Abstract

Long-term care represents a significant burden to the approximately 7 million elderly in need, their families, and the Medicaid program. Concerns exist about access, quality, cost, and the distribution of the burden of care. In this article each area is discussed, highlighting the principal issues, identifying the unique aspects that pertain to long-term care, and exploring the implications for research and policy development. Future trends, especially the growth of the elderly population, are expected to affect significantly the provision of long-term care. The considerable uncertainty about how these trends may impact on long-term care is described, and the critical role social choice will play in shaping the future long-term care system is emphasized.

Introduction1

Considerable and deserved attention is currently focused on the delivery and financing of long-term care. More than 11 million Americans need some form of long-term care arising from chronic illnesses and conditions. Obtaining needed care is critical to the quality of life and sometimes to the survival of those in need. The duration of need, often years and sometimes decades, makes provision of long-term care burdensome and expensive to individuals and their families. Because individuals and families frequently lack the resources for needed care, the responsibility often shifts to the public sector.

Dissatisfaction and concern exist about the long-term care system or the lack of a system. It is often perceived as too expensive, as placing too great an emphasis on institutional care, as providing insufficient access and choice, and as not providing quality care. These concerns are intensified when future trends, which forecast large increases in the demand for long-term care, are juxtaposed with the perceived inadequacy of the current system.

The focus here is long-term care for the elderly. About 7 million elderly people have some type of long-term care dependency, ranging from need for help with ordinary household tasks to need for total assistance in every activity of daily living. It should not be overlooked that focusing on the elderly excludes significant numbers of other persons needing long-term care. Two to three million persons have developmental disabilities or mental retardation requiring substantial assistance. Another 1 to 2 million persons are partially or totally dependent because of chronic mental illness.

Background2

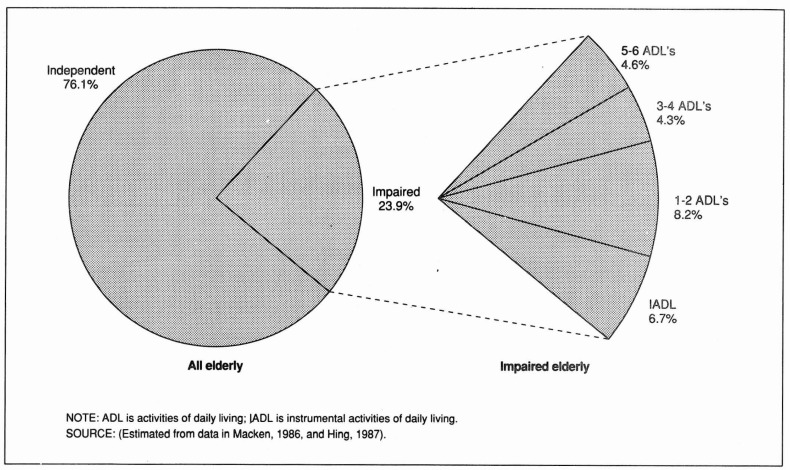

The approximately 7 million elderly persons needing some long-term care assistance comprise 24 percent of the total elderly population (Figure 1). They are dependent in activities ranging from household tasks to personal care. The former are commonly labeled as instrumental activities of daily living (IADL's), and they include tasks such as cooking, cleaning, and shopping. Personal care includes bathing, dressing, transferring, toileting, and eating; and they are labeled activities of daily living (ADL's).

Figure 1. Percent distribution of the elderly, by impairment status and degree of impairment: 1985.

About 30 percent, or 2 million, of the elderly needing long-term care have limited dependencies and require only IADL assistance. At the other end of the spectrum, 20 percent, or 1.4 million, of the elderly are almost totally dependent, needing assistance in virtually every ADL and IADL.

