Abstract

Purpose

To develop a better understanding of how yoga practice affects one’s interpersonal relationships.

Design

Qualitative.

Method

Content analysis was used to qualitatively analyze written comments (n = 171) made regarding yoga improving interpersonal relationships in a large cross-sectional survey of yoga practitioners (N = 1,067).

Findings

Four themes were identified: Yoga practice leads to personal transformation, increases social interaction, provides coping mechanisms to weather relationship losses and difficulties, and leads to spiritual transcendence. Practitioners believed that their interpersonal relationships improved because their attitude and perspective had changed, making them more patient, kind, mindful, and self-aware. They expressed an aspect of community that was both practical (they met new friends) and spiritual (they felt they belonged). They thought they could better weather difficulties such as divorce and death. A number discussed feeling a sense of purpose and that their practice contributed to a greater good.

Conclusions

There appears to be an aspect of community associated with yoga practice that may be beneficial to one’s social and spiritual health. Yoga could be beneficial for populations at risk for social isolation, such as those who are elderly, bereaved, and depressed, as well as individuals undergoing interpersonal crises.

Keywords: yoga, healing modalities, psychosocial, clinical/focus area, interpersonal, conceptual/theoretical descriptors/identifiers

Background and Significance

More than 13 million Americans practice yoga (Ross, Friedmann, Bevans, & Thomas, 2013), and many believe yoga improves their health (Author, YYYY). For centuries, the discipline, consisting of eight limbs (universal ethical principles, individual self-restraint, physical poses, breath work, quieting of the senses, concentration, meditation, and self-absorption or emancipation), was passed down from guru (teacher) to sisya (pupil), typically via one-on-one tutorials, usually while the pupil resided for an extended period of time with his teacher (Bryant, 2009). Classically, only males participated in yoga study. A great deal has changed over the past 100 years as yoga migrated West from India. The discipline has been opened to women, and the current format of teaching typically involves group instruction in yoga classes.

The physical, mental, and emotional health benefits of yoga have been studied extensively over the past several decades, and yoga has been shown to improve a number of health conditions including cardiometabolic conditions such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes (Innes, Bourguignon, & Taylor, 2005), cancer (Culos-Reed et al., 2012), arthritis (Büssing, Ostermann, Lüdtke, & Michalsen, 2012), asthma (Posadzki & Ernst, 2011), and psychiatric conditions such as depression (Uebelacker et al., 2010), anxiety (Kirkwood, Rampes, Tuffrey, Richardson, & Pilkington, 2005), and posttraumatic stress disorder (Meyer et al., 2012; Telles, Singh, & Balkrishna, 2012). Yoga is thought to elicit physical and mental health benefits by down-regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system response to stress (Ross & Thomas, 2010). Although the evidence supporting the health benefits of yoga is substantial, almost all of the research has focused on the practice of physical poses (asana), breath work (pranayama), and/or meditation. No published studies have examined whether the relationships one develops with one’s yoga teacher and peers provide health benefits above and beyond the benefits derived from the physical practice of yoga.

It is important to study the social aspects of yoga practice, because the quality of one’s social relationships and quantity of one’s social support are known to be important predictors of health (Umberson & Montez, 2010). Social isolation has such a profound psychological impact that it is frequently used as a form of punishment or torture. Indeed, the stress of social isolation is associated with negative cardiovascular outcomes (Brummett et al., 2001; Grant, Hamer, & Steptoe, 2009), as well as increased inflammation and impaired immune system function (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2003; Kiecolt-Glaser, Gouin, & Hantsoo, 2010). In 148 studies examining the impact of social relationships on mortality, strong social relationships consistently increased one’s odds of survival, regardless of one’s age, gender, or cause of death (Holt-Lundstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). Not only do close personal relationships make people healthier, they make them happier as well. Individuals in committed relationships or partnerships report greater subjective well-being, a measure of emotional health or happiness, than those in casual relationships, and individuals in happy relationships report higher subjective well-being than those in unhappy relationships (Dush & Amato, 2005).

Although social relationships are clearly important to one’s health and the practice of yoga historically has revolved around an intense relationship with one’s teacher and more recently with one’s peers in class settings, the authors could find no published articles discussing the therapeutic benefits of the social aspects of yoga. In a recent national survey of Iyengar yoga practitioners that we conducted at the University of Maryland School of Nursing, 67% of participants, regardless of race, gender, or education, agreed or strongly agreed that yoga helped improve their interpersonal relationships (Ross, Friedmann, Bevans, & Thomas, 2013); individuals with chronic health conditions were even more likely to agree that yoga improved their relationships. Participants in the study were invited to express their thoughts or comments about the impact of their yoga practice on their lives and interpersonal relationships; the purpose of this article is to analyze these comments in order to develop a better understanding of how yoga practice affects one’s interpersonal relationships and social health.

