Abstract

Background

Identifying risk factors for inferior outcomes after ACL reconstruction (ACLR) is important for prognosis and future treatment. The goal of this study was to determine whether articular cartilage and meniscal variables are predictive of 3 validated sports outcome instruments after ACLR.

Hypothesis/Purpose

We hypothesized that articular cartilage lesions and meniscus tears/treatment would be predictors of the IKDC, KOOS (all 5 subscales), and Marx activity level at 6 years following ACLR.

Study Design

Prospective cohort, Level 1

Methods

Between 2002 and 2004, 1512 ACLR subjects were prospectively enrolled and followed longitudinally with the IKDC, KOOS, and Marx activity score completed at entry, 2, and 6 years. A logistic regression model was built incorporating variables from patient demographics, surgical technique, articular cartilage injuries, and meniscus tears/treatment to determine the predictors (risk factors) of IKDC, KOOS, and Marx at 6 years.

Results

We completed a minimum follow-up on 86% (1307/1512) of our cohort at 6 years. The cohort was 56% male, had a median age of 23 years at the time of enrollment, with 76% reporting a non-contact injury mechanism. Incidence of concomitant pathology at the time of surgery consisted of the following: articular cartilage (medial femoral condyle [MFC]-25%, lateral femoral condyle [LFC]-20%, medial tibial plateau [MTP]-6%, lateral tibial plateau [LTP]-12%, patella-20%, trochlear-9%) and meniscal (medial-38%, lateral-46%).

Both articular cartilage lesions and meniscal tears were significant predictors of 6-year outcomes on IKDC and KOOS. Grade 3 or 4 articular cartilage lesions (excluding patella) significantly reduced IKDC and KOOS scores at 6 years. IKDC demonstrated worse outcomes with the presence of a grade 3-4 chondral lesion on the MFC, MTP, and LFC. Likewise, KOOS was negatively affected by cartilage injury. The sole significant predictor of reduced Marx activity was the presence of a grade 4 lesion on the MFC.

Lateral meniscus repairs did not correlate with inferior results, but medial meniscus repairs predicted worse IKDC and KOOS scores. Lateral meniscus tears left alone significantly improved prognosis. Small partial meniscectomies (<33%) on the medial meniscus fared worse, but conversely, larger excisions (>50%) on either the medial or lateral menisci improved prognosis.

Analogous to previous studies, other significant predictors of lower outcome scores were lower baseline scores, higher BMI, lower education level, smoking, and ACL revisions.

Conclusions

Both articular cartilage injury and meniscal tears/treatment at the time of ACLR were significant predictors of IKDC and KOOS scores 6 years following ACLR. Similarly, having a grade 4 MFC lesion significantly reduced a patient’s Marx activity level score at 6 years.

Keywords: anterior cruciate ligament, ACL reconstruction, outcomes, articular cartilage, meniscus, IKDC, KOOS, Marx activity rating scale

INTRODUCTION

Previous literature has shown that the presence of meniscal tears and/or chondral lesions has significant effects on the increased incidence of radiographic osteoarthritis (OA) in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injured patients with or without ACL reconstruction (ACLR).4,16,19,24,27,28 Meniscus tears were shown to significantly increase radiographic OA in a recent systematic review27 and meta-analysis.4 However, meniscus tears did not predict symptomatic OA.28 In cohort and case-control studies, incidence of articular cartilage pathology at the time of an ACLR has been shown to have worse KOOS36,37 and IKDC14,17 scores at follow-up. Similarly designed studies report that the presence of a concomitant meniscus injury correlates with significantly worse IKDC scores at follow-up.9,14,23 However, these aforementioned studies focused their risk factors on only meniscus and articular cartilage injury variables. Due to sample size limitations, they were unable to include and assess the many other potential risk factors besides meniscus and articular cartilage injuries. The most comprehensive models published to date have been two Level 2 cohorts from the Swedish National Knee Ligament Registry1 and the Norwegian and Swedish National Knee Ligament Registries.37 Barenius et al. performed a multivariable analysis for dichotomized KOOS outcomes as treatment failures versus functional recovery as defined by pre-specified KOOS scores.1 They observed that meniscus excision or repair was a significant predictor of treatment failure. However, articular cartilage injury was not found to be a significant predictor for treatment failure, despite using a limited classification system (yes/no). In 2013, Røtturud and colleagues reported worse outcomes in all 2-year follow-up KOOS subscales in patients who had concomitant full-thickness cartilage lesions compared with patients without cartilage lesions.37 However, meniscal lesions and partial-thickness cartilage lesions did not impair patient-reported outcomes 2 years after ACL reconstruction. In both comprehensive studies, their main limitations were patient follow-up: 2-year follow-up was only 41% (3556/8584) for Barenius et al.1 and 54% (8476/15,783) for Røtturud et al.37 As such, there has not been a Level 1 prospective cohort (>80% follow-up) with multivariable analysis to comprehensively evaluate the role of meniscus and articular cartilage injuries and treatment including majority of proposed risk factors (demographic, surgical choices, etc.) on both sport validated patient reported outcomes of IKDC and KOOS and activity level (Marx activity level) at 6 years following ACL reconstruction. Collectively, prior studies have been limited by the scope and breadth of results, primarily due to either small sample size or follow-up limitations.

This multicenter population cohort was designed in 2002 to prospectively determine which variables at the time of an ACL injury (including patient demographics, mechanism of injury, surgical technique/choices, concomitant meniscal and/or articular cartilage pathology and treatment, among other potential modifiable and non-modifiable variables) would influence and predict both short- and long-term outcomes following ACLR.2,3,6,7,8,15,18,20,22,32,40,42,43 Our previous modeling longitudinally followed over 400 ACLR subjects at 2 and 6 years.39 Despite identifying many significant risk factors for worse outcomes, we had insufficient sample size to determine if meniscal and articular cartilage pathology documented at the time of index ACLR has any effect on patient-reported outcomes following ACLR. To rectify this limitation, this current study utilizes two additional years of enrollment with 2- and 6-year follow-up to focus on the role that articular cartilage and meniscus injuries and treatment play at the time of index ACLR, in order to predict 6-year outcomes.

In this analysis, three enrollment years (2002-2004) with both 2- and 6-year follow-up were included in the largest, most comprehensive multivariable modeling of ACLR outcomes to date. We hypothesized that articular cartilage lesions and meniscus tears and treatment would be predictors of the IKDC, KOOS (five subscales), and Marx activity level at 6 years following ACLR.

METHODS

Setting and Study Population

After obtaining approval from respective institutional review boards, the multicenter consortium began enrolling patients in 2002 and consisted of seven sites with 12 surgeons over the three year enrollment period. One university functioned as the data processing center for the study and was responsible for entering baseline data and for collecting follow-up data on all subjects.

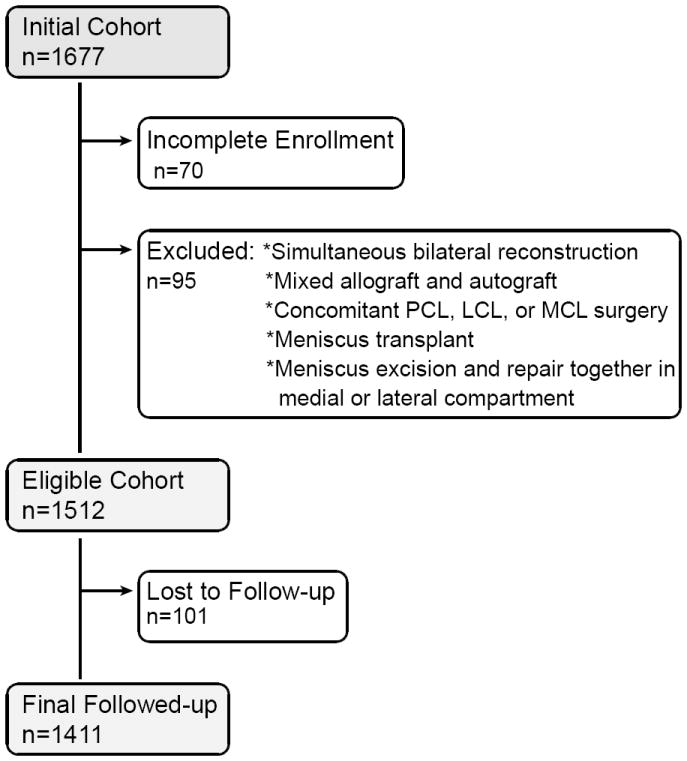

All patients who underwent unilateral primary or revision ACLR surgery between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2004, were eligible for enrollment. Multi-ligamentous injuries were included only if no concomitant PCL, MCL, and/or LCL repairs were performed. During this time frame, sites identified 1677 subjects who were slated to have ACLR. A total of 1512 subjects met the study’s inclusion criteria and were enrolled into the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Study Cohort

Legend: All anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) patients were enrolled during calendar years 2002-2004. Enrollment failures and patients not meeting inclusion criteria were removed leaving the eligible cohort as displayed. After removing those lost to follow up, the final number of study participants is shown.

