Introduction

The 1990s saw the emergence of managed care into the Medicare marketplace. In the beginning of the decade nearly all beneficiaries were in the Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) program. In 1991 there were only 1 million Medicare risk health maintenance organization (HMO) members accounting for a little over 3 percent of the Medicare population. By 1999 there were over 6 million Medicare risk HMO members—a nearly 500-percent increase from 1991—comprising 17 percent of the Medicare population.

As managed care membership increased, there was a contraction in the number of beneficiaries with traditional individually purchased medigap1 plans. The number of beneficiaries with private medigap plans declined by 2 million, or 20 percent, between 1991 and 1999. These plans, which provided supplemental insurance for 30 percent of Medicare beneficiaries in 1991, covered only 21 percent of beneficiaries in 1999. A large number of beneficiaries who left medigap plans switched to Medicare risk HMOs.

Enrollment in employer-sponsored supplemental plans increased slightly in the beginning of the decade, peaking in 1994 at 11.5 million beneficiaries holding these supplemental plans, and has since declined. As a result, employer-sponsored supplemental plans covered 33 percent of the Medicare population in 1999 versus 36 percent in 1991.

The number of beneficiaries that were not enrolled in a Medicare risk HMO plan and were also without supplemental insurance declined slightly from 13 percent of the Medicare population in 1991 to 11 percent in 1999.

Data

Data from this article are from the Medicare Current Beneficiary survey (MCBS) Access to Care Files from 1991 to 1999. The MCBS is a continuous multi-purpose survey of a representative sample of the entire Medicare population. The Access to Care File is based on a sample of about 16,000 beneficiaries. The weighting method used for this sample makes the population representative of beneficiaries who were enrolled in Medicare for all 12 months of the year, regardless of living arrangement. Health insurance status is based on the beneficiary's insurance holdings on the day they were interviewed. Beneficiaries were classified into discrete insurance categories based on the following hierarchy: Medicare risk HMO, Medicaid, employer sponsored, medigap, other, and FFS only. Thus, if a beneficiary was in a Medicare risk HMO but also had an employer-sponsored supplemental plan they would be categorized as a risk HMO member and not included in the employer-sponsored category.

Disabled Versus Aged Beneficiaries

The number of beneficiaries eligible for Medicare benefits due to a disability increased by 60 percent between 1991 and 1999 while the aged population increased by about 8 percent (Table 1). The disabled population and the aged population had significantly different supplemental insurance patterns but still shared some common trends over the decade. Both groups had large increases in risk HMO member ship—nearly 500 percent growth for the aged and almost 800 percent growth for the disabled—and by 1999 risk HMOs covered 18 percent of the aged population and only 9 percent of the disabled population.

Table 1. Community Dwelling Medicare Beneficiaries, by Insurance Status: 1991 and 1999.

| Insurance Status | Aged | Disabled | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1991 | 1999 | Percent Change | 1991 | 1999 | Percent Change | |

| Total | 29,351,090 | 31,624,545 | 8 | 2,904,327 | 4,739,137 | 63 |

| Medicare Risk Health Maintenance Organization | 1,020,049 | 5,841,087 | 473 | 48,138 | 426,292 | 786 |

| Employer-Sponsored Plans | 11,034,860 | 11,232,863 | 2 | 614,747 | 936,565 | 52 |

| Medigap | 9,420,172 | 7,490,018 | -20 | 239,459 | 224,053 | -6 |

| Medicaid | 3,358,619 | 3,491,195 | 4 | 1,057,896 | 1,889,632 | 79 |

| Fee-for-Service Only | 3,356,439 | 2,803,535 | -16 | 873,559 | 1,113,392 | 27 |

| Other | 565,569 | 418,148 | -26 | 56,359 | 131,052 | 133 |

SOURCE: Centers for Medcare & Medicaid Services: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Access to Care Files, 1991-1999.

While the large increase in the number of disabled beneficiaries resulted in an increase in the number of disabled beneficiaries with Medicare FFS coverage only, the proportion of disabled beneficiaries with no supplemental private insurance declined by almost 7 percentage points to 23 percent. The proportion of aged beneficiaries with Medicare FFS only coverage declined in both absolute numbers and as a proportion of the population.

In 1999, 40 percent of the disabled population (2 million beneficiaries) received Medicaid assistance, up from 36 percent in 1991. The percent of aged beneficiaries who received Medicaid assistance rose slightly in the mid-1990s but by 1999 was 11 percent—nearly the same as in 1991. Very few disabled beneficiaries received supplemental insurance through an individually purchased plan; 8 percent in 1991, and 5 percent in 1999.

