Abstract

Background

Presently, the unambiguous diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo (BPPV) requires the detection of positioning or positional nystagmus provoked by Dix–Hallpike (for vertical semicircular canals) or supine roll (for horizontal semicircular canals) manoeuvres, which indicates canalo- or cupolithiasis of affected semicircular canals. There are patients, however, in whom—despite typical complaints of BPPV—no positional nystagmus can be documented; this is called ‘subjective BPPV’ (sBPPV). These patients usually complain of short vertigo spells during and after sitting up, sometimes with abnormal retropulsion of the trunk.

Aim

In this study, the authors aimed to ascertain whether these patients in fact demonstrate abnormal sitting-up trunk oscillations when measured by posturography. Of 200 unselected patients with vertigo or dizziness, 43% had sBPPV with vertigo spells while sitting up, and 20% classical BPPV.

Methods

Posturographic recordings were performed in 20 patients with sBPPV and sitting-up vertigo.

Results and discussion

Seven of the 20 patients had trunk oscillations during the act of sitting up and for a short time immediately afterwards. Based on their findings, the authors propose a new type of BPPV, the so-called Type 2 BPPV (typical complaints of BPPV, no nystagmus in Dix–Hallpike positions but short vertigo spell while sitting up), which may be the result of chronic canalolithiasis within the short arm of a posterior canal. Furthermore, the authors suggest that Type 2 BPPV, which could be identical to sBPPV or constitute a major subgroup of it, occurs frequently among patients with vertigo. For therapy, the authors recommend repetitive sit-ups from the Dix–Hallpike positions to liberate the short arm of the posterior canal from canaloliths.

INTRODUCTION

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common neuro-otological disorder.1–6 Presently, the definition of BPPV requires vertical-torsional positional nystagmus evoked by the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre or predominantly horizontal positional nystagmus after rolling the head sideways from the supine position.7–9 The former nystagmus indicates canalo- or cupulolithiasis of posterior or rarely anterior semicircular canals, while the latter nystagmus is seen in canalo- or cupulolithiasis of the horizontal canals.

Neuro-otologists regularly see patients with typical complaints of BPPV, but without positioning nystagmus, even with repeated provocatory manoeuvres. Cases with BPPV symptoms without positioning nystagmus have been termed ‘subjective BPPV’ (sBPPV). The fact that repositioning manoeuvres are effective in patients with sBPPV supports the notion that sBPPV, like classical BPPV, is caused by floating particles within the inner ear.10–12 From the literature, one might have the impression that the so far elusive disorder of sBPPV is a curiosity and affects only few patients with BPPV symptoms.

The first author of this paper (BB), who is running a vertigo/dizziness clinic at the General Hospital in Krems, Austria, noted that patients with sBPPV constitute a larger proportion of patients than previously thought. A coauthor of this paper (DS), who is running a similar clinic at the University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, had the same impression. Unlike patients with classical BPPV, patients with sBPPV rarely complain of vertigo in the Dix–Hallpike position, but do experience short vertigo spells during the act of sitting up and for a short time immediately afterwards and sometimes also have abnormal antero- and retropulsion, that is oscillation, of the trunk. Moreover, we noted that sitting-up vertigo is typically unilateral, that is it occurs after the right or left Dix–Hallpike position, which excludes other mechanisms such as orthostatic dysregulation, changes in intracranial pressure or increased motion sensitivity.

These observations prompted us to investigate the frequency of sBPPV among patients with dizziness or vertigo and describe the clinical features. In addition, in a representative sample of sBPPV patients, we monitored routine clinical positioning manoeuvres by a posturographic table. Specifically, we asked whether patients with sBPPV show increased body sway while sitting up from the Dix–Hallpike position.

METHODS

Frequency of BPPV subtypes

Records of 200 consecutive patients who visited the vertigo/dizziness ambulance at Krems General Hospital, Austria, during the period from January to March 2008 were analysed. Since most patients had to wait approximately 3–5 months for the appointment, complaints of dizziness/vertigo were generally chronic. The group of patients with benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo (BPPV) was separated into three subtypes:

Type 1 BPPV: patients with classical BPPV;

Type 2 BPPV: patients with sBPPV and short vertigo spells while sitting up;

sBPPV other than Type 2 BPPV.

Patients were diagnosed as having Type 1 BPPV (=classical BPPV), if the following two criteria were met:

typical complaints of BPPV (short vertigo when bending forward, lying down, sitting up or turning over in bed);

typical nystagmus provoked by Dix–Hallpike or supine roll manoeuvres to either side (as described in Aw et al9).

