Abstract

Study Objectives:

To examine relationships among gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms, dietary behaviors, and sleep duration in the general population.

Design:

Cross-sectional.

Setting:

Community-based.

Participants:

There were 9,643 participants selected from the general population (54 ± 13 y).

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Results:

Sleep duration, sleep habits, and unfavorable dietary behaviors of each participant were assessed with a structured questionnaire. Participants were categorized into five groups according to their sleep duration: less than 5 h, 5 to less than 6 h, 6 to less than 7 h, 7 to less than 8 h, and 8 or more h per day. GERD was evaluated using the Frequency Scale for the Symptoms of GERD (FSSG) and participants having an FSSG score of 8 or more or those under treatment of GERD were defined as having GERD. Trend analysis showed that both the FSSG score and the number of unfavorable dietary habits increased with decreasing sleep duration. Further, multiple logistic regression analysis showed that both the presence of GERD (odds ratio = 1.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.07–1.32) and the number of unfavorable dietary behaviors (odds ratio = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.13–1.26) were independent and potent factors to identify participants with short sleep duration even after controlling for other confounding factors.

Conclusion:

The current study showed that both GERD symptoms and unfavorable dietary behaviors were significant correlates of short sleep duration independently of each other in a large sample from the general population.

Citation:

Murase K, Tabara Y, Takahashi Y, Muro S, Yamada R, Setoh K, Kawaguchi T, Kadotani H, Kosugi S, Sekine A, Nakayama T, Mishima M, Chiba T, Chin K, Matsuda F. Gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms and dietary behaviors are significant correlates of short sleep duration in the general population: the Nagahama Study. SLEEP 2014;37(11):1809-1815.

Keywords: dietary behavior, gastroesophageal reflux disease, general population, sleep duration

INTRODUCTION

Amid mounting interest over the effect of sleep on health concerns, many previous studies have suggested that short sleep duration causes a number of conditions such as obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases from results of large general populations.1–6 However, relatively little interest has been paid to determining what factors predict or influence an individual's sleep duration.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic condition that develops when reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus causes troublesome symptoms or complications.7 Acid regurgitation and heartburn are the major complaints of GERD and approximately 10% to 25% of the general population was reported to complain of these symptoms.8–10 Patients with symptoms of GERD commonly report poor sleep, and previous epidemiologic studies have established a link between nighttime heartburn and sleep disturbances.11–13 However, these studies did not focus on sleep duration but rather on subjective sleep quality. The relationship between sleep duration and GERD symptoms has been investigated in very few studies and their results were discrepant. Matsuki et al. examined lifestyle factors associated with GERD in participants who underwent gastroscopy and showed that the subjects with GERD symptoms were more likely to report short sleep duration than those without such symptoms.14 However, Chen et al. performed a similar study and showed that symptoms of GERD were not associated with sleep duration.15 Furthermore, the 800 and 3,000 subjects, respectively, of those studies were recruited during routine health examinations in the hospital and it is possible that these studies did not reflect situations in the general population. A general population survey with a larger sample size is warranted.

In addition, some unfavorable dietary behaviors such as late eating time and snacking after dinner may affect both GERD and sleep duration. However, very few studies investigated the correlation between dietary behaviors and GERD with sleep duration, and the relationships among these three factors have never been evaluated comprehensively in a cohort study.16–18

Given this background, we analyzed the cross-sectional interrelationships among sleep duration, GERD symptoms, and dietary behaviors simultaneously in a large-scale sample of the general population.

METHODS

Study Participants

Included in the current analysis were participants of the Nagahama Prospective Genome Cohort for Comprehensive Human Bioscience (The Nagahama Study). The Nagahama Study is a longitudinal genetic epidemiological study aimed at clarifying unidentified factors and pathways relating genetic variants and disease phenotypes of common diseases and disorders, such as cardiovascular, endocrine, metabolic, and immunological diseases via the comprehensive analysis of omics data. The Nagahama Study cohort was recruited from the general population living in Nagahama City, a largely rural city of 125,000 inhabitants in Shiga Prefecture, located in the center of Japan. Among the total of 9,804 study participants recruited from 2008 to 2010, persons who had a history of malignant diseases of the upper alimentary tract (n = 79), who were pregnant (n = 43) or who did not complete the questionnaires (n = 39) were excluded from the analysis. All study procedures were approved by the ethics committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine.

