Abstract

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is one of the least common of the AIDS-related lymphomas, accounting for less than 1–4% of cases. Clinical manifestations depend on the extent and distribution of disease and, as in the majority of patients no detectable mass lesion is found, symptoms are related to fluid accumulation, dyspnoea (pleural or pericardial effusions), abdominal distension (ascites) or joint swelling. The median survival after diagnosis, even with aggressive chemotherapy, remains poor and remissions are often of short duration. We present the case of a 31-year-old man with AIDS and diagnosis of PEL, in whom sustained and complete remission of the tumour was achieved with adjunctive ganciclovir therapy. Since the disease is so uncommon, there is a paucity of data to guide the treatment of these patients; ganciclovir might be a potential antiviral therapeutic option, as demonstrated by the 2-year remission achieved in our patient.

Background

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is a large B-cell lymphoma typically manifesting as a malignant serous effusion without tumour mass. It is universally associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8, also known as Kaposi's sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus), and often Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), expressing its DNA on malignant cells. Extracavitary PEL refers to histologically indistinguishable solid tumours affecting organs or lymph nodes.1

HHV8 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of PEL, KS and multicentric Castleman's disease through lytic and latent infection. Viral oncogenic products, such as LANA-1, K1 protein, viral (v) cyclin, vFLIP, vInterleukin (vIL)-6 and vIL-8, inhibit tumour suppressor genes, impair apoptosis and promote cell proliferation as well as systemic inflammation.2–4

PEL mostly affects HIV-infected patients and is an AIDS defining condition accounting for less than 5% of HIV-associated lymphomas.5 6

Optimal treatment for PEL is not established due to the rarity of the disease and the absence of clinical randomised trials. Conventional therapy consists of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone) chemotherapy associated with combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in the HIV-infected individual.

Prognosis remains extremely poor with a median overall survival below 9 months.7

Ganciclovir is a herpesvirus DNA synthesis inhibitor. It has been shown to reduce HHV8 replication and to prevent KS in randomised clinical trials, and is therefore proposed as a therapeutic agent in HHV8-associated diseases.8–10

The authors report a case of sustained complete remission of PEL in an HHV8-positive HIV-infected patient treated with adjunctive ganciclovir.

Case presentation

A 31-year-old HIV-infected male patient was admitted in our hospital with fever, profuse diaphoresis, palpitations and fatigue persisting for more than 2 weeks. He had interrupted cART on his own initiative 4 months earlier (emtricitabine/tenofovir and atazanavir/ritonavir with CD4 cell count of 306/µL and undetectable HIV viral load at the time).

His medical history was remarkable for HIV and hepatitis B co-infection, KS treated 6 years earlier as well as HIV-related pancytopaenia.

Physical examination revealed pallor, persistent hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnoea, enlarged liver and spleen, and moderate ascites.

Laboratory findings revealed pancytopaenia (haemoglobin 9.6 g/dL, leucocytes 1900 cell/µL and platelet count of 51 000/µL), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 817 U/L, ferritin 957 ng/mL, C reactive protein 29.1 mg/L, CD4 count 30 cell/µL and HIV viral load 550 000 copies/mL. PCR analysis was positive for HHV8, EBV and cytomegalovirus.

CT scan was performed showing bilateral pleural effusion and partially loculated moderate ascites with diffuse thickening of peritoneum and ureters.

Ascitic fluid analysis revealed 25 000 leucocytes/mL, glucose <10 mg/dL, LDH 4562 U/L and adenosine deaminase 1224 U/L. Blood, urine and ascitic fluid cultures were negative for mycobacteria and other bacteria.

