Abstract

The era of interferon-free antiviral treatments for hepatitis C virus infection has arrived. With increasing numbers of approved antivirals, evaluating all parameters that may influence response is necessary to choose optimal combinations for treatment success. Targeting NS5A has become integral in antiviral combinations in clinical development. Daclatasvir and ledipasvir belong to the NS5A inhibitor class, which directly target the NS5A protein. Alisporivir, a host-targeting antiviral, is a cyclophilin inhibitor that indirectly targets NS5A by blocking NS5A/cyclophilin A interaction. Resistance to daclatasvir and ledipasvir differs from alisporivir, with mutations arising in NS5A domains I and II, respectively. Combining these two classes acting on distinct NS5A domains represents an attractive strategy for potentially effective interferon-free treatments for chronic hepatitis C infection.

Introduction

The treatment landscape for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has evolved substantially with the knowledge and tools to target virtually every step of the viral life cycle with antiviral intervention. In fact, chronic HCV infection can be cured with sufficient antiviral therapy. High rates of sustained virological response at week 12 or 24 after cessation of therapy (SVR12 or 24), defined as undetectable HCV RNA, have been reported for direct-acting antiviral combinations. Direct-acting antivirals bind and target viral proteins, such as the serine protease NS3/4A and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase NS5B, against which antivirals are currently being approved. Direct-acting antivirals against the NS5A protein are now in advanced clinical trials, lagging behind drug discovery efforts due to its lack of recognized enzymatic activity despite being involved in multiple stages of the viral life cycle [1,2]. On the other hand, cyclophilin inhibitors, which are host-targeting antivirals, bind cyclophilin A, a host protein, but indirectly affect NS5A by disrupting NS5A/cyclophilin A interactions. NS5A is a multi-functional protein comprised of ~447 amino acids that are loosely classified into three structural domains with an N-terminal amphipathic alpha helix anchoring it to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane [3]. The pleiotropy of NS5A can be attributed to the largely unfolded nature of domains II and III [1,3–8]. Domain II binds to numerous host proteins and some of these interactions have been linked to RNA replication [5,9–12]. Domain III is important for virus assembly but dispensable for replication [5,13,14]. On the other hand, domain I contains Zn2+- and RNA-binding motifs and has been crystallized as a dimer [4,9,15–17]. It has been suggested that this dimer oligomerizes to form a protective replication compartment that tethers the HCV RNA to intracellular membranes [18–21]. In addition to their flexibility, domains II and III have less sequence conservation between genotypes compared to domain I [6,7]. HCV can be grouped into seven genotypes and a number of subtypes (a,b, etc.), with distinct geographical distribution and susceptibility to inhibitors [22,23]. Selective targeting of genotype 1 has been driven by its predominance in developed countries and use of genotype 1b replicon systems as the standard for drug development [22]. Although effective against all genotypes, NS5A inhibitors display a lower EC50 in genotype 1 than genotype 3. This difference in antiviral activity can be attributed to two factors: (1) only NS5A inhibitors exhibiting low picomolar potency against genotype 1a and 1b replicons during initial drug screening studies were selected for further development [24–29], and (2) the heterogeneity of the NS5A gene among genotypes.

