Abstract

Beginning January 2006, Medicare beneficiaries will have limited ability to change health plans. We examine the Medicare managed care enrollment and disenrollment behavior of traditionally vulnerable beneficiaries from 1999-2001 to estimate the potential impact of the new enrollment restrictions. Findings that several such groups were more likely to make multiple health plan elections, leave their managed care plan midyear, and/or have higher voluntary disenrollment rates and transfers to original fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare suggest that the lock-in provisions may have greater negative impacts on vulnerable beneficiaries. This article identifies several recommendations that CMS might consider to lessen the detrimental effects on at-risk groups.

Introduction

Along with major reforms to the Medicare Program included in the 2003 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (MMA) is a change that may go unnoticed by many until beneficiaries want to switch health plans and are not allowed to do so. Beginning in January 2006, open enrollment period (OEP) limitations (also known as enrollment lock-in provisions) will for the first time limit the number of times and the times of year that Medicare beneficiaries can change health plans. Currently, beneficiaries are allowed continuous monthly open enrollment into a health plan of their choice—either to or from a Medicare managed care plan such as a Medicare Advantage (MA) plan or to or from the original (FFS) Medicare plan. In 2006 and beyond, however, most beneficiaries will be able to make only one health plan change during an annual election period (AEP) in November-December of each year, with the election being effective the following January,1 and then make one additional health plan change during an OEP held during the first several months of the following calendar year (CY) (January-March 2007 and beyond). Nearly all MA plans must be open to new enrollment during an AEP, but not during an OEP. Except during the AEP at the end of a CY and the OEP during the first several months of the following CY, or under special circumstances,2 beneficiaries will not be allowed to change health plans, either to or from FFS Medicare or a Medicare managed care plan.

The lock-in policy was developed with the intention of improving continuity and quality of care, encouraging beneficiaries to be more accountable for their plan selection and use of health services, and to lend more stability to the MA market. Beneficiaries will ostensibly benefit because plans should have greater incentive to provide preventive care and coordinated care services to keep enrollees healthy, knowing that enrollees will remain in the plan for a minimum period. MA plans and the Federal Government may also benefit. For example, beneficiaries will be prevented from gaming the MA system by switching plans midyear once they have reached their plan's benefit cap. MA plans will be precluded from encouraging enrollees with an acute or chronic medical condition that requires expensive treatment to switch to FFS Medicare midyear, costing the Medicare Program more money than if the beneficiary had remained in the MA plan (Dallek, Biles, and Dennington, 2001).

Although the MMA lock-in provisions may have positive effects, they also may have some negative ones. Negative effects may include limiting midyear disenrollment of beneficiaries from health plans who want to follow their personal physician or who want to leave because of quality issues or confusion or disappointment with plan benefits. Of special concern are impacts on traditionally vulnerable subgroups of Medicare beneficiaries, who are already likely to be overwhelmed by the myriad of changes to the Medicare Program. In this study, we examined past health plan enrollment and disenrollment behavior of several beneficiary groups to assess whether the MMA lock-in provisions are likely to have a greater impact on at-risk beneficiaries than on others in terms of more often limiting their number or timing of health plan changes and voluntary disenrollments from Medicare managed care plans. The beneficiary groups consist of those disabled under age 65, Medicare/Medicaid dually eligibles, beneficiaries age 80 or over, and racial/ethnic minorities.3 These Medicare groups, which have in the past expressed greater dissatisfaction and problems with certain dimensions of managed care,4 might be particularly affected by reduced opportunities to change health plans.

To assess potential impacts, we analyzed differences between the selected beneficiary groups and the general Medicare managed care population for the 3-year period from 1999-2001 on several dimensions: voluntary group health organization (GHO)5 disenrollments and post-disenrollment choice of health plan, multiple health plan elections, and potentially prohibited health plan elections. This period was originally selected to establish a baseline of health plan patterns and trends from which lock-in provision impacts were to be measured in 2002. Although the provisions were delayed until 2006,6 these 3 years provide useful benchmarking data for examining the potential differential impacts in 2006 and beyond.

Voluntary GHO disenrollments are defined as disenrollments that are not due to death, loss of Medicare Parts A or B entitlement, a permanent beneficiary move outside of an MA's service area, or MA plan withdrawal from the county. Multiple switchers are beneficiaries who made more than one annual health plan election. A health plan election is defined as a change in health plans either to or from a GHO or to or from FFS Medicare. The term prohibited election describes a change in health plans-from or to a GHO or FFS Medicare—that would not have been allowed based on the number, timing, or circumstances of the election if the lock-in provisions had been in effect during the study years.

Although greater frequency of voluntary disenrollments from managed care plans by the beneficiary subgroups may result from plan premium and benefit competition, it is also a potential indicator that these beneficiaries are more concerned than others about access to care and physicians, quality of care, or administrative and care processes in their plan. For example, Lied et al. (2003), found that Medicare beneficiaries' ratings of their experiences with health plans were correlated with voluntary disenrollment rates, with overall plan rating being the strongest predictor. Multiple health plan switching might also indicate greater beneficiary confusion and dissatisfaction, creating discontinuity of care for both the beneficiary and health plans. Greater disenrollment to FFS Medicare than to another Medicare managed care plan among the subgroups is another potential indicator of similar managed care concerns. For example, previous studies have found that disenrollees to FFS Medicare tend to report access to care problems and are less satisfied with their Medicare risk plans than other managed care enrollees, and are less healthy than those who re-enroll in another managed care plan (Nelson, et al., 1996; Riley, Ingber, and Tudor, 1997; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999; and Physician Payment Review Commission, 1996). Although not all voluntary GHO disenrollments or other types of health plan elections will be prohibited under the lock-in rules, greater subgroup frequency for these indicators would suggest that lock-in rules may have a greater negative impact on them by restricting movement among plans or disenrollment from managed care plans for quality or other concerns.

Methods

To construct the files for this study, three CY files were extracted for 1999, 2000, and 2001 from CMS's Medicare Enrollment Database (EDB). Each file includes the entire Medicare health plan history for any individual enrolled in a GHO at any time during any of the three CYs. Each year's GHO spell file contains a separate record for each period (or spell) of health plan enrollment for an individual. For example, if a beneficiary was in FFS Medicare from January-March 1999, enrolled in an MA plan in April 1999, then returned to FFS Medicare in August 1999, the beneficiary would have three records or spells in the file. A beneficiary who was continuously enrolled in the same MA organization throughout the year would have only one spell in the file. A change from one health plan to another is only counted as a health plan election if the beneficiary was in the former plan for at least 60 days. This prevents counting extremely short enrollments as a health plan change when they are most likely the result of delays in recording new plan enrollments.7 For the beneficiary previously described, the decision to join an MA plan in April would be counted as the beneficiary's first election. The decision to return to FFS Medicare in August would be counted as a second election. Unless eligible for some type of Special Election Period (SEP), the first election would be allowed under the lock-in rules, but the second election would not. Beneficiaries continuously enrolled in FFS Medicare for an entire CY are not included in the files.

