Abstract

Background

Recent research has identified impairment in processing speed, measured by the digit–symbol substitution task, as central to the cognitive deficit in schizophrenia. However, the underlying cognitive correlates of this impairment remain unknown.

Methods

A sample of cases (N=125) meeting DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia and a sample of community controls (N=272) from the same geographical area completedaset of putative measures of processing-speed ability to which we implemented confirmatory factor and structural regression modelling in order to elucidate the latent structure of processing speed. Next, we tested the degree to which the structural and relational portions of the model were equal across groups.

Results

Processing-speed ability was best defined, in both controls and cases (χ2=38.5926, p=0.053), as a multidimensional cognitive ability consisting of three latent factors comprising: psychomotor speed, sequencing and shifting, and verbal fluency. However, cases exhibited dedifferentiation (i.e., markedly stronger inter-correlations between factors; χ2=59.9429, p < .01) and a reliance on an alternative ensemble of cognitive operations to controls when completing the digit–symbol substitution task.

Conclusion

Dedifferentiation of processing-speed ability in schizophrenia and subsequent overreliance on alternative (and possibly less than optimal) cognitive operations underlies the marked deficit observed on the digit– symbol substitution task.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Cognition, Processing speed, Dedifferentiation, Confirmatory factor modelling

1. Introduction

Cognitive impairment is ubiquitous in patients with schizophrenia (Reichenberg and Harvey, 2007), and is considered core to the pathophysiology of the illness (Green, 1996). Whilst deficits in attention, memory, working memory and executive functioning have been consistently reported (Reichenberg and Harvey, 2007), recently it has emerged that processing speed, as measured by the digit–symbol substitution task in particular, is the most impaired cognitive ability in schizophrenia (Henry and Crawford, 2005; Dickinson et al., 2007; Knowles et al., 2010). The significance of processing-speed ability in schizophrenia is further emphasised by its strong association with illness risk (Niendam et al., 2003; Glahn et al., 2007; Reichenberg et al., 2010), illness severity (Dickinson et al., 2007) and functional disability (Brekke et al., 2007). Whilst the importance of processing-speed in schizophrenia is well documented a critical question remains unanswered: what are the underlying cognitive correlates of the impairment?

Empirical evidence suggests that processing speed is a complex, multidimensional ability formed from a number of simpler cognitive sub-processes (Chiaravalloti et al., 2003). This suggests that a processing-speed task, such as the digit–symbol substitution task, could be teased apart to reveal its constituent cognitive sub-processes. For example, psychomotor speed, visual scanning, sustained attention and coordination of elementary operations have been proposed as possible contributors to performance on the digit–symbol substitution task (Joy et al., 2003; Lezak et al., 2004). Given a multidimensional model, the processing-speed impairment in schizophrenia may be underlain by unusual groupings of the sub-processes or, alternatively, by an abnormal application of the sub-processes to the digit–symbol substitution task.

Structural equation modelling allows detailed examination of the cognitive architecture of a given ability (Miyake et al., 2000). Under this approach, a hypothesised structure is developed based on theory and research findings, which is then validated empirically (Kline, 2005). Then that structure can be compared across diagnostic groups. Therefore the structural equation modelling approach is ideally suited to test hypotheses regarding the cognitive underpinnings of the processing speed impairment in schizophrenia. Previous research suggests that the general structure of cognition is largely the same in controls and schizophrenia cases but that the inter-correlations within that structure are significantly larger in cases suggesting that in schizophrenia there is ‘cognitive dedifferentiation’ (Dickinson et al., 2006). The cognitive dedif-ferentiation hypothesis reflects a phenomenon observed in old-age where cognitive abilities become increasingly correlated reflecting a decline in basic cognitive structures (Li and Lindenberger, 1999). Evidence from the field of cognitive ageing suggests an association between degree of dedifferentiation and cognitive ability such that greater dedifferentiation the greater the cognitive decline (Ghisletta and Lindenberger, 2003).

We report data from a large sample of schizophrenia cases and community controls that had completed multiple measures of processing speed. To this data we applied a series of modelling techniques. The aims of this study were to: (a) establish the structure of processing-speed ability and the way in which coding tasks fitted within this structure, and (b) examine whether differences between controls and cases in this structure could explain the coding-task deficit in schizophrenia. For the present study two hypotheses were tested: (1) the deficit is a result of disparity in the structure of processing-speed ability between schizophrenia cases and controls (2) if the structure is shown to be the same, a disparity in the relationships (for example, in the correlations between factors) within the model might explain the deficit. The present investigation is, to our knowledge, the largest rigorous study of processing speed ability in schizophrenia. Although there have been investigations of the structure general cognitive ability (IQ) in schizophrenia (Dickinson et al, 2006; Genderson et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010; Dickinson et al., 2010), this is the first study to focus in detail on the structure of processing-speed ability, and the abnormalities that characterize schizophrenia.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants comprised 125 schizophrenia patients (cases) and 272 controls. The study was approved by ethics committees in Israel and the US, and each participant gave written informed consent. Cases were consecutively recruited at the Sheba Medical Centre (Tel Aviv, Israel) between 2006 and 2009. Inclusion criteria for cases were as follows: 1. At least two admissions to a psychiatric hospital with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia; 2. A chart diagnosis of schizophrenia; 3. No history of head trauma or neurological disease; and 4. No history of or any current substance or alcohol abuse.

Controls were ascertained from the same catchment area served by the medical centre using methods aimed at limiting sampling bias (Kern et al., 2008). Briefly, recruitment procedures adhered to a scientific survey sampling method. Residential telephone numbers in the catchment area served by the medical centre were randomly sampled. Research staff members called these numbers, conducted preliminary screening for demographic characteristics, and using a prepared script explaining the purpose of the study, asked whether respondents would consider participating. Persons who passed the initial screening and who were interested in participating were invited for diagnostic and neuropsychological assessment. The average age of cases was 31.58 (range 20–67) years of age (68% males), and had on average 11.73 years of education. The average age of controls was 40.96 (range 17–65)years of age (34% males), and had on average 14.33 years of education. For the schizophrenia group the scales for the assessment of positive and negative symptoms (the SAPS and the SANS respectively) were administered, the mean SAPS score was 10.97 (SD=16.11) and the SANS was 28.89 (SD=23.56).

