Abstract

Background and Aims

Arabinogalactan protein 31 (AGP31) is a remarkable plant cell-wall protein displaying a multi-domain organization unique in Arabidopsis thaliana: it comprises a predicted signal peptide (SP), a short AGP domain of seven amino acids, a His-stretch, a Pro-rich domain and a PAC (PRP-AGP containing Cys) domain. AGP31 displays different O-glycosylation patterns with arabinogalactans on the AGP domain and Hyp-O-Gal/Ara-rich motifs on the Pro-rich domain. AGP31 has been identified as an abundant protein in cell walls of etiolated hypocotyls, but its function has not been investigated thus far. Literature data suggest that AGP31 may interact with cell-wall components. The purpose of the present study was to identify AGP31 partners to gain new insight into its function in cell walls.

Methods

Nitrocellulose membranes were prepared by spotting different polysaccharides, which were either obtained commercially or extracted from cell walls of Arabidopsis thaliana and Brachypodium distachyon. After validation of the arrays, in vitro interaction assays were carried out by probing the membranes with purified native AGP31 or recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis. In addition, dynamic light scattering (DLS) analyses were carried out on an AGP31 purified fraction.

Key Results

It was demonstrated that AGP31 interacts through its PAC domain with galactans that are branches of rhamnogalacturonan I. This is the first experimental evidence that a PAC domain, also found as an entire protein or a domain of AGP31 homologues, can bind carbohydrates. AGP31 was also found to bind methylesterified polygalacturonic acid, possibly through its His-stretch. Finally, AGP31 was able to interact with itself in vitro through its PAC domain. DLS data showed that AGP31 forms aggregates in solution, corroborating the hypothesis of an auto-assembly.

Conclusions

These results allow the proposal of a model of interactions of AGP31 with different cell-wall components, in which AGP31 participates in complex supra-molecular scaffolds. Such scaffolds could contribute to the strengthening of cell walls of quickly growing organs such as etiolated hypocotyls.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, plant cell wall, glycoprotein, arabinogalactan protein 31, AGP31, polysaccharides, non-covalent interactions, PAC domain, Brachypodium distachyon

INTRODUCTION

Plant cell walls are composite structures mainly composed of polysaccharides (Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993). Cellulose associates with hemicelluloses to form a framework embedded in a pectin matrix. Hemicelluloses are cross-linking polymers of diverse structures depending on species and cell types. They include xyloglucan (XG), xylan, arabinoxylan (AX), mannans, glucomannans and β-glucans (Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010; see Appendix for list of abbreviations). Pectins are also complex carbohydrates consisting of polygalacturonic acid (PGA), substituted galacturonans, and rhamnogalacturonans I and II (RGI and RGII) (Willats et al., 2006). PGA is an acidic linear polymer whose charge is modulated by the presence of methyl ester (m.e.) groups on galacturonic acid residues. RGI and RGII are complex substituted polysaccharides differing by their backbone and ramifications. RGI contains galactan, arabinan and type I arabinogalactan (AG) branches whereas RGII displays short but very complex ramifications. Cell walls also contain a large set of proteins involved in diverse functions. In recent years, proteomics studies performed mostly on Arabidopsis thaliana have advanced our understanding of cell-wall proteomes (Jamet et al., 2008; Albenne et al., 2013). Although some cell-wall proteins have been characterized in detail, knowledge on the role of each of them and their supra-molecular arrangement in cell walls is still lacking.

Among cell-wall proteins, arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) are complex O-glycoproteins. They were recently classified into several groups (Showalter et al., 2010): classical AGPs, Lys-rich AGPs, AG peptides, fasciclin-like AGPs, plastocyanin AGPs and chimeric AGPs. In total, 85 AGPs have been found in the A. thaliana genome by a bioinformatics approach. AGP domains are characterized by a biased amino acid composition rich in Pro (P), Ala (A), Ser (S) and Thr (T) (high PAST level). They have (XP)n motifs where X is either A, S or T and where P is converted to hydroxyproline (Hyp or O). AGPs were shown to be heavily O-glycosylated on Hyp (Tan et al., 2004). O-glycans were shown to be type II AGs (Tan et al., 2004). AGPs are also characterized by their ability to react with the β-glucosyl Yariv reagent (Seifert and Roberts, 2007). Their biological functions have been recently reviewed (Seifert and Roberts, 2007; Ellis et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2012). Classical AGPs are involved in many cellular processes during development and in response to environmental cues.

The A. thaliana AGP31 protein encoded by At1g28290 was classified as a chimeric AGP (Showalter et al., 2010) because it comprises several domains from the N to C terminus: a predicted signal peptide (SP), a short AGP domain of seven amino acids, a His-stretch, a Pro-rich domain and a C-terminal domain with six Cys residues at conserved positions also called the PAC domain (PRP for pro-rich protein-AGP containing Cys; Baldwin et al., 2001). Although its AGP domain is very short, AGP31 was classified as an AGP because it was shown to interact with the β-glucosyl Yariv reagent (Liu and Mehdy, 2007). Due to the presence of several other domains in AGP31, this protein is certainly atypical and its present name does not take into account its complex structure. The O-glycosylation pattern of the AGP31 Pro-rich domain was recently described (Hijazi et al., 2012). Hydroxyprolines were localized by peptide fragmentation followed by mass spectrometry analysis and new Hyp-O-Gal/Ara-rich motifs not recognized by the Yariv reagent were assumed to decorate the Hyp residues of the Pro-rich domain. It was also shown that AGP31 displays various glycoforms with different O-glycosylation patterns. In particular, some complex glycoforms of AGP31 were assumed to carry type II AGs on the N-terminal AGP domain (Hijazi et al., 2012).

Previous studies on proteins sharing domains with AGP31 suggest that AGP31 could play major roles in cell walls by interacting with various cell-wall components. First, the His-rich domain could interact with metal ions. This property was used to purify AGP31 by nickel affinity chromatography (NAC) (Liu and Mehdy, 2007; Hijazi et al., 2012). Interaction with metal ions was shown for other proteins having His-rich domains (Freyermuth et al., 2000; Kruger et al., 2002; Hara et al., 2005). The His-rich domain could also interact with PGA through ionic linkages, as suggested for DcAGP1 (Baldwin et al., 2001). Besides, AGP domains were assumed to interact with pectins (Hengel et al., 2001; Tan et al., 2012, 2013). Calcium-dependent in vitro interactions between Daucus carota cell-wall pectin extracts and a fraction enriched in AGPs were shown (Baldwin et al., 1993). Finally, the PAC domain with its six conserved Cys residues belongs to the large family of cysteine-rich peptides (CRPs) having between four and 16 conserved Cys residues (Silverstein et al., 2007; Marshall et al., 2011). Small proteins containing only a predicted SP and a domain homologous to the AGP31 PAC domain can be found in many plant species. The genome of A. thaliana contains eight such proteins (159–183 amino acids in length), including At2g34700, which may be involved in cell expansion and integument development (Skinner and Gasser, 2009). In the model grass Brachypodium distachyon, ten proteins (169–209 amino acids in length) having the same features were found by homology search in its genomic sequence (International Brachypodium Initiative, 2010). Three different roles were suggested for CRPs. An anti-oxidant activity could be shown for GASA4 (gibberellic acid-stimulated Arabidopsis 4), a protein having 12 conserved Cys residues (Rubinovich and Weiss, 2010). A lipid-binding activity was demonstrated for some lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) having eight conserved Cys residues (Yeats and Rose, 2007). Finally, based on work done on animal proteins with conserved Cys residues, it was suggested that PAC domains could interact with polysaccharides (Baldwin et al., 2001).

