Abstract

In October 1998, the definition of a transfer in Medicare's hospital prospective payment system was expanded to include several post-acute care (PAC) providers in 10 high-volume PAC diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). In this methodological article, the authors respond to a congressional mandate to consider more DRGs in the definition. Empirical results support expansion to many more DRGs that are split in ways that understate total PAC volumes, including 25 DRG pairs (with/without complications) and DRG bundles (e.g., infections) that together exhibit high PAC volumes. By contrast, some DRGs (e.g., craniotomy) are questionable PAC candidates because of their heterogeneous procedure mix.

Introduction

Prior to the enactment of the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997, the only cases designated as transfers under Medicare's inpatient hospital prospective payment system (PPS) were those discharged from one acute care facility and readmitted to a similar facility on the same day. Under the current acute-to-acute transfer payment policy, the sending hospital is paid twice the DRG per diem amount for the first day and the per diem for all remaining days up to the full DRG payment amount. The final discharging hospital still receives the full DRG payment amount (Prospective Payment Assessment Commission, 1993). The transfer payment policy was based on the belief that it was inappropriate to pay the sending hospital the full DRG payment for less than the full course of treatment (Buczko, 1993).

Growth in PAC

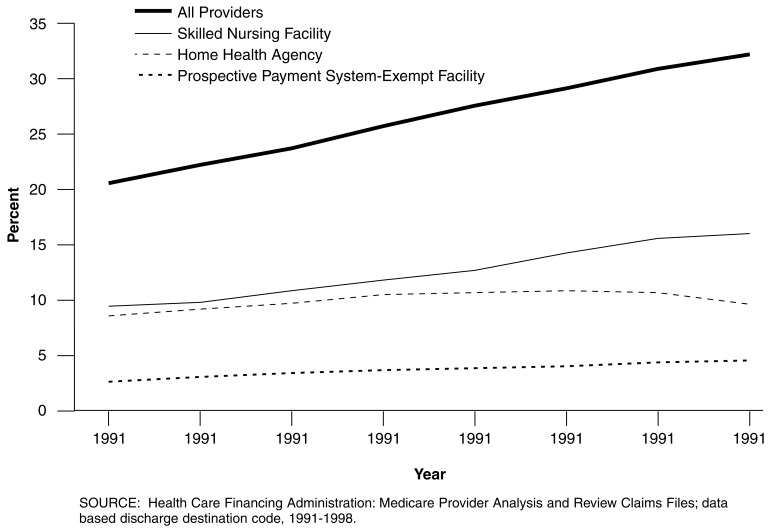

Fundamental changes in the health care market over the past decade have caused health policy analysts to rethink the traditional distinction between acute and PAC services (Lee, Ellis, and Merrill, 1996). An increase in the number of PAC providers, as well as technological advances in medicine, have enabled these providers to treat a wider range and severity of conditions, thereby permitting patients to be discharged earlier from acute care hospitals (Schneider, Cromwell, and McGuire, 1993; Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 1998; Federal Register, 1998b). Figure 1 tracks the share of Medicare patients discharged from an acute care hospital to a PAC provider, defined as a skilled nursing facility (SNF), home health agency, or facility exempted from PPS reimbursement. PAC transfer rates rose steadily during the 1990s, from 20.5 percent in 1991 to 30.2 percent in 1998 (Gilman et al., 2000). A 10-percentage point increase translates into 1 million more Medicare patients annually receiving PAC services after discharge. The percent increase in the 20 DRGs with the highest PAC rates in 1991 was even greater, i.e., 38 to 54 percent (Gilman et al., 2000).

Figure 1. Share of Medicare Post-Acute Care Transfers, by Provider Type: 1991-1998.

Reimbursing acute care hospitals for short-stay patients transferred to PAC can be justified on the same grounds as acute-to-acute transfers. When PPS standardized amounts were first constructed in 1983, they were based on much longer stays and far lower PAC rates. Costs for services that were originally being incurred by hospitals are now being incurred by PAC providers that bill Medicare for their services. The program often pays twice for the PAC-level care previously provided on an inpatient basis.

Because annual recalibration of DRG relative weights supposedly captures shifts in site of care through lower inpatient charges, any transfer payment policy focused on PAC may seem redundant. Annual recalibration, however, does not automatically reduce payments for either acute-to-acute or PAC-related transfers. Greater reliance today on PAC is found in practically all DRGs, but any diffused PAC effect is factored out of payment updates by normalization of the annual DRG relative charges per case. More significantly, PAC transfers under current policy are weighted by the ratio of their acute lengths of stay (LOS) to the DRG geometric mean stay before being included in the denominator of CMS's calculation of the charges per discharge. The effect is to raise average charges for PAC discharges in order to ensure that non-transfer discharges receive an actuarially fair DRG full payment.

Description of PAC Transfer Policy

In 1997, Congress responded to the burgeoning PAC utilization and possible double payment by directing HCFA to identify 10 DRGs to test the feasibility of extending the PPS acute care transfer payment policy to include transfers to PAC settings. BBA 1997, section 1886(d)(5)(J) required the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to select 10 DRGs “…based upon a high volume of discharges classified within such group and a disproportionate use of…” certain post-discharge services (Federal Register, 1998b). The act then defined a qualified post-acute discharge as one where the patient was transferred to a non-PPS hospital or SNF within 1 day or received home health services for care related to the acute admission within 3 days of discharge.

HCFA staff put into operation the congressional mandate in two steps. First, all DRGs in 1996 were ranked in terms of the total number of Medicare PAC discharges and the top 20 DRGs were identified. Second, staff “…considered the volume and percentage of discharges to post-acute care that occurred before the mean length of stay and whether the discharges occurring early in the stay were more likely to receive post-acute care…” (Federal Register, 1998b). Staff then selected the top nine DRGs with more than 14,000 PAC discharges, plus a tenth, uncomplicated, low-volume DRG related to its longer complicated companion DRG. All 10 had very high rates of short-stay PAC discharges.

Current Medicare policy for 7 of the 10 PAC DRGs pays double per diems to the hospital on the first day of inpatient hospitalization and single per diems on each subsequent day until full DRG reimbursement is reached. The DRG-specific per diem is calculated using the hospital payment rate and the national geometric mean LOS. For three DRGs (209, 210, 211) where this payment methodology failed to cover their average costs, CMS pays hospitals one-half the full DRG amount plus a full per diem on the first day, and one-half the per diem for each additional day up to the full DRG amount. Although the transfer policy applies to all PAC transfer cases in the 10 DRGs, hospitals effectively are paid on a per diem basis only for patients discharged to PAC at least 1 day short of the national geometric mean LOS (refer to Technical Note).