Data Sources and Measurement

After informed consent was obtained, each participant completed a 13-page questionnaire that included baseline demographics, injury descriptors, sports participation level, comorbidities, knee surgical history, and patient-reported outcome measures that included the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC),12 Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) five subscales (symptoms, pain, activities of daily living [ADL], sports and recreation, knee-related quality of life),35 and Marx activity rating scale.21 Their validity, reliability, responsiveness to clinical change, and minimal clinically meaningful differences have been previously documented (IKDC;11-13 KOOS;30,34,35 Marx21). All questionnaires were completed within two weeks of the date of surgery with most completed prior to the procedure.

Immediately following the surgical procedure, each surgeon completed a 49-page questionnaire that documented the results of the exam under anesthesia, surgical technique, and the arthroscopic findings and treatment of concomitant meniscal and cartilage injury. Surgeon documentation of articular cartilage injury was recorded, based on the modified Outerbridge classification.5,20,26,29 Meniscus injuries were classified by size, location, and partial versus complete tears, while treatment was recorded as not treated, repair, or extent of resection.8 Following surgery, each patient followed the same standardized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol.44,45,46

Completed data forms were mailed from each participating site to the data coordinating center. Data from both the patient and surgeon questionnaires were scanned with Teleform™ software (Cardiff Software, Inc., Vista, CA) utilizing optical character recognition, and the scanned data was verified and exported to a master database. A series of logical error and quality control checks were subsequently performed prior to data analysis.

Follow-Up

Two- and six-year follow-up was completed by mail with re-administration of the same questionnaire to each patient. Patients were also contacted by telephone to determine if any underwent additional surgery to either knee.

Quantitative Variables and Statistical Methods

To determine the association between independent (risk factor) variables and validated outcome measures, multivariable regression models were utilized (Table 1). Multivariable analysis was used to determine which baseline variables measured at the time of index ACL surgery were significant predictors of IKDC, KOOS, and Marx scores at 2 and 6 years after surgery. Longitudinal analysis was performed using proportional odds ordinal logistic regression to fit a single model for the 2-year and 6-year end points.41 The proportional odds model makes fewer distributional assumptions than ordinary regression. The dependent variables were treated as continuous and consisted of the IKDC (scored 0 [worst] to 100 [best]), KOOS five subscales (scored 0 [worst] to 100 [best]), and the Marx (scored 0 [low activity] to 16 [highest activity]). Independent patient covariates in the model included age at the time of surgery, gender, education level, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), smoking status (baseline and current), sport, competition level (amateur, high school, collegiate, professional), activity level as assessed using the Marx activity rating scale, and the baseline measure of the outcome (IKDC, KOOS, Marx). Follow-up time (calculated as the time from index surgery to the date that the patient completed their 2- and/or 6-year follow-up questionnaire) was included in the model, and treated as a continuous variable.

Table 1.

List of Modeling Variables

| Category | Variable | Levels |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Baseline Outcome Score | IKDC, KOOS (5 subscales), Marx | continuous |

|

| ||

| Patient Demographics | Age (years) | continuous |

| Gender | male, female | |

| Ethnicity | white, black, asian, other | |

| BMI | continuous | |

| Smoking status | never, quit, current | |

| Education level (years) | 1 - 16 | |

| Baseline activity level (Marx) | continuous | |

| Main sport | none, basketball, football, soccer, gymnastics, volleyball, baseball, skiing, other | |

| Competition level | none, recreational, amateur, high school, college, professional | |

|

| ||

| Surgical Technique | Reconstruction type | primary, revision |

| Graft type | autograft, allograft | |

| Graft source | BTB, hamstring, tibialis anterior/posterior, achilles tendon, ITB, other | |

| Previous ACLR on contralateral knee | no, yes | |

| Meniscal pathology | ||

| * medial | no tear, no treatment for tear, repair, 17% excised, 33% excised, 50% excised, >67% excised | |

| * lateral | no tear, no treatment for tear, repair, 17% excised, 33% excised, 50% excised, >67% excised | |

| * hoop stresses (medial) | intact, disrupted | |

| * hoop stresses (lateral) | intact, disrupted | |

| Articular cartilage pathology | ||

| * medial femoral condyle (MFC) | normal/grade 1, grade 2, grade 3, grade 4 | |

| * lateral femoral condyle (LFC) | normal/grade 1, grade 2, grade 3, grade 4 | |

| * medial tibial plateau (MTP) | normal/grade 1, grade 2, grades 3/4 | |

| * lateral tibial plateau (LTP) | normal/grade 1, grade 2, grades 3/4 | |

| * patella | normal/grade 1, grade 2, grades 3/4 | |

| * trochlea | normal/grade 1, grade 2, grades 3/4 | |

|

| ||

| Other Misc. Variables | Surgeon years of experience | continuous |

| Year of surgery | 2002, 2003, 2004 | |

| Follow-up time | 0, 2, 6 years (but treated as a continuous variable for each patient) | |

Independent surgical factors included surgeon experience (in years), any previous ACLR surgery performed on the contralateral knee (yes/no), primary vs. revision surgery, graft type (autograft vs. allograft), graft source (BTB, hamstring, tibialis anterior/posterior, achilles tendon, other), and year of surgery. Meniscal injuries were classified by size, location, partial versus complete tears, and treatment, categorized as not treated, repaired, or percent excised. At the time of ACLR, surgeons recorded the percentage of excision from both the posterior and anterior portions of the medial and lateral menisci. Excision options were categorized as none, 33%, 67%, or 100% excision for each segment (anterior and/or posterior). For this study, we used the largest excision for each segment. Articular cartilage variables were grouped by location to include the medial femoral condyle (MFC), lateral femoral condyle (LFC), medial tibial plateau (MTP), lateral tibial plateau (LTP), patella, and trochlea. Severity of articular cartilage degeneration in each location was categorized according to the modified Outerbridge classification and included normal, grade 1 (G1 – softening), grade 2 (G2 – fraying or fissures), grade 3 (G3 – partial thickness loss with fibrillation), or grade 4 (G4 – full thickness loss with exposed subchondral bone).5,26,29 Multifocal articular cartilage lesions within a region (MFC, LFC, MTP, LTP, patella, trochlea) were assessed by taking the highest Outerbridge grade. Multifocal cartilage lesions between compartments were treated independently. Similarly, when multifocal meniscal pathology was found within a region (medial, lateral), they were treated independently (up to 2 lesions).

