Abstract

Heterotrimeric G protein α (Gα) subunits possess intrinsic GTPase activity that leads to functional deactivation with a rate constant of ≈2 min-1 at 30°C. GTP hydrolysis causes conformational changes in three regions of Gα, including Switch I and Switch II. Mutation of G202→A in Switch II of Gαi1 accelerates the rates of both GTP hydrolysis and conformational change, which is measured by the loss of fluorescence from Trp-211 in Switch II. Mutation of K180→P in Switch I increases the rate of conformational change but decreases the GTPase rate, which causes transient but substantial accumulation of a low-fluorescence Gαi1·GTP species. Isothermal titration calorimetric analysis of the binding of (G202A)Gαi1 and (K180P)Gαi1 to the GTPase-activating protein RGS4 indicates that the G202A mutation stabilizes the pretransition state-like conformation of Gαi1 that is mimicked by the complex of Gαi1 with GDP and magnesium fluoroaluminate, whereas the K180P mutation destabilizes this state. The crystal structures of (K180P)Gαi1 bound to a slowly hydrolyzable GTP analog, and the GDP·magnesium fluoroaluminate complex provide evidence that the Mg2+ binding site is destabilized and that Switch I is torsionally restrained by the K180P mutation. The data are consistent with a catalytic mechanism for Gα in which major conformational transitions in Switch I and Switch II are obligate events that precede the bond-breaking step in GTP hydrolysis. In (K180P)Gαi1, the two events are decoupled kinetically, whereas in the native protein they are concerted.

Heterotrimeric G proteins are activated by agonist-stimulated G protein-coupled receptors that catalyze the exchange of Mg2+·GTP for GDP on G protein α (Gα) subunits. Upon binding GTP, Gα subunits dissociate from Gβγ heterodimers (1, 2), interact with effector proteins, and thereby control intracellular pathways. Thus, Gαs and Gαi1, 2 of the 16 mammalian Gα isoforms, respectively stimulate and inhibit the catalytic activity of certain isoforms of adenylyl cyclase. However, activation is transient because Gα possesses intrinsic GTPase activity that restores it to the deactivated, GDP-bound state within 10–20 s at 30°C. Inactivation occurs because GTP hydrolysis induces conformational changes in the catalytic and effector-binding sites of Gα, which include two polypeptide segments, called Switch I and Switch II. As a consequence of this transition, the affinity of Gα for effector is reduced whereas the affinity for Gβγ is increased, thereby terminating the cycle of signal transduction. Deactivation can be accelerated by GTPase-activating proteins, which include the regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins (3).

The steady-state rate of Gα-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis is limited by the rate at which GDP is released from the enzyme. Consequently, pre-steady-state kinetic methods are used to measure the single-turnover rate at which GTP is converted to GDP. GTP hydrolysis is initiated by addition of the cofactor Mg2+ to Gα·GTP. Binding of Mg2+ induces a rapid increase in Trp fluorescence emission that reflects rapid conversion to the activated conformation. Fluorescence decays subsequently at a rate that parallels that of GTP hydrolysis: ≈2–4 min-1 at physiological temperature (4, 5).

The crystal structure of Gαi1 bound to Mg2+ and the hydrolysis-resistant analog guanosine-5′-(βγ-imino)triphosphate (GppNHp) shows that two critical catalytic residues, R178 in Switch I and Q204 in Switch II, adopt conformations that do not allow them to participate in catalysis (6, 7). However, when Gα binds the presumptive transition state analog GDP·Mg2+·AlF4-, these residues and a segment of Switch I undergo a conformational rearrangement that affords their direct interaction with the pentacoordinate phosphoryl transition state (6, 8). Trp fluorescence emission is also enhanced in this state (9), and RGS proteins preferentially bind to this conformation of Gα (10–12). Thus, an active-site preordering step may occur before GTP hydrolysis can proceed. We refer to this preordered state as the pretransition state of Gαi1.

The quenching of intrinsic fluorescence that accompanies GTP hydrolysis is attributed to a conformational change in Switch II in which W211 (W207 in transducin) (13) is transferred from a buried site in the enzyme to a solvent-exposed environment. This same conformational change may be responsible for effector release and Gβγ rebinding (14, 15). It is commonly believed that such conformational changes in G proteins occur as a consequence of GTP hydrolysis, although the two events appear to be concerted. Here, we suggest that, rather, these conformational changes are obligate steps in the reaction trajectory itself (Scheme 1). In Scheme 1, Q represents one or more GTP-bound, but low-fluorescence, conformational states that the enzyme must assume before the product complex is formed.

