than $55 per capita on these services, while Washington, Wisconsin, and Michigan spent more per capita on non-institutional LTC services. Examining only Medicaid expenditures for older people, Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Maryland spent less than $85 per elderly resident on home and community-based services, while Washington, Wisconsin, and Michigan spent more than $85 per elderly resident on these services.

Table 1. Federal and State Medicaid Expenditures and Per Capita Spending for Home and Community-Based Services, All Ages and Elderly Only: 1998.

| State | Expenditures | Per Capita Spending | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| All Ages | Elderly Only | All Ages1 | Elderly Only2 | |

| United States | $17,542,120,037 | $4,141,305,065 | $64.91 | $120.44 |

| United States Without New York | 13,475,161,839 | 2,882,897,587 | 53.45 | 90.21 |

| Michigan | 645,802,515 | 62,049,201 | 65.76 | 123.54 |

| Washington | 489,400,290 | 99,775,218 | 86.04 | 152.94 |

| Wisconsin | 459,279,907 | 64,123,919 | 87.95 | 92.80 |

| Indiana | 97,156,276 | 13,170,297 | 16.45 | 17.74 |

| Maryland | 234,799,400 | 19,353,076 | 45.77 | 32.73 |

| Kentucky | 204,471,548 | 40,639,017 | 51.97 | 82.48 |

| Alabama | 172,166,180 | 24,195,208 | 39.57 | 42.68 |

Per capita spending for all ages is expenditures for all ages/total population.

Per capita spending for elderly only is expenditures for elderly/elderly population.

NOTES: Home and community-based services includes home health care, personal care, home and community-based services waivers, home and community-based services for frail elderly option, targeted case management, and hospice benefits. HCFA is Health Care Financing Administration.

SOURCE: Urban Institute estimates (2001) based on data from HCFA-64 and HCFA-2082 reports.

Each State's supply of LTC providers differed (Table 2). Indiana and Kentucky had a higher-than-average supply of nursing home beds and correspondingly lower-than-average supply of group residential beds, and both States had an ample supply of home health agencies. Maryland, Michigan, and Washington had an average or lower-than-average supply of nursing home beds and much higher-than-average supplies of residential facility beds, reflecting these States' commitment to the use of these alternatives. Alabama and Wisconsin differed from these bed patterns in that Alabama had a lower-than-average supply of nursing home and group residential providers, while Wisconsin had above average supplies of both types of providers.

Table 2. Long-Term Care Provider Supply in Study States: 1998.

| State | Beds per 1,000 Persons Age 65 or Over |

Number of Home Health | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| Nursing Home | Residential Care | Agencies | |

| United States | 52.5 | 25.5 | 13,537 |

| Michigan | 42.4 | 37.8 | Not Licensed |

| Washington | 41.7 | 49.2 | 159 |

| Wisconsin | 69.7 | 34.5 | 192 |

| Indiana | 85.6 | 4.2 | 277 |

| Maryland | 52.0 | 36.9 | 76 |

| Kentucky | 55.0 | 15.6 | 127 |

| Alabama | 45.3 | 12.4 | Not Licensed |

SOURCE: Harrington, C. et al., 1998 State Data Book on Long-Term Care Market Characteristics, San Francisco, CA, University of California, San Francisco, 1999.

Public Programs

States have fundamental choices regarding how much to rely on Medicaid funding for home and community-based services, what Medicaid optional benefits to cover or home and community-based services waivers to use, and how to fashion State-funded programs. Medicaid dominated financing for home and community-based services in all of the case-study States; State's use of optional services and waivers varied a great deal. Exclusively State-funded programs supplemented Medicaid in all States. Table 3 describes the home and community-based services system in each of the study States.

Table 3. Selected Characteristics of Home and Community-Based Systems in Seven States: 2001.

| Characteristic | Michigan | Washington | Wisconsin | Maryland | Indiana | Alabama | Kentucky |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per capita Medicaid HCBS expenditures greater than $90 for older people | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| State-funded programs have major role | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Single point of entry to public LTC system | No | Yes | No1 | No | Yes | No | No |

| Average case manager case loads greater than 50 under waiver | Yes | Yes | No | Not Available | No | No | Not Applicable2 |

| Medicaid covers personal care outside of waiver | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Covers very broad set of services under Medicaid waiver | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Consumer-directed home care covered under Medicaid waiver for older people | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Services in non-medical residential facilities covered under Medicaid waiver | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Waiting lists for Medicaid waiver services | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Routine consumer satisfaction survey for waiver | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

Except in Family Care demonstration.

Home health agencies do case management.

NOTES: HCBS is home and community-based services. LTC is long-term care.

SOURCES: Wiener, J.M. and Tilly, J., The Urban Institute and Alecxih, L.M.B., The Lewin Group, 2002.

The attraction of Medicaid is that it provides States with Federal dollars, reducing net State costs, but at the price of requiring conformity with Federal rules and regulations. States are required to provide home health care to people requiring nursing facility level of care and may at their option provide it to other groups as well. In addition, four of the case-study States—Maryland, Michigan, Washington, and Wisconsin— offered the optional Medicaid personal care benefit. In Maryland and Michigan, the personal care program represented the largest home and community service program in the State in terms of number of beneficiaries served. States can also use the optional clinic service to fund adult day health care for Medicaid beneficiaries. Adult day health care under the clinic services option played a large role only in Maryland's system, where it constituted the second largest home and community service program in terms of beneficiaries served. All other States covered adult day care in their Medicaid waivers.

Offering optional services under the regular Medicaid program can be done with administrative ease but has two important constraints. First, States must offer home health care, personal care, clinic, and other services as an open-ended entitlement—a legal obligation on the part of government to provide services to individuals who meet pre-established criteria, regardless of the cost to the government. This characteristic makes States potentially vulnerable to large expenditure increases due to increased demand by the high percentage of disabled people in the community who are not receiving paid services. Second, these options also constitute a fairly narrow range of services and may not effectively maintain people with disabilities in the community.

