Abstract

Disenrollment rates have often been used as indicators of health plan quality, because they are readily available and easily understood by purchasers, health plans, and consumers. Over the past few years, however, indicators that more directly measure technical quality and consumer experiences with care have become available. In this observational study, we examined the relationship between voluntary disenrollment rates from Medicare managed care (MMC) plans and other measures of health plan quality. The results demonstrate that voluntary disenrollment rates are strongly related to direct measures of patient experiences with care and are an important complement to other measures of health plan performance.

As CMS has evolved from an organization that focused on claims' payment to a value-based purchaser of health care, it has dramatically increased its efforts to assess and report medical care quality. These efforts include the collection and reporting of the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2003), the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS®) (Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study, 2003), the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey (HOS) (Medicare Health Outcomes Survey, 2003), and the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) (Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, 2003). CMS uses these and other data to monitor quality, inform beneficiaries, and target quality improvement efforts. These measures are designed to assess various dimensions of performance, some of which are related. For example, research has demonstrated significant relationships between HEDIS® effectiveness of care measures and CAHPS® measures of experiences with care (Schneider et al., 2001).

Voluntary disenrollment from health plans—another important, albeit less direct measure of health plan performance than CAHPS® and HEDIS®—is readily available for the MMC program. Voluntary disenrollment rates can be compared easily. Beneficiaries may disenroll from Medicare+Choice (M+C) health plans on a monthly basis and enroll in another plan if one is available or in traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare. Disenrollment, therefore, can be disruptive to Medicare beneficiaries and costly to health plans. Voluntary disenrollment rates are a concern in the M+C program, because the number of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled has declined substantially in the last 4 years. In late 1998, there were slightly more than 6 million beneficiaries in Medicare managed care risk plans. By September 2002, the number of covered beneficiaries in risk plans under the M+C program was slightly fewer than 5 million, about 12 percent of the total Medicare enrollment, according to the monthly summary report of MMC plans (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2003). Much of this decline is due to the exit of MMC plans from the market, but voluntary disenrollment might also explain some of this decline.1 Thus, disenrollment rates are of great interest. However, more knowledge about the determinants of disenrollment would be helpful in deciding whether voluntary disenrollment rates should be used as a performance measure.

Both conceptual models and empirical analysis can be helpful in understanding the causes of voluntary disenrollment from health plans. One conceptual model was presented by Hirschman (1970). He described the main ways that people can influence health care quality as “voice” or “exit.” According to Hirschman, patients can express their opinions in an attempt to change care (as they do through CAHPS®) or they can leave their provider or health plan to express their dissatisfaction.

An empirical analysis of disenrollment patterns and the investigation of relationships between disenrollment and other variables can complement conceptual approaches to understanding the causes of voluntary disenrollment. Rossiter, Langwell, and Rivnyak (1989) found that approximately one-half of the disenrollment from a health maintenance organization (HMO) within one year was due to misunderstanding the terms of enrollment. They also found no significant difference in overall satisfaction between HMO enrollees and FFS beneficiaries.

Riley, Ingber, and Tudor (1997) were among the first to publish on disenrollment patterns among Medicare enrollees in HMOs. They reported on disenrollment rates, characteristics of disenrollees, and variation among plans in 1994 and 1995. The annual disenrollment rate for 1994 was 14.2 percent. Thirty-eight percent of the disenrollments were to FFS, and 62 percent switched to another HMO. They found that those who disenrolled to FFS were more likely to be disabled, Medicaid-eligible, older, and to be recent enrollees. They found considerable variation in disenrollment rates among the 17 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) that they studied. In addition, they found that independent practice associations (IPAs) had the highest rates of disenrollment and staff models had the lowest rates. In 2000, CMS implemented an annual survey to identify the reasons that beneficiaries voluntarily disenroll from plans. The results of the analysis of 2000 data, reported by Harris-Kojetin et al. (2002), indicated that increases in copayments, the cost of copayments, problems getting to see particular doctors, and obtaining plan information were the most frequently-cited reasons for voluntary disenrollment. Other problems cited were: getting or paying for prescription medicines, getting needed care, obtaining care or other service, and having particular needs met.

Our study differs from the approach used in the CMS annual survey of reasons for disenrollment, because our study measures the experience of enrollees still in the plan, not the experience of those who have already exited from the plan. Enrollees who have exited are much more likely to have negative perceptions of the plan than those still enrolled. Moreover, their expressed reasons for leaving the plan and their views of their experiences while they were enrolled do not necessarily align with enrollees who are still with the plan, some of whom may be dissatisfied, others who may be satisfied with their plan.