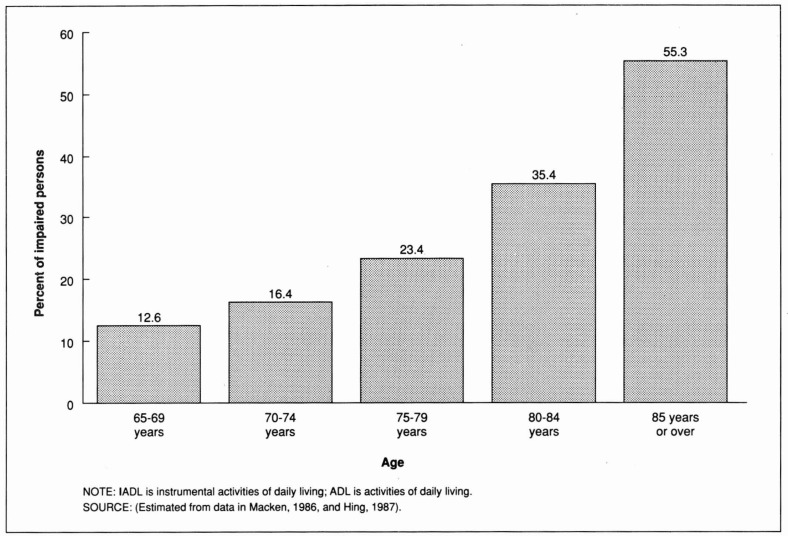

Simply being old does not imply a need for long-term care, as 76 percent of the elderly are fully independent. However, prevalence of long-term care need increases dramatically with age (Figure 2). For the young-elderly population, those between 65 and 69 years of age, 13 percent need some long-term care; among those 85 years of age or over, 55 percent require assistance.

Figure 2. Effect of age on the probability of having an IADL or ADL impairment: 1984-85.

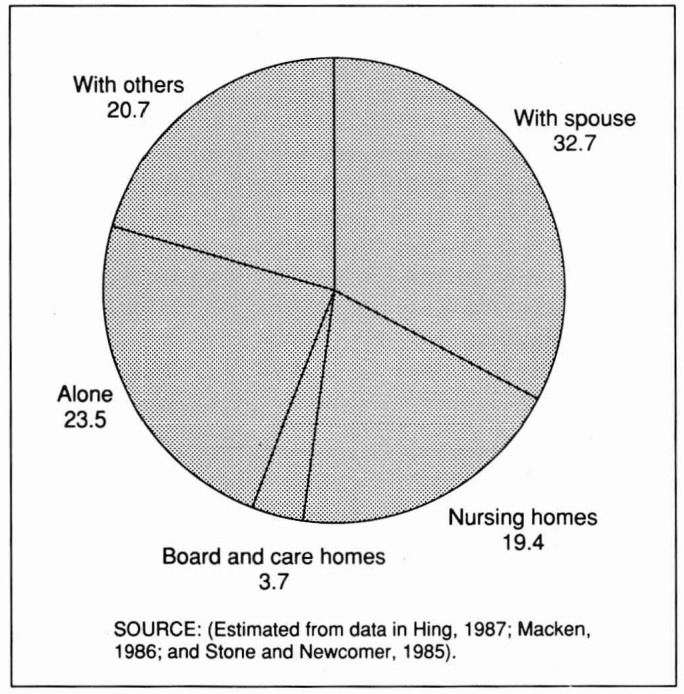

About 22 percent of the elderly long-term care population reside in nursing homes and other institutions (Figure 3). More than 40 percent of the dependent elderly residing in the community live with their spouse, and the remainder are almost evenly divided between those living with others and those living alone.

Figure 3. Percent distribution of the dependent elderly, by living arrangement: 1985.

