Abstract

Using both employer- and beneficiary-level data, we examined trends in employer-sponsored retiree health insurance and prospects for future coverage. We found that retiree health insurance has become less prevalent over the past decade, with firms reporting declines in the availability of coverage, and Medicare-eligible retirees reporting lower rates of enrollment. The future of retiree health insurance is uncertain. The forces discouraging its growth—rising premium costs, a slower economy, judicial challenges, and an uncertain Medicare+Choice (M+C) program and policy agenda—far outweigh the forces likely to encourage expansion.

Introduction

Former employers are a major source of health insurance for older adults, particularly for those who retire before becoming eligible for Medicare. To early retirees, defined as those who retire before age 65, health insurance coverage is a critical consideration in the decision of when to retire (Rogowski and Karoly, 2000). To Medicare-eligible retirees, defined as those age 65 or over, post-retirement health insurance generally provides financial protection for medical expenses not covered by the Medicare program, for example, prescription drugs, as well as cost-sharing liabilities, such as deductibles and coinsurance.

Post-retirement health benefits are also significant to employers and the Medicare program. Although retiree health coverage is a major financial investment for employers, it is quite influential in recruiting and retaining employees, particularly those in mid- and late-career (Anderson et al., 2001). For the Medicare program, post-retirement health coverage from former employers substantially affects Medicare spending. Medicare outlays for beneficiaries with post-retirement benefits are 23 percent greater than spending on beneficiaries in equivalent health and socio-economic status who lack supplemental coverage (Khandker and McCormack, 1999). Therefore, policymakers must understand how the public and private insurance systems can interact, and how changes in the Medicare program, such as the potential addition of a Medicare prescription drug benefit, might affect employers and ultimately beneficiaries. With a better understanding of the retiree insurance market, policymakers can make more informed decisions about ways to improve the Medicare program.

Failure to understand trends in post-retirement health benefits can lead to costly policy miscalculations. There is no clearer example than the Medicare Catastrophic Act, passed overwhelmingly by bipartisan majorities in 1988. In passing this legislation, Congress misunderstood that more than one-third of the elderly already received catastrophic and prescription drug coverage through their employer at a lower cost than provided by the legislation. Those elderly with post-retirement benefits included many of the most affluent, politically active, and articulate elderly. One year later an embarrassed Congress repealed the act (Rice, Desmond, and Gabel, 1990).

This article presents recent trends in employment-based supplemental health insurance coverage for older adults and prospects for the future availability of such coverage given the current policy environment. We undertook employer- and beneficiary-level analyses of cost and coverage issues. Specifically, we addressed the following research questions:

To what extent are employers offering retiree health benefits and how has this practice changed over time?

Which subgroups of older adults are more likely to have retiree health benefits and other types of Medicare-related insurance?

In what types of health plans are retirees enrolled?

How prevalent is employer-based prescription drug coverage for retirees?

What are employers currently doing to save costs, and what changes do they have planned for the future?

Background

Medicare supplemental health insurance became available almost immediately after the inception of the Medicare program in 1965. Supplemental coverage is highly desirable because Medicare pays for only about 55 percent of all personal health care expenditures, leaving the beneficiary to pay the balance (Liu et al., 2000). Sole reliance on Medicare can impose high costs on the elderly because there is no limit on out-of-pocket spending. Supplemental policies typically take the following forms: employer-sponsored retiree (group) coverage; individually purchased private supplemental insurance policies; or publicly sponsored coverage, most commonly Medicaid. Insurance under any of these categories may be provided under managed care arrangements, most notably through the M+C program.

For years, retirees have generally secured employer-sponsored and individually purchased private supplemental insurance in about equal proportions, with employment-based coverage slightly exceeding individual coverage (Eppig and Chulis, 1997). Employment-based retiree health benefits are, therefore, the leading source of supplemental coverage for Medicare beneficiaries and the primary source of coverage for early retirees who do not yet qualify for Medicare (Hewitt and Associates, 1999). Even with supplemental insurance, particularly medigap coverage, the financial burden can be high. In 1999, average annual out-of-pocket drug expenses were $570 for individuals with medigap policies (Rother, 1999). This amount is in addition to the annual medigap premium, which ranged from $766 for Plan A to $3,065 for Plan J in 2000, increasing an average of 15.5 percent over a 3-year period from 1998 to 2000 (Weiss Ratings Inc., 2001).

Employer-Sponsored Retiree Health Benefits

Various studies—using different samples, years of data, and methods—convey a similar message about the trends in the availability and comprehensiveness of employer-sponsored retiree health insurance over the past decade or so. Some differences exist, however, with respect to the exact level of coverage each year and changes in coverage over the past few years (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2001). It is difficult to directly compare the different studies for several reasons. Some studies examine trends among only large employers, while others look at firms of all sizes. Some studies report data for early and Medicare-eligible retirees separately, while others look at both groups combined. Some data sets only allow researchers to examine coverage held in an individual's own name, which is problematic because spouses frequently obtain coverage through each other's employer. Another key factor contributing to the complexity of the issue is that trends are often examined using panel data sets containing either some of the same employers or individuals over time, requiring that statistical methods be used to correct for the correlation between observations. It is not always clear whether or not this issue has been addressed. Finally, many of the leading surveys in the field have response rates in the range of 50 percent. All of these nuances must be carefully considered when comparing estimates.

The literature consistently indicates, however, that fewer employers now offer retiree health benefits compared to a decade ago (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2001; Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research and Educational Trust, 2000; Hewitt and Associates, 1999). Some employers that previously offered coverage have dropped it and fewer new companies are offering it, while others have reduced the extent of coverage. Two leading national employer surveys1 conflict about whether offer rates to retirees declined significantly between 1997 and 2000 among large employers, with one survey reporting a significant decline and the other reporting a steady-state (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2001). The Mercer survey breaks out retirees into those that are early versus Medicare-eligible, while Kaiser looks at retirees of all ages over the time period in that analysis. Mercer's survey reports that offer rates fell from 41 percent in 1997 to 36 percent in 2000 for early retirees, and from 35 percent in 1997 to 29 percent in 2000 for Medicare-eligible retirees (yet they do not indicate if the changes were statistically significant). Kaiser reports no statistically significant decline over this time period, but with some year-to-year fluctuation (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2001).