In this paper, we describe in vitro interactions of AGP31 with cell-wall polysaccharides, either commercially obtained or extracted from A. thaliana or B. distachyon cell walls, and with itself. The role of the PAC domain is emphasized and a model of non-covalent interactions of AGP31 with cell-wall components is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings (ecotype Columbia 0) were grown in vitro in the dark as described by Feiz et al. (2006). Etiolated hypocotyls were collected after 11 d. Nicotiana benthamiana and Brachypodium distachyon plants were cultivated under a 16/8-h light/dark cycle at 25 °C (light)/22 °C (dark) and 80 % humidity.

Production and purification of the recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis protein

Three cloning steps were necessary to obtain a construct allowing the production in N. benthamiana of a recombinant protein containing the SP of AGP31 and its PAC domain in fusion with the V5 epitope and the 6xHis tag. These tags were chosen to facilitate recombinant PAC protein detection and purification, respectively. Addition of the SP coding sequence was required to allow protein secretion in eukaryotic cells. The DNA fragments coding for the SP and the PAC were obtained separately by PCRs performed on the pda19846 cDNA clone (Riken Bioresource Center, http://www.brc.riken.jp/lab/epd/plant/cdnaclone_detail.cgi?rno=pda19846). Two pairs of oligonucleotide primers were used: PS (forward) and PS (reverse), and PAC1 (forward) and PAC2 (reverse) [see Supplementary Data Table S1]. Partial coverage between the SP reverse and the PAC forward primers allowed retrieval of the DNA fragment encoding the SP-PAC fusion protein. This fragment was cloned in the pBAD TOPO® vector (Invitrogen, Saint Aubin, France) to add the V5 epitope and the 6xHis tag coding sequences. The whole construct was subsequently amplified by two successive PCRs using the following primer pairs prior to cloning into the Gateway® pDONTM207 vector (Invitrogen): internal primer (forward) and internal primer (reverse); external primer (forward) and external primer (reverse) [Supplementary Data Table S1]. The last step was the cloning by homologous recombination of the SP : : PAC : : V5 : : 6xHis construct in the Gateway® pK7WG2D,1 vector (University of Ghent, www.psb.ugent.be/Gateway) downstream of a 35S cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) promoter. The 35S CaMV promoter was chosen to produce the recombinant protein in sufficient amount to perform in vitro interaction assays. This over-expression should not interfere with the results as the PAC-V5-6xHis recombinant protein was extracted from cell walls and purified prior to qualitative interaction assays.

The 35S : : SP : : PAC : : V5 : : 6xHis construct was transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves after co-infiltration of the transgenic Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 and a P19 strain (Voinnet et al., 2003) in the presence of 150 μm acetosyringone. Leaves were collected 2 d after infiltration. Cell walls were purified and cell-wall proteins were extracted as described (Irshad et al., 2008). The PAC-V5-6xHis recombinant protein was purified by two successive chromatographic steps: cationic exchange chromatography (CEC) as previously described (Irshad et al., 2008), followed by NAC using Ni-NTA columns as recommended by the manufacturer (Ni-NTA Start Kit, Qiagen, Courtabœuf, France). The protein was eluted with a 250 mm imidazole step. Quantification of proteins was done at each step of the purification procedure (Bradford, 1976).

Native AGP31 purification

Arabidopsis thaliana cell walls of 11-d-old etiolated hypocotyls were purified according to Feiz et al. (2006). Cell-wall proteins were extracted with 0·2 m CaCl2 and 2 m LiCl solutions (Irshad et al., 2008). AGP31 was purified from this protein fraction in two chromatographic steps (CEC, followed by NAC) or by affinity chromatography on peanut agglutinin (PNA)-lectin columns as described (Hijazi et al., 2012). About 40 µg of purified native AGP31 could be obtained from 6 g of lyophilized cell walls.

Separation and analysis of proteins

Recombinant and native proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (Laemmli, 1970). Staining of gels was done using the PageBlueTM Protein Staining Solution (Fermentas, Saint-Rémy-lès-Chevreuse, France). Western blots (Towbin et al., 1979) and lectin blots (Zhang et al., 2011) were performed as described using anti-V5 antibodies (Invitrogen) at a 1 : 10 000 dilution or using Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA) at a 1 : 200 dilution as recommended in the DIG Glycan Differentiation Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Preparation of cell-wall polysaccharide fractions

Three cell-wall-enriched polysaccharide fractions were prepared essentially as described (Fry, 1998; Moller et al., 2007). Purified cell walls from A. thaliana etiolated hypocotyls or B. distachyon leaves from which proteins had been extracted by salt solutions according to Irshad et al. (2008) were used as starting materials. Fifty milligrams of fresh material was weighed in a microtube. Three hundred microlitres of 1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid 50 mm (pH 7·5) were added prior to incubation for 1 h at room temperature. After centrifugation for 10 min at 2500 g, the supernatant was collected to constitute the pectin-enriched fraction. Then, hemicelluloses were extracted in the same way from the pellet by adding 300 μL of a solution of NaOH 4 m and NaBH4 1 %. Finally, cellulose was extracted from the last pellet by 300 μL cadoxen (1,2-diaminoethane 31 % v/v, cadmium oxide 0·78 m). In some assays, the cell-wall hemicellulose fraction was digested with proteinase K at 0·01, 1 or 10 μg μL–1 over 1 h at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped at 100 °C for 5 min.

Preparation of commercially obtained polysaccharide solutions

Several commercial polysaccharides were used for in vitro binding assays: PGA, m.e.PGA, galactan, RGI, AG, XG, β-glucan, xylan, AX and cellulose (Table 1, Supplementary Data Table S2). All of them were used at a final concentration of 1 or 10 mg mL–1 in water, with the exception of cellulose, which was dissolved in cadoxen, and orange PGA, which was dissolved in 1 % NaOH.

Table 1.

Commercial cell-wall polysaccharides used for in vitro protein/polysaccharide interaction assays; the description of the polysaccharides as provided by the suppliers is given in Supplementary Table S2

| Name | Molecule |

|---|---|

| Pectins | |

| Citrus PGA | Polygalacturonic acid, sodium salt |

| Orange PGA | Polygalacturonic acid |

| Apple m.e.PGA | Polygalacturonic acid methyl ester |

| Citrus m.e.PGA | Polygalacturonic acid methyl ester |

| Galactan | Galactan |

| RGI | Rhamnogalacturonan I |

| AG | Arabinogalactan |

| Hemicelluloses | |

| XG | Xyloglucan |

| β-glucan | β-glucan |

| Birch wood xylan | Xylan |

| Beech wood xylan | Xylan |

| AX | Arabinoxylan |

| Cellulose | |

| Cellulose | Cellulose |

Validation of the polysaccharide array

One microlitre (0·5 μL for cellulose) of each polysaccharide fraction (in-house prepared cell-wall-enriched polysaccharide, commercial polysaccharide fractions prepared at 1 or 10 mg mL–1) was spotted twice on a nitrocellulose membrane (8 × 11·5 cm) using the Bio-Dot system (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) under moderate vacuum. Membranes were dried for 30 min at room temperature. Monoclonal antibodies (PlantProbes, Leeds, UK) specific for PGA (JIM5), m.e.PGA (JIM7), XG (LM15) or β-(1–4)-d-galactan (LM5) were used to validate the polysaccharide array [Supplementary Data Fig. S1]. After saturation using 3 % bovine serum albumin (BSA)in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; Tris-HCl 20 mm, NaCl 150 mm, pH 7·5) for 1 h under gentle shaking, membranes were rinsed three times for 5 min with TBS. Monoclonal antibodies were incubated at a dilution of 1 : 80 in TBS for 2 h at 37 °C. Three washes with TBS were performed prior to incubation for 2 h with secondary anti-mouse antibodies coupled to alkaline phosphatase (Promega, Charbonnières, France) at a 1 : 10 000 dilution in TBS–1 % BSA. Finally, polysaccharides were revealed with an NBT (Sigma-Aldrich) 50 mg mL–1/BCIP (Sigma-Aldrich) 50 mg mL–1 solution in Tris-HCl 100 mm, NaCl 100 mm and MgCl2 5 mm.

