Abstract

Background: Pregnant women with major depressive disorder (MDD) report that psychotherapy is a more acceptable treatment than pharmacotherapy. However, although results of several studies suggest that psychotherapy is an effective treatment for pregnant women, logistical barriers—including cost and traveling for weekly visits—can limit real-world utility. We hypothesized that computer-assisted cognitive behavior therapy (CCBT) would be both acceptable and would significantly decrease depressive symptoms in pregnant women with MDD.

Methods: As a preliminary test of this hypothesis, we treated 10 pregnant women with MDD using a standardized CCBT protocol.

Results: The pilot results were very promising, with 80% of participants showing treatment response and 60% showing remission after only eight sessions of CCBT.

Conclusion: A larger, randomized controlled trial of CCBT in pregnant women with MDD is warranted.

Introduction

Depression during pregnancy, referred to here after as antenatal depression (AD), affects 10%–15% of pregnant women, making it a national health issue of vital importance.1–3 With roughly four million births each year in the United States, about 500,000 pregnancies are exposed to depression per year. The impact to the mother can be devastating as up to 3% of all pregnant women and 30% of depressed pregnant women report suicidal ideation.4,5 The infant is also at risk as in untreated women, antenatal depressive symptoms have been linked to serious adverse birth outcomes6 such as preterm birth,7,8 lower birth weight,9,10 pre-eclampsia,11 and abnormal infant neuroendocrine development,12 which all have significant long-term health and economic impacts. Beyond the immediate postpartum period, AD continues to have a negative health impact, as it has been associated with impairment in maternal–fetal attachment and abnormal child development.13,14 Despite the importance of recognizing and treating AD, less than half of pregnant women receive appropriate care.15 Pregnant women report several barriers to accessing proper mental health treatment, including stigma, poor access to mental health care, a lack of time and obstetric provider training, transportation, money, and childcare.16,17 Furthermore, with mounting evidence suggesting that antidepressants may adversely affect fetal health,18 perinatal women are reluctant to consider antidepressant treatment with antidepressant acceptability rates only between 10%–20% during pregnancy.19,20 Based on these reported barriers and a reluctance to try medication, the ideal treatment during pregnancy would be a short-term, easy-to-access alternative to pharmacologic antidepressant treatments.

Psychotherapy, the main nonpharmacologic treatment prescribed for depression, has limited data in pregnancy despite its high acceptability among this patient population.17,21 The largest study of psychotherapy for AD was a randomized controlled trial of 12 weeks of interpersonal psychotherapy or a parenting education class which found that both interventions were equally effective (41.9% vs. 48.6% remission rates).22 Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for AD has been associated with better infant orientation, engagement and emotional regulation in women with improvement in their depression symptoms.23 CBT has been studied more extensively for postpartum depression,21 and computer-based interventions for postpartum depression that involved personal coach calls24 or weekly phone call support25 significantly improved symptoms. Modified CBT for women with AD has been attempted in two pilot studies.26,27 Burns et al. (2013) treated 18 pregnant, depressed women with modified CBT and 18 with treatment as usual (TAU). More women in the intervention group (68.7%) no longer met criteria for depression compared with the TAU group (38.5%) at 15 weeks post randomization. In the population of low-income women recruited for the second study, results of the intervention were positive but intensive resources were needed to get women to attend sessions (an average of 2.3 session attendance was achieved). To address the issue of limited resources and access of psychotherapy for pregnant women with depression, we hypothesized that computer-assisted cognitive behavior therapy (CCBT) would be an optimal psychotherapy option for this special population.28 CCBT uses a multimedia program integrated with abbreviated therapy with a clinician.29 In nonpregnant populations, CCBT has shown similar efficacy to the standard form of CBT as well as a high completion rate.30,31 We conducted a standardized case series of CCBT in pregnant women with antenatal depression to evaluate the acceptability and impact on symptom severity.

