INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are chronic and progressive illnesses characterized by periodic exacerbations that frequently result in inpatient hospitalization.1 These illnesses account for approximately 1.5 million emergency department visits annually 2 with a high volume of subsequent visits for the same presenting problem.3 Worsening dyspnea, or shortness of breath, is commonly the precipitating symptom for why patients with these illnesses seek out medical care.4 Some patients, however, delay seeking care for worsening symptoms for reasons not well understood in the population of patients with chronic end-stage disease. The concept of delay was originally defined by clinicians as a way to understand why some patients wait to seek care. Patients often have their own reasons for not seeking medical care right away and avoiding another hospitalization was described by the patients in this study as the primary reason. This paper is a report of unexpected findings about how patients’ perceive their timing in seeking medical care for worsening symptoms from a study that explored the experiences of patients with advanced HF or COPD recently discharged from the hospital.

The concept of patient delay in seeking medical care has been defined as the period of time between the patients’ first recognition of a symptom to the time medical care is accessed for that symptom.5 Clinicians originally defined the concept as a way to understand why some patients waited longer to seek care than what is considered normal or optimal by the medical community. 6 Much of what is known about delay in seeking medical care has been focused on patients with acute coronary syndromes, such as myocardial infarction and stroke. 7 These illnesses typically have a sudden onset with a shorter period of delay due to the emergent nature of associated symptoms.

Illnesses such as HF and COPD have an exacerbating remitting trajectory characterized by a more gradual onset of worsening symptoms. Patients living with these chronic illnesses have come to recognize usual patterns of symptoms related to exacerbations and often wait for them to resolve on their own or worsen before seeking care. 5 A recent study by Nieuwenhuis and colleagues reported that a previous experience of hospitalization for HF was not associated with a shorter delay, indicating that prior knowledge of illness recognition may not be associated with a more rapid response to seek medical care. 5 In patients with HF, delay in seeking medical care has negative health consequences because early intervention improves patient outcomes.8,9 As a result, delay has been conceptualized as problematic and current interventions have been mainly focused on reducing delay.

The fear surrounding receiving a serious diagnosis has been found to be a factor associated with why some patients with other diagnoses, such as cancer, do not report symptoms right away and delay seeking medical care. 10 This is consistent with findings from a study that examined cancer survivors, whose fear of reoccurrence was identified as a factor associated with delaying reporting health related changes or worsening symptoms. 11 Attributing symptoms and bodily changes to a co-morbidity is another factor associated with the reluctance of patients to report symptoms to providers.11 Patients who have prior experience with their symptoms sometimes attempt to self manage with medications, and make excuses for their symptoms before seeking medical care.12,13 By reporting a new or worsening symptom, patients may have to undergo additional diagnostic testing. Patients may fear getting the results from diagnostic tests because it could confirm their worst fears, such as a receiving a new diagnosis, a reoccurrence of an existing diagnosis, or learning that an existing illness has worsened. 10

Identification of changes in health, including new or worsening symptoms, can have a significant impact on a person’s normal daily life or routine. Such changes disrupt the normal pattern of a patient’s life. 14 Maintaining and/or returning to normalcy have been identified as goals important to patients’ diagnosed with serious illnesses.14 Little is known about when and how patients with living with chronic HF or COPD report or seek care for new or worsening symptoms. What this paper aims to add is a greater understanding about how patients living with end stage cardiopulmonary disease perceive their timing in seeking medical care for symptoms.

METHODS

Study Design

The findings reported here were part of a larger qualitative descriptive study examining the experiences of patients with life threatening illnesses who were recently discharged from the hospital following an exacerbation of HF or COPD. 15 The aims of the parent study were to gain a deeper understanding about what it was like living with an advanced illness, what participants perceive their illness would be like in the future, and expectations from health care providers as their illness progressed. During the course of data collection, participants consistently spoke about their previous experiences with the hospital and thoughts about future hospitalizations within the context of what it was like living with an advanced illness. Hence this emerging concept was included in subsequent iterations of the interview guide and was found to be one of the main themes that were derived from the parent study. This report is focused exclusively on that theme.

Sample and Setting

Participants with advanced HF or COPD were recruited from two large Medicare-certified home health agencies in Western New York. The inclusion criteria were: (a) current home care patient, (b) home care admission diagnosis of either (1) NYS Class III–IV heart failure or (2) oxygen dependent COPD, (c) aged 18 and over, and (d) ability to understand and speak English. Patients were excluded from participating if they: (a) had a current cancer diagnosis, (b) had documentation of current significant psychiatric impairment or severe cognitive dysfunction including lack of capacity for decision making, and (c) were already enrolled in hospice care.