Scheme 1.

From analysis of Gαi1 crystal structures, we inferred earlier that a substantial conformational change in Switch II is concomitant with or precedes the formation of the transient Gαi1·GDP·Pi ternary complex, and we have suggested that this conformational change might be rate-limiting (16, 17).

In the crystal structures of Gαi1, Gαt, and Gαs bound to GTP analogs, Switch II folds into an irregular helix (6, 18, 19) that, at its N terminus, makes hydrogen bond contact with the γ phosphate moiety of the nucleoside triphosphate. We reasoned that, if conformational changes in Switch II are required for catalysis, then mutations that either stabilize or destabilize its structure could affect the single-turnover rate of GTP hydrolysis. Accordingly, we conducted an Ala scan of residues in Switch II and mutated one residue in Switch I. The side chains of the residues that were mutated do not make direct contacts with the guanine nucleotide or Mg+2 in crystal structures of Gαi1. Here, we present a kinetic, thermodynamic, and structural analysis of the catalytic properties of two of the Gαi1 mutants that were produced in this study. The properties of these molecules provide insight into the relationship between conformational change and GTP hydrolysis in G proteins.

Materials and Methods

Purification of Gαi1,Gαi1 Mutants, and RGS4. Nonmyristoylated Gαi1 (20) and 6His-tagged RGS4 (21) were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described. Mutants of Gαi1 were generated by using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene).

Single-Turnover GTPase Assays. Single-turnover GTPase assays were performed at 4°C, as described (21). We bound [γ-32P]GTP (1 μM, 7,000 cpm/pmol) to Gαi1 (10 nM) in HEDL buffer (50 mM Hepes/1 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT/20 ppm of C12E10, pH 8.0) for 15 min at 30°C. Manually run assays were initiated by addition of 25 mM MgSO4 and 200 μM guanosine-5′-O-3-thiotriphosphate (GTPγS), with or without 2–3 nM RGS4. Reactions were quenched in a slurry of 15% charcoal in 50 mM H3PO4 (pH 2.3) at 0°C. We determined [32P]Pi in the supernatant by scintillation counting. We fit the [32P]Pi released at each time point to the function cpmt = cpmo(1 - e-khyd*t). Assays were performed also in the quench–flow mode by using a Quench–Flow SFM4/Q rapid-mixing device (Biologic, Grenoble, France). For wild-type and K180P(Gαi1), reaction courses were carried out for 5 and 20 min, respectively, to derive the kinetic constants presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Pre-steady-state rates for GTP hydrolysis and conformational change for wild-type and mutant Gαi1 in the presence and absence of RGS4.

| Protein | khyd, min-1 | kPi, min-1 | kW, min-1 | kMANT, min-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gαi1 | 0.46 (0.05) | 0.21 (0.03) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.52 (0.03) |

| (G202A)Gαi1 | 4.2 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.2) | 4.9 (0.1) | 4.9 (0.2) |

| (K180P)Gαi1 | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | 3.6 (0.6) | 0.07 (0.01) |

| (K180A)Gαi1 | 0.31 (0.02) | 0.22 (0.05) | 0.25 (0.3) | 0.41 (0.01) |

| (G202A/K180P)Gαi1 | 4.8 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.6) | 5.5 (0.3) | 5.1 (0.4) |

| Gαi1:RGS4 | 5.2 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.6) | 5.5 (0.8) | 5.2 (0.4) |

| (G202A)Gαi1:RGS4 | 5.7 (0.6) | 6.9 (0.2) | 8.3 (1.2) | 5.4 (0.5) |

| (K180P)Gαi1:RGS4 | 7.6 (0.5) | 6.2 (0.5) | 7.2 (1.1) | 6.1 (0.8) |

khyd is the first-order rate constant for GTP hydrolysis, as measured by acid quench of the GTPase reaction. kPi is the rate constant for release of Pi from the Gαi1·GDP·Pi as measured by a coupled-enzyme reaction, which measures the generation of free phosphate. kMANT and kW are the rate constants for the decrease in fluorescence of bound MANT-GDP and Trp211, respectively. Assays were conducted at 0°C to determine khyd and at 4°C for determination of kMANT, kW, and kPi. Kinetic parameters listed are average values determined from three experiments. Standard errors of measurement are given in parentheses.

