Abstract

A personal history of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is prevalent and deleterious to health for people living with HIV (PLWH), and current statistics likely underrepresent the frequency of these experiences. In the general population, the prevalence of CSA appears to be higher in men who have sex with men (MSM) than heterosexual men, but there are limited data available for HIV-infected MSM. CSA is associated with poor mental and physical health and may contribute to high rates of HIV risk behaviors, including unprotected sex and substance abuse. CSA exposure is also associated with low engagement in care for PLWH. More information is needed regarding CSA experiences of HIV-infected MSM to optimize health and wellbeing for this population and to prevent HIV transmission. This article reviews the epidemiology, implications, and interventions for MSM who have a history of CSA.

Keywords: adherence, childhood sexual abuse, HIV infection, HIV prevention, men who have sex with men

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is a prevalent and far-reaching event that impacts the lives of many people. With population-based prevalence estimates ranging from 1 to 32%, it is an issue that needs to be addressed and understood across demographic groups by health and social disciplines (Arnow, 2004; Briere & Elliott, 2003; Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, 2010). In 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) determined from interviews with 262,229 men and women interviewed from five different states that 12.2% of adults in the United States had experienced CSA (CDC, 2010). Although these numbers are startling in their magnitude, they are thought to be underestimates of the true prevalence.

Of the available literature describing the implications and effects of CSA, a relatively small but growing body focuses on the HIV-infected population. The HIV-infected population faces unique challenges in fostering and maintaining physical and psychological well-being, including high rates of CSA exposure, which will be discussed below. Within the population of people living with HIV (PLWH), 75% of men identify as men who have sex with men (MSM), but little is known about their CSA histories except for what is informally disclosed in patient/client–provider relationships (CDC, 2011). A description of the epidemiology and possible impacts of CSA on HIV-infected MSM is important because it may add to our understanding of the need for routine screening and new interventions to address CSA for a large proportion of PLWH.

In this review, we seek to summarize the existing literature on HIV-infected MSM with a history of CSA. Specifically, this article builds on previous reviews and reports by providing an up-to-date summary of the epidemiology of CSA and HIV-infected MSM as well as the known interactions between HIV and a history of CSA in terms of health, risk behaviors, potential impact on disease transmission, and engagement in HIV care (Relf, 2001). We also review the available evidence on interventions that could have a role in HIV treatment as well as transmission prevention. This summary was completed to improve awareness of the characteristics and needs of this particularly vulnerable population in the context of childhood experiences characterized by stigma and nondisclosure.

Methods

A search of the English language literature was performed using the PubMed, Ovid, Web of Science, and PsycInfo databases. The following MeSH terms were used: childhood sexual abuse, men who have sex with men, HIV seropositivity, male, health status, and health knowledge, attitudes, and practice. Twenty-seven years (1984–2011) of published research on the topic of CSA in the developed world was reviewed. Older literature was included because the earliest studies form the foundation on which subsequent CSA research was based. Eighty-one abstracts were reviewed by two of the authors (KS and SG), and 53 articles were included in the final review conducted by all three authors. The United States and Canada were the most common study sites in this body of literature, but individual articles also used data from Australia, South Korea, Great Britain, Greenland, and Switzerland. Excluded articles included studies that only involved children as well as studies with exclusively female samples with findings that could not be applied to male populations. Selected articles with exclusively female samples were included for discussion of possible evidence-based interventions that could be extrapolated to men.

CSA Definitions

CSA is generally defined as any activity involving a child below the age of legal consent in which the purpose was sexual gratification of an adult or older child (Johnson, 2004). Traditionally, sexual abuse has been stereotyped as involving a female victim and a male perpetrator. Recent definitions include abuse occurring outside of the family and involving nongenital contact. These newer definitions also provide specific details about the victim’s age and the role of the parent and/or caregiver (Mimiaga et al., 2009).

Doll and colleagues (1992) were one of the first research groups to consider CSA specifically among patients who self-identified as MSM. The investigators asked participants if they had ever been encouraged or forced to have sexual contact before the age of 19 with someone they perceived as older or more powerful. Participants provided data on the nature of the sexual contact, the age at which they first experienced abuse, the age of the partner/perpetrator, the relationship to the perpetrator, the length of time over which the contacts occurred, and whether verbal or physical force occurred. Participants were divided into six mutually exclusive categories based on the level of sexual contact and then assigned a single score based on the most invasive level of contact. Doll and colleagues’ (1992) scale has since been used by researchers to characterize the nature of CSA among MSM in other populations (Bartholow et al., 1994).

