Abstract

The Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997 included major changes to Medicare's home health benefit designed to control spending and promote efficient delivery of services. Using national data from Medicare home health claims, this study finds the initial effect of the BBA was to steeply reduce use of the home health benefit and intensify its focus on post-acute skilled nursing and therapy services. The striking responsiveness of home health agencies (HHAs) to altered financial incentives suggests that we may again see large shifts in patterns of care under the new incentives of Medicare's prospective payment system (PPS) for home health.

Introduction

In response to nearly a decade of steep growth in Medicare spending for home health care, Congress included in the 1997 BBA major changes to Medicare's home health benefit designed to rein in spending and alter the financial incentives of providers. The rapid expansion of home health use—which accounted for one-tenth of Medicare's benefit spending by 1996—had not only led to concerns about its effects on Medicare's budget, but also about whether all of the services being provided were appropriate for Medicare to cover. Many observers thought the benefit's scope had expanded from its original focus on post-acute skilled nursing and rehabilitative care and was increasingly paying for long-term care (LTC)—that is, personal assistance with basic tasks, such as bathing and dressing, for people with chronic conditions or disabilities (Bishop and Skwara, 1993). Although people not needing skilled nursing or therapy services are not eligible for the benefit, trends in patterns of use suggested that for people needing personal care alongside skilled nursing or therapy, the benefit was increasingly assisting with personal care. In addition, the incentives of the cost-based payment system for home health promoted a high volume of visits and gave agencies little incentive to provide an efficient amount or mix of services.

The BBA's most important changes in home health policy were in the way Medicare pays agencies, although it also modified eligibility and coverage rules. The BBA sought to immediately put the brakes on home health spending with the interim payment system (IPS). Under the previous rules, a HHA was reimbursed its costs, subject to a limit on its average payment per visit during the year. The IPS not only tightened this per-visit cap, but also capped the average payment an agency could receive for each Medicare enrollee it treated. Because this new per-beneficiary cap was based on patterns of care from several years earlier, at least some agencies were under pressure to cut back their patients' average use in order to keep the agencies' costs within their payment limits. Although the per-beneficiary limits gave agencies an incentive to look more closely at whether every visit was necessary or appropriate for Medicare to cover, they did not take into account the health status or care needs of an agency's patient pool.

Many observers were concerned that in response to the tightened payment limits, HHAs might seek to avoid or reduce services to patients needing the most extensive care (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2000a; Komisar and Feder, 1998; Lewin Group, 1998; Smith and Rosenbaum, 1998). Historically, high-volume users were disproportionately older, in poorer health, more likely to have Medicaid coverage, and more likely to have a substantial level of disability (Leon, Neuman, and Parente, 1997). The new payment caps also gave agencies incentives to expand their volume of short-term, relatively low-cost patients.

This article examines how agencies responded to the IPS and concurrent policy changes by analyzing changes in patterns of home health care use, including the mix of types of services, and the characteristics of Medicare enrollees using the benefit. The analysis compares patterns in fiscal year (FY) 1997 (October 1, 1996-September 30, 1997), the year before IPS began, with FY 1999, the first year IPS was fully in place for all agencies. The data are from Medicare enrollment and claims records for a nationally representative sample of enrollees.

Background

Medicare's home health benefit enables homebound enrollees needing intermittent skilled nursing or certain therapy services to receive this care at home. The emphasis of the benefit is on rehabilitative and skilled nursing care, which when delivered at home can shorten hospital stays and reduce Medicare enrollees' use of residential skilled nursing or other institutionally based services. After an expansion of eligibility rules for the benefit in 1989, Medicare's spending on home health surged, prompting the policy changes in the BBA.

Home Health Benefit

To qualify for Medicare's home health benefit, a Medicare enrollee must be homebound (unable to leave home under normal circumstances) and need intermittent skilled nursing care (other than solely for venipuncture), physical or speech therapy, or continuing occupational therapy (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2000a; Health Care Financing Administration, 1999).1 He or she must be under a care of plan established and periodically reviewed by a physician. For people who meet the eligibility criteria, Medicare will pay for the following types of visits provided by a Medicare-certified HHA intermittent or part-time skilled nursing care or home health aide services; physical, speech, or occupational therapy; and medical social services. There is no ceiling on the number of covered visits, as long as an enrollee continues to meet the benefit's eligibility rules. In addition to visits, Medicare covers most medical supplies and durable medical equipment (such as walkers and oxygen equipment) furnished by HHAs. Enrollees do not have to pay any cost-sharing expenses for home health visits and related supplies, but are responsible for 20 percent coinsurance for durable medical equipment.

Although people eligible for the home health benefit may receive some personal assistance with fundamental tasks of life—such as bathing and meal preparation—from home health aides, the coverage of such services is limited. Medicare does not cover personal assistance or household services if these are the only home care services a person needs. Home health aide visits must be prescribed by a physician for the purpose of providing services needed to maintain the recipient's health or facilitate treatment, which can include personal care. Aides are also permitted to offer a small amount of incidental personal or household services at the time they administer covered care. Home health aides are trained to provide health assistance, such as changing bandages or dressings, and other care that is supportive of skilled nursing or therapy; they typically have more training than personal care aides (Feldesman, 1997).

Historical Growth in Home Health Use

The Medicare Program has always included a home health benefit, but over time changes in laws, regulatory rules, and administrative practices have influenced its use (Health Care Financing Administration, 1999; U.S. General Accounting Office, 1996). Originally, enrollees with a recent hospital or nursing home stay could receive up to 100 visits under Part A with no beneficiary cost sharing. Enrollees who did not have a recent institutional stay, or who had exhausted their 100 visits under Part A, could receive up to 100 visits under Part B; however, Part B services were subject to cost sharing—the Part B deductible ($50 in 1966) and 20-percent coinsurance. In 1972, the coinsurance requirement was eliminated for Part B home health services. The Omnibus Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1980 removed the prior institutional stay requirement for Part A, the 100-visit cap for both Parts A and B, and the application of the Part B deductible to home health (Health Care Financing Administration, 1999). In addition, OBRA made it easier for for-profit HHAs to participate in Medicare by eliminating the requirement that they be licensed by their State (Health Care Financing Administration, 1999).

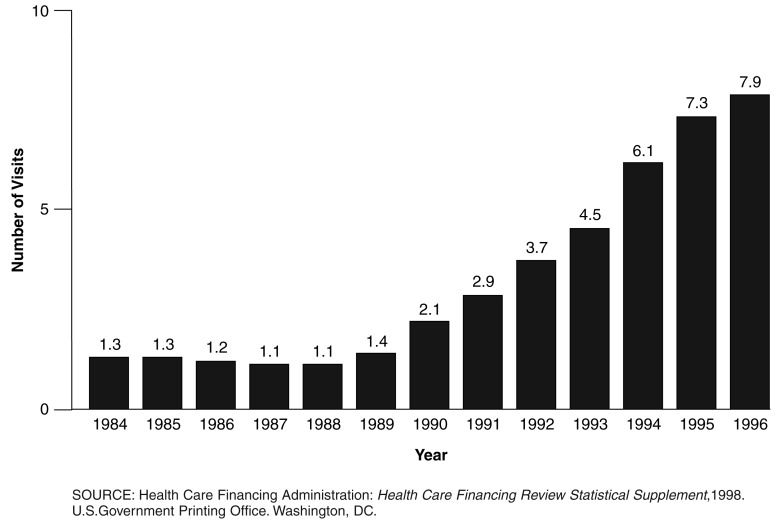

When Medicare adopted PPS for inpatient hospital care in October 1983, it seemed likely that home health use would expand as hospitals shortened patients' stays in response to the incentives of the new system, but this did not occur. Instead, a combination of regulatory practices and other policies effectively constrained the benefit's use for several years. Between 1984 and 1988, the proportion of Medicare enrollees using home health, the average number of visits received by users, and Medicare's home health spending per enrollee (adjusted for general inflation), changed little (Federal Register, 1998; U.S. Department of Labor, 2001).2 Indeed, home health visits per enrollee fell slightly over the period (Figure 1). Some of the factors that appear to have controlled spending were: reducing the number of intermediaries processing home health claims and increasing education to intermediaries to enhance consistency in the review of claims; increasing the number of claims reviewed by intermediaries; and requiring more detailed documentation of claims (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1996). Reflecting the enhanced oversight, the claim denial rate grew from 3.4 percent in 1985 to 7.9 percent in 1987 (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1996).

Figure 1. Medicare Home Health Visits per Enrollee: 1984-1996.