NS5A and cyclophilin inhibitors

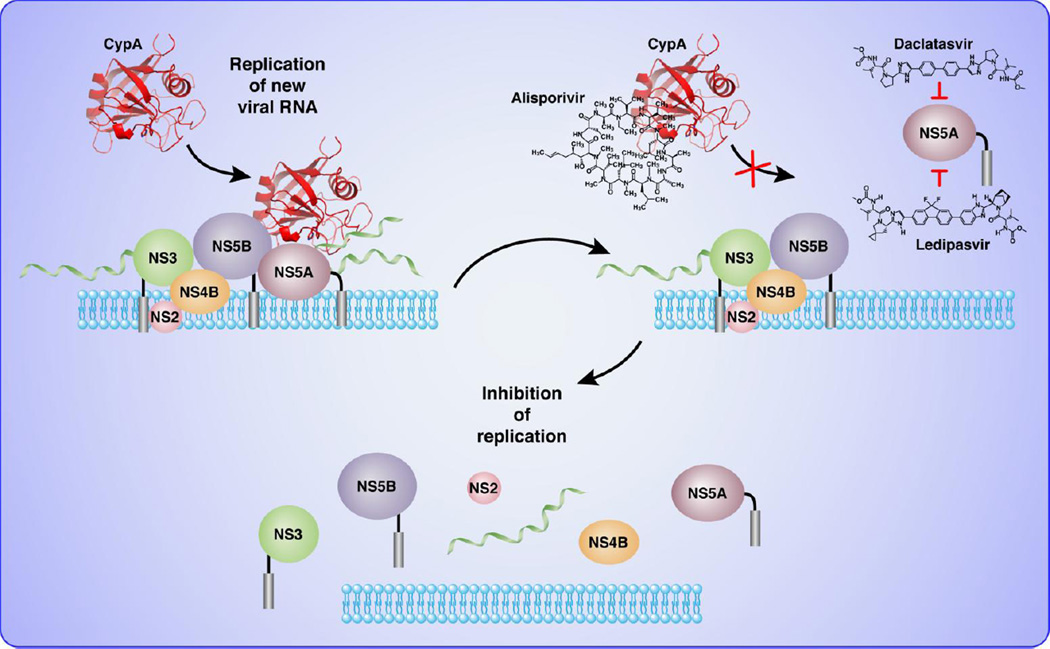

NS5A inhibitors are direct-acting antivirals that target and bind domain I of NS5A with resistance mutations mapping to this domain [26, 27]. The most advanced NS5A inhibitors are daclatasvir (BMS-790052), ledipasvir (GS-5885) and ABT-267 (not discussed here). Other NS5A inhibitors in clinical development but not discussed in this review include GSK-805, PPI-668, IDX-719, BMS-766, GS-5816, ACH-3102, and MK-8742 [30]. These inhibitors are among the most potent antivirals discovered, with low picomolar activity in cell-based assays and rapid virological response in patients [26,31–33]. In fact, the extremely rapid rate of HCV RNA decline in single ascending dose trials for daclatasvir required the re-evaluation of the estimated half-life of the circulating virus, which was reduced from 2.5 hours to 45 minutes [34]. The potency of NS5A inhibitors can be attributed to the pleiotropy of NS5A, which can amplify inhibitory effects by interfering with multiple essential functions. NS5A inhibitors have been proposed to efficiently block both RNA replication and virion assembly (Figure 1) [34]. Despite their high potency, however, NS5A inhibitors, such as daclatasvir and ledipasvir, have a low barrier to resistance with resistant variants showing high fitness [29,32]. Distinct from direct-acting antivirals, host-targeting antivirals target and bind host factors that are required for viral replication, translation, assembly and release. Host-targeting antivirals are exemplified by cyclophilin inhibitors such as alisporivir (DEB025) and SCY-635 [35,36]. Although the primary target of cyclophilin inhibitors is cyclophilin A, these antivirals indirectly inhibit NS5A by disrupting domain II-mediated NS5A/cyclophilin A interactions that are required for HCV replication [37,38]. The most advanced host-targeting antiviral is alisporivir, which is currently in clinical trials as part of interferon-free treatment combinations. Alisporivir has a high barrier to resistance with resistance-associated mutations mapping to domain II of NS5A [11,39,40] (C Tiongyip et al., abstract R_14, 6th International Workshop on Hepatitis C, Resistance and New Compounds, Cambridge, MA, June 2011).

Figure 1.

Two targets, one protein. Data from resistance mutations mapping reveal that daclatasvir or ledipasvir target domain I of NS5A while alisporivir leads to mutations in domain II of NS5A.

Resistance parameters

HCV exists in every patient as a large population of genetically distinct variants comprising a quasispecies due to its high turnover rate (about 1012 viruses per day) and high mutation frequency [41]. In theory, every possible pre-existing mutation is present within any given patient prior to antiviral treatment, albeit at very low percentages [42]. Therefore, the barrier to resistance of any given inhibitor is defined as the threshold above which a viral population acquires a sufficient number of mutations that confers resistance. This threshold is influenced by a number of factors [43–45], including the mutational bias of the HCV RNA polymerase in favor of transitions over transversions [46], such that a low barrier to resistance may require transitions or fewer mutations to render an inhibitor ineffective. In contrast, a high barrier to resistance may require transversions and/or more mutations. Another factor that influences the barrier to resistance is the in vivo fitness of the resistant viral population [47]. Resistant viral variants that have escaped the antiviral effects of an inhibitor usually have reduced replication fitness [48]. However, under selective drug pressure, resistant variants continue to replicate, eventually becoming the dominant viral strain within the quasispecies; thus, resulting in decreased susceptibility to an inhibitor. This is further compounded by the emergence of secondary mutations that allows for more efficient replication. Inhibitor exposure also influences the emergence of resistance. Resistant variants will be inhibited if drug exposure levels, as measured by trough plasma concentrations, are far above their IC90 values against these resistant variants. Therefore, even with combinations of antivirals with high barriers to resistance, low exposure levels will result in resistance and virological breakthroughs.