Stopped-Flow Fluorescence Single-Turnover Assays of GTP and 2′(3′)-O-(N-Methylanthraniloyl)-Guanosine-5′-Triphosphate (mGTP) Hydrolysis. The decrease in intrinsic Trp fluorescence of Gαi1 during hydrolysis of bound GTP, or in N-methyl-anthranoyl (MANT) fluorescence during hydrolysis of mGTP, were measured by using either a SFM4 (Biologic) or an SX18MV-R (Applied Photophysics, Surrey, U.K.) stopped-flow instrument, as described (22). Proteins (500 nM) were preloaded with 2.5 μM GTP or 5.2 μM mGTP in HEDL buffer for 15 min at 30°C. GTP/mGTP-loaded Gαi1. Reactions were initiated with 30 mM MgSO4 in the absence or presence of RGS4 (final concentration 160 nM). Trp fluorescence at 340 nm was excited at 290 nm. MANT fluorescence was followed by excitation at 366 nm and emission at 440 nm. The time dependences of Trp and MANT fluorescence emission were fit to first-order exponential equations to derive rate constants kW and kMANT, respectively. For wild-type Gαi1 and mutants with low Trp quenching rates, reactions were followed for 5 min by using an LS50B spectrofluorometer (Perkin–Elmer).

Stopped-Flow Single-Turnover Assay of Phosphate Release from Gαi1·GDP·Pi. The rate of release of free Pi from the Gαi1·GDP·Pi complex was determined by using the EnzCheck assay kit (Molecular Probes) as described (23). Gαi1 (50 μM) in Mg2+-free HEDL buffer was incubated with 10 mM GTP in the presence or absence of RGS4 (16 μM) for 15 min at 30°C and then passed through a gel-filtration spin column to remove excess GTP. Assays were initiated by addition of 250 mM MgSO4/200 μMGTPγS/0.35 mM 2-amino-6-mercapto-methylpurine riboside/15 units/ml-1 purine nucleoside phosphorylase in a stopped-flow apparatus (Biologic). The increase in absorbance at 355 nm was fit to a single-order exponential equation to yield the rate constant kPi.

Analysis of Reaction Models. Progress curves for the consumption of Gαi1·GTP·Mg2+ (T) and the formation of Gαi1·GDP·Mg2+ (D), were modeled by using the mechanism shown in Scheme 2.

|

[1] |

Concentrations of these species are normalized to 1.0 in arbitrary units, and initial conditions are set at [T]t = 0 = 1.0 and [D]t = 0 = 0.0. Progress curves for T, D, and Q are taken from Trp quenching of Gαi1·GTP (modeled with rate constant kW) and 32Pi production (rate constant khyd) upon addition of Mg2+. Q, the GTP-bound Gαi1 species in which Trp fluorescence is quenched, cannot be observed directly, and its concentration is derived from the following conservation relation: [Q] = 1 - [T] - [D]. Values for k1, k-1, k2, and k3 in Scheme 2 were determined by using simplex and least-squares algorithms implemented in the computer program scientist v2.0 (MicroMath Scientific, St. Louis).

Scheme 2.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC). Experiments were performed by using a VP microcalorimeter (MicroCal, Amherst, MA). A typical titration involved 15–20 injections at 3-min intervals of 8-μl aliquots of RGS4 (450 μM in 50 mM Tris/1 mM EDTA/2 mM DTT/3 mM MgSO4, pH 8.0) into 1.344 ml of wild-type or mutant Gαi1 (50 μM) in the same buffer. For experiments that involved binding of Gαi1·GDP·Mg2+·AlF4- complexes to RGS4, the buffer also contained 5 μM GDP, 16 mM NaF, and 40 μM AlCl3. The sample cell was stirred at 400 rpm. The heats of dilution of the RGS4 in the buffer alone were subtracted from the titration data. The ITC binding data were fit to a single-site binding model by using origin software (Microcal) to determine the association constant Ka, thermodynamic parameters, and standard errors of measurements for these values, as described (24).