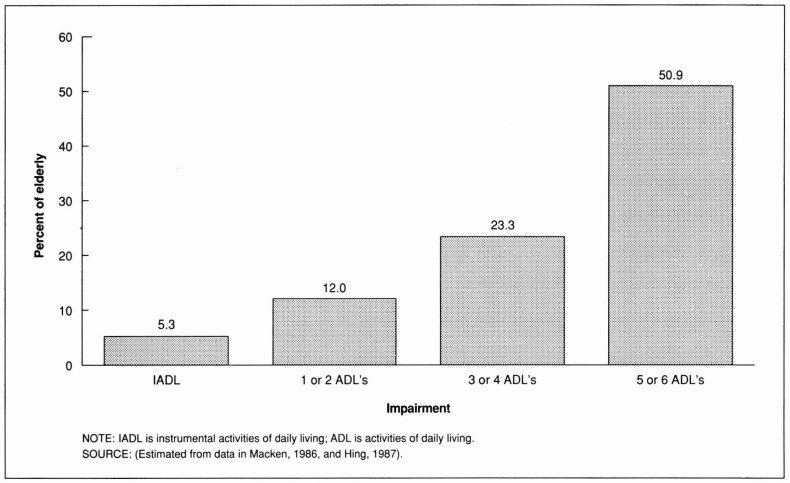

Institutional use increases dramatically with the degree of dependency (Figure 4). Just 5 percent of those with only IADL limitations and about 12 percent of those with only one or two ADL limitations are in nursing homes. In contrast, 50 percent of those with five or six ADL limitations are in nursing homes.

Figure 4. Percent of elderly with different degrees of impairment residing in nursing homes: 1985.

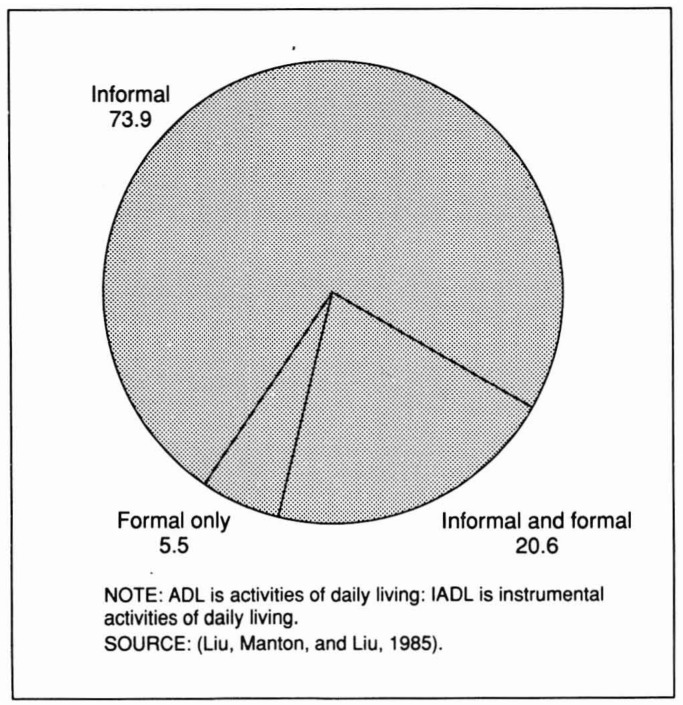

Even for the most extremely impaired, use of a nursing home is not universal. This is both an indication of and a tribute to the amount of care that is being provided in the community, primarily by families. Seventy-four percent of the people that remain in the community get all of their care from informal sources such as family or friends (Figure 5). Only 6 percent of the dependent elderly in the community rely exclusively on formal care sources.

Figure 5. Percent distribution of community residents with ADL or IADL impairments, by source of services: 1982.

Concerns about the current system

Paramount among the continuing concerns regarding the long-term care system are questions of cost and efficiency. Long-term care expenditures amounted to about 45 billion dollars in 1985 (Congressional Budget Office, 1987). Eighty percent went for nursing home care. Spending on nursing homes, the only long-term care service for which spending can be monitored through time, has been one of the fastest growing components of health expenditures. Concern exists that both excessive nursing home utilization and unnecessary increases in cost per day have contributed significantly to the growth in nursing home spending. Such a perception is not uncommon with respect to health care spending in general. However, one needs to be careful about transferring notions of excess and inefficiency that exist regarding the health care system, in particular the acute health care system, to the area of long-term care. Rather than overuse, underuse may be the norm, and the production of services may be relatively efficient. Consequently, extreme caution must be exercised in trying to apply the prescriptions for acute care cost containment (reducing use and reducing unit costs) to long-term care.

Access to care

Despite a popular perception that extensive funding of nursing homes results in inappropriate utilization and the speculation that savings could result from reducing nursing home use by substituting home care, there is a need to be sensitive to the potential shortage of nursing home care. A shortage of beds certainly exists relative to demand. It may also be present with respect to the need for nursing home care.

