Abstract

A large percentage of swimmers report shoulder pain during their swimming career. Shoulder pain in swimmers has been attributed to duration of swim practice, total yardage, and break down in stroke technique. Rehabilitation programs are generally land‐based and cannot adequately address the intricacies of the swimming strokes. Return to swimming protocols (RTSP) that address progression of yardage are scarce, yet needed. The purpose of this clinical commentary is to familiarize the clinician with the culture and vernacular of swimming, and to provide a suggested yardage based RTSP for high school and collegiate level swimmers.

Level of Evidence:

5

Keywords: Freestyle stroke, technique, yardage

INTRODUCTION

Forty to ninety‐one percent of age group through masters' level swimmers report shoulder pain at some point during their careers.1‐6 Furthermore, increased shoulder pain has been related to duration of swim practice, total yardage, and break down in stroke technique.1,3,7‐9 During rehabilitation, all of these components may need to be addressed. One key component of rehabilitation is return to sport specific activities and progressions. Interval return to sport programs exist for activities such as baseball,10,11 running, tennis, golf and softball.12‐14 Unfortunately, interval return to swimming protocols (RTSP) are scarce.15 The culture of swimming is that the athletes spend large quantities of time in the pool practicing; therefore it is important to get swimmers back in the pool practicing as soon as possible.16 Adding to the complexity of utilizing an RTSP, swimming has its own vocabulary and training rituals that are engrained in the culture. One beneficial component of the swimming culture is that training is yardage based allowing for the development of an interval training protocol utilizing yardage. Another key component in the swimming culture focused on by coaches and swimmers is the importance of proper stroke mechanics to increase efficiency and decrease injury risk. Poor mechanics during swimming has been linked with injuries and consequently needs to be understood and addressed in the rehabilitation process.5,17‐19

This current concept paper has three objectives. First, to familiarize the clinician with the culture and vocabulary of swimming so that communication between the clinician and athlete and coaches is enhanced. Second, to describe a protocol based on yardage that incorporates specific drills to improve stroke mechanics and interval work in order to gradually restore speed. The final objective is to share a case example of how the RTSP was used in the return to sport of a collegiate swimmer.

Swimming Rehabilitation Review

Swimming specific rehabilitation traditionally focuses on scapular stabilization,20 core body strength, neuromuscular re‐education of the shoulder musculature,21,22 correction of forward head and rounded shoulder posture,23 and generally takes place in a clinic on dry land. There are excellent articles and case reports that address clinical rehabilitation techniques but these are not the focus of this clinical commentary.20,23‐26 Attempts to replicate freestyle stroke technique using dry‐land swimming benches have been found to recruit muscle in different patterns and may not replicate the swimming stroke ideally.16,27 So, when working to correct a swimmer's stroke technique, it is best done in the water. Understanding the stroke mechanics and the drills that are commonly used by coaches in the swimming community to enhance stroke technique is important.

Freestyle Biomechanics

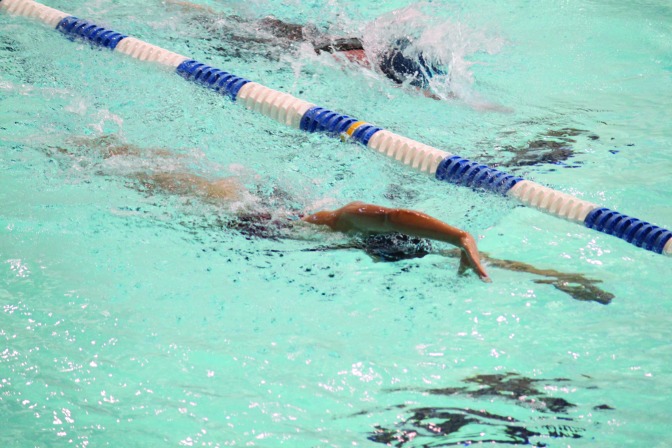

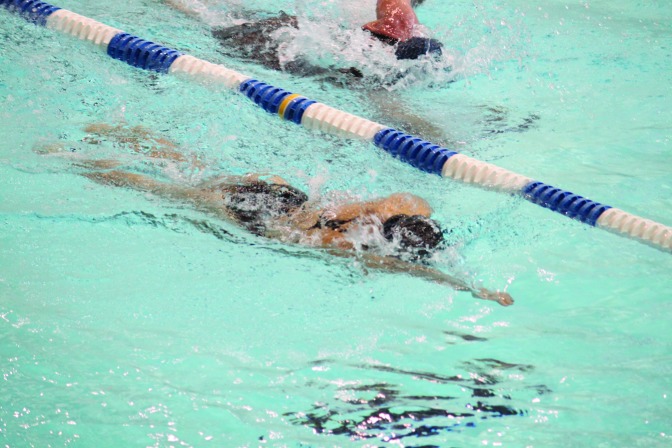

Proper technique of the freestyle stroke is important to injury prevention.4,5,9,17,18,28,29 While the swim coach should be the primary person to evaluate a swimmer's stroke technique, clinicians should have working knowledge of how freestyle stroke technique should look (Figure 1). There are several extensive articles that describe the mechanics of freestyle and the other competitive swimming strokes that are beyond the scope of this clinical commentary. For more in‐depth knowledge the reader is referred to these articles.4,8,17,18,28‐30

Figure 1.

The freestyle swimming stroke.

There are various descriptions of the freestyle stroke. The biomechanical literature breaks freestyle stroke into five phases,31 while the more clinically focused literature breaks the freestyle stroke into three or four phases.4,29,32 Since the objective of this paper is to provide a general RTSP for clinicians, the freestyle stroke has been divided into four phases: hand entry, early pull‐through, late pull‐through, and recovery.4,18,28,30 It is important to note that a breakdown in one part of the stroke cycle can result in compensatory strategies throughout the rest of the cycle, leading to potential injury.4,9,18,29,30 Hand entry occurs as the finger tips break the surface of the water (Figure 2).4,18 Early pull‐through is defined as the point from which the hand enters the water till it is perpendicular with the body (Figure 3).4,30 During the late pull‐through phase, the arm moves under the body accelerating until the arm exits the water (Figure 4).4 Recovery phase begins as the arm exits the water and ends as the finger tips break the surface of the water (Figure 5).4,8,18,28,29

Figure 2.

Hand entry (right UE)

Figure 3.

Early pull‐through phase (right UE)

Figure 4.

Late pull‐through phase (right UE)

Figure 5.

Recovery phase of the freestyle stroke. Note high elbow position.

Each phase has the potential to have biomechanical flaws that could result in injury.4,5,29 A common flaw observed during hand entry is when the swimmer enters the water with the hand either medial or lateral to the midline. A right hand should enter the water at approximately one o'clock and a left hand at 11 o'clock with the swimmer's head representing 12 o'clock. Deviations, either medial or lateral represent an error because they increase the stress on the rotator cuff.4,8,17,18,28,29 During early pull‐through, a common flaw observed in swimming mechanics is the “dropped elbow”.4,18,28,29 As the hand enters the water, the wrist is slightly flexed and the elbow should remain higher than the hand while the arm pulls under the body. This position engages the latissumus dorsi muscles and sets the swimmer up to pull the body over the arm preventing impingement.4,18,29 It also creates a smooth, symmetrical body roll which decreases stress on the rotator cuff muscles and allows the scapula to stay appropriately anchored on the thorax.4,17,18 A straight arm recovery is yet another flaw that occurs during freestyle swimming.4,29 This means that during the recovery phase, the elbow is fully extended while the arm is out of the water. During the recovery phase, a bent elbow is favorable because it reduces the amount of stress on the rotator cuff.29 For a more in depth explanation of errors made during freestyle swimming, readers are encouraged to review the article by Virag et al.29

Freestyle swimming uses a flutter kick. Flutter kicking requires alternating motions of the legs. When performed correctly, the flutter kick agitates the water giving it the appearance of boiling water. The power of the kick comes from the hip flexors and extensors. The knee is slightly flexed and extended while the ankles are plantar flexed and inverted. The even four or six beat kick (the equivalent of two or three kicks per individual arm revolution) are most commonly used by distance and sprinters, respectively., Taking a breath every three arm strokes, also referred to as an alternate breathing pattern, is also helpful for developing a freestyle stroke with correct biomechanics.18,28

Return to Swimming Protocol

To familiarize the clinician with the swimming culture, a vocabulary of common terminology has been created (Appendix 1) to better communicate with the swimmer and speak their language when discussing swimming. There are several pieces of equipment, described in Table 1, that are commonly used in swim training and may be beneficial in returning a swimmer to full activity. However, there are contraindications to the use of equipment that are important for the rehabilitation professional to understand. Numerous drills are used to help swimmers focus on maintaining proper stroke technique throughout swim practice. The most common drills and the phase of the stroke cycle they focus on are described in Table 2.

Table 1.

Swimming Tools. Tools commonly used by competitive swimmers. Tools should be used with caution depending on swimmer's injury.

| Tool | Name | Use/Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Kickboard | Used to focus on kicking only; Most commonly used with arms extended in front of the body; creates lumbar lordosis | Shoulder injuries; spondylolysis |

|

Pull buoy | Used to focus on arm stroke only; Placed between upper legs to prevent kicking while providing buoyancy to the lower body | Shoulder tendinitis/tendinosis; elbow or forearm pain |

|

Fins | Used to increase leg length and surface area of the feet; increase propulsion of stroke | Acute ankle injuries; knee pain |

|

Zoomers | Used to increase leg strength; increase surface area of the feet, but are shorter than fins and allow for rapid leg motions to increase forward propulsion | Acute ankle injuries; knee pain |

|

Paddles | Worn on hands; come in variety of sizes; increase surface area of the hand; slow down pull when worn, but build strengthwhile pulling | Shoulder injury or pain; improper stroke technique |

Table 2.

Swimming Drills. Drills used by swimmers to focus on technique during various phases of the stroke cycle.

| Drill | Guidelines to Perform Correctly | Focus of Drill | Phase of Stroke Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fingertip drag | The swimmer's face remains facing the bottom of the pool while the torso rotates on an imaginary long axis. As the swimmer begins the recovery portion of the arm stroke, he drags the fingers tips along the water surface during recovery. | Promotes a bent elbow recovery and symmetrical body roll | Recovery |

| Shoulder, Head, Enter | The swimmer performs freestyle, focusing on a high elbow that is flexed and recovers high out of the water. During the recovery, the swimmer taps the axillary's region, the head and then reaches in front of the body at the position of 1:00 on a clock to grab the water for hand entry. | Promotes high elbow recovery, symmetrical body roll, and proper hand entry | Recovery/Hand Entry |

| 6/6 | The swimmer is positioned on his side with the arm closest to the bottom of the pool over the head(ear against bicep). The swimmer performs 6 kicks on one side, takes three long freestyle stroke cycles focusing on a high elbow recovery, and 6 kicks on the opposite side. | Promotes symmetrical body roll | Recovery/Hand Entry/Early Pull Through |

| Left arm, right arm, both arm | Swimmer performs three strokes on the left side focusing on placing the hand in the water at 11 and 1 o'clock, and keeping a steady rhythmic kick (6‐beat). The swimmer repeats the same motion on the right side. | Promotes proper hand entry, bent elbow recovery, symmetrical body roll | Hand Entry/Early Pull Through |

| Flutter kick without a kick board on side | Swimmer maintains tight core, arm closest to the bottom of the pool is extended next to the ear, and the swimmer should try to maintain this straight body position. | Core body strength | Early Pull Through/Late Pull Through |

| Catch up | Swimmer exaggerates the recovery and catch phase of the freestyle stroke. The left arm catches up to the right arm. The 6 beat kick should be focused on. | Promotes proper hand entry | Hand Entry |

| Fist | Swimmer makes a fist while performing the pull through phase of the stroke. Focus is on the rotation of the torso and the high elbow during the early pull phase of the stroke. | Helps to appreciate the sensation of the forearm while pulling the water. This is also known as appreciating the “feel the water” with the hand and forearm as a unit | Early Pull Through/Late Pull Through |

| 4 strokes of backstroke/4 strokes of freestyle | Swimmer does four cycles of backstroke and four cycles of freestyle. Exaggeration can be placed on the roll of the body when switching from back to front. The hips/torso should drive the body rotation. | Promotes high elbow pull through | Early Pull Through/Late Pull Through |

| Distance per Stroke (DPS): | Swim freestyle trying to extend the arms and maximize stroke length. Swim freestyle, roll the body and extend the arms with each pull. As the body is extended, focus on rotating the hips from side to side and extending the arm. Try to reduce strokes with each 25 swam. This is best if performed in sets of 25's. | Helps to “feel the water” with the hand and forearm. | Early Pull Through/Late Pull Through |

| Sculling | Can be performed prone or supine. Slight motion of the hand and forearms back and forth just under the surface of the water to propel the swimmer forward. This is best if performed in sets of 25's. | Helps to appreciate the sensation of the forearm while pulling the water. This is also known as appreciating the “feel the water” with the hand and forearm as a unit | Hand Entry/Early Pull Through |

The criterion to begin the RTSP include: 1) the swimmer should be nearly pain free in the shoulder complex and 2) full active extension and external rotation of the glenohumeral joint should exist. The strength of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizing muscles should be a 5/5 when tested using traditional manual muscle testing.25,33 Phase One of the RTSP focuses on stroke technique drills to prevent the swimmer from reverting to bad habits that could reinjure the shoulder. The yardage increases in small increments to prevent overuse. Phase Two focuses on interval work designed to help build the swimmer's muscular and cardiovascular fitness levels. Yardage increases in larger increments in order to help build endurance as the swimmer demonstrates he or she can tolerate longer practices. The RTSP is designed to gradually return the swimmer to practice, so focus on the swimmer's specialty stroke or distance is not addressed at this point. It is the authors' opinion that the swimmer should swim with proper freestyle technique and without pain before performing event specific and distance specific practices.

Table 3 illustrates the key points of progression during the RTSP. The components of a swim practice include variations in warm‐up, drills, kick, pull, intensity, and rest. Criteria to progress from phase to phase are defined in Table 3. It is necessary for the swimmer and coach to understand that the athlete should progress slowly. Increases in pain, soreness, or discomfort need to be recognized by the swimmer as possible warning signs to decrease training and have the coach re‐evaluate stroke mechanics (Table 4). The proposed RTSP protocol has been previously used in a collegiate swimmer to assist with return to swimming.

Table 3.

Key Points of the Return to Swimming Protocol (RTSP). Overview of the RTSP including the major components of a swimming workout and criteria for progression.

| Phase I | Phase II – Join Team | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week One 1000‐1500 | Week Two 1500‐2200 | Week Three 2200‐3000 | Week Four 2800‐3900 | Week Five 3500‐4700+ | |

| Warm Up | (300‐400) | (600‐700) | (700‐900) | (900‐1100) | (1000‐1200) |

| Drills | Stroke Technique using drills (300‐500) | Stroke Technique using drills (400‐600) | Stroke Technique using drills Incorporate drills in the beginning and end of practice (600‐700) | Incorporate drills in the beginning and at the end of practice (700‐900) | A drill set should be incorporated at the end of the workout (800‐1000) |

| Kick | With fins or zoomers, but no kick board Kick on side or back Arms can be at side or streamlined position if painfree (400 ‐600) | With fins or zoomers but no kick board Kick on side or back Arms can be at side or streamlined position if painfree (500 ‐900) | With fins or zoomers, but no kick board Kick on side or back Arms can be at side or streamlined position if painfree (700‐900) | With fins or zoomers Kick board if comfortable Kick on side or back Arms can be at side or streamlined position if painfree (700‐900) |

|

| Intervals | None | None |

|

|

|

| Pull Set | None | None | None | None |

|

| Rest between repetitions | 20‐30 seconds for all | 10‐20 seconds for all | 10‐15 seconds between repetitions Interval 5‐10 seconds rest Longer swims should have longer rest periods | 10‐15 sections between repetitions Interval 5‐10 seconds rest Longer swims should have longer rest periods | 5‐15 sections between repetitions Interval 3‐10 seconds rest Longer swims should have longer rest periods |

| Criteria to Progress |

|

|

|

Join Team

|

|

All distance is represented in yards.

Table 4.

Swimming Soreness Rules (adapted with permission from Axe, M). Guidelines to help the swimmer recognize pain and the clinician adjust the swimming portion of shoulder rehabilitation.

| If no soreness, increase 200‐300 yards each day. |

|---|

| If sore during warm‐up but soreness is gone within the first 500‐800 yards, repeat a similar workout from the previous day. If shoulder becomes sore during this workout, stop and take 2 days off. Upon returning to the pool, decrease yardage by 300 yards. |

| If sore more than 1 hour after swimming, or the next day, take 1 day off and repeat the most recent swimming workout. |

| If sore during warm‐up and soreness continues through the first 500‐800 yards, stop swimming and take 2 days off. Upon return to swimming, decrease yardage by 300 yards. |

Case Example

A 20‐year‐old, male, National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division III, distance swimmer reported to the Athletic Training Clinic following a closed anterior, Bankart repair on his right shoulder. He had completed rehabilitation at home during the summer months and was released by his physician for return to swimming upon return to college. He reported to school and was examined, demonstrating full range of motion, normal strength, and a negative anterior apprehension test.

The swimmer worked with the both the Certified Athletic Trainer and his coach using the outlined RTSP. He reported to the pool Monday, Wednesday and Friday and to the Athletic Training Clinic for formal rehabilitation Tuesday and Thursday. Table 5 details the swimmer's weekly progression using the RTSP. Phase One/Week One emphasized improving stroke technique with increased recovery. A “stroke progression,” series of drills to focus on stroke technique, was designed by the coach and incorporated into each warm up (Table 6). The swimmer increased his yardage by 30% between days 1 and 2, and 20% between days 2 and 3. This might have been too large a jump in yardage as pain was reported in the beginning of the second week that resulted in a few days off. During weeks two and three, the swimmer's daily yardage was increased by less than 5% increments, focus was placed on drill work and kicking, and interval work was introduced. No complaints or increase in symptoms were reported.

Table 5.

Sample Case. Example of a Division III Swimmer applying the RTSP. Major components of a swimming workout are defined next to each work out. Intensity is defined as a percentage of maximum effort. Rest intervals were adapted based on intensity.

| Return to Swimming Program | Case Example | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Week | Activity | Date | Drill | Yards | Repetition | Intensity | Yardage |

| Phase 1 | Week 1 | 9/28/2013 | ||||||

| Warm Up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 400 | 1 | 400 | ||||

| Drills | Stroke Progression* | 250 | 1 | 500 | ||||

| Kick | Kick with Fins | 50 | 1 | 400 | ||||

| Warm‐Down | 100 | 1 | 100 | |||||

| Total | 1400 | |||||||

| Phase 1 | Week 1 | 9/30/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐Up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 500 | 1 | 500 | ||||

| Drills | Stroke Progression* | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Odd Fist/Even Fingertip Drag Drill by 50 | 50 | 6 | 300 | |||||

| Kick | Kick with Fins | 50 | 4 | 200 | ||||

| Kick with Fins | 100 | 2 | 200 | |||||

| Kick with Fins | 200 | 1 | 200 | |||||

| Warm‐down Perfect Swim | 200 | 1 | 200 | |||||

| Total | 1850 | |||||||

| Phase 1 | Week 1 | 10/2/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 600 | 1 | 600 | ||||

| Drills | Drill of choice (from stroke progression) | 500 | 1 | 500 | ||||

| Kick | Kick (300 yards fast/500 yards moderate) | 800 | 1 | 800 | ||||

| Interval | Easy Interval | 50 | 6 | 60% | 300 | |||

| Total | 2200 | |||||||

| Phase 1 | Week 2 | 10/4/2013 | ||||||

| Day off due to shoulder pain | ||||||||

| 10/7/2013 | ||||||||

| Day off due to shoulder pain | ||||||||

| Phase 1 | Week 2 | 10/9/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle swim | 400 | 1 | 400 | ||||

| Drills | Stroke Progression | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Drills | 25 yards Finger tip drag/25 yards Catch‐Up drill | 50 | 5 | 250 | ||||

| Kick | Kick with fins | 75 | 6 | 450 | ||||

| Kick | Kick with fins‐ width of 25 yard pool ‐underwater | 1 width | 16 | 300 | ||||

| Swim fast gradually slow | 200 | 3 | 70%‐50% | 600 | ||||

| Total | 2250 | |||||||

| Phase 1 | Week 3 | 10/11/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 250 | 2 | 500 | ||||

| Drills | Swim breathing 3,5,7,9 by 25 yards | 400 | 1 | 400 | ||||

| Kick | Interval ‐25 yd Swim, 50 yd Kick, 25 yd Swim | 100 | 9 | 70% | 900 | |||

| Intervals | Speed Work | 50 | 6 | 85% | 300 | |||

| Total | 2100 | |||||||

| Phase 1 | Week 3 | 10/14/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 600 | 1 | 600 | ||||

| Drills | Stroke Progression | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Drills | 25yds scull/25 yds kick | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Intervals | Interval Work | 50 | 8 | 80% | 200 | |||

| Intervals | Freestyle Swim | 200 | 1 | 70% | 200 | |||

| Drills | Stroke Progression | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Kick | Freestyle Swim ‐ alternate 3 dolphin kicks off turn/5 dolphin kicks off turn | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Intervals | Interval Work ‐Freestyle with fins ‐25 yd easy,25yds underwaters, 25yds easy; 25 yards under water, 25 yds easy, 25 yds no breath | 75 | 8 | 70% | 600 | |||

| Perfect Freestyle Stroke | 100 | 1 | 100 | |||||

| Total | 2900 | |||||||

| Phase 1 | Week 3 | 10/16/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 600 | 1 | 600 | ||||

| Drills | Stroke Progression | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Drills | 25yds scull/25 yds kick | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Intervals | Interval Work | 50 | 8 | 85% | 200 | |||

| Intervals | Freestyle Swim | 200 | 1 | 85% | 200 | |||

| Drills | Stroke Progression | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Kick | Freestyle Swim ‐ alternate 3 dolphin kicks off turn/5 dolphin kicks off turn | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Intervals | Interval Work ‐Freestyle with fins ‐25 yd easy,25yds underwaters, 25yds easy; 25 yards under water, 25 yds easy, 25 yds no breath | 75 | 8 | 85% | 600 | |||

| Perfect Freestyle Stroke | 100 | 1 | 100 | |||||

| Total | 2900 | |||||||

| Phase 2 | Week 4 | 10/21/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 600 | 1 | 600 | ||||

| Drills | Stroke Progression | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Kick | 50yd scull/50yd kick/50 yd scull | 150 | 1 | 150 | ||||

| Intervals | Interval Work ‐ 2x through | 50 | 4 | 85% | 400 | |||

| 100 | 2 | 85% | 400 | |||||

| 200 | 1 | 70% | 400 | |||||

| Drill | Drill ‐ Breathing 3,5,7,9 rest 5sec after each 25yd | 300 | 3 | 900 | ||||

| Drill | Drill of choice | 350 | 1 | 350 | ||||

| Perfect Stroke | 50 | 1 | 50 | |||||

| Total | 3790 | |||||||

| Phase 2 | Week 4 | 10/23/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 500 | 1 | 500 | ||||

| Drill | Drill | 250 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| Kick | Kick with fins ‐ 25yd fast, 25yd underwater, 25 yds easy | 75 | 4 | 300 | ||||

| Interval | Interval Work | 125 | 6 | 90% | 750 | |||

| Interval | Freestyle Swim ‐ build | 400 | 1 | 70%‐90% | 400 | |||

| Interval | Freestyle Swim ‐ Fast/Easy by 25yd | 300 | 1 | 70% | 300 | |||

| Interval | Freestyle Swim ‐ Easy/Fast by 25yd | 200 | 1 | 70% | 200 | |||

| Interval | Freestyle Swim‐ Fast | 100 | 1 | 100% | 100 | |||

| Total | 2800 | |||||||

| Phase 2 | Week 5 | 10/28/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 1000 | 1 | 1000 | ||||

| Interval | Interval Work | 50 | 12 | 90% | 600 | |||

| Interval | Speed Work ‐ Freestyle Swim negative split | 400 | 1 | 70%‐90% | 400 | |||

| Interval | Interval Work ‐ Freestyle swim | 200 | 2 | 60% | 400 | |||

| Interval | Interval Work ‐ Freestyle swim | 100 | 4 | 90% | 400 | |||

| Interval | Interval Work ‐ Freestyle swim | 200 | 2 | 60% | 400 | |||

| Interval | Speed Work ‐ Freestyle Swim negative split | 400 | 1 | 70%‐90% | 400 | |||

| Interval Work ‐No breathing every 4th 25 | 25 | 16 | 60% | 400 | ||||

| Total | 4000 | |||||||

| Phase 2 | Week 5 | 10/30/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 400 | 1 | 400 | ||||

| Drill | Choice of drill | 50 | 4 | 200 | ||||

| Kick | Kick | 50 | 4 | 200 | ||||

| Interval | Interval Work | 250 | 4 | 70% | 1000 | |||

| Interval | Interval Work | 150 | 4 | 80% | 600 | |||

| Interval | Interval Work | 50 | 4 | 70% | 200 | |||

| Drill | Scull | 50 | 4 | 200 | ||||

| Interval | Interval Work with fins ‐ odds 25yd kick,25yd easy,25kick hard/evens 25yds underwater,25yd easy,25yds underwater | 75 | 10 | 70% | 750 | |||

| Drill | Interval Work ‐Breathing 3,5,7 by 50 yds | 300 | 2 | 80% | 600 | |||

| Total | 4150 | |||||||

| Phase 2 | Week 5 | 11/1/2013 | ||||||

| Warm‐up | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 400 | 1 | 400 | ||||

| Drill | Choice of drill | 50 | 4 | 200 | ||||

| Kick | Kick | 50 | 4 | 200 | ||||

| Interval | Interval Work | 250 | 4 | 80% | 1000 | |||

| Interval | Interval Work | 150 | 4 | 70% | 600 | |||

| Interval | Interval Work | 50 | 4 | 70% | 200 | |||

| Drill | Scull | 50 | 4 | 200 | ||||

| Interval | Interval Work with fins ‐ odds 25yd kick,25yd easy,25kick hard/evens 25yds underwater,25yd easy,25yds underwater | 75 | 10 | 80% | 750 | |||

| Drill | Interval Work ‐Breathing 3,5,7 by 50 yds | 300 | 2 | 70% | 600 | |||

| Total | 4150 | |||||||

| Phase 2 | Week 6 | 11/4/2013‐11/8/2013 | As above increasing to 4000 yards | 4000 | ||||

| Phase 2 | Week 7 | Warm‐up | 11/11/2013 | Warm‐up Freestyle Swim | 600 | 1 | 600 | |

| Drill | 25 yd Swim/25 yd Drill/ 50 yd Swim | 100 | 5 | 100 | ||||

| Kick | 50 yd swim/50 yd kick | 400 | 1 | 400 | ||||

| Drill | Drill ‐ count strokes per 25yds | 300 | 1 | 300 | ||||

| Drill | Drill ‐ focus on long push off wall following flipturn underwater | 200 | 1 | 200 | ||||

| Backstroke | 100 | 1 | 100 | |||||

| Interval | Interval Work | 50 | 16 | 70% | 400 | |||

| Kick | Kick | 75 | 8 | 80% | 600 | |||

| Drill | Freestyle with pull bouy breathing 3,5,7,5 by 25yd | 400 | 1 | 400 | ||||

| 3100 | ||||||||

Stroke Progression detailed in Table 6

Table 6.

Stroke Progression. Series of drills to focus on freestyle stroke technique used during warm‐up by Division III swimmer case example.

| 2×25 Right & Left kicking on side with arms at side |

| 4×25 Arms at side rotate every 6 kicks |

| 4×25 Right & Left kicking on side with arms extended |

| 4×25 6 Kicks right side with arm extended, 6 kicks left side arm extended |

| 4×25 6 Kicks on side with recovery (hold recovery 2 seconds, return arm to side, rotate to left side) |

| 2×50 6 kicks on right side, recover and rotate, 6 kicks on opposite side, recover and rotate |

| 2×50 3 full strokes followed by a full body freeze & glide to check and balance |

| 2×50 Swim normally |

| 250 10×25 ‐ using drills above |

| 100 Swim with perfect technique |

As the swimmer entered Phase Two, his practices consisted mostly of interval work. Yardage was slightly decreased (from 3750 yds to 2800 yds) to accommodate for the increase in intensity during week four. Entering week five, interval work became the primary focus, with drill work at the end of practice to remind the swimmer to focus on technique even when he was fatigued, as suggested within the RTSP. The swimmer was able to tolerate the progression well with his surgical shoulder, but complained of pain in his left shoulder in week six. Yardage was decreased and drill work became the main focus of the practices because this was the only way the swimmer could maintain “perfect stroke technique.” Reports from the coach noted the swimmer could tolerate practice as long as he used “perfect stroke technique.” Practices were adapted to be mostly drill work, but ultimately, the swimmer returned to the doctor for the pain and was diagnosed with a labral tear in the non‐involved left shoulder. At that time, his season ended. Feedback from the Certified Athletic Trainer and coach using the RTSP were positive. The coach reported the RTSP was easy to follow and the swimmer progressed well, aside from complications with the opposite shoulder.

SUMMARY

The RTSP was designed by the lead author who is a Certified Athletic Trainer, former NCAA Division I swimmer, and earned a PhD with an emphasis in biomechanics. The RTSP was inspired by conversations and interactions with colleagues working with injured swimmers. To date, it has been used by one NCAA Division III collegiate swimmer who was recovering from a closed, anterior Bankart repair, and has been shared among colleagues to use as proposed guidelines for a return to sport progression. While the evidence is limited regarding yardage based protocols for swimmers, the authors believe this program provides clinicians and coaches with a specific starting point to ease a swimmer back into practice. It does not address a swimmer's specialty (i.e. sprint or distance) because the first goal is to reestablish correct freestyle stroke technique, then increase endurance and training volume. The authors suggest that practices be tailored to a swimmer's specialty event or stroke once the swimmer has rejoined the team, and can practice pain free. Feedback from colleagues who have used the RTSP has been positive, but further research is needed in this area to support and refine the RTSP.

Appendix 1.

Commonly used swimming vocabulary with examples of how it is used

| Word | Definition | Example/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Base | The pace a swimmer or group of swimmer can swim 100 yards repeatedly and still finish with 5‐10 seconds rest. Allows practices to be more individualized. | 5×100 yards base (1:30) 5×100 yards base +5 (1:35) allows for more rest (easier) 5×100 yards base ‐5 (1:25) allows for less rest (harder) |

| Drills | Used to help swimmers focus on specific parts of the stroke cycle. They exaggerate one particular phase of the stroke. | Finger‐tip drag drill requires the swimmer to drag the finger tips on the top of the water during the recovery phase. This exaggerates the bent elbow to help the swimmer focus on proper recovery technique. |

| Distance Swimmer | A swimmer who competes in events that are over 500 yards/meters. | 500 yards/meters, 1000 yards/meters, 1650 yards/meters |

| Lap | 2 lengths = 50 yards/meters or 1 lap | If a swimmer is asked to swim a “50” that is 2×25 yards/meters of the pool |

| Length | Standard, short course, competition pools are either 25 yards or 25 meters long. 1 length = 25 yards or meters Length is more commonly used than Lap. | If a swimmer is asked to swim a “100” it means 4×25 yards/meters or 4 length of the pool continuously. |

| Long course | Olympic length 50 meter pool | If a swimmer is asked to swim 100 meters long course, it is 2 lengths of the pool. |

| Intensity | Used to describe the effort a swimmer is putting into each set throughout swim practice. It can be defined specifically using % of effort, but is commonly stated as “hard,” “moderate,” or “easy” on a written workout. | 5×100 yards 85% max effort Or 5×100 yards hard |

| Interval | Performing the distances in an allotted amount of time; the swimmer will only get rest if they can complete the distance before the defined interval time expires. | 5×100 yards freestyle 1:45 This means each 200 yard freestyle trial should be completed faster than 1 minute and 45 seconds for the swimmer to get rest. The faster the swimmer completes each 100 yard freestyle trial, the more rest he/she gets. |

| Kick | Focus on the kick component of the stroke using a kick board prone, in a streamlined position supine or on the side with one arm extended. | 5×100 kick w board Kick using a kickboard |

| Mid‐distance swimmer | A swimmer who competes in events between 200 yards and 500 yards long. | 200 yard freestyle, 500 yard freestyle |

| Negative Split | When the second half of a swimming event is faster than the first half of the swimming event | 200 yard freestyle 2:30 1st 100 yards 1:20 2nd 100 yards 1:10 |

| Pull | Focus on the arm component of the stroke using a pull buoy. Often hand paddles are used with the pull buoy during a pull set. This is not advised for an injured shoulder because the added resistance can exacerbate symptoms. | 5×100 pull w paddles Swim using a pull buoy and hand paddles |

| Rest | Time between each swim; Rest time means swimmers will always get a break between each swim. | 5×100 yards Rest 20 This means rest 20 sec after each 100 yard swim. |

| Scull | Moving hands and forearm out and in against the water | Commonly used as a drill to appreciate the feel of the water on the hand and forearm |

| Set | Refers to repetitions of defined distances and is written on a swimmers workout as —×— work‐out usually contains two‐four different sets. | 5×100 yard freestyle Means 4 lengths of freestyle repeated 5 times with either a rest or interval to determine recovery time. |

| Sprinter | A swimmer who competes in events 100 yards or less. | 100 yard freestyle, 50 yard freestyle |

| Swim | Performing one of the four competitive strokes | 5×100 free swim Swim freestyle |

| Stroke | Any of the 3 competitive swimming strokes besides Freestyle: Butterfly (fly), Backstroke ( back), Breaststroke (breast) | 5× 100 Fly Swim butterfly for all 100s |

| Yardage | Total yard or meters accumulated swimming during a set practice time. Verbalized by multiples of 25. | A coach may increase daily yardage from 3000 yards to 6000 yards over the course of the swim season. |

Italicized notations are what would be recorded in a workout log or record for each swimmer.

References

- 1.Sein ML Walton J, Linklater J, et al. Shoulder pain in elite swimmers: primarily due to swim‐volume‐induced supraspinatus tendinopathy. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010;44(2):105‐113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bak K Fauno P Clinical findings in competitive swimmers with shoulder pain. Am. J. Sports Med. 1997;25(2):254‐260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brushoj C Bak K Johannsen HV Fauno P Swimmers' painful shoulder arthroscopic findings and return rate to sports. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2007;17(4):373‐377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wanivenhaus F Fox AJ Chaudhury S Rodeo SA Epidemiology of injuries and prevention strategies in competitive swimmers. Sports health. 2012;4(3):246‐251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf BR Ebinger AE Lawler MP Britton CL Injury Patterns in Division I Collegiate Swimming. Am. J. Sports Med. 2009;37(10):2037‐2042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tate A Turner GN Knab SE Jorgensen C Strittmatter A Michener LA Risk Factors Associated With Shoulder Pain and Disability Across the Lifespan of Competitive Swimmers. J Athl Train. 2012;47(2):149‐158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beach ML Whitney SL Dickoff‐Hoffman SA Relationship of shoulder flexibility, strength, and endurance to shoulder pain in competitive swimmers. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1992;16(6):262‐268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrams GD Safran MR Diagnosis and management of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010;44(5):311‐318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pink MM Tibone JE The painful shoulder in the swimming athlete. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2000;31(2):247‐+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Axe M Hurd W Snyder‐Mackler L Data‐Based Interval Throwing Programs for Baseball Players. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2009:145‐153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escamilla RF Ionno M deMahy MS, et al. Comparison of three baseball‐specific 6‐week training programs on throwing velocity in high school baseball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012;26(7):1767‐1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fredericson M Cookingham CL Chaudhari AM Dowdell BC Oestreicher N Sahrmann SA Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2000;10(3):169‐175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaeding CC Yu JR Wright R Amendola A Spindler KP Management and return to play of stress fractures. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2005;15(6):442‐447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinold MM Wilk KE Reed J Crenshaw K Andrews JR Interval sport programs: Guidelines for baseball, tennis, and golf. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2002;32(6):293‐298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamman S Considerations and return to swim protocol for the pediatric swimmer after non‐operative injury. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014;9(3):388‐395 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olbrecht J Clarys JP EMG of specific strength training exercises for the front crawl. In: Hollander AP ed. Biomechanics and medicine in swimming: proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium of Biomechancis in Swimming and Fifth International Congress on Swimming Medicine. United States: Human Kinetics; 1983:136‐141 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JN Gauvin J Fredericson M Swimming biomechanics and injury prevention: new stroke techniques and medical considerations. Physician Sportsmed. 2003;31(1):41‐46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lintner D Noonan TJ Kibler WB Injury Patterns and Biomechanics of the Athlete's Shoulder. Clin. Sports Med. 2008;27(4):527‐551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pink M Perry J Browne A Scovazzo ML Kerrigan J The normal shoulder during freestyle swimming ‐ an electromyographic and cinematographic analysis of 12 muscles. Am. J. Sports Med. 1991;19(6):569‐576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben Kibler W Sciascia A Rehabilitation of the Athlete's Shoulder. Clin. Sports Med. 2008;27(4):821‐+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swanik KA Lephart SM Swanik B Lephart SP Stone DA Fu FH The effects of shoulder plyometric training on proprioception and selected muscle performance characteristics. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(6):579‐586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swanik KA Swanik CB Lephart SM Huxel K The effect of functional training on the incidence of shoulder pain and strength in intercollegiate swimmers. J. Sport Rehabil. 2002;11(2):140‐154 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kluemper M Uhl T Hazelrigg H Effect of stretching and strengthening shoulder muscles on forward shoulder posture in competitive swimmers. J. Sport Rehabil. 2006;15(1):58‐70 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carson PA The rehabilitation of a competitive swimmer with an asymmetrical breaststroke movement pattern. Man. Ther. 1999;4(2):100‐106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurtz JT A Chiropractic Case Report in the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Swimmer's Shoulder. J Chiropr. 2004;41(10):32‐38 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynch SS Thigpen CA Mihalik JP Prentice WE Padua D The effects of an exercise intervention on forward head and rounded shoulder postures in elite swimmers. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010;44(5):376‐381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarys JP Hydrodynamics and electromyography: ergonomics aspects in aquatics. Appl. Ergon. 1985;16(1):11‐24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heinlein SA Cosgarea AJ Biomechanical Considerations in the Competitive Swimmer's Shoulder. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2010;2(6):519‐525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Virag B Hibberd EE Oyama S Padua DA Myers JB Prevalence of freestyle biomechanical errors in elite competitive swimmers. Sports health. 2014;6(3):218‐224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson AB Jobe FW Collins HR The shoulder in competitive swimming. Am. J. Sports Med. 1980;8(3):159‐163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seifert L Chollet D Rouard A Swimming constraints and arm coordination. Human Movement Science. 2007;26(1):68‐86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson AB Jobe FW Collins HR The shoulder in competitve swimming. Am. J. Sports Med. 1980;8(3):159‐163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kendall FP Kendall FP Muscles : testing and function with posture and pain. 5th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005 [Google Scholar]