The payment policy change went into effect on October 1, 1998, and applies only to inpatient acute facilities. Initial simulations of program savings in the 10 DRGs from per diem payments were $276 million over the first half of FY 1999 (Gilman et al., 2000). This estimate is considerably higher than that of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission's (MedPAC) (2000), primarily because commission staff did not take into consideration the lagged decline in the geometric mean LOS that narrowed the count of short-stay patients. Ex ante savings for an unchanged geometric mean LOS are considerably larger. Responses of acute and PAC providers to the payment change were minimal over the first 6 months after the policy was implemented (Gilman et al., 2000). PAC providers have also experienced dramatic changes in their Medicare payment systems in the last decade. Whether these changes will have any feedback effect on hospital PAC transfers is beyond the scope of this article.

Organization of this Study

This methodological article addresses the question raised by Congress in the BBA of whether the PAC transfer policy should be extended to more, or even to all, DRGs. By including more DRGs in the policy, the government could recover part of the financial gains hospitals have enjoyed by discharging patients early and shifting services to post-acute providers. We begin the analysis with a methodological discussion of the criteria used to identify candidate DRGs. We also raise serious questions about the wisdom of using individual DRGs as the unit of analysis, noting problems arising from DRG fractionation and heterogeneity. Next, we describe our Medicare claims database. Empirical results first compare the PAC rates of the current 10 transfer DRGs adopted by HCFA with 13 additional DRGs identified by HCFA and MedPAC for future consideration. Two subsequent empirical sections address the problem of using aggregate DRG counts of PAC discharges as the initial selection criterion by studying all DRG complication pairs and bundles of treatment-related DRGs. A final empirical section examines the pitfalls in extending the PAC transfer policy to heterogeneous procedure DRGs with bimodal LOS distributions. A concluding discussion section summarizes the results as well as presenting administrative arguments for and against expanding the PAC transfer policy to more DRGs.

Methodology

Issues

Our approach to identifying candidate DRGs for expansion of the PAC transfer policy under acute inpatient prospective payment is presented in two parts. First, we expand the set of criteria used by HCFA staff in selecting the first 10 DRGs. Next, we critique the focus on individual DRGs and how it results in false-negative and false-positive selection errors, either because DRGs are too fractionated or are too heterogeneous by themselves for targeted implementation of the new transfer policy.

Selection Criteria

As a first step in identifying DRGs for expansion, we reconsidered HCFA's two-step approach of selecting DRGs with unusually high short-stay PAC rates within the set of high PAC DRGs. HCFA strategy targeted DRGs with large numbers of patients discharged to PAC earlier than expected, given their higher severity and the need for followup PAC. Highly skewed LOS distributions, however, could naturally generate many short-stay PAC (SPAC) discharges without any serious site-of-care substitution problem. Hence, we construct a companion ratio to the SPAC discharge rate, SPAC/SLOS, that standardizes for the total number of short LOS (SLOS) discharges. This indicator highlights DRGs with unusually high numbers of PAC transfers among just short-stay discharges.

Of course, some DRGs have high PAC discharge rates because of the nature and/or severity of the illness and inpatient procedures performed, e.g., major joint surgery. The PAC rate among all long LOS (LLOS) patients, LPAC/LLOS, should be a good proxy for the general severity level in a DRG as long-stay patients discharged to PAC are likely quite ill. The relative odds (RELODD) of short- versus long-stay PAC patients is a quick way of controlling for overall high severity levels within DRGs, i.e., RELODD = (SPAC/SLOS)/(LPAC/LLOS). We would expect PAC transfers to be far less frequent for shorter- versus longer-stay patients because short-stay patients should be healthier upon discharge (unless their acute stays have been truncated). Consequently, DRGs with particularly high odds ratios, we argue, have unusually high short-stay PAC rates that merit attention.

Consider as well the dynamic implications of PAC growth. Within DRGs over time, inpatients are sicker on average, yet stay fewer days in the acute facility, and use PAC more often. This is strong circumstantial evidence of a feedback effect of PAC referrals shortening inpatient LOS. DRGs exhibiting significant increases in the PAC discharge rate, coupled with declining average LOS, are likely undergoing extraordinary rates of site substitution of care (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 1998). We analyzed the growth in PAC use from 1994 to 1996 and displayed DRGs with particularly high overall PAC discharge rates of change, e.g., coronary bypasses.

Rapid increases in short-stay PAC discharges may be even more indicative of high rates of site substitution, while increases in the relative odds of short- versus long-stay PAC rates may be the single best indicator of site shifts in care, as it controls for PAC growth among long-stay patients.

Even with these more refined indicators, it should be clear that no single measure completely captures site-of-care substitution. Moreover, because the criteria are continuous, no unique cutoff threshold exists to single out ideal candidates. The best we can do is to array DRGs by the set of indicators and highlight those most likely to be experiencing unusually high site-of-care substitution.

Fractionated and Heterogeneous DRGs

To initiate the PAC transfer policy, Congress focused on 10 high-volume DRGs, allowing HCFA time to identify other candidates using alternative selection criteria. Emphasizing only total PAC volumes and rates, however, does not take into consideration the fact that many DRGs are fractionated. To avoid ignoring excellent but small-volume candidates (false negatives), it is necessary to go beyond single DRGs and put together DRGs with a common clinical factor that determines PAC needs.

DRGs are fractionated in several ways. Many appear in pairs stratified by complications and age. HCFA staff did include both DRGs 263 and 264, skin graft for skin ulcer with and without complications, out of concern for biasing hospital coding of cases to maximize payments (refer to Technical Note.) Extending their analysis, we identified and constructed PAC rates for the top 25 complication pairs based on their combined PAC volume. We then examined their suitability for the transfer policy using the expanded set of criteria.

Other stratifiers that distinguish DRGs in potentially misleading ways include the presence of trauma, length of coma, infections, angioplasty, heart attack, complex diagnosis or procedure, use of laparoscope, malignancy, major or minor procedure, type of skin graft and location of fracture, e.g., thumb versus other hand or wrist procedures. As we show later, it is often one of these qualifying characteristics of the DRG that determines the PAC rate. To avoid overlooking DRGs because they exhibit low PAC volumes by themselves yet have an underlying PAC-intensive characteristic in common, we first ranked all DRGs by their short-stay PAC rates. Next, we searched the top 100 DRGs for recurring characteristics (e.g., infections, fractures) that likely require greater PAC care. Finally, we assembled super-DRG bundles of clinically related DRGs, constructed overall PAC rates for each bundle, and then compared them with HCFA's 10 original DRGs. In effect, fractures, infections, etc., become the units of analysis for comparison purposes.