2.2. Diagnostic assessment

The Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS) (Nurnberger et al., 1994) was administered. On the basis of the DIGS interview, medical records information, and interviews with cases’ relatives, consensus research DSM-IV diagnoses were reached for cases. Using information from the DIGS interview research DSM-IV diagnoses were also reached for controls. In order to obtain an appropriate control group and avoid ‘super normal’ controls, which can introduce bias in case–control studies (Kendler, 1990), controls were only excluded from the analyses if they had a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or any schizophrenia spectrum disorder, a history of head trauma or neurological disease; or any current substance or alcohol abuse.

2.3. Neuropsychological assessment of processing speed

A comprehensive neuropsychological battery was administered to all participants. Processing speed tests were selected in accordance with the definition of processing speed posited by Salthouse (1996) such that tests were required to be administered under timed conditions. They also covered abilities previously suggested to be involved in DSST completion including psychomotor speed, visual scanning, sustained attention and coordination of elementary operations (Lezak et al., 2004). Also, tests of both motor and verbal ability were included. Finally, tests were required to be well standardised and with known psychometric properties (see Table 1 for a list of the included tests). Many of the included tests make up part of the trail Making Test from the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System Battery (D-KEFS; Delis et al., 2001). The test battery is generally considered to have good reliability and validity including the less known visual scanning and simple motor speed measures — test–retest reliability for these items are .56 and .77 respectively and inter-rater reliability is high (Delis et al., 2001). In terms of validity the motor speed task correlates highly with the finger tapping test which is a traditional measure of basic motor speed (Kraybill et al., 2007); whilst the format of the visual scanning task is essentially identical to a cancellation task which is a well-established measure of basic visuomotor skills (Lezak et al., 2004).

Table 1.

Neuropsychological measures of processing speed.

| Test | Unit of measurement |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| Visual scanning | Time taken to complete the task (seconds) |

Participants were presented with an array of letters and numbers and they were asked to cross all of a particular number. |

| Simple motor speed |

Participants were required to follow and trace a dotted line. |

|

| Number sequencing |

This is a modified version of the trail making test part A in which participants were presented with an array of numbers and they were required to connect them in numerical order. |

|

| Letter sequencing |

This is a modified version of the trail making test part A in which participants were presented with an array of letters and they were required to connect them in alphabetical order. |

|

| Number–letter switching |

This is a modified version of the trail making test part B in which participants were presented with an array of numbers and letters and they were required to shift back and forth between connecting numbers and letters in order. |

|

| Letter fluency | Number of words generated |

This task required participants to produce as many words as possible that begin with a certain letter, for example ‘F’, within 1 min. |

| Category fluency |

This task required participants to produce as many words as possible that belong to a certain category, for example ‘animals’ within 1 min. |

|

| Digit–symbol substitution task |

Number of correct digit–symbol pairings |

This task required participants to fill in rows containing blank squares each with a randomly assigned number above it using a key of symbol–number pairs. |

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Data preparation

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses and structural equation modelling techniques are highly susceptible to the influence of outliers and as a consequence data were carefully screened (for detail see Supplementary materials). There was no evidence of potential bias. Estimates for the number of participants required for structural equation modelling analyses vary in the literature. However, Monte Carlo simulations of structural equation modelling suggest that samples of at least one-hundred cases are required to confer enough power for models to converge with a good degree of accuracy (Loehlin, 1992).

2.5. Model building

First exploratory factor analysis was conducted in the control sample to give a preliminary indication of the probable groupings of measures. Next a two-stage model building technique was applied to the data whereby a measurement model was constructed followed by the addition of a structural model (Miyake et al., 2000).

2.6. Exploratory factor analysis

A maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis was implemented in controls using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 15.0 (Inc. SPSS, 2006). This approach is best suited to finding latent factors in a dataset with few variables (Tabachnick, 2007). An oblique rotation (promax) was applied to the data because latent factors were expected to correlate. The suggested number of factors was assessed using scree plots and residual correlation matrices (Tabachnick, 2007).

