Abstract

Gastritis is a major disease that has the potential to grow as gastric cancer. Gastric cancer is a very common cancer, and it is related to a very high mortality rate in Korea. This disease is known to have various reasons, including infection with Helicobacter pylori, dietary habits, tobacco, and alcohol. The incidence rate of gastritis has reported to differ between age, population, and gender. However, unlike other factors, there has been no analysis based on gender. So, we examined the high risk factors of gastritis in each gender in the Korean population by focusing on sex. We performed an analysis of 120 clinical characteristics and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) using 349,184 single-nucleotide polymorphisms from the results of Anseong and Ansan cohort study in the Korea Association Resource (KARE) project. As the result, we could not prove a strong relation with these factors and gastritis or gastric ulcer in the GWAS. However, we confirmed several already-known risk factors and also found some differences of clinical characteristics in each gender using logistic regression. As a result of the logistic regression, a relation with hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, hyperlipidemia therapy, hypotensive or antihypotensive drug, diastolic blood pressure, and gastritis was seen in males; the results of this study suggest that vascular disease has a potential association with gastritis in males.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, gastric ulcer, GWAS, hyperlipidemia, myocardial infarction, vascular disease

Introduction

Gastric cancer is a common cancer type. In the world, this cancer type has the second highest incidence among males and third highest among females [1]. In Korea, the incidence rate of gastric cancer was second highest, and the mortality rate of gastric cancer was third highest among all cancer types in a 2010 Korean cancer statistics study [2].

The incidence rate of gastric cancer differs between patient age, location, and even sex [3], because gastric cancer has various subtypes [3, 4] and a lot of risk factors [5]. Helicobacter pylori is known for having a relation with gastric cancer [6]. Almost all gastric cancer patients are infected with H. pylori [3]. As known before, dietary habits also have the potential to affect gastric cancer [1]. The incidence risk factors have differences in gastric cancer or peptic ulcers by blood type [7] and sex [8]. Gastric cancer type also depends on patient populations or race [5]. So, an analysis is needed to find known and unknown risk factors in diverse phenotypes [3]. Gastritis is related with gastric cancer. Chronic gastric inflammation has the potential to grow into gastric cancer [9].

Many risk factors are related with gastritis, as already reported. However, even though gender is known to be associated with gastritis infraction, there is not much information about the effects on gastritis depending on gender. So, we examined Korean risk factors of gastritis and gastric ulcer using genotypes and clinical characteristics of patients who were diagnosed with gastritis or gastric ulcer in each gender. For revealing the correlation with gastritis and known and unknown risk factors, we analyzed single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and epidemiological data of the Korea Association Resource (KARE) project, which comprised the results of the Anseong and Ansan cohorts study.

Methods

Clinical characteristics and study genotypes

This study analyzed cohort data that comprised the Anseong and Ansan population study in the KARE projects. Anseong is a rural area, and Ansan is a city. Both areas are in Gyeonggi-do. Citizen of these two cities have different lifestyles, and they are exposed to different environment. Detailed information of the KARE data was reported [10]. The KARE data included 8,842 individuals, 352,228 SNPs, and 277 phenotypes.

Among 8,842 total individuals, we divided patients and normal subjects for a control and case study using a positive diagnosis experience of gastritis. There were 1,885 patients and 6,957 normal subjects. First, for selecting the case, we eliminated 104 patients who were diagnosed under age 20 or had unknown age. Then, 1,781 patients remained. Of these, 804 patients were men, and 977 patients were women. Of 6,957 normal subjects, no one was aged under 20; 3,335 were men, and 3,622 were women.

Among 352,228 SNPs, we excluded 3,044 SNPs based on the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test for quality control. After frequency and genotyping pruning, 349,184 SNPs remained.

Among 277 total phenotypes, we filtered missing phenotypes and low genotyping rates. Then, 120 clinical characteristics remained. We also eliminated gastritis phenotype variables and unknown drug information variables; 101 clinical characteristics remained.