Analysis of the Current Population Survey by the Employee Benefits Research Institute show no statistically significant decline in percentage of retirees with employer-sponsored coverage between 1994 and 1999, with about 37 percent of early retirees covered and about 27 percent of Medicare-eligible retirees covered in 1999 (but these figures include only coverage held in a person's own name) (Employee Benefits Research Institute, 2001). Analysis using the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) shows statistically significant declines in the proportion of Medicare-eligible retirees with employer-sponsored coverage between 1992 and 1999 (Murray and Eppig, 2002).

Declines in coverage have been attributed to many factors: The rising cost of retiree health benefits; cyclical changes in the U.S. economy; statutory changes brought about by the passage of the Deficit and Economic Recovery Act of 1984 (which reduced the tax advantage of prefunding retiree benefits); and new accounting standards issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board.2 The standards, which were phased-in during the early to mid-1990s depending on the size of the employer (Gabel, Ginsburg, and Hunt, 1997), had a dramatic effect on corporate America's income statement, because they directed employers to include the present value of the costs of future retiree health benefits as a corporate liability (Employee Benefits Research Institute, 2001). However, the standards apply only to private sector firms; public sector organizations, which are a substantial provider of retiree health benefits, are exempt.

Managed Care and Retiree Health Benefits

Medicare managed care plans, many of which are now approved as M+C plans, offer retirees and employers an alternative to traditional indemnity retiree health benefits. For the retiree, M+C plans frequently offer additional benefits not covered by Medicare (Employee Benefits Research Institute, 1996). Every retiree enrolled in an M+C plan represents a decrease in the employers' SFAS 106 post-retirement medical liability. With M+C plans, employers traditionally pay lower premiums and thus have appealed to employers as a method of controlling rising retiree health costs. Use of M+C plans grew most rapidly between 1993 and 1996 (Hewitt and Associates, 1999). However, a significant number of M+C insurers pulled out of the Medicare market in the past few years for a variety of reasons (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2000), making them a less attractive option for employers (Fox, 2000).

Data Sources

This study used data from two secondary sources: (1) the Kaiser/HRET survey of human resource and benefits managers in public- and private-sector organizations and (2) the MCBS. Using these two data sets, we are able to characterize coverage from both the employer and the beneficiary perspective over a longitudinal period. We report data from the 1988, 1991, 1993, 1995, and 1997-2000 Kaiser/HRET surveys3 but focus primarily on the 2000 data. We report findings from the 1992 and 1995-1998 MCBS. When possible, comparisons are made between the two data sources. In addition, we also conducted 25 in-person and telephone key informant interviews with employers, insurers, and other industry representatives in summer 2001 to complement the survey data.

Employer-Level Data

Samples for the Kaiser/HRET survey are drawn from a Dun & Bradstreet list of the Nation's private and public employers with three or more employees, stratified by industry (10 categories) and the number of employees in the organization (6 categories) to increase precision. (The industry categories include mining, construction, manufacturing, transportation/communications/utilities, wholesale, retail, finance, service, State and local governments, and health care. The firm size categories of employees range from 3-9, 10-24, 25-199, 200-999, 1,000-4,999, and 5,000 or more. Each year, organizations are selected based on the stratification design of the survey. Two types of organizations are included: panel and non-panel firms. Panel firms are organizations that participated in the previous year's survey that were randomly selected for participation when they first entered the panel. Non-panel firms are randomly selected organizations from the Dun & Bradstreet list excluding the panel firms. The number of non-panel firms selected is determined based on the needs of the stratification design once the panel firms have been placed within that design. In 2000, Kaiser/HRET attempted to contact nearly 5,000 firms including 1,939 that were interviewed in 1999. In total, 1,887 firms participated in the 2000 survey; of those, 982 had participated in the 1999 survey.

Using computer-assisted telephone interviews, data were collected by National Research LLC, a Washington, DC-based survey research firm. National Research conducts the interviews between January and May each year. In 2000, as many as 400 questions were asked overall, of which about 30 focused on the each of the organization's health plans. The exact number of questions asked depended on the number and type of health plans the organization offers to its employees. These plans include conventional or indemnity, health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization, and point-of-service products. The average interview time was 26 minutes.

The overall response rate for the 2000 survey was 45 percent, down from 60 percent in 1999. Contributing to the declining response rate was the decision not to re-interview any organizations with 3-9 employees that participated in the 1999 survey because of concerns about the representativeness of this group over time. Re-interviewing past participants typically yields a better response rate for this survey than contacting firms for the first time. Comparisons made between respondents and non-respondents in 2000 revealed that larger firms (those with 200 or more employees) were more likely to respond to the survey than smaller firms (those with 3-199 employees) (54 versus 38 percent, respectively). Larger firms are also more likely to offer retiree health benefits than smaller firms (89 versus 11 percent), therefore, only a small percentage of retirees are from small firms. Firms in selected industries—construction, wholesale, retail, finance—were less likely to respond, while government and health care organizations were more likely to respond. Firms in the Northeast were less likely to respond, while firms in the Midwest, South, and West were more likely to respond. All of these differences were accounted for in the weighting process.

The limitation of a low response rate for the Kaiser/HRET survey is tempered through the use of statistical weights and a post-stratification adjustment that adjusts the size categories to reflect the universal distribution of firms. Three sets of weights were created, all of which account for the part-panel nature of the data—one set reflecting the total number of U.S. employers or firms (employer weight); second set reflecting the total number of employees (employee weight); and third set reflecting the total number of retirees and the number of Medicare-eligible retirees, where applicable (retiree weight). Table 1, which includes selected characteristics of the 2000 survey sample, show the effects of using different weights. Among the more than 5 million firms nationally, 72 percent employ 3-9 employees, therefore, the smallest organizations dominate any national statistics about employer-level activity. However, jumbo firms (defined as those with 5,000 or more employees) represent about 0.1 percent of firms, but employ about 42 percent of active employees. Therefore, jumbo firms dominate any employee- or retiree-weighted statistics because they employ the largest number of people. Despite the appropriate use of different statistical weights, year-to-year differences may have resulted from differences in those employers that chose to respond to the surveys.