In vitro binding assays on nitrocellulose membranes

The protocol was adapted from Moller et al. (2007). Polysaccharide arrays were prepared as described above. Purified proteins of interest were prepared in TBS at a final concentration of 30 μg mL–1 (PAC-V5-6xHis) or 10 μg mL–1 (native AGP31). For competition assays, proteins were first incubated in the presence of galactan (Megazyme, Wiklow, Ireland) at 1, 5 or 10 mg mL–1 or galactose (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1, 10 or 100 mg mL–1. To test the role of disulfide bridges in the PAC domain, β-mercaptoethanol (10 mm final concentration) was added to TBS. After saturation and washes as described above, each membrane was incubated with the protein solution overnight at 4 °C. After three washes with TBS, the membrane was incubated for 2 h under gentle shaking in the presence of anti-V5 antibodies (Invitrogen) at a dilution of 1 : 10 000 in TBS–1 % BSA 1. The following steps were as described above for polysaccharide detection. Alternatively, the membrane was revealed by a lectin blot method in the presence of PNA coupled to digoxigenin at a 1 : 100 dilution as recommended in the DIG Glycan Differentiation Kit (Roche). For interaction assays between AGP31 and PAC-V5-6xHis, 1 μg of each purified protein (AGP31 or PAC-V5-6xHis) was fixed on the nitrocellulose membrane. After saturation and washing steps performed as reported above, incubation was carried out using purified PAC-V5-6xHis or AGP31 at 10 μg mL–1 in TBS. Detection was achieved as described above using either anti-V5 antibodies or PNA coupled to digoxigenin.

Dynamic light scattering analyses

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analyses were performed on a DynaPro NanoStar (Wyatt Technology Corp., Toulouse, France) using a 4-μL sample cell (Wyatt Technology Corp.) at 293 K. The experiments were conducted with an acquisition time of 30 s, and analysed with Dynamic V7 software (Wyatt Technology Corp.). Purified native AGP31 prepared at 0·02 mg mL–1 in NAC elution buffer (NaH2PO4 50 mm, pH 8, NaCl 300 mm, imidazole 250 mm) was tested directly following the purification (CEC and NAC). BSA at 0·02 mg mL–1 in the same buffer was used as a negative control.

RESULTS

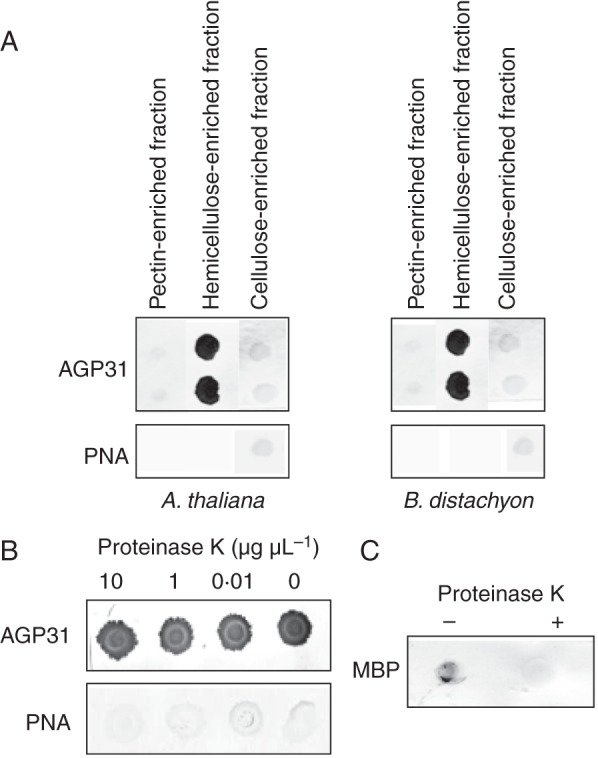

AGP31 interacts with galactan and RGI

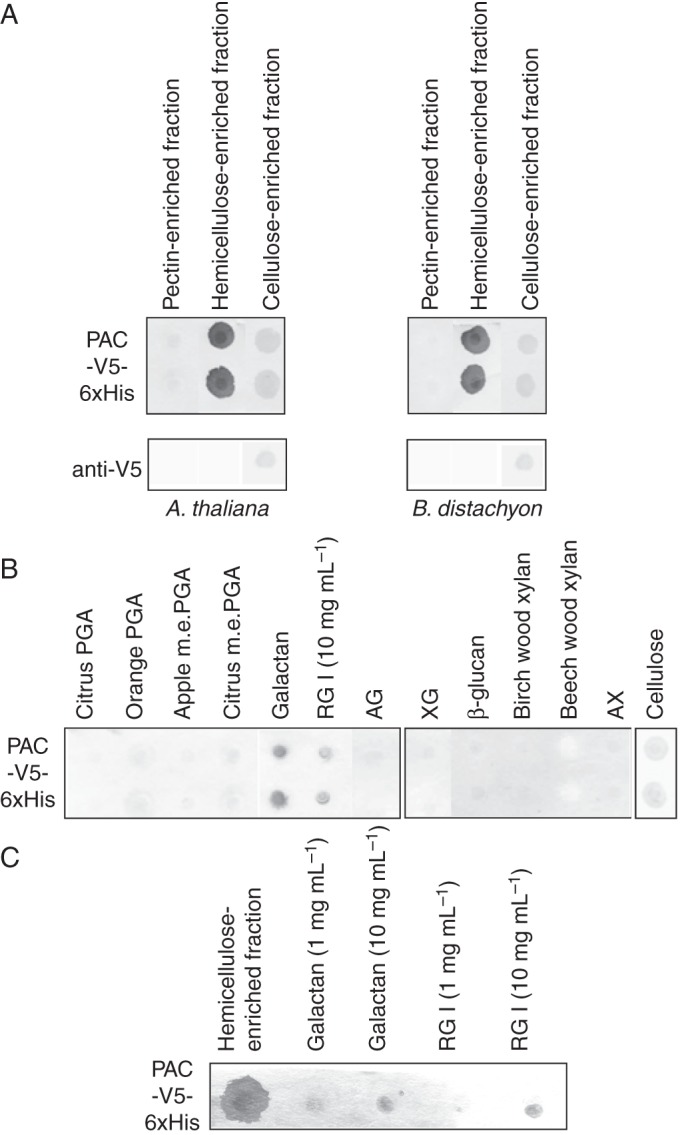

Three different fractions of cell-wall polysaccharides were successively extracted from cell walls of A. thaliana etiolated hypocotyls and B. distachyon leaves previously depleted in proteins. They were termed pectin-, hemicellulose- and cellulose-enriched cell-wall fractions. A polysaccharide array was prepared with these fractions and was validated using specific monoclonal antibodies (Supplementary Data Fig. S1): (1) the pectin-enriched fraction mostly contained PGA and m.e.PGA; (2) the hemicellulose-enriched fraction contained XG, but also pectic compounds, i.e. galactan and RGI; and (3) the cellulose-enriched fraction also included XG probably remaining associated with cellulose. Native AGP31 purified from etiolated hypocotyls of A. thaliana was used to probe the polysaccharide array. The PNA lectin previously shown to specifically recognize AGP31 was used to detect the interaction of AGP31 with polysaccharides (Hijazi et al., 2012). Figure 1A shows a very clear signal detected with the hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fractions from both A. thaliana and B. distachyon. No signal was obtained with the pectin- and cellulose-enriched fractions. As a control, PNA was used alone and did not give any signal.