An expansion of eligibility and coverage rules in 1989, however, sparked a period of rapid growth in Medicare home health use and spending (Bishop and Skwara, 1993; U.S. General Accounting Office, 1996; Kenney and Moon, 1997). In 1989, as part of an agreement reached in a lawsuit, the Health Care Financing Administration revised the payment manuals for HHAs and intermediaries to clarify the eligibility and coverage standards for home health care (Duggan versus Bowen, 1988). The revisions made a broader range of Medicare enrollees eligible for home health care and allowed them to receive a greater number of, and more frequent, visits than under prior practices. Specifically, the revisions clarified that eligibility based on needing intermittent skilled nursing care can usually be established if a beneficiary needs skilled nursing services at least once in 60 days, and can also be met if a person has a less frequent, but recurring, need for such care (Price, 1996; Health Care Financing Administration, 1989). They further specified that enrollees who are in stable condition or need chronic skilled care can be eligible for home health care; previously, eligibility rules had been interpreted as requiring that an enrollee's condition be improving. Also, skilled nursing services were defined to include observation and management of patient care, as well as direct services. The revisions also defined coverage rules that in effect enabled agencies to increase the frequency of visits, by permitting full-time care (8 hours per day) for up to 21 consecutive days, or longer in exceptional cases where the person's need for care was finite and predictable (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1996).

After the 1989 expansion in eligibility and coverage, both the share of enrollees using the home health benefit and the average number of visits per user grew rapidly. The proportion of enrollees using the benefit more than doubled between 1988 and 1996, rising from 4.8 to 10.7 percent (Health Care Financing Administration, 1998). The average number of visits received by home health users grew even more rapidly, nearly tripling between 1988 (24 visits per user) and 1996 (74 visits) (Health Care Financing Administration, 1998). Driven by both these trends, Medicare's home health spending (in 1999 dollars) grew from $83 per enrollee in 1988 to $528 in 1996, or at an average rate of 26 percent per year after adjusting for general inflation. In comparison, over the same period, Medicare Program payments per enrollee for all benefits grew an average of about 4 percent per year, after adjusting for general inflation.3 As a result, home health grew from 2.4 percent of total Medicare payments for benefits in 1988 to 10 percent in 1996 (Health Care Financing Administration, 1998).

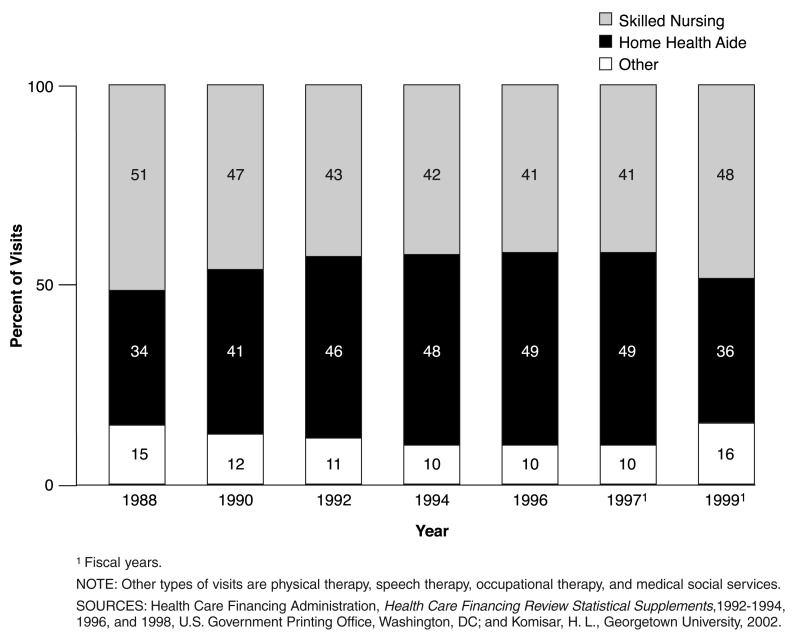

The 1989 changes in eligibility and coverage rules may have allowed more people to take advantage of medical innovations that enable some patients to be treated at home or in an outpatient setting followed by home-based care. However, changes in patterns of care suggested the benefit was increasingly covering supportive, personal care for people needing both skilled and personal care (Bishop and Skwara, 1993). As home health use grew, episodes grew longer on average and the distribution of users shifted toward more high-volume users. Indeed, growth in use of home health by high-volume users was a major source of overall growth in spending for the benefit. For example, users receiving 200 or more visits in a year accounted for about 60 percent of the growth in home health spending between 1991 and 1994 (Komisar and Feder, 1998). At the same time, there was shift in the mix of visit types toward the use of substantially more home health aide visits. Longer episodes were found to include a relatively higher proportion of home health aide visits throughout the episode (Prospective Payment Assessment Commission, 1996).

As home health use expanded, some people questioned whether all of the care provided under the benefit was appropriate for Medicare to cover. Further, a deterioration of regulatory controls since the mid-1980s, may have contributed to delivery of excessive services and coverage of ineligible beneficiaries (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1996). For example, the 1989 payment manual revisions required that intermediaries determine that each denied visit was not medically necessary at the time it was ordered; in contrast, previous practice had enabled an intermediary to deny all visits beyond the number it considered necessary. The change increased the costs of reviewing claims for medical necessity and resulted in fewer denials (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1996).

In addition, Medicare's method of paying for home health probably contributed to the rising volume of services. At the time the BBA was enacted, the home health benefit was one of the few parts of the Medicare Program under which payment was still largely based on the provider's costs, rather than on prospectively established rates. Prior to the BBA, Medicare paid HHAs their allowable costs, subject to a specified limit on the agency's average payment per visit during the year. Each agency's annual payment limit was computed by multiplying the number of each type of visit it provided by a national limit for that type of visit, and then summing across visit types. The national limits were set at 112 percent of the national average cost per visit incurred by freestanding (not hospital-affiliated) HHAs for each type of visit, with adjustments for urban or rural location and geographic differences in wage rates. Because the limit was applied to the agency's total Medicare services in the year, an agency could offset above-average costs for some visits with below-average costs for others. Thus, an agency had an incentive to expand its volume of visits, so long as the cost of additional visits was below its average limit.

Home Health Policy Changes

The BBA modified Medicare's home health policy in several ways, the most important of which affected Medicare's method of paying for home health (U.S. House of Representatives, 1997; Federal Register, 2000). The aim of the changes was not only to control the price of home health services, but to also constrain the volume of services, largely by changing the financial incentives of HHAs.

IPS was phased in during FY 1998, becoming effective for each agency at the start of its cost reporting period. Under IPS, agencies' payment limits were modified and tightened. An agency's annual payment was its allowable costs up to the lower of two limits. The per-visit limit was computed using a method similar to the previous limit, but tightened by certain modifications.4 The second limit capped how much an agency could receive for each beneficiary it served. This per-beneficiary limit was based on a blend of the agency's costs (75 percent) and the average costs of agencies in its census region (25 percent) during a base year—cost-reporting periods ending during Federal FY 1994—updated to reflect some of the growth in input costs (such as wages) of agencies since the base year. For “new” agencies—those that had not participated in Medicare for a full year by October 1994—the per beneficiary amount was based on the 1994 national median payment per beneficiary. Subsequent legislation eased the per-visit and per-beneficiary limits slightly beginning in FY 1999.5

Home health PPS replaced IPS for all agencies on October 1, 2000. (The BBA required the PPS to apply to agencies' cost reporting periods beginning on or after on October 1, 1999, but the start date was changed to October 1, 2000 for all agencies, regardless of cost reporting period, by the Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1999, Public Law 105-277.) Under PPS, Medicare pays agencies a set payment rate for each 60-day episode of care, regardless of the specific services delivered (Federal Register, July 2000). The rate is adjusted to reflect the home health recipient's classification according to a case-mix system for home health, and to reflect the wage level in the agency's location. The payment formula also includes adjustments for: low-volume episodes (those consisting of four or fewer visits); significant changes in the home health recipient's condition; and partial episodes (those in which the home health recipient is discharged and returns to the same agency during the 60-day episode or the recipient elected to transfer to a different agency). Outlier payments are also made for unusually costly cases. Originally, the BBA required PPS rates to be set so that estimated Medicare spending for home health would be equivalent to what would have been spent under IPS if IPS's payment limits were reduced by 15 percent—but more recent legislation delayed the reduction until October 1, 2002.6 In implementing this requirement, the FY 2003 PPS rates were reduced by 7 percent, the amount estimated by CMS to yield the equivalent reduction in spending as would have occurred if IPS limits were reduced by 15 percent and updated to FY 2003 (Federal Register, 2002).

