Abstract

Endometrioma is one of the most frequent adnexal masses in the premenopausal population, but the recommended treatment is still a subject of debate. Medical therapy is inefficient and can not be recommended in the management of ovarian endometriomas. The general consensus is that ovarian endometriomas larger than 4 cm should be removed, both to reduce pain and to improve spontaneous conception rates. The removal of ovarian endometriomas can be difficult, as the capsule is often densely adherent. While the surgical treatment of choice is surgical laparoscopy, for conservative treatment, the preferred method is modified combined cystectomy. Cystectomy can be destructive for the ovary, whereas ablation may be incomplete, with a greater risk of recurrence. To the best of our knowledge, the modified combined technique seems to be more efficient in the treatment of endometriomas.

Keywords: Endometrioma, laparoscopy, cystectomy, combined technique

Introduction

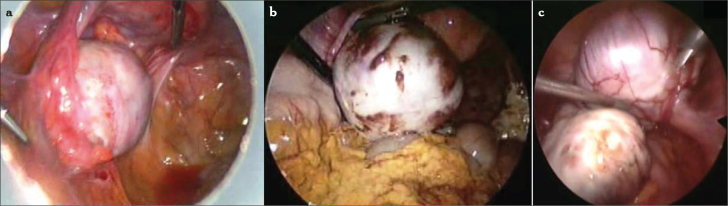

The ovaries are a common site for endometriosis. Endometrioma is one of the most frequent adnexal masses in the premenopausal population (Figure 1). Although endometrioma is the most frequent ovarian mass that is encountered by gynecologists, there are still controversies on its pathogenesis, risk of malignant transformation, modalities of treatment, and effect on fertility.

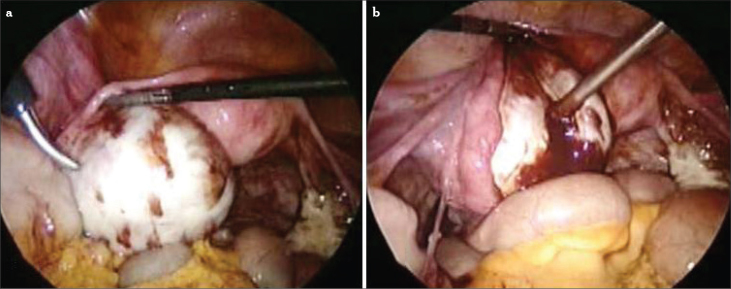

Figure 1.

a–c. Ovarian endometriomas. Small endometrioma (a), large endometrioma and ovarian implants of endometriosis (b), bilateral endometrioma, kissing ovaries (c)

Laparoscopy is extremely useful in the diagnosis and treatment of endometriomas. The purpose of this chapter is to highlight the steps and tips of the surgical removal of endometriomas by combined approach.

Diagnosis

The definitive diagnosis of the endometriosis is made by visualizing lesions during surgery and obtaining histological confirmation. Transvaginal sonography has been found to be a good test for assessing the severity of pelvic endometriosis. The morphology of ovarian endometriomas in the ultrasonography examination reveals a round, homogenous, hypoechoic cyst with or without internal septa and with poor vascularization of the cyst wall. Diffuse low-level internal echoes occur in 95% of endometriomas. Endometriomas are usually adherent to the pelvic side wall. This immobility is a useful diagnostic indicator.

Levels of serum and other concentrations of hormones may eventually be categorized, such that they provide prognostic and/or treatment capabilities for patients with endometriomas. Lower anti-mullerian hormone serum levels and an association with the severity were found in women with endometriosis. This information might be useful in patients, especially those with severe endometriosis undergoing controlled ovarian stimulation (1). Putative serum markers (monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, migration inhibitory factor, leptin, and CA-125) improved their diagnostic capability to 73% of patients, with 94% overall accuracy (2).

A new marker, HE4 (human epididymis secretory protein-4), could be used in the differential diagnosis of endometriosis cyst. Human epididymal secretory protein E4 is a new promising biomarker for ovarian cancer. The combination of HE4 and CA 125 assay could discriminate ovarian endometriosis cysts from malignant ovarian tumors effectively (3). The advantage of HE4 over CA125 is mainly in the detection of borderline ovarian tumors and early-stage epithelial ovarian and tubal cancers (4). A normal HE4 value in this situation would imply the differential diagnosis of a benign endometrioma rather than ovarian cancer, and this patient could therefore be operated on laparoscopically by a gynecologist. Both markers showed similar diagnostic performance in the detection of epithelial ovarian cancer at clinically defined thresholds (CA125 35 U/mL; HE4 70 pM), but HE4 was not elevated in endometriosis (5). An analysis of serum HE4 concentrations together with a tumor marker, CA125, in serum samples of women diagnosed with various types of endometriosis, endometrial cancer, or ovarian cancer and in samples from healthy controls has been released (6). Based on this study, the mean serum concentration of HE4 was significantly higher in serum samples of patients with both endometrial (99.2 pM, p<0.001) and ovarian (1125.4 pM, p<0.001) cancer but not with ovarian endometriomas (46.0 pM) or other types of endometriosis (45.5 pM) as compared with healthy controls (40.5 pM). Serum CA125 concentrations were elevated in patients with ovarian cancer, advanced endometriosis with peritoneal or deep lesions, or ovarian endometriomas. Taken together, it can be postulated that measuring both HE4 and CA125 serum concentrations increases the accuracy of ovarian cancer diagnosis and provides valuable information to discriminate ovarian tumors from ovarian endometriotic cysts. Serum HE4 concentration is a valuable marker to better distinguish patients with ovarian malignancies from those suffering from benign ovarian endometriotic cysts.

However, the different diagnostic modalities that have been discussed demonstrate that there are many candidates but no good non-invasive tests to replace laparoscopic visualization for diagnosis and staging, preferably with histologic confirmation. Laparoscopy has the advantage of allowing simultaneous diagnosis, staging, and treatment of ovarian endometriosis.

