Abstract

Context:

Abnormalities in nuclear morphology are very frequently seen in dysplasia, such as nuclear area, diameter, shape, number of nucleoli and membrane outline. The purpose of this study was to observe and compare the nuclear features in different grades of epithelial dysplasia in leukoplakia and to evaluate the use of Feulgen stain for observing the nuclear features in oral epithelial dysplasia in leukoplakia. Seventy paraffin embedded tissue section (20 mild, 20 moderate, 20 severe dysplasia cases and 10 control specimens) were analyzed for nuclear morphology using Feulgen stain under trinocular research microscope. Statistically significant results were obtained with P > 0.001, when intergroup comparison was done except in case of nuclear area and diameter between mild and moderate dysplasia. Nuclear features reflect cell's biological potential and its morphometry was found to be a useful tool for differentiating different grades of dysplasia.

Keywords: Feulgen staining, nuclear morphometry, oral epithelial dysplasia

INTRODUCTION

Presently “Oral Cancer” has become synonymous with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). It is the most common malignant tumors of the oral cavity and oropharynx. It is strongly correlated with specific risk factors, such as tobacco and alcohol use which cause genetic damage leading to uncontrolled proliferation of these cells resulting in dysplasia and presents as precancer and cancer.[1]

Oral leukoplakia represents the most common potentially malignant disorder of the oral cavity. Worldwide prevalence of leukoplakia is 0.2 to 4.9% and the overall malignant transformation rates for dysplastic lesions range from 3 to 6%, depending on the type, site and length of follow-up.[2,3] This wide variation is due to the fact that certain clinical subtypes of leukoplakia are at higher risk of malignant transformation than others.[4] The presence of epithelial dysplasia histopathologically may be even more important in predicting malignant potential than the clinical characteristics.

Although interobserver and intraobserver variability still exists, histopathological assessment of severity of oral epithelial dysplasia (OED) is considered as the “gold standard” for the prediction of malignant transformation of precancerous lesions. From the vast literature on molecular markers in oral precancer, reliable prognostic markers still remains inconclusive therefore, a substantial need still exists to improve the histologic assessment of epithelial dysplasia.[5,6]

Conventionally OEDs have been studied extensively (based on the subjective evaluation of various nuclear and cytoplasmic features within the lesional tissue) at the histological level. Recently, interest has turned towards sophisticated technique of computer assisted morphometry to investigate the cellular and nuclear changes in correlation with the histological behavior of these lesions.[7] Morphometry as an essential tool in the field of biology and medical research provides improved and quantitative approach for assessing structural changes in lesional tissues and the results are found to be more reliable, objective and reproducible.[8,9]

Our objective was to observe the nuclear features in normal mucosa and to compare with that of different histological grades of OED and to evaluate the use of Feulgen stain for staining and observing the nuclear features in oral epithelial dysplasia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted on 60 cases of leukoplakia retrieved from the archives of Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology and 10 normal oral mucosal specimens from healthy adult individuals with no relevant habits obtained with their consent, served as control.

The study group comprised of clinically diagnosed cases of leukoplakia irrespective of age and sex, confirmed histologically as epithelial dysplasia based on World Health Organization (WHO) grading of epithelial dysplasia 1997.

The study and control groups were

Group-I (n = 10): Control group which consisted of apparently normal mucosa

Group-II (n = 20): Mild epithelial dysplasia

Group-III (n = 20): Moderate epithelial dysplasia and

Group-IV (n = 20): Severe epithelial dysplasia.

5 μm thick sections were obtained from all the groups and were stained with Feulgen stain.[10,11]

Principle

Mild acid hydrolysis, using 1M hydrochloric acid at 600 C, is used to break the purine-deoxyribose bond. The resulting exposed aldehydes are then demonstrated by Schiff's reagent.

This reaction allows a very precise localization of DNA since, after purine bases have been removed, deoxyribose radicals are bound to phosphoric acid of apurinic acid macromolecule. The technique followed was considered to be correct on 2 conditions: (1) after acid hydrolysis, Schiff's reagent succeeds in staining the specimen; (2) Schiff's reagent does not succeed in staining a control section which has not undergone hydrolysis.