Other studies have defined CSA among MSM patients more generally as a sexual experience with a person at least 5 years older if the child is under the age of 13, with or without physical contact, and regardless of whether sex was wanted by the child (Lenderking et al., 1997). Some researchers simply asked participants whether or not they had ever been forced into unwanted sexual activity with adults and, if so, to describe the frequency of abuse (Brennan, Hellerstedt, Ross, & Welles, 2007; Welles et al., 2009; Zierler et al., 1991). O’Leary, Purcell, Remien, and Gomez (2003) judged the prevalence of CSA in a sample of MSM from New York and San Francisco by asking participants, Have you ever been pressured, forced, or intimidated into doing something sexually that you did not want to do? These situations may have involved sexual fondling, oral sex, penetration with a finger or object, or intercourse.

In a study involving the coping with HIV/AIDS in the southeast (CHASE) cohort, comprised of HIV-infected patients from Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina, participants were asked about sexual encounters before age 16 with anyone at least 5 years older as well as an open-ended question about other unwanted experiences (Mugavero et al., 2006). In order to meet criteria for abuse, participants must have experienced at least one of the following: (a) a perpetrator ever touched their breasts, pubic area, vagina, or anus; (b) they were ever asked to touch the perpetrator; or (c) they were ever coerced into having vaginal or anal intercourse (Mugavero et al., 2006). More recent research defined child abuse solely with regard to the age of the victim and perpetrator (Mimiaga et al., 2009).

Although the definitions of CSA are myriad, common criteria (e.g., the age of the victim and perpetrator as well as the degree of sexual contact) have emerged from various studies. At present, there is no clear consensus on the specific details of an appropriate CSA definition.

CSA Epidemiology

CSA in the general population

Through interviews of both children and caretakers in two national telephone surveys conducted in 2003 and 2008 (N = 2,030 and 4,046, respectively), Finkelhor and colleagues (2010) found that 6.7%–8% of children 2–17 years old have experienced sexual victimization. In other population-based samples, the prevalence of CSA among men and women fell in the ranges of 1%–16% and 8%–32%, respectively (Arnow, 2004). Similarly, Briere and Eliot (2003), in a study of a geographically-specific sample of adult men and women, found that 14.3% of men and 32.3% of women had had exposure to CSA (N = 935).

CSA in MSM

In a comparison of findings from a population-based sample of urban MSM (N = 2,881) to previously published data on CSA experiences for men in general, the prevalence of CSA in MSM was found to be 2–4 times higher than in men in general (Paul, Catania, Pollack, & Stall, 2001). The estimated prevalence of CSA in MSM is usually highest in clinic-based population samples (Arnow, 2004; Brennan et al., 2007). Data from a lower-risk MSM sample at the Minneapolis and St. Paul gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender pride festivals (N = 936) revealed that approximately 14% of men interviewed had a history of CSA, whereas 34%–37% from the clinical population reported CSA exposure (Brennan et al., 2007). Similarly, Mimiaga and colleagues (2009, N = 4295), and Doll and colleagues (1992, N = 1001) found CSA exposure rates of 39.7% and 37%, respectively, in their studies of MSM.

In several studies examining the prevalence of CSA in MSM, risk factors included having a low income, being African American or Latino, and having a low level of education (Kalichman, Sikkema, DiFonzo, Luke, & Austin, 2002; Mimiaga et al., 2009; Paul et al., 2001). However, there has been evidence that CSA is also prevalent among White, educated, middle-class populations (Bartholow et al., 1994; Brennan et al., 2007; Lenderking et al., 1997). Bartholow and colleagues (1994) found that 61% of respondents (N = 1,001) had completed high school, and the overall results did not indicate significant differences due to age, ethnicity, or education level. Cohorts of HIV-infected MSM also displayed conflicting results in terms of racial differences. In a multicenter study in six cities across the United States, Welles and colleagues (2009) found that 58% of Latino respondents and 49% of African American respondents had experienced CSA compared with 29% of Caucasian participants. Conversely, results from the CHASE cohort did not show any differences based on race; instead, childhood poverty and lack of a stable social structure were more significant determinants of CSA prevalence (Whetten & Reif, 2006).

CSA in HIV-infected MSM

Fewer studies have focused specifically on the prevalence of CSA among the HIV-infected MSM population, but some evidence has suggested that rates of CSA in HIV-infected individuals are extremely high. In a 1991 study of randomly selected participants (n = 52) from an Atlanta-based AIDS service organization, 65% of participants reported CSA, whereas a larger study of HIV-infected MSM in six cities (n = 593) found that 47% of respondents had a history of at least one lifetime experience with CSA (Welles et al., 2009). Lenderking and colleagues (1997, N = 327) found a CSA exposure rate of 35% in a mixed population of HIV-infected and noninfected MSM. CSA exposure in HIV-infected MSM has also been compared with exposure in HIV-infected women, and rates appeared similar with documented prevalence of 25%–38% (N = 611; Whetten et al., 2006).

Researchers have documented the age at which individuals first experience abuse. Kalichman, Gore-Felton, Benotsch, Cage, and Rompa (2004) demonstrated an early onset of abuse in a mixed HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected sample of MSM, with 17% of men reporting that they had experienced abuse before the age of 6 and 22% between the ages of 7 and 15 (N = 357). Within an exclusively HIV-infected cohort, 30% of men with a history of CSA reported being abused before age 13 (Whetten et al., 2006).