Laparoscopy for Endometriomas

Indications for Surgery

Five specific complications may be associated with the non-surgical approach: 1) risk of causing rupture of the endometrioma and/or the development of a pelvic abscess, 2) missing an occult early-stage malignancy, 3) difficulties during oocyte retrieval, 4) follicular fluid contamination with endometrioma content, and 5) progression of endometriosis (7).

Endometriosis is shown to increase the risk of certain subtypes of ovarian cancer, such as endometrioid and clear-cell carcinomas (8). There are data indicating that 40% of endometrioid ovarian carcinomas and 50% of clear-cell ovarian carcinomas are associated with endometriosis. Both endometrioid and clear-cell carcinomas are thought to arise, at least partly, from endometriosis. Similar pathophysiological mechanisms may be involved in the progression of endometriosis, as well as in its transformation into ovarian neoplasia (9). Expectant management without a tissue diagnosis does not exclude the possibility of malignancy, particularly in older woman.

The recommended treatment is still a subject of debate. Management of endometrioma before in vitro fertilization (IVF) remains controversial. The clinical variables to be considered when deciding whether to perform surgery or not in women with endometriomas selected for IVF are listed in Table 1 (modified from reference 10). However, medical treatment for the endometrioma does not improve fertility. Surgical treatment is effective in the treatment of pain and fertility, particularly for women with more severe endometriosis. It improves pelvic pain and deep dyspareunia. Draining the endometrioma or partially resecting its wall is inadequate, because the endometrial tissue lining the cyst can remain functional and may cause the symptoms to recur. Cystectomy of ovarian endometriomas improves spontaneous pregnancy rates and reduces pain. In addition, it may improve the response to in vitro fertilization (IVF). It has been shown that laparoscopic cystectomy for ovarian endometriomas >4 cm in diameter improves fertility compared to drainage and coagulation (11). Drawbacks of surgery include postoperative adhesion formation and incomplete removal of the disease.

Table 1.

Surgical decision for the endometriomas before IVF treatment

| Favors surgery | Favors expectant management | |

|---|---|---|

| Previous interventions for endometriosis | None | ≥1 |

| Ovarian reserve | Intact | Damaged |

| Pain symptoms | Present | Absent |

| Location | Unilateral disease | Bilateral disease |

| Sonographic feature of malignancy | Present | Absent |

| Growth | Rapid growth | Stable |

IVF: in vitro fertilization

Laparoscopy has the advantage of allowing simultaneous diagnosis, staging, and treatment of ovarian endometriosis. The main surgical procedures for treatment of endometrioma include ultrasound-guided or laparoscopy-guided aspiration, laparoscopic surgery by means of cystectomy or fenestration and coagulation, radical-treatment ovariectomy or adnexectomy, and treatment by laparotomy (Table 2 (modified from reference 12)).

Table 2.

Surgical procedures for the endometriomas

Conservative treatment

|

Radical treatment

|

TUGA: Transvaginal Ultrasonography-Guided Aspiration

Surgical Technique

A general consensus is that ovarian endometriomas larger than 4 cm should be removed, both to reduce pain and to improve spontaneous conception rates. The presence of small endometriomas (2–4 cm) does not reduce the success of in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment (13). However, all decisions to operate a cyst beyond 3 or 4 cm are arbitrary, as there is no evidence to support one or the other (10). Surgeons should bear in mind that if all healthy growing follicles may be reached without damaging the endometrioma, a cyst over 4 or even 5 cm does not require surgery in asymptomatic patients; however, smaller cysts that hide growing follicles, especially when the ovary is fixed, may require intervention.

The goal of operative treatment of endometriosis is to remove all implants, resect adhesions, relieve pain, reduce the risk of recurrence and postoperative adhesions, and restore the involved organs to a normal anatomic and physiologic condition. This goal may be achieved by using various surgical instruments (scissors, harmonic scalpel, lasers…) and a variety of techniques (laparoscopy, laparotomy, combined endoscopy, and mini-laparotomy). But, to the best of our knowledge, endometriomas must be treated by laparoscopy. Laparoscopic cystectomy remains a first-line choice for the conservative treatment of endometriotic cysts.

Laparoscopy for endometrioma is performed through an intraumbilical incision and two or three lower abdominal incisions. Usually, 5-mm bipolar and unipolar scissors and graspers with suction-irrigation systems are enough to complete the surgical procedure. Irrigation is performed by lactated Ringer’s solution. Hemostasis is achieved with bipolar coagulation, laser ablation, or new commercially available hemostatic sealant agents.

The procedure begins with laparoscopic inspection of the pelvic anatomy and systemic mapping of the endometriotic lesions. Inspection of the pelvis should be carried out in a logical and systematic way. The liver and diaphragms are inspected to look for endometriotic implants or perihepatic adhesions. Inspect the utero-vesical fold, and lift the uterus forward into anteversion. Move the bowel out of the pouch of Douglas. Fluid in the pouch should be aspirated to ensure that implants are not missed. Inspect both tubes and ovaries. Deep, infiltrating endometriotic implants are often palpated and then visualized. This can be done with a blunt probe or graspers through the second port. Laparoscopy for endometrioma, like surgery for adnexal masses, is started with peritoneal washing for cytology and inspection of the pelvis and intra-abdominal viscera for any type of lesion, like implants or adhesions.

After inspection of the intra-abdominal area and obtaining peritoneal washing, the first step of the surgery is mobilization of the ovaries. The utero-ovarian ligament is taken with a 5-mm atraumatic grasper. Lysis of the adhesions is performed with the use of sharp dissection to fully mobilize the ovaries. Adhesiolysis may be performed using hydrodissection, scissors, CO2 laser, or atraumatic forceps. Before cutting the handling tissue, it is important to mobilize and identify the relevant anatomical structures. Mechanical dissection with forceps and hydrodissection is not associated with any thermal effect; therefore, this technique should be preferred. The removal of ovarian endometriomas can be difficult, as the capsule is often densely adherent. Large endometriomas are typically adherent to the back of the uterus or broad ligament or ovarian fossa. Adhesiolysis often results in opening of the cyst and leaking of the ‘chocolate’ content (Figure 2). In most cases, the cyst is ruptured during mobilization of the ovary, which requires the liquid to be aspirated immediately to prevent pelvic contamination.