Daclatasvir (BMS-790052)

Despite its exceptional potency and sharp initial viral decline in patients, resistant variants emerged relatively fast in 14-day multiple-ascending dose monotherapy studies with daclatasvir [27,49]. In fact, clonal analysis showed >95% of viruses in populations with virological breakthroughs were resistant variants [49]. Major substitutions in NS5A for genotype 1a were M28T, Q30R/H, L31V, and Y93H while resistant variants for genotype 1b were L31V and Y93H, and their effects were consistently observed in vitro and in clinical studies [49]. Resistant mutations were still observed in a follow-up study of up to 48 weeks following daclatasvir exposure [50], suggesting that resistant variants were relatively fit under selective drug pressure and persisted over time. These substitutions map to domain I of NS5A and have been detected in untreated patients. Although baseline pre-existing substitutions have minimal impact on the potency of daclatasvir, they may significantly affect the emerging resistance profile [51], and can be a reason for treatment failure. In fact, 58% of genotype 1b-infected patients with these mutations failed therapy [52]. To this extent, daclatasvir is being developed for use in combination regimens with other direct-acting antivirals with non-overlapping resistance profiles. A ribavirin- and interferon-free daclatasvir-based regimen is currently in development in the United States and in regulatory review in Japan for treatment of patients infected with HCV genotype 1b (Bristol-Myers Squibb press release, URL: http://news.bms.com/press-release/bristol-myers-squibb-receives-us-fda-breakthrough-therapy-designation-all-oral-daclata). Data from Phase III trials (Table 1) showed an overall 85% SVR24 and low rates of adverse events and discontinuations in HCV genotype-1b-infected patients intolerant to or non-eligible for interferon and prior non-responders [53]. The regimen consists of daclatasvir administered at 60 mg qd (once daily) and asunaprevir, an NS3/4A protease inhibitor, administered at 100 mg bid (twice daily). This dual regimen is not as effective against harder-to-treat genotype 1a, probably due to a higher number of pre-existing and treatment-emergent resistance mutations. Asunaprevir is also not active against genotypes 2 and 3. Adding the non-nucleoside NS5B inhibitor, BMS-791325 (75 mg bid), to this regimen raised SVR12 rates to 92% in genotype 1 treatment-naïve patients, with 82% of enrolled patients having genotype 1a. An interferon-free regimen of daclatasvir at 60 mg qd was evaluated in a small study with sofosbuvir (GS-7977), a nucleotide NS5B inhibitor, at 400 mg qd with or without ribavirin for 24 weeks in a total of 44 treatment-naïve patients infected with HCV genotypes 2 and 3 [54]. The study was designed to have a one-week lead-in period of sofosbuvir to determine whether initial HCV suppression would reduce the emergence of daclatasvir-related resistance mutations. High overall SVR12 and SVR24 rates of 91% and 93%, respectively, were observed, with similar responses regardless of ribavirin status. Pre-treatment mutations in NS5A known to confer loss of susceptibility to daclatasvir in vitro were observed in 19 out of 44 patients studied. All patients with pre-existing daclatasvir-related resistance mutations achieved SVR except for one patient infected with HCV genotype 3 who did not receive ribavirin and had a pre-existing A30K mutation in NS5A. No other resistance-associated mutations were detected at time of relapse, suggesting that development of resistance is uncommon in this regimen. Of note, the combination of sofosbuvir with ribavirin has been approved to treat patients infected with genotype 2 strains for 12 weeks, and patients infected with genotype 3 strains for 24 weeks (Gilead Sciences press release, URL: http://www.gilead.com/news/press-releases/2013/12/us-food-and-drug-administration-approves-gileads-sovaldi-sofosbuvir-for-the-treatment-of-chronic-hepatitis-c).

Table 1.

Direct-acting and host-targeting antivirals targeting NS5A achieve high SVR rates in interferon-free regimens with major resistance mutations listed.

| NS5A inhibitors | Resistance barrier |

Resistance mutations in NS5A |

SVR12 or 24 | Clinical trials reference |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct-acting | Daclatasvir (BMS-790052) | Low | Domain I

|

+ Asunparevir | 85% (n=222) in GT-1b interferon-intolerant/ineligible patients or prior non-responders | [53] |

| Ledipasvir (GS-5885) | Low | Domain I

|

+ Sofosbuvir | 97.7% (n=214) in GT-1 treatment-naïve patients | Gilead Sciences press release, URL: http://www.gilead.com/news/press-releases/2014/2/gilead-files-for-us-approval-of-ledipasvirsofosbuvir-fixeddose-combination-tablet-for-genotype-1-hepatitis-c | |

| 93.6% (n=109) in GT-1 treatment-experienced patients | ||||||

| 99.1 (n=109) in GT-1 treatment-experienced patients including 20% with compensated cirrhosis | ||||||

| 95.4% (n=216) in GT-1a treatment-naïve patients with no cirrhosis | ||||||

| Host-targeting | Alisporivir (DEB-025) | High | Domain II

|

+ Ribavirin | >90% (n=61) in GT-2 and 3 treatment-naïve patients | JM Pawlotsky et al., abstract 233, 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Boston, MA, November 2012 |

Ledipasvir (GS-5885)

