Abstract

One-site immunometric assays that utilize affinity microcolumns were developed and evaluated for the analysis of protein biomarkers. This approach used labeled antibodies that were monitored through on-line fluorescence or near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence detection. Human serum albumin (HSA) was utilized as a model target protein for this approach. In these assays, a fixed amount of labeled anti-HSA antibodies was mixed with samples or standards containing HSA, followed by the injection of this mixture onto an HSA microcolumn to remove excess antibodies and detect the non-retained labeled antibodies that were bound to HSA from the sample. The affinity microcolumns were 2.1 mm i.d. × 5 mm and contained 8-9 nmol of immobilized HSA. These microcolumns were used from 0.10-1.0 mL/min and gave results within 35 s to 2.8 min of sample injection. Limits of detection down to 0.10-0.28 ng/mL (1.5-4.2 pM) or 25-30 pg/mL (0.38-0.45 pM) were achieved when using fluorescein or a NIR fluorescent dye as the label, with an assay precision of ± 0.1-4.2%. Several parameters were examined during the optimization of these assays, and general guidelines and procedures were developed for the extension of this approach for use with other types of affinity microcolumns and protein biomarkers.

Keywords: One-site immunometric assay, Chromatographic immunoassay, Human serum albumin, Affinity microcolumn, Protein biomarker, Near-infrared fluorescence

1. Introduction

A chromatographic immunoassay is a useful analytical tool that employs antibodies or related ligands as part of a chromatographic system for the determination of one or more components in a sample [1-8]. The selectivity of antibodies makes this technique suitable for the analysis of specific targets in complex matrices such as serum, plasma, blood, or urine [3-8]. Other advantages of chromatographic immunoassays, and especially when they are part of an HPLC system, include their speed, precision, ease of automation, and ability to be used with various detectors or assay formats [1-4,5-8].

There have been several previous methods that have been developed for chromatographic immunoassays based on either liquid chromatography or HPLC. These methods have been used to detect and measure such targets as proteins, peptides, drugs, hormones, bacteria and environmental agents [1-10]. Recent work has also explored the use of affinity microcolumns (i.e., columns with volumes in the low microliter range) in some of these applications and formats [9-17]. Potential advantages in using these microcolumns for chromatographic immunoassays or other applications include the small amount of antibodies or binding agents that are required, the relatively low non-specific binding of these microcolumns, their low back-pressures, their small column residence times, and their ability to be used in microscale systems or in combination with other analytical methods [9-17].

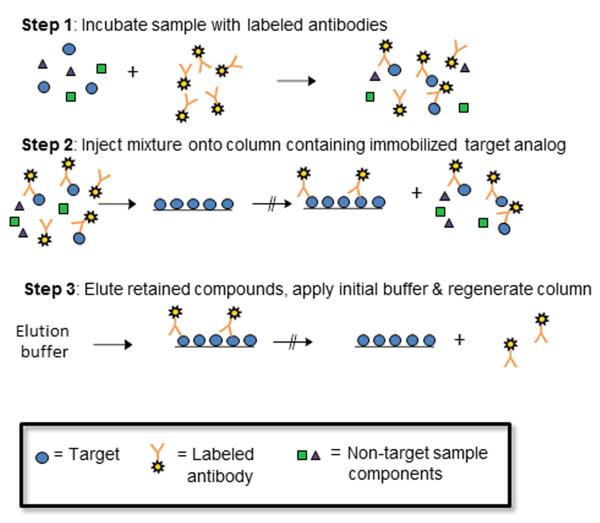

One type of chromatographic immunoassay is a one-site immunometric method (see Figure 1) [6-8,18-20]. In this technique, a sample containing the desired target analyte is combined with an excess of labeled antibodies or antibody fragments that can bind to the target. After this mixture has been allowed to incubate, it is injected onto a column that contains an immobilized analog of the target and is used to bind any remaining excess of the labeled antibodies or binding agents. As the amount of the target is increased in the sample, more of this target will take up sites on the labeled binding agent and more of this labeled agent will elute as a non-retained peak when this mixture is applied to the analog column. Alternatively, the amount of labeled binding agent that is captured by the column can later be released with an elution buffer and used to provide an indirect measurement of the amount of target that was in the sample. After such an elution step, the column may then be regenerated and used for another series of injections of the target and labeled binding agent [7,8,18].

Figure 1.

Typical scheme for a chromatographic-based one-site immunometric assay. This particular figure shows a case in which excess binding agent that is bound to a single target from the sample will not be able to bind to the column; however, it is possible for a bivalent binding agent (e.g., an intact antibody) and a reasonably small target (e.g., a low mass drug or hapten), that some retention of a bivalent binding agent that is bound to only one target may also occur [8,19,20].

A one-site immunometric assay has been used in prior work both alone and as part of postcolumn immunodetection schemes to measure small targets such as digoxin or related compounds, L-thyroxine, and 17β-estradiol, as well as some herbicides and amino acids or amino acid derivatives [18-30]. This method has also been employed with a few intermediate sized targets such as human methionyl granulocyte colony stimulating factor (14.5 kDa) and interleukin-10 (18 kDa) [31,32]. These previous applications have employed affinity columns with lengths of 1 cm to 3 m and typical volumes of 0.1 to 1.57 mL [18-20,22,23,25,29], making it possible to provide a large binding capacity and good capture efficiency for the excess labeled binding agent [7,8]. Only a few reports have used columns less than 100 μL in size for this type of assay [24,27,28,30] and none of these earlier reports have examined the use of one-site immunometric assays for targets with masses larger than 18-20 kDa (i.e., a range of interest for many protein biomarkers).

This current study will examine the extension and use of one-site immunometric assays with affinity microcolumns and for the analysis of protein biomarkers. The columns to be tested will have volumes below 18 μL and a length of only 5 mm. Human serum albumin (HSA) will be used as the model protein in this work, and on-line detection will be carried out by using either fluorescent or near-infrared fluorescent (NIR) labels. Chromatographic theory will be used to help describe the general behavior of a one-site immunometric assay when using affinity microcolumns. Practical factors that will be considered in the development and optimization of such an assay will include the binding capacity and capture efficiency of the affinity microcolumns and the effects of the sample and reagent concentrations, and the type of label on the response and limits of detection of this method. The results should provide useful guidelines that can then be utilized in future work to modify this approach for the analysis of alternative proteins or other biomarkers of interest in biomedical applications.

2. Theory

The general behavior of a one-site immunometric assay has been previously described by using the reactions shown in Eqns. (1) and (2) [7,20,22,27].

| (1) |

| (2) |

The first step in this process is the solution-phase reaction in Eqn. (1) that occurs between the target analyte (A) and a labeled antibody or binding agent (Ab*). The reaction in Eqn. (1) takes place when these components are mixed and incubated prior to injection on the analog column and is described by the association equilibrium constant Ka* when sufficient time has been allowed for the binding to reach completion (note: the rates of the forward and reverse reactions in this process can also be considered when shorter incubation times are used in the assay) [19,20,27]. The second step in this process, which is described by Eqn. (2), occurs when the sample/labeled binding agent mixture is applied to an affinity column that contains an immobilized analog of the analyte (L), which is used to bind and retain any remaining excess of the labeled binding agent. This second reaction is described by the second-order association rate constant ka, in which dissociation of the complex Ab*-L is assumed to be negligible on the time scale that the non-retained peak spends within the column [7].