2.7. Measurement model (confirmatory factor analysis)

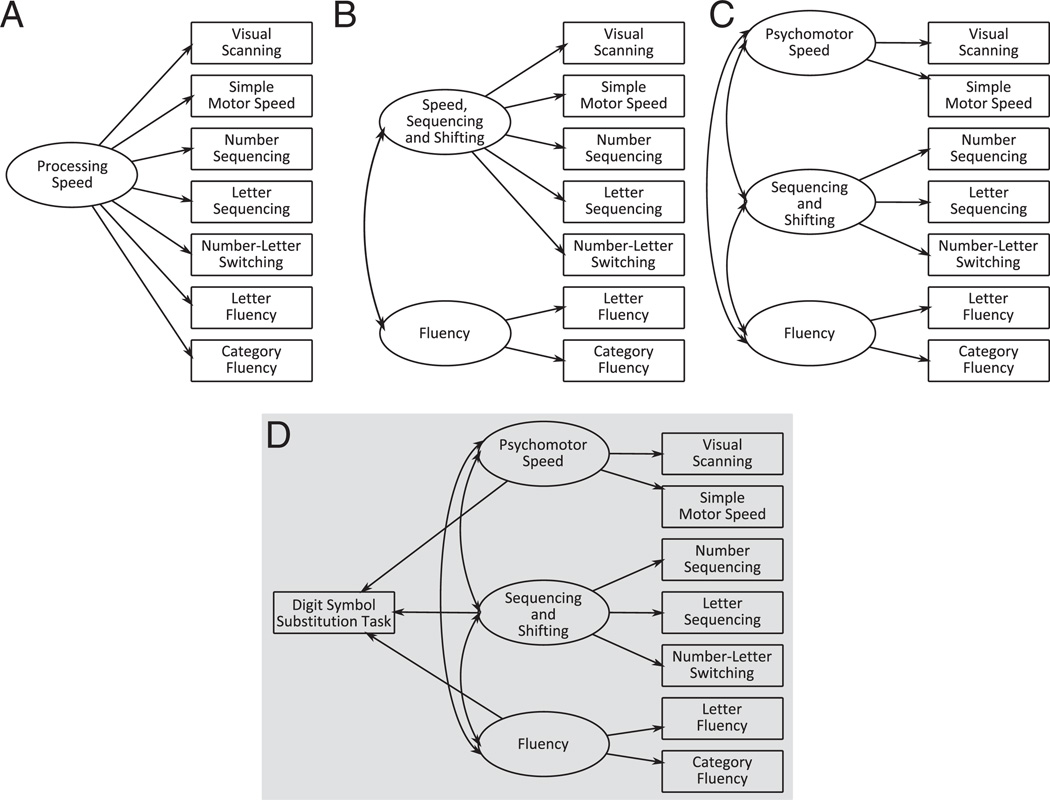

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using Analysis of Momentary Structure 7.0 software (AMOS) (Arbuckle, 2006). If processing speed, as measured in the present study, is a unitary ability then a one-factor model should fit the data no worse than the two- or three-factor models. However if processing speed is a multidimensional ability then the two- or three-factor models should derive the best model fit. In accordance with the exploratory factor analysis we postulated a three-factor model (including psychomotor speed, sequencing and shifting, and fluency) for processing speed and compared this to a two- (including speed, sequencing and shifting and fluency) and a one-factor (general processing speed) model (see Fig. 1A – C).

Fig. 1.

A schematic of the postulated A. one-factor, B. two-factor, C. three-factor and D. structural models.

2.8. Structural model (structural regression modelling)

The structural portion of the model sought to identify to what degree each factor of the processing-speed ability might contribute to digit–symbol substitution performance. We postulated a three-path model (see Fig. 1D) where all factors contributed to digit–symbol substitution performance. Alternative versions of this model, with various combinations of one or two paths, were tested using a nested models approach. Each solution was assessed using both the model fit indices and the strength and significance of the regression coefficients.

2.9. Hypothesis testing using multigroup comparisons

The next analysis was designed to test the hypotheses regarding the underlying cognitive architecture of the processing-speed deficit in schizophrenia using the factorial model developed during the preceding stages. To this aim multigroup comparisons were conducted using a factorial invariance approach whereby the equality of models across groups was tested in an increasingly restrictive fashion (Meredith, 1993).

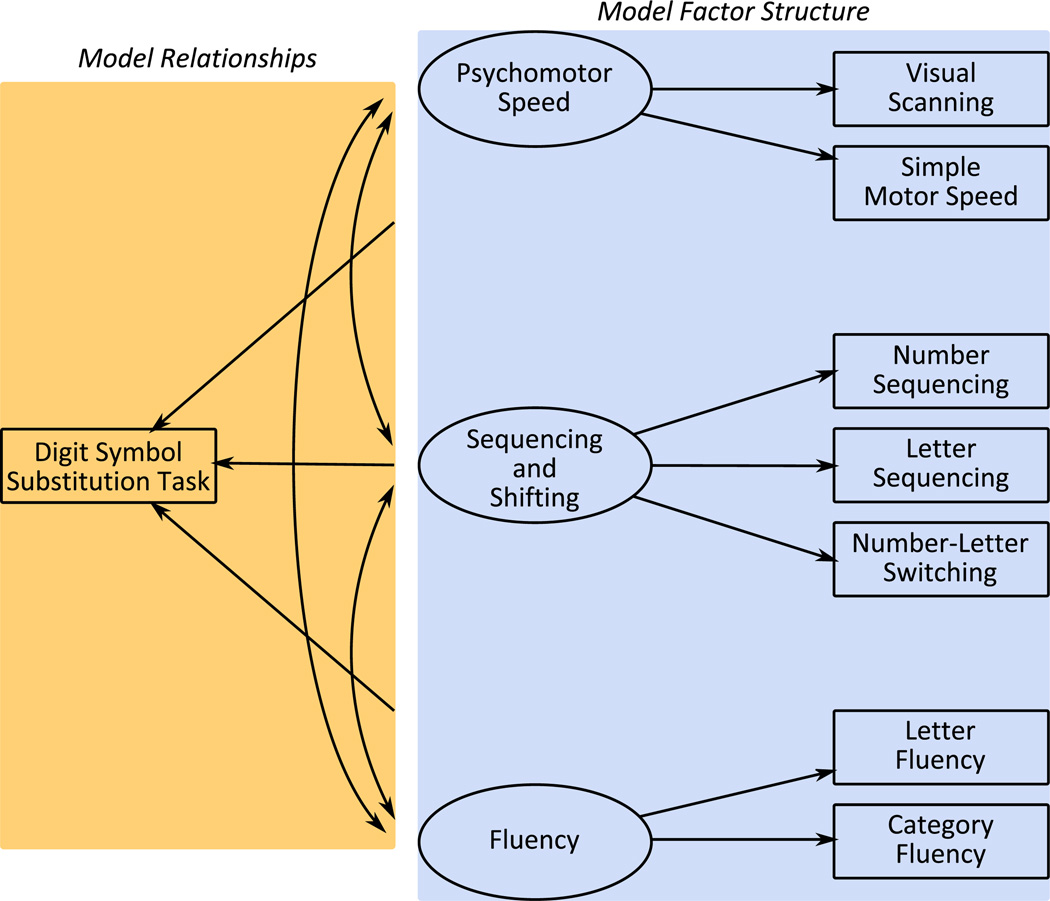

To test the first hypothesis that the processing-speed deficit is underlain by a disparity in the factor structure of the ability we tested the extent to which the factor structure and factor loadings were equal across groups (see Fig. 2, the right-hand blue panel). To test the second hypothesis that a disparity in the relationships within the ability underlies the processing-speed deficit we assessed the extent to which the factor covariances and structural portion of the model were equal across groups (see Fig. 2, the left-hand yellow panel). Thus model fit indices were compared when the factor structure and then the factor relationships were unconstrained (when they were allowed to differ across groups) versus when they were constrained to be equal.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the multigroup comparisons.