Methods

Subjects

Eligible women were 18–49 years old, 10–32 weeks gestational age by last menstrual period, with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I).32 Women were recruited from the Penn Center for Women's Behavioral Wellness through advertising and referrals. Subjects were allowed to be on psychotropic medications, but the dose had to be stable for 1 month prior to admission, and concurrent psychotherapy was not allowed. A Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D-17)33 score ≥14 was required for study admission. Participants with comorbid anxiety disorders were allowed as long as it was determined by clinical interview that the primary diagnosis was MDD. Exclusion criteria included the presence of a known abnormality in the fetus; severe or poorly controlled concurrent medical disorders that may cause depression or require medication that could cause depressive symptoms; drug or alcohol abuse history within the previous 12 months; Mini Mental State Examination score <27; lifetime diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, learning disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, or paranoid personality disorder; lifetime history of psychotic disorder, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depression with psychotic features, and bipolar disorder; previous failure to respond to a trial of at least 8 weeks of CBT conducted by a certified therapist; and active suicidal ideation requiring hospitalization.

Study overview

This single-site study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. All subjects signed an informed consent document before undergoing any study procedures. All clinician ratings were done by a trained, blinded rater unaware of study procedures or the hypothesis. Ratings were done at study admission, after sessions four and eight and 3 months after study treatment completion.

Treatment

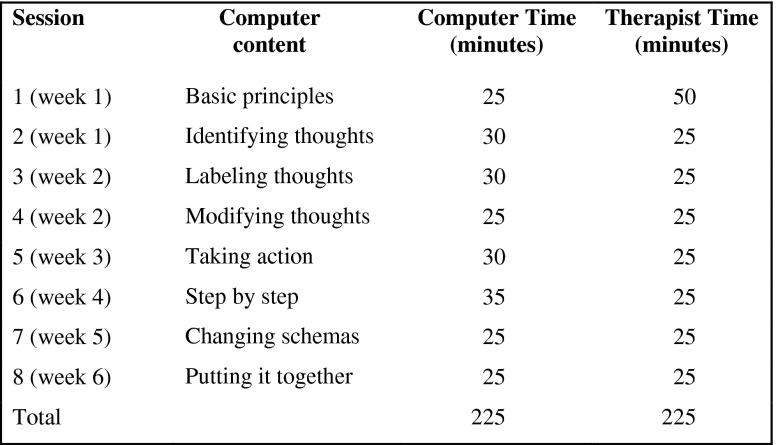

CCBT consisted of eight sessions over 6–8 weeks (∼3.75 total hours of direct therapist contact) (Fig. 1). There was an initial 50-minute session with a therapist followed by a session of approximately 25–35 minutes with the computer software “Good Days Ahead (GDA): The Multimedia Program for Cognitive Therapy.”29 Subsequent CCBT visits began with a 25-minute session with the clinician, followed by a computer session. GDA provides a learning environment that quickly familiarizes users to the basic principles of CBT. They are able to see videos of individuals using CBT skills to cope with depression, access a library of CBT exercises, and perform these exercises as “homework” between therapist sessions. The program is divided into six modules (Basic Principles, Identifying Thoughts, Labeling Thoughts, Modifying Thoughts, Taking Action, Step by Step, Changing Schemas, and Putting It All Together) that cover the core concepts and procedures of CBT for depression. Patients may repeat sections as desired. Patients rate their levels of depression and anxiety on 0–10 point scales each time they start or end a session. Feedback on improvement is shown on colorful graphs. A two-password access system is used to protect confidentiality of subject data. There were two clinicians who were very experienced cognitive behavioral therapists, specifically trained in the use of the CCBT program. Clinician sessions included agenda setting and mood check, brief review of the patient's experiences with the multimedia program, review of how the patient utilized CBT skills in the past week, and orientation to the next session's content. A specific portion of the computer program was assigned after the initial session and for the next session. Previous research has shown that patients typically complete all modules of the software in eight sessions.30 Participants had the option of completing their assigned exercises at home during the week or following their in-office session with the clinician. The CCBT program used was not tailored specifically for pregnant women.

FIG. 1.

Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy schedule of therapy.