Our study attempted to assess the extent to which enrollees' experience with their health plan was associated with plan voluntary disenrollment rates. In assessing the relationship between enrollees' experience and voluntary disenrollment, we also considered other factors as possible contributors to voluntary disenrollment. We investigated the relationships of the following variables to voluntary disenrollment rates: enrollee experiences with their plan and the care they receive as measured by CAHPS®, plan and enrollee characteristics, and competition in the market area. We also assessed what combinations of these variables best predict voluntary disenrollment rates.

Study Methods

Sample

We used CAHPS® data collected by CMS to reflect consumer ratings of care received in 1998. These data were collected between September and December 1998 from all health plans with Medicare contracts that were in effect on or before January 1, 1997 and in business for at least 2 years. A simple random sample of up to 600 members who had been enrolled for at least 12 months was drawn from each plan or reporting unit. The response rate for the 1998 CAHPS® survey was 81 percent (Goldstein et al., 2001).

We excluded plans with contracts that had been terminated. Contracts that covered large areas were divided into geographically defined reporting units, yielding 310. For these analyses, we excluded seven units that had fewer than 30 respondents for one of the CAHPS® composites (two of the seven units did not have disenrollment data reported). We excluded 80 reporting units, because they did not have matching disenrollment data and one plan that had a disenrollment rate of 82.2 percent, leaving 222 reporting units. The CAHPS® data were aggregated by reporting unit and merged with the voluntary disenrollment data for each plan in calendar year 1998.

Measures

The voluntary disenrollment rates were supplied by CMS. These rates excluded involuntary disenrollments due to death, loss of eligibility, managed care organization administrative actions, or beneficiary changes of residence out of a service area.

The CAHPS® predictors used in our analyses of 1998 data included four global ratings (plan, personal doctor, health care, and specialist) and CAHPS® composite scores based on responses to questions about getting needed care, getting care quickly, information from the health plan and customer service, doctor communication, special services, and courtesy and helpfulness of staff. We also analyzed individual items from CAHPS® that asked about: doctor's knowledge of important health facts about the patient, patient problems getting special services, problems getting prescription medications, complaint resolution, and access to equipment. The items from CAHPS® that were used to form the composite measures are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. CAHPS® Variables Used to Form Composite Measures: 1998.

| Variable | Survey Items |

|---|---|

| Global Ratings |

|

| Composite Rating of Health Plan Information and Customer Service |

|

| Composite Rating of Getting Needed Care |

|

| Composite Rating of Getting Needed Care |

|

| Composite Rating of Getting Courtesy and Respect of Doctor's Office Staff |

|

| Composite Rating of Communication with Providers |

|

| Composite Rating of Special Services |

|

| Composite Rating of Courtesy and Respect of Office Staff |

|

| Rating of Problems Getting Prescription Medications from Health Plan |

|

| How often get needed prescription medications |

|

| Was Complaint Settled to Your Satisfaction |

|

| Did Plan Provide all the Equipment and Services Needed |

|

NOTE: CAHPS® is Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study.

SOURCE: CAHPS® Adult Core Questionnaire, October 1998.

In addition to patient experiences, we analyzed plan characteristics, characteristics of the areas in which sampled members lived, and managed care competition in the plan service area. Managed care competition (competitor index) was defined as the number of Medicare risk plans in the counties that comprise the plan service area of the reporting units in this study. Reporting units with more competitors, therefore, had a higher competitor index. We matched ZIP Codes of sampled Medicare beneficiaries to the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1990) data on the percentages of residents of each respondent's ZIP Code area who: have at least a college degree, receive public assistance, identify themselves as black persons, Hispanic, or of Asian descent, and live in urban areas.2

We developed measures of plan characteristics from the InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.2, Database (InterStudy, 1998). That database contains annually updated information on HMOs operating in the United States. We defined four categories for local and national not-for-profit and for-profit health plans (Landon et al., 2001). We incorporated information about the primary type of physician network in the plan (group/staff, IPA, or network) and the number of years the plan has been operating. Variables were also linked indicating whether the plan was federally qualified, the plan's National Committee Quality Assurance accreditation status, region, total enrollment, and the percent of plan enrollment comprised of Medicare beneficiaries.3 The census data from the 1990, InterStudy, and the competitor index were aggregated by reporting unit with the CAHPS® and voluntary disenrollment data.

