Abstract

S-nitrosothiols have been suggested to play an important role in nitric oxide (NO)-mediated biological events. However, the mechanisms by which an S-nitrosothiol (or the S-nitroso functional group) is transferred across cell membrane are still poorly understood. We have demonstrated previously that the degradation of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) by cells absolutely required the presence of cystine in the extracellular medium and proposed a mechanism that involved the reduction of cystine to cysteine, followed by the reaction of cysteine with GSNO to form S-nitrosocysteine (CysNO), mixed disulfides, and nitrosyl anion. In the present study we have assessed the effect of cystine on the transfer of the S-nitroso functional group from the extracellular to the intracellular space. Using RAW 264.7 cells, we found that the presence of l-cystine enhanced GSNO-dependent S-nitrosothiol uptake, increasing the intracellular S-nitrosothiol level from ≈60 pmol/mg of protein to ≈3 nmol/mg of protein. The uptake seems to depend on the reduction of l-cystine to l-cysteine, which involves the  amino acid transport system, the transnitrosation between GSNO and l-cysteine to form l-CysNO, and uptake of l-CysNO via amino acid transport system L. Compared with GSNO, (Z)-1-[N-(3-ammoniopropyl)-N-[4-(3-aminopropylammonio)butyl]-amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate, an NO donor, is much less effective at intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation in the presence of l-cystine or l-cysteine, suggesting that the biochemical changes that occur after exposure of cells to S-nitrosothiol, with respect to thiol chemistry, are distinctly different from those observed with NO.

amino acid transport system, the transnitrosation between GSNO and l-cysteine to form l-CysNO, and uptake of l-CysNO via amino acid transport system L. Compared with GSNO, (Z)-1-[N-(3-ammoniopropyl)-N-[4-(3-aminopropylammonio)butyl]-amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate, an NO donor, is much less effective at intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation in the presence of l-cystine or l-cysteine, suggesting that the biochemical changes that occur after exposure of cells to S-nitrosothiol, with respect to thiol chemistry, are distinctly different from those observed with NO.

Keywords: nitric oxide, amino acid transport, l-cystine

Although S-nitrosothiols have been thought to play an important role in many nitric oxide (NO)-mediated biological events, the processes by which S-nitrosothiol or their bound S-nitroso groups are transferred between the extracellular and intracellular spaces are still poorly understood. Transport mechanisms involving cell-surface protein disulfide isomerase (1, 2), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (3, 4), or anion exchanger (5) have been proposed.

Previous studies have shown that some cellular effects of either S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) or S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) depend on the presence of l-cysteine (6–9). It was suggested that cysteine can increase the efficiency of NO release from GSNO by the formation of unstable S-nitrosocysteine (CysNO) through a transnitrosation reaction (9). Increases in cytosolic GSNO and cysteine levels were observed during the incubation of CysNO with human red blood cells (RBCs), implying the transport of CysNO into RBCs and the transnitrosation between CysNO and cytosolic glutathione (GSH) (10). Mallis and Thomas (8) indicated that a stereospecific transporter is not involved in the direct transfer of CysNO across the cell membrane, because the combination of GSNO with l-cysteine or d-cysteine gave a similar CysNO-like effect. However, other studies indicate that amino acid transporter system L (L-AT) is involved in the uptake of CysNO by cells (7, 11–13). 2-Aminobicyclo[2.2.1]-heptane-2-carboxylate (BCH), a specific L-AT inhibitor, and l-leucine, a substrate for L-AT, were shown to inhibit CysNO-stimulated cellular effects. l-leucine uptake in PC12 cells was inhibited by CysNO, not by SNAP, sodium nitroprusside, 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1)·HCl, (+ or –)-N-{(E)-4-ethyl-2-[(Z)-hydroxyimino]-5-nitro-3-hexene-1-yl}-3-pyridinecarboximide (NOR-4), or sodium nitrite (12). Although these studies suggest the involvement of specific transport mechanisms for S-nitrosothiols, the change of intracellular S-nitrosothiol level was not examined. Consequently, the direct involvement of these pathways in S-nitrosothiol uptake has not been fully assessed.

We have demonstrated previously that the degradation of GSNO by bovine aortic endothelial cells absolutely required the presence of cystine in the extracellular medium (14). We proposed that the mechanism of decay involved the reduction of cystine to cysteine, followed by the reaction of cysteine with GSNO to form CysNO, mixed disulfides, and nitroxyl anion. In the current study, we reassessed the effect of cystine on the transfer of the S-nitroso functional group from the extracellular to the intracellular space by using triiodide-dependent ozone-based chemiluminescence. Using RAW 264.7 cells, we report that the presence of l-cystine enhances S-nitrosothiol uptake by >50-fold, increasing the intracellular levels from ≈60 pmol/mg of protein to >3 nmol/mg of protein. The uptake seems to depend on the reduction of l-cystine to l-cysteine, a process involving amino acid transport system  , the transnitrosation between GSNO and l-cysteine to form l-CysNO, and the uptake of l-CysNO via L-AT. Manipulation of this system will allow the tonal control of intracellular S-nitrosothiol levels, which will facilitate the assessment of the intracellular S-nitrosothiol concentration required to elicit a particular cellular response.

