Abstract

We evaluate the extent to which the Ohio Medicaid Program serves as a safety net to terminally ill cancer patients, and the costs associated with providing care to this patient population. Over a 10-year period, Ohio Medicaid served nearly 45,000 beneficiaries dying of cancer, and spent more than $1 billion in medical care expenditures in their last year of life. Eighty percent of the expenditures were incurred by 67 percent of the decedents who had been enrolled in Medicaid for at least 1 year before death, implying an opportunity for the Medicaid Program to ensure timely transition to palliative care and hospice.

Background

Numerous studies have shown greater mortality among Medicaid beneficiaries and the uninsured, compared to those with employer-sponsored health insurance (Ketz et al., 2004; Sorlie et al., 1994; Carr et al., 1989; Nersesian, 1985). Cancer-related disparities by Medicaid, insurance, and socioeconomic status have also been well-documented (Osteen et al., 1994; Mitchell et al., 1997; Roetzheim et al., 2000a, b; Brooks et al., 2000; Bradley, Given, and Roberts, 2001; Richardson, 2004).

Medicaid serves as a safety net to individuals faced with the health care needs and expenses accompanying the new diagnosis of a catastrophic illness, and/or as they gradually become depleted of resources with the progress of a chronic disease. Relative to cancer, this has been evidenced by the sizable proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries with breast cancer enrolling in Medicaid as they are diagnosed with cancer (Perkins et al., 2001; Bradley, Given, and Roberts, 2003; Koroukian, 2003). Studies have further shown that the likelihood of presenting with metastatic disease is much greater among breast, cervical, lung, and colorectal cancer patients who enroll in Medicaid when they are diagnosed with cancer than those who had been enrolled in Medicaid prior to their diagnosis (Perkins et al., 2001; Bradley, Given, and Roberts, 2003; Koroukian, 2003).

The Medicaid Program thus carries a disproportionate representation of patients with advanced-stage cancer. Despite the unfavorable outlook of these patients' survival (Jemal et al., 2005), and often the prospect of imminent death, the burden posed by terminally ill cancer patients to the Medicaid Program has not been explored. This study aims at filling the knowledge gap relative to the extent to which Medicaid serves as a safety net to dying cancer patients; the types of cancer for which they are treated; the expenditures that they incur; and the type of services they receive as they near death.

Cancer has been identified as the second most costly condition, accounting for nearly $46 billion, or 8 percent of total medical care expenditures in 1997 (Cohen and Krauss, 2003); and although more cancer patients have been using hospice services, the aggressiveness of care in terminally ill cancer patients appears to be increasing over time (Earle et al., 2004). In an era of constrained budgets, the study of expenditures incurred by terminally ill patients will help the Medicaid Program to identify possible cost containment strategies and areas for improving end-of-life care in beneficiaries with short life expectancy.

We hypothesize that because of the safety net feature of the Medicaid Program, a sizable number of terminally ill cancer patients enroll in Medicaid as they near death. We also hypothesize that the patterns in Medicaid expenditures by category of service in terminally ill patients are associated with the patient's demographics and cancer type.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study using linked Ohio Medicaid and death certificate files for patients deceased in the 10-year period July 1992-June 2002. Medicaid enrollment and death files were linked on a year-by-year basis using a deterministic, multistep linking algorithm based on patient identifiers, including social security number (SSN), name, date of birth, and sex. In any given year, nearly 86 percent of all patients were identified successfully in both files by using the most stringent combination of variables, including SSN, first name, last name, and sex; 8 percent were identified based on the combination of first and last name, date of birth (month and year), and sex; and 4 percent were identified by using a combination of SSN, last name, month of birth, and sex. This study was approved by the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services (ODJFS), which administers the State Medicaid Program, as well as by the Institutional Review Board, University Hospitals of Cleveland.

Patient Cohort

Medicaid beneficiaries were included in the study cohort if they were deceased during the 10-year study period and had cancer as the underlying cause of death documented in their death certificate record by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision Clinical Modification ICD-9CM (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006) (ICD-9 range 140-239), and ICD Tenth Clinical Modification (World Health Organization, 2006) (ICD-10 code range C00-D48). Enrollment history prior to death was constructed using Medicaid enrollment files, and expenditures in the last year of life were aggregated using the Medicaid summary expenditures file.

Data Sources

The Ohio death certificate files include death records for almost every deceased individual who had been a resident of the State. In addition to patient identifiers, the death record carries, among others, the date of death as well as the underlying cause of death. Cause of death was documented in ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes in death certificate files for the period 1992-1998, and in ICD-10 diagnosis codes from 1999 onward.

The Ohio Medicaid Enrollment and Summary Expenditures Files (SEFs), compiled on a year-by-year basis, include records for each individual enrolled in the Medicaid Program. In addition to patient identifiers and demographics, the enrollment files include monthly variables indicating an individual's participation in the Medicaid Program in a given month of the year. These monthly variables were used to construct retrospective enrollment history relative to their time of death.