As with daclatasvir, ledipasvir has a low barrier to resistance. In a monotherapy study with ledipasvir dosed 1, 3, 10, 30, or 90 mg once daily, major baseline pre-existing substitutions for genotype 1 were M28T, Q30R/H, L31M, Y93C/H [55]. This was associated with reduced treatment response in patients infected with HCV genotype 1a. A complex mixture of resistant variants was detected at day 4 or 14, with major substitutions at Q30 and L31 for genotype 1a. For genotype 1b, Y93H was the major substitution detected in 100% of all patients at day 4 or 14. As with daclatasvir, these substitutions map to domain I of NS5A, indicating similar modes of action. Phenotypic analyses of subject-derived resistance mutations showed >30-fold reduced susceptibility to ledipasvir. The resistant variants, however, remain fully susceptible to other classes of direct-acting antivirals. Ledipasvir is currently in regulatory review in the United States for use in a ribavirin- and interferon-free fixed-dose combination regimen to treat patients infected with HCV genotypes 1a and 1b (Gilead Sciences press release, URL: http://www.gilead.com/news/press-releases/2014/2/gilead-files-for-us-approval-of-ledipasvirsofosbuvir-fixeddose-combination-tablet-for-genotype-1-hepatitis-c). The regimen consists of ledipasvir administered at 90 mg qd with the NS5B inhibitor, sofosbuvir, administered at 400 mg qd. This regimen is supported by results of three Phase III clinical trials involving 1,952 patients infected with HCV genotype 1. High SVR12 rates of 97.7% and 93.6% were achieved in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients, respectively (Table 1). A 99.1% SVR24 rate was observed in treatment-experienced patients that included those with compensated cirrhosis (Table 1). This combination is also effective in harder-to-treat genotype 1a with a 95.4% SVR12 (Table 1).

Alisporivir (DEB025)

The most advanced host-targeting antiviral, alisporivir, indirectly inhibits NS5A by neutralizing the isomerase activity of cyclophilin A, which binds NS5A and is essential for HCV replication [39,56–63]. The analysis of results (Table 1) of Phase II clinical trials from patients who completed treatment according to protocol showed an interferon-free combination of alisporivir with ribavirin to achieve SVR24 rates >90%, with low virological breakthrough, low post-treatment relapse and a favorable safety profile in treatment-naïve patients infected with HCV genotype 2 and 3 (JM Pawlotsky et al., abstract 233, 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Boston, MA, November 2012). With regard to genotype efficacy, alisporivir is more potent against treatment-naïve patients infected with genotypes 2 and 3, emphasizing the major advantage it may have in treating genotype-3-infected patients over NS5A inhibitors [64,65]. Also in contrast to NS5A inhibitors, alisporivir has a high barrier to resistance, with in vitro resistance mutations mapping to domain II of NS5A [11,38–40] (C Tiongyip et al., abstract R_14, 6th International Workshop on Hepatitis C, Resistance and New Compounds, Cambridge, MA, June 2011). Phenotypic analyses of NS5A mutations during alisporivir selection pressure in vitro revealed that D320E constantly arose in genotype 1a and 1b but only reduced susceptibility to alisporivir by 2–3 fold and can be overcome with adequate alisporivir exposure. Additional studies suggest that a combination of mutations (e.g., D320E/Y321N) is required to confer resistance to alisporivir [11,66]. This data correlates well with clinical studies where multiple mutations are required to substantially alter (>5-fold) the EC50 to alisporivir in clinical isolates from patients (JM Pawlotsky et al., abstract 2960, 48th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, Amsterdam, NL, April 2013). In this clinical study, three mutations in the NS5A domain II were selected, which individually conferred ≤5-fold reduced susceptibility to alisporivir in vitro. A combination of two or more mutations was required to further reduce susceptibility, generally with compromised replicative fitness, which is consistent with the high barrier to resistance for host-targeting alisporivir (C Tiongyip et al., abstract R_14, 6th International Workshop on Hepatitis C, Resistance and New Compounds, Cambridge, MA, June 2011). Recent in vitro data revealed that combinations of alisporivir with NS5A inhibitors had synergistic antiviral effects on genotypes 2 and 3 [67]. No cross-resistance was observed in that alisporivir was fully active against resistant variants to direct-acting antivirals and alisporivir-resistant variants were fully susceptible to NS5A inhibitors. These results will need to be confirmed in clinical studies. As such, incorporating alisporivir into interferon-free daclatasvir- or ledipasvir-based treatment combinations may benefit patients infected with HCV genotypes 2 or 3. Since these inhibitors target two distinct domains of NS5A, treatment-emergent resistance mutations that may arise from low-resistance-barrier daclatasvir or ledipasvir will not significantly impair treatment response, and this dual mechanism of antiviral action may be the best drug combination for alisporivir (Figure 1). Of note, genotype 3 is associated with a higher risk of hepatic steatosis [68] and progressive liver disease [69]. Also, individualized therapy, rather than fixed-dose antiviral combinations, may still be necessary for patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, or patients with HIV co-infections. Incorporating alisporivir into these therapies is an attractive notion but remains to be demonstrated.