In identifying short-stay PAC patients appropriate for per diem payment, DRGs not only may be too narrow a unit of analysis due to fractionated DRGs, they can also be too broad in harboring heterogeneous patients and/or procedures. The PAC transfer policy implicitly treats a PAC destination code as a potential indicator of a truncated stay. It assumes that any short-stay patient actually discharged to PAC is sicker (upon discharge) than other short-stay patients not requiring PAC. Therefore, any short-stay PAC patient may constitute a premature discharge. Yet, if patients in the same DRG are undergoing very different procedures requiring very different LOS, the sensitivity and specificity of the PAC indicator can be low. It can be insensitive in not identifying early PAC discharges of patients undergoing the more complicated, longer stay procedures (false negatives). It can also be unspecific in calling for per diem payment for longer-stay patients undergoing a simpler, shorter-stay procedure (false positives). If LOS distribution in a DRG is bimodal, with clusters of cases with very short and long LOS, the underlying assumption of patient homogeneity is untenable. Short of regrouping patients into new DRGs that better reflect PAC needs, we first considered a few DRGs with a broad mix of more or less complex procedures. We illustrate the problem of heterogeneous procedure DRGs using DRG1: Craniotomies.

Data Sources

We used HCFA's Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) data files exclusively for our analyses. MedPAR provides records for 100 percent of Medicare beneficiaries using inpatient services, as well as DRG-specific information. There were roughly 12 million inpatient records in each of 2 years, 1992 and 1998. We identified all cases discharged to a PAC provider using hospital discharge destination codes three (SNFs), five (PPS-exempt units), and six (home health agencies). We did not verify PAC transfers using PAC claims. A separate validation of inpatient PAC transfer discharge destination codes for 1997-1998 using Medicare PAC claims confirmed the accuracy of SNF codes (Gilman et al., 2000). The home health destination codes underreported cases by 15 percent versus 11 percent overreporting of PPS-exempt facility discharges. The overall discrepancy (only 1 percent) in coded versus actual PAC transfers is likely due to the narrow time windows used in the current PAC policy. Hospital discharge planners when coding discharge destination did not consider specific time lags to PAC care in most of 1998 prior to the new policy. All inpatient deaths and acute hospital transfers were excluded (discharge destination code = 20 or 2). Only PPS discharges were included; distinct-part unit psychiatric and substance abuse patients were excluded. After calculating the geometric mean LOS for each DRG based on included claims, we were able to categorize PAC transfers as either short- or long-stay cases. Short-stay patients were defined as those with LOS <= geometric mean LOS minus 1 day because patients with a longer LOS would be paid the full DRG amount.

Results of Three Comparison Groups

This section includes an evaluation of potential DRG candidates for the transfer payment policy. In considering HCFA's and MedPAC's initial expansion list, we first compared 13 additional DRGs (plus DRG 109) using our expanded criteria with HCFA's original 10 DRGs. The next two groupings put DRGs together either with versus without complications or by a common clinical indicator (e.g., infections). DRGs can be candidates in all three groupings.

Original 10 DRGs Versus Next 13 PAC DRGs

In addition to the 10 DRGs that HCFA staff selected to implement the PAC transfer policy under inpatient prospective payment, 10 additional DRGs were considered by HCFA based on total PAC volume and share of discharges. They were ultimately rejected because they had lower rates of short-stay PAC discharges. MedPAC staff, in comments on the new transfer rule, suggested six more DRGs, three of which overlapped with HCFA's expanded list, i.e., the bypass DRGs, along with three additional DRGs involving simple pneumonia. (In the 1999 DRG Grouper, heart bypasses were split into three DRGs (106, 107, and 109) from the original two (106 and 107). Care must be taken in analyzing trends because 106, bypass with cardiac catheterization, was split and non-angioplasty cases put into 107. DRG 107 cases are now in 109.) Table 1 reports results using our PAC selection criteria for the 10 DRGs currently included in the PAC-transfer payment system plus the additional 13 considered by HCFA and MedPAC.

Table 1. Post-Acute Care Frequency by Short-Versus Long-Stay Acute Inpatients, by Diagnosis-Related Groups: 1998.

| Short-Stay PAC Transfer2

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All PAC Transfers1

|

Share of Total Discharges | Share of Short-Stay Discharges | |||||

| Volume | Share of Total Discharge | Relative Odds Ratios3

|

|||||

| DRG | 1998 | 1992-1998 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | Percent Change | |||

| Percent | |||||||

| HCFA's Original 10 | |||||||

| 14 | Cerebrovascular Disorders | 175,457 | 60.2 | 13.6 | 45.1 | 0.676 | 6 |

| 113 | Amp for Circ System Disorder Exc. Upper Limb & Toe | 30,905 | 75.0 | 31.4 | 73.5 | 0.966 | 3 |

| 209 | Major Joint/Limb Reattachment of the Lower Extremity | 253,985 | 75.3 | 21.2 | 80.1 | 1.089 | 9 |

| 210 | Hip/Femur Proc. Exc. Major Joint, > 17w/CC | 103,225 | 83.4 | 25.9 | 84.0 | 1.010 | -3 |

| 211 | Hip/Femur Proc. Exc. Major Joint, > 17 w/o CC | 22,438 | 78.0 | 19.5 | 74.4 | 0.938 | -3 |

| 236 | Fractures of Hip and Pelvis | 25,699 | 75.7 | 31.8 | 73.3 | 0.946 | 2 |

| 263 | Skin Graft/Debridement for Skin Ulcer/Cellulitis w/CC | 14,945 | 63.1 | 28.3 | 59.9 | 0.909 | 8 |

| 264 | Skin Graft/Debridement for Skin Ulcer/Cellulitis w/o CC | 1,922 | 51.0 | 20.5 | 49.0 | 0.931 | 22 |

| 429 | Organic Dist. And Mental Retardation | 15,940 | 58.1 | 17.9 | 50.8 | 0.819 | 1 |

| 483 | Tracheostomy Except Face, Mouth, Neck | 21,250 | 82.1 | 36.2 | 81.1 | 0.979 | 9 |

| HCFA's and MedPAC's Recommended Expansion Transfer | |||||||

| 1 | Craniotomy, >17 Exc. Trauma | 15,180 | 48.3 | 10.9 | 26.0 | 0.405 | -2 |

| 79 | Resp. Infec. And Inflam. >17 w/CC | 91,746 | 57.2 | 22.7 | 50.7 | 0.810 | 15 |

| 89 | Simple Pneumonia, >17 w/CC | 169,644 | 36.7 | 11.2 | 27.8 | 0.651 | 10 |

| 90 | Simple Pneumonia, >17 w/o CC | 9,530 | 21.0 | 2.2 | 10.8 | 0.456 | -14 |

| 91 | Simple Pneumonia, <18 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 1064 | Coronary Bypass w/PTCA | 27,542 | 38.5 | 13.1 | 28.7 | 0.616 | 24 |

| 1074 | Coronary Bypass w/Cardiac Cath | 25,335 | 36.9 | 10.9 | 26.3 | 0.593 | 24 |

| 1094 | Coronary Bypass w/o Cardiac Cath | 5,246 | 37.9 | 8.6 | 26.0 | 0.593 | 24 |

| 148 | Major Bowel Proc w/CC | 51,777 | 41.2 | 13.9 | 27.9 | 0.511 | 8 |

| 239 | Path. Fractures, Muscuoskeletal & Connective Tissue Malignancy | 29,547 | 58.5 | 16.4 | 51.2 | 0.828 | 8 |

| 243 | Medical Back Problems | 33,090 | 40.8 | 4.1 | 17.2 | 0.356 | -22 |

| 296 | Nutr. and Misc. Metabolic Disorders, >17w/CC | 88,701 | 41.6 | 12.2 | 28.8 | 0.566 | 3 |

| 415 | OR Proc for Infect/Parasitic Disease | 20,604 | 57.7 | 22.1 | 48.6 | 0.746 | 20 |

| 468 | Extensive OR Proc. Unrelated to Principal Diag. | 24,066 | 46.7 | 10.1 | 27.2 | 0.468 | 14 |

| All DRGs | 6,839 | 26.4 | 5.8 | — | 0.422 | — | |

Post-acute care (PAC) utilization was identified using Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) discharge destination codes: 03, skilled nursing facility, 05, prospective payment system exempt, and 06, home health agency.