The annual GHO spell files contain a beneficiary's entire Medicare history to permit construction of variables that capture the individual's health plan experience during, as well as prior to, the study period. For example, we could determine whether the beneficiary enrolled in the same Medicare GHO more than once, or whether the beneficiary had previously enrolled in any Medicare GHO since becoming eligible for Medicare benefits. The files also identify GHO enrollees who had been in FFS Medicare for at least 3 years prior to 1999, but who had previously enrolled in a GHO at some point during their Medicare tenure. Three additional GHO Beneficiary CY files were created that summarize each year's GHO Spell file at the beneficiary level. For example, the 1999 GHO Beneficiary file contains a variable indicating whether the beneficiary made two or more health plan elections in that year.

The files also contain a limited number of beneficiary characteristics available from the EDB, consisting of age, sex, race/ethnicity, Medicaid eligibility,8 whether the beneficiary used hospice services during the CY, and whether the beneficiary had end stage renal disease (ESRD). Because hospice users accounted for only about 1.5 percent, and ESRD beneficiaries accounted for about 0.4 percent, of the GHO population in each of the three CY files, and because outcome differences by sex were small in all cases, these subgroups were not included in the detailed analyses.9 Table 1 provides frequency distributions for the beneficiary characteristics examined in the analyses.

Table 1. Frequency Distributions for Selected Beneficiary Characteristics for the 300,000 Group Health Organization (GHO) Enrollee Sample: Calendar Years 1999-2001.

| Characteristic | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Percent | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 85.2 | 84.9 | 84.3 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 8.8 | 9.0 | 8.9 |

| Hispanic, Any Race | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Asian, Non-Hispanic | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| North American Native, Non-Hispanic | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.2 |

| Age | |||

| 64 Years< | 9.0 | 8.5 | 8.2 |

| 65-69 Years | 26.8 | 26.0 | 24.4 |

| 70-74 Years | 24.3 | 24.5 | 24.5 |

| 75-79 Years | 19.3 | 19.4 | 19.9 |

| 80 Years+ | 20.7 | 21.6 | 23.0 |

| Medicaid Eligible | |||

| No | 93.8 | 93.8 | 93.9 |

| Yes | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.1 |

SOURCE: Laschober, M., Mathematica Policy Research: Calculations based on constructed GHO Beneficiary and Spell Level files.

We also created MA (contract) plan and market (county) characteristic files for 1999, 2000, and 2001 that were merged onto the GHO Spell and Beneficiary files. MA plan and market characteristic files were constructed using a number of CMS files, including Medicare+Choice (M+C) Non-Renewals and Service Area Reduction files, Medicare Managed Care Monthly Reports, M+C Market Penetration Reports, M+C Geographic Service Area files, M+C Plan Benefit Package files, Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set HEDIS® files, and internal CMS files documenting the history of M+C mergers and consolidations.10 In many places in this article, the term GHO is used, which represents any type of Medicare managed care organization. However, the Plan and Market Characteristic files were only constructed for MA organizations, excluding private FFS plans. Therefore, in some cases, the report refers specifically to MA plans.

Due to the large size of the GHO Spell and Beneficiary files (averaging 7 million beneficiaries and 8.5 million spells each year), we constructed six sample CY files for the purpose of analysis. To construct the sample files, we drew a random sample of 300,000 beneficiaries from each year's GHO Beneficiary file and then extracted each sample beneficiary's spells from the corresponding GHO Spell file. The majority of findings in this article are based on the random sample files.11

We identified the number, type, and timing of GHO disenrollments for each beneficiary, after accounting for GHO mergers, consolidations, and name changes. GHO disenrollments were categorized into voluntary and involuntary. Involuntary disenrollments are defined as a GHO disenrollment due to death, loss of Medicare Parts A or B entitlement, permanent beneficiary move outside of the MA's service area,12 or MA withdrawal from the county. Because there are beneficiaries who immediately disenroll on learning that their plan is withdrawing, (i.e., before the plan actually exits the market in January of the following year), we defined disenrollments that occurred after required plan withdrawal announcements—between August 1 and the end of the year for 1999 and 2000, and between October 1 and the end of the year for 2001—as involuntary. All GHO disenrollments not designated as involuntary were categorized as voluntary. In this study, voluntary disenrollment rates are defined as the percentage of CY GHO enrollment spells that ended in a disenrollment from a GHO, after excluding FFS Medicare spells and involuntary GHO disenrollments.

We first explored important bivariate relationships among outcomes of interest—voluntary disenrollments, post-disenrollment health plan choice, multiple health plan elections, and potentially prohibited elections—and selected beneficiary, MA plan, and market characteristics. Comparisons of bivariate statistics were nearly always statistically significant at the 95 percent or higher level of confidence due to the large sample sizes.

Relationships were next analyzed through multivariate logistic regressions. For each year of data, selected beneficiary, MA plan, and market descriptors were regressed on the following dichotomous dependent variables: (1) whether or not a beneficiary voluntarily disenrolled from a GHO (n=approximately 100,000 spells annually); (2) whether a voluntary disenrollee transferred to FFS Medicare or re-enrolled in another or the same GHO within 60 days (n=approximately 15,000 spells annually); (3) whether or not a beneficiary made two or more health plan elections in a CY (n=300,000 beneficiaries annually); and (4) whether or not a beneficiary's election would have been prohibited if the lock-in rules had been in effect (n=approximately 35,000 elections annually). Coefficients and statistical significance were generally consistent in magnitude and direction across the 3 years for all equations. Therefore, we only discuss relatively large differences among years that occur.

Findings

GHO Disenrollment Patterns and Trends

It is important to note that GHO experiences between 1999 and 2001 are observed in an environment characterized by large MA plan withdrawals, declining plan enrollment, and significant changes to benefit packages that shifted more costs to enrollees in remaining MA plans (Achman and Gold, 2002). In such an unstable environment for managed care enrollees, greater voluntary disenrollments and transfers to FFS Medicare due to declining availability of managed care options and waning confidence in plan stability might be expected. This study, however, focuses on differences in behavior between the general Medicare GHO population and the vulnerable beneficiary subgroups during this period of MA market contraction.

First, we compared characteristics of beneficiaries who voluntarily disenrolled from a GHO with beneficiaries who remained in their GHO for the entire year. Table 2 shows that the voluntary disenrollment rate for the general GHO population rose substantially over the 3-year period, increasing from 13 percent of all GHO spells in 1999 to 18 percent in 2001. Compared with others, voluntary disenrollment rates were consistently higher-although often only slightly higher—for the selected beneficiary subgroups except for those age 80 or over.