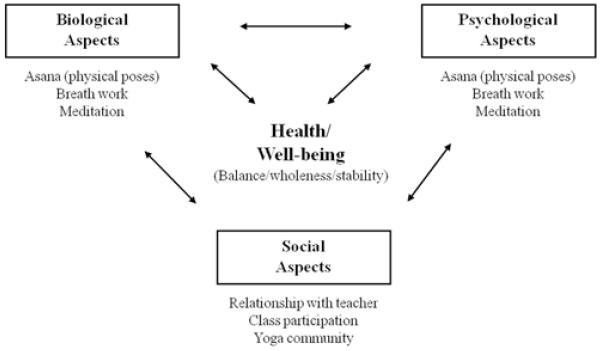

Conceptual Framework: Yoga and the Biopsychosocial Model of Health

The biopsychosocial model of health first proposed by Engel (1977) provides a comprehensive framework for understanding health and disease that is less reductionistic and more interactive than the traditional biomedical model. Whereas the traditional biomedical model views health and illness as linear, dualistic in nature, and a product of cause and effect relationships, the biopsychosocial model views health as far more complex and holistic. Instead of disease being due to a particular causative factor, it is viewed as a dynamic process involving the interplay of several factors from the biological, psychological, and sociocultural realms (Molina, 1983). According to the biopsychosocial model of health, numerous biological, psychological, and social factors interact and affect health outcomes in either a positive or a negative manner (Hoffman & Driscoll, 2000). Biological factors include age, race/ethnicity, gender, and preexisting health conditions. Psychological factors refer to emotional status, including depression, anxiety, reactions toward stress, and psychological and emotional well-being. Social factors focus on socioeconomic status and social ties, including friends and family as well as ties to one’s community and society. These three realms are dynamic, with the relative significance and impact of the factors varying between different individuals and within the same individual over different moments in time.

Although the idea of viewing health as involving more than physiological processes may have been viewed as innovative in Western medical thinking in the 1970s when Engel (1977) first proposed the model, the idea of a system of health that recognizes the connection between biological, psychological, and social aspects has been around thousands of years. Centuries of knowledge defining yoga and its effect on one’s body, mind, and interpersonal relationships exist in the form of the ancient text on yoga philosophy known as the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, as well as older texts such as the Upanishads (Bryant, 2009). According to the yoga sage Patanjali, the practice of yoga can be used first to tame the physical body and then the mind, so the individual can experience a sense of wholeness where the body, mind, and soul are integrated in health (Iyengar, 2001). Health, from a yogic perspective, is integration of the body, mind, and spirit, whereas illness is viewed as a state of disintegration (Iyengar, 1988). Although yoga is important for the growth of the individual and brings health and harmony to the body and mind, the effects of yoga are believed to extend beyond the individual to one’s family and society (Iyengar, 2005). The yogic view of health parallels Engel’s (1977) biopsychosocial model of health.

The authors adapted Engel’s (1977) model to create a biopsychosocial model of yoga and health (Figure 1). In this model, health is defined as a sense of balance, wholeness, and stability, and it consists of biological, psychological, and social aspects. These aspects are interrelated and interdependent, and total health cannot be achieved without balance and stability in all three aspects. Numerous randomized clinical trials have been performed examining the benefits of asana (yoga poses), pranayama (breath work), and meditation on mental and physical health (Büssing, Michalsen, Khalsa, Telles, & Sherman, 2012). The authors propose that in addition to the biological and psychological benefits of yoga practice, there are social benefits derived from having a relationship with one’s yoga teacher and interacting with one’s yoga community that can improve one’s social health, and ultimately one’s total health.

Figure 1.

Biopsychosocial Model of Yoga and Health Source: Adapted from Engel (1977).

Method

Design

The researchers used content analysis to explore the phenomenon of how the practice of yoga affects one’s relationships by qualitatively analyzing written comments made by participants. Content analysis is a qualitative research methodology used to analyze data from verbal, print, or electronic communications for the purpose of condensing, describing, and ultimately categorizing specific phenomenon (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Participants and Setting

This study is part of a larger cross-sectional anonymous survey that examined yoga practice patterns and aspects of health in yoga practitioners (Ross, Friedmann, Bevans, & Thomas, 2012). Subjects were included if they (a) were at least 18 years of age, (b) practiced yoga (either taking classes or practicing at home) at least weekly for a minimum of 2 months within the past 6 months, and (c) had Internet access and ability to complete an online survey.