Table 1. Employer Survey Sample, by Selected Characteristics: 2000.

| Characteristic | Sample Size | Using Employer Weight | Using Employee Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Sample Distribution | Weighted Sample | Weighted Sample | ||

|

| ||||

| Percent | ||||

| Overall | 1,887 | 5,058,537 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Firm Size1 | ||||

| Small (3–9) | 218 | 3,643,512 | 72.0 | 7.8 |

| Small (10–24) | 233 | 775,346 | 15.3 | 4.9 |

| Small (25–49) | 124 | 192,021 | 3.8 | 2.9 |

| Small (50–199) | 268 | 360,015 | 7.1 | 15.4 |

| Midsize (200–999) | 363 | 67,864 | 1.3 | 12.4 |

| Large (1,000–4,999) | 367 | 15,751 | 0.3 | 14.5 |

| Jumbo (5,000 or More) | 314 | 4,027 | 0.1 | 42.0 |

| Regional Location of Firm | ||||

| Northeast | 500 | 999,105 | 19.8 | 16.7 |

| Midwest | 482 | 1,131,293 | 22.4 | 22.3 |

| South | 605 | 1,778,397 | 35.2 | 41.7 |

| West | 300 | 1,149,742 | 22.7 | 19.3 |

| Industry Type | ||||

| Mining/Construction/Wholesale | 156 | 696,503 | 13.8 | 7.2 |

| Manufacturing | 268 | 380,608 | 7.5 | 13.6 |

| Transportation/Utilities/Communication | 93 | 73,946 | 1.5 | 17.5 |

| Retail | 181 | 929,466 | 18.4 | 13.5 |

| Finance | 104 | 215,337 | 4.3 | 6.9 |

| Service | 491 | 2,075,046 | 41.0 | 35.2 |

| State/Local Governments | 430 | 33,274 | 0.7 | 5.7 |

| Health Care | 164 | 654,356 | 12.9 | 10.3 |

| Employee Wage Level Per Year | ||||

| Less than 35 Percent Earn $20,000 or Less | 1,147 | 3,234,824 | 63.9 | 58.4 |

| 35 Percent or More Earn $20,000 or Less | 487 | 1,570,552 | 31.0 | 23.9 |

| Missing | 253 | 253,161 | 5.0 | 17.7 |

Reflects the total number of employees.

The part-panel nature of the data creates a potential limitation of the employer-level analysis for which we did not control. Some employers have observations in more than one year of the data, which may introduce correlation between the observations across years. Although the parameter estimates remain unbiased and consistent in this situation, the standard errors of the estimates are smaller than they should be, which may result in findings of statistical significance that are unwarranted.

Beneficiary-Level Data

The MCBS is a continuous, multipurpose survey of a representative national sample of the Medicare population, conducted by CMS. The survey ascertains information on all types of health insurance coverage and relates coverage to sources of payment. MCBS is unique in that it covers the entire Medicare population, including those living in the community or in an institution, and oversampling significant subpopulations, such as the very old. To provide a longitudinal picture, the MCBS re-interviews the same sample members over a 4-year period. Beneficiaries are sampled from Medicare enrollment files, and they or an appropriate proxy are interviewed three times a year using computer-assisted personal interviewing. The MCBS Access to Care File contains summaries of use and expenditures for the year from Medicare claims files along with self-reported data on insurance coverage, health status and functioning, access to care, information needs, satisfaction with care, and income. For this study, we used 5 years of MCBS Access to Care data—1992, 1995, 1996, 1997, and 1998. The 1992 data are critical because they predate changes imposed by SFAS 106 and allow us to observe coverage rates before and after the change.

Analytic Methods

We used descriptive statistics and multivariate modeling to analyze data from both surveys. Descriptive statistics include univariate and bivariate frequencies; chi-square or t-tests were employed to determine statistical significance. Trends are shown when possible, that is, when the same survey questions were asked over time. Because both surveys employed complex sampling designs, the data were analyzed using SUDAAN® software so that standard errors are corrected for the design effect and stratification. All data are weighted to represent national estimates. Significance testing was performed at the 0.05 alpha level.

Employer-Level Analyses

Using employer-level data, we examined the availability of retiree health insurance for both early and Medicare-eligible retirees (focusing on those of Medicare age), enrollment in different types of plans, coverage of prescription drugs, and recent and future contemplated plan changes. We explored differences in the survey responses primarily with respect to employer size, but in selected cases, by employer region, industry, and employee wage level. Employee wage is a firm-level dichotomous variable where more (or less) than 35 percent of employees earn $20,000 or less per year. We conducted significance testing both within and across years of the data. Significance testing was not conducted prior to 1997.

Beneficiary-Level Analyses

We examined enrollment in employer-sponsored and other Medicare-related insurance options and how this varied across time and beneficiary characteristics. The MCBS analysis includes only Medicare beneficiaries age 65 or over who were continually enrolled in Medicare for the entire year, that is, those who survived the entire year, including the institutionalized, non-institutionalized, disabled, and non-disabled populations. Thus, this segment of the article excludes early retirees.

We developed a five-category Medicare-related insurance variable using both survey responses and administrative records (using administrative data effective as of the month the beneficiary was interviewed). To avoid double counting individuals with more than one type of coverage, we assigned beneficiaries into categories based on the following hierarchy, with Medicaid as the highest priority followed by employer-sponsored coverage:

Medicaid (including those who qualify for the qualified Medicare beneficiary and specified low-income Medicare beneficiary programs).

Employer-sponsored supplemental coverage.

Individually purchased private Medicare supplemental coverage.

Other public insurance.

Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) only.

Beneficiaries who did not fall into any of the categories were assigned to the FFS only group. All categories except Medicare FFS only contain beneficiaries with managed care plans.

First, we calculated the distribution of beneficiaries in the five insurance categories for each year we studied between 1992 and 1998 and tested to determine if changes were statistically significant over time accounting for the panel nature of the data (O'Connell, Chu, and Bailey, 2001). We tested for differences between the beginning (1992) and the end (1998) of the time period, adjacent years (e.g., 1995 and 1996), and non-adjacent years (e.g., 1995 and 1998).