Procedures

Approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board at the authors’ University. Eligible patients were informed about the study by their home care nurse and were sent a study brochure and postcard to return if interested in speaking with the investigator. The return rate for postcards was 50%. Of those who responded 100% chose to participate. After informed consent was obtained, demographic data were collected from the participants’ home care medical record. Since our goal was to recruit participants whose illness was advanced enough to be eligible for hospice but who were not enrolled in hospice, we used clinical data from each patient’s medical record to evaluate medical eligibility for hospice. This included the both the patients’ primary diagnosis and evidence of functional decline using the Karnofsky Performance Scale score. 16 In the context of end-stage HF or COPD, a Karnofsky score of 50 or less indicates the need for considerable medical care.

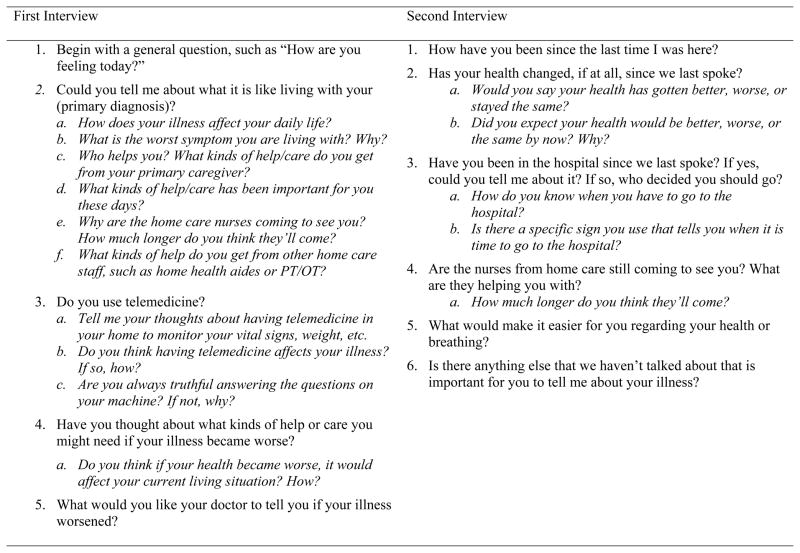

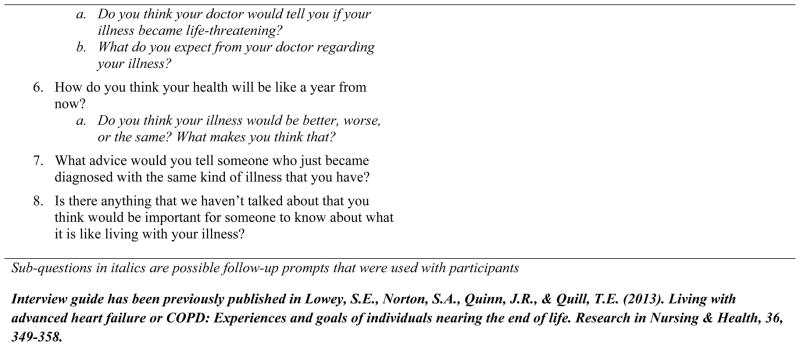

A total of 20 patients enrolled in the study. Two interviews with each participant were conducted by the principal investigator (SL) approximately 4 weeks apart. All face to face interviews were conducted in the participants’ homes and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Forty-five minutes (range 30–90 minutes) was the average length of most interviews. The semi-structured interview guide (Figure 1) was continually refined based on new ideas and concepts identified by participants during our analyses. The second interview was used to explore emerging themes, to collect insights that arose between the two interviews, and to explore any changes in health status or hospitalizations that occurred since the first interview. All 20 of the participants completed both interviews.

Figure 1.

Final Interview Guide

There was a slight risk for distress among participants during the interviews resulting from any discussion related to perceptions about future health and illness progression. While a few participants became teary when talking about their deceased spouses, no participants became distressed. While there was a plan in place for follow-up and care of patients who exhibited study related distress (both physiological and emotional), this was not needed.