Analysis

We used bivariate and multivariate methods to examine the relationship of voluntary disenrollment to several measures of Medicare beneficiaries' rating of their experiences. All analyses used reporting unit level variables. We calculated Pearson product moment correlation coefficients to examine the associations between disenrollment rates and other variables. Next, we used multiple regression to examine the independent effects on voluntary disenrollment of the CAHPS® variables, plan characteristics, and the market characteristics.

Results

Health Plan Characteristics

The 222 health plans included in the analysis were distributed throughout the country (Table 2). There were at least 10 health plans from each of the eight regions that we analyzed. Of the health plans, 79 percent were either IPA or network model plans, and over one-half had enrollment between 75,000-400,000. Almost 50 percent were national for-profit and 23 percent were local not-for-profit. About one-half were fully accredited by the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Table 2. Characteristics of Medicare Managed Care Health Plans: 1998.

| Characteristic | Mean | Standard Error | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plan Age | 18.70 | 0.77 | — |

| Type of Physician Network | |||

| Group or Staff | — | — | 21.0 |

| Independent Practice Association | — | — | 60.0 |

| Network | — | — | 19.0 |

| Total Enrollment | |||

| ≤ 75,000 | — | — | 17.8 |

| 75,001 – 400,000 | — | — | 52.9 |

| ≥ 400,001 | — | — | 29.3 |

| Plan Type | |||

| National For-Profit | — | — | 48.6 |

| National Not-For-Profit | — | — | 8.7 |

| Local For-Profit | — | — | 19.7 |

| Local Not-for-Profit | — | — | 23.1 |

| Competitor Index | 3.71 | 0.18 | — |

| National Committee for Quality Assurance Accreditation Status | |||

| Full Accreditation | — | — | 49.3 |

| 1-Year Accreditation | — | — | 20.4 |

| Not Accredited | — | — | 30.3 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | — | — | 5.0 |

| North Mid-Atlantic | — | — | 9.5 |

| Mid-Atlantic | — | — | 9.0 |

| South Atlantic | — | — | 17.1 |

| Upper Midwest | — | — | 21.6 |

| Southwest | — | — | 12.6 |

| Pacific | — | — | 18.5 |

| Northwest | — | — | 6.8 |

| Persons in Respondent's ZIP Code Area | |||

| Black | — | — | 10.8 |

| Asian | — | — | 2.8 |

| 4-Year College Degree or Higher | — | — | 26.6 |

| Live in Poverty (Age 65 or Over) | — | — | 6.7 |

| Live in Poverty (All Ages) | — | — | 8.4 |

| Live in Urban Area | — | — | 84.5 |

| High-Status Occupation | — | — | 23.3 |

NOTE: n=208.

SOURCES: (InterStudy®, 1998; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1990); Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Data from the Group Health Plan Provider File, 1998.

There were statistically significant bivariate associations between five of the plan variables and the voluntary disenrollment rate for 1998 (Table 3). These were the profit status and ownership variables, the competitor index, and the average percent of persons in respondent's ZIP Code who are black persons.

Table 3. Correlation of Plan Characteristics with Voluntary Disenrollment Rate: 1998.

| Plan Characteristic | Pearson Correlation with Voluntary Disenrollment Rate |

|---|---|

| Plan Age (Years) | -0.12 |

| Total Enrollment | -0.13 |

| Group or Staff Plan Type | -0.13 |

| Independent Practice Association Plan Type | 0.07 |

| Network Plan Type | -0.02 |

| National for-Profit | ***+.37 |

| National Not-for-Profit | *-.14 |

| Local For-Profit | -0.12 |

| Local Not-For-profit | *-.15 |

| Competitor Index | ***+.23 |

| Full NCQA Accreditation | 0.04 |

| One-Year NCQA Accreditation | 0.02 |

| Not NCQA Accredited | -0.07 |

| Average Percent of Persons in Respondent's ZIP Code Who | |

| Are Black | ***+.22 |

| Are Asian | 0.01 |

| Have a 4-Year College Degree or More Education | -0.05 |

| Are Age 65 Years or Over and Live in Poverty | 0.13 |

| Live in Poverty | 0.07 |

| Live in an Urban Area | **+.18 |

| Have a High Status Occupation | -0.02 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

NOTE: NCQA is National Committee for Quality Assurance.