The study was approved by the University of Maryland Baltimore Institutional Review Board. The researchers worked with the Iyengar Yoga National Association to identify 15 yoga studios with combined e-mail listserves of 18,160, taking steps to assure representation of all major regions of the country. Approximately 4,300 individuals were randomly selected from these 15 studios to receive an anonymous online survey asking detailed questions about their yoga practice and their health. Of the 1,167 who responded to the survey link, a final sample of 1,045 was acquired. A detailed description of the sampling process used in this study has been described elsewhere (Ross, Friedmann, Bevans, & Thomas, 2012). Despite 60% reporting at least one chronic or serious health condition (including 24.8% with depression), yoga practitioners in this study reported lower levels of obesity (4.9%) and smoking (2%), higher consumption of fruits and vegetables, and higher levels of happiness compared with national norms (Ross, Friedmann, Bevans, & Thomas, 2013). Subjects who practiced yoga more frequently exhibited more favorable levels of mindfulness, happiness, body mass index, fruit and vegetable consumption, vegetarian status, fatigue, and sleep than those who practiced less often (Ross, Friedmann, Bevans, & Thomas, 2013).

As part of the survey, participants were asked how much they agreed or disagreed that yoga improved a number of aspects of health. Participants agreed that yoga improved happiness (86.5%), energy (84.5%), sleep (68.5%), social relationships (67%), and body weight (57.3%). Subjects were invited to post comments following each of these questions. For this analysis, the researchers used comments posted to the question: “How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement: My relationships are better because of yoga.” Of the 1,045 individuals in the original study sample, 700 (67%) agreed or strongly agreed that yoga improved their relationships, and 171 posted comments to this question and are included in this study.

Data Analysis

Processes and Procedures

Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis. A number of methodological considerations were taken into account prior to data analysis. The researchers first identified the unit of analysis or the content area to be studied, which in this case consisted of subject’s open-ended comments to the statement, “My relationships are better because of yoga.” The researchers had to determine the study’s criteria, particularly whether the analysis would focus on the literal words in the text as written (manifest data) or on their underlying meaning implied within the text (latent data), or both (Berg, 1998). The researchers focused primarily on the latent meaning underlying the communications but used the exact words or phrases of subjects whenever possible, particularly when those words or phrases were used repeatedly. Because little has been published about the impact of yoga on one’s interpersonal relationships, the researcher focused on an inductive versus a deductive approach to analysis (Kondracki, Wellman, & Amundson, 2002). This approach allows descriptions, categories, and themes to arise from the data, as opposed to allowing preconceived ideas or theories to drive data analysis.

To enhance the validity and reliability of the findings, two investigators independently analyzed the data, and then they compared their findings. The investigators separately read through all of the comments several times, immersing themselves in the data. While reading through the statements, researchers made numerous notes in the margins. Often, exact quotes (words or phrases) were pulled from their statements. Notes that captured the essence of the person’s experience were placed on coding sheets, after which researchers began to abstract categories from these codes. The names of the categories would emerge that captured the underlying meaning of the category. Occasionally, a number of codes would be closely related but not necessarily identical. In these instances, subcategories or variations within a category would emerge. For example, one category that emerged was that subjects reported having more positive characteristics after starting yoga. Four subcategories of this category included being more insightful, happy, and tolerant, in addition to feeling better. Finally, the researchers worked together to group the categories into overriding themes. Graneheim and Lundman (2004) define themes as interpretations of the underlying meaning of an individual category or group of categories.

The investigators abstracted similar categories, although the number of categories differed (7 and 10, respectively). The investigators discussed their differences and came to a consensus on 10 categories, with 8 subcategories that fell under four major themes. As recommended by Elo and Kyngas (2008), the researchers identified authentic citations that served as exemplary examples of the category or subcategory.

Credibility and Legitimacy

One reasonably could argue that open-ended comments made in an anonymous survey might not adequately reflect the reality of one’s experience, as only those individuals able to articulate their experience would respond or the investigators might misinterpret those experiences. However, Geer (1988) found that open-ended questions used in surveys adequately capture individual’s experiences, and the anonymity of online surveys may lead to more honest responses (Erickson & Kaplan, 2000).

One problem confronted by the researchers was that because the surveys were anonymous, there was no opportunity for the researchers to validate the findings with participants. For this reason, two investigators conducted independent data analysis to validate the findings. As suggested by Graneheim and Lundman (2004), the researchers had an open dialogue to discuss and define the categories. Authentic quotes were used to increase trustworthiness (Elo & Kyngas, 2008). The researchers explored other sources of information to further validate findings, including the findings in the ancient yogic text Yoga Sutras of Patanjali as interpreted by B. K. S. Iyengar, one of the world’s foremost yoga teachers and author of numerous texts on yoga practice and philosophy.

