Abstract

Background

Few studies in Africa provide detailed descriptions of the vulnerabilities of female sex workers (FSWs) to violence.

Objective

To document the prevalence and types of violence experienced by FSWs, identify the risk factors of experiencing violence to women (VAW) and the perpetrators of these acts.

Methods

An analytical cross sectional survey of 305 brothel-based FSWs and in-depth interview of 20 chairpersons residing in brothels in Abuja, Nigeria was done.

Results

The prevalence of VAW six months preceding the survey was 52.5%. Sexual violence was the commonest type (41.9%) of violence experienced, followed by economic (37.7%), physical violence (35.7%) and psychological (31.9%). The main perpetrators of sexual violence were clients (63.8%) and brothel management (18.7%). Sexual violence was significantly more experienced (aOR 2.23; 95%CI 1.15–4.36) by older FSWs than their younger counterparts, by permanent brothel residents (aOR 2.08; 95%CI 1.22–3.55) and among those who had been in the sex industry for more than five years (aOR 2.01; 95%CI 0.98–4.10). Respondents with good knowledge levels of types of violence were less vulnerable to physical violence (aOR 0.45; 95%CI 0.26–0.77). Psychological violence was more likely among FSWs who smoked (aOR 2.16; 95%CI 1.26–3.81). Risk of economic violence decreased with educational levels (aOR 0.54; 95%CI 0.30–0.99 and aOR 0.42; 95%CI 0.22–0.83 for secondary and post secondary respectively). Consequences of the violence included sexually transmitted infections (20%) and HIV (8.0%).

Conclusion

Interventions that educate FSWs on their rights and enable them avoid violence are urgently required. Young women need economic and educational empowerments to enable them avoid sex work.

Keywords: female sex workers, violence against women, brothel based sex workers, prostitution in Africa

Introduction

Worldwide it is increasingly recognized that violence to women is a pervasive violation of fundamental human rights of women. The Millennium Development Goal three calls for the promotion of gender equality and empowerment of women 1. The African Plan of Action to Accelerate the Implementation of the Dakar and the Beijing Platforms for Action for the Advancement of Women (1999), and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights and the Rights of Women in Africa (2003) served to increase national governments commitment to women's rights. Hence most African governments are signatories to a number of international treaties and agreements on the rights of women 1,2. In addition, the Nigerian constitution prohibits discrimination and exploitation on the basis of gender 3 and the National Gender Policy promotes empowerment of women 4. Although these measures are in place, there is the need to monitor if they satisfactorily protect the human rights of women, particularly those of vulnerable groups. However, the entrenched patriarchal value system, the perpetration of traditions that identify women as inferior to men, high illiteracy rates, feminization of poverty and the low status of women in the society continues to make most African women vulnerable to violence 2, 5–7.

Female sex work (FSW) is an ancient and widespread profession. Worldwide it is estimated that more than 40 million people work as sex workers 8. In sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of FSWs in the capital cities ranged between 0.7% and 4.3% and in other urban areas between 0.4% and 3.9% in 2010 9. Despite their large number, sex workers are not accepted in most communities where they work 10–12. They are ostracized, marginalized and they experience discrimination from the society. In Pakistan, sex workers experienced verbal abuse from religious groups, human rights abuses from their relations and stoning by community members 13. Within the sex industry they do not fare any better, as FSWs in India experienced high levels of physical and sexual violence from clients, ‘madams' and the police 10. In relationships, sex workers were more vulnerable to violence from their main intimate partner or other nonpaying partners in India 14.

Violence is a common experience in the lives of many FSWs. In India, 70% of sex workers reported being beaten by the police and more than 80% had been arrested without evidence 15. In Bangladesh, between 52% and 60% of street-based sex workers reported being raped by men in uniform in a 12 month period, and between 41% and 51% reported being raped by local criminals 16. Similarly high rates were found among FSWs in Vancouver, Canada where 57% of FSWs experienced gender based violence over an 18 month follow-up period and in southern India 50% and 77% of FSWs reported work-related physical and sexual violence 10.

Few studies in Africa provide detailed descriptions of the vulnerabilities of FSWs to violence 17. In Namibia, 72% of 148 sex workers reported being verbally abused by clients and neighbors; approximately 16% reported abuse by intimate partners, 18% by clients, and 9% by policemen 18. In Kenya, sexual and physical violence was pervasive among FSWs. Violence was commonly triggered by negotiations around condom use and payments. Pressing financial needs, gender-power differentials, illegality of trading in sex and cultural subscriptions to men's entitlement for sex and money underscored much of the violence FSWs experienced in Kenya 17. Unfortunately, violence to sex workers often goes unreported and under-researched 19. There is paucity of data on the prevalence and experience of violence to FSWs in West Africa. This study is unique in that it identifies the factors that increase likelihood of experiencing physical, sexual, psychological and economic violence by FSWs.

The effects of commercial sex work are multifaceted 17,19. Sex work affects individuals in the profession as well as the society. FSWs are at risk of contracting HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections. For example, over one-third of sex workers in Nigeria are infected with HIV and in some cities, 50% of all brothel-based sex workers are HIV-infected 20. FSWs also experience reproductive health problems such as unintended pregnancy, septic abortion and maternal deaths. Babies born to sex workers are more likely to be low birth weight, premature and have higher risk of infant morbidity and mortality 21–23. Many young sex workers suffer from psychological reactions including depression, anxiety, irritability, distrust, shame, rejection, low self-esteem and post-traumatic stress disorder 22. Experience of violence may result in cuts, injuries and fractures 6. Socially, prostitutes are often stigmatized, shunned and discriminated against. Politically, sex work damages the image of a country by encouraging international trafficking in women 24.

Unfortunately, sex workers are often unable to access help from regular sources as other women, despite the fact that they are more vulnerable and experience many more health risks/ problems 5,18. Health care providers often fail to provide information or adequate services for this vulnerable group because of discriminatory attitudes 13. Even when care was available, sex workers perceived the stigma attached to sex work as a barrier to receiving health care, and often preferred care from peers who unfortunately may not be knowledgeable 25. This makes them more uninformed and therefore more vulnerable to violence.