Patients were assigned to the Type 2 BPPV group, if the following three criteria were met:

typical complaints of BPPV (see above);

no nystagmus evoked by Dix–Hallpike and supine roll manoeuvres;

short spell of vertigo while sitting up from either or both Dix–Hallpike positions.

The criteria for diagnosing Ménière’s disease included pathologically elevated ratios of summating potential and action potential (SP/AP) measured by non-invasive electrochleography as reported elsewhere (Audiol Neurootol, accepted for publication). The diagnosis of vestibular migraine required normal SP/AP ratio measured by non-invasive electrocochleography and reduction of vertigo episodes under prophylactic treatment (eg, propranolol, lamotrigine, topiramate).

Posturography

Subjects

Twenty patients with Type 2 BPPV (11 females; average age: 63 years±11 SD) and nine age-matched healthy human subjects were tested after they gave their informed consent. Permission from the local ethical review board was obtained. The patients, apart from signs and symptoms related to Type 2 BPPV, were neuro-otologically normal (no spontaneous nystagmus, no head-shaking nystagmus, normal bedside head impulse testing and normal hearing). Cerebral MRI scans of all patients were unremarkable.

Experimental setup

Positioning manoeuvres were performed on a table, in which a three-point posturography platform (Posture Evaluating Platform, Med-Eval Ltd, Budapest, Hungary) was incorporated. Signals produced by three mechano-electrical transducers were digitised at 8.33 Hz with 24-bit resolution. Movements of the centre of pressure (COP), as recorded by the platform during positioning manoeuvres, were analysed in two dimensions, that is the anterior–posterior and lateral directions. The spatial resolution of the calibrated signal was 1 mm.

Paradigms

Subjects were seated on the platform and instructed to avoid unnecessary limb or body movements (with hands, head or body). In sequence, the investigator (BB) performed the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre on each side, and while sitting up the COP movement was recorded. Eye movements were observed using Frenzel’s glasses, and symptoms associated with position changes (vertigo/dizziness, vegetative reactions) were noted. Each patient’s head was always held by the investigator during positioning, to guide the movement without force. In particular, patients had to sit up without help, and special care was taken not to influence the patients’ trunk movements while sitting up. In some cases, body oscillations while sitting up were so strong that the investigator had to support the body to prevent falling. In such cases, the trials were excluded from the analysis. In the healthy subjects, Dix–Hallpike manoeuvres were done twice to each side, and results were pooled to obtain averages. In the patients, however, these manoeuvres were carried out four times to both sides in order to assess the effect of repeated positioning. After the first two Dix–Hallpike manoeuvres, that is one to each side, 90° supine roll manoeuvres were inserted, again one to each side, to assess eye movements and symptoms provoked by stimulation of the lateral semicircular canals.

Data analysis

The COP curve was windowed. The starting-point of the analysed period was the beginning of the sitting-up movement, and the analysis ended when the COP reached the same position as before the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre. Hence, we usually analysed a period of around 2–3 s during the act of sitting up and immediately afterwards, until the trunk oscillations ended. These were quantified by comparing the windowed original trace with its filtered version obtained by finite impulse response filtering. The filter uses a 2 s broad moving average filter, which operates by averaging a number of points from the input signal to produce each single point in the output signal. First, the average of the first subset of numbers was calculated. The fixed subset was moved forward to the new subset of numbers, and its average as a new value was calculated. The process was repeated over the entire data series. The plot line connecting all the (fixed) averages is the moving average.

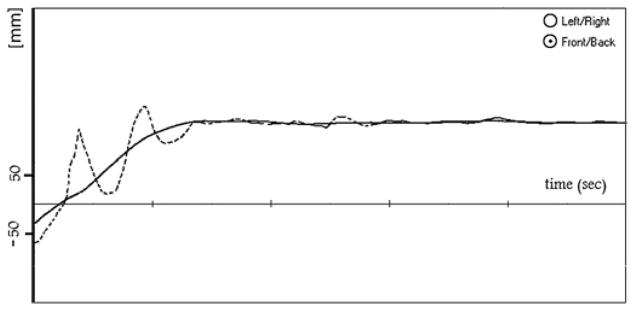

The traces were windowed, and the part containing the movement of sitting up was used. The factor Fosc representing trunk oscillations was computed by:

where Lo is the length (mm) of the original trace, and Lf is the length (mm) of the filtered trace measured (see figure 1). The original trace, because of its troughs and ridges, is much longer than the filtered trace, which shows an optimal curve that the patients should have produced by sitting up smoothly. The above ratio shows (in percentage) the extent by which the original trace is longer.

Figure 1.

Example of the analysis of the posturography curve (Patient 1, same curve as in figure 2B): the trace has been windowed starting with the deflection marking the beginning of sitting up. Dashed curve: original, continuous line: filtered curve. Fosc: 69%. Units: time axis =1 s, ordinate =movement of the centre of pressure (mm).