Regarding clinically meaningful change in score, we utilized 11 points for the IKDC,11 8 points for the KOOS,33 and 2 points for the Marx activity scale. Linearity of covariates was not assumed and restricted cubic regression splines were utilized with the assumption of smoothed relationships. Multiple imputation was used for missing values for predictor variables as performed by the areglmpute function within the Hmisc package (http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/Hmisc) of R (free open-source statistical software; http://www.r-project.org).10,31

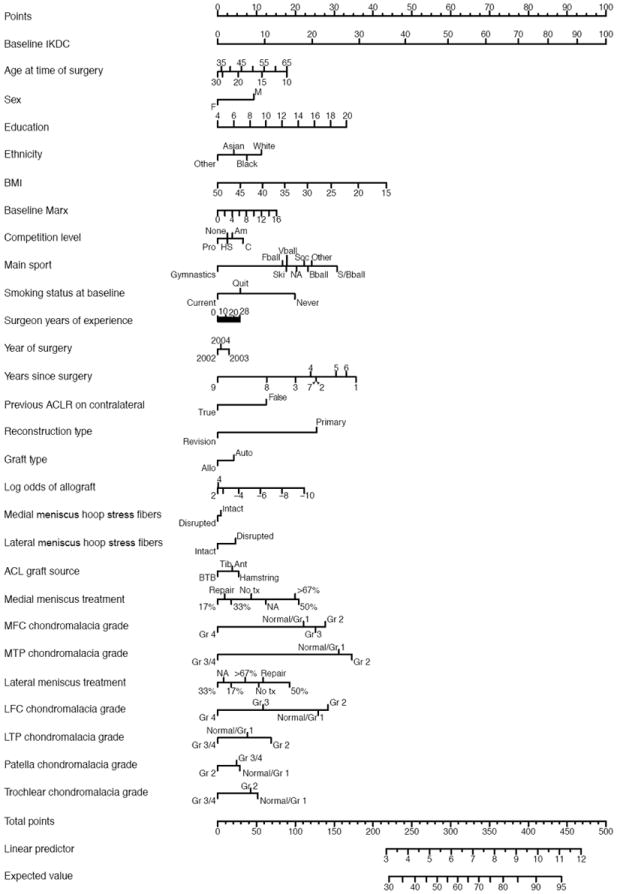

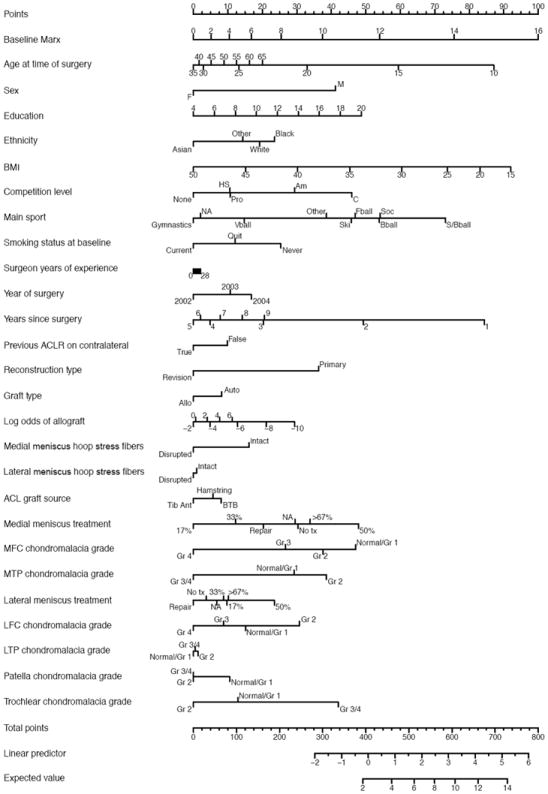

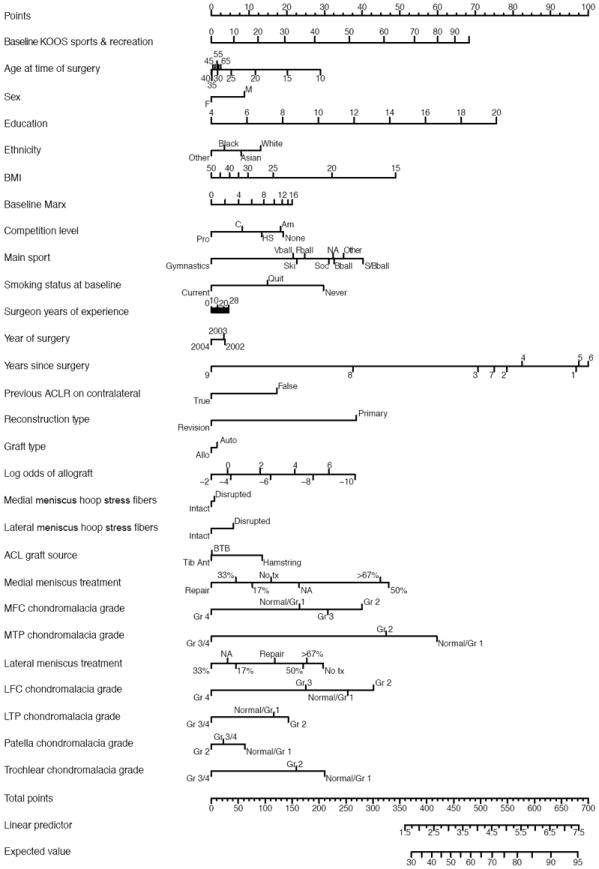

Nomograms were created to display the relationship between predictor variables and the outcomes, based on the fitted models. A nomogram can be used to estimate the mean response for individual patients as well as show the relationship between the different predictor variables and how this affects the response.

RESULTS

Study Population

A total of 1512 subjects met the study’s inclusion criteria and were included in our final enrollment (Figure 1). Of the initial 1512 subjects, at least one repeat questionnaire was obtained on 1411 (93%). Two-year follow-up was obtained on 1308 of 1512 (87%), and 6-year follow-up was obtained on 1307 of 1512 (86%).

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the analyzed cohort are provided in Table 2. Similarly, baseline and follow-up outcome scores for the IKDC, KOOS, and Marx are presented in Table 3. The study population was 56% male with a median age of 23 years (IQR: 17, 35), with 75% of the patients reporting a non-contact injury mechanism. Medial meniscal pathology was noted in 38% of subjects, with 19% of those undergoing partial excisions, 13% undergoing repairs, and 7% undergoing no treatment for their tears. Lateral meniscus pathology was noted in 46% of subjects, with 28% of the cohort undergoing partial excisions, 6% undergoing repairs, and 18% undergoing no treatment. Articular cartilage pathology by location included chondromalacia of each respective location as follows: MFC-25%, LFC-20%, MTP-6%, LTP-12%, patella-20%, and trochlea-9%. The most common treatment options performed on these articular cartilage surfaces were either no treatment or chondroplasty (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Patient and Surgical Characteristics