Crystallization and Structure Determination. Crystals of (K180P)Gαi1 complexes were produced by the hanging-drop method. For crystallization of the complex containing GDP·Mg2+·AlF4- (GDP·AlF), 3 μl of 10–15 mg/ml protein in 20 mM Hepes buffer containing 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 5 μM GDP, 16 mM MgCl2, 16 mM NaF, and 40 μMAlCl3 was mixed with equal amounts of 2.1 M ammonium sulfite in 0.1 M sodium acetate reservoir buffer and set up as hanging drops. Crystals were cryoprotected in reservoir buffer containing 15% (vol/vol) glycerol. Crystals containing Gpp(NH)p·Mg2+ (GNP) were prepared as described (7). Monochromatic x-ray data were measured at beam line 5.0.1 at the Advanced Light Source (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA) for crystals of (K180P)Gαi1·GDP·AlF and at the beam line BM-19 at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL) for crystals of (K180P)Gαi1·GNP. Data sets extended to 1.5 and 2.0 Å for the Gpp(NH)p- and GDP·AlF4-containing crystals. Data sets were measured by the oscillation method in 0.5° frames and processed by using the hkl 2000 package (HKL Research, Charlottesville, VA) (25). Structures were determined by molecular replacement by using the 1GFI and 1CIP coordinate sets as starting models. Atomic models were refined by using the cns 1.1 program package (26), withholding 5% of the data for computation of Rfree. Parameter files from Engh and Huber (27) were used for protein atoms; files for AlF4-, GTP, and GDP were obtained from the Hetero-compound Information Centre, Uppsala (28). Atomic models were refit into σ-weighted 2Fo - Fc electron-density maps by using the program o (29).

Difference-Distance Computations. Calculations were carried out by using a modified version of the Difference Distance Matrix Plot (DDMP) program (Center for Structural Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT).

For additional information regarding experimental methods, see Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Results

Mutational Acceleration and Decoupling of GTPase Activity. We constructed a set of Gαi1 mutants in which Switch II residues 202–212 (excluding 203 and 204), were individually replaced by Ala. Also, proteins were created in which K180 in Switch I was replaced with Pro, its cognate in the sequence of Gαq (30), or with Ala. The K180P/G202A double mutant was constructed also. All of the recombinant mutant proteins were produced in E. coli at levels comparable with that of the wild-type protein. The guanine nucleotide-exchange activity of each mutant was determined by a filter-binding assay using [35S]-labeled GTPγS, and the GTPase activity of the mutants was determined by a single-turnover assay using [γ32P]GTP (20). The first-order rate constants for nucleotide exchange and GTP hydrolysis for most of the mutants were similar to that of wild-type Gαi1, and these proteins were not studied further. In contrast, the hydrolysis rates measured for the (K180P), (G202A), and (K180P and G202A) mutants differed substantially from that of the wild type.

Events triggered by Mg2+ activation of the GTP complexes of the mutant Gαi1 proteins were followed by four different pre-steady-state assays conducted in the presence and absence of the GTPase activator RGS4. These results of these experiments are summarized in Table 1.

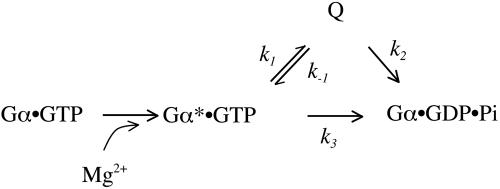

The single-turnover rate of GTP hydrolysis from Gαi1·[γ32P]GTP is measured by the 32Pi released after acid-quench of the reaction at various time points after addition of Mg2+ (Fig. 1A). Because Gαi1 is denatured by the quench, the quantity of 32Pi measured in the assay reflects its rate of production rather than the rate at which it dissociates from the Gαi1·GDP·Pi complex. In all cases, the evolution of phosphate could be fit to a first-order rate equation, characterized by the rate constant khyd (Table 1). Analysis of data taken at 100-ms intervals within the first 2 s of the reaction phase showed no evidence of a burst-phase for any of the Gαi1 proteins (data not shown). The GTPase rate constant for (G202A)Gαi1 is ≈10-fold greater than that of the wild-type protein, whereas the K180P mutation, as had been shown earlier (30), reduced khyd to <15% that of wild-type Gαi1.

Fig. 1.

Single-turnover kinetics of 32Pi production and conformational change. (A) Samples of Gαi1 (15 nM) were preloaded with [γ-32P]GTP on ice. GTP hydrolysis was initiated by addition of Mg2+ (35 mM) in the presence of 200 μM GTPγS in the absence (open symbols) or presence of 3–4 nM RGS4 (filled symbols) at 4°C. Wild-type Gαi1, black open or filled circles; (G202A)Gαi1, blue filled squares; (K180P)Gαi1, red open or filled squares. Computed fit to single-exponential rate equations is shown by black traces. (B) Fluorescence emission was monitored at 340 nm after excitation at 285 nm. Wild-type Gαi1 (500 nM) was used. Color-coding for wild type, (G202A)Gαi1, and (K180P)Gαi1 is the same as described for A.