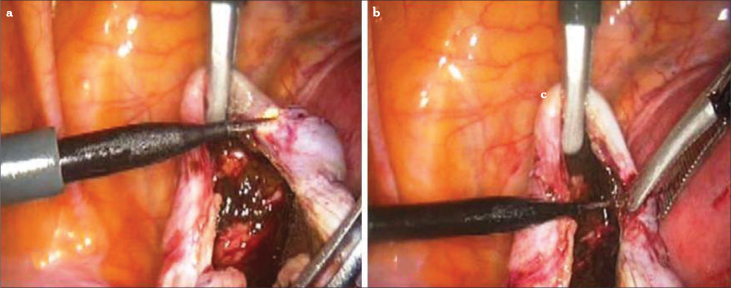

Figure 2.

a, b. Laparoscopic aspiration of the endometrioma cyst. Hemosiderin staining on the ovary clued about endometrioma (a), aspiration (b)

Meticulous suction and irrigation are performed to remove this spillage. The perception is that copious irrigation and suction of released endometrioma content reduce adhesion formation; however, there is a lack of clinical literature to evaluate this supposition. An interesting animal study has shown human endometrioma fluid exposure in the peritoneal cavity of rabbits is not associated with adhesion formation. In this study, instillation of endometrioma fluid, followed by copious saline lavage, is strongly associated with adhesion formation (14). A possible explanation for the higher mean clinical adhesion scores in the lavage group is that the saline lavage itself served to spread the endometrioma fluid more effectively in the abdominal cavity, thereby increasing the distribution of tissue contact and potential for adhesions compared to local spillage. Another possibility is that the process of lavage mechanically irritates the peritoneal cavity and thereby causes adhesions by local tissue damage by the suction instrument. There is some evidence that peritoneal irrigation with lactated Ringer’s solution is superior to irrigation with normal saline and that lactated Ringer’s solution irrigation is protective against adhesions in both rat and rabbit models.

After freeing the ovary, an incision is made to the ovarian cortex with either scissors or a monopolar hook device. CO2 laser can be used for this purpose. The incision should be in the free surface of the ovary and, when it is possible, on the anti-mesenteric surface and the most distant possible port from the fimbria. Then, the cyst cavity is repeatedly irrigated with a suction-irrigation tube. After cleansing the cyst content, the laparoscope is proceeded to inspect inside of the cyst wall to rule out suspicious malignant lesions, such as vegetations, papillary masses, or solid projections.

It has been known that surgical resection of endometriomas, either by laparotomy or laparoscopy, is equally effective in eradicating endometriosis; however, if resection of endometriomas is not sufficiently radical, the risk of recurrence is high.

Fenestration and Ablation (Fulguration or Vaporization)

Endometrial implants or endometriomas less than 2 cm in diameter are coagulated, laser-ablated, or excised using scissors, biopsy forceps, laser, or electrodes. For successful eradications, all visible lesions and scars must be removed from the ovarian surface. A major problem with laparoscopic cyst drainage is a high risk of recurrence of about 80% to 100% (15). Nowadays, it is accepted that simple aspiration by laparoscopy should not be used to treat endometrioma.

An alternative method is to perform laparoscopic cyst fenestration and ablation of the cyst capsule. Any co-existing endometriosis should also be treated. This has been shown to significantly improve pelvic pain, with a very high patient satisfaction rating. Fenestration and ablation or laser vaporization of endometriomas without excision of the pseudocapsule is associated with a significantly increased risk of cyst recurrence.

Alborzi et al. (16) found that laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy was associated with better outcomes in pregnancy rates and relief of pain than fenestration and coagulation of endometriomas and had a lower rate of reoperation, even in larger cysts. As a result, they recommend that cystectomy of endometriomas is a better option than fenestration and coagulation, especially in patients with infertility and pelvic pain. Laparoscopic stripping of ovarian endometriomas as an intervention to improve fertility is a widespread clinical practice, not only to improve natural fertility but also to improve IVF outcomes. This surgical strategy is used, because older studies suggested that patients with ovarian endometriosis had poorer IVF outcomes than women with other infertility causes, and some data suggest that spontaneous fecundity may improve after laparoscopic cystectomy.

In our practice, we usually do not prefer fenestration, aspiration, and ablation. Laparoscopic cystectomy remains the first-line choice for conservative treatment of endometriotic cysts. But, as it has been told: there is no disease, there is a patient. The treatment should be individualized, based on operative findings and on date conditions.

Total Cystectomy

The surgical technique of ovarian cyst excision by laparoscopy differs from traditional surgery performed by laparotomy. In laparoscopy, most surgeons perform a stripping technique, in which two atraumatic grasping forceps are used to pull the cyst wall and the normal ovarian parenchyma in opposite directions, thus developing the cleavage plane. After excision of the cyst wall, hemostasis is achieved by using bipolar forceps or CO2 laser. The residual ovarian tissue is not sutured, and the ovarian edges are left to heal by secondary intention. In contrast, in laparotomy, the cleavage plane is developed by using microsurgical techniques and instruments.

After identifying the correct plane (Figure 3), bimanual opposite traction with two -mm grasping forceps (atraumatic one for the handling of the ovarian cortex) is performed to strip the cyst wall from the inner surface of the ovarian tissue (Figure 4). This step is usually difficult compared to functional cyst stripping. When necessary, scissors, bipolar, or laser can be utilized for the stripping step. Another method involves hydrodissection of the plane between the cyst wall and the ovarian stroma (17). The cyst wall is removed by grasping its base with laparoscopic forceps and peeling it from the ovarian stroma. If stripping of the capsule is incomplete or difficult to accomplish, the residual part must be eradicated by electrocoagulation or laser application. During the stripping procedure, meticulous and highly selective coagulation is required.