This computation was done for both anterior–posterior and lateral directions of the platform coordinate system. Fosc was considered normal within the mean value±2 SD of the healthy control group (between 0 and 14.9%).

For values over the normal limit (pathological high Fosc over 14%), we calculated the asymmetry ratio using a version of the standard Jongkees formula for asymmetry calculations in vestibular testing: [(Fosc of side with vertigo − Fosc of other side)/(Fosc of side with vertigo+Fosc of other side)]×100.

RESULTS

Frequency of BPPV subtypes

Table 1 lists the frequencies of diagnoses of the 200 consecutive patients with vertigo/dizziness seen in the outpatient vertigo centre. Type 1 (classical) BPPV had a frequency of 19.5%, while Type 2 BPPV was approximately twice as frequent. All patients with BPPV could be assigned to Type 1 or Type 2 BPPV, that is there where no patients classified with ‘other sBPPV.’

Table 1.

Frequency of Type 2 benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo (BPPV) among other diagnoses in an unselected group of vertigo/dizziness patients

| Diagnosis | Frequency (%) | Mean (±SD) age | Males: females |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPPV | |||

| Type 1 BPPV (right: 23; left: 16) | 19.5 | 62±14 | 12:27 |

| Type 2 BPPV (right: 49; left: 37) | 43 | 64±15 | 36:50 |

| Other subjective BPPV | 0 | ||

| Chronic vestibular insufficiency | 5 | 71±17 | 4:6 |

| Vestibular migraine | 8.5 | 48±14 | 4:13 |

| Ménière’s disease | 15.5 | 61±12 | 12:19 |

| Other (phobic vertigo, central neurological disorders, vestibular schwannoma) | 8.5 | ||

Posturography

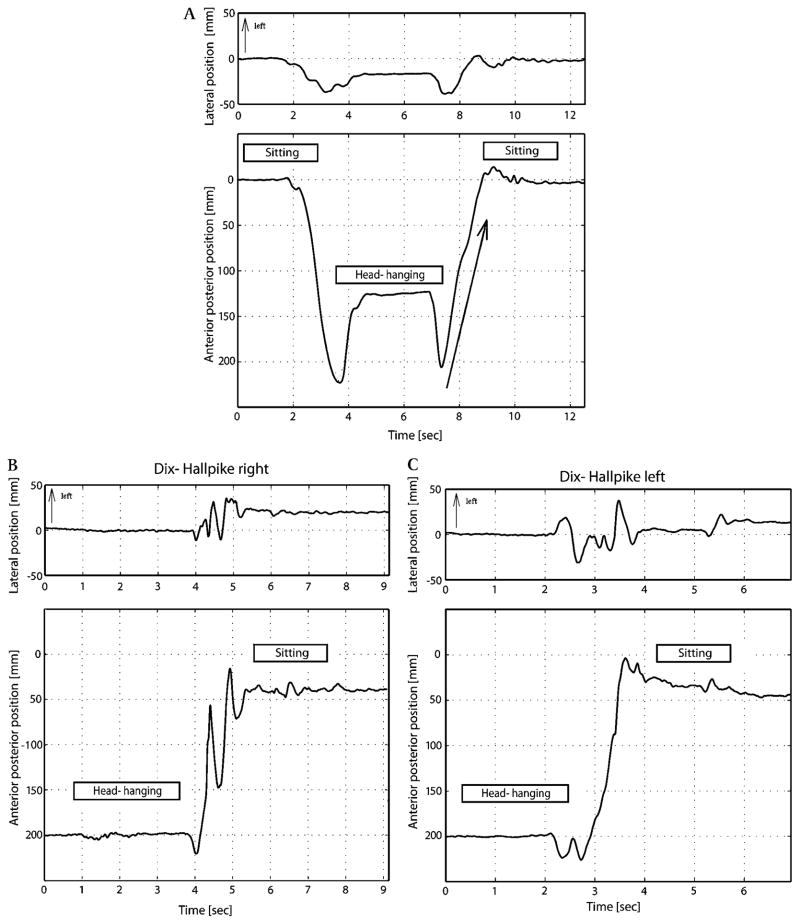

Figure 2 depicts the movements of the centre of gravity in a healthy control subject and in a typical patient (Patient 1) during the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre. A typical example of how Fosc was determined is shown in figure 1.

Figure 2.

