Abstract

The Medicare Health Outcomes Survey (HOS) uses the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) SF-36® among beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare managed care programs, whereas the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has administered the Veterans version of the SF-36® for quality management purposes. The Veterans version is comparable to the MOS version for 6 of the 8 scales, but distinctly different in role physical (RP) and role emotional (RE) scales. The gains in precision for the Veterans SF-36® provide evidence for the use of this version in future applications for assessing patient outcomes across health care systems.

Introduction

Over the past three decades, patient-centered measures of health have been developed for assessing the health outcomes of patients (Ellwood et al., 1995; Tarlov et al., 1989; Safran, Tarlov, and Rogers, 1994). These measures have been shown to be reliable, valid, and responsive to important clinical changes (Guyatt, Feeny, and Patrick, 1993; Ware et al., 1996). A growing number of both generic and disease-specific measures have been developed. These measures are often used interchangeably and sometimes without regard to differences in item content, response choice differences, and formatting changes (Hays, Anderson, and Revicki, 1993; McHorney et al., 1994a; Sullivan et al. 1995). One of the most widely used generic measures is the MOS SF-36® Health Survey (version 1.0) (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992). This survey has been used in different venues of care for monitoring and evaluating patient outcomes (Ware, Kosinski, and Keller, 1994).

Starting in 1998, the HOS began collecting MOS data among Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare MCPs for purposes of monitoring the health status of enrollees on a continuing basis (Stevic et al. 2000). Given that the SF-36® is a generic measure of health, the outcomes reflect the accumulation of the results of health care process when case mix is properly taken into account. These results, which are reported only to each plan, are presented in terms of changes in health status, or more specifically, either being the same, better than expected, or worse than expected. However, this version has limitations in terms of ceiling and especially floor effects with several scales, notably the RP and RE scales (McHorney et al., 1994b). Individual members of a plan at the low end of a scale may not have any room to diminish further in their physical or mental functional disabilities. On the other hand, members at the high end of a metric (i.e. the ceiling of the scale) may not be able to improve any further. The floor effect may be particularly problematic in the elderly population, where both physical and mental functional limitations are quite common. The aging process in those 65 or over is often accompanied by the emergence of both comorbid medical and mental conditions, which are likely to influence the assessments of their health. The range of health status values may require substantial room at the lower end of the scale for measuring worse health in these elderly patients so that the scale may adequately discriminate those who have substantial disease burden and functional limitations.

The Veterans Health Survey was modified from the original version of the MOS for use in the VHA (Kazis, 2000). The VHA is one of the largest integrated health care systems, in the U.S., with 145 major medical centers and about 5 percent of the total market share in the United States. Considering that the veterans enrolled in the VHA are often older and have more medical and mental morbidities than other veterans not using the VA health care systems (Kazis et al., 1998), modifications to the MOS version were made to address the ceiling and floor effects by expanding the range in the SF-36® metric. More specifically, the Veterans version involved modifications to the 2 role scales, i.e., physical and emotional, by expanding on their response choices from 2-point to 5-point responses. Conversion formulas, which were developed so that the scoring of the role scales of the Veterans SF-36® were comparable to the MOS version, were also validated for comparisons of the MOS with the Veterans' version (Perlin et al., 2000; Kazis et al., Forthcoming, 2004).

This article provides evidence for the comparability or differences in the MOS, as used in the Medicare HOS, compared with the Veterans Health Survey. Given that there was a considerable number of patients administered both the VA and CMS surveys, this unique sample provided an opportunity for comparisons of the two versions. Our objectives are, therefore, to examine the distributional properties, reliability, and discriminant validity between the MOS and Veterans Health Survey using patients who were administered both versions of the survey. We hypothesize that with the modifications, the role scales of the Veterans version would demonstrate an improvement in the reliability, discriminant validity, and precision over those of the MOS survey.

Methods

Survey Instruments

The MOS SF-36® is well documented and described elsewhere (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992; McHorney et al., 1994b). Briefly, the MOS version measures eight concepts of health: physical functioning (PF), role limitations due to physical problems (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health perceptions (GH), energy/vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role limitations due to emotional problems (RE), and mental health (MH). The original MOS scoring was used in which items from each scale are summed and rescaled with a standard range from 0 to 100, where a score of 100 denotes the best health. These eight concepts have also been summarized into two scales: a physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) (Ware, Kosinski, and Keller, 1994, Ware and Kosinski, 2001). The summary scales are based on the finding that more than 90 percent of the reliable variance in the eight SF-36® scales is explained by the physical and mental dimensions of health. The two component summary scales are each scored using weights derived from a national probability sample of the U.S. population. They are standardized to the U.S. population and norm-based so that the scores have a direct interpretation in relation to the distribution of scores in the U.S. population with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10, with higher scores denoting better health.

The Veterans SF-36® Health Survey, which builds on the MOS version, made modifications that include changes to the two role scales (RP and RE) that include seven items. Response choices that were originally dichotomous (yes/no) are now five-point ordinal choices (i.e., no, none of the time; yes, a little of the time; yes, some of the time; yes, most of the time; and yes, all of the time). Like the MOS, the Veterans version of the SF-36® measures the same eight health concepts and are scored using the original MOS scoring system. Following the MOS SF-36®, the two component summary scores (PCS and MCS) of the Veterans SF-36® are standardized to and norm-based on the U.S. population (Kazis and Wilson, 1997; Kazis et al., 1998a; 1998b; 1998c, 1998d); Perlin et al., 2000). Each component summary is expressed as a T score, which facilitates comparisons between the VA patients and the U.S. population.