Fig. 1.

In vitro interactions between AGP31 and cell-wall polysaccharides. (A) One microlitre (0·5 μL for cellulose) of each polysaccharide-enriched fraction (pectins, hemicelluloses and cellulose) was spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane. Cell-wall polysaccharide-enriched fractions from A. thaliana etiolated hypocotyls or B. distachyon leaves were used for interaction with purified native AGP31 at a final concentration of 10 μg mL–1. PNA coupled to digoxigenin was used to detect the interactions. Control was performed with PNA coupled to digoxigenin alone. (B) The same experiment was done with the hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fraction (1 μL spotted on the membrane) treated with proteinase K at 10, 1 or 0·01 μg μL–1. Negative controls were performed with PNA coupled to digoxigenin alone and/or no proteinase K treatment. (C) The activity of the proteinase K was checked on MBP in the NaOH solution used to extract hemicelluloses from cell walls. MBP was detected by specific antibodies. Interaction assays with AGP31 were carried out in duplicate.

To check the specificity of the interaction of AGP31 with polysaccharides, the A. thaliana hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fraction was incubated with proteinase K at various concentrations (from 0 to 10 μg μL–1) prior to incubation with AGP31. The same signal was detected in all cases (Fig. 1B). Again, the control performed with PNA alone gave no signal. The same result was obtained with the hemicellulose-enriched fraction of B. distachyon (data not shown). The activity of proteinase K was checked on the maltose binding protein (MBP) in the NaOH solution used to extract hemicelluloses from cell walls. MBP could be detected with an MBP-specific antibody only in the absence of proteinase K (Fig. 1C). This result confirmed that the interaction detected with AGP31 was not occurring with residual proteins present in the cell-wall fraction.

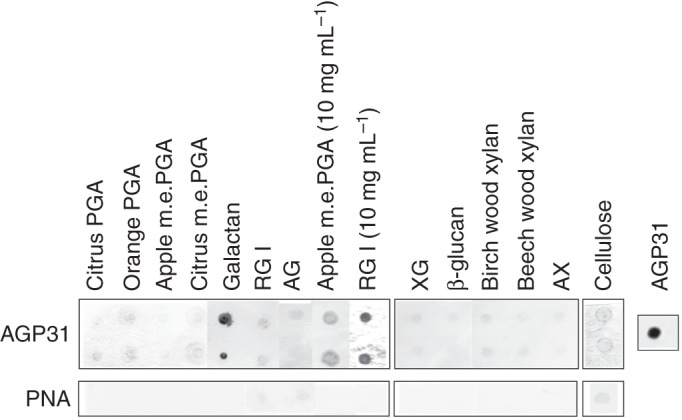

The next step of the study was the identification of the polysaccharides responsible for the observed interaction. We tested a range of commercial polysaccharides, including (1) pectic compounds: PGA, m.e.PGA, galactan, RGI, AG; (2) hemicellulosic compounds: XG, β-glucan, xylans, AX; and (3) cellulose (Table 1; Supplementary Data Table S2). First, polysaccharides were all prepared at 1 mg mL–1 and tested for interaction with purified AGP31. Mass concentrations were used for polysaccharides because molar concentrations were difficult to evaluate for such complex and heterogeneous polymers. A clear signal was observed only with galactan (Fig. 2). When increasing the polysaccharide concentrations to 10 mg mL–1, a weak signal was obtained with apple m.e.PGA and RGI. The positive control was provided by detection of AGP31 with PNA. The negative control comprised incubation with PNA alone.

Fig. 2.

In vitro interactions between AGP31 and commercial polysaccharides. One microlitre (0·5 μL for cellulose) of each polysaccharide solution (1 mg mL–1 except RGI and apple m.e.PGA, which were also deposited at 10 mg mL–1) was spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane: citrus and orange PGA; apple and citrus m.e.PGA; galactan; RGI; AG; XG; β-glucan; birch and beech wood xylans; AX; and cellulose. The membrane was incubated in the presence of purified native AGP31 at a final concentration of 10 μg mL–1. Interactions were detected with PNA coupled to digoxigenin. The negative control was performed with PNA coupled to digoxigenin alone. A positive control was performed with AGP31 (1 μg) directly deposited onto the nitrocellulose membrane. Interaction assays with AGP31 were carried out in duplicate.

Purified native AGP31 interacted with hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fractions of A. thaliana and B. distachyon as well as with commercial galactan and RGI. Interestingly, we knew from the polysaccharide array validation (Supplementary Data Fig. S1) that the hemicellulose-enriched fraction also contained galactan and RGI. These two polysaccharides were then assumed to be responsible for the interaction observed between AGP31 and the hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fraction. In addition, we showed that AGP31 interacted with commercial apple m.e.PGA. The next step was to identify the domain of AGP31 responsible for these interactions.

The AGP31 PAC domain mediates the interaction of AGP31 with galactan and RGI

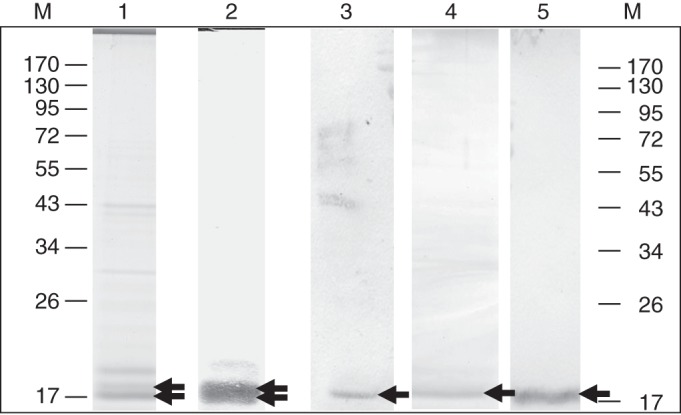

The AGP31 PAC domain was produced in N. benthamiana leaves as a recombinant protein tagged with the V5 epitope and 6xHis tag at its C terminus. Several steps were necessary to purify the protein (Fig. 3). Cell walls were purified and cell-wall proteins were extracted with 0·2 m CaCl2 and 2 m LiCl. Cell-wall proteins were first separated by CEC. CEC provided a fraction enriched in the PAC-V5-6xHis recombinant proteins, which had a basic pI. The recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis migrated as two bands of about 18 and 19·5 kDa detected after Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 3, lane 1). Detection with anti-V5 antibodies and GNA specific for mannosylated N-glycans revealed a wide and a thin band, respectively (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 3). At this step of purification, the detection of the recombinant protein with GNA indicated that this protein was N-glycosylated. Two N-glycosylation sites were actually predicted in the PAC domain (NRSL, NITA). The last step of purification was NAC, taking advantage of the 6xHis tag. SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified fraction showed a single band observed after both Coomassie blue staining and anti-V5 antibody detection, thus demonstrating the efficiency of the purification (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 5). About 36 μg of purified recombinant protein could be routinely obtained from 2·7 g of lyophilized cell walls.

Fig. 3.