Studies that have addressed the prevalence of CSA in MSM have traditionally focused on urban samples (Bartholow et al., 1994; Brennan et al., 2007; Doll et al., 1992; Mimiaga et al., 2009; O’Leary et al., 2003; Paul et al., 2001; Welles et al., 2009). According to Whetten and Reif (2006), the deep south of the United States is not only hampered by lack of insurance coverage, high poverty levels, and an inadequate health care infrastructure, but this geographic region also has the highest number of new AIDS cases and AIDS-related deaths. Compared with other regions, a higher reported incidence of CSA in HIV-infected MSM in the south has been documented. Among 611 respondents from the CHASE cohort, 54% reported a history of physical and/or sexual abuse (Mugavero et al., 2006). When controlling for gender and sexual orientation, MSM in the southern, rural-based CHASE cohort were twice as likely to have had exposure to physical and/or sexual abuse compared with heterosexual men (Whetten et al., 2006).

Perpetrators of CSA

According to available research, perpetrators of CSA were often men who were unlikely to be strangers and were approximately 16 years older than the victims (Lenderking et al., 1997; Paul et al., 2001). These findings supported earlier work that found, for MSM, 94% of CSA exposures (N = 1,001) involved a male perpetrator who was significantly older and “more powerful” than the victim (Doll et al., 1992). Conversely, Welles and colleagues (2009) found that only 58% of participants (N = 593) were sexually abused by a male perpetrator, implying that female abusers were also involved in many cases. Regardless of gender, the perpetrator has often been reported to be a family member or mentor (Fields, Malebranche, & Feist-Price, 2008).

Investigators have attempted to characterize the number of abuse events and the potential role of caregivers (Kalichman et al., 2002). The abuse was often not an isolated incident; one study found that the mean number of “lifetime unwanted sexual events” among HIV-infected men and women was 9.7 (SD = 2.7) with a mean age of 13.3 years for first experiences of unwanted sexual activity (Kalichman et al., 2002). Whetten and colleagues (2006) examined the nature of caregivers of persons who experienced CSA and found a strong correlation between a high prevalence of CSA and having parents or a caregiver who were too drunk or high to take care of their children.

CSA and Health

Implications for psychological health

Although psychological health and physical well-being are inextricably linked, we discuss the impact of CSA on each category separately here to highlight the differential effects. There is a strong relationship between CSA and poor mental health (Najman, Nguyen, & Boyle, 2007). Psychological consequences associated with a CSA history include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders (Allers, Benjack, White, & Rousey, 1993; Dube et al., 2005; Fergusson & Mullen, 1999). Men who experienced CSA were more likely to have attempted suicide and engaged in suicidal thinking than men who had no CSA exposure (Bebbington et al., 2009). More specifically, evidence has indicated that men exposed to CSA were more than 2 times as likely to attempt suicide as men who were not abused (Dube et al., 2005).

Existing literature also suggests that the experience of CSA may affect more durable personality traits. Lisak’s (1994) qualitative study of men exposed to CSA described a legacy of abuse that was characterized by feelings of helplessness, anger, fear, alienation, shame, isolation, sexuality and masculinity issues, and negative perceptions of self and others. Similarly, in a qualitative study of HIV-uninfected Black men from the U.S. cities of Atlanta, Rochester, and Lexington, Fields and colleagues (2008) found that CSA was linked with feelings of isolation, social anxiety, and an increased incidence of mental health disorders. For instance, one participant described himself as bipolar, whereas another claimed that he was aggressive in his interactions with other people as a consequence of the sexual abuse. The results of these studies suggest that the psychological impact of CSA extends beyond childhood and affects later life experiences, social connections, and overall mental health.

Abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs has also been found to be commonly associated with CSA (Dube et al., 2005). MSM with a history of forced sexual contact were found to report higher rates of alcohol and substance abuse, high-risk sex, depression, and suicidal ideation compared with MSM without a history of CSA (Arreola, Neilands, Pollack, Paul, & Catania, 2008). HIV-infected MSM who also experienced CSA were more likely to have been hospitalized for substance use and sought mental health counseling than men who did not experience abuse (Allers et al., 1993; Bartholow et al., 1994). Abused men were also more likely to have used cocaine, crack, stimulants, hallucinogens, and opiates than nonabused men (Bartholow et al., 1994).

Implications for physical health

Although there is robust evidence to support associations between CSA exposure and psychological sequelae, fewer studies have investigated implications for men’s physical health. Literature has revealed that a history of CSA is correlated with multiple health problems, poorer self-rated health, and higher odds of disability (Chartier, Walker, & Naimark, 2007). Other studies have corroborated these findings by showing that male victims of CSA had lower scores on health and well-being surveys, such as the Short Form-36, and a higher frequency of health problems than their nonabused counterparts (Najman et al., 2007; Sachs-Ericsson, Blazer, Plant, & Arnow, 2005).