Table 2. Voluntary GHO Disenrollment and Post-Disenrollment Plan Choice, by Race/Ethnicity, Age, and Medicaid Eligibility for the GHO Enrollee Sample: Calendar Years 1999-2001.

| Characteristic | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Voluntary Disenrollment Rate | Post-Disenrollment Plan Choice | Voluntary Disenrollment Rate | Post-Disenrollment Plan Choice | Voluntary Disenrollment Rate | Post-Disenrollment Plan Choice | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| FFS | GHO | FFS | GHO | FFS | GHO | ||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Percent | Percent | Percent | |||||||

| Total GHO Enrollee Sample | 13.4 | 31.6 | 68.4 | 15.2 | 41.6 | 58.4 | 18.1 | 51.4 | 48.6 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 13.3 | 31.0 | 69.0 | 14.9 | 40.9 | 59.2 | 17.8 | 51.8 | 48.2 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 15.2 | 36.3 | 63.7 | 18.8 | 47.4 | 52.7 | 20.5 | 53.0 | 47.0 |

| Hispanic, Any Race | 15.7 | 27.8 | 72.2 | 19.3 | 39.3 | 60.7 | 24.1 | 37.0 | 63.1 |

| Age Category | |||||||||

| 64 Years< | 14.1 | 37.7 | 62.3 | 16.8 | 49.2 | 50.9 | 19.7 | 55.7 | 44.3 |

| 65-69 Years | 13.3 | 31.4 | 68.6 | 15.4 | 40.9 | 59.1 | 19.4 | 53.3 | 46.7 |

| 70-74 Years | 13.2 | 29.1 | 70.9 | 15.3 | 40.1 | 59.9 | 18.5 | 49.8 | 50.2 |

| 75-79 Years | 13.3 | 29.5 | 70.5 | 14.7 | 38.8 | 61.2 | 17.4 | 48.6 | 51.4 |

| 80 Years+ | 13.6 | 33.9 | 66.1 | 14.9 | 43.2 | 56.8 | 16.3 | 51.6 | 48.4 |

| Medicaid Eligible | |||||||||

| Yes | 19.8 | 46.4 | 53.6 | 23.0 | 59.4 | 40.6 | 27.9 | 64.8 | 35.2 |

| No | 13.0 | 30.0 | 70.0 | 14.7 | 39.6 | 60.4 | 17.5 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

NOTES: GHO is Group Health Organization. FFS is fee-for-service.

SOURCE: Laschober, M., Mathematica Policy Research: Calculations based on constructed GHO Beneficiary and Spell Level files.

Similar to findings by Riley, Ingber, and Tudor (1997) based on a 1994-1995 sample of Medicare managed care (health maintenance organization [HMO]) disenrollees, we found small differences in voluntary disenrollment rates by race/ethnicity in the bivariate comparisons. Voluntary disenrollment rates for Black and Hispanic beneficiaries were 2 to 5 percentage points greater than for White beneficiaries across the study years (Table 2), but were either statistically insignificant at the 95 percent level of confidence in the multivariate analysis or had odds ratios close to 1 (Table 3). Riley and colleagues found an approximately 1.5 percentage higher voluntary disenrollment rate for disabled beneficiaries under age 65 compared with beneficiaries age 80 or over, but we did not detect statistically significant differences by age (Tables 2 and 3). Medicaid-eligibility status had the strongest and most consistent association with voluntary disenrollment rates, in both the bivariate and multivariate analyses. Our results are similar to Riley and colleagues, with Medicaid eligibles in our study having higher voluntary disenrollment rates than non-Medicaid eligibles of approximately 7 to 9 percentage point differences (Table 2). Additionally, the divergence widened over the 3 years.13 All of these results were confirmed in the multivariate analyses, which accounted for differences in MA plan availability among the subgroups (Table 3).

Table 3. Logistic Regression Results for Voluntary Disenrollment Rates: Calendar Years (CYs) 1999-2001.

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1999 N=111,775 Pseudo R2 = 0.10 |

2000 N=66,0192 Pseudo R2 = 0.13 |

2001 N=131,679 Pseudo R2 = 0.11 |

||||

|

| ||||||

| Odds Ratio | P-Value | Odds Ratio | P-Value | Odds Ratio | P-Value | |

| Beneficiary Choice Descriptor | ||||||

| Plan Origination: Fee-for-Service3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Plan Origination: GHO | 0.865 | 0.000 | 0.965 | 0.244 | 0.929 | 0.000 |

| Plan Origination: NewlyEligible for Medicare Part B in Current CY | 0.758 | 0.000 | 0.666 | 0.000 | 0.838 | 0.001 |

| Plan Origination: Newly Eligible for Medicare Part B in Previous CY | 0.878 | 0.000 | 0.844 | 0.000 | 0.907 | 0.000 |

| Number of Days Enrolled in GHO Prior to Disenrollment (Ranked from 1-5)4 | 0.678 | 0.000 | 0.819 | 0.000 | 0.681 | 0.000 |

| Previously Enrolled in Same GHO | 1.212 | 0.000 | 1.280 | 0.000 | 1.085 | 0.001 |

| First-Ever GHO Enrollment | 0.504 | 0.000 | 0.676 | 0.000 | 0.415 | 0.000 |

| Beneficiary Characteristic | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 0.987 | 0.675 | 1.113 | 0.007 | 0.995 | 0.854 |

| Hispanic, Any Race | 1.034 | 0.069 | 1.052 | 0.021 | 1.101 | 0.000 |

| 64 Years<3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 65-69 Years | 1.117 | 0.002 | 0.964 | 0.450 | 1.125 | 0.000 |

| 70-74 Years | 1.090 | 0.021 | 0.914 | 0.069 | 1.087 | 0.005 |

| 75-79 Years | 1.096 | 0.019 | 0.908 | 0.062 | 1.034 | 0.280 |

| 80 Years+ | 1.091 | 0.027 | 0.978 | 0.669 | 0.970 | 0.337 |

| Eligible for Medicaid | 1.472 | 0.000 | 1.922 | 0.000 | 1.709 | 0.000 |

| Eligible for Hospice Benefits | 3.739 | 0.000 | 2.807 | 0.000 | 2.355 | 0.000 |

| Female | 0.966 | 0.062 | 0.994 | 0.007 | 0.930 | 0.000 |

| MA (Plan) Descriptor | ||||||

| For-Profit Plan | 1.458 | 0.000 | 1.396 | 0.000 | 1.809 | 0.000 |

| MA Plan's Enrollment (Continuous Variable) | 1.000 | 0.008 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| MA Plan's Experience in County (Ranked from 1-4)5 | 1.011 | 0.367 | 1.421 | 0.000 | 1.332 | 0.000 |

| MA Plan's County Penetration Rate (Continuous Variable)6 | 0.924 | 0.000 | 0.936 | 0.000 | 0.973 | 0.000 |

| Market (County) Descriptor | ||||||

| MA Plan Availability in County (Number of MA Contracts Operating in County) | 0.976 | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.796 | 1.037 | 0.000 |

| Aggregate MA Plan County Penetration Rate (Continuous Variable)6 | 1.017 | 0.000 | 1.003 | 0.133 | 0.992 | 0.000 |

| County Had at Least 1 End-of-Year MA Withdrawal or Service Area Reduction | 0.981 | 0.363 | 0.801 | 0.000 | 1.026 | 0.128 |

Group Health Organization (GHO) enrollment spell ended in a voluntary disenrollment.

The observations included in the regression equation for 2000 are much fewer than in 1999 and 2001 due to a much greater number of missing values for the variable Aggregate Medicare Advantage (MA) Plan County Penetration Rate in 2000. Observations with a missing value for any of the regression variables were eliminated from the estimations.

Comparison group.

1=less than 90 days; 2=90 to less than 180 days; 3=180 to less than 365 days; 4=1 year to less than 5 years; 5=5 years or longer.

Length of time MA contract had been operating in the county as of December 31 of the CY: 1 = less than 1 year; 2 = 1 to less than 5 years; 3 = 5 to less than 9 years; 4 = 9 or more years.

An individual MA Plan's County Penetration Rate = The number of MA enrollees in the MA plan's contract and county divided by the total number of Medicare beneficiaries residing in the county; Aggregate MA Plan County Penetration Rate = The total number of MA enrollees in the county in all MA plans divided by the total number of Medicare beneficiaries residing in the county.