FSWs like other professions have rights which should be protected and enforced. However, only very little is known about their experience and the perpetrators of violence to FSWs in Nigeria 12. Thus there is the need for studies which documents the violence experienced by this underserved group. Such data would guide the development of appropriate interventions and policies to protect this population's health. Hence this study documents the prevalence and types of violence experienced by FSWs in Abuja, Nigeria. It also identifies the risk factors of the different types of VAW and the perpetrators of these acts.

Methodology

Study area

The study was conducted in Abuja. Abuja is the capital city of Nigeria. It is located in the centre of Nigeria, within the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). Abuja is a planned city, built mainly in the 1980s. It officially became Nigeria's capital in 1991, replacing Lagos. At the 2006 census, the city had a population of 776,298 26. Recently, Abuja and the FCT have experienced huge population growth; it has been reported that some areas around Abuja have been growing at rates of 20% to 30% per year. Squatter settlements and towns have spread rapidly in and outside the city limits. Politicians, civil servants, entrepreneurs and expatriates have also relocated their residence to the city thereby making it a thriving city for commercial sex work. Furthermore, the proliferation of hotels, brothels, club houses and eateries has also made Abuja attractive to sex workers 27.

Study Design

The study was an analytical cross-sectional survey of FSWs residing in brothels in Abuja. The study employed both qualitative and quantitative methods. The qualitative method used was the in depth interview, while the quantitative method was the questionnaire survey. The qualitative method obtained in-depth information on theperceptions of the FSWs on the concepts of gender based violence. It also helped to formulate appropriate questions for the quantitative survey. The quantitative component focused on documenting the prevalence of the different types of violence. It allowed for statistical analysis and identification of predictors of violence experience.

Study Population

The study population was brothel-based FSWs from the different classes of brothels in Abuja. A brothel was defined as residential ‘quarters’ for sex workers or a place where people come to pay to have sexual intercourse with a sex worker. Most brothels in Nigeria are located in ‘hotels’ and have bars where alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks are sold 28. FSWs were women who live, work and offer sexual services for money in such houses. FSWs that pay for accommodation in these houses were referred to as resident or brothel based sex workers. The non-resident or street- based FSWs are often found on the streets around big hotels in the evenings or at night, soliciting for clients. The men who pick them up take them away to their home or hotel for the night or weekend.

Brothel-based prostitution has a hierarchical structure within which the sex workers operate. The brothel proprietor or manager is at the apex of the structure. Followed by the bar manager and then the chairlady who is the leader of the sex workers. The chairlady serves as an intermediary between the hotel management and the sex workers. She ensures the residents co-operate with the management. Her approval was required before the FSWs could be approached 28. Excluded from the study were street based FSWs and those who resided outside Abuja.

Sample size calculation

Sample size was calculated using the Stat Calc Module of EPI INFO version 6 statistical software package 29. This was based on the assumption that the proportion of women who had experienced violence against women in the north central zone of Nigeria was 31% 30. The significance level was set at 95%. The minimum sample size obtained was 257, a 10% adjustment for non response was done to obtain a sample size of 283.

Sampling technique

Prior to the selection of the brothels, a list of brothels in Abuja was developed using snow-balling technique. The brothels were stratified into three groups (high, middle and low class) based on their geographical location and the status of their clients. The simple random sampling technique was used to select the brothels for the study. Brothels were proportionally allocated between the three classes of brothels. In the selected brothels, all FSWs were approached to participate in the study. Twenty brothels comprising of seven high, five middle and eight low class brothels were involved in the study. A total of 305 brothel-based FSWs comprising of 110 FSWs from the high, 63 from the middle and 132 from the low income areas were interviewed. In addition, 20 in-depth interviews (seven in the high class, five from the middle class and eight from the low class brothel) were conducted with the chairlady or her representative.

Study Instruments

Data collection instruments were a semi-structured interviewer administered questionnaire and in-depth interview guide. The instruments were developed after reviewing relevant literature on violence against women and commercial sex work 10, 14, 31, 32. The questionnaire also built on the tool used in the World Health Organization multi-country survey on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women 33.

The questionnaire had five sections. Section one documented respondents' socio-demographic characteristics, parental background and reason for being in sex work. Section two assessed the respondents' knowledge on the different types of violence against women. Section three focused on perceptions on gender norms and violence to women. Section four reported on experience of physical, sexual, psychological and economic violence and the perpetrators of these acts, while section five sought suggestions on how to prevent violence to FSWs. The in-depth interview guide comprised of eight questions. It obtained information on how FSWs commenced sex work, history of inter-parental violence, types of VAW experienced and suggestions to end violence.

Both instruments were pretested in March 2009 on 18 FSWs and two chairpersons at two brothels in a neighboring state. Following this pre-test both instruments were modified to improve understanding and ease of administration.

Data Collection

Two female research assistants, aged between 22 and 30 years helped with the data collection. The research assistants had secondary school education and could speak Pidgin English (the type of English spoken by the FSWs) fluently. The research assistant's were trained over a three-day period by the investigators. Training was on how to administer the questionnaire to ensure responses were valid and on the basics of VAW. In addition, the interviewers were trained on maintaining responses confidential and ensuring safety for themselves and the interviewees. The research assistants' data collection skills and abilities were reassessed at the pretest. Only when they had satisfactorily performed were they allowed to proceed with data collection.

The interviews were held in Pidgin English. Interviews took place in a private place within the brothel or in the respondents' room. Care was taken to avoid presence of other sex workers or hotel staff during the interviews. Interviewers stressed the fact that honest responses were needed to gain clear insight into violence to FSWs. Each interview took about 20 minutes. Data collection was done between April and July 2009. A total of 305 FSWs were interviewed.

Ethical Considerations

The World Health Organization Recommendations on Ethics and Safety for research on domestic Violence against Women was used as a guide 34. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Joint University of Ibadan / University College Hospital Institutional Review Committee. Permission was obtained from the brothel management and chairperson after explaining the purpose of the study. Because sex work is illegal and respondents did not feel at ease to sign the consent form for fear of the law, therefore verbal consent was obtained from each sex worker. Respondents were free to decline to participate in the study or not to answer questions they were not comfortable with. Confidentiality and anonymity was maintained. As an incentive, male and female condoms were distributed to the FSWs after the interviews. The FSWs were also trained on how to use the female condom and were encouraged to use it with clients who refuse to use the male condom. FSWs in need of care were referred to a secondary health facility for treatment.