Analysis

Data saturation was reached when no new concepts or perspectives were introduced during interviews. 17 Transcribed interviews were checked for accuracy and entered into Atlas Ti 6.0 data management software. Data were analyzed using a qualitative descriptive analysis approach. 17 This included an initial coding of text line by line. No a priori codes were used. Categories were then created from related codes and matrices were used to compare participants within and across cases. 18 The use of Atlas Ti enabled researchers to develop matrices on selected specific codes and categories which assisted with uncovering patterns in the data. Lastly, themes were developed based on patterns that described the phenomenon of interest. 19

Rigor

To maximize trustworthiness of this study, there were several elements built into the study design prior to data collection. Credibility was maximized by prolonged engagement with participants through 2 conversational style interviews averaging 45 minutes of length for most interviews. Member checks were done with two participants and an advanced practice cardiac nurse, which helped to validate findings. Regular feedback from the research team throughout the analytic process helped confirm the dependability of this study. An audit trail was kept to describe details of the processes and decisions made by the researchers during the study.

RESULTS

The study sample was comprised of 20 participants: 10 diagnosed with advanced HF and 10 with advanced COPD. Thirteen out of the 20 were diagnosed with both HF and COPD. The sample was predominately white (80%) with a mean age of 73 (range 52–93). Over half of participants lived alone and had no advance directive or designated proxy. Participants had an average of 2.5 hospitalizations over the past year and had been living with their advanced illness for an average of 5.5 years. In addition to a primary diagnosis of HF or COPD, the most common co-morbidities among the sample included: diabetes, osteoarthritis, and sleep apnea. Nearly all (90%) participants used an assistive medical device and took an average of 15 medications per day. Refer to Table 1 for a complete summary of participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Summary of Participant Characteristics

| Mean Age: 73.4 (range 52–93) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | Diagnosis |

| Female 11 | HF 10 |

| Male 9 | COPD 10 (both HF and COPD 13) |

| Marital Status | Ethnicity |

| Widowed 9 (45%) | Caucasian 16 (80%) |

| Married 7 (35%) | African-American 4 (20%) |

| Divorced 2 (10%) | |

| Single 2 (10%) | |

| Living Arrangement | Number hospitalizations past year: 2.6 (range 1–6) |

| Alone 11 (55%) | |

| With spouse 7 (35%) | Number daily prescription medications: 15 (range 10–30) |

| With son/daughter 2 (10%) | |

| Karnofsky score | Advance Directive |

| 1st interview 50 (range 30–60) | Health care proxy 9 (45%) |

| 2nd interview 46.5 (range 30–60) | None 11 (55%) |

| Medical equipment | Current Care Limitations |

| Walker/cane 18 (90%) | DNR 4 (20%) |

| Oxygen/nebulizer 15 (75%) | Molst 2 (10%) |

| Telemedicine 15 (75%) | None 14 (70%) |

| Wheelchair/scooter 5 (25%) | |

Avoiding the Hospital

The central reason participants identified waiting to report worsening symptoms was an overwhelming desire to avoid going back to the hospital. Participants did not perceive their timing in reporting symptoms or seeking medical care as a delay. Most had endured several losses throughout their illness trajectory, such as loss of functional ability, independence, and loss of control over their health. Since they felt no control over these things, participants felt they were in control over when and how they reported symptoms. Several participants often waited until symptoms became unbearable before reporting their symptoms to clinicians. The hospital symbolized both a loss of control and fear associated with worsening health (Table 2). These two sub-themes helped to frame their decisions about how/whether to discuss their symptoms with clinicians.

Table 2.

Verbatim Quotes Supporting the Theme, Avoiding the Hospital.

| Theme: Avoiding the Hospital | |

|---|---|

| Sub-Theme: Loss of Control Staying Home Manipulating Symptom Report |

“I just hate going to the hospital. You are in and out of ‘em so much you just hate going and want to stay home.” “I don’t tell ‘em the truth. As bad as I felt this morning I didn’t say anything, I told ‘em no [to being short of breath].” “No I’ll be honest with you I didn’t tell because I don’t want them sending me to the hospital.” |

| Sub-Theme: Fear of Worsening Health The Setback Losing Independence Death |

“Because every time I have a bout with the heart I end up on a short stint in the hospital I take one step forward and two back so that I’m always starting over again.” “No, no, no I’m fighting the hospital. Geez if I go to the hospital I’ll never come back here. I had a tough time getting out of the hospital and coming back here before. They wanted to send me to the nursing home.” “No I don’t want them sending me to the hospital because you know I’m terrified of the hospital because I think I’m gonna die. One time when they took me to the hospital, I almost did die.” |