Constructed by the ODJFS, the SEFs include individual-level records for each beneficiary carrying monthly expenditures by category of service, including, but not limited to, inpatient, outpatient, nursing home, pharmacy, and physician services. During months in which a beneficiary did not utilize any services and did not incur any costs to the Medicaid Program, the expenditure variables carry $0 amounts. In months during which the beneficiary was enrolled in managed care programs, the expenditures variables carry dollar amounts resulting from capitation payments, and payments for any carve-out services not covered by managed care programs.

Variables

Dependent

Total expenditures in the last year of life, and average expenditures per person per month (PPPM) are two dependent variables. Expenditures are listed by category of service for inpatient and outpatient hospital, pharmacy, hospice, and nursing home, with the remaining aggregated in “all other”. Because the SEF did not carry a separate category for hospice, expenditures for this category were aggregated from claims data (defined as category of service 65 or provider type 44 in the Ohio Medicaid Program) and appended to the SEF. Similarly, expenditures incurred by beneficiaries who are dually eligible, initially aggregated in the general cross-over category, were reapportioned to reflect cross-over expenditures for inpatient and outpatient hospital and all other services.

Because expenditures are available on a month-per-month basis, we accounted for expenditures incurred in the last year of life, using the date of death retrieved from the death certificate record as the date of reference. Finally, to adjust for the length of enrollment in Medicaid in the last year of life, we calculated the PPPM expenditures.

Month of enrollment in Medicaid relative to the month in which death occurred (the month variable) was coded to 0 or < 1 if the decedent enrolled in Medicaid in the month of death; 1 if the decedent enrolled in Medicaid in the month before death; and 2 if the decedent enrolled in Medicaid 2 months prior to death, and so forth.

Independent

Sex and race variables were retrieved from the Medicaid enrollment files, whereas age originated from the death certificate record. Given the small percentage of non-Black minorities in Ohio during the study period, race was categorized as Black and all others. Patient age at the time of death was defined in the following categories: 0-4, 5-14, 15-29, 30-44, 45-64, 65-84, and 85 or over.

We identified individuals in the eligibility categories of aged, blind, or disabled, and all other. This grouping was based on the fact that 97 percent of decedents were identified as aged, blind or disabled during their month of death. Additionally, we identified dually eligible beneficiary status, based on whether they incurred any crossover expenditures in the year preceding death; and their spend down status, if the monthly eligibility variable in the month of death indicated that to be the case.

Non-malignant comorbid conditions listed in the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index were identified, accounting for all diagnostic codes documented on any non-pharmacy claims for services received in the last year of life (Deyo, Cherkin, and Ciol, 1992). The comorbidity score was categorized as 0, 1, 2, and >= 3.

Categories reflecting the anatomic site of cancer were created using the grouping employed in National Vital Statistics Reports (Anderson et al., 2001). These categories, based on the underlying cause of death, mainly reflect the most frequent cancer diagnoses, rather than their implications relative to patterns in their service utilization or care trajectory. They include malignant neoplasms of colon, rectum and anus (ICD-9 153-154; ICD-10 C18-C21); malignant neoplasm of the pancreas (ICD-9 157; ICD-10 C25); malignant neoplasms of the trachea, bronchus, and lung (ICD-9 162; ICD-10 C33-C34); malignant neoplasm of the breast (ICD-9 174-175; ICD-10 C50); malignant neoplasm of the cervix uteri (ICD-9 180; ICD-10 C53); malignant neoplasm of the prostate (ICD-9 185; ICD-10 C61); malignant neoplasm of the bladder (ICD-9 188; ICD-10 C67); malignant neoplasms of meninges, brain, and other parts of the central nervous system (ICD-9 191-192; ICD-10 C70-C72); malignant neoplasms of lymphoid, hematopoietic, and related tissues (ICD-9 200-208; ICD-10 C81-C96). Cancers not listed in the ranges previously specified were grouped in the all other category.

To account for temporal trends, we included dummy variables defined as study periods 1-4, respectively for years of death 1992-1994; 1995-1997, 1998-2000, and 2001-2002.

Analytic Approach

Descriptive analyses were conducted in strata defined by decedent age, race, sex, eligibility category, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score, anatomic cancer site, and length of enrollment prior to death. Multivariable logistic regression models were developed to identify the predictors of enrollment in Medicaid respectively at 1 year; and at 3 months prior to death, given the patient's enrollment in the last year of life. We included hospice use in the latter model, as we hypothesized that individuals nearing death would likely be enrolled in Medicaid. Multiple regression analyses were also employed to assess the association between PPPM expenditures in the last year of life and decedents' demographic and other attributes. To correct for the skewed distribution of expenditures data, we used the log-transformed PPPM as the outcome variable.

Stratified models by dual eligibility status were developed in the presence of strong interactions between dual eligibility and spend down status. Given the small number of dually eligible beneficiaries in younger age groups, the multivariable models were limited to beneficiaries age 30 years or over. Also, given sex-specific cancers, it was not possible to include the decedent's sex in regression models when cancer types were also accounted for. We opted to include the decedent's sex in the final models, rather than cancer types, because these models were less sensitive to differences in disease trajectories specific to cancer types, and produced more robust estimates.