Short stays defined as one day less than the geometric mean length of stay. All patients who died or were transferred to another acute hospital are excluded.

Relative odds ratio = ratio of short-stay PAC to non-PAC patients divided by rate of long-stay PAC to non-PAC patients.

Prior to 1999 DRG 106 covered Coronary Bypass with Cardiac Catherization, and DRG 107 was Coronary Bypass without Cardiac Catherization. However, in 1998 DRG 106 was changed to cover Coronary Bypass with Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty (PTCA), DRG 107 Coronary Bypass with Cardiac Catherization and DRG 109 was created to cover Coronary Bypass without Cardiac Catherization. PAC volumes reflect partial conversion to new categories.

NOTES: DRG is diagnosis-related group. MedPAC is Medical Payment Advisory Commission. NA is not available.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: MedPAR Claims Files, 1998.

The current 10 DRGs appear to be excellent choices based on our expanded set of selection criteria. Most have fairly high short-stay PAC rates (except possibly for strokes, DRG 14, and mental retardation, DRG 429). They also have quite high relative odds ratios. Ratios near 1.0 suggest that the frequency of PAC cases is just as likely to be found in short- as in long-stay cases. Strokes (DRG14) had the lowest odds ratio, 0.67, which is still quite high, compared with all DRGs as a group (mean = 0.42). Despite all 10 DRGs already exhibiting high odds ratios in 1992, 8 of 10 saw their relative odds increase over the next 6 years. With declining geometric mean LOS over time, DRG relative odds should fall, not increase, ceteris paribus, as more cases should equal or exceed the geometric mean LOS. Rising odds ratios suggest a strong trend toward premature discharge of PAC patients.

The second group of 13 DRGs also exhibits high PAC volumes (with the exception of DRG 109, which is an artifact of the shift of some bypass patients from 107 to 109). Their PAC rates are generally lower than the top 10, however, although still quite substantial in most instances, compared with other DRGs. Ten of the 13 DRGs had short-stay PAC rates at least 50 percent above the all-DRG average, and all but 2 had above-average relative odds rates. DRG 243, medical back problems, exhibited the lowest relative odds, at 0.356 because of a low PAC occurrence among short-stay patients (4.1 percent). One reason for the low short-stay PAC rate is the short overall geometric LOS of this DRG of 4.7 days (excluding deaths and transfers to other acute hospitals). We return to the problems created by PAC-induced reductions in geometric mean LOS in the concluding section.

Top 25 DRG Complication Pairs

In selecting the top 10 DRGs for initial implementation of the inpatient PAC transfer policy, HCFA staff decided to include DRG 264, skin graft/debridement without complications, as a pair with DRG 263, skin graft/debridement with complications. HCFA argued that if DRG 264 were excluded, an incentive would be created for hospitals not to code complications so as to receive full DRG 264 payment.

More than 125 DRG complication pairs exist in the classification system based on age, cardiac catheterization, and complications alone. To examine the effect on selection of splitting DRGs by presence or absence of complications, we first ranked individual DRGs appearing in pairs from high to low, based on their own SPAC discharge rate. Once all DRGs were ranked, the top 25 DRGs were chosen for illustrative purposes, along with their companion DRGs. The results are presented in Table 2. Pairs have been re-ranked by their combined PAC volume.

Table 2. Top 25 Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) Complication Pairs Ranked, by Total Post-Acute Care (PAC) Volume: 1998.

| DRG | All PAC Transfers | Short-Stay PAC Transfers | Relative Odds Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Volume | Share of Total Discharges | Share of Total Discharges | Share of Short-Stay Discharges | ||

| 891 | 169,644 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.65 |

| 901 | 9,530 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.46 |

| 911 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | — |

| 2102 | 103,225 | 0.83 | 0.26 | 0.84 | 1.01 |

| 2112 | 22,438 | 0.78 | 0.19 | 0.74 | 0.94 |

| 212 | 4 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.47 |

| 2961 | 88,701 | 0.42 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.57 |

| 297 | 10,269 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.41 |

| 298 | 3 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 1.61 |

| 791 | 91,746 | 0.57 | 0.23 | 0.51 | 0.81 |

| 181 | 2 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 2.00 |

| 180 | 3,250 | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.79 |

| 320 | 76,172 | 0.44 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.66 |

| 321 | 7,225 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.51 |

| 322 | 4 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.60 |

| 416 | 78,850 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 0.39 | 0.71 |

| 417 | 7 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.72 |

| 121 | 51,730 | 0.40 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.58 |

| 122 | 9,291 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.55 |

| 1061 | 27,542 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.62 |

| 1071 | 25,335 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.59 |

| 1091 | 5,246 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.59 |

| 1481 | 51,777 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.51 |

| 149 | 2,602 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.57 |

| 104 | 11,204 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.36 |

| 105 | 10,663 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.54 |

| 218 | 12,266 | 0.58 | 0.17 | 0.43 | 0.64 |

| 219 | 7,156 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.30 |

| 220 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | — |

| 2 | 3,384 | 0.61 | 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.61 |

| 11 | 15,180 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.41 |

| 3 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2632 | 14,945 | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.60 | 0.91 |

| 2642 | 1,922 | 0.51 | 0.21 | 0.49 | 0.93 |

| 154 | 10,946 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.44 |

| 155 | 527 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| 156 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | — |

| 172 | 9,745 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.53 |

| 173 | 352 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.40 |

| 28 | 5,178 | 0.56 | 0.13 | 0.37 | 0.55 |

| 29 | 1,291 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.43 |

| 16 | 5,128 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.54 |

| 17 | 809 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.21 |

| 7 | 5,283 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 0.50 |

| 8 | 476 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.21 |

| 269 | 3,700 | 0.44 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.59 |

| 270 | 567 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.47 |

| 170 | 3,946 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.52 |

| 171 | 138 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| 83 | 3,401 | 0.52 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.71 |

| 84 | 521 | 0.35 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.24 |

| 226 | 2,030 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.50 |

| 227 | 969 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.32 |

| 413 | 2,393 | 0.46 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.71 |

| 414 | 142 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.42 |

| 193 | 2,285 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.57 |

| 194 | 126 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.47 |

| 501 | 1,279 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.64 | 0.86 |

| 502 | 308 | 0.56 | 0.19 | 0.47 | 0.77 |

Included in HCFA/Medicare Payment Advisory Commission's additional 13 DRGs.