| N | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1411 | |

| males | 56% (785) | |

| females | 44% (626) | |

| Age (years) | 1411 | 17 23 35 |

| Education (years) | 1379 | 11 14 16 |

| Baseline Marx Activity level | 1398 | 8 12 16 |

| BMI | 1388 | 22.3 24.8 27.8 |

| Smoking Status | 1395 | |

| never | 81% (1123) | |

| quit | 10% (137) | |

| current | 10% (135) | |

| Ethnicity | 1405 | |

| asian | 4% (52) | |

| black | 7% (102) | |

| hispanic | 1% (18) | |

| other | 2% (28) | |

| white | 86% (1205) | |

| Main Sport | 1407 | |

| none | 8% (116) | |

| basketball | 22% (310) | |

| football | 11% (152) | |

| soccer | 14% (192) | |

| gymnastics | 1% (12) | |

| volleyball | 5% (70) | |

| baseball | 9% (125) | |

| skiing | 5% (71) | |

| other | 26% (359) | |

| Competition Level | 1405 | |

| none or recreational | 46% (649) | |

| amateur | 14% (193) | |

| high school | 28% (393) | |

| college | 10% (144) | |

| professional | 2% (26) | |

| Injury Mechanism | 1403 | |

| non-traumatic; gradual onset | 2% (25) | |

| non-traumatic; sudden onset | 4% (54) | |

| traumatic; non-contact | 76% (1060) | |

| traumatic; contact | 19% (264) | |

| Reconstruction Type | 1411 | |

| primary | 91% (1278) | |

| revision | 9% (133) | |

| Graft Type | 1411 | |

| autograft | 75% (1055) | |

| allograft | 25% (356) | |

| Previous ACLR on Contralateral Knee | 1411 | |

| no | 91% (1285) | |

| yes | 9% (126) | |

| Medial Meniscus Status | 1411 | |

| normal | 62% (879) | |

| partial tear | 9% (120) | |

| complete tear | 29% (412) | |

| Medial Meniscus Treatment | 1404 | |

| normal (no tear) | 61% (861) | |

| no treatment for tear | 7% (101) | |

| repair | 13% (177) | |

| excision | 19% (265) | |

| Lateral Meniscus Status | 1411 | |

| normal | 54% (766) | |

| partial tear | 13% (185) | |

| complete tear | 33% (460) | |

| Lateral Meniscus Treatment | 1404 | |

| normal | 49% (687) | |

| no treatment for tear | 18% (246) | |

| repair | 6% (82) | |

| excision | 28% (389) | |

| Medial Femoral Condyle (MFC) Chondrosis | 1411 | |

| normal | 75% (1058) | |

| grade 1 | 2% (26) | |

| grade 2 | 14% (196) | |

| grade 3 | 7% (97) | |

| grade 4 | 2% (34) | |

| MFC Treatment | ||

| none | 17% (238) | |

| chondroplasty | 11% (159) | |

| microfracture | 1% (15) | |

| abrasion arthroplasty | <1%(4) | |

| mosiacplasty | <1%(4) | |

| other | <1%(2) | |

| Lateral Femoral Condyle (LFC) Chondrosis | 1411 | |

| normal | 80% (1134) | |

| grade 1 | 3% (39) | |

| grade 2 | 11% (161) | |

| grade 3 | 4% (61) | |

| grade 4 | 1% (16) | |

| LFC Treatment | ||

| none | 20% (277) | |

| chondroplasty | 5% (76) | |

| microfracture | <1%(6) | |

| abrasion arthroplasty | <1%(2) | |

| mosiacplasty | <1%(1) | |

| other | 0% (0) | |

| Medial Tibial Plateau (MTP) Chondrosis | 1411 | |

| normal | 94% (1330) | |

| grade 1 | 1% (10) | |

| grade 2 | 3% (48) | |

| grade 3 | 1% (16) | |

| grade 4 | <1% (7) | |

| MTP Treatment | ||

| none | 5% (75) | |

| chondroplasty | 1% (14) | |

| microfracture | 0% (0) | |

| abrasion arthroplasty | 0% (0) | |

| mosiacplasty | 0% (0) | |

| other | 0% (0) | |

| Lateral Tibial Plateau (LTP) Chondrosis | 1411 | |

| normal | 88% (1237) | |

| grade 1 | 3% (48) | |

| grade 2 | 7% (99) | |

| grade 3 | 1% (18) | |

| grade 4 | 1% (9) | |

| LTP Treatment | ||

| none | 13% (179) | |

| chondroplasty | 3% (36) | |

| microfracture | <1%(1) | |

| abrasion arthroplasty | <1%(1) | |

| mosiacplasty | 0% (0) | |

| other | 0% (0) | |

| Patella Chondrosis | 1411 | |

| normal | 80% (1130) | |

| grade 1 | <1% (7) | |

| grade 2 | 12% (170) | |

| grade 3 | 7% (101) | |

| grade 4 | <1% (3) | |

| Patella Treatment | ||

| none | 11% (154) | |

| chondroplasty | 11% (156) | |

| microfracture | 0% (0) | |

| abrasion arthroplasty | 0% (0) | |

| mosiacplasty | 0% (0) | |

| other | 0% (0) | |

| Trochlear Chondrosis | 1411 | |

| normal | 91% (1287) | |

| grade 1 | <1% (3) | |

| grade 2 | 5% (73) | |

| grade 3 | 3% (42) | |

| grade 4 | <1% (6) | |

| Trochlear Treatment | ||

| none | 6% (87) | |

| chondroplasty | 3% (46) | |

| microfracture | <1%(3) | |

| abrasion arthroplasty | <1%(1) | |

| mosiacplasty | 0% (0) | |

| other | 0% (0) |

a b c represent the lower quartile a, the median b, and the upper quartile c for continuous variables.

N is the number of non–missing values.

Numbers after percents are frequencies.

Table 3.

Median (25%, 75% quartile) Outcome Scores over Time

| Scale | Baseline-T0 | 2 Year | 6 Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKDC | 0-100 | 53 (41,64) | 85 (74,92) | 86 (74,93) |

| KOOS symptoms | 0-100 | 71 (57,82) | 86 (75,93) | 89 (75,96) |

| KOOS pain | 0-100 | 75 (64,89) | 92 (83,97) | 94 (86,100) |

| KOOS ADL | 0-100 | 88 (74,97) | 99 (93,100) | 99 (94,100) |

| KOOS sports/rec | 0-100 | 55 (30,80) | 85 (70,95) | 85 (70,100) |

| KOOS knee-related quality of life | 0-100 | 38 (25,50) | 75 (56,88) | 75 (63,94) |

| Marx Activity Level | 0-16 | 12 (8,16) | 9 (4,13) | 7 (3,12) |

Summary of Significant Predictors

Table 4 displays the significant articular cartilage and meniscal predictors identified for each individual outcome score following multivariable logistic regression. Table 5 displays the odds ratios for categorical comparisons amongst meniscal and articular cartilage pathology as graded at the time of surgery for each outcome score. Table 6 displays the odds ratios for baseline scores, patient demographics, surgical technique, and miscellaneous factors (as noted above). Nomograms displaying the relationships between baseline predictor variables of the IKDC, KOOS, and Marx activity level and their expected 6-year outcome scores are shown in Figures 2-5.

Table 4.

Significant Predictors of Each Outcome Scale at 6 Years (p values)

| Structure | IKDC | KOOS

|

Marx | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Pain | ADL | Sports/Rec | QoL | |||

|

| |||||||

| Meniscus | |||||||

| Medial | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.025 | ||

| Lateral | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.023 | |

|

| |||||||

| Articular Cartilage | |||||||

| MFC | 0.011 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.01 | |||

| LFC | 0.002 | 0.03 | |||||

| MTP | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.025 | ||

| LTP | 0.034 | ||||||

| Patella | |||||||

| Trochlea | 0.032 | ||||||

Table 5.

Significant Odds Ratios (95% Cl) for Meniscus and Articular Cartilage Variables

| Structure | Comparison | Worse Outcome | IKDC | KOOS | Marx | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Pain | ADL | Sports/Rec | QoL | ||||||

| MENISCUS | Medial | No tear vs. repair | repair | 0.68 (0.52-0.89) | 0.62 (0.47-0.83) | 0.68 (0.52-0.88) | 0.71 (0.53-0.94) | 0.65 (0.50-0.84) | 0.63 (0.49-0.83) | |

| No tear vs. 17% excised | 17% excised | 0.64 (0.46-0.90) | 0.57 (0.38-0.86) | |||||||

| No tear vs. 33% excised | 33% excised | 0.73 (0.54-0.99) | ||||||||

| No tear vs. 50% excised | no tear | 2.11 (1.23-3.64) | ||||||||

| Lateral | No tear vs. no tx for tear | no tear | 1.38 (1.07-1.77) | 1.55 (1.21-1.99) | 1.64 (1.29-2.09) | 1.55 (1.20-2.01) | 1.60 (1.26-2.03) | 1.41 (1.10-1.81) | ||

| No tear vs. repair | no tear | 1.56 (1.07-2.28) | ||||||||

| No tear vs. 50% excised | no tear | 1.84 (1.07-3.15) | 1.95 (1.13-3.38) | 2.18 (1.21-3.93) | ||||||

| No tear vs. 67% excised | no tear | 1.70 (1.00-2.87) | ||||||||

| ARTICULAR CARTILAGE | MFC | Normal/Gl vs. G4 | G4 | 0.45 (0.26-0.80) | 0.46 (0.25-0.83) | 0.40 (0.23-0.71) | 0.47 (0.24-0.92) | |||

| Normal/Gl vs. G2 | Normal/Gl | 1.36 (1.02-1.82) | ||||||||

| LFC | Normal/Gl vs. G3 | G3 | 0.60 (0.39-0.92) | 0.64 (0.42-1.00) | ||||||

| Normal/G1 vs. G4 | G4 | 0.40 (0.21-0.74) | 0.51 (0.28-0.97) | 0.42 (0.20-0.89) | ||||||

| MTP | G2 vs. G3/4 | G3/4 | 0.29 (0.13-0.63) | 0.30 (0.12-0.80) | 0.39 (0.17-0.90) | 0.39 (0.19-0.78) | ||||

| LTP | Normal/Gl vs. G2 | Normal/Gl | 1.47 (1.05-2.08) | |||||||

| G2 vs. G3/4 | G3/4 | 0.48 (0.25-0.95) | ||||||||

| Patella | ||||||||||

| Trochlea | Normal/Gl vs. G3/4 | G3/4 | 0.49 (0.28-0.85) | |||||||

key: shaded value indicates result was counter-intuitive to initial hypothesis.

Table 6.