Results

A total of 47,960 Medicaid beneficiaries were identified by linking Medicaid enrollment and death certificate files on a year-by-year basis, of whom 45,211 were enrolled in Medicaid at least through the month preceding death. In this study cohort, we identified beneficiaries with claims carrying dates of service beyond their date of death. This may be due to a misclassification of a decedent as a Medicaid beneficiary, or an imperfect interface between claims and enrollment data, preventing the system from rejecting claims submitted on behalf of decedents. When examining these claims, we found that a sizable proportion had a date of service beyond the date of death by less than 30 days, while others reflected services received well beyond 30 days after death. Payments made on a monthly basis to some providers, such as nursing homes, might be paid up to 30 days after the actual date of death. Payments made later than 30 days after death were assumed to signify an error in the matching algorithm, and the observation was excluded. Our final study cohort was comprised of 44,509 individuals, all of whom were deceased in the study period 1992-2002 with an underlying cause of cancer. This cohort included 473 decedents (or 1.1 percent of the total) who had been enrolled in managed care at least 1 month during their last year of life. The total expenditures for these decedents amounted to $833,306 (or less than 1/1,000 of the total). Given the negligible representation of managed care enrollees in the study cohort, both in number of individuals and total expenditures, we opted to keep them in the study.

As indicated in Table 1, approximately 60 percent were age 65 years or over, 30 percent were in the 45-64 age group, and less than 10 percent were in the younger age groups. The total Medicaid expenditures incurred by these patients in their last year of life exceeded $1 billion. We observed marked variation in the mean and median PPPM expenditures, with the highest mean and median incurred by beneficiaries in the youngest age groups. The lowest mean and median PPPM were reported among individuals age 65-84, as their total expenditures were shared between the Medicare and Medicaid Programs. Of note is the median PPPM expenditures incurred by beneficiaries in the oldest age group, which were nearly double that of individuals in the 65-84 age group, likely due to long-term care.

Table 1. Distribution of the Study Population, by Demographic Characteristics and Decedent's Associated Medicaid Expenditures: 1992-2002.

| Variables | Study Cohort | Expenditures Total* | PPPM Expenditures 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| n | (% of Total) | Dollar Amount | (% of Total) | Mean Dollars | S.D. (Dollars) | Median Dollars | |

| All Decedents | 44,509 | (100) | 1,051,316,385 | (100.0) | 2,442 | 3,359 | 1,759 |

| Age | |||||||

| 0 to 4 Years | 123 | (0.3) | 12,654,301 | (1.2) | 10,674 | 15,394 | 4,956 |

| 5 to 14 Years | 193 | (0.4) | 19,796,192 | (1.9) | 8,941 | 15,261 | 8,941 |

| 15 to 29 Years | 628 | (1.4) | 43,227,089 | (4.1) | 6,826 | 9,535 | 3,816 |

| 30 to 44 Years | 2,917 | (6.6) | 108,182,006 | (10.3) | 4,120 | 4,830 | 2,918 |

| 45 to 64 Years | 13,354 | (30) | 385,927,097 | (36.7) | 3,336 | 3,698 | 2,466 |

| 65 to 84 Years | 19,949 | (44.8) | 314,917,239 | (30.0) | 1,509 | 1,487 | 1,092 |

| 85 Years or Over | 7,345 | (16.5) | 166,612,461 | (15.8) | 2,001 | 1,196 | 2,075 |

| Race | |||||||

| Black | 9,545 | (21.5) | 243,529,478 | (23.2) | 2,532 | 3,289 | 1,667 |

| All Other | 34,964 | (78.5) | 807,786,907 | (76.8) | 2,417 | 3,377 | 1,778 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 18,006 | (40.5) | 430,182,690 | (40.9) | 2,637 | 3,907 | 1,750 |

| Female | 26,503 | (59.5) | 621,133,695 | (59.1) | 2,310 | 2,921 | 1,766 |

| Eligibility Category | |||||||

| Aged, Blind, Disabled | 43,295 | (97.3) | 1,017,055,523 | (96.7) | 2,418 | 3,162 | 1,772 |

| All Other | 1,214 | (2.7) | 34,260,862 | (3.3) | 3,279 | 7,503 | 923 |

| Eligibility Status | |||||||

| Dually Eligible | 25,515 | (57.3) | 470,138,201 | (44.7) | 1,624 | 1,373 | 1,343 |

| Non-Dually Eligible | 18,994 | (42.7) | 581,178,184 | (55.3) | 3,541 | 4,668 | 2,481 |

| Spend Down Status | |||||||

| No | 26,014 | (58.4) | 671,487,567 | (63.8) | 2,744 | 3,787 | 1,978 |

| Yes | 18,495 | (41.6) | 379,828,818 | (36.2) | 2,017 | 2,581 | 1,337 |

| Anatomic Cancer Site | |||||||

| Colorectal | 4,573 | (10.3) | 98,373,708 | (9.4) | 2,109 | 2,161 | 1,754 |

| Pancreas | 1,634 | (3.7) | 30,608,855 | (2.9) | 2,017 | 2,305 | 1,448 |

| Lung | 12,861 | (28.9) | 257,773,047 | (24.5) | 2,244 | 2,756 | 1,516 |

| Female Breast | 4,267 | (9.6) | 105,736,615 | (10.1) | 2,347 | 2,298 | 1,983 |

| Cervix Uteri | 750 | (1.7) | 22,857,697 | (2.2) | 3,061 | 3,201 | 2,247 |

| Prostate | 1,871 | (4.2) | 35,590,081 | (3.4 | 1,853 | 1,449 | 1,706 |

| Bladder | 914 | (2.1) | 20,011,579 | (1.9) | 2,195 | 2,225 | 1,854 |

| Brain | 1,040 | (2.3) | 30,604,808 | (2.9) | 3,089 | 4,359 | 2,051 |

| Lymph | 3,639 | (8.2) | 135,573,405 | (12.9) | 3,715 | 6,709 | 1,869 |

| All Other | 12,960 | (29.1) | 314,186,590 | (29.9) | 2,500 | 3,327 | 1,855 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | |||||||