The bed shortage stems from vigorous longstanding State activities to control Medicaid costs by limiting the supply of nursing home beds. The States have a real stake in controlling costs. Medicaid pays at least some of the costs of care for about 60 percent of nursing home patients. Nursing homes and nursing home expenditures represent about 35 percent of an average State's Medicaid budget.

Evidence of the bed shortage has been accumulating since the early 1970's. Nursing homes in virtually all areas consistently have extremely high occupancy rates. Hospital discharge planners, nursing home administrators, and representatives of long-term care consumers all report placement problems for different types of patients.

More quantitative data also suggest the presence of a shortage of beds. The experience of persons deemed to be at high risk of institutionalization living in areas with different numbers of nursing home beds was compared (Weissert and Scanlon, 1983). These persons were dependent in five to six ADL functions, unmarried, over 75 years of age, and had low incomes. In the 10 States with the largest number of nursing home beds per elderly person, 92 percent of them resided in a nursing home. In the 10 States with the smallest number of nursing home beds, only 54 percent were in nursing homes. This does not imply that 92 percent should be the norm. However, the gap is large enough to suggest that more persons in the low bedded States would enter nursing homes and would be considered appropriately placed if more beds were available.

Although data in the analysis are from 1977 and available data do not permit it to be updated, the situation is unlikely to have improved. Since 1977, nursing home bed growth has not kept pace with the growth or aging of the elderly population. The number of beds relative to the expected number of users has declined 1.2 percent a year. There also has been no significant change in the extreme variation in the number of nursing home beds per elderly across States.

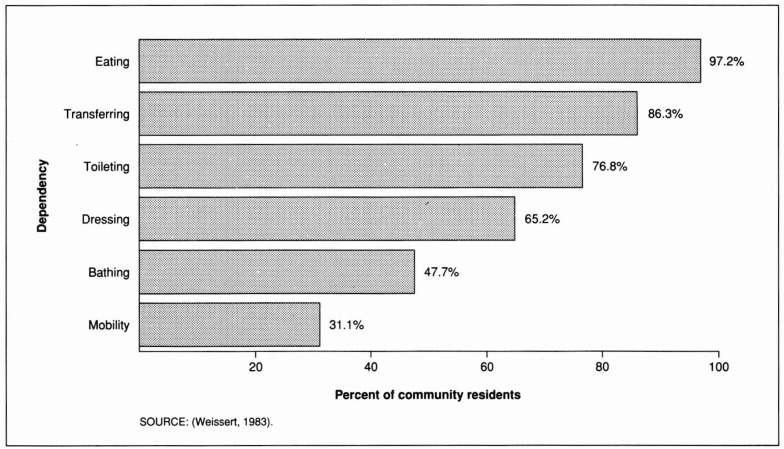

There is also evidence of under service in the community. When persons with ADL impairments were asked in the 1979 National Health Interview Survey whether they were getting all the help they needed, a significant share reported needing more help (Figure 6). Those persons needing assistance in virtually all activities (those with an eating or transferring dependency) got most of the help they needed. Although this is somewhat reassuring, persons with severe dependencies who can not get needed assistance are likely to have to enter an institution. Among the less dependent, the situation is less encouraging. Slightly more than 50 percent of those whose most severe dependency was bathing reported needing more help than they received.

Figure 6. Percent of aged community residents who receive the help they need most or all of the time, by type of dependency: 1979.

Understanding the effects of the shortage is essential to policy development in long-term care. The shortage affects who uses and who does not use various types of care. What has been observed in past programs and research has been influenced by the shortage constraining choices and outcomes. To plan new programs and policies, the lessons that have been learned from the past must be adjusted to take account of the supply of services that will be available.

Efficient production of care

Spending is influenced strongly by how efficiently care is produced (unit costs) in addition to the total volume used. Nursing homes, the recipients of 80 percent of long-term care dollars, have been under considerable pressure to control their costs. Given the strong demand for available beds, attempting to increase this pressure is more likely to adversely affect access and quality of care rather than to simply improve efficiency.

Nursing homes have traditionally had an incentive to avoid unnecessary costs. Private pay and Medicaid patients account for over 90 percent of their revenues. In caring for private patients, costs that do not improve a home's product and enable it to charge more or to attract more private patients simply imply less profit. Lower profits are presumably unappealing in an overwhelmingly proprietary industry.