SOURCES: (InterStudy® 1998); Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Data from the Health Plan Voluntary Disenrollment Data File; and the Group Health Plan Provider file, 1998; (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1990).

Voluntary Disenrollment Rates and CAHPS® Scores

The mean 1998 voluntary disenrollment rate was 11.58 percent, with a range of 1 to 46 percent, and the median 1998 voluntary disenrollment rate was 9.53 percent (Table 4). The mean 1998 overall plan rating was 8.76 (on a scale of 0-10), indicating that beneficiaries generally gave very positive ratings to their plans. The median overall plan rating was 8.77.

Table 4. Voluntary Disenrollment and CAHPS® Descriptive Data: 1998.

| Variable | Mean (Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|

| Voluntary Disenrollment Rate | 11.58 (7.65) |

| Plan Rating | 8.76 (0.28) |

| Care Rating | 8.92 (0.25) |

| Personal Doctor Rating | 8.82 (0.25) |

| Specialist Rating | 8.81 (0.26) |

| Composites | |

| Getting Needed Care | 2.81 (0.06) |

| Plan Information and Customer Service | 2.69 (0.10) |

| Communication with Providers | 3.64 (0.07) |

| Getting Care Quickly | 3.47 (0.11) |

| Office Staff | 3.78 (0.06) |

NOTES: CAHPS® is Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. n=208.

SOURCE: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Data from the Health Plan Voluntary Disenrollment Data File and the CAHPS® Survey Data File, 1998.

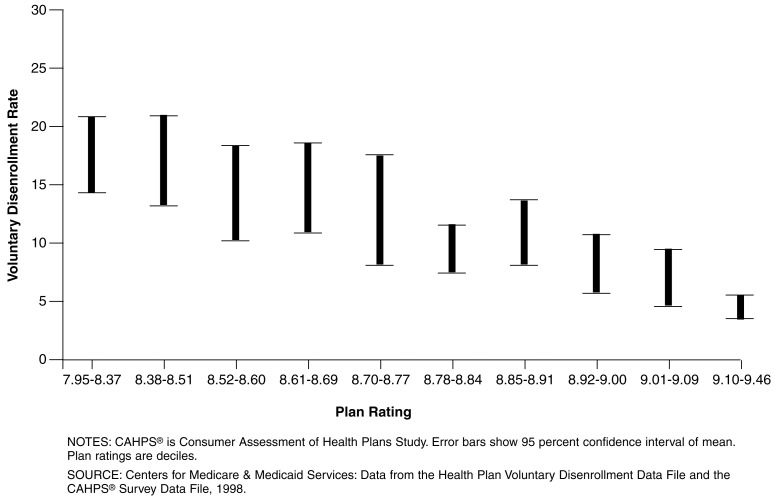

The overall plan rating had the highest correlation (r=-0.55) with voluntary disenrollment rates (Table 5.) Figure 1 displays the relationship between plan ratings and voluntary disenrollment rates for 1998. Among the 10 percent of plans with the lowest overall ratings, the mean disenrollment rate was 17.72 percent as compared with 4.44 percent for the 10 percent of plans with the highest ratings. Thus, the mean voluntary disenrollment rate was four times higher for plans in the lowest 10 percent of overall ratings than for plans with the highest 10 percent of overall ratings.

Table 5. Correlations of CAHPS® Variables and Plan Characteristics with Voluntary Disenrollment Rates: 1998.

| Characteristic | Pearson Correlation Coeficient |

|---|---|

| Overall Plan Rating | ***-0.55 |

| Overall Care Rating | ***-0.25 |

| Overall Personal Doctor Rating | -0.12 |

| Overall Specialist Rating | **-0.18 |

| Health Plan Information and Customer Service | ***-0.47 |

| Getting Needed Care | ***-0.40 |

| Communication with Providers | ***-0.24 |

| Getting Care Quickly | ***-0.27 |

| Office Staff | ***-0.25 |

| Personal Doctor Knows All Important Health Facts and How Health Problems Affect Daily Life | **-0.19 |

| Any Problem Getting Prescription Medication from Health Plan | ***-0.25 |

| Was Complaint with Health Plan Settled to Member's Satisfaction | ***-0.29 |

| Getting Special Medical Equipment, Therapy or Home Care | ***-0.47 |

| Plan Provided All Needed Equipment and Services | ***-0.37 |

p-value<0.01.

p-value<.001.

NOTE: CAHPS® is Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study.