| 0 | 19,849 | (44.6) | 341,014,335 | (32.4) | 2,036 | 3,407 | 1,337 |

| 1 | 11,816 | (26.5) | 298,548,931 | (28.4) | 2,537 | 3,129 | 1,946 |

| 2 | 6,437 | (14.5) | 186,418,388 | (17.7) | 2,762 | 3,359 | 2,120 |

| >=3 | 6,407 | (14.4) | 225,334,731 | (21.4) | 3,142 | 3,446 | 2,443 |

| Months of Enrollment Prior to Death | |||||||

| 02 | 1,113 | (2.5) | 3,038,222 | (0.3) | 2,654 | 5,912 | 770 |

| 1-3 | 5,651 | (12.7) | 36,230,983 | (3.4) | 2,208 | 3,733 | 1,105 |

| 4-6 | 3,478 | (7.8) | 52,814,573 | (5.0) | 2,615 | 4,350 | 1,674 |

| 7-9 | 2,348 | (5.3) | 53,836,338 | (5.1) | 2,644 | 3,250 | 1,941 |

| 10-12 | 2,086 | (4.7) | 60,985,641 | (5.8) | 2,539 | 3,607 | 1,987 |

| More Than 12 | 29,833 | (67.0) | 844,410,627 | (80.3) | 2,436 | 2,987 | 1,905 |

| Study Period | |||||||

| 1992-1994 | 10,803 | (24.3) | 193,010,850 | (18.4) | 1,874 | 2,823 | 1,372 |

| 1995-1997 | 13,487 | (30.3) | 295,090,506 | (28.1) | 2,258 | 3,123 | 1,659 |

| 1998-2000 | 13,410 | (30.1) | 350,934,847 | (33.4) | 2,701 | 3,598 | 2,048 |

| 2001-2002 | 6,809 | (15.3) | 212,280,182 | (20.2) | 3,197 | 3,873 | 2,518 |

In the 12 months prior to death; PPPM is per person per month enrolled.

Enrolled in the month of death.

NOTE: S.D. is standard deviation.

SOURCE: Medicaid enrollment and claims data, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, 1992-2002.

Two thirds of decedents had been enrolled in Medicaid 1 year prior to their death, and incurred over 80 percent of the total expenditures. The remaining one-third enrolled in Medicaid in their last year of life, and nearly 15 percent did so in the last 3 months of life. Those enrolling in Medicaid as they neared death incurred markedly lower median PPPM expenditures than those enrolled for longer periods of time.

The results of the logistic regression analysis predicting enrollment in Medicaid in the last year of life showed—both in dually eligible and non-dually eligible—that individuals likely to comprise the Medicaid population in general were less likely to have enrolled in Medicaid in the last year of life (Table 2). This included females, patients of minority descent, and those with higher comorbidity scores. Additionally, we observed a lower likelihood among individuals dying in more recent years to enroll in Medicaid in the last year of life. Of note in this stratified analysis is the marked difference in enrollment patterns by spend down status, between dually eligible and non-dually eligible beneficiaries. Patients on spend down were more likely to enroll in Medicaid in the last year of life if they were non-dually eligible beneficiaries (adjusted odds ration [AOR]: 1.33, 95 percent confidence interval [CI] 1.23-1.43), but less likely to do so if they had dual-eligibility status (AOR 0.47, 95 percent CI 0.44-0.50).

Table 2. Predictors of the Timing of Decedent's Enrollment in Medicaid 1 Year Prior to Death: 1992-2002.

| Variable | Enrollment in Medicaid within the Last Year of Life | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Non-Dually Eligible Beneficiaries | Dually Eligible Beneficiaries | |

|

| ||

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

| Age | ||

| 30-44 Years1 | — | — |

| 45-64 Years | 1.50 (1.36-1.65) | 2.17 (1.55-3.02) |

| 65-84 Years | 3.12(2.79-3.50) | 3.77(2.75-5.17) |

| 85 Years or Over | 2.91(2.50-3.39) | 2.70(1.96-3.72) |

| Decedent 's Race | ||

| Black | 0.49 (0.46-0.54) | 0.73 (0.67-0.79) |

| All Other1 | — | — |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.50(1.41-1.60) | 1.67 (1.57-1.77) |

| Female1 | — | — |

| Spend Down Status | ||

| No1 | — | |

| Yes | 1.33(1.23-1.43) | 0.47 (0.44-0.50) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | ||

| 0 | — | — |

| 1 | 0.41 (0.39-0.46) | 0.50 (0.47-0.54) |

| 2 | 0.35 (0.32-0.39) | 0.34(0.31-0.37) |

| >=3 | 0.20(0.18-0.22) | 0.21 (0.19-0.24) |

| Study Period | ||

| 1992-19941 | — | — |

| 1995-1997 | 0.59 (0.54-0.65) | 0.71 (0.66-0.77) |

| 1998-2000 | 0.51 (0.47-0.55) | 0.68 (0.63-0.74) |

| 2001-2002 | 0.54 (0.49-0.60) | 0.77 (0.69-0.85) |

Reference group.

