Abstract

Stem cell therapy has shown promise in treating a variety of pathologies including skin wounds, but practical applications remain elusive. Here we demonstrate that endogenous stem cell mobilization produced by AMD3100 and low-dose Tacrolimus is able to reduce by 25% the time of complete healing of full-thickness wounds created by surgical excision. Equally important, healing was accompanied by reduced scar and regeneration of hair follicles. Searching for mechanisms, we found that AMD3100 combined with low-dose Tacrolimus mobilized increased number of lineage-negative c-Kit+, CD34+ and CD133+ stem cells. Low-dose Tacrolimus also increased the number of SDF-1 bearing macrophages in the wounds sites amplifying the “pull” of mobilized stem cells into the wound. Lineage tracing demonstrated the critical role of CD133 stem cells in enhanced capillary and hair follicle neogenesis contributing to more rapid and perfect healing. Our findings offer a significant therapeutic approach to wound healing and tissue regeneration.

Introduction

Every year in the United States more than 1.25 million people suffer burns and 6.5 million have chronic skin ulcers caused by pressure, venous stasis, or diabetes mellitus (Singer and Clark, 1999). The treatment of these conditions remains imperfect and expensive. There is hope that stem cell therapy may prove beneficial as it has been increasingly well established that stem cells play an important role in wound healing. For example, artificial skin substitutes have been shown to be more effective when stem cells are incorporated into these membranes. The quality of burn wound healing improves (Leonardi et al., 2012), reducing scar formation and re-establishing the skin appendages (Mansilla et al., 2010; Tamai et al., 2011; Huang and Burd, 2012). The treatment of a chronic static diabetic ulcer has been improved by using the patient's bone marrow (BM) mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in combination with autologous skin fibroblasts embedded on a biodegradable collagen membrane (Coladerm®) (Vojtassák et al., 2006). BM cells from both embryonic and postnatal sources have been shown to repair genetic defects in collagen synthesis and basement membrane defects thereby promoting skin wound healing (Chino et al., 2008; Tolar et al., 2009; Fujita et al., 2010). Recently, a clinical trial found that allogeneic whole BM transplantation in humans suffering from a blistering skin disorder caused by the lack of Col 7 resulted in the restoration of skin integrity and Col 7 expression in basement membranes (Wagner et al., 2010).

Many basic cellular studies have also emphasized the plastic relationships between skin and BM. Fibroblast-like cells in the dermis having hematopoietic and mesenchymal lineages, are derived from BM, and the number of these cells increases after skin wounding (Fathke et al., 2004; Ishii et al., 2005). Donor cells have replaced some keratinocytges after BM transplantation and have persisted in the epidermis for at least 3 years (Körbling et al., 2002). BM cells contribute to fetal skin development as infusion of green fluorescent protein (GFP) BM cells in utero in mice led to the accumulation of GFP-positive cells in the developing dermis, particularly in association with developing hair follicles (Chino et al., 2008).

These abundant studies document the importance of BM stem cells in wound healing and raise the tantalizing possibility that cellular processes can be harnessed to develop practical therapeutic protocols to treat large full thickness burns and massive soft tissue injuries which demand immediate therapy. The promise of improved wound repair by harnessing stem cells is testified by the existence of ninety clinical trials using MSC-based therapies listed in the NIH registry (Cerqueira et al., 2012).

To avoid the preparation of endogenous stem cells which is expensive and time consuming, we proposed in these studies to mobilize endogenous stem cells pharmacologically with AMD3100 and Tacrolimus. AMD3100 has been shown to drive endogenous stem cells from the BM to the blood stream in animals and man (Hendrix et al., 2000; Liles et al., 2003; Devine et al., 2004; Broxmeyer et al., 2005; Hisada et al., 2012). Tacrolimus in low dosages proved to have synergistic effects (Okabayashi et al., 2011), and combination treatment promised a simple, safe, and rapid means of presenting stem cells to injured areas. Here we test this hypothesis in the healing of full thickness skin wounds in mice and rats. Finding this treatment was able to reduce the time for complete healing by 25%, we characterized stem/progenitor cells and related cytokines/growth factors in the wound and substantiated the important role of mobilized CD133+ stem cells in angiogenesis and hair follicle regeneration in wound areas using lineage tracing.

Results

AMD3100 plus low-dose Tacrolimus accelerated wound healing after full-thickness skin excision

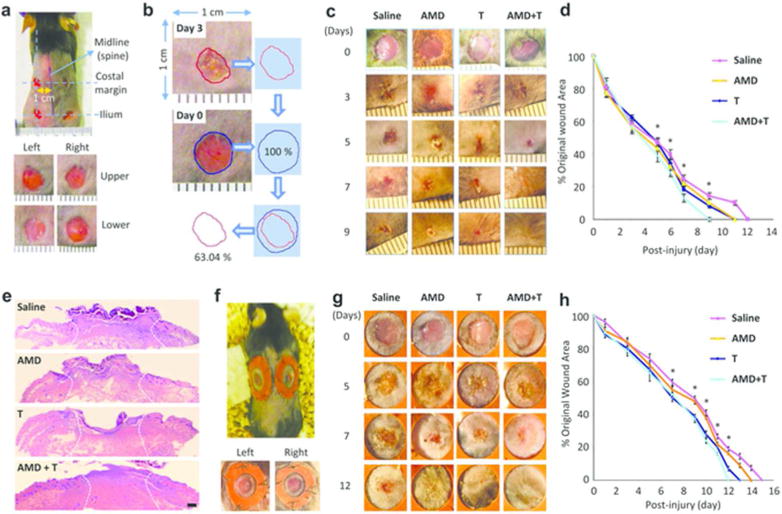

Four full-thickness wounds were generated by 5-mm diameter circular excisions on the shaved back of a wild-type C57/B6 mouse (Figure 1a). Each wound site was photographed digitally at the indicated time intervals, and wound areas were calculated using Adobe Photoshop software. Changes in wound areas over time were expressed as the percentage of the initial wound areas (Figure 1b). Wounded mice were divided randomly into four experimental groups and received subcutaneous injections of saline or drugs immediately after wounding until complete healing: 1) Control group treated with saline, 2) Tacrolimus group treated daily with low-dose (0.1 mg kg-1), 3) AMD3100 group treated every other day (1.0 mg kg-1) and 4) Combination group given low-dose Tacrolimus and AMD3100. All wound evaluations were double blinded.