Specific health problems associated with CSA have included chronic fatigue syndrome, thyroid disease, obesity, and heart disease (Gustafson & Sarwer, 2004; Heim et al., 2006; Stein & Barrett-Connor, 2000). The prevalence of HIV may be up to two times higher in male victims of CSA compared with nonabused males (Zierler et al., 1991). The Adverse Childhood Experiences study investigated specifics about some of these health problems and found a statistically significant relationship between obesity and CSA history (Felitti, 1993). Subsequent research in a female cohort detected an independent association between repeated forced sex in childhood and increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus (Rich-Edwards et al., 2010). Further analysis of data from the Adverse Childhood Experience study also demonstrated an increased risk of ischemic heart disease associated with CSA exposure, a relationship in which pathophysiology needs greater elucidation (Dong et al., 2004). Because the existing literature increasingly has supported associations between CSA and a variety of physical conditions, additional investigation will be necessary to clarify the relationship between CSA and physical health for men.

As described above, men and women who experience CSA are at higher risk for mental and physical illnesses. Available literature that has examined how utilization of care may also be related to CSA has focused largely on women, but will be included here to illustrate the relevant principles of CSA exposure and health care use (Arnow, 2004; Liebschutz, Feinman, Sullivan, Stein, & Samet, 2000). Although CSA-exposed PLWH were more likely to present early for HIV care and to utilize medical and emergency services, they also have had poorer antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence than their counterparts without a history of CSA (Meade, Hansen, Kochman, & Sikkema, 2009; Mugavero et al., 2007). Additionally, both HIV-infected and uninfected women with CSA histories were more likely to seek medical care for sexually transmitted illnesses (STIs) and seek pregnancy care earlier than women without CSA exposure (Cohen et al., 2004; Greenberg, 2001). Therefore, targeting settings such as STI clinics may be an important strategy for identifying patients with a CSA history and, consequently, potentially mitigating the detrimental effects of the abuse on health.

CSA and HIV

Risk behavior and HIV transmission

In addition to associations between CSA and chronic health conditions, experiencing sexual abuse in childhood is also connected with a continuum of risky sexual behavior later in life. Several studies have found associations between men’s CSA exposure and unprotected sex, receiving compensation for sex, and sex with multiple partners, thereby putting them at risk of contracting HIV and also putting their partners at risk (Allers et al., 1993; Bartholow et al., 1994; O’Leary et al., 2003; Zierler et al., 1991). When controlling for variables such as study site, age at enrollment, education, and race, the EXPLORE study of HIV-uninfected men (N = 4,295) from six cities across the United States found that there was a significant association between a history of CSA and unprotected anal sex (Mimiaga et al., 2009). Zierler and colleagues (1991) found that male survivors of CSA were twice as likely to have multiple sex partners, four times as likely to have worked as commercial sex workers, and 40% more likely to have had sex with a stranger compared with men without CSA exposure. In the Midwestern United States, HIV-infected MSM who experienced CSA were seven times more likely to exchange sex for money and three times more likely to be diagnosed with an STI (Brennan et al., 2007). Although the number of HIV-infected MSM participants with a CSA history only comprised 68 individuals, O’Leary and colleagues (2003) found a strong tendency toward both unprotected insertive and receptive anal intercourse with an HIV-uninfected partner in the preceding 90 days. These studies suggest that men with traumatic histories are more likely to engage in harmful or risky behaviors that could potentially lead to increased HIV transmission. Recent work has suggested that maladaptive alcohol use associated with male victims of CSA may mediate the observed relationship between an abuse history and increased sexual risk taking (Schraufnagel, Davis, George, & Norris, 2010).

In addition to the apparent relationship between CSA and subsequent risky behavior, some studies have shown that rates of unsafe sexual practices varied based on the experiences of the men involved. Results from a study of HIV-infected MSM from the U.S. cities of Seattle, Washington, D.C., Boston, New York, Los Angeles, and Houston revealed an association between CSA and increased unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) among men who already had a tendency to engage in risky behavior, as defined by scores on the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory combined with measures of depression, anxiety, and substance abuse (Welles et al., 2009). The implications of this finding are unclear, but the finding suggests that men who experience CSA may perceive the risk level of their behaviors differently from men who have not experienced CSA. Another study asked HIV-uninfected heterosexual men and MSM whether they defined their childhood sexual experiences (CSE) as sexual abuse (Holmes, 2008). Of the 43 participants who acknowledged CSE, 65% defined their respective experiences as an example of CSA. The 15 “nondefmers” were asked why they did not define their experience(s) as abuse and were provided with options for some possible reasons, such as I don’t think the person who initiated the experience meant harm, or I just haven’t thought of it like that. Participants who did not define their CSE as abuse were more likely to report sex while under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol and a higher mean number of lifetime partners, thereby putting them at increased risk for STIs and HIV infection. These findings suggest that men’s perceptions of CSE may influence future risky behaviors (Holmes, 2008).