Basic Clinical Parameters

Basic clinical parameters, including age, body mass index (BMI), and clinical history were obtained from the personal health records collected at the baseline examination for the Nagahama Study. Smoking history and drinking habits were obtained using a structured questionnaire. An individual who consumed alcohol more than 4 days/w was defined as a frequent drinker.

Assessment of Sleep Habits

Hours of sleeping were assessed by the following question: “On average, how many hours do you sleep per day?” Subjects were categorized into five groups according to sleep duration: less than 5 h, 5 to less than 6 h, 6 to less than 7 h, 7 to less than 8 h, and 8 or more h per day. Short sleep duration was defined as less than 6 h of sleep per day according to previous studies.19,20 The regularity of the sleep schedule was also investigated by the following “yes-no” question: “Are your waking time and bedtime regular?”

Assessment of GERD Symptoms

The GERD symptoms were evaluated using the Frequency Scale for the Symptoms of GERD (FSSG),21 a well-validated and widely used questionnaire for the diagnosis of GERD and also for evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment of GERD.22,23 The 12 questions of the FSSG cover various symptoms related to the upper alimentary tract. A higher score indicates more severe GERD symptoms and 8 points are frequently used as a cutoff point for the diagnosis of GERD. All the participants were asked to respond to the FSSG scale questionnaire and participants with an FSSG score of 8 or higher or who were undergoing treatment of GERD were defined as having GERD.

Assessment of Dietary Behaviors

Unfavorable dietary behaviors that were expected to be closely correlated with both sleep duration and GERD symptoms were assessed by the following four “yes-no” questions that are used in the standard health checkup program performed by the Japanese government: 1. Do you have dinner within 2 h before going to bed more than 3 days a week? 2. Do you snack after dinner more than 3 days a week? 3 Do you have a habit of eating rapidly? 4. Do you skip breakfast more than 3 days a week? A score of one was assigned to each “yes” response.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in numeric variables among subgroups were determined by an analysis of variance for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. Trend testing was performed by the Cochrane-Armitage trend test (categorical variables) or the Jonckheere trend test (numeric variables). In comparison of FSSG score among groups categorized by sleep duration and regularity of the sleep schedule, Dunnet test was performed using the group with 7 to less than 8 h/day sleep duration as the reference. We performed multivariate logistic regression analysis to specify the factors independently associated with short sleep duration. Two-tailed P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 7.0.2 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R software (http://www.r-project.org/).