Included in HCFA's original 10 DRGs.

NOTES: PAC utilization was identified using Medicare Provider Analysis and Review's discharge destination codes: 03, skilled nursing facility, 05, prospective payment system exempt, and 06, home health agency. Relative odds ratio = ratio of short-stay PAC to non-PAC patients divided by rate of long-stay PAC to non-PAC patients. All patients who died or were transferred to another acute hospital are excluded.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Medicare Provider Analysis and Review Claims Files; data based discharge destination code, 1991-1998.

Out of the top 25 pairs, 15 had total PAC counts in 1998 of 10,000 or more. The lowest total PAC count was for DRG pair 501/502 (knee procedures with infection with or without complications). Yet DRG 501 had the highest SPAC transfer rate of any DRG in any pair other than 210 or 211—higher, even, than for any of HCFA/MedPAC's additional 13 DRGs (Table 1). Both DRGs 501 and 502 also exhibited very high relative odds ratios, and many other DRG pairs also exhibited high relative odds above 0.50. Companion DRGs were usually uncomplicated or of young age and did not exhibit SPAC rates as high as their top 25 companion. This is likely because uncomplicated discharges are in less need of PAC services.

Super-DRG Bundles

Although several complication pairs in Table 2 seem logical candidates for inclusion in the PAC transfer policy, grouping DRGs with or without complications may not be the optimal approach to identifying the best candidates. Other, equally important, criteria split DRGs in ways that undercount aggregate PAC use, as previously explained. Table 3 presents 10 bundles of related DRGs as potential candidates for expansion of the PAC transfer policy. (The number of DRGs included in each bundle is in parentheses next to the bundle name.) The bundles have been formed of DRGs that are clinically related and usually have a common term in their title, e.g., trauma, fracture. Bundles are anchored by at least 1 DRG ranked in the top 100 in terms of the share of SPAC cases in all discharges. Average PAC rates across all DRGs are shown at the top of the table for reference along with HCFA's total PAC volume criterion of 14,000 discharges. The same DRG can appear in more than one super-bundle, e.g., the burn DRGs involving trauma and skin grafts.

Table 3. Potential Post-Acute Care (PAC) Super-Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) Bundles, 1998.

| DRG1 | All PAC Transfers | Short-Stay PAC Transfers | Relative Odds Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Volume | Share of Total Discharges | Share of Total Discharges | ||

|

| ||||

| Percent | ||||

| All DRGs | 14,0002 | 26.4 | 5.8 | 0.42 |

| Trauma (18) | 31,660 | 51.0 | 13.5 | 0.57 |

| Skin Grafts (12) | 47,571 | 49.3 | 18.3 | 0.78 |

| Burns (8) | 480 | 47.5 | 16.7 | 0.84 |

| Infections (23) | 601,089 | 36.2 | 10.8 | 0.66 |

| Major Cardiac (8) | 97,789 | 34.8 | 9.2 | 0.52 |

| Major Joint (17) | 445,969 | 42.3 | 9.8 | 0.48 |

| Fractures (7) | 78,936 | 61.1 | 13.1 | 0.63 |

| Amputations (4) | 43,275 | 61.4 | 22.3 | 0.83 |

| Tracheostomy (2) | 24,441 | 68.3 | 28.1 | 0.89 |

| Behavioral (14) | 43,725 | 24.8 | 6.9 | 0.83 |

The number of DRGs included in each bundle is in parentheses next to the bundle name.

HCFA's total PAC volume threshold.

NOTE: Relative odds = share of short-stay PAC in all short-stay cases divided by similar share of long-stay patients.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Medicare Provider Analysis and Review Claims Files, 1998.

There were 18 DRGs together with more than 31,000 PAC discharges reporting some form of trauma; yet no DRG alone met HCFA's 14,000 PAC discharge minimum. DRG 280, trauma to skin, age>17 w/cc, had the single largest PAC volume: 7,320 cases. The trauma bundle had more than double the average rate of short-stay PAC transfers compared with all DRGs. The relative odds of the group was also considerably above average.

The 12 skin graft/wound debridement DRGs included more than 47,000 PAC discharges with a SPAC/discharge ratio three times the overall DRG average. DRG 271, skin ulcers, with 11,715 PAC discharges, exhibited an exceptionally high relative odds ratio—higher, even, than DRG 263 that currently is covered by the PAC transfer policy. Although there were only 480 cases in total in the burn-related super-bundle, the overall relative odds of the eight DRGs was double the national average.

The 23 DRGs involving infections included more than 600,000 PAC cases, led by DRG 89: simple pneumonia with complications, with 170,000. This DRG is on HCFA's second 10 list. DRGs 79 and 415 in this infections cluster are also on CMS's list for future expansion. Nearly one-third of the infections cases were discharged to PAC with a relative odds ratio 50 percent above average.

Both HCFA and MedPAC staffs targeted open heart surgery and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty as potential candidates for expansion. We expanded the list to include eight major cardiac procedures including valve surgery and other major cardiovascular surgery. Nearly 100,000 cases annually would qualify under this super-bundle that exhibits above-average and rapidly rising SPAC rates. The relative odds ratios of the other thoracic procedures in the bundle were not materially different from the open heart and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty DRGs identified by the government.

The seven fracture and four amputation DRGs also exhibited much higher overall PAC and SPAC rates as expected. As a group, their post-acute followup needs are similar to the hip/knee procedures DRGs (209-211) already included in the PAC transfer policy. For example, DRG 113, amputation except upper limb/toe, in this super-bundle is already included in the transfer policy due to very high PAC volumes (31,000 cases; relative odds = 0.97). DRG 114, upper limb/toe amputation, and DRG 213, amputation for musculoskeletal and connective system disorders, exhibit very similar SPAC and relative odds ratios and should be included along with hip/knee and other amputation procedure DRGs.

We added DRG 482, tracheostomy for face, mouth, and neck, to DRG 483, tracheostomy other than face, mouth, and neck, which is already included in the PAC transfer policy. DRG 482's PAC rate and relative odds ratio = 0.80 are double that of the average DRG. No strong clinical reason exists for exempting the roughly 3,000 cases in DRG 482.