, the transnitrosation between GSNO and l-cysteine to form l-CysNO, and the uptake of l-CysNO via L-AT. Manipulation of this system will allow the tonal control of intracellular S-nitrosothiol levels, which will facilitate the assessment of the intracellular S-nitrosothiol concentration required to elicit a particular cellular response.

Materials and Methods

Materials. l-cysteinyl-glycine, l-cysteine, l-cystine, d-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate, diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA), 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), N-ethylmaleimide, GSH, BSA, d/l-homocysteine, N-acetyl-d/l-penicillamine, iodine, and mercury chloride were purchased from Sigma. Hydrochloric acid, potassium iodide, potassium phosphate dibasic, potassium phosphate monobasic, and sodium hydroxide were obtained from Fisher. d-cystine, l-glutamic acid monosodium salt monohydrate, and sulfanilamide were supplied by Aldrich. (Z)-1-[N-(3-ammoniopropyl)-N-[4-(3-aminopropylammonio)butyl]-amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (spermine NONOate) was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). RAW 264.7 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. DMEM, streptomycin/penicillin, Hepes buffer solution, PBS, and Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) were obtained from GIBCO, and FBS was obtained from HyClone. Oxymyoglobin (oxyMb) was prepared by reduction of metmyoglobin with sodium dithionite and purification on a G25 Sephadex column. OxyMb concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 580 nm (ε580 = 14.4 mM–1· cm–1).

Preparation of S-nitrosothiols. GSNO and SNAP were synthesized as described (15, 16). CysNO was made fresh by mixing cysteine (100 mM) with sodium nitrite (105 mM) in the presence of HCl (100 mM). After 10 min of incubation in the dark at room temperature, NaOH (100 mM) was added. The concentration of each S-nitrosothiol was determined by UV-visible spectroscopy (HP8453 from Hewlett–Packard) using the published extinction coefficient (17, 18). S-nitroso-BSA was synthesized by reaction of GSNO with BSA, and purification on a G25 Sephadex column. S-nitroso-BSA concentration was determined by triiodide-dependent ozone-based chemiluminescence.

Cell Culture and Treatment. RAW 264.7 cells were routinely cultured in DMEM supplemented with pyruvate, l-glutamine, streptomycin (200 μg/ml), penicillin (200 units/ml), and 10% FBS and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% air. For each experiment, cells were seeded onto six-well plates and grown overnight to reach 70–80% confluence. The old medium was removed by double-wash with PBS. Specific compounds were added to cells in either HBSS (supplemented with 10 mM Hepes) or fresh medium (FBS-free) (see details in the figure legends). GSNO stock solution (50 mM in 50 mM phosphate/1 mM DTPA, pH 7.4) was added to cells to a final concentration of 500 μM GSNO and 10 μM DTPA. After treatment, HBSS was sampled, and extracellular S-nitrosothiol levels were measured by UV-visible spectroscopy. Cells were washed three times with PBS, and 250 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM phosphate/1 mM DTPA/50 mM N-ethylmaleimide, pH 7.4) was added to the cells. Cells were scraped and sonicated [550 Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher Scientific), power level 2 for 15 sec] before centrifugation (12,000 × g for 5 min). The supernatant was used for measurement of S-nitrosothiols.

Determination of Thiol Concentration. The DTNB assay was used to measure extracellular thiol levels. Briefly, 1 ml of sample was incubated with 200 μl of DTNB (5 mM in 50 mM phosphate/1 mM DTPA, pH 7.4) for 30 min. The absorbance at 412 nm was measured by UV-visible spectroscopy. Thiol concentration was derived from a standard curve generated by using GSH.

Determination of S-nitrosothiol Level. Triiodide-dependent ozone-based chemiluminescence was used to measure S-nitrosothiol concentration (19–21). The reaction solution was made fresh daily by dissolving potassium iodide (200 mg) and iodine (130 mg) in glacial acetic acid (28 ml) and double-distilled H2O (8 ml). The solution (5 ml) was added into the reaction vessel of a Sievers model 280 NO analyzer and maintained at 30°C. Anti-foaming agent (100 μl) was used to prevent foaming caused by injection of protein-rich samples. An aliquot of the sample was pretreated with 10% (vol/vol) of sulfanilamide (100 mM in 2 M HCl) for 15 min to remove nitrite. Another aliquot was treated with HgCl2 (5 mM) before sulfanilamide treatment to verify the presence of S-nitrosothiols. The S-nitrosothiol concentration was derived by comparing the HgCl2-inhibitable peak area to a standard curve generated by using GSNO.