Data Analysis

Data entry, cleaning and analysis were done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 35. Univariate, bivariate and multivariate analysis was done. P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. In the univariate analysis, frequencies, means and standard deviations were calculated as appropriate. Knowledge scores were computed by awarding one mark to every correct response given on 22 statements that assessed respondents' level of knowledge on VAW. Thus the maximum obtainable knowledge score was 22 and minimum 0. Perception score was computed by awarding two marks for positive attitude, one for not sure and 0 for negative attitudes on 10 statements which assessed FSWs perceptions on violence and women's rights. The maximum obtainable perception score was 20. The bivariate analysis tested for association using the Student t test for continuous variable and the Pearsons Chi-square test for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression model was used to describe the relationship between factors significant at bivariate analysis and to adjust for the effect of confounders. Stepwise regression (forward selection method) was used to choose explanatory variables for the multivariate analysis and was also verified using the backward selection method. The model with the maximum likelihood ratio was adopted as the best fit for the data.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

As shown in Table 1, most (48.5%) of the respondents were in the 25 to 29 years age bracket. The mean age of the FSWs was 27.4 ±5.7±5.7±5.7 years. Many had secondary school education (42.3%), while (32.4%) had tertiary education. Many (69.5%) has never been married, 49.0% had a child or children. Most (72.5%) were Christians. Eighty nine percent of FSWs took alcohol before engaging in sexual intercourse, while 56.4% smoked the cigarette or Indian hemp.

Table 1.

Respondents Socio-demographic Characteristics

| Variables | Frequency (n=305) |

Percent |

| Age (yrs) | ||

| <25 | 78 | 25.6 |

| 25–29 | 148 | 48.5 |

| ≥ 30 | 79 | 25.9 |

| Educational status | ||

| None | 56 | 18.4 |

| Primary | 21 | 6.9 |

| Secondary | 129 | 42.3 |

| >Secondary | 99 | 32.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 212 | 69.5 |

| Ever married | 93 | 30.5 |

| Religion | ||

| Other religion | 84 | 27.5 |

| Christians | 221 | 72. 5 |

| Alcohol intake | ||

| No | 33 | 10.8 |

| Yes | 272 | 89.2 |

| Smoking | ||

| No | 133 | 43.6 |

| Yes | 172 | 56.4 |

| Activity status | ||

| Part-time | 153 | 50.2 |

| Full-time | 152 | 49.8 |

| Class of brothel | ||

| Middle/low | 195 | 36.1 |

| High | 110 | 63.9 |

| Type brothel stay | ||

| Temporary/few hours | 99 | 32.4 |

| Permanent | 206 | 67.6 |

| Duration of sex work | ||

| <1year | 90 | 29.5 |

| 1–5years | 157 | 51.5 |

| >5years | 58 | 19.0 |

| Inter parental violence experience | ||

| No/don't know | 157 | 51.5 |

| Yes | 148 | 48.5 |

Mean age was 27.44±5.68

As regards FSWs family background, 35.6% of fathers and 40.5% of mothers had no education. Most of the fathers were farmers (43.7%), while most mothers were traders (46.2%). Only 42.5% had both parents alive and living together.

Occupation of sex work

Twenty-nine percent began sex work a year preceding the survey. Forty nine percent (151) were full time sex workers, while the others worked part time. The jobs done by part time workers included hairdressing, catering, tailoring and some were students. Most 67.8% (207) were permanent brothel residents. Introduction to sex work was mainly by friends (69.0%). Fifteen percent stated that they were forced by their parents and sisters into the profession. Mean age at entry into sex work was 23.5 years. About a third (34.0%) earned less than 60 dollars in a week, while, 22.0% earned between 60 and 120 dollars in a week. From the interviews, the charge “per round of sex” varied, and depended on age of the FSW, social class of the brothel and general appearance of the client. A chairlady said, ‘sex workers who are young, well educated, and can speak good English are the luckiest. They are able to charge customers more’. Another said, ‘new arrivals to our brothel charge the highest because they are in high demand and the men pay’. Another said, ‘when a customer comes we size him up very well to know what to tell him to pay’.

Clients were often men who visited the brothels (56.5%), however some clients were obtained on the phone (15.4%). Most (39.2%) did not know the occupation of their clients, however clients included policemen and soldiers (12.1%), commercial motor cycle riders and bus drivers (8.8%), students (6.2%), politicians (9.5%) and expatriates (10.1%).

Reasons for engaging in sex work

From the survey, reasons given for engaging in sex work were “lack of money” (53.6%), “lack of financial support from parents, relatives or partner” (16.5%), for sexual satisfaction (9.4%) and death of spouse (5.4%).The in-depth interview highlighted the role of economic factors in FSWs decision to work as prostitutes. Responses were:-

“I am a waitress in this hotel and anytime I am broke, I change my uniform to casual wear and call my ‘'sugar daddy'’ because I have many mouths to feed. At the end of the day, I must definitely go home with something”

Another said: “I am a graduate and I searched for a job for more than two years but when the suffering was too much a friend of mine introduced this “never short” business to me since then I have no course to regret because I was able to meet my needs.”

A part time sex worker said “I am a receptionist in this hotel and I often stay late to meet some big men after work for more money because my pay is small.”

Another stated “My parents are in the village, they are very old and do not have any means to sponsor any of their children to school, they still expect me to sponsor my younger ones and also bring money home.”

A very different reason was given by a chairperson who stated the following, ‘Abuja was a “happening town” and I want to live in a place where I can enjoy my life.’

Another chairlady admitted, ‘some FSWs have a craving for sex and have to fulfilling their sexual desires by offering their services almost free of charge or at ridiculously low prices. Sometimes they settle for just anybody or go to the streets out of desperation for a man’.