Staining method

Sections were brought to water through xylene and ethanol. It was then rinsed with 1N HCl at room temperature followed by incubation for appropriate time in HCl at 60°C. Sections were then rinsed with 1 N HCl at room temperature followed by distilled water. It was placed in Schiff's reagent for 30-60 minutes at room temperature followed by three times wash with potassium meta-bi-sulphite for 1 minute each. Sections thus stained are washed with water and counter-stained with light green for a minute. Finally it was dehydrated with ethanol followed by xylene and mounted with a resinous membrane.

DNA = red and Background = green.

Feulgen stain is specific to nucleus, it can readily demonstrate nuclear morphometric features additionally, micronuclei, nucleoli, nuclear shape and outline can be appreciated very well.

The stained sections were then observed under trinocular research microscope using 40X apochromatic objective (numerical aperture 0.07) by two examiners.

For each case, 10 microscopic fields were selected randomly, commencing with the first representative field on the left hand side of the section being measured, moving the stage to the next field. Images were captured and stored in computer using 3 chip CCD camera (Proview, Media cybernetics, USA) and Imaging software (Image Pro Plus, Version 4.1.0.0 for Windows 95/NT/98, Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, USA, accurately calibrated using a stage micrometer where 1 micron was equal to 3.260 pixels) was used for further analysis.

100 nuclei in parabasal and spinous cell layers were examined. Care was taken to only include randomly selected cells from the lower third of the epithelium, which showed complete, non overlapping outline.

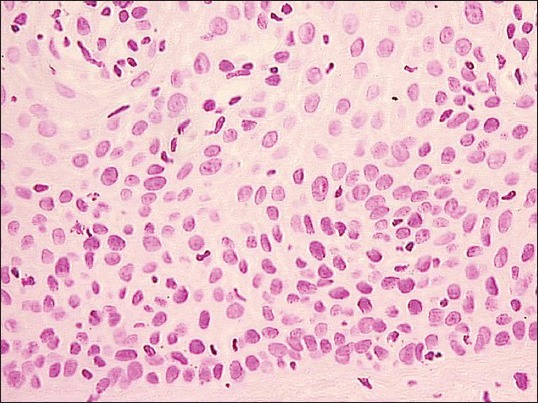

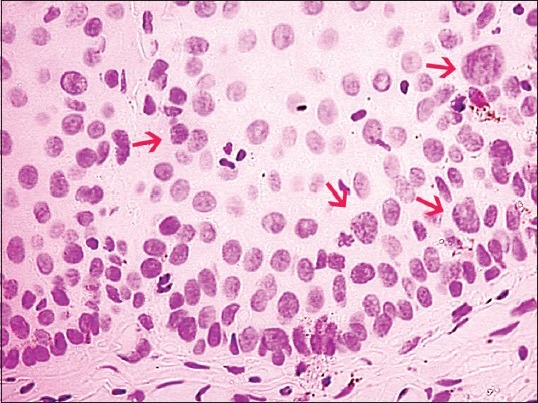

Morphometry for each nucleus was done after opening the image in software and each nuclear outline was traced with the cursor without lifting the pointer once started till circle completed; the software computes the area. For diameter two straight lines were drawn across nucleus and its average was taken. Nuclear shape, membrane outline and number of nuclei were noted accordingly in a separate excel sheet for each cell [Table 1, Figures 1–6].

Table 1.