Results

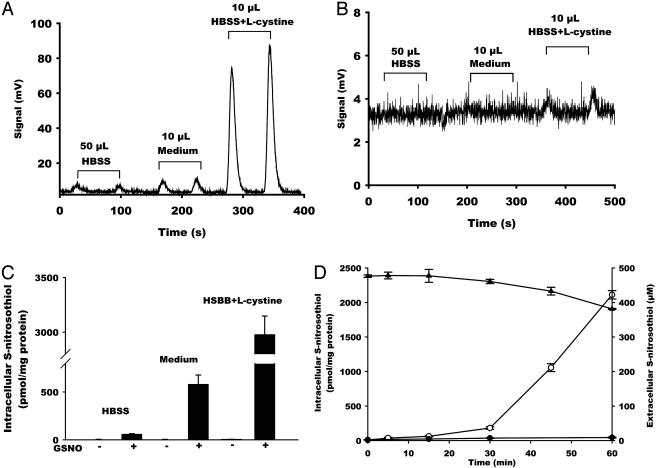

The Effect of l-cystine on GSNO-Dependent Intracellular S-nitrosothiol Formation. S-nitrosothiols were detected by using the triiodide/ozone-based chemiluminescence method in the presence and absence of HgCl2 and sulfanilamide. This method has proven to be a highly specific, reproducible, and sensitive method for the detection of intracellular S-nitrosothiols. Fig. 1A shows raw chemiluminescence data obtained after the incubation of RAW 264.7 cells with GSNO (500 μM, 60 min) in HBSS, FBS-free medium, and HBSS containing l-cystine (200 μM). HgCl2 treatment dramatically reduced the chemiluminescence signal (Fig. 1B); however, in some experiments a small signal was resistant to HgCl2, which likely indicates the concomitant formation of N-nitroso species (20). For quantification of S-nitrosothiol, each measurement was performed with a HgCl2-treated control, and the residual signal was subtracted.

Fig. 1.

The effect of l-cystine on intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with GSNO (500 μM) for 60 min in HBSS, FBS-free medium, or HBSS supplemented with l-cystine (200 μM). Representative chemiluminescence traces of sulfanilamide-treated (A) or HgCl2/sulfanilamide-treated (B) samples are shown. (C) Quantification of S-nitrosothiol content in the cell lysate. Data represent mean ± SEM. (D) Time course of the formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol in the presence (○) or absence (•) of l-cystine as well as the decay of extracellular S-nitrosothiol level in the presence of l-cystine (▴). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Injection of cell lysate from GSNO-untreated cells results in a small signal, as shown in ref. 22, representing 2–3 pmol/mg of protein of S-nitrosothiols (Fig. 1C). Treatment of these cells with GSNO (500 μM) in HBSS resulted in a >10-fold increase (to 58 ± 5 pmol/mg of protein, n = 24) in intracellular S-nitrosothiol content (Fig. 1C and Table 1). In contrast, treatment of cells with GSNO in medium increased intracellular S-nitrosothiol level >100-fold (to 579 ± 97 pmol/mg of protein, n = 6). It is apparent that a component of the medium is stimulating the transfer of the S-nitroso functional group from the outside of the cell to the inside.

Table 1. Intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation.

| S-nitrosothiol content, pmol/mg of protein | |

|---|---|

| GSNO | 58.4 ± 5.0 (n = 24) |

| GSNO + l-cystine | 2977 ± 170 (n = 27) |

| GSNO + l-cysteine | 4180 ± 182 (n = 9) |

| GSNO + d-cystine | 110.7 ± 16.8 (n = 3) |

| GSNO + d-cysteine | 725.2 ± 25.8 (n = 3) |

| GSNO + dl-homocysteine | 2682 ± 230 (n = 3) |

| GSNO + l-cysteinylglycine | 130.4 ± 13.3 (n = 3) |

| SNAP | 34.3 ± 4.4 (n = 6) |

| SNAP + l-cystine | 91.5 ± 3.3 (n = 3) |

| CysNO | 12750 ± 370 (n = 3) |

| CysNO + l-cystine | 12780 ± 420 (n = 3) |

| GSNO + l-cystine + BCH | 1417 ± 35 (n = 3) |

| GSNO + l-cystine + l-leucine | 810 ± 57 (n = 3) |

| GSNO + l-cystine + d-leucine | 2451 ± 260 (n = 3) |

| GSNO + l-cystine + oxyMb | 3443 ± 142 (n = 3) |

RAW 264.7 cells were treated with GSNO, SNAP, or CysNO (500 μM) for 60 min in the absence or presence of various thiols (200 μM), disulfides (200 μM), L-AT inhibitors (BCH, 2 mM, l-leucine, or d-leucine, 1 mM) or NO scavenger (oxyMb, 100 μM). The cells were washed and lysed, and the S-nitrosothiol content in the cell lysate was measured by chemiluminescence. Data represent mean ± SEM.