Knowledge on violence against women

All the respondents stated that they were aware of what VAW was. The main source of information was from posters or billboards (15.0%). Other sources were television (14.1%), newspapers or magazines (14.1%), fellow sex workers (11.4%), radio (11.1%) and friends (10.5%). Beating was the commonest act of physical violence mentioned (78.4%), unwanted touch of breast or buttocks was the most common (49.5%) form of sexual violence stated, while verbal abuse (71.5%) was stated as a type of psychological violence by 71.5% of respondents. Economic violence was mainly stated to be financial exploitation (42.8%). About a third (61.8%) knew VAW could occur on the streets, while 20.7% knew it could occur in the home. Mean knowledge score out of 22 was 16.06±5.21. Using the mean score of greater than 16, 57.6% of the respondents had adequate knowledge, while 42.4% had inadequate knowledge levels.

Factors associated with being knowledgeable on violence

As shown in Table 2, FSWs with post secondary education (attended college of education, polythenic or university) were more knowledgeable (OR 5.67; 95% CI 2.94–10.93) than those with secondary education (OR 2.16; 95% CI 1.19–3.91), who in turn were more knowledgeable than FSWs e who did not attend school or attended up to primary school level . FSWs that lived in high class brothels were three times more likely (aOR3.37; 1.77–6.42) to have good knowledge levels compared with those staying in low or middle class brothels. FSWs with family history of inter-parental violence were more likely to be knowledgeable about violence (OR 2.98; 1.87–4.77). Full time sex workers (OR 0.45; 0.29–0.72) and permanent brothel dwellers were less likely (OR 0.42; 0.26–0.70) to be knowledgeable.

Table 2.

Regression Analysis of Factors Influencing FSWs Knowledge

| Variables | Unadjusted Odds Ratios (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratios (95% CI) Knowledge |

| Age group (yrs) | ||

| <25 | 1 | |

| 25–29 | 1.58 (0.91–2.74) | |

| >30 | 1.40 (0.74–2.63) | |

| Education | ||

| ≤primary | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary | 2.16 (1.19–3.91) | 1.20 (0.59–2.41) |

| >Secondary | 5.67 (2.94–10.93) | 1.66 (0.73–3.78) |

| Brothel class | ||

| Middle/low | 1 | 1 |

| High class | 5.21 (3.07–8.86) | 3.37 (1.77–6.42) |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 1 | 1 |

| Ever married | 0.35 (0.21–0.59) | 0.32 (0.17–0.59) |

| Religion | ||

| Other religion | 1 | 1 |

| Christians | 0.44 (0.26–0.75) | 0.50 (0.27–0.92) |

| Alcohol intake | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.62 (0.29–1.30) | |

| Smoking | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2.09 (1.32–3.31) | 1.76 (1.02–3.04) |

| Activity status | ||

| Part-time | 1 | 1 |

| Full-time | 0.45 (0.29–0.72) | 0.70 (0.39–1.24) |

| Brothel stay | ||

| Temp/few hrs | 1 | 1 |

| Permanent | 0.42 (0.26–0.70) | 0.62 (0.33–1.18) |

| Duration of sex work | ||

| <1yr | 1 | |

| 1–5yrs | 1.60 (0.94–2.75) | |

| >5yrs | ||

|

Parental violence experience |

||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2.98 (1.87–4.77) | 1.57 (0.86–2.83) |

Perceptions on VAW

Respondents' perceptions on acts of violence to women are shown in Table 3. Many (73.1%) agreed that women in all professions experience violence from men. Many (69.5%) also felt that violence from clients was part of the job and there was nothing to be done about it. Coercing a woman into sex work was perceived to be a form of VAW by 67.2% of the FSWs. The mean perception score out of 20 was 11.49±1.11.

Table 3.

Respondents Perception on Violence against Women

| Perception Questions | Agree | Not sure | Disagree |

| Violence to females occurs to women in all profession | 223(73.1) | 78(25.6) | 4(1.3) |

| Violence from client is part of business, there is nothing to be done about it |

212(69.5) | 81(26.6) | 12(3.9) |

| Abuse occurs even to wealthy women | 217(71.1) | 79(25.9) | 9(3.0) |

| Women should only play a background role in the society | 207(67.9) | 88(28.9) | 10(3.3) |

| Women shouldn't be involved in politics and governance | 202(66.2) | 90(29.5) | 13(4.3) |

| Violence to women occurs in all countries of the world | 225(73.8) | 78(25.6) | 2(0.6) |

| Women and men should have equal opportunities | 213(69.8) | 79(25.9) | 13(4.3) |

| Coercion of women into sex work is a type of violence | 205(67.2) | 86(28.2) | 14(4.6) |

| Rape is a very serious form of violence | 227(74.4) | 69(22.6) | 9(3.0) |

| Clients having sex and refusing condom use is violence to you | 225(73.7) | 74(24.3) | 6(2.0) |

Mean perception score was 11.49±1.11.

Experience of VAW

Prevalence of VAW- The prevalence of experiencing any act of violence six months preceding the survey was 52.5% (160). Of those who had been victims, 59.5% had experienced three or more episodes of abuse in that period. Sexual violence was the commonest type (42.5%) of VAW experienced, followed by economic violence (38.7%), physical violence (35.7%) and psychological violence (31.9%) (Table4). Twenty two percent (68) of the FSWs had been sexually abused in childhood (< 18 years). The mean age at first sexual assault was 14±2.2 years.

Table 4.