Various morphometry values being recorded

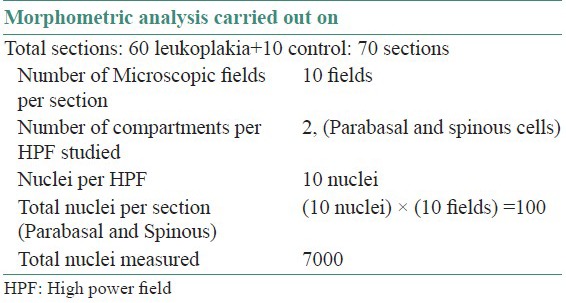

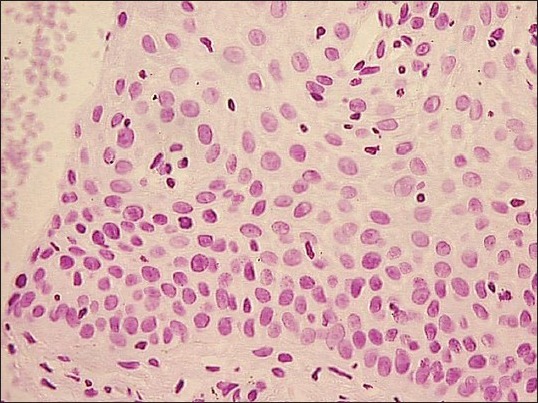

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph showing Feulgen stained nuclei of normal oral mucosa (Feulgen stain, ×200)

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph showing morphometic measurements on Feulgen stained nuclei. (Feulgen stain, ×400)

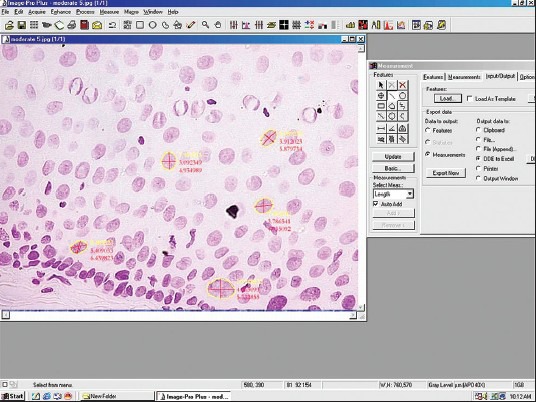

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing Feulgen stained nuclei of mild dysplastic oral mucosa (Feulgen stain, ×200)

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph showing Feulgen stained nuclei of moderately dysplastic oral mucosa (Feulgen stain, ×200)

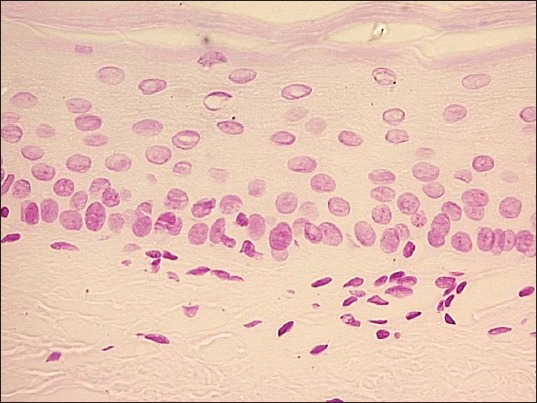

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph showing Feulgen stained nuclei of severely dysplastic oral mucosa (Feulgen stain, ×200)

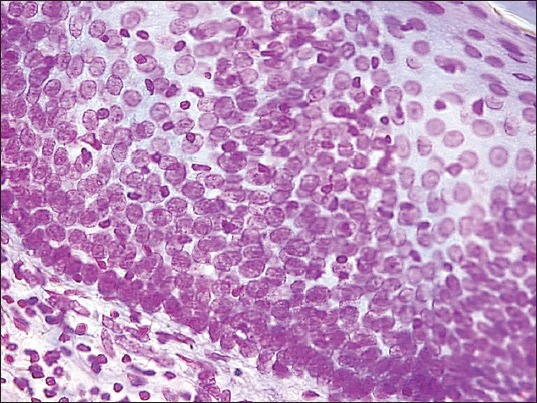

Figure 5.