2.10. Indices of model comparison

Models were generated using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). In the first instance model fit was assessed using the χ2 statistic. Larger and significant χ2 values suggest greater discrepancy between expected and observed covariance matrices. However χ2 is a conservative index, likely to reach significance at large sample sizes, therefore it was important to utilise additional indices of model fit. We employed the comparative fit index (CFI), Akaike‧s information criterion (AIC), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the parsimony normed fit index (NFI). For CFI and NFI the closer the value is to 1.0 the better the fit of the model, with a value of .9 indicating acceptable model fit. For AIC no absolute value is indicative of good model fit, instead when comparing models those with a lower value of AIC are better fitting. Lastly, for RMSEA an adequate fit is denoted by a value of less than .08 and a good fit by a value equal to or less than .05.

When assessing model fit it is important to take into account a selection of different fit indices as each has its own strengths (Kline, 2005). Thus ‘model fit’ refers to an overall assessment of all of the fit indices outlined above (including: χ2, CFI, AIC, RMSEA and NFI). When establishing the factor structure of processing-speed ability via confirmatory factor analysis the alternative factor models were compared using a nested models approach. Hence, the fit of the two-factor and three-factor models were compared to the fit of the one-factor model and then the model with the best fit was selected. Similarly, when establishing the structural portion of the model the fit of the two-path and one-path models was compared to that of the three-path model. In addition the strength and the statistical significance of the regression coefficients were taken into account. When establishing the underpinnings of the processing-speed deficit by testing the equality of models across groups a depreciation in model fit when the groups were constrained to be equal (for either the factor structure or the factor relationships) was taken as an indication that the groups differed significantly.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics and group comparisons

As can be seen in Table 2, cases performed significantly worse than controls on all measures of processing speed (all p-values<0.001). The most severe impairment was on the digit–symbol substitution task followed by semantic fluency, and the smallest effect size was for simple motor speed. These effect sizes are similar to those reported in recent meta-analyses (Dickinson et al., 2007; Knowles et al., 2010). Table 3 presents Pearson‧s correlation coefficients between the measures of processing speed in cases and controls.

Table 2.

Performance of controls and cases on measures of processing speed.

| Task | Control (N=272) |

Schizophrenia (N=125) |

p-value | Effect size (Cohen’s d) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Digit–symbol substitution task |

74.14 | 16.87 | 47.68 | 19.24 | <.001 | −1.51 |

| Semantic fluency | 45.90 | 9.99 | 34.54 | 8.77 | <.001 | −1.18 |

| Number sequencing | 39.06 | 17.29 | 60.14 | 27.36 | <.001 | −1.12 |

| Letter fluency | 38.42 | 11.53 | 26.43 | 11.55 | <.001 | −1.04 |

| Letter sequencing | 83.52 | 40.83 | 128.64 | 62.36 | <.001 | −1.01 |

| Visual scanning | 23.24 | 7.27 | 32.11 | 12.85 | <.001 | −0.96 |

| Number–letter sequencing | 40.21 | 19.94 | 51.14 | 30.03 | <.001 | −0.93 |

| Simple motor speed | 38.79 | 14.01 | 60.52 | 28.02 | <.001 | −0.47 |

Table 3.

Correlations between measures of processing speed in controls (lower diagonal) and cases (upper diagonal).

| Psychomotor speed | Sequencing and shifting | Verbal fluency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual scanning |

Simple motor speed |

Number sequencing |

Letter sequencing |

Number- letter shifting |

Letter fluency |

Category fluency |

Digit- Symbol coding |

||

| Psychomotor Speed |

Visual scanning simple motor speed |

1 | .58** | .63** | .63** | .62** | −.42** | −.62** | −.69** |

| 0.46** | 1 | .63** | .58** | .62** | −.42** | −.62** | −.53** | ||

| Sequencing And shifting |

Number sequencing letter sequencing number- letter shifting |

0.51** | 0.39** | 1 | .73** | .62** | −.53** | −.45** | −.67** |

| 0.50** | 0.41** | 0.66** | 1 | −.70** | −.49** | −.47** | −.62** | ||

| 0.45** | 0.40** | 0.59** | 0.62** | 1 | −.56** | −.53** | −.62** | ||

| Verbal fluency |

Letter fluency category fluency |

−0.20** | − 0.20** |

−0.30** | −0.44** | −0.38** | 1 | .47** | −.58** |

| −0.26** | − 0.23** |

−0.30** | −0.36** | −0.32** | 0.47** | 1 | −.70** | ||

| Digit- symbol coding |

−0.41** | − 0.29** |

−0.49** | −0.54** | −0.53** | 0.35** | 0.40** | 1 | |

p<.001.

3.2. Exploratory factor analysis

The exploratory factor analysis revealed two factors, with the verbal fluency measures loading on one factor and the remaining measures loading on the other. However, large residual correlations suggested the possible presence of an additional factor (Tabachnick, 2007). The analysis was re-run using a forced three-factor solution, which resulted in very small residuals (with none larger than .01; see Supplementary materials Table S1). The number sequencing, letter sequencing and number–letter switching measures loaded on factor one, the verbal fluency measures loaded on factor two and the simple motor speed and visual scanning measures loaded on the third factor. These analyses suggested that processing speed is a multidimensional ability consisting of at least two, if not three, factors.