Findings

Demographic characteristics of the 171 study participants are shown in Table 1. Subjects ranged in age from 23 to 80 years (M = 55.0 years, SD = 11.3), with the large majority being female (86%) and White (91.8). Most of the subjects were married or living with a partner (66.1%), and 42.6% were employed full-time. They were well educated, with over 85% having an undergraduate (38.6%), a master’s (38.6%), or a doctoral (10.5%) degree. Subjects reported practicing yoga for less than 1 to more than 25 years (M = 12.0 years, SD = 7.6).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Sample (N = 171)

| Variables | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 55.0 (11.3) | 23-80 |

| Length of yoga practice (in years) |

12.0 (7.6) | 0-25+ |

|

| ||

| Frequency | % | |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 24 | 14 |

| Female | 147 | 86 |

| Race | ||

| White | 157 | 91.8 |

| Othera | 14 | 8.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/lives with partner | 113 | 66.1 |

| Singleb/widowed/separated/ divorced |

55 | 32.2 |

| Other | 3 | 1.7 |

| Employment | ||

| Full-time | 73 | 42.6 |

| Part-time | 49 | 28.7 |

| Not employed | 49 | 28.7 |

| Education | ||

| High school/GED/trade/ vocational school/other |

7 | 4.1 |

| Some college | 14 | 8.2 |

| College graduate | 66 | 38.6 |

| Master’s degree | 66 | 38.6 |

| Doctoral degree | 18 | 10.5 |

Multiracial (n = 5; 2.9%), Asian (n = 3; 1.8%), African American (n = 3; 1.8%), Other (n = 3; 1.8%).

Never married.

The researchers abstracted 10 categories, with 8 subcategories that fell under four major themes. These themes were that yoga practice (a) leads to personal transformation, (b) increases social interaction, (c) provides coping mechanisms to weather relationship losses and difficulties, and (d) leads to spiritual transcendence. These themes gave a rich description of the experience of how the practice of yoga affects the lives of individuals who practice yoga. Themes, categories, subcategories, and exemplary statements (statements that best illustrate the category or subcategory) are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Themes, Categories, Subcategories, and Exemplar Statements

| Theme | Category | Subcategory | Exemplar Statement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yoga leads to personal transformation |

A new person | “I am a new person … I notice an improvement in my attitude, which of course makes my relationships with others better.” |

|

| More positive psychological traits |

“Yoga puts me in a better frame of mind to interact with others and deal with life in general.” |

||

| Feel better | “I am stronger, calmer, and in less pain so that improves my relationships.” |

||

| Insightful, self-aware, mindful |

“I am able to live in the moment more … I am more present with others.” |

||

| Calm, peaceful, happy, kind |

“Yoga gives me a peace and calm that helps me be better in my interpersonal relationships.” |

||

| Tolerant, respectful, compassionate |

“Yoga helps me accept people the way they are most of the time.” |

||

| Fewer negative traits | “Yoga makes me much less cranky.” | ||

| Less intolerant, judgmental |

“Because of yoga I am less judgmental and don’t expect myself and others to be perfect.” |

||

| Less reactive | “Yoga engenders a nonreactive nature; this improves relationships.” |

||

| Yoga increases social interaction |

An activity we do together | “My husband and I do yoga together.” | |

| A method of meeting people | “I met a woman at a yoga retreat who introduced me to a wonderful man and we are in love!” |

||

| A sense of community | “I love my yoga community. We are a social network of caring friends.” |

||

| Love my teacher | “I love my yoga classes and teacher.” | ||

| Decreased isolation | “I am having some very specific problems with isolation right now, but yoga helps.” |

||

| Yoga provides coping mechanisms to weather relationship difficulties and losses |

Tool for coping | “I deal with life better.” | |

| Helps with relationship difficulties |

“Yoga has saved my life and my marriage.” | ||

| Helps with loss | “My husband died and I have recently moved … I do know that yoga is the thing that keeps me feeling as good as I do. Without it I would be sad all of the time.” |

||

| Yoga leads to spiritual transcendence and connection |

Transcendence of self | “I have a great sense of purpose.” | |

| Sense of oneness/ connection to all |

“It takes me to my inner reality and feelings of oneness with others.” |

Theme 1: Yoga Leads to Personal Transformation

Three categories emerged from the data and supported the theme that yoga leads to personal transformation: Subjects had changed or become “a new person” after starting the practice of yoga; they had more positive traits; and they had fewer negative traits, all of which made their interpersonal relationships better. Participants believed that yoga had transformed their lives, and this transformation changed how they relate to others. Said one practitioner, “I have noticed an improvement in my attitude, which, of course, makes my relationships with others much better.” Practitioners reported having “more” of a number of positive psychological traits and characteristics as a result of their yoga practice: insight, self-awareness, mindfulness, calmness, peacefulness, happiness, compassion, kindness, tolerance, respect, and compassion. Participants stated that yoga puts them in a better frame of mind for interacting with others: “I feel better able to interact from a generous place after yoga and that usually lasts a few days.” Simply put by one practitioner, “I am a nice person when I do yoga!!!”