The BBA also modified Medicare's eligibility and coverage rules for home health. Perhaps most important, the BBA narrowed the eligibility criteria for the benefit by no longer allowing a person to meet the requirement of needing skilled nursing solely on the basis of requiring venipuncture for drawing a blood sample. In addition, the BBA defined intermittent skilled nursing care for determining eligibility and part-time or intermittent skilled nursing and home health aide care for determining covered services in ways that differed from previous standards. The main effects were to expand eligibility slightly to include some people needing frequent visits over several weeks, but at the same time to narrow the amount of covered services (Komisar and Feder, 1998).

In addition to the BBA, legislation and regulations aimed at reducing fraud in home health services and increasing review of claims may have helped control spending during the late 1990s (McCall et al., 2001; U.S. General Accounting Office, September 2000b). Begun in 1995 in 5 States and expanded to 18 by 1998, Operation Restore Trust is a Federal initiative designed to identify fraud and abuse among HHAs, nursing homes, and medical equipment suppliers through the use of audits, inspections, hotlines, and other activities. Also, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 imposed monetary penalties on physicians for fraudulently certifying ineligible beneficiaries for Medicare home health services. In addition, regulatory changes in 1997 placed a 6-month moratorium on certification of new HHAs, required existing agencies to reapply every 3 years for continued certification, and increased the volume of government audits of agencies and reviews of claims.

Data and Study Design

The analysis uses data from Medicare home health claims and eligibility records for a national sample consisting of 1 percent of Medicare enrollees. Two years are compared: FY 1997 (October 1, 1996-September 30, 1997), the year before the IPS became effective, and FY 1999, the first year that IPS was fully implemented for all agencies. The study population is defined as all Medicare Part A enrollees residing in the 50 States or the District of Columbia, excluding individuals enrolled in Medicare managed care plans. For part-year enrollees, observations are weighted by the proportion of the year the person was in the study population.

The level of analysis is a Medicare enrollee's experience during the specified year. An enrollee is defined as a home health user in a specified year if he or she received at least one Medicare-covered home health visit during that year. The basic measure of level of home health use is the number of visits a person received during the designated year. We chose this measure—annual visits per person—rather than visits per home health episode because we hypothesized that the policy changes could affect the number of episodes a person received. For example, if visits per episode declined, but the number of episodes per person increased, just looking at visits per episode would overstate the decline in use at the person level. In addition, using annual visits provides a straightforward assignment of use to the pre-BBA (FY 1997) or post-BBA (FY 1999) time period.

A definition of an episode of home health was needed for some aspects of the analysis, such as counting the number of episodes during the FY. For these, an episode is defined as a period of Medicare-covered home health use that was both preceded and followed by a gap of 60 or more days in which the person did not use Medicare home health care. The analysis for a specified year is based on all episodes that have days within that year (but do not necessarily begin or end within it). To identify episode start and end dates, the data observation period was chosen to be equivalent for each FY (1997 and 1999), within the range allowed by data availability. Specifically, for each FY, service use was tracked from 9 months before the FY's start through 3 months after the FY's end.

Another concept applied in the analysis is whether a home health episode followed a recent inpatient hospital stay. Home health users are defined to have a prior hospital stay if they had Medicare-covered inpatient hospital or skilled nursing facility use within 14 days of the beginning of a home health episode. (Skilled nursing facility care is included in the definition because Medicare covers this type of care only when it is preceded by a hospital stay of at least 3 days.) People with multiple home health episodes within the year are classified as having a prior hospital stay if any of their episodes followed a hospital stay. An important limitation in identifying people with prior hospital stays is that the beginning of a home health episode is not always observed in the data. Specifically, if an episode began more than 6-1/2 months before the first home health use within the FY being examined (or, less commonly, if a person was newly eligible for Medicare when he or she began using Medicare home health) then the prior hospital stay status is unknown. This results in 15 percent of home health users in FY 1997, and 8 percent in FY 1999, with unknown prior hospital stay status.

Patterns of Home Health Use

Two years after the BBA was enacted, overall home health use per enrollee was less than one-half what it had been before the BBA. Between FY 1997 and FY 1999, average visits per enrollee fell by 54 percent (from 8.0 to 3.7), reflecting drops in both the share of enrollees using home health and the average number of visits per user. (In reporting the study's findings, all years are Federal FYs unless otherwise specified.) In 1999, the share of enrollees using home health was 21 percent less than in 1997 (8.0 percent compared with 10.1 percent) and users received 41 percent fewer visits (46 visits, on average, compared with 79 in 1997). The decline in visits per user played the larger role, accounting for about two-thirds of the overall drop in average visits per enrollee.

Medicare's home health spending per enrollee fell nearly proportionately with visits, reflecting the relative stability of average payments per visit. Spending per enrollee fell by 52 percent (adjusting for general inflation), from $520 to $249 (both in 1999 dollars). The data on home health spending used in the analysis are the interim payments made by home health intermediaries to agencies; they do not reflect any final reconciliation and payment settlement, which generally occur 2 years or longer after the close of the cost reporting period (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2000c). Spending was adjusted for general inflation using the Consumer Price Index-All Urban Consumers, All Items. Average spending per visit grew only 3 percent, from $65 to $67 (in 1999 dollars).

Differences Among Demographic Groups

Based on the incentives of IPS and other policies, it was expected that enrollees in groups that, on average, used home health more extensively before the BBA would have largest drops in the proportion of enrollees using home health. The results indicate that this did occur to some extent, but the drops in utilization were substantial for all examined demographic groups and the variation among groups was not large (Table 1). Three enrollee groups who in 1997 averaged the most visits per person, experienced a somewhat larger drop in the likelihood of obtaining any home health care at all: enrollees age 75 or over; enrollees with Medicaid; and residents of rural areas. The proportion of users fell by 23 and 22 percent, respectively for enrollees age 75-84 and 85 or over, compared with a 20 percent drop for both enrollees age 65-74 and those under age 65. People dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare experienced a 25-percent drop in the proportion using home health, compared with a 20-percent drop among other Medicare enrollees. Also, residents of rural areas experienced a drop of 26 percent compared with 19 percent for urban residents. A notable exception occurred for disabled enrollees under age 65—they, too, used a relatively high number of average visits in 1997, but did not experience an above-average drop in users.

Table 1. Medicare Home Health Care Use, by Characteristics of Enrollees: Fiscal Years 1997 and 1999.

| Characteristic | Home Health Users as a Percent of Enrollees | Number of Visits per User | Number of Visits per Enrollee | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| 1997 | 1999 | Percent Change | 1997 | 1999 | Percent Change | 1997 | 1999 | Percent Change | |

| Total | 10.1 | 8.0 | -21 | 79 | 46 | -41 | 8.0 | 3.7 | -54 |

| Age | |||||||||

| Under 65 Years | 5.6 | 4.5 | -20 | 87 | 56 | -35 | 4.9 | 2.5 | -48 |

| 65-74 Years | 5.9 | 4.8 | -20 | 68 | 42 | -39 | 4.1 | 2.0 | -51 |

| 75-84 Years | 13.3 | 10.2 | -23 | 76 | 44 | -42 | 10.1 | 4.5 | -55 |

| 85 Years or Over | 22.2 | 17.2 | -22 | 91 | 50 | -45 | 20.3 | 8.6 | -58 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 11.5 | 9.1 | -21 | 82 | 47 | -43 | 9.4 | 4.3 | -55 |

| Male | 8.2 | 6.5 | -21 | 74 | 45 | -39 | 6.0 | 2.9 | -52 |

| Age and Sex | |||||||||

| Under 65 Years, Female | 6.6 | 5.3 | -20 | 89 | 55 | -39 | 5.9 | 2.9 | -51 |

| Under 65 Years, Male | 4.8 | 3.8 | -19 | 85 | 58 | -32 | 4.1 | 2.2 | -45 |

| 65-74 Years, Female | 6.5 | 5.2 | -19 | 73 | 43 | -41 | 4.7 | 2.2 | -53 |

| 65-74 Years, Male | 5.2 | 4.2 | -20 | 62 | 40 | -35 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 48 |

| 75-84 Years, Female | 14.4 | 11.0 | -24 | 79 | 45 | -43 | 11.3 | 5.0 | -56 |

| 75-84 Years, Male | 11.5 | 9.1 | -21 | 71 | 42 | -41 | 8.1 | 3.8 | -53 |

| 85 Years or Over, Female | 22.4 | 17.7 | -21 | 92 | 50 | -46 | 20.6 | 8.8 | -57 |