That mutations of either of these residues might alter the rate of GTP hydrolysis is not surprising. The main-chain amide groups that follow both residues in sequence form hydrogen bonds to the γ phosphate of GppNHp (7). In the GDP·AlF complex of Gαi1, the ζ amino group of K180 lies within hydrogen bond distance of the axial hydroxyl ligand of AlF4-. This hydroxyl group mimics the nucleophile in GTP hydrolysis, and therefore, it might be inferred that K180 participates in the catalytic mechanism. However, khyd for (K180A)Gαi1 is similar to that of wild-type Gαi1 (Table 1 and Fig. 1A), suggesting that the effect of the K→P mutation is not due to the loss of the Lys side chain but rather to its substitution by a constrained pyrrolidine ring. If both K180P and G202A mutations are present, the latter has a fully dominant effect on the GTP hydrolysis rate. The GTPase activity of recombinant (K180P/ G202A)Gαi1 is similar to that of the G202A mutant.

In wild-type Gαi1, Mg2+ binding is accompanied by a rapid increase in fluorescence at 340 nm, which is attributed to a change in the environment of the Trp-W211 in Switch II. Fluorescence subsequently decays in conjunction with GTP hydrolysis such that the first-order rate constants for the two processes are the same. khyd and kW are also nearly equivalent for the G202A mutant and ≈10-fold greater than the corresponding rate constants for the wild-type protein (Fig. 1B and Table 1). In contrast, the Trp quenching rate of (K180P)Gαi1 is similar to that of the G202A mutant, even though (K180P)Gαi1 hydrolyzes GTP at only 15% of the wild-type rate. The K180P mutation effectively decouples the transformations associated with GTP hydrolysis and the perturbation of the Trp in Switch II. For the K180P/G202A double mutant, khyd and kW are similar to the corresponding rate constants for (G202A)Gαi1.

Subsequent to GTP hydrolysis, inorganic phosphate is released rapidly from the wild-type Gαi1·GDP·Pi complex. Phosphate release is monitored by a fast-coupled enzyme reaction that produces a fluorescent product (23) (see Fig. 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). For Gαi1 and its mutants, product release fits a first-order rate equation with no apparent lag phase (Table 1). Rate constants kPi for all proteins, in experiments conducted in the absence of RGS4, are 50–70% of their corresponding values of khyd. The differential could in part reflect insensitivity of the coupled enzyme reaction at low Pi concentration. However, kPi for (K180P/G202A)Gαi1, which possesses a high GTPase rate, is also one-half of that of kPi and consistent with a short but detectable lifetime for the tertiary GDP·Pi–enzyme complex. In the presence of RGS4, the rate of phosphate release does not differ significantly from that of hydrolysis.

The single-turnover kinetics of the GTPase reaction can also be measured by the rate at which MANT fluorescence of mGTP is quenched upon the release of weakly bound mGDP from Gαi1 (31). For Gαi1 and all mutants, the apparent first-order rate constant for fluorescence decay (kMANT) was found to be within 25% of khyd (Table 1 and see Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

The effects of RGS4 on the K180P mutant were similar to those observed (30), and for G202A and the K180P/G202A double mutants, acceleration of GTP hydrolysis and fluorescence decay were relatively minor because the basal activities of these mutants are so high. The affinity measurements described below are more informative of the interactions of these proteins with RGS4.