Statistical analysis

For data filtering and finding significant SNPs, we used PLINK version 1.07, that is a tool made for analyzing whole-genome association using computational methods [11]. We used the default options of PLINK [11], and we analyzed phenotypes by logistic regression test for classifying patients and normal subjects and estimating factors. We also assessed the result factors of the logistic regression by Student's t-test for revealing meaningful differences between patients and normal subjects using R version 3.0.2 for finding gastritis-associated factors. Then, we used the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the curve (AUC) scores to confirm the prediction ability of the factors.

Results

Clinical characteristics

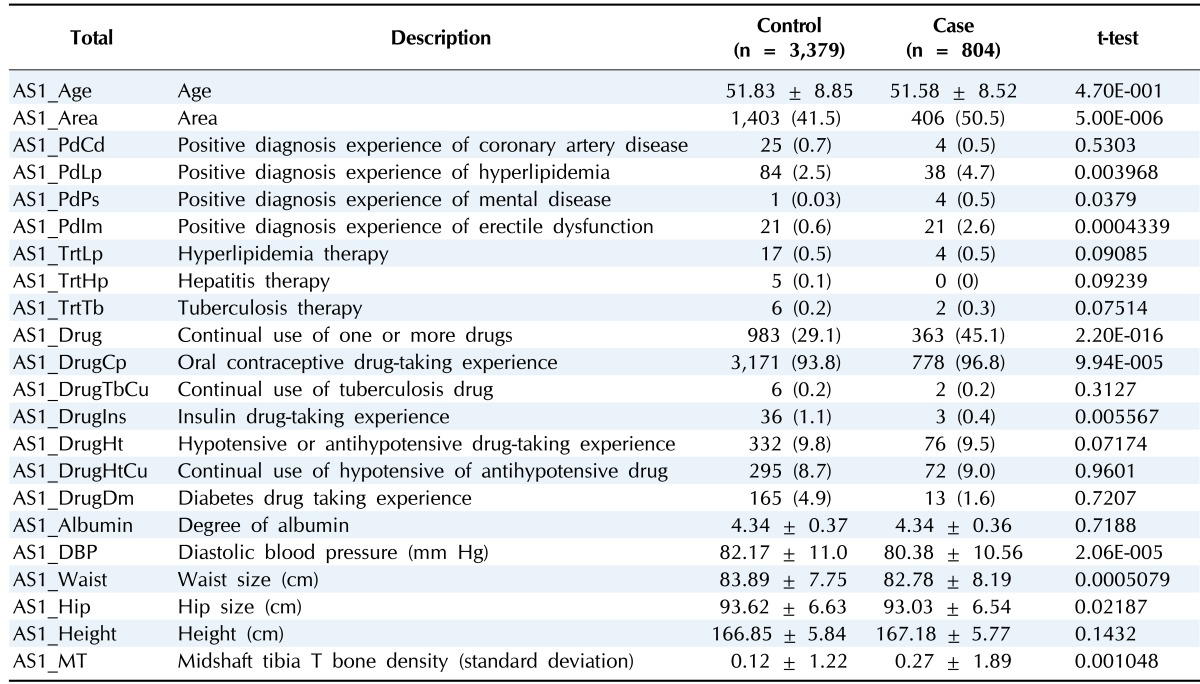

Tables 1 and 2 explain the results of the logistic regression test among total clinical characteristics in each gender. There were differences in gender-specific clinical characteristics. Among 1,781 total patients, 977 patients and 804 patients were male and female, respectively. Patients had several disease-association factors in both genders: area, positive diagnosis of hyperlipidemia, positive diagnosis of mental disease, continual use of one or more drugs, waist, and height.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of gastritis variables in male