The Veterans version has been previously shown as reliable and valid in ambulatory VA patient populations, and has been adopted by the VHA as one of the measures of health care values (Kazis et al., 1999; Kazis, 2003, 2004). The eight scales of the Veterans SF-36® has Cronbach's alphas (1951) ranging from 0.93 to 0.78 for the PF and SF scales, respectively (Kazis et al., 1999; Forthcoming, 2004). Published work from the Veterans Health Study (Kazis et al., 1998d, 1999, 2004) has demonstrated the discriminant validity of the individual scales and component summaries. The Veterans scale and component summary scores are strongly correlated with sociodemographics and morbidities of the veteran users of the VHA system of care (Kazis et al., 1998d, 1999).

Data

This study used data from the 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees (VA Survey) and the 1999 HOS Cohort II baseline survey. The details of these two surveys are described elsewhere (Perlin et al., 2000; HEDIS® 1998, 1999, 2000). Briefly, the VA Survey was obtained from a stratified random sample of 3,421,388 veterans enrolled in the VHA as of 1999. Of those enrolled, 1,406,049 were sampled and 887,775 (63.14 percent) completed the survey. Data collection took place between July 1999 and January 2000. A modified total design methodology (TDM) approach, (Dillman, 2000), was used to increase response rate. This approach uses four carefully spaced mailings: (1) a prenotification letter, (2) a cover letter and the Veterans SF-36®, (3) a reminder post card, and (4) second wave of questionnaire mailings to the non-respondents of the first-wave mailings. All mailings occurred over 12 weeks, with a 14-week followup period for questionnaire receipts. Information on the 1.4 million sampled enrollees was obtained from VA administrative data (i.e., Patient Treatment and Outpatient Files) to provide sociodemographic characteristics and other administrative information (e.g., service connected disability status). ICD-9-CM (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004) diagnosis codes were also obtained from these files, which were used to develop a measure of selected comorbid medical and mental conditions based on literature review and a consensus panel of clinicians. Once survey data were merged with the administrative data, individual identifiers were subsequently stripped to maintain confidentiality.

The Medicare HOS was first fielded in March 1998, as part of National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA), HEDIS® 3.0, that included the MOS SF-36®. Each year since, a new baseline cohort has been drawn; each cohort is resurveyed 2 years later. The HOS Cohort II survey was fielded in March-May 1999. Simple random samples of 1,000 beneficiaries who had been enrolled for at least 6 months (and were not ESRD patients) were selected from each of 312 contract markets (for plans with fewer than 1,000 members, all eligible members were selected). Among 292,355 eligible beneficiaries, 194,378 members completed the survey representing a response rate of 66.5 percent.

For the Medicare HOS survey, potential respondents were mailed a prenotification letter, followed 1 week later by a cover letter and survey. A reminder was mailed approximately 2 weeks later, followed by a second copy of the cover letter and survey after another 2 weeks. After a second reminder, a minimum of six attempts were made to contact the potential respondent by telephone. The 1999 HOS Cohort II survey was chosen because it is most proximal in time to the VA survey. The VA survey was conducted from July 1999-January 2000, with over 90 percent of the respondents returning the survey between July and September 1999. The 1999 HOS Cohort II survey was fielded earlier than the VA survey, with dates being on average about 3 to 4 months apart from the VA survey.

After merging the HOS Cohort II survey with the VA survey, there were 3,607 respondents who completed both surveys. Of the 3,607 cases, 2,737 (76 percent) had data to compute SF-36® scores for both the HOS and Veterans versions, using the 50 percent rule for dealing with missing values (i.e., if more than 50 percent of the items for a given scale were missing, then we coded the scale as missing). Thus, for these 2,737 respondents, we computed both the MOS and Veterans SF-36® scale. Data for these respondents, who were in both the 1999 HOS Cohort II and the 1999 VA surveys, were then merged with VA administrative data from the outpatient and inpatient files, which include ICD-9 CM codes. These codes are fairly complete and provide diagnostic information for the 3 years prior to the VA survey (Perlin et al., 2000). The coding scheme identified 30 medical and 6 mental health conditions that are commonly encountered in clinic visits in the VA (Selim et al., 2002).

Analyses

Because the differences in the Veterans and MOS SF-36® surveys are in the role scales (RP and RE), we focus on comparing these two scales and on the physical and mental summaries. However, for completeness, we also report on the results of the other 6 scales in the tables. The results reported do not reflect the use of the conversion formulas; thus the Veterans SF-36® role scales and the PCS and MCS are able to use the full range and units of the improved metric without sacrificing the lack of precision that the converted values would give.

Cronbach's Alpha Statistics

We generated Cronbach's alpha (1951) statistics, a measure of the scale's precision, for each of the 8 scales of the Veterans and MOS SF-36®. We also report the reliability of the PCS and MCS. Because the component summaries are linear combinations of the 8 scales, the reliability coefficient must take into account the reliability of each scale and the covariances among them using the internal consistency method (Ware, Kosinski, and Keller, 1994). The measurement variance is based on a fundamental theorem about variances:

Because the two component summaries are statistically independent, the covariance term drops away, and we can simply add the variances of the scales, multiplied by the square of their weights. The variance of the scale is (1-alpha) (ordinary scale SD)2 and the weights are derived from the formulas for constructing PCS and MCS.

Multi-Trait Scaling

Multi-trait scaling uses convergent and discriminant validity to test the performance of items in their hypothesized scales. Item-scale correlations are the primary elements of multi-trait scaling (Hays, Anderson, and Revicki, 1990). Item internal consistency is assessed by determining if each item in a scale is substantially linearly related to the total score computed from other items in that same scale. The item discriminant validity criterion is assessed by determining if each item has higher correlations with the scale it is hypothesized to belong to, than with all other scales. These two tests gauge the consistency of items in their scale and their divergence from other items in different scales. Item internal consistency is supported if an item correlates substantially (r ≥0.40) with the scale it is hypothesized to represent. To correct for overlap, the hypothesized item is deleted from the scale with which it is correlated.