Figure 3.

a, b. A needle electrode is used to identify and create a correct cleavage plane between the cyst wall and ovarian cortex

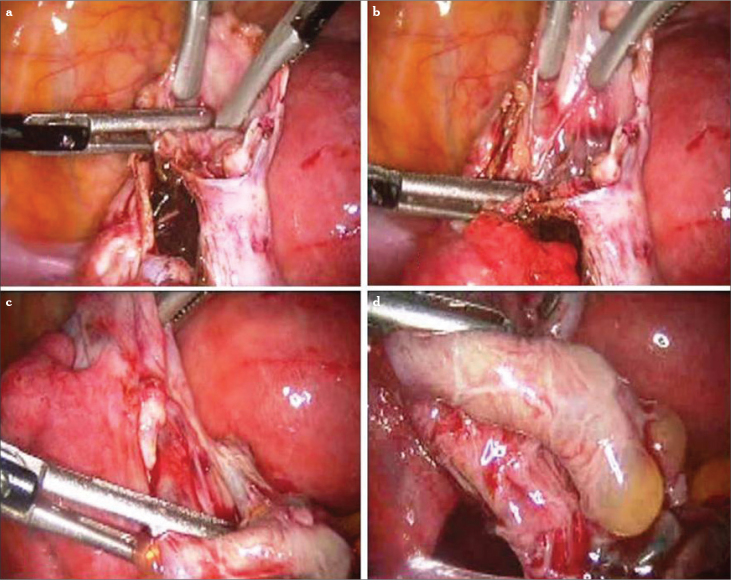

Figure 4.

a–d. Cyst wall grasped with either traumatic or atraumatic forceps and ovarian cortex handled all the time with the atraumatic one. Countertraction for the stripping (a–c). Total cystectomy (d)

After removing the cyst wall from the ovary, the bed of the cyst is inspected carefully to visualize the bleeders and to coagulate them with bipolar coagulation (Figure 5), holding the ovary with an atraumatic forceps and visualizing each bleeding site by dripping saline on the base of the cyst. After total stripping, in some cases, annoying bleeding may occur in the bed of the cyst. It should be noted that prompt coagulation can cause diminished ovarian reserve. Especially in this area, monopolar coagulation should be avoided. Careful inspection with a suction and irrigation tube can show the exact point of the bleeders. Only this area should be grasped and coagulated in a low-setting voltage with bipolar forceps.

Figure 5.

a–d. After total stripping, sometimes meticulous hemostasis is needed. Prompt coagulation can cause diminished ovarian reserve

Canis et al. (18) and Marconi et al. (19) found no effect on ovarian response in IVF after cystectomy. But, there are many other trials that indicate that cystectomy has a bad influence in the subsequent ovarian responsiveness. As Hart et al. concluded, excisional surgery of endometriomas results in a more favorable outcome than drainage and ablation in terms of recurrence, pain symptoms, subsequent spontaneous pregnancy in previously subfertile women, and ovarian response to stimulation (20). But, Muzii et al. (21) showed that recognizable ovarian tissue was inadvertently excised together with the endometriotic cyst wall in most cases during stripping for endometrioma excision. Close to the ovarian hilus, ovarian tissue that was removed along the endometrioma wall contained primordial, primary, and secondary follicles in 69% of cases. Away from the hilus, no follicles or only primordial follicles were found in 60% of specimens. There is obviously an absence of a clear plane of cleavage close to the ovarian hilus. However, it has been published by the same group that the ovarian tissue adjacent to the endometrioma wall differs morphologically from normal ovarian tissue; it never shows the follicular pattern that is observed in normal ovaries (22).

In experienced hands, laparoscopic stripping of endometriomas appears to be a technique that does not significantly damage the ovarian tissue. On the contrary, several studies have demonstrated a reduced follicular response after total cystectomy. Nargund et al. showed that, in cycles with ovulation induction after cystectomy, revealed less follicular count in the ovary that underwent surgical excision (23). Ho et al. concluded that surgery for ovarian endometriomas induces a poor ovarian response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (24). Laparoscopic cystectomy has been questioned with respect to damage to the operated ovary.

Because of these negative effects, a new technique is required to remove endometrioma without damage to the ovarian tissue with a low subsequent recurrence rate. A modified combined technique for the removal of endometrioma seems to achieve this issue.

Modified Combined Technique vs Total Cystectomy

Preservation of the vascular blood supply to the ovary is important. A proper blood supply is vital for the preservation of ovarian volume and antral follicular counts. Meticulous surgical techniques avoiding the compromise of ovarian blood supply and healthy ovarian tissue are mandatory, but still, it can be postulated that there are two main risks associated with the surgical treatment of endometriomas: the risk of excessive surgery (removal or destruction of normal ovarian cortex together with the endometrioma) and the risk of incomplete surgery (with subsequent early recurrence of endometriomas) (25). To overcome these problems, Donnez et al. described a new mixed technique for the laparoscopic management of endometriomas (26). They defined their technique as follows. The endometrial cyst is opened and washed out with irrigation fluid. After identifying the plane of cleavage between the cyst wall and ovarian tissue by applying opposite bimanual traction and counter-traction with two grasping forceps, providing strong but nontraumatic force, the inner lining of the cyst is stripped from the normal ovarian tissue. If the excision provokes bleeding or if the plane of cleavage is not clearly visible, the cystectomy is stopped because of the risk of removing normal ovarian tissue containing primordial, primary, and secondary follicles along with the endometrioma. They claimed that when approaching the hilus, where the ovarian tissue is more functional and the plane of cleavage is less visible, resection of the dissected tissue (partial cystectomy) is performed. Then, after this first step (partial cystectomy), CO2 laser is used to vaporize the remaining 10%–20% of the endometrioma close to the hilus. They do not close the ovary after the operation.