Next, we used a five-category multinomial logistic (MNL) regression model to determine which beneficiary characteristics were statistically associated with the likelihood of having different types of supplemental coverage or no supplemental coverage compared with employer-sponsored coverage, controlling for other factors. The analysis was conducted using five annual cross-sectional models (as opposed to using a 5-year pooled data set; therefore, we did not conduct statistical tests over time for subgroups).

We conducted an Independence from Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) test (McFadden, 1974; Stata Corporation, 2000) to determine if the insurance categories of the MNL model met the IIA assumption. We were not able to reject the null hypothesis of the IIA test, which assumes that the inclusion or exclusion of categories does not affect the relative risks associated with the regressors in remaining categories. Readers should bear in mind that evidence suggests that the IIA assumption was violated in our model. However, we do not believe there is an obvious nesting strategy with this choice set and the potentially superior computational alternative of estimating a multinomial probit model is prohibitive. Still, since our model is used to discuss correlational rather causal relationships, the effect of this violation is unknown. Future research needs to be conducted to provide greater insights into this problem.

Employer-sponsored coverage is the omitted category in the MNL model; therefore, all statistics should be interpreted relative to those with this type of coverage. Beneficiary characteristics included age, sex, race, educational attainment, self-reported annual household income, marital status, self-reported health status, number of limitations on activities of daily living (ADLs), region of the country, and metropolitan area status.

Results

In this section we discuss the employer-level findings from the Kaiser/HRET Survey (2000), then the beneficiary-level findings from the MCBS. The employer-level analyses reflect employer responses concerning retiree health benefits, whereas the MCBS data were used to examine all types of coverage held by Medicare-eligible beneficiaries regardless of whether they were career workers. Results from the key informant interviews are included where relevant.

Employer-Level Findings

Offer Rates for Retiree Health Benefits

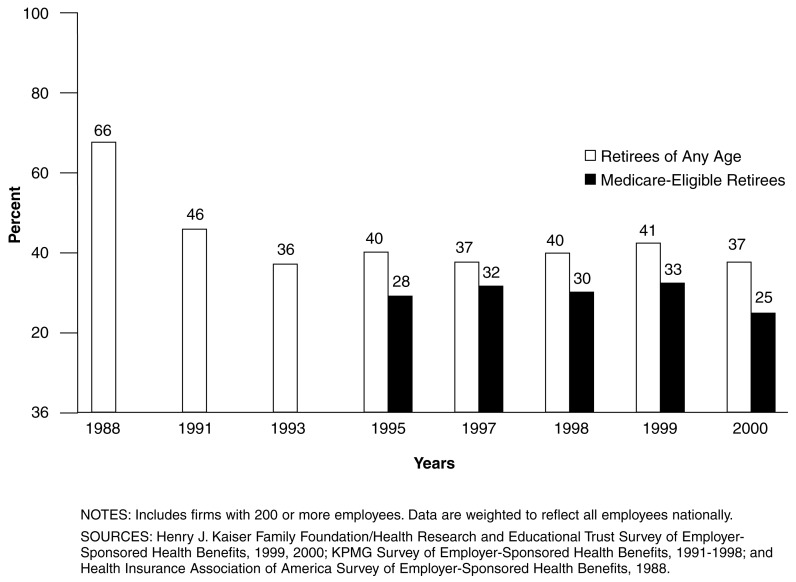

Whether a firm offers health benefits to retirees varies considerably by its size, regional location, industry, and the wage status of employees. In 2000, larger firms (defined in this case as those with 200 or more employees) were significantly more likely (37 percent) to offer retiree health benefits (Figure 1), compared with the national average of 8 percent.4 Employers in the West were significantly more likely (2 percent) to offer coverage, compared to the national average. State and local governments were significantly more likely (28 percent) to offer retiree health benefits than the national average. Firms with a high percentage of low-wage employees (more than 35 percent earning $20,000 or less per year) were significantly less likely to offer retiree health benefits than the national average (2 versus 8 percent, respectively).

Figure 1. Large Firms that Offered Retiree Health Benefits, by Selected Years: 1988-2000.

Larger firms have been consistently more likely than smaller firms to offer retiree coverage over time. In 1988, 66 percent of larger firms (defined again as those with 200 or more employees) offered health benefits to retirees of any age (Figure 2).5 This fell to 46 percent by 1991 and 36 percent by 1993, then hovered around this level for the remainder of the decade. Researchers attribute the decline in the early part of the decade to SFAS 106 which swiftly exerted its influence on coverage rates after the provision became effective. There were no significant differences in offer rates by year for retirees of any age since 1997, the first year that tests were conducted.

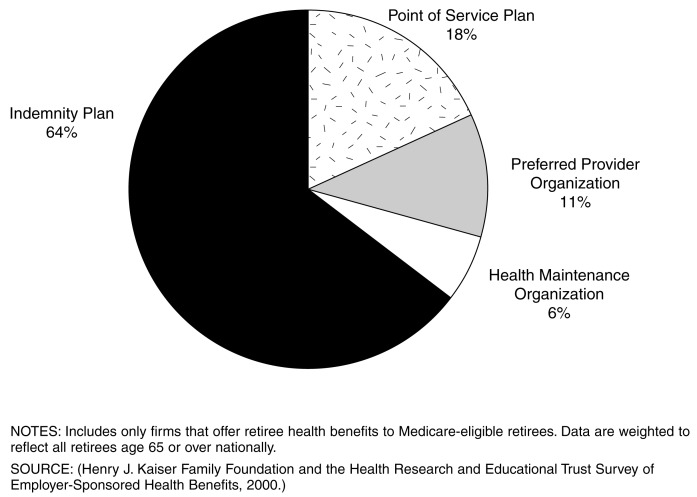

Figure 2. Plan Type with Largest Number of Medicare-Eligible Retirees Enrolled: 2000.

There is also variation among firms regarding whether they cover early versus Medicare-eligible retirees. In 2000, larger firms that offer any retiree health benefits were significantly more likely to cover early retirees than Medicare-eligible retirees (92 versus 67 percent, respectively). Among larger firms that offer health benefits to Medicare-eligible retirees, the data show some fluctuation in the percentage offering them over time (Figure 1). The percentage peaked in 1999 at 33 percent and was at a low point of 25 percent in 2000, but this seemingly large decline was not statistically significant, possibly due to a lack of statistical power. Differences were significant between 1997 and 1998 and 1997 and 2000, but were not significant between 1998 and 1999.