Regression Analysis of Factors Influencing Experience of Physical, Sexual, Psychological and Economic Violence

| Variable | Physical violence | Sexual violence | Psychological violence | Economic violence | ||||

| Age grp (yrs) | ||||||||

| ≤25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 25–29 | 0.89(0.49–1.61) | 0.70(0.35–1.38) | 0.79(0.45–1.39) | 0.80(0.45–1.43) | 0.86(0.46–1.59) | 0.79(0.38–1.62) | 0.78(0.44–1.39) | |

| ≥30s2 | 2.14(1.11–4.10) | 1.35(0.62–2.96) | 1.88(0.99–3.56) | 2.23(1.15–4.36) | 2.20(1.13–4.28) | 1.69(0.72–3.99) | 1.27(0.67–2.41) | |

| Education | ||||||||

| ≤ Primary | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Secondary | 0.55(0.30–0.99) | 0.63(0.35–1.12) | 0.51(0.28–0.92) | 0.57(0.29–1.15) | 0.59(0.33–1.06) | 0.54(0.30–0.99) | ||

| <Secondary | 0.64(0.35–1.19) | 0.69(0.38–1.26) | 0.41(0.21–0.77) | 0.29(0.14–0.62) | 0.38(0.20–0.70) | 0.42(0.22–0.83) | ||

| Brothel class | ||||||||

| Middle/low | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| High class | 1.12(0.69–1.82) | 1.07(0.67–1.73) | 1.06(0.64–1.76) | 0.71(0.43–1.16) | ||||

|

Marital status |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Never married | 1.46(0.88–2.41) | 1.60(0.97–2.62) | 1.64(0.98–2.74) | 1.08(0.65–1.79) | ||||

| Ever married | ||||||||

|

Alcohol intake |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| No | 1.55(0.69–3.46) | 1.34(0.63–2.83) | 1.09(0.50–2.38) | 1.12(0.53–2.37) | ||||

| Yes | ||||||||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.91(1.17–3.12) | 1.81(1.06–3.12) | 1.98(1.23–3.17) | 1.90(1.17–3.10) | 2.18(1.31–3.63) | 2.16(1.26–3.81) | 1.77(1.09–2.85) | 1.90(1.15–3.14) |

| Brothel stay | ||||||||

| Temp/few | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| hrs | 1.17(0.70–1.95) | 1.78(1.07–2.95) | 2.08(1.22–3.55) | 1.52(0.88–2.60) | 2.58(1.26–3.81) | 2.34(1.36–4.01) | 1.92(1.08–3.41) | |

| Permanent | ||||||||

|

Duration of SW <1yr |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1–5yrs | 1.60(0.88–2.92) | 1.89(0.96–3.69) | 1.73(0.99–3.03) | 2.06(1.08–3.92) | 2.58(1.26–5.29) | 1.59(0.90–2.81) | ||

| <5yrs | 4.15(1.97–8.75) | 4.40(1.84–10.51) | 2.01(0.98–4.10) | 3.97(1.83–8.60) | 3.77(1.53–9.32) | 1.72(0.83–3.58) | ||

|

Parental violence |

0 | |||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.20(0.75–1.92) | 1.37(0.86–2.16) | 1.02(0.63–1.65) | 1.31(0.82–2.09) | ||||

| Knowledge | ||||||||

| Poor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Good | 0.60(0.37–0.97) | 0.45(0.26–0.77) | 0.82(0.52–1.30) | 0.90(0.55–1.46) | 0.70(0.44–1.12) | |||

Factors associated with experience of violence

Any form of violence: The experience of violence was significantly more among respondents who were above 29 years of age (65.4%) compared with those who were less than 25 years (53.2%) or between 25 and 29 years (45.9%)(p=0.02). FSWs with no or primary education (66.7%) experienced more violence that those with secondary (46.7%) secondary and post secondary education (51.5%) (p=0.02). Although not statistically significant, FSWs from low and middle class brothels, who had ever been married, who smoked, were full time FSWs, and were permanent brothel residents were more vulnerable to violence. Also, FSWs who had been in the brothel for more than five years, with history of inter parental violence and poor knowledge levels were more vulnerable to violence. The effect of these factors on the different types of violence was explored using regression analysis below.

Physical: Respondents older FSWs (who were above 30 years of age) were one and half times more likely (aOR 1.35; 0.62–2.96) to experience VAW than those who were young (less than 25 years of age, while those who were between 25 and 29 years were less likely (aOR 0.70; 0.35–1.38) to experience violence than those who were below 25 years of age. Also respondents who had been in the profession for more than five years were five times more likely to experience violence (aOR 4.40; 1.84–10.51) than respondents who were with less than a year in the profession. (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.01–3.52). As shown in Table 4, respondents with good knowledge levels were less vulnerable to physical violence (aOR 0.45; 0.26–0.77). Although not statistically significant, FSWs who consumed alcohol, had ever been married, were permanent brothel residents and with history of inter parental violence were more likely to physical experience violence (Table 4).

Sexual: Sexual violence was significantly more experienced (aOR 2.23; 1.15–4.36) by older FSWs than their younger counterparts, by permanent brothel residents (aOR 2.08; 1.22–3.55) and among those who had been in the sex industry for more than 5 years (aOR 2.01; 0.98–4.10) (Table 4). FSWs who consumed alcohol, smoked, had ever been married, and with history of inter parental violence were more likely to experience violence although these did not reach significant levels.

Psychological: Being educated was protective against psychological violence. FSWs with secondary education were 81% less likely (aOR 0.29; 0.14–0.62) to experience violence, while those with primary education were 49% less likely (OR 0.51; 0.28–0.92). FSWs who had been in the sex industry for more than 5 years were four time more likely (aOR 3.77; 1.53–9.32), while those between one and five years were two and a half times more likely (2.58; 1.26–5.29).

Economic:_Similar to the predictors of psychological violence, less educated FSWs, those who smoked (aOR1.90; 1.15–3.14) and permanent brothel dwellers (aOR1.92; 1.08–3.41) were more vulnerable to economic violence (Table 4).