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

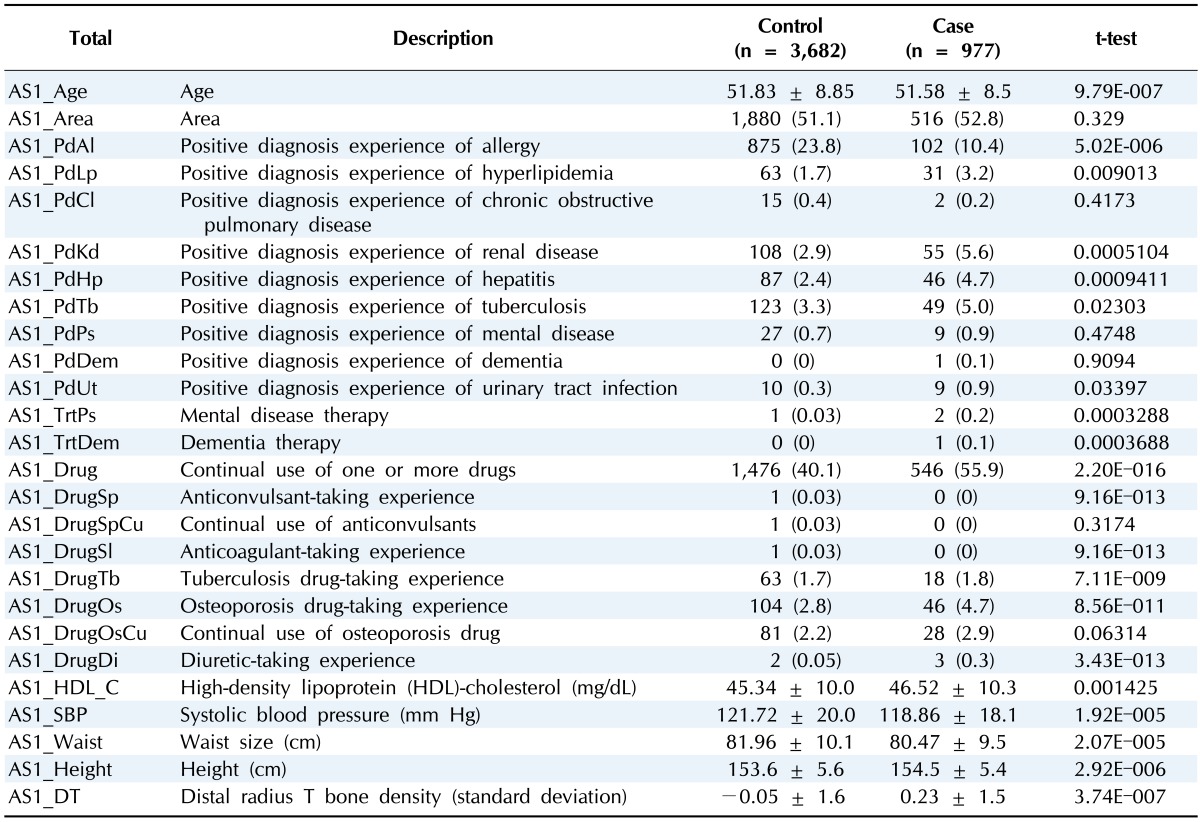

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of gastritis variables in female

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

Through previous studies, how these factors are related with gastritis was verified.

The incidence of gastritis is affected by population, geographic variation, or lifestyle [1, 5]. In this study, we used cohort data that comprised country and city populations. As shown Tables 1 and 2, in both genders, the population of local A had a higher gastritis incidence rate. This means that differences in patient lifestyle and environment affect the disease incidence rate.

It is well known that stress has an influence on carcinogenesis. A study reported that gastritis is closely connected with mental illness [12] and differs in degree according to drug use-taking medicine affects the stomach. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can cause gastrointestinal damage [13].

Losing appetite is the one of phenotypes of gastritis that are connected with waist size or hip size as gastritisassociated factors. However, definite evidence is lacking [14]. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, we can explain the associative relation that waist size or hip size is smaller despite patients being taller than normal. Also, height is considered to be a gastritis risk factor. As shown in a previous study, higher height tends to increase the gastric cancer incidence rate [15].

In males and females, hyperlipidemia and gastritis are related with gastritis. Only male cases are associated with vascular disease. Coronary artery has the potential to grow into myocardial infarction [16], and myocardial infarction is related with blood pressure [17]. As previously reported, approximately 30% of patients with coronary heart disease suffer from hyperlipidemia at the same time [18]. So, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery, and myocardial infarction are all related to each other. As shown in Table 1, in males, by logistic regression, there is a relation with hyperlipidemia, coronary artery, myocardial infarction, hyperlipidemia therapy, hypotensive or antihypotensive drug use, and diastolic blood pressure. This relation is more remarkable in males than in females. Repeatedly, it can be considered that vascular disease is connected with gastritis. In fact, in this study, including males and females, 16 patients had gastritis and myocardial infarction (20%), 77 patients had gastritis and hyperlipidemia (36%), and 13 patients had gastritis and coronary artery (25.5%).