State Medicaid programs have often added to the pressure to control costs. Many of these programs have put considerable effort into developing reimbursement policies to contain costs. Rather than adopting retrospective cost-reimbursement methods that permit increased costs to become increased revenues, States have long used prospective-reimbursement methods that break the direct link between costs and revenues.

How strongly Medicaid reimbursement policies contain nursing home cost growth varies considerably from State to State and across homes within States. However, the policies do seem to have had an impact overall. Since the 1970's, there has been a major decrease in the growth of nursing home cost per day that is not accounted for by inflation. In the early 1970's, nursing home costs per day grew more than 6 percent per year faster than the prices of nursing home inputs (labor, food, etc.). Since 1977, that unaccounted for growth has dropped to about 2 percent per year.

The higher growth observed in the early 1970's accompanied a major transformation of the nursing home industry. The role of public financing through Medicaid was greatly expanded, and with that came a demand that nursing homes be upgraded. Staffing requirements, both in terms of numbers of staff and higher skill levels, increased. Process regulations were expanded and strengthened. Structural specifications, especially those involving fire safety, became more stringent.

These regulatory reforms induced significant changes in the industry. Many small homes closed, and new larger homes entered the market. Existing homes desiring to continue in business took the necessary steps to meet the new standards. Financing these changes likely accounted for a significant share of the cost-per-day growth in the early 1970's.

The significantly lower growth in cost per day since 1977 can also be correlated with prevailing policies. Until the passage of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987, widespread initiatives to improve quality by increasing standards were absent. Although a desire to control costs undoubtedly contributed to this inaction, concerns that increased resources do not guarantee increased quality also played a role. States were also interested in controlling new bed growth that would add to Medicaid costs. Besides the direct controls they placed on new beds through certificate-of-need programs and moratoria, keeping Medicaid rates low was a means of discouraging investments. Accomplishing this objective became easier as States increased their skill in using reimbursement policies to control costs.

Increasing pressure to reduce future costs may have negative consequences for quality and access instead of producing the desired efficiency gains. Because of virtually guaranteed high occupancy, nursing homes have little need to compete. A likely response to lower Medicaid reimbursement is therefore a reduction in staff and other resources devoted to providing care. Even though inputs and quality may not be perfectly correlated, there is likely a significant relationship. Consequently, aspects of quality would suffer from these reductions.

Reducing payments for Medicaid patients also will adversely affect their access to nursing homes. When Medicaid rates are lower, nursing homes can profit by lowering their private charges to attract more private patients and displacing some Medicaid patients. Unfortunately, from a policy perspective, the Medicaid patients who will likely be displaced are not the potentially inappropriate users of nursing homes— light-care patients who might be served elsewhere. Rather, the marginal Medicaid patient to the nursing home is the heavier care patient for whom the nursing home receives no more revenue, but must incur additional costs. To realign the nursing homes' perspective to coincide more closely with the program's requires a modification of reimbursements to match better rates and patient needs. Case-mix reimbursement systems accomplishing such reform have been implemented in several States (Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, and West Virginia), and they are being planned in several others. These systems can improve access for heavier care patients, but, with the fixed supply of beds, such gains come only by reducing access for others. Whether these displaced patients receive adequate care outside nursing homes should be a significant policy concern.

Little can be said about how efficiently individual community and in-home services are produced. Experience with community and in-home services is much more fragmentary than our experience with nursing homes. Public funding of community care has been limited to a series of demonstration projects, coverage of selected services using normal Medicaid authority by a small number of States, highly targeted programs under the Section 2176 Home and Community Based Care Medicaid Waivers, and small programs financed exclusively from State and local funds. Nevertheless, as this experience expands, it is essential that efficient production be encouraged. The same mechanisms that are employed in the nursing home market are applicable here, namely, use providers who serve private as well as public patients and who therefore face pressure from other markets to be efficient and use reimbursement methods that break the direct link between revenues and costs.