Health Plan Offerings and Enrollment

Employers were asked what type of plan enrolled the largest number of Medicare-eligible retirees. For 64 percent of Medicare-eligible retirees, the employer plan with the largest enrollment was an indemnity/conventional plan (Figure 2). Various types of managed care plans were much less likely to have the largest retiree enrollment. Although it is not possible to make direct comparisons to active employees because the survey only collected this information on the largest retiree plan (whereas information about active employees covers all plans), these enrollment patterns appear to differ considerably. In 2000, 41 percent of active employees with health benefits were enrolled in a preferred provider organization, while just 8 percent were enrolled in an indemnity plan.

Retirees in the West were significantly less likely to have an indemnity plan as their largest Medicare-eligible retiree plan (26 percent) and more likely to have it be an HMO (31 percent). This finding is consistent with enrollment patterns among active employees. Finally, according to the 2000 survey, 61 percent of retirees were offered a Medicare HMO or other M+C plan during the prior year (not shown). Retirees with State and local government employers were significantly less likely than the rest of the Nation to have been offered a Medicare HMO or other M+C plan (30 percent).

Prescription Drug Benefits

Of Medicare-eligible retirees, 98 percent were in firms that reported that all or some of the plans available to their retirees provide prescription drug benefits, whereas just 2 percent were in firms that said none of the plans did. Firms use some prescription drug cost-containment measures more commonly than others, such as cost sharing for various types of drugs. Just over one-half of retirees were in firms that used a two-tier cost-sharing formula6 in the plan with the largest Medicare-eligible retiree enrollment, and another 20 percent were in firms that used a three-tier formula.7

Copayments were considerably more commonplace than coinsurance as a cost-sharing method. Copayments for the largest Medicare-eligible retiree plan averaged $9 for generic drugs, $13 for brand name drugs with no generic substitutes, and $14 for brand name drugs with generic substitutes. Coinsurance rates averaged approximately 20 percent for generics and 29 percent for brand name drugs with generic substitutes. Other popular features of employers' prescription drug benefits included mail order discount plans and formularies. Of Medicare-eligible retirees, 70 percent had a mail order discount plan as part of the firm's largest retiree plan and approximately 55 percent included a formulary.

Changes to Retiree Health Benefits

The Kaiser/HRET survey asked a series of questions about past and planned changes to firms' retiree health benefits. Overall, firms reported making few changes in the past 2 years. The most common change made by 5 percent of firms was an increase in the retirees' cost-sharing requirements when purchasing prescription drugs. A three-tier cost-sharing formula, which increases retirees' cost-sharing requirements when using something other than a generic drug, was introduced by 3 percent of firms. Virtually no firms reduced the maximum lifetime benefit for retirees or capped/reduced the maximum annual benefit for prescription drugs. These findings show that, although some firms are taking steps to rein in retiree health costs, others either did so more than 2 years ago or have not yet embraced these types of cost-containment measures. Four percent of firms reported that they increased the generosity of retiree health benefits in the past 2 years.

These findings mask some differences by firm size. Firms with 1,000-4,999 employees were significantly more likely (12 percent) to have increased the generosity of health benefits offered to retirees than the national average. Midsize, large, and jumbo firms were significantly more likely to have introduced a three-tier cost-sharing formula for prescription drugs (23 percent of jumbo firms). Large and jumbo firms were also significantly more likely to have increased retirees' cost-sharing requirements when purchasing prescription drugs (27 percent of jumbo firms and 12 percent of large firms). Therefore, larger firms were more likely to have increased the generosity of the plan benefits but were also more likely to have implemented cost-containment strategies.

In the next 2 years, more firms are planning changes to their retiree health benefits that will increase the financial burden on retirees (Table 2). For example, 24 percent of firms were somewhat or very likely to introduce a three-tier cost-sharing formula for prescription drugs sometime in the next 2 years. Seventeen percent of firms reported it was somewhat or very likely that they would increase the share of retirees' contributions toward premiums. Approximately 12 percent said it was either somewhat or very likely that they would increase retirees' cost-sharing requirements when purchasing prescription drugs. Time did not allow for followup with employers to confirm if they actually made these changes.

Table 2. Percent of Firms Planning Changes in Their Retiree Health Benefits in the Next 2 Years: 2000.

| Type of Change | Somewhat/Very Likely | Somewhat/Very Unlikely |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Percent | ||

| Introduce Three-Tier Cost-Sharing Formula for Drugs | 24.4 | 71.3 |

| Increase the Generosity of Retiree Benefits | 18.6 | 77.5 |

| Increase Share of Retiree Premium Contribution | 17.0 | 78.8 |

| Increase Retiree Cost-Sharing Requirement for Prescriptions | 12.4 | 83.6 |

| Cap Maximum Employer Contribution | 10.2 | 85.4 |

| Reduce the Maximum Lifetime Benefit | 5.4 | 90.3 |

| Cap or Reduce Maximum Annual Benefit for Prescriptions | 5.0 | 87.8 |

NOTES: Includes only firms that offer retiree health benefits to retirees of any age. On average, approximately 4 percent of respondents indicated that they did not know whether a particular change would occur in the next 2 years. Data are weighted to reflect all employers nationally.

Beneficiary-Level Findings

Trends in Medicare-Related Insurance

The proportion of Medicare beneficiaries with employer-sponsored supplemental insurance coverage declined significantly from a high of 40 percent in 1992 to 36 percent in 1998 (Table 3). Reductions in the percentage of beneficiaries with employer-sponsored coverage occurred for those who obtain coverage directly from their employer and those who obtain it through a union plan. Although we did not analyze data for every year between 1992 and 1998, the trend suggests a fairly steady decline, with a slight slowing in the latter years. Statistically significant declines were found between 1992 and each of the subsequent years in the analysis, as well as, between 1995 and 1996-1998. As rates leveled off between 1996 and 1998, the difference between years during that period were not statistically significant.