The potential fiscal exposure has prompted States to rely on Medicaid home and community-based services waivers to finance their non-institutional LTC services because waivers offer States greater control over expenditures. Under Section 1915c) of the Social Security Act, States may apply to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for Medicaid home and community-based services waivers designed to allow States greater flexibility to meet the needs of community-dwelling persons with disabilities. States must limit these waiver programs to beneficiaries who meet the State's level-of-care criteria for nursing homes, intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded, or hospital services, because the waivers were intended to substitute non-institutional for institutional care. For the older population and younger adults with physical disabilities, the comparison institution was almost always nursing home care. In addition, States must establish in advance how many people they will serve during the course of a year. In contrast to the regular Medicaid program, States may establish waiting lists for these waiver programs; thus, the waivers operate as a non-entitlement program within the confines of a program that is normally an entitlement.

In addition, average expenditures for waiver beneficiaries must be the same or less than they would have been without the waiver. As a practical matter, for older people and younger adults with physical disabilities, this usually meant that average expenditures had to be equal to or less than the average cost of Medicaid nursing home care. States may cover a very wide range of services, including case management, homemaker, or home health aide services, personal care services, adult day health care, habilitation, respite care, non-medical transportation, home modifications, adult day care, and other services approved by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services. Although services in congregate residential facilities may be covered, room and board are excluded from Medicaid coverage. Room and board may only be covered in nursing homes, intermediate care facilities, and hospitals.

In 2000, all 50 States and the District of Columbia had Medicaid home and community-based services waivers for older people and younger persons with disabilities. However, like other aspects of Medicaid, States varied in the degree to which they used waivers to fund home and community services. Alabama, Indiana, and Maryland had small waiver programs measured in terms of per capita beneficiaries and spending, while Kentucky, Michigan, Washington, and Wisconsin had relatively large waiver programs.

In recent years, some States have expanded or implemented new waivers, sometimes refinancing existing State programs in order to obtain the Federal match. For example, Kentucky used a portion of the monies previously devoted to two of its State-funded programs to meet Medicaid's matching requirements for two new waivers, which were designed to reduce waiting lists for the State-funded programs. As another example, Michigan dramatically increased the number of places, or slots, available under its aged and disabled home and community services waiver from about 4,000 in fiscal year 1998 to 15,000 in fiscal year 2000.

Although Medicaid dominated funding, State-funded programs rounded out the home and community-based service system. These programs were designed to fill in coverage by offering services that Medicaid will not cover or by extending eligibility to persons who do not meet Medicaid's financial or functional eligibility criteria. Each State had at least one small program that provided targeted services such as supplements for residents of board and care homes or adult day care. Wisconsin, Indiana, and Kentucky had large, exclusively State-funded programs serving more than 10,000 people each.

Administrative Structures

Because of the multiplicity of funding sources for home and community-based services, each with their own eligibility criteria and set of services, States face a challenge in coordinating programs. Another issue States must address is how to administer programs at the local level, where beneficiaries access services. Most States spread the administrative responsibilities for home and community-based services over several State agencies, sometimes making coordination difficult. Fragmentation of responsibility was a common complaint by consumer advocacy groups. This multiplicity of administrative responsibilities was especially true for State-funded programs, which were sometimes administered by agencies completely separate from Medicaid.

For home and community-based services, States devolved substantial responsibility for program administration and, in some cases, program design to sub-State organizations. All of the case-study States relied on local entities—area agencies on aging, counties, area development agencies, waiver agents, or home health agencies—to help administer home and community-based services programs. In some cases (e.g., Alabama), the local agencies just handled administrative tasks; in other States, their responsibilities included budgeting, contracting, service delivery, and program design (e.g., Wisconsin for Medicaid waivers and State-funded programs). State officials and stakeholders in the case-study States said that local involvement in program administration can help tailor programs to local needs and preferences but can lead to variation in implementation of policies and available services. The administrative fragmentation at the State level was often compounded by fragmentation at the local level, and few States had a single point of entry to the LTC system. Consumer advocates indicated that the multiplicity of points of entry confused clients and raised questions of whether people can find the right program to meet their needs.

Case-study States employed three broad approaches to administering their programs: (1) housing all programs in one department of State government and relying on local entities to administer services using a single point of entry (Indiana and Washington); (2) creating a large role for State government and home health agencies with a relatively small administrative role for other local organizations (Alabama and Kentucky); and (3) fragmentation of administration at the State and local levels (Maryland, Michigan, and Wisconsin).

Of all of the case-study States, Maryland had the most complicated administrative structure. The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene administered the Medicaid home health care, personal care, and adult day care benefits. This agency also jointly administered waivers for older persons with the Department on Aging and waivers targeted to younger persons with physical disabilities with the Department of Human Resources. The State also had one State-funded program in the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, three State-funded programs that served older persons in the Department of Aging, and four State-funded programs in the Department of Human Services that served adults of all ages. People with disabilities could access these programs through local area agencies on aging, departments of public health and social services, or through non-profit agencies. Stakeholders in Maryland complained that the lack of coordination among programs at the State and local levels stemmed from the administrative structure. To cope with administrative complexity, the State developed an interagency coordinating committee for programs serving the older population and local coordinating committees, although consumer advocates indicated their effectiveness varied by locality.

In contrast, Indiana had the simplest administrative structure. It housed all home and community services for its older population and for those age 18-64 with physical disabilities in one department of State government. Although some of the administrative functions were separated among divisions within the department, policymaking and administration appeared to run smoothly from the perspective of State government and key stakeholders. At the time of the site visit, many of the key staff had been in State government for more than 10 years, and a strong consumer coalition had been active for about the same amount of time. In addition to a cohesive State-level structure, local area agencies on aging served as the single point of entry for all home and community services programs in Indiana. Although stakeholders indicated that local variation in implementation of State policy occurred, no one complained that potential beneficiaries faced uncertainty about how to access services at the local level. In fact, key stakeholders commented that the single point of entry facilitated beneficiaries' access to services.

Two States—Michigan and Wisconsin— adopted innovative approaches to management at the local level. Michigan contracted with multiple “waiver agents” at the local level to manage waiver funding and services. In this approach, the State explicitly rejected the notion of a single point of entry for beneficiaries. Instead, the State wished to create choices for consumers by having more than one high-quality waiver agent in each region. According to some stakeholders, the result has been confusion for beneficiaries and lack of coordination at the local level. State officials countered that lack of coordination is to be expected among competing agencies but that the system created compensating advantages.