Feasibility and outcome assessments

Acute phase

An experienced, blinded evaluator assessed participants pretreatment and after sessions 4 and 8, and again at three months after completion of therapy. Evaluations were conducted without knowledge of the type of intervention being tested or the hypothesis of the study. Response at study endpoint was defined by (a) at least a 50% reduction in the HAM-D-17 score from the subject's pretreatment score, and (b) a HAM-D-17 score ≤10. Responders who ended treatment with a HAM-D-17 score of 7 or less were said to have achieved remission. We tracked completion of each session, medication compliance, consumer satisfaction, and willingness to try CCBT through a treatment diary that asked subjects to indicate adherence such as when they had a scheduled session with their provider and whether they kept that session. All participants completed the Patient Attitudes and Expectations Scale (PAES) pre-, mid- and post-treatment. Developed for use in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program and modified for the current study to include additional items assessing participant's preferences for use of computer-assigned learning paradigms, the PAES enabled us to consider the participant's perceptions about depression and its treatment in relation to their subsequent outcome. A priori questions 6, 7, and 9 of the PAES were picked as secondary outcomes. Questions 6 asks, “What is your attitude toward talking with a therapist/counselor as treatment for your problem?” and is rated between 1 (very positive) and 7 (very negative). Question 7 asks, “What is your attitude toward taking medication as treatment for your problems?” and is rated between 1 (very positive) and 7 (very negative). Question 9 asks, “Overall, how much improvement do you expect to experience as a result of treatment?” and is rated between 1 (not at all) to 7 (great amount). Participants also completed the Beck Depression Inventory34 (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory35 (BAI), and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale36 (EPDS) at each assessment point. The Global Assessment of Functioning37 (GAF) and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems38 were completed at each assessment point. These measures were included to assess improvement in functioning in global, social, and interpersonal domains. In addition, all participants completed the self-report Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire39 pre- and post-treatment.

Structured longitudinal follow-up

All participants were scheduled to return for follow-up evaluations at 3 months after completion of therapy, as well as for more urgent interim evaluations if they were experiencing a symptom exacerbation.

Statistical methods

Descriptive analysis for both aims included graphical assessment of continuously measured factors using box plots, histograms, etc. to assess distributional assumptions. Frequency distributions were computed for categorical data, while means, medians, and standard deviations were computed for continuous data. Treatment adherence was assessed by number of sessions attended and minutes spent on the computer program. We explored whether participant demographics or pretreatment attitudes and expectations differed between treatment responders and nonresponders using chi-square and independent sample t-tests. In addition, we compared consumer satisfaction and willingness to try CCBT versus other treatment modalities prior to and after CCBT using paired sample t-tests. Satisfaction was assessed using the PAES. HAM-D scores at baseline and endpoint were compared using paired sample t-tests. Change in HAM-D score was assessed with linear regression, which examines the score at endpoint while adjusting for baseline levels. This allowed us to assess whether improvement in HAM-D is different for women who have higher scores at baseline (severely depressed), compared to women who are moderate or mild. The influence of demographic factors on the results was investigated; however, the study was only powered to identify large differences.