SOURCE: Laschober, M., Mathematica Policy Research: Calculations based on constructed GHO Beneficiary and Spell Level files.

We also examined rapid voluntary disenrollment rates (i.e., the beneficiary voluntarily left his/her GHO within 90 days of enrollment). Rapid plan disenrollment might be an additional indicator of health plan quality or access concerns or misunderstanding of GHO benefits, structure, or requirements for receiving care. In 1999, 9.2 percent of all voluntary disenrollments for the general GHO enrollee population were rapid disenrollments, falling to 5.2 percent in 2000 and 6.1 percent in 2001. The traditionally vulnerable beneficiary subgroups were all slightly more likely than the general GHO population to be rapid disenrollees (3 to 5 percentage points difference), even after adjusting for MA plan availability.

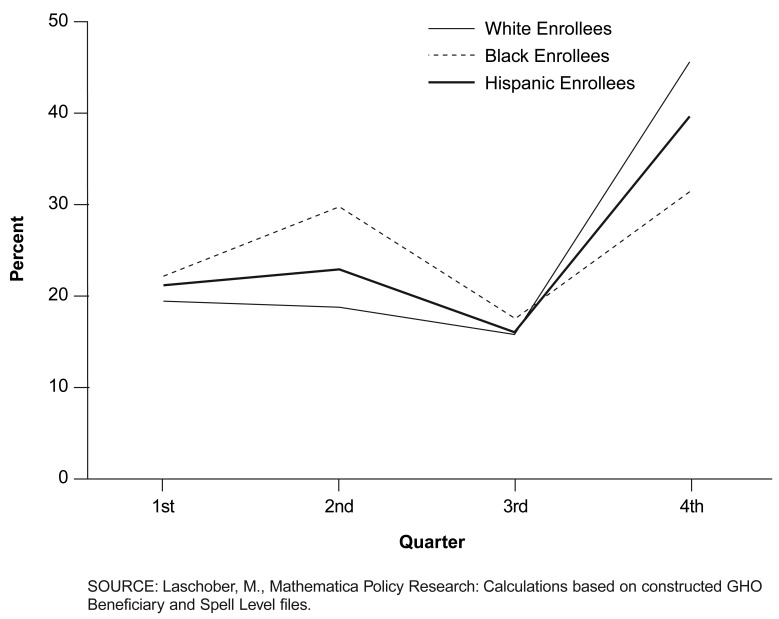

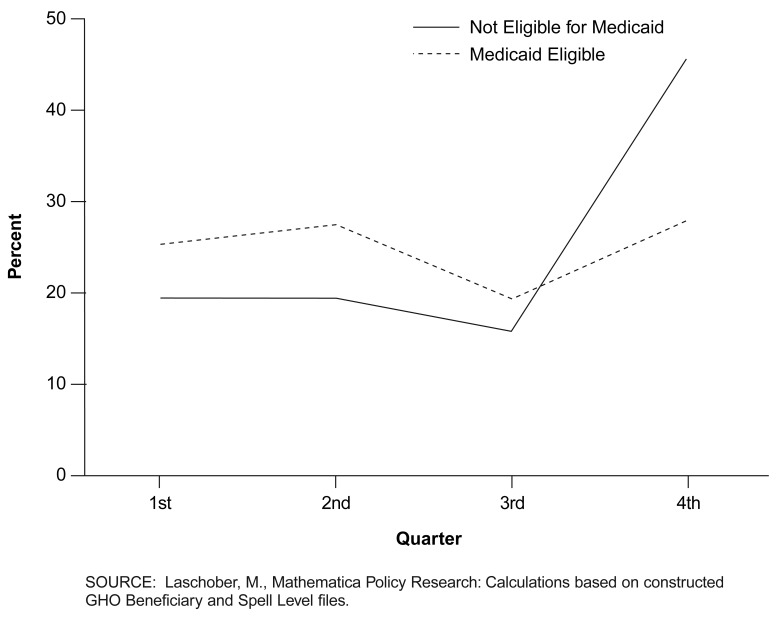

In addition to annual disenrollment rates, we examined voluntary disenrollments by quarter. A recent study of MA plan disenrollment reasons found that voluntary MA disenrollees more often cited leaving their plan due to problems with consistently seeing their desired providers or problems with getting care midyear than at the beginning or end of the year (Laschober, 2004). In contrast, disenrollments due to problems with obtaining accurate plan information or with prescription drugs were reported fairly consistently throughout the year, and disenrollments related to issues with plan premiums, copayments, or benefit structure were most often cited at the beginning and end of the year (Laschober, 2004).

Timing of voluntary disenrollments by quarter varied for several of the beneficiary subgroups. Figure 1 shows that non-White beneficiaries were much less likely than White beneficiaries to disenroll in the fourth quarter and more likely to disenroll midyear. Differences were most evident for Black GHO enrollees, who more often than others disenrolled in the second quarter of the year (2001 data are shown in Figure 1, but the patterns are the same for 1999 and 2000). There was only minor variation in GHO voluntary disenrollment patterns among beneficiary age groups by quarter except that disabled beneficiaries under age 65 were somewhat more likely to voluntarily leave their GHO outside of the fourth quarter. Medicaid eligibles were also much more likely than non-dually eligibles to disenroll from their GHO in the first to third quarters of the year and less likely to voluntary disenroll in the fourth quarter (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Voluntary Disenrollments by Quarter as a Percent of Annual Voluntary Disenrollments, by Race/Ethnicity for the Group Health Organization (GHO) Enrollee Sample: Calendar Year 2001.

Figure 2. Voluntary Disenrollments by Quarter as a Percent of Annual Disenrollments, by Medicaid Eligibility, for the Group Health Organization (GHO) Enrollee Sample: Calendar Year 2001.

Like voluntary disenrollments, transfers to FFS Medicare rose from 1999 to 2001 for the general GHO population (Table 2). Approximately 32 percent of voluntary GHO disenrollees switched to FFS Medicare in 1999, rising substantially to 51 percent in 2001. All of the beneficiary subgroups followed the same trend by more frequently disenrolling to FFS Medicare over the 3 years with one exception. Hispanic beneficiaries were consistently more likely than others to re-enroll in another GHO. Black disenrollees were slightly more likely than the general GHO population in all 3 years to disenroll to FFS Medicare (2 to 6 percentage points higher), as were disabled beneficiaries under age 65 (4 to 8 percentage points higher) and Medicaid eligible beneficiaries (13 to 18 percentage points higher) (Table 2).

The multivariate analysis, however, only supported the findings for the Medicaid-eligible enrollee population (Table 4). It may be that the often-poorer health of Medicaid enrollees is associated with these differences, that Medicaid eligibles may already have additional benefits through Medicaid that MA plans might offer (e.g., prescription drug coverage) that render managed care benefits less advantageous to this group, or that Medicaid eligibles face more complex managed care arrangements and barriers to managed care enrollment than others.14 Riley et al. (1997) found that disenrollment to FFS Medicare was higher for Black disenrollees, disabled under age 65, disenrollees age 85 or over, and for Medicaid eligibles.

Table 4. Logistic Regression Results for Post-Disenrollment Health Plan Destination: Calendar Years (CYs) 1999-2001.