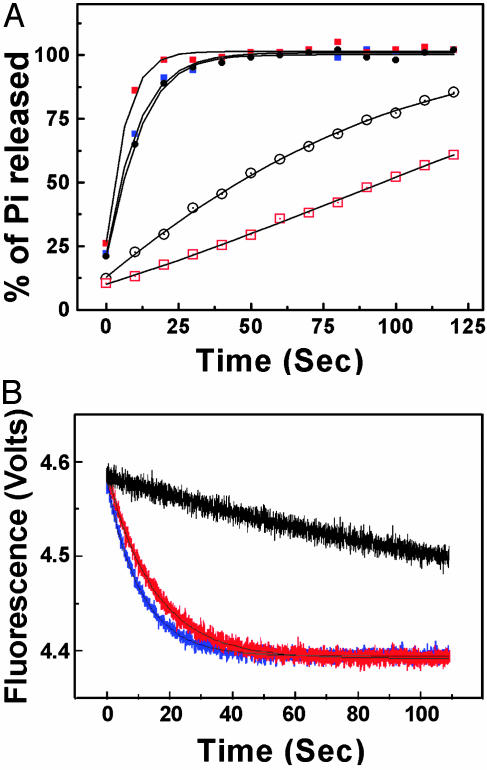

K180P Perturbs the Structure of the Pretransition State for GTP Hydrolysis. To understand the structural basis for the effects of the K180P and G202A mutations, we set out to determine the structures of the mutant proteins bound to GNP and GDP·AlF. Attempts to crystallize (G202A)Gαi1 were unsuccessful, but the K180P mutant could be readily crystallized. The structures of the GNP and GDP·AlF complexes of (K180P)Gαi1 were determined at resolutions of 1.5 and 2.0 Å and refined to Rfree values of 0.21 and 0.23, respectively (see Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Relative to the respective structures of wild-type Gαi1 (determined at 1.5- and 2.2-Å resolution), the rms deviations in the positions of corresponding main chain atoms are only 0.18 and 0.27 Å, indicating the absence of substantial global changes in structure.

Structural differences at the site of mutation and within the active site of (K180P)Gαi1 are clearly evident. The Pro substitution constrains the main-chain φ and Ψ angles of residue 180 to similar values (within 2° for both angles) in the GNP and GDP·AlF states, whereas in wild-type Gαi1, φ and Ψ both decrease by ≈5–7° in the transition from the former state to the latter state. The main-chain angles at P180 for the GDP·AlF complex are more similar to those of the GNP complex of the wild-type protein than they are to the GDP·AlF complex. Thus, substitution of Pro for Lys both drives the local conformation of Switch I toward the ground (GNP) state and appears to impose a torsional constraint.

The Mg2+ binding site of Gαi1 is also altered in the GDP·AlF Complex (Fig. 2). S47, a direct Mg2+ ligand, shows static disorder (see Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Asp-200, a second-shell ligand that is highly conserved in the Ras superfamily, adopts a different side-chain conformation than that observed in the wild-type protein. As a consequence of these changes, a cooperative hydrogen bond network involving Mg2+, one of two water ligands, together with D200 and S47, is partially disrupted. No comparable differences are apparent between the GNP complex of (K180P)Gαi1 and that of the wild type.

Fig. 2.

Catalytic sites of Gαi1· GDP·Mg2+·AlF4- complexes. Atoms are rendered as follows: carbon, gold; nitrogen, cyan; oxygen, red; fluorine, yellow; aluminum, gray; and phosphorus, green. Mg2+ is shown as a blue sphere; α and β phosphate oxygen atoms are shown. Metal-coordination interactions are indicated by gray dashed lines, and hydrogen bonds are indicated by red dashed lines. (A) Wild-type Gαi1. (B) For (K180P)Gαi1, major (a, occupancy, ≈0.25) and minor (b, occupancy, ≈0.75) conformations of Ser-47 are shown.