If the solution-phase reaction in Eqn. (1) is allowed to reach equilibrium and the concentration of Ab* is greater than A, the fraction of analyte that is bound by Ab* (as represented by the term αA-Ab*) can be described by Eqn. (3) for a system with 1:1 binding; a similar, expanded form of this equation can also be developed for a system with multivalent interactions.

| (3) |

(note: Eqn. (3) includes the term Ka*[Ab*] in the numerator, which should have also been present for the expression given for αA-Ab*, and for the relative assay response, in Ref. [7]). It is possible to use an expression like the one in Eqn. (3) to describe the relative response that would be expected for a one-site immunometric assay. For instance, the non-retained fraction of the labeled binding agent, which is directly related to the amount of bound target and αA-Ab*, is often used to generate a calibration curve in such a method [7,20,22,29]. If the affinity column contains an excess of the immobilized analog and has a high capture efficiency for the excess of the labeled binding agent (i.e., the fraction of the non-captured, excess binding agent is small), the relative response based on the non-retained peak would be as follows [7].

| (4) |

The value of Load A is defined in this case as the ratio of the moles of applied analyte versus the moles of binding sites within the affinity column (mL), where Load A = mol A/mL, but this term is also directly proportional to the mass or concentration of the analyte in the injected sample.

According to Eqn. (4), the response and size of the non-retained peak in a one-site immunometric assay will depend on the extent to which A has become bound to the labeled binding agent and the total quantity of A in the sample [7,20,27]. Eqn. (4) predicts that a linear response with a positive slope will be obtained for a plot of the relative response vs. Load A when A and Ab* bind in a 1:1 ratio, and the labeled binding agent is present in an excess when compared to the amount of target in the sample. In addition, the slope of this curve will also be related to the term Ka*[Ab*], with the slope initially increasing as this product increases and then approaching a constant at high values of Ka*[Ab*] [7]. Similar relationships, but with possible non-linear behavior [20], can be developed for the assay response in systems with multivalent interactions between A and Ab*.

An additional term is required in Eqn. (4) or related expressions to describe the intercept for the calibration curve [27]. One way a non-zero intercept can be obtained is if some components in the sample/labeled binding agent mixture provide a signal but cannot bind to the analog column (e.g., an inactive form of the labeled binding agent or an unreacted form of the label) [7,27,29]. In these situations, the size of the background signal will be proportional to the amount of the labeled binding agent that is combined with the sample. A second possible cause of a non-zero intercept is if the analog column has an insufficient binding capacity for retaining the excess labeled binding agent. In this second case, the background will be directly related to the amount of the binding agent that exceeds the column binding capacity. This effect can be minimized by using a larger column or a smaller amount of binding agent [22].

A third possible source of a non-zero intercept is if the column has a sufficient binding capacity but the active, excess labeled binding agent does not have sufficient time to bind to this column [7,28,29,32]. The size of this background signal can be described by using an expression like the one shown in Eqn. (5) for a binding agent and immobilized analog with a 1:1 interaction [7,33,34].

| (5) |

In this expression, F is the non-retained fraction of the labeled binding agent Ab*, and Load Ab* is the relative amount of the excess labeled binding agent versus the amount of immobilized analog in the column (i.e., Load Ab* = mol Ab*/mL) [7,33,34]. The term So in Eqn. (5) represents a combination of factors that include the association rate constant ka for the binding of Ab* with L, the flow rate of injection (F), and the column binding capacity (mL), where So = F/(ka mL). In this situation, the size of the background signal will be affected by the amount of the labeled binding agent, the flow rate, and the column binding capacity, which will each affect the capture efficiency of the column for the labeled binding agent [7].

3. Experimental

3.1. Reagents

Nucleosil Si-300 silica (300 Å pore size, 7 μm particle size) was obtained from Macherey-Nagel (Bethlehem, PA, USA). The HSA (Cohn fraction V, essentially fatty acid free, ≥ 96% pure), sodium cyanoborohydride (94%, a mild reducing agent), sodium borohydride (98%, a strong reducing agent), R-(+)-warfarin (i.e., R-3-(α-acetonylbenzyl)-4-hydroxycoumarin, > 98%), Tween 20 (polyethylene glycol sorbitan monolaurate), and rabbit serum (sterile and filtered) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-fluorescein was from Thermo Scientific (Atlanta, GA, USA). The IRDye 800CW NHS ester was purchased from LI-COR (Lincoln, NE, USA). The polyclonal anti-HSA antibodies (catalog no. 600-401-03, purified from monospecific rabbit anti-serum using HSA as the affinity ligand) were from Rockland Immunochemicals (Gilbertsville, PA, USA). Reagents for the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay were from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). All buffers and aqueous solutions were prepared using water from an EMD MILLI-Q water system and were filtered using 0.2 μm GNWP nylon filters from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA).

3.2. Apparatus

The HPLC system consisted of a Jasco 2000 HPLC system (Easton, MD, USA) that contained a DG-2080–53 three-solvent degasser, two PU-2080 isocratic pumps, an AS-2057 autosampler equipped with a 100 μL sample loop (operated in the partial loop injection mode), a column heater, UV-2075 absorbance detector, and a FP-2020 fluorescence detector. This system also included a custom-built NIR fluorescence detector supplied by LI-COR, as described previously [16,17,35]. A Rheodyne Advantage PF six-port switching valve (Cotati, CA, USA) was used to alternate passage of the analyte and buffer solutions through the columns during the frontal analysis studies. The system components were controlled by a LC-Net II/ADC system and ChromNAV software v1.18.03 from Jasco. Chromatographic data were collected using ChromNAV and processed using PeakFit 4.12 (SeaSolve Software, San Jose, CA, USA). Purification of the labeled anti-HSA antibodies was performed using Zeba spin desalting columns (7 kDa cutoff, 700 μL to 4 mL sample capacity) from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA), along with a 5702RH temperature-controlled centrifuge from Eppendorf (New York, NY, USA) and a fixed-angle centrifuge rotor from VWR (West Chester, PA, USA). The microcolumns were packed using an HPLC slurry packing system from ChromTech (Apple Valley, MN, USA).