Loss of Control: Staying Home and Manipulating Symptom Report

Staying home

Participants in this study had been hospitalized multiple times during the past year and were tired of going back and forth between the hospital and home. They wanted to stay home, such as this participant who was hospitalized three times in the past 6 months, “I just hate going to the hospital. You are in and out of ‘em so much you just hate going and want to stay home.” Most participants waited to see if symptoms would improve before they decided to seek care, such as this participant, “Yeah but I know when I have to go [hospital] but you try to hold out and see if things get better on their own”. Several of the participants wished that there was a treatment that could help their breathing at home, without having to go the hospital. Going to the hospital would bring a lot of unknowns to participants, such as whether or not they would be admitted, how long they would have to stay, and the fear associated with the loss of control that accompanies hospitalization for an exacerbation. “If they could come up with something where you have it right at home with you and you wouldn’t have to run to the hospital all the time, it would save me a lot of trouble”.

Manipulating symptom report

Most of the participants in this study had been living in a chronic cycle of transitions between the hospital and home. Participants disclosed symptoms but modified the severity of the symptoms because they wanted to avoid going back to the hospital. Most participants were quite knowledgeable about the consequences of disclosing certain symptoms. Several participants described that if they called their home care agency to report shortness of breath, a nurse would be sent out to assess them at home. The nurse would usually call their physician and then they would have to go to their doctor’s office. Several participants in this study described how they intentionally denied having symptoms, in order to avoid the hospital, “I don’t tell ‘em the truth. As bad as I felt this morning I didn’t say anything, I told ‘em no [to being short of breath].”Another participant with severe HF didn’t disclose the symptoms he was having on telemedicine, “No I’ll be honest with you I didn’t tell because I don’t want them sending me to the hospital.” Most participants felt going to the hospital at that point in time was unnecessary.

Fifteen of the 20 participants had home telemedicine as part of their home health care. In addition to the daily collection of clinical information, such as vital signs, telemedicine devices inquire about various symptoms. The patient would indicate their response through the telemedicine machine. Participants who were forced to engage in some type of symptom report, such as with telemedicine, often minimized or denied their symptoms, such as this participant with end-stage COPD, “And it’s like I said I’m really fine, it’s just a dizzy spell. I’m not going to any doctor. I don’t need you [nurse] to come out. Well my nurse called anyway and was coming out.” Participants framed their symptom reports according to their preferred outcomes. Most knew that if they reported a worsening of shortness of breath, they would be sent to the hospital. This participant with end-stage COPD described how whenever he told his doctor he had severe shortness of breath after being asked about it, he was always sent to the hospital, They [doctor] are so quick to judge and put me there [hospital] that I don’t know, I don’t tell him anymore.” Because they had multiple experiences to draw upon, participants described knowing which specific symptoms not to report or which to minimize in order to avoid a cascade of events which would likely lead to a hospitalization.

Fear of Worsening Health: The Setback, Losing Independence, and Death

The hospital symbolized a setback and a place of no return for participants in this study. Going to the hospital was a clear sign their illness was getting worse.

The setback

Going to the hospital was described by participants as a setback in their overall health and a place that resulted in an overall worsening of their health state. While the hospital might help to alleviate shortness of breath, the end result would be a decline in their overall health. This participant described what happened the last time he was hospitalized for an exacerbation, “Because every time I have a bout with the heart I end up on a short stint in the hospital I take one step forward and two back so that I’m always starting over again.” Participants also said it would take a lot of time to get back to normal once they returned from the hospital, so they tried everything they could do to avoid having to go back, such as this participant with end-stage HF, “If I can avoid another hospitalization I’d be better off. So I’ll do everything I can.”

Losing independence

The hospital was described as a place of no return that might precipitate a change in residence. Some feared not being able to return home after a hospitalization. This participant with end-stage HF thought that if he was hospitalized again he would lose his function and not be able to come back to his assisted living facility. “No, no, no I’m fighting the hospital. Geez if I go to the hospital I’ll never come back here. I had a tough time getting out of the hospital and coming back here before. They wanted to send me to the nursing home.” Another participant said, “No I just hate being kept in the hospital because one of these days I’m not gonna come out.”

