Abstract

Obesity is a global epidemic that contributes to the increasing medical burdens related to type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. A better understanding of the mechanisms regulating adipose tissue expansion could lead to therapeutics that eliminate or reduce obesity-associated morbidity and mortality. The extracellular matrix (ECM) has been shown to regulate the development and function of numerous tissues and organs. However, there is little understanding of its function in adipose tissue. In this manuscript we describe the role of laminin α4, a specialized ECM protein surrounding adipocytes, on weight gain and adipose tissue function. Adipose tissue accumulation, lipogenesis, and structure were examined in mice with a null mutation of the laminin α4 gene (Lama4−/ −) and compared to wild-type (Lama4+/+) control animals. Lama4−/ − mice exhibited reduced weight gain in response to both age and high fat diet. Interestingly, the mice had decreased adipose tissue mass and altered lipogenesis in a depot-specific manner. In particular, epididymal adipose tissue mass was specifically decreased in knock-out mice, and there was also a defect in lipogenesis in this depot as well. In contrast, no such differences were observed in subcutaneous adipose tissue at 14 weeks. The results suggest that laminin α4 influences adipose tissue structure and function in a depot-specific manner. Alterations in laminin composition offers insight into the roll the ECM potentially plays in modulating cellular behavior in adipose tissue expansion.

Introduction

Obesity continues to increase globally in both industrialized and developing countries, with the World Health Organization reporting that worldwide obesity rates have doubled since 1980. Over 1 billion adults 20 years of age or older are overweight with an estimated 500 million of these defined as obese. Obesity is a major risk factor for several chronic diseases, contributing to a dramatic increase in morbidity and mortality due to type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and other malignancies [1]. These issues with weight control result in a greater than $190 billion annual burden on US healthcare, and it has been suggested that the negative effects of obesity outweighs the positive effects of smoking cessation on the overall health of the population [2].

The ability to modulate adipose tissue expansion and function could be a tremendous benefit to healthcare. Adipocytes are complex endocrine cells involved in insulin sensitivity, feeding behavior, and neuroendocrine function. A number of soluble hormones and growth factors have been shown to have an influence on adipose tissue insulin sensitivity and expansion. However, little attention has been paid to the contribution of interactions between adipocytes and the extracellular matrix (ECM) to this process. Adipocytes are in constant contact with a network of insoluble proteins and polysaccharides known as the ECM. ECM interactions in adipose tissue can be divided into two major categories: (1) interactions with basement membranes (BM), a thin layer sheet surrounding differentiated adipocytes, and (2) interactions with stromal, or interstitial ECM that occur when adipocytes invade the tissue stroma during adipose tissue expansion. In other tissues, it is well-known that interactions with the ECM can regulate cell growth, differentiation, and migration, and influence tissue development and repair [3]–[7]. However, little is known about the influence of the ECM on adipose tissue.

While adipose tissue-ECM interactions have not been studied extensively, there is some evidence that the ECM plays an important role in regulating adipogenesis and adipocyte function [8]. The synthesis and remodeling of ECM molecules is enhanced during adipogenesis [9,10]. Differentiating preadipocytes degrade the local matrix, invade the surrounding stroma, and then synthesize new ECM components as they mature [11]. The ECM surrounding preadipocytes transitions from fibronectin-rich to laminin-rich during differentiations primarily through an increase in an α4 chain containing BM protein laminin [12]. In cell culture models, a preadipocyte cell line has been shown to express laminin, entactin and collagen IV during differentiation [13]. Laminins LN-411 and LN-421, are laminin isoforms consisting of a triple helix of the α4, β1 or β2 and γ1 chains, are expressed in excess to other isoforms at this time [14]. The α4 chain of laminin is present in the BM surrounding fully differentiated adipocytes and is upregulated during differentiation. However, the potential importance of the α4 chain laminins in the BM surrounding adipocytes has not been elucidated.

In this study, mice with a null mutation of the laminin α4 gene (Lama4−/ −) were used to examine a potential role for α4 chain laminins in adipose tissue expansion and function. Weight gain, adipose tissue function and adipose tissue structure were examined in Lama4−/− mice and compared to wild-type control animals. The Lama4−/− mice were found to be resistant to age-related and diet-induced obesity, and exhibited a depot-specific change in adipose tissue structure, volume and function.

Material and Methods

Animals, diets and housing

The generation of laminin α4 null mice (Lama4−/−) was previously described [15]. The mice were backcrossed to C57 BL/6 mice (Charles River) for more than 10 generations. Mice were fed a standard diet, or a high-fat diet containing 45 energy % fat (D12451, Research Diets), beginning at 4 weeks of age. The animals were fed ad libitum and their food was weighed weekly. The mice were given a food refill up to 500 g after each weighing. The amount of food consumed was divided by the number of animals in a cage as an estimate of intake.

All animal procedures were approved by the IACUC at Karolinska Institutet or the University of Chicago. The animals were housed either in mixed cages (two Lama4−/− and two wild-type control animals) or in cages with only Lama4−/− mice or wild-types, in order to rule out the possibility that the weight differences observed were due to differences in dominance behavior. No differences were observed due to housing conditions.

Immunostaining

For immunostaining in mouse tissues, animals at 16 weeks of age were sacrificed and tissue harvested. Samples were placed in TissueTek (Sakura) in plastic molds and frozen in isopentane cooled to its freezing point. Cryosections of 8–12 µm in thickness were made at −38°C. The sections were allowed to dry for 1 hour at room temperature and then fixed in acetone for 10 minutes before staining, except for antibody to laminin α4, where the sections were additionally treated for 5 minutes in boiling 1 M Urea and washed in distilled water.