Under a combination freedom-of-choice and home and community-based services waiver, Wisconsin embarked on a demonstration project called Family Care in 1999, which includes two major components: county-administered aging and disability resource centers and care management organizations. The resource centers offer a wide range of information and counseling on LTC services and providers, functioning as a single point of entry into the LTC system. Care management organizations serve as capitated, managed care organizations for institutional and non-institutional LTC services. Funding for LTC from Medicaid, State, and county programs was consolidated into single monthly capitated payments to care management organizations. The goal was one “pot” of money that could be used to create a seamless system in which individuals' needs dictate service provision, rather than program demarcation.

Eligibility, Assessement, and Case Management

To make sure that limited resources are targeted to the populations most in need, States have developed various mechanisms to allocate resources and to match individuals with services. Applicants for public programs must be assessed to determine whether their disabilities are severe enough to meet States' functional eligibility tests and whether beneficiaries' incomes and assets are low enough to meet financial eligibility criteria. Medicaid programs are limited to the low-income population, and waivers are restricted to people with relatively severe levels of disability, but State programs often are far more liberal in terms of both functional and financial eligibility. If an applicant met both types of tests, a case manager—employed by the State, a contractor or a provider—then arranged a service plan in consultation with the beneficiary and helped ensure delivery of quality services. Case management, however, was often limited to people in the waivers and was usually not available for the people receiving only Medicaid home health care or personal care services.

Functional Eligibility

Functional eligibility requirements varied by service and by source of funding. In most of the case-study States, eligibility for the Medicaid home health benefit followed the medical model, personal care programs provided assistance to those who needed help with daily activities, and waivers provided services to those meeting institutional (usually nursing home) level-of-care criteria. The large State-funded programs tended to have less restrictive functional eligibility criteria than the Medicaid home and community-based services waivers. These generalizations mask a great deal of variation in program eligibility among the case-study States, particularly related to the nursing home level-of-care criteria.

The States provided the mandatory Medicaid home health service when a physician ordered medically necessary services for a beneficiary. Kentucky provided extensive home health aide services under the home health benefit, generally when a person who had a skilled need experienced an improvement in his or her condition but still needed personal care and other services.

The States with the optional personal care program—Maryland, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Washington—offered this service to anyone who needed help with at least one daily activity. Maryland and Wisconsin limited eligibility to one or more activities of daily living such as eating, bathing, and dressing, while Michigan and Washington included instrumental activities of daily living such as medication management. These criteria for personal care were uniformly less restrictive than for Medicaid waivers.

As required by Federal law, all clients of the Medicaid home and community-based services waivers were assessed as needing an institutional level of care; for older people and younger adults with physical disabilities, this was most commonly the nursing facility level of care. In the absence of Federal standards, the nursing home level-of-care criteria varied markedly among the case-study States. For example, Michigan relied largely on professional judgment, while Alabama required a daily need for nursing, among other medically related criteria. Indiana had the least stringent criteria, only requiring limitations in 3 of 14 daily activities. Somewhat surprisingly, none of the case-study States narrowed eligibility by requiring a high “risk of institutionalization” in addition to meeting the institutional level-of-care criteria as a way of increasing the substitution of home care for institutional care. This federally established linkage between functional eligibility for the waivers and nursing home care meant that States could not expand functional eligibility for the waivers without also liberalizing eligibility for institutional care, creating a dilemma for States that wished to use the waiver mechanism to cover a broader population.

Functional eligibility requirements for the major State-funded programs tended to be less restrictive than for the Medicaid home and community-based services waivers. For example, in addition to persons who met the nursing home level of care, Wisconsin's Community Options Program served current residents of nursing homes or State centers for the developmentally disabled, even if they did not need that level of care. In addition, the program served persons having a chronic mental illness or those who were likely to require long-term or repeated hospitalization without community services and individuals who had been diagnosed as having Alzheimer's disease.

Financial Eligibility

States universally use financial criteria for most programs to limit eligibility to predominately the low-income population. Study States used roughly similar financial eligibility criteria for Medicaid, but eligibility for large State-funded programs varied markedly. States made Medicaid home health care and personal care services generally available to categorically eligible (mostly Supplemental Security Income [SSI] beneficiaries) or medically needy persons, depending on the State's normal Medicaid eligibility coverage. However, Washington limited personal care services to those categorically eligible for Medicaid. Waiver programs were generally available to individuals with incomes at or below 300 percent of the SSI payment level, which is the special income level for institutional care; Wisconsin extended services to those who were medically needy as well. Alabama provided eligibility up to 300 percent of the SSI payment level for its “homebound waiver,” but only up to 100 percent of the SSI level for its “elderly and disabled waiver.” Kentucky, Michigan, and Wisconsin provided community-based spouses of waiver beneficiaries with the protection against impoverishment, an option for State waiver programs but mandatory for spouses of nursing home residents.

Two States had very generous financial eligibility criteria for their State-funded programs. Indiana and Kentucky had sliding fee scales and no asset tests. In Indiana, people with incomes at or below 350 percent of the Federal poverty level received some State subsidy; in Kentucky, the annual income level at which beneficiaries stopped receiving a subsidy for their service costs was $16,651 in 2000. Washington also used a sliding fee scale but imposed an asset test of $10,000. Wisconsin's State-funded program had a unique feature that allowed people who were likely to spend down to Medicaid within 6 months to qualify; the effective asset test in 2000 was $25,725. Consumer advocates tended to view asset tests as a barrier to accessing home and community services and sought their liberalization or elimination.

Assessment and Case Management

Assessment and case management are closely related but separate functions. Assessment determines whether an individual is eligible for the program, while case management authorizes the services that the client receives. In most States, State or local organizations, such as area agencies on aging, generally assessed functional eligibility for the purpose of determining eligibility for the programs. Local organizations separate from service providers usually performed case management for those determined to be eligible for services. For example, in Washington, local offices of the State Aging and Adults Services Administration (AASA) assessed eligibility and, for those who went on to receive home and community services, area agencies on aging took over case management functions. Local AASA offices provided case management for all other beneficiaries that received LTC in institutions or group residential settings. In the study States, case management was often limited to waiver programs and not provided to people receiving only personal care or home health care.