Item discriminant validity depends on the magnitude of the correlation between an item and its scale relative to the correlation of that item with other scales. If the hypothesized correlation is more than 2 standard errors higher than the other correlations a scaling success is counted, if it is more than 2 standard errors lower a definite scaling error is counted, and if it is within 2 standard errors of all correlations with other scales, it is considered a probable scaling error.

As previously mentioned, to test for internal consistency, reliability coefficients (Cronbach's alpha) were computed for each of the scales, as well as the range of the correlations for both item internal consistency and item discriminant validity. Thus, we also included for the item discriminant validity testing the number of successes, failures, and probable failures for each of the 8 scales of both the Veterans SF-36® and the MOS versions.

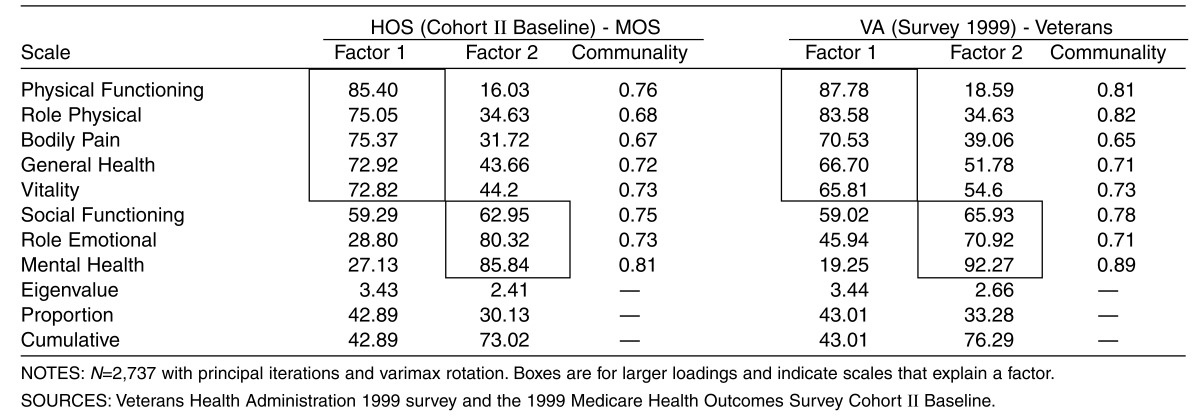

Factor Analysis

Factor analysis was conducted for the 8 scales for both the Veterans and MOS versions, using principal iterations and varimax rotation. Factors were retained for eigenvalues that are greater than 1.0 prior to factor extraction. Both the variance explained by the rotated factor structure and communalities were reported for each. Comparisons were made between the Veterans and MOS versions based on factor loadings (e.g. the extent to which items tend to cluster together as a unique group), variance explained by the rotated factor structure, and communalities for the respective scales.

Discriminant Validity Testing

Discriminant validity testing of the Veterans and MOS SF-36® scales was conducted by comparing scale score means and SDs across groups of patients defined at different levels of clinical severity (as defined by the number of comorbidities). In this analysis, we assess the ability of the Veterans and MOS SF-36® scales and summary scales to discriminate among the groups stratified by a comorbidity index. The medical comorbidity index is a sum of medical conditions and can range from 0 to 30, while the mental comorbidity index can range from 0 to 6. Both are simple sums of conditions based on ICD-9-CM diagnoses obtained from VA administrative data over the 3 years prior to the VA survey. This comorbidity index, with its medical and mental indices, has been validated previously in prior work (Selim et al., 2002). It is important to note that there are a number of diagnosis-based measures of comorbidities, such as the Charlson Index (Charlson et al., 1987). However, the Comorbidity Index (CI) has two advantages over the Charlson Index (Selim et al., 2002). First, while the Charlson Index may account for the effects of more severe conditions, the CI accounts for the effects of conditions that are commonly encountered in clinic visits. Consequently, the Charlson Index is used more in predicting mortality, whereas the CI is more pertinent to patient outcomes as measured by health-related quality of life. Second, the CI offers an important benefit of having two indexes, a physical and a mental CI that are directly related to different disease profiles of the patients. These advantages indicate that the CI has an important role in the implementation of risk adjustment when assessing patient outcomes.

Analytic methods for assessing discriminant validity included general linear model procedures (OLS regression) with the F statistics and associated p-values reported for the Veterans and MOS SF-36® role scales and the physical and mental summaries. Comparison of the F statistics is based on an interaction term between the survey (Veterans versus the MOS SF-36®) and the number of medical or mental comorbidities. We view this as a measure of the difference between the two measures ability to discriminate across the summative levels of comorbidity. This is a direct comparison of the trends of the two versions where a significant F statistic may be driven by the range of the differences of the scale scores.

The relative efficiencies of the Veterans and MOS versions for the role scales are given by the ratio of the F statistics for each using one-way analysis of variance. The ratio is computed relative to the MOS version (Veterans version result as the numerator and MOS version as the denominator). We conduct a similar test of efficiency of the two versions using PCS and MCS. We report on the differences in efficiency of RP, RE, PCS and MCS for the Veterans and MOS versions.

We also examined the range of mean scores of the role scales and the PCS and MCS across increasing levels of comorbidity. Although we did not anticipate any differences between the other scales, we examined them as well. We were particularly interested in identifying differences in floor and ceiling between the two versions, e.g., whether the Veterans version had reduced floor effects compared to the MOS version for the role scales, as reported in previous work (Kazis et al., Forthcoming, 2004).