RESULTS

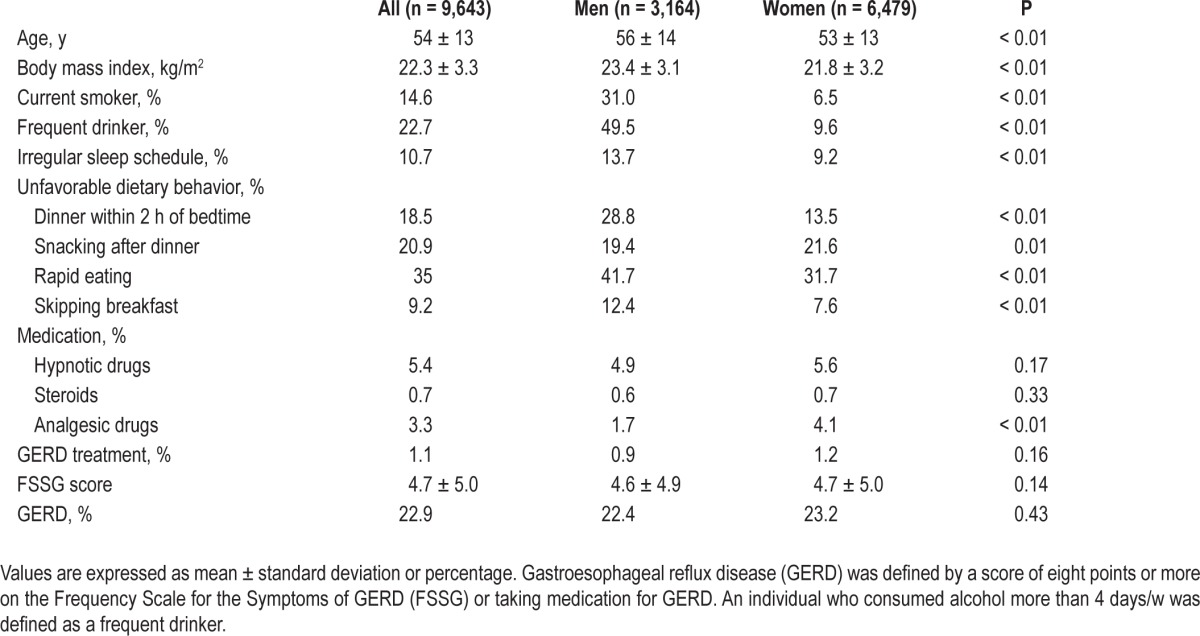

Basic clinical characteristics of study participants are summarized in Table 1. Of the total of 9,643 participants, the diagnosis of GERD was made in 2,210 (22.9%), and the prevalence of GERD as well as the mean FSSG score did not differ between men and women. In contrast, unfavorable dietary behaviors except for snacking after dinner were more frequent in men than in women. Frequency of an irregular sleep schedule was also higher in male than in female participants.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study participants.

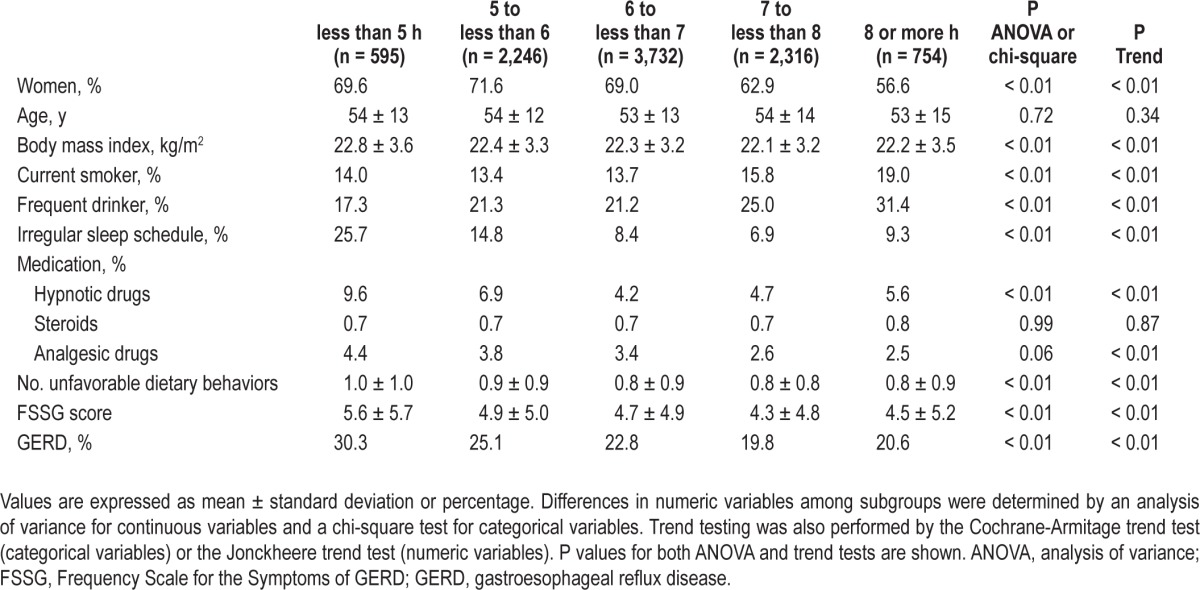

Table 2 shows the differences in clinical characteristics of subjects according to sleep duration. In the trend analysis, factors positively associated with short sleep duration were female sex, body mass index, irregular sleep schedule, and consumption of hypnotic or analgesic drugs, whereas frequent drinking and current smoking showed opposite associations. The frequency of GERD as well as the number of unfavorable dietary behaviors were also increased with decreasing sleep duration.