Most States separated assessment and case management from service provision to avoid potential conflict of interest. When these services are combined, providers have an incentive to assess clients so that they will become eligible and then to propose services that benefit the provider doing the case management. Kentucky was an exception to this separation; home health agencies (HHAs) performed assessments and case management and also provided many of the services. To protect against conflict of interest, the quality improvement organization reviewed the decisions of the HHAs. Alabama's Department of Public Health also performed both assessment and case management and provided direct services to Medicaid beneficiaries; the State sought to avoid conflict of interest by placing these functions in different divisions of the department.

Case managers in the case-study States arranged for services to meet the needs of beneficiaries. Philosophically, all of the States emphasized tailoring services to the individual's unique needs. Michigan, for example, used “person-centered planning,” where case managers negotiated service plans with waiver beneficiaries or their representatives and then arranged for home care agencies to deliver services. Case managers periodically contacted beneficiaries to monitor services and reassessed need when required. For beneficiaries directing their own workers (i.e., hiring, firing, and managing individual workers), case managers' contact tended to be less frequent.

The caseloads for case managers varied a great deal, from 35-50 clients for the waivers in Alabama to as many as 100 clients in the personal care program in Michigan. Most advocates for younger adults with disabilities in the study States wanted less intensive case manager oversight because they contended that beneficiaries did not need such assistance. State officials who oversaw consumer-directed programs generally concurred. In contrast, home care agency providers and some State officials asserted that case manager oversight was crucial to avoiding incidents of worker abuse or neglect.

Services

As States expand funding for home and community-based services, officials must decide the range of services and the degree of flexibility to offer. Consumer advocates, especially for younger persons with disabilities, stressed that each individual is different and that only a very wide range of services can meet their unique needs and successfully integrate them into the community. Some States were reluctant to offer a wide range of services, worrying about the high potential level of demand and their ability to monitor quality of care in these non-traditional services. Medicaid State plan home health care, adult day health care, and personal care services are a relatively narrow set of services; in contrast, the waivers provide the most flexibility. States fell into two camps with regard to their waivers—Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Maryland covered a relatively basic set of services, while Michigan, Washington, and Wisconsin offered a very wide array of services. In a few States, including Wisconsin and Indiana, substantial State-funded programs provided a “gap-filling” function by ensuring that beneficiaries received needed services that Medicaid did not cover. The States differed in the extent to which they offered Medicaid services outside of a person's home, in group residential settings, or under a consumer-directed model.

Home Health Care

The case-study States' home health benefit consisted of a traditional set of nursing, therapy, and home health aide services provided by certified agencies. Only in Kentucky, and, to a lesser extent Alabama, did Medicaid home health care play a significant role in the LTC services system. In Alabama, as in much of the South, the Department of Public Health served as the primary provider of Medicaid home health services, receiving a substantially higher reimbursement rate than did private agencies. Because of reductions in Medicare revenue following the changes in the Medicare home health payment system mandated by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, departmental home health expenditures dropped by about 50 percent in Alabama and continued to decline in 2000. In addition to reimbursement changes, as many as 20 percent of the Department of Public Health's home health patients were disqualified from home health care as a result of the elimination of venipuncture as a service qualifying an individual for Medicare home health care. Largely as a consequence, Medicaid home health care utilization increased significantly, expenditures doubled, and the number of beneficiaries increased by 30 percent between fiscal years 1997 and 1999.

In contrast, in Kentucky, Medicare's home health payment changes did not affect the Medicaid home health benefit or the industry to any great degree; the State reported no unusual increases in the numbers of Medicaid participants served, and few agencies went out of business. Stakeholders asserted that certificate of need requirements for HHAs kept provider supply under control and, as a result, Kentucky did not experience the rapid growth in the number of agencies in the 1990s as did the rest of the country. Therefore, existing HHAs had sufficient beneficiary volume to remain in business.

Personal Care

The four case-study States that covered the optional Medicaid personal care benefit—Maryland, Michigan, Washington, and Wisconsin—generally offered help with daily activities such as eating, bathing, and dressing, but had varying restrictions on service delivery. For example, Maryland would not pay for these services in certain group residential settings, while Michigan and Washington would in most facilities.

A complex relationship often exists between the personal care option services and home and community-based services waivers. First, in every State that covered it, personal care provided community-based LTC services to people who did not have the functional level of disability to qualify for the waiver (i.e., the nursing home level of care), as well as to those persons who did but for whatever reason did not want or need the broader range of waiver services. Second, as a way of maintaining people in the community, the States with the personal care option provided these services to individuals on the waiting list for waiver services that met standard Medicaid financial eligibility criteria. Third, in some States, people receiving waiver services obtained their personal care through the personal care benefit rather than through the waiver mechanism.

As disabled consumers have attempted to become more integrated into the community, the provision of personal care services outside of the home has increasingly become an issue. Washington, Wisconsin, and Maryland required beneficiaries to receive Medicaid personal care services in their own homes, while Michigan authorized personal care outside of the home. Advocates for younger people with disabilities in States that restrict service provision to the home contended that this limitation impeded their ability to work and to participate in family and community life, limiting their ability to be integrated into the overall society. Consumer advocates also pointed out that lack of transportation, other than to doctors' appointments, also contributed to beneficiary isolation.

Waiver Services

States used Medicaid home and community-based services waivers to provide a more flexible array of services than those available under the regular Medicaid program. Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Maryland's waivers provided a relatively narrow set of services, including case management, adult day care, personal care, and respite services. Among these States, only Maryland allowed for the delivery of waiver services in assisted living facilities.

In contrast, Michigan, Washington, and Wisconsin provided a much broader array of assistance that included basic services, plus such things as counseling, meals, environmental modifications, supplies and equipment, emergency response systems, and training. Wisconsin offered the broadest array of waiver services among the case-study States. In all States, the broader service packages sought to ensure that beneficiaries, who would have otherwise entered a nursing home, had access to the services they needed to remain at home or in the community.