Several participants claimed their yoga practice helped them be more insightful and self-aware, which made them less reactive and more able to respond with compassion in their interpersonal relationships. Said one, “I have a greater awareness of my needs and others’ needs so my relationships are stronger.” “Getting in touch with myself definitely helps me get in touch with others,” responded another. Explained another, “Yoga helps me to be more self-aware, and thus more compassionate and empathetic. This helps me connect with others and build strong, trusting and honest relationships.” Others reported that their new-found self-awareness made them more discriminating in their relationships. A number of practitioners said they felt better physically, which in turn led to positive interpersonal experiences. One practitioner explained, “I am stronger, calmer, and in less pain so that improves my relationships.”

In addition to experiencing an increase in positive attributes, the practitioners wrote about having fewer negative traits such as being intolerant, judgmental, and reactive. As one practitioner stated, “Yoga engenders a non-reactive nature; this improves all relationships.” Another explained, “Because of yoga I am less judgmental and don’t expect myself and others to be perfect.” The theme of yoga practice leading to personal transformation that affects relationships and social health was stated simply by this practitioner, “Yoga has made me a better friend, relative, and person.”

Theme 2: Yoga Increases Social Interaction

Four categories were abstracted from the data, and these categories merged into the theme that yoga increases social interaction. These categories were that that yoga is an activity people do together, is a method of meeting people, provides a sense of community, and decreases social isolation. Taken as a whole, the categories imply an aspect of “community” to yoga practice. This theme drove home a very practical consideration: Yoga practice can increase social interaction because it is an activity that one participates in with others. Some practitioners reported attending classes with their husband, sister, or friend, and that it was an activity they enjoyed “doing” with others. Said one woman, “My husband and I do yoga together … It is the one thing that my husband and I will always be able to do together no matter what age we are.” Others reported that they had met new friends and acquaintances through the practice of yoga. Explained one practitioner, “I have found a new meaning in life, a new job (I am a yoga instructor) and a new community of friends among my peers, teachers and students.” Another enthusiastic practitioner said, “I met a woman at a yoga retreat who introduced me to a wonderful man and we are in love!”

The term community was used repeatedly by a number of practitioners: “I have both new and old friends who are not part of my yoga life—but it is the yoga community that gives me the feeling of belonging to a community.” “I love my yoga community. We are a social network of caring friends.” “My community has grown wide and deep as a result of meeting so many other people at yoga class.” Perhaps the most important relationship within the yoga community is the close bond participants felt with their yoga teacher. Many practitioners identified their teachers by name and expressed profound love and gratitude. Said one, “My yoga instructor makes a tremendous difference to me …” Another enthused, “I love my two Iyengar teachers!”

A final category that was abstracted under the theme that yoga increases social interaction was that yoga decreases feelings of social isolation. Several practitioners reported being plagued by feelings of loneliness and believed yoga helped. Said one practitioner, “I often feel isolated … yoga is one of the best parts of my life. I have started to make new friends.” Another concurred, “I am having some very specific problems with isolation right now, but yoga helps.”

Theme Three: Yoga Provides Coping Mechanisms to Weather Relationship Difficulties and Losses

One of the most poignant themes to emerge from the data was that yoga seems to provide mechanisms to weather relationship difficulties and loss. Several practitioners commented on how yoga provided tools for dealing with difficult relationships. Stated one practitioner, “Yoga seems to remove the chaos from relationships so that you can better enjoy people.” Another explained, “Yoga helps me get over anger and hurt, which helps maintain relationships.” Two different practitioners stated the exact same words, “Yoga has saved my life and my marriage.”

Yoga seems to make the tough times, including losses, more bearable. Explained one practitioner, “I’ve had to deal with an abusive spouse and subsequent divorce. I attribute my tendency to lowered feelings, anxiety, and pessimism to this. It would be worse without yoga.” Another shared how yoga helped her weather multiple stressors:

I lost my job in January and just this past month have started a new job … had to move out of my family home … into a much smaller place and I turned 60 … If I did not have yoga and meditation I would have been a nutcase.