Conclusions

The best way to prevent the emergence of resistance-associated mutations is rapid and profound viral suppression that can be best achieved by combining several inhibitors with potent antiviral activity, high barrier to resistance, different mechanisms of action and no cross-resistance [44]. Strict patient adherence is also mandatory to prevent the emergence of resistance-associated mutations due to undulating drug exposure levels. These criteria also seem to overcome the role of host factors on treatment response such as age, ethnicity, gender, obesity, human leukocyte antigen type, baseline levels of interferon-stimulated genes and interferon λ3 (formerly interleukin 28B) polymorphisms [70,71]. High-resistance barrier drugs such as alisporivir and second-generation direct-acting NS5A inhibitors like MK-8742 and ACH-3102, which retain substantial levels of potency against resistant variants from daclatasvir or ledipasvir [72,73], are in development so that if virological breakthrough does occur, resistance, at least in the context of NS5A, may be futile. Monitoring resistance in treatment failures will have to be an important consideration in choosing future antiviral combinations, and whether these resistant variants impair future treatment options remains to be elucidated.

Resistance mutations to daclatasvir and ledipasvir map to domain I of NS5A.

Resistance mutations to alisporivir map to domain II of NS5A.

Resistance can be delayed with drug combinations acting on both NS5A domains.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Public Health Service grant no. AI087746 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). This is publication no. 27009 from the Department of Immunology & Microbial Science, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Macdonald A, Harris M. Hepatitis C virus NS5A: tales of a promiscuous protein. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2485–2502. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He YSK, Tan SL. HCV NS5A: a multifunctional regulator of cellular pathways and virus replication. In: SL T, editor. Hepatitis C Virus: Genome and Molecular Biology. Horizon Bioscience; 2006. pp. 267–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brass V, Bieck E, Montserret R, Wolk B, Hellings JA, Blum HE, Penin F, Moradpour D. An amino-terminal amphipathic alpha-helix mediates membrane association of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8130–8139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tellinghuisen TL, Marcotrigiano J, Gorbalenya AE, Rice CM. The NS5A protein of hepatitis C virus is a zinc metalloprotein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48576–48587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tellinghuisen TL, Foss KL, Treadaway JC, Rice CM. Identification of residues required for RNA replication in domains II and III of the hepatitis C virus NS5A protein. J Virol. 2008;82:1073–1083. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00328-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang Y, Ye H, Kang CB, Yoon HS. Domain 2 of nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) of hepatitis C virus is natively unfolded. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11550–11558. doi: 10.1021/bi700776e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanoulle X, Verdegem D, Badillo A, Wieruszeski JM, Penin F, Lippens G. Domain 3 of non-structural protein 5A from hepatitis C virus is natively unfolded. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381:634–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanoulle X, Badillo A, Verdegem D, Penin F, Lippens G. The domain 2 of the HCV NS5A protein is intrinsically unstructured. Protein Pept Lett. 2010;17:1012–1018. doi: 10.2174/092986610791498920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang L, Hwang J, Sharma SD, Hargittai MR, Chen Y, Arnold JJ, Raney KD, Cameron CE. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) is an RNA-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36417–36428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster TL, Belyaeva T, Stonehouse NJ, Pearson AR, Harris M. All three domains of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural NS5A protein contribute to RNA binding. J Virol. 2010;84:9267–9277. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00616-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatterji U, Lim P, Bobardt MD, Wieland S, Cordek DG, Vuagniaux G, Chisari F, Cameron CE, Targett-Adams P, Parkinson T, et al. HCV resistance to cyclosporin A does not correlate with a resistance of the NS5A-cyclophilin A interaction to cyclophilin inhibitors. J Hepatol. 2010;53:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Chassey B, Navratil V, Tafforeau L, Hiet MS, Aublin-Gex A, Agaugue S, Meiffren G, Pradezynski F, Faria BF, Chantier T, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection protein network. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:230. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tellinghuisen TLFK, Treadaway JC. Regulation of hepatitis C virion production via phosphorylation of the NS5A protein. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:e1000032. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appel N, Zayas M, Miller S, Krijnse-Locker J, Schaller T, Friebe P, Kallis S, Engel U, Bartenschlager R. Essential role of domain III of nonstructural protein 5A for hepatitis C virus infectious particle assembly. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000035. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tellinghuisen TL, Marcotrigiano J, Rice CM. Structure of the zinc-binding domain of an essential component of the hepatitis C virus replicase. Nature. 2005;435:374–379. doi: 10.1038/nature03580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Love RA, Brodsky O, Hickey MJ, Wells PA, Cronin CN. Crystal structure of a novel dimeric form of NS5A domain I protein from hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2009;83:4395–4403. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02352-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang J, Huang L, Cordek DG, Vaughan R, Reynolds SL, Kihara G, Raney KD, Kao CC, Cameron CE. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A: biochemical characterization of a novel structural class of RNA-binding proteins. J Virol. 2010;84:12480–12491. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01319-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appel N, Schaller T, Penin F, Bartenschlager R. From structure to function: new insights into hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9833–9836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binder M, Sulaimanov N, Clausznitzer D, Schulze M, Huber CM, Lenz SM, Schloder JP, Trippler M, Bartenschlager R, Lohmann V, et al. Replication vesicles are load- and choke-points in the hepatitis C virus lifecycle. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003561. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egger D, Wolk B, Gosert R, Bianchi L, Blum HE, Moradpour D, Bienz K. Expression of hepatitis C virus proteins induces distinct membrane alterations including a candidate viral replication complex. J Virol. 2002;76:5974–5984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.5974-5984.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romero-Brey I, Merz A, Chiramel A, Lee JY, Chlanda P, Haselman U, Santarella-Mellwig R, Habermann A, Hoppe S, Kallis S, et al. Three-dimensional architecture and biogenesis of membrane structures associated with hepatitis C virus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003056. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheel TK, Rice CM. Understanding the hepatitis C virus life cycle paves the way for highly effective therapies. Nat Med. 2013;19:837–849. doi: 10.1038/nm.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simmonds P. The Origins of Hepatitis C Virus. In: Bartenschlager R, editor. Hepatitis C Virus: From Molecular Virology to Antiviral Therapy. Springer; 2013. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belda O, Targett-Adams P. Small molecule inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus-encoded NS5A protein. Virus Res. 2012;170:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez D, Zhou N, Ueland J, Monikowski A, McPhee F. Natural prevalence of NS5A polymorphisms in subjects infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 and their effects on the antiviral activity of NS5A inhibitors. J Clin Virol. 2013;57:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gao M, Nettles RE, Belema M, Snyder LB, Nguyen VN, Fridell RA, Serrano-Wu MH, Langley DR, Sun JH, O'Boyle DR, 2nd, et al. Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect. Nature. 2010;465:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature08960. * First report of the discovery of daclatasvir, a first in class of highly potent NS5A inhibitors, which validates NS5A as an excellent antiviral target for HCV therapy. This led to other discoveries of exceptionally potent NS5A inhibitors.