The antibodies used anti-nidogen/entactin (MAB 1946, Chemicon), anti-collagen type IV (polyclonal # AB756P, Chemicon), anti-perlecan (clone HK-102, Seikagaku Corp), anti-laminin α1 (clone 198 (35)), anti-laminin α2 (clone 4H8-2), anti-laminin α4 (polyclonal S8 (36)), anti-laminin α5 (serum 405). Secondary antibodies were FITC- or Cy3- conjugated and purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. Tissue sections were examined with a Leica MDRB microscope (Leica) and pictures were taken with a Hamamatsu digital camera with Openlab (Improvision) software. Digital images were further processed with Photoshop 5.0 (Adobe).

Liver histopathology

Livers were harvested from 40 week old Lama4−/− mice for histopathological evaluation (10 Lama4−/− mice on both diets). For histological staining the tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded and stained according to standard protocols. Tissue sections were examined with a Leica MDRB microscope (Leica) and pictures were taken with a Hamamatsu digital camera with Openlab (Improvision) software. Digital images were further processed with Photoshop 5.0 (Adobe).

Adipose tissue depot structure

Lama4+/+ and Lama4−/− mice were fed a standard diet. At 14 weeks of age mice were sacrificed. Epididymal and subcutaneous fat depots were harvested, and the mass assessed. Mass of adipose tissues from each depot was normalized to the total individual animal weight the depot was harvested from using equation (1). The normalized % fat pad weight takes into account variation introduced from individual total animal weights.

|

(equation 1) |

A portion of each fat pad type was then placed in formaldehyde and paraffin embedded. Samples were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Five images were taken with an Axiovert 200 inverted microscope using a 5× objective (1.3 µm/pixel) (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY) for each fat pad. The images were used to manually measure the diameters of individual adipocytes using AxioVision (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging).

Lipogenesis. Lama4+/+ and Lama4−/− mice were fed a standard diet. At 14 weeks of age mice were sacrificed. Fat pads were harvested and weighed prior to functional analysis with a lipogenesis assay. The assay was performed as described previously [16]. Briefly, adipocytes were isolated from the harvested fat pads by collagenase digestion and centrifugation. Isolated adipocytes were incubated with radioactive glucose in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate containing 10 nm insulin and 1% (w/v) BSA. The lipid fraction was extracted and radioactivity in the triglyceride fraction measured.

Statistics

The repeated measures of animal weights over time and food consumption over time were analyzed with ANOVA followed with Tukey test. Student's t test was used for all other statistical analysis (two-tailed), p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Adipose tissue composition of Lama4 −/− mice