Purification of the recombinant PAC domain produced in N. benthamiana. The PAC-V5-6xHis recombinant protein was produced in N. benthamiana leaves during 2 d after infiltration with transformed A. tumefaciens. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue after CEC (lane 1) and CEC + NAC (lane 4). The same fractions were analysed by western blot using V5 antibodies after CEC (lane 2) and CEC + NAC (lane 5), or by GNA lectin blot after CEC (lane 3). Molecular masses of markers (M) are in kDa. Arrows point to proteins of interest.

The purified recombinant PAC domain was used to detect interactions with the same polysaccharide fractions as those tested with the purified native AGP31. Anti-V5 antibodies were used to detect the interactions. Signals were observed with the A. thaliana and B. distachyon hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fractions (Fig. 4A) as well as with galactan at 1 mg mL–1 and RGI at 10 mg mL–1 (Fig. 4B). Controls performed in the absence of the recombinant PAC domain gave no signal (Fig. 4A). Note that the interaction was also observed with a recombinant MBP-PAC-V5-6xHis protein produced in bacteria which was not N-glycosylated (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

In vitro interactions between the recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain and cell-wall polysaccharides. (A) One microlitre (0·5 μL for cellulose) of each cell-wall polysaccharide-enriched fraction (pectins, hemicelluloses and cellulose) was deposited on a nitrocellulose membrane. Cell-wall polysaccharide-enriched fractions were from A. thaliana etiolated hypocotyls or B. distachyon leaves. Negative control was performed with anti-V5 antibodies alone. (B) One microlitre (0·5 μL for cellulose) of each of the following commercial polysaccharide solutions (1 mg mL–1 except RGI, which was deposited at 10 mg mL–1) was spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane: citrus and orange PGA; apple and citrus m.e.PGA; galactan; RGI; AG; XG; β-glucan; birch and beech wood xylans; AX; and cellulose. (C) One microlitre of the A. thaliana cell-wall hemicellulose-enriched fraction, 1 or 10 mg mL–1 of commercial galactan or RGI were spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane. Incubation was performed in the presence of 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol. The membranes were incubated in the presence of the purified recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain at a final concentration of 30 μg mL–1. Interactions were detected with anti-V5 antibodies. Interaction assays were carried out in duplicate in A and B.

The interaction of the recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain with the A. thaliana hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fraction, galactan and RGI was not modified in the presence of β-mercaptoethanol, which is assumed to destabilize disulfide bridges (Fig. 4C).

These experiments allowed us to conclude that the AGP31 PAC domain was responsible for the interaction of AGP31 with the hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fractions, galactan and RGI. Under our experimental conditions, neither the N-glycosylations of the PAC domain nor disulfide bridges played a role in the observed interactions. Although AGP31 interacted with m.e.PGA, no interaction with the recombinant PAC domain was detected, even at 10 mg mL–1, suggesting that this interaction involved another domain of AGP31.

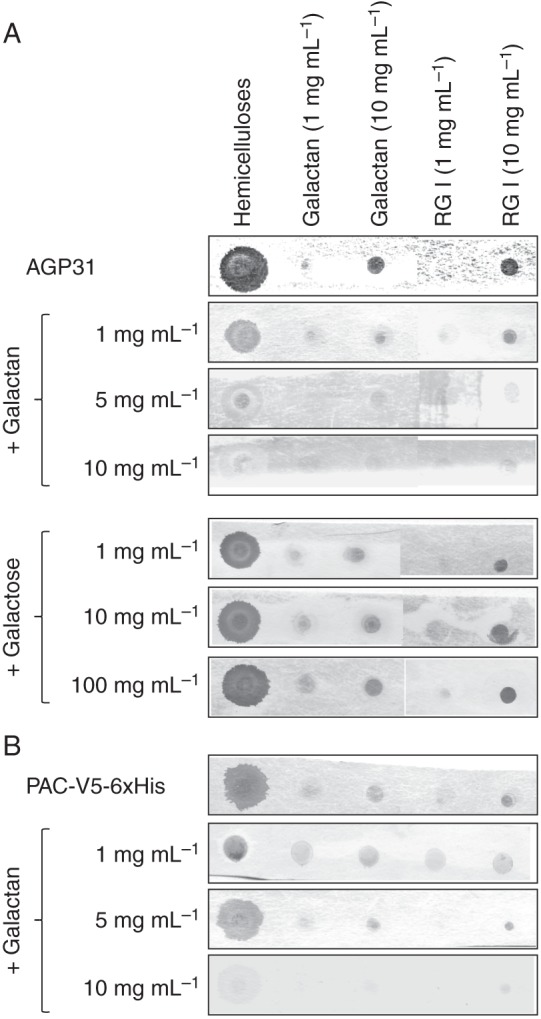

The interaction of AGP31 with galactan and RGI is inhibited by galactan

The last step consisted of checking the specificity of the interaction of AGP31 and its PAC domain with galactan and RGI contained in the hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fractions by competition with commercial galactan. The purified native AGP31 and the purified recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain were used. Interactions were detected with PNA and anti-V5 antibodies for AGP31 and the recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain, respectively. The A. thaliana hemicellulose-enriched fraction was spotted on the array as well as galactan and RGI at two concentrations (1 and 10 mg mL–1). Again, interactions with the three polysaccharide fractions were observed (Fig. 5). These interactions were completely inhibited by galactan at 5 mg mL–1 for AGP31, and at 10 mg mL–1 for the recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain. It should be noted that a pre-incubation of both proteins with galactose did not modify these interactions (Fig. 5A and data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Competition assays to test the specificity of the interactions between native AGP31 or PAC-V5-6xHis and polysaccharides in vitro. One microlitre of the A. thaliana hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fraction and 1 μL of each of the following commercial polysaccharides were spotted on the nitrocellulose membrane: galactan (1 or 10 mg mL–1); RGI (1 or 10 mg mL–1). (A) AGP31 (10 μg mL–1) was incubated with the membrane either directly or after pre-incubation for 1 h with galactan at 1, 5 or 10 mg mL–1, or with galactose at 1, 10 or 100 mg mL–1. Interactions were detected with PNA coupled with digoxigenin. (B) PAC-V5-6xHis (10 μg mL–1) was used directly, or after pre-incubation for 1 h with galactan at 1, 5 or 10 mg mL–1. Interactions were detected with anti-V5 antibodies.

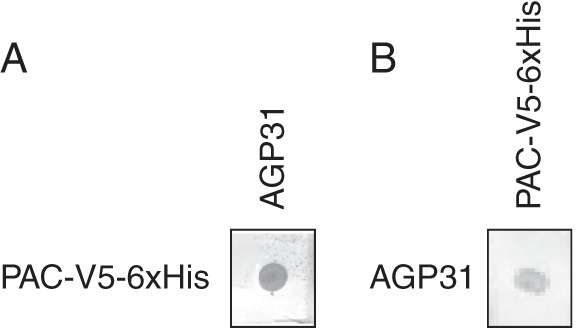

The recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain interacts with native AGP31

The results presented above showed that the recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain was able to interact with galactan. We recently demonstrated that the Pro-rich domain of AGP31 was O-glycosylated on Hyp residues with motifs rich in Gal and Ara (Hijazi et al., 2012). Such motifs could be comparable to the galactan used in this study. It was then tempting to test the interaction of the purified native AGP31 with the recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain. In the first test (Fig. 6A), AGP31, purified using CEC and NAC, was spotted on the membrane and the recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain was used as a probe in solution. The interaction was detected with anti-V5 antibodies. In the second test (Fig. 6B), the recombinant PAC-V5-6xHis domain was spotted on the nitrocellulose membrane and AGP31 was used as a probe in solution. The interaction was detected with PNA. An interaction was observed in both experiments, thus showing that AGP31 interacted with itself in vitro. We assumed that the C-terminal PAC domain interacted with the O-glycosylated Pro-rich domain where it recognized galactan. Note that AGP31 purified by affinity chromatography using PNA lectin shows a similar behaviour (data not shown). As AGP31 purified in such a way was thought to contain type II AGs on its AGP domain (Hijazi et al., 2012), we suggest that type II AGs do not influence interactions between AGP31 and its PAC domain.