Like the Medicaid personal care benefit, some States permitted services outside the home, and others did not. Alabama, Washington, and Kentucky required that most waiver services, except adult day care, be delivered in the client's home, but Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan allowed services to be provided in the broader community. Some States, however, lacked consistency within Medicaid. For example, although Wisconsin did not allow personal care services to be provided outside of the home, the State permitted waiver services to be provided in the community.

As some of the study States moved toward consumer-directed care, non-medical residential services, and a very flexible set of services, their waiver service mix has become less medically oriented. Washington and Wisconsin have had a particularly strong commitment to a social model of care, which maximizes consumer involvement. At the same time, however, the targeting criteria of the Medicaid waivers has meant that the clients served by home care programs are more severely disabled than in the past and sometimes have a mix of complicated chronic illnesses requiring a combination of medical and social services. States that strongly endorsed a social model of care are just beginning to address this issue. Washington, for example, beefed up the medical and nursing oversight available for waiver residents and began to explore the integration of acute and LTC services.

State-Funded Programs

State-funded programs included services designed to either finance very specific services or to fill the gaps in Medicaid coverage. As an example of funding very specific services, Maryland and Michigan had programs designed to provide supplemental payments to people residing in group residential facilities and assisted living facilities.

At the other extreme, Indiana and Wisconsin both had State-funded programs with very flexible service structures. In Indiana, the Community and Home Options to Institutional Care for the Elderly (CHOICE) program covered a category of service called “other necessary services,” which could include virtually any service that a person needed to stay at home. Examples of these services included pest extermination services and Russian translation. Stakeholders viewed flexibility as a key factor in the popularity of the State-funded program in Indiana and wanted to see the Medicaid waiver programs have similar flexibility. State staff reported that about 25 percent of aged and/or disabled Medicaid waiver participants were CHOICE beneficiaries because they needed services the waiver did not cover. In Wisconsin, under the State-funded Community Options Program, counties could select any service necessary to implement a community-based living arrangement for an individual, except for certain limitations on the use of non-medical residential facilities. As with the Indiana program, the State spent a significant portion of State funds for that program for persons who received Medicaid waiver services.

Innovative Services

Over the last 10 years, some of the case-study States have broadened their array of services. Two major innovations in the delivery of home and community services for older people and younger persons with physical disabilities have emerged: group residential settings, such as assisted living facilities, and consumer-directed home care. Both sets of services are intended to increase consumer empowerment, autonomy, and choice, but raise important issues of accountability and quality assurance.

Group Residential Settings

Ideally, group residential facilities, such as assisted living facilities and adult family homes, provide the economies of scale in service provision available in a congregate facility without the institutional, more medical setting of a nursing home. These congregate settings can be especially useful for some people with Alzheimer's disease, who need a great deal of supervision but not a great deal of hands-on care. Services in group residential facilities, such as assisted living facilities, may be covered through the Medicaid home and community-based services waiver and through the personal care program. Under Federal law, however, room and board costs may only be covered in institutions, such as nursing homes. Among the case-study States, non-medical residential facilities constituted a large component of the publicly financed service delivery system in Washington and Wisconsin. In Alabama and Kentucky, State regulations specifically prohibited these facilities from providing services to people who needed a nursing facility level of care, hence, beneficiaries residing there could not qualify for the waiver. However, in Kentucky, the home health benefit could be delivered in group residential settings; and, in Michigan, personal care could be delivered in these settings. Indiana did not cover care in group residential settings, but it was considering whether to do so. Maryland provided Medicaid coverage of services in assisted living facilities on a small scale through a waiver, which it expanded in 2000 to cover more beneficiaries.

Washington and Wisconsin made extensive use of assisted living and other group residential settings under their Medicaid waiver programs. Washington enthusiastically embraced these settings, covering adult family homes, assisted living facilities, and “adult residential care.” The waiver financed fully 95 percent of publicly funded persons receiving services in these settings; about 4 percent of residents received Medicaid personal care, and the State-only program funded less than 1 percent of residents.

Influenced heavily by Oregon, Washington's Medicaid policy on assisted living facilities emphasized the philosophy of “aging in place,” the use of “negotiated service agreements,” and “managed risk.” Structural requirements for Medicaid participation exceeded the licensing requirements for assisted living facilities. Under Medicaid, newly constructed assisted living facility units must include individual apartments and provide limited nursing services.

In contrast, Wisconsin used residential facilities only reluctantly because State officials believe it is better for people to stay in their own homes. Nonetheless, the Medicaid waiver funded services in group residential settings, including adult family homes, community-based residential facilities, and residential care apartment complexes, although most residents in these facilities paid privately. Care for Medicaid beneficiaries in these settings accounted for approximately 20 percent of waiver expenditures. Community-based residential facilities served relatively heavy care individuals, had registered nurses on staff, and consisted mostly of rooms with baths. Residential care apartment complexes, formerly known as assisted living facilities in Wisconsin, could provide up to 28 hours a week of care and were not heavily regulated.

State officials and stakeholders had mixed opinions about the delivery of home and community services in group residential settings, with opinion split within both groups. Advocates of delivering services in such settings believed that these facilities allowed people with disabilities to receive access to housing that they might not otherwise have and that these settings provided a homelike environment and a good alternative to nursing facilities. Perceived cost savings were a factor for some State officials. Critics of group residential settings said that these settings, especially large ones, often proved to be more like nursing facilities than homes, and sometimes smaller facilities provided inadequate access to the community (e.g., were not wheelchair accessible). In addition, critics raised safety and quality of care issues regarding the provision of medically related services for which staff had little or no training and the lack of provision of necessary services. States particularly struggled with how to allow people to age in place and provide them with the services they needed without turning these facilities into unlicensed or substandard nursing homes.

Consumer Direction

A key issue in the design of home and community-based services programs is the extent to which clients control their services. Consumer involvement in managing publicly funded Medicaid and State-funded programs ranges from very little to virtually complete control over services. In the study States, as in the rest of the country, agencies provided the vast majority of home care services, assuming the responsibility for hiring, training, directing, scheduling, and firing workers. Under a consumer-directed model, the individual client has responsibility for these functions. An increasing number of States, including Washington, Wisconsin, and Michigan, give disabled clients of all ages, including those with severe disabilities and cognitive impairments (usually with the help of informal caregivers or surrogate decisionmakers), the ability to choose and direct independent providers as a way of empowering clients and saving public dollars. Although the ideology of consumer-directed care emphasizes individuals going into the marketplace to choose their workers, the case-study States that offered this option reported that a high percentage of people picked family members or persons they already knew. For example, family members constituted about one-half of the independent providers in Washington and Michigan. Some public officials expressed concern about quality of care under consumer direction and the possibility that payments may function more as an income supplement to the family rather than as a mechanism to provide care for the participant.