Results

Among 2,737 respondents to both the MOS and Veterans SF-36®, over 90 percent were age 65-99, 81 percent were white persons, 9 percent black persons, and 5 percent Hispanic. Ninety-eight percent were male and about 72 percent were married. On average, respondents had more than 2 medical comorbidities and about 0.2 mental comorbidities. The demographic profile reflects, for the most part, veterans utilizing VA care.

The Veterans SF-36® version has reduced the floor effects and raised the ceiling effects compared to the MOS version. For example, using the Veterans version, about 11 and 7 percent of the respondents had the lowest possible scores (floor effects) on the RP and RE scales, respectively. This is compared to 43 and 25 percent, respectively for RP and RE, of the respondents when using the MOS version. Similarly, about 11 and 30 percent of the respondents reported the highest possible scores (ceiling effects) on RP and RE, respectively, when using the Veterans version. On the other hand, when using the MOS version, 25 and 55 percent of the respondents reported the highest possible scores on PF and RP, respectively.

The correlations without overlap for the RP items ranged from 0.88 to 0.91 for the Veterans SF-36® and 0.76 to 0.82 for MOS. For the RE items the correlations ranged from 0.86 to 0.91 for the Veterans, and 0.75 to 0.80 for MOS versions. The correlations without overlap were substantially higher for the Veterans than the MOS versions for these 2 scales, indicating greater item convergent validity and internal consistency at the item level for the Veterans version. This suggests that because of greater precision for the role items, the item-correlations for each of these concepts are higher for the Veterans version.

Tables 1 and 2 present the results of the multi-trait scaling tests for the Veterans (Table 1) and the MOS versions (Table 2). For each scale, the correlations of its hypothesized items are shown with all 8 scales, including the hypothesized scale (shown in italics, corrected for overlap) and for the remaining 7 scales. For the RP scale, the Veterans version yielded item-scale correlations without overlap with the hypothesized scale that were higher than the correlations with other scales. In all cases, the correlations were more than 2 standard errors higher than the other correlations, indicating that all were scaling successes for each scale. Similarly, the MOS version yielded all scaling successes for the role physical scale items. For the Veterans and MOS versions, a similar pattern emerged for role emotional scale, with all scaling successes for both versions of the scale. Not surprisingly, the patterns of correlations in terms of scaling successes were similar for the other 6 scales for the Veterans and MOS versions. Almost all correlations in the two instruments reflect scaling successes at the item level for each scale.

Table 1. Multi-Trait Scaling Test Results for VA Item-Scale Correlations: Veterans Health Administration (Survey 1999)—Veterans SF-36®.

| Scale | PF | RP | BP | GH | VT | SF | RE | MH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning (PF) | ||||||||

| Vigorous Activities | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.21 |

| Moderate Activities | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.39 |

| Lifting or Carrying Groceries | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.39 |

| Climbing Several Flights of Stairs | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.32 |

| Climbing One Flight of Stairs | 0.82 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.36 |

| Bending, Kneeling, or Stooping | 0.72 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.35 |

| Walking More than a Mile | 0.78 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.32 |

| Walking Several Blocks | 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.34 |

| Walking One Block | 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.34 |

| Bathing or Dressing Yourself | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.34 |

| Role Physical (RP) | ||||||||

| Cut Down Amount of Time at Work | 0.68 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.44 |

| Accomplished Less than Would Like | 0.66 | 0.89 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.43 |

| Limited in Kind of Work | 0.69 | 0.91 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.43 |

| Difficulty Performing Work | 0.69 | 0.91 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.45 |

| Bodily Pain (BP) | ||||||||

| Bodily Pain | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.85 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.47 |

| Pain Interfering with Normal Work | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.50 |

| General Health (GH) | ||||||||

| General Health | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.52 |

| Get Sick a Little Easier | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.5 | 0.55 |

| As Healthy as Anybody | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.44 |

| Expect Health to Get Worse | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.39 |

| Excellent Health | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

| Vitality (VT) | ||||||||

| Full of Pep | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.53 |

| Lots of Energy | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.54 |

| Feel Worn Out | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.55 |

| Feel Tired | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.52 |

| Social Functioning (SF) | ||||||||

| How Much Interfered with Social | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.62 |

| How Often Interfered with Social | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| Role Emotional (RE) | ||||||||

| Cut Down Amount of Time at Work | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.90 | 0.62 |

| Accomplished Less than Like | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 0.60 |

| Didn't Do Work as Carefully | 0.49 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.59 |

| Mental Health (MH) | ||||||||

| Very Nervous | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.66 |

| Down in the Dumps | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.77 |

| Calm and Peaceful | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.67 |

| Downhearted and Blue | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.72 |

| Happy | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.63 |

NOTES: N=2,737. Correlations in italics are between items and hypothesized scale, with given item omitted. Remaining correlations are those items from other scales with given scale. Sample is overlap of the VA survey with the Medicare HOS.

SOURCES: Veterans Health Administration 1999 Survey and the 1999 Medicare Health Outcomes Survey Cohort II Baseline.