Aged Population

Medicare Risk HMOs

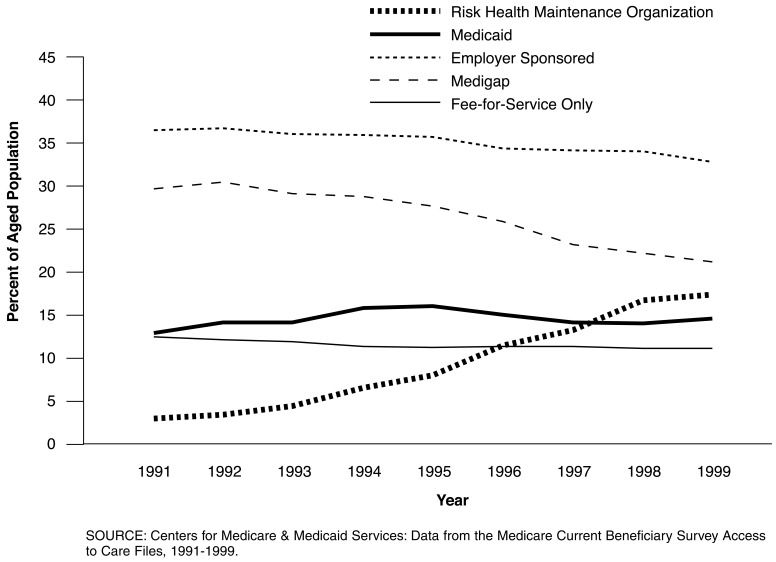

Medicare risk HMOs were the fastest growing insurance group in the 1990s (Figure 1). These plans, which usually offered coverage of preventive services, prescription drugs, and some optical and dental services with no additional premium were attractive to many beneficiaries. Forty percent of Medicare risk HMO members cited lower costs as their main reason for joining an HMO while 22 percent cited better benefits as their main reason.

Figure 1. Supplemental Insurance for Medicare Beneficiaries Age 65 or Over, 1991-1999.

Over one-third of beneficiaries switching into Medicare risk HMOs previously had a traditional medigap plan and a little over one-quarter had employer-sponsored supplemental plans. Twenty-two percent of beneficiaries leaving FFS coverage and moving into managed care plans had no previous private supplemental insurance (Medicare FFS only). While newer Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in HMOs at a slightly higher rate (19 percent of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare for less than 5 years were HMO members in 1999 versus 14 percent of beneficiaries who had been in the program for over 15 years), most risk HMO members had been in the Medicare program for at least 5 years (74 percent). The majority of risk HMO members were also fairly new to managed care. In 1999 two-thirds of risk HMO members had been enrolled in an HMO for less than 5 years.

While risk HMO enrollment grew during the entire decade, the largest increases occurred between 1996 and 1998 when nearly 1 million Medicare beneficiaries switched to risk HMOs annually. This also coincides with the peak in the number of risk HMO plans available. The number of risk HMO plans from which beneficiaries could choose grew from 93 plans in 1991 to 346 plans in 1998. (By 2000 the number of plans available had dropped to 300.2) In 1995 (the first year that these figures were available through the MCBS) nearly 65 percent of beneficiaries had at least one risk HMO plan in their area and 44 percent had at least three plans. By 1999, 78 percent of beneficiaries had at least one risk HMO in their area and 61 percent had three or more plans. Membership in risk HMOs is especially high in areas with a large number of plans available. In 1999 only 8 percent of Medicare beneficiaries living in areas with one or two risk HMOs belonged to one of those plans. By contrast, 31 percent of beneficiaries living in areas with nine or more risk HMO plans belonged to an HMO. These large HMO markets (with nine or more plans in an area) accounted for 57 percent of all Medicare risk HMO membership in 1999. Seventy-eight percent of all risk HMO members lived in areas with five or more plans available in 1999.

During the 1990s nearly all risk HMO plans offered additional services not covered by traditional FFS Medicare. One of the most attractive benefits was prescription drug coverage. In 1997, 96 percent of beneficiaries in a risk HMO reported having prescription drug coverage—the highest coverage rate of any supplemental insurance category. This benefit was especially important to many beneficiaries as the number of new drug therapies available increased during the 1990s. Prescription drug use by beneficiaries' rose significantly in the 1990s and by 1998 beneficiaries with drug coverage filled an average of 24 prescriptions.3

Another factor contributing to increased HMO enrollment may be a push from employers to have their retirees move into risk HMO plans (McArdle and Yamamoto, 1997). Seven percent of beneficiaries in risk HMOs cited the fact that their employer or their spouse's employer paid their premium as their main reason for joining an HMO.