Photomicrograph showing Feulgen stained nuclei with variation in its shape, membrane outline and number of nuclei (Feulgen stain, ×200)

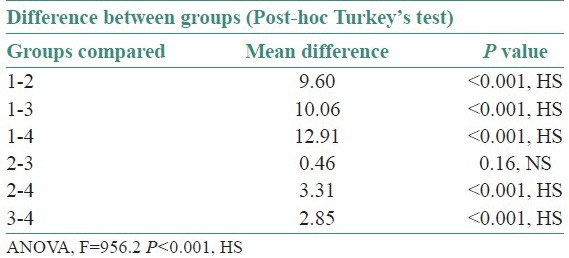

The obtained data was analyzed statistically by computing descriptive statistics, viz., percentage, mean, standard deviation and standard error of mean. Ninety-five percent confidence interval (CI) for mean values was obtained in microns for various morphometric variables. The differences in the various groups for different parameters were compared by means of one way analysis of variance (ANOVA, F-test) and Chi-square test. Post-hoc Turkey's test was done for intra group variation. P value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

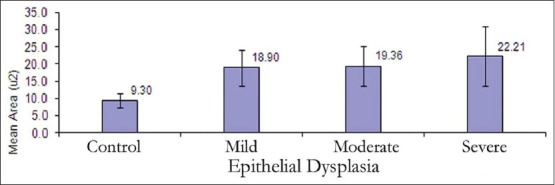

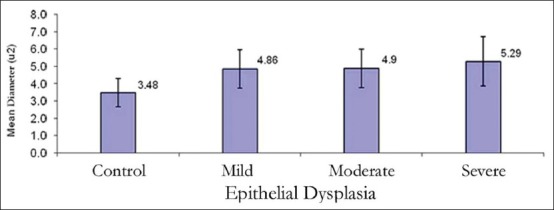

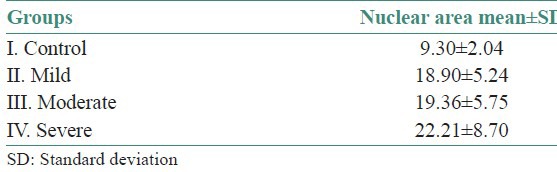

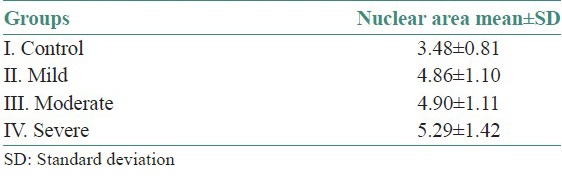

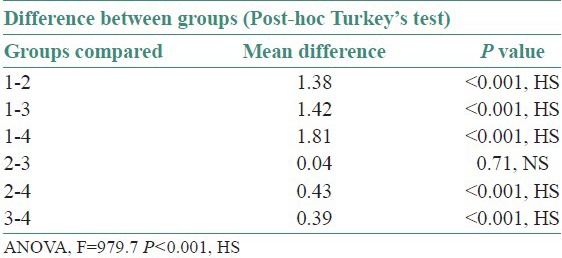

The mean nuclear area (NA) and mean nuclear diameter (ND) were found to be increased from normal mucosa to dysplasia and also within dysplasia as the grade of dysplasia increased. But, statistically significant difference was not observed between NA and ND between mild and moderate OED [Figures 7 and 8, Tables 2 and 3].

Figure 7.

Mean nuclear area in control and various dysplastic groups in the study

Figure 8.

Mean nuclear diameter in control and various dysplastic groups in the study

Table 2a.

Nuclear area mean

Table 3a.

Nuclear diameter mean

Table 2b.

Intergroup comparison of nuclear area among study groups

Table 3b.