Table 2.

Differences in clinical characteristics according to sleep duration.

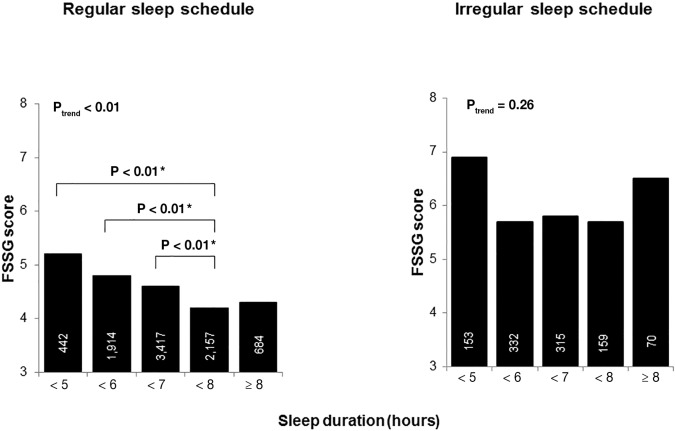

Because the frequency of an irregular sleep schedule was approximately three times higher in the highest group than in the lowest group, we conducted a separate analysis of the regularity of the sleep schedule. Results of trend analysis showed that an inverse association between sleep duration and the FSSG score was only seen in participants having a regular sleep schedule. Even though the relationship between FSSG score and sleep duration in participants with regular sleep schedule seemed to be inverse J-shaped curvilinear, a significant difference in FSSG score was not observed between groups with 7 to less than 8 h and 8 h or longer per day sleep duration. However, there were significant differences between the group with 7 to less than 8 h/day sleep duration and each group with less than 5 h, 5 to less than 6 h, and 6 to less than 7 h per day sleep duration. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

FSSG score for participants by sleep duration and with or without a regular sleep schedule. The bars represent the mean FSSG scores in each group. The numeral in each bar represents the number of participants in each group. The asterisk is explained as follows: The comparisons of FSSG score among groups categorized by sleep duration were performed with Dunnet test using the group with 7 h to less than 8 h per day sleep duration as the reference. In participants with regular sleep schedule, there were significant differences between the reference group and each of group with less than 5 h, 5 to less than 6 h, and 6 to less than 7 h per day sleep duration, whereas there was no significant differences with the group with 8 or more h per day sleep duration. However, in participants with an irregular sleep schedule, the significant difference was not found between the reference and any of the other groups. FSSG, Frequency Scale for the Symptoms of GERD. GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