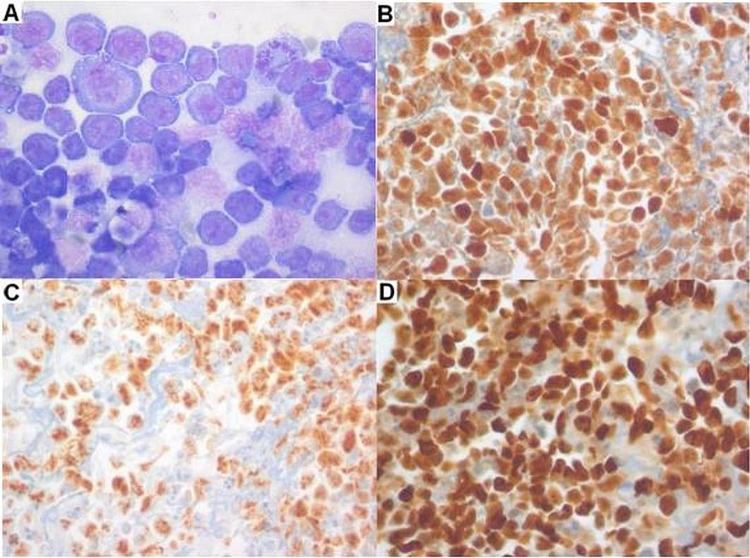

Diagnostic peritoneal biopsy was performed and histology showed extensive peritoneal infiltration with discohesive and pleomorphic intermediate to large cells with scant cytoplasm matching those on ascitic fluid. By immunohistochemistry these cells coexpressed MUM1 (IRF4) and HHV8, and were negative for CD3, CD10, CD20, CD38, CD45, CD138 and PAX5. EBER in situ hybridisation showed co-infection by EBV. The proliferation index (Ki67) was very high (approximately 90%; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ascitic fluid cytology and cell block immunohistochemistry. (A) Pleomorphic intermediate to large cells with amphophilic cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli (Giemsa stain, ×400); (B) positive MUM1 stain (×400); (C) positive human herpesvirus 8 stain (×400); (D) very high proliferation rate with >90% cells positive for Ki67 (×400).

CART was restarted (emtricitabine/tenofovir and raltegravir) and the patient was treated with CHOP chemotherapy and ganciclovir (induction phase for 21 days with ganciclovir 5 mg/kg/12 h intravenously for 7 days followed by valganciclovir 900 mg/12 h per os; and maintenance phase to complete 8 weeks of treatment with valganciclovir 450 mg/12 h per os). Clinical improvement allowed for hospital discharge after 1 week of therapy. Treatment was uncomplicated achieving complete PEL remission and control of HIV infection at 6 months. The patient keeps poor adherence to medical follow-up and treatment (last CD4 count 82 cell/µL, viral load 151 copies/mL) but he is doing well without clinical or imagiological (CT scan) recurrence of PEL at 48 months.

Discussion

There is growing evidence linking viral infection to oncogenesis and progress has been made in understanding the pathophysiology of PEL and HHV8 infection.

In a series of 104 HHV8-positive patient with PEL Castillo et al found survival to be associated with the location and number of affected body cavities. Median survival was 18 months if one body cavity was involved versus 4 months if more than one body cavity was involved; and longer in patients with single pericardial involvement than in those with single pleural or peritoneal involvement (40, 27 and 5 months, respectively).7

Novel therapeutic approaches are being sought to treat this high-mortality HHV8-associated lymphoma. These include inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factors (antisense oligonucleotide to vascular endothelial growth factor), tyrosine kinases (c-kit inhibitors), matrix metalloproteinases (COL-3), mTOR kinases (rapamycin), proteasome inhibitor (bortezomib) as well as anti-IL-6, CD20 and CD30 monoclonal antibodies (atlizumab, rituximab and brentuximab) and antiviral agents (ganciclovir, foscarnet and cidofovir).3 4 10–12 Even so, results have been disappointing so far and reports on the use of ganciclovir in PEL treatment are scarce with fatal outcomes.13–15

The HIV-infected patient with PEL presented in this report had more than one body cavity involvement, including peritoneum and pleura, and systemic HHV8-associated inflammatory syndrome.4 Despite his critical condition and poor expected prognosis immediate clinical improvement was seen after initiation of treatment and survival is currently over 2 years with sustained complete PEL remission.

The clinical relevance and benefit of ganciclovir in the treatment of this HHV8-associated fatal disease is so far to be determined. We provide a table (table 1) with characteristics of the cases, reported so far in the literature, of patients treated with conventional chemotherapy as well as antiviral-targeted therapy for this type of lymphoma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of sustained complete remission of PEL in an HIV-positive patient treated with ganciclovir. We believe this case may favour the potential benefit of using ganciclovir as adjunctive therapy in the early phase of PEL treatment.

Learning points.

Primary effusion lymphoma:

HHV8-associated disease.

Rare HIV-associated lymphoma.

Systemic HHV8-associated inflammatory syndrome.

Conventional chemotherapy with very poor prognosis.

Ganciclovir presents as a potential therapeutic option.

Table 1.

Literature case reports of combined chemotherapy and adjunctive antiviral therapy for Primary-effusion Lymphoma

| Patient | Age | Gender | Effusion | HIV | Prior antiretroviral therapy | Treatment | Response | Follow-up (months) | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 79 | Male | Pl, Pt, Pc | Neg | Valganciclovir | Failure | 3 | Lymphoma | |

| 2 | 69 | Male | Pl, Pt, Pc | Neg | Valganciclovir, CHOP | Failure | 5 | Lymphoma | |

| 3 | 38 | Male | Pl | Pos | Yes | Ganciclovir* | Complete remission | 9 | HPS, KS |

| 4 | 78 | Male | Pl | Neg | Cidofovir (intrapleural) | Complete remission | 15 | † | |