| 85 Years or Over, Male | 21.6 | 16.2 | -25 | 90 | 50 | -45 | 19.4 | 8.0 | -59 |

| Medicaid Enrolled | |||||||||

| Yes | 15.3 | 11.4 | -25 | 102 | 58 | -43 | 15.6 | 6.7 | -57 |

| No | 9.2 | 7.3 | -20 | 72 | 43 | -41 | 6.6 | 3.1 | -53 |

| Urban/Rural Location | |||||||||

| Rural | 10.4 | 7.7 | -26 | 85 | 49 | -42 | 8.8 | 3.8 | -57 |

| Urban | 10.0 | 8.1 | -19 | 76 | 45 | -41 | 7.7 | 3.7 | -52 |

| Spending per Enrollee in 1996 | |||||||||

| Lowest One-Third of States | 8.2 | 6.9 | -15 | 51 | 34 | -33 | 4.2 | 2.4 | -43 |

| Middle One-Third of States | 9.9 | 8.0 | -19 | 59 | 38 | -36 | 5.8 | 3.0 | -48 |

| Highest One-Third of States | 12.0 | 8.9 | -26 | 114 | 63 | -45 | 13.8 | 5.6 | -59 |

| Historic Growth in Spending | |||||||||

| Lowest One-Third of States | 10.1 | 8.2 | -19 | 67 | 42 | -36 | 6.7 | 3.5 | -48 |

| Middle One-Third of States | 9.6 | 7.8 | -19 | 65 | 40 | -39 | 6.3 | 3.1 | -50 |

| Highest One-Third of States | 11.1 | 8.2 | -26 | 114 | 62 | -46 | 12.7 | 5.1 | -60 |

| Census Region | |||||||||

| New England | 12.9 | 10.9 | -16 | 90 | 54 | -40 | 11.7 | 5.9 | -49 |

| Middle Atlantic | 9.7 | 9.0 | -8 | 53 | 37 | -31 | 5.1 | 3.3 | -36 |

| South Atlantic | 10.1 | 8.1 | -20 | 73 | 44 | -39 | 7.3 | 3.6 | -51 |

| East North Central | 9.1 | 7.1 | -21 | 58 | 38 | -35 | 5.3 | 2.7 | -49 |

| East South Central | 12.6 | 8.6 | -31 | 117 | 69 | -41 | 14.7 | 6.0 | -59 |

| West North Central | 8.3 | 6.4 | -23 | 55 | 34 | -38 | 4.6 | 2.2 | -52 |

| West South Central | 12.4 | 8.7 | -30 | 147 | 78 | -47 | 18.2 | 6.8 | -63 |

| Mountain | 8.3 | 6.4 | -23 | 77 | 40 | -48 | 6.4 | 2.6 | -60 |

| Pacific | 9.2 | 7.3 | -21 | 48 | 29 | -39 | 4.4 | 2.1 | -52 |

NOTES: Medicare expenditures used to group States are from Medicare Home Health Agency National State Summary, dated May 26, 2000, and the enrollment data are from the Health Care Financing Administration Web site http://cms.hhs.gov/statistics/enrollment/stenrtrend95_98.asp. Historic growth is based on the percentage change in spending per enrollee between 1990 and 1994.

SOURCE: Komisar, H. L., Georgetown University, 2002.

Among home health users, the drop in average visits per user was remarkably similar—and sizable—for all examined groups, but there were some significant differences by age and sex. The drop in average visits per user increased with age—average visits per user fell by 35 percent for users under age 65, 39 percent for those age 65-74, 42 percent for those age 75-84, and 45 percent for those age 85 or over. Also, females in the two younger age groups (under age 65 and 65-74) experienced steeper declines than males in those groups.

Because the changes in utilization did not vary greatly among demographic groups, the distribution of home health users by characteristics did not undergo a major shift between 1997 and 1999 (Table 2). Among the categories examined the greatest change was among age groups—in 1999, 9.5 percent of home health users were under age 65, compared with 8.7 percent in 1997.

Table 2. Distribution of Home Health Users and Visits, by Characteristics of Users, Fiscal Years 1997 and 1999.

| Characteristic | Distribution of Users | Distribution of Visits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| 1997 | 1999 | 1997 | 1999 | |

|

| ||||

| Percent | ||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Age | ||||

| Under 65 Years | 8.7 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 11.6 |

| 65 Years or Over | 91.3 | 90.5 | 90.4 | 88.4 |

| 65-74 Years | 26.0 | 25.1 | 22.6 | 22.6 |

| 75-84 Years | 40.8 | 40.3 | 39.3 | 38.4 |

| 85 Years or Over | 25.4 | 26.1 | 29.4 | 26.2 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 65.3 | 65.0 | 32.5 | 34.2 |

| Male | 34.7 | 35.0 | 67.5 | 65.8 |

| Sex and Age | ||||

| Female, Under 65 Years | 4.5 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.8 |

| Female, 65-74 Years | 15.7 | 15.1 | 14.5 | 13.9 |

| Female, 75-84 Years | 27.0 | 26.3 | 27.0 | 25.7 |

| Female, 85 Years or Over | 18.5 | 19.2 | 21.6 | 20.8 |

| Male, Under 65 Years | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 5.8 |

| Male, 65-74 Years | 10.3 | 10.0 | 8.1 | 8.7 |

| Male, 75-84 Years | 13.8 | 14.0 | 12.3 | 12.7 |

| Male, 85 Years or Over | 6.9 | 6.9 | 7.9 | 7.4 |

| Medicaid Enrolled | ||||

| Yes | 22.4 | 22.9 | 28.9 | 29.0 |

| No | 77.6 | 77.1 | 71.1 | 71.0 |

| Urban/Rural Location | ||||

| Rural | 27.8 | 27.0 | 30.0 | 28.9 |

| Urban | 72.1 | 72.8 | 69.9 | 70.9 |

SOURCE: Komisar, H. L., Georgetown University, 2002.

Differences Among States and Regions

Enrollees in States with the highest levels of Medicare home health spending per enrollee before the BBA were expected to be disproportionately affected by the BBA. These States had relatively greater proportions of enrollees using a high volume of services and, presumably, using the home health benefit for substantial amounts of personal assistance alongside more skilled care. Research findings suggest that higher levels of use in some States may reflect, among other factors, a relatively greater use of the benefit to assist people with long-term care needs (Cohen and Tumlinson, 1997; Schore, 1995; Kenney and Dubay, 1992; and Kenney, Rajan, and Soscia, 1996). For example, one study found higher Medicare home health use to be associated with a lack of State Medicaid coverage of personal care and with fewer LTC facilities (Cohen and Tumlinson, 1997). The results are consistent with expectations. These States did have greater declines in home health use after the BBA, but in 1999 still had higher rates of use than other States. For example, in the one-third of States with the highest spending before the BBA the average number of visits per enrollee dropped by 59 percent between 1997 and 1999, compared with a drop of 43 percent in the lowest one-third of States (Table 1). But in 1999, the highest-spending States still had a level of use twice as great as the lowest spending States—5.6 visits per enrollee compared with 2.4.7

In addition, it was hypothesized that users in States with the greatest historical growth in home health use would have relatively greater declines in use because agencies in these States might have needed to make greater adjustments to stay within the IPS limits based on 1993-1994 patterns of care. The results indicate that States with the highest rates of growth in Medicare home health spending in the early 1990s, had greater declines in use after the BBA than other States, but the difference in effects among categories is not as pronounced as for the State groupings based on the level of home health spending.8

Census regions with greater use (visits per enrollee) in 1997 generally had greater declines than other regions; however, wide differences among regions persist. (The Mountain region was an exception, with relatively low use, but a large decline.) In 1997, the number of visits per enrollee in the highest-use region, West South Central, was 4 times greater than in the lowest use region, Pacific—18.2 visits per enrollee compared with 4.4. Visits per enrollee dropped more steeply in the West South Central region (63 percent) than the Pacific region (52 percent), but the level of use in the West South Central was still more than 3 times the level in the Pacific region in 1999 (6.8 visits per enrollee compared with 2.1).

Low- and High-Volume Users

After the BBA, there was a substantial drop in the share of users receiving a high volume of visits. The proportion of home health users who received 200 or more visits during the year fell by more than one-half, from 10 percent in 1997 to 4 percent in 1999, and the share of all visits accounted for by these high-volume users dropped from 49 percent to 30 percent (Table 3). At the same time, the share of users receiving less than 10 visits during the year rose from 23 to 30 percent. However, these low-volume users still constituted only a small percentage of visits.