Table 3. Trends in Medicare-Related Insurance: 1992, 1995–1998.

| Insurance Coverage | 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Percent | |||||

| Employer-Sponsored Coverage | 40.1 | 38.2 | 37.0 | 36.3 | 35.9 |

| Individual Private Supplemental Coverage | 37.2 | 38.4 | 39.5 | 40.2 | 40.9 |

| Medicaid Coverage | 12.7 | 12.9 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 11.8 |

| Other Public Coverage | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| Medicare Fee-for-Service Only | 8.8 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 8.9 |

NOTE: Includes Medicare beneficiaries age 65 or over regardless of living arrangement or disability status.

SOURCE: Analysis of the 1992, 1995-1998 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey by RTI.

Conversely, the percentage of beneficiaries with individually purchased private supplemental insurance increased significantly over the time period from 37 percent in 1992 to 41 percent in 1998. We found that this increase in individually purchased private supplemental insurance was largely due to increased enrollment in Medicare risk HMOs, while enrollment in medigap plans (which is the largest type of individually purchased private plan in this category) declined over this period (not shown; refer to Technical Note).

Medicaid enrollment declined from 13 to 12 percent over the time period, with statistically significant changes occurring between 1995 and later years. Enrollment in other public insurance plans doubled over the time period studied from 1.3 to 2.6 percent of the population, a statistically significant addition of approximately 600,000 beneficiaries. The percentage of beneficiaries with no supplemental coverage flucuated slightly but hovered around 9 percent between 1992 and 1998, representing 2.8 million beneficiaries in 1998.

Different Types of Medicare-Related Insurance

Using MNL regression, we examined the factors that correspond to having different types of Medicare-related insurance (Table 4). Individuals with employer-sponsored coverage are the omitted category or reference group, therefore model coefficients are interpreted in comparison to this group. In discussing model results, reporting that beneficiaries with a particular characteristic are significantly more (or less) likely to have certain coverage compared with employer-sponsored coverage is equivalent to saying the converse, that these beneficiaries are significantly less (or more) likely to have employer-sponsored insurance. For ease of interpretation, we report results focusing on those with employer-sponsored coverage. We discuss only independent variables that had a significant positive or negative effect on the dependent variable but not the magnitude of the effect (because maximum likelihood coefficients cannot be used directly to estimate magnitude).8

Table 4. Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting the Probability of Having Medicare-Related Insurance, by Selected Characteristics: 1992, 1995-1998.

| Characteristic | 1992 (n = 9,436) |

1995 (n = 11,702) |

1996 (n = 11,791) |

1997 (n = 11,809) |

1998 (n = 12,141) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Individual Private | Medicaid | Other Public | Medicare FFS Only | Individual Private | Medicaid | Other Public | Medicare FFS Only | Individual Private | Medicaid | Other Public | Medicare FFS Only | Individual Private | Medicaid | Other Public | Medicare FFS Only | Individual Private | Medicaid | Other Public | Medicare FFS Only | |

| Age | + | NS | + | NS | + | NS | NS | NS | + | + | NS | — | + | + | — | — | + | NS | — | — |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | — | NS | NS | + | — | NS | — | + | NS | NS | — | + | — | NS | — | + | — | NS | — | + |

| Race | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Black Non-Hispanic | — | + | + | + | — | + | + | + | — | + | + | + | — | + | + | + | NS | + | + | + |

| Hispanic | NS | + | + | + | NS | + | + | + | + | NS | + | + | + | NS | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Other | NS | + | + | + | NS | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Marital Status | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Married | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | NS | — | — | — |

| Education | ||||||||||||||||||||

| High School Graduate | — | — | — | — | — | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| More than High School | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Annual Income | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Less than $25,000 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Region | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Northeast | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | NS | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| North Central | — | — | — | — | — | — | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| South | NS | NS | — | + | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Metropolitan Area | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Urban | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | — |

| Self-Reported Health | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Excellent/Very Good | NS | — | — | NS | NS | NS | — | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | — | — | NS | — | — | NS |

| Good | NS | NS | — | NS | NS | NS | — | — | NS | NS | — | — | NS | NS | — | NS | NS | NS | — | — |

| Limitations on ADLs | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1-2 | NS | NS | + | + | NS | + | + | NS | NS | NS | + | NS | NS | NS | + | NS | NS | NS | + | NS |

| 3 or More | NS | NS | + | + | NS | + | + | + | NS | NS | + | + | + | + | + | NS | NS | NS | + | NS |

NOTES: + indicates a significant positive coefficient at the 0.05 level; − indicates a significant negative coefficient at the 0.05 level. NS is not significant. FFS is Medicare fee-for service. Includes Medicare beneficiaries age 65 or over regardless of living arrangement or disability status. Refers to five cross-sectional models. Employer-sponsored coverage is the reference group in each year. Omitted categories include female; white non-Hispanic; single; less than a high school education; more than $25,000 annual income; living in the West; living in a rural area; in fair or poor health; and having no deficits in the activities of daily living (ADLs).

SOURCE: Analysis of the 1992, 1995-1998 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey by RTI.

Several consistent patterns emerged. In general, there were age and sex differences throughout the time period studied. Older beneficiaries with supplemental insurance were more likely to have purchased it on the individual market than to have obtained it from a current or former employer. Males were generally more likely than females to have employer-sponsored insurance than have purchased it on the individual market but were also more likely to have Medicare FFS only relative to employer-sponsored insurance coverage.

Racial differences were found in each year. In general, minorities were less likely to have employer-sponsored benefits and more likely to have Medicaid, other public coverage or no supplemental coverage. Throughout 1992 to 1998, married beneficiaries were consistently more likely than single beneficiaries to have employer-sponsored coverage.

In each year, greater educational attainment was associated with having employer-sponsored coverage compared with either other private or public supplemental coverage, and was also associated with smaller probability of having Medicare FFS only coverage. Those in the lower household income category ($25,000 or less per year) were less likely than those in higher earning households to have employer-sponsored coverage.

Differences between geographic regions narrowed over time. While in earlier years, enrollment in employer-sponsored plans tended to be more common in the Northeast and North Central regions compared with the West, this was no longer true by 1998. Throughout the time period studied, beneficiaries residing in urban areas were more likely than those in rural communities to have employer-sponsored benefits compared with most other types of coverage. In each year studied, being in poorer health or having limitations on ADLs was associated with a lower likelihood of having employer-sponsored benefits compared with other public coverage.