Fig. 6.

Interactions between AGP31 and PAC-V5-6xHis in vitro. One microgram of each purified protein was fixed on the nitrocellulose membrane. (A) AGP31 (10 μg mL–1) was incubated with PAC-V5-6xHis spotted on the membrane. The interaction was detected with PNA coupled with digoxigenin. (B) PAC-V5-6xHis (10 μg mL–1) was incubated with AGP31 spotted on the membrane. The interaction was detected with anti-V5 antibodies.

AGP31 forms aggregates in solution

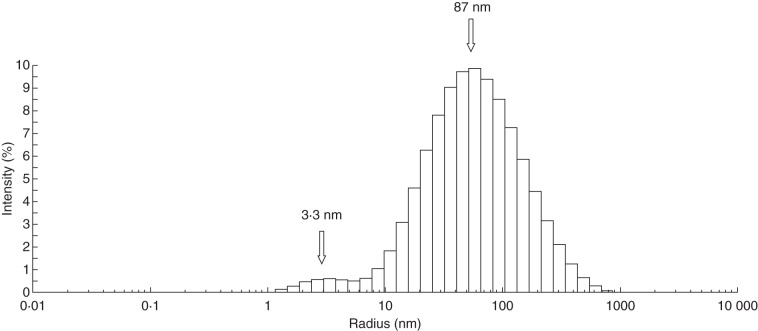

DLS experiments were carried out to evaluate the size of AGP31 in solution and to provide alternative evidence for AGP31 auto-assembly as assumed from in vitro interaction assays. Purified AGP31 was tested in solution directly following its purification by CEC and NAC. The data indicate the presence of two shapes, centred on hydrodynamic radii of 3·3 and 87 nm (Fig. 7). These forms may correspond to monomers of AGP31 and to protein aggregates, respectively. A large polydispersity is also observed, consistent with the mass heterogeneity known for AGP31 monomers and with aggregates of different sizes. Negative control using buffer or BSA in similar conditions did not give any significant light scattering signal (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Dynamic light scattering of purified native AGP31 in solution. Hydrodynamic radii (nm) were estimated from DLS analysis of purified native AGP31 at 0·02 mg mL–1. Assays were conducted directly following purification in elution buffer used for the NAC step.

DISCUSSION

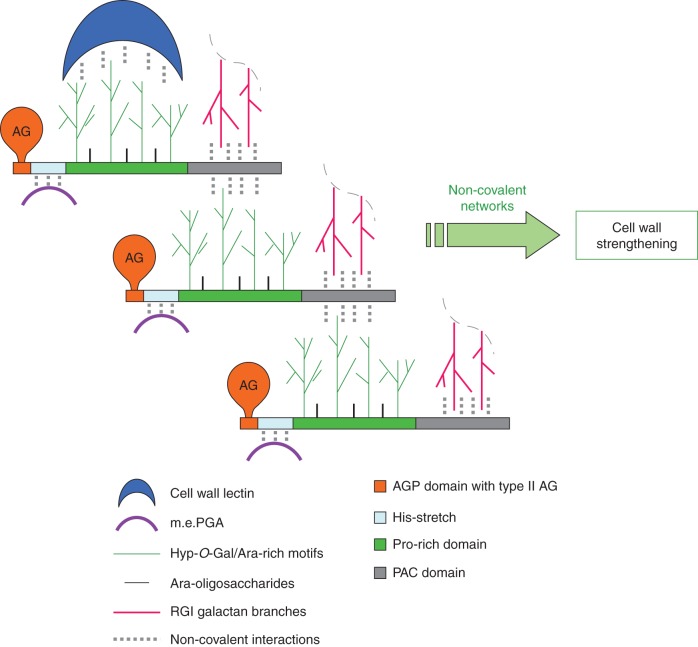

AGP31 is a chimeric protein of A. thaliana comprising different domains. Although these domains have homologues existing as proteins or protein domains, this particular association of domains is unique in A. thaliana. In this study, we demonstrate that AGP31 interacts in vitro with galactan and RGI through its C-terminal PAC domain as well as with m.e.PGA through another domain. We also show the self-recognition of AGP31, probably occurring between the galactan of its Pro-rich domain and the PAC domain. Finally, DLS experiments suggest that AGP31 forms aggregates in solution, corroborating the hypothesis of an auto-assembly. Based on these observations and on the AGP31 structural model previously described (Hijazi et al., 2012), we propose a model of non-covalent interactions of AGP31 with cell wall components where AGP31 participates to complex supra-molecular scaffolds (Fig. 8).We assume that the His-stretch located at the N terminus of AGP31 is responsible for the interaction with PGA through ionic linkages with the carboxyl groups of the galacturonosyl residues, as suggested for DcAGP1 (Baldwin et al., 2001). In addition to the interactions demonstrated here, we knew from previous studies that AGP31 has a remarkable affinity towards PNA (Zhang et al., 2011; Hijazi et al., 2012). PNA is a lectin recognizing the galactan of the AGP31 Pro-rich domain and it was successfully used as a specific AGP31 probe in this work. In the same way, AGP31 may interact in muro with lectins, such as legume lectins, which are the closest homologues of PNA and which were found in A. thaliana cell-wall proteomes (Irshad et al., 2008; Jamet et al., 2008).

Fig. 8.

Model of interactions of AGP31 with cell-wall components. AGP31 is schematized according to Hijazi et al. (2012), with arabinogalactans (AG) on its AGP domain and Hyp-O-Gal/Ara-rich motifs and Ara-oligosaccharides on its Pro-rich domain. Non-covalent interactions between AGP31 and its cell-wall partners are represented with dotted line.

Our results provide for the first time qualitative experimental evidence that the PAC domain is involved in interactions with polysaccharides. It interacts with hemicellulose-enriched cell-wall fractions of a dicot, A. thaliana, and a monocot, B. distachyon. No multi-domain protein homologue to AGP31 was found in the genome of B. distachyon, but proteins homologous to the PAC domain exist (e.g. Bradi2g48680 and Bradi2g18910). This result suggests that PAC domain proteins may also be involved in polysaccharide binding in B. distachyon cell walls. More precisely, we demonstrated that the AGP31 PAC domain binds: (1) galactan, which is present in cell walls as RGI ramifications, i.e. β-(1–4)-galactan, and (2) probably to O-galactan of the AGP31 Pro-rich domain. The latter glycan was recently described as Hyp-O-Gal/Ara-rich motifs, but its structure was not fully elucidated (Hijazi et al., 2012). However, it could display 3-, 6- and 3,6-linked galactopyranosyl residues similarly to Gal-rich glycan of NaPRP4, a Nicotiana alata protein homologue of AGP31 (Sommer-Knudsen et al., 1996). It means that the PAC domain could recognize galactans of various structures and be less selective than PNA, which specifically binds the Hyp-O-Gal/Ara-rich motifs of the Pro-rich domain. Indeed, PNA does not interact with any of the polysaccharides used in this study, particularly the β-(1–4)-galactan. The PAC domain is characterized by the presence of six Cys residues at conserved positions. Our results corroborate previous studies on animal extracellular matrix proteins containing Cys-rich domains which were shown to bind carbohydrates (Fiete et al., 1998). Besides, conserved Cys might form disulfide bridges contributing to the PAC domain structure. However, β-mercaptoethanol did not modify the interactions observed in vitro between the AGP31 recombinant PAC domain and polysaccharides, suggesting that disulfide bridges are not required for binding under our experimental conditions.