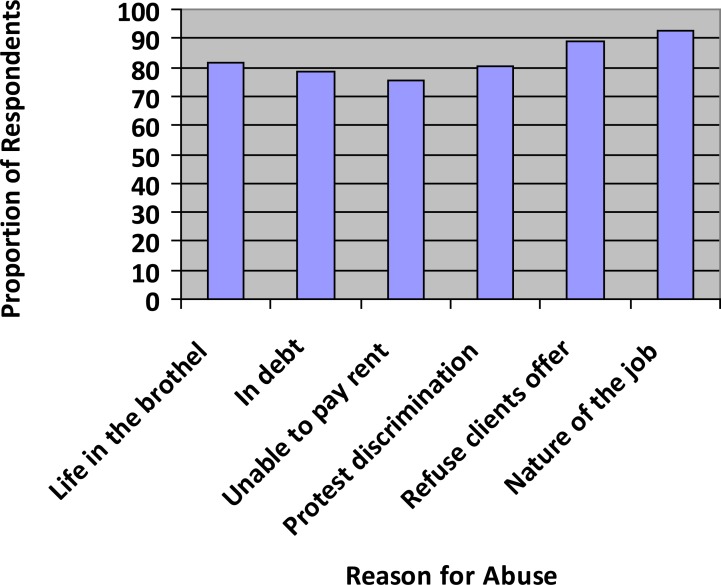

Triggers of violence - Respondents stated nature of the job (92.4%), declining clients' offers (89.2%), living in the brothel environment (81.3%) as reasons for occurrence of violence within the last six month (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Triggers for Experiencing Violence Against FSWs

Perpetrators of Violence - The one main perpetrator of violent acts in last six months were stated to be clients (63.8%), brothel staff (16.3%), policemen (6.3%), thugs (4.5%) and strangers (8.1%). In that time interval, 18.8 % of the victims had experienced three episodes of violence, while 38.1% has experienced for than three episodes. The perpetrators of the last episode of violence were mostly clients (Table 5).

Table 5.

Perpetrators of Physical, Sexual, Psychological and Economic violence

| Perpetrators | Physical | Sexual | Psychological | Economic |

| n=107 | n=128 | n=96 | n=115 | |

| Clients | 55 (56.4) | 84 (65.6) | 61 (63.5) | 74 (64.3) |

| Brothel staff / | 20 (18.7) | 17 (13.3) | 15 (15.6) | 19 (16.5) |

| owners | ||||

| Police | 10 (9.3) | 8 (6.3) | 5 (5.2) | 5 (4.4) |

| Strangers | 12 (11.27) | 7 (5.4) | 6 (6.3) | 8 (7.0) |

| Local thugs | 6 (5.6) | 6 (4.7) | 5 (3.2) | 5 (4.4) |

| No response | 4 (3.6) | 6 (4.7) | 4 (4.2) | 4 (3.4) |

Clients were the perpetrator of physical (56.4%), sexual (65.6%), psychological (63.5%) and economic violence (64.3%). Other perpetrators of sexual violence included brothel staff (13.3%) and police officers (6.3%). The perpetrators of the childhood sexual abuse were mainly family friends (66.8%) such as neighbors, father's friend, brother's friend and relatives (22.1%).

As regards the perpetrators of violence a FSW said ‘Many of the local thugs like to touch our backside or breast while we are walking on the streets, also some of our clients ask for more rounds of sex which was not in the initial agreement when they refuse to pay for these extras this results in fights, slaps or attempted rape. These are some of the common things we experience with this work’.

‘Policemen take advantage of us, they raid our brothels and then gang-rape us saying there is nothing we can do because our work is illegal’.

‘When we are unable to pay our rent quickly some brothel managers ask for free sex every time until we can pay’

Sources of help/succor following violence - Following experience of violence in the six months preceding the survey, victims reported to or sought for help from the chairlady (68.8%), fellow sex workers (46.3%), the police (42.5%), family and friends (18.2%), community or religious leaders (19.4%) and a health facility or nongovernmental organization (34.4%),

Health consequences of violence - Respondents reported loss of self esteem (29.0%), depression (21.0%), physical injury (21.0%); unwanted pregnancy (7.0%) and contracting a sexually transmitted infection (16.0%) as consequences of the violence experienced. However from the interviews, it appears that not all FSWs perceived the risk associated with the job and stated, “We are all meant to live and die”. Another FSW said “a person must die of something there is no problem with this work”.

Future plans - About half (148 or 48.4%) were willing to leave the job if they were given an alternative source of income. Of this group, 23.0% were willing to be traders, 23.0% wanted to go back to school, 11.5% will like to have a shop of their own were they could be hairdressers, tailors or caterers, 8.1% wanted to work in an office, while 20.9% would like to get married and be homemakers. Reasons for not wanting to quit sex work included: - There is no other job to do (8.3%), the sexual pleasure (15.9%), it's an easy way to make money (53.5%).

Suggestions to stop violence to FSWs - Suggestions to stop violence to sex workers included:-government or police intervention to stop violent acts (21.9%), public enlightenment programmes (5.2%), punish perpetrators (7.8%), involve non-governmental organizations (1.8%), involve faith based organizations (2.6%). Most (42.1%) had no suggestion.

Discussion

Most of the FSWs were young. About a quarter commenced the profession in the year preceding the survey. Discussions with the older FSWs revealed that many had started sex work in their youth. Studies have documented the use of minors for commercial sex work 9, 10, 13. Similar to findings of other researchers, most were unmarried 12, 24. This may be a consequence of the occupation, as sex workers are considered unmarriageable 24. It may also be deliberate to enable them engage freely in the profession. Most were from poor parental background. Despite having as high as tertiary education, some were in the commercial sex occupation. Researchers have reported that many young girls get lured into selling sex due to migration from rural to urban areas in search of work. In the urban cities, they are exposed to situations, which may leave them vulnerable to sexual exploitation and sex work 36. Thus it is crucial to inculcate values in young girls either through religion, culture or the family. It is also necessary to empower female adolescents and youth with information to enable them make healthy sexual and reproductive health choices from their early years.

Commercial sex work appears to be a thriving industry, despite the fact that it is illegal. Financial hardship was often the “push factor” for engaging in sex work and prostitution was considered as a lucrative profession. Many researchers have attributed engagement in sex work to the absence of a better job and the comfort of a relatively high income 10,15, 19, 28. Also the quest for material things, new consumer lifestyles, peer influence and changing social values make young girls ready prey for sex work 36. According to Akomah et al the economic motive for prostitution is so strong that it engenders a state of helplessness amongst prostitutes with respect to when, where, and whom to have sex with and whether or not to use condoms in the act 36. Thus, unless there is a change in the economic situation in Nigeria, prostitution will continue to thrive 36. Initiatives which creates economic opportunities for women to enable them avoid sex work are urgently required. Also the governments need to address the dire economic situation to ensure it promotes development and thereby create employment opportunities for young women.