Overall, the results suggest that certain subgroups of beneficiaries are significantly more likely to have employer-sponsored coverage, controlling for other factors. These include younger beneficiaries, males, white non-Hispanics, individuals with more education and income, and those who are married. Regional differences may be disappearing if the relationships found in the 1998 sample are the beginning of a trend.

Discussion and Policy Implications

The prevalence of employer-sponsored retiree health insurance has declined since the late 1980s, and this decline continued with the implementation of SFAS 106 in 1993. Under conditions highly favorable to expanding benefits (low inflation and an expanding economy) during the mid-1990s, the proportion of large firms offering coverage to retirees remained fairly constant at best. The offer rate did not change statistically throughout the remainder of the decade for retirees of any age. However, the proportion of large firms offering retiree health benefits to the Medicare-eligible population in 2000 was significantly lower than just a few years earlier (1997, the first year in which statistical tests could be conducted), although the decline was not linear.

Altogether, our employer-level data suggest a continued downward trend in the availability of employer-sponsored coverage for those of Medicare age, which is consistent with findings from other employer-level data sources (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2001). It is also consistent with our findings from our beneficiary-level data, which show a statistically significant decline in the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries with employer-sponsored coverage between 1992 and 1998. However, the rate of decline in the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries who report having employer-sponsored supplemental coverage appears to be slowing toward the end of the time period we studied (1996 to 1998). Analysis of beneficiary-level data beyond 1998 is needed to assess if this slowing in enrollment continued.

Despite the decline in employer-sponsored coverage among Medicare-eligible retirees, the percentage of those with Medicare FFS only coverage remained at about 9 percent between 1992 and 1998. It seems that the decline in employer-sponsored coverage among Medicare-eligible retirees, while not precipitous of late, has been offset by a shift toward other types of coverage, namely, M+C plans and non-Medicaid forms of publicly sponsored health insurance. The decline in employer-sponsored coverage occurred simultaneously with a sizable decline in the proportion of beneficiaries with medigap coverage, presumably due to increased costs for this type of coverage.

Because of these trends, even more Medicare beneficiaries will face a greater financial burden for the cost of their health care and have fewer affordable or adequate coverage options. It is unclear how long M+C plans and other public coverage can effectively serve as a stopgap for reductions in the more traditional sources of Medicare supplemental insurance. The shift toward M+C plans coincided with a peak in the number of these plans available. Since then, the number of available plans has decreased and costs for continuing plans have risen. The future of the M+C program appears uncertain due to rising premiums and plan withdrawals, which are causing employers to take a wait and see approach regarding whether they will offer this type of coverage. Other public sources of coverage are generally limited in scope and duration and are not adequate replacements for lost employer-sponsored benefits.

Retirees on fixed incomes who lose employer-sponsored benefits may find medigap coverage unaffordable; those with pre-existing health conditions may be unable to qualify for coverage. For those who retain benefits through an employer, coverage for drugs, vision, and dental services may be lost as employers reduce the richness of benefit packages. Thus, retirees who still have employer coverage may find that it is of less value or reduced quality. It is reasonable to conclude that because of declines in supplemental coverage, a growing number of retirees will eventually either have to pay directly for medical services previously covered by insurance, turn to publicly-sponsored insurance programs, or go without services. Publicly financed programs will be increasingly pressured to fill the void, and the limits of these programs will soon be tested.

Faced with double-digit increases in premium costs and an economic downturn exacerbated by the events of September 11, 2001, employers will continue looking for ways to contain the cost burden of health insurance beyond shifting costs to retirees and restricting the access of future retirees to health benefits. Popularity of the tiering approach to prescription drug coverage is also likely to continue. Another option may include moving from a defined benefit to a defined contribution approach, under which an employer would specify a dollar amount with which retirees could purchase their own insurance. Although there are a variety of defined contribution approaches, the concept generally shifts responsibility, payment, and the risk of selecting health care services from employers to employees.

One factor complicating an employer's decision to offer retiree health insurance is a Third Circuit Court ruling last year in Erie County Retirees Association v. County of Erie. The court held that a retiree medical program violates the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) if it provides lesser benefits to Medicare-eligible retirees than to younger retirees. A program that offers lesser benefits to retirees over age 65 is considered non-discriminatory only if the program satisfies either the equal benefit or equal cost test under the ADEA. Depending on subsequent interpretations and application of the decision, programs that provide more choice prior to age 65 or that provide only HMO coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees could be at risk. Similarly, programs that require Medicare-eligible retirees to pay higher premium contributions than non-Medicare retirees or that provide coverage for early retirees but not Medicare-eligible retirees may be held discriminatory. The prospect of ADEA litigation is likely to discourage employers from expanding choice or options within existing retiree health insurance programs or for new firms to adopt retiree health benefits programs. However, as of July 2001, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which has previously indicated it would enforce the Erie decision, reversed itself and suspended enforcement pending further review.

Two other legislative efforts may also affect the likelihood the offering of employer-sponsored benefits. If a patients' bill of rights is passed allowing employers that provide health insurance to be sued for medical errors, employers may choose to drop or extremely limit health benefits to reduce their exposure to liability. Also, if Congress were to approve a Medicare prescription drug benefit, employers would experience reduced outlays for prescriptions, which may enable them to continue offering retiree health insurance. Waivers approved by CMS in summer 2001 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2001) are another factor that may encourage employers to continue offering coverage. Through these waivers, employers have increased flexibility in designing and marketing retiree health plans.

In conclusion, the future of employer-sponsored retiree health benefits for the Medicare-eligible population is uncertain. The forces discouraging its future growth—rising premium costs, a slower economy, judicial challenges, and an uncertain M+C program and policy agenda—far outweigh the forces likely to encourage expansion. The likely erosion in retiree health benefits will have profound implications. Early retirees will be more likely to delay their retirement or may seek employment in larger firms. Medicare-eligible retirees will face higher out-of-pocket expenses, particularly for prescription drugs. Medicare will likely have lower program spending, but retirees will increasingly turn to Medicaid for protection from rising health care costs. Thus, the repercussions from decisions made by private businesses may intensify public controversy as to how America should finance health care for older adults. Future research should explore mechanisms to encourage employers to offer coverage. Attention should also be given to monitoring trends in coverage for early versus Medicare-eligible retirees and among selected subgroups such as females, minorities, individuals with low income, those in poor health, or those who reside in certain areas of the country.