SOURCE: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Data from the Health Plan Voluntary Disenrollment Data File and the CAHPS® Survey Data File, 1998.

Figure 1. Relationship Between Voluntary Disenrollment Rates and Overall Plan Ratings from CAHPS®: 1998.

Ratings of special services, health plan information and customer service, getting needed care, and getting special medical equipment, therapy, or home care were all at least moderately related to voluntary disenrollment rates. The overall personal doctor rating was the only CAHPS® variable that was not significantly related to the voluntary disenrollment rates.

Multivariate Relationships

In regression models of the association between CAHPS® measures and voluntary disenrollment rates in 1998, the two strongest independent predictors were the overall plan rating and the composite rating of special services (Table 6). These variables in linear combination explained 36 percent of the variation in health plan voluntary disenrollment rates. We also tested whether the other CAHPS® variables in Table 5 that were at least moderately related to voluntary disenrollment rates added significantly to the prediction of voluntary disenrollment rates. However, due to the relatively high inter-relationships among these variables, they did not improve prediction once the overall plan rating and the composite rating of special services were entered into the regression model.

Table 6. Regression Models Predicting Voluntary Disenrollment Rates1.

| Variable | Models | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Overall Plan Rating |

***-15.14 (-0.55) |

***-11.61 (-0.43) |

— — |

***-10.82 (-0.40) |

| Getting Special Medical Equipment, Therapy, or Home Care | — — |

***-14.77 (-0.25) |

— — |

**-10.64 (-0.18) |

| Ownership1 | ||||

| National For-Profit Plan | — — |

— — |

***5.12 (-0.33) |

1.81 (-0.12) |

| National Not-for-Profit Plan | — — |

— — |

-1.74 (-0.06) |

-3.15 (-0.11) |

| Local For-Profit | — — |

— — |

0.43 (-0.02) |

0.06 (-0.003) |

| Average Percent of Persons in Respondent's ZIP Code Who Are Black | — — |

— — |

*0.13 (-0.16) |

*0.09 (-0.12) |

| Competition | — — |

— — |

***0.65 (-0.23) |

0.13 (-0.04) |

| R2 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.4 |

p-value <0.05.

p-value<0.01.

p-value<0.001.

Omitted category: Local Not-for-Profit.

NOTES: Standardized regression coefficients in parentheses. The standardized regression coefficients can vary from -1 to +1 and reflect the degree of variation in the dependent variable explained by the independent variable, controlling for the other independent variables. In contract to unstandardized regression coefficients, standardized regression coefficients are not affected by the magnitude of the units of the independent variables.

SOURCE: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Data from the Health Plan Voluntary Disenrollment Data File and the CAHPS® Survey Data File, 1998.

We next examined the extent to which ownership, percent of persons in the plan service contract area who are black, and competition predicted disenrollment (Table 6). National for-profit plans had significantly higher voluntary disenrollment rates than local not-for-profit plans. In addition, plans in areas with more black persons had higher voluntary disenrollment rates, as did plans in areas with more managed care competition. These variables together explained about 22 percent of the variation in plan voluntary disenrollment rates. When we estimated a model that contained both CAHPS® scores and plan characteristics, the only significant predictors of disenrollment were the two CAHPS® scores selected and the percent of black persons in the plans' service areas.

Discussion

Medicare beneficiaries' ratings of their experiences with health plans were related to voluntary disenrollment rates, with overall plan rating being the strongest predictor (r=-0.55). Due to the relatively high interrelationships among the CAHPS® variables, other ratings of beneficiary experience did not improve prediction once the overall plan rating and the composite rating of special services were entered into the regression model.

The mean voluntary disenrollment rate was four times higher for plans in the lowest 10 percent of overall plan ratings as measured by CAHPS® than for plans in the highest 10 percent of overall CAHPS® ratings. This is a very significant finding, especially considering the fact that the CAHPS® ratings were obtained by surveying current enrollees and did not include any enrollees who had already exited from their plan.

Whether a plan provides all the special services needed by beneficiaries, including medical equipment, therapy, and home care, was an important predictor of voluntary disenrollment rates (r=-0.47). This result confirms our hypothesis that plan ratings capture important experiences related to enrollment decisions. This result also indicates that other important influences are not fully reflected in the overall plan rating. Health plan information and customer service, and getting needed care were also highly related to voluntary disenrollment rates. The remaining CAHPS® variables had low to moderate relationships with voluntary disenrollment rates except for the overall personal doctor rating which was not significantly related to voluntary disenrollment. There are several possible explanations for why there was not a significant relationship between personal doctor ratings and voluntary disenrollment. One possibility is that doctors in some service areas are providers in all the plans that are available to beneficiaries in those service areas. Another possibility is that plan enrollees do not necessarily have to go outside their plan if they are unhappy with their personal doctor; they can switch doctors within their plan.