3.3. Preparation of affinity microcolumns

The preparation of diol-bonded silica and the procedure for the immobilization of HSA to this support by the Schiff base method were carried out according to previous methods [16,17,36]. A control support was prepared using the same starting materials and procedures but with no HSA being added during the immobilization step. For the immobilization procedure, approximately 500 mg of aldehyde-activated silica, as prepared through periodate oxidation of the diol-bonded silica, was placed into 3 mL of pH 6.0, 0.10 M potassium phosphate buffer and sonicated under vacuum for 15 min. After sonication, a 50 mg portion of HSA and 3 mg of sodium cyanoborohydride were placed into this slurry and this mixture was shaken at 4 °C for 6 days. The support was then washed with pH 8.0, 0.10 M potassium phosphate buffer and 12.5 mg of sodium borohydride was slowly added to remove any remaining aldehyde groups on the support [36].

After immobilization, the support containing the immobilized HSA was washed several times with pH 7.4, 0.067 M potassium phosphate buffer and stored in this buffer at 4 °C until use. The final protein content of the HSA support was determined in triplicate by using a BCA protein assay [37]. The HSA support and control support were placed into separate 2.1 mm i.d. × 5 mm stainless steel microcolumns by downward slurry packing at 4000 psi (28 MPa) using pH 7.4, 0.067 M potassium phosphate buffer as the packing solution. The microcolumns were stored in this same buffer at 4 °C when not in use.

3.4. Production of labeled antibodies

NHS-Fluorescein was used to label some of the anti-HSA antibodies for this study. To do this, a 130 μL portion of a 1 mg/mL commercial preparation of anti-HSA antibodies was exchanged into a pH 8.0, 0.10 M potassium phosphate buffer by using a Zeba spin desalting column. A 1 mg portion of NHS-fluorescein was then dissolved in 100 μL of N,N-dimethylformamide. A 0.05 mg portion of this NHS-fluorescein solution was added per 1 mg of antibody, as accomplished by placing 1 μL of the labeled dye solution (concentration, 10 mg/mL) into an amber vial containing 100 μL of the anti-HSA antibody solution (concentration, ~1.0 mg/mL). This dye-antibody mixture was gently shaken at room temperature for 1 h. This mixture was then placed into a Zeba spin desalting column that had been washed with pH 7.4, 0.067 M potassium phosphate buffer and was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 2 min to collect the labeled antibodies. The concentration of labeled antibodies and dye/antibody content were determined, according to a procedure from the manufacturer of the dye label, by making absorbance measurements at 280 nm and 494 nm (i.e., the latter being the maximum absorbance wavelength for fluorescein). The labeled antibodies were stored at 4°C in pH 7.4, 0.067 M phosphate buffer and in an amber vial until use.

An NHS-activated form of the NIR fluorescent dye IR-800CW was also conjugated to some of the anti-HSA antibodies. A 0.1 mg portion of the IR-800CW NHS ester was placed into 10 μL water, and a 1 μL portion of this 10 mg/mL dye solution was combined with 130 μL of a ~1.0 mg/mL solution of the anti-HSA antibodies in pH 8.0, 0.10 M potassium phosphate buffer. This dye-antibody mixture was gently shaken at room temperature for 2 h. The labeled antibodies were purified from this 130 μL mixture through the use of Zeba spin desalting columns, using a similar procedure to that described for the fluorescein-labeled antibodies. Absorbance measurements were made at 280 nm and 780 nm (i.e., the latter being the maximum absorbance wavelength for IR-800CW) to determine the antibody concentration and dye/antibody ratio in the final purified product. These labeled antibodies were stored at 4°C in pH 7.4, 0.067 M phosphate buffer and in an amber vial until use.

3.5. One-site immunometric assay

The application buffer used for the final, optimized one-site immunometric assays was pH 7.4, 0.067 M potassium phosphate buffer containing 0.01% Tween 20. This buffer was passed through the system at 0.10 mL/min, unless stated otherwise. The elution buffer was pH 2.5, 0.10 M potassium phosphate buffer, which was applied at 0.50 mL/min; these same elution conditions have been shown in the past to give efficient dissociation of HSA from polyclonal anti-HSA antibodies [33,34,38]. The fluorescein-labeled anti-HSA antibodies were detected in the application buffer by using an excitation wavelength of 494 nm and an emission wavelength of 518 nm. The IR-800CW labeled anti-HSA antibodies were detected in the same buffer by using an excitation wavelength of 774 nm and an emission wavelength of 789 nm, as recommended by the manufacturer of the IR-800CW dye. The chromatographic studies were carried out at room temperature, except where otherwise indicated.

The amounts of labeled antibodies that were used in the one-site immunometric assays were varied and optimized for each detection method. In the final assays, these labeled antibodies were mixed in a 1:15 (v/v) ratio with the samples and allowed to incubate for at least 30 min (but less than 2-2.5 h) prior to injection. The stock solutions of fluorescein-labeled antibodies ranged in concentration from 0.74-0.91 mg/mL antibodies, which were then diluted with pH 7.4, 0.067 M phosphate to prepare the final working solutions. The IR-800CW labeled antibodies had stock solution concentrations of 0.75-0.92 mg/mL antibodies, which were also diluted with pH 7.4, 0.067 M phosphate buffer to provide the final working solutions. All working solutions of the labeled antibodies were prepared and stored in amber vials to protect the labels from light. The HSA stock solutions were prepared by weighing 5 mg HSA into a test tube and adding 5 mL of pH 7.4, 0.067 M potassium phosphate buffer. Working solutions of the HSA samples were prepared by making various dilutions of the stock solutions with pH 7.4, 0.067 M phosphate buffer into 1.5 mL vials. Linear regression and statistical analysis of the assay results were carried out using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Seattle, WA, USA).

The zonal elution studies to estimate the HSA content of an analog column were carried out on a 2.1 mm I.D. × 5 mm HSA microcolumn at 0.10 mL/min and 25 °C in the presence of pH 7.4, 0.067 M potassium phosphate buffer. Replicate injections were made of a 20 μL sample containing 20 μM R-warfarin, which is a drug with well-characterized binding to HSA and a common probe used to study the activity of immobilized HSA [39]. Similar injections of a 0.2 mM sodium nitrate were made to determine the void time of the column. The mean positions of the peaks for these injected solutes were used to calculate the retention factor for R-warfarin on the affinity microcolumns [39,40]. During these experiments, the elution of R-warfarin was monitored at 308 nm, and sodium nitrate was monitored at 205 nm.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Design and evaluation of HSA microcolumns

Several factors were considered in the design of the affinity microcolumns that were to be used in the one-site immunometric assay. The support used to prepare these microcolumns was HPLC-grade silica, which had been previously converted into a diol form. This support was selected because of its good mechanical stability, fast mass transfer properties, ease of chemical modification for ligand attachment, and low non-specific binding for antibodies and many biological substances that are found in samples such as serum or plasma [15-17,29,36,41]. Silica with a nominal pore size of 300 Å was chosen to help maximize the amount of HSA (i.e., the immobilized protein analog) that could be immobilized to the support while also allowing good accessibility of the labeled antibodies to this immobilized analog [29,41,42]; for higher mass proteins, a larger pore size could also have been employed [41,43]. Silica with a particle diameter of 7 μm was used to provide good mass transfer rates for the binding of the labeled antibodies to the immobilized HSA [33,34]. In addition, this particle size allowed work to be conducted at reasonably low back pressures, such as might be suitable for a microfluidic device. For instance, the back pressures seen with the microcolumns used in this work were less than 50 psi at flow rates of 0.10 to 1.0 mL/min.

The analyte analog that was attached to this support was HSA. This protein was immobilized through the use of the Schiff base method [36,39], which has previously been used to couple HSA to similar supports for use in chiral separations and drug-protein binding studies [39,44,45]. The total amount of immobilized HSA was estimated by a protein assay to be 71 (± 4) mg/g silica (where the values in parentheses represent ± 1 S.D.). This value corresponded to roughly 550 μg (8.3 nmol) of HSA in a 2.1 mm × 5 mm I.D. column at a packing density of 0.45 g/cm3, the latter value being provided by the manufacturer of the support that was used as the staring material.

The stability and capture efficiency of the HSA microcolumns were examined by injecting a relatively large load of five 0.5 μg injections of fluorescein-labeled anti-HSA antibodies onto a 2.1 mm I.D × 5 mm HSA microcolumn and a control column at 0.10 mL/min. The initial capture efficiency of the labeled antibodies was approximately 76 (± 7)% under these conditions when using either peak amplitudes or peak areas for the measurement. The capture efficiency was determined again after the completion of an elution and regeneration cycle. The elution of the antibodies involved applying pH 2.5, 0.067 M phosphate buffer at 0.50 mL/min for 10 min, followed by regeneration of the column using pH 7.4, 0.067 M phosphate buffer with 0.01% Tween 20 and applied at 0.10 mL/min for 20 min. The measured capture efficiency after elution and regeneration was 76 (± 4)%, which was not significantly different from the initial results obtained for the same HSA microcolumn. These results indicated the HSA microcolumn was sufficiently stable for use with multiple application and elution cycles. In similar studies, the capture efficiency was found to increase as the amount of applied antibodies was decreased, as predicted by Eqn. (5). For instance, the capture efficiency increased to 86-87% when only 6 ng of labeled antibodies were injected (i.e., a load more characteristic of what was used in the final one-site immunometric assays, even after a series of multiple sample injections).

Zonal elution studies were also performed on an HSA microcolumn to estimate its total protein content by using R-warfarin as specific binding probe for HSA [39,44,45]. Replicate injections of R-warfarin were made on a 2.1 mm I.D. × 5 mm HSA microcolumn using pH 7.4, 0.067 M phosphate buffer at 25 °C. The retention factor (k) for R-warfarin under these conditions was determined to be 84 (± 4). This amount corresponded to an active HSA content in the microcolumn of 8.5 (± 0.3) nmol, as determined by using Eqn. (6),

| (6) |

in which Ka was the association equilibrium constant for the binding of R-warfarin with HSA (i.e., 2.6 × 105 M−1 at pH 7.4 and 25 °C) [39], mL was the moles of active of binding sites for R-warfarin in the column, and VM was the column void volume [45]. These results were consistent with the earlier estimate of the HSA content for this same support based on a protein assay. In the one-site immunometric assays that were later used with this type of microcolumn, between 0.12 ng and 2 ng of labeled antibodies were typically used for each injection (i.e., approximately 0.8 to 13 pmol). Thus, roughly a 103- to 104-fold mol excess of immobilized HSA was present versus the labeled antibodies in a single injection, making this binding capacity was more than sufficient for the trace analysis of a protein biomarker like HSA.

4.2. Development of labeled anti-HSA antibodies

The next factor considered in the development of one-site immunometric assays for a protein such as HSA was the type of label that was attached to the antibodies. Fluorescein-NHS is a well-characterized protein-labeling reagent [46] that was employed to evaluate the initial sample/labeled antibody incubation and injection conditions for these assays. A 15 mmol excess of fluorescein-NHS was typically used to label the antibodies, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purification of the labeled antibody conjugate gave a final concentration for the antibodies of 0.74-0.91 mg/mL (or 4.9-6.1 μM), and an average concentration of 0.84 (± 0.06) mg/mL (n = 4 batches). The label content of this preparation ranged from 3-6 mol/mol antibodies, with an average of 5 (± 1) mol/mol. These labeled antibodies were stable for up to two weeks when protected from light and when stored at 4 °C in pH 7.4 buffer.

The second type of labeled antibody conjugate that was considered was one in which the antibodies were labeled with an NHS-ester of the NIR fluorescent tag IR-800CW. This type of label has previously been shown in work with other immunoassay formats to provide good limits of detection (i.e., pM to nM range) and low background signals for biological samples [16,17,35]. The NIR fluorescent labeled antibodies that were prepared in this study had a final antibody concentration of 0.75-0.92 mg/mL (5.0-6.1 μM), and an average concentration of 0.86 (± 0.07) mg/mL (n = 4 batches). These conjugates contained 0.5-1.5 mol label/mol antibody, with an average label content of 1.0 (± 0.3) mol/mol. This type of labeled antibody was again found to be stable for up to two weeks when stored at 4 °C in pH 7.4 buffer and when protected from light.

4.3. Development of one-site immunometric assays using fluorescein as a label

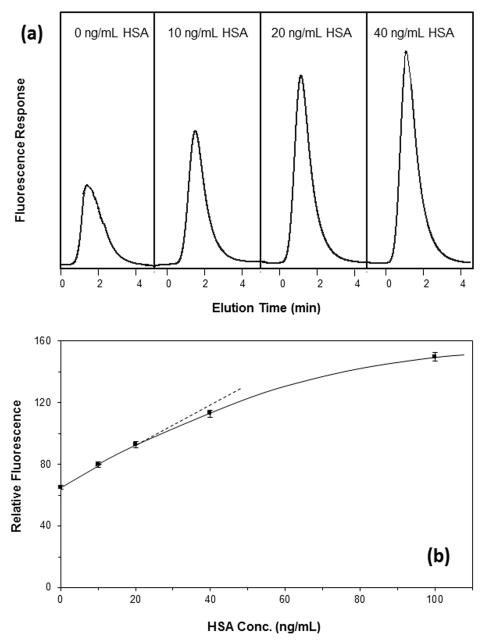

Once the affinity microcolumns and labeled antibodies had been evaluated, these components were combined and tested for use in one-site immunometric assays, using HSA as a model target protein. Some typical chromatograms that were obtained by such a method are shown in Figure 2(a) when using on-line fluorescence detection and fluorescein as the label. As predicted by Eqn. (4), there was an increase in the signal due to the non-retained peak for the labeled antibodies as the amount of HSA was increased in the sample. The use of this non-retained peak for detection allowed results to be obtained within 2.5-2.8 min of sample injection at a flow rate of 0.10 mL/min. When the flow rate was increased to 0.5 mL/min, the non-retained peak was observed within 1.3-1.5 min of sample injection, and this peak appeared at 1.0 mL/min within 35-42 s of injection.

Figure 2.

(a) Representative chromatograms and (b) a typical calibration plot for a one-site immunometric assay, as obtained by using 600 ng/mL fluorescein-labeled anti-HSA antibodies combined with samples that contained 0-100 ng/mL HSA in a 1:15 (v/v) ratio. The final concentration of labeled antibodies before injection was 40 ng/mL. This mixture was injected onto a 5 mm × 2.1 mm I.D. affinity microcolumn containing immobilized HSA. The flow rate for the application step in this example was 0.10 mL/min, the injection volume was 50 μL, and the minimum incubation time for the labeled antibodies with the sample was 30 min. The x-axis in (a) shows the elution time after sample injection, in which the non-retained peak that is observed is due to the complex of the labeled anti-HSA antibodies with soluble HSA in the sample. The dashed line in (b) shows the linear response obtained at low-to-moderate target concentrations, and the error bars represent ± 1 standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 2(b) shows a typical calibration curve that was generated over a relatively broad range of sample concentrations and under the same experimental conditions as used in Figure 2(a). This calibration plot gave an initial linear response, which then approached a plateau as the amount of HSA approached and exceeded the amount of labeled antibodies in the injected sample. The limit of detection in this initial trial was 1.9 ng/mL (or 28 pM) at a signal-to-noise ratio of three (S/N = 3), as based upon the slope and standard deviation of the intercept for the best-fit line. The linear range extended up to approximately 25-40 ng/mL (0.38-0.60 nM) with the given preparation of labeled antibodies, and the dynamic range went up to over 100 ng/mL (1.5 nM). As will be shown later in this section, the limit of detection and usable range of this assay could be adjusted by varying the amount of labeled antibodies that was mixed with each sample.

Based on Eqn. (4), linear behavior at low-to-intermediate target concentrations would be expected for a one-site immunometric assay when a 1:1 interaction can occur between the target and labeled binding agent [7]. This type of behavior has been noted in prior work with labeled Fab fragments [20]. For bivalent binding agents (e.g., intact antibodies or F(ab’)2 fragments), some sigmoidal behavior has been observed in the calibration curves of one-site immunometric assays for small targets [20], although others have found this curvature to be minimal and to approximate a linear response [27]. In this current study, a linear response was consistently obtained when using intact antibodies for the protein HSA. There are several reasons why this may have occurred. For instance, the binding of one HSA with an antibody may have blocked the remaining site on the antibody and prevented, or at least slowed down, the interaction of this second region with immobilized HSA in the microcolumn. It is also possible that the size of the HSA-antibody complex (~140-150 Å) versus the pore size of the support (300 Å, prior to protein immobilization) may have created restricted diffusion or prevented this complex from reaching most of the immobilized HSA [41]. Such effects could have resulted in pseudo-monovalent behavior and a response that was still consistent with that predicted by Eqn. (4). This conclusion was supported by the fact that the linear range in these plots extended up to roughly a sample concentration at which the soluble HSA and labeled antibodies were present at or near a 1:1 mol/mol ratio. Similar behavior has been noted in preliminary work with other protein targets with masses down to 20-25 kDa and under comparable chromatographic conditions.

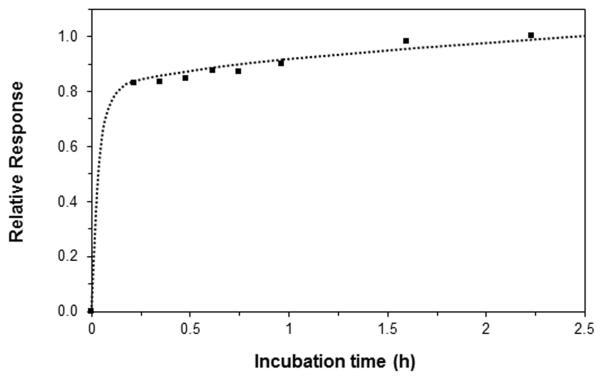

One item of interest in the optimization of the one-site immunometric assays was the total incubation time that was required when samples were mixed with the labeled antibodies. This factor was examined early in this study by preparing a sample that contained 600 ng/mL of fluorescein-labeled anti-HSA antibodies and 10 ng/mL of HSA, which were combined in a 1:15 (v/v) ratio (giving a final labeled antibody concentration of 40 ng/mL) and allowed to incubate at room temperature. A portion of this sample was then injected at 0.10 mL/min onto the HSA microcolumn after various incubation times. The results are given in Figure 3. Most of the change in the size of this non-retained peak occurred between 0 and 13-20 min of incubation (i.e., approximately 83% of the overall change seen over the first 2.25 h) as the HSA in the sample became bound by the labeled antibodies. There was only a small change in the size of this peak between 13-20 min and 30-45 min (i.e., an increase of 1.7-4.3%) or 60 min (an increase of 6.7-6.9%). Even at incubation times up to 5.4 h, a further increase of only 18% was seen versus the results at 2.25 h. Similar results were obtained when utilizing the same amount of antibodies and even larger amounts of HSA (i.e., up to 40 ng/mL). These results agree with previous observations that have been made for one-site immunometric assays involving low-or-intermediate mass targets, for which even shorter incubation times have sometimes been possible [21,27,32]. Based on these results, a minimum incubation time of 30 min and a maximum of 2-2.5 h were used in all later work. However, Figure 3 indicates that incubation times as low as 13-15 min could have been used without a significant loss in the signal.

Figure 3.

Effect of incubation time on the response for a one-site immunometric assay. These results were obtained at 0.10 mL/min on a 2.1 mm I.D. × 5 mm affinity microcolumn containing immobilized HSA. The samples were prepared by combining 600 ng/mL of fluorescein-labeled anti-HSA antibodies and 10 ng/mL HSA in a 1:15 (v/v) ratio. The final concentration of the labeled antibodies in this mixture was 40 ng/mL. These values shown represent the measured heights of the non-retained peak and were normalized versus a value of 1.0 for the result at 2.25 h and 0.0 for a blank sample containing labeled antibodies but no HSA.

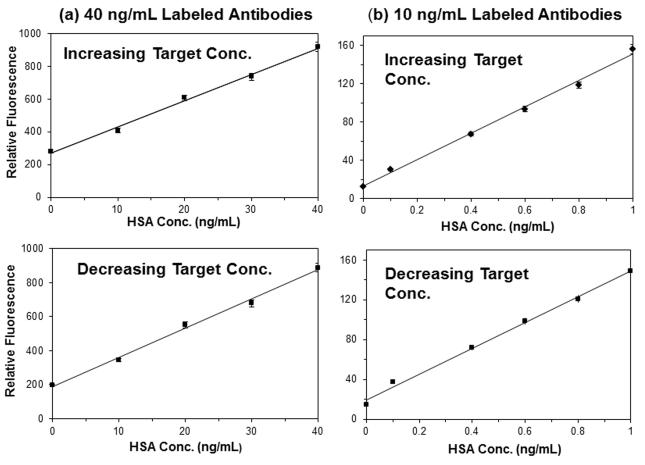

Figure 4 provides some calibration curves that were obtained when using both increasing and decreasing HSA concentrations. These results were obtained on a single HSA microcolumn and using triplicate measurements for each standard, with regeneration and elution steps being done at the end of all injections in a given calibration curve. For the sake of this discussion, these examples focus on the linear portion of these plots and/or the response at low-to-intermediate concentrations. The upper and lower curves in Figure 4(a) were generated sequentially by using a final concentration of labeled antibodies in the sample/antibody mixture of 40 ng/mL and an injection flow rate of 0.10 mL/min. A linear response was seen over the concentration range of 0-40 ng/mL in both of these plots. When using a series of samples with increasing concentrations, the lower limit of detection was 0.7-0.8 ng/mL (11-12 pM) based on both peak amplitudes and areas, and the relative precision was ± 0.4-3.3%. When the assay was repeated using decreasing sample concentrations, the lower limit of detection was 0.9 ng/mL (14 pM), and the precision was ± 0.1-3.1%.

Figure 4.

Calibration plots obtained for a series of standards with increasing HSA concentrations or decreasing HSA concentrations for solutions containing a final concentration of (a) 40 ng/mL or (b) 10 ng/mL of the fluorescein-labeled antibodies. The original concentration of the antibodies was 600 or 150 ng/mL, which was combined in a 1:15 (v/v) ratio with samples and incubated for minimum of 30 min. An application flow rate of 0.10 mL/min and an injection volume of 50 μL were used. These results are for the height of the non-retained peak, and using two different batches of the labeled antibodies for the plots in (a) and (b). The error bars represent ± 1 standard error of the mean (n = 3) and are often on a size scale that is comparable to the data symbols used in these plots.

The same type of experiment was conducted over a lower range of sample concentrations and using a smaller amount of labeled antibodies (i.e., a final concentration of 10 ng/mL). The results are shown in Figure 4(b). In general, the use of a smaller amount of labeled antibodies resulted in a decrease in the background signal and a lower limit of detection, provided that enough labeled antibodies were still utilized to provide a measurable change in the response. These trends agreed with general observations that have been made in the use of one-site immunometric assays with low mass targets [27,28]. The precision for the assay with increasing sample concentrations in Figure 4(b) was ± 0.1-1.5%, and the limit of detection was 0.10-0.16 ng/mL (1.5-2.4 pM). The precision was ± 0.1-3.2% when using decreasing sample concentrations, and the limit of detection was 0.24-0.28 ng/mL (3.6-4.2 pM).

The results in Figure 4 using increasing and decreasing sample concentrations were compared to provide information on the robustness of the microcolumns, as well as possible sample carryover effects in this method. The average difference in Figure 4(a) between the curves using increasing and decreasing sample concentrations was only −3.4% based on peak amplitudes and −8.0% based on peak areas. The average difference in Figure 4(b) for these sets of curves was −6.7% based on peak amplitudes and −9.6% based on peak areas. The small decrease in these results for the curves with increasing and decreasing concentrations indicated that sample carryover was not a significant problem in this method. These results also indicated that the HSA microcolumns could be used over many injections and confirmed that these microcolumns were stable over a number of regeneration and elution cycles.

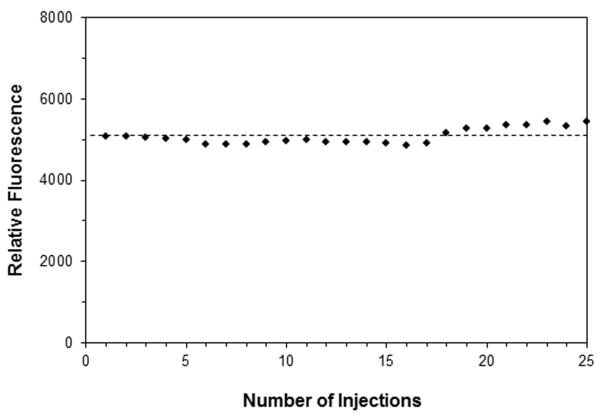

Another set of studies further examined the use of this system over multiple injections of the antibody/sample mixtures, but without the use of an elution and regeneration cycle between injections. Such an approach is of interest for postcolumn immunodetection [18,24,25] and in cases where it is important to maximize sample throughput or to minimize the time per injection [6-8]. This format was tested by making 25 sequential injections of 50 μL samples that contained 7.5 ng/mL HSA and 10 ng/mL fluorescein labeled anti-HSA antibodies. Some typical results are shown in Figure 5. A steady signal was obtained when using either the peak area or amplitude, with a relative variation of only ± 3-4%. These results suggested that repeated injections could be performed on this type of affinity microcolumn, and again indicated that there was no appreciable change in capture efficiency or column stability during a series of such injections. The previous chromatograms in Figure 2(a) indicated that an injection every 4 min (or a sample throughput as high as 15 samples per hour) could be achieved with this method at an application flow rate of 0.10 mL/min. At 1.0 mL/min, it was estimated that a throughput of 50-65 samples per hour could even be obtained by this approach.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of column stability and assay variability over a series of 25 injections of 50 μL samples containing 7.5 ng/mL HSA and 10 ng/mL fluorescein-labeled anti-HSA antibodies. The samples were combined by adding 150 ng/mL of fluorescein-labeled anti-HSA antibodies and 7.5 ng/mL HSA in a 1:15 (v/v) ratio. These injections were onto a 5 mm × 2.1 mm I.D. HSA microcolumn at 0.10 mL/min and after a minimum incubation time of 30 min, with no elution or regeneration steps being used between injections.

4.4. Development of one-site immunometric assays using NIR fluorescence

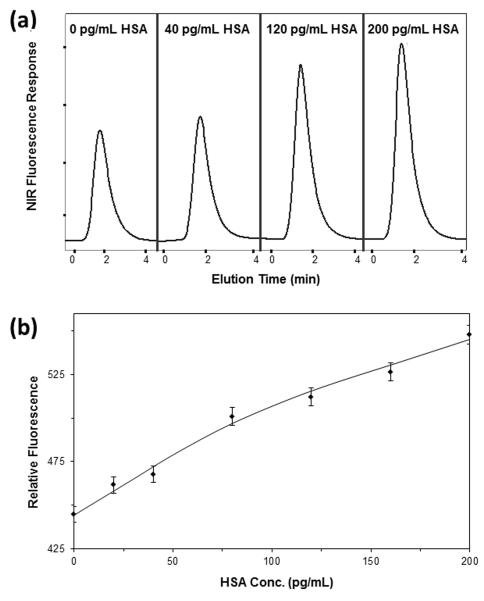

NIR fluorescent labeled anti-HSA antibodies were also tested for use in one-site immunometric assays employing on-line fluorescence detection with the affinity microcolumns. Some typical chromatograms and a calibration curve that were acquired with these labeled antibodies are provided in Figure 6. In the first case that was tested, a 150 ng/mL portion of the labeled antibodies was combined in a 1:15 (v/v) ratio with standards that contained 0-200 pg/mL HSA, giving a final concentration for the labeled antibodies of 10 ng/mL. The limit of detection for this method when using an injection flow rate of 0.1 mL/min was 25 pg/mL (or 0.38 pM), and the relative precision was ± 3.1-3.7%. A second set of conditions used a final concentration for the labeled antibodies of 0.30 ng/mL and an injection flow rate of 0.10 mL/min. Under these new conditions, the lower limit of detection was 30 pg/mL (0.45 pM), and the precision of the assay was ± 3.9-4.2%.

Figure 6.

(a) Representative chromatograms and (b) calibration plot, based on peak amplitude, for a one-site immunometric assay that was obtained by using NIR fluorescent-labeled anti-HSA antibodies. The samples contained 0-200 pg/mL HSA and were mixed in a 15:1 (v/v) ratio with 150 ng/mL of labeled antibodies, giving a final concentration for the labeled antibodies of 10 ng/mL. These mixtures were incubated for a minimum of 30 min and were applied to a 5 mm × 2.1 mm I.D. HSA microcolumn at 0.10 mL/min using a 50 μL injection volume. The x-axis in (a) shows the elution time after sample injection. The error bars in (b) represent ± 1 standard error of the mean (n = 3).

One advantage of using a NIR fluorescent label in the one-site immunometric assay was the relatively low background signal this label has in a matrix such as serum. To test the use of this assay format with such a sample, a spiked recovery study was carried out in which 500 μL of a solution containing 30 ng/mL of the NIR fluorescent-labeled anti-HSA antibodies was combined with 250 μL of rabbit serum that was spiked with 750 μL of 0.0, 0.40 or 2.0 ng/mL HSA. The final concentration of the labeled antibodies in this mixture was 10 ng/mL and the final HSA concentrations were 0.0 ng/mL (buffer), 0.20 ng/mL or 1.0 ng/mL. Prior to its combination with the HSA and labeled antibodies, the rabbit serum was passed through a 0.2 μm filter to remove particulate matter. A calibration plot was also prepared using the same amount of labeled antibodies and aqueous standards that contained 0-1.0 ng/mL HSA. The assay was performed at 0.10 mL/min and gave a calibration plot with a limit of detection 50 pg/mL HSA (0.75 pM) and a relative precision of ± 0.6-2.5%. The recovery for the sample spiked with 0.20 ng/mL HSA was 113 (± 4)% and for the sample spiked with 1.0 ng/mL HSA it was 117 (± 5)%. These results indicated that this type of one-site immunometric assay could give good recoveries and be used to measure trace amounts of a protein biomarker such as HSA in a complex biological matrix like serum.

5. Conclusion

This study evaluated the theory and use of affinity microcolumns in one-site immunometric assays for protein biomarkers, using HSA as a model target. Several parameters were considered in the development and optimization of these methods. These items included the affinity microcolumn, the type and amount of labeled antibodies that were employed, and the chromatographic conditions that were used to combine these components to create a one-site immunometric assay. For instance, it was found that the response and limit of detection could be adjusted by altering the amount and type of labeled antibodies that were used. The final methods gave results within 35 s (at 1.0 mL/min) to 2.8 min (at 0.10 mL/min) of sample injection and limits of detection down to 25-30 pg/mL (0.38-0.45 pM) based on NIR fluorescence detection or 0.10-0.28 ng/mL (1.5-4.2 pM) based on the use of fluorescein as a label.

An important feature of this method is it could easily be applied to the use of other types of proteins or antibodies by changing the types of immobilized analogs and labeled binding agents that are employed. For instance, the same general approach could be developed for the analysis of serum or urinary proteins, enzymes, tumor markers, protein hormones, modified proteins, or protein components of the immune system [47,48]. In addition, the column size and flow rate conditions that were employed are compatible with conditions that are often used in microfluidic devices or microscale separations [9-17]. This latter feature should make this approach attractive for the future development of affinity-based methods for the on-site testing of patients or for the creation of small portable devices for clinical analysis [9,10]. Other advantages of this one-site immunometric method, as demonstrated in this report, are that it is relatively fast and it is possible to alter the assay conditions to adjust its calibration range even when using a single type of affinity microcolumn. The results obtained in this study should provide some general guidelines that can be used to extend this approach to other proteins or to miniaturized devices, giving this method great potential for use in the biomedical research or clinical methods for the analysis of specific proteins as disease-related biomarkers.

Highlights.

Affinity microcolumns were developed for one-site immunometric assays.

These assays were tested for use with protein biomarkers, using HSA as a model.

Several parameters were considered in the optimization of these assays.

Results were obtained in the low pM range and within 35 s-2.8 min of injection.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by the Department of Defense (through a subcontract with SFC Fluidics), the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 GM044931), and by the National Science Foundation/EPSCoR program (grant EPS-1004094). Support for the remodeled facilities that were used to perform these experiments was provided under NIH grant RR015468-001.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Phillips TM. High performance immunoaffinity chromatography. LC Mag. 1985;3:962–972. [Google Scholar]

- [2].de Frutos M, Regnier FE. Tandem chromatographic-immunological analyses. Anal. Chem. 1993;65:17A–25A. doi: 10.1021/ac00049a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hage DS. Survey of recent advances in analytical applications of immunoaffinity chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B. 1998;715:3–28. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hage DS. Immunoassays. Anal. Chem. 1999;71:294R–304R. doi: 10.1021/a1999901+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Weller MG. Immunochromatographic techniques – a critical review. Fres. J. Anal. Chem. 2000;366:635–645. doi: 10.1007/s002160051558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hage DS, Nelson MA. Chromatographic immunoassays. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:198A–205A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Moser AC, Hage DS. Chromatographic immunoassays. In: Hage DS, editor. Handbook of Affinity Chromatography. second ed Taylor & Francis; New York: 2006. pp. 789–836. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Moser AC, Hage DS. Immunoaffinity chromatography: an introduction to applications and recent developments. Bioanalysis. 2010;2:769–790. doi: 10.4155/bio.10.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Phillips TM. Microanalytical methods based on affinity chromatography. In: Hage DS, editor. Handbook of Affinity Chromatography. second edition Taylor & Francis; New York: 2006. pp. 763–787. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Phillips TM, editor. Clinical Applications of Capillary Electrophoresis. Humana, Totowa, NJ: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shen H, Aspinwall CA, Kennedy RT. Dual microcolumn immunoassay applied to determination of insulin secretion from single islets of Langerhans and insulin in serum. J. Chromatogr. B. 1997;689:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Clarke W, Choudhuri AR, Hage DS. Analysis of free drug fractions by ultrafast immunoaffinity chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:2157–2164. doi: 10.1021/ac0009752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Phillips TM. Multi-analyte analysis of biological fluids with a recycling immunoaffinity column array. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 2001;49:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(01)00202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jiang T, Mallik R, Hage DS. Affinity monoliths for ultrafast immunoextraction. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:2362–2372. doi: 10.1021/ac0483668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Clarke W, Schiel JE, Moser A, Hage DS. Analysis of free hormone fractions by an ultrafast immunoextraction/displacement immunoassay: studies using free thyroxine as a model system. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:1859–1866. doi: 10.1021/ac040127x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ohnmacht CM, Schiel JE, Hage DS. Analysis of free drug fractions using near infrared fluorescent labels and an ultrafast immunoextraction/displacement assay. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:7547–7556. doi: 10.1021/ac061215f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schiel JE, Tong Z, Sakulthaew C, Hage DS. Development of a flow-based ultrafast immunoextraction and reverse displacement immunoassay: analysis of free drug fractions. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:9384–9390. doi: 10.1021/ac201973v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Irth H, Oosterkamp AJ, Tjaden UR, van der Greef J. Strategies for on-line coupling of immunoassays to high-performance liquid chromatography. Trends Anal. Chem. 1995;14:355–361. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Freytag JW, Dickinson JC, Tseng SY. A highly sensitive affinity-column-mediated immunometric assay, as exemplified by digoxin. Clin. Chem. 1984;30:417–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Freytag JW, Lau HP, Wadsley JJ. Affinity-column mediated immunoenzymometric assays: influence of affinity- column ligand and valency of antibody-enzyme conjugates. Clin. Chem. 1984;30:1494–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Aref’ev AA, Vlasenko SB, Eremin SA, Osipov AP, Egorov AM. Flow-injection enzyme immunoassay of haptens with enhanced chemiluminescence detection. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1990;237:285–289. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gunaratna PC, Wilson GS. Noncompetitive flow injection immunoassay for a hapten, α-(difuoromethyl)ornithine. Anal. Chem. 1993;85:1152–1157. doi: 10.1021/ac00057a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Locascio-Brown L, Choquette SJ. Measuring estrogens using flow injection immunoanalysis with liposome amplification. Talanta. 1993;40:1899–1904. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(93)80113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Irth H, Oosterkamp AJ, van der Welle W, Tjaden UR, van der Greef J. Online immunochemical detection in liquid chromatography using fluorescein-labeled antibodies. J. Chromatogr. 1993;633:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Oosterkamp AJ, Irth H, Beth M, Unger KK, Tjaden UR, van der Greef J. Bioanalysis of digoxin and its metabolites using direct serum injection combined with liquid chromatography and online immunochemical detection. J. Chromatogr. B. 1994;653:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)e0405-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wilmer M, Trau D, Renneberg R, Spener R. Amperometric immunosensor for the detection of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) in water. Anal. Lett. 1997;30:515–525. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lovgren U, Kronkvist K, Backstrom B, Edholm L-E, Johansson G. Design of non-competitive flow injection enzyme immunoassays for determination of haptens. Application to digoxigenin. J. Immunol. Methods. 1997;208:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lindgren A, Emneus J, Marko-Varga G, Irth H, Oosterkamp A, Eremin S. Optimization of a heterogeneous non-competitive flow immunoassay comparing fluorescein, peroxidase and alkaline phosphatase as labels. J. Immunol. Methods. 1998;211:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Oates MR, Clarke W, Zimlich A, Hage DS. Optimization and development of a high-performance liquid chromatography-based one-site immunometric assay with chemiluminescence detection. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2002;470:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Silvaieh H, Schmid MG, Hofstetter O, Schurig V, Gubitz G. Development of enantioselective chemiluminescence flow- and sequential-injection immunoassays for α-amino acids. J. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;53:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(02)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Miller KJ, Herman AC. Affinity chromatography with immunochemical detection applied to the analysis of human methionyl granulocyte colony stimulating factor in serum. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:3077–3082. doi: 10.1021/ac960201e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kjellstrom S, Emneus J, Marko-Varga G. Flow immunochemical bio-recognition detection for the determination of interleukin-10 in cell samples. J. Immunol. Methods. 2000;246:119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hage DS, Thomas DH, Beck MS. Theory of a sequential addition competitive binding immunoassay based on high-performance immunoaffinity chromatography. Anal. Chem. 1993;65:1622–1630. doi: 10.1021/ac00059a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hage DS, Thomas DH, Chowdhuri AR, Clarke W. Development of a theoretical model for chromatographic-based competitive binding immunoassays with simultaneous injection of sample and label. Anal. Chem. 1999;71:2965–2975. doi: 10.1021/ac990070s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Middendorf L, Amen J, Bruce R, Draney D, DeGraff D, Gewecke J, Grone D, Humphrey P, Little G, Lugade A, Narayanan N, Oommen A, Osterman H, Peterson R, Rada J, Raghavachari R, Roemer S, Daehne S, editors. Near-Infrared Dyes for High Technology Applications. Kluwer Academic; Netherlands: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Larsson PO. High-performance liquid chromatography. Methods Enzymol. 1984;104:212–223. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)04091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujmoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hage DS, Walters RR. Dual-column determination of albumin and immunoglobulin G in serum by high-performance affinity chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1987;386:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)94582-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Loun B, Hage DS. Chiral separation mechanisms in protein-based HPLC columns. 1. Thermodynamic studies of (R)- and (S)-warfarin binding to immobilized human serum albumin. Anal. Chem. 1994;66:3814–3822. doi: 10.1021/ac00093a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hage DS, Anguizola JA, Barnaby O, Jackson AJ, Yoo MJ, Papastavros E, Pfaunmiller EL, Sobansky M, Tong Z, Vargas-Badilla J, Yoo MJ, Zheng X. Characterization of drug interactions with serum proteins by using high-performance affinity chromatography. Curr. Drug Metab. 2011;12:313–328. doi: 10.2174/138920011795202938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gustavsson PE, Larsson PO. Support materials for affinity chromatography. In: Hage DS, editor. Handbook of Affinity Chromatography. second edition Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton: 2006. pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Clarke W, Beckwith JD, Jackson A, Reynolds B, Karle EM, Hage DS. Antibody immobilization to high-performance liquid chromatography supports. Characterization of maximum loading capacity for intact immunoglobulin G and Fab fragments. J. Chromatogr. A. 2000;888:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jackson AJ, Karle EM, Hage DS. Preparation of high-capacity supports containing protein G immobilized to porous silica. Anal. Biochem. 2010;406:235–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Loun B, Hage DS. Characterization of thyroxine-albumin binding using high-performance affinity chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1992;579:225–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hage DS. Chromatographic and electrophoretic studies of protein binding to chiral solutes. J. Chromatogr. A. 2001;906:459–481. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00957-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Khanna PL, Ullman EF. 4′,5′-Dimethoxy-6-carboxyfluorescein: a novel dipole-dipole coupled fluorescence energy transfer acceptor useful for fluorescence immunoassays. Anal. Biochem. 1980;108:156–161. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90706-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Clarke W, Dufour DR, editors. Contemporary Practice in Clinical Chemistry. second edition AACC Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hage DS. Affinity chromatography: a review of clinical applications. Clin. Chem. 1999;45:593–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]