Quality

Interest in quality of care must extend beyond avoiding actions that potentially reduce quality. Promoting and guaranteeing quality should be a central concern in long-term care policy because normal market forces are not available to assure it. In most markets, the spectre of competition is a strong incentive to suppliers to maintain acceptable quality products. Otherwise, consumers will seek alternative suppliers resulting in the “good driving out the bad.”

This market discipline is lacking in the long-term care marketplace, especially the nursing home market, because of a lack of competition. States' efforts to limit the number of beds to control Medicaid costs provide a protective environment for most nursing homes. Operators can have little or no fear that their occupancy will fall or that a new home will try to enter their market even if the quality of care provided is somewhat deficient.

The market for community and in-home services involves no explicit barriers to providers' entry. However, the conditions are not conducive for strong competition. Consumers find it difficult to obtain information on alternative sources of care. The absence of extensive public subsidies and the limited resources of impaired elderly result in a rather weak demand for purchased care and relatively few highly visible organized providers. Most home care involves one-to-one relationships between consumers and providers. Providers have little to fear from having a poor reputation. The home care market is too fragmented for their reputation to be widely known, and their attachment to home care as an occupation is often quite marginal. With their pay near the minimum wage, they often have alternative jobs available at equal wages.

The absence of market forces to assure service quality means that the task must be accomplished largely through regulatory oversight. Although progress has been made in improving the regulatory process, much remains to be done. Efforts to define better what quality is and to develop methods to detect deficiencies need to be continued. Further, means must be found so that deficiencies can be detected in a timely manner without making the inspection process too intrusive or too costly.

Using reimbursement policies to promote and guarantee quality is receiving more attention. As noted earlier, concerns exist that providing additional resources is no assurance of higher quality. Those concerns are valid unless additional payments can be linked to observable measures of quality. Attempts to incorporate such linkages have begun in the Florida and Illinois Medicaid programs.

Establishing stronger incentives for quality within reimbursement systems will require a much better specification of what quality entails, including the inputs, processes, and outcomes that are valued. It is most important to recognize the limits of any endeavor to specify quality. Quality has many intangible aspects. Those measurable phenomena that can be incorporated into reimbursement policy only represent a piece of quality. Care must be taken in designing reimbursement policies that positively promote the measurable aspects of quality to avoid creating a system that discourages provision of other less tangible aspects.

Distribution of the burden

Concerns about the distribution of the burden of long-term care must be added to the usual issues of cost, quality, and access. Long-term care is an exceptional catastrophe. It is the only major catastrophe likely to affect individuals that cannot be mitigated by insurance. The only widespread insurance available is Medicaid, which provides insurance after the fact against further catastrophe. Once one is impoverished by long-term care expenses, Medicaid will provide some support for future expenses. There is no recovery of prior losses.

Needing long-term care is the type of event for which one really should want to obtain insurance. Almost 70 percent of the people 65 years of age or over will die having spent less than a month in a nursing home (Table 1). Almost 80 percent will spend less than 3 months in a nursing home. Only 13 percent will have stays totalling more than a year. Although 13 percent may represent a rather large likelihood for a major catastrophe, it still does not make sense to save for it. For 70 to 80 percent of the elderly, saving for a $40,000 nursing home stay will mean foregoing the use of those savings in anticipation of a catastrophe that never occurs.

Table 1. Lifetime risks and costs of nursing home care at 65 years of age: 1985.

| Length of stay in nursing home | Percent probability associated with this length of stay | Average lifetime cost at $80 per day |

|---|---|---|

| Will not enter a nursing home | 56 | 0 |

| Up to 1 month | 13 | $1,200 |

| 1-3 months | 9 | 4,800 |

| 3-12 months | 9 | 18,000 |

| 1-2 years | 4 | 43,000 |

| 2-5 years | 5 | 102,200 |

| More than 5 years | 4 | 204,400 |

SOURCE: (Greenberg, J., 1987. Based on data from Cohen, Tell, and Wallack, 1986, and Meiners and Trapnell, 1984.)