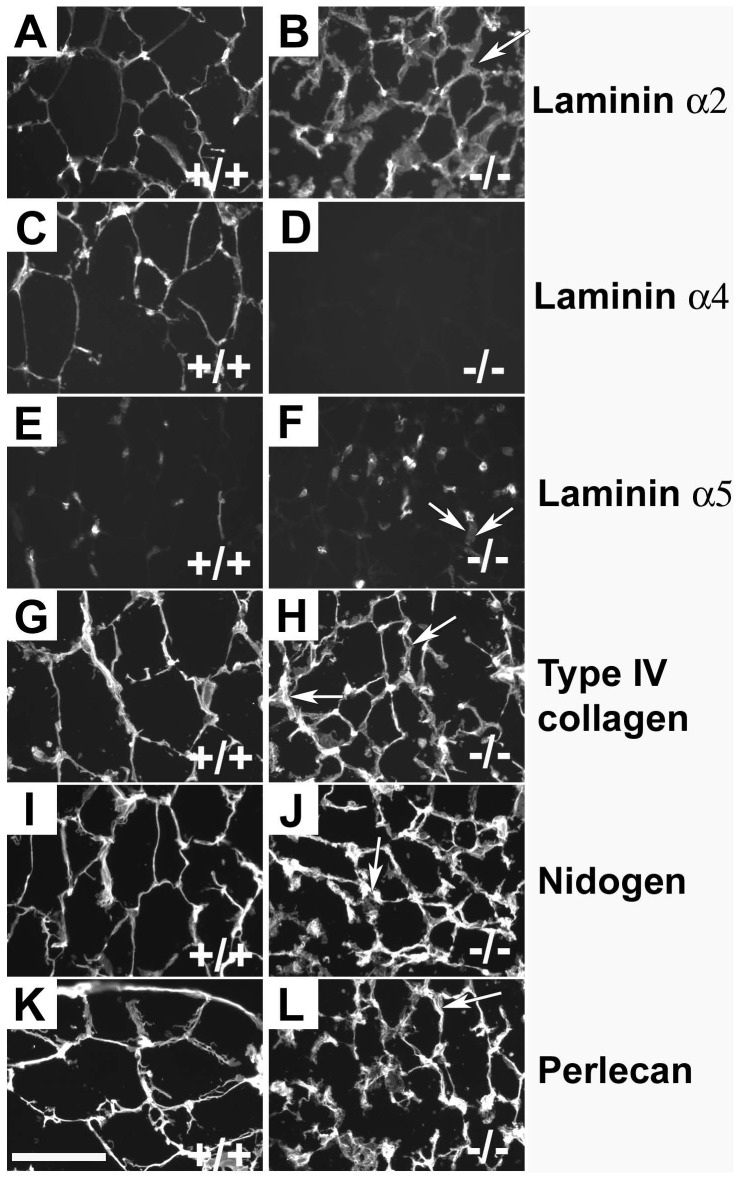

Immunofluorescence staining was first performed to compare BM composition surrounding adipocytes in Lama4−/− and Lama4+/+ mice. Staining was performed for known adipose tissue BM proteins, including the α1,α2, α4 andα5 chains of laminin, type IV collagen, nidogen and perlecan. In wild-type control mice the α2 and α4 chains of laminin were present in the BM surrounding mature adipocytes (Figure 1). Laminin α5 was not observed in mouse adipocyte BM. Type IV collagen, perlecan and nidogen were present the murine pericellular adipocyte BM. When examining Lama4−/− BM, the only difference in composition was the complete absence of laminin α4. All other BM proteins present in the adipose tissue BM of wild-type control mice were also observed in the pericellular BM of Lama4−/− mice. The adipocyte BM appeared somewhat thicker in the Lama4−/− mice.

Figure 1. Immunostaining of WAT.

The capillaries and BMs of adipocytes of wild-type control and Lama4Lama4−/− mice were positive with antibodies against laminin α2 (A, B). Laminin α4 antibodies stained both adipocytic BMs and capillaries in wild-type controls (C), while no staining was seen in mutants (D). The laminin α5 antibody (E, F) stained capillaries in Lama4−/− and wild-type controls, but not the adipocytic BM. Antibodies against type IV collagen (G; H), nidogen (I, J) and perlecan (K, L) all stained both capillaries and adipocytic BMs. Laminin α1 staining was completely negative (not shown). Arrows indicate a few locations where the adipocytic BM of the Lama4−/− mice appeared slightly thickened. Bar 100 µm.

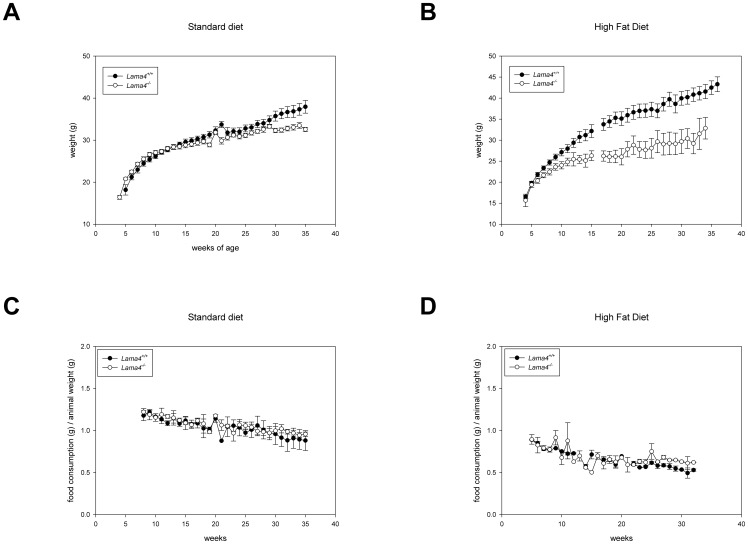

Lama4−/− mice are resistant to age and diet induced obesity. The birth weight of laminin α4 deficient mice was ∼10% lower than wild-type control littermates as previously reported [15]. At the time of weaning (3–4 weeks), no difference in weight was observed between Lama4−/− or wild-type control animals (Lama4−/− 20.8±0.26 g, n = 16; Lama+/+ 18.2±1.05 g, n = 11). Animal weights were monitored first on a standard diet. A statistical difference in weight was observed between wild-type control and Lama4−/− animals (Figure 2A; p = 0.002). Lama4−/− weighed less than wild-type control animals from 16 weeks on and the difference between knockout and wild-type control animal weights increased steadily over time.

Figure 2. The weight difference of 16 male Lama4−/− mice and 12 wild-type controls were statistically significantly (p = 0.002).

(A). When fed a high-fat diet (B), 8 male wild-type control mice gained statistically significant (p<0.001) more weight than the 8 Lama4−/− mice. The weekly intake of standard food (C) and high fat diet (D) related to the weight of the animals were not significantly different.

To further investigate weight gain in these animals, mice were supplied a high-fat diet starting at four weeks of age. Lama4−/− animals gained weight at a much lower rate and differences were observed from wild-type control animal weights within 4 weeks on this diet (Lama4−/− 22.45±0.73 g, n = 8; Lama+/+ 24.69±0.61 g, n = 8; Figure 2B). This difference continued to increase over time with Lama4−/− exhibiting slow weight gain even on the high-fat diet. In fact, at 34 weeks of age, there was no difference in the average weight of Lama4−/− mice whether they were on standard or high-fat diets (standard diet 32.6±0.5 n = 12 vs high-fat diet 32.8±2.57 n = 3). Wild-typetype control animals rapidly gained weight on the high fat diet resulting in dramatic differences from Lama4−/− at 13 weeks (Lama4−/− 25.4±0.89 g, n = 8; Lama+/+ 30.7±1.27 g, n = 8;). A statistical difference in weight was observed between wild-type control and Lama4−/− animals on high fat diet (Figure 2B; p<0.001).