(A) Movements of the centre of gravity in a healthy control subject during the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre. The peaks of the trace during movements to and from the head-hanging position are due to the supporting effects of a pillow under the subject’s back. The movements after the second peak were analysed further to assess trunk oscillation elicited by sitting up (see figure 1). The arrow shows the time interval of the movement of centre of pressure during the act of sitting up from the Dix–Hallpike position. (B) Patient 1, Sitting up from the side with vertigo. Posturographic traces of a typical patient with Type 2 BPPV (Patient 1) during the act of sitting up from the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre. When sitting up from the right Dix–Hallpike head-hanging position, the patient’s trunk oscillated along the anterior–posterior direction (Fosc=69%), but not when sitting up from the left head-hanging position (Fosc=14%). (C) Patient 1, Sitting up from the side without vertigo. There is no trunk oscillation.

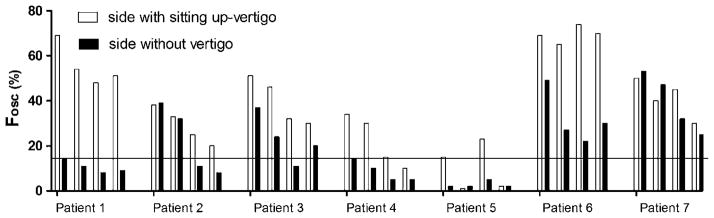

We examined 20 patients using posturography. All of them experienced short vertigo spells while sitting up from Dix–Hallpike position, in seven cases associated with abnormal antero- and retropulsion, that is oscillation, of the trunk (figure 3). Three of these seven patients noticed a slight vertigo also in the Dix–Hallpike position on the side of stronger body sway.

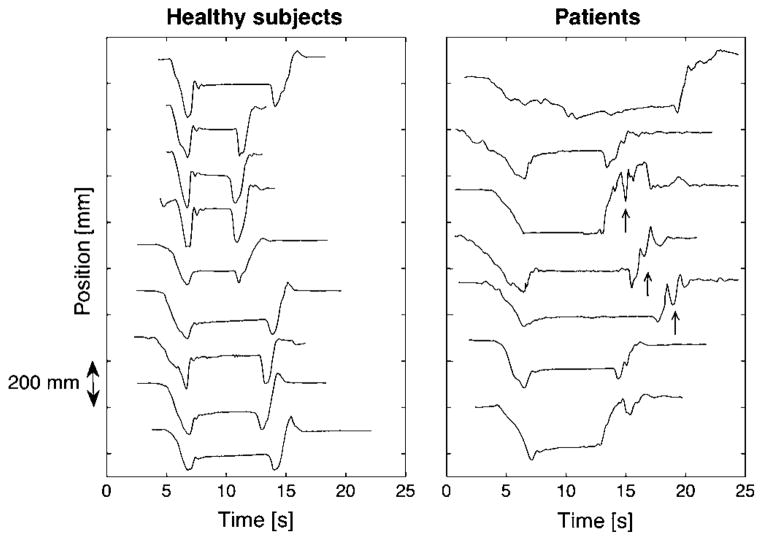

Figure 3.

Movement of centre-of-pressure in the anterior–posterior direction during Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre to one side followed by sitting up. Left panel: 10 healthy subjects, positioning to and from the right head-hanging position. Right panel: seven patients with transient retropulsion while sitting up; side of positioning associated with stronger vertigo sensation (patients’ numbers starting from above (side; Fosc): 2 (right; 38%); 7 (right; 49%), 6 (right; 69%), 3 (left; 52%), 1 (right; 69%), 5 (right; 15%), 4 (right; 34%). In some cases (arrows), the transient retropulsions occurred mainly during the act of sitting up; in other cases for a short time immediately afterwards.

In 13 patients with Type 2 BPPV, traces were similar to that of normal individuals (as in figure 2A). No transient retropulsion occurred in the anterior–posterior plane, and Fosc was within the average value±2 SD of the healthy control group (under 14.9%). In this group, eight patients reported malaise after the fourth sitting-up manoeuvre.

In seven patients, the sitting-up movement was interrupted by one or more transient backward movements of the trunk. These retropulsions were the strongest during the initial second of the movement but lasted as slight, damped oscillations for 1–2 s after the patient reached the sitting position. Figure 4 compares Fosc from four consecutive Dix–Hallpike manoeuvres to both sides in these seven subjects. All patients complained of strong nausea and sweating during and after trunk oscillations. There was a clear tendency of decreasing trunk oscillations with each repetition of the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre, but the oscillations were always asymmetrical, that is predominated when sitting up from the right or the left head-hanging position.