3.3. Measurement model

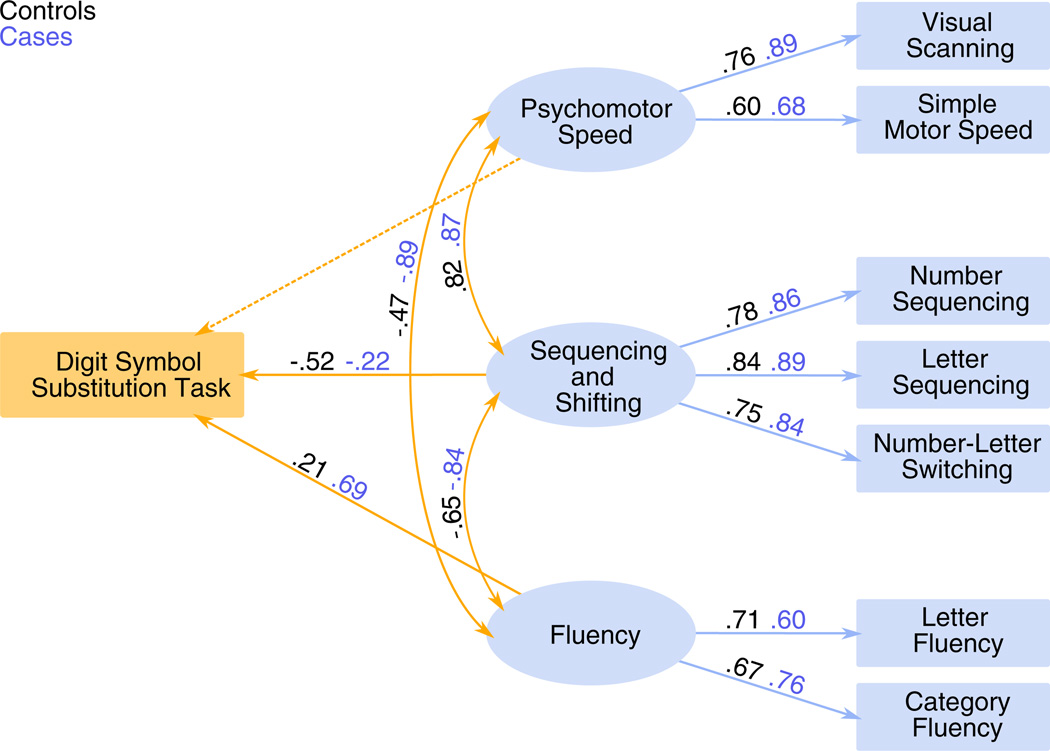

Table 4A presents the fit indices for the one, two and the three-factor models of processing speed for each group. In line with the results of the exploratory factor analysis the three-factor model (see Fig. 3) had the best fit to the data with good fit indices in both controls (χ2 = 11.4211, p = 0.45; RMSEA = .01; CFI = .99; NFI = 0.98) and cases (χ2 = 22.4911, p = 0.021; RMSEA = 0.093; CFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.91). This suggests that processing speed, as measured by the neuropsychological tests included here, is better characterised as a multidimensional three-factor model rather than a two-factor or a one-factor model. We conducted a sensitivity analysis whereby we tested alternative groupings of measures on factors (see Supplementary materials Table S2 for the tested combinations). However, the three-factor model posited here was the best fit. That two of the factors which include only two indicators should not affect the reliability of the model. Bollen‧s two-indicator rule states that if ‘a standard model with two or more factors has at least two indicators per factor, the model is identified’ so long as every construct is correlated with at least one other construct (Bollen, 1989; Kline, 2005).

Table 4.

Fit indices for A. measurement model building (confirmatory factor analysis) and B. the structural model building (structural regression model).

| df | χ2 | χ2/df | p | AIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Measurement models | |||||

| Controls | |||||

| Three-factor model | 11 | 11.42 | 1.04 | .45 | 59.42 |

| Two-factor model | 13 | 23.50 | 1.81 | .036 | 67.50 |

| One-factor model | 14 | 55.73 | 3.98 | <.001 | 97.73 |

| Cases | |||||

| Three-factor model | 11 | 22.49 | 2.04 | .021 | 70.85 |

| Two-factor model | 13 | 29.28 | 2.25 | .006 | 73.28 |

| One-factor model | 14 | 29.94 | 2.14 | .008 | 71.94 |

| B. Structural models | |||||

| Controls | |||||

| All paths | 15 | 16.56 | 1.10 | .346 | 74.56 |

| Psychomotor speed and sequencing and shifting |

16 | 22.29 | 1.39 | .134 | 78.29 |

| Psychomotor speed and verbal fluency |

16 | 20.44 | 1.28 | .201 | 76.44 |

| Sequencing and shifting and verbal fluency |

16 | 16.56 | 1.04 | .415 | 72.56 |

| Psychomotor speed | 17 | 34.43 | 2.03 | .007 | 88.43 |

| Shifting and sequencing | 17 | 35.66 | 2.10 | .005 | 89.66 |

| Verbal fluency | 17 | 21.37 | 1.26 | .210 | 75.37 |

| No paths | 18 | 147.68 | 8.20 | <.001 | 199.68 |

| Cases | |||||

| All paths | 15 | 25.61 | 1.71 | .042 | 83.62 |

| Psychomotor speed and sequencing and shifting |

16 | 25.71 | 1.61 | .058 | 81.71 |

| Psychomotor speed and verbal fluency |

16 | 28.80 | 1.80 | .025 | 84.80 |

| Sequencing and shifting and verbal fluency |

16 | 25.69 | 1.61 | .059 | 81.69 |

| Psychomotor speed | 17 | 28.87 | 1.70 | .036 | 82.87 |

| Shifting and sequencing | 17 | 25.94 | 1.52 | .076 | 79.94 |

| Verbal fluency | 17 | 31.97 | 1.88 | .015 | 85.97 |

| No paths | 18 | 141.56 | 7.86 | >.001 | 193.56 |

Fig. 3.

The final multidimensional model of processing speed. The measurement model is shown on the right in blue and the structural model is shown on the left in orange.

3.4. Structural model

Next we examined to what degree each factor of processing-speed ability was related to performance on the digit-symbol substitution task. Table 4B gives the fit indices for the one, two and three-path models for each group. In both controls (χ2 = 16.5616, p = 0.42; RMSEA = 0.01; CFI= 1.00 and NFI = 0.98) and cases (χ2 = 25.6916, p =0.59; RMSEA= 0.07; CFI = .98 and NFI = 0.94) the best fitting model was a two path model, with a path from sequencing and shifting (for controls, β-coefficient=−.52, p<.01 and for cases β-coefficient=−.23, p<.05) and the other from verbal fluency (for controls, β-coefficient=.21, p<.01, and for cases β-coefficient=−.91, p<.01). In neither group was the path from psychomotor speed to digit–symbol substitution task performance significant, which suggests that the digit–symbol substitution task is a measure of complex rather than simple level processing-speed ability.