Figure 1. Accelerated wound healing in mice treated with combination of low-dose Tacrolimus and AMD3100.

(a) The model: on day 0, four circular excisional wounds were created in C57BL/6 or CD133+/C-L mice. (b) Wound measurements. Wound areas were determined using Adobe Photoshop software. (c) Early healing. Representative photographs of wounds in mice (n = 6) showing striking differences beginning at day 5. (d) Quantitative analysis of wound closure in mice (n = 6). * p< 0.05. (e) H&E microphotographs of wounds at day 5. Scale bar: 200 µm. (f) The splinted wound model. (g) Macroscopic analysis of skin wound healing in the splinted mice. (h) Quantitative analysis of wound closure in the splinted mice (n = 6). * p< 0.05. All data represent means ± SEM.

Wounds reached complete closure on day 12 after surgery in group 1 (n = 6) (Figure 1c and d), which is consistent with the known healing kinetics in this established model (Shinozaki et al., 2009; Mack et al., 2012). The 6 animals treated with Tacrolimus or AMD3100 alone exhibited significantly but only moderately faster healing compared to the saline control group (Figure 1d) as wounds reached complete closure at day 11. The healing time was reduced to nine days or by 25% in the group 4 mice treated with AMD3100 plus low-dose Tacrolimus. Digital images showed that treatment with dual drug therapy had significant effects reducing the size of the skin defect as soon as day 5 (Figure 1d), which was the start of the re-epithelialization phase of wound healing. Macroscopically, minimal ulceration and early epithelial ingrowth were observed at the skin boarders on post-wounding day 5 in the dual drug-treated group while wounds in the other three groups showed little if any epithelialization and continued ulceration (Figure 1c and h). We repeated these studies in rats and found that rats receiving dual drug therapy also had the equivalent effect significantly reducing the time for complete healing from 18 to 13 days or 28% (Supplementary Figure S1 online).

Mouse skin is mobile, and contraction accounts for a large part of wound closure. To deter this mechanism, we performed the excisional wound splinting model, where a splinting ring is bonded tightly to the skin around the wound (Figure 1e). The wound therefore heals through granulation and re-epithelialization, a process similar to the healing of most human skin defects. We found that wound repair was accelerated in the splinted wounds treated with low-dose Tacrolimus or AMD3100 monotherapy compared to the control (saline) group while the most accelerated healing was found in animals receiving dual treatment (Figure 1f and g). Thus the therapeutic effects of AMD3100 plus low-dose Tacrolimus were primarily on skin wound epithelialization. Other groups of mice were treated with high-dose AMD3100 (5.0 mg kg-1) or Tacrolimus (1.0 mg kg-1) and we found that high-dose Tacrolimus impeded skin wound healing whereas increased dosage of AMD3100 showed no significant difference (Supplementary Figure S2 online).

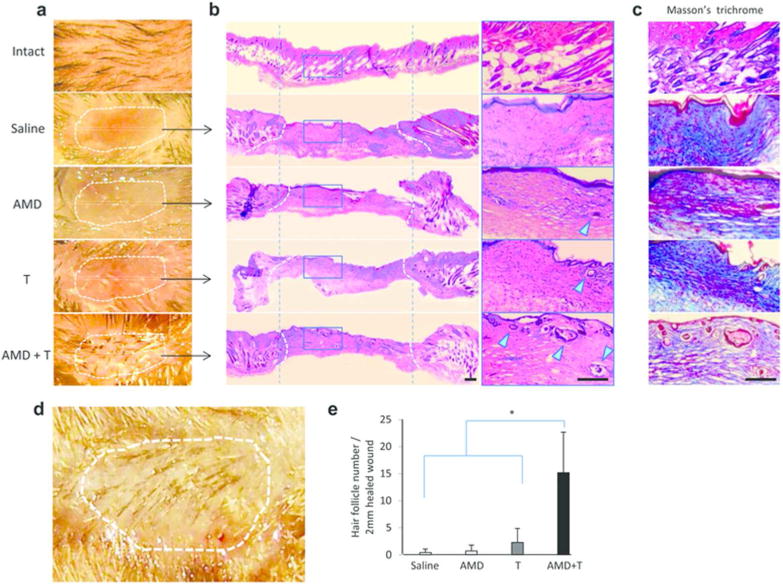

AMD3100 plus low-dose Tacrolimus ameliorated scar formation and promoted hair follicle regeneration

Dermal wound repair commences with the arrest of hemorrhage followed by an inflammatory response, formation of granulation tissue within the wound space, fibrosis, and re-epithelization of the wound, culminating in the production of a scar.

Histologically, the re-epithelialized wound in the control groups on day 15 showed a disorganized epidermis, with blurring of the boundary between the epidermis and the dermis (Figure 2b). There were few hair follicles in the group 1, 2 and 3 mice and collagen was abundant and disorganized (Figure 2c), which is in agreement with the results of published studies (Devine et al., 2004). By contrast, the dual drug treated animals had a thin and well organized epidermis with well-formed hair follicles and much better organized collagen (Figure 2b and c; lower panels). The most striking finding was that hair appeared only in the re-epithelialized wound in the dual drug treated animals after 15 days (Figure 2a and d). Not surprisingly, the number of hair follicles in the tissue sections of re-epithelialized wound was significantly higher in the dual drug treated animals compared to the control groups (Figure 2e). We found that dual drug treatment also stimulated hair follicle neogenesis and reduced scarring in rats (Supplementary Figure S3 online). Thus the combination of low-dose Tacrolimus and AMD3100 improved wound healing by promoting both re-epithelialization and differentiation of skin components.

Figure 2. Increased hair follicle regeneration and diminished scarring in healed skin of mice treated with dual drug therapy.

(a) Representative macroscopic appearance of re-epithelialized wounds (day 15). (b) Representative microscopic H&E-stained sections from the middle of scars show new hair follicles within healed wounds. The scarred area is outlined by broken lines. Two vertical dotted lines help to demarcate the regions with the same length as that of the healed scar area in saline-treated group. Scale bar: 200 µm. (c) Adjacent sections stained with Masson's trichrome. (d) Representative photographs of dual drug-treated animals at 15 days postwounding showing hair growth in the re-epithelialized wound. (e) Quantification of follicles within the healed scars (2 mm). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 9). * p < 0.01.