- 27.Fridell RA, Qiu D, Wang C, Valera L, Gao M. Resistance analysis of the hepatitis C virus NS5A inhibitor BMS-790052 in an in vitro replicon system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3641–3650. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00556-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fridell RA, Qiu D, Valera L, Wang C, Rose RE, Gao M. Distinct functions of NS5A in hepatitis C virus RNA replication uncovered by studies with the NS5A inhibitor BMS-790052. J Virol. 2011;85:7312–7320. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00253-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheel TK, Gottwein JM, Mikkelsen LS, Jensen TB, Bukh J. Recombinant HCV variants with NS5A from genotypes 1–7 have different sensitivities to an NS5A inhibitor but not interferon-alpha. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1032–1042. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao M. Antiviral activity and resistance of HCV NS5A replication complex inhibitors. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Link JO, Taylor JG, Xu L, Mitchell M, Guo H, Liu H, Kato D, Kirschberg T, Sun J, Squires N, et al. Discovery of Ledipasvir (GS-5885): A Potent, Once-Daily Oral NS5A Inhibitor for the Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection. J Med Chem. 2014;57:2033–2046. doi: 10.1021/jm401499g. * Details the series of structural modifications that led to ledipasvir, a NS5A inhibitor with optimized preclinical potency and pharmacokinetics. This profile translated to clinical efficacy where ledipasvir monotherapy was demonstrated to reduce viral loads and have prolonged plasma trough concentrations.