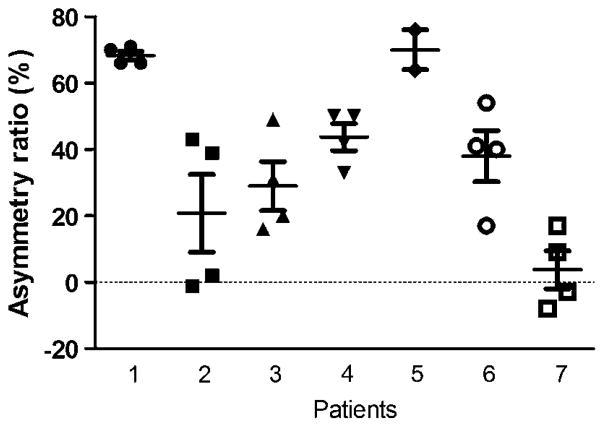

Figure 4.

Fosc from four consecutive Dix–Hallpike manoeuvres to both sides in seven patients suffering from Type 2 BPPV with trunkal retropulsion while sitting up from a Dix–Hallpike position. Stronger vertigo sensation while sitting up: right side of patients 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7; left side of patient 3. Normal range of Fosc: 0–14.9%; the horizontal line shows the upper limit of the normal range.

Figure 5 shows the asymmetry ratio in all seven patients (calculated from the data presented in figure 4).

Figure 5.

Asymmetry ratio in seven patients (mean±SEM, patients’ numbers as in figure 4). In the case of Patient 5, two points were omitted. These points represented very small Fosc values, within the normal range on both sides.

Table 2 compares the mean (±SD) of Fosc between the healthy control group and the group of patients with Type 2 BPPV. Oscillations in the anterior–posterior plane showed reproducible side differences, that is, they were always stronger on the side of subjective vertigo when sitting up. Values for lateral oscillations overlapped between healthy subjects and patients because our analysis proved to be very sensitive concerning lateral body sway, and it was difficult even for normal individuals to sit up from the lateral head-hanging position entirely without swinging slightly from side to side during the movement. On the other hand, patients did not exhibit extreme body sway in the lateral direction.

Table 2.

Anterior–posterior and lateral sway while sitting up.

| Subjects/side | Fosc anterior– posterior (%)

|

Fosc lateral (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Healthy subjects (n=9) | 5.0 | 4.9 | 68.8 | 12.3 |

| Type 2 benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo patients (n=20) | ||||

| With normal trunk sway, side without vertigo (n =13) | 4.8 | 4.5 | 65.1 | 13.4 |

| With normal trunk sway, side with vertigo (n =13) | 4.6 | 4.6 | 67.5 | 14.5 |

| With retropulsion, side without vertigo (n =7) | 19.8 | 15.2 | 66.1 | 14.4 |

| With retropulsion, side with vertigo (n =7) | 38.2 | 20.6 | 69.5 | 11.6 |

Therapy

All 20 patients with Type 2 BPPV were instructed to repeat the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre at home, 20 times on both sides (with 4–5 s in each head-hanging position), once daily, in the morning. We assessed the complaints by a telephone interview after 2 weeks. By then, none of the patients had any complaints. However, some patients described worsening of the dizziness and nausea during the first few days of the exercises. In three patients, hospitalisation or ambulatory reassessment was necessary, because horizontal canalolithiasis developed. This was treated successfully using the necessary barbecue manoeuvre.9 In these three patients, Fosc had been normal on both sides before exercises and horizontal canal canalolithiasis occurred on the second day of exercises. Horizontal canalolithiasis developed on the side, on which the patients noticed vertigo when sitting up after a Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre. Patients were instructed to carry on with the training every day and not to quit the exercises. None of the patients have suffered a relapse until the preparation of this manuscript (shortest follow-up 6 months).

DISCUSSION

The main result of our study is that seven out of 20 patients with sBPPV showed increased anterior–posterior body sway, that is trunk oscillations. These oscillations could be divided into: (1) short retropulsions during the act of sitting up from the Dix–Hallpike position (patients pushed their body back during the sitting-up movement); (2) damped trunk oscillations for a short time immediately after the patient reached the final sitting position. This is the first time that such retropulsion while sitting up has been documented in cases of suspected BPPV. Our method was sensitive to the oscillations in the anterior–posterior (diagonal) plane. Lateral trunk sway immediately after the sitting-up manoeuvre was also visible in the patients, but in our limited sample, parameters for lateral sway were not significantly different between patients and healthy subjects. A planned study with a large sample will allow a more detailed comparison of lateral sway between patients and healthy subjects.

Due to the small number of patients, on whom we performed posturographic measurements, detailed statistical significance testing was not possible, but the following trends are noteworthy and should be studied further in larger samples:

In five of the seven patients with documented sitting-up trunk oscillations, reproducible differences of trajectories between sitting up from the two sides could be observed. The side of greater retropulsion was also the side on which patients reported more vertigo.

