Abstract

Background

Families with a high incidence of hereditary breast cancer, and subsequently shown to have terminating mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 appear to have a higher incidence of prostate cancer among the male relatives. We aimed to determine whether the common germline mutations of BRCA1 or BRCA2 in Ashkenazi Jewish men predisposed them to prostate cancer.

Methods

We examined genomic DNA from 83 (for BRCA1 185delAG) or 82 (for BRCA2 6174delT) Ashkenazi Jewish prostate cancer patients, most of whom were treated at a relatively young age, for the most common germline mutation in each gene seen in the Ashkenazi population.

Results

Our study should be able to detect a four to five fold increase in the risk of prostate cancer due to mutation of BRCA1 or BRCA2. However, only one (1.15%, 95% CI 0-3.6%) of the patients was heterozygous for the BRCA1 mutant allele, and only two were heterozygous for the BRCA2 mutation (2.4%, 95% CI 0-6.2%).

Conclusions

The incidence of each of the germline mutations in these prostate cancer patients closely matched their incidence (about 1%) in the general Ashkenazi Jewish population. This suggests that unlike the cases of breast and ovarian cancers, mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 do not significantly predispose men to prostate cancer.

Keywords: risk, gene, breast, neoplastic, heterozygote

INTRODUCTION

Studies have suggested linkage between breast and ovarian cancer in families carrying germline mutations of BRCA1 or BRCA2 and prostate cancer in male relatives _(1-4)_. With the advent of genetic testing among vulnerable populations for mutations in these genes, it is increasingly important to define the level of risk for prostate cancer for the relatives of BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygotes. LOH, consistent with tumor suppressor gene inactivation in somatic cells, is found in prostate cancers at both 17q, the location of BRCA1 _(5-7)_, and 13q, the site of BRCA2 and Rb _(8-10)_. In addition, the region lost on 17q _(11, 12)_ suppresses the malignant phenotype of a prostate cancer cell line _(13)_. BRCA1 is mutated in up to 2% of Ashkenazi Jews, with a terminating mutation in exon 2 (185delAG) accounting for >50% of the deleterious changes _(1, 14, 15)_. For BRCA2, the principal deleterious mutation (6174delT) occurs in ~1% of Ashkenazim _(1, 15-17)_. Mutation in either gene is believed to confer an 80-90% lifetime risk of breast cancer in affected families _(18, 19)_, although a recent article suggests the risk may be as low as 50% _(1)_. To test whether germline mutation of either BRCA gene correlates with an increased risk of prostate cancer, we examined non-neoplastic tissue from relatively young Ashkenazi men treated for prostate cancer for the presence of the BRCA1 185delAG or the BRCA2 6174delT alleles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Archival records from both the New York University and Columbia Presbyterian medical centers from 1991 to 1996 were examined for young prostate cancer patients with traditional Eastern European Jewish surnames. The population dynamics of Jewish New Yorkers born between 1920 and 1950 strongly suggests that these individuals are of Ashkenazic heritage. Patients with surnames which might indicate either a Sephardic or Ashkenazic heritage were eliminated from the analysis. Non-tumor tissue (principally lymph nodes), formalin fixed and embedded in paraffin, was retrieved for 83 cases of stage B prostate cancer, assigned to age bins (under 40, 40-50, 50-60, and over 60), and anonymized (see Table 1). Genomic DNA was isolated from sections cut from the paraffin blocks by xylene extraction, ethanol washing, and then processing using a tissue DNA isolation kit (Qiagen). The DNA was PCR amplified by 45 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds; 53 to 59°C for two minutes; and 72°C for one minute. One of these cases failed to amplify using the BRCA2 primers and so was excluded from the analysis. The primers to amplify the BRCA1 185delAG region are:

Table 1.

Age and genotype distribution of prostate cancer patients

| Age Bin | Total BRCA1 | 185delAG | Total BRCA2 | 6174delT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 41-50 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| 51-60 | 48 | 1 | 47 | 2 |

| >60 | 26 | 0 | 26 | 0 |

| Total | 83 | 1 | 82 | 1 |

primer pair A, forward: GAAGTTGTCATTTTATAAACCTTT,

reverse: TGTATGATCCCTTCTTTTCTG;

primer pair B, forward: TTCTAATGTGTTAAAGTTCATTGG,

reverse: TACGTTTACTTGTCTTAACTGGAA;

primer pair C, forward: GGTTTGTATCATTCTAAAACC,

reverse: CCGATAACATTAACGACTAAA.

The primers to amplify the BRCA2 6174delT region are:

primer pair A, forward: GTCTGGATTGGAGAAAGTTT,

reverse: AAGTCTGGTCGAGTGTTCTC;

primer pair B, forward: ATCACCTTGTGATGTTAGTTTGG,

reverse: CCATAGTCTACGAAGTATGTTT;

primer pair C, forward: GATAATGATGAATGTAGCACGC,

reverse: GCAAGTGGAAAGCAAGTTTCCA.

Presence of the mutant alleles was detected by heteroduplex analysis (HDA) of the PCR products _(20)_. Briefly, PCR reactions were heated to 98°C for five minutes, cooled to 30°C over ninety minutes, separated on gradient four to twenty percent polyacrylamide, TBE gels (Novex), and stained with ethidium bromide. The amplification products of primer pair A for either BRCA1 or BRCA2 from selected patient samples were sequenced from the nested (primers B, forward, see Figures 1 and 2) primer for each on an ABI 373A sequencer at the Columbia University Cancer Center.

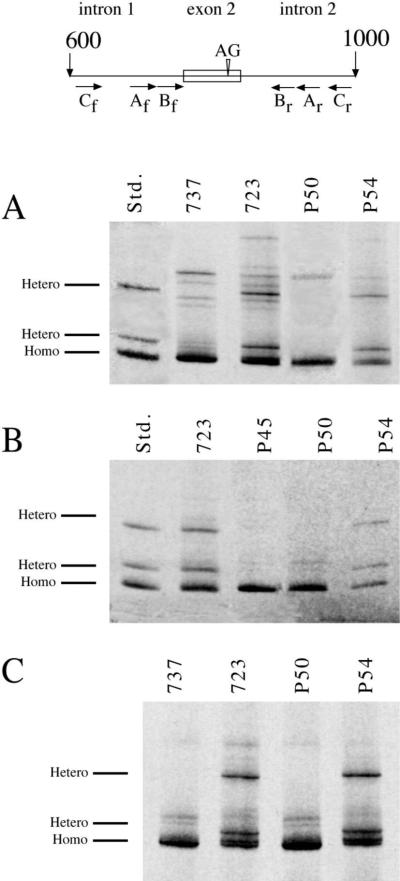

Fig. 1.

BRCA1 185delAG mutation screen. Top-Schematic diagram of the region of the BRCA1 gene surrounding the 185delAG mutation, with exon 2 indicated by the box and the site of the deletion indicated by the inverted triangle. PCR primer pair locations are indicated below (f: forward, r: reverse). Numbering refers to base pairs from the transcription start site of the cDNA (from GENBANK U14680). Shown are ethidium stained gels of HDA using (A) primer pair A (amplicon length = 237 bp), (B) primer pair B (188 bp), and (C) primer pair C (375 bp).

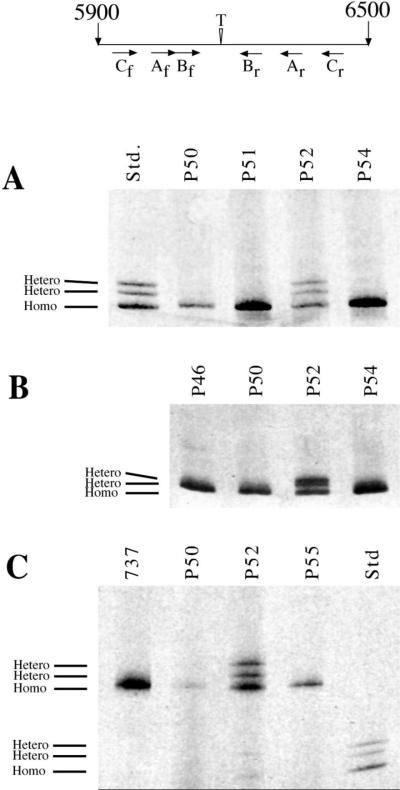

Fig. 2.

BRCA2 6174delT mutation screen. Top-Schematic diagram of the region of the BRCA2 gene surrounding the 6174delT mutation (exon 11), with the site of the deletion indicated by the inverted triangle. PCR primer pair locations are indicated below (f: forward, r: reverse). Numbering refers to base pairs from the transcription start site (from GENBANK U43746). Shown are ethidium stained gels of HDA using (A) primer pair A (275 bp), (B) primer pair B (149 bp), and (C) primer pair C (477).

Ninety-five percent confidence limits were calculated for the carrier frequencies assuming that the number of positives follow a Poisson distribution. The Poisson distribution was selected for statistical analyses due to the rarity of the mutations.

RESULTS

BRCA1

Fifty seven young (less than 60 years at prostatectomy) prostate cancer patients and twenty six older patients were screened for germline deletion of 185AG in BRCA1 (Table 1). Genomic DNA was PCR amplified using primers flanking exon 2 (primer pair A, Fig. 1). After HDA only one of the samples from patients who underwent prostatectomy before age 60, and none from older patients, showed heteroduplex formation (lane P54 in Fig. 1A). Equivalently retarded bands appear in genomic DNA amplified from non-neoplastic tissues of an individual heterozygotic for the 185delAG mutation (_(20)_; lane 723 in Fig. 1A), but not in DNA known to be homozygous wild-type (lane 737 in Fig. 1A). The retardation of the heteroduplex bands relative to the homozygous band (“homo” in Fig. 1A) was identical for the patient samples and an equimolar mixture of PCR products amplified from BRCA1 mutant and normal plasmids constructed previously _(20)_. Heteroduplex formation was confirmed by PCR-HDA using nested primers (primer pair B, Fig. 1B). Finally, to eliminate any possibility of plasmid or PCR product contamination, the PCR-HDA was performed with flanking primers complimentary to an area not represented in any of our cloned or previously amplified DNA. Only the positive control (723) and sample P54 generated heteroduplexes (primer pair C, Fig. 1C). The positive and an additional four negative genomic DNA samples were sequenced. Each of the negative DNAs generated unambiguous sequence corresponding to that reported in GENBANK, while the sample which gave heteroduplex bands (P54) produced unambiguous sequence up to the point of the deletion, whereupon the sequence became degenerate exactly in accord with the expected result of a two bp deletion in one allele, and as seen in the known heterozygote, sample 723 (data not shown).

BRCA2

Fifty six young (less than 60 years old at prostatectomy) patients and twenty six older patients were screened for germline deletion of 6174T in BRCA2 (Table 1). A PCRHDA completely analogous to that employed for detecting the BRCA1 mutation was carried out on these 82 samples (see schematic at the top of Fig. 2). Equimolar amounts of PCR products from BRCA2 wild type and 6174delT mutant plasmids were used as standards since we had not previously identified any heterozygotic patient samples to use as a control (std in Fig. 2A and C). Two samples (cases P52 and P61) showed heteroduplex formation with each primer pair (P52 shown in Fig. 2A, B, and C). PCR product from each sample was sequenced, and as was the case for BRCA1, the resulting sequence was unambiguous up to the point of the mutation, whereupon it showed the multiple peaks in the electropherogram expected to result from a one base pair deletion in one allele (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Several studies have suggested an increased risk of prostate cancer among male relatives in families with a high incidence of breast and/or ovarian cancer who are heterozygotic for termination mutations in either BRCA1 or BRCA2. In 33 families with linkage to BRCA1. Ford et al. _(2)_ found a significant increase in prostate cancer among BRCA1 heterozygotes (relative risk 3.33). Phelan et al. _(21)_ report a relative risk of 4.22 for developing prostate cancer in families who had mutations in BRCA2. In a smaller number of families, Easton et al., estimate a relative risk of 2.89 _(22)_ Among first degree relatives in Icelandic families with a terminating mutation in BRCA2, Sigurdsson et al., estimate a relative risk of 4.6 _(23)_. In contrast, among women with mutations in BRCA1, FitzGerald, et al., _(24)_ found a 27-fold increase in the relative risk of early onset breast cancer. In their recent report, Struewing, et al. _(1)_ examined a self-identified population of Ashkenazim which had a disproportionate number of subjects with family histories of cancer. Among 380 reported incidences of first degree relatives with prostate cancer, 5 are from subjects heterozygotic for BRCA1 185delAG and 6 from for BRCA2 6174delT heterozygotes. From these groups they estimate the risk of prostate cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygotes and report little estimated risk before age 50, but estimate a 25% (for BRCA1 heterozygotes) or 5% (for BRCA2 heterozygotes) risk at the age of 70, while the estimated risk for non-carriers is only 4%.

The cancer-prone families may have other genetic defects which contribute to the increase in relative risk, and the risk estimates of Struewing et al. _(1)_ are based on a small number of reports of relatives who have not been directly genotyped. To avoid these confounding influences, we examined younger Ashkenazi prostate cancer patients, regardless of family history, for evidence of an increase in the frequency of mutant germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 alleles. A previous, smaller study of BRCA1 in younger prostate cancer patients of unknown genetic background was inconclusive _(25)_. In a study of approximately 3000 U.S. Ashkenazi individuals who were unselected for a personal or family history of cancer, the carrier frequency of the BRCA1 185delAG mutation was found to be 1.15% (95% confidence limit, based on the Poisson distribution, = 0.78-1.63%) _(15)_. The corresponding prevalence of BRCA1 185delAG in our study is 1.2% (0-3.6%). While we have not directly estimated the frequency of the 185delAG mutation in the Ashkenazi population treated in our hospitals, we can estimate, using the general Ashkenazi population value (above), that if BRCA1 185delAG increases the relative risk four fold, we would expect to find 4 patients among our sample of 84. However, we find only one patient (0-3) with the 185delAG mutation among 83 with predominantly early onset prostate cancer, in line with the expected value if there is no increase the in relative risk of prostate cancer among carriers.

Inactivation of BRCA2 by the 6174delT mutation occurs in 1.38% (0.97-1.9%) of the Ashkenazi Jewish population _(15)_. If we again use the general population values for the frequency of BRCA2 6174delT, and there is no increase in relative risk for our sample of prostate cancer cases, we expect only 1 (0-3) positive sample. Instead, we found 2 (0-5) heterozygotes among the 83 patients analyzed, a frequency of 2.4% (0-6.2%). If the 6174delT mutation increased the relative risk of prostate cancer in our sample five fold, we would expect to see 6 or more BRCA2 6174delT carriers, rather than the 2 heterozygotes we observed. Among Icelanders, a terminating mutation (999del5) of BRCA2 occurs in 0.4% of the population. For Icelandic prostate cancer patients diagnosed at less than 65 years of age, and chosen without regard to family history of breast and ovarian cancers, 2.7% (2 of 75) had the terminating mutation, but the authors were unable to draw firm conclusions due in part to the small sample population used to determine the mutant allele frequency among the general Icelandic population _(18)_.

It is expected that germline terminating mutations of BRCA1 or BRCA2 should predispose to early onset prostate cancer, as is seen for breast cancer. For example, BRCA1 is mutant in 21% of Ashkenazi women under 41 with breast cancer _(24)_, while BRCA2 is mutant in 8% of Ashkenazi women under 43 with breast cancer _(26)_. These values are in line with the estimates reported in Struewing, et al. _(1)_. Most cases of prostate cancer are diagnosed after the age of 70 _(27)_. Since our sample was heavily skewed towards younger patients whose incidence of prostate cancer is akin to women under 45, our analysis should overestimate the influence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 terminating mutations on the incidence of prostatic carcinoma. A recent, analogous examination of the influence of the ATM gene on early onset breast cancer similarly found no increase in relative risk _(28)_. Furthermore, our study strongly suggests that the LOH of the BRCA1 _(5-7)_ and BRCA2 _(8-10)_ loci in sporadic prostate cancer is likely to be related to other, nearby genes rather than the loss of either BRCA gene. For example BRCA2 loss rarely occurs independently of Rb gene loss _(9, 29)_, and when it does occur, there does not appear to be mutation of the other allele _(30)_, and the loss seen on 17q appears to be slightly distal to the BRCA1 locus _(11)_ . Knowledge that germline mutations in particular cancer predisposition genes do not contribute to the pathogenesis of some cancers is essential to provide accurate genetic counseling to cancer-prone families.

Very recently, Lehrer, et al. _(31)_ published a very similar study of a smaller number of prostate cancer patients. They examined 60 men with prostate cancer who self-identified as Ashkenazim for both BRCA1 185delAG and BRCA2 6174delT. None of the samples of normal tissue from these patients showed heterozygosity at either locus. While the mean age of their patient sample was older than in our population (70.5 v approximately 55), the finding of no mutations further reinforces our results.

In summary, we found similar estimates of mutant alleles as those found in a general population of Ashkenazi Jews _(15)_. A much larger study of young Ashkenazi prostate cancer patients will be needed to rule out smaller increases in relative risk, and any possible influence of the three-fold less frequent BRCA1 5382insC mutation. Even though our patient sample was small, we should have been able to detect a risk of fourfold or greater for BRCA1 or five fold for BRCA2 when compared to this general Ashkenazi population _(15)_. In addition, both the younger median age of the patients in our study population, and the LOH dissociation of the BRCA genes in sporadic cancers, strengthen our contention that mutations in either of these genes are not likely to predispose men to prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PHS Grant numbers CA 56862 and CA 66224

REFERENCES

- 1.Struewing JP, Hartge P, Wacholder S, Baker SM, Berlin M, McAdams M, Timmerman MM, Brody LC, Tucker MA. The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. 336. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997:1401–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705153362001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford D, Easton DF, Bishop DT, Narod SA, Goldgar DE, the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium Risks of cancer in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Lancet. 1994:343, 692–695. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arason A, Barkardóttir RB, Egilsson V. Linkage analysis of chromosome 17q markers and breast-ovarian cancer in Icelandic families, and possible relationship to prostatic cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;52:711–717. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman LS, Szabo CI, Ostermeyer EA, Dowd P, Butler L, Park T, Lee MK, Goode EL, Rowell SE, King M-C. Novel inherited mutations and variable expressivity of BRCA1 alleles, including the founder mutation 185delAG in Ashkenazi Jews. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;57:1284–1297. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brothman AR, Steele MR, Williams BJ, Jones E, Odelberg S, Albertsen HM, Jorde LB, Rohr LR, Stephenson RA. Loss of chromosome 17 loci in prostate cancer detected by polymerase chain reaction quantitation of allelic markers. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 1995;13:278–284. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870130408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao X, Zacharek A, Salkowski A, Grignon DJ, Sakr W, Porter AT, Honn KV. Loss of heterozygosity of the BRCA1 and other loci on chromosome 17q in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1002–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ittmann MM. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosomes 10 and 17 in clinically localized prostate carcinoma. The Prostate. 1996;28:275–281. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(199605)28:5<275::AID-PROS1>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gudmundsson J, Johannesdottir G, Bergthorsson JT, Arason A, Ingvarsson S, Egilsson V, Barkardottir RB. Different tumor types from BRCA2 carriers show wild-type chromosome deletions on 13q12-q13. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4830–4832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooney KA, Wetzel JC, Merajver SD, Macoska JA, Singelton TP, Wojno KJ. Distinct regions of allelic loss on 13q in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1142–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ittmann MM, Wieczorek R. Alterations of the retinoblastoma gene in clinically localized, stage B prostate adenocarcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 1996;27:28–34. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams BJ, Jones E, Zhu XL, Steele MR, Stephenson RA, Rohr LR, Brothman AR. Evidence for a tumor suppressor gene distal to BRCA1 in prostate cancer. J. Urol. 1996;155:720–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao X, Zacharek A, Grignon DJ, Sakr W, Powell IJ, Porter AT, Honn KV. Localisation of potential tumor suppressor loci to a <2 Mb region on chromosome 17q in human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 1995;11:1241–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murakami YS, Brothman AR, Leach RJ, White RL. Suppression of malignant phenotype in a human prostate cancer cell line by fragments of normal chromosome region 17q. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3389–3394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Struewing JP, Abeliovich D, Peretz T, Avishai N, Kaback MM, Collins FS, Brody LC. The carrier frequency of the BRCA1 185delAG mutation is approximately 1 percent in Ashkenazi Jewish individuals. Nat. Genet. 1995;11:198–200. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roa BB, Boyd AA, Volcik K, Richards CS. Ashkenazi Jewish population frequencies for common mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:185–187. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J, Collins N, Gregory S, Gumbs C, Micklem G, Barfoot R, Hamoudi R, Patel S, Rice C, Biggs P, Hashim Y, Smith A, Connor F, Arason A, Gudmundsson J, Ficenec D, Kelsell D, Ford D, Tonin P, Bishop DT, Spurr N, Ponder BAJ, Eeles R, Peto J, Devilee P, Cees C, Lynch H, Narod S, Lenoir G, Egilsson V, Barkadottir RB, Easton DF, Bentley DR, Futreal PA, Ashworth A, Stratton MR. Identification of the cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378:789–791. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oddoux C, Struewing JP, Clayton CM, Neuhausen S, Brody LC, Kaback M, Haas B, Norton L, Borgen P, Jhanwar S, Goldgar D, Ostrer H, Offit K. The carrier frequency of the BRCA2 6174delT mutation among Ashkenazi Jewish individuals is approximately 1%. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:188–190. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johannesdottir G, Gudmundsson J, Bergthorsson JT, Arason A, Agnarsson BA, Eiriksdottir G, Johannsson OT, Borg A, Ingvarsson S, Easton DF, Egilsson V, Barkardottir RB. High prevalence of the 999del5 mutation in Icelandic breast and ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3663–3665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop TD, the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;56:265–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mansukhani M, Nastiuk KL, Hibshoosh H, Kularatne P, Russo D, Krolewski JJ. Convenient, non-radioactive, heteroduplex-based methods for identifying recurrent mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Diag. Mol. Pathol. 1997;6:229–237. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phelan CM, Lancaster JA, Tonin P, Gumbs C, Cochran C, Carter R, Ghadirian P, Perret C, Moslehi R, Dion F, Faucher M-C, Dole K, Karimi S, Foulkes W, Lounis H, Warner E, Goss P, Anderson D, Larsson C, Narod SA, Futreal PA. Mutation analysis of the BRCA2 gene in 49 site-specific breast cancer families. Nat. Genet. 1996;13:120–122. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Easton DF, Steele L, Fields P, Ormiston W, Averill D, Daly PA, McManus R, Neuhausen SL, Ford D, Wooster R, Cannon-Albright LA, Stratton MR, Goldgar DE. Cancer risks in two large breast cancer families linked to BRCA2 on chromosome 13q12-13. Amer. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:120–128. doi: 10.1086/513891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigurdsson S, Thorlacius S, Tomasson J, Tryggvadottir L, Benedictsdottir K, Eyfjord JE, Johsson E. BRCA2 mutation in Icelandic protate cancer patients. J. Mol. Med. 1997;75:758–761. doi: 10.1007/s001090050162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.FitzGerald MG, MacDonald DJ, Krainer M, Hoover I, O'Neil E, Unsal H, Silva-Arrieto S, Finkelstein DM, Beer-Romero P, Englert C, Scroi DC, Smith BL, Younger JW, Garber JE, Duda RB, Mayzel KA, Isselbacher KJ, Friend SH, Haber DA. Germ-line BRCA1 mutations in Jewish and non-Jewish women with early-onset breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334:143–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601183340302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langston AA, Stanford JL, Wicklund KG, Thompson JD, Blazej RG, Ostrander EA. Germ-line BRCA1 mutations in selected men with prostate cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;58:881–885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuhausen S, Gilewski T, Norton L, Tran T, McGuire P, Swensen L, Hampel H, Borgen P, Brown K, Skolnick M, Shattuck-Eidens D, Jhanwar S, Goldgar D, Offit K. Recurrent BRCA2 6174delT mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish women affected by breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 1996;13:126–128. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gittes RF. Carcinoma of the prostate. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;324:1892–1893. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101243240406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.FitzGerald MG, Bean JM, Hegde SR, Unsal H, MacDonald DJ, Harkin DP, Finkelstein DM, Isselbacher KJ, Haber DA. Heterozygous ATM mutations do not contribute to early onset of breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:307–310. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melamed J, Einhorn JM, Ittmann MM. Allelic loss on chromosome 13q in human prostate cancer. 1997 submitted. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Larsson C, Futreal A, Lancaster J, Phelan C, Aspenblad U, Sundelin B, Liu Y, Ekman P, Auer G, Bergerheim USR. Identification of two distinct deleted regions on chromosome 13 in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 1998;16:481–487. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehrer S, Fodor F, Stock RG, Stone NN, Eng C, Song HK, McGovern M. Absence of 185delAG mutation of the BRCA1 gene and 6174delT mutation of the BRCA2 gene in Ashkenazi Jewish men with prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;78:771–3. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]