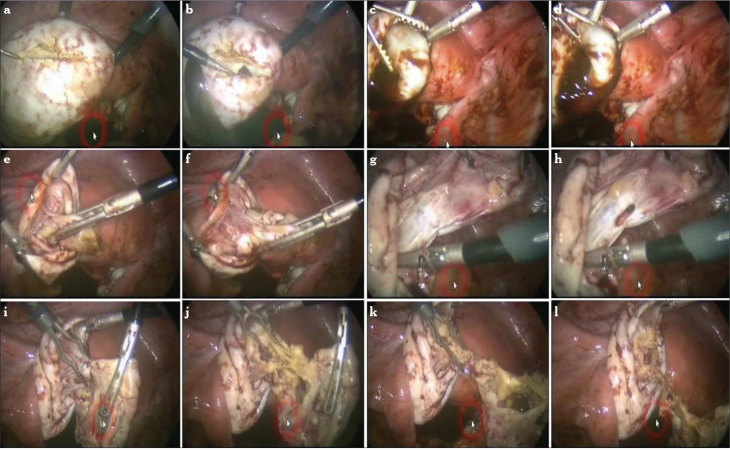

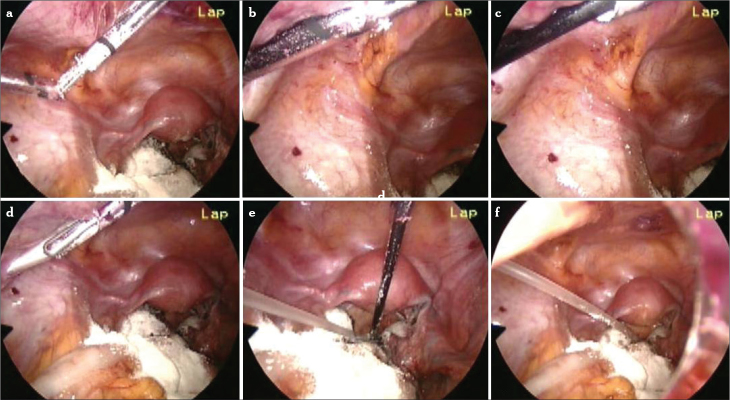

Based on these sights, we developed our modified combined technique (Figure 6). In this technique, after initial inspection and peritoneal cytology, obtained with washing of the peritoneal cavity, adhesiolysis is performed. The ovary is released from the attachments, and pelvic anatomical restoration is obtained. The endometrial cyst is opened with a fine-tip electrode with a low power setting (30 watts). The cyst content is irrigated and aspirated to prevent spillage into the pelvis. The true cleavage plane is found as described earlier.

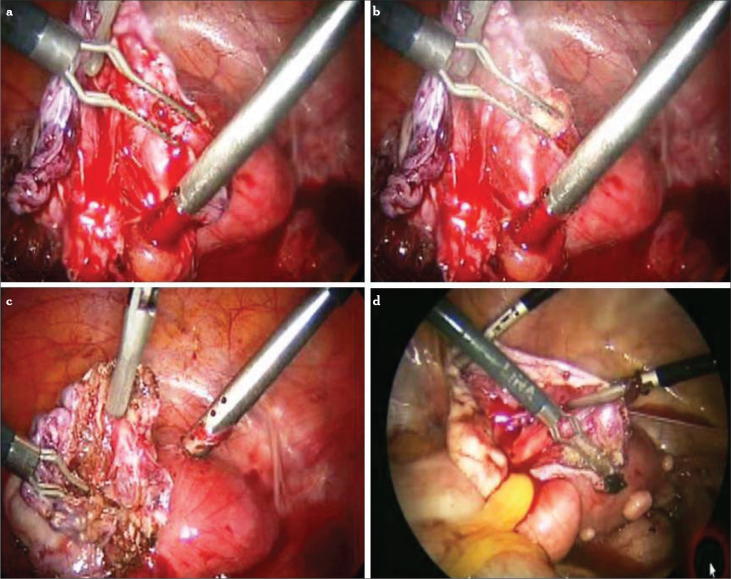

Figure 6.

a–l. Modified combined technique for the removal of endometrioma. Cleavage plane is revealed with a fine-tip needle electrode (a, b). Countertraction is accomplished to strip the cyst wall from the ovarian cortex (c–f). When the base of the cyst is reached, a white plane is seen (g). With more traction, the tissue usually starts to tear (h). Cyst wall is coagulated using bipolar forceps and cut from the base with scissors (i–l)

The cyst wall and the ovarian cortex are grasped, and gentle traction and countertraction are applied for the stripping of the cyst wall from its bed. The traction is ceased when reaching the hilus. This area looks pale due to fibrotic tissue. Forcing the traction can cause bleeding easily in this area. To avoid damage to the ovary, we do not proceed with stripping after this step. Till here, the stripping technique allows removal of 80%–90% of the cyst. Then, the cyst wall is coagulated with bipolar forceps (40 watts) around this area. In contrast to total cystectomy, coagulation of the cyst wall in the combined technique protects the ovarian tissue from heat damage. Then, the coagulated cyst wall is incised, and cystectomy is achieved. Care must be taken to cauterize all of the residual cyst wall to avoid recurrence. The coagulation of the cyst wall prevents small bleeding and protects patients from diminished ovarian reserve. At the end of the procedure, the ovary is not sutured. We know that stretching of the ovarian cortex does not seem to be associated with morphologic alterations. Electrosurgical coagulation of the remaining parenchyma after excision of the cyst wall may cause further damage to the ovarian tissue. However, when appropriate techniques are used, small vessels may be identified and coagulated with bipolar forceps that, under these circumstances, may limit thermal damage to less than 0.2 mm (27). But, there is still a small risk for heat injury. In the combined technique, even if the heat spreads, it still projects onto the capsule (Figure 7). This thermal spreading only prevents recurrence, as it does not proceed from the cyst wall to the ovarian cortex or hilus.