Significant Odds Ratios (95% CI) for Secondary Variables in Model

| Comparison | Worse Outcome | IKDC | KOOS | Marx | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Pain | ADL | Sports/Rec | QoL | |||||

| Baseline Outcome Score | lower T0 score | 2.27 (1.80-2.87) | 2.11 (1.67-2.66) | 2.28 (1.81-2.87) | 2.61 (2.09-3.26) | 2.13 (1.67-2.70) | 1.58 (1.27-1.98) | 3.33 (2.51-4.42) | |

| Patient Demographics | |||||||||

| Age | 15 vs. 35 yrs | older age | 0.38 (0.24-0.62) | ||||||

| Gender | male vs. female | females | 0.72 (0.58-0.88) | 0.51 (0.42-0.62) | |||||

| BMI | 23 vs. 28 | higher BMI | 0.79 (0.69-0.91) | 0.88 (0.78-1.00) | 0.84 (0.73-0.95) | 0.79 (0.69-0.91) | 0.82 (0.72-0.93) | 0.86 (0.75-0.98) | 0.83 (0.73-0.95) |

| Smoking status | never vs. quit | quit smoking | 0.61 (0.44-0.83) | 0.65 (0.47-0.91) | 0.58 (0.42-0.80) | 0.57 (0.42-0.77) | 0.69 (0.50-0.93) | ||

| never vs. current | current smoker | 0.49 (0.36-0.67) | 0.58 (0.42-0.79) | 0.58 (0.41-0.83) | 0.51 (0.37-0.70) | 0.58 (0.41-0.81) | 0.63 (0.45-0.87) | 0.66 (0.50-0.89) | |

| Education level | 12 vs. 16 yrs | lower education | 1.35 (1.11-1.64) | 1.48 (1.21-1.81) | 1.39 (1.14-1.70) | 1.57 (1.27-1.93) | 1.42 (1.16-1.74) | 1.30 (1.06-1.59) | 1.22 (1.02-1.45) |

| Main sport | none vs. basketball | none | 0.43 (0.28-0.66) | ||||||

| volleyball vs. basketball | volleyball | 0.53 (0.37-0.77) | |||||||

| baseball vs. basketball | basketball | 1.52 (1.06-2.19) | 1.49 (1.06-2.11) | ||||||

| other vs. basketball | other | 0.78 (0.62-0.99) | |||||||

| Competition level | None/recvs. amateur | none/rec | 1.61 (1.26-2.05) | ||||||

| None/rec vs. college | none/rec | 2.10 (1.51-2.93) | |||||||

| Surgical Technique | |||||||||

| Reconstruction type | primary vs. revision | revision | 0.40 (0.28-0.57) | 0.55 (0.40-0.77) | 0.49 (0.36-0.68) | 0.50 (0.35-0.72) | 0.49 (0.34-0.70) | 0.39 (0.27-0.56) | 0.56 (0.40-0.78) |

| Graft source | BTB vs. hamstring | BTB (KOOS symptoms) hamstring (KOOS sports/rec) | 0.71 (0.51-1.00) | 1.28 (1.02-1.60) | |||||

| Previous ACLR on contra knee | no vs. yes | yes | 0.64 (0.48-0.85) | 0.70 (0.51-0.95) | 0.72 (0.53-0.98) | 0.71 (0.53-0.95) | |||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||||

| Follow-up time | 2 vs. 6 yrs | 2 yrs (IKDC, KOOS) 6 yrs (Marx) | 1.32 (1.04-1.67) | 1.63 (1.28-2.07) | 1.63 (1.26-2.11) | 1.66 (1.26-2.19) | 1.50 (1.17-1.91) | 1.47 (1.15-1.86) | 0.45 (0.35-0.58) |

| Baseline Marx | lower Marx score | 1.32 (1.00-1.75) | |||||||

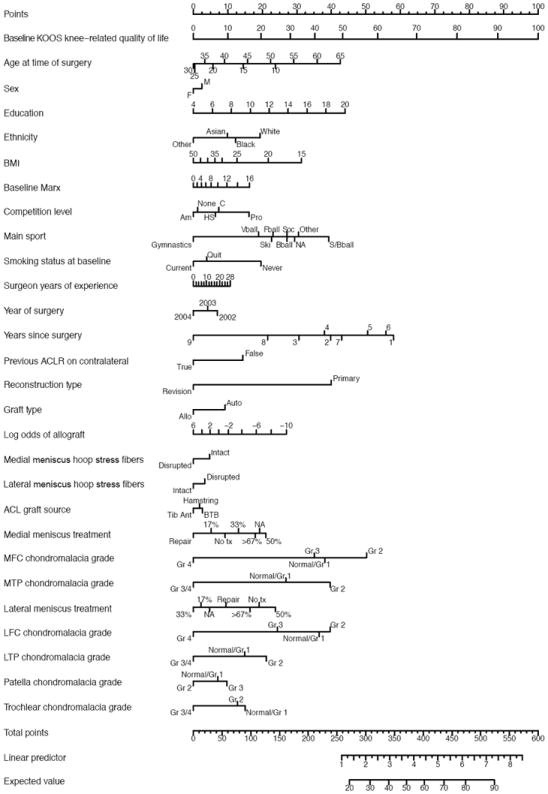

Figure 2.

Nomogram for IKDC model

The outcome score, individualized for each patient based upon presenting characteristics, can be predicted by summing the point total for each variable on the left. To use the nomogram, place a ruler or straight edge vertically over each individual predictor listed on the left hand column, and use the top line (“Points”) to record the corresponding points assigned for that value. Repeat for each predictor variable listed along the left hand column.

- Baseline IKDC score (50) = 59 points

- Age at the time of surgery (20 yrs) = 5 pts

- Sex (male) = 9 pts

- Education (16 years) = 25 pts

- Ethnicity (white) = 11 pts

- BMI (25) = 29 pts

- Baseline Marx (12) = 11 pts

- Competition level (high school) = 2.5 pts

- Main sport (football) = 17 pts

- Smoking status at baseline (current) = 0 pts

- Surgeon years of experience (10 yrs) = 2 pts

- Year of surgery (2004) = 1 pt

- Years since surgery (3 yrs) = 20 pts

- Previous ACLR on contralateral knee (false) = 12.5 pts

- Reconstruction type (revision) = 0 pts

- Graft type (autograft) = 4 pts

- Log odds on allograft (2) = 0 pts

- Medial meniscus hoop stress fibers (intact) = 1 pt

- Lateral meniscus hoop stress fibers (intact) = 0 pts

- ACL graft source (hamstring) = 5 pts

- Medial meniscus treatment (repair) = 2 pts

- MFC chondromalacia grade (grade 2) = 27.5 pts

- MTP chondromalacia grade (normal/grade 1) = 31 pts

- Lateral meniscus treatment (no treatment) = 10 pts

- LFC chondromalacia grade (grade 4) = 0 pts

- LTP chondromalacia grade (normal/grade 1) = 7.5 pts

- Patella chondromalacia grade (grade 2) = 0 pts

- Trochlear chondromalacia grade (grade 2) = 8 pts

Manually sum these points, and using the ruler/straight edge, transfer the sum to the “Total Points” axis to determine the corresponding “Expected Value” at 6 years.

For our hypothetical patient, the sum of the above variables equals 300 total points. Drawing a vertical line down from the “Total Points” mark at 300 to the “Expected Value” line at the bottom of the nomogram would correspond to a predicted 6 year IKDC value of 57.

Figure 5.

Nomogram for Marx Activity Rating Scale model

The outcome score, individualized for each patient based upon presenting characteristics, can be predicted by summing the point total for each variable on the left. To complete the nomogram, the patient’s result is marked for each specific variable, and the point value based upon the “Points” line at the top of the scale is recorded. The sum of all of the points for each variable is then placed on the “Total Points” line at the bottom of the figure. The predicted outcome score at 6 years for the Marx activity level is then read by drawing a perpendicular line below. BMI=body mass index; MFC=medial femoral condyle; LFC=lateral femoral condyle; MTP=medial tibial plateau; LTP=lateral tibial plateau.

IKDC Outcomes

For the IKDC, both medial and lateral meniscal pathology and articular cartilage injury of the MFC, LFC, and MTP were significant predictors (Tables 4 and 5). For the medial meniscus, both repair and partial excision (17% excised, 33% excised) portended a lower outcome score when compared to absence of medial meniscus pathology (Table 5). Conversely, for the lateral meniscus, untreated tears and partial excisions (>50%) predicted a higher score when compared to absence of meniscal pathology. Regarding articular cartilage pathology, grade 3 and grade 4 changes predicted a worse score when compared to lower grades (normal, grade 1, and/or grade 2) of cartilage injury to the MFC, LFC, and MTP regions. For patient demographics, female gender, higher BMI, previous smokers, current smokers, lower education level, lower baseline activity level, and lower baseline IKDC score predicted significantly lower outcome scores (Table 6).