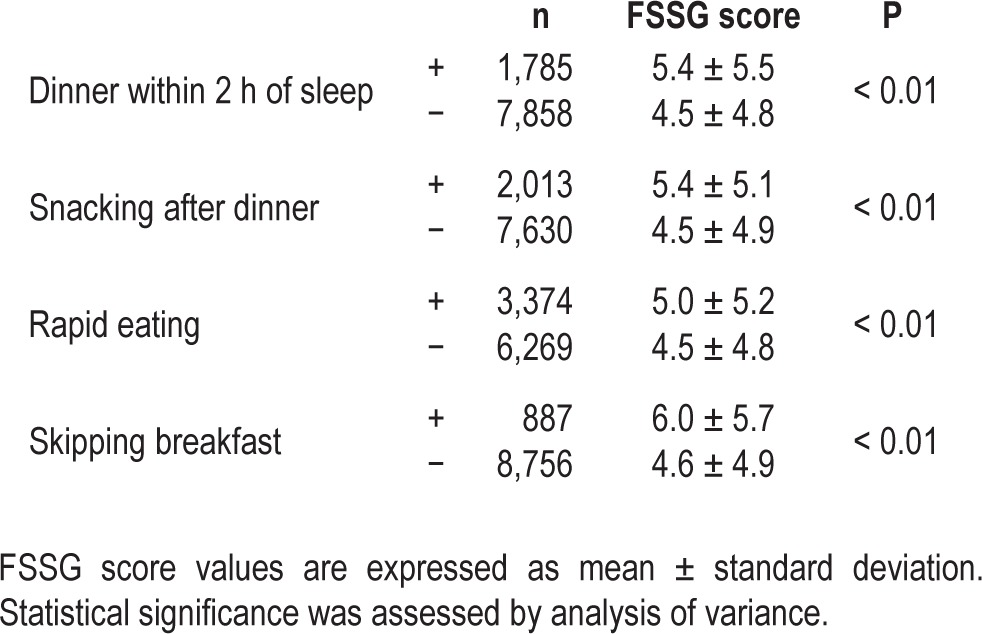

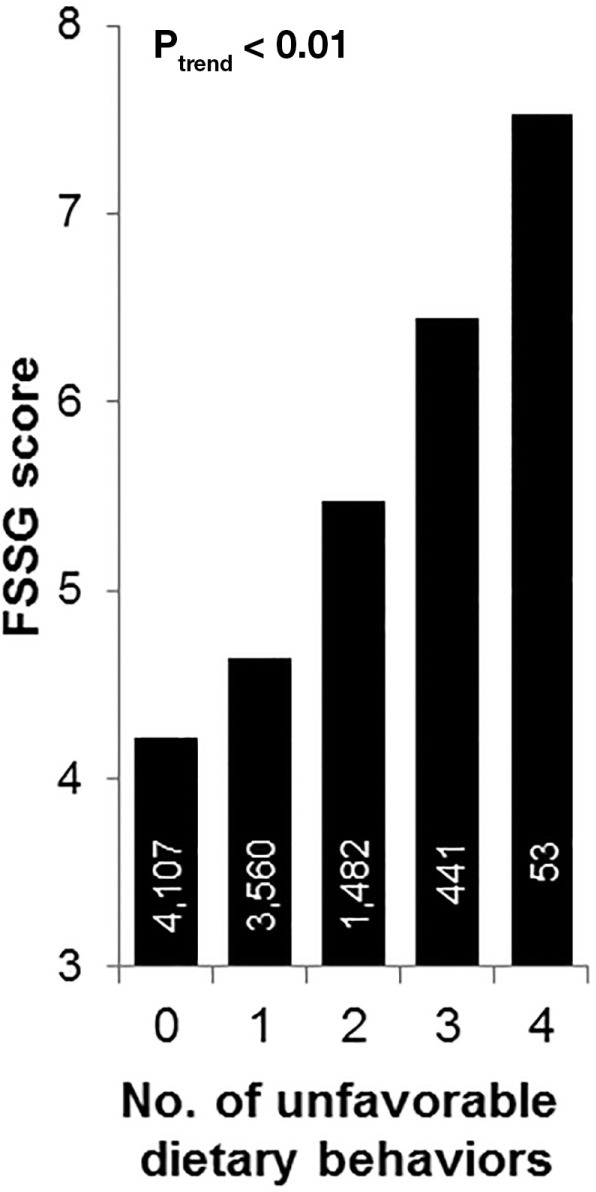

The association between each dietary habit and the FSSG scores are summarized in Table 3. All of the investigated dietary behaviors were associated with a significantly higher FSSG score. Further, the accumulation of unfavorable dietary behaviors showed a stepwise association with the FSSG score (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Frequency Scale for the Symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease scores in subjects with or without each examined dietary behavior.

Figure 2.