Table 2. Multi-Trait Scaling Test Results for 1999 HOS Survey Cohort II Baseline Item-Scale Correlations: Medical Outcomes Study SF-36®.

| Scale | PF | RP | BP | GH | VT | SF | RE | MH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning (PF) | ||||||||

| Vigorous Activities | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.22 |

| Moderate Activities | 0.79 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.35 |

| Lifting or Carrying Groceries | 0.77 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| Climbing Several Flights of Stairs | 0.79 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.30 |

| Climbing One Flight of Stairs | 0.83 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| Bending, Kneeling, or Stooping | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.32 |

| Walking More than a Mile | 0.78 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.31 |

| Walking Several Blocks | 0.83 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| Walking One Block | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| Bathing or Dressing Yourself | 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

| Role Physical (RP) | ||||||||

| Cut Down Amount of Time at Work | 0.52 | 0.76 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.38 |

| Accomplished Less than Would Like | 0.53 | 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.37 |

| Limited in Kind of Work | 0.58 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.37 |

| Difficulty Performing Work | 0.57 | 0.82 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.39 |

| Bodily Pain (BP) | ||||||||

| Bodily Pain | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 0.46 |

| Pain Interfering with Normal Work | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.49 |

| General Health (GH) | ||||||||

| General Health | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Get Sick a Little Easier | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.52 |

| As Healthy as Anybody | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.46 |

| Expect Health to Get Worse | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.38 |

| Excellent Health | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 0.47 |

| Vitality (VT) | ||||||||

| Full of Pep | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.46 |

| Lots of Energy | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.53 |

| Feel Worn Out | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.42 | 0.53 |

| Feel Tired | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| Social Functioning (SF) | ||||||||

| How Much Interfered with Social | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.59 |

| How Often Interfered with Social | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.63 |

| Role Emotional (RE) | ||||||||

| Cut Down Amount of Time at Work | 0.40 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.78 | 0.56 |

| Accomplished Less than Like | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.80 | 0.53 |

| Didn't Do Work as Carefully | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 0.51 |

| Mental Health (MH) | ||||||||

| Very Nervous | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.63 |

| Down in the Dumps | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.74 |

| Calm and Peaceful | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.61 |

| Downhearted and Blue | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.71 |

| Happy | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.61 |

NOTES: N=2,737. Correlations in italics are between items and hypothesized scale, with given item omitted. Remaining correlations are those items from other scales with given scale. Sample is overlap of the VA survey with the Medicare HOS.

SOURCES: Veterans Health Administration 1999 Survey and the 1999 Medicare Health Outcomes Survey Cohort II Baseline.

Table 3 reports the factor structures for the Veterans and the MOS versions. Results indicate that the cumulative variance is about 3 percent higher for the Veterans than the MOS version (76 versus 73 percent). For the two factors, the first assessing physical health and the second mental health, the pattern of loadings was similar. Communality estimates range from 0.65 to 0.89 for Veterans version and 0.67 to 0.81 for the MOS version. The RP communality was substantially higher for the Veterans version (0.82 versus 0.68), and comparable for the RE for both versions. Separate factor structures conducted for patients diagnosed with hypertension, type 2 diabetes, chronic lung disease, chronic heart failure, and chronic low back pain yielded similar results (results not shown).

Table 3. Factor Analysis for Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) SF-36® and Veterans Versions of the SF-36®.

|

Cronbach's alpha statistics for the Veterans and the MOS version ranged from 0.86 for GH to 0.96 for RP, and for the MOS from 0.85 (GH, SF, and MH) to 0.94 (PF). No appreciable differences were found except for RP and RE scales, where the Veterans version yielded consequential improvements over the MOS version (0.96 versus 0.91, for RP and 0.95 versus 0.89 for RE, respectively). The Cronbach's alpha for PCS and MCS are 0.96 and 0.95 for the Veterans version, and 0.95 and 0.90 for the MOS version. These results suggest improvement in precision for the MCS summary of about 5 and 1 percent for the PCS summary.

Tables 4 and 5 report the results of the discriminant validity for the RP and RE scales. As shown in Table 4, the number of medical comorbidities is significantly associated with worse health, with a highly significant monotonic trend for both versions. Interestingly, for mental comorbidities, the relationship between the scale scores and the number of mental comorbidities shows a different pattern for RP, a more medically oriented scale. More specifically, the lower scores are largely determined by whether or not a respondent has a comorbid mental condition and are not driven by the number of mental comorbidities. This pattern is consistent across the MOS and the Veterans versions. Compared to the MOS, the Veterans version demonstrates lower scores of RP and RE, about 25 to 35 percent of 1 SD lower depending on the number of comorbid medical or mental conditions. Using the ratio of the F statistics, the Veterans version is about 11 percent more efficient than the MOS version for discriminating across the number of medical conditions and about 31 percent more efficient for the mental conditions for both RP and RE.

Table 4. Discriminant Validity of Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) SF-36® Compared to Veterans SF-36® Survey: Role Physical Scale.

| Comorbidities | MOS Mean (SD) |

Veterans Mean (SD) |

MOS-VA1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | |||

| 0 | 56.27(44.41) | 47.05(42.21) | 9.22 |

| 1 | 53.61(43.51) | 41.54(40.15) | 12.07 |

| 2 | 48.92(43.72) | 40.04(40.92) | 8.88 |

| 3 | 42.81(43.99) | 33.08(38.63) | 9.73 |

| 4 | 36.85(41.49) | 29.44(38.33) | 7.41 |

| 5 | 34.23(41.20) | 24.66(35.06) | 9.57 |

| >6 | 27.13(37.85) | 17.62(32.91) | 9.51 |

| F Statistic2 | 120.64 | 133.53 | 0.25 |

| p-value2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.6159 |

| Mental | |||

| 0 | 45.95(43.75) | 36.54(40.55) | 9.41 |

| 1 | 32.96(41.98) | 22.73(34.65) | 10.23 |

| >2 | 32.82(40.98) | 22.82(34.81) | 10.00 |

| F Statistic2 | 12.27 | 16.03 | 0.03 |

| p-value2 | 0.0005 | <0.0001 | 0.8567 |

MOS SF-36® score minus Veterans SF-36® score.

F statistic and p-value are for testing a linear trend.

NOTES: N=2,737. SD is standard deviation.