The livers of the Lama4−/− mice on standard diet did not display signs of liver steatosis after 40 weeks (File S1) suggesting that the decreased body fat in Lama4−/− mice does not represent a form of lipodystrophy. On a high-fat diet Lama4−/− mice only had very mild steatosis (File S1).

Food consumption

In order to evaluate whether the observed differences in weight and body composition resulted from lower food consumption, food intake was quantified weekly. There was no difference in the total amount of food consumed between Lama4−/− and wild-type control animals on either standard (P = 0.418) or high fat diet (p = 0.098) (Figure 2C, D). These results suggest that the weight differences observed did not result from hypophagia in the Lama4−/− mice.

Adipose Tissue Structure

Lama4−/− and age matched wild-type control animals 13 to 15 week on a standard diet were used to further examine adipose tissue structure and function. This time range was selected because it is prior to any statistically significant weight differences between Lama4−/− and control animals, allowing for the examination of adipose tissue function without confounding results due to obesity. At the time of sacrifice there were no differences in total animal mass between Lama4−/− and control animals (Lama4−/− 25.93±0.77 g, n = 4; Lama+/+ 26.60±2.35 g, n = 4; p = 0.80).

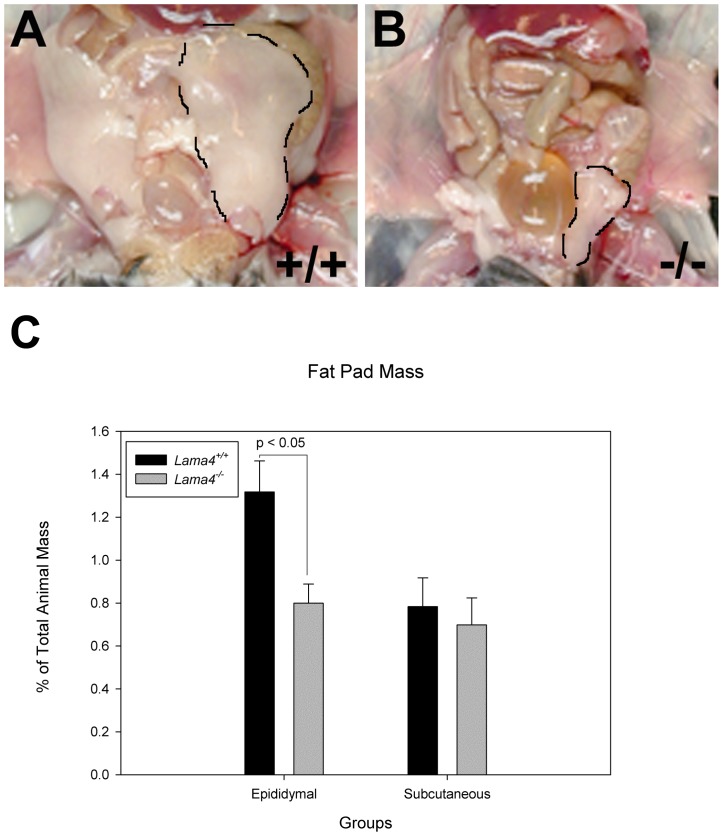

Epididymal and subcutaneous adipose tissue were harvested from the mice (Figure 3A, B). The normalized percentage mass of Lama4−/− mice's epididymal adipose tissue was significantly less than control mice (Lama4−/− 0.80±0.09%, n = 4; Lama+/+ 1.32±0.14%, n = 4; p = 0.022) (Figure 3C). The mass of Lama4−/− mice's epididymal adipose tissue was less than control mice (Lama4−/− 0.21±0.03 g, n = 4; Lama+/+ 0.36±0.07 g, n = 4; p = 0.10). Interestingly, no differences in mass were observed between subcutaneous adipose tissue mass (Lama4−/− 0.18±0.04 g, n = 4; Lama+/+ 0.21±0.06 g, n = 4; p = 0.69). These results indicate that prior to any phenotypic observations in total animal weight gain, epididymal volume was reduced in Lama4−/− mice.

Figure 3. The Lama4 −/− mice had reduced fat depots.

The epididymal fat is delineated in an opened 40 week old male wild-type control mice (A) and a male Lama4 −/− mice is shown in (B). Normalized fat pad depot mass as a % of total animal mass (C). Epididymal fat pad mass in Lama4−/− mice was significantly lower than Lama4+/+ mice (p<0.05). Age matched animal Lama4−/− and Lama4+/+, n = 4 for epididymal and subcutaneous. Error bars represent standard error.