Results

Subject characteristics

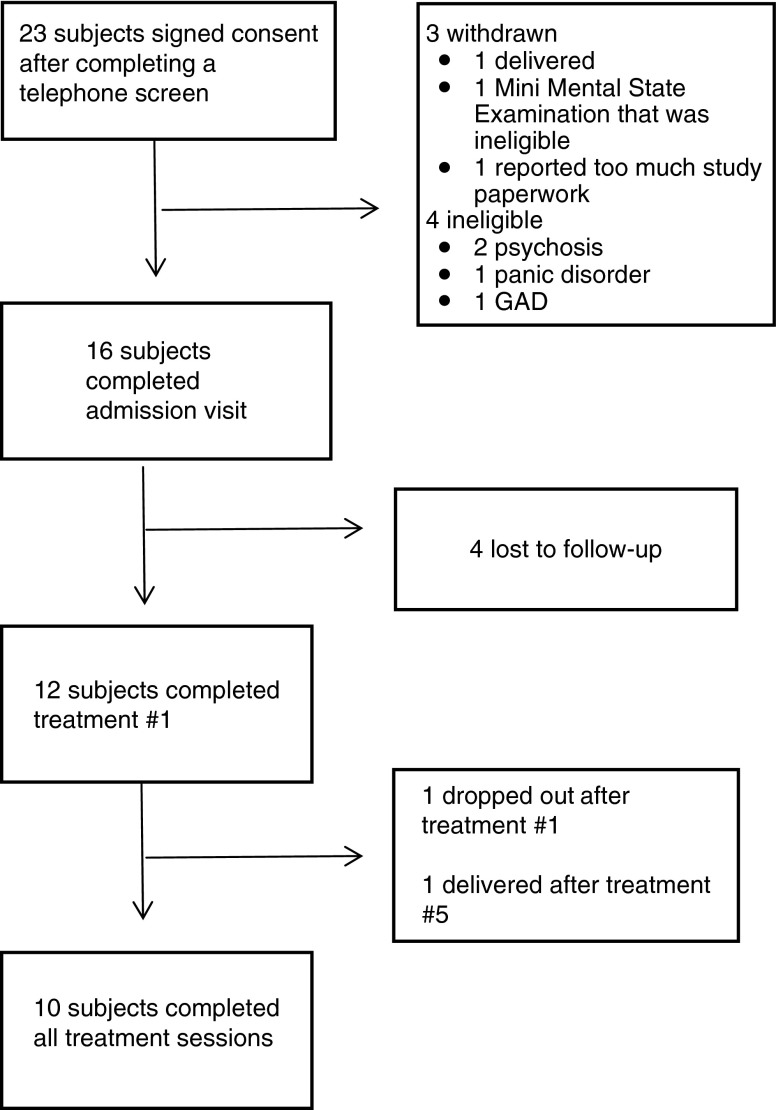

A total of 23 women signed written, informed consent for participation and 12 were found to be eligible for study participation after completing the assessments (Fig. 2). Twelve women initiated treatment and ten women completed all treatment visits. Demographic characteristics of the 12 subjects are shown in Table 1. Eight women were in their second trimester at admission and four were in the third trimester. Eight women were primigravidas. Only one subject was on psychiatric medication during the study for treatment resistant depression. She had no change in her medication for at least 4 weeks prior to study entry. Three women had a history of previous psychiatric hospitalizations, and none of the women reported drug, alcohol, or tobacco use during pregnancy. Married subjects had mean higher baseline EPDS scores compared to nonmarried subjects [17.5 vs. 14.1; t(10)=−2.78, p=0.02]. Past psychiatric history was not associated with baseline depression levels (HAM-D-17 scores) but past therapy exposure was associated with higher baseline BAI scores [18.8 vs. 6.7, t(10)=2.39, p=0.04].

FIG. 2.

Study subject flow chart. GAD, generalized anxiety disorder.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics (n=12)

| Mean age (SD), in years | 29.1 (6.3) |

| Mean gestational age (SD) | 23.8 (7.1) |

| Race (n) | |

| African American | 4 |

| Caucasian | 8 |

| Marital status (n) | |

| Unmarried | 7 |

| Married | 5 |

| Employment status (n) | |

| Full time | 3 |

| Part time | 3 |

| Unemployed | 6 |

| Income (n) | |

| $25,000 | 7 |

| $75–100,000 | 2 |

| $100,000–125,000 | 1 |

| $125,000–150,000 | 1 |

| $225,000–250,000 | 1 |

| Planned pregnancy | |

| Yes | 4 |

| No | 6 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Previous psychotherapy (n) | |

| No | 3 |

| Yes | 9 |

| Previous antidepressant use (n) | |

| No | 4 |

| Yes | 8 |

| Mean time spent on computer portion of CCBT, minutes (SD) | 215.8 (132.5) |

| Mean therapist sessions CCBT (SD) | 7.2 (2.1) |

Significant; p<0.05.

CCBT, Computer-Assisted Cognitive Behavior Therapy; (SD); SD, standard deviation.