- 32.Nettles RE, Gao M, Bifano M, Chung E, Persson A, Marbury TC, Goldwater R, DeMicco MP, Rodriguez-Torres M, Vutikullird A, et al. Multiple ascending dose study of BMS-790052, a nonstructural protein 5A replication complex inhibitor, in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 1. Hepatology. 2011;54:1956–1965. doi: 10.1002/hep.24609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawitz EJ, Gruener D, Hill JM, Marbury T, Moorehead L, Mathias A, Cheng G, Link JO, Wong KA, Mo H, et al. A phase 1, randomized, placebo-controlled, 3-day, dose-ranging study of GS-5885, an NS5A inhibitor, in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2012;57:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guedj J, Dahari H, Rong L, Sansone ND, Nettles RE, Cotler SJ, Layden TJ, Uprichard SL, Perelson AS. Modeling shows that the NS5A inhibitor daclatasvir has two modes of action and yields a shorter estimate of the hepatitis C virus half-life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3991–3996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203110110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paeshuyse J, Kaul A, De Clercq E, Rosenwirth B, Dumont JM, Scalfaro P, Bartenschlager R, Neyts J. The non-immunosuppressive cyclosporin DEBIO-025 is a potent inhibitor of hepatitis C virus replication in vitro. Hepatology. 2006;43:761–770. doi: 10.1002/hep.21102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hopkins S, Scorneaux B, Huang Z, Murray MG, Wring S, Smitley C, Harris R, Erdmann F, Fischer G, Ribeill Y. SCY-635, a novel nonimmunosuppressive analog of cyclosporine that exhibits potent inhibition of hepatitis C virus RNA replication in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:660–672. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00660-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang F, Robotham JM, Nelson HB, Irsigler A, Kenworthy R, Tang H. Cyclophilin A is an essential cofactor for hepatitis C virus infection and the principal mediator of cyclosporine resistance in vitro. J Virol. 2008;82:5269–5278. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02614-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waller H, Chatterji U, Gallay P, Parkinson T, Targett-Adams P. The use of AlphaLISA technology to detect interaction between hepatitis C virus-encoded NS5A and cyclophilin A. J Virol Methods. 2010;165:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coelmont L, Hanoulle X, Chatterji U, Berger C, Snoeck J, Bobardt M, Lim P, Vliegen I, Paeshuyse J, Vuagniaux G, et al. DEB025 (Alisporivir) inhibits hepatitis C virus replication by preventing a cyclophilin A induced cis-trans isomerisation in domain II of NS5A. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Rivera JA, Bobardt M, Chatterji U, Hopkins S, Gregory MA, Wilkinson B, Lin K, Gallay PA. Multiple mutations in hepatitis C virus NS5A domain II are required to confer a significant level of resistance to alisporivir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5113–5121. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00919-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Layden TJ, Perelson AS. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science. 1998;282:103–107. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rong L, Dahari H, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS. Rapid emergence of protease inhibitor resistance in hepatitis C virus. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:30ra32. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pawlotsky JM. Treatment failure and resistance with direct-acting antiviral drugs against hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2011;53:1742–1751. doi: 10.1002/hep.24262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vermehren J, Sarrazin C. The role of resistance in HCV treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:487–503. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C Virus: Standard-of-Care Treatment. In: de Clercq E, editor. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 67. Elsevier; 2013. pp. 169–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Powdrill MH, Tchesnokov EP, Kozak RA, Russell RS, Martin R, Svarovskaia ES, Mo H, Kouyos RD, Gotte M. Contribution of a mutational bias in hepatitis C virus replication to the genetic barrier in the development of drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20509–20513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105797108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welsch C, Zeuzem S. Clinical relevance of HCV antiviral drug resistance. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarrazin C, Zeuzem S. Resistance to direct antiviral agents in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:447–462. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fridell RA, Wang C, Sun JH, O'Boyle DR, 2nd, Nower P, Valera L, Qiu D, Roberts S, Huang X, Kienzle B, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of variants resistant to hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A replication complex inhibitor BMS-790052 in humans: in vitro and in vivo correlations. Hepatology. 2011;54:1924–1935. doi: 10.1002/hep.24594. * Sequence analysis of clinical isolates following daclatasvir monotherapy identified the main resistance-associated mutations in NS5A, which correlated well with NS5A resistant variants identified in vitro.

- 50.Wang C, Sun JH, O'Boyle DR, 2nd, Nower P, Valera L, Roberts S, Fridell RA, Gao M. Persistence of resistant variants in hepatitis C virus-infected patients treated with the NS5A replication complex inhibitor daclatasvir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2054–2065. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02494-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun JH, O'Boyle IiDR, Zhang Y, Wang C, Nower P, Valera L, Roberts S, Nettles RE, Fridell RA, Gao M. Impact of a baseline polymorphism on the emergence of resistance to the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A replication complex inhibitor, BMS-790052. Hepatology. 2012;55:1692–1699. doi: 10.1002/hep.25581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McPhee FTJ, Chayama K, Miyagoshi H, Tamura e, Ishikawa H, Hughes E, Hernandez D, Kumada H. Analysis of HCV resistant variants in a phase 3 trial of daclatasvir combined with asunaprevir for Japanese patients with genotype 1b infection. Hepatology. 2013;58:749A. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kumada H, Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, Ido A, Yamamoto K, Takaguchi K, et al. Daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for chronic HCV genotype 1b infection. Hepatology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hep.27113. 10.1002/hep.27113. * Results of Phase III data showing high SVR rates for a dual regimen of daclatasvir and asunaprevir in patients infected with HCV genotype 1b who are intolerant to or non-eligible for interferon and prior nonresponders.

- 54.Sulkowski MS, Gardiner DF, Rodriguez-Torres M, Reddy KR, Hassanein T, Jacobson I, Lawitz E, Lok AS, Hinestrosa F, Thuluvath PJ, et al. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:211–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wong KA, Worth A, Martin R, Svarovskaia E, Brainard DM, Lawitz E, Miller MD, Mo H. Characterization of Hepatitis C virus resistance from a multiple-dose clinical trial of the novel NS5A inhibitor GS-5885. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:6333–6340. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02193-12. * Viral sequencing and phenotypic analysis of clinical isolates identified baseline and treatment-emergent resistance mutations in NS5A, which conferred reduced susceptibilites to ledipasvir.