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1999 N=15,115 Pseudo R2 = 0.10 |

2000 N=8,7002 Pseudo R2 = 0.13 |

2001 N=25,251 Pseudo R2 = 0.11 |

||||

|

| ||||||

| Odds Ratio | P-Value | Odds Ratio | P-Value | Odds Ratio | P-Value | |

| Beneficiary Choice Descriptor | ||||||

| Plan Origination: FFS3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Plan Origination: GHO | 0.512 | 0.000 | 0.501 | 0.000 | 0.613 | 0.000 |

| Plan Origination: Newly Eligible for Medicare Part B in Current CY | 0.396 | 0.000 | 0.428 | 0.000 | 0.521 | 0.000 |

| Plan Origination: Newly Eligible for Medicare Part B in Previous CY | 0.539 | 0.000 | 0.641 | 0.000 | 0.689 | 0.000 |

| Number of Days Enrolled in GHO Prior to Disenrollment (Ranked from 1-5)4 | 0.859 | 0.000 | 0.948 | 0.091 | 0.943 | 0.002 |

| Previously Enrolled in Same GHO | 0.794 | 0.009 | 0.893 | 0.237 | 1.147 | 0.004 |

| First-Ever GHO Enrollment | 2.305 | 0.000 | 2.004 | 0.000 | 1.618 | 0.000 |

| Beneficiary Characteristic | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1.054 | 0.418 | 1.274 | 0.002 | 0.960 | 0.413 |

| Hispanic, Any Race | 1.025 | 0.554 | 1.152 | 0.020 | 0.978 | 0.433 |

| 64 Years<3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 65-69 Years | 0.951 | 0.494 | 0.853 | 0.890 | 1.199 | 0.001 |

| 70-74 Years | 0.913 | 0.228 | 0.910 | 0.317 | 1.085 | 0.155 |

| 75-79 Years | 0.896 | 0.164 | 0.837 | 0.070 | 0.968 | 0.588 |

| 80 Years+ | 1.286 | 0.001 | 1.064 | 0.531 | 1.166 | 0.011 |

| Eligible for Medicaid | 2.143 | 0.000 | 2.856 | 0.000 | 2.413 | 0.000 |

| Eligible for Hospice Benefits | 1.453 | 0.760 | 1.430 | 0.230 | 2.148 | 0.000 |

| Female | 0.997 | 0.943 | 0.880 | 0.100 | 0.850 | 0.000 |

| MA (Plan) Descriptor | ||||||

| For-Profit Plan | 0.665 | 0.000 | 0.855 | 0.006 | 0.877 | 0.000 |

| MA Plan's Enrollment (Continuous Variable) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| MA Plan's Experience in County (Ranked from 1-4)5 | 0.927 | 0.002 | 0.749 | 0.000 | 0.910 | 0.000 |

| MA Plan's County Penetration Rate (Continuous Variable)6 | 1.071 | 0.000 | 1.049 | 0.000 | 1.035 | 0.000 |

| MA Withdrew from County at End of Year | 0.831 | 0.032 | 1.106 | 0.223 | 0.805 | 0.000 |

| Market (County) Descriptor | ||||||

| MA Plan Availability in County (Number of MA Contracts Operating in County) | 0.952 | 0.000 | 0.974 | 0.108 | 0.846 | 0.000 |

| Aggregate MA Plan County Penetration Rate (Continuous Variable)6 | 0.951 | 0.000 | 0.923 | 0.000 | 0.949 | 0.000 |

| County Had at Least 1 End-of-Year MA Withdrawal or Service Area Reduction | 1.120 | 0.016 | 1.796 | 0.000 | 1.987 | 0.000 |

Voluntary Group Health Organization (GHO) disenrollee transferred to original fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare.

The observations included in the regression equation for 2000 are much fewer than in 1999 and 2001 due to a much greater number of missing values for the variable Aggregate MA Plan County Penetration Rate in 2000. Observations with a missing value for any of the regression variables were eliminated from the estimations.

Comparison group.

1=less than 90 days; 2=90 to less than 180 days; 3=180 to less than 365 days; 4=1 year to less than 5 years; 5=5 years or longer.

Length of time MA contract had been operating in the county as of December 31 of the CY: 1 = less than 1 year; 2 = 1 to less than 5 years; 3 = 5 to less than 9 years; 4 = 9 or more years.

An individual MA Plan's County Penetration Rate = the number of MA enrollees in the MA plan's contract and county divided by the total number of Medicare beneficiaries residing in the county; Aggregate MA Plan County Penetration Rate = the total number of MA enrollees in the county in all MA plans divided by the total number of Medicare beneficiaries residing in the county.

NOTE: MA is Medicare Advantage.

SOURCE: Laschober, M., Mathematica Policy Research: Calculations based on constructed GHO Beneficiary and Spell Level files.

Multiple Elections

We next investigated characteristics of beneficiaries who changed plans relatively frequently. Multiple switchers are defined as beneficiaries who made more than one annual health plan election. While not all of the multiple elections will be prohibited under the MMA lock-in rules, multiple health plan switching can be a sign of beneficiary confusion, dissatisfaction, or attempts to game the system, such as switching managed care plans to obtain additional prescription drug benefits when the beneficiary reaches the first plan's drug coverage limit.

Although the number of all Medicare GHO enrollees characterized as multiple switchers was very low and declined from 2.0 percent in 1999 to 1.7 percent of GHO enrollees in 2001, several traditionally vulnerable groups of beneficiaries increasingly accounted for those who made more than one election in a CY. Black GHO enrollees, in particular, were more likely to be multiple switchers than White GHO enrollees (Table 5). Black beneficiaries increased their proportion in the multiple switcher population relative to other racial/ethnic groups over the 3 years and declined only slightly in absolute terms based on the 300,000 sample. At the same time, White GHO enrollees accounted for a declining percentage and number of multiple switchers. Hispanic beneficiaries were only slightly overrepresented in the multiple switcher population, with the number remaining nearly constant over the 3 years.

Table 5. Multiple Health Plan Switcher Distribution, by Race/Ethnicity, Age, and Medicaid Eligibility for the Group Health Organization (GHO) Enrollee Sample: Calendar Years 1999-2001.

| Beneficiary Characteristic | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Non-Multiple Switchers | Multiple Switchers | Non-Multiple Switchers | Multiple Switchers | Non-Multiple Switchers | Multiple Switchers | |

| Total GHO Enrollee Sample | 294,091 | 5,909 | 295,107 | 4,893 | 295,287 | 4,713 |

| Percent | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 85.3 | 78.2 | 85.1 | 75.2 | 84.5 | 72.8 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 8.7 | 15.0 | 8.9 | 16.8 | 8.7 | 17.5 |

| Hispanic, Any Race | 2.5 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 5.3 | 2.6 | 5.2 |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 3.3 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 3.9 | 4.2 |

| Age Category | ||||||

| 64 Years< | 8.9 | 14.0 | 8.4 | 14.1 | 8.1 | 13.5 |

| 65-69 Years | 26.8 | 25.8 | 26.0 | 25.7 | 24.4 | 25.4 |

| 70-74 Years | 24.3 | 22.1 | 24.5 | 22.8 | 24.6 | 23.1 |

| 75-79 Years | 19.3 | 17.6 | 19.5 | 17.3 | 19.9 | 18.1 |

| 80 Years+ | 20.7 | 20.5 | 21.6 | 20.1 | 23.0 | 19.9 |

| Medicaid Eligible | ||||||

| No | 94 | 86.3 | 94 | 85.5 | 94 | 84.9 |

| Yes | 6 | 13.7 | 6 | 14.5 | 6 | 15.1 |

SOURCE: Laschober, M., Mathematica Policy Research: Calculations based on constructed GHO Beneficiary and Spell Level files.