Efficacy and attitude toward treatment

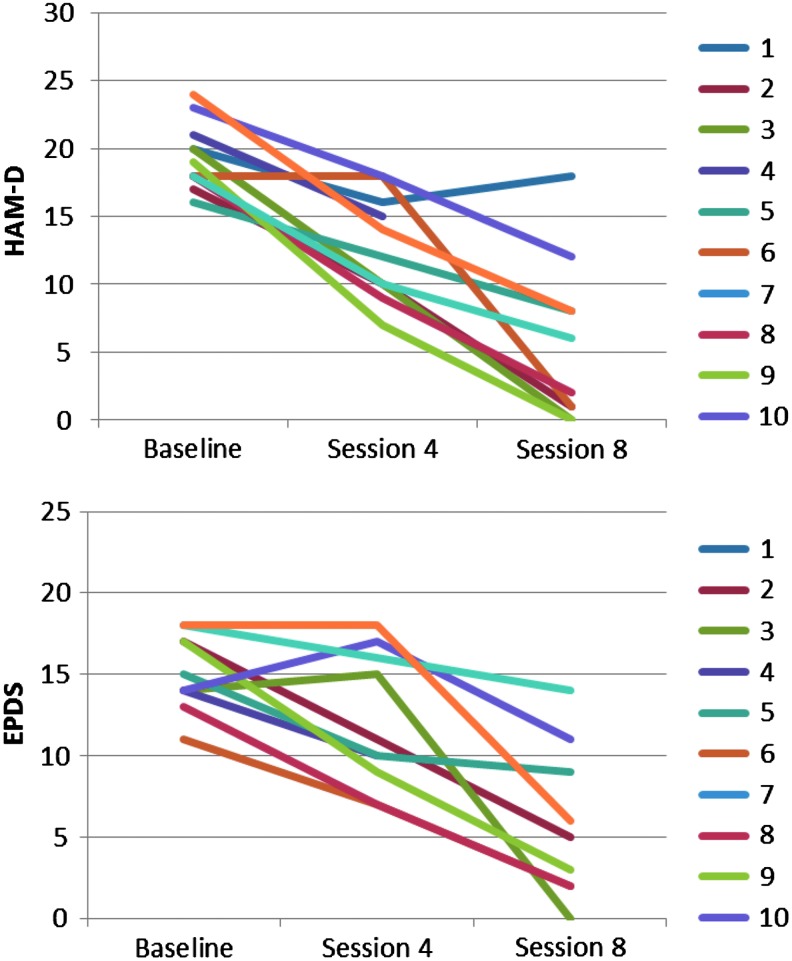

Intent to treat analyses in the 12 women who initiated treatment showed significant improvement in HAM-D score, the primary outcome measure, from baseline to session 8 [19.6 (SD 2.5) to 7.8 (SD 7.5); t(11)=6.23, p<0.001]; 95% confidence interval (95% CI)=7.71–16.13; (Table 2). Among the 10 study completers, 80% (n=8) achieved response, and 60% (n=6) were classified as remitted after session eight. There were no significant differences between responders (defined as 50% HAM-D-17 decrease over eight sessions and HAM-D-17 ≤10 after session 8) and nonresponders in demographic factors including age, education level, parity, marital status, race, planned/unplanned pregnancy, or employment status (p>0.05 for all). There were also no differences between response groups based on clinical factors including number of previous depressive episodes, length of current episode, number of SCID diagnoses, number of hospitalizations, past psychotherapy or past antidepressant use (p>0.05 for all). Intent to treat analyses in the 12 women who initiated treatment showed significant improvement in GAF, HAM-D-17, EPDS, BDI, and BAI (p's<0.043; Table 2, Fig. 3). Subjects spent a mean of 215.8 (SD 132.5) minutes on the computer program Good Days Ahead over the eight sessions. Subjects attended a mean of 7.2 (SD 2.1) in-person therapist sessions. There were no differences between responders and nonresponders in number of CCBT sessions attended or time spent on the computer program [t(5)=0.48; p=0.65]. However, time spent on the computer program was positively correlated with GAF at session 8 [r(55)=0.49, p<0.01; r(5)=0.72, p=0.03] and change in GAF score from baseline to session 8 [r(5)=0.67, p=0.05]. Improvement in HAM-D-17 scores was no different for women who had higher HAM-D-17 scores at baseline compared with women who had lower scores at baseline [F(1, 8)=0.008; p=0.93]. The session 4 GAF score predicted the session eight scores for the HAM-D-17, BDI, EPDS, and BAI but did not predict the session 8 GAF score. No other rating scale scores at session four predicted rating scale scores at session 8. Participants' attitudes toward therapy did not change [t(11)=1.44; p=0.18] between baseline and session 8 (PAES item 6).

Table 2.

Intent to Treat Analyses: Psychological Outcome Measures, Pre- and Post-Treatment (n=12)

| Mean (SD) | Baseline | Week 8 | p Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAF | 55.4 (4.5) | 67.1 (10.4) | 0.002* | −18.1 to −5.2 |

| HAMD17 | 19.7 (2.5) | 7.8 (7.5) | <0.001* | 7.71 to 16.13 |

| EPDS | 15.5 (2.5) | 7.6 (5.3) | <0.001* | 4.9 to 10.9 |

| BDI | 20.8 (5.1) | 7.8 (5.5) | 0.001* | 7.0 to 18.8 |

| BAI | 15.8 (9.1) | 11.4 (8.4) | 0.043* | 0.2 to 8.5 |

| PAES item 6 (SD) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.5 (0.8) | 0.18 | −0.2 to 1.0 |