A number of practitioners shared deeply moving accounts of how their yoga practice sustained them through significant life events and losses. Said one,

My husband died and I have recently moved so my answers about my state of mind reflect that. I do know that yoga is the thing that keeps me feeling as good as I do. Without it I would be sad all of the time.

Another stated the following:

I was able to care for my dying mother because of my study of yoga. She pointed it out to me and we spoke about it very honestly. I could NOT have coped or done what I did without being connected to my yoga “spirituality.”

As one practitioner stated succinctly, “When my husband killed himself, yoga helped me face my grief and build a new life.”

Theme 4: Yoga Leads to Spiritual Transcendence and Connection

The final theme extracted from the comments of participants was that there is a spiritual aspect of yoga that leads to a transcendence of self and a sense of connectedness to all mankind. This went beyond making new friends or feeling connected to a specific yoga community. The practitioners talked of feeling a part of something bigger and deeper that transcended individual differences. Said one practitioner, “It takes me to my inner reality and feelings of oneness with others.” Said another, “I like honoring the spirit within me, whether Jew, Christian, Muslim …” Numerous practitioners reported feeling a greater “sense of purpose.” Others expressed the idea that their practice benefitted the greater good: “Yoga and meditation/pranayama are practices and ways of living to me that I gain enormous renewal from and hope that my practice in some way contributes to others well-being as well as my own.” One woman explained,

Yoga/meditation puts humans into a “certain state.” That state has been called calm, serene, blissful, etc, etc. However, the key point is that in that state, humans are “better” human beings: less aggressive, more flexible, more creative—without any indoctrination or imposition of a philosophical system. Therefore yoga is universal and context independent.

One final participant echoed the words of many: “I’ve often thought and said, if everyone were to practice yoga, perhaps we could attain world peace.”

Validation of Findings Through Other Sources: The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

When the researchers looked to the primary text of yoga philosophy, The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, for validation of our findings, we found the same themes expressed by our participants. Thousands of years ago, the yoga sage Patanjali codified yogic philosophy into 196 aphorisms or “sutras” that detail how yoga practice can be used to overcome life’s obstacles in order to achieve spiritual development. Only 2 of the 196 sutras or aphorisms pertain to the physical practice of yoga. The remaining 194 sutras define and painstakingly detail the practice of yoga and the effects of the practice on the individual’s body, mind, and spirit. That yoga provided a tool for overcoming obstacles and that it leads to spiritual development were themes that emerged in our participants’ comments. Just as many of our study participants commented on how yoga had changed their minds for the better, the majority of Patanjali’s yoga sutras describe how fluctuations of the mind lead to suffering and how yoga can be used to control these fluctuations. The second sutra states, “Yoga is a cessation of the movements in the consciousness” (Iyengar, 1993, p. 46). After stilling the mind’s endless stream of thoughts, worries, and distractions through yoga practice, these negative states of mind can no longer “distort the true expression of the soul” (p. 48).

Some of the sutras seem to refer specifically to how yoga practice changes one’s interpersonal relationships. Sutra 1.33 echoes comments of practitioners that yoga practice leads to a personal transformation, whereby one becomes more content, more friendly, and less judgmental: “Through cultivation of friendliness, compassion, joy, and indifference to pleasure and pain, virtue and vice respectively, the consciousness becomes favorably disposed, serene, and benevolent” (Iyengar, 1993, p. 82). A number of sutras refer specifically to how yoga helps one overcome life’s obstacles and afflictions, leading to a state of Samadhi, described as “an experience where the existence of ‘I’ disappears … we truly understand at the core of our being that our individual soul is part of the Universal Soul” (Iyengar, 2005, p. 215). This sutra parallels the final theme identified in the study that yoga leads to a transcendence of self and a sense of connection with all mankind.

Conclusion and Implications

In examining the comments made by the 171 yoga practitioners, four major themes emerged regarding the social benefits of yoga practice. First, a large number of practitioners believed that yoga practice led to a personal transformation that in turn benefitted their relationships with others. Second, practitioners reported that yoga was a social activity that they could do with others and that often resulted in new friendships and relationships. Subjects also reported a sense of closeness to their yoga teachers, a relationship they valued. A third theme was that yoga helped them weather life’s difficulties, including loneliness and loss. A final theme that emerged from the comments was that yoga leads to a spiritual transcendence of self. It leads to a deep connection with themselves and others that they believe benefits the greater good. These themes were validated by two separate investigators and confirmed by examining the ancient Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