Association between FSSG score and the number of unfavorable dietary behaviors. The bars represent the mean FSSG score in each group. The numeral in each bar represents the number of participants in each group. FSSG, Frequency Scale for the Symptoms of GERD. GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

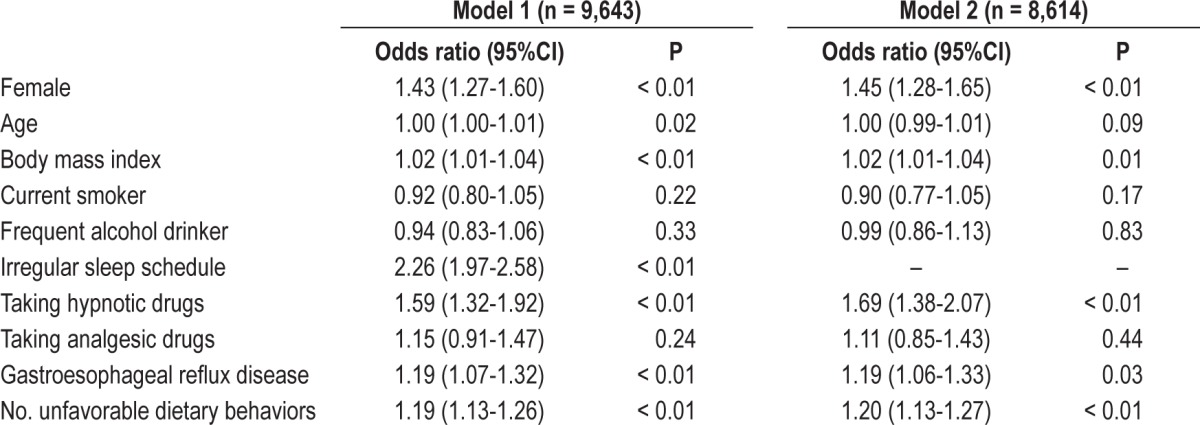

To further identify factors independently associated with short sleep duration, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed with adjustments for possible covariates (Table 4, Model 1). Results showed that both GERD and the number of unfavorable dietary behaviors were independently associated with short sleep duration, even in the analysis that did not include participants having an irregular sleep schedule. (Table 4, Model 2) No interaction was observed between GERD and the number of unfavorable dietary habits (P = 0.82).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine the factors identifying participants with short sleep duration.

DISCUSSION

The current result showed that the frequency of GERD as well as the number of unfavorable dietary behaviors were also increased with decreasing sleep duration, and that both GERD symptoms and unfavorable dietary behaviors were associated with short sleep duration independently of other clinical variables in a large sample from the general population. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that showed the prevalence of GERD in the general population according to their sleep duration, and evaluated GERD symptoms and dietary behaviors comprehensively to determine if they were significant correlates of short sleep duration in a large sample from the general population.

Several previous studies have investigated the associations between only two of these three factors, i.e., sleep duration, GERD symptoms, and dietary behaviors. Matsuki et al. showed in their hospital-based study that subjects with GERD symptoms were more likely to report short sleep duration than those without such symptoms14 and suggested that the relationship between sleep duration and GERD was bidirectional based on other previous studies.24–26 With regard to the correlation between dietary behaviors and sleep duration, Kim et al. found in their epidemiologic study that female subjects with short sleep duration tended to eat meals during unconventional hours.17 Persons with short sleep duration may tend to go to bed later and thereby have more opportunities to eat at later hours. Change in the physiological regulation of metabolic hormones that influence diet and eating patterns is another possible explanation.27 In addition, a positive association between GERD symptoms and unfavorable dietary behaviors also was reported.16,28 However, no previous study has investigated whether GERD and dietary behaviors are independently associated with sleep duration. This is the first study to clarify that both GERD symptoms and unfavorable dietary behaviors were correlated with short sleep duration independently of each other.