AMD3100 and low-dose Tacrolimus synergistically mobilized lineage negative (Lin-) cells bearing stem cell markers for c-Kit+, CD34+, and CD133+ whereas low-dose Tacrolimus increased the number of SDF-1 producing macrophages

We performed flow cytometry on blood samples to determine the stem cell constituents mobilized by treatment with AMD3100 and Tacrolimus. The numbers of Lin-, c-Kit, CD34+, CD133+ cells and Lin- Triple positive (c-Kit+ CD34+ CD133+) cells were significantly greater in peripheral blood (Figure 3a) in the animals receiving combination drug treatment at 5 days post-injury. Immunofluorescence staining of wound tissue sections showed that the number of CD133+ was increased by combination treatment as were c-Kit+ and CD34+ cells (Figure 3b). These cells were found particularly in newly formed granulation tissues of the wounds. Interestingly, at this 5 day time point, many CD133+ cells co-stained with CD31, a marker of endothelial cells (Figure 3b; right panels). The number of CD133+ cells declined at day 7, but remained detectable at day 9 after wound closure. In contrast, CD31+ cells increased in a time-dependent fashion (Supplementary Figure S4 online).

Figure 3. Recruitment of BM stem cells with dual drug therapy.

(a) Quantitative analysis of Lineage negative (Lin-) c-Kit+, CD34+ and CD133+ cells in peripheral blood by flow cytometry at 5 days after injury. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3). * p < 0.05. (b) Immunofluorescence staining for stem cell markers c-Kit, CD34 and CD133 and endothelial cells marker CD31 in tissue sections from wounded mice at 5 days after injury. Boxed areas demonstrate at higher magnification that the mice receiving dual drug treatment had a tubular arrangement of CD133 cells which co-stained for CD31. Cell nuclei were stained blue with DAPI. Representative photographs of n = 3 individual injured skin samples per group. epi, epidermis; we, wound edge. Scale bar: 200 µm.

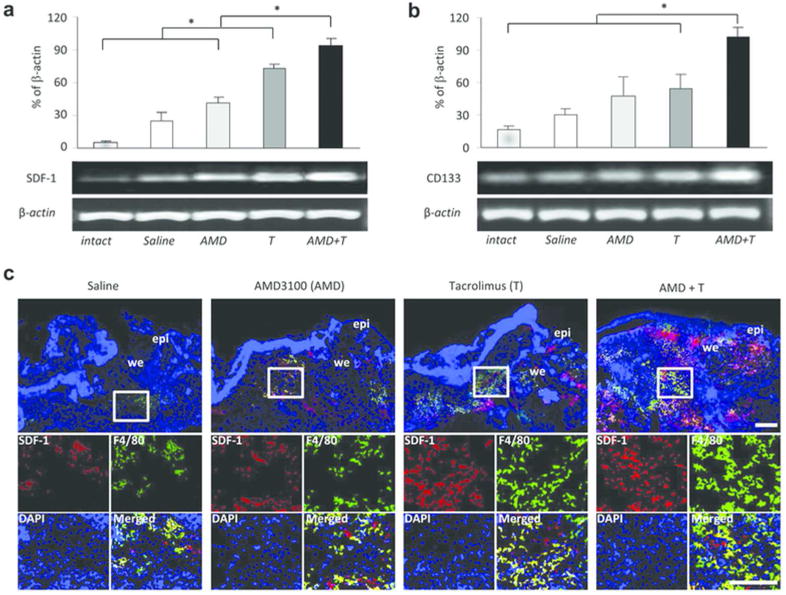

Semi-quantitative PCR analysis of the granulation tissues showed that mRNA expression of the attractor molecule, stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1 and stem cell marker CD133 were significantly increased in the group 4 mice compared to groups 1, 2 and 3 at 5 days after wounding (Figure 4a and b). Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that the number of cells having SDF-1 and F4/80 (a marker of macrophages) markers significantly greater in wound sites in the animals receiving low-dose Tacrolimus alone or those receiving dual drug treatment at 5 days post-injury (Figure 4c). Interestingly, SDF-1 co-stained with some of the F4/80+ cells indicating that these macrophages were producing or presenting SDF-1 (Figure 4c; lower panels).

Figure 4. Increased expression of SDF-1 and CD133 in skin wounds of the mice treated with dual drug therapy.

(a) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the granulation tissues in wounded skin at 5 days post-injury. The mRNA expression of the attractor molecule SDF-1 was significantly increased in the low-dose Tacrolimus treatment group, and further elevated in the dual treatment group. (b) The stem cell marker CD133 mRNA level was also significantly higher in wounds in the dual treatment group, paralleling SDF-1 gene expression. All data represent means ± SEM. (n = 3). * p < 0.05. (c) Double immunofluorescence staining for SDF-1 and F4/80 (a marker for macrophages) at 5 days after injury. epi, epidermis; we, wound edge. Scale bar: 200 µm.

To demonstrate the critical role of SDF-1 mediated stem/progenitor cell mobilization in the improved wound healing, inactivation of SDF-1was achieved by local intradermal injection of anti-SDF-1 antibodies (Abs) in the group 4 mice once a day until wounds were closed (Supplementary Figure S5 online). Control wounds were injected with the same volume of mouse IgG at the same time. CD133+ CD31+ cells and mRNA expression of CD133 were significantly decreased in the wounds receiving anti-SDF-1 antibodies at 5 days post injury. By contrast the number of these cells increased in the wounds treated with control mouse IgG (Supplementary Figure S5d-e online). However, the number of F4/80+ macrophages remained the same indicating they were mobilized by a different mechanism. These diminished stem cell responses led to the delayed wound closure in the dual drug treated mice (Supplementary Figure S5c online). Thus inactivation of SDF-1 eliminated the beneficial effect of dual drug therapy.