Female patients with gastritis have 4 more gastritis-associated factors by logistic regression test compared with males. In the case of taking osteoporosis medicine, the incidence rate is 1.7 times higher compared with normal. Taking anticonvulsants is a meaningful factor by logistic regression test, but few patients were taking this medicine [4]; so, it is hard to prove that taking anticonvulsants has a positive relation with gastritis. Patients who were diagnosed with tuberculosis and patients who have taken tuberculosis drugs suffer gastritis more than normal subjects. This gives information on the relation between gastritis and tuberculosis in females.

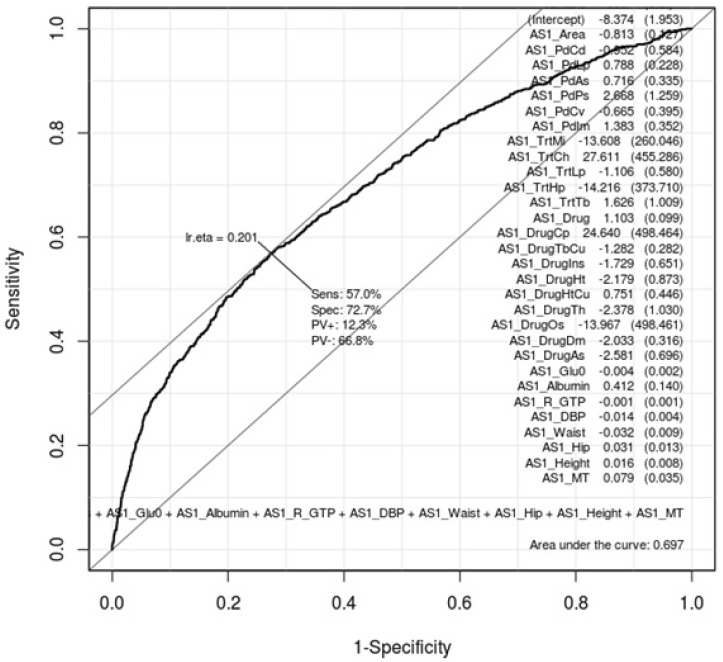

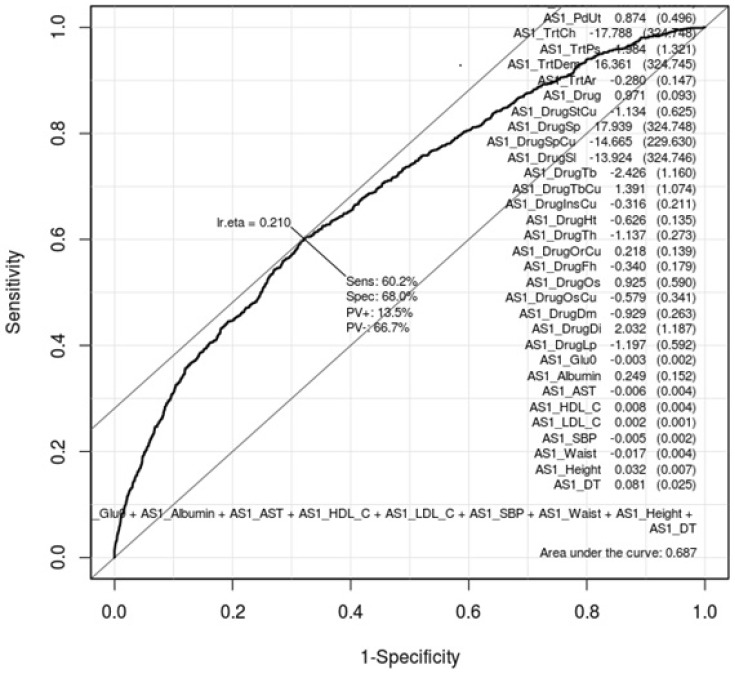

ROC curves can show how gastritis-associated factors of Tables 1 and 2 affect gastritis patients and normal subjects. Whether these factors are conclusive should be confirmed by AUC values. Figs. 1 and 2 are ROC curves using the result of the logistic regression test of Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Each AUC value is 0.697 and 0.687. This result means that these factors are not useful as gastric-specific markers.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of gastritis-associated factors in males. This shows how well the 22 gastritis-associated clinical characteristic factors (Table 1) classify patients and normal subjects in males. As much as the ROC curve, these factors can classify gastritis patients and normal subjects in males.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of gastritis-associated factors in females. This shows how well the 26 gastritis-associated clinical characteristic factors (Table 2) classify patients and normal subjects in females. As much as the ROC curve, these factors can classify gastritis patients and normal subjects in females.