Death

Other participants had negative thoughts about the hospital based on their prior experiences. This participant described a bad experience during her last hospitalization, “No I don’t want them sending me to the hospital because you know I’m terrified of the hospital because I think I’m gonna die. One time when they took me to the hospital, I almost did die.” Although participants were not directly asked about end of life issues during interviews, several candidly talked about death when describing their fears of being hospitalized. One of the reasons some participants feared the hospital was because they were afraid they might die there. Many told stories of how close they had already come to dying while in the hospital. This participant described a recent hospitalization where she thought she was going to die. “It was so bad I couldn’t sit up, I couldn’t lay down, I couldn’t breathe at all. And then they [nurses] stuck me in a room that they put people in when they were dying. And you know how much that terrifies a person? The reason she said they put me there was because they didn’t have no other rooms available. And you’re thinking they put you in this room cause you’re dying.”

Participants were well aware that by controlling what symptoms they reported to clinicians, they could avoid going to the hospital. The fear of not returning home or dying at the hospital led participants to omit reporting symptoms that might result in a hospitalization. Therefore, participants often waited until symptoms were unbearable before seeking care. For many participants in this study, the preference to avoid the hospital outweighed seeking care, regardless of the known consequences.

Study Limitations

The focus of this study was not to generalize findings to a broader population of persons with advanced illness, rather to describe the range of experiences among 20 home care patients living with advanced HF and COPD. Patients with HF and COPD receiving care in other settings, such as the hospital or in hospice care, might have different experiences and perspectives. Since many of the participants lived alone, perhaps the idea of having someone to talk to about their illness increased their desire to enroll in the study. It also might be assumed that as patients’ illness progresses, so could their attitudes and perceptions about health and the future, thus a more longitudinal approach may have been useful.

DISCUSSION

Participants in this study did not delay seeking care as a result of poor symptom recognition nor did they perceive their timing as being delayed. This supports previous research that reported 84% of patients believed their timing in seeking care were appropriate. 20 Patients in our study did not view the hospital as a place to get better instead it was a symbol for getting worse. Most waited to see if symptoms would improve before seeking care, in order to avoid hospitalization. Patel and colleagues also found 71% of patients with chronic HF as using a “wait and see” approach before seeking acute care for symptoms.4 Kleinman’s explanatory model is relevant to this work in terms of how patients perceive the consequences of their actions in terms of cause and effect.21 Kleinman’s model suggests that patients’ own experiences, realities and resources dictate their response to factors associated with their health. Their individual responses to exacerbations and timing in seeking medical care result from the beliefs patients have about the course of their illness. Patients living with end-stage cardiopulmonary disease have come to understand how the health care system works through prior health care use. Their understanding about reporting symptoms and seeking care seemed to be connected to their understanding about the course of illness.

To avoid disruption in their lives, patients did not report symptoms or reported only what they thought would not result in a hospitalization. In this study, patients clearly and deliberately framed their symptom reporting in order to achieve the results they preferred. Research on how clinicians frame information supports that framing can affect the outcome of the recipient of information.22 Framing is presenting the same option in different formats, either in terms of gains or losses, which alters an individual’s decision. Patients framed their symptoms according to their desired outcome. If they did not report worsening shortness of breath, they could avoid going to the hospital (gain) but they also might end up in critical care or die (loss). If they report worsening symptoms they might have loss of control by being admitted to the hospital (loss) but their breathing could improve (gain).

Findings from this study support previous literature surrounding care preferences of older patients with advanced illnesses. This work supports the work of Stromberg and Jaarsma 23 regarding thoughts about death and dying among patients with heart failure. Despite the fact that there were no questions that asked about death and dying, participants frequently talked about their fear of dying in the hospital. Additionally, this study adds to previous work surrounding patients’ experiences with hospital care in which care was viewed as unpredictable. 24 Most participants perceived the threat of not being able to return home, either from loss of independence or death. These were associated with the unpredictable nature of hospitalization.

Participants did not want to go back to the hospital and their actions in reporting, or lack thereof, symptoms clearly indicated that. It is important to note that none of the participants in this study were receiving any type of supportive or palliative care, despite the fact that they had end-stage disease and considerable symptom distress, particularly shortness of breath. All of these patients were receiving routine home care services on the cardiac team. While specialized cardiopulmonary care is beneficial for patients with HF and COPD in general, it may not be ideal for patients with end-stage disease, whose care preferences often differ from the curative care focused mindset of their clinicians. There is a dearth of papers that suggest incorporating palliative care alongside disease driven care, such as the model developed by Hupcey and colleagues. 25 Although most home health agencies have specialized palliative care teams, patients with end-stage HF and COPD infrequently get referred to home based palliative care during the hospital discharge process. Future work that examines the processes involved with post-acute care referrals during discharge to home care services should be examined.