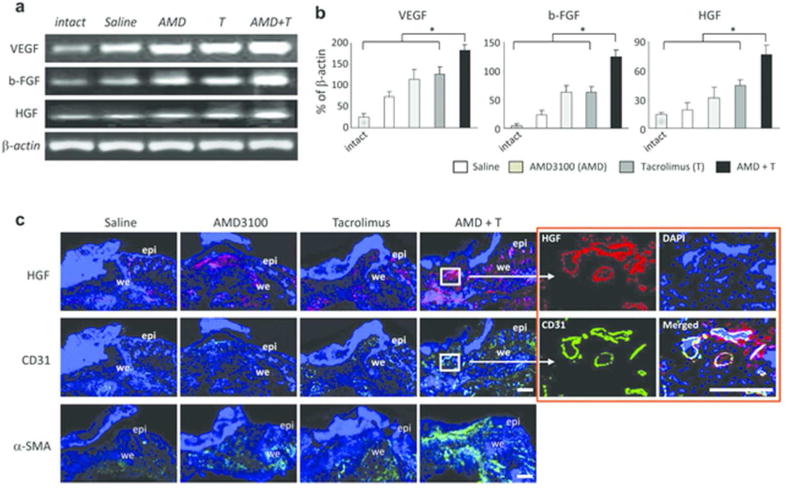

Dual drug treatment increased the expression of angiogenic cytokines at five days post wounding

Semi-quantitative PCR analysis of the granulation tissues showed that mRNA expression of the angiogenic cytokines, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF), and an important stem cell mobilizing and homing factor, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), were all significantly increased in the group 4 mice compared to group 1, 2 and 3 (Figure 5a and b). Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that the number of HGF positive cells was significantly greater in the granulation tissues recovered from the group 4 mice 5 days post-injury. Similarly, the number of CD31+ endothelial cells in the granulation tissues was markedly increased in the group 4 mice compared to the group 1, 2 and 3. Some of these CD31+ cells formed tube-like structures (Figure 5c; right panels) in the granulation tissues which also stained for HGF emphasizing the important role of HGF in neovascularization. The tubular structures also co-stained with CD133 (Figure 3b; right panels) suggesting that HGF may be involved in the differentiation of endothelial cells from CD133 precursors.

Figure 5. Increased pro-angiogenic factor expressions in injured mice treated with dual drug therapy.

(a) Semi-quantitative PCR analysis of the granulation tissues (day 5) showing the up-regulation of mRNA of VEGF, bFGF and HGF. (b) Graphic representation of increased mRNA expressions determined by calculating growth factor to β-actin ratios. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 3). * p < 0.05. (c) Double fluorescence staining shows that the major fraction of HGF expressing cells co-stain for the endothelial marker CD31 in granulation tissues (day 5), and that these cells are more abundant in the dual treatment group. Panels in the lower row are stained for α-SMA and show the abundance of these matrix producing cells, paralleling the findings for CD31. epi, epidermis; we, wound edge. Scale bar: 200 µm.

We sought evidence of enhanced production of cells contributing to matrix and indeed immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that the number of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) positive myofibroblast cells increased in the granulation tissues recovered from the group 2 and 3 mice compared to the group 1, while group 4 mice clearly recruited more myofibroblasts in the granulation tissues at five days (Figure 5c; lower panels).

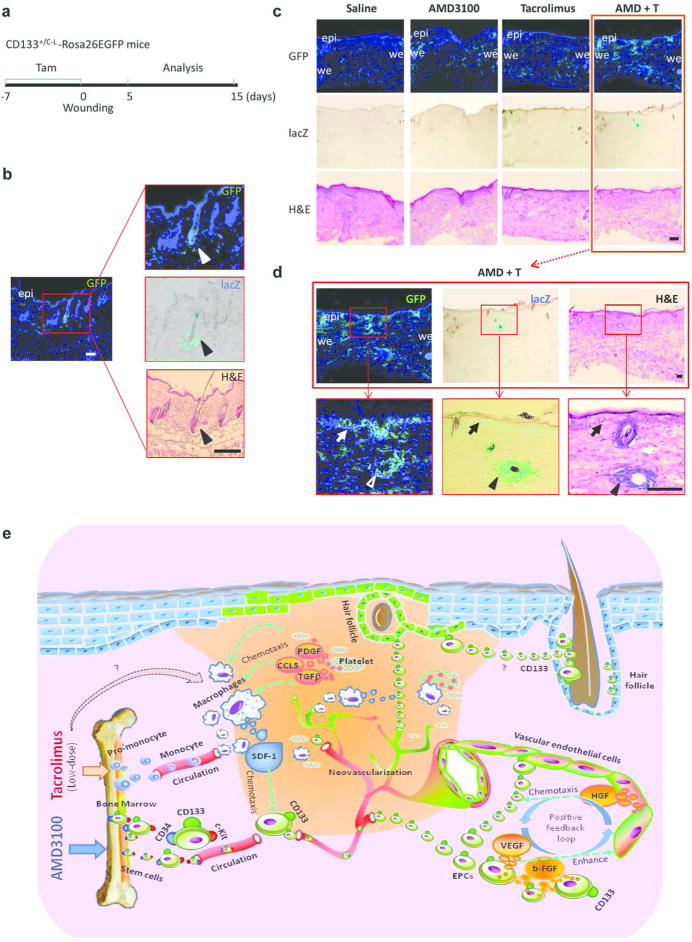

Lineage tracing demonstrated the critical role of CD133 stem cells in improving wound healing by the combination of AMD3100 and low-dose Tacrolimus

Lineage tracing studies were performed to confirm the critical role of CD133 stem cells in wound healing. Adult CD133+/C-L mice containing the Rosa26GFP reporter allele (CD133+/C-L X mTmG offspring) were used. CreERT2 activity was induced with tamoxifen 7 days before wounding (Figure 6a). In this mouse model, progenitor CD133 cells were lacZ positive whereas the CD133 progeny were GFP positive. LacZ and GFP positive cells were observed only in the hair follicles of intact mouse skins (Figure 6b) as reported by others (Charruyer et al., 2012).

Figure 6. CD133+ stem cells generate hair follicles and epithelium in the CD133+/C-L mice with dual treatment group.

(a) Protocol for analysis of the tamoxifen-induced Cre-dependent GFP expression in CD133-lineage. (b) Intact mouse skin tissues shows marked GFP and CD133 (lacZ+) expression in the hair follicles. Scale bar: 200 µm. (c) Concurrent GFP fluorescence, β-galactosidase (lacZ) and H&E staining of the same section of CD133+/C-L-Rosa26EGFP wounded skin on day 15 postinjury. Scale bar: 200 µm. (d) Higher power photomicrographs. In the boxed areas arrowheads marked the hair follicles in the same section stained for GFP+ (left panel), lacZ+ (middle panel) and H&E (right panel). Arrows point to the GFP and lacZ positive epithelium. epi, epidermis; we, wound edge. Scale bar: 100 µm. (e) Schematic representation of therapeutic mechanism of combination treatment in skin wound healing.