Two other beneficiary groups were also overrepresented by multiple elections. The proportion of multiple switchers who were disabled beneficiaries under age 65 increased in relative terms to other age groups, but declined in absolute numbers. The proportion of multiple switchers who were eligible for Medicaid coverage also increased in relative terms to non-Medicaid beneficiaries and declined only slightly in absolute numbers (Table 5).15 Logistic multivariate regressions for each of the 3 years support the bivariate findings (Table 6). The findings are based on holding constant differential availability of MA plans, differences in county characteristics, and differences across MA plan characteristics from which the beneficiaries disenrolled.

Table 6. Logistic Regression Results for Multiple Switchers: Calendar Years 1999-2001.

| Dependent Variable1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1999 N=299,714 Pseudo R2 |

2000 N=299,732 Pseudo R2 = 0.05 |

2001 N=278,281 Pseudo R2 = 0.005 |

||||

|

| ||||||

| Independent Variable | Odds Ratio | P-Value | Odds Ratio | P-Value | Odds Ratio | P-Value |

| Beneficiary Choice Descriptor | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic2 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1.559 | 0.000 | 1.707 | 0.000 | 1.846 | 0.000 |

| Hispanic, Any Race | 1.622 | 0.000 | 1.840 | 0.000 | 1.765 | 0.000 |

| 64 Years< | 1.228 | 0.000 | 1.354 | 0.000 | 1.237 | 0.000 |

| 65-69 Years | 1.008 | 0.817 | 1.041 | 0.290 | 1.047 | 0.234 |

| 70-79 Years2 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 80 Years+ | 1.093 | 0.014 | 1.032 | 0.427 | 0.922 | 0.047 |

| Eligible for Medicaid | 1.936 | 0.000 | 1.997 | 0.000 | 2.074 | 0.000 |

| Female | 1.089 | 0.002 | 1.026 | 0.388 | 1.070 | 0.026 |

| First-Ever GHO Enrollment | 6.133 | 0.000 | 5.532 | 0.000 | 5.634 | 0.000 |

| First GHO Enrollment in 3 Years | 2.116 | 0.000 | 1.522 | 0.000 | 1.811 | 0.000 |

| Snowbird3 | 25.033 | 0.000 | 26.772 | 0.000 | 23.725 | 0.000 |

| Newly Eligible for Medicare Part B in CY | 0.259 | 0.00 | 0.257 | 0.00 | 0.320 | 0.000 |

| Market (County) Descriptors | ||||||

| MA Plan Availability in County (Ranked from 0-3)4 | 0.988 | 0.554 | 1.151 | 0.000 | 1.231 | 0.000 |

| County Had at Least 1 End-of-Year MA Withdrawal or Service Area Reduction | 1.780 | 0.000 | 1.528 | 0.000 | 0.956 | 0.162 |

Medicare beneficiary changed health plans (GHO or FFS) two or more times in a calendar year.

Comparison group.

A premanent move is distinguished in the study from the repetitive moves to and from the same market area over the 3 years of the study that might occur by so-called snowbirds.

Number of MA contracts operating in county during the CY, excluding private-fee-for-service plans: 0 = 0; 1 = 1; 2 = 2 to 4; 3 = 5 or more.

NOTES: GHO is Group Health Organization. FFS is fee-for-service. MA is Medicare Advantage.

SOURCE: Laschober, M., Mathematica Policy Research: Calculations based on constructed GHO Beneficiary and Spell Level files.

Potentially Prohibited Elections

Higher voluntary disenrollment rates, midyear disenrollments, and greater health plan switching among traditionally vulnerable beneficiaries suggest that the lock-in rules are likely to have a greater impact on these subgroups if their behavior in 2006 and beyond is comparable to the 1999-2001 period. We assessed the potential direct impacts of enrollment lock-in from two perspectives. We first analyzed the proportion of health plan elections as a percentage of total elections for each beneficiary subgroup that would have been prohibited in 1999, 2000, or 2001 had the MMA lock-in provisions been in effect. Second, we examined the proportion of health plan elections as a percentage of each subgroup's total spells that would have been prohibited under the lock-in rules. The term prohibited election describes a change in health plans—from or to a GHO or FFS Medicare-that would not have been allowed under the lock-in provisions based on the number, timing, or circumstances of the election. We assumed that the OEP would have consisted of the first 3 months of the year, as the MMA legislation stipulates beginning in 2007.

Until mid-2002, CMS data did not record the plan benefit package (plan identification) within a managed care contract. Thus we could not track beneficiary changes from one MA contract's benefit package to another within the same MA contract. This type of beneficiary election would be restricted under the lock-in rules to the same extent as other types of health plan changes. Our estimates underrepresent potentially prohibited health plan elections due to this limitation. Conversely, because the data do not allow for identification of all changes in health plans that would have been allowed under an SEP (e.g., institutionalized beneficiaries or beneficiaries enrolled in an MA plan through employer-sponsored insurance with a different open election period), our estimates under represent potentially prohibited elections. The impact of the competing data shortfalls on the overall estimates is unkown.

During the 3 study years, an estimated 11 percent of health plan spells (i.e., enrollment periods) would have been prohibited among the general GHO population, affecting about 12 percent of all GHO enrollees. Of total health plan elections, over 6 in 10 would not have been allowed. Therefore, although the estimated proportion of beneficiaries affected by the lock-in rules would have been relatively small, the lock-in rules would have affected a large percentage of these beneficiaries' health plan decisions.

Approximately 99 percent of prohibited health plan elections would have occurred during the last three quarters of the CY, mostly due to beneficiaries changing health plans outside of the AEP and OEP. Very few elections in each year would have been disallowed in the first quarter, accounting for less than 1 percent of prohibited elections. These findings indicate that timing of health plan changes—rather than the number of changes—is the primary reason that beneficiaries would not have been able to make a desired switch in plans if the lock-in provisions had been in effect.

The beneficiary characteristics we examined were mostly unrelated to prohibited elections when measured as a percentage of total elections (Table 7). An exception is that, of those who changed health plans at least once in a year, a smaller percentage of disabled beneficiaries under age 65 and beneficiaries ages 65-74 would have made a prohibited election compared with beneficiaries age 75 or over. This is primarily because the age 74 or under beneficiary groups included a greater number of newly eligible Part B beneficiaries who would have been allowed additional health plan elections under an SEP.