For surgical technique, revision surgery and previous ACLR on the contralateral knee predicted worse outcome scores (Table 6). Additionally, IKDC scores increased (improved) when comparing baseline to time 2 years to 6 years post-surgery (Table 3).

KOOS Outcomes

For the KOOS, both medial and lateral meniscal pathology and articular cartilage injury of the MFC, LFC, MTP, LTP and trochlea were significant predictors for various subscales (Tables 4 and 5). For the medial meniscus, repair predicted a worse outcome for all subscales as compared to absence of meniscal pathology (Table 5). For the KOOSsymptoms subscale, a lesser amount excised (17% excised) predicted a worse score when compared to no tear. However, for the KOOSpain subscale, a larger portion excised (50% excised) predicted a better score when compared to no tear. For the lateral meniscus, untreated tears, repairs, and larger portions excised (50% excised, 67% excised) predicted a higher or improved score when compared to absence of meniscal pathology for select subscales. Regarding articular cartilage pathology, grade 3 and grade 4 changes predicted a worse score when compared to lower grades (normal, grade 1, and/or grade 2) of cartilage injury to the MFC, LFC, MTP, LTP, and trochlea for the various subscales with the exception of the KOOSsports/rec However, when comparing normal/grade 1 versus grade 2 changes, grade 2 changes actually predicted better outcome scores for the MFC (KOOSsports/rec) and the LTP (KOOSpain). For patient demographics, higher BMI, previous smokers, current smokers, lower education level, and lower baseline KOOS scores predicted significantly lower outcome scores (Table 6). A primary sport of basketball as compared to baseball predicted a lower score for the KOOSsymptoms and KOOSpain subscales. For surgical technique, revision surgery and previous ACLR on the contralateral knee predicted worse outcome scores. For the KOOSsymptoms subscale, BTB graft predicted a lower score when compared to hamstring. Conversely, for the KOOSsports/rec subscale, BTB graft predicted a higher score when compared to hamstring. For all KOOS subscales, scores increased when comparing baseline to time 2 years to 6 years post-surgery (Table 3).

Marx Activity Level Outcomes

For the Marx activity score, meniscal pathology and articular cartilage injury were not significant predictors with the exception of the damage on the MFC (Tables 4 and 5). Grade 4 cartilage changes of the MFC predicted a significantly lower score (decreased activity level) when compared to normal/grade 1 findings (Table 5). For patient demographics, older age, female gender, higher BMI, current smokers, lower education level, and lower baseline Marx scores predicted lower activity scores (Table 6). Inter-sport comparisons also yielded significant predictors as noted in Table 6. Lower competition levels predicted a worse activity score when compared to amateur or collegiate athletic status. For surgical technique, revision surgery predicted lower activity scores. Marx scores decreased when comparing initial baseline to time 2 years to 6 years post-surgery (Table 3).

For the IKDC, KOOS (all subscales), and the Marx, a lower baseline score predicted a worse outcome score at time 6 years.

DISCUSSION

The major findings to come from this study are that articular cartilage lesions and meniscal tears/treatment present at the time of an ACL surgery have a significant effect on patient-reported outcomes 2 and 6 years following an ACLR. Utilizing a comprehensive logistic regression model with sufficient sample size, we were able to construct a multivariable model that incorporated a variety of potential risk factors, so as to determine which variables drive outcomes following ACLR. Specifically, we observed the following: patients without lateral meniscus tears did worse than those with untreated tears, partial excisions, and repairs. Medial meniscus repairs predicted worse IKDC and KOOS scores compared to those without tears. Small partial meniscectomies (<33%) on the medial meniscus fared worse, but conversely, larger excisions on the medial or lateral menisci (>50%) improved prognosis. Grade 3 or 4 articular cartilage lesions in various compartments (excluding patella) significantly reduced IKDC and KOOS scores at 6 years. The sole significant meniscus and articular cartilage predictor of reduced Marx activity was the presence of a grade 4 lesion on the MFC.

Analogous to our previous modeling based on a single enrollment year (2002) with 83% follow-up at 6 years, we found that subjects having higher BMI, lower education level, smokers, and revision ACL surgery were significant predictors of poorer KOOS, IKDC, and Marx outcomes. Furthermore, it appears that the patients’ pre-operative (baseline) outcome scores are extremely important predictors of their post-operative outcome scores.

There are two fundamental differences in this study as compared to our prior modeling reported in 2011.39 First, we increased the sample size from 400 to 1400 by including two additional enrollment years, thereby increasing statistical power. Second, our modeling changed from linear multivariable modeling (taking baseline T0 risk factors to 6-year outcomes) to logistic multivariable modeling, which incorporates both 2- and 6-year follow-up into predicting which baseline risk factors are significant in the model. This statistical approach utilizes all of the follow-up data obtained on patients.

This 3-fold increase in sample size enabled us to identify that both articular cartilage lesions and meniscus injuries and treatment significantly influence the 6-year KOOS and IKDC scores. However, despite these efforts, the observed findings still have limitations. We are not yet able to fully model meniscus and articular cartilage interactions, which based upon our knowledge are likely important and represent an area of future study. Furthermore, we would have preferred to limit the collapsed meniscus variable levels from percentage of excision to more traditional clinical terms (e.g., posterior horn central third, central two thirds, etc.), but only a further increase in sample size could enable this. Finally, we only classified the grade of articular cartilage injury and were not able to fully utilize our database, which includes a measure of lesion size, based upon our previous inter-rater agreement studies on both meniscus8 and articular cartilage.20 Further sample size of 2-3 years (~1500 additional ACLR) would resolve this dilemma. However our current study modeling and analysis is the most comprehensive to date in the literature.

The next most comparable multivariable modeling of ACLR outcomes are from the Swedish and Norwegian National Knee Ligament Registries reported in 2012 and 2013.1,37 Barenius and colleagues dichotomized their outcomes into “treatment failure” and “treatment success” as determined by a pre-specified KOOS score.1 The authors did not identify articular cartilage injuries as a risk factor for treatment failures. In contrast, we observed that grade 3/4 chondral injury significantly predicted worse KOOS and IKDC scores. Our analysis was more specific in that we included grading (1-4) of the lesions at six different intra-articular locations. Conversely, the Swedish group only classified articular cartilage pathology as “presence” or “absence” within the knee. Interestingly, the most controversial finding from our study was also seen in Swedish study,1 as medial meniscus repair was found to be a predictor of worse outcome or treatment failure. In our study this was only true for medial meniscus repair, as lateral meniscus repair was successful when compared to normal meniscus.

The finding that small untreated tears of the lateral meniscus is a predictor of better outcomes when compared to a normal lateral meniscus has been a consistent finding in all of our prior analyses and again is confirmed here. One hypothesis is that during the rotational subluxation of the lateral compartment at the time of injury, the energy is either distributed to the meniscus or the articular cartilage. Thus it seems perhaps better to absorb the load manifested in a small lateral meniscus tear as opposed to an articular cartilage lesion. Similarly, the question of why slightly larger lateral meniscal excisions do better than no tear could be explained by altered kinematics following ACLR, with decreased loading in the lateral compartment. An alternative hypothesis of this unexpected finding might be that it’s an indicator of a more favorable injury mechanism. Our current study cannot answer these extremely important questions and establishes a foundation for future clinical research. In summary, the current accepted treatment recommendations for lateral meniscus tears appear to be successful in optimizing ACLR outcomes. These include leaving small tears alone, repairing large tears in the vascular zone and excising unstable tears in the avascular zone.