The majority of beneficiaries who join risk HMOs remain in managed care. Following beneficiaries who were enrolled in a Medicare HMO in December 1995, only 5 percent (less than 150,000) had moved back into the FFS program by December 1998. Over 2.5 million beneficiaries who were enrolled in Medicare FFS in December 1995 had moved to a risk HMO by December 1998 (8 percent of the FFS population).

However, recent reports indicate that risk HMO coverage may be deteriorating. In 2000 fewer risk HMO plans offered coverage with no additional premium, many plans trimmed their benefit packages, and more plans introduced or lowered caps on prescription drug benefits (Gold, 2000).

Medigap

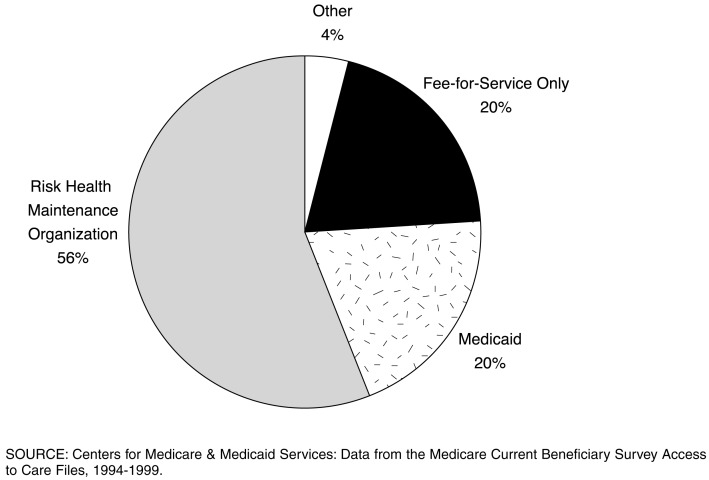

The number of beneficiaries with individually purchased supplemental plans declined dramatically in the mid to late 1990s. The number of beneficiaries with Medigap plans peaked at 11 million in 1994. By 1999 only 8 million beneficiaries had a medigap plan, a decline of 28 percent. Between 1994 and 1999, 56 percent of the beneficiaries that left medigap plans went to a risk HMO (Figure 2). An additional 21 percent entered the Medicaid program. These beneficiaries may have qualified for Medicaid under the federally legislated qualified Medicare beneficiary program or specified low-income Medicare beneficiary program passed in the 1990s.

Figure 2. Destination of Beneficiaries Leaving Medigap: 1995-1999.

Medigap premiums increased substantially in the 1990s and by 1998, the annual average premium for medigap Plan C, the most common plan purchased by beneficiaries, was $1,065 (Weiss Ratings, 2001). Most medigap plans do not offer prescription drug coverage and those that do cover prescription drugs have high premiums, a $250 deductible, a 50-percent coinsurance payment and relatively low caps on benefits (either $1,250 or $3,000 depending on the plan) (Scanlon, 2001). Plan J, which includes prescription drug coverage and preventive services had an average national premium of $2,408 in 1998 (Weiss Ratings, 2001). Medigap premiums also varied dramatically from area to area and across different insurers, with premiums running as high as $6,000 in some areas. The majority of Medicare HMOs during the same time period offered preventive services, prescription drugs, and vision benefits with no additional premiums and copayments on doctor's visits of $10 or less. While the percent of beneficiaries with prescription drug coverage through their medigap plan appears to rise in the mid- to late 1990s it is at least, in part, due to beneficiaries without drug coverage leaving medigap.

Perhaps due to the unavailability of Medicare HMOs in non-metropolitan areas, 33 percent of beneficiaries living in these areas had supplemental coverage through a medigap plan, versus only 19 percent of beneficiaries in metropolitan areas. Beneficiaries with incomes from $10,000 to $25,000 were also more likely to have a medigap plan than beneficiaries with incomes under $10,000 (many of whom qualify for Medicaid) or over $25,000 (many of whom have employer-sponsored plans). Older beneficiaries (age 75 or over) had medigap plans at slightly higher rates than those under age 75.

Employer-Sponsored Private Insurance

As with medigap plans, enrollment in employer-sponsored supplemental plans for the aged population peaked in 1994 at 11.5 million beneficiaries. Unlike the medigap market, however, the number of beneficiaries with these types of plans has declined by a rather modest 3 percent since then.