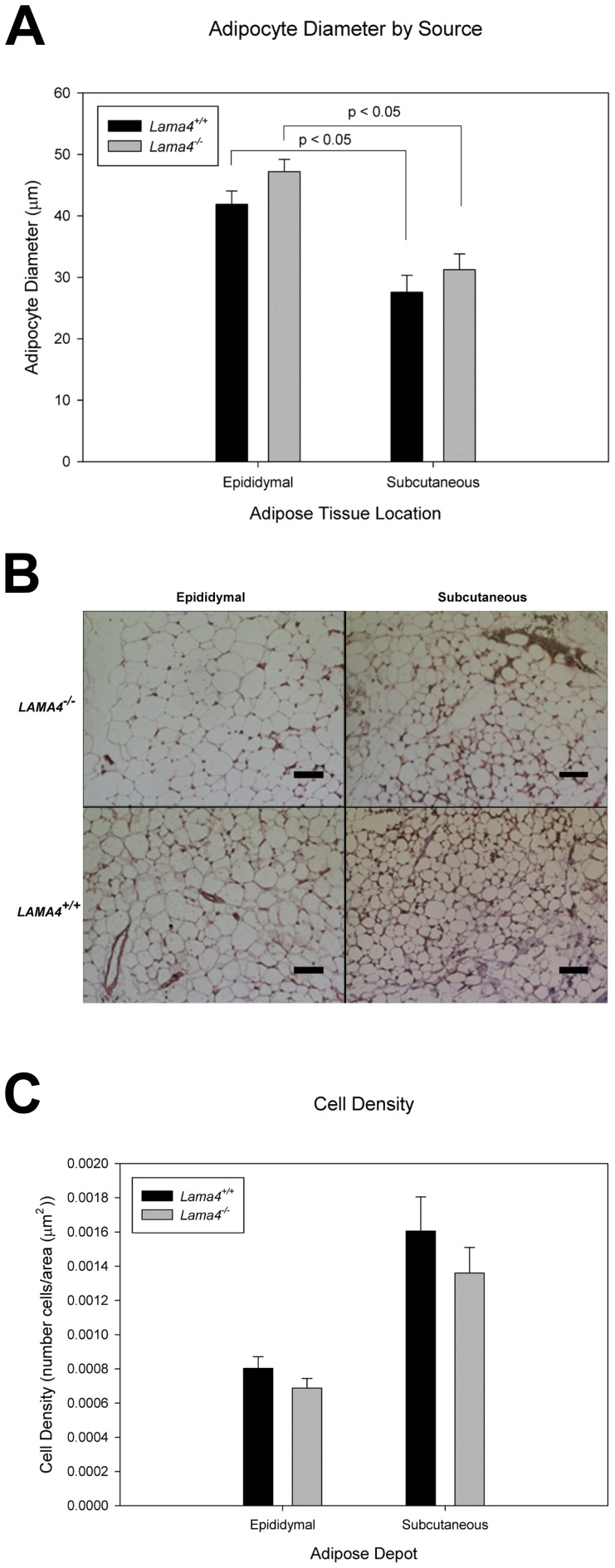

Histomorphometrix analysis was used to further analyze adipose tissue in the different depots. Mean adipocyte size determined from histological stains was greater in epididymal adipose tissue than in the subcutaneous adipose tissue depots in both types of mice (Figure 4B). In both subcutaneous and epididymal depots the mean adipocyte size was greater in the Lama4−/− mice (Figure 4A). Cell density (number of cells per area) was lower in both epididymal and subcutaneous adipose tissue depots for Lama4−/− mice relative to wild-type controls (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Adipocyte diameter in subcutaneous and epididymal adipose tissue depots for age matched Lama4−/− and Lama4+/+mice (A).

For epididymal n = 4 and subcutaneous n = 5, standard error shown as the error bars. There is a statistical difference between epididymal and subcutaneous (P<0.05). Histology images of epididymal and subcutaneous Lama4−/− and Lama4+/+, scale bar equals 300 µm (B). Adipocyte cell density in subcutaneous and epididymal adipose tissue depots for age matched Lama4−/− and Lama4+/+mice (C). For epididymal n = 4 and subcutaneous n = 5, standard error shown as error bars.