Table 7. Potentially Prohibited Health Plan Elections, by Race/Ethnicity, Age, and Medicaid Eligibility for the Group Health Organization (GHO) Enrollee Sample: Calendar Years 1999-2001.

| Characteristic | Potentially Prohibited Elections as a Percent of Total Health Plan Elections | Potentially Prohibited Elections as a Percent of Total Health Plan Spells | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | |

| Total GHO Enrollee Sample | 36,190 (59.0) |

33,289 (58.0) |

35,322 (61.0) |

36,190 (10.0) |

33,289 (9.3) |

35,322 (9.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 58.4 | 57.1 | 59.9 | 9.7 | 8.9 | 9.3 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 58.0 | 58.2 | 63.1 | 12.8 | 12.7 | 13.7 |

| Hispanic, Any Race | 61.5 | 61.5 | 65.2 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 14.4 |

| Age Category | ||||||

| 64 Years< | 48.1 | 46.8 | 50.2 | 11.3 | 10.7 | 11.4 |

| 65-69 Years | 50.4 | 50.4 | 53.8 | 9.3 | 8.9 | 9.8 |

| 70-74 Years | 64.9 | 63.1 | 66.2 | 10.1 | 9.5 | 10.2 |

| 75-79 Years | 65.2 | 63.3 | 66.2 | 10.0 | 9.2 | 9.7 |

| 80 Years+ | 64.1 | 61.9 | 64.1 | 10.2 | 9.1 | 9.2 |

| Medicaid Eligible | ||||||

| No | 58.1 | 57.0 | 60.2 | 9.6 | 8.9 | 9.4 |

| Yes | 60.7 | 58.4 | 61.7 | 15.7 | 14.9 | 16.9 |

SOURCE: Laschober, M., Mathematica Policy Research: Calculations based on constructed GHO Beneficiary and Spell Level files.

No notable differences were found in the proportion of prohibited elections out of total health plan elections (for all four quarters) among other age groups or by race/ethnicity or Medicaid status. The bivariate findings are supported in the multivariate logistic regressions: the odds ratio of having a prohibited election for most beneficiary subgroups was not statistically significant at the 95 percent confidence level, and the odds ratio for newly eligible beneficiaries compared with continuing beneficiaries was statistically significant and close to zero (Table 8). The multivariate results were stable across the 3 years.

Table 8. Logistic Regression Results for Potentially Prohibited Health Plan Elections: CY 1999-20011.

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable: A Health Plan Change (GHO or FFS) Would Have Been Prohibited under MA Lock-In Provisions1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1999 N=42,331 Pseudo R2 = 0.19 |

2000 N=35,738 Pseudo R2 = 0.19 |

2001 N=30,525 Pseudo R2 = 0.19 |

||||

|

| ||||||

| Odds Ratio | P-Value | Odds Ratio | P-Value | Odds Ratio P-Value | ||

| Beneficiary Characteristic | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic2 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 0.985 | 0.664 | 1.028 | 0.396 | 0.885 | 0.000 |

| Hispanic, Any Race | 0.887 | 0.044 | 1.041 | 0.713 | 0.976 | 0.828 |

| 64 Years< | 1.004 | 0.919 | 0.994 | 0.879 | 0.859 | 0.001 |

| 65-69 Years | 1.013 | 0.652 | 1.017 | 0.565 | 0.959 | 0.200 |

| 70-792 Years | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 80 Years+ | 0.961 | 0.192 | 0.977 | 0.474 | 0.925 | 0.028 |

| Eligible for Medicaid | 1.014 | 0.727 | 1.021 | 0.633 | 1.013 | 0.790 |

| Female | 0.970 | 0.184 | 1.032 | 0.205 | 0.963 | 0.160 |

| First-Ever GHO Enrollment | 0.853 | 0.000 | 0.818 | 0.000 | 1.122 | 0.001 |

| First GHO Enrollment in 3 Years | 0.989 | 0.903 | 1.089 | 0.460 | 1.168 | 0.233 |

| Newly Eligible for Medicare Part B in CY | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| MA (Plan) Descriptors | ||||||

| For-Profit Plan | 0.948 | 0.034 | 1.157 | 0.000 | 1.279 | 0.000 |

| MA Plan Withdrew from County at End of Year | 0.281 | 0.000 | 0.307 | 0.000 | 0.484 | 0.000 |

| MA Plan's Experience in County (Ranked from 1-4)3 | 0.951 | 0.000 | 0.821 | 0.000 | 0.913 | 0.000 |

| Market (County) Descriptors | ||||||

| MA Plan Availability in County (ranked from 0-3)4 | 1.003 | 0.895 | 0.914 | 0.000 | 0.966 | 0.141 |

| County had at Least 1 End-of-Year MA Withdrawal or Service Area Reduction | 1.236 | 0.000 | 1.622 | 0.000 | 0.883 | 0.000 |

A health plan change (GHO or FFS) would have been prohibited under MMA lock-in provisions.

Comparison group.

Length of time MA contract had been operating in the county as of December 31 of the calendar year: 1 = less than 1 year; 2 = 1 to less than 5 years; 3 = 5 to less than 9 years; 4 = 9 or more years.

Number of MA contracts operating in county during the CY, excluding private-fee-for-service plans: 0 = 0; 1 = 1; 2 = 2 to 4; 3 = 5 or more.

NOTES: GHO is Group Health Organization. FFS is fee-for-service. MA is Medicare Advantage. MMA is Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act.

SOURCE: Laschober, M., Mathematica Policy Research: Calculations based on constructed GHO Beneficiary and Spell Level files.

In contrast to findings based on percentage of health plan elections, findings based on percentage of health plan spells indicate that the vulnerable subgroups would have been more impacted by the MMA lock-in provisions than others. This is because they made a greater number of health plan elections per beneficiary (Table 7). Medicaid eligibles in particular made a greater number of health plan changes per beneficiary compared with those ineligible for Medicaid. Although the younger age groups (disabled under age 65 and 65-74) also switched health plans more often than the older age groups (75 or over), more of these elections would have been allowed under an SEP. Black and Hispanic beneficiaries also made slightly more health plan elections than White beneficiaries and a slightly greater share of these would have been prohibited under the lock-in rules.

Summary and Discussion

Although 1999 to 2001 was a relatively unstable period for the Medicare managed care program, the comparative enrollment and disenrollment behavior of beneficiary subgroups within the Medicare managed care population provides important indications of the potential differential impacts of the new 2003 MMA lock-in provisions on traditionally vulnerable beneficiaries. We found that voluntary GHO disenrollment rates were only modestly higher for Blacks, Hispanics, and under age 65 disabled beneficiaries compared with their counterparts, and were little different for the most elderly beneficiary group (age 80 or over). Medicaid eligible individuals, however, had voluntary disenrollment rates 7 to 9 percentage points higher than non-dually eligibles, which also increased over the period.

The traditionally vulnerable beneficiary subgroups we examined were all slightly more likely than the general GHO population to be rapid disenrollees (3 to 5 percentage points difference). Timing of voluntary disenrollments also differed, and differed markedly by race/ethnicity and Medicaid eligibility. Black, Hispanic, and Medicaid eligible beneficiaries were more likely than their counterparts to voluntarily leave their GHO plans midyear. Additionally, Medicaid eligibles were substantially more likely than others to switch to FFS Medicare after a GHO disenrollment.

Although prohibited health plan elections as a proportion of total health plan elections for each subgroup averaged about the same as for the general GHO population at 60 percent, the vulnerable subgroups would have been more impacted by the MMA lock-in provisions than others because they made a greater number of health plan changes per beneficiary and left their GHO midyear.