| PAES item 7 (SD) | 4.1 (2.0) | 4.0 (2.2) | 0.62 | −1.1 to 1.8 |

| PAES item 9 (SD) | 5.3 (1.5) | 5.6 (1.5) | 0.27 | −1.2 to 0.4 |

| QLES raw (SD) | 40.5 (5.7) | 49.6 (8.9) | 0.01* | −15.7 to −2.5 |

| IIP composite | 1.3 (0.46) | 0.9 (0.6) | 0.05* | 0.0 to 0.8 |

Significant, p<0.05.

BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CI, confidence interval; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IIP, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems; PAES; The Patient Attitudes and Expectations Scale; QLES, Quality of Life Scale.

FIG. 3.

Change in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) scores over time.

Eight participants completed the longitudinal follow-up phase (Table 3). At follow-up, one participant was pregnant, while the other seven were postpartum. Among those who completed the follow-up phase, 50% (n=4) were classified as remitters.

Table 3.

Psychological Outcome Measures, Three Months Post-Treatment

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| GAF | 69.00 (14.06) |

| HAMD17 | 12.13 (10.84) |

| EPDS | 11.13 (8.96) |

| BDI | 12.00 (11.40) |

| BAI | 13.50 (13.96) |

We compared those who initiated study treatment (n=12) with those who did not initiate treatment (n=11) and found no significant differences in age, education level, marital status, employment status, income, whether the pregnancy was planned, number of children, previous depressive episodes, length of current depressive episode, previous psychotherapy, history of antidepressant use, or history of psychiatric hospitalization. We did find that those who did not initiate treatment were earlier in pregnancy [M 17.91 (SD 5.39) weeks compared with initiators M 23.78 (SD 7.06) weeks; t(21)=−2.22; p=0.04]. There was a trend among noninitiators such that 72% (8 of 11) were African American and 28% were Caucasian, compared with initiators, of whom 33% (4 of 12) were African American and 67% were Caucasian [χ2 (1, n=23)=3.57; p=0.06].

We also compared those who initiated treatment but dropped out (n=2) to those who completed treatment (n=10). While this is too small a sample to perform meaningful statistical analyses, descriptive statistics showed that both of the women who did not complete treatment were never married (compared with 50% of completers) and were African American (compared with 20% of completers), unemployed (compared with 40% of completers), had incomes less than $25,000 per year (compared with 50% of completers), and had an unplanned pregnancy (compared with 50% of completers). The women who did not complete treatment were younger than the women who did complete treatment [M 22.6 (SD 3.0) years vs. M 30.4 (SD 6.0)], had fewer years education [M 11.5 (SD 0.7) years vs M 16.1 (SD 3.5)], and had more children than those who completed [M 2.5 (SD 2.1) vs M 0.7 (SD 1.9)]. In terms of clinical characteristics, the two women who did not complete treatment reported a higher number of psychiatric hospitalizations than those who completed [M 2.0 (SD 2.8) vs. M 0.4 (SD 0.8)] and included one woman who had a history of antidepressant use (compared with 70% of completers who had previously used antidepressants) and one who had previous psychotherapy exposure (compared with 80% of completers who had previous psychotherapy exposure). The two women who did not complete treatment were similar to completers in terms of baseline HAMD, EPDS, BDI and BAI; they had slightly lower GAF scores [M 50.0 (SD 0.0) vs. M 56.5 (SD 4.1)].

Discussion

In this standardized case series evaluating the feasibility and symptom improvement of CCBT in pregnant women with MDD, CCBT showed promise as treatment for AD, with 80% of participants showing treatment response and 60% showing remission over the course of eight sessions. Because participants took varying amounts of time to complete the eight sessions, the time between pre- and post-assessments varied. In the intent to treat analysis, women showed significant improvement in all depression and anxiety ratings as well as in their global assessment of functioning. In addition, compliance with study procedures was excellent such that the average number of sessions attended was seven out of eight. In a recent meta-analysis of premature therapy termination, the dropout rate for CBT was 18.4 %.40 Another meta-analysis looking at intervention strategies for improving premature termination or therapy refusal found only a small to moderate effect of studied interventions and suggested that patient attendance be a primary outcome as without it all other intervention will obviously not be effective.41 Growing patient competence and familiarity with computer programs and widespread internet availability is allowing for an increased accessibility to mental health treatment for many underserved populations. Pregnant women have many competing demands on their time, and are additionally reluctant to take psychiatric medications during pregnancy.19,20 The possibilities for computer-assisted mental health care are numerous, and a multitude of recent studies have examined the efficacy of computer-assisted or computerized treatment modalities as a treatment for depression in specific populations who are either reluctant to seek treatment, are avoidant, or experience difficulties leaving their home.42–44