Intergroup comparison of nuclear diameter among study groups

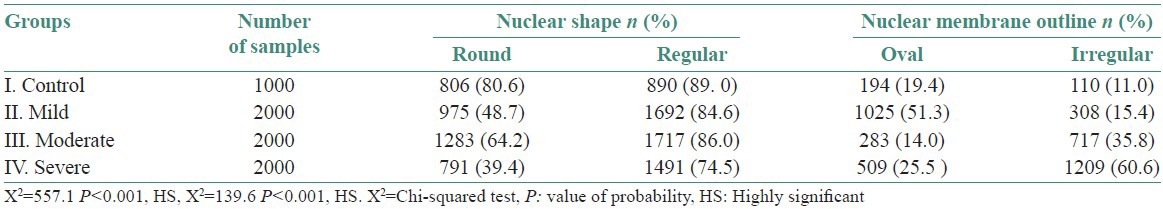

It was found that most of the nuclei in normal mucosa were round shaped and had regular membrane outlines, whereas it increasingly became oval and irregular as the grade of dysplasia increased except in case of moderate dysplasia. While the nuclei of normal mucosa showed least amount of changes in relation to NS and nuclear membrane outline (NMO) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Mean and standard deviation of nuclear shape and membrane outline in various study groups (mean±SD)

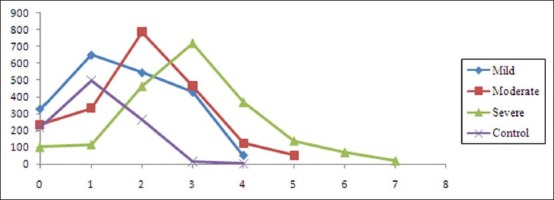

Number of nucleoli increased and became prominent as grades of dysplasia increased, also frequent abnormal mitotic figures were observed.

In mild, moderate and severe dysplastic groups nucleoli showed predominantly 1, 2 and 3 nucleoli, but ranged from 0 to 4, 5 and 7 nucleoli in a nucleus of their respective groups [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Incidence and number of nuclei in control and various dysplastic groups in the study

DISCUSSION

Oral leukoplakia represents the most common potentially malignant disorder of the oral cavity. Many investigators have evaluated the use of nuclear and cytoplasmic morphometry for grading and for predicting prognosis in esophageal, laryngeal and oral cancers.[12,13] Attempts have also been made to apply morphometry to normal oral epithelium and also in various oral mucosal diseases like oral submucous fibrosis, lichen planus, epithelial dysplasia and traumatic keratosis.[14,15,16,17]

Robert Feulgen and Rossenbeck described the specific staining technique for nuclear DNA to be based on the reaction of Schiff's or Schiff-like reagents with aldehyde groups engendered in the deoxyribose molecules by HCl hydrolysis. The staining intensity is proportional to the DNA concentration. In this protocol, hydrolysis is the critical step, an increasingly stronger reaction is obtained, till the optimum staining is acheived, beyond which staining becomes weaker and if the hydrolysis is continued the reaction may completely fail.[10]

Saku and Sato[18] reported an increase in the proportion of the cells in the hyperdiploid to the hypertetraploid range in oral leukoplakia. In our study, the NA was almost twice as large in leukoplakia compared to the normal mucosa. ND increased gradually with increasing histological grades of OED compared to control group. Our study has similar results as previous studies.[12,13,14,15,16,17,18] Statistically significant difference was observed when mean NA and ND of various study groups was compared, except between mild and moderate dysplasia. This we believe could be because few of dysplastic cells present in mild and moderate dysplasia were overlapping, that is cells of mild OED were in advance stage and cells of moderate OED were a step behind in maturation or due to sectioning artifact. Hence a two tier grading system possibly yields better statistically significant result.[19]

We found that round shaped nucleus was seen chiefly in control group and oval shape in dysplastic cells and the number of oval nucleus were increasing in different histological grades of OED. Variation in nuclear shape is a distinctive feature of malignancy. Lowest levels of dysplasia are characterized by spherical nuclei of approximately equal size and highest grade tumors are characterized by profound anisonucleosis.[19,20] It is often the result of rapid rate of growth of the neoplastic cells, due to abnormal mitoses producing an irregularity of the chromatin or the number and shape of the chromosomes. However the grading of dysplasia cannot be based on the chromatin pattern alone, for example the variation of the shape of the nucleus can occur in dysplastic cells also seen as a distortion resulting from poor cellular fixation, trauma, degeneration, cautery or hormonal changes, but such cells have other degenerative changes. A tangential section of the epithelium may also result in an elongated nuclear shape. As such by itself, irregularity in nuclear shape, if not extreme, is not sufficient for diagnosis in most tumors.[19,21,22,23,24,25]