Adipose Tissue Function

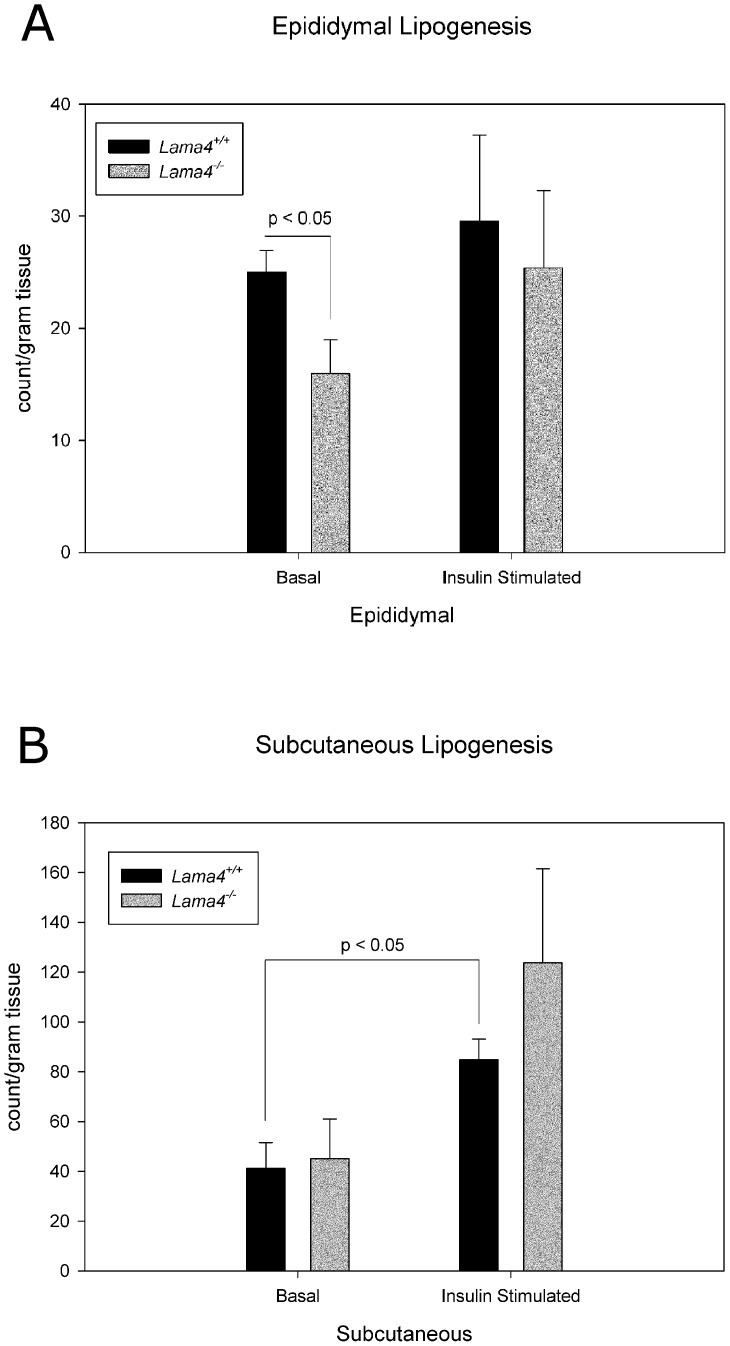

The reduced adiposity may be an indication of altered metabolic function. Adipose tissue function was examined by quantifying basal and insulin-stimulated lipogenesis in adipose tissue isolated from Lama4−/− and wild-type control mice (Figure 5A, B). The epididymal depot of Lama4−/− mice exhibited impaired basal lipogenesis levels (Figure 5A). Interestingly, there were no differences in lipogenesis between subcutaneous adipocytes isolated from Lama4−/− and wild-type control mice (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Lipogenesis levels in adipocytes from epididymal (A) and subcutaneous (B) adipose tissue in age matched Lama4−/− and Lama4+/+mice.

Epididymal fat pad basal lipogenesis is statistically significant between Lama4−/− and Lama4+/+mice (p<0.05). Subcutaneous fat pad in Lama4+/+mice had statistically significant increase in lipogenesis between basal and insulin stimulated (p<0.05). The epididymal and subcutaneous n = 4. Error bars represent standard error.

Discussion

Differentiated adipocytes are surrounded by a thin BM layer. ECM in general, and BM specifically, have been shown to regulate cell behavior in a number of tissues and organs [3–7]. However, there is little knowledge of its role in adipocyte behavior. In this study, we used mice absent in a specific BM protein, laminin α4, to investigate its role in adipose tissue. Using these mice we found a profound influence of laminin α4 on the expansion and function of adipose tissue

Lama4−/− mice were found to gain weight at a much slower rate than wild-type control mice. This occurred during normal aging and was more pronounced on a high fat diet. In fact, Lama4−/− mice did not exhibit any differences in weight whether on normal chow or a high fat diet. Differences from wild type animals did not result from reduced food intake, and a reduction in adipose tissue was observed grossly in the mice deficient in laminin α4. While these results clearly showed that Lama4−/− mice have reduced adiposity, it was initially not clear if this resulted in normal or impaired adipose tissue function. Under both normal and high fat diets, livers in the Lama4−/− mice exhibited little steatosis, suggesting that the decreased body fat did not represent a form of lipodystrophy.

Laminin α4 is present around cells in the kidney, vasculature and muscle and has been shown to regulate different cell behaviors [17]–[26]. In order to further evaluate the role of laminin α4 specifically we isolated adipocytes from these tissues and analyzed their metabolic function. Surprisingly, we found that decreased laminin α4 leads to impaired adipocyte lipogenesis. Insulin stimulated lipogenesis resulted in increased lipogenesis in adipocytes from both Lama4−/− and wild-type control animals indicating that insulin responsiveness appears to be intact, but basal lipogenesis levels were lower in Lama4−/− mice. Interestingly, this difference was depot specific. Adipocytes isolated from epididymal adipose tissue exhibited impaired lipogenesis compared to wild-type controls while the subcutaneous adipose tissue depot had similar lipogenesis to wild-type control. This depot specific impairment is interesting and is further supported by the fact that epididymal adipose tissue depots in Lama4−/− mice significantly are smaller in volume than wild-type control animals at 14 weeks. This difference was observed prior to any measurable differences in total body weight. While the total amount of epididymal adipose tissue in Lama4−/− mice was lower than wild-type controls, the individual adipocytes were larger in Lama4−/− mice relative to wild-type controls. The subcutaneous depots were similar in both total volume and cell size in comparisons between Lama4−/− and wild-type control mice. Overall, these results suggest an impaired function in adipose tissue from mice absent in laminin α4 and that this impairment is manifested primarily in the epididymal depot.

This study shows a profound role for laminin α4 on adipose tissue expansion and function. However, the mechanism underlying this influence is unclear. There is very little knowledge of the role of the ECM on adipocyte behavior. Cell culture and tissue engineering studies have shown that ECM substrata influence adipocyte behavior. In 2D culture “laminin” was found to be more potent than type IV collagen, fibronectin or type I collagen at promoting differentiation of preadipocytes [29]. This study did not distinguish which the specific laminin isoform used, but it is likely that this commercial laminin was purified from a mouse soft tissue tumor that has been shown to contain laminin 111 (α1:β1:γ1). Studies with laminin α4 are less common due to it only recently becoming available commercially. Preadipocytes have been shown to produce LN-411 (α4:β1:γ1) during induction to an adipocyte phenotype [14] and laminin α4-rich ECM mixtures isolated promote greater adipogenesis than ECM lacking α4 [30]–[32]. The α4 chain laminin could directly regulate adipocyte function through modulation of cell receptor signaling.