Genome-wide association studies

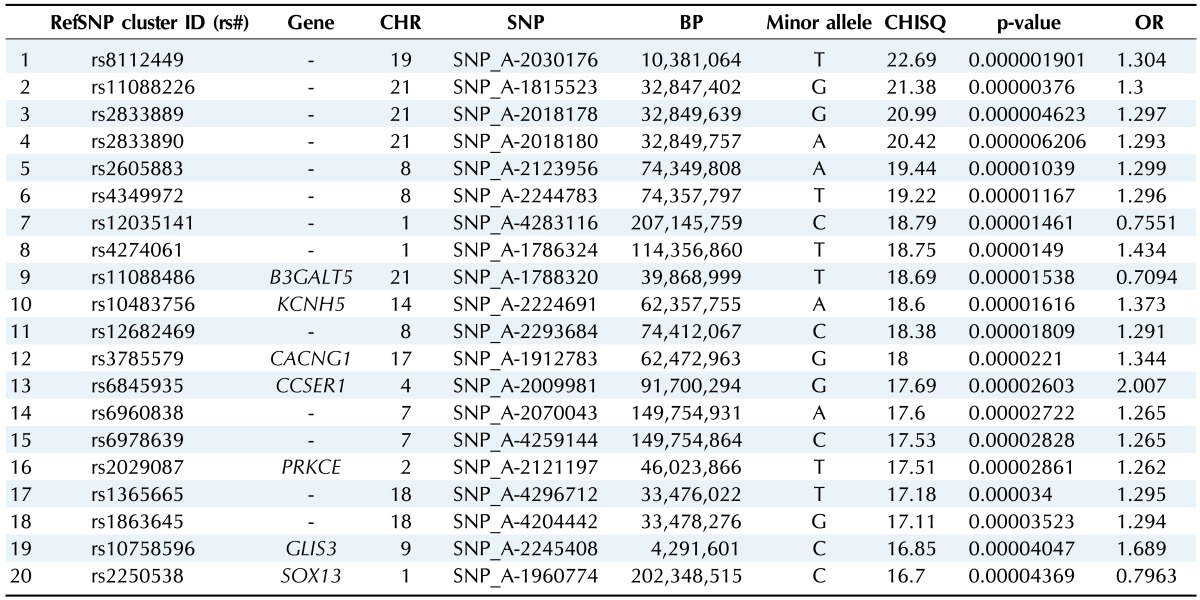

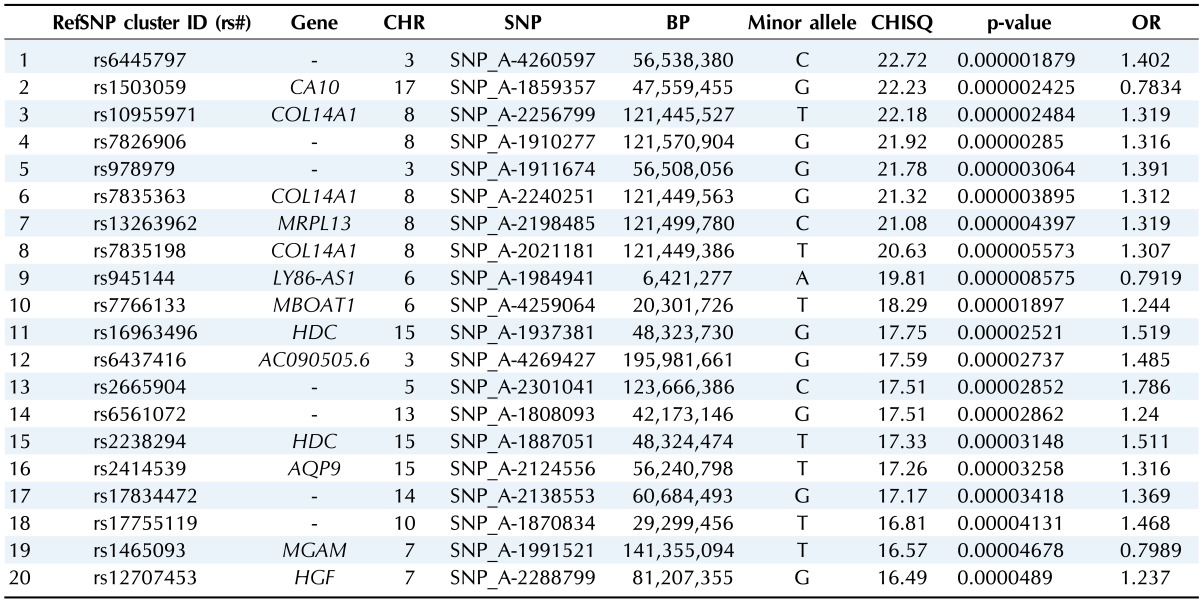

We selected the top 20 ranked SNPs by association test using chi-square test and p-values among 349,184 SNPs in males and in females, respectively. The results of SNPs association analysis described in Tables 3 and 4. Tables 3 and 4 are top 20 ranked SNPs of genomewide association analysis in males and females, respectively. They are sorted by P-value. But there was no considerable SNP associated with gastritis. Astonishingly, there was no common SNP between males and females. This means that associated-SNPs are different, depending on the patient's gender.

Table 3.

Top 20 ranked SNPs of genomewide association analysis in males

SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; CHR, chromosome; BP, base pair; OR, odds ratio.

Table 4.

Top 20 ranked SNPs of genomewide association analysis in females

SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; CHR, chromosome; BP, base pair; OR, odds ratio.

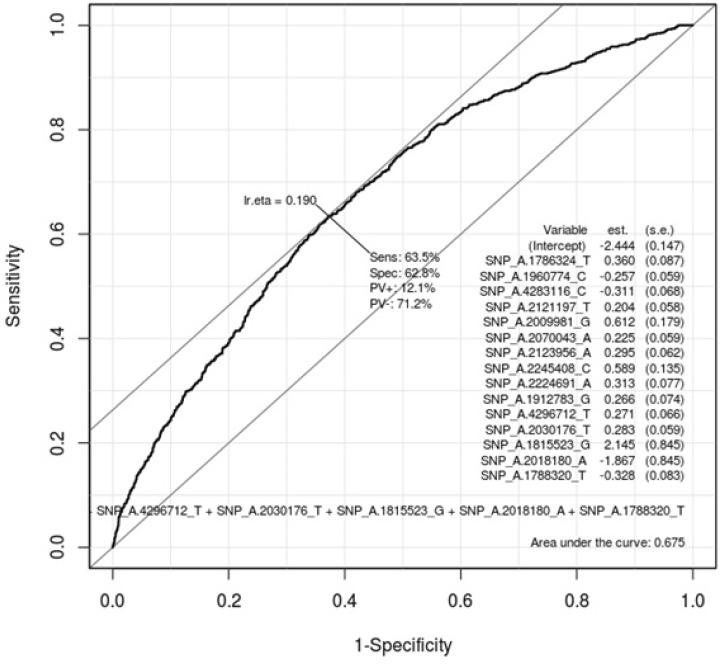

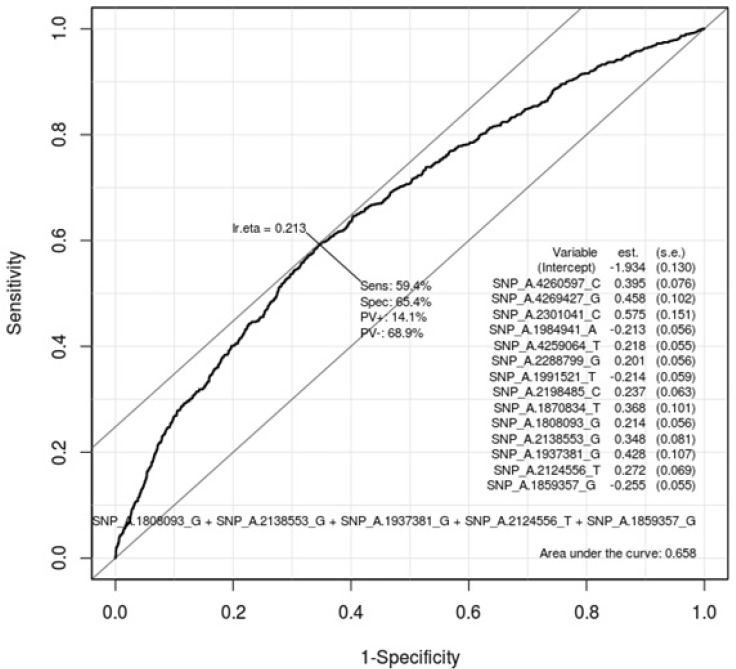

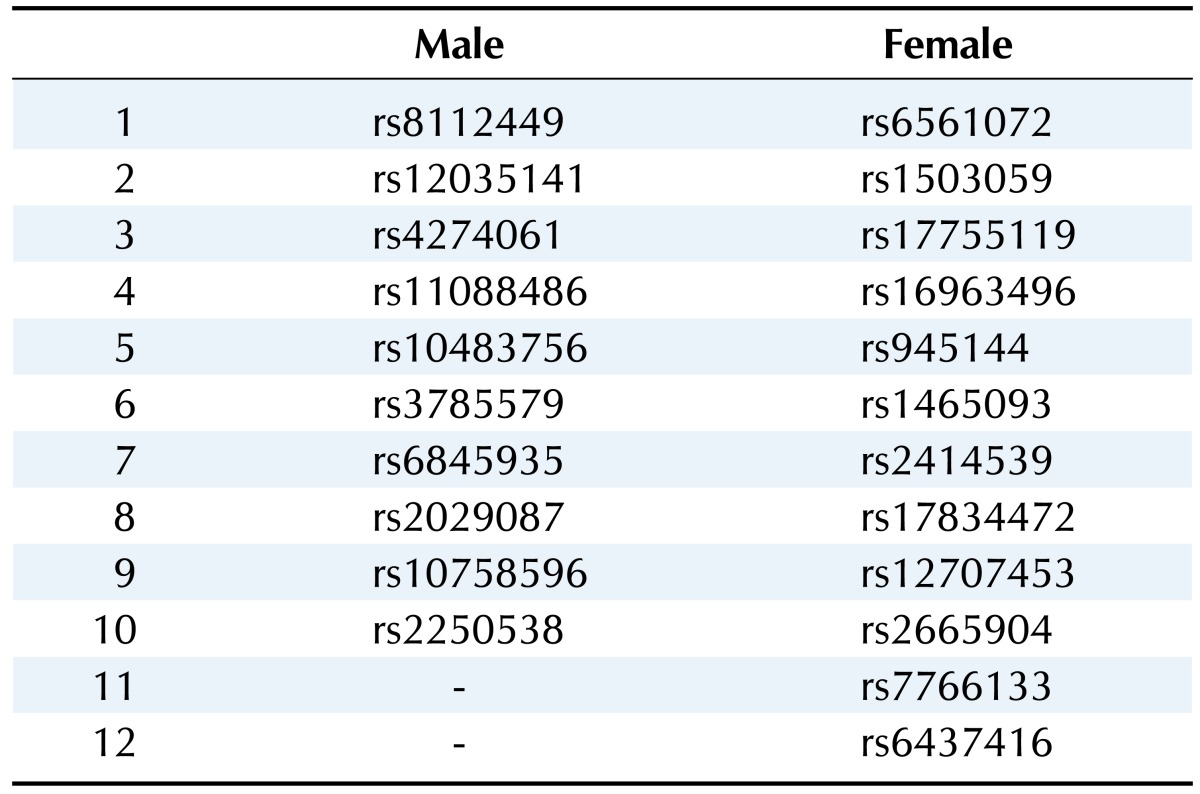

Table 5 describes the important SNPs associated with gastritis by logistic regression analysis among the top 20 ranked SNPs. The p-values of these SNPs were all <0.001. Figs. 3 and 4 show the ROC curve by using these SNPs in males and in females, respectively. The AUC scores are 0.675 and 0.658 in males and in females, respectively. The AUC score was too low to use as a specific factor for diagnosis.

Table 5.

Gastritis-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of gastritis-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in males. This shows how well 20 ranked gastritis-associated SNPs (Table 3) classify patients and normal subjects in males. As much as the ROC curve, these factors can classify gastritis patients and normal subjects in males.

Fig. 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of gastritis-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in females. This shows how well 20 ranked gastritis-associated SNPs (Table 4) classify patients and normal subjects in females. As much as the ROC curve, these factors can classify gastritis patients and normal subjects in females.

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed that vascular disease and gastritis have considerable association in Korean males. We also verified that gastritis is affected by other various drugs. However, we could not find gastritis-specific biomarkers for diagnosis.

Gastritis has numerous causes and is distributed as variable subtypes by phenotype. So, correctly diagnosing it is very important for therapy. Gastritis has non-specific phenotypes that can obscure finding the disease causes. So, more information is also needed to analyze the complex factors associated with disease rather than each factor associated with the disease. For example, confirmation of H. pylori infection, tobacco, smoking period, and alcohol intake are considered. This needs further study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Republic of Korea (4845-301, 4851-302, 4851-307).

References

- 1.Dikshit RP, Mathur G, Mhatre S, Yeole BB. Epidemiological review of gastric cancer in India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2011;32:3–11. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.81883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat. 2013;45:1–14. doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.45.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SJ, Baik GH, Youn KH, Song SW, Kim DJ, Kim JB, et al. The crude incidence rate of stomach cancer in Chuncheon-si during 2000-2002. Korean J Med. 2007;73:368–374. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strickland RG. Gastritis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1990;12:203–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00197506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:354–362. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baik SJ, Yi SY, Park HS, Park BH. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in female Vietnamese immigrants to Korea. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:517–521. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i6.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edgren G, Hjalgrim H, Rostgaard K, Norda R, Wikman A, Melbye M, et al. Risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcers in relation to ABO blood type: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1280–1285. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song HR, Shin MH, Kim HN, Piao JM, Choi JS, Hwang JE, et al. Sex-specific differences in the association between ABO genotype and gastric cancer risk in a Korean population. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:254–260. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0176-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YJ, Chung JW, Lee SJ, Choi KS, Kim JH, Hahm KB. Progression from chronic atrophic gastritis to gastric cancer; tangle, toggle, tackle with Korea red ginseng. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2010;46:195–204. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.10-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho YS, Go MJ, Kim YJ, Heo JY, Oh JH, Ban HJ, et al. A large-scale genome-wide association study of Asian populations uncovers genetic factors influencing eight quantitative traits. Nat Genet. 2009;41:527–534. doi: 10.1038/ng.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verhaak PF. Somatic disease and psychological disorder. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:261–273. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allison MC, Howatson AG, Torrance CJ, Lee FD, Russell RI. Gastrointestinal damage associated with the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:749–754. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209103271101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forman D, Burley VJ. Gastric cancer: global pattern of the disease and an overview of environmental risk factors. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:633–649. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Adult height and the risk of cause-specific death and vascular morbidity in 1 million people: individual participant meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1419–1433. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambrose JA, Tannenbaum MA, Alexopoulos D, Hjemdahl-Monsen CE, Leavy J, Weiss M, et al. Angiographic progression of coronary artery disease and the development of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12:56–62. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madhavan S, Ooi WL, Cohen H, Alderman MH. Relation of pulse pressure and blood pressure reduction to the incidence of myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 1994;23:395–401. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldstein JL, Hazzard WR, Schrott HG, Bierman EL, Motulsky AG. Hyperlipidemia in coronary heart disease. I. Lipid levels in 500 survivors of myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:1533–1543. doi: 10.1172/JCI107331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]