Both lacZ and GFP positive cells were increased in the granulation tissues at 5 days after wounding (Supplementary Figure S6 online; upper and middle panels). The numbers of lacZ and GFP positive cells were significantly higher in the granulation tissues recovered from the group 2 and 3 mice compared to the group 1, but greatest numbers of lacZ and GFP positive cells were found in the granulation tissues of the group 4 mice (Supplementary Figure S6 online). Most of the LacZ positive cells disappeared at 15 days in groups 1, 2 and 3, while their progeny CD133 GFP positive cells remained in the healed tissues (Figure 6c). However, in group 4 mice newly generated vasculature, epidermis and hair follicles remained positive for both LacZ and GFP (Figure 6d). These results imply that pharmacologically mobilized CD133 stem cells and their progeny are the principle contributors to skin regeneration.

Discussion

AMD3100 (Plerixafor or Mozobil), is a direct antagonist of CXCR4 and has been used clinically to drive hematopoietic stem cells out of the BM into the peripheral blood of humans where they can be recovered and preserved until the completion of ablative irradiation and/or chemotherapy. AMD3100 has also found application in the repairs of tissue injuries (Jujo et al., 2010, 2013; Nishimura et al., 2012). The injection of a single dose augmented the mobilization of BM derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), which was associated with more rapid neovascularization and functional recovery after myocardial infarction in mice (Jujo et al., 2010). After ischemia/reperfusion injury (Jujo et al., 2013), acute injections redistributed proangiogenic BM cells to ischemic myocardium in an endothelial nitric oxide synthase dependent fashion and promoted the recovery of cardiac function in mice. A single topical application of AMD3100 promoted wound healing in diabetic mice (Nishimura et al., 2012) which was associated with increased cytokine production, increased numbers of bone marrow EPCs, and increased activity of fibroblasts and monocytes/macrophages. Both angiogenesis and vasculogenesis were increased (Nishimura et al., 2012). Our results confirmed and significantly extended these findings. Indeed AMD3100 monotherapy resulted in mild recruitment of stem cells into the wound sites and shortened wound healing to a modest degree (Figure 3b). Our important contribution is the finding that combining low-dose Tacrolimus with AMD3100 led to a much greater accumulation of stem cells and more rapid regeneration of normal skin in our rodent models of full-thickness skin excision. Tacrolimus given at one tenth the immunosuppressive dose had profound, synergistic effects with AMD3100 in the recruitment of stem cells into the blood stream and wounds, particularly those carrying combined monocyte and SDF-1 markers.

Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor and a potent immunosuppressive drug. But surprisingly is also augments cell regeneration and repair in sub-immunosuppressive dosages (Francavilla et al., 1989; Carroll et al., 1994; Gold, 1997). Low dosages (0.1 mg kg-1), but not standard immune-suppressive dosages (1.0 mg kg-1) of Tacrolimus promoted healing of colon anastomoses in rats (Kiyama et al., 2002). Tacrolimus treatment facilitated the healing of lower extremity skin ulcers in a 75-year old woman with lichen planus and diabetes mellitus (Miller, 2008). Bai et al. (Bai et al., 2010) showed in vitro that low (20 ng ml-1)- but not high (2,000 ng ml-1)-dose Tacrolimus treatment skewed BM-derived macrophage polarization towards an active M2 macrophage phenotype. In our study, we also demonstrated that low-dose Tacrolimus improved skin wound healing was associated with a significant increase in the numbers of macrophages in the skin wound co-staining with SDF-1 on the fifth postoperative day. We could not distinguish whether these cells secreted SDF-1 or presented it on their cell membranes.

To dramatize the importance of SDF-1 we inactivated it by local intradermal injection of anti-SDF-1 antibodies. This led to diminished stem cell responses and to the delayed wound closure in the dual drug treated mice. Control dual treated mice injected with equal amounts of isotype control IgG healed normally thereby emphasizing the critical role of SDF-1 mediated stem/progenitor cell mobilization in the improved wound healing. Thus, a strong “push” of stem cells from their BM niches by AMD3100 and a strong “pull” of circulating stem cells by factors in the wound sites enhanced by low-dose Tacrolimus best explains why there was a greater accumulation of stem cells in wound sites and more rapid restoration of normal skin with dual AMD3100/Tacrolimus treatment.

The recruitment of stem cells by dual drugs was associated with elevated expression of VEGF, b-FGF and HGF mRNA in the wounds. Interestingly, anti-HGF antibody co-stained with CD31+ cells that were also CD133+ (Figure 5c). HGF has many stimulatory actions and has been shown to be a potent regulator of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells proliferation and differentiation (Nishino et al., 1995), as well as a powerful stimulator of angiogenesis (Ding et al., 2003). It also has been shown that HGF exerts a strong chemotactic effect on MSCs in a wound-healing model (Neuss et al., 2004). Thus, dual drug treatment facilitated the accumulation of SDF-1 producing macrophages which led to the recruitment of more stem cells. In turn the elaboration of HGF, and other autocrine or paracrine mediators produced more pro-angiogenic factors completing positive feedback loops (Figure 6e).

CD133 stem cells played a vital role in neovascularization and hair follicle regeneration which is essential for perfect skin regeneration (Sun et al., 2011). Such cells have the potential to differentiate along endothelial lineages in vitro (Hollemann et al., 2012) and are known to migrate to sites of neovascularization in response to mediators (VEGF and SDF-1). Immunofluorescence double staining demonstrated that many CD133 cells co-stained with CD31 (Figure 2b), an early endothelial cell marker. During the maturation process, the CD133 marker waned and the CD31 phenotype gained (Hollemann et al., 2012). Enhanced angiogenesis was associated with increased numbers of infiltrating CD133+CD31+ progenitor cells in the wound sites and strengthens the role of these cells in neovascularization.