l-cystine is the sole source of cysteine available to cells in the culture medium. We previously determined that the decay of extracellular GSNO by bovine aortic endothelial cells entirely depends on the presence of cystine in the medium (14). To assess whether cystine is responsible for intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, we incubated the cells with both GSNO and l-cystine (200 μM) in HBSS. As shown in Fig. 1C and Table 1, the presence of l-cystine stimulated the formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol by >50 times (to 2,977 ± 170 pmol/mg of protein, n = 27). In this case, a small (≈3–5% of the total signal) HgCl2-resistant signal was detected (Fig. 1B), indicating formation of other species such as N-nitrosoamines. The presence of l-cystine was sufficient to explain medium-stimulated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation.

The time course of intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation and extracellular decay, when GSNO was incubated with cells in the presence and absence of l-cystine, is shown in Fig. 1D. Intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation had a lag time and accelerated after 30 min of incubation. Extracellular S-nitrosothiol decay mirrored the process of intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, which suggests that the l-cystine-stimulated uptake of S-nitrosothiol is not direct and requires the formation of an intermediate. In addition, the process of extracellular decay and intracellular formation seem to be driven by the same process.

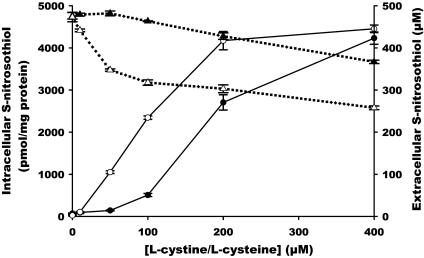

Comparison Between l-cystine and l-cysteine on GSNO-Dependent Intracellular S-nitrosothiol Formation. To determine whether cystine per se or its two-electron reduction product cysteine is responsible for GSNO-stimulated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, we compared the efficacy of both l-cystine and l-cysteine. Concentration dependencies of both l-cystine and l-cysteine are shown in Fig. 2. The l-cystine concentration dependence was sigmoidal in shape, with little effect at <50 μM, and approached saturation at 400 μM. In the case of l-cysteine, the increase in intracellular S-nitrosothiol was essentially linear up to 200 μM l-cysteine, at which saturation occurred. The maximum achieved intracellular S-nitrosothiol concentration was similar with both l-cysteine and l-cystine.

Fig. 2.

Concentration response of l-cystine- or l-cysteine-mediated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation and extracellular S-nitrosothiol decay. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with GSNO (500 μM) in HBSS for 60 min in the presence of various concentrations of l-cystine (filled symbols) or l-cysteine (open symbols). The S-nitrosothiol content in the cell lysate (• and ○) was measured by chemiluminescence. The S-nitrosothiol level in HBSS (▴ and ▵) was detected by UV-visible spectroscopy. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3).

As demonstrated previously in medium (14), l-cystine also stimulated the cell-mediated decomposition of GSNO in HBSS. The loss of extracellular S-nitrosothiol qualitatively reflected the formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol at low concentrations, with significant loss only occurring at >50 μM; however, the decay of extracellular S-nitrosothiol did not saturate. Quantitatively, the loss of extracellular S-nitrosothiol was far greater than the increase in intracellular S-nitrosothiol on a mole-for-mole basis. For example, at the 200 μM point, the formation of 2.7 nmol/mg of protein of S-nitrosothiol is accompanied by the loss of ≈70 μM of extracellular S-nitrosothiol, corresponding to ≈560 nmol/mg cellular protein in 2 ml of medium. l-cysteine also caused a more extensive loss of extracellular S-nitrosothiol than l-cystine, which was apparent at the lowest concentration tested (Fig. 2). As in the case of l-cystine, the decay of extracellular S-nitrosothiol was quantitatively far greater than the formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol.

In combination, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that the reduction of l-cystine to l-cysteine is an essential step in l-cystine-mediated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation.

Specificity of S-nitrosothiol and Thiol in Promoting Intracellular S-nitrosothiol Formation. To determine whether thiols other than l-cysteine can mediate intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with GSNO in the presence of d-cysteine, d/l-homocysteine, or l-cysteinyl-glycine. As shown in Table 1, homocysteine stimulated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, whereas l-cysteinyl-glycine did not. These data suggest that the presence of an extracellular thiol is not sufficient for the formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol, indicating specificity for both cysteine and homocysteine. Both d-cystine and d-cysteine resulted in a lower amount of intracellular S-nitrosothiol than their l isomers (Table 1), suggesting that the S-nitrosothiol uptake process has some chiral specificity.