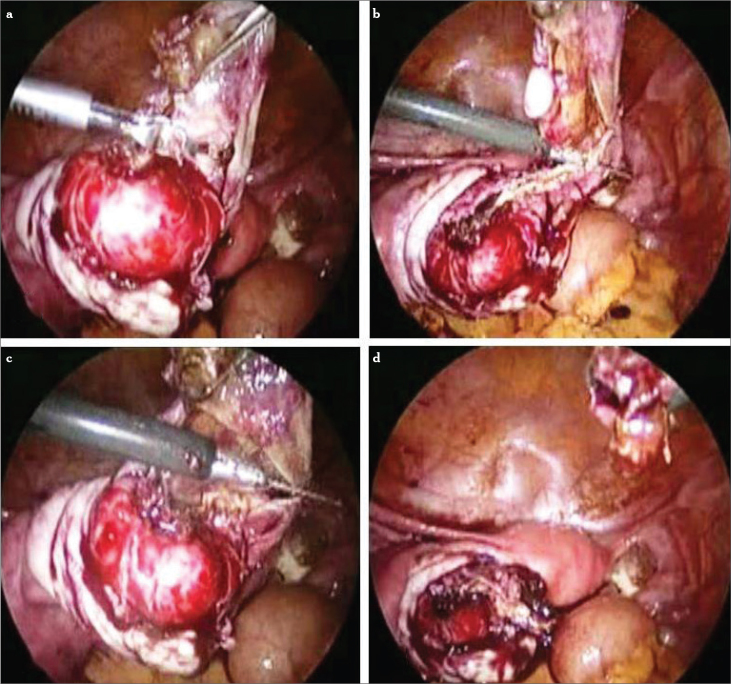

Figure 7.

a–d. The ovarian cortex is protected from the side effect of heat when coagulation is applied only to the base of the cyst wall in the modified combined technique

To reduce the probability of ovarian tissue damage, hemostatic agents can be used for the hemostasis of the cyst bed. Fibrin sealant is an excellent agent to use for sealing small bleeders. We generally use the PerClot system (Figure 8). This is a medical device composed of absorbable modified polymer (AMP) particles and delivery applicators. AMP particles are biocompatible and non-pyrogenic and derived from purified plant starch (SMI-Starch Medical Inc., San Jose, California, USA). Some products, like Tisseel, distributed in the United States by Baxter Healthcare Corp. (Glendale, California, USA); Crosseal (the American Red Cross, OMRIX biopharmaceuticals Ltd., Kiryat Ono, Israel); and FLOSEAL (Baxter’s BioScience- Glendale, California, USA) can be used.

Figure 8.

a–d. Hemostatic powders can be used to achieve adequate hemostasis

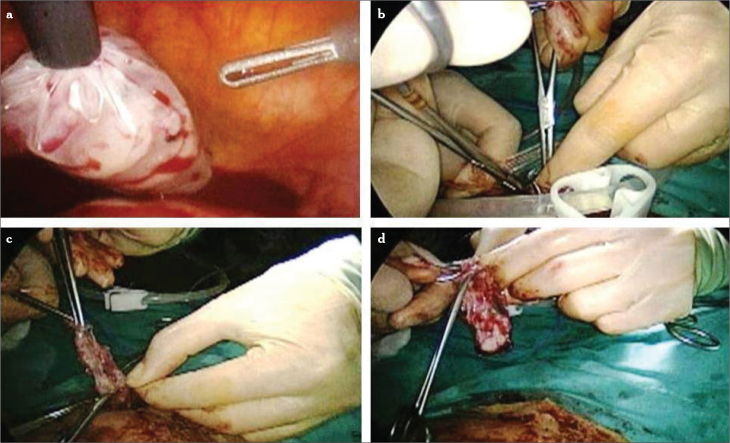

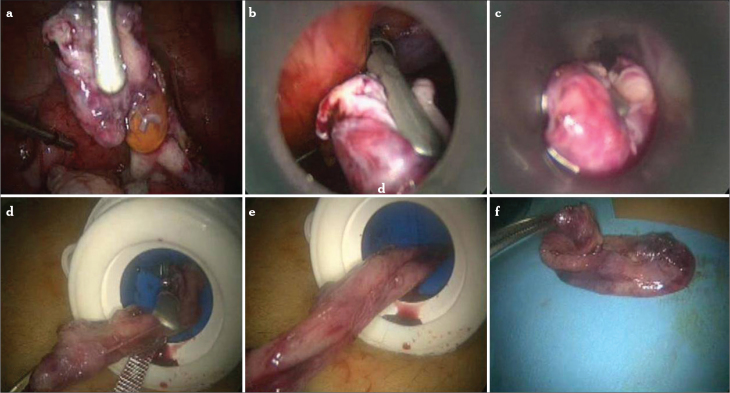

The endometriotic cyst wall is removed from a 5 mm trocar if it is small in size (Figure 9). The surgeon draws the tissue into the port sleeve using gentle rotation and opens the flapper valve as the specimen is withdrawn. If there is any suspicion for a malignancy or a great mass that can not be extracted from small-sized trocar, then an endobag can be used (Figure 10). Endobags usually need a 10 mm or 12 mm trocar. There are two options: either to replace one of the ancillary 5 mm ports to the 10 mm trocar or to use a 5 mm telescope. The 5 mm scope is introduced from one of the pelvic ancillary trocars, and the endobag is introduced to the abdomen from the umbilical port. For slightly larger benign specimens, the 10–12 mm umbilical sleeve is often adequate for tissue removal. If the surgeon is not using an operative (10 mm) laparoscope, a 5 mm laparoscope may be introduced through one of the lateral ports, and the tissue is recovered with a grasping forceps under direct vision using either of the techniques above. If there is no 5 mm scope under the hands, then our technique can be applied for tissue retrieval (Figure 11). A traumatic grasper is introduced through the ancillary port, and the scope proceeds from the umbilical port. The grasped tissue follows the tip of the scope, and with gradual pulling back of the scope, the tissue is proceeded to the lumen of the umbilical port. Whenever the scope is taken back from the port, the grasper is promoted in the umbilical port, and the tissue is taken out. Once removed from the abdominal cavity, the cyst has to be sent for histopathological examination.