We evaluated sleep duration with a questionnaire. Although sleep duration examined by an objective measurement such as actigraphy may be desirable, self-reported sleep duration assessment was reported to be as valid as objective measurements.29 Because individuals with a short sleep duration were more likely to have an irregular sleep schedule, there might be a misperception of sleep duration in this group.30 However, in our analysis GERD and dietary behaviors remained significant determinants of sleep duration, except for in participants with an irregular sleep schedule. This finding emphasizes the result that GERD symptoms and dietary behaviors were associated with sleep duration independently of each other. In the current study, we did not obtain data about the specific types of sleep problems, such as difficulty getting to sleep and early morning awakening. Investigations of sleep problems specifically correlated with GERD symptoms and dietary behavior are warranted.

We also evaluated the severity of GERD symptoms with the questionnaire. Several diseases, such as functional dyspepsia and nonerosive reflux disease, can cause GERD symptoms; the sensitivity of FSSG scale for detecting the patients with abnormal endoscopic findings of GERD has been reported to be 60%.21 Further, the severity of GERD symptoms is not always proportional to that of findings in endoscopy and pH monitoring.31,32 Therefore, further studies may be needed to examine whether the objectively measured GERD findings are a stronger explanation of short sleep duration than self-reported GERD symptoms.

In the current study, female sex, older age, and having a higher BMI were also positively associated with short sleep duration. Whereas many preceding studies reported a positive association between short sleep duration and obesity,1–3 the relationship between sleep duration and sex or age was inconsistent in previous studies.19,33–35 Although this finding may be caused by different ethnic and cultural influences or lifestyles, these previous studies did not take into account GERD symptoms and dietary behaviors as the determinants of sleep duration, which might explain these conflicting results. By taking these factors into account, the current study led us to a more sophisticated evaluation of the relationship between sleep duration and age or sex compared with previous studies.

We recognize the limitations of this study. First, the questionnaire that we adopted could not evaluate the sleep quality of each participant in detail. Second, we did not assess details of participants' socioeconomic background such as income, education level, and marital status, factors that were also reported to be associated with sleep duration.34,36 However, because Jansson et al. reported that GERD symptoms were associated with sleep problems independently of socioeconomic status, these factors might not have materially affected the current results.12 Third, because this study was based on cross-sectional observations, we could not show a causal relationship between sleep duration and GERD symptoms or dietary behaviors. To clarify the causal relationship among them, further studies investigating whether clinical interventions for GERD and dietary behaviors improve sleep shortage are warranted.