Table 1 also shows a comparison between GSNO and two additional S-nitrosothiols, l-CysNO and d/l-SNAP (500 μM), in their ability to stimulate intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation in the presence and absence of l-cystine. l-cystine only increased SNAP-stimulated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation by 2.6-fold. Remarkably, incubation of cells with l-CysNO alone resulted in an intracellular S-nitrosothiol content of >12 nmol/mg of protein, >4-fold that observed with GSNO/l-cystine. Assuming an average molecular mass of 70 kDa for cellular proteins, a level of 12 nmol of S-nitrosothiol per mg of protein approximates to 1 S-nitrosothiol per protein. Addition of l-cystine did not increase l-CysNO-stimulated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, suggesting that the presence of l-CysNO is sufficient to induce S-nitrosothiol uptake.

Incubation of cells with S-nitroso-BSA (180 μM S-nitrosothiol associated with 480 μM protein) resulted in the formation of 28.7 ± 7.2 pmol/mg of protein intracellular S-nitrosothiol that increased to 73.0 ± 4.2 pmol/mg of protein in the presence of l-cystine (200 μM). These data indicate that l-cystine is also able to contribute to the transmembrane transport of protein-bound S-nitrosothiols.

Mechanisms of S-nitrosothiol Uptake. The formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol either derives from direct uptake of extracellular S-nitrosothiol or the transmembrane diffusion or transport of an S-nitrosothiol-derived nitrosating agent. It has been demonstrated that l-CysNO inhibited the uptake of l-leucine and that l-leucine reduced l-CysNO-mediated effects, suggesting that l-CysNO is a ligand for the L-AT (12). Therefore we investigated the involvement of this pathway in l-cystine-mediated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation. As shown in table 1, both BCH, an L-AT inhibitor, and l-leucine, but not d-leucine, had an inhibitory effect on the formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol, suggesting that a major pathway of S-nitrosothiol uptake occurs through this transporter.

It has been suggested that cysteine can increase the efficiency of NO release from GSNO (9). NO, or nitrosating agents formed from NO autooxidation, may diffuse into the cell to nitrosate thiols. Our previous data indicate that at high cellular NO formation rates that occur after activation of RAW 264.7 cells with lipopolysaccharide, only 17 pmol/mg of protein of S-nitrosothiol was observed (22), much lower than the levels observed here. To test whether NO release from S-nitrosothiol was a required step in the formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol, GSNO/l-cystine was incubated with cells in the presence of the NO scavenger, oxyMb (100 μM). As shown in Table 1, no inhibition of intracellular S-nitrosothiol was observed in the presence of this agent. To examine whether NO per se can generate the levels of S-nitrosothiol observed in this system, we incubated the cells with spermine NONOate (500 μM) in the presence and absence of l-cystine (200 μM) (Table 2). In both cases, the levels of intracellular S-nitrosothiol was small (≤50 pmol/mg of protein). Incubation of spermine NONOate in the presence of l-cysteine (200 μM) increased intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, which is likely caused by l-CysNO formation in the extracellular space from the autooxidation of NO, and subsequent transport into the cell.

Table 2. Intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation after incubation of RAW 264.7 cells with spermine NONOate.

| S-nitrosothiol content, pmol/mg of protein | |

|---|---|

| HBSS | 46.2 ± 2.5 |

| Medium | 29.4 ± 2.3 |

| HBSS + l-cystine | 51.2 ± 3.2 |

| HBSS + l-cysteine | 487.8 ± 56.0 |

RAW 264.7 cells were treated with spermine NONOate (500 μM) for 60 min in HBSS, FBS-free medium, or HBSS supplemented with l-cystine or l-cysteine (200 μM). The cells were washed and lysed. The S-nitrosothiol content in the cell lysate was measured by chemiluminescence. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3).