CSA and Engagement in HIV Care

Traumatic events such as CSA are also important predictors of subsequent engagement in care, as measured by both attendance at scheduled clinic visits and adherence to ART (Cohen et al., 2004; Meade et al., 2009; Park et al., 2008; Ulett et al., 2009). Visit attendance and adherence to ART are critical elements if patients are to be fully engaged in care. These measures are often used as surrogate markers of engagement given the documented benefits of appointment attendance and consistent medication use on reducing viral load, raising the CD4+ T cell count, and, ultimately, survival. Exposure to higher levels of lifetime trauma (including, but not limited to, physical and sexual abuse) was associated with nonadherence, a factor that could contribute to poorer outcomes in an abused population (Giordano et al., 2007; Mugavero et al., 2006; Mugavero et al., 2009).

Discussion

Interventions

The high prevalence of CSA in MSM highlights the need to develop resources to educate health care professionals about childhood abuse and subsequently integrate appropriate interventions into clinical settings as well as sexual risk prevention programming. Some interventions demonstrate encouraging results and could be explored with specific reference to minimizing the long-term consequences of CSA. Although designed for women, psychosocial rehabilitation programs show promise as one potential modality that could be revised to address men’s needs. For example, Wyatt and colleagues (2004) found that HIV-infected women with a history of CSA who attended eight or more sessions that addressed past histories of abuse and incorporated sexual risk-reduction techniques had greater levels of adherence to treatment regimens compared with women who attended seven or fewer sessions. Furthermore, in the same cohort, researchers observed that having a solid social support network impacted medication adherence; for example, living with more family members or with a partner may lower stress levels and the incidence of substance abuse (Liu et al., 2006). It is also possible that redefining the CSE as abuse in a clinical setting might change a man’s perceptions of his own behaviors (Holmes, 2008).

The EXPLORE study was designed to evaluate the effects of a behavioral intervention on HIV risk outcomes (i.e., HIV infection, UAI with a partner of unknown HIV status, or UAI with a serodiscordant partner) over a 48-month period. Participants were randomized to standard risk-reduction measures or intensive counseling that addressed the following: perceptions of risk behavior, contextual issues (e.g., people, places) associated with risky behavior, the role of substance use, personal beliefs about serostatus, factors that could help or harm communication of personal boundaries, and adherence to established safety plans (Chesney et al., 2003). The results revealed that the intervention had an overall modest effect on reducing HIV infection rates (Mimiaga et al., 2009). When analyzed by CSA status, the intervention arm resulted in lower HIV infection rates, but only in CSA unexposed participants. The participants who experienced CSA had no difference in HIV infection rates between the control and intervention arms (Mimiaga et al., 2009).

These findings suggest that general counseling and behavioral interventions are not sufficient to reduce HIV infection risk for MSM who have experienced CSA. Rather, approaches may be more successful if they address CSA and potential mediators of the relationship between CSA and risk taking, including substance abuse and depression.