SOURCES: Veterans Health Administration 1999 Survey and the 1999 Medicare Health Outcomes Survey Cohort II Baseline.

Table 5. Discriminant Validity of Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) SF-36® Compared to Veterans SF-36® Survey: Role Emotional Scale.

| Comorbidities | MOS Mean (SD) |

Veterans Mean (SD) |

MOS-VA1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | |||

| 0 | 73.76(39.22) | 70.00(47.32) | 3.76 |

| 1 | 72.82(38.92) | 66.43(46.21) | 6.39 |

| 2 | 69.32(41.52) | 61.67(48.87) | 7.65 |

| 3 | 66.12(42.84) | 56.08(49.43) | 10.04 |

| 4 | 62.41(43.77) | 48.14(47.63) | 14.27 |

| 5 | 56.81(44.03) | 45.86(48.16) | 10.95 |

| >6 | 50.05(44.27) | 36.33(46.73) | 13.72 |

| F Statists2 | 78.54 | 121.12 | 11.6 |

| p-value2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | *0.0007 |

| Mental | |||

| 0 | 69.15(41.00) | 60.16(48.87) | 8.99 |

| 1 | 47.45(45.33) | 39.84(45.02) | 7.61 |

| >2 | 39.66(44.10) | 26.93(42.65) | 12.73 |

| F Statistic2 | 67.22 | 63.91 | 0.91 |

| p-value2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.3395 |

Significant at 0.001 level.

MOS SF-36® score minus Veterans SF-36® score.

F statistic and p-value are for testing a linear trend.

NOTES: N=2,737. SD is standard deviation.

SOURCES: Veterans Health Administration 1999 Survey and the 1999 Medicare Health Outcomes Survey Cohort II Baseline.

Tables 6 and 7 present the discriminant validity results for PCS and MCS. For PCS, the summary scores are significantly associated with the number of medical comorbidities for both versions, with a highly significant monotonic trend for each. This relationship is generally also observed for the number of mental comorbidities. The level of health is lower (about 10 to 15 percent of 1 SD) using the Veterans SF-36® than those using the MOS version in every stratum of the number of comorbidities. The relative efficiency of the MOS version is about 7 percent greater for the sum of the medical comorbidities than the Veterans version. For the mental comorbidities it also favors the MOS version by about 56 percent. However, the point estimates for each of the number of mental comorbidities suggests that both versions show little differences between 1 and > 2 comorbid mental conditions. For MCS (Table 7), both versions display highly significant monotonic trends for the number of medical and mental conditions. Patients using the Veterans version have significantly lower mean scores than those administering the MOS version for comorbid medical conditions (about 10 to 30 percent of 1 SD lower) and for comorbid mental conditions (about 15 to 31 percent of 1 SD lower). The Veterans version is 44 percent more efficient for the number of medical comorbidities and about 11 percent more efficient for the number of mental comorbidities.

Table 6. Discriminant Validity of Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) SF-36® Compared to Veterans Version of the SF-36®: Physical Component Summary.

| Comorbidities | MOS Mean (SD) |

Veterans SF-36® Mean (SD) |

MOS-VA1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | |||

| 0 | 41.48(11.60) | 39.61(11.91) | 1.87 |

| 1 | 40.46(11.83) | 37.54(11.32) | 2.92 |

| 2 | 38.41(11.42) | 37.34(11.44) | 1.07 |

| 3 | 36.56(11.59) | 35.06(10.83) | 1.5 |

| 4 | 35.01(11.42) | 33.88(11.16) | 1.13 |

| 5 | 32.99(11.13) | 31.27(10.42) | 1.72 |

| >6 | 31.31(10.81) | 29.64(9.98) | 1.67 |

| F Statistic2 | 208.27 | 194.73 | 1.55 |

| p-value2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.2129 |

| Mental | |||

| 0 | 37.40(12.10) | 35.66(11.80) | 1.74 |

| 1 | 34.73(11.14) | 32.75(10.11) | 1.98 |

| >2 | 34.90(10.91) | 33.84(10.59) | 1.06 |

| F Statistic* | 5.86 | 3.31 | 0.95 |

| p-value* | *0.0155 | 0.0689 | 0.3309 |

Significant at 0.05 level.

MOS SF-36® score minus Veterans SF-36® score.

F statistic and p-value are for testing a linear trend.

NOTES: N=2,737. SD is standard deviation.

SOURCES: Veterans Health Administration 1999 Survey and the 1999 Medicare Health Outcomes Survey Cohort II Baseline.

Table 7. Discriminant Validity of Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) SF36® Compared to Veterans Version of the SF-36®: Mental Component Summary.

| Comorbidities | MOS Mean (SD) |

Veterans Mean (SD) |

MOS-VA1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | |||

| 0 | 51.81(10.41) | 50.79(11.96) | 1.02 |

| 1 | 50.86(11.16) | 49.53(12.60) | 1.33 |

| 2 | 50.29(11.08) | 48.44(12.94) | 1.85 |

| 3 | 50.15(10.50) | 48.04(12.91) | 2.11 |

| 4 | 48.96(11.94) | 45.49(13.33) | 3.47 |

| 5 | 48.06(11.41) | 45.14(12.97) | 2.92 |

| >6 | 45.04(12.55) | 42.31(13.28) | 2.73 |

| F Statists2 | 66.21 | 95.66 | 11.82 |

| p-value2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | *0.0006 |

| Mental | |||

| 0 | 50.96(10.46) | 49.02(12.24) | 1.94 |

| 1 | 43.64(12.30) | 42.06(12.89) | 1.58 |

| >2 | 38.31(13.76) | 33.89(14.17) | 4.42 |

| F Statistic2 | 180.69 | 198.14 | 8.7 |

| p-value2 | *<0.0001 | *<0.0001 | **0.0032 |

Significant at 0.001 level.