Our results suggest that the multi-domain organization of AGP31 contributes to AGP31 supra-molecular networking in cell walls. Only a few proteins per genome have an association of domains similar to that of AGP31 (Supplementary Data Table S3). They fall into two protein families, AGPs and PRPs. They are all rich in Pro residues, which can be hydroxylated in Hyp. However, not all of them comprise a His-stretch and clear AGP motifs. Many were shown to react with the β-glucosyl Yariv reagent. Known homologues of AGP31 are: AGP30 from A. thaliana (van Hengel and Roberts, 2003), DcAGP1 from D. carota (Baldwin et al., 2001), GhAGP31 from Gossypium hirsutum (Gong et al., 2012), transmitting tissue-specific 1 (TTS-1), TTS-2 and pistil extensin-like proteins (PELPs) from N. tabacum (Cheung et al., 1993, 1995; Goldman et al., 1992), NaPRP4 (GaRSGP), NaPRP5 and NaTTS from N. alata (Lind et al., 1994; Sommer-Knudsen et al., 1996; Schultz et al., 1997; Wu et al., 2001), PvPRP1 from Phaseolus vulgaris (Sheng et al., 1991), CaPRP1 from Capsicum annuum (Mang et al., 2004) and PhPRP1 from Petunia hybrida (Twomey et al., 2013). Some of these proteins share common features when observed by electron microscopy. TTS monomers were shown to display an ellipsoidal shape and to self-assemble into higher-order structures (Baldwin et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2001). A similar observation was made with a purified protein fraction from D. carota cell suspension cultures exhibiting characteristics of AGPs (Baldwin et al., 1993). The deglycosylation of TTS disrupts its ability to aggregate, suggesting a regulation of self-association by its level of O-glycosylation, which was shown to be variable (Wu et al., 1995). This could also be the case for AGP31, in which levels of O-glycosylation are heterogeneous (Hijazi et al., 2012).

It is thus reasonable to propose that proteins such as TTS and AGP31 self-assemble in a head-to-tail fashion through interactions between the O-glycans of their Pro-rich domain and their PAC domain. This is the first time that non-covalent networks between cell-wall proteins can be inferred from experimental evidence. Until now, only covalent networks of structural proteins have been demonstrated. Extensins and PRPs were shown to be insolubilized in cell walls (Cooper and Varner, 1984; Bradley et al., 1992) and assumed to be cross-linked by peroxidases (Brownleader et al., 1995; Schnabelrauch et al., 1996). The mechanism of assembly of AGP31 molecules would be slightly different from that assumed for the A. thaliana root shoot hypocotyl (RSH) extensin. Extensin molecules are self-assembling amphiphile molecules further cross-linked by peroxidases, as shown by atomic force microscopy revealing dendritic scaffolds (Cannon et al., 2008). Interestingly, as for AGP31, it is assumed that this extensin scaffold interacts with pectin molecules (Cannon et al., 2008).

To conclude, this study provides the first evidence that AGP31 interacts in vitro through its PAC domain with cell-wall polysaccharides. These data, combined with AGP31 features previously established, permitted us to propose a model of non-covalent interactions. We assume that AGP31 may be a structural protein involved in a supra-molecular network with cell-wall components, and could contribute to the integrity of cell walls. Interestingly, AGP31 and proteins related to AGP31 accumulate in quickly growing organs such as etiolated hypocotyls (Sheng et al., 1993; Irshad et al., 2008), roots and young leaves (Mang et al., 2004) or were shown to stimulate pollen tube growth (Wu et al., 1995). This suggests a function in the reinforcement of cell walls, which need to be built and strengthened very quickly. It would now be relevant to describe in more detail the interactions between AGP31 and its cell-wall partners. Besides, multi-domain proteins related to AGP31 or other PAC domains constitute good candidates for similar interaction assays. These in vitro data would open the route to further studies towards a better understanding of the functions of these proteins in plant cell walls.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Integrated Screening Platform of Toulouse (PICT, IBiSA) for providing access to DLS equipment. We thank Jean-Clément Mars, Joffrey Alves and Valérie Guillet for skilful technical assistance, and Vincent Burlat for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by the French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the Paul Sabatier University of Toulouse, and the Lebanon ecological association (grant to M.H.). This work was undertaken in the LRSV, as part of the ‘Laboratoire d'Excellence’ (LABEX) entitled TULIP (ANR -10-LABX-41). L.R.C.C. was supported by the Mexican National Council of Science and Technology CONACYT.

APPENDIX

List of abbreviations

- AG

arabinogalactan

- AGP

arabinogalactan protein

- AX

arabinoxylan

- CEC

cationic exchange chromatography

- CRP

cysteine-rich peptide

- Hyp

hydroxyproline

- m.e.