Epidermal and hair follicle stem cells can undergo reprogramming to become repopulating epidermal progenitor cells following wounding (Ito et al., 2005). Lineage analysis has also demonstrated that follicles can arise from cells outside of the hair follicle stem cell niche, suggesting that cells found in the epidermis can assume a hair follicle stem cell phenotype (Ito et al., 2007). A recent study reported that CD133 is a marker for long-term repopulating murine epidermal stem cells and CD133+ keratinocytes formed both hair follicles and epidermis after injection into immunodeficient mice (Charruyer et al., 2012). Our lineage tracing studies demonstrated the presence of CD133+ cells in the hair follicles of intact skin (Figure 6b). While it is clear from our lineage tracing studies that increased numbers of CD133 stem cells contributed to hair follicle regeneration and that these cells were liberated from the bone marrow by dual treatment, it is possible these CD133+ stem cells originate from normal skin. We consider this unlikely for several reasons. Our lineage tracing study did not show the expansion of CD133+ cells in the hair follicles of intact skin adjacent the wound sites. Rather CD133+ cells accumulated in the central granulation tissues rather than the wound edges. Further the number of CD133+ cells in the wound sites correlated with the number of CD133+ cells in peripheral blood.

The mechanisms responsible for the BMSC mobilizing effects of low-dose Tacrolimus remain fascinating but unknown, but probable unrelated to calcineurin inhibition for several reasons. Low dosage such as those we used do not inhibit calcineurin. Cyclosporin A, a known calcineurin inhibitor was ineffective. Lastly tacrolimus is known to have cellular binding proteins. A recent paper (Spiekerkoetter et al., 2013) reported that low dose Tacrolimus activated a bone morphogenic protein receptor (BMPR-2) signaling which may stimulate SDF-1 expression in macrophages.

In conclusion, we report here that a previously unreported therapeutic strategy designed to mobilize endogenous stem cells into skin wounds results in better and faster healing. The magnitude of both the quantitative and qualitative differences is highly significant and is greater than that found in any other study of wound healing in normal animals. Our studies do not disclose the molecular mechanisms which differentiate these malleable cells into tissue components such as reported for Fgf9 (Gay et al., 2013) or Sept4/ARTS (Fuchs et al., 2013). However, the differentiating steps leading to healing with skin appendages proceeded faultlessly when there were abundant stem cells producing almost normal skin. This is our report demonstrating the profound synergistic effects of AMD3100 and low-dose Tacrolimus in the mobilization, recruitment, and retention of endogenous stem cells leading to faster healing and differentiation into all of the tissues present in normal skin. These findings may be easily applied in the clinic.

Materials and Methods

Details can be obtained from the online supplementary materials.

Animals

C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), CD133+/C-L mice (obtained from St Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN) (Zhu et al., 2009), mT/mG mice (kindly provided by Dr. Steven D. Leach) (Muzumdar et al., 2007) and DA (RT1Aa) rats (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) were cared for according to NIH guidelines and under a protocol approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care Committee.

In vivo excisional wound model

Full-thickness wounds were created in the dorsal skin (Tomlinson and Ferguson, 2003) of mice (Figure 1a), splinted mice (Figure 1f; Galiano et al., 2004) and rats (Supplementary Figure S1a online) with a sterile disposable biopsy punch (5 mm in diameter) (Figure 1a and Supplementary Figure S1a online). The animals were injected subcutaneously with AMD3100 or Tacrolimus.

Histology and microscopy

GFP microscopy, LacZ analysis and H&E staining were performed on skin sections from tamoxifen-treated CD133+/C-L mice. For hair neogenesis analysis, the number of regenerated hair follicles in the wound area (H&E-stained) was quantified in a double-blind fashion. Immunofluorescence staining were performed using anti-CD133, -CD34, -c-Kit, -SDF-1, -F4/80, -α-SMA, -CD31 or -HGF antibodies.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspension of peripheral blood was analyzed for expression of lineage negative c-Kit+, CD34+ and CD133+ stem cell markers by flow cytometry using CELLQuest software (Becton-Dickinson, Bedford, MA).

Semiquantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNAs were extracted from the skin specimens and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed. The expression levels of target mRNA were quantified by densitometry and normalized with the corresponding internal control.

Statistics

Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± SEM. Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA was performed as described in the supplementary information. The p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. AMD3100 treatment with low-dose Tacrolimus improved the rate of wound closure in injured rats. (a) Illustrative photographs of the rat model of full-thickness excisional wounds. The wound areas of 5-mm punch biopsies were measured at the indicated time intervals until reaching complete closure. (b) Kinetic analysis of rat skin wound healing. Representative images of n = 6 animals per group are showed. (c) Percent wound area at each time point relative to the original wound area was showed. Data represent mean ± SEM of n = 6 animals per group. * p < 0.05 dual treated vs. vehicle treated rats.

Figure S2. Effects of Tacrolimus and AMD3100 in high doses on mouse skin wound healing. (a) Kinetic analysis of skin excisional wound healing. Wound sites were photographed at the time indicated. Representative photographs of n = 3 or 4 animals per group. (b) Changes in percentage of wound area at each time point in comparison to the original wound area. Data represent mean ± SEM of n = 3 or 4 animals per group. Quantitative evaluation failed to demonstrate significant difference of wound closure in the mice treated with Tacrolimus (1.0 mg kg-1) or AMD3100 (5.0 mg kg-1) as compared with that in saline treated mice.

Figure S3. Dual drug treatment stimulates hair follicle neogenesis and reduces scarring in rat skin after wounding. A rat model of full thickness skin excision as described above. (a) Hair follicle regeneration was assessed by H&E (left and middle panels) and Masson's trichrome (right panels) staining at post-wounding day 20. Representative images of n = 12 individual skin samples per group are shown: scar outlined with broken lines, and arrowheads point to the neogenic hair follicles within healed scars. Scale bar: 200 μm. (b) Quantification of regenerated follicles within rat healed scars (2 mm) or intact skin. Data represent mean ± SEM of n = 12 individual samples per group. * p < 0.05.

Figure S4. CD133+CD31+ stem/progenitor cell accumulation in wounded skin of the mice treated with dual drug therapy. A double-color immunofluorescence analysis of wound sites of AMD+T-treated mice was performed using Cy3-labeled anti-CD133 and FITC-labeled anti-CD31 Abs at postinjury day 3, 5, 7 and 9 (the day that complete healing occurred). Representative photographs of n = 4 individual skin samples per group. epi, epidermis; we, wound edge. Bar = 200 urn.