NOTE: All statistics significant at p< 0.001.

SOURCE: Medicaid enrollment and claims data, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, 1992-2002.

The analysis of enrollment in the last 3 months of life revealed comparable patterns between dually eligible and non-dually eligible beneficiaries with respect to spend down status (Table 3). Therefore, the use of stratified analysis by dual eligibility status was no longer warranted. The directionality of the association between demographic variables and comorbidity scores and enrollment in the last 3 months of life was similar to that yielded by the model predicting enrollment and the last year of life. Individuals with spend down status, and those using hospice were less likely to enroll in Medicaid as they neared death, suggesting that such patients enrolled in Medicaid in earlier months.

Table 3. Predictors of the Timing of Enrollment in Medicaid 3 Months Prior to Death, Conditional on Having Enrolled in Medicaid During the Year Preceding Death: 1992-2002.

| Variables | Enrollment in Medicaid in the Last 3 Months of Life, Given Enrollment in the Last Year of Life |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Age | |

| 30-44 Years1 | — |

| 45-64 Years | 1.54 (1.32-1.79) |

| 65-84 Years | 1.82 (1.57-2.11) |

| 85 Years or Over | 1.27 (1.08-1.50) |

| Race | |

| Black | 0.78(0.71-0.85) |

| All Other1 | — |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1.20(1.12-1.29) |

| Female1 | — |

| Spend Down Status | |

| No1 | — |

| Yes | 0.71 (0.66-0.76) |

| Hospice | |

| No1 | — |

| Yes | 0.71 (0.66-0.77) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | |

| 0 | — |

| 1 | 0.39 (0.36-0.43) |

| 2 | 0.29 (0.25-0.33) |

| >=3 | 0.21 (0.18-0.25) |

| Study Period | |

| 1992-19941 | — |

| 1995-1997 | 1.15(1.05-1.26) |

| 1998-2000 | 1.36 (1.24-1.49) |

| 2001-2002 | 1.42 (1.26-1.59) |

Reference group.

NOTE: All statistics significant at p< 0.001.

SOURCE: Medicaid enrollment and claims data, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, 1992-2002.

Predictors of PPPM expenditures are presented in Table 4. As expected, higher scores of comorbidity were associated with higher PPPM expenditures. A similar, positive trend was noted with more recent years of the study period; however, further calculations reflected an annual increase of 4-6 percent, consistent with inflationary trends over time. In non-dually eligible beneficiaries, older age was negatively and significantly associated with PPPM, likely due to the fact that older individuals might receive less technologically intensive treatment than their younger counterparts. In dually eligible patients, however, age 85 or over was associated with higher expenditures. This likely reflects the fact that the proportion of patients residing in nursing homes is twice as high among dually eligible than among non-dually eligible beneficiaries, and highest in the oldest age group. Spend down status was negatively associated with expenditures due to the patient's participation in reimbursement, while use of hospice was associated with higher expenditures.

Table 4. Predictors of the Average Expenditures Per Person Per Month (PPPM)1 Incurred in the Last Year of Life Study Period: 1992-2002.

| Variable | Parameter Estimate (Standard Error) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Non-Dually Eligible Beneficiaries | Dually Eligible Beneficiaries | |

| Age | ||

| 30-44 Years2 | — | — |

| 45-64 Years | -0.31095(0.04471) | -0.28028 (0.05697) |

| 65-84 Years | -1.46874(0.05228) | -0.27612 (0.05378) |

| 85 Years or Over | -0.66937(0.07106) | 0.25722 (0.05498) |

| Race | ||

| Black | -0.06394 (0.03563) N.S. | -0.15443(0.01680) |

| All Other2 | — | — |

| Sex | ||

| Male | -0.14160(0.03000) | 0.01358 (0.01413) N.S. |

| Female2 | — | — |

| Spend Down Status | ||

| No2 | — | — |

| Yes | -0.09690(0.03451) | -0.10933(0.01370) |

| Hospice | ||

| No2 | — | — |

| Yes | 1.08364(0.03116) | 0.67918(0.01834) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | ||

| 0 | — | — |

| 1 | 1.27234(0.03835) | 0.30541 (0.01672) |

| 2 | 1.44150(0.04919) | 0.44846(0.02012) |

| >=3 | 1.67312(0.04964) | 0.64327 (0.02060) |

| Study Period | ||

| 1992-19942 | — | — |

| 1995-1997 | 0.13500(0.04129) | 0.06179(0.01838) |

| 1998-2000 | 0.31321 (0.04083) | 0.13452(0.01917) |

| 2001-2002 | 0.38199(0.04869) | 0.26969(0.02317) |

N.S. is not significant at p < 0.05.