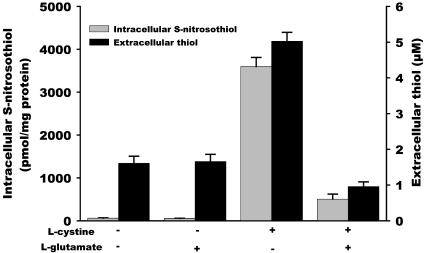

l-cystine Reduction by Cells. Because l-cystine does not react with GSNO to form l-CysNO, it is possible that l-cystine is reduced to l-cysteine, followed by transnitrosation to form l-CysNO. In the absence of cells, no thiol formation was detected by a DTNB assay when l-cystine was incubated in HBSS, and no S-nitrosothiol decay was observed when GSNO was incubated with l-cystine (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 3, ≈5 μM of thiols were detected when l-cystine (200 μM) was incubated with cells in HBSS, suggesting that l-cystine can be reduced by a cell-dependent process. The uptake of extracellular l-cystine has been shown to be accompanied by the export of l-glutamate via the amino acid transport system x–c (23–25). Inside the cell, l-cystine is converted very rapidly into l-cysteine (24), a part of which is released back into the extracellular space (23, 26, 27). It has been reported that the uptake of l-cystine can be inhibited by the presence of l-glutamate. As shown in Fig. 3, the addition of l-glutamate (3 mM) resulted in the decrease in l-cystine-mediated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, as well as the generation of extracellular thiol, suggesting that l-cystine uptake by amino acid transporter x–c is involved in the reduction of l-cystine and subsequent intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation.

Fig. 3.

The effect of l-glutamate on the formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol and extracellular thiol. S-nitrosothiol formation (gray bars): RAW 264.7 cells were treated with GSNO (500 μM) for 60 min in the absence or presence of l-cystine (200 μM) and l-glutamate (3 mM). The S-nitrosothiol content in the cell lysate was measured by chemiluminescence. Thiol formation (black bars): RAW 264.7 cells were incubated in HBSS for 60 min in the absence and presence of l-cystine and l-glutamate. The thiol level in the HBSS was detected by a DTNB assay. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Discussion

Previous studies have suggested mechanisms by which S-nitrosothiol can be taken up into cells (1–3, 12). However, direct measurements of S-nitrosothiol uptake are lacking. In this study we demonstrate that l-cystine, a component in culture medium, can facilitate the transport of the nitroso functional group of an S-nitrosothiol across the cell membrane by the sequential action of amino acid transport systems x–c and L.

L-AT is unique because of its Na+ independence and specificity toward neutral amino acids (28, 29). It is ubiquitous and is essential in cellular nutrition and transcellular transport of neutral amino acids. Various subtypes with different substrate specificities and transport properties have been described for system L (30–34). For example, LAT1 prefers neutral amino acid with branched or aromatic side chains (31), whereas LAT2 has a broad substrate specificity toward all the l-isomers of neutral amino acids, including l-cysteine (32, 33). It has been reported that L-AT can transport modified forms of cysteine such as the methylmercury–cysteine complex (35) and CysNO (12). In this study we show that both BCH and l-leucine inhibit intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, suggesting the involvement of L-AT in our system. L-AT has variable chiral specificity toward different amino acids. For LAT2, it was reported that l-[14C]leucine uptake was inhibited by glycine and l-isomers of the neutral amino acids; is partially inhibited by d-serine, d-asparagine, and d-cysteine; and is not inhibited by d-leucine (32). Our data agree with this in that d-leucine has little influence on l-cystine-mediated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, and d-cysteine has less effect than l-cysteine. l-homocysteine uptake has been shown to occur by those systems that transport l-cysteine, including system L and ASC in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (36). We found that addition of d/l-homocysteine to HBSS enhances GSNO-stimulated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation, suggesting that S-nitrosated homocysteine can also be transported into the cell through similar mechanisms as l-CysNO. l-cysteinyl-glycine, a dipeptide, is not a substrate for the amino acid transporter, and addition of l-cysteinyl-glycine had little effect on intracellular S-nitrosothiol concentration during incubation with GSNO. Our data strongly invoke the L-AT system as the major route of S-nitrosothiol transmembrane transport.

System x–c is responsible for the transport of l-cystine and l-glutamate across the cell membrane. The uptake of extracellular l-cystine has been shown to be accompanied by the export of l-glutamate and can be inhibited by the presence of l-glutamate in the extracellular space (24, 25, 27). l-cystine after uptake into cells is rapidly reduced to l-cysteine (24, 27), which is used for GSH and protein synthesis. A considerable part of l-cysteine is exported to the extracellular space by neutral amino acid transport systems (26, 27) and can react with GSNO to form CysNO. We observed that l-glutamate inhibited l-cystine-mediated formation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol as well as the generation of extracellular thiol, suggesting that l-cystine uptake by system x–c is involved in the reduction of l-cystine. The extracellular thiol level observed after 60 min of incubation with l-cystine (200 μM) is only ≈5 μM, much less than the l-cysteine required (≈100 μM) to give a similar intracellular S-nitrosothiol level (compare Figs. 2 and 3). The reason for that may be that l-cysteine is a competitive inhibitor for l-CysNO uptake by L-AT and that l-CysNO uptake is therefore enhanced in the presence of low steady-state levels of l-cysteine.

l-cystine-mediated intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation strongly depended on the S-nitrosothiol used. The effect of GSNO has already been described in detail. l-CysNO results in a large amount of intracellular S-nitrosothiol formation even in the absence of added l-cystine, which agrees with the hypothesis that l-CysNO is a species that is directly transported. In the case of SNAP, however, the effect of added l-cystine was much less pronounced. It is not clear why S-nitrosothiol uptake does not occur in this case, but it is possible that SNAP is inhibiting one of the amino acid transport systems.