Implications and Future Directions for HIV-Infected MSM

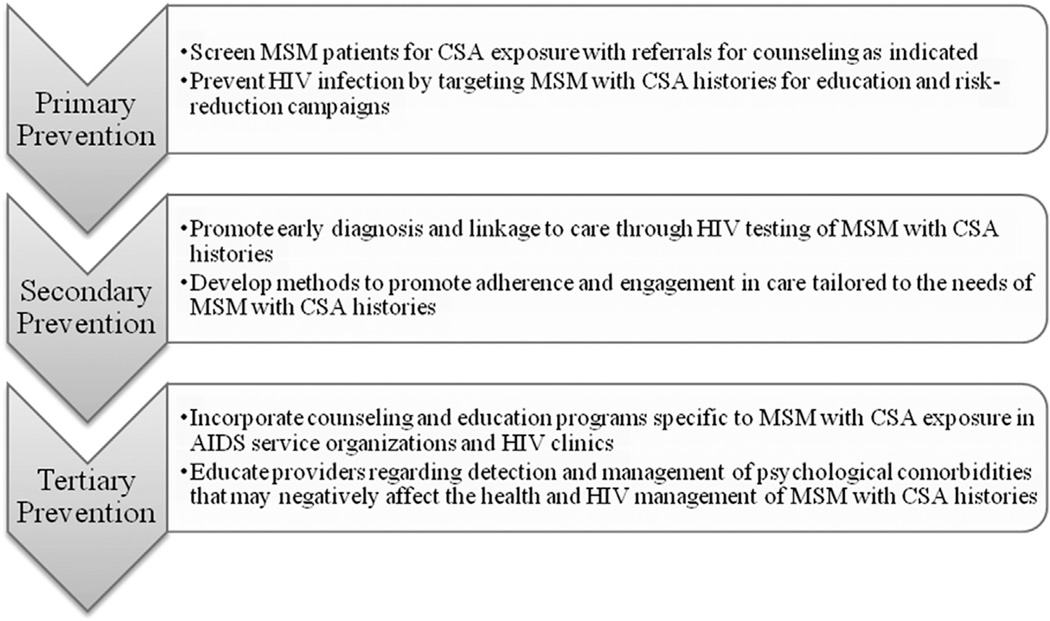

It is important to recognize CSA as a prevalent condition that affects psychological well-being, physical health, individual approaches to disease management, and prevention behaviors. CSA in the MSM population may increase risks of HIV transmission and negatively impact physical and psychological health through depression, negative coping, and substance abuse, which are often associated with poor adherence to treatment regimens (Boarts, Sledjeski, Bogart, & Delahanty, 2006; Liu et al., 2006; Mugavero et al., 2006). For these reasons, CSA exposure should inform health care providers that approaches to HIV prevention at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels should be implemented (Figure 1; Hensrud, 2000).

Figure 1.

Strategies to include CSA screening and management for HIV prevention programming. Adapted from Hensrud (2000).

Note: CSA = childhood sexual abuse; MSM = men who have sex with men

Given the impact that CSA has on health, HIV primary prevention programs and clinics should consider universal abuse screening and standardized trauma histories using consistent definitions for CSA and validated tools, such as the Sexual Abuse Questionnaire (Castelda, Levis, Rourke, & Coleman, 2007). Knowing that associations exist between CSA, alcohol use and abuse, and increased sexual risk taking, awareness of violence in a patient’s history could positively influence care and outcomes by allowing providers to anticipate risky behavior and substance use (Schraufnagel et al., 2010).

At the level of secondary prevention, adherence to ART is crucial for successful management of HIV, with greater than 95% adherence to treatment necessary to maintain CD4+ T cell levels and control viral loads (Bartlett, 2002). However, 40%–60% of patients are less than 90% adherent for a variety of reasons, including forgetfulness, changes in routines, busy schedules, increased levels of stress, or depression (Bartlett, 2002). Evaluation of data from the CHASE cohort demonstrated a significant increase in rates of nonadherence among participants who experienced more lifetime traumas, of which CSA was one category; for instance, there was a 9.5% incidence of nonadherence in participants with no trauma history and a 34.5% rate of nonadherence in their counterparts who had experienced five or more categories of trauma (Mugavero et al., 2006). These findings suggest the need for studies that investigate not only the prevalence of CSA in HIV-infected MSM populations but also the psychological sequelae of CSA and its effects on engagement in care.

Lastly, increased collaboration and exchange of resources between child abuse agencies, substance abuse treatment centers, and AIDS service organizations (ASOs) could perhaps lead to a reduction in risky behavior and HIV transmission as a method of tertiary prevention. Incorporating counseling, education programs, and interventions specific to MSM with CSA exposure in ASOs and HIV clinics as well as educating providers regarding detection and management of associated psychological comorbidities for MSM with CSA histories could promote greater adherence to treatment regimens and improve outcomes for HIV-infected patients with histories of sexual abuse. Table 1 lists some selected online resources that providers can use and recommend for adults who have experienced CSA.

Table 1.

Selected Online Resources for Adult Survivors of CSA

| Organization | Website |

|---|---|

| Child Sex Abuse Prevention and Protection Center | www.stopitnow.org |

| Adult Survivors of Child Abuse (ASCA) | http://www.ascasupport.org/index.php |

| Black Sexual Abuse Survivors (BSAS) | http://www.blacksurvivors.org/home.html |

| One in Six (for male survivors of CSA) | http://lin6.org/ |

| National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC) | http://www.nsvrc.org/ |

| Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network (RAINN) | http://www.rainn.org/ |

Note: CSA = childhood sexual abuse.

Existing literature has indicated a significant burden of abuse exposure that calls for development of counseling interventions tailored for MSM who have experienced CSA. Based on findings from the studies that were reviewed, these interventions should specifically address social support, sexual risk reduction, and capacity building for men to label their experiences as abuse.

Ultimately, more research is needed to address men’s experiences of CSA. Although most studies of CSA have focused on women, the existing literature would suggest that men also carry a significant burden of CSA exposure. Given the implications for health, these histories must be acknowledged and addressed. Building a comprehensive understanding of CSA for MSM living with HIV will enhance preventative and therapeutic care for patients.

Key Considerations.

HIV-infected MSM should be routinely screened for CSA exposure given the documented associations between poor health outcomes and history of CSA.

Men, in general, and MSM, in particular, should be included in all universal abuse screening endeavors.

Clinics should be equipped to provide resource information such as counseling, support groups, and substance abuse counseling for patients who have experienced CSA.