Figure 9.

a–c. Cyst wall is taken out from the ancillary trocar

Figure 10.

a–d. An endobag can be used for removing the cyst from the abdomen

Figure 11.

a–f. A big mass can be introduced to the 10-mm scope’s trocar. Stripped endometrioma cyst wall is grasped (a). The grasped tissue is proceeded toward the scope, and gradually, the scope is pulled back (b, c). Then, the tissue is taken out from the main umbilical trocar (d, e). Removed endometriotic cyst mass (f)

Intra-abdominal adhesions lead to significant morbidity. Unfortunately, pelvic surgery for endometriosis has been associated with high rates of adhesion formation and reformation (29). After laparoscopic endometriosis surgery, the odds of adhesion formation range from 80% to 100% (30). The high incidence of adhesion formation after surgery for endometriosis underscores the importance of optimizing the surgical technique and the possible role of anti-adhesion drugs to potentially reduce adhesion formation. To reduce postoperative adhesion, we prefer to use adhesion barrier gels (Hyalobarrier Gel; The Nordic Group, Paris France) (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

a, b. Adhesion barrier gel can be applied to the field to prevent subsequent surgery-related adhesion formation

If there is a need for putting a drain in after the surgery, a 14–16 F rubber drain can be applied into the abdomen. A grasper with teeth is introduced from one ancillary trocar to the others. When the tip of the grasper reaches the outside through the second port, this trocar is taken out, and the tip of the end side of the drain is held with this grasper. Then, the grasper is pulled back to introduce the drain into the pouch of Douglas. This is an easy way to put a in rubber drain in any sort of laparoscopic surgery (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

a–f. When necessary, a 14–16 F rubber drain can be applied after cessation of the operation. A grasper with teeth is introduced from one ancillary trocar to the others (a). When the tip of the grasper reaches the outside, this trocar is taken out, and the tip of the drain is grasped with the grasper (b, c). Then, the grasper is pulled back to introduce the drain into the pouch of Douglas (d, e). Final appearance (f)

Conclusion

Medical therapy is inefficient and can not be recommended in the management of ovarian endometriomas. While the surgical treatment of choice is surgical laparoscopy, for conservative treatment, the preferred method is modified combined cystectomy. There are no indications for systematic pre-operative medical treatment to facilitate the cystectomy. Post-operative medical treatment has no benefits in cases of infertility. But, treatment of the endometriosis, as well as endometriomas, must be individualized, taking the clinical problem in its entirety into account, including the impact of the disease and the effect of its treatment on quality of life. Therefore, it is vital to take careful note of the woman’s complaints and to give her time to express her concerns and anxieties, as in other chronic diseases.

The excision of the cyst wall in endometriomas is strongly recommended, especially in infertile patients. However, in light of all of this evidence, we can conclude that cystectomy may be destructive to the ovary. On the contrary, inefficient coagulation may create a great risk of recurrence. The modified combined technique, therefore, is the best approach to remove the endometrioma without increasing the recurrence rate and ovarian tissue damage.

It is essential to minimize or avoid spillage of endometrioma contents during surgical resection and thereby avoid the need for irrigation and suction. Use of careful dissection, aspiration of the endometrioma fluid before rupture, and a sterile bag collection device to avoid spillage of the endometrioma fluid are possible substitute techniques to the currently accepted surgical approach.

It has been shown that the stripping procedure used in laparoscopy for ovarian cyst excision appears to be an organ-preserving procedure. Besides, in non-endometriotic cysts, some ovarian tissue was inadvertently excised with the cyst wall in the endometriotic cysts. These specimens included some ovarian tissue, approximately 1–2 mm in thickness, excised along with the cyst pseudocapsule; this tissue, however, did not show the morphologic characteristics seen in normal ovarian tissue. Still, it should be kept in mind that there is lack of evidence in long-term follow-up. Therefore, meticulous attention should be given during the stripping procedure.

The learning curve for difficult surgical procedures, such as the adequate treatment of ovarian endometrioma, is probably the most important point. To overcome this problem, surgeons have to attend courses, buy books, and read papers to learn the technique in detail. They have to convince the hospital directors that they should buy a new set of expensive and often fragile instruments and collaborate with the anesthesiologists, who may have to adapt their practice to the requirements of endoscopy. Finally, they have to start the technique and train the operating theater team. As time goes on, their technique will improve, the conversion rate to laparotomy will decrease, and the advantages of laparoscopy will become obvious. There is ample evidence to show that every gynecologic surgeon should move to laparoscopy to manage benign adnexal conditions. They should be willing to learn the technique and simply have to accept the stress and the time involved with the development of the endoscopic revolution in their own department. From our experience in teaching laparoscopy to residents, we are convinced that for young surgeons, training for endoscopy is similar to training for laparotomy.