Technical Note

Murray and Eppig (2002) found that medigap enrollment decreased from 32 percent in 1992 to 24 percent in 1998 among beneficiaries age 65 and over. Although this study and the Murray and Eppig (2002) study used the same data and time period, the studies diverged regarding their definitions of the insurance variables. The primary difference was that Murray and Eppig categorized all beneficiaries with risk HMO coverage into a freestanding HMO category, while our study subsub-sumed these individuals into the other insurance categories reflecting the source of coverage. Another difference in approaches was that Murray and Eppig categorized beneficiaries into employer-sponsored coverage if they reported having a supplemental plan from a private (as opposed to a public) source, whereas we took a more conservative approach, requiring beneficiaries to specifically indicate that their source of private coverage was employer related.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of our CMS project officer, Brigid Goody in developing this manuscript, and helpful comments provided by four anonymous reviewers on an earlier draft of it. We also appreciate the programming assistance of May Kuo.

Footnotes

Lauren A. McCormack, Nancy D. Berkman, Wayne L. Anderson, and Nathan West are with RTI. Jon R. Gabel, Heidi Whitmore, and Jeremy Pickreign are with the Health Research and Educational Trust (HRET). Kay Hutchison is with the University of Wisconsin at Madison. This study was funded by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under HCFA Contract Number 500-95-0061/TO8. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of RTI, American Hospital Association, University of Wisconsin at Madison, or CMS.

These surveys are conducted by William M. Mercer, Inc., and the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation/HRET (a non-profit 501(c)3 research organization affiliated with the American Hospital Association).

Termed Standard Financial Accounting Standard-SFAS 106-Employers' Accounting for Post-retirement Benefits Other Than Pensions.

Prior to 1999, this survey was sponsored by KPMG Peat Marwick and the Health Insurance Association of America.

Percentages referenced in this paragraph are representative of all firms, including those that do not offer any health benefits. Data refer to retirees of all ages.

Trend data are only available for larger firms. This survey question did not distinguish between early and Medicare-eligible retirees.

Under two-tier cost-sharing formulas, retirees face one level of copayments (or coinsurance) when using generic drugs and a higher level of copayments when using brand name drugs.

With three-tier cost sharing, retirees face one level of copayments when using generic drugs, a higher level of cost sharing when using a brand name drug when no generic drug is available, and a still higher copayment level when using a brand name drug when a generic drug is available.

Detailed results, including coefficient values, are available from the authors.

Reprint Requests: Lauren A. McCormack, Ph.D., RTI, 3040 Cornwallis Road, P.O. Box 12194, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709. E-mail: lmac@rti.org

References

- Anderson W, Hutchison K, West N, et al. Summary of Findings from Key Informant Interviews from the Retiree Health Benefits Project. 2001. Paper to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under HCFA Contract No. 500-95-0061. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Operational Policy Letter 132. Internet address: http://www.medicare.gov. Accessed November 2001.

- Employee Benefits Research Institute. Retiree Health Benefits: What the Changes May Mean for Future Benefits. Washington, DC.: Jul, 1996. Brief No. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Employee Benefit Research Institute. Employment-Based Health Benefits: Trends and Outlook. Washington, DC.: May, 2001. Brief No. 233. [Google Scholar]

- Eppig F, Chulis G. Trends in Medicare Supplementary Insurance: 1992-96. Health Care Financing Review. 1997 Fall;19(1):201–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox P. Employer Contracting with HMOs for Medicare Retirees. Aug, 2000. Paper to the Public Policy Institute of AARP.

- Gabel JR, Ginsburg P, Hunt K. Small Employers and Their Health Benefits, 1988-1996: An Awkward Adolescence. Health Affairs. 1997;16(5):103–110. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research and Educational Trust. Employer Health Benefits: 2000 Annual Survey. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Menlo Park, CA: Health Research Educational Trust of the American Hospital Association; Chicago, IL.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt and Associates. Retiree Health Coverage: Recent Trends and Employer Perspectives on Future Benefits. Menlo Park, CA.: Oct, 1999. Prepared for the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Khandker R, McCormack LA. Medicare Spending by Beneficiaries with Various Types of Supplemental Insurance. Medical Care Research and Review. 1999;56(2):137–155. doi: 10.1177/107755879905600202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Ginsberg C, Olin G, Merriman B. Health and Health Care of the Medicare Population: Data from the 1996 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Westat; Rockville, MD.: Dec, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D. Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behavior. In: Zarembka P, editor. Frontiers in Econometrics. Academy Press; New York, NY.: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Eppig F. Insurance Trends for the Medicare Population, 1991-1999 Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Health Care Financing Review. 2002 Spring;23(3):9–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell J, Chu A, Bailey R. Considerations for Analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Across Time. Internet address: http:\\hcfa.gov/surveys/mcbs/PublBIB/Mbibl5.pdf Accessed November 2001.

- Rice T, Desmond K, Gabel JR. The Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act: A Postmortem. Health Affairs. 1990;9(3):75–87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.9.3.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski J, Karoly L. Health Insurance and Retirement Behavior: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Survey. Journal of Health Economics. 2000;19(4):529–539. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(00)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rother J. A Drug Benefit: The Necessary Prescription for Medicare. Health Affairs. 1999;18(4):20–22. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corporation. Stata Corporation; College Station, TX.: 2000. Stata Statistical Software Release 7.0. Technical Bulletin Number 58. Internet address: http://www.stata.com/stb/stb58/sgl55/ Accessed November 2001. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Medicare+Choice: Plan Withdrawals Indicate Difficulty of Providing Choice While Achieving Savings. U.S. General Accounting Office; Washington, DC.: Sep, 2000. GAO/HEHS-00-183. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Retiree Health Benefits: Employer-Sponsored Benefits May Be Vulnerable to Further Erosion. U.S. General Accounting Office; Washington, DC.: May, 2001. GAO-01-374. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Ratings Inc. Prescription Drug Costs Boost Medigap Premiums Dramatically. Internet address: http://www.weissratings.com Accessed November 2001.