Several plan and market characteristics were related to voluntary disenrollment. People might leave certain types of plans because of their reputation. Alternatively, these plans might have relatively high disenrollment rates because beneficiaries have less favorable experiences in these plans (Landon et al., 2001). The fact that plan characteristics were not significant predictors in the multivariate models supports the later interpretation. The measure of competition in the plan service areas did not add significantly to our ability to predict voluntary disenrollment rates after accounting for beneficiary experience with their health plans.

After controlling for plan ratings, we found that the percent in the respondent's area who are black persons was significantly related to voluntary disenrollment rates. The study by Riley et al. (1997) may be helpful in interpreting this finding. They found that Medicaid-eligible beneficiaries (dually eligible beneficiaries) had the highest HMO disenrollment rates in the Medicare Program. To the extent that black persons are disproportionately represented in the Medicaid population, their disenrollment rates, therefore, would be expected to be relatively high. It could also be that plans in areas with large Medicaid populations systematically differ from plans in other areas, or that other unmeasured characteristics of persons in these areas are related to disenrollment. This finding was not anticipated when this study was planned, and should be investigated in future research. Such research should determine the extent to which other variables that are related to race may have contributed to this finding. Future research also might involve a case study or survey approach to gain additional insight into perceptions about health plans and the causes of disenrollment among black persons.

There have been a number of changes in the M+C program since 1998. This includes a substantial number of plans deciding to drop out, a decline in Medicare beneficiary enrollment, and changes in plan benefit offerings. Recent research reported by Cox, Lanyi, and Strabic (2002) found that benefit offerings had only a slight (but statistically significant) impact on disenrollment in the M+C program; plan benefits did not seem to play a key role in plan performance ratings. While we were not able to include a measure of benefits in this study, the strong relationships we observed with measures of patient experiences from CAHPS® suggest that the relationship between CAHPS® scores and voluntary disenrollment would persist even if we controlled for benefits. Our study did not attempt to answer whether or not voluntary disenrollment reflects other important measures of plan performance such as clinical effectiveness of care.

Our results do not imply that voluntary disenrollment rates can be used in lieu of direct measures of quality. While informative, disenrollment rates are less actionable then either the CAHPS® or HEDIS® measures, which target particular care processes or experiences. We do think, however, that our findings support voluntary disenrollment rates as a complement to these other important measures of plan performance.

Our results have several implications for plans, purchasers, and consumers. Health plans are using performance measures such as CAHPS® and HEDIS® to develop their quality improvement efforts. Timely data substantially increase their usefulness. CAHPS® and other performance data are collected annually, but generally are not available for analysis for at least 6 months after data collection. An advantage of voluntary disenrollment data is that they can be examined on a continuous basis during the year. Since performance measures from CAHPS® are strongly related to disenrollment rates in managed care plans, plans can have more immediate information to monitor and implement quality improvement strategies if they examine their voluntary disenrollment rates and trends in a timely manner.

An important objective for purchasers in using performance measures is that they can directly support a variety of strategies designed to improve the quality of health care. It is likely that support for purchasing strategies will require integration of performance measurement systems so that various indicators can be used either individually or in appropriate combinations. For example, individual measures may support focused quality improvement efforts, but a variety of combined indicators may best support performance standards (Zaslavsky et al., 2002; Lied, Malsbary, and Ranck, 2002). All of these approaches will be better informed if relationships between key performance measures are understood.

Many of the key factors related to consumers' overall ratings of their health plans have been established through research, much of it sponsored by CMS. For example, the delivery and consumer composites of CAHPS® were found to be strongly predictive of ratings of overall care, doctor, and specialist (Zaslavsky et al., 2000). In addition, significant relationships have been found among different measures of performance such as effectiveness of care and consumers' ratings of health plans (Schneider et al., 2001). The results of our study offer more evidence of such relationships. The strong relationship between voluntary disenrollment and patient ratings, supports the development of patient information strategies to assist consumer choices among health plans. Voting with your feet is an easily understood marker of quality for most individuals. Voluntary disenrollment rates are, therefore, likely to remain an important performance measure. Given the results of our study, voluntary disenrollment can be used for beneficiary information with the confidence that it both complements and reflects other important measures of quality.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to James Ranck, Christina Smith-Ritter, Susan Watson, and Liz Goldstein for contributing to the data development and analysis. We also want to thank collaborators at CMS, Bearing Point, Inc., Westat, Inc., DRC, Inc., and the Picker Institute for their efforts in the CAHPS-MMC implementation project that generated the CAHPS data used in this article.