Table 3. Percent Distribution of Home Health Users and Visits, by Number of Visits and Episode Length: Fiscal Years 1997 and 1999.

| Visit and Episode | Distribution of Users | Change in Number of Users1 | Distribution of Visits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| 1997 | 1999 | 1997 | 1999 | ||

|

| |||||

| Percent | |||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | -21 | 100 | 100 |

| Number of Visits | |||||

| 1-4 | 10 | 13 | 7 | (4) | 1 |

| 5-9 | 13 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| 10-49 | 42 | 47 | -11 | 14 | 26 |

| 50-99 | 14 | 12 | -33 | 14 | 19 |

| 100-199 | 11 | 7 | -52 | 21 | 21 |

| 200 or More | 10 | 4 | -70 | 49 | 30 |

| Number of Episodes2 | |||||

| 1 | 90 | 88 | -22 | 90 | 85 |

| 2 | 9 | 11 | -9 | 9 | 14 |

| 3 or More | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Observed Episode Length3 | |||||

| 7 or Less Days | 4 | 6 | 14 | (4) | (4) |

| 8-30 Days | 19 | 29 | 19 | 3 | 7 |

| 31-60 Days | 22 | 25 | -9 | 7 | 14 |

| 61-120 Days | 16 | 16 | -19 | 10 | 16 |

| 121-180 Days | 8 | 7 | -33 | 8 | 10 |

| 181 or More Days | 31 | 17 | -57 | 71 | 53 |

To adjust for change in Medicare enrollment between 1997 and 1999, calculation is based on the estimated number of users in 1997 if enrollment were at 1999 level.

An episode's start and end are each defined by a 60-day gap in home health services. Episodes must overlap with designated year, but need not begin or end within it.

Each user and all of his or her visits in the year are assigned to one category based on the person's longest episode that year. Categories are based on episodes of “known” and “unknown” length. Episodes of known length are those for which the beginning and end are both observed in the data, while episodes of unknown length are those for which the beginning or end (or both) falls outside the data observation period. For each fiscal year, the observation period was from 9 months before the year began to 3 months after the year's end.

Less than 0.5 percent.

SOURCE: Komisar, H. L., Georgetown University, 2002.

Holding Medicare enrollment fixed at the 1999 level, the estimated number of home health users receiving 200 or more visits shrank by 70 percent; in contrast, the number of users receiving less than 10 visits grew by 6 percent. The fall in users with 200 or more visits accounted for about one-third of the overall drop in users between 1997 and 1999 (holding enrollment constant) and about two-thirds of the overall drop in home health visits.

Similarly, the proportion of users with home health episodes lasting at least 6 months (more than 180 days) also fell by nearly one-half, from 31 percent of users in 1997 to 17 percent in 1999. At the same time, the share of users with short episodes (30 days or less) grew from 23 to 35 percent. Holding enrollment constant, the number of users with long episodes (more than 180 days) fell by 57 percent, while the number of users with episodes of 30 days or less grew by 18 percent.

The proportion of users with multiple episodes during the year increased only slightly from 10 percent of home health users in 1997 to 12 percent in 1999. The proportion of visits attributed to people with multiple episodes increased more—from 10 percent of visits in 1997 to 15 percent in 1999. The results suggest that a relatively small number of people may have been discharged earlier from home health in 1999 than they would have been in the pre-BBA period, but resumed home health care again later in the year.

Users with Prior Hospital Stays

Changes in the proportion of home health users who receive home health following a hospital stay provide an indication of shifts in the service needs of home health users. When home health care follows a recent hospital stay, it is often considered an indicator that the person needs post-acute rehabilitative therapy, whereas home health use without a recent hospital stay is considered to be associated with a person having a greater likelihood of long-term personal care needs due to chronic illness or conditions (Leon, Neuman, and Parente, 1997). Patterns of use substantiate this characterization—historically, users without a prior hospital stay have had longer episodes of home health and received a greater proportion of home health aide visits than those with a prior hospital stay.

Following the BBA, there was a striking increase in the percentage of home health users who began home health after a recent hospital stay, rising from 46 percent in 1997 to 56 percent in 1999 (Table 4). Users without a recent hospital stay fell from 39 to 36 percent of users, and those with unknown prior hospital status (because unobserved in the data) fell from 15 to 8 percent of users. Users in the unknown group typically have long home health episodes lasting 6 months or more, and therefore—like users without a prior hospital stay—are relatively more likely to have the chronic conditions and long-term need for personal assistance.

Table 4. Percent Distribution of Home Health Users, by Prior Hospital Stay: Fiscal Years 1997 and 1999.

| Hospital Stay | Distribution of Users | Number of Users | Visits per User | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| 1997 | 1999 | Adjusted 19971 | 1999 | Percent Change | 1997 | 1999 | Percent Change | |

|

| ||||||||

| Percent | In Thousands | |||||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 31.8 | 25.2 | -21 | 79 | 46 | -41 |

| Prior Hospital Stays2 | ||||||||

| Users With3 | 46 | 56 | 14.5 | 14.1 | -3 | 46 | 34 | -26 |

| Users Without | 39 | 36 | 12.5 | 9.0 | -28 | 68 | 39 | -42 |

| Unknown4 | 15 | 8 | 4.8 | 2.1 | -56 | 204 | 156 | -24 |

Estimated number of users in 1997 if enrollment were at 1999 level.

Defined as Medicare-covered inpatient hospital or skilled nursing facility care within 14 days of the beginning of a home health episode, where an episode is defined by a 60-day gap in service (and must overlap with designated year; but need not begin or end within it).

Because home health users with multiple episodes were categorized as having a prior hospital stay if any episode occured after a hospital stay some visits for users with prior hospital stay are not necessarily part of an episode with a recent prior hospital stay.

Unknown indicates users whose prior hospital stay status could not be determined within the data observation period because either the home health episode began more than 6-1/2 months prior to the beginning of the fiscal year, or they were newly eligible for Medicare when they began using Medicare home health.

SOURCE: Komisar, H. L., Georgetown University, 2002.

Holding enrollment constant (at the 1999 level), the estimated number of users with a prior hospital stay fell by only 3 percent over the 2 years, compared with a 28-percent drop for users without a recent prior hospital stay and a 56-percent drop in users with unknown prior hospital stay status. Indeed, only 6 percent of the fall in home health users between 1997 and 1999 (holding enrollment constant at the 1999 level) was due to the fall in users with a recent prior hospital stay while 53 percent of the drop was from the fall in users without a recent hospital stay and 41 percent of the drop was from the fall in users with unknown prior hospital status.

Further, the decrease in average visits per user was also smaller for user without a prior hospital stay (42 percent) than for the group with a recent prior hospital stay (26 percent). However, it was similar to the drop in average visits for the group with unknown prior hospital status (24 percent). Before the BBA, home health users with a prior hospital stay averaged fewer visits than those without a prior hospital stay—46 visits per person during the year, compared with 68 for users without a prior hospital stay. Interestingly, in 1999, the average number of visits per user was only slightly smaller—34 visits for users with a prior hospital stay, compared with 39 visits for those without. In both years, long-stay home health users with unknown prior hospital status averaged by far the greatest number of visits—204 visits per user in 1997 and 156 in 1999.

Shift in Visit Mix

The average number of visits per home health user fell for all but one of the six types of home health visits, but by differing amounts, resulting in a dramatic shift in the mix of visits types. The drop was steepest for home health aide visits, which fell from an average of 38 visits per user in 1997 to 16 visits in 1999, or by 57 percent (Table 5). In contrast, skilled nursing visits fell by 31 percent, from 32 visits per user in 1997 to 22 in 1999. Among other types of visits, occupational therapy and medical social services—which each constituted fewer than 1 percent of visits in each year—fell by 26 and 42 percent, respectively, while physical therapy—constituting about 6 percent of visits each year, fell by only 6 percent. Speech therapy was an exception, with average visits per user rising slightly (3 percent) from 1.04 visits in 1997 to 1.09 in 1999.

Table 5. Average Number and Percent Distribution of Medicare Home Health Visits, by Type: Fiscal Years 1997 and 1999.

| Type of Visit | Average Number of Visits per User | Distribution of Visits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1997 | 1999 | Percent Change | 1997 | 1999 | Difference (in Percentage Points) |

|

|

| ||||||

| Percent | ||||||

| Total | 78.8 | 46.2 | -41 | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| Skilled Nursing | 32.2 | 22.3 | -31 | 40.8 | 48.2 | 7.4 |

| Home Health Aide | 38.4 | 16.4 | -57 | 48.7 | 35.5 | -13.1 |

| Physical Therapy | 6.0 | 5.6 | -6 | 7.6 | 12.2 | 4.6 |

| Speech Therapy | 1.0 | 1.1 | 3 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 1.0 |

| Occupational Therapy | 0.4 | 0.3 | -26 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Medical Social Services | 0.8 | 0.5 | -42 | 1.0 | 1.0 | (1) |

Less than 0.05 percentage points.