Retropulsion and vertigo decreased with repeated manoeuvres

There have been studies to examine body sway using posturography in BPPV cases. However, those studies examined patients with classical BPPV, not sBPPV. Still, some of the results seem to be relevant for interpreting our results. Stambolieva et al measured the effect of the Epley manoeuvre in posterior BPPV using classical standing posturography.13 Their most important result was, that, even after a successful Epley liberation manoeuvre, increased body sway remained. Giacomini et al examined 20 patients with canalolithiasis of the posterior semicircular canal and 20 healthy control subjects using static posturography 1 h after diagnosis, 3 days and 12 weeks after the corresponding Epley repositioning manoeuvre.14 The authors found that patients with BPPV showed significantly increased body sway in both the lateral and antero-posterior directions compared with healthy subjects. The repositioning manoeuvre decreased the lateral body sway, while the antero-posterior sway remained, causing the chronic dizziness observed in these patients. In a similar study, Blatt et al found that many patients with BPPV, who had a complete remission of the positional vertigo after treatment, still did not reach normal postural stability; this finding was predominant in elderly patients.15

These studies seem to corroborate our results and to indicate that many patients with classical BPPV continue to suffer from subjective vertigo with postural symptoms as seen in our patients with sBPPV. In the study by Giacomini et al, this instability could even be assigned to the antero-posterior axis, which may correspond to our finding of sitting-up retropulsion in some of the patients with sBPPV.14

It might be argued that the transient retropulsion observed while sitting up is in fact a sign of cerebellar truncal ataxia. This is unlikely, because the majority of the patients showed a lateralisation of the retropulsion (more oscillations while sitting up from one side than from the other side) and sitting-up retropulsion and vertigo swiftly decreased with repetitions of the sitting-up manoeuvre. The lateralisation of sitting-up body oscillation was further quantified by the asymmetry ratio in analogy to Jongkees formula, which is used for calculating vestibular asymmetry after caloric examination. Iwasaki et al already applied such asymmetry calculation for measurements other than caloric reaction.16

Since the patients with sBPPV share complaints of classical BPPV, possible aetiologies within the labyrinths need to be considered. In his original paper, Buckingham has expressed concerns about the fate of repositioned particles.17 He showed on 2 mm thick microsections of human temporal bones that loose otoliths falling from the utricular macula are bound to fall into the short arm of the posterior canal onto the utriculopetal side of the cupula, which opens directly into the inferior portion of the utricle. We hypothesise that these particles may cause chronic Type 2 BPPV.

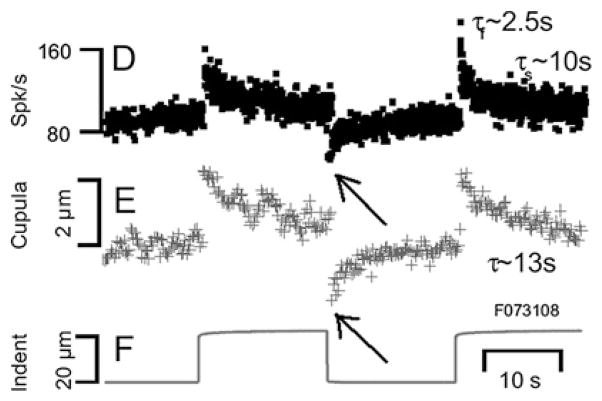

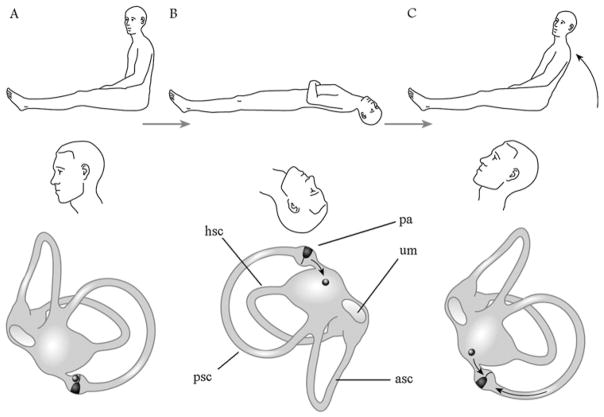

Since the vertigo sensation in patients with Type 2 BPPV can be elicited either in the right anterior–left posterior or in the left anterior–right posterior plane, it is likely that the vertical semicircular canals are involved. More specifically, we suggest chronic short-arm canalolithiasis of the posterior canal on the involved side as a cause of the complaints. In this hypothetical case, in upright posture the posterior cupula is chronically deflected by the weight of the debris that lies on the utricular surface of the cupula. The cupula becomes adapted to the extreme position. Such vestibular adaptation following sustained displacement of the cupula was recently demonstrated by Rabbitt and colleagues (figure 6).18

Figure 6.