Similar to findings in Uganda and Vietnam, some FSWs had been forced or had initiated sex following childhood sexual abuse by relatives and teachers 25, 32. Childhood sexual abuse increases later probability of engaging in sex work in adulthood through encouraging sexual risk taking and drug abuse 22. Initiatives which address parental care or supervision to avoid child sexual abuse are also crucial. Sex workers with sexual problems and addictions should be referred for mental health care.

Many sex workers were knowledgeable about the types of violence and on womens rights. However they accepted violence and considered it “normal” or “part of the job”. While knowledge does not necessarily translate to behavior change, ability to identify health risk and risky behaviors is a necessary precondition for behavior change. Low risk perceptions might have contributed to FSWs reluctance to report abuse or seek help following violence, despite the fact that they wanted violence to stop and perpetrators punished15. The low risk perception may also have contributed to the FSWs attitude that there was no reason to discontinue the occupation for more safe professions. The longer FSWs were in the occupation or brothel environment the less knowledgeable they were. Thus it is necessary for programs to help brothel based FSWs to undertake accurate self-appraisal of risk associated with their work. In addition, to the risk of contracting HIV/AIDS, there is the danger of being murdered 25.

There is need to address the modifiable risk factors of violence. These include inter-parental violence, low educational levels, smoking and alcohol use. Witnessing inter-parental violence in childhood could lead to a normative understanding of violence, as violence is regarded as a fitting means of conflict resolution 1,2. Previous studies have reported the harmful consumption of alcohol and the abuse of substances by FSWs in the belief that they enhance sexual performance, boost courage and provide warmth12,13,19,22,28,32. Unfortunately alcohol users are also at increased risk of sexually transmitted infections and HIV, because alcohol impairs judgment, thereby predisposing users to engage in risky sexual activities 13. FSWs had the highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS among other identifiable groups in the Nigerian national sero-prevalance survey. Also, while HIV prevalence among the general population has been declining, the prevalence among sex workers has shown no sign of declining 37. Unfortunately, the combination of violence and AIDS-related stigma undermines HIV prevention efforts by affecting the psychological well-being of FSWs. Thus interventions sensitizing FSWs on risk factors of violence and encouraging them to change violence-promoting behaviours are urgently required.

Our results show that the longer the FSWs stayed in the sex industry and brothel environment the more susceptible they were to violence. Older aged sex workers, permanent FSWs and those who had been in the occupation for a long time were more likely to be victims. It is also probable that the longer they remained in the brothels, the more likely they were to engage in harmful alcohol use, substance abuse or contracting HIV infection. Thus being a brothel based FSW increases chances of being uninformed about health matters, and FSWs vulnerability to other health problems and their consequences.

The sex industry is often based on exploitation, abuse and enslavement of young women 8. FSWs are surrounded by a complex web of “gatekeepers”, which includes owners of sex establishments, managers, clients, intimate partners, law enforcement authorities and local power brokers, all of whom often have control or power over sex workers daily lives 13,18,22. Gatekeepers may exert control by dictating the amount charged by FSWs, client sex workers can take on, and even whether sex worker can or cannot insist on condom use. Some gatekeepers may exert control through subtle means such as emotional manipulation. Control could also be through overt means such as threat of or actual sexual and physical violence, physical isolation and threat of handing sex worker over to legal authorities, and forced drug and alcohol use 13,18,22. Thus extent of FSWs autonomy in work arrangements is often varied and limited. Unfortunately, violence and lack of control over their lives means that FSWs may give lower priority to their own health, safe sex and behavior change, over more immediate concerns for safety and survival 31. In Mexico, deciding where to work, working with a third party, avoiding theft, and dealing with police were the “hierarchy of risk” or FSWs concerns 39.

However, gatekeepers activities may sometimes be protective. A qualitative study from two cities in the United Kingdom which compared the violence experienced between women who work on the street and those who work from indoor sex work venues, found that the indoor workers and their management were able to develop and maintain safety and order in the establishment through organization of protection measures 10,11.

The perpetrators of violence were mainly clients, however police officers were also included. In Kazakhstan, policemen routinely arrested, beat and forced sex workers to bribe arresting officers with money or sexual services 33. Police officers were also reported to have gang-raped FSWs during brothels raids, and refused to pay FSWs after patronage 11,13,14. In Pakistan, a study of male and female sex workers revealed that both groups experienced human rights abuses from relations, clients and the police who all perpetrated verbal, physical and sexual violence to FSWs 13. Thus there is need for enlightenment programmes directed specifically at clients of brothels. Men who perpetrate VAW should be punished to deter others. Also police officers need periodic training on women's rights and work ethics.

Multilevel interventions are required to promote the health and human rights of sex workers in Nigeria.

This could start with education of FSWs on how to avoid and protect themselves from violence, followed by public enlightenment to reduce the perpetration of violence to FSWs. Initiatives which address parental care or supervision to avoid child sexual abuse, law enforcement training on dealing with sex workers, and societal norms towards women in general will be crucial to stemming violence against female sex workers.

Developing policies that promote employment and health care for sex workers is crucial. Finally, studies on the occurrence of violence between FSWs, and on effective ways to eliminate young women's entry into sex work are recommended.

One of the strengths of our study was that both qualitative and quantitative methods were employed. Studying sex workers was complicated by the methodological problems encountered in interviewing a suspicious population. Initially, some FSWs wondered whether the interviewers were trying to expose their identity or take secret photographs. Yet, FSWs are vulnerable populations in many low income countries, with only limited access to health information 24. A limitation of our study was reporting bias. Some of the FSWs gave socially desirable responses, while some who declined to participate or respond to some of the questions might have had bad experiences they did not wish to recall or share. Although our study has provided data for understanding the extent and nature of violence to FSWs, our results cannot be generalized to non-brothel based sex workers.