Employer-sponsored plans still cover over one-third of the Medicare population. Employer-sponsored plans are, not surprisingly, correlated with higher incomes. They are more likely to be held by younger (age 65–74) and more affluent beneficiaries. Nearly one-half of beneficiaries with incomes over $45,000 per year have an employer-sponsored plan versus less than 20 percent of those with incomes under $15,000. Employer-sponsored plans are also less likely to be held by minorities—only 20 percent of black and 15 percent of Hispanic beneficiaries hold an employer-sponsored plan versus 32 percent of white beneficiaries

While employer-sponsored supplemental plans have traditionally been fairly generous—offering low premiums and copayments, and covering a large portion of beneficiaries' prescription drug costs, some recent reports indicate that employers may not be as generous in the future. Only 17 percent of employers polled in a study sponsored by the Kaiser Family Foundation said that they would consider adding or improving retiree medical coverage for retirees age 65 or over. Eighty-one percent said that they would consider increasing the retiree premiums and/or cost sharing. Slightly over one-half of employers said they would consider shifting to a defined contribution approach and let retirees purchase their own private coverage (McArdle et al., 1999).

Medicaid

The number of aged beneficiaries that received Medicaid benefits increased by 10 percent between 1991 and 1999 to about 3.8 million. The qualified Medicare beneficiary and specified low-income Medicare beneficiary programs legislated in the 1990s created new ways for Medicare beneficiaries to qualify for Medicaid assistance. Despite this broadening of the scope of Medicaid, dual enrollment did not increase dramatically.

Discussion

Since the MCBS began collecting data in 1991 there has been a dramatic shift in the distribution of private supplemental insurance for Medicare beneficiaries. Many beneficiaries entered into Medicare managed care plans in order to reduce their out-of-pocket expenses and receive more benefits. Medigap plans lost a large number of beneficiaries as premiums increased during the decade and prescription drug coverage became a priority for many beneficiaries. Beneficiaries in non-metropolitan areas were left with little or no choice in the new managed care boom, as plans were not offered in their areas.

In the new decade there will likely be major shifts again. Risk HMO plans appear to be cutting back on their benefits and several have left the Medicare market altogether. However, whether Medicare HMOs are retreating or just regrouping is yet to be seen. In 1999 three-quarters of beneficiaries in Medicare risk HMOs had no supplemental insurance in addition to their HMO leaving them more vulnerable to plan drop-outs. Employer-sponsored plans, which provide coverage to one-third of beneficiaries, may also begin limiting benefits and passing on higher costs to retirees. Even larger changes may occur if, in fact, the Medicare program is restructured, as many believe is inevitable.

The MCBS, with its collection of information on all medical services received by beneficiaries and the sources of payments for those services will be poised to help policymakers gauge the effect of program changes on beneficiaries.

Footnotes

The authors are with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CMS.

While some employer-sponsored supplemental insurance plans are referred to as medigap plans, for the purpose of brevity all references to medigap plans in this article are strictly referring to individually purchased supplemental insurance plans.

All data are as of December of the year indicated. Data for 1999 and 2000 are adjusted to account for plan consolidations, so the number of plans cited in this study will be higher than administrative data indicate.

Poisal and Murray (2001) provide additional information on prescription drug coverage.

Reprint Requests: Lauren A. Murray, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 7500 Security Boulevard, C3-17-07, Baltimore, MD 21244-1850. E-mail: lmurray@cms.hhs.gov

References

- Gold M. Trends Reflect Fewer Choice, Monitoring Medicare + Choice. Mathematica Policy Research Inc.; Washington DC.: Sep, 2000. Fast Facts #4. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle FB, Coppock S, Yamamoto DH, Zebrak A. Retiree Health Coverage: Recent Trends and Employer Perspectives on Future Benefits. Hewit Associates; Washington DC.: Oct, 1999. Report prepared for Kaiser Medicare Policy Project. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle FB, Yamamoto DH. Retiree Health Trends and Implications of Possible Medicare Reforms. Hewitt Associates; Washington, DC.: Sep, 1997. Report prepared for Kaiser Medicare Policy Project. [Google Scholar]

- Poisal J, Murray LA. Growing Differences Between Medicare Beneficiaries With and Without Drug Coverage. Health Affairs. 2001;20(2):74–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon WJ. Cost-Sharing Policies Problematic for Beneficiaries and Program. Washington DC.: May 9, 2001. Statement before the Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Ratings. Palm Beach Gardens, Florida: Mar 26, 2001a. Prescription Drug Costs Boost Medigap Premiums Dramatically. Internet address: www.weissratings.com/NewsReleases/Ins_Medigap/20010326Medigap.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Ratings. Palm Beach Gardens, Florida: Jun 11, 2001b. Medigap Prices Vary Dramatically Despite Standard Plans. Internet address: www.weis-sratings.com/NewsReleases/Ins_Medigap/20010326Medigap.htm. [Google Scholar]