Laminins containing the α4 chain could also influence adipocyte behavior based on indirect effects on the local cell microenvironment. The BM structure appeared thicker in immunohistochemical stains and previous studies have shown that the vascular BM in Lama4−/− mice is altered structurally [15]. This structural change could reflect altered mechanical properties that may influence adipocyte function [33], [34]. In addition, LN-411, which contains the α4 chain, has a chondroitin sulfate chain [35], [36] which may function to sequester growth factors in the vicinity of a cell. This contributes to the regulation of growth factor availability and signaling near cell surface receptors [37]. Alterations in the laminin composition could alter the ability of the BM to bind growth factors and wild-type control the local concentration of regulatory factors. Laminin α5 has had the gene variants shown to contribute to human body composition and weight [27]. A small subset of extremely obese humans were found to have variants in the laminin genes [28]. Future studies are needed that can address the mechanism including alteration in energy expenditure for the lean phenotype observed in Lama4−/− mice. Additionally, genetic studies investigating laminin α4 in humans could lead to improved understanding of obesity.

Conclusion

In summary, Lama4−/− mice exhibited reduced weight gain in response to both age and high fat diet. The mass and function of the adipose tissue in Lama4−/− mice were altered in a depot-specific manner. In particular, epididymal adipose tissue exhibited decreased mice and altered lipogenesis in Lama4−/− mice, but no differences were observed in the subcutaneous depot. The results suggest that: (1) impaired lipogenesis leads to diminished fat mass in Lama4−/− mice; (2) alterations in lipogenesis are adipose tissue depot-specific; and (3) specific ECM components dramatically influence adipose tissue function.

Supporting Information

Histology of livers of 10 months old male animals. In Lama4−/− animals the histological picture was without signs of steatosis on standard diet, and on high-fat diet it was very mild.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Sofi Ekström, Sigrid Lindqvist, Eva-Karin Atterhag, Teresa Lejenäs, Maria Laisi, Ulla Mikkonen, Maud Petersson and Sharyn Fitzgerald for valuable technical assistance, the SWEGENE Center for Bio-Imaging (CBI), Gothenburg University for technical support regarding Image analysis, Lydia Sorokin for antibodies, Alyssa Appel for histology processing and sectioning and Ingemar Björkhem for analyzing oxysterols. We also would like to express our gratitude to Annika Brännström for critical reading of the manuscript and to Håkan Westerblad for valuable discussions.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