Conclusion

Prevalence of violence to female sex workers was high. There is the need to protect FSWs from all forms of violence. Thus, it is necessary to address the social and economic challenges that encourage sex work. Young girls and women also require education on sexual and reproductive health. The education should aim at discouraging prostitution, encouraging values clarification and inculcating conflict resolution skills. In addition, interventions that target FSWs, brothel owners and their clients will be crucial to end violence to sex workers. Public enlightenment programs or interventions targeted at enlightening women on their rights and creating awareness on VAW should be vigorously pursued. Men who perpetrate violence should be punished to deter others.

Acknowledgement

We thank the National Agency for Control of AIDS (NACA) and the Institute of Human Virology Nigeria (IHVN) for donating male and female condoms which were distributed to the FSWs as incentives.

References

- 1.United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United Nations Development fund for Women (UNIFEM), Office of the Special Adviser on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women (OSAGI), author Combating gender based violence: a key to achieving the Millennium Development Goals. New York: UNFPA/UNIFEM/OSAGI; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Population Council, author. Sexual and gender based violence in Africa. Literature review. New York: Population Council; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN), author Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999. [19th of November, 2012]. http://www.nigeria-law.org/ConstitutionofTheFederalRepublicOfNigeria.htm.

- 4.Duke SB, Effiong D, Abuja, editors. Federal Ministry of Women Affairs of Nigeria/Gender and Development Actions, author. National Gender Policy: A simplified Version. Nigeria: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Bank, author. Addressing violence against women in middle and low-income countries: A multi sectoral approach. Sector operational guide for the World Bank Gender and Development Group. Washington DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation (WHO), author World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria, United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF), author Women and children rights in Nigeria: A wake up call - Situation assessment and analysis. Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health Abuja; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Audet E, Carried M. Decriminalize prostituted women, Not prostitution. [28th February, 2013]. Retrieved from: http://www.sisyphe.org.

- 9.Vandepitte J. Estimates of the number of female sex workers in different regions of the World. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(suppl)(3):18–25. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George A, Sabarwal S, Martin P. Violence in contract work among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:S1235–S1240. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramesh S, Ganju D, Mahapatra B, Mishra RM, Saggurti N. Relationship between mobility, violence and HIV/STI among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:764–768. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Popoola BI. Occupational hazards and coping strategies of sex workers in southwestern Nigeria. Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(2):139–149. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2011.646366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayhew S, Collumbien M, Qureshi A, Platt L, Rafiq N, Faisel A, Lalji N, Hawkes S. Protecting the unprotected: mixed-method research on drug use, sex work and rights in Pakistan's fight against HIV/AIDS. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(Suppl)(2):31–36. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.033670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deering KN, Bhattacharjee P, Mohan HL, Bradley J, Shannon K, Boily MC, Ramesh BM, Isac S, Moses S, Blanchard J. Violence and HIV risk among female sex workers in Southern India. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(2):168–174. doi: 10.1097/olq.0b013e31827df174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization, author. Violence against sex workers and HIV prevention. [7th April 2013]. http://www.who.int/gender/documents/sexworkers.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banghadesh Ministry of Health, AIDS and STD Control Programme. Directorate General of Health Services, author. Report on the second national expanded HIV surveillance. Dhaka, Bangladesh: 2005. p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okal J, Chersich MF, Tsui S, Sutherland E, Temmerman M, Luchters S. Sexual and physical violence against female sex workers in Kenya: a qualitative enquiry. AIDS Care. 2011;23(5):612–618. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hubbard D, Zimba E. Sex work and the law in Namibia: A culture-sensitive approach. Res Sex Work. 2003;6:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Network of Sex work Projects: Respect sex workers' human right: Stop all violence against sex workers. Hong Kong: 2005. [7th April 2013]. http://www.nswp.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health, author. HIV/STI integrated biological and behavioural surveillance survey 2007. Abuja, Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menaker TA, Franklin CA. Commercially sexually exploited girls and participant perceptions of blameworthiness: Examining the effects of victimization history and race disclosure. J Interpers Violence. 2013 Jan 8; doi: 10.1177/0886260512471078. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roxburgh A, Degenhardt L, Copeland J. Posttraumatic stress disorder among female street-based sex workers in the greater Sydney area, Australia. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;24(6):24–28. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shannon K, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Montaner JS, Tyndall MW. Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. BMJ. 2009;339:b2939–b2945. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asowa-Omorodion FI. Sexual and health behaviour of commercial sex workers in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. Health Care Women Int. 2000;21(4):335–345. doi: 10.1080/073993300245186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rushing R, Watts C, Rushing S. Living the reality of forced sex work: perspectives from young migrant women sex workers in northern Vietnam. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50(4):e41–e44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Population Commission (NPC), author The 2006 National Census Report. Abuja: National Population Commission; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.|Wikipedia. Abuja, Nigeria: [5th May 2013]. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abuja. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Society for Family Health, author. National Behavioral Survey: Brothel Based Sex work in Nigeria. Abuja: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dean AG, Dean JA, Burton AH, Dicker RC, Coulombier D, Brendel KA, Smith DC, Sullivan K, Fagan RF, Arner TG. Epi Info Version 6: a word processing, database, and statistics program for epidemiology on microcomputers. Atlanta, Georgia, USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF Macro, author. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Abuja, Nigeria: National Population Commission and ICF Macro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pando MA, Coloccini RS, Reynaga E, Rodriguez Fermepin M, Gallo Vaulet L, Kochel TJ, Montano SM, Avila MM. Violence as a Barrier for HIV Prevention among Female Sex Workers in Argentina. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mbonye M, Nalukenge W, Nakamanya S, Nalusiba B, King R, Vandepitte J, Seeley J. Gender inequity in the lives of women involved in sex work in Kampala, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(Suppl)(1):1–9. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.3.17365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization, author. WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women: summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organisation, author. Putting women's safety first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.SPSS Inc., author SPSS Base 9.0 for Windows User's Guide. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ankomah A, Omoregie G, Akinyemi Z, Anyanti J, Ladipo O, Adebayo S. HIV-related risk perception among female sex workers in Nigeria. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2011;3:93–100. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S23081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health, author. 2010 national HIV sero-prevalence sentinel survey among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Nigeria. Abuja, Nigeria: Department of Public Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]