It should be remembered that some recent data add evidence against laparoscopic ovarian surgery for endometriomas in asymptomatic patients who are candidates for IVF. For this purpose, a meticulous surgical technique should be applied to the endometriomas. Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy is recommended if an ovarian endometrioma ≥4 cm in diameter is present to confirm the diagnosis histologically, reduce the risk of infection, improve access to follicles, and possibly improve ovarian response. The woman should be counseled regarding the risks of reduced ovarian function after surgery and the loss of the ovary. The decision should be reconsidered if she has had previous ovarian surgery. If it is possible, the technique should standardized. The endoscopic treatment of an endometrioma is a relatively simple procedure and requires specific training, just as it does to learn the treatment by laparotomy. To start the surgical procedure, a surgeon needs a detailed description, including instruments, patient selection, installation, and steps in the procedures, as well as the difficulties. The level of expertise in endometriosis surgery is inversely correlated with inadvertent removal of healthy ovarian tissue along with the endometrioma capsule. In inexperienced hands, cystectomy can be destructive to the ovary, whereas ablation may be incomplete, with a greater risk of recurrence. To the best of our knowledge, the modified combined technique seems to be more efficient for the treatment of endometriomas.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Concept - C.Ü., G.Y.; Design - G.Y., C.Ü.; Supervision - C.Ü., G.Y.; Resource - C.Ü., G.Y.; Materials - G.Y., C.Ü.; Data Collection&/or Processing - G.Y., C.Ü.; Analysis&/or Interpretation - C.Ü., G.Y.; Literature Search - G.Y., C.Ü.; Writing - G.Y., C.Ü.; Critical Reviews - C.Ü., G.Y.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Shebl O, Ebner T, Sommergruber M, Sir A, Tews G. Anti-Muellerian hormone serum levels in women with endometriosis: a case-control study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:713–716. doi: 10.3109/09513590903159615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamson GD. Endometriosis classification: An update. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23:213–20. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328348a3ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montagnana M, Lippi G, Danese E, Franchi M, Guidi GC. Usefulness of serum HE4 in endometriotic cysts. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:548–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore RG, Jabre-Raughley M, Brown AK, Robison KM, Miller MC, Allard WJ, et al. Comparison of a novel multiple marker assay vs the Risk of Malignancy Index for the prediction of epithelial ovarian cancer in patients with a pelvic mass. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:228–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacob F, Meier M, Caduff R, Goldstein D, Pochechueva T, Hacker N, et al. No benefit from combining HE4 and CA125 as ovarian tumor markers in a clinical setting. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:487–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huhtinen K, Suvitie P, Hiissa J, Junnila J, Huvila J, Kujari H, et al. Serum HE4 concentration differentiates malignant ovarian tumours from ovarian endometriotic cysts. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1315–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somigliana E, Vercellini P, Viganó P, Ragni G, Crosignani PG. Should endometriomas be treated before IVF-ICSI cycles? Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:57–64. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagle C, Olsen C, Webb P, Jordan S, Whiteman D, Green A. Endometrioid and clear cell ovarian cancers: a comparative analysis of risk factors. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2477–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ness R. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: thoughts on shared pathophysiology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:280–94. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Velasco JA, Somigliana E. Management of endometriomas in women requiring IVF: to touch or not to touch. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:496–501. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy S, Bergqvist A, Chapron C, D’Hooghe T, Dunselman G, Greb R, et al. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2698–704. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapron C, Vercellini P, Barakat H, Vieira M, Dubuisson JB. Management of ovarian endometriomas. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:591–7. doi: 10.1093/humupd/8.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tinkanen H, Kujansuu E. In vitro fertilisation in patients with ovarian endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:119–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079002119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith LP, Williams CD, Doyle JO, Closshey WB, Brix WK, Pastore LM. Effect of endometrioma cyst fluid exposure on peritoneal adhesion formation in a rabbit model. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:1173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.08.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marana R, Caruana P, Muzii L, Catalano GF, Mancuso S. Operative laparoscopy for ovarian cysts excision vs. aspiration. J Reprod Med. 1996;41:435–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alborzi S, Ravanbakhsh R, Parsanezhad ME, Alborzi M, Alborzi S, Dehbashi S. A comparison of follicular response of ovaries to ovulation induction after laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy or fenestration and coagulation versus normal ovaries in patients with endometrioma. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:507–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nezhat C, Silfen SL, Nezhat F, et al. Surgery for endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1991;3:385–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canis M, Pouly JL, Tamburro S, Mage G, Wattiez A, Bruhat MA. Ovarian response during IVF-embryo transfer cycles after laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for endometriotic cysts of >3 cm in diameter. Hum Reprod. 2001;12:2583–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.12.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marconi G, Vilela M, Quintana R, Sueldo C. Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy of endometriomas does not affect the ovarian response to gonadotropin stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:876–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart R, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16:CD004992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004992.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muzii L, Bellati F, Bianchi A, Palaia I, Manci N, Zullo M, et al. Laparoscopic stripping of endometriomas: a randomized trial on different surgical techniques. Part II. Pathological results. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1987–92. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muzii L, Bianchi A, Crocè C, Manci N, Panici PB. Laparoscopic excision of ovarian cysts: is the stripping technique a tissue-sparing procedure? Fertil Steril. 2002;77:609–14. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nargund G, Cheng W, Parsons J. The impact of ovarian cystectomy on ovarian response to stimulation during in-vitro fertilization cycles. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:81–3. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho H, Lee R, Hwu Y, Lin M, Su J, Tsai Y. Poor response of ovaries with endometrioma previously treated with cystectomy to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2002;19:507–11. doi: 10.1023/A:1020970417778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nisolle M, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:585–96. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donnez J, Lousse JC, Jadoul P, Donnez O, Squifflet J. Laparoscopic management of endometriomas using a combined technique of excisional (cystectomy) and ablative surgery. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baggish MS, Tucker RD. Tissue actions of bipolar scissors compared with monopolar devices. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:422–6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Postoperative adhesion formation after ovarian cystectomy with and without ovarian reconstruction. Abstract O-012, 47th annual meeting of the American Fertility Association; Orlando, FL. October 21–24 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Operative Laparoscopy Study Group. Postoperative adhesion development after operative laparoscopy: evaluation at early second-look procedure. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:700–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Redwine DB. Conservative laparoscopic excision of endometriosis by sharp dissection: life table analysis of reoperation and persistent or recurrent disease. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:628–34. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]