methyl ester

- NAC

nickel affinity chromatography

- PAC

PRP-AGP containing Cys

- PGA

polygalacturonic acid

- PNA

peanut agglutinin lectin

- PRP

proline-rich protein

- RGI

rhamnogalacturonan I

- RGII

rhamnogalacturonan II

- SP

signal peptide

- XG

xyloglucan

LITERATURE CITED

- Albenne C, Canut H, Jamet E. Plant cell wall proteomics: the leadership of Arabidopsis thaliana. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2013;4:111. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin T, McCann M, Roberts K. A novel hydroxyproline-deficient arabinogalactan protein secreted by suspension-cultured cells of Daucus carota: purification and partial characterization. Plant Physiology. 1993;103:115–123. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin T, Domingo C, Schindler T, Seetharaman G, Stacey N, Roberts K. DcAGP1, a secreted arabinogalactan protein, is related to a family of basic proline-rich proteins. Plant Molecular Biology. 2001;45:421–435. doi: 10.1023/a:1010637426934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. Rapid and sensitive method for quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing principle of protein-dye binding. Annals of Biochemistry. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley DJ, Kjellbom P, Lamb CJ. Elicitor- and wound-induced oxidative cross-linking of a proline-rich plant cell wall protein: a novel, rapid defense response. Cell. 1992;70:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90530-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownleader MD, Ahmed N, Trevan M, Chaplin MF, Dey PM. Purification and partial characterization of tomato extensin peroxidase. Plant Physiology. 1995;109:1115–1123. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.3.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M, Terneus K, Hall Q, et al. Self-assembly of the plant cell wall requires an extensin scaffold. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2008;105:2226–2231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711980105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants, consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant Journal. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AY, May B, Kawata EE, Gu Q, Wu H-M. Characterization of cDNAs for stylar transmitting tissue-specific proline-rich proteins in tobacco. Plant Journal. 1993;3:151–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AY, Wang H, Wu HM. A floral transmitting tissue-specific glycoprotein attracts pollen tubes and stimulates their growth. Cell. 1995;82:383–393. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JB, Varner JE. Cross-linking of soluble extensin in isolated cell walls. Plant Physiology. 1984;76:414–417. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis M, Egelund J, Schultz CJ, Bacic A. Arabinogalactan-proteins: key regulators at the cell surface? Plant Physiology. 2010;153:403–419. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiz L, Irshad M, Pont-Lezica RF, Canut H, Jamet E. Evaluation of cell wall preparations for proteomics: a new procedure for purifying cell walls from Arabidopsis hypocotyls. Plant Methods. 2006;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiete DJ, Beranek MC, Baenziger JU. A cysteine-rich domain of the “mannose” receptor mediates GalNAc-4-SO4 binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1998;95:2089–2093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyermuth SK, Bacanamwo M, Polacco JC. The soybean Eu3 gene encodes an Ni-binding protein necessary for urease activity. Plant Journal. 2000;21:53–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC. Oxidative scission of plant cell wall polysaccharides by ascorbate-induced hydroxyl radicals. Biochemical Journal. 1998;332:507–515. doi: 10.1042/bj3320507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MH, Pezzotti M, Seurinck J, Mariani C. Developmental expression of tobacco pistil-specific genes encoding novel extensin-like proteins. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1041–1051. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.9.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S-Y, Huang G-Q, Sun X, et al. GhAGP31, a cotton non-classical arabinogalactan protein, is involved in response to cold stress during early seedling development. Plant Biology (Stuttgart) 2012;14:447–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2011.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M, Fujinaga M, Kuboi T. Metal binding by citrus dehydrin with histidine-rich domains. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2005;56:2695–2703. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengel AV, Tadesse Z, Immerzeel P, Schols H, Kammen AV, Vries SD. N-acetylglucosamine and glucosamine-containing arabinogalactan proteins control somatic embryogenesis. Plant Physiology. 2001;117:1880–1890. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijazi M, Durand J, Pichereaux C, Pont F, Jamet E, Albenne C. Characterization of the Arabinogalactan protein 31 (AGP31) of Arabidopsis thaliana. New advances on the Hyp-O-glycosylation of the Pro-rich domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:9623–9632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.247874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Brachypodium Initiative. Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature. 2010;463:763–768. doi: 10.1038/nature08747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad M, Canut H, Borderies G, Pont-Lezica R, Jamet E. A new picture of cell wall protein dynamics in elongating cells of Arabidopsis thaliana: confirmed actors and newcomers. BMC Plant Biology. 2008;8:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamet E, Albenne C, Boudart G, Irshad M, Canut H, Pont-Lezica R. Recent advances in plant cell wall proteomics. Proteomics. 2008;8:893–908. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger C, Berkowitz O, Stephan U, Hell R. A metal-binding member of the late embryogenesis abundant protein family transports iron in the phloem of Ricinus communis L. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:25062–25069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of the structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind JL, Bacic A, Clarke AE, Anderson MA. A style-specific hydroxyproline rich glycoprotein with properties of both extensins and arabinogalactan proteins. Plant Journal. 1994;6:491–502. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6040491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Mehdy M. A nonclassical arabinogalactan protein gene highly expressed in vascular tissues, AGP31, is transcriptionally repressed by methyl jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2007;145:863–874. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.102657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mang HG, Lee J-H, Park JA, et al. The CaPRP1 gene encoding a putative proline-rich glycoprotein is highly expressed in rapidly elongating early roots and leaves in hot pepper (Capsicum annuum L. cv. Pukang) Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2004;1674:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall E, Costa LM, Gutierrez-Marcos J. Cysteine-Rich Peptides (CRPs) mediate diverse aspects of cell–cell communication in plant reproduction and development. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2011;62:1677–1686. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller I, Sorensen I, Bernal AJ, et al. High-throughput mapping of cell-wall polymers within and between plants using novel microarrays. Plant Journal. 2007;50:1118–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinovich L, Weiss D. The Arabidopsis cysteine-rich protein GASA4 promotes GA responses and exhibits redox activity in bacteria and in planta. Plant Journal. 2010;64:1018–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller H, Ulvskov P. Hemicelluloses. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2010;61:263–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabelrauch LS, Kieliszewski M, Upham BL, Alizedeh H, Lamport DT. Isolation of pl 4·6 extensin peroxidase from tomato cell suspension cultures and identification of Val-Tyr-Lys as putative intermolecular cross-link site. Plant Journal. 1996;9:477–489. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.09040477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz CJ, Hauser K, Lind JL, et al. Molecular characterisation of a cDNA sequence encoding the backbone of a style-specific 120 kDa glycoprotein which has features of both extensins and arabinogalactan proteins. Plant Molecular Biology. 1997;35:833–845. doi: 10.1023/a:1005816520060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert G, Roberts K. The biology of arabinogalactan proteins. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2007;58:137–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng JS, Dovidio R, Mehdy MC. Negative and positive regulation of a novel proline rich protein messenger-RNA by fungal elicitor and wounding. Plant Journal. 1991;1:345–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1991.t01-3-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng JS, Jeong J, Mehdy MC. Developmental regulation and phytochrome-mediated induction of mRNAs encoding a proline-rich protein, glycine-rich proteins, and hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1993;90:828–832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter A, Keppler B, Lichtenberg J, Gu D, Welch L. A bioinformatics approach to the identification, classification, and analysis of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins. Plant Physiology. 2010;153:485–513. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein KAT, Moskal WA, Jr, Wu HC, et al. Small cysteine-rich peptides resembling antimicrobial peptides have been under-predicted in plants. Plant Journal. 2007;51:262–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner DJ, Gasser CS. Expression-based discovery of candidate ovule development regulators through transcriptional profiling of ovule mutants. BMC Plant Biology. 2009;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer-Knudsen J, Clarke A, Bacic A. A galactose-rich, cell-wall glycoprotein from styles of Nicotiana alata. Plant Journal. 1996;9:71–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.09010071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Qiu F, Lamport D, Kieliszewski M. Structure of a hydroxyproline (Hyp)-arabinogalactan polysaccharide from repetitive Ala–Hyp expressed in transgenic Nicotiana tabacum. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:13156–13165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Showalter A, Egelund J, Hernandez-Sanchez A, Doblin M, Bacic A. Arabinogalactan-proteins and the research challenges for these enigmatic plant cell surface proteoglycans. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2012;3:140. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Eberhard S, Pattathil S, et al. An Arabidopsis cell wall proteoglycan consists of pectin and arabinoxylan covalently linked to an arabinogalactan protein. Plant Cell. 2013;25:270–287. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.107334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey MC, Brooks JK, Corey JM, Singh-Cundy A. Characterization of PhPRP1, a histidine domain arabinogalactan protein from Petunia hybrida pistils. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2013;170:1384–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hengel AJ, Roberts K. AtAGP30, an arabinogalactan-protein in the cell walls of the primary root, plays a role in root regeneration and seed germination. Plant Journal. 2003;36:256–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O, Rivas S, Mestre P, Baulcombe D. An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant Journal. 2003;33:949–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willats WGT, Knox P, Mikkelsen JD. Pectin: new insights into an old polymer are starting to gel. Trends in Food Science Technology. 2006;17:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wu HM, Wang H, Cheung AY. A pollen tube growth stimulatory glycoprotein is deglycosylated by pollen tubes and displays a glycosylation gradient in the flower. Cell. 1995;82:395–403. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, de Graaf B, Mariani C, Cheung AY. Hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins in plant reproductive tissues: structure, functions and regulation. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2001;58:1418–1429. doi: 10.1007/PL00000785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeats TH, Rose J. The biochemistry and biology of extracellular plant lipid-transfer proteins (LTPs) Protein Science. 2007;17:191–198. doi: 10.1110/ps.073300108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Giboulot A, Zivy M, Valot B, Jamet E, Albenne C. Combining various strategies to increase the coverage of the plant cell wall glycoproteome. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.