Finally, 14 behavioral health DRGs, with over 43,000 PAC cases altogether, were slightly less likely to be discharged to PAC than the average DRG, but when they were, the relative odds of short-stay patients transferred to PAC was quite high (0.83). Lower PAC rates, coupled with very high relative odds ratios, may be due to the fact that behavioral patients are generally transferred only to psychiatric facilities, if at all, and not to nursing homes or to home health care. Psychoses (DRG 430) and several of the substance abuse DRGs with detoxification and/or rehabilitation exhibited relative odds ratios well above 1.0. Because psychiatric distinct-part units are excluded from PPS, it is important to remember that only scatter-bed patients are included in our analysis. For some of the psychiatric DRGs in particular, it is not clear what kind of treatment is being provided in these scatter beds (Freiman et al., 1988). Furthermore, the presumption that an acute hospital can always treat the patient at least as well as a PAC provider may be incorrect for behavioral patients in scatter beds.

Heterogeneous Drgs: Case Study of Craniotomy

The analysis so far has explored ways of grouping similar DRGs to improve the sensitivity of the transfer policy in identifying low-volume DRGs with high rates of PAC-truncated stays. However, while many inpatient discharges have been split across DRGs in ways that mask total PAC use, other DRGs combine illnesses and procedures with markedly different LOS and PAC rates. To illustrate the bimodal/heterogeneous DRG problem, DRG 1, craniotomy, age greater than 17 except for trauma, was chosen because it includes a disparate set of procedures: craniotomies, skull biopsies, cranial diagnostic procedures, brain excisions, ventriculostomies, and shunt insertion, repair and removal. Biopsies require the removal and examination of tissue of the brain, skull, or cerebral meninges for diagnostic purposes. Ventricular shunts are tube-like devices inserted to drain intracranial fluid from the brain to another body cavity, such as the abdomen, for absorption into the blood stream. A ventriculostomy serves the same general purpose as a shunt, but without any tube insertion. Based on our clinical understanding of DRG 1, we hypothesized that biopsies are among the least complex procedures. Ventricle shunts are more challenging, while craniotomies, craniectomies, and ventriculostomies require the most inpatient medical attention and longest stays.

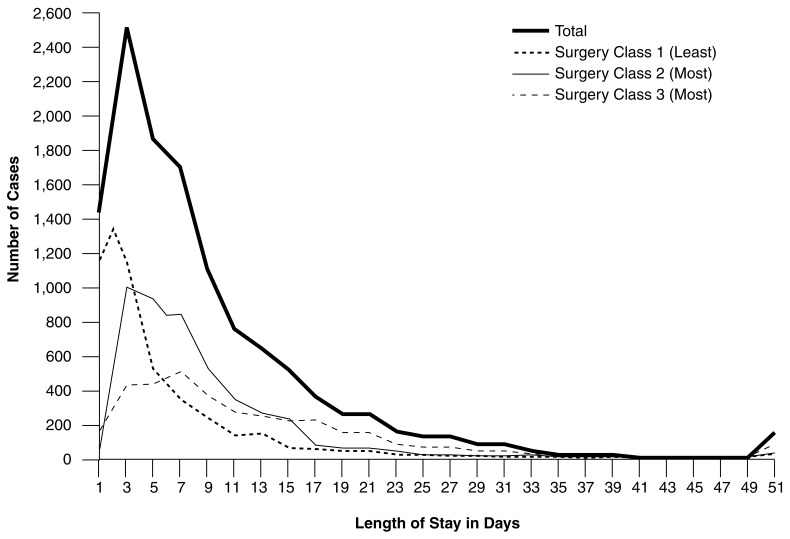

The 1998 MedPAR file was used to construct LOS frequency distributions and volumes for all DRG 1 procedures identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) (Public Health Service and Health Care Financing Administration, 1998) procedure codes. Next, three procedure-specific classes were developed based on average LOS patterns and perceived degree of clinical complexity. Surgery Class 1, considered the least severe, consisted of biopsies, simple operations, diagnostic procedures and some shunt replacement and insertion. Surgery Class 2, involving more severe cases, included brain excisions and cerebral meninges repair. Surgery Class 3 included the most intense procedures, such as craniotomy, ventriculostomy, incisions, and some shunt removal, irrigation and insertion. The distribution of cases across the three subgroups was roughly equal.

Geometric mean LOSs clearly indicate distinct inpatient utilization patterns positively correlated with perceived patient severity of illness (Table 4). Classes 1 and 2 had similar PAC discharge patterns with the majority of patients discharged to home/selfcare. Even still, their PAC use rates were well above average (42.1 and 43.5 percent, respectively). Mortality rates were relatively low (near 3 percent) for both surgery classes as expected. On the other hand, Class 3 exhibited a very different discharge destination pattern. Only one-quarter were sent home with selfcare. A significant portion of cases were sent to a PAC provider (58.9 percent), and the rate of inpatient deaths was very high (23.1 percent). Finally, the geometric mean LOS for Class 3 patients was greater than 13 days, despite the high percentage of non-survivors.

Table 4. Geometric Mean Lengths of Stay, Mortality, and Post-Acute Care Rates, by Procedure Classes in Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG 1 Craniotomy): 1998.

| Surgery Class1 | Number of Cases2 | Geometric Mean Length of Stay (Days) | Mortality Rate3 | Discharges with Post Acute Care2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Percent | ||||

| Total | 24,356 | 9.3 | — | — |

| Class 1 (Least) | 7,643 | 6.4 | 3.3 | 42.1 |

| Class 2 (Moderate) | 9,242 | 8.5 | 2.8 | 43.5 |

| Class 3 (Most) | 7,471 | 13.1 | 23.1 | 58.9 |

The perceived degree of clinical complexity is in parenthesis next to the surgery class.

Excludes inpatient deaths.

Based on all admissions in given class.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Medicare Provider Analysis and Review Claims Files, 1998.

Surgery Classes 1, 2, and 3 have distinct LOS distribution curves (Figure 2). The modal LOS for Class 1 is 2 days. Class 2 peaks at day 4 and Class 3 at day 7. Notice how the (bold) aggregate LOS frequency distribution for DRG 1 masks procedure-specific LOS differences that may be important in interpreting PAC discharges as shifts in the site of care.

Figure 2. Frequency1 Distribution of Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG 1 Craniotomy), by Procedure Surgery Class: 1998.