A number of years ago, 9 of Indiana's 16 area agencies on aging used State funds to have beneficiaries hire and fire their own workers. However, after a U.S. Internal Revenue Service ruling that might have required area agencies on aging to treat these workers as their employees, the number of agencies offering this option dropped to three. Recently, legislators authorized a pilot program on consumer-directed care. However, most area agencies on aging expressed reluctance to implement consumer-directed care because they believed case managers would have additional burdens related to monitoring individuals and the quality of care. They also raised concerns about the risks to beneficiaries when workers without backup fail to show up when scheduled.

Michigan's Medicaid Home Help program, the State's largest home and community services program, was largely consumer-directed. About 85 percent of beneficiaries hired and fired their workers directly. The Michigan Family Independence Agency served as the fiscal agent for beneficiaries who hired their own workers. Stakeholders noted that under this arrangement, consumers did not have to file tax statements, which could be a major barrier to participation.

Most Washington participants in the Medicaid personal care and waiver programs could choose between using licensed home care agencies or independent providers. The proportion of in-home care clients using independent providers had grown steadily and, at the time of the site visit, constituted a clear majority of beneficiaries receiving home care. In Washington, a State policy requirement that participants who needed more than 112 hours of service a month had to use independent providers rather than agencies, heavily influenced the use of consumer-directed care. By 1999, more than one-third of participants were authorized for more than 112 hours of service a month. Devised principally as a cost-containment mechanism, this requirement for heavy care users to rely on independent providers helped keep in-home per person expenditures below the State-imposed maximum of 90 percent of the average cost of nursing facility care.

The issue of consumer direction has been controversial. Consumer advocates in most States argued that it is a way to give Medicaid beneficiaries more control over their lives, more flexible services, and care tailored to their needs. On the other hand, HHAs often saw consumer direction as being a major risk for vulnerable clients, particularly those with cognitive impairment, who received services from relatively untrained, potentially abusive or neglectful workers. State officials had mixed views, with those in States with little consumer direction generally having a more protective attitude toward beneficiaries than those officials in States with consumer direction. The latter group asserted that most program participants could handle worker management tasks, although some officials expressed concern about those with cognitive impairment.

Cost Containment

All of the study States face the challenge of controlling home and community-based services spending in the face of an aging population and increased demand for services. All of the State officials expressed concern about cost containment for home and community-based services, especially those in Washington and Wisconsin, where these services were promoted as a way of saving money. Possible runaway expenditures, as a result of large increases in demand due to the large number of disabled persons in the community who do not receive any paid services, have often been a concern at the Federal and State level. State officials were very cognizant of the Federal cost-containment requirements for Medicaid home and community services waivers (e.g., average per capita expenditures must not exceed the estimated average per capita cost of services in an institution) and had systems in place to make sure that they met those requirements. For home health care and personal care services, States controlled expenditures by limits on benefits, low payment rates, and restrictive financial eligibility.

Despite concerns about controlling expenditures, officials in the case-study States focused more on expanding services and the number of people served than on saving money or in making sure that each individual served would actually be in a nursing home in the absence of non-institutional services. For example, as previously noted, no State used eligibility criteria for waivers more stringent than meeting the nursing facility or other institutional level of care, even though many severely disabled persons lived in the community and would never enter a nursing home. Moreover, no State official felt that spending for its home and community-based services programs was out of control. In addition, they did not feel under pressure from the Federal Government to pursue cost savings, a change from the 1980s when the Federal Government had strict cost-effectiveness requirements for waivers.

In all but a few States, officials did not perceive a direct financial tradeoff between funding institutional and non-institutional LTC services. With the exception of Washington and Wisconsin, States made funding decisions for each service separately. In part as a response to State ballot initiatives that imposed an overall cap on State spending, Washington focused on reducing use of institutions, including identifying people in nursing homes who could be served in the community, as a way of freeing up money to expand home and community-based services. In contrast, Wisconsin did not have a major initiative to find people in nursing homes who could live in the community, arguing that it was preferable to concentrate on preventing institutionalization by expanding home and community-based services. Elderly and disability advocates in Wisconsin repeatedly argued that money spent on nursing homes is money that is not available for community services. In fact, consumer advocates welcomed the repeal of the Boren Amendment, which set minimum Federal standards for Medicaid nursing home reimbursement, as a way of obtaining additional resources for home care. Although not a factor in the past, the administration in Kentucky said that additional funding for home and community-based services must come out of reduced institutional spending.

Case-study States controlled expenditures for home and community services through a variety of mechanisms, including the structure of the financing system, service coverage, waiting lists, caps on the average cost per beneficiary, limits on payment rates, and other strategies.

Financing Structure

The financing structure for home and community-based services served as the primary mechanism for limiting expenditures. All State-funded programs operated as appropriated programs without an entitlement to services, limiting expenditures to whatever level had been budgeted by the legislature and governor. Moreover, the State-chosen limit on the number of Medicaid waiver placements, combined with the federally imposed ceiling on average expenditure per person, provided an absolute limit to the State's financial liability for Medicaid home and community-based services waivers. In Wisconsin, the State allocated counties a fixed amount of Medicaid waiver and State-only funds, rather than a specific number of placements. Thus, the number of clients served in a county depended largely on average cost per client. Some counties spent more than their allocation of waiver funds and paid the State Medicaid share in order to draw down more Federal funds. In contrast to the waivers, Medicaid home health care and the optional personal care benefit were open-ended entitlements, generally thought to be less controllable, but not believed to be increasing at unacceptable rates. The narrowness of the benefits was believed to be a major factor in controlling expenditures.