Lastly, although palliative care has been shown to be successful in managing symptoms and providing comfort to patients with life threatening illnesses, much of this work has focused on patients with cancer, often in inpatient settings. Therefore, in addition to examining factors surrounding lack of referrals to home based palliative care programs for patients with end-stage cardiopulmonary disease, the science is also lacking an understanding about whether this service, in home care, is designed to meet the needs of the this population. Does home based palliative care as it is currently being implemented improve the outcomes for these patients versus routine or cardiac home care? In order to provide successful palliative care, patient preferences and goals for care need to be elicited prior to designation on a specific home care team. This would enable a more individualized process during discharge planning and a more successful home care experience for patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NIH/NINR Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (1F-31NR011125) and Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society Small Grant (09-00832).

References

- 1.Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Stedman M, Flavell CM, Levin R, Stevenson LW. Hospice, opiates, and acute care service use among the elderly before death from heart failure or cancer. Am Heart J. 2010;160(1):139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: Final data for 2009. National Health Center for Disease Statistics. National Vital Statistics Report. 2012;60(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cydulka RK, Rowe BH, Clark S, Emerman CL, Camargo CA. Emergency department management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the elderly: The multicenter airway research collaboration. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(7):908–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel H, Shafazand M, Schaufelberger M, Ekman I. Reasons for seeking acute care in chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(6):702–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieuwenhuis M, Jaarsma T, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Der Wal M. Factors associated with patient delay in seeking care after worsening symptoms in heart failure patients. J Card Fail. 2011;17(8):657–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gravely-Witte S, Jurgens CY, Tamim H, Grace SL. Length of delay in seeking medical care by patients with heart failure symptoms and the role of symptom-related factors: A narrative review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:1122–29. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moser DK, Kimble LP, Alberts MJ, Alonzo A, Croft JB, Dracup K, Zerwic JJ. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association council on cardiovascular nursing and stroke council. Circulation. 2006;114:168–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen L, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, Goldstein NE, Matlock DD, Arnold RM, Cook NR, Felker GM, Francis GS, Hauptman PJ, Havranek EP, Krumholz HM, Mancini D, Riegel BR, Spertus JA. Decision making in advanced heart failure: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:1928–52. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg RJ, Goldberg JH, Pruell S, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Spencer F, Gore JM. Delays in seeking medical care in hospitalized patients with decompensated heart failure. Am J Med. 2008;121:212–18. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Cancer Society. The emotional impact of a cancer diagnosis. 2013 Retrieved July 2, 2013 from: http://www.cancer.org.treatment/treatmentsandsideeffects/emotionalsideeffects/copingwithcancerineverydaylife/a-message-of-hope-emotional-impact-of-cancer.

- 11.Corner J, Hopkinson J, Fitzsimmons D, Barclay S, Muers M. Is late diagnosis of lung cancer inevitable?: Interview study of patients’ recollections of symptoms before diagnosis. Thorax. 2005;60:314–319. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.029264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corner J, Hopkinson J, Roffe L. Experience of health changes and reasons for delay in seeking care: A UK study of the months prior to the diagnosis of lung cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1381–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tod AM, Joanne R. Overcoming delay in the diagnosis of lung cancer: A qualitative study. Nurs Stan. 2010;24:35–43. doi: 10.7748/ns2010.04.24.31.35.c7690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilton BA. Getting back to normal: The family experience during early stage breast cancer. Oncol Nurs For. 1996;23:605–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Author YYYY. Living with advanced heart failure or COPD: Experiences and goals of individuals nearing the end of life. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36:349–358. doi: 10.1002/nur.21546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM, editor. Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. Vol. 196 New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15:85–109. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altice NF, Madigan EA. Factors associated with delayed care-seeking in hospitalized patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2012;41:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleinman A, Eisenburg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Annals Inter Med. 1978;88:251–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Retamero R, Galesic M. How to reduce the effect of framing on messages about health. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1323–1329. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1484-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stromberg A, Jaarsma T. Thoughts about death and perceived health status in elderly patients with heart failure. Euro J Heart Fail. 2008;10:608–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekman I, Lundman B, Norberg A. The meaning of hospital care, as narrated by elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Heart & Lung. 1999;28:203–09. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(99)70060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hupcey JE, Penrod J, Fenstermacher K. A model of palliative care for heart failure. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2009;26:399–404. doi: 10.1177/1049909109333935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]