It is important to note that although in most cases we found evidence of only small differences in lock-in provision impacts, the traditionally vulnerable subgroups will likely have a much more difficult time than others in comprehending the many 2003 MMA reforms because of lower physical and mental health status and lower literacy levels. Lock-in rules will add another layer of complexity to their decisionmaking. Additionally, the combination of MA plan and new Part D prescription drug plan election limitations has the potential to further confuse and restrict beneficiaries' decisions. During the OEP, beneficiaries may only switch to the same type of health plan that they selected during the previous fall (either with drug coverage or without), and may not make an election that would result in their adding or dropping prescription drug coverage (Code of Federal Regulations, 2005).

CMS might consider the following steps to mitigate the potential for greater negative lock-in impacts on traditionally vulnerable subgroups. First, CMS can focus its communications of the lock-in provisions on all vulnerable subgroups, but particularly on racial/ethnic minority groups (notably Black beneficiaries), to ensure they understand the full ramifications of their health plan decisions.

Second, in anticipation of potentially large impacts on Medicaid eligibles, CMS has already established a continuous SEP for this group of Medicare beneficiaries under its legal authority to establish a SEP when an individual meets exceptional conditions. Medicaid eligibles and health plans can also be made aware of this exception to reduce artificial restriction of Medicaid eligibles' health plan choices.

Third, CMS can provide strong guidance to MA plans that fully explain the enrollment lock-in provisions in their beneficiary marketing materials. This may be very difficult to do this year, though, because of the many competing messages that CMS and plans must disseminate during 2005 to inform beneficiaries of the several Medicare Program reforms.

Fourth, the 2003 MMA legislation includes provisions that permit GHO disenrollment at any time if an enrollee can demonstrate that marketing abuses occurred, medically necessary care was denied or delayed, or that inadequate quality of care was provided. CMS can take strong steps to ensure that these protections are effective in order to moderate the potential effects of the disenrollment limits for at-risk GHO enrollees.

Acknowledgments

The author appreciates the review and valuable comments received from Mary Kapp, CMS, as well as the considerable analytic support and assistance provided by Gabrielena Alcala-Levy, BearingPoint.

Footnotes

The author is with Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. The research in this article was supported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under Contract Number 500-95-0057(TO#4) while the author was at BearingPoint, Inc. The statements expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of Mathematica Policy Research, BearingPoint, or CMS.

The MA AEP for CY 2006 has been extended to run from November 15, 2005-May 15, 2006. The MA OEP for CY 2006 will consist of the first 6 months of 2006.

The 2003 MMA includes special election periods that allow certain beneficiaries who would otherwise be subject to lock-in rules to change health plans under circumstances specified in statute.

This study discusses outcomes only for beneficiary characteristics often associated with traditionally vulnerable beneficiary subgroups. Results for other analytic variables, however, are displayed in the regression results tables.

For additional information, please refer to Laschober, 2004; Barents Group, 2002; Nelson et al., 1996; Physician Payment Review Commission, 1996; Clement et al., 1994; and Porell, 1992.

GHOs refer collectively to all Medicare managed care plans - MA plans, cost health maintenance organizations, demonstration plans, Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly plans, and Health Care Prepayment Plans.

Congress first included the lock-in provisions in the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, but twice delayed their implementation. The provisions are currently retained in the final Title II MMA Federal regulations.

For example, a beneficiary might disenroll from one GHO at the end of one month and join another 20 days later, but the new GHO enrollment would not be effective until the following month.

We could only identify as Medicaid eligible those GHO enrollees for whom the beneficiary's State pays the Medicare Part A and/or B premium or who were receiving Social Security Income benefits.

Because our data set does not contain a direct indicator of beneficiary health status, we did not examine this characteristic in the current study.

Additional information on data construction and variable definitions and values is provided in BearingPoint (2004), and can be obtained from CMS.

Several key findings were reproduced using the entire GHO Spell and Beneficiary files. In all cases, these figures differed from random sample figures only in the fourth or higher decimal place.

A permanent move is distinguished in this study from repetitive moves to and from the same market area over the 3 years of the study that might occur by so-called snowbirds.

Like this study, Riley and colleagues (1997) could not identify all HMO enrollees who were Medicaid eligible but only those for whom the beneficiary's State pays the Medicare Parts A and/or B premium.

In States that permit Medicare beneficiaries to enroll in both Medicare and Medicaid managed care plans simultaneously, some are allowed to receive both sets of benefits within the same health plan, but some can only receive them from two unrelated plans (Walsh and Clark, 2002).

In all 3 years, racial/ethnic minority and disabled GHO enrollees under age 65 were both more likely to be Medicaid eligible than age 65 or over or White GHO enrollees.

Reprint Requests: Mary Laschober, Ph.D., Mathematica Policy Research, 600 Maryland Ave. SW, Suite 550, Washington, DC 20024. E-mail: mlaschober@mathematica-mpr.com

References

- Achman L, Gold M. Trends in Medicare+Choice Benefits and Premiums, 1999-2002. Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; Nov, 2002. Report to The Commonwealth Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Barents Group. Implementation of the Medicare Managed Care CAHPS: Year-Two Report of Subgroup Analysis. 2002. Report to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Google Scholar]

- BearingPoint Inc. Impact of Medicare+Choice Lock-In Provisions: 1999-2002 GHO Spell-Level and Beneficiary-Level DataBase Description and Dictionary. Nov 23, 2004. Report to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Google Scholar]

- Clement DG, Retchin SM, Brown RS, et al. Access and Outcomes of Elderly Patients Enrolled in Managed Care. JAMA. 1994 May;271(19):1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Code of Federal Regulations. Medicare Program. Establishment of the Medicare Advantage Program. 2005 Mar 22; Title 42-Public Health. Parts 417 and 422. Internet address: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/medicarereform/pdbma/4069-F.pdf (Accessed 2005.)

- Dallek G, Biles B, Dennington A. The 2002 Medicare+Choice Plan Lock-In: Should It Be Delayed? Center for Health Services Research and Policy of The George Washington University Medical Center; Nov, 2001. Issue Brief. Publication Number 510. Prepared for The Commonwealth Fund. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschober M. Why Do Beneficiaries Leave their Medicare+Choice Plans: Analysis of the 2000 and 2001 CAHPS Disenrollment Surveys. BearingPoint, Inc.; Dec 20, 2004. Report to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Google Scholar]

- Lied T, Sheingold S, Landon B, et al. Beneficiary Reported Experience and Voluntary Disenrollment in Medicare Managed Care. Health Care Financing Review. 2003 Fall;25(1):55–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L, Brown R, Gold M, et al. Access to Care in Medicare HMOs, 1996. Health Affairs. 1997 Mar-Apr;16(2):148–156. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physician Payment Review Commission. Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Porell FW. Factors Associated with Disenrollment from Medicare HMOs: Findings from a Survey of Disenrollees. Health Policy Research Consortium of Brandeis University; Boston, MA.: Jul, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Riley G, Ingber M, Tudor C. Disenrollment of Medicare Beneficiaries from HMOs. Health Affairs. 1997 Sep-Oct;16(5):117–124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.5.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General. Review of Inpatient Services Performed on Beneficiaries After Disenrolling from Medicare Managed Care. May, 1999. Publication Number A-07-98-01256.

- Walsh EG, Clark WD. Managed Care and Dually Eligible Beneficiaries: Challenges in Coordination. Health Care Financing Review. 2002 Fall;24(1):63–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]