In conclusion, GERD symptoms and unfavorable dietary behaviors were significantly associated with short sleep duration in the general population independently from each other. Further studies are warranted to investigate whether interventions for GERD and dietary behaviors lead to improvement of sleep shortage.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was supported by a University Grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan, and a research grant from the Takeda Science Foundation. Dr. Chin declares that the Department of Respiratory Care and Sleep Control Medicine is funded by endowments from Philips-Respironics, Teijin Pharma, Fukuda Denshi, and Fukuda Life-Tech Kansai to Kyoto University. Dr. Kadotani reports that his laboratory is supported by donation from Philips Respironics to Shiga University of Medical Science and that he is a member of the Advisory Board for MSD and Sleepwell, doing collaboration work with Teijin and NPO 0-degree club. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wu MC, Yang YC, Wu JS, Wang RH, Lu FH, Chang CJ. Short sleep duration associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an apparently healthy population. Prev Med. 2012;55:305–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall MH, Okun ML, Sowers M, et al. Sleep is associated with the metabolic syndrome in a multi-ethnic cohort of midlife women: the SWAN Sleep Study. Sleep. 2012;35:783–90. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi KM, Lee JS, Park HS, Baik SH, Choi DS, Kim SM. Relationship between sleep duration and the metabolic syndrome: Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2001. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1091–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sands MR, Lauderdale DS, Liu K, et al. Short sleep duration is associated with carotid intima-media thickness among men in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Stroke. 2012;43:2858–64. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Liao D, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration and incident hypertension: the Penn State Cohort. Hypertension. 2012;60:929–35. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SJ, Lee SK, Kim SH, et al. Genetic association of short sleep duration with hypertension incidence--a 6-year follow-up in the Korean genome and epidemiology study. Circ J. 2012;76:907–13. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. quiz 1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–56. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiocca JC, Olmos JA, Salis GB, et al. Prevalence, clinical spectrum and atypical symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in Argentina: a nationwide population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:331–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kusano M, Kouzu T, Kawano T, Ohara S. Nationwide epidemiological study on gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep disorders in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:833–41. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaker R, Castell DO, Schoenfeld PS, Spechler SJ. Nighttime heartburn is an under-appreciated clinical problem that impacts sleep and daytime function: the results of a Gallup survey conducted on behalf of the American Gastroenterological Association. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1487–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Wallander MA, et al. A population-based study showing an association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep problems. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:960–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mody R, Bolge SC, Kannan H, Fass R. Effects of gastroesophageal reflux disease on sleep and outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:953–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuki N, Fujita T, Watanabe N, et al. Lifestyle factors associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:340–9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0649-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen MJ, Wu MS, Lin JT, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep quality in a Chinese population. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108:53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujiwara Y, Machida A, Watanabe Y, et al. Association between dinner-to-bed time and gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2633–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim S, DeRoo LA, Sandler DP. Eating patterns and nutritional characteristics associated with sleep duration. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:889–95. doi: 10.1017/S136898001000296X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohida T, Kamal AM, Uchiyama M, et al. The influence of lifestyle and health status factors on sleep loss among the Japanese general population. Sleep. 2001;24:333–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arora T, Jiang CQ, Thomas GN, et al. Self-reported long total sleep duration is associated with metabolic syndrome: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2317–9. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall MH, Muldoon MF, Jennings JR, Buysse DJ, Flory JD, Manuck SB. Self-reported sleep duration is associated with the metabolic syndrome in midlife adults. Sleep. 2008;31:635–43. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kusano M, Shimoyama Y, Sugimoto S, et al. Development and evaluation of FSSG: frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:888–91. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakamoto Y, Inamori M, Iwasaki T, et al. Relationship between upper gastrointestinal symptoms and diet therapy: examination using frequency scale for the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1635–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terada K, Muro S, Sato S, et al. Impact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms on COPD exacerbation. Thorax. 2008;63:951–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.092858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen L, Poh CH, Gasiorowska A, et al. Increased oesophageal acid exposure at the beginning of the recumbent period is primarily a recumbent-awake phenomenon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:787–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poh CH, Allen L, Malagon I, et al. Riser's reflux--an eye-opening experience. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:387–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schey R, Dickman R, Parthasarathy S, et al. Sleep deprivation is hyperalgesic in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1787–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamichi N, Mochizuki S, Asada-Hirayama I, et al. Lifestyle factors affecting gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a cross-sectional study of healthy 19864 adults using FSSG scores. BMC Med. 2012;10:45. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lockley SW, Skene DJ, Arendt J. Comparison between subjective and actigraphic measurement of sleep and sleep rhythms. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:175–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bianchi MT, Wang W, Klerman EB. Sleep misperception in healthy adults: implications for insomnia diagnosis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:547–54. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee KJ, Kwon HC, Cheong JY, Cho SW. Demographic, clinical, and psychological characteristics of the heartburn groups classified using the Rome III criteria and factors associated with the responsiveness to proton pump inhibitors in the gastroesophageal reflux disease group. Digestion. 2009;79:131–6. doi: 10.1159/000209848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacy BE, Talley NJ, Locke GR, 3rd, et al. Review article: current treatment options and management of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basner M, Fomberstein KM, Razavi FM, et al. American time use survey: sleep time and its relationship to waking activities. Sleep. 2007;30:1085–95. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tu X, Cai H, Gao YT, et al. Sleep duration and its correlates in middle-aged and elderly Chinese women: the Shanghai Women's Health Study. Sleep Med. 2012;13:1138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang J, Wheaton AG, Keenan NL, Greenlund KJ, Perry GS, Croft JB. Association of sleep duration and hypertension among US adults varies by age and sex. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:335–41. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Gimeno D, et al. Long working hours and sleep disturbances: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Sleep. 2009;32:737–45. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.6.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]