1 Excludes inpatient deaths.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) Claims Files, 1998.

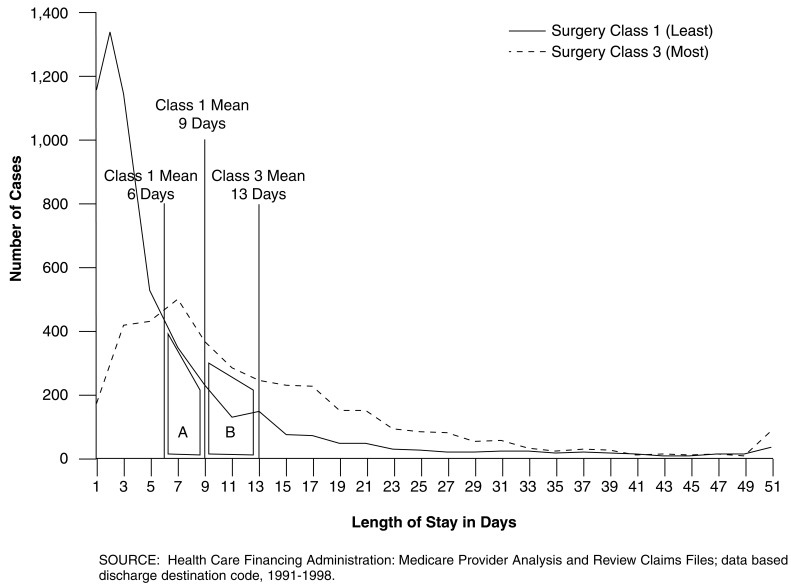

A closer comparison of Class 1 versus Class 3 procedures highlights the potential problem of including heterogeneous DRGs in the PAC transfer policy (Figure 3). The Class 1 geometric mean LOS is 6.4 days compared with 13.1 for Class 3 while the geometric mean LOS for all DRG 1 cases is 9.4 days. All cases with LOS <= 9.4-1 = 8.4 days would have been paid on a per diem basis under the current PAC policy. This includes all cases under either surgical class's probability density function to the left of the overall DRG 1 mean. Eight percent of Class 1 procedure cases are long-stay PAC cases relative to their procedure group mean LOS (area A); yet because they have a length of stay of less than 9 days, they would be reimbursed as short-stay per diem cases under the PAC transfer policy. Conversely, 23 percent of the cases in the Class 3 procedure grid (area B) would receive full DRG payment despite being short-stay cases relative to their procedure group mean LOS. Areas A and B represent false-positive and false-negative error rates of the PAC indicator in picking up true short-stay cases undergoing possible site-of-care substitution.

Figure 3. Frequency of Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG 1 Craniotomy), Length of Stay, by Surgery Class: 1998.

Discussion

In this section, we first make some recommendations for DRG groups that are strong candidates for the next round of policy expansion. Then we review two types of DRGs that, for clinical reasons, may not be ideal candidates even though they exhibit high PAC rates. Next, we present administrative arguments for and against a much larger expansion of the transfer policy to most (or all) DRGs before concluding with a recommendation about how to calculate geometric mean LOS so as to avoid a provider induced bias in the future.

Before moving to recommendations, it is worth reiterating that no single criterion or threshold is clearly superior when recommending expansion of the PAC transfer policy to other DRGs. The congressional mandate to choose 10 high-PAC DRGs, therefore, was somewhat arbitrary. Nonetheless, HCFA staff selected what appear to be excellent choices based on all the criteria. All 10 not only exhibited unusually high SPAC rates per discharge, but also high rates per short-stay discharge as well as relative to PAC rates among long-stay patients.

Recommended DRG Bundles

Most of the second 10 DRGs initially considered by HCFA staff, complemented by 3 additional DRGs recommended by MedPAC staff, also appear to be logical choices. Nearly all exhibit high rates of SPAC discharges compared with most other DRGs as well as relative to their own long-stay PAC rates. DRG 1, craniotomy, may not be appropriate because of its disparate procedure mix.

Strong empirical and theoretical arguments can be made, however, to broaden the scope of inclusion to consider DRG clusters with a common characteristic. Our research shows that underlying common characteristics of DRGs lead to extraordinary PAC discharge rates and truncated stays. Hence, serious omissions occur by ignoring individual DRGs that fail to meet a minimum PAC discharge threshold (e.g., 14,000 cases). In particular, splitting DRGs by complication rates undercounts PAC use rates related in a fundamental way to the reason for admission. This is why HCFA staff (wisely) included DRG 264, skin graft/debridement for skin ulcer without complications, in its original 10 DRGs. We recommend that HCFA staff always include both DRGs in a complicated/uncomplicated pair to avoid overlooking PAC-truncated stays and gaming in the initial coding of the case.

If HCFA staff wish to recommend inclusion of any of the 13 DRGs they (and MedPAC) had considered, initially, we strongly recommend including clusters of related DRGs anchored by 1 of the 13 DRGs. The consistently high SPAC rates among trauma, skin graft, burn, infection, fracture, and amputation patients is striking and confirm the notion that early discharge to PAC is not isolated in a few DRGs. For example, we would not limit expansion to DRGs 79 and 89-91 pertaining to respiratory infections and pneumonia. Rather, we recommend including all 23 infection-related DRGs that exhibit systematically high SPAC rates relative to other DRGs and their own long-stay PAC rates. Particularly telling is the fact that several other DRGs within the infections super-bundle exhibit even higher SPAC rates than DRGs 79 and 89-91, although their PAC volumes do not meet Congress' top 10 volume criterion. The same argument would apply to the coronary bypass DRGs. If they were included in any expansion, then similar major heart surgeries (e.g., valves) ought to be included as well given their similar SPAC transfer rates.

Inappropriate DRGs for Expansion

By contrast, there may be two clinical reasons for not automatically expanding the PAC policy to some DRGs. First, heterogeneous DRGs undermine CMS's site-of-care justification for its per diem payment policy. Hospitals could argue they are only referring patients to PAC that have above-average LOS for the particular procedure included in a DRG. CMS could still argue on actuarial grounds that it is overpaying for all SPAC cases, regardless of procedure, if PAC rates have been rising for short-stay patients. Besides calling for a thorough investigation of their drawbacks for per diem payment, heterogeneous DRGs may call for a more refined set of DRGs than currently in use in the PPS program in general.

Second, short-stay psychiatric/substance abuse discharges to PAC may be appropriate. The set of behavioral health DRGs (i.e., psychiatric and substance abuse) exhibited particularly high relative odds ratios suggesting an unusually high frequency of short-stay patients discharged to PAC. Yet, it is not obvious that every general acute hospital is the optimal provider for such patients. If smaller hospitals are simply stabilizing patients before transfer to a psychiatric or rehabilitation facility, CMS may not want to discourage such behavior with diminished per diem payment. More study of these patients is needed before including the psychiatric and substance abuse DRGs in the PAC transfer policy.

Having recommended several logical clusters of DRGs for expansion, contrasted with other DRGs that raise doubts about a universal PAC transfer policy, let us next summarize the key administrative arguments for and against expanding the PAC transfer policy to many more DRGs.

Arguments for Expanding PAC DRGs

Shifts in site-of-care can occur in any DRG

Early discharge to PAC likely involves a shift in the site-of-care regardless of how many PAC discharges there are in a DRG. Applying a minimum threshold to any continuous criterion, such as the overall or SPAC rate, will always appear arbitrary to providers by paying some PAC-truncated stays differently than others.