0.05≤ p ≤0.01.

All other statistics not significant at p < 0.01.

PPPM was log transformed due to its skewed distribution.

Reference group.

NOTE: Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

SOURCE: Medicaid enrollment and claims data, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, 1992-2002.

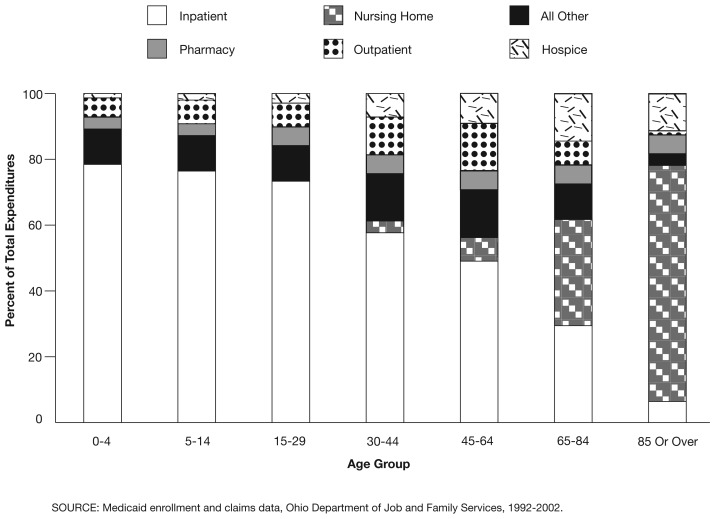

The distribution of expenditures by category of service showed that expenditures associated with inpatient hospital services were highest in the youngest age groups (approximately 80 percent of the total), and nearly non-existent in the oldest age group (Figures 1 and 2). Instead, nursing home expenditures comprised 80 percent of the total expenditures in the age group 85 or over, both in dually eligible and non-dually eligible beneficiaries. Such variations were observed by anatomic cancer site (Figure 3), and by length of enrollment in Medicaid in the year prior to death (Figure 4). We note the 50 to 70 percent share of inpatient expenditures relative to total expenditures among beneficiaries enrolling in Medicaid within 3 months prior to death, implying continued intensity of care, even in patients with very short life expectancy. This finding may also reflect that patients possibly enrolled in Medicaid following admission to the hospital—a move that may have been facilitated by the hospital to ensure reimbursement.

Figure 1. Medicaid Expenditures in the Last Year of Life, by Category of Service, and Decedents' Age Group for Non-Dually Eligible Beneficiaries: 1992-2002.

Figure 2. Medicaid Expenditures in the Last Year of Life, by Category of Service, and Decedents' Age Group for Dually Eligible Beneficiaries: 1992-2002.

Figure 3. Medicaid Expenditures in the Last Year of Life, by Decedent's Category of Service, and Anatomic Cancer Site: 1992-2002.

Figure 4. Medicaid Expenditures in the Last Year of Life, by Category of Service, and Decedent's Length of Enrollment in Medicaid Prior to Death: 1992-2002.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to document end-of-life Medicaid expenditures incurred by Medicaid beneficiaries dying of cancer. Nearly $100 million are spent annually by the Ohio Medicaid Program to care for cancer patients in their last year of life, amounting to more than $1 billion over the 10-year study period. This amount represents less than 2 percent of the $60 billion in total Medicaid expenditures incurred during the study period. On a per capita basis, however, our figures imply $29,384 in the last year of life in 2003 dollars (U.S. Department of Labor, 2006), far exceeding the average annual per capita spending of $1,357 for children, $2,364 for adults, $14,873 for the blind and disabled, and $19,843 for the aged, for the same year (The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2006).

Relative to the safety net aspect of the Medicaid Program, we note that two-thirds of our study population enrolled in the program at least 1 year prior to death, and only 15 percent of beneficiaries came into the program within 3 months of death. Additional studies should be undertaken to evaluate the timely use of hospice and palliative care by Medicaid beneficiaries. However, these patterns place the Medicaid Program in a favorable position in terms opportunities to provide case management services that are tailored to individuals' needs and preferences. For long-term enrollees, the Medicaid Program could monitor the quality of their cancer treatment and followup care, and ensure that transition from curative to supportive/palliative care is made at the appropriate stage of their disease. Short-term enrollees with short life expectancy could be directed to supportive/palliative care as they enter the Medicaid Program.

Consistent with epidemiologic studies on the U.S. population at large (Jemal et al., 2006), 55 percent of the study population died of lung, breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer, all of which are amenable to prevention or screening. While no effective screening is available for early detection of lung cancer, incorporating counseling on smoking cessation should be a priority in all health encounters—not only for Medicaid beneficiaries, but for all patients. Given that economically vulnerable individuals are likely to enroll in Medicaid as their health declines, it is only logical that Medicaid Programs proactively extend lung cancer prevention efforts (e.g., programs aimed at deterring initiation of smoking among adolescents and smoking cessation among smokers) in various health care delivery settings to non-Medicaid populations through various forms. As an example, a partnership between the Oregon Medical Assistance Programs, the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Program in the Oregon Department of Human Services, and 14 health plans has proven successful in smoking cessation efforts among Medicaid-insured Oregonians with asthma (Rebanal and Leman, 2005). As for breast and colorectal cancers, which are amenable to screening, Medicaid Programs can facilitate and increase the use of such services among those already participating in Medicaid. Additionally, it would be desirable for economically disadvantaged, uninsured/underinsured individuals to access colorectal and prostate cancer screening tests, similar to mammography and Pap Smear tests received through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (French et al., 2004).