Example of short-term adaptation (from Rabbitt et al18 with permission). The dynamic displacement of the semicircular canal cupula and modulation of afferent nerve discharge were measured simultaneously in response to physiological stimuli in vivo in the oyster toadfish horizontal ampulla. Sustained stimulus caused a decline of the afferent discharge (upper trace) and cupula displacement (middle trace). Elimination of the stimulus (lower trace) therefore resulted in an inhibition of both parameters, even below the original baseline (arrows by us). Sustained stimuli sensitise the vestibular organ against stimuli acting in the other direction.

The chronic dizziness experienced by Type 2 BPPV patients may be caused by the constantly changing mechanical load, which the debris exerts on the cupula during everyday activities. According to the anatomical reconstructions of Buckingham,17 when the head is in the hanging position during the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre, the posterior canal cupula hangs vertically downward, so it will not be deflected further in the Dix–Hallpike position than in upright position, and so no nystagmus ensues. Moreover, in this head position, the particles fall down from the cupula into the utriculus in the vestibulum. Trunk oscillations during and shortly after sitting up may be caused by different mechanisms. By losing the mechanical load, and because it had been adapted to an extreme deflected position, the cupula overreacts when, while sitting up, the endolymphatic flow pushes it toward the vestibulum (figure 7). Thereby, the patients receive the impression that they are falling forward, and transient retropulsion occurs. Trunk oscillation immediately after sitting up may be elicited by particles falling back onto the cupula in the upright position.

Figure 7.

Hypothetical mechanism of Type 2 benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo. The right vestibular labyrinth is illustrated from the medial aspect. (A) Posterior cupula chronically deflected by the weight of the debris; the cupula becomes adapted to this extreme position. (B) Dix–Hallpike position. Particles fall down from the cupula. (C) Trunk oscillations during and shortly after sitting up. These may be caused by different mechanisms. By losing the mechanical load and because of the adaptation, the cupula over-reacts when, while sitting up, the endolymphatic flow pushes it toward the vestibulum. Thereby, the patients receive the impression that they are falling forward, and transient retropulsion occurs. Trunk oscillation immediately after sitting up may be elicited by particles falling back onto the cupula in the upright position. asc, anterior (superior) semicircular canal; hsc, horizontal semicircular canal; pa, posterior ampulla; psc, posterior (inferior) semicircular canal; um, utricular macula.

Buckingham may have been right, when he suggested that the particles removed from the canals are flushed into the utriculus and then fall on the posterior cupula. Other authors also consider the role of utricular debris. Oas suggested the term ‘utriculolithiasis’ and a new terminology to differentiate ‘short-arm’ from ‘long-arm’ canalolithiasis.19 The already cited posturography results of Stambolieva et al and Giacomini et al can also be interpreted in the light of this hypothesis: although positional nystagmus is inhibited by a successful Epley manoeuvre, the debris floating in the utriculus and settling in the long arm causes increased body sway.13,14 In our group of 20 patients with Type 2 BPPV, only seven patients showed transient retropulsions while sitting up. We suggest that in the other 13 cases, smaller particles caused less severe symptoms.

BPPV often starts as an acute, severe vertigo spell (with vertigo and vomiting), lasting 1 or 2 days; then the symptoms diminish spontaneously over several days, as natural head movements of the patients involuntarily ‘reposition’ particles. The frequency of successful spontaneous reposition depends on which semicircular canals are affected. A spontaneous clearing is easiest in the anterior canal, since the debris may float into the utriculus when the patients assumes a slightly head-hanging position and then sits up again. Rolling movements in the bed may cause spontaneous reposition of the horizontal canal. Debris falling into the utriculus may be deposited in the short arm of the posterior canal. Because of its inferiorly positioned and conical form, it funnels remaining, small debris onto the posterior cupula where it remains for a longer time.

Present research on on-site and off-site otolithic growth may answer the question of whether otoliths deposited in the short arm of the posterior semicircular canal could persist or even grow there.20 If fine ionic regulations do not function properly, crystal seeds may grow off-site. This may be the case in spite of the fact that under normal conditions, the Ca2+ concentration in the endolymph is considerably lower than the level required for spontaneous crystallisation.21 Ectopic growth is possible because ion-transporting cells are present in the non-sensory parts of the vestibule.22 Also, local hypercapnia may increase calcification. Checkley et al, for instance, have shown in fish endolymph that, with constant pH, elevated CO2 increases CO32− concentration and thus accelerates the formation of otolith-aragonite.23

In our study, in three patients (out of 20 Type 2 BPPV patients) a horizontal canal canalolithiasis developed on the second day, after the patients had started everyday training. They developed on the side where the patients noticed vertigo when sitting up after the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre. In our view this corroborates the hypothesis that the exercises work by dispersing particles that are chronically present in the short arm. During repeated exercises in the Dix–Hallpike position, they may be repositioned into the utriculus and swim into the horizontal canal.