- 56.Chatterji U, Bobardt M, Selvarajah S, Yang F, Tang H, Sakamoto N, Vuagniaux G, Parkinson T, Gallay P. The isomerase active site of cyclophilin A is critical for hepatitis C virus replication. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16998–17005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaul A, Stauffer S, Berger C, Pertel T, Schmitt J, Kallis S, Zayas M, Lohmann V, Luban J, Bartenschlager R. Essential role of cyclophilin A for hepatitis C virus replication and virus production and possible link to polyprotein cleavage kinetics. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000546. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Z, Yang F, Robotham JM, Tang H. Critical role of cyclophilin A and its prolyl-peptidyl isomerase activity in the structure and function of the hepatitis C virus replication complex. J Virol. 2009;83:6554–6565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02550-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang F, Robotham JM, Grise H, Frausto S, Madan V, Zayas M, Bartenschlager R, Robinson M, Greenstein AE, Nag A, et al. A major determinant of cyclophilin dependence and cyclosporine susceptibility of hepatitis C virus identified by a genetic approach. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001118. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chatterji U, Bobardt MD, Lim P, Gallay PA. Cyclophilin A-independent recruitment of NS5A and NS5B into hepatitis C virus replication complexes. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:1189–1193. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.018531-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernandes F, Ansari IU, Striker R. Cyclosporine inhibits a direct interaction between cyclophilins and hepatitis C NS5A. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gregory MA, Bobardt M, Obeid S, Chatterji U, Coates NJ, Foster T, Gallay P, Leyssen P, Moss SJ, Neyts J, et al. Preclinical characterization of naturally occurring polyketide cyclophilin inhibitors from the sanglifehrin family. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1975–1981. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01627-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hopkins S, Bobardt M, Chatterji U, Garcia-Rivera JA, Lim P, Gallay PA. The cyclophilin inhibitor SCY-635 disrupts hepatitis C virus NS5A-cyclophilin A complexes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3888–3897. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00693-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Guedj JYJ, Levi M, Li B, Kern S, Naoumov NV, Perelson AS. Modeling viral kinetics and treatment outcome during alisporivir interferon-free treatment in hepatitis C virus genotype 2 and 3 patients. Hepatology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hep.26989. 10.1002/hep.26989. * Characterization viral kinetics observed in a Phase IIb trial of patients infected with genotypes 2 or 3. Assuming full compliance and the same proportion of suboptimal responders, they predicted high SVR rates for an interferon-free regimen of alisporivir and ribavirin.

- 65. Flisiak R, Horban A, Gallay P, Bobardt M, Selvarajah S, Wiercinska-Drapalo A, Siwak E, Cielniak I, Higersberger J, Kierkus J, et al. The cyclophilin inhibitor Debio-025 shows potent anti-hepatitis C effect in patients coinfected with hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus. Hepatology. 2008;47:817–826. doi: 10.1002/hep.22131. * Alisporivir monotherapy studies demonstrating first preliminary clinical proof of concept that cyclophilin inhibition is a valid approach for HCV therapy.

- 66.Grise H, Frausto S, Logan T, Tang H. A conserved tandem cyclophilin-binding site in hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A regulates Alisporivir susceptibility. J Virol. 2012;86:4811–4822. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06641-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chatterji U, Garcia-Rivera JA, Baugh J, Gawlik K, Wong KA, Zhong W, Brass CA, Naoumov NV, Gallay PA. Alisporivir plus NS5A Inhibitor Combination Provides Additive to Synergistic Anti-HCV Activity Without Detectable Cross Resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00016-14. 10.1128/AAC.00016-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Negro F. Steatosis and insulin resistance in response to treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(Suppl 1):42–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour JF, Lammert F, Duarte-Rojo A, Heathcote EJ, Manns MP, Kuske L, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308:2584–2593. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.144878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kau A, Vermehren J, Sarrazin C. Treatment predictors of a sustained virologic response in hepatitis B and C. J Hepatol. 2008;49:634–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Horner SM, Gale M., Jr Regulation of hepatic innate immunity by hepatitis C virus. Nat Med. 2013;19:879–888. doi: 10.1038/nm.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu RKR, Mann P, Ingravallo P, Zhai Y, Xia E, Ludmerer S, Kozlowski J, Coburn C. In vitro resistance analysis of HCV NS5A inhibitor MK-8742 demonstrates increased potency against clinical resistance variants and higher resistance barrier. J Hepatol. 2012;56:S334–S335. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang GWJ, Patel D, Zhao Y, Fabrycki J, Weinheimer S, Marlor C, Rivera J, Wang Q, Gadhachanda V, Hashimoto A, Chen D, Pais G, Wang X, Deshpande M, Stauber K, Huang M, Phadke A. Preclinical characteristics of ACH-3102: a novel HCV NS5A inhibitor with improved potency against genotype-1a virus and variants resistant to 1st generation of NS5A inhibitors. J Hepatol. 2012;56:S330. [Google Scholar]