3.5. Explaining potential underpinnings of the deficit in processing speed in schizophrenia

3.5.1. A disparity in the factor structure?

Table 5 gives the fit indices for the testing of model equality between groups. The factor structure, factor loadings, correlations between factors and the structural regression components were forced to be equal between groups and the fit indices were assessed in each case. Regarding the first hypothesis, the structure of processing speed was the same in controls and cases. It was possible to equate the factor structure (χ2=33.9622, p=0.050, RMSEA=.04, CFI=.99, NFI=.96) and factor loadings (χ2=38.5926, p=0.053, RMSEA= .04, CFI=.99, NFI=.96) across the control and case groups without significantly worsening model fit.

Table 5.

Fit indices for the hypothesis testing using multigroup comparisons.

| Equality of: | df | χ2 | p | AIC | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor structure | 22 | 33.96 | .050 | 129.96 | .99 |

| Factor loadings | 26 | 38.59 | .053 | 126.59 | .99 |

| Factor correlations | 29 | 54.94 | .003 | 136.94 | .97 |

| Structural model | 57 | 282.32 | <.001 | 344.32 | .80 |

3.6. A disparity in the relationships between factors?

Regarding the second hypothesis, the relationships within the model were significantly different between controls and cases. Equating the factor correlations across groups gave rise to a significantly worse model fit indicating that the factor correlations cannot be assumed to be equal across groups (χ2=59.9429, p=0.003). The factor correlation coefficients for both groups are shown in Fig. 3 (see curved, bidirectional arrows). Inspection of this figure suggests that the correlations between factors in the case group are consistently higher than those in the control group. This implies that processing speed is more dedifferentiated in cases than in healthy controls.

Next we examined the structural portion of the model, this was also significantly different between cases and controls (χ2=282.3257, p<.001). The structural portion of the model is shown in Fig. 3 (see single headed arrows connecting factors to the digit–symbol substitution task). Inspection of the coefficients associated with these paths shows that in controls the factor which best predicts performance on the digit–symbol substitution task is the sequencing and shifting factor, whilst in cases the verbal fluency factor best predicts coding task performance.

3.7. Moderator analysis

Previous research suggests that processing-speed ability varies as a function of age (Salthouse, 1996). Furthermore differences in cognitive ability and more specifically cognitive structure may arise between genders. When the effects of age and gender were partialled out the results of the CFA were precisely the same. It was possible to equate the factor structure (χ2=29.2922, p=0.137, RMSEA=.031, CFI=.99, NFI=.96) and factor loadings (χ2=35.5726, Δχ2=6.534, p=.180 RMSEA=.03, CFI=.99, NFI=.95) across the control and case groups without significantly worsening model fit. However, equating the factor covariances gave rise to a significant depreciation in model fit (χ2= 45.2929, Δχ2=16.00, p=.030, RMSEA=.04, CFI=.97, NFI=.93) where in cases the covariances were significantly greater (see Supplementary materials Table S3).

The differences in processing-speed structure within cases could not be explained by differences in medication status. There were no significant associations between type of anti-psychotic medication (typical vs. atypical) and processing-speed ability or treatment with anticholinergic medication and processing speed ability.

4. Discussion

Impaired processing speed in schizophrenia is well established and the hallmark of this deficit is slowed digit–symbol substitution task performance. The findings from the present study provide important insight into the cognitive underpinnings of the processing-speed deficit, specifically abnormal relationships within processing-speed ability and, perhaps as a result of this, that patients use a different ensemble of cognitive operations to complete the digit–symbol substitution task.

The results showed that both controls and cases had the same basic factor structure of processing speed consisting of three sub-processes (psychomotor speed, sequencing and shifting abilities and verbal fluency). However, in cases there was dedifferentiation: decreased specialisation of the sub-processes of the ability. Dedifferentiation was closely tied to poor performance. Healthy controls relied preferentially on sequencing and shifting abilities to complete the digit–symbol substitution task, which is what we might expect given the requirements of the measure. In contrast cases relied predominantly on the same processes that are required to complete verbal fluency tasks. The verbal fluency factor is arguably the factor most akin to effortful processing. Thus it appears that schizophrenia patients are seemingly unable to utilise the same cognitive processes that controls rely upon when completing the digit–symbol substitution task.

One possible explanation is that healthy controls, by virtue of their clearly defined processing-speed structure, should be able to selectively recruit only those sub-processes that are appropriate for successful task completion. Conversely for cases, because of the greater degree of overlap between sub-processes, it might be difficult to recruit only those that are necessary for the task at hand and consequently they rely on different cognitive processes to controls. Possibly in schizophrenia there is ‘an overreliance on effortful and prefrontally mediated processing’, a hypothesis presented by Dickinson et al. (2010).

Alternatively, this difficulty may be related to a general inefficiency in mental coordination in schizophrenia, or cognitive dysmetria, which results in problems with ‘prioritising, processing, coordinating and responding to information’ effectively (Andreasen et al., 1998). Thus the processing-speed deficit in schizophrenia could be explained by an imbalance of the otherwise finely tuned underlying sub-processes of the ability. Recent factor analytic studies of IQ in schizophrenia have shown that correlations between measures were stronger in schizophrenia than in relatives or healthy controls (Dickinson et al., 2006, 2010), suggesting that dedifferentiation of cognition in schizophrenia may be more general.

Dedifferentiation of cognition is thought to occur as part of the normal cognitive decline associated with the ageing process. The age differentiation hypothesis states that during childhood general cognitive ability becomes separated into specific abilities and then in older age biological changes in the brain cause the overlap between those specific cognitive abilities to become greater (Li and Lindenberger, 1999). Therefore the overlap of cognitive ability in schizophrenia can be described as akin to that seen in ageing individuals; given this it is not surprising that schizophrenia patients are more susceptible to the cognitive effects of ageing than healthy controls (Friedman et al., 2001; Kirkpatrick et al., 2008). It is possible that differentiation never occurs in individuals that go on to develop schizophrenia. This is in keeping with a neurodevelopmental hypothesis of the illness. According the neurodevelopmental hypothesis proposed by Feinberg (1982) the pruning of redundant synaptic connections, that usually occurs in adolescence and which serves to increase efficiency and specialisation of cortical regions, is aberrant in schizophrenia. The precise nature of this abnormality is unclear however a substantial body of evidence has accrued which supports the idea that neuronal abnormalities exist in the brains of schizophrenia patients particularly in the frontal cortex (Lesh et al., 2011). In support of the neurodevelopmental hypothesis those individuals that go on to develop schizophrenia exhibit cognitive deficits in childhood and then are subject to a developmental lag during adolescence (Niendam et al., 2003; Reichenberg et al., 2010).