Private insurance for long-term care is becoming more available. However, the number of policies in effect is still rather small (less than 500,000), and existing policies often provide somewhat limited benefit coverage (Task Force on Long-Term Health Care Policies, 1987). Both insurers' concerns about the risks associated with long-term care policies and consumers' reluctance and inability to purchase them have contributed to this situation. Because these policies are a new product, insurers worry that initial buyers will be more likely to be potential users. Further, the perceived consumer value of many long-term care services, especially home care, raises fears that insurance subsidization will lead to significantly increased use. Insurers have protected themselves by limiting benefits and increasing premiums to protect against the uncertainties involved.

A key to reducing insurers' concerns is the discovery of mechanisms that appropriately control utilization. Only with such control will insurers feel comfortable about reducing premiums and expanding benefit coverage, thereby making policies more affordable and more meaningful.

Developing effective mechanisms will not be an easy task. Success likely depends on securing the cooperation of providers. Pitting utilization reviewers or case managers against the interests and desires of both consumers and providers is not likely to be an effective strategy. Mechanisms that employ financial incentives to create a real stake for providers to control use may be effective and the easiest to implement. Social health maintenance organizations and continuing care retirement communities are obvious examples. However, they may not be the only effective mechanisms; and considerable attention must be given to the incentives for underservice and the limits on freedom of choice such arrangements imply.

Better policies and more information may strengthen the demand for private insurance. The reluctance of the current elderly who can afford one to buy a policy likely stems from both accurate assessments of the limits of many available policies and misconceptions about current Medicare coverage. However, it is critical to recognize that a substantial share of the elderly have limited economic resources and that they are likely to regard even less expensive and more comprehensive policies as beyond their means. Providing catastrophic protection for these persons cannot be accomplished by the private sector alone. Dealing with this significant gap will have to be the government's job.

Leaving the current Medicaid program as government's response would result in essentially a two-class system. Privately insured elderly would be protected from the catastrophe, and persons dependent on Medicaid would remain uninsured until after the catastrophe. The dilemma government faces is that improving its fallback program will undermine the marketing of private insurance. Whether universal or near universal protection against long-term care catastrophes can be achieved with the government and the private sector working independently is uncertain. Either government may have to assume full responsibility or a coordinated approach linking public and private efforts may be required.

The future

A considerable portion of the interest in long-term care emanates from concern about the growing elderly population—the demographic imperative. The imperative is real. The number of persons 65-74 years of age will double by the year 2030, and the number over age 80, the primary users of long-term care, will triple by that year (Spencer, 1984).

Significant social and economic trends potentially affecting long-term care are occurring simultaneously. Family size has dropped. Many more women are participating in the labor force, and their likelihood of interrupting careers for nonlabor force activities is much lower. As families, particularly spouses and daughters, have been the primary source of informal care, these changes affect the potential future volume of such care. Somewhat offsetting, however, is the growth of the generally healthy young-elderly population, persons under 70 years of age. The greater wealth of a significant share of the future elderly, both income and assets, may affect the amount of formal care they choose to purchase out of pocket.

The various demographic, social, and economic trends are likely to have conflicting impacts on the demand for and provision of different long-term care services. Some will promote and some will discourage the availability and the purchase of care.

The prevalence and patterns of long-term care needs may shift in the future. Future cohorts will have experienced a lifetime of very different and, presumably, better medical care; and they will have lived different life styles than today's elderly. These factors are expected to influence future mortality rates. It is reasonable to ask: Will morbidity not be affected as well? Prevalence rates could also shift dramatically if future changes in medical care lead to better management of some chronic conditions, such as dementia, osteoporosis, arthritis, or incontinence, which are major contributors to long-term care needs.

Perhaps one of the most critical elements that will shape the future long-term care system will be the choices made regarding the socially acceptable or desired level of service and access. Neither past nor present experience may be the appropriate norm. Will current nursing home utilization levels be acceptable or will it be desirable to continue the reductions in use observed since 1977? Or, given the shortage of care discussed above, will the reversal of that trend to create more access be the goal? The choice that is made strongly affects what is projected for the future. Projections of new nursing home beds needed by the year 2000 based on the 1985 use levels are 20 percent, or 150,000 beds, lower than if the 1977 use levels are to be restored.

Even larger differences would arise if the target for the future is closer to one of the extremes of the current distribution instead of near the average. Will access concerns and less availability of informal care increase the target so that it is close to the current level of use in Minnesota (165 percent of the national average) (Harrington, 1987)? Or will concerns about costs make the target closer to current use in South Carolina (67 percent of the average)? Regardless of the national target, will the considerable variation that exists among States be tolerated?

Experience with formal home care is too limited to speculate about an acceptable target. It is clear that the future will likely involve a major expansion of community and in-home services. Part of this expansion will be a response to the factors affecting the availability of informal care. More important, however, will be the response to the growing recognition that these services have been significantly underprovided and that, in protecting individuals against catastrophe, the potentially excessive burden of informal care needs to be recognized.

Despite the uncertainties, it is obvious that the level of need will be much larger in the future. The appropriate time to seek strategies for meeting these needs is now. Early planning provides more flexibility by increasing the number of feasible methods of confronting the problem. In particular, it affords the opportunity for prefunding, on either an individual or social basis, higher levels of service use than would be deemed affordable if the full bill had to be paid concurrently.

Future strategies must be robust enough to deal with the potentially large variation in levels of need and demand. They must also give particular emphasis to the question of equity regarding the distribution of the burden of long-term care. Policy concerns, to date, have largely focused on efficiency and, to a great extent, that objective may have been achieved. Current dissatisfactions relate to the large price even somewhat efficient delivery of long-term care has entailed and to the fact that, unfortunately, the care delivered has not fully addressed the needs of the long-term care population or its caregivers.

Footnotes

The data presented in this section represent conservative estimates of long-term care populations based on a synthesis of numerous studies evaluated by the Center for Health Policy Studies.

A more detailed overview is presented in Doty, Liu, and Wiener (1985).

References

- Cohen M, Tell EJ, Wallack S. The lifetime risks and costs of nursing home use among the elderly. Medical Care. 1986 Dec.24(12):1161–1172. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. Statement of Nancy M Gordon before the Health Task Force, Committee on the Budget. U.S. House of Representatives; Oct. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Doty P, Liu K, Wiener J. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. Health Care Financing Review. 3. Vol. 6. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Spring. 1985. An overview of long-term care. HCFA Pub. No. 03198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J. Long-Term Care for the Elderly: A Workshop for State Government Officials. Rennsselaerville, N.Y.: Jul, 1987. New approaches to the financing and delivery of long-term care services. Briefing Book. Sponsored by Users Liaison Program, National Center for Health Services Research and Health Care Technology Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington C, Swan J, Grant L, La Plante M. Nursing home bed supply in the States, 1978-1986. Institute for Health and Aging, University of California; San Francisco: Jan. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hing E. Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics. No. 135. National Center for Health Statistics, Public Health Service; Hyattsville, Md.: May 14, 1987. Use of nursing homes by the elderly: Preliminary data from the 1985 National Nursing Home Survey. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 87-1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Manton KG, Liu BM. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. Health Care Financing Review. 2. Vol. 7. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Winter. 1985. Home care expenses for the disabled elderly. HCFA Pub. No. 03220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macken C. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. Health Care Financing Review. 4. Vol. 7. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Summer. 1986. A profile of functionally impaired persons living in the community. HCFA Pub. No. 03223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiners M, Trapnell G. Long-term care insurance: Premium estimates for prototype policies. Medical Care. 1984 Dec.22(10):901–911. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198410000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer G. Current Population Reports. No. 952. Washington: U.S. Bureau of the Census; May, 1984. Projections of the population of the United States by age, sex and race: 1983 to 2080. (Series P25). [Google Scholar]

- Stone R, Newcomer RJ. The State role in board and care housing. In: Harrington C, et al., editors. Long-Term Care of the Elderly: Public Policy Issues. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Long-Term Health Care Policies; Health Care Financing Administration. Report to Congress and the Secretary on Long-Term Health Care Policies. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sept. 1987. HCFA Pub. No. 87-02170. [Google Scholar]

- Weissert W. Project to Analyze Existing Long-Term Care Data: Final Report. II. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1983. Size and characteristics of the non-institutionalized long-term care population. [Google Scholar]

- Weissert W, Scanlon WJ. Project to Analyze Existing Long-Term Care Data: Final Report. III. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1983. Determinants of institutionalization of the aged. [Google Scholar]