CCBT combines a multimedia computer program with abbreviated one-on-one therapist time while maintaining the efficacy of standard cognitive behavior therapy. CCBT delivers therapy while reducing time in the therapist's office and helping improve access to and cost effectiveness of therapy.30,45 Despite concerns that a computer lacks the warmth and empathy of a live therapist, studies show that patients enjoy working with computers.29,45,46 CCBT offers a beneficial balance between traditional therapy and entirely computer-based treatment such that pregnant women may be willing to consider it an acceptable treatment alternative on par with traditional talk therapy. One subject, due to being on bed rest, used Skype to conduct her last two therapy sessions. Since transportation and medical issues can be barriers to treatment, therapy sessions could potentially be delivered in nontraditional settings (such as at home or the obstetrician's office) or through the telephone or video chatting.

The mean gestational age of our participants was 23.8 weeks (SD 7.1). We allowed a wide gestational age for inclusion because our institution has a low preterm birth rate. While antenatal depression is seen in all three trimesters, the rates drop slightly in the second and third trimesters.2 In populations with higher preterm birth rates, CCBT would still be manageable since very few of our women (4 out of 12) started treatment in the third trimester. However, a larger trial would help to further determine the most likely time point when women will enter treatment.

Gender may also be a significant factor in determining an individual's acceptance of computerized psychotherapies. Women have been shown to be significantly more likely to choose psychotherapy or counseling over medication as a treatment for depression; this trend has been demonstrated in samples of patients with and without depression.47,48 We found that as women progressed through the study their attitude towards therapy in general improved significantly.