These findings provide support for the biopsychosocial model of yoga and health proposed in this article by providing preliminary evidence that there may be social benefits of yoga practice that include the importance of one’s relationship to one’s yoga teacher and to one’s yoga community. These findings reveal a number of implications for holistic nursing practice. Because social support is an important predictor of morbidity and mortality (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Patterson & Veenstra, 2010) and yoga practice might contribute to social support, yoga could be beneficial for populations at risk for social isolation, such as those who are elderly, bereaved, and depressed. Yoga also may provide an outlet for individuals undergoing life transitions that involve upheaval, such as those who have recently moved, changed jobs, or had other life transitions. Individuals recovering from the emotional effects of abuse, dysfunctional relationships, or divorce may find a sense of strength and self-efficacy through the practice of yoga. Finally, if yoga truly helps individuals reframe negative mind states, it might possibly provide benefits similar to cognitive-behavioral therapy, thus making it a useful intervention for holistic nurses working in psychiatric mental health nursing.

Holistic nurses who want to recommend yoga for their patients should be aware that the large majority of yoga practitioners in the United States are White, college-educated women, and minority populations might have reservations about trying yoga (Ross, Friedmann, Bevans, & Thomas, 2013; Saper, Eisenberg, Davis, Culpepper, & Phillips, 2004). Offering yoga classes in an atmosphere where the patients feel comfortable and familiar, such as a church or a local community center or clinic, with an instructor of the same ethnic/racial background might make the classes more acceptable. Holistic nurses also should be aware that there are a number of different styles of yoga, and each places a slightly different emphasis on the various aspects of yoga practice (physical poses, breath work, meditation, and the study of yoga philosophy). Some styles such as Vinyasa, Ashtanga, or Bikram are physically demanding, with Bikram classes taught in hot (105 °F), humidified rooms. Others focus less on the physical practice and more on quiet, restorative poses and breath work. This study focused on practitioners of the Iyengar style, which emphasizes all aspects of yoga practice (physical poses, breath work, meditation, and philosophy study), although beginning-level students focus primarily on physical poses, which might make it appealing to students who are less comfortable with the spiritual aspects of yoga.

It should be noted that the Iyengar yoga studios sampled here typically offer classes in sessions, averaging 6 to 12 weeks in duration. Unlike many yoga studios that allow individuals to sign up for a “package” of classes, then switch from class to class with different teachers, students in this study tended to remain in the same class with the same teacher for many weeks (or years). Although it makes intuitive sense that a system such as this that encourages an ongoing relationship with a teacher and cohort of peers might lead one to feel closer to one’s teacher and peers (and thus experience more benefits to one’s social health), research is needed to confirm this assumption.

There are some limitations inherent in this study. First, the data analyzed qualitatively here were collected from comments made in a much larger quantitative study examining the relationship between yoga practice and health. Thus, the questions asked may have lacked enough depth to adequately capture the full experience of the social benefits of yoga. Because the study used a cross-sectional design and focused exclusively on Iyengar yoga practitioners, it is impossible to draw any definitive conclusions about the social benefits of yoga practice in general. It also is possible that individuals might benefit socially from any group experience; thus the benefits are not unique to yoga. Randomized clinical trials are needed to examine whether research outcomes such as social support, loneliness, depression, self-esteem, optimism, and spirituality improve more using a group yoga intervention versus another group intervention such as aerobic exercise. Comparable effectiveness studies are needed to examine the unique benefits of the different styles of yoga.

Despite the limitations, clear themes emerged suggesting that yoga provides not only a platform for social interaction but also a toolbox for weathering relationship difficulties and losses. If these findings are an accurate reflection of the subjects’ experiences, yoga could be a useful intervention for a number of at-risk populations. There appears to be an aspect of community associated with yoga practice that is both practical (a way to meet new friends) and spiritual (a way to feel connected to something larger than oneself), and this aspect of community may be beneficial to one’s mental, physical, social, and spiritual health and merits further exploration.

Biographies

Alyson Ross, PhD, RN is an Assistant Professor of Nursing at the University of Maryland School of Nursing and a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the NIH Clinical Center. Her research focuses on the relationship between stress and health behaviors, and the impact of mind-body techniques such as yoga to reduce stress and improve health.

Margaret Bevans PhD, RN, is a Clinical Nurse Scientist at the NIH Clinical Center. The focus of her research is to improve the psychosocial outcomes of cancer patients and their family caregivers.

Erika Friedmann, PhD is a professor at the University of Maryland School of Nursing. Her research addresses the integration of social, psychological, and physiological contributors to health.

Laurie Williams, MA, is a health coach and Director of Wellness Programs at the Casey Health Institute, an integrative medicine patient-centered medical home serving the greater Washington, DC area.