Figure S5. The critical role of SDF-1 mediated stem/progenitor cell mobilization in the improved wound healing. (a) Inactivation of SDF-1was achieved by local intradermal injection of anti-SDF-1 antibodies (Abs) in mice receiving the dual drug therapy. (b) Representative images (n = 6) of wounds treated with anti-SDF-1 Abs or control IgG. Saline treatment was served as a control. (c) Wound closure rate. Data represent means ± SEM (n = 6). * p< 0.05. (d) and (e) Double immunofluorescence staining for SDF-1 (red) and F4/80 (green) or CD133 and CD31 in tissue sections from the wounds treated with control IgG or anti-SDF-1 antibodies in mice receiving the dual drug therapy at day 5 after injury. Inactivation of SDF-1 diminished CD133+ and CD31+ cell responses without affecting macrophage (F4/80+) accumulation in the wounds. (f) Local intradermal Injection of anti-SDF-1 antibodies eliminate the elevation of CD133 mRNA expression. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 3). * p < 0.05

Figure S6. CD133+ stem cells generate blood vessels in the wounded skin of CD133+/C-L mice in the dual treatment group. Concurrent GFP-fluorescence (upper panels), β-galactosidase (middle panels) and H&E staining (lower panels) of the same section of CD133+/C-L wounds on day 5 postinjury points to CD133+ progenitor cells as one of the sources of newly formed capillaries particularly in the dual treated CD133+/C-L mice. Boxed regions are shown at higher magnification to the right. Arrows point to the GFP+ (upper panel) lacZ+ (middle panel) capillaries (H&E, lower panels) in the same section. epi, epidermis; we, wound edge. Scale bar: 200 μm.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard J. Gilbertson (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital) for providing CD133+/C-L mice and Dr. Liqing Zhu (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital) for help with genotyping of CD133+/C-L-RosaGFP mice. We also thank Dr. Steve D. Leach (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) for providing mTmG mice. This project was supported by departmental start-up fund (Z.S.).

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance, b-FGF, basic fibroblast growth factor, BM, bone marrow

- CD133+/C-L

CD133 positive-Cre-nuclear(n)LacZ

- CXCR4

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- Lin-

lineage negative

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor-1

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SMA

smooth muscle actin

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Z.S., G.M.W. and Q.L. are listed as inventors in a patent application related to this work. The other authors state no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material: The following materials is available from http://www.nature.com/jid

References

- Bai L, Gabriels K, Wijnands E, et al. Low- but not high-dose FK506 treatment confers atheroprotection due to alternative macrophage activation and unaffected cholesterol levels. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:143–50. doi: 10.1160/TH09-07-0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1307–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll PB, Rilo HL, Abu Elmagd K, et al. Effect of tacrolimus (FK506) in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: rationale and preliminary results. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1457–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.130.11.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira MT, Marques AP, Reis RL. Using stem cells in skin regeneration: possibilities and reality. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:1201–14. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charruyer A, Strachan LR, Yue L, et al. CD133 is a marker for long-term repopulating murine epidermal stem cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2522–33. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chino T, Tamai K, Yamazaki T, et al. Bone marrow cell transfer into fetal circulation can ameliorate genetic skin diseases by providing fibroblasts to the skin and inducing immune tolerance. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:803–14. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine SM, Flomenberg N, Vesole DH, et al. Rapid mobilization of CD34+ cells following administration of the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 to patients with multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1095–102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S, Merkulova-Rainon T, Han ZC, et al. HGF receptor up-regulation contributes to the angiogenic phenotype of human endothelial cells and promotes angiogenesis in vitro. Blood. 2003;101:4816–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathke C, Wilson L, Hutter J, et al. Contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to skin: collagen deposition and wound repair. Stem Cells. 2004;22:812–22. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francavilla A, Barone M, Todo S, et al. Augmentation of rat liver regeneration by FK 506 compared with cyclosporin. Lancet. 1989;2:1248–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91853-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs Y, Brown S, Gorenc T, et al. Sept4/ARTS regulates stem cell apoptosis and skin regeneration. Science. 2013;341:286–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1233029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Abe R, Inokuma D, Sasaki M, et al. Bone marrow transplantation restores epidermal basement membrane protein expression and rescues epidermolysis bullosa model mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000044107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiano RD, Michaels J, 5th, Dobryansky M, et al. Quantitative and reproducible murine model of excisional wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12:485–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay D, Kwon O, Zhang Z, et al. Fgf9 from dermal γδ T cells induces hair follicle neogenesis after wounding. Nat Med. 2013;19:916–23. doi: 10.1038/nm.3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold BG. FK506 and the role of immunophilins in nerve regeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 1997;15:285–306. doi: 10.1007/BF02740664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix CW, Flexner C, MacFarland RT, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of AMD-3100, a novel antagonist of the CXCR-4 chemokine receptor, in human volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1667–73. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1667-1673.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisada M, Ota Y, Zhang X, et al. Successful transplantation of reduced-sized rat alcoholic fatty livers made possible by mobilization of host stem cells. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:3246–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollemann D, Yanagida G, Rüger BM, et al. New vessel formation in peritumoral area of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2012;34:813–20. doi: 10.1002/hed.21814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Burd A. An update review of stem cell applications in burns and wound care. Indian J Plast Surg. 2012;45:229–36. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.101285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii G, Sangai T, Sugiyama K, et al. In vivo characterization of bone marrow-derived fibroblasts recruited into fibrotic lesions. Stem Cells. 2005;23:699–706. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Liu Y, Yang Z, et al. Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis. Nat Med. 2005;11:1351–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Yang Z, Andl T, et al. Wnt-dependent de novo hair follicle regeneration in adult mouse skin after wounding. Nature. 2007;447:316–20. doi: 10.1038/nature05766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jujo K, Hamada H, Iwakura A, et al. CXCR4 blockade augments bone marrow progenitor cell recruitment to the neovasculature and reduces mortality after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11008–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914248107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jujo K, Ii M, Sekiguchi H, Klyachko E, et al. CXC-chemokine receptor 4 antagonist AMD3100 promotes cardiac functional recovery after ischemia/reperfusion injury via endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent mechanism. Circulation. 2013;127:63–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.099242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyama T, Tajiri T, Tokunaga A, et al. Tacrolimus enhances colon anastomotic healing in rats. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10:308–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2002.t01-1-10506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körbling M, Katz RL, Khanna A, et al. Hepatocytes and epithelial cells of donor origin in recipients of peripheral-blood stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:738–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa3461002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi D, Oberdoerfer D, Fernandes MC, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells combined with an artificial dermal substitute improve repair in full-thickness skin wounds. Burns. 2012;38:1143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles WC, Broxmeyer HE, Rodger E, et al. Mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in healthy volunteers by AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Blood. 2003;102:2728–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack JA, Feldman RJ, Itano N, et al. Enhanced inflammation and accelerated wound closure following tetraphorbol ester application or full-thickness wounding in mice lacking hyaluronan synthases Has1 and Has3. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:198–207. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla E, Spretz R, Larsen G, et al. Outstanding survival and regeneration process by the use of intelligent acellular dermal matrices and mesenchymal stem cells in a burn pig model. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:4275–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.09.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. The effect of tacrolimus on lower extremity ulcers: a case study and review of the literature. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2008;54:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, et al. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuss S, Becher E, Wöltje M, et al. Functional expression of HGF and HGF receptor/c-met in adult human mesenchymal stem cells suggests a role in cell mobilization, tissue repair, and wound healing. Stem Cells. 2004;22:405–14. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y, Ii M, Qin G, et al. CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 accelerates impaired wound healing in diabetic mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:711–20. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino T, Hisha H, Nishino N, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor as a hematopoietic regulator. Blood. 1995;85:3093–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabayashi T, Cameron AM, Hisada M, et al. Mobilization of host stem cells enables long-term liver transplant acceptance in a strongly rejecting rat strain combination. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2046–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki M, Okada Y, Kitano A, et al. Impaired cutaneous wound healing with excess granulation tissue formation in TNFalpha-null mice. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:531–7. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-0969-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiekerkoetter E, Tian X, Cai J, et al. FK506 activates BMPR2, rescues endothelial dysfunction, and reverses pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3600–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI65592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Zhang X, Shen YI, et al. Dextran hydrogel scaffolds enhance angiogenic responses and promote complete skin regeneration during burn wound healing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20976–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115973108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai K, Yamazaki T, Chino T, et al. PDGFRalpha-positive cells in bone marrow are mobilized by high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) to regenerate injured epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6609–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016753108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar J, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Riddle M, et al. Amelioration of epidermolysis bullosa by transfer of wild-type bone marrow cells. Blood. 2009;113:1167–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-161299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson A, Ferguson MW. Wound healing: a model of dermal wound repair. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;225:249–60. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-374-7:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vojtassák J, Danisovic L, Kubes M, et al. Autologous biograft and mesenchymal stem cells in treatment of the diabetic foot. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2006;27(Suppl 2):134–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JE, Ishida-Yamamoto A, McGrath JA, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:629–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Gibson P, Currle DS, et al. Prominin 1 marks intestinal stem cells that are susceptible to neoplastic transformation. Nature. 2009;457:603–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. AMD3100 treatment with low-dose Tacrolimus improved the rate of wound closure in injured rats. (a) Illustrative photographs of the rat model of full-thickness excisional wounds. The wound areas of 5-mm punch biopsies were measured at the indicated time intervals until reaching complete closure. (b) Kinetic analysis of rat skin wound healing. Representative images of n = 6 animals per group are showed. (c) Percent wound area at each time point relative to the original wound area was showed. Data represent mean ± SEM of n = 6 animals per group. * p < 0.05 dual treated vs. vehicle treated rats.