Beyond budgeting, States were beginning to experiment with capitation as a way of making costs more predictable and shifting risk to providers. In its Medicaid home and community-based services waiver, Michigan paid “waiver agents,” which included area agencies on aging, private non-profit organizations, and other entities, a daily capitation payment that covered both administrative tasks (including care management) and services. Michigan placed waiver agents at financial risk for expenditures that exceeded their payment. Several Michigan stakeholders asserted that some waiver agents treated the service payment amount as an individual rather than aggregate ceiling and referred people with service needs exceeding this amount to the Medicaid personal care program—a practice prohibited by the State. In Wisconsin's Family Care demonstration, care management organizations received a fixed capitation payment to cover all institutional and home and community-based LTC services funded by the Federal and State governments (except Medicare). The State based the monthly per person payment amount on average costs of people at two functional levels. Stakeholders noted difficulties during the development of the capitation rates and expressed concerns that the capitation rate would freeze existing inequalities across counties. By combining both institutional and non-institutional expenditures into a single payment, Wisconsin hopes to provide financial incentives to keep individuals in the community.

Coverage and Limitations on Services

States partly controlled expenditures by limiting the amount and type of services covered. For example, Alabama and Indiana did not cover Medicaid personal care services outside of their home and community-based services waivers. Within covered services, States also limited the number of visits and often required prior authorization of services. For example, Alabama limited use of Medicaid home health care to 104 visits a year, with skilled nursing and home health aide visits counted separately. Conversely, Kentucky took a broad approach to Medicaid home health care and used the benefit to provide a substantial amount of personal care services.

Although lack of coverage of some services and restrictions on their use served to limit expenditures, State officials viewed coverage of independent workers and group residential settings in Washington, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Maryland as a way to control overall LTC costs by using lower cost providers. Although States justified coverage of independent workers on policy grounds of consumer empowerment, consumer-directed services cost far less (generally about one-half) than agency-provided services. This is because of the lack of agency overhead costs, generally lower wages, and the provision of few, if any, fringe benefits. Home care agencies insisted that the cost comparisons between the two types of care must be done cautiously because they believed that independent providers require a great deal more time and attention from case managers than do agency providers, thus shifting rather than eliminating some of the overhead costs. Similarly, although expensive in an absolute sense, coverage of non-medical residential services provided 24-hour supervised care at a cost well below that of nursing home care.

Waiting Lists

Both State-funded and waiver programs did not operate as open-ended entitlements. As a result, when demand exceeded funding, States established waiting lists. Thus, high levels of demand did not necessarily result in high levels of expenditures. Of the study States, Alabama, Wisconsin, Maryland, and Indiana had waiting lists for Medicaid home and community services waivers for older people or younger adults with physical disabilities. In addition, waiting lists for State-funded programs existed in Maryland, Indiana, Kentucky, and Wisconsin. Limitations on State funding for home and community-based services, rather than a shortage of federally approved placements, resulted in waiting lists. In contrast to the 1980s, when the Federal Government tightly controlled and limited the number of waiver placements, no State reported a problem gaining approval for additional waiver placements if they wanted them. Indeed, Alabama and Indiana had approved Medicaid waiver placements that were not funded.

Although waiting lists effectively controlled spending, they were politically controversial in every State that had them, resulting in pressure for additional funding. To lessen the negative connotation, Alabama referred to its waiting lists as “active referral lists.” Wisconsin planned to centralize its large and contentious county wait lists into a State-level list so that more accurate lists could be kept (e.g., people who died or entered a nursing home would be removed from the list). Because waiting lists that do not move at a reasonable pace could be a “red flag” under the U.S. Supreme Court's Olmstead decision as an indicator of possible discrimination against people with disabilities, States expressed concerns about the legal implications of these lists. Waiting lists were particularly a problem for programs and waivers for younger people with disabilities because there was little participant turnover. Younger clients tended to stay on the program for very long periods of time (especially compared with older people who died or entered a nursing home after a few years), so that taking younger people off waiting lists usually required program expansion.

Limits on Costs per Beneficiary Served

In addition to controlling the number of clients, States also limited costs per beneficiary. States often limited their costs by focusing on statewide averages rather than establishing individual caps on spending. Medicaid home and community-based waiver services programs, in particular, limited average or individual costs per beneficiary in response to Federal regulations that explicitly limit average Medicaid expenditures per beneficiary to no greater than the average Medicaid institutional cost per beneficiary. Some State-funded programs also limited average costs to less than that of nursing home care. Only a few of the study States (Washington and Alabama) placed “hard” caps on individual expenditures for their Medicaid home and community-based services programs, setting the limits at the Medicaid cost of nursing home care or slightly less.

Instead of individual caps, States generally monitored the statewide or countywide average cost per Medicaid waiver beneficiary State officials often used the much lower average Medicaid waiver costs relative to the cost of institutional care to show that the program saved money. For example, in fiscal year 1999, Alabama's average Medicaid costs per person for its aged and disabled waiver totaled $6,612 per year, compared with $22,771 per year for nursing facility care. In Wisconsin, with no hard cap on individual expenditures, some people used far beyond the average cost of nursing home care, but the State held the counties to specified averages, and high-cost individuals generally needed to be counterbalanced by persons who cost less. Counties could, however, request a State waiver, which was almost always granted. Michigan had a similar exception process, although stakeholders contended that approvals were hard to obtain.

Beyond just setting maximum costs, States actively monitored and reviewed average and sometimes individual expenditure levels, especially for high-cost beneficiaries. Washington relied on a fairly hard individual cap of 90 percent of the cost of Medicaid nursing home care, but State officials said that they budgeted the program at 40 percent of the average cost of nursing home care and monitored it strictly to make sure they stayed within budget. In Indiana, Medicaid program staff received weekly reports on service plans, reviewed them based on benchmarks for plan costs, and discussed them with area agency on aging staff if the care plans seemed overly expensive. The State asked area agencies to re-evaluate high-cost plans to determine if costs could be reduced, but the State did not impose an absolute cap on the cost of an individual beneficiary's services.

Provider Payment Levels

In almost all States, stakeholders raised low payment rates for home and community-based services as an issue with implications for the ability to recruit and retain workers. A common observation was that workers could obtain higher wages and benefits working for fast food restaurants. As with nursing homes, the Federal Government does not set minimum standards for payment rates for Medicaid home and community-based services. For example, Alabama Medicaid home health payment rates had not increased more than marginally since the late 1980s.