Performance on the tasks included in the present study has been consistently linked to large-scale cortical networks and within those networks more specifically to the prefrontal cortex. Performance on both the trail making test (TMT) parts A and B (which correspond to the psychomotor speed and the sequencing and shifting factors respectively) have been associated with activation in the dorsolateral and medial prefrontal areas (Moll et al., 2002; Zakzanis et al., 2005; Shibuya-Tayoshi et al., 2007; Kubo et al., 2008). Similarly performance on verbal fluency tasks is associated with activation in the left inferior frontal gyrus (Baldo et al., 2006; Costafreda et al., 2006; Allen and Fong, 2008; Grogan et al., 2009; Kircher et al., 2009). This clear localisation of verbal fluency ability might be utilised in future functional and anatomical work to corroborate the results of the present study. If cases rely on verbal fluency ability to complete the digit–symbol substitution task then the left inferior frontal gyrus should show greater activation in cases than in healthy controls when completing the digit–symbol substitution task.

Whilst this study has a number of strengths, for example the use of chart diagnosis, it also has some potential limitations. It might be argued that the model presented in the current paper is not necessarily the definitive model of processing speed, as alternative specifications may fit the data equally well (Kline, 2005). Further the results presented here could be a reflection of method variance – that is a spurious relationship borne out of the very similar method shared by tasks – rather than the underlying structure of processing speed (Joy et al., 2000). In particular, it is not surprising that there should be a verbal fluency factor separate from factors characterised by motor tasks. However, the inclusion of verbal fluency measures was deemed appropriate given that these measures frequently load on processing-speed factors in factor analysis studies (Nuechterlein et al., 2004). A further criticism along a similar vein is that many of the included measures are from the D-KEFS (Delis et al., 2001). However, a reaction time task loaded significantly on the psychomotor speed factor (see, Supplementary materials Fig. S1) in controls (there was relatively less data for cases on this measure and so it was not included in the final model); which provides evidence that the proposed structure is not due to measurement selection but rather to an underlying structure of simple and complex sub-processes. Moreover the final groupings of measures were a result of exploratory and also confirmatory factor analysis whereby alternative groupings were carefully considered. Another potential limitation of the present study is the difference in gender distribution in controls and cases (34% male and 68% male respectively) which may affect the results given that previous research has shown that brain structure may vary between genders. However, when analysis was conducted on the processing-speed data after the effect of gender had been partialled out the results remained the same i.e. a three-factor model fit best in both groups and cases were characterised by marked dedifferentiation (see Supplementary materials). It is possible that processing-speed ability in different patient groups may be characterised differently, for example in a first-episode group. Indeed, alternative taxonomies of processing-speed ability have been posited prior to the model presented here, for example that included in the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory of cognitive abilities (McGrew, 2005). The present study has attempted to deconstruct the necessary requirements of successful digit–symbol substitution task completion. However, abilities other than processing speed may be involved in completing the digit–symbol substitution task for example memory. Previous research studies using two subtests of the digit–symbol substitution task have shown that processing-speed ability accounts for 50% of the variance associated with digit–symbol coding task performance whilst memory accounts for only 1% of additional variance (Kreiner and Ryan, 2001). However, it is of note that the processing-speed measures which appear to most strongly influence digit–symbol performance in this study are those that also require access to memory (for example, verbal fluency) which begets the authors to investigate this point further in future work.

In summary, the results of the present study suggest that the processing-speed impairment in schizophrenia is underlain by dediffer-entiation and the application of an alternative ensemble of cognitive operations to those seen in controls; and that these characteristics are evident in many, but not all cases, and are disease related. Future work should determine whether these characteristics are specific to schizophrenia, or also characterize other psychotic and affective disorders, and should seek to establish their anatomical and pharmacological underpinnings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the NIMH grant MH066105, and by the UK Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Specialist Bio-medical Research Centre for Mental Health award to South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) and the Institute of Psychiatry at King‧s College London. Dr. Dickinson is supported by the NIMH Intramural Research Program.

Footnotes

Contributors

AR & EK conceptualized and designed the study. MW & MD collected the data. EK performed data analyses. EK, MW, AD, DD, DG, JG, MD and AR examined and interpreted the results. EK wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which all co-authors commented on and edited.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.020.