Figure S2. Effects of Tacrolimus and AMD3100 in high doses on mouse skin wound healing. (a) Kinetic analysis of skin excisional wound healing. Wound sites were photographed at the time indicated. Representative photographs of n = 3 or 4 animals per group. (b) Changes in percentage of wound area at each time point in comparison to the original wound area. Data represent mean ± SEM of n = 3 or 4 animals per group. Quantitative evaluation failed to demonstrate significant difference of wound closure in the mice treated with Tacrolimus (1.0 mg kg-1) or AMD3100 (5.0 mg kg-1) as compared with that in saline treated mice.

Figure S3. Dual drug treatment stimulates hair follicle neogenesis and reduces scarring in rat skin after wounding. A rat model of full thickness skin excision as described above. (a) Hair follicle regeneration was assessed by H&E (left and middle panels) and Masson's trichrome (right panels) staining at post-wounding day 20. Representative images of n = 12 individual skin samples per group are shown: scar outlined with broken lines, and arrowheads point to the neogenic hair follicles within healed scars. Scale bar: 200 μm. (b) Quantification of regenerated follicles within rat healed scars (2 mm) or intact skin. Data represent mean ± SEM of n = 12 individual samples per group. * p < 0.05.

Figure S4. CD133+CD31+ stem/progenitor cell accumulation in wounded skin of the mice treated with dual drug therapy. A double-color immunofluorescence analysis of wound sites of AMD+T-treated mice was performed using Cy3-labeled anti-CD133 and FITC-labeled anti-CD31 Abs at postinjury day 3, 5, 7 and 9 (the day that complete healing occurred). Representative photographs of n = 4 individual skin samples per group. epi, epidermis; we, wound edge. Bar = 200 urn.

Figure S5. The critical role of SDF-1 mediated stem/progenitor cell mobilization in the improved wound healing. (a) Inactivation of SDF-1was achieved by local intradermal injection of anti-SDF-1 antibodies (Abs) in mice receiving the dual drug therapy. (b) Representative images (n = 6) of wounds treated with anti-SDF-1 Abs or control IgG. Saline treatment was served as a control. (c) Wound closure rate. Data represent means ± SEM (n = 6). * p< 0.05. (d) and (e) Double immunofluorescence staining for SDF-1 (red) and F4/80 (green) or CD133 and CD31 in tissue sections from the wounds treated with control IgG or anti-SDF-1 antibodies in mice receiving the dual drug therapy at day 5 after injury. Inactivation of SDF-1 diminished CD133+ and CD31+ cell responses without affecting macrophage (F4/80+) accumulation in the wounds. (f) Local intradermal Injection of anti-SDF-1 antibodies eliminate the elevation of CD133 mRNA expression. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 3). * p < 0.05

Figure S6. CD133+ stem cells generate blood vessels in the wounded skin of CD133+/C-L mice in the dual treatment group. Concurrent GFP-fluorescence (upper panels), β-galactosidase (middle panels) and H&E staining (lower panels) of the same section of CD133+/C-L wounds on day 5 postinjury points to CD133+ progenitor cells as one of the sources of newly formed capillaries particularly in the dual treated CD133+/C-L mice. Boxed regions are shown at higher magnification to the right. Arrows point to the GFP+ (upper panel) lacZ+ (middle panel) capillaries (H&E, lower panels) in the same section. epi, epidermis; we, wound edge. Scale bar: 200 μm.