10 DRGs inequitable to some hospitals

Hospitals treating a disproportionate number of cases in the 10 (or even expanded list of) DRGs may be unfairly treated by the narrow scope of the policy. One hospital might concentrate on major joint surgery that is subject to lower per diem payments while another competitor emphasizes major heart surgery which is not; yet, both facilities may be discharging patients early to PAC.

Simple, uniform, formula-driven policy

The PAC per diem payment algorithm is formula driven and keys off the standard discharge destination code on the claim. A comprehensive formulistic policy already in place would immediately begin picking up SPAC transfers in other DRGs and automatically discourage premature transfers. It would be simple for Medicare fiscal intermediaries to implement a policy change for all (or most) DRGs while avoiding confusion about which DRGs were eligible for PAC transfer payment.

PAC Discharges Result in Program Overpay-ments

Early discharges to PAC providers constitute a shift of the site-of-care resulting in overpayments to the acute facility for care it did not provide. A rough estimate of the potential savings from extending the PAC transfer policy to all DRGs would be slightly less than 1 percent of all Medicare acute hospital DRG payments, or $720 million annually. This estimate is based on an average SPAC rate of approximately 6 percent (Table 1), an average 15 percent per diem discount on full DRG payment for PAC transfers (Gilman et al., 2000), and $80 billion in DRG expenditures in 1999. If hospitals lengthened PAC stays or stopped discharging as frequently to post-acute providers, inpatient program savings would be less, but so, too, would outlays on PAC.

Arguments Against Expanding PAC DRGs

Two administrative arguments can be made against expanding the PAC transfer policy to all DRGs.

Requires multiple per diem payment policies

CMS has already determined that the standard transfer payment policy fails to cover high front-end costs for DRGs 209-211. Were the policy extended to all (or many) DRGs, CMS would have to evaluate the daily cost patterns of 500 DRGs. A related concern is the asymmetric treatment of transfers to other acute hospitals versus PAC transfers. Only PAC transfers in DRGs 209-211 enjoy a blended per diem that pays one-half of the full DRG payment on the first day. Transfers to other acute hospitals for the same set of DRGs receive less generous double per diems for the first day. If CMS expands the list of DRG PAC transfers, it may have to reconsider its per diem payment algorithm for acute-to-acute hospital transfers.

More auditing required

Fiscal intermediaries are required to audit the discharge destination codes for accuracy now that they are used for payment purposes. Extending the policy to many more DRGs would require extensive auditing. This would require linking PAC claims from other Part A and B providers with inpatient claims because of the 24- and 72-hour post-discharge windows established by the policy, a costly and time-consuming process. Also, with many more DRGs, CMS (and hospitals) would have more work sorting out unrelated from related PAC discharges. Annual program savings would pay for these administrative costs.

Long-Run Implications of Shorter Stays

Besides the arguments against expanding the policy to more DRGs, the pervasive trend toward shorter acute stays naturally limits the policy's effectiveness. Our analysis revealed many DRGs whose geometric mean LOS was: 3 days or less. As PAC rates and truncated inpatient stays rise, DRG geometric mean stays fall, resulting in fewer and fewer short-stay PAC cases qualifying for per diem payment. This creates a bias in the transfer payment policy by allowing the threshold criterion for reduced payment, i.e., geometric mean LOS, to be influenced by industry PAC discharge behavior. To avoid this bias, geometric mean LOS for payment purposes should be based on discharges excluding transfers to other acute hospitals or to PAC providers.

Technical Note

In the transfer policy, per diem payment will be less than the full DRG payment (DRG) for a patient with LOS if 2[DRG/GLOS] + (LOS -1)[DRG/GLOS] < DRG where GLOS = the geometric mean and DRG/GLOS = the per diem rate. Solving the inequality, [DRG/GLOS] (2+LOS-1) < DRG, or LOS+1 < GLOS.

With regard to payment biases from excluding a related DRG, the greater the disparity in full payment between the DRG pair and the higher the geometric mean LOS of the uncomplicated DRG, the less incentive there is not to code complications. For the uncomplicated DRG to generate the same or greater revenue than its complicated paired DRG, the per diem revenue from the complicated DRG must be less than the full DRG payment from billing the uncomplicated DRG. This assumes that a patient's LOS would qualify for full DRG payment in the uncomplicated, but not in the complicated DRG. That is, DRGu > PDc (LOSi + 1) = (DRGc/GLOSc) (LOSi +1), where DRGu and DRGc = full payment for the uncomplicated and complicated DRG pair, PDc = the per diem of the complicated DRG, GLOSc = the complicated DRG's geometric mean stay, and LOSi = the i-th patient's LOS. Rearranging the inequality gives (LOSi + 1)/GLOSc <DRGu/DRGc. For the hospital to have an incentive not to code complications and receive full DRGu payment, the patient's LOS plus one day relative to the complicated DRG's geometric mean LOS would have to be less than the relative full payments of the DRG pair.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our appreciation to Dan McGrane who provided valuable comments.

Footnotes

The authors are with RTI International. The research for this article was funded under HCFA Contract Number 500-95-0006. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of RTI International or the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Reprint Requests: Jerry Cromwell, Ph.D., RTI International, 411 Waverley Oaks Road, Suite 330, Waltham, MA 02452-8414. Email: jcromwell@rti.org

References

- Buczko W. Inpatient Transfer Episodes Among Aged Medicare Beneficiaries. Health Care Financing Review. 1993 Winter;15(2):71–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. Medicare Program: Changes to the Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems and Fiscal Year 2001 Rates; Final Rule. 2000 Aug 1;65FR(148):47079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. Medicare Program; Changes to the Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems and Fiscal Year 2001 Rates; Proposed Rule. 2000 May 5;65FR(88):26302. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. Medicare Program: Changes to the Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems and Fiscal Year 1999 Rates; Final Rule. 1998a Jul 31;63FR(147):40974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register. Medicare Program; Changes to the Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems and Fiscal Year 1999 Rates; Proposed Rule. 1998b May 8;63FR(89):25590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiman M, McGuire T, Ellis R, et al. An Analysis of Options for Including Psychiatric Inpatient Settings in a Prospective Payment System. National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD.: Jun, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman BH, Cromwell J, Adamache W, Donoghue S. Study of the Effect of Implementing the Postacute Care Transfer Policy under Inpatient PPS. Health Care Financing Administration; Baltimore, MD.: Jul 31, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Ellis R, Merrill A. Bundling Post-Acute Care with Medicare DRG Payments: An Exploration of the Distributional and Risk Consequences. Inquiry. 1996 Fall;33(3):381–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC.: Mar, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress: Context for a Change Medicare Program. Washington, DC.: Jun, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Prospective Payment Assessment Commission. Report to Congress: Medicare and the American Health Care System. Washington, DC.: Jun, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Service and Health Care Financing Administration. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC.: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J, Cromwell J, McGuire TP. Excluded Facility Financial Status and Options for Payment System Modification. Health Care Financing Review. 1993 Winter;15(2):7–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]