The finding of medial meniscus repair predicting worse outcomes on both the KOOS and IKDC is not an unexpected surprise. Our finding is corroborated in the published Swedish database study as medial meniscus repair was a risk factor for “treatment failure.”1 In addition, Shelbourne has previously suggested that medial meniscus tears function differently than lateral meniscus tears in the ACL injured population.38 The failure of medial repairs to improve outcomes is in direct contrast to the lateral meniscus, where repair had similar outcomes to normal meniscus. There are several factors that could perhaps account for the difference in success. First, the medial meniscus has decreased mobility, decreased vascularity, and increased biomechanical load as compared to the lateral meniscus. It also acts as a secondary restraint to anterior tibial translation. Thus repair of the medial meniscus is subject to a more stringent test of the repair compared with a lateral repair. The short-term clinical success, defined as no re-operation for clinical symptoms, has been shown to be excellent with 96% success at 2-year follow-up for medial meniscus repairs.40 However, a recent systematic review of 5-year outcomes shows 24% (range of 17-37%) had re-operation for failed medial meniscus repair,25 indicating that these repairs are failing over time. If the repairs are failing clinically, then the meniscus cannot protect the articular cartilage nor improve clinical outcomes as measured by KOOS and IKDC. Further research is needed not only to better define the likelihood of healing but also to document the clinical improvement as measured by the KOOS and IKDC. Our planned 10-year follow-up and the planned addition of another 3 years (~1500 additional ACLR) should further shed light on meniscus repairs performed between 2002 and 2008. Based upon the current study and Barenius’ findings of worse outcomes with medial meniscus repair,1 we are not advocating any change in clinical practice, but are suggesting that our management of medial meniscus tears at the time of ACLR needs more focused research.

In the current study, the presence of grade 3 or 4 articular cartilage lesions predicted worse outcomes in the majority of knee articular surfaces. Given the limited number of grade 3 and grade 4 lesions, we could not model treatment options, including no treatment, debridement, and cartilage restorative procedures. In the future, additional sample size may allow us to model treatment options. We recommend that treatment strategies be explored to restore biomechanical function of articular cartilage and ideally delay further degenerative changes.

In identifying predictors of Marx activity level, only a grade 4 change on the medial femoral condyle predicted a worse or declining activity level. No other level of chondromalacia or meniscus injury influenced activity at 6-year follow-up. Similar to our previous studies, we again found predictors including age, gender, BMI, smoking, educational status, time from surgery, and revision ACLR which all significantly influenced future activity. In addition, we also were able to model and show that both type of main sport and competition level influenced future activity.

A limitation of this study is that it is questionnaire-based, with lack of structural imaging (radiological or MRI evaluation) to confirm the status of the articular cartilage and meniscus at final follow-up. The size and degree of chondral lesion and the extent of more diffuse degenerative changes, such as joint space narrowing, if any, would be helpful in terms of elucidating the underlying biologic course of the validated patient-reported outcomes. With regard to meniscus, structural integrity is likely a relevant variable, particularly for repairs. Furthermore, 6 years of follow-up is likely too short a time period in order to see long-term degenerative changes of the knee joint. This does not detract from the significance of our findings but stresses the need for longer-term follow-up with future imaging.

In summary, to assist clinically in patient counseling and predict the future IKDC, KOOS subscales, or Marx, the modeled variables should be entered into the respective nomograms presented. Our most comprehensive modeling of ACLR patient-reported outcomes informs us that the current treatment strategy for lateral meniscus optimizes outcomes, grade 3/4 chondral injury is a potentially modifiable variable that can be treated and current management of medial meniscus tears does not show the anticipated effect on clinical outcomes. Clearly many more questions are generated by the data and require more focused research based on prognostic risk factors. Additional 6-year follow-up and planned 10-year follow-up will assist in clarifying risk factors and treatment recommendation, but more translational and regenerative strategies are needed for articular cartilage and medial meniscus injuries.

CONCLUSIONS

Both articular cartilage injury and meniscal tears/treatment at the time of ACLR were significant predictors of both IKDC and KOOS scores 6 years following ACLR. Similarly, having a grade 4 MFC lesion significantly reduced a patient’s Marx activity level score at 6 years. More research is needed to better understand the structural changes that occur in the articular cartilage and meniscus after ACLR that likely contribute to these findings, and how to optimize our clinical management of these concomitant injuries to improve outcomes.

Figure 3.

Nomogram for KOOS Sports & Recreation subscale model

The outcome score, individualized for each patient based upon presenting characteristics, can be predicted by summing the point total for each variable on the left. To complete the nomogram, the patient’s result is marked for each specific variable, and the point value based upon the “Points” line at the top of the scale is recorded. The sum of all of the points for each variable is then placed on the “Total Points” line at the bottom of the figure. The predicted outcome score at 6 years for the KOOSsports/rec subscale is then read by drawing a perpendicular line below. BMI=body mass index; MFC=medial femoral condyle; LFC=lateral femoral condyle; MTP=medial tibial plateau; LTP=lateral tibial plateau.

Figure 4.

Nomogram for KOOS Knee-Related Quality of Life subscale model

The outcome score, individualized for each patient based upon presenting characteristics, can be predicted by summing the point total for each variable on the left. To complete the nomogram, the patient’s result is marked for each specific variable, and the point value based upon the “Points” line at the top of the scale is recorded. The sum of all of the points for each variable is then placed on the “Total Points” line at the bottom of the figure. The predicted outcome score at 6 years for the KOOSqol subscale is then read by drawing a perpendicular line below. BMI=body mass index; MFC=medial femoral condyle; LFC=lateral femoral condyle; MTP=medial tibial plateau; LTP=lateral tibial plateau.

What is known about the subject

The presence of meniscal tears and/or chondral lesions has significant effects on the increased incidence of radiographic osteoarthritis in ACL injured patients.

What this study adds to existing knowledge

Articular cartilage and meniscal pathology at the time of ACL reconstruction were found to be significant risk factors on IKDC, KOOS, and Marx activity level outcomes 6 years following an ACLR. These results will aid physician counseling regarding an individual patient’s prognosis after ACLR, provide the highest level of evidence for physician decision making, and identify future modifiable risk factors to improve ACLR outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This project was partially funded by grant number 5R01 AR053684 (K.P.S.) and 5K23 AR052392 (W.R.D.) from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and by grant number 5U18 HS016075 (R.G.M.) from the Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics (Agency of Health Research and Quality). This project was partially supported by CTSA award No. UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. The project was also supported by the Vanderbilt Sports Medicine Research Fund. Vanderbilt Sports Medicine received unrestricted educational gifts from Smith & Nephew Endoscopy and DonJoy Orthopaedics.

We wish to thank the following additional Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) members who provided constructive reviews on the manuscript: Robert H. Brophy, MD (Washington University School of Medicine at Barnes-Jewish Hospital); Morgan H. Jones, MD (Cleveland Clinic Foundation); David C. Flanigan, MD, Robert A. Magnussen, MD (The Ohio State University).

We also thank the following research coordinators, analysts and support staff from the Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) sites, whose efforts related to regulatory, data collection, subject follow-up, data quality control, analyses, and manuscript preparation make this consortium possible: Kristen Banjac, Breanna Beck, Lynn Borzi, Julia Brasfield, Maxine Cox, Lisa Hegemier, Michelle Hines, Leah Schmitz (Cleveland Clinic Foundation); Angela Pedroza, Kari Stammen, Rose Backs (The Ohio State University); Carla Britton, Catherine Fruehling-Wall, Patty Stolley (University of Iowa); Christine Bennett, John Gines, Paula Langner (University of Colorado); Linda Burnworth, Robyn Gornati, Amanda Haas (Washington University in St. Louis); Brian Boyle, Patrick Grimm, Kaitlynn Lillemoe, Lana Verkuil (Hospital for Special Surgery); John Shaw, Suzet Galindo-Martinez, Zhouwen Liu, Thomas Dupont, Erica Scaramuzza and Lynn Cain (Vanderbilt University).