Regular NMO was found predominantly in control group, while it was irregular in mild, moderate and severe groups. This finding was in agreement with earlier workers who had considered that increase in nuclear membrane irregularities increased with increasing grades of dysplasia.[21,22,23] The irregularity of the nuclear membrane (indentation, lobulation, protrusion or extensive wrinkling) is considered important in diagnosis and grading of malignancy. Wrinkling is the result of rapid and abnormal growth of cells. The irregularity of NMO is often the result of adhesion of some of the abnormal chromatin clumps to the inner surface. The contours of the nuclear membrane in malignant cells are sharp and well-defined which differentiates them from the irregularity resulting from cellular degeneration.

Statistically significant difference was observed when nucleoli were compared in various groups, group II, group III and group IV.

Nucleoli increased in number and became prominent with increasing grades of dysplasia with frequent abnormal mitotic figures, while in normal mucosa, few nuclei had inconspicuous nucleolus. Mild, moderate and severe dysplastic groups showed predominantly 1, 2 and 3 nucleoli however few nuclei in respective groups also exhibited 4, 5 and 7 nucleoli.[21,24]

Feulgen reaction is a reliable and specific histochemical method for nuclear DNA.[25,26] Doyle and Manfold[27] in 1975 did not find much use for Feulgen reaction in predicting the transformation of oral leukoplakia to OSCC. However, in this study, we found that Feulgen reaction performed carefully under controlled conditions gives a reasonably good staining and accurate quantitative histochemical estimation of nuclear DNA. Similar observations were made by Abdel-Salam et al. and Nandini and Subramanyam. Based on findings of this study, we found Feulgen stain to be a useful nuclear stain in examining and comparing dysplastic nuclear changes and hence observing dysplastic changes of a cell.

Nuclear morphometry can be also done using more sophisticated advanced instruments known as a microdensitometer or microspectrophotometer to actually measure the intensity of the pink color of Feulgen reaction (amount of DNA). Using this procedure, we can determine ploidy status of any given nucleus.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, nuclear morphology reflects the cell's biological potential and proliferative activity. Though, staining with Hematoxylin and Eosin is the gold standard in identifying and grading epithelial dysplasia, which is also time saving, nuclear morphometry with the use of Feulgen stain forms a reliable and reproducible tool that provides an opportunity to quantify the nuclear changes associated with dysplasia and affords an objective basis for grading dysplasia to predict their malignant potential. No single morphologic change in the nucleus is diagnostic by itself. Hence, a combination of several nuclear characteristics provides a better indication of the dysplastic behavior. However the number of nucleoli could be an important indicator and should be further examined for their use as an important marker of dysplasia and malignancy. The size, shape and morphology of the multiple nucleoli might also be worthwhile to study.