SOURCE: Komisar, H. L., Georgetown University, 2002.

As a percentage of all visits, home health aide visits dropped from 49 percent in 1997 to 36 percent in 1999, while skilled nursing visits rose from 41 to 48 percent and other visit types combined rose from 10 to 16 percent. The shift away from aide visits and toward a more skilled mix is consistent with the changes in the composition of users—specifically, the shift toward users receiving fewer visits per year and users with prior hospital stays, since both of these groups have historically used proportionately fewer aide visits. The increasing share of other types of visits—mainly physical therapy—might reflect a relative increase in some categories of users. In particular, agencies might have shifted their patient mix toward a greater proportion of clients needing short-term, rehabilitative care. This is consistent with the incentives of IPS, which encourage agencies to serve enrollees needing relatively fewer visits in order to stay under the per beneficiary limits. In addition, agencies may have altered their ways of treating clients, by providing a different mix of services. For example, some agencies reported using relatively more physical and occupational therapy visits, while decreasing visits overall, in order to help patients achieve maximum functioning with fewer total visits or to help patient prepare for discontinuation of home health (Rogers and Komisar, 2002).

Notably, the post-BBA distribution of visits by skill mix is quite different than the base year (1993-1994) for the IPS's per-beneficiary limits. Indeed, the visit mix in (calendar year) 1994 was almost identical to that in 1997 (Figure 2). Looking over the historical trend, the post-BBA mix of visits resembles most closely the pattern in (calendar year) 1988, before the expansion in eligibility criteria. In calendar year 1988, 34 percent of visits were home health aide visits (compared with 36 percent in 1999). The share jumped up rapidly after the 1989 broadening of eligibility rules to 41 percent in 1990. Even the proportion of visits that are for therapy or medical social services (other types) in 1999 is similar to the (calendar year) 1988 share—16 compared with 15 percent—suggesting that the 1999 pattern might more likely reflect the mix of patients than new strategies or innovations in home health practice.

Figure 2. Percent Distribution of Home Health Visits, by Type: Selected Years, 1988-1999.

Differences Among Home Health Users

Age is the main demographic characteristic associated with a relatively larger decline in the proportion of visits that were for aide services (Table 6). For home health users over age 85, the proportion of visits that were aide visits dropped from 55 percent in 1997 to 40 percent in 1999, a drop of 15 percentage points. In contrast, for users age 65-74, the proportion shifted from 42 percent to 31 percent, a drop of 11 percentage points. For users under age 65, or between 75-84, the proportion dropped by 13 percentage points.

Table 6. Percent Distribution of Medicare Home Health Visits, by Type and Characteristics of Users: Fiscal Years 1997 and 1999.

| Characteristic | Skilled Nursing Visits | Home Health Aide Visits | Other Types of Visits | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| 1997 | 1999 | Difference (in Percentage Points) |

1997 | 1999 | Difference (in Percentage Points) |

1997 | 1999 | Difference (in Percentage Points) |

|

| Total | 41 | 48 | 7 | 49 | 36 | -13 | 10 | 16 | 6 |

| Age | |||||||||

| Under 65 Years | 45 | 55 | 9 | 46 | 33 | -13 | 9 | 12 | 3 |

| 65-74 Years | 46 | 52 | 6 | 42 | 31 | -11 | 12 | 17 | 5 |

| 75-84 Years | 41 | 47 | 7 | 48 | 35 | -13 | 11 | 17 | 6 |

| 85 Years or Over | 36 | 44 | 8 | 55 | 40 | -15 | 9 | 16 | 7 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 40 | 47 | 7 | 50 | 36 | -13 | 10 | 16 | 6 |

| Male | 42 | 50 | 8 | 48 | 34 | -13 | 11 | 16 | 5 |

| Medicaid Enrolled | |||||||||

| Yes | 43 | 53 | 10 | 50 | 36 | -14 | 7 | 11 | 4 |

| No | 40 | 46 | 6 | 48 | 36 | -13 | 12 | 18 | 7 |

| Urban/Rural Location | |||||||||

| Rural | 39 | 47 | 8 | 54 | 40 | -14 | 8 | 13 | 5 |

| Urban | 42 | 49 | 7 | 47 | 34 | -13 | 12 | 18 | 6 |

| Prior Hospital Stay1 | |||||||||

| Users With | 46 | 49 | 3 | 34 | 27 | -8 | 20 | 24 | 4 |

| Users Without | 45 | 52 | 7 | 44 | 31 | -14 | 11 | 17 | 6 |

| Unknown | 34 | 43 | 9 | 62 | 53 | -9 | 4 | 4 | (2) |

| Spending per Enrollee in 1996 | |||||||||

| Lowest One-Third of States | 43 | 47 | 4 | 43 | 34 | -9 | 13 | 18 | 5 |

| Middle One-Third of States | 46 | 52 | 6 | 40 | 27 | -12 | 15 | 21 | 6 |

| Highest One-Third of States | 38 | 46 | 9 | 54 | 41 | -13 | 8 | 12 | 5 |

| Historic Growth in Spending | |||||||||

| Lowest One-Third of States | 43 | 49 | 6 | 44 | 33 | -12 | 12 | 18 | 6 |

| Middle One-Third of States | 43 | 49 | 6 | 44 | 32 | -12 | 13 | 19 | 6 |

| Highest One-Third of States | 37 | 46 | 9 | 55 | 42 | -13 | 7 | 12 | 4 |

| Census Region | |||||||||

| New England | 32 | 39 | 7 | 59 | 48 | -11 | 10 | 14 | 4 |

| Middle Atlantic | 45 | 48 | 3 | 42 | 35 | -8 | 13 | 18 | 4 |

| South Atlantic | 43 | 50 | 7 | 45 | 31 | -14 | 12 | 20 | 7 |

| East North Central | 45 | 50 | 5 | 40 | 28 | -11 | 16 | 22 | 6 |

| East South Central | 35 | 44 | 9 | 58 | 42 | -16 | 7 | 14 | 7 |

| West North Central | 45 | 50 | 5 | 44 | 33 | -11 | 11 | 17 | 6 |

| West South Central | 39 | 49 | 10 | 56 | 43 | -13 | 5 | 8 | 3 |

| Mountain | 39 | 45 | 6 | 47 | 32 | -15 | 14 | 22 | 9 |

| Pacific | 53 | 61 | 8 | 31 | 20 | -11 | 16 | 19 | 3 |

Prior hospital stay is defined as Medicare-covered inpatient hospital or skilled nursing facility care within 14 days of the beginning of a home health episode, where an episode is defined by a 60-day gap in service (and must overlap with designated year; but need not begin or end within it). Unknown indicates that prior hospital stay status could not be determined within the data observation period.

Less than 0.5 percentage points.

NOTES: Because of rounding, reported difference may not equal the difference between reported 1997 and 1999 amounts. Medicare expenditures used to group States are from Medicare Home Health Agency National State Summary, dated May 26, 2000, and the enrollment data are from the Health Care Financing Administration Web site http://cms.hhs.gov/statistics/enrollment/stenrtrend95_98.asp. Historic growth is based on the percentage change in spending per enrollee between 1990 and 1994.

SOURCE: Komisar, H. L., Georgetown University, 2002.

Although for both users with prior hospital stays and those without, home health aide visits played a smaller role after the BBA, the shift was considerably more pronounced for users without a prior hospital. For users with recent hospital stays, home health aide visits declined from 34 percent of all visits to 27 percent, a drop of 8 percentage points.9 In contrast, for home health users without a recent prior hospital stay, aide visits fell from 44 percent of all visits to 31 percent, a drop of 14 percentage points. The shift was not as large for the typically long-stay users with unknown prior hospital stay status; for this group, home health aide visits still constituted over one-half of all visits (53 percent) in 1999, having fallen from 62 percent in 1997, or by 9 percentage points.

Users in States with historically higher Medicare home health spending received larger shares of home health aide visits before the BBA and experienced the greatest declines after the BBA. Still, after the BBA the higher spending States had a greater share of aide visits compared with other States. For example, among the one-third of States with the highest home health spending per enrollee, 54 percent of visits were aide visits in 1997, compared with 43 percent for the one-third of States with the lowest spending. After the BBA the share for the highest States had dropped to 41 percent (a drop of 13 percentage points), while that for the lowest one-third of States was 34 percent (a drop of 9 percentage points).