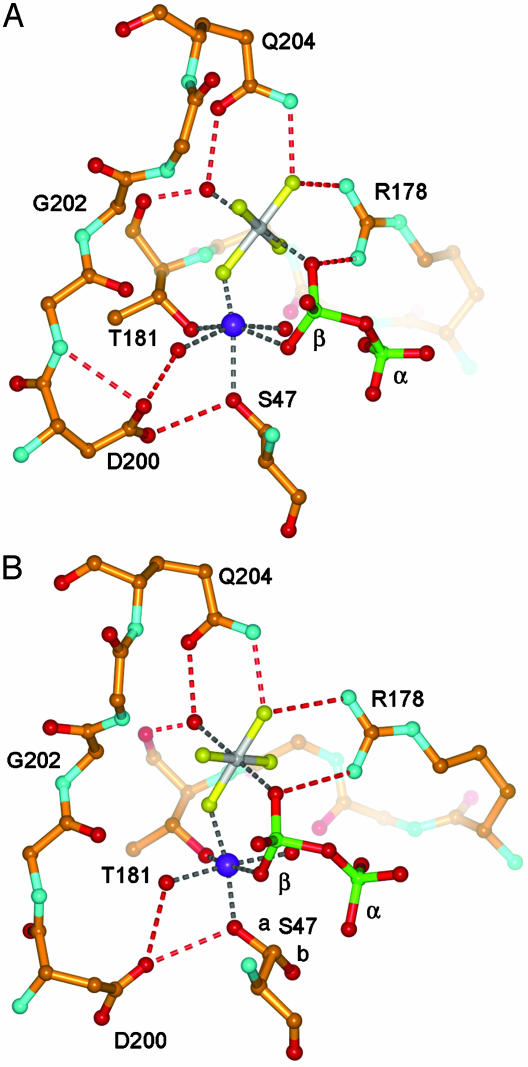

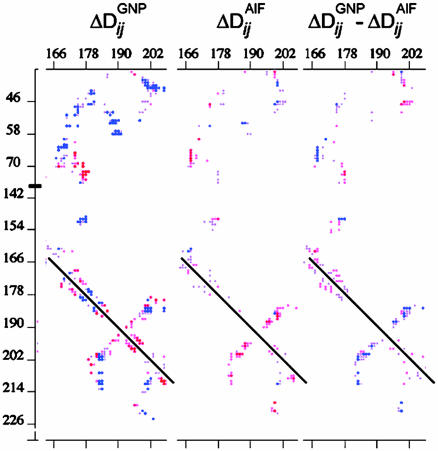

At a more global level, it is evident that the K180P mutation has different structural consequences in the GNP and GDP·AlF-bound states. The latter is manifested in the changes in inter-Cα distances induced by the K180P mutation (i.e., ΔDij, the change in the distance between the Cα atoms of residue i and residue j in (K180P)Gαi1 relative to that of the wild type; Fig. 3). The magnitudes of interresidue changes are typically small (<0.7 Å) but clearly segmental. Among residues within a 10-Å radius of residue 180, the P-loop (residues 40–50), Switch I (residues 166–183), and Switch II (residues 200–213) are particularly altered (Fig. 3 A and B). The magnitudes of the interresidue shifts due to the transformation from the GNP-bound to the GDP·AlF-bound states differ in the wild-type and P180 backgrounds. This apparent nonadditivity of the two perturbations (mutation vs. change in ligand) is evident in Fig. 3C, in which the changes in pairwise Cα–Cα distances due to the K180P mutation in the GNP-bound proteins are subtracted from the corresponding distance changes in the GDP·AlF-bound proteins (i.e., ΔDijGNP -ΔDijAlF). It is reasonable to conclude that the K180P mutation has specific effects on the transformation of the ground state of Gαi1 to the pretransition state represented by the GDP·AlF complex.

Fig. 3.

Difference-distance analysis of wild type and (K180P)Gαi1 in complexes with GppNHp·Mg2+ and GDP·Mg2+·AlF4. Changes in contacts between Cα in residues 165–207 in Gαi1 (rows) and residues 35–76 and 140–226 in (K180P)Gαi1 (columns) for the GNP-bound complexes (Left), and the AlF-bound complexes (Center) are shown. In Right, the elements from the AlF matrix are subtracted from the corresponding elements in the GNP matrix. Values are σ-weighted and color-coded according to direction and magnitude (red, negative; blue, positive). Contour values range from ±σ to 0. Matrix elements corresponding to residue pairs separated by >10 Å were set at 0. The dark line represents self-vectors (i = j).

G202A Stabilizes and K180P Perturbs the Pretransition State for GTP Hydrolysis. Evidence that the K180P mutation differentially perturbs the ground and pretransition states of Gαi1 led us to investigate the affinity of RGS4 for the GNP-bound and GDP·AlF-bound complexes of the G202A and K180P mutants of Gαi1. Because RGS4 binds preferentially to the GDP·AlF complex of Gαi1 (10), mutation-induced perturbation of the structure of this state might be reflected in a change in its affinity for RGS4. Similarly, differences in the affinity of RGS4 for GDP- or GNP-bound Gαi1 mutants relative to the wild-type complexes are indicative of changes in the structure of the ground state.

As measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (Table 2), the GNP complexes of (K180P)Gαi1 and (G202A)Gαi1 are similar to that of wild-type Gαi1 in their affinity for RGS4. The GDP-bound form of (K180P)Gαi1, like the wild-type protein, has low affinity for RGS4, whereas (G202A)Gαi1·GDP binds more tightly. Last, the GDP·AlF complex of (K180P)Gαi1 has less affinity for RGS4 than (G202A)Gαi1 or the wild-type protein. Therefore, it appears that the G202A mutation stabilizