Abstract

Prior studies in other specialties have shown that social networking and Internet usage has become an increasingly important means of patient communication and referral. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the prevalence of Internet or social media usage in new patients referred to a major academic orthopedics center and to identify new avenues to optimize patient recruitment and communication. New patients were surveyed (n=752) between December 2012 to January 2013 in a major academic orthopaedic center to complete a 15-item questionnaire including social media and Internet usage information. Data was collected for all orthopaedic sub-specialties and statistical analysis was performed. Fifty percent of patients use social networking sites, such as Facebook. Sports medicine patients tend to be higher social networking users (35.9%) relative to other services (9.8-17.9%) and was statistically higher when compared to the joints/tumor service (P<0.0001). Younger age was the biggest indicator predicting the use of social media. Patients that travelled between 120 to 180 miles from the hospital for their visits were significantly more likely to be social media users, as were patients that did research on their condition prior to their new patient appointment. We conclude that orthopedic patients who use social media/Internet are more likely to be younger, researched their condition prior to their appointment and undergo a longer average day’s travel (120-180 miles) to see a physician. In an increasingly competitive market, surgeons with younger patient populations will need to utilize social networking and the Internet to capture new patient referrals.

Key words: Internet, social media, orthopaedic surgery, sports medicine

Introduction

Social media and social networking on the Internet has revolutionized healthcare over the past ten years. There are over one billion Facebook users and 500 million members of Twitter worldwide.1 In the United States, 244 million people or about 80% of the population use the Internet for either work or social networking with approximately 158 million users of Facebook.2,3 Of this particular group, the average age is 37 years old and 61% are over the age of 35.4 A recent publication on social networking showed an increase of 43% in user membership from 2009 to 2010 and an average user spends 6.5 hours per week on social media site per week.5 In addition to social media, many innovative tools based on the Internet are used in hospitals, medical schools, and private clinics. These include patient education modules, online medical courses, electronic medical records, monitoring of patients status in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU),6-8 and other online resources to assist in the education of medical students and physicians.1 Historically, patients learned about physicians through primary care referrals and word of mouth; however, paths to physician identification today are much more widespread since the advent of the internet and the spike in social media outlets.5,9 Furthermore, communications between patients and physician have also shifted from the traditional telephone calls to emails, blogs, and internet-based methods.

While patients are known to research their own medical maladies, they also research their own physicians. The advent of websites like rateMD.com, healthgrades.com and vitals.com make physician searches and reviews easy. A negative patient review may be detrimental to a physician’s reputation and their overall ability to recruit new patients to the practice. Other medical specialties have investigated the impact of social media on patient recruitment, education and communication.1,8-18 Previous studies in orthopaedic surgery have looked at the use of Internet in patient education and communication, but no study has investigated the Internet and social media’s role on physician selection by patients and stratified by orthopaedic specialty.

Since many areas in the United States are becoming highly saturated markets for orthopaedic surgeons and the competition for new patients are intense, we investigated specific reasons why patients arrive at a single academic center and how internet or social media usage may play a role in the process. We believe that in certain specialties, primary care referral is no longer the main reason why individuals arrive in clinic. This study intends to analyze the means by which new patients select their orthopaedic surgeon and the prevalence of social media/internet usage among orthopaedic patients. Through capitalizing upon popular avenues of physician selection, patients will have access to a greater array of physician options and accessible contact information. Our main objective is to determine the prevalence of social media and Internet usage in orthopaedic patients presenting for an initial visit. We hypothesized that social media and Internet usage will differ between the different orthopaedic specialties and patient ages. Furthermore, Internet and social media may influence a patient’s decision in their selection of orthopaedic surgeons.

Materials and Methods

All new patients seeing an orthopaedic surgeon at a single major tertiary referral academic institution were prospectively recruited from three clinic locations that are affiliated with the same major academic institution. Clinic settings included a hospital in a city setting, one ambulatory care center in a town setting and one outpatient facility in a suburban city location. Orthopedic surgeon specialties included: foot and ankle, hand, joints, oncology, shoulder and elbow, spine, sports medicine and trauma. Patients were not recruited if they were under the age of 18 or non-English speaking All new patients were given the option to complete the 15-item voluntary questionnaire and no personal health information was recorded (Appedix). No randomization took place. Patients were recruited for a period of two months (December 2012 to January 2013).

Overall summary statistics were calculated in terms of means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical. Group differences among continuous variables were evaluated using independent samples t-tests. Group differences for discrete variables were evaluated using chi-square or Fisher’s Exact Test. Unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated to assess the magnitude of the association.

A multivariable binary logistic regression model was then created to evaluate the adjusted associations of each potential explanatory variable and the likelihood of patients using social networking websites. Variables with a univariate significance level of 0.25 or less or those variables that were deemed to be relevant were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Using a forward stepwise procedure, variables that failed to achieve a P value of 0.15 or below were removed from the final model. Because of the explanatory nature of the analyses, 0.15 was chosen as the threshold for retention in the final model; however, statistical significance was still set at P=0.05. For all regression models, adjusted odds (aOR) and their subsequent 95% confidence intervals were reported. All analyses were done using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

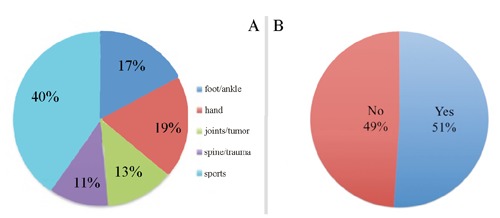

Of the 752 responses, there were 66% female and 34% male responses (Table 1). Responses were obtained from hand (142), sports medicine (303), foot and ankle (129), joints/tumor (95) and trauma (83) services (Figure 1A). Overall, 51% of all patients surveyed report using social networking sites such as Facebook or Twitter (Figure 1B). Of the patients that report not using social network sites, 92% are over the age of 40. Joints/tumor patients most commonly had seen another orthopaedic surgeon prior to their visit (59%) and had prior surgery (42%). Most patients traveled under 60 miles and were referred by their primary care physicians. Between 18-26% of all patients used a physician review website before consultation. However, only 2% of all surveyed patients have actually posted a review onto a Physician Review website. Majority of the patients prefer communicating with their physician via the phone (68%) compared to email (32%). Independent associations found that sports medicine patients tend to be higher social networking users (35.9%) relative to other services (9.8-17.9%) and was statistically higher when compared to the joints/tumor service (P<0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics information of the patient population surveyed in our study (total number of responses 752).

| Information | N. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Under 18 | 12 (1.6) |

| 19-29 | 105 (14.0) |

| 30-39 | 70 (9.3) |

| 40-49 | 149 (19.8) |

| 50-59 | 190 (25.3) |

| 60-69 | 140 (18.6) |

| 70+ | 86 (11.4) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 271 (34) |

| Female | 481 (66) |

| Level of education | |

| Elementary school or junior high | 14 (1.9) |

| High school | 207 (27.5) |

| College graduate | 283 (37.6) |

| Professional/graduate school | 206 (27.4) |

| MD, DO, DDS, DMD, PhD | 42 (5.6) |

| Distance traveled to new patient appointment | |

| Less than 30 miles | 502 (66.8) |

| 30-60 miles | 147 (19.5) |

| 60-120 miles | 76 (10.1) |

| 120-180 miles | 13 (1.7) |

| 180-240 miles | 4 (0.53) |

| Greater than 240 miles | 9 (1.2) |

| Orthopedic surgery service | |

| Foot and ankle | 129 (17.2) |

| Hand | 142 (18.9) |

| Joints/tumor | 95 (12.6) |

| Sports medicine | 303 (40.3) |

| Trauma | 83 (11.0) |

Figure 1.

A) Percentage of services surveyed within the orthopaedic department. B) Overall social media use in the entire patient population surveyed.

Table 2.

Independent associations for patients that utilize social networking sites compared to those that do not (Do you use social networking websites such as Facebook or Twitter?).

| No | Yes | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (%) | N. | Mean(%) | ||

| Service | |||||

| Foot/ankle | 52 | 14.1 | 77 | 20.1 | 0.535 |

| Hand | 72 | 9.8 | 70 | 18.2 | 0.161 |

| Joints/tumor | 66 | 17.9 | 29 | 7.6 | 0.000 |

| Spine/trauma | 46 | 12.5 | 37 | 9.6 | 0.057 |

| Sports | 132 | 35.9 | 171 | 44.5 | Reference |

| Age | |||||

| <18 | 2 | 0.5 | 10 | 2.6 | 0.000 |

| 18-29 | 9 | 2.4 | 96 | 25.0 | 0.000 |

| 30-39 | 15 | 4.1 | 55 | 14.3 | 0.000 |

| 40-49 | 65 | 17.7 | 84 | 21.9 | 0.000 |

| 50-59 | 106 | 0.0 | 84 | 21.9 | 0.000 |

| 60-69 | 101 | 27.4 | 39 | 10.2 | 0.118 |

| >70 | 70 | 19.0 | 16 | 4.2 | Reference |

| Female sex | 228 | 62.0 | 253 | 65.9 | 0.262 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than High school | 9 | 2.4 | 5 | 1.3 | 1.000 |

| High school | 103 | 14.1 | 104 | 27.1 | 0.047 |

| College graduate | 131 | 35.6 | 152 | 39.6 | 0.014 |

| Professional/graduate school | 97 | 26.4 | 109 | 28.4 | 0.022 |

| MD, DO, DDS, DMD, PhD | 28 | 7.6 | 14 | 3.6 | Reference |

| Distance traveled | |||||

| Greater than 240 miles | 3 | 0.8 | 6 | 1.6 | 0.693 |

| 180-240 miles | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 1.000 |

| 120-180 miles | 3 | 0.8 | 10 | 2.6 | 0.175 |

| 60-120 miles | 47 | 12.8 | 29 | 7.6 | 0.010 |

| 30-60 miles | 82 | 22.3 | 65 | 16.9 | 0.034 |

| Less than 30 miles | 230 | 62.7 | 272 | 70.8 | Reference |

| Did prior research | 121 | 32.9 | 199 | 51.8 | <0.001 |

| Total | 368 | 48.9 | 384 | 51.1 | - |

The multivariate logistic regression model showed that the sports service was generally more likely to have social networking users with the exception of the foot/ankle service, however these differences were not statistically significant. The biggest indicator predicting social media usage in the orthopaedic population was age. The older the patient population, the less likely patients will use social networking sites (Table 3). Non-doctorate patients were more likely to be social media users compared to doctorate level individuals, but was not statistically significant. Patients that lived from 120 to 180 miles from the hospital were significantly more likely to be social media users, as were patients that did research on their condition prior to their new patient appointment.

Table 3.

Regression model based on patients that use social networking sites (Do you use social networking websites such as Facebook or Twitter?).

| Adjusted OR | Lower Upper 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.08 | 0.000 | ||

| Service | ||||

| Foot/ankle | 1.29 | |||

| Hand | 0.98 | 0.79 | 2.10 | 0.306 |

| Joints/tumor | 0.77 | 0.61 | 1.60 | 0.950 |

| Spine/trauma | 0.87 | 0.43 | 1.36 | 0.362 |

| Sports | Reference | 0.48 | 1.57 | 0.635 |

| Age | ||||

| <18 | 33.15 | 6.08 | 180.66 | 0.000 |

| 18-29 | 46.86 | 18.70 | 117.40 | 0.000 |

| 30-39 | 14.87 | 6.47 | 34.19 | 0.000 |

| 40-49 | 4.78 | 2.42 | 9.42 | 0.000 |

| 50-59 | 2.76 | 1.43 | 5.31 | 0.000 |

| 60-69 | 1.51 | 0.76 | 3.01 | 0.002 |

| >70 | Reference | - | - | 0.237 |

| Female sex | 1.88 | 1.29 | 2.73 | 0.001 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than High school | 1.85 | 0.39 | 8.78 | 0.438 |

| High school | 1.72 | 0.75 | 3.95 | 0.199 |

| College graduate | 1.84 | 0.83 | 4.05 | 0.131 |

| Professional/graduate school | 2.14 | 0.96 | 4.79 | 0.064 |

| MD, DO, DDS, DMD, PhD | Reference | - | - | - |

| Distance traveled | ||||

| Greater than 240 miles | 1.03 | 0.18 | 5.94 | 0.98 |

| 180-240 miles | 0.46 | 0.05 | 4.43 | 0.50 |

| 120-180 miles | 4.08 | 0.96 | 17.29 | 0.06 |

| 60-120 miles | 0.57 | 0.32 | 1.04 | 0.07 |

| 30-60 miles | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.96 | 0.03 |

| Less than 30 miles | Reference | - | - | - |

| Did prior research | 2.18 | 1.52 3.13 | 0.000 | |

Discussion

Overall, orthopaedic patients who use social media are more likely to be younger, researched their condition prior to their appointment and undergo an average day’s travel (120-180 miles) to see the orthopaedic physician. Our age findings support those of prior studies, which conclude that Internet and social networking users tend to be younger patients.19,20 Understanding patient population demographics is crucial for marketing optimization in the social networking and Internet realm. In particular, our study found that sports medicine patients tend to be the most computer savvy, which may in part be due to younger patient age. Physicians with younger patient populations should take advantage of the numerous social media avenues to increase practice accessibility. Common methods of increasing Internet presence includes, the creation of a personal website, Facebook page, Twitter account, blogs and YouTube videos. In contrast, we found that joints patients, who had a higher average age, were significantly less involved with social networking sites. Arthroplasty surgeons in particular should continue to rely on word of mouth, primary care physician and insurance referrals to build a rigorous practice.

Increased access to medical education resources online is known to alter patient care due to the prevalence of unregulated medical information that is often inaccurate.21,22 Approximately 80% of patients will utilize the internet to obtain health information within their lifetime.5 Furthermore, Danquah et al. found that 85% of surgeons have experienced a patient bringing information to an appointment from the internet.14 In our study, patients that researched their condition prior to their appointment were also social media users. Surgeons should consider including a patient information and education section on a personal website or social networking page as a way to provide accurate, concise and easy to understand information about services offered by the physician and orthopaedic practice. Referencing a website with controlled information is one simple way to increase patient education and reduce time spent re-educating patients about a particular diagnosis or postoperative course on subsequent office visits.

Since patients are already known to research their condition prior to their appointment, there is also a growing trend for patients to research their surgeon prior to their appointment. The newest trend is in the use of physician rating websites (PRW) on the Internet. The primary objective of these sites is to allow patients an opportunity to discuss the physician’s quality of care and overall satisfaction using user-generated data. The advantage with these online rating systems is the ease of usage, availability, and the information maybe easier to understand for patients as this information is generated peer to peer. Up to 26% of our patients utilized a PRW prior to selecting their orthopaedic surgeon for a new patient appointment. However, less than 2% of the patients surveyed actually personally posted a review onto these Physician Review sites. In an analysis of online evaluation of physician rating websites in Germany, 107,148 patients performed 127,192 ratings of 53,585 physicians. Thirty-seven percent of all physicians were rated on the website by a patient population majority of females (60%). Female physicians had a significantly better rating than their male colleagues and older patients tend to give better ratings than younger patients. Furthermore, patients that had private insurance had much better ratings of physicians than the statutory health insurance.23 The authors concluded that due to the differences regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of both the patient and physician, it remains unclear if the ratings on the Internet from these PRW realistically reflect the quality of care delivered by the physician. Thus, with the highly unregulated nature of patient posts on various physician review websites, physicians must be cognizant of Internet content posted that is related to their name on a Google search. Creating a personal website with patient testimonials is a good example of a way to increase regulation of your personal reviews from patients on the Internet. Physicians can also recommend that patients post comments on physician review websites about their good experience with their appointment, surgery and office staff.

Patients who traveled 120-180 miles, which would be considered an average day’s travel to see their physician, were also social media users. In the major US cities, such as Boston, New York City or Los Angeles, that are highly saturated with many reputable hospitals, generating a patient population that extends beyond the immediate vicinity can be a crucial asset to a physician’s practice. Targeting a national and international patient population is made easy through the use of social media (Facebook, Twitter or YouTube) and other Internet tools (personal website). Physician marketing that focuses on specializing in a few primary surgeries will target specific patient populations, which may encourage patients to travel longer distances for an expert opinion.

Despite technological advances that enable patients’ access to endless information at their fingertips, most still prefer to communicate with the physician over the phone, instead of e-mail. This finding should remind us that patients most prefer a personalized approach to medicine, where a direct verbal communication between patient and physician exists. This type of personalized medicine cannot be achieved solely through the use of e-mail communication and value still remains in communication with patients directly. In a national survey evaluating the use of Internet to communicate with health care providers, there was an increase from 7% of internet users to 10% between 2003 to 2005, respectively. Users that used internet to communicate with their health care providers had higher education, lived in a metro area, and reported poorer health status.24 Despite the large percentage of Internet users in the United States, most patients still communicate with their physicians through other means than the Internet. Furthermore, Hesse et al.25 reported that 62.4% of all patients in a national survey trusted their physicians for health information. However, only 10.9% of patients actually went to a physician to get health-related information while 48.6% went to the Internet first to research their conditions before seeing a physician. This further emphasizes the importance of posting accurate medical information onto the Internet that is supported with scientific evidence for patient education. The disadvantage of Internet or email communication is the risk of misinterpretations. All conversations should be documented in the patient’s electronic medical records. Furthermore, it is essential not to share identifiable patient information over the internet or social media which will violate HIPPA policies.

There are several limitations to our study. First, this study surveyed patients only in a major tertiary referral academic medical center in a large urban city setting. If the location of the hospitals were to change to a rural setting or community medical center, our results may have been different. Second, different social medial outlets were grouped together (Facebook, Twitter, Linkedin, etc.) as an indicator of social media usage. However, each of these sites has different purposes and is utilized differently by patients. We did not specifically ask each patient how each site influenced their overall decision in their visit to the orthopaedic surgeon. Instead, our study provides a general idea of how many patients seen in a major orthopaedic center use social media as part of their daily routine.

Conclusions

Over 50% of all orthopaedic patients use social media or Internet for work or personal communication and up to 26% of all patients have seen or used a physician review site prior to their initial visit. Orthopedic patients who use social media/Internet are more likely to be younger, researched their condition prior to their appointment and undergo a longer average day’s travel (120-180 miles) to see a physician. Despite the increased social media usage, most orthopaedic patients still prefer telephone communication with their physicians. Overall, given the high prevalence of social media and Internet usage in young patients, orthopaedic surgeons with younger patient populations (Sports Medicine) may need to utilize social networking and the Internet to capture new patient referrals.

Acknowledgements

The authors would thank Kate Buesser, BA for her assistance with survey collection and data entry. We also thank Jon Beauchesne, Donald Cornuet, Michelle Kennedy, Filicha Kelton, and Jeffrey Taylor for their assistance with survey implementation in the orthopaedic clinic locations. We finally wish to acknowledge the entire team of orthopaedic surgeons at this institution for their patience and willingness to allow us to capture their patient population during the duration of this study.

References

- 1.DeCamp M, Koenig TW, Chisolm MS.Social media and physicians’ online identity crisis. JAMA 2013;310:581-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World development indicators. 2011. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER?order=wbapi_data_value_2011+wbapi_data_value+wbapi_data_value-last&sort=desc Accessed: October 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.CBS News. Facebook user’s down 4.8% in 6 Months. 2012. Available from: http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-505124_162-57459625/facebook-u.s-unique-users-down-4.8-in-6-months/ Accessed: October 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckler P, Worsowicz G, Rayburn JW.Social media and health care: an overview. PM R 2010;2:1046-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saleh J, Robinson BS, Kugler NW, et al. Effect of social media in health care and orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics 2012;35:294-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mannion A.The electronic ICU. Am J Nurs 2009;109:22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colpaert K, Hoste E, Van Hoecke S, et al. Implementation of a real-time electronic alert based on the RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury in ICU patients. Acta Clin Belg Suppl 2007;2:322-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piazza T, Piazza O, De Robertis E, Tufano R.Do you think my ICU will benefit from an electronic medical record system? Panminerva Med 2008;50:339-45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azu MC, Lilley EJ, Kolli AH.Social media, surgeons, and the Internet: an era or an error? Am Surg 2012;78:555-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anikeeva O, Bywood P.Social media in primary health care: opportunities to enhance education, communication and collaboration among professionals in rural and remote locations: did you know? Practical practice pointers. Aust J Rural Health 2013;21:132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antheunis ML, Tates K, Nieboer TE.Patients’ and health professionals’ use of social media in health care: motives, barriers and expectations. Patient Educ Couns 2013;92:426-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barry F.Social media 101 for health care development organizations. AHP J. 2010:30-4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cameron AM, Massie AB, Alexander CE, et al. Social media and organ donor registration: the Facebook effect. Am J Transplant 2013;13:2059-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danquah G, Mittal V, Solh M, Kolachalam RB.Effect of Internet use on patient’s surgical outcomes. Int Surg 2007;92:339-43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon CR.Social networking among upper extremity patients. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36:367-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Randolph SA.Using social media and networking in health care. Workplace Health Saf 2012;60:44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turnipseed WD.The social media: its impact on a vascular surgery practice. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2013;47:169-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Indes JE, Gates L, Mitchell EL, Muhs BE.Social media in vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg 2013;57:1159-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozental TD, George TM, Chacko AT.Social networking among upper extremity patients. J Hand Surg Am 2010;35:819-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou WY, Hunt YM, Beckjord EB, et al. Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res 2009;27:e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Ambrosia RD.Treating the Internet-informed patient. Orthopedics 2009;32:13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernstein J, Ahn J, Veillette C.The future of orthopaedic information management. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:e95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emmert M, Meier F.An analysis of online evaluations on a physician rating website: evidence from a German public reporting instrument. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beckjord RB, Finney Rutten LJ, Squiers L, et al. Use of the internet to communicate with health care providers in the United States: estimates from the 2003 and 2005 Health Information National Trends Surveys (HINTS). J Med Internet Res 2007;9:e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:2618-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]