In contrast, among State groupings based on historical rates of growth in home health, there was little difference in the shift in visit mix. Although the highest one-third of States had a greater share of aide visits than other groups (55 percent in 1997, compared with 44 percent in the two other groups), the shift away from aide visits was similar among the three groups.

Low- and High-Volume Users

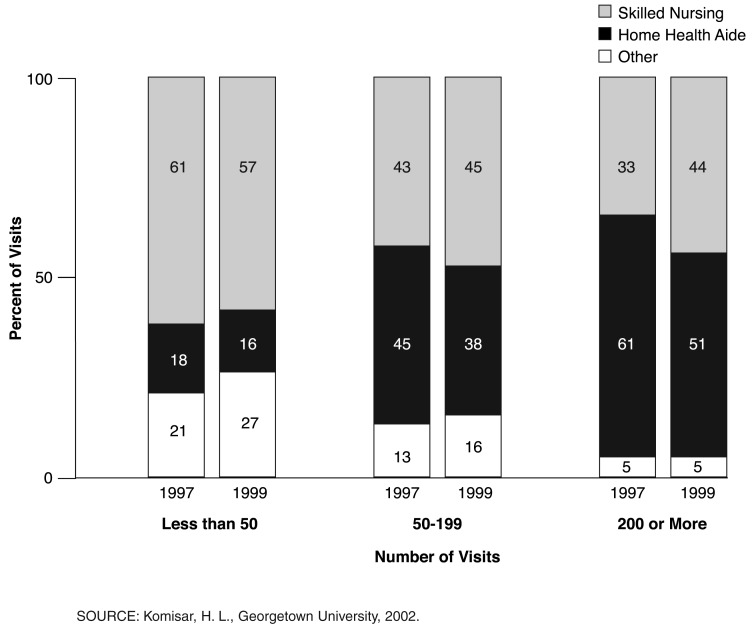

Because high-volume home health users receive, on average, a greater share of home health aide visits than other users, the drop in these high-volume users contributed to the overall shift in visit mix, but it was not the sole cause of the shift. Instead, the visit mix shifted away from aide visits for all levels of use, measured in annual visits or episode length.

However, patterns differed for low- and high-volume home health users. For low-volume users (those receiving fewer than 50 visits during the year) the mix of visits shifted away from both aide visits and skilled nursing visits to other types—therapy and social services (Figure 3). For low-volume users, aide visits declined from 18 to 16 percent of total visits, and skilled nursing visits from 61 to 57 percent, while other types grew from 21 to 27 percent of the total. In contrast, among high-volume users (those receiving 200 visits or more during the year), the mix of visits shifted away from aide visits—dropping from 61 to 51 percent of all visits—toward skilled nursing visits, which increased from 33 to 44 percent of the total. The use of other types was similar in both years, constituting 5 percent of total visits. The patterns are similar for relatively shorter (60 days or less) and longer (181 days or more) episodes, respectively.

Figure 3. Percent Distribution of Home Health Visits, by Type and Categories of Users: Fiscal Years 1997 and 1999.

Discussion

In the BBA, Congress sought to constrain the volume of home health services by changing the financial incentives of agencies, initially with the IPS and most recently with the PPS. This article examines the time period of the IPS, which both placed new limits on the average payments agencies could receive for each Medicare enrollee they served and tightened existing limits on agencies' average payments per visit. Although the IPS was clearly an important driver of the outcomes examined here, the results also reflect the other policy changes occurring during the same time period, which narrowed the eligibility rules for home health and enhanced efforts to deter fraud. A limitation of the analysis is that it cannot isolate the separate effects of the various concurrent policies.

Between FYs 1997 and 1999, the changes enacted in the BBA did much more than halt the benefit's decade-long growth streak—they resulted in a steep fall in home health use and spending. In 1999—the first year in which the new payment rules covered all home health services—the number of visits per Medicare enrollee was less than one-half of what it was in 1997, the year before the BBA became effective. Similarly, Medicare's home health spending per enrollee in 1999, adjusted for general inflation—was less than one-half the 1997 level. The share of enrollees using the benefit during a year fell by one-fifth, and, among home health recipients, the average number of visits fell by two-fifths. Although these drops are dramatic, it is not known whether they are appropriate within the scope of Medicare's benefit.

These declines have brought home health use back to levels of the early 1990s. Compared with historical trends, the proportion of enrollees using home health in 1999 was similar to the level in 1993, the average number of visits per user in 1999 was at the same level as in 1991, and the average number of visits per enrollee was the same as in 1992. The decline in visits per user to the 1991 level might reflect the fact that the per-beneficiary limits incorporated only a partial adjustment for the inflation in input costs that occurred after the base year, combined perhaps with the uncertainties of agencies as they encountered the new payment limits (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2000b). Medicare's home health spending per enrollee in 1999 was similar to the 1992 level (adjusted for general inflation).

The patterns among examined enrollee groups confirm expectations that groups who previously used extensive home health might have experienced difficulty obtaining services after the BBA The results are also consistent with the findings of several studies of the effects of IPS, based on surveys of HHA administrators, hospital discharge planners, and aging service providers, which indicated that beneficiaries with complex or intensive needs were likely to encounter more problems obtaining care under the IPS (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1998; Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 1999; Office of the Inspector General, 1999; Smith and Rosenbaum, 1998). The largest declines in users occurred for some population groups that had relatively high visits per user prior to the BBA—enrollees age 75 or over, low-income enrollees who were also covered by Medicaid, and enrollees in rural areas. Over one-half (53 percent) of the drop in users was attributable to those who began home health care without a recent prior hospital stay—a group considered more likely to have long-term chronic conditions and personal care needs. Another 41 percent of the drop in users was due to the fall in users whose prior hospital stay status was unobserved (primarily because their home health episode began at least 6 months before the beginning of the FY), another group likely to have long-term chronic and personal care needs.

Among home health users, the drop in the average number of visits was substantial for all examined groups. The share of home health users receiving a high-volume of visits shrunk markedly. Users receiving 200 visits or more during the year fell from 10 percent of all users in 1997 to 4 percent in 1999, while low-volume users receiving less than 10 visits rose from 23 percent of users to 30 percent.

A major shift in the skill mix of visits after the BBA, along with the other changes in patterns of use, indicates that the benefit has returned to a greater emphasis on post-acute and rehabilitative services. The 1999 distribution of visits by type was nearly the same as more than 10 years earlier, in 1988, before the period of rapid expansion in the benefit's use. The shift in visit mix after the BBA included not only a reduction in the proportion of aide visits relative to skilled nursing visits, but also an increase in the share of visits for therapy and medical social services. These other types of visits increased from 10 percent of all visits in 1997 to 16 percent in 1999, nearly the same as their 15 percent share in 1988. The shift in skill mix away from aide visits was more pronounced for some groups considered more likely to have used home health to assist with extensive personal care needs: Home health users age 85 or over; users receiving a high volume of visits (200 or more) in a year; and users in States with historically higher Medicare home health spending.

The changes in patterns of the benefit's use raise the question of whether people who previously relied on the benefit shifted to other sources of support. Although many observers argue that before the BBA the benefit covered care that should have been outside Medicare's scope—specifically, personal care for those with chronic conditions—this care was likely meaningful for its recipients. Some Medicare enrollees who would previously have used the benefit are not using it at all; others are receiving far fewer visits and are being discharged earlier.

No studies of which we are aware have examined how Medicare beneficiaries who previously would have received, or received more, Medicare home health are arranging their care in the post-BBA period. Some beneficiaries with low incomes may have obtained support from Medicaid or other State Programs. In 1997, 22 percent of Medicare home health users were also enrolled in Medicaid (Table 2). However, one study concluded that the increases in national Medicaid home care spending between 1996 and 2000 were not likely a response to the decline in Medicare home health use because the majority of the rise during this period was attributable to Medicaid waiver services for which Medicare enrollees were not typically eligible (Laguna Research Associates, 2002).

However, for the majority of Medicare enrollees who are not eligible for Medicaid, the primary alternatives to Medicare home health are out-of-pocket purchase of services or reliance on family members, who, even if available, may not have the skills or training to substitute for professional HHA employees. Some beneficiaries may have elected to use Medicare's hospice benefit (Rogers and Komisar, 2002). Other enrollees might have opted for institutional care if they were unable to meet their needs at home, but we are not aware of any published studies that provide empirical evidence of this.