Overall, our results showed that the quantitative histomorphometric techniques can detect features that may be overlooked by routine histological examination.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scully C. Oncogenes, onco-suppressors, carcinogenesis and oral cancer. Br Dent J. 1992;173:53–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta FS, Gupta PC, Daftary DK, Pindbourg JJ, Choksi SK. An epidemiological study of oral cancer and precancerous conditions among 101,761 villagers in Maharashtra, India. Int J Cancer. 1972;10:134–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910100118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright J, O’Brien JC. Boca Raton: CRC Press Inc; 1988. Premalignancy, Oral Cancer: Clinical and Pathological Considerations; pp. 45–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajendran R, Sivapathasundharam B. Benign and malignant tumors of the oral cavity. In: Rajendran R, Sivapathasundharam B, editors. Shafer's Text book of oral pathology. 5th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 121–30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel FL, Fava M, Hoffmann RR, Campos MM, Yurgel LS. Main molecular markers of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Appl Cancer Res. 2010;30:279–88. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kujan O, Oliver RJ, Kattab A, Roberts SA, Thakker N, Sloan P. Evaluation of new binary system of grading oral epithelial dysplasia for prediction of malignant transformation. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:987–93. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shabana AH, Labban NG, Lee KW. Morphometric analysis of basal cell layer in oral premalignant white lesions and squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:454–8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.40.4.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smitha T, Sharada P, Girish HC. Morphometry of the basal cell layer of oral leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma using computer-aided image analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:26–33. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.80034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remmerbach TW, Weidenbach H, Pomjanski N, Knops K, Mathes S, Hemprich A, et al. Cytologic and DNA-cytometric in early diagnosis of oral cancer. Anal Cell Pathol. 2001;22:211–21. doi: 10.1155/2001/807358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bancroft JD. Proteins and nucleic acids. In: Bancroft JD, Stevens A, editors. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 4th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. pp. 237–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drury RA, Wallington EA. 5th ed. London: Oxford University Press; 1980. Carleton's histological technique; pp. 160–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Salam M, Mayall BH, Chew K, Silverman S, Greenspan JS. Prediction of malignant transformation in oral epithelial lesions by image cytometry. Cancer. 1988;62:1981–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881101)62:9<1981::aid-cncr2820620918>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuzawa S, Hashimura T, Sasaki M, Yamabe H, Yoshida O. Nuclear morphometry for improved predilection of the prognosis of human bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1790–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951115)76:10<1790::aid-cncr2820761017>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao S, Liu S, Shen Z, Peng L. Morphometric analysis of spinous cell in oral submucous fibrosis. Comparison with normal mucosa, leukoplakia and squamous cell carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl) 1995;108:351–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramaesh T, Mendis BR, Ratnatunga N, Thattil RO. Cytomorphotometric analysis of squames obtained from normal oral mucosa and lesions of oral leukoplakia and squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:83–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramaesh T, Mendis BR, Ratnatunga N, Thattil RO. Diagnosis of oral premalignant and malignant lesions using cytomorphometry. Odontostomatol Trop. 1999;22:23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truelson JM, Fisher SG, Beals TE, McClatchey KD, Wolf GT. DNA content and histologic growth pattern correlate with prognosis in patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. The Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. Cancer. 1992;70:56–62. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1<56::aid-cncr2820700110>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saku T, Sato E. Prediction of malignant change in oral precancerous lesions by DNA cytofluorometry. J Oral Pathol. 1983;12:90–102. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nandini DB, Subramanyam RV. Nuclear features in oral squamous cell carcinoma: A computer-assisted microscopic study. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:177–81. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.84488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francois C, Decaestecker C, Petein M, van Ham P, Peltier A, Pastees JL, et al. Classification strategies for the grading of renal cell carcinomas, based on nuclear morphometry and densitometry. J Pathol. 1997;183:141–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199710)183:2<141::AID-PATH916>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuhrman SA, Lasky LC, Limas C. Prognostic significance of morphologic parameters in renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6:655–63. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagoe R, Sowter C, Slavin G. Shape and texture analysis of liver cell nuclei in hepatomas by computer aided microscopy. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:755–62. doi: 10.1136/jcp.37.7.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skinner DG, Colvin RB, Vermillion CD, Pfister RC, Leadbetter WF. Diagnosis and management of renal cell carcinoma. A clinical and pathologic study of 309 cases. Cancer. 1971;28:1165–77. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1971)28:5<1165::aid-cncr2820280513>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanigan D, Conroy R, Barry-Walsh C, Loftus B, Royston D, Leader M. A comparative analysis of grading systems in renal cell adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 1994;24:473–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Culling CF, Allision RT, Barr WT. 4th ed. London: Butterworth and co-publisher; Demonstration methods. Cellular pathology technique; pp. 183–93. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheehan DC, Barahara B. 2nd ed. 1980. Nuclear and cytoplasmic stain. Theory and Practice of Histotechnology; pp. 137–59. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doyle JL, Manhold JH., Jr Feulgen microspectrophotometry of oral cancer and leukoplakia. J Dent Res. 1975;56:1196–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345750540061601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]