This study has some limitations. While this preliminary data is encouraging, improvement is often better in open-label compared with randomized trials. Since depression can resolve without intervention, it is possible that some women would have remitted without intervention; however, our inclusion of a significantly depressed population makes a high placebo response rate less likely. Ultimately replicating this finding in a larger, randomized trial would be preferable, but given the low risk of the intervention, CCBT is a reasonable option in women with mild to moderate MDD. In addition, some women will not be compliant with the computer modules and will not get full benefit of the program. We did not test for cognitive or behavioral changes with any standardized measures, which would be an important addition. We were not able to test whether CCBT enhanced overall compliance with ongoing psychiatric treatment, as the vast majority of participants were psychotropic medication naïve. Likewise, the sample size was too small to know whether CCBT would improve adherence to prenatal appointments. In addition, we did not track whether women were less likely to develop postpartum depression, which would be an important future direction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, CCBT is a viable option for pregnant women with mild to moderate MDD based on this case series. Despite the excellent results, tailoring the program for pregnancy may be beneficial. In addition, our results would need to be followed up with a larger randomized trial. The utility of such a program modified for anxiety or bipolar depression would also be important in pregnancy.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: Systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:698–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:1071–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberlander TF, Warburton W, Misri S, Aghajanian J, Hertzman C. Neonatal outcomes after prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and maternal depression using population-based linked health data. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:898–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavin AR, Tabb KM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Katon W. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health 2011;14:239–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newport DJ, Levey LC, Pennell PB, Ragan K, Stowe ZN. Suicidal ideation in pregnancy: Assessment and clinical implications. Arch Womens Ment Health 2007;10:181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grigoriadis S, VonderPorten EH, Mamisashvili L, et al. . The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:e321–e41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:1012–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rondo PH, Ferreira RF, Nogueira F, Ribeiro MC, Lobert H, Artes R. Maternal psychological stress and distress as predictors of low birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;57:266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Dijk AE, Van Eijsden M, Stronks K, Gemke RJ, Vrijkotte TG. Maternal depressive symptoms, serum folate status, and pregnancy outcome: Results of the Amsterdam born children and their development study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:563.e1–563.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DR, Sockol LE, Sammel MD, Kelly C, Moseley M, Epperson CN. Elevated risk of adverse obstetric outcomes in pregnant women with depression. Arch Womens Ment Health 2013;16:475–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus S, Lopez JF, McDonough S, et al. . Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: Impact on neuroendocrine and neonatal outcomes. Infant Behav Dev 2011;34:26–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, Emond A. The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. BJOG 2008;115:1043–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McFarland J, Salisbury AL, Battle CL, Hawes K, Halloran K, Lester BM. Major depressive disorder during pregnancy and emotional attachment to the fetus. Arch Womens Ment Health 2011;14:425–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow F, Barry K. A screening study of antidepressant treatment rates and mood symptoms in pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health 2005;8:25–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, Johnson JV, Ziedonis DM. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in north american outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2012;33:143–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DR, Sockol L, Barber JP, et al. . A survey of patient acceptability of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) during pregnancy. J Affect Disord 2011;129:385–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith MV, Sung A, Shah B, Mayes L, Klein DS, Yonkers KA. Neurobehavioral assessment of infants born at term and in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Early Hum Dev 2013;89:81–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman JH. Women's attitudes, preferences, and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth 2009;36:60–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen I, Gilbert RE, Evans SJ, Man SL, Nazareth I. Pregnancy as a major determinant for discontinuation of antidepressants: An analysis of data from the health improvement network. J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:979–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sockol LE, Epperson CN, Barber JP. A meta-analysis of treatments for perinatal depression. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:839–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spinelli MG, Endicott J, Leon AC, et al. . A controlled clinical treatment trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed pregnant women at 3 New York City sites. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:393–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayden T, Perantie DC, Nix BD, et al. . Treating prepartum depression to improve infant developmental outcomes: A study of diabetes in pregnancy. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2012;19:285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danaher BG, Milgrom J, Seeley JR, et al. . MomMoodBooster web-based intervention for postpartum depression: Feasibility trial results. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Mahen HA, Richards DA, Woodford J, et al. . Netmums: A phase II randomized controlled trial of a guided internet behavioural activation treatment for postpartum depression. Psychol Med 2013:1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burns A O M.ahen H, Baxter H, et al. . A pilot randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for antenatal depression. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Mahen H, Himle JA, Fedock G, Henshaw E, Flynn H. A pilot randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for perinatal depression adapted for women with low incomes. Depress Anxiety 2013;30:679–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hantsoo L, Epperson CN, Thase ME, Kim DR. Antepartum depression: Treatment with computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:929–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright JH, Wright AS, Salmon P, et al. . Development and initial testing of a multimedia program for computer-assisted cognitive therapy. Am J Psychother 2002;56:76–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright JH, Wright AS, Albano AM, et al. . Computer-assisted cognitive therapy for depression: Maintaining efficacy while reducing therapist time. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1158–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spurgeon JA, Wright JH. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2010;12:547–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders- patient edition SCID-I/P. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967;6:278–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56:893–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall RC. Global assessment of functioning. A modified scale. Psychosomatics 1995;36:267–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, Ureno G, Villasenor VS. Inventory of interpersonal problems: Psychometric properties and clinical applications. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56:885–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: A new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993;29:321–326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swift JK, Greenberg RP. Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:547–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oldham M, Kellett S, Miles E, Sheeran P. Interventions to increase attendance at psychotherapy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:928–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi M, Kong S, Jung D. Computer and internet interventions for loneliness and depression in older adults: A meta-analysis. Healthc Inform Res 2012;18:191–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunkeler EM, Hargreaves WA, Fireman B, et al. . A web-delivered care management and patient self-management program for recurrent depression: A randomized trial. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:1063–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moreno FA, Chong J, Dumbauld J, Humke M, Byreddy S. Use of standard webcam and internet equipment for telepsychiatry treatment of depression among underserved hispanics. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:1213–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kenwright M, Liness S, Marks I. Reducing demands on clinicians by offering computer-aided self-help for phobia/panic. Feasibility study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;179:456–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCrone P, Knapp M, Proudfoot J, et al. . Cost-effectiveness of computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care: Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Churchill R, Khaira M, Gretton V, et al. ; Nottingham Counselling and Antidepressants in Primary Care (CAPC) Study Group. Treating depression in general practice: Factors affecting patients' treatment preferences. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:905–906 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:527–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]