Efforts are needed to design and evaluate interventions tailored for MSM who have experienced CSA.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the University of Virginia School of Medicine and the Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health. The effort for creating this review was funded in part by NIH T32 Training Grant #5T32AI007046-33 (Principal Investigator: William Petri, MD, PhD) and the third author’s (Dr. Dillingham) K23 AI77339-01A1 award.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Katherine R. Schafer, Fellow at University of Virginia, Division of Infectious Diseases and International, Health, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA.

Shruti Gupta, Fourth Year Student at University of Virginia School, of Medicine, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA.

Rebecca Dillingham, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia, Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA.

References

- Allens CT, Benjack KJ, White J, Rousey JT. HIV vulnerability and the adult survivor of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1993;17(2):291–298. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(93)90048-a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(93)90048-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow BA. Relationships between childhood maltreatment, adult health and psychiatric outcomes, and medical utilization. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl. 12):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola S, Neilands T, Pollack L, Paul J, Catania J. Childhood sexual experiences and adult health sequelae among gay and bisexual men: Defining childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Sex Research. 2008;45(3):246–252. doi: 10.1080/00224490802204431. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224490802204431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholow BN, Doll LS, Joy D, Douglas JM, Jr, Bolan G, Harrison JS, McKirnan D. Emotional, behavioral, and HIV risks associated with sexual abuse among adult homosexual and bisexual men. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18(9):747–761. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)00042-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(94)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JA. Addressing the challenges of adherence. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;29(Suppl. 1):S2–S10. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200202011-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington PE, Cooper C, Minot S, Brugha TS, Jenkins R, Meltzer H, Dennis M. Suicide attempts, gender, and sexual abuse: Data from the 2000 British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(10):1135–1140. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(3):253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9069-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-006-9069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan DJ, Hellerstedt WL, Ross MW, Welles SL. History of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk behaviors in homosexual and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(6):1107–1112. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071423. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.071423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Elliott DM. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(10):1205–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelda BA, Levis DJ, Rourke PA, Coleman SL. Extension of the Sexual Abuse Questionnaire to other abuse categories: The initial psychometric validation of the Binghamton Childhood Abuse Screen. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2007;16(1):107–125. doi: 10.1300/J070v16n01_06. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J070v16n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse childhood experiences reported by adults - five states, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(49):1609–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance-United States, 1981–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60(21):689–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 60(25):852. erratum in. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B. Childhood abuse, adult health, and health care utilization: Results from a representative community sample. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165(9):1031–1038. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwk113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Koblin BA, Barresi PJ, Husnik MJ, Celum CL, Colfax G EXPLORE Study Team. An individually tailored intervention for HIV prevention: Baseline data from the EXPLORE study. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(6):933–938. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.933. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MH, Cook JA, Grey D, Young M, Hanau LH, Tien P, Wilson T. Medically eligible women who do not use HAART: The importance of abuse, drug use and race. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1147–1151. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1147. http://dx.doi.Org/10.2105/AJPH.94.7.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll LS, Joy D, Bartholow BN, Harrison JS, Bolan G, Douglas JM, Delgado W. Self-reported childhood and adolescent sexual abuse among adult homosexual bisexual men. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16(6):855–864. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90087-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(92)90087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williams JE, Chapman DP, Anda RF. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: Adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation. 2004;110(13):1761–1766. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143074.54995.7F. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000143074.54995.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RE, Whitfield CL, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH. Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(5):430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ. Childhood sexual abuse, depression, and family dysfunction in adult obese patients: A case control study. Southern Medical Journal. 1993;86(7):732–736. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Mullen PE. Childhood sexual abuse: An evidence based perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fields SD, Malebranche D, Feist-Price S. Childhood sexual abuse in black men who have sex with men: Results from three qualitative studies. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(4):385–390. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, Hamby SL. Trends in childhood violence and abuse exposure: Evidence from 2 national surveys. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164(3):238–242. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/arch-pediatrics.2009.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Jr, Suarez-Almazor ME, Rabeneck L, Hartman C, Morgan RO. Retention in care: A challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44(11):1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JB. Childhood sexual abuse and sexually transmitted diseases in adults: A review of and implications for STD/HIV programmes. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2001;12(12):777–783. doi: 10.1258/0956462011924380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/0956462011924380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson TB, Sarwer DB. Childhood sexual abuse and obesity. Obesity Reviews. 2004;5(3):129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00145.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Wagner D, Maloney E, Papanicolaou DA, Solomon L, Jones JF, Reeves WC. Early adverse experience and risk for chronic fatigue syndrome: Results from a population-based study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(11):1258–1266. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensrud DD. Clinical preventive medicine in primary care: Background and practice: 1. Rationale and current preventive practices. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2000;75(2):165–172. doi: 10.4065/75.2.165. http://dx.doi.Org/10.4065/75.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WC. Men’s self-definitions of abusive childhood sexual experiences, and potentially related risky behavioral and psychiatric outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(1):83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.005. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CF. Child sexual abuse. Lancet. 2004;364(9432):462–470. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16771-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16771-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Gore-Felton C, Benotsch E, Cage M, Rompa D. Trauma symptoms, sexual behaviors, and substance abuse: Correlates of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risks among men who have sex with men. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2004;13(1):1–15. doi: 10.1300/J070v13n01_01. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J070v13n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, DiFonzo K, Luke W, Austin J. Emotional adjustment in survivors of sexual assault living with HIV-AIDS. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15(4):289–296. doi: 10.1023/A:1016247727498. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1016247727498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenderking WR, Wold C, Mayer KH, Goldstein R, Losina E, Seage GR., 3rd Childhood sexual abuse among homosexual men. Prevalence and association with unsafe sex. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12(4):250–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012004250.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-5049-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebschutz JM, Feinman G, Sullivan L, Stein M, Samet J. Physical and sexual abuse in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: Increased illness and health care utilization. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(11):1659–1664. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisak D. The psychological impact of sexual abuse: Content analysis of interviews with male survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1994;7(4):525–548. doi: 10.1007/BF02103005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Longshore D, Williams JK, Rivkin I, Loeb T, Warda US, Wyatt G. Substance abuse and medication adherence among HIV-positive women with histories of child sexual abuse. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(3):279–286. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9041-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-005-9041-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Utilization of medical treatments and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive adults with histories of childhood sexual abuse. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2009;23(4):259–266. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/apc.2008.0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Noonan E, Donnell D, Safren SA, Koenen KC, Gortmaker S, Mayer KH. Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with HIV risk-taking behavior and infection among MSM in the EXPLORE study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;51(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero M, Ostermann J, Whetten K, Leserman J, Swartz M, Stangl D, Thielman N. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: The importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2006;20(6):418–428. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.418. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/apc.2006.20.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero MJ, Pence BW, Whetten K, Leserman J, Swartz M, Stangl D, Thielman NM. Childhood abuse and initial presentation for HIV care: An opportunity for early intervention. AIDS Care. 2007;19(9):1083–1087. doi: 10.1080/09540120701351896. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120701351896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Reif S, Whetten K, Leserman J, Thielman NM, Pence BW. Overload: Impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71(9):920–926. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bfe8d2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bfe8d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Nguyen ML, Boyle FM. Sexual abuse in childhood and physical and mental health in adulthood: An Australian population study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36(5):666–675. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9180-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary A, Purcell D, Remien RH, Gomez C. Childhood sexual abuse and sexual transmission risk behaviour among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2003;15(1):17–26. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000039725. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0954012021000039725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park WB, Kim JY, Kim SH, Kim HB, Kim NJ, Oh MD, Choe KW. Self-reported reasons among HIV-infected patients for missing clinic appointments. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2008;19(2):125–126. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2007.007101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JP, Catania J, Pollack L, Stall R. Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(4):557–584. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00226-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relf MV. Childhood sexual abuse in men who have sex with men: The current state of the science. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2001;12(5):20–29. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60260-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich-Edwards JW, Spiegelman D, Lividoti Hibert EN, Jun HJ, Todd TJ, Kawachi I, Wright RJ. Abuse in childhood and adolescence as a predictor of type 2 diabetes in adult women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39(6):529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs-Ericsson N, Blazer D, Plant EA, Arnow B. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and the 1-year prevalence of medical problems in the national comorbidity survey. Health Psychology. 2005;24(1):32–40. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraufnagel TJ, Davis KC, George WH, Norris J. Childhood sexual abuse in males and subsequent risky sexual behavior: A potential alcohol-use pathway. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(5):369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Barrett-Connor E. Sexual assault and physical health: Findings from a population-based study of older adults. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62(6):838–843. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200011000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, Routman JS, Abroms S, Allison J, Mugavero MJ. The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(1):41–49. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/apc.2008.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welles SL, Baker AC, Miner MH, Brennan DJ, Jacoby S, Rosser BR. History of childhood sexual abuse and unsafe anal intercourse in a 6-city study of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(6):1079–1086. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133280. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.133280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Leserman J, Lowe K, Stangl D, Thielman N, Swartz M, Van Scoyoc L. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and physical trauma in an HIV-positive sample from the deep south. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(6):1028–1030. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063263. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.063263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Reif S. Overview: HIV/AIDS in the deep south region of the United States. AIDS Care. 2006;18(Suppl. 1):S1–S5. doi: 10.1080/09540120600838480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120600838480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE, Longshore D, Chin D, Carmona JV, Loeb TB, Myers HF, Rivkin I. The efficacy of an integrated risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive women with child sexual abuse histories. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8(4):453–462. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7329-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-004-7329-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zierler S, Feingold L, Laufer D, Velentgas P, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Mayer K. Adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse and subsequent risk of HIV infection. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(5):572–575. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.572. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.81.5.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]