Funding support from University of Chicago Diabetes Research and Training Center (DRTC) Pilot and Feasibility Grant Program DRTC grant P30 DK020595. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Frayn KN (2000) Visceral fat and insulin resistance - causative or correlative? British Journal of Nutrition 83: S71–S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stewart ST, Cutler DM, Rosen AB (2009) Forecasting the effects of obesity and smoking on U.S. life expectancy. N Engl J Med 361: 2252–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aumailley M, Gayraud B (1998) Structure and biological activity of the extracellular matrix. Journal of Molecular Medicine-Jmm 76: 253–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paulsson M (1992) BASEMENT-MEMBRANE PROTEINS - STRUCTURE, ASSEMBLY, AND CELLULAR INTERACTIONS. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 27: 93–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalluri R (2003) Basement membranes: Structure, assembly and role in tumour angiogenesis. Nature Reviews Cancer 3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. Lin CQ, Bissell MJ (1993) MULTIFACETED REGULATION OF CELL-DIFFERENTIATION BY EXTRACELLULAR-MATRIX. Faseb Journal 7: 737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Domogatskaya A, Rodin S, Tryggvason K (2012) Functional Diversity of Laminins. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, Vol 28 28: 523–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kawaguchi N, Toriyama K, Nicodemou-Lena E, Inou K, Torii S, et al. (1998) De novo adipogenesis in mice at the site of injection of basement membrane and basic fibroblast growth factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95: 1062–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kawaguchi N, Toriyama K, Nicodemou-Lena E, Inou K, Torii S, et al. (1999) Reconstituted basement membrane potentiates in vivo adipogenesis of 3T3-F442A cells. Cytotechnology 31: 215–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chavey C, Mari B, Monthouel MN, Bonnafous S, Anglard P, et al. (2003) Matrix metalloproteinases are differentially expressed in adipose tissue during obesity and modulate adipocyte differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kubo Y, Kaidzu S, Nakajima I, Takenouchi K, Nakamura F (2000) Organization of extracellular matrix components during differentiation of adipocytes in long-term culture. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Animal 36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12. Nie J, Sage EH (2009) SPARC Inhibits Adipogenesis by Its Enhancement of beta-Catenin Signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry 284: 1279–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aratani Y, Kitagawa Y (1988) ENHANCED SYNTHESIS AND SECRETION OF TYPE-IV COLLAGEN AND ENTACTIN DURING ADIPOSE CONVERSION OF 3T3-L1 CELLS AND PRODUCTION OF UNORTHODOX LAMININ COMPLEX. Journal of Biological Chemistry 263: 16163–16169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Niimi T, Kumagai C, Okano M, Kitagawa Y (1997) Differentiation-dependent expression of laminin-8 (alpha 4 beta 1 gamma 1) mRNAs in mouse 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Matrix Biology 16: 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thyboll J, Kortesmaa J, Cao RH, Soininen R, Wang L, et al. (2002) Deletion of the laminin alpha 4 chain leads to impaired microvessel maturation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 22: 1194–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neel BA, Brady MJ, Sargis RM (2013) The Endocrine Disrupting Chemical Tolylfluanid Alters Adipocyte Metabolism via Glucocorticoid Receptor Activation. Molecular Endocrinology 27: 394–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sorokin LM, Pausch F, Durbeej M, Ekblom P (1997) Differential expression of five laminin alpha (1–5) chains in developing and adult mouse kidney. Developmental Dynamics 210: 446–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ringelmann B, Roder C, Hallmann R, Maley M, Davies M, et al. (1999) Expression of laminin alpha 1, alpha 2, alpha 4, and alpha 5 chains, fibronectin, and tenascin-C in skeletal muscle of dystrophic 129ReJ dy/dy mice. Experimental Cell Research 246: 165–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Petajaniemi N, Korhonen M, Kortesmaa J, Tryggvason K, Sekiguchi K, et al. (2002) Localization of laminin alpha 4-chain in developing and adult human tissues. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 50: 1113–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patton BL, Miner JH, Chiu AY, Sanes JR (1997) Distribution and function of laminins in the neuromuscular system of developing, adult, and mutant mice. Journal of Cell Biology 139: 1507–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miner JH, Patton BL, Lentz SI, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, et al. (1997) The laminin alpha chains: Expression, developmental transitions, and chromosomal locations of alpha 1–5, identification of heterotrimeric laminins 8–11, and cloning of a novel alpha 3 isoform. Journal of Cell Biology 137: 685–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gu YC, Sorokin L, Durbeej M, Hjalt T, Jonsson JI, et al. (1999) Characterization of bone marrow laminins and identification of alpha 5-containing laminins as adhesive proteins for multipotent hematopoietic FDCP-mix cells. Blood 93: 2533–2542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lefebvre O, Sorokin L, Kedinger M, Simon-Assmann P (1999) Developmental expression and cellular origin of the laminin alpha 2, alpha 4, and alpha 5 chains in the intestine. Developmental Biology 210: 135–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Geberhiwot T, Ingerpuu S, Pedraza C, Neira M, Lehto U, et al. (1999) Blood platelets contain and secrete laminin-8 (alpha 4 beta 1 gamma 1) and adhere to laminin-8 via alpha 6 beta 1 integrin. Experimental Cell Research 253: 723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frieser M, Nockel H, Pausch F, Roder C, Hahn A, et al. (1997) Cloning of the mouse laminin alpha 4 cDNA. Expression in a subset of endothelium. European Journal of Biochemistry 246: 727–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sorokin LM, Maley MAL, Moch H, von der Mark H, von der Mark K, et al. (2000) Laminin alpha 4 and integrin alpha 6 are upregulated in regenerating dy/dy skeletal muscle: Comparative expression of laminin and integrin isoforms in muscles regenerating after crush injury. Experimental Cell Research 256: 500–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Luca M, Chambers MM, Casazza K, Lok KH, Hunter GR, et al. (2008) Genetic variation in a member of the laminin gene family affects variation in body composition in Drosophila and humans. Bmc Genetics 9: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mariman ECM, Bouwman FG, Aller E, van Baak MA, Wang P (2014) High frequency of rare variants with a moderate-to-high predicted biological effect in protocadherin genes of extremely obese. Genes and Nutrition 9: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hausman GJ, Wright JT, Richardson RL (1996) The influence of extracellular matrix substrata on preadipocyte development in serum-free cultures of stromal-vascular cells. Journal of Animal Science 74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30. Uriel S, Huang J-J, Moya ML, Francis ME, Wang R, et al. (2008) The role of adipose protein derived hydrogels in adipogenesis. Biomaterials 29: 3712–3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Uriel S, Labay E, Francis-Sedlak M, Moya M, Weichselbaum R, et al. (2009) Extraction and Assembly of Tissue-Derived Gels for Cell Culture and Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering Part C-Methods 15: 309–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abberton KM, Bortolotto SK, Woods AA, Findlay M, Morrison WA, et al. (2008) Myogel, a novel, basement membrane-rich, extracellular matrix derived from skeletal muscle, is highly adipogenic in vivo and in vitro. Cells Tissues Organs 188. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33. Shoham N, Gottlieb R, Sharabani-Yosef O, Zaretsky U, Benayahu D, et al. (2012) Static mechanical stretching accelerates lipid production in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by activating the MEK signaling pathway. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 302: C429–C441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoham N, Gefen A (2012) Mechanotransduction in adipocytes. Journal of Biomechanics 45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35. Sasaki T, Mann K, Timpl R (2001) Modification of the laminin alpha 4 chain by chondroitin sulfate attachment to its N-terminal domain. Febs Letters 505: 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kortesmaa J, Doi M, Patarroyo M, Tryggvason K (2002) Chondroitin sulphate modification in the alpha 4 chain of human recombinant laminin-8 (alpha 4 beta 1 gamma 1). Matrix Biology 21: 483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Park PW, Reizes O, Bernfield M (2000) Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans: Selective regulators of ligand-receptor encounters. Journal of Biological Chemistry 275: 29923–29926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Histology of livers of 10 months old male animals. In Lama4−/− animals the histological picture was without signs of steatosis on standard diet, and on high-fat diet it was very mild.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.