References

- 1.Barenius B, Forssblad M, Engstrom B, Eriksson K. Functional recovery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, a study of health-related quality of life based on the Swedish National Knee Ligament Register. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(4):914–27. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borchers JR, Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Huston LJ, Spindler KP, Wright RW on behalf of the MOON Consortium and the MARS Group. Intra-articular findings in primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a comparison of the MOON and MARS study groups. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1889–93. doi: 10.1177/0363546511406871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brophy RH, Schmitz L, Wright RW, Dunn WR, Parker RD, Andrish JT, McCarty EC, Spindler KP. Return to play and future ACL injury risk after ACL reconstruction in soccer athletes from the Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) group. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2517–22. doi: 10.1177/0363546512459476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claes S, Hermie L, Verdonk R, Bellemans J, Verdonk P. Is osteoarthritis an inevitable consequence of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012 Oct 26; doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2251-8. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curl WW, Krome J, Gordon ES, Rushing J, Smith BP, Poehling GG. Cartilage injuries: a review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(4):456–60. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn WR, Spindler KP, Amendola A, et al. Which preoperative factors, including bone bruise, are associated with knee pain/symptoms at index anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR)? A Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) ACLR cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(9):1778–87. doi: 10.1177/0363546510370279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn WR, Spindler KP. MOON Consortium. Predictors of activity level 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR): a Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) ACLR cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):2040–50. doi: 10.1177/0363546510370280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunn WR, Wolf BR, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Kaeding C, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Wright RW, Spindler KP. Multirater agreement of arthroscopic meniscal lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(8):1937–40. doi: 10.1177/0363546504264586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerhard P, Bolt R, Dück K, Mayer R, Friederich NF, Hirschmann MT. Long-term results of arthroscopically assisted anatomical single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using patellar tendon autograft: are there any predictors for the development of osteoarthritis? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(4):957–64. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2001-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrell FE., Jr rms Regression Modeling Strategies [Internet] 2011 Available from: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rms.

- 11.Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF. Development and validation of health-related quality of life measures for the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;402:95–109. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, et al. Development and validation of the international knee documentation committee subjective knee form. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):600–13. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290051301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, et al. Responsiveness of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1567–73. doi: 10.1177/0363546506288855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen RP, DuMée AW, van Valkenburg J, Sala HA, Tseng CM. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with 4-strand hamstring autograft and accelerated rehabilitation: a 10-year prospective study on clinical results, knee osteoarthritis and predictors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012 Oct 19; doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2234-9. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaeding CC, Aros B, Pedroza A, Pifel E, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Dunn WR, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Wright RW, Spindler KP. Allograft versus autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Predictors of failure from a MOON prospective longitudinal cohort. Sports Health. 2011;3(1):73–81. doi: 10.1177/1941738110386185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keays SL, Newcombe PA, Bullock-Saxton JE, Bullock Ml, Keays AC. Factors involved in the development of osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(3):455–63. doi: 10.1177/0363546509350914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowalchuk DA, Harner CD, Fu FH, Irrgang JJ. Prediction of patient-reported outcome after single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(5):457–63. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnussen RA, Granan LP, Dunn WR, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Brophy R, Carey JL, Flanigan D, Huston LJ, Jones M, Kaeding CC, McCarty EC, Marx RG, Matava MJ, Parker RD, Vidal A, Wolcott M, Wolf BR, Wright RW, Spindler KP, Engebretsen L. Cross-cultural comparison of patients undergoing ACL reconstruction in the United States and Norway. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(1):98–105. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0919-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnussen RA, Mansour AA, Carey JL, Spindler KP. Meniscus status at anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction associated with radiographic signs of osteoarthritis at 5- to 10-year follow-up: a systematic review. J Knee Surg. 2009;22(4):347–57. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marx RG, Connor J, Lyman S, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Kaeding C, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Wright RW, Spindler KP. Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network. Multirater agreement of arthroscopic grading of knee articular cartilage. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(11):1654–7. doi: 10.1177/0363546505275129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marx RG, Stump TJ, Jones EC, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Development and evaluation of an activity rating scale for disorders of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):213–8. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290021601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCullough KA, Phelps KD, Spindler KP, Matava MJ, Dunn WR, Parker RD, MOON Group, Reinke EK. Return to high school- and college-level football after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2523–9. doi: 10.1177/0363546512456836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melton JT, Murray JR, Karim A, Pandit H, Wandless F, Thomas NP. Meniscal repair in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a long-term outcome study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(10):1729–34. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray JR, Lindh AM, Hogan NA, Trezies AJ, Hutchinson JW, Parish E, Read JW, Cross MV. Does anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction lead to degenerative disease? Thirteen- year results after bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(2):404–13. doi: 10.1177/0363546511428580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nepple JJ, Dunn WR, Wright RW. Meniscal repair outcomes at greater than five years: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(24):2222–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noyes FR, Stabler CL. A system for grading articular cartilage lesions at arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17(4):505–13. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Øiestad BE, Engebretsen L, Storheim K, Risberg MA. Knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(7):1434–43. doi: 10.1177/0363546509338827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Øiestad BE, Holm I, Aune AK, Gunderson R, Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, Fosdahl MA, Risberg MA. Knee function and prevalence of knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective study with 10 to 15 years of follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2201–10. doi: 10.1177/0363546510373876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Outerbridge RE. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:752–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.43B4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paradowski PT, Bergman S, Sunden-Lundius A, Lohmander LS, Roos EM. Knee complaints vary with age and gender in the adult population. Population-based reference data for the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7(38) doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Internet] Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinke EK, Spindler KP, Lorring D, Jones MH, Schmitz L, Flanigan DC, An AQ, Quiram AR, Preston E, Martin M, Schroeder B, Parker RD, Kaeding CC, Borzi L, Pedroza A, Huston LJ, Harrell FE, Jr, Dunn WR. Hop tests correlate with IKDC and KOOS at minimum of 2 years after primary ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(11):1806–16. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1473-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roos EM, Klässbo M, Lohmander LS. WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28(4):210–5. doi: 10.1080/03009749950155562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roos EM, Lohmander LS. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:64. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)--development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28(2):88–96. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.2.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Røtterud JH, Risberg MA, Engebretsen L, Årøen A. Patients with focal full-thickness cartilage lesions benefit less from ACL reconstruction at 2-5 years follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(8):1533–9. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1739-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Røtterud JH, Sivertsen EA, Forssblad M, Engebretsen L, Årøen A. Effect of meniscal and focal cartilage lesions on patient-reported outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a nationwide cohort study from Norway and Sweden of 8476 patients with 2- year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):535–43. doi: 10.1177/0363546512473571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Meniscus tears that can be left in situ, with or without trephination or synovial abrasion to stimulate healing. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2012;20(2):62–7. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e318243265b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spindler KP, Huston LJ, Wright RW, Kaeding CC, Marx RG, Amendola A, Parker RD, Andrish JT, Reinke EK, Harrell FE, Jr, Dunn WR MOON Group. The prognosis and predictors of sports function and activity at minimum 6 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a population cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):348–59. doi: 10.1177/0363546510383481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toman CV, Dunn WR, Spindler KP, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Flanigan D, Jones MH, Kaeding CC, Marx RG, Matava MJ, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Wolcott M, Vidal A, Wolf BR, Huston LJ, Harrell FE, Jr, Wright RW. Success of meniscal repair at anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(6):1111–5. doi: 10.1177/0363546509337010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker SH, Duncan DB. Estimation of the probability of an event as a function of several independent variables. Biometrika. 1967;54(1):167–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright RW, Dunn WR, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Bergfeld J, Kaeding CC, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Wolcott M, Wolf BR, Spindler KP. Risk of tearing the intact anterior cruciate ligament in the contralateral knee and rupturing the anterior cruciate ligament graft during the first 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective MOON cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1131–4. doi: 10.1177/0363546507301318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright RW, Dunn WR, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Flanigan DC, Jones M, Kaeding CC, Marx RG, Matava MJ, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Vidal A, Wolcott M, Wolf BR, Spindler KP, MOON Cohort. Anterior cruciate ligament revision reconstruction: two-year results from the MOON cohort. J Knee Surg. 2007;20(4):308–11. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright RW, Preston E, Fleming BC, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Dunn WR, Kaeding C, Kuhn JE, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Parker RC, Spindler KP, Wolcott M, Wolf BR, Williams GN. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation: part I: continuous passive motion, early weightbearing, postoperative bracing, and home-based rehabilitation. J Knee Surg. 2008;21(3):217–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright RW, Preston E, Fleming BC, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Dunn WR, Kaeding C, Kuhn JE, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Parker RC, Spindler KP, Wolcott M, Wolf BR, Williams GN. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation: part II: open versus closed kinetic chain exercises, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, accelerated rehabilitation, and miscellaneous topics. J Knee Surg. 2008;21(3):225–34. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright RW, Haas AK, Anderson J, Calabrese G, Cavanaugh J, Hewett T, Lorring D, McKenzie C, Preston E, Schroeder B, Williams G MOON Group. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation: MOON guidelines. Sports Health. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1941738113517855. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]