The temporal effect indicating that patients dying in more recent years were less likely to enroll in Medicaid in their last year of life, but more likely to enroll as they approached closer to death deserves further investigation. We also note the negative association between hospice use and enrollment in Medicaid in the last 3 months of life, suggesting perhaps that patients/families wishing to seek hospice care may have enrolled in earlier months.

The finding that patients with spend down status differ in their likelihood to enroll in Medicaid in the last year of life depending on their dual Medicare-Medicaid eligibility status is of particular interest. These patterns may be associated with differential in the timing and extent of resource depletion in spend down patients who may be on one (Medicaid only), versus two sources of health insurance (Medicare and Medicaid). We note, however, that these findings epitomize the complexity of interactions between Medicaid, Medicare, dual eligibility status, and spend down. Certainly, more detailed analysis is warranted to gain a better understanding of the factors influencing eligible individuals' decision to participate in any or a combination of the programs as they become available to them, their health care needs, as well as their patterns of health services utilization and associated expenditures.

Additional analyses are also needed to better evaluate the quality of cancer and/or end-of-life care received by nursing home residents. In our study cohort, 46 percent of elders in the age group 65-84, and 76 percent of those in the oldest age group had been institutionalized in their last year of life. Previous studies using data from the nursing home minimum data set have documented low utilization of hospice by nursing home residents: 5 percent in patients with cancer overall, and less than one-third judged to be terminally ill by persons completing the minimum data set (Johnson et al., 2005), despite end-of-life care enhancements associated with hospice (Miller, Teno, and More, 2004).

Our findings showed positive association between hospice and PPPM expenditures. We note, however, that a more thorough analysis is required prior to asserting that hospice is in fact associated with more costly care. In particular, the present study does not account for timing of referral to hospice, or if hospice was provided as an add-on to other, more aggressive treatment (Earle et al., 2004; Christakis and Escarce, 1996), factors that have been implicated in the failure to reduce Medicare spending for dying beneficiaries.

That dually-eligible Black beneficiaries incur significantly lower PPPM expenditures than others is somewhat unexpected given findings from a previous study showing that minorities incur higher expenditures than White beneficiaries (Degenholtz, Thomas, and Miller, 2003). These disparities should be investigated further, especially given the homogeneity of study population relative to their socioeconomic status, and their uniform access to health care through the Medicaid Program.

The study presents numerous strengths, the most important of which is the use of population-based linked Medicaid and death certificate data over a period of 10 years, yielding a study population large enough to conduct stratified analyses by a number of covariates. We also note that the data presented in this study can be used to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of cancer screening and prevention programs.

However, we note a number of limitations, first, our study is limited to the Ohio Medicaid population. Variations in eligibility rules and program management may exist across States, and patterns observed in this study may not hold true elsewhere.

Second, in this study we account for Medicaid expenditures only. Therefore, these figures do not reflect charges or additional costs to the health care delivery system that were not covered by Medicaid, or the costs to the society through lost years of productivity and life by younger beneficiaries. We also want to point out that the present study does not analyze Medicaid expenditures in the context of improvements of quality of life, an important element to be considered in future studies.

Third, rather than limiting expenditures to services specific to cancer care, the study accounts for all expenditures incurred by Medicaid beneficiaries dying of cancer. As shown by Brown et al. (2002), however, most Medicare expenditures incurred by cancer patients in the terminal phase period are related to cancer care. It is likely that this holds true in this study as well.

Fourth, this study is based on Medicaid and death certificate files, which were linked by using patient identifiers in multistep algorithms, as previously described. Although misclassifications and mismatches across the files may have occurred, it is unlikely that such errors have resulted in any substantial biases affecting the study findings.

Finally, inaccuracies in the cause of death documented on the death certificate record have been reported previously (Santoso, Lee, and Aronson, 2006; Feuer, Merrill, and Hankey, 1999), and it was not possible to determine whether subjects in our study cohort died in fact of cancer, especially in the absence of any information on cancer stage or recurrence in our data sources. It should be borne in mind that the likelihood of comorbid conditions, rather than cancer, causing death in our older study subjects is quite high.

In closing, we note that in an era of severe budget constraints, the costs incurred by Medicaid beneficiaries dying of cancer are not negligible, especially when considered over the course of several years. The study findings call for the development of tailored case management programs based on patient preferences with regard to intensity of end-of-life care, and transition to supportive/palliative care at appropriate stages of the disease.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lora Summers for providing invaluable guidance in working with the Medicaid Summary Expenditures Files, and Charles Betley, Gregory Cooper M.D., and three anonymous reviewers for their careful review of the manuscript and constructive comments.