Significant at 0.01 level.

MOS SF-36® score minus Veterans SF-36® score.

F statistic and p-value are for testing a linear trend.

NOTES: N=2,737. SD is standard deviation.

SOURCES: Veterans Health Administration 1999 Survey and the 1999 Medicare Health Outcomes Survey Cohort II Baseline.

Discussion

Results demonstrate that the Veterans version has greater reliability and precision. The higher Cronbach's alpha or level of precision reflects an improvement in the measurement error of the PCS and MCS role scales of 5 and 6 percent, respectively. The reliabilities of the PCS and MCS also show some improvements. Increased precision was also corroborated by the item convergent validity, reduced floor and ceiling effects, and factor analysis. Multi-trait scaling suggested all scaling successes for the MOS and Veterans versions. Factor analysis yielded comparable two factor structures overall. The factor structure yielded overall variances for the two-factor structure that were greater for the Veterans version than the MOS version, reflecting also the greater precision in the role scales.

With a 5-point set of response choices for each of the items of both role limitation scales, the Veterans version has reduced the floor and ceiling effects. The lowering of the floor effects is of particular importance to health care organizations, which provide care to the elderly or patients with more comorbid conditions. Because the presence of both comorbid medical and mental conditions is likely to influence health status, the assessments of health thus require substantial room, especially at the lower end of the scale, so that the scale may adequately discriminate those who have substantial disease burden and functional limitations from those healthy individuals. The improvement in the floor and ceiling effect indicates that the Veterans version has some advantages over the MOS version.

With regard to the discriminant validity, the results are somewhat mixed. For RP and PCS, the F statistics for medical comparisons (or number of medical comorbidities) are high for both forms (VA and MOS), while the F statistics for mental comparisons (or number of mental comorbidities) are, as expected, relatively low for both forms (VA and MOS). Thus, RP and PCS seem to be good measures of physical health in both surveys. On the other hand, for mental comparisons, while the F statistics for the RE scale are moderate for both the VA and MOS forms, the F statistics for MCS are high for both forms (VA and MOS), with the VA form having a higher F statistic than the MOS form. This finding suggests that compared to the MOS form, the MCS scale of the Veterans SF-36® is more efficient at discriminating between people with different number of mental comorbidities.

It is important to note one limitation of the study, i.e., the study included predominantly male patients who are Medicare beneficiaries and use services from the VA care services where female representation is typically low. We do not know whether the psychometric properties observed in the present study are unique among male patients. As such, the results may not be generalizable to female patients.

Despite these shortcomings, the improvements in the precision of the role scales for the Veterans version are clearly important. The VHA has previously administered both the Veterans version and more recently a shorter Veterans version. More than 2.5 million administrations of the Veterans versions have been fielded nationally since 1996 for purposes of monitoring care. Because of the widespread use of these two versions in various health care organizations, future comparisons of the VHA system with those in Medicare managed care (MMC) may depend on the comparability of the Veterans' version compared with the MOS version.

Future work can examine system comparisons of the VHA and MMC programs to determine if the outcomes of care differ between the two systems. These comparisons will need to consider the differences in scoring the two assessments as well as case-mix differences in the samples requiring careful attention to risk adjustment. Differences between changes in SF-36® scores when making system comparisons may be influenced by the differences in the precision of the Veterans and MOS versions. Responsiveness to change is likely greater in those assessments with greater precision. Future work will need to evaluate these differences.

Recently, other versions of the SF-36® such as the SF-36® Version 2.0 have also been developed with improvements to the precision of former MOS scales (Ware, Kosinski, and Dewey, 2002; Jenkinson et al., 1999; Ware, Kosinski, and Dewey, 2000). These assessments have modified the response choices of the role scales as well as other subscale modifications for purposes of improvements to their reliability and precision.

Conclusions

In summary, the Veterans version is an important assessment tool alternative to the MOS version given improvements to the reliability and precision of the Veterans version for the role scales and the component summaries. The results provide support for the improved reliability and validity of the Veterans version over the MOS version. It also provides evidence that the psychometric properties and measurement characteristics of the Veterans version are at least comparable to the MOS version, and in fact better for selected scales and component summaries. Thus, our results lend support that the two versions can both be used to conduct future system comparisons (MMC programs and the VHA). Uniform standards and metrics for assessing health outcomes across different venues of health care will have added power for these comparisons. Future consideration should be given to apply monitoring systems based on patient centered assessments that are the most reliable and valid for assessing system differences cross-sectionally and over time.

Footnotes

Lewis E. Kazis, Austin Lee, Xinhua S. Ren, Donald R. Miller, Alfredo Selim are with the Health Services Department, Boston University School of Public Health, and the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital. Avron Spiro III is with the Health Services Department, Boston University School of Public Health and the Boston VA Healthcare System. William Rogers is with the New England Medical Center. Alaa Hamed is with the Health Services Department, Boston University School of Public Health. Samuel C Haffer is with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and the University of Maryland Baltimore County. The study was supported by CMS under Contract Number 500-00-0055; Health Services Research and Development Service; the Veterans Health Administration; Center for Health Quality, Outcomes and Economic Research; Bedford VA Medical Center; and Boston University School of Public Health; 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees supported by VA Office of Quality and Performance. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Boston University School of Public Health; the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital; the Boston VA Healthcare System; the Boston University School of Public Health; the New England Medical Center; CMS; or University of Maryland Baltimore County. SF-36® and SF-12® are registered trademarks of the Medical Outcomes Trust.