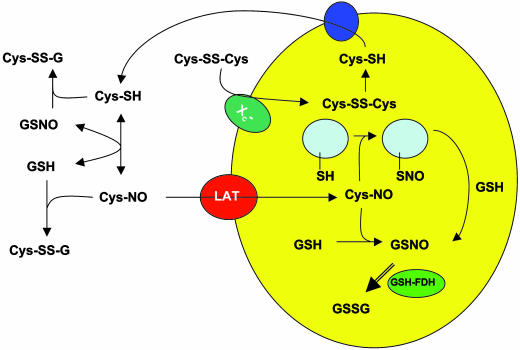

Our current hypothesis regarding the mechanism of l-cystine-mediated S-nitrosothiol uptake into RAW 264.7 macrophages is illustrated in Scheme 1. Our data suggest that l-cystine is reduced into l-cysteine after it is taken up into the cell via the system x–c transporter. l-cysteine thus formed can be exported into the extracellular space, and the transnitrosation reaction between GSNO and l-cysteine forms l-CysNO. Specific S-nitrosothiols (l-CysNO and l-homocysNO) can be taken up into cells via the L-AT. Once taken up into the cell, the CysNO will undergo transnitrosation reactions with cellular thiol groups to form GSNO and S-nitrosated proteins. Additional reactions of CysNO are possible, such as those with heme groups and other metal centers. GSNO is likely metabolized by GSH-formaldehyde dehydrogenase/NADH (37, 38) and perhaps other systems. The known reactions between thiols and S-nitrosothiols may also contribute to the loss of extracellular S-nitrosothiol.

Scheme 1.

A model for l-cystine-mediated S-nitrosothiol uptake.

We recently reported that induction of inducible NO synthase in RAW 264.7 cells results in the formation of low pmol/mg of protein levels of intracellular S-nitrosothiols (22). In the current study, we show that the intracellular level of S-nitrosothiol can be elevated to the low nmol/mg of protein range by incubating the cells with GSNO in either full medium or in l-cystine containing HBSS. This comparison, together with the fact that spermine NONOate failed to generate the level of intracellular S-nitrosothiol observed with GSNO/l-cystine and the observation that oxyMb, a potent NO scavenger, has no effect on intracellular S-nitrosothiol levels, clearly indicate that the nitroso group of GSNO is being transported into cells without reduction to NO. This raises a crucially important issue concerning the use of S-nitrosothiols as NO mimetics in cellular systems. There is a plethora of studies that use S-nitrosothiols (usually GSNO, SNAP, and CysNO) as NO donors. However, the biochemical changes that occur after exposure of cells to S-nitrosothiol, with respect to thiol chemistry, are distinctly different from those observed with NO and do not depend on the release of NO from S-nitrosothiol. Clearly the cellular events that are triggered or modulated by S-nitrosothiol exposure should not be automatically attributable to NO formation. S-nitrosothiols may mimic many of the downstream effects of NO but through potentially disparate intracellular mechanisms.

Figs. 1D and 2 illustrate that the intracellular level of S-nitrosothiol can be controlled somewhat by modulation of both time of incubation and the concentration of l-cystine/l-cystine. This has the potential to be an extremely useful approach to titrating the S-nitrosothiol “tone” in a cell as a way to examine the concentration dependence of intracellular S-nitrosothiol levels on cellular pathways. By using such approaches, it should be possible to delineate specific S-nitrosothiol-dependent pathways and examine the similarities and differences between S-nitrosothiol and NO-mediated signaling.

In summary, the major conclusions of this study are (i) l-CysNO can be taken up into cells by L-AT, (ii) uptake of other S-nitrosothiols in culture medium is driven by the cell-mediated reduction of l-cystine via amino acid transport system x–c, (iii) S-nitrosothiols are not NO donors and alter the intracellular biochemistry in ways distinct from NO, and (iv) the modulation of intracellular S-nitrosothiol levels will be useful to examine the concentration dependence of S-nitrosothiol-mediated pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM55792 and American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship 0310032Z.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: GSNO, S-nitrosoglutathione; SNAP, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine; CysNO, S-nitrosocysteine; GSH, glutathione; L-AT, amino acid transporter system L; BCH, 2-aminobicyclo[2.2.1]-heptane-2-carboxylate; DTPA, diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid; DTNB, 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid); spermine NONOate, (Z)-1-[N-(3-ammoniopropyl)-N-[4-(3-aminopropylammonio)butyl]-amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate; oxyMb, oxymyoglobin.