Footnotes

Siran M. Koroukian and Mireya Diaz are with the School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University. Elizabeth Madigan is with the School of Nursing, Case Wester Reserve University. Heather Beaird is with the Summit County Health District, Ohio. Siran M. Koroukian, member of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, was supported by the National Cancer Institute under Grant Number K07 CA096705. The statements expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of Case Western Reserve University, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, or the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Reprint Requests: Siran M. Koroukian, Ph.D., Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44106-4945. E-mail: skoroukian@case.edu

References

- Anderson RN, Minino AN, Hoyert DL, et al. Comparability of Cause of Death Between ICD-9 and ICD-10: Preliminary estimates. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2001;49(2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Disparities in Cancer Diagnosis and Survival. Cancer. 2001;91(1):178–88. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<178::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Late Stage Cancers in a Medicaid-Insured Population. Medical Care. 2003;41(6):722–728. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000065126.73750.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SE, Chen TT, Ghosh A, et al. Cervical Cancer Outcomes Analysis: Impact of Age, Race, and Comorbid Illness on Hospitalizations for Invasive Carcinoma of the Cervix. Gynecologic Oncology. 2000;79(1):107–115. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, et al. Estimating Health Care Costs Related to Cancer Treatment from SEER-Medicare Data. Medical Care. 2002;40(Suppl):IV-104–IV-107. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr W, Shapiro N, Heisler T, et al. Sentinel Health Events as Indicators of Unmet Needs. Social Science Medicine. 1989;29(6):705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Internet address: http://www.cde.gov/nchs/about/otheract/icd9/abticd9.htm (Accessed 2006.)

- Christakis NA, Escarce JJ. Survival of Medicare Patients after Enrollment in Hospice Programs. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(3):172–178. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607183350306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JW, Krauss NA. Spending and Service Use Among People with the Fifteen Most Costly Medical Conditions, 1997. Health Affairs. 2003 Mar-Apr;22(2):129–138. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenholtz HB, Thomas SB, Miller MJ. Race and the Intensive Care Unit: Disparities and Preferences for End-of-Life Care. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31(5 Suppl):S373–S378. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000065121.62144.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a Clinical Comorbidity Index for Use with lCD-9-CM Administrative Databases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the Aggressiveness of Cancer Care Near the End of Life. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(2):315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuer EJ, Merrill RM, Hankey BF. Cancer Surveillance Series: Interpreting Trends in Prostate Cancer—Part II: Cause of Death Misclassification and the Recent Rise and Fall in Prostate Cancer Mortality. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91(12):1025–1032. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.12.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French C, True S, McIntyre R, et al. State Implementation of the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000. Public Health Reports. 2004;119(3):279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2005. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics 2006. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VMP, Teno JM, Bourbonniere M, et al. Palliative Care Needs of Cancer Patients in U.S. Nursing Homes. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8(2):273–279. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketz RR, Gimotty PA, Polsky D, et al. Morbidity and Mortality of Colorectal Cancer Carcinoma Surgery Differs by Insurance Status. Cancer. 2004;101(10):2187–2194. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroukian SM. Assessing the Effectiveness of Medicaid in Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2003;9(4):306–314. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SC, Teno JM, More V Hospice and Palliative Care in Nursing Homes. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2004;20:717–734. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Meehan KR, Kong J, et al. Access to Bone Marrow Transplantation and Lymphoma: The Role of Sociodemographic Factors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15(7):2644–2651. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nersesian WS, Petit MR, Sharper R, et al. Childhood Death and Poverty: A Study of All Childhood Deaths in Maine, 1976 to 1980. Pediatrics. 1985;75(1):41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteen RT, Wincester DP, Hussey DH, et al. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 1994;1(6):462–467. doi: 10.1007/BF02303610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins CI, Wright WE, Allen M, et al. Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis in Relation to Duration of Medicaid Enrollment. Medical Care. 2001;39(11):1224–1233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebanal RD, Leman R. Collaboration between Oregon's Chronic Disease Programs and Medicaid to Decrease Smoking among Medicaid-insured Oregonians with Asthma. Prevention of Chronic Disease. 2005 Nov; Spec. No: A12, Epub. Internet address: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2005/nov/05_0083.htm (Accessed 2006.) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Richardson LC. Treatment of Breast Cancer in Medically Underserved Women: A Review. Breast Journal. 2004;10(1):2–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2004.09511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roetzheim RG, Gonzalez EC, Ferrante JM, et al. Effects of Health Insurance and Race on Breast Carcinoma Treatments and Outcomes. Cancer. 2000a;89(11):2202–2213. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11<2202::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roetzheim RG, Pal N, Gonzalez EC, et al. Effects of Health Insurance and Race on Colorectal Cancer Treatments and Outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 2000b;90(11):1746–1754. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoso JT, Lee CM, Aronson J. Discrepancy of Death Diagnosis in Gynecology Oncology. Gynecologic Oncology. 2006;101:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ, Backlund E, et al. Mortality in the Uninsured Compared with that in Persons with Public and Private Health Insurance. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1994;154(21):2409–2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. State Medicaid Fact Sheet. Internet address: http://www.kff.org/MFS (Accessed 2006.)

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics Data. Consumer Price Index for Medical Care. Internet address: http://data.bls.gov/PDQ/servlet/SurveyOutputServlet (Accessed 2006.)

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) Internet address: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ (Accessed 2006.)