In conclusion, we suggest that sBPPV is more common than anticipated. Type 2 BPPV may be identical with sBPPV or constitute a major subgroup of it. For a definition of Type 2 BPPV, we suggest the following: (1) complaints suggesting BPPV (short episode of vertigo when bending forward, lying down, sitting up or turning over in bed); (2) no nystagmus during either Dix–Hallpike positioning or supine roll to the left and right; and (3) a short episode of vertigo during and immediately after sitting up from the a Dix–Hallpike position. We did not find any patients with sBPPV complaints who could not be assigned to the group with Type 2 BPPV. Nevertheless, we prefer to leave open the possibility that mechanisms other than chronic short-arm canalolithiasis may cause sBPPV. We suggest that the introduction of Type 2 BPPV as a valid differential diagnosis of patients with positioning vertigo will lead to better classification and therapy in numerous cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their thanks to GM Halmágyi (Sydney), for his continuing support and useful comments, and to two unknown reviewers, for their work and suggestions. We thank G Kronik, Medical Director of Krems General Hospital, for his support. Figure 7 was drawn by Z Bodor (http://www.bodorzoltan.hu) and published with permission of Medicina Kiadó.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

Ethics approval Ethics approval was provided by the Ethical Committee, General Hospital Krems.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mizukoshi K, Watanabe Y, Shojaku H, et al. Epidemiological studies on benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in Japan. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1988;447:67–72. doi: 10.3109/00016488809102859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Froehling DA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, et al. Benign positional vertigo: incidence and prognosis in a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:596–601. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60518-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oghalai JS, Manolidis S, Barth JL, et al. Unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in elderly patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:630–4. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, et al. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:710–15. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katsarkas A. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV): idiopathic versus post-traumatic. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999;119:745–9. doi: 10.1080/00016489950180360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosca F, Morano M. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, incidence and treatment. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2001;118:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, et al. American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(5 Suppl 4):S47–81. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) Review. CMAJ. 2003;169:681–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aw ST, Todd MJ, Aw GE, et al. Benign positional nystagmus: a study of its three-dimensional spatio-temporal characteristics. Neurology. 2005;64:1897–905. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000163545.57134.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haynes DS, Resser JR, Labadie RF, et al. Treatment of benign positional vertigo using the semont maneuver: efficacy in patients presenting without nystagmus. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:796–801. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tirelli G, D’Orlando E, Giacomarra V, et al. Benign positional vertigo without detectable nystagmus. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1053–6. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200106000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weider DJ, Ryder CJ, Stram JR. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: analysis of 44 cases treated by the canalith repositioning procedure of Epley. Am J Otol. 1994;15:321–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stambolieva K, Angov G. Postural stability in patients with different durations of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:118–22. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-0971-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giacomini PG, Alessandrini M, Magrini A. Long-term postural abnormalities in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2002;64:237–41. doi: 10.1159/000064130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blatt PJ, Georgakakis GA, Herdman SJ, et al. The effect of the canalith repositioning maneuver on resolving postural instability in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Am J Otol. 2000;21:356–63. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(00)80045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwasaki S, Smulders YE, Burgess AM, et al. Ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in response to bone-conducted vibration of the midline forehead at Fz. A new indicator of unilateral otolithic loss. Audiol Neurootol. 2008;13:396–404. doi: 10.1159/000148203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckingham RA. Anatomical and theoretical observations on otolith repositioning for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:717–22. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabbitt RD, Breneman KD, King C, et al. Dynamic displacement of normal and detached semicircular canal cupula. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2009;10:497–509. doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0174-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oas JG. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a clinician’s perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;942:201–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lundberg YW, Zhao X, Yamoah EN. Assembly of the otoconia complex to the macular sensory epithelium of the vestibule. Review Brain Res. 2006;1091:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salt AN, DeMott J. Endolymph calcium increases with time after surgical induction of hydrops in guinea-pigs. Hear Res. 1994;74:115–21. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imon K, Amano T, Ishihara K, et al. Existence of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in vestibular dark cells: cytochemical and whole-cell patch-clamp studies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;254:287–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02905990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Checkley DM, Jr, Dickson AG, Takahashi M, et al. Elevated CO2 enhances otolith growth in young fish. Science. 2009;324:1683. doi: 10.1126/science.1169806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]