Reprint Requests: Lewis Kazis Sc.D., Boston University School of Public Health, Health Services Department, T-3W, 80 East Concord Street, Boston, MA 02118. E-mail: LEK@bu.edu

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Internet address: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/otheract/icd9/abticd9.htm. (Accessed 2004.)

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman D. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Second Edition. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood A. Outcomes Management: A Technology of Patient Experience. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;318(23):1549–1556. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806093182327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring Health Related Quality of Life. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993;118:622–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Stewart AL. The Structure of Self-Reported Health in Chronic Disease Patients. In: Kazdin Alan E., editor. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1. Vol. 2. 1990. pp. 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Anderson RB, Revicki DA. Psychometric Considerations in Evaluating Health-Related Quality of Life Measures. Quality of Life Research. 1993;2(6):441–449. doi: 10.1007/BF00422218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEDIS®. National Committee for Quality Assurance; Washington D.C.: 1999, 2000, 2001. Volumes for 1999, 2000, 2001 Specifications for the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey. Internet address: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/surveys/hos/ (Accessed 2004.) [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson C, Stewart-Brown S, Petersen S, Paice C. Assessment of the SF-36® Version 2 in the United Kingdom. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1999;53(1):46–50. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Wilson N. Health Status of Veterans: Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores (SF-36®V): 1996 National Survey of Ambulatory Care Patients. Office of Performance and Quality, and Health Assessment Project, Health Services Research and Development Service; Washington DC, and Bedford, MA.: Mar, 1997. Executive Report. [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Skinner K, Rogers W, et al. Health Status and Outcomes of Veterans: Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores(SF-36®V). 1998 National Survey of Ambulatory Care Patients. Office of Performance and Quality, Health Assessment Project, Health Standards Research and Development Services Field Program; Washington DC, and Bedford, MA.: Jul, 1998a. Mid-Year Executive Report. [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Wilson N, Skinner K, et al. Health Status and Outcomes of Veterans: Physical and Mental Summary Scores (Veterans SF-12). 1998 National Survey of Hospitalized Patients. Office of Performance and Quality, Health Assessment Project, Health Services Research and Development Service Field Program; Washington DC, and Bedford, MA.: Dec, 1998b. Executive Report. [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Skinner K, Rogers W, et al. Health Status of Veterans: Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores (SF-12V). 1997 National Survey of Ambulatory Care Patients. Office of Performance and Quality, Health Assessment Project Health Assessment Project, Health Services Research and Development Service Field Program, VHA National Customer Feedback Center; Washington DC, Bedford and West Roxbury, MA.: Apr, 1998c. Executive Report. [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients Served by the Department of Veterans Affairs: Results from the Veterans Health Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998d Mar;158(6):626–632. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis L, Ren XS, Lee A, et al. Health Status in VA patients: Results from the Veterans Health Study. American Journal of Medical Quality. 1999;14(1):28–38. doi: 10.1177/106286069901400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE. The Veterans SF-36® Health Status Questionnaire: Development and Application in the Veterans Health Administration. Medical Outcomes Trust Monitor. 2000 Jan;5(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Miller DR, Skinner KM, et al. Patient Reported Measures of Health: The Veterans Health Study. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2004;27(1):70–83. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Miller D, Clark JA, et al. Improving Response Choices of the SF-36® Role Functioning Scales: Results from the Veterans Health Study. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2004 doi: 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00010. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Kosinski M, Ware J. Comparisons of the Costs and Quality of Norms for the SF-36 Health Survey Collected By Mail Versus Telephone Interview: Results from a National Survey. Medical Care. 1994a Jun;32(6):551–567. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36®): III. Tests of Data Quality, Scaling Assumptions, and Reliability Across Diverse Patient Groups. Medical Care. 1994b Jan;32(1):40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin J, Kazis LE, Skinner K, et al. Health Status and Outcomes of Veterans: Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores, Veterans SF-36®, 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Quality and Performance; Washington, DC.: May, 2000. Executive Report. [Google Scholar]

- Safran D, Tarlov AR, Rogers W. Primary Care Performance in Fee-for-Service and Prepaid Health Care Systems: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1994 May;271(20):1579–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selim AJ, Fincke G, Ren XS, et al. The Comorbidity Index. In: Davies M, editor. Measuring and Managing Health Care Quality. Second edition. Aspen Publishers; New York, NY.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stevic MO, Haffer SC, Cooper J, et al. How Healthy are Our Seniors?: Baseline Results for the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management. 2000;7(8):39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LM, Dukes KA, Harris L, et al. A Comparison of Various Methods of Collecting Self-Reported Health Outcomes Data Among Low Income and Minority Patients. Medical Care. 1995 Apr;33(Supplement 4):AS183–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarlov AR, Ware JE, Greenfield S, et al. The Medical Outcomes Study: An Application of Methods for Monitoring the Results of Medical Care. JAMA. 1989 Aug;262(7):925–930. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.7.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User's Manual. Health Assessment Lab, New England Medical Center; Boston MA.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to Score Version Two of the SF-36® Health Survey. QualityMetric Incorporated; Lincoln, RI.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Bayliss MS, Rogers WH, et al. Differences in 4-Year Health Outcomes for Elderly and Poor, Chronically Ill Patients Treated in HMO and Fee-for-Service Systems: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1996 Oct;276(13):1039–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to Score Version 2.0 of the SF-36® Health Survey (Standard and Acute Forms) Medical Outcomes Trust and Quality Metric Incorporated; Lincoln, RI.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M. SF-36® Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A Manual for Users of Version 1. Second edition. Quality Metric, Incorporated; Lincoln RI.: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36®-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36®):I. Conceptual Framework and Item Selection. Medical Care. 1992 Jun;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]