Footnotes

Terry R. Lied and Steven H. Sheingold are with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Bruce E. Landon, James A. Shaul, and Paul D. Cleary are with the Harvard Medical School. Portions of this research were funded by CMS under Contract Number 500-95-0057(TO#9) with Bearing Point, Inc. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CMS, Harvard Medical School, or Bearing Point, Inc.

Lock-in provisions will be effective on January 1, 2005 (Public Law 107-188 approved on June 12, 2002). These provisions will constrain the ability of beneficiaries to voluntarily disenroll from plans.

These percentages were based on the entire resident population not just Medicare beneficiaries. We did not have Medicare-specific data available on these variables, but believe that there was a reasonably close correspondence between the percentages for the total resident population and Medicare population for these groups.

For these analyses, we were able to match 208 of the 222 reporting units to the InterStudy (1998) database.

Reprint Requests: Terry R. Lied, Ph.D., Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 7500 Security Boulevard, S3-13-15, Baltimore, MD 21244-1850. E-mail: tlied@cms.hhs.gov

References

- Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Internet address: www.ncbd.cahps.org. (Accessed 2003.)

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Managed Care Contract Plans Monthly Summary Report. Internet address: http://www.cms.gov/healthplans/statistics/mmcc/. (Accessed 2003.)

- Cox D, Lanyi B, Strabic A. Medicare HMO Benefits Packages and Plan Performance Measures. Health Care Financing Review. 2002 Fall;24(1):133–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein E, Cleary PD, Langwell KM, et al. Medicare Managed Care CAHPS®: A Tool for Performance Measurement. Health Care Financing Review. 2001 Spring;22(3):86–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L, Bender R, Booske B, et al. Medicare CAHPS® 2000 Voluntary Disenrollment Reasons Survey: Findings from an Analysis of Key Beneficiary Subgroups. RTI International; Research Triangle Park, NC.: Aug, 2002. Report to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman AO. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA.: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- InterStudy. InterStudy Competitive Edge Database 8.2. InterStudy Publications; St. Paul, MN.: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Beaulieu ND, et al. Health Plan Characteristics and Consumers'Assessments of Quality. Health Affairs. 2001 Mar-Apr;20(2):274–286. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lied TR, Malsbary R, Ranck J. Combining HEDIS® Indicators: A New Approach to Measuring Plan Performance. Health Care Financing Review. 2002 Summer;23(4):117–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Health Outcomes Survey. Internet address: www.cms.hhs.gov/surveys/hos. (Accessed 2003.)

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. Internet address: http://www.ncqa.org/. (Accessed 2003.)

- Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Internet address: www.cms.hhs.gov/MCBS/default.asp. (Accessed 2003.)

- Riley GF, Ingber MJ, Tudor CG. Disenrollment of Medicare Beneficiaries from HMOs. Health Affairs. 1997 Sep-Oct;16(5):117–124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.5.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter LF, Langwell KM, Rivnyak TT. Patient Satisfaction among Elderly Enrollees and Disenrollees in Medicare Health Maintenance Organizations. Results from the National Medicare Competition Evaluation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989 Jul;262(1):57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, Landon BE, et al. National Quality Monitoring of Medicare Health Plans: The Relationship Between Enrollees'Reports and the Quality of Clinical Care. Medical Care. 2001 Dec;39(12):1313–1325. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. U.S. Census Bureau Data. 1990 Internet address: www.census.gov/acsd/www/sub_d.htm. (Accessed 2003.)

- Zaslavsky AM, Beaulieu ND, Landon BE, Cleary PD. Dimensions of Consumer-Assessed Quality of Medicare Managed-Care Health Plans. Medical Care. 2000 Feb;38(2):162–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaslavsky AM, Shaul JA, Zaborski LB, et al. Combining Health Plan Performance Indicators into Simpler Composite Measures. Health Care Financing Review. 2002 Summer;23(4):101–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]