References

- Allen MD, Fong AK. Clinical application of standardized cognitive assessment using fMRI II verbal fluency. Behav. Neurol. 2008;203:141–152. doi: 10.3233/BEN-2008-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Paradiso S, O’Leary DS. Cognitive dysmetria as an integrative theory of schizophrenia: a dysfunction in cortical-subcortical-cerebellar circuitry? Schizophr. Bull. 1998;242:203–218. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos. 7.0. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baldo JV, Schwartz S, Wilkins D, Dronkers NF. Role of frontal versus temporal cortex in verbal fluency as revealed voxel-based lesion symptom mapping. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2006;126:896–900. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706061078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brekke JS, Hoe M, Long J, Green MF. How neurocognition and social cognition influence functional change during community-based psychosocial rehabilitation for individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;335:1247–1256. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaravalloti ND, Christodoulou C, Demaree HA, DeLuca J. Differentiating simple versus complex processing speed: influence on new learning and memory performance. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2003;254:489–501. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.4.489.13878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costafreda SG, Fu CH, Lee L, Everitt B, Brammer MJ, David AS. A systematic review and quantitative appraisal of fMRI studies of verbal fluency: role of the left inferior frontal gyrus. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2006;2710:799–810. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer J. Delis–Kaplan Executive Function Scale. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Ragland JD, Calkins ME, Gold JM, Gur RC. A comparison of cognitive structure in schizophrenia patients and healthy controls using confirmatory factor analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2006;851-3:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Ramsey ME, Gold JM. Overlooking the obvious: a meta-analytic comparison of digit symbol coding tasks and other cognitive measures in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;645:532–542. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Goldberg TE, Gold JM, Elvevåg B, Weinberger DR. Cognitive factor structure and invariance in people With schizophrenia, their unaffected siblings, and controls. Bull. 2010;37(6):1157–1167. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg I. Schizophrenia: caused by a fault in programmed synaptic elimination during adolescence? J. Psychiatr. Res. 1982;174:319–334. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JI, Harvey PD, Coleman T, Moriarty PJ, Bowie C, Parrella M, et al. Six-year follow-up study of cognitive and functional status across the lifespan in schizophrenia: a comparison with Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;1589:1441–1448. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genderson MR, Dickinson D, Diaz-Asper CM, Egan MF, Weinberger DR, Goldberg TE. Factor analysis of neurocognitive tests in a large sample of schizophrenic probands, their siblings, and healthy controls. Schizophr. Res. 2007;941-3:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisletta P, Lindenberger U. Age-based structural dynamics between perceptual speed and knowledge in the Berlin Aging Study: direct evidence for ability dedif-ferentiation in old age. Psychol. Aging. 2003;18(4):696–713. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Almasy L, Blangero J, Burk GM, Estrada J, Peralta JM, et al. Adjudicating neurocognitive endophenotypes for schizophrenia. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007;144B2:242–249. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am. J. Psychiatry. 1996;1533:321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan A, Green DW, Ali N, Crinion JT, Price CJ. Structural correlates of semantic and phonemic fluency ability in first and second languages. Cereb. Cortex. 2009;1911:2690–2698. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. A meta-analytic review of verbal fluency deficits in schizophrenia relative to other neurocognitive deficits. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry. 2005;101:1–33. doi: 10.1080/13546800344000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inc. SPSS. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Joy S, Fein D, Kaplan E, Freedman M. Speed. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2000;67:770–780. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700677044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy S, Fein D, Kaplan E. Decoding digit symbol: speed, memory, and visual scanning. Assessment. 2003;101:56–65. doi: 10.1177/0095399702250335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS. The super-normal control group in psychiatric genetics: possible artifactual evidence for coaggregation. Psychiatr. Genet. 1990;12:737–742. [Google Scholar]

- Kern RS, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Baade LE, Fenton WS, Gold JM, et al. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 2: co-norming and standardization. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;1652:214–220. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher T, Krug A, Markov V, Whitney C, Krach S, Zerres K, et al. Genetic variation in the schizophrenia-risk gene neuregulin 1 correlates with brain activation and impaired speech production in a verbal fluency task in healthy individuals. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009;3010:3406–3416. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Messias E, Harvey PD, Fernandez-Egea E, Bowie CR. Is schizophrenia a syndrome of accelerated aging? Schizophr. Bull. 2008;346:1024–1032. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford, New York, London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles EEM, David AS, Reichenberg A. Processing speed deficits in schizophrenia: reexamining the evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2010;167828:835. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09070937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraybill M, Suchy Y, Eastvol A, Franchow E, Kuss K. Trail making and simple choice reaction time: double dissociation of motor speed and executive abilities. Poster presented at the International Neuropsychological Society, Portland, OR. 2007 Feb [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner DS, Ryan JJ. Memory and motor skill components of the wais-III digit symbol-coding subtest. Clin Neuropsychol. 2001;15(1):109–113. doi: 10.1076/clin.15.1.109.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M, Shoshi C, Kitawaki T, Takemoto R, Kinugasa K, Yoshida H, et al. Increase in prefrontal cortex blood flow during the computer version trail making test. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;583-4:200–210. doi: 10.1159/000201717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesh TA, Niendam TA, Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS. Cognitive control deficits in schizophrenia: mechanisms and meaning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;361:316–338. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW. Neuropsychological Assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li SC, Lindenberger U. Cross-level unification: a computational exploration of the link between deterioration of neurotransmitter systems and dedifferentiation of cognitive abilities in old age. In: Nilsson LG, Markowitsch H, editors. Cognitive Neuroscience of Memory. Hogrefe and Huber; 1999. pp. 103–146. [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Analysis. Hillsdale, N.J., London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew KS. Cattell–Horn–Carroll CHC theory of cognitive abilities: past, present and future. In: Flanagan D, Harrison PL, editors. Contemporary Intellectual Assessment: Theories Tests, Issues. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 136–202. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W. Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika. 1993;594:525–543. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn. Psychol. 2000;411:49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J, de Oliveira-Souza R, Moll FT, Bramati IE, Andreiuolo PA. The cerebral correlates of set-shifting: an fMRI study of the trail making test. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2002;604:900–905. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2002000600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Rosso IM, Sanchez LE, Hadley T, Nuechterlein KH, et al. A prospective study of childhood neurocognitive functioning in schizophrenic patients and their siblings. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2003;16011:2060–2062. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2004;721:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger JI, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies rationale, unique features, and training NIMH genetics initiative. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1994;5111:849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenberg A, Harvey PD. Neuropsychological impairments in schizophrenia: integration of performance-based and brain imaging findings. Psychol. Bull. 2007;1335:833–858. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenberg A, Caspi A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RS, Murray RM, et al. Static and dynamic cognitive deficits in childhood preceding adult schizophrenia: a 30-year study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2010;1672:160–169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychol. Rev. 1996;1033:403–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya-Tayoshi S, Sumitani S, Kikuchi K, Tanaka T, Tayoshi S, Ueno S, et al. Activation of the prefrontal cortex during the trail-making test detected with multichannel near-infrared spectroscopy. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007;616:616–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston Mass. London: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Vassos E, Deng W, Ma X, Hu X, Murray RM, et al. Factor structures of the neurocognitive assessments and familial analysis in first-episode schizophrenia patients, their relatives and controls. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2010;442:109–119. doi: 10.3109/00048670903270381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakzanis KK, Mraz R, Graham SJ. An fMRI study of the trail making test. Neuropsychologia. 2005;4313:1878–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.