Sue Thomas, PhD, RN, FAAN is an expert on psychological and social influences affecting health. Her research over the past 30 years focuses on the effects of depression, anxiety and social support on cardiovascular health.

Contributor Information

Alyson Ross, University of Maryland School of Nursing.

Margaret Bevans, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center.

Erika Friedmann, University of Maryland School of Nursing.

Laurie Williams, Casey Health Institute.

Sue Thomas, University of Maryland School of Nursing.

References

- Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg B. Content analysis. In: Berg B, editor. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA: 1998. pp. 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Brummett B, Barefoot J, Siegler I, Clapp-Channing N, Lytle B, Bosworth H, Mark DB. Characteristics of socially isolated patients with coronary artery disease who are at elevated risk for mortality. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63:267–272. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant EF. The yoga sutras of Patanjali. 1st ed. North Point Press; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing A, Michalsen A, Khalsa SBS, Telles S, Sherman KJ. Effects of yoga on mental and physical health: A short summary of reviews. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/165410. Retrieved from http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2012/165410/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Büssing A, Ostermann T, Lüdtke R, Michalsen A. Effects of yoga interventions on pain and pain-associated disability: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pain. 2012;13:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culos-Reed SN, MacKenzie MJ, Sohl SJ, Jesse MT, Zahavich ANR, Danhauer SC. Yoga & cancer interventions: A review of the clinical significance of patient reported outcomes for cancer survivors. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/642576. Retrieved from http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2012/642576/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dush CMK, Amato PR. Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:607–627. [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson P, Kaplan C. Maximizing qualitative responses about smoking in structured interviews. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10:829–840. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geer J. What do open-ended questions measure? Public Opinion Quarterly. 1988;52:365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant N, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Social isolation and stress-related cardiovascular, lipid, and cortisol responses. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;37:29–37. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MA, Driscoll JM. Health promotion and disease prevention: A concentric biopsychosocial model of health status. In: Brown S, editor. Handbook of counseling psychology. 3rd ed. John Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2000. pp. 532–367. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lundstad J, Smith T, Layton J. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. Retrieved from http://www.plos-medicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innes K, Bourguignon C, Taylor A. Risk indices associated with the insulin resistance syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and possible protection with yoga: A systematic review. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18:491–519. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.6.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar BKS. The tree of yoga. Shambala; Boston, MA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar BKS. Light on the yoga sutras of Patanjali. Vol. 1. Thorsons; London, England: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar BKS. B. K. S. Iyengar yoga: The path to holistic health. Vol. 1. Dorling Kindersley; London, England: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar BKS. Light on life: The yoga journey to wholeness, inner peace, and ultimate freedom. Rodale; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin JP, Hantsoo L. Close relationships, inflammation, and health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;35:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Tuffrey V, Richardson J, Pilkington K. Yoga for anxiety: A systematic review of the research evidence. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39:884–891. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki NL, Wellman NS, Amundson DR. Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2002;34:224–230. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer HB, Katsman A, Sones AC, Auerbach DE, Ames D, Rubin RT. Yoga as an ancillary treatment for neurological and psychiatric disorders:A review. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2012;24:152–164. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11040090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina JA. Understanding the biopsychosocial model. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1983;13:29–36. doi: 10.2190/0uhq-bxne-6ggy-n1tf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson AC, Veenstra G. Loneliness and risk of mortality: A longitudinal investigation in Alameda County, California. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posadzki P, Ernst E. Yoga for asthma? A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Asthma. 2011;48:632–639. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.584358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A, Friedmann E, Bevans M, Thomas S. Frequency of yoga practice predicts health: Results of a national survey of yoga practitioners. Journal of Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;(10) doi: 10.1155/2012/983258. 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/983258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A, Friedmann E, Bevans M, Thomas S. National survey of yoga practitioners: Mental and physical health benefits. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2013;21:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A, Thomas S. The health benefits of yoga and exercise: A review of comparison studies. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2010;16:3–12. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Culpepper L, Phillips RS. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the United States: Results of a national survey. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2004;10:44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telles S, Singh N, Balkrishna A. Managing mental health disorders resulting from trauma through yoga: A review. Depression Research and Treatment, 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/401513. Retrieved from http://www.hindawi.com/journals/drt/2012/401513/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Uebelacker LA, Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano BA, Tremont G, Battle CL, Miller IW. Hatha yoga for depression: Critical review of the evidence for efficacy, plausible mechanisms of action, and directions for future research. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2010;16:22–33. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000367775.88388.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Montez J. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(Suppl.):S54–S66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]