Not surprisingly, payment rates varied by service and funding source. For example, Kentucky paid HHAs up to 130 percent of the median costs for Medicaid services, but the State-funded Personal Care Attendant Program for Physically Disabled Adults generally paid the minimum wage for individual workers. In a choice between covering more beneficiaries and raising rates, States generally chose to cover more beneficiaries.

Other Cost-Containment Mechanisms

Finally, States used a variety of other cost-containment mechanisms that played a more minor role in holding down expenditures. For example, States typically required HHAs to bill Medicare rather than Medicaid if at all possible. This was a source of tension with providers in Wisconsin, where agencies reportedly struggled to respond to extensive audits and mandates to bill Medicare first. HHAs contended that this requirement subjected agencies to Medicare penalties, levied if an agency submitted too many inappropriate claims. Wisconsin providers also complained that retrospective home health care payment audits sometimes came after Medicare's window for billing had closed.

In addition, some States (Washington and Wisconsin) extended Federal requirements for Medicaid estate recovery for users of Medicaid home and community-based services to include State-funded programs. Finally, a few of the study States (Kentucky and Indiana) used competitive bidding for their State-funded programs to obtain the lowest possible prices for services.

Quality Assurance

As the States expanded home and community-based services, quality assurance gained increasing attention, but most States had fairly modest quality assurance activities, especially outside of the Medicaid home and community-based services waivers. Although the push toward home and community-based services is based on the premise that quality of care is better outside of institutions, States collect relatively little data to either support or refute this claim. The physically dispersed location of home care clients and the lack of quality measures made quality assurance difficult. States also found it difficult to hold providers accountable for adverse outcomes because the home care workers and agencies only spent a limited amount of time in a consumer's home.

In contrast with the detailed regulation of nursing homes required by Federal law for those facilities participating in Medicaid, States do not heavily regulate home and community services, often relying on more informal mechanisms. To provide Medicaid home health services, agencies must meet Medicare certification standards, but health home care agencies and individual workers providing personal care face relatively little regulation. For example, in Indiana and Michigan, home care agencies provided personal care services without being subject to any regulation, and Kentucky subjected home care agencies to less regulation than HHAs. Washington proved the exception because it required licensing for all home health care and home care agencies. In some of the case-study States (Michigan and Wisconsin), State-funded programs used the same quality assurance programs as those of the waiver programs, but other States had less intense quality assurance mechanisms.

Case managers played a key role for quality assurance in all programs. In addition to developing service plans and arranging for and ensuring that providers delivered services, States relied on case managers to monitor the quality of services, respond to complaints, and take action when necessary.

Most of the case-study States had minimal entry-level training requirements for paraprofessional workers and some level of criminal background check to weed out potentially abusive providers. The lack of extensive training requirements raised some concern that independent providers, in particular, did not receive enough training. Washington had the strictest requirements regarding worker training by requiring all workers to complete 22 hours of training, pass both written and hands-on competency tests, and participate in 10 hours of continuing education annually.

Providers delivering services to Medicaid waiver beneficiaries received more oversight than other home and community services programs. Waiver beneficiaries generally had regular contact with case managers; a sample received home visits periodically; and some States (Alabama, Wisconsin, and Indiana) conducted consumer satisfaction surveys of some sort. In Indiana, for example, each area agency on aging fielded a computerized, in-home consumer satisfaction survey with a random sample of at least 10 percent of waiver beneficiaries, with some area agencies on aging including all beneficiaries. The survey involved area agency on aging staff going into beneficiaries' homes and asking a series of questions related to worker skills, timeliness, and continuity, and case managers' treatment of beneficiaries. The area agencies provided the aggregated survey results to the provider agencies and their own staff. Other States depend on mailed surveys, which had low response rates.

Michigan sought to assure quality of waiver services by entering into contracts with multiple, competing “waiver agents” in each region of the State. The State built in competition to ensure that waiver agents had sufficient capacity to serve beneficiaries. The State required agents to do onsite monitoring of providers and to conduct audits and special studies in their areas. Michigan also used its computerized data system to develop and test clinical indicators of home and community services quality for various subpopulations with disability.

In the consumer-directed programs, States considered the consumer who hired and fired the worker to be responsible for a large component of quality assurance. The fact that many independent providers were family members made State officials less concerned about abuse, but it also meant that these independent providers tended to have low levels of formal training. Some stakeholders indicated concern that the tight labor supply and the heavy use of family caregivers could inhibit the ability of dissatisfied clients to fire their workers.

Regulation of group residential settings varied markedly across the case-study States, and standards for different settings varied within the States. All States, except Michigan, regulated assisted living facilities to some degree, and all States licensed group homes. As previously discussed, States struggled to find ways to let people age in place and bring disabled persons the additional services they may need without making these facilities into unlicensed and perhaps substandard nursing homes. In Washington, stakeholders noted that quality of care in residential facilities had been the subject of intensive media scrutiny.

Observations about the regulatory structure fell into several categories. State officials generally believed that the regulatory systems worked well and that home care providers delivered good care in most cases. Provider groups complained about what they perceived to be inequitable treatment across providers. HHA representatives generally believed that they were subjected to too much regulation compared with non-skilled home care agencies or individual workers; nursing home representatives often complained of an overly strict regulatory structure compared with that applied to assisted living facilities. Provider groups receiving the stricter scrutiny wanted equity in regulatory oversight when delivering similar services. For example, several HHA representatives wanted anyone delivering paid personal care services to be subject to the same training and supervisory requirements. In general, disability groups rejected the notion that oversight was inadequate and argued that most existing quality assurance regulations for home care agencies emphasized paperwork that had little to do with quality.

State interviewees said they faced a labor shortage for all LTC providers, and people in some States described the situation as a crisis. Stakeholders attributed the shortages to low wages and few benefits for workers, as well as heavy workloads. They also said that the degree of the shortage varied according to a locality's unemployment rate; localities with very low unemployment rates, such as in Wisconsin, had more trouble with worker shortages. According to stakeholders, workers sometimes did not show up to provide services, and agencies did not have sufficient backup in case of emergencies.

Issues for the Future