References

- 1.Ramachandran, N., Root, P., Jiang, X.-M., Hogg, P. J. & Mutus, B. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9539–9544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zai, A., Rudd, M. A., Scribner, A. W. & Loscalzo, J. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Groote, M. A., Granger, D., Xu, Y., Campbell, G., Prince, R. & Fang, F. C. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 6399–6403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogg, N., Singh, R. J., Konorev, E., Joseph, J. & Kalyanaraman, B. (1997) Biochem. J. 323, 477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pawloski, J. R., Hess, D. T. & Stamler, J. S. (2001) Nature 409, 622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satoh, S., Kimura, T., Toda, M., Miyazaki, H., Ono, S., Narita, H., Murayama, T. & Nomura, Y. (1996) J. Cell. Physiol. 169, 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoh, S., Kimura, T., Toda, M., Maekawa, M., Ono, S., Narita, H., Miyazaki, H., Murayama, T. & Nomura, Y. (1997) J. Neurochem. 69, 2197–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallis, R. J. & Thomas, J. A. (2000) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 383, 60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padgett, C. M. & Whorton, A. R. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 272, C99–C108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsikas, D., Sandmann, J., Rossa, S., Gutzki, F. M. & Frölich, J. C. (1999) Anal. Biochem. 270, 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemoto, T., Horie, S., Okuma, Y., Nonami, Y. & Murayama, T. (2001) Neurosci. Lett. 311, 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nemoto, T., Shimma, N., Horie, S., Saito, T., Okuma, Y., Nomura, Y. & Murayama, T. (2003) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 458, 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, S. & Whorton, A. R. (2003) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 410, 269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng, H., Spencer, N. Y. & Hogg, N. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. 281, H432–H439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart, T. W. (1985) Tetrahedron Lett. 26, 2013–2026. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field, L., Dilts, R. V., Ravichandran, R., Lanhert, P. G. & Carnahan, P. G. (1978) J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 249–250.

- 17.Goldstein, S. & Czapski, G. (1996) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 3419–3425. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook, J. A., Kim, S. Y., Teague, D., Krishna, M. C., Pacelli, R., Mitchell, J. B., Vodovotz, Nims, R. W., Christodoulou, D., Miles, A. M., et al. (1996) Anal. Biochem. 238, 150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samouilov, A. & Zweier, J. L. (1998) Anal. Biochem. 258, 322–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rassaf, T., Bryan, N. S., Kelm, M. & Feelisch, M. (2002) Free Radical Biol. Med. 33, 1590–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, B. K., Vivas, E. X., Reiter, C. D. & Gladwin, M. T. (2003) Free Radical Res. 37, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang, Y. & Hogg, N. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Bannai, S. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 2256–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bannai, S. & Kitamura, E. (1980) J. Biol. Chem. 255, 2372–2376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makowske, M. & Christensen, H. N. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 5663–5670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bannai, S. & Ishii, T. (1982) J. Cell Physiol. 122, 272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bannai, S. & Ishii, T. (1988) J. Cell Physiol. 137, 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christensen, H. N. (1999) Physiol. Rev. 70, 43–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mann, G. E., Yudilevich, D. L. & Sobrevia, L. (2003) Physiol. Rev. 83, 183–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prasad, P. D., Wang, H., Huang, W., Kekuda, R., Rajan, D. P., Leibach, F. H. & Ganapathy, V. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 255, 283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanai, Y., Segawa, H., Miyamoto, K., Uschino, H., Takeda, E. & Endou, H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 23629–23632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segawa, H., Fukasawa, Y., Miyamoto, K., Takeda, E., Endou, H. & Kanai, Y. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19745–19751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pineda, M., Fernandez, E., Torrents, D., Estevez, R., Lopez, C., Camps, M., Lloberas, J., Zorzano, A. & Palacin, M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19738–19744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Babu, E., Kanai, Y., Chairoungdua, A., Kim, D. K., Iribe, Y., Tangtrongsup, S., Jutabha, P., Li, Y., Ahmed, M., Sakamoto, S., et al. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43838–43845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerper, L. E., Ballatori, N. & Clarkson, T. W. (1992) Am. J. Physiol. 262, R761–R765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ewadh, M. J. A., Tudball, N. & Rose, F. A. (1990) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1054, 263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen, D. E., Belka, G. K. & Du Bois, G. C. (1998) Biochem. J. 331, 659–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu, L., Hausladen, A., Zeng, M., Que, L., Heitman, J. & Stamler, J. S. (2001) Nature 410, 490–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]