The results of this study demonstrate that the home health industry was highly responsive to changes in its financial incentives, suggesting that we may again see large shifts in patterns of care as HHAs adjust to the new incentives of the PPS. Under the PPS, beginning in October 2000, Medicare pays agencies a set amount for each 60-day episode of care (consisting of 5 visits or more), adjusted for the patient's case-mix classification. The case-mix adjustment enables agencies to provide more services to patients with greater needs, and therefore agencies might be less reluctant than under IPS to accept patients with extensive needs. The PPS gives agencies an incentive to increase the number of episodes of care they provide, which could be achieved by expanding the number of enrollees served or by providing multiple 60-day episodes to current patients. However, the PPS also provides a financial incentive for agencies to limit the services they provide within each episode (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2000b). Evidence from the first year of the PPS underscores this concern—a U.S. General Accounting Office (2002) study found that after the PPS became effective, HHAs reduced the average number of visits they provided in each episode. Some agencies may be able to control visits and costs by providing care more efficiently, but others might be underserving Medicare patients. In part because of concerns that Medicare could be overpaying some agencies relative to costs, the U.S. General Accounting Office (2002) has recommended that the PPS be modified to add a mechanism to limit the amount a HHA could gain or lose annually under the PPS, by comparing the agency's actual costs with its payment at the close of the year.

The PPS has the potential to stimulate new and creative ways to address patients' needs by giving agencies the flexibility, and financial incentive, to adjust their use of staff and technology to improve productivity and enhance patient care. However, the PPS will not necessarily promote an adequate level or quality of service. Limited knowledge of how home health care affects patient outcomes and a lack of standards for appropriate care make it difficult to assess the effects of payment policy on the care Medicare enrollees receive. Progress in these areas could contribute mightily to achieving the goals of efficient service delivery and appropriate home health services for Medicare enrollees as the PPS matures.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Nelda McCall and Jodi Korb for their many contributions to this research; Judith Feder and Susan Rogers for their valuable comments; Stanley Moore for programming and other support; and Andrew Petersons and Donald Jones for their research support.

Footnotes

Harriet L. Komisar is with Georgetown University. The research for this article was supported under HCFA Contract Number HCFA-00-0108, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, through the Home Care Research Initiative at the Center for Home Care Policy and Research of the Visiting Nurse Service of New York. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Georgetown University or the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

A need for occupational therapy cannot be used to establish eligibility initially, but Medicare will continue to cover home health for beneficiaries who require occupational therapy.

Data are available from the author upon request.

Author's calculation based on data from (Health Care Financing Administration, 1998; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2001). Program payments exclude Medicare enrollees' cost-sharing amounts.

The modifications based the per-visit limits on 105 percent of median national cost for each type of visit (instead of 112 percent of the mean cost). Additionally, the limits were lowered to recapture the savings from a 2-year freeze on updates to the limits that ended in July 1996.

Payment limits were modified by the Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act of 1999, Public Law 105-277, and the Medicare, Medicaid, and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999, Public Law 106-113 (U.S. General Accounting Office, April 2000a; Federal Register, July 2000).

The Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999, delayed the reduction until 12 months after the implementation of the PPS; and the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Benefits Improvement and Protection Act of 2000, Public Law 106-554, delayed it an additional year.

State rankings based on home health spending per enrollee in 1996 are available on request from the author.

State rankings based on growth in home health spending per enrollee between 1990 and 1994 are available upon request from the author.

Because of rounding, the reported difference may not equal the difference between the reported 1997 and 1999 amounts.

Reprint Requests: Harriet L. Komisar, Ph.D., Institute for Health Care Research and Policy, Georgetown University, 2233 Wisconsin Avenue, NW, Number 525, Washington, DC. 20007. E-mail: komisarh@georgetown.edu

References

- Bishop C, Skwara KC. Recent Growth of Medicare Home Health. Health Affairs. 1993 Fall;12(3):95–110. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.3.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Tumlinson A. Understanding State Variation in Medicare Home Health Care: The Impact of Medicaid Program Characteristics, State Policy and Provider Attributes. Medical Care. 1997 Jun;35(6):618–633. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199706000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan v. Bowen, U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Number 87-0383, August 1, 1988.

- Federal Register. Medicare Program; Update to the Prospective Payment System for Home Health Agencies for FY 2003. 2002 Jun 28;67(125):43616–43629. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. Medicare Program; Prospective Payment System for Home Health Agencies; Final Rule. 2000 Jul 3;65FR(128):41127–41214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. Medicare Program; Schedules of Per-Visit and Per-Beneficiary Limitations on Home Health Agency Costs for Cost Reporting Periods Beginning On or After October 1, 1998; Notice. 1998 Aug 11;63(154):42911–42938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldesman W. Dictionary of Eldercare Terminology. United Seniors Health Cooperative; Washington, DC.: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Financing Administration. A Profile of Medicare Home Health Chart Book. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: Aug, 1999. HCFA Pub. No. 10138. [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Financing Administration. Health Care Financing Review, Statistical Supplement, 1998. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Financing Administration. Medicare Home Health Agency Manual: Transmittal No 222. Washington, DC.: Apr, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney G, Dubay LC. Explaining Area Variation in the Use of Medicare Home Health Services. Medical Care. 1992 Jan;30(1):43–57. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney G, Moon M. Reining in the Growth in Home Health Services Under Medicare. The Commonwealth Fund; New York, NY.: May, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney G, Rajan S, Soscia S. Interactions Between the Medicare and Medicaid Home Programs: Insights from States. The Urban Institute; Washington, DC.: Nov, 1996. Publication Number 6523-003. [Google Scholar]

- Komisar HL, Feder J. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997: Effects on Medicare's Home Health Benefit and Beneficiaries Who Need Long-Term Care. The Commonwealth Fund; New York, NY.: Feb, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Laguna Research Associates. Direct and Indirect Effects of the Changes in Home Health Policy as Mandated by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Laguna Research Associates; San Francisco, CA.: May, 2002. Final Report to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Leon J, Neuman P, Parente S. Understanding the Growth in Medicare's Home Health Expenditures. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Washington, DC.: Jun, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin Group. Implications of the Medicare Home Health Interim Payment System of the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. National Association for Home Care; Washington, DC.: Mar, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McCall N, Komisar HL, Petersons A, Moore S. Medicare Home Health Before and After the BBA. Health Affairs. 2001 May-Jun;20(3):189–198. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Selected Medicare Issues. Washington, DC.: Jun, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Inspector General. Medicare Beneficiary Access to Home Health Agencies. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC.: Oct, 1999. Publication No. OEI-02-99-00530. [Google Scholar]

- Price R. Medicare's Home Health Benefit. Congressional Research Service; Washington, DC.: Mar 11, 1996. 95-1009 EPW. [Google Scholar]

- Prospective Payment Assessment Commission. Report and Recommendations to the Congress. Washington, DC.: Mar 1, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S, Komisar H. Effects of the Balanced Budget Act on Medicare Home Health Agencies, Services, and Clients: Findings from Interviews with Home Care Associations and Agencies. Institute for Health Care Research and Policy, Georgetown University; Washington, DC.: Jun, 2002. Final Report to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Google Scholar]

- Schore J. Regional Variation in the Use of Medicare Home Health Services. In: Weiner JM, Clauser SB, Kenell DL, editors. Persons with Disabilities: Issues in Health Care Financing and Service Delivery. Brookings Institution; Washington, DC.: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Smith BM, Rosenbaum S. Medicare Home Health Services: An Analysis of the Implications of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 for Access and Quality. The Center for Health Policy Research, George Washington University; Washington, DC.: Mar, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2001. Consumer Price Index-All Urban Consumers, All Items. ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/cpi/cpiai.txt. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Medicare Home Health Care: Payments to Home Health Agencies Are Considerably Higher than Costs. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: May, 2002. GAO-02-663. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Medicare Home Health: Prospective Payment System Will Need Refinement as Data Become Available. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: Apr, 2000a. GAO/HEHS-00-19. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Medicare Home Health: Prospective Payment System Could Reverse Declines in Spending. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: Sep, 2000b. GAO/HEHS-00-176. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Overpayments are Hard to Identify and Even Harder to Collect. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: Apr, 2000c. GAO/HEHS-00-132. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Medicare Home Health Benefit: Impact of Interim Payment System and Agency Closures on Access to Services. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: Sep, 1998. GAO/HEHS-98-238. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Medicare: Home Health Utilization Expands While Program Controls Deteriorate. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: Mar, 1996. GAO/HEHS-96-16. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. House of Representatives. Balanced Budget Act of 1997: Conference Report to Accompany HR 2015. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: 1997. Report 105-217. [Google Scholar]