| 5 | 40 | Male | Pl, Pt | Pos | Yes | Cidofovir, IFN-α | Complete remission | 28 | † |

| 6 | 44 | Male | Pl, Pt | Pos | Yes | Cidofovir, IFN-α | Partial response | 6 | Lymphoma |

| 7 | 42 | Male | Pl, Pt | Pos | Yes | Cidofovir, IFN-α | Complete remission | 29 | † |

| 8 | 41 | Male | Pl, Pt | Pos | Yes | Cidofovir*, prophylactic valganciclovir | Complete remission | 68 | † |

| 9 | 96 | Male | Pl | Neg | Cidofovir (intrapleural) | Complete remission | 10 | Lymphoma, heart failure | |

| 10 | 70 | Male | Pt | Neg | Cidofovir (intraperitoneal) | Complete remission | 5 | Lymphoma (pleura), stroke | |

| 11 | 77 | Male | Pl | Neg | Cidofovir (intrapleural) | Complete remission | 15 | † |

Source: Refs. 13–19.

*Additional unspecified chemotherapy.

†=Alive at specified follow-up.

CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone; HPS, haemophagocytic syndrome; IFN, interferon; KS, Kaposi's sarcoma; Neg, negative; Pc, pericardial; Pl, pleural; Pos, positive; Pt, peritoneal.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Fátima Costa, haematologist, with whom we discussed this case and who agreed to apply adjunctive ganciclovir to chemotherapy. We would also like to acknowledge Dr Vítor Brotas and Dr João Calado for their clinical collaboration and orientation.

Footnotes

Contributors: RP, JC and CP wrote and reviewed the manuscript; PF was the anatomic pathologist who collaborated in the diagnosis and provided the pictures.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. World Health Organization classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARCPress, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan RJ, Pantanowitz L, Casper C, et al. HIV/AIDS: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus disease: Kaposi sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:1209–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wen KW, Damania B. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV): molecular biology and oncogenesis. Cancer Lett 2010;289:140–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uldrick TS, Wang V, O'Mahony D, et al. An interleukin-6-related systemic inflammatory syndrome in patients co-infected with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and HIV but without multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:350–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantina H, Wiggill TM, Carmona S, et al. Characterization of lymphomas in a high prevalence HIV setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;53:656–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonelli C, Spina M, Cinelli R, et al. Clinical features and outcome of primary effusion lymphoma in HIV-infected patients: a single-institution study. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3948–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castillo JJ, Shum H, Lahijani M, et al. Prognosis in primary effusion lymphoma is associated with the number of body cavities involved. Leuk Lymphoma 2012;53:2378–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin DF, Kuppermann BD, Wolitz RA, et al. Oral ganciclovir for patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis treated with a ganciclovir implant. Roche Ganciclovir Study Group. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1063–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casper C, Krantz EM, Corey L, et al. Valganciclovir for suppression of human herpesvirus-8 replication: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Infect Dis 2008;198:23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casper C. New approaches to the treatment of human herpesvirus 8-associated disease. Rev Med Virol 2008;18:321–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatt S, Ashlock BM, Natkunam Y, et al. CD30 targeting with brentuximab vedotin: a novel therapeutic approach to primary effusion lymphoma. Blood 2013;122:1233–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casper C, Wald A. The use of antiviral drugs in the prevention and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma, multicentric Castleman disease and primary effusion lymphoma. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2007;312:289–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozbalak M, Tokatlı I, Ozdemirli M, et al. Is valganciclovir really effective in primary effusion lymphoma: case report of an HIV(−) EBV(−) HHV8(+) patient. Eur J Haematol 2013;91:467–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pastore RD, Chadburn A, Kripas C, et al. Novel association of haemophagocytic syndrome with Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related primary effusion lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2000;111:1112–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brimo F, Popradi G, Michel RP, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma involving three body cavities. Cytojournal 2009;6:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halfdanarson TR, Markovic SN, Kalokhe U, et al. A non-chemotherapy treatment of a primary effusion lymphoma: durable remission after intracavitary cidofovir in HIV negative PEL refractory to chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1849–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulanger E, Agbalika F, Maarek O, et al. A clinical, molecular and cytogenetic study of 12 cases of human herpesvirus 8 associated primary effusion lymphoma in HIV-infected patients. Hematol J 2001;2:172–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crum-Cianflone NF, Wallacea MR, Looney D. Successful secondary prophylaxis for primary effusion lymphoma with human herpesvirus 8 therapy. AIDS 2006;20:1561–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luppi M, Trovato R, Barozzi P, et al. Treatment of herpesvirus associated primary effusion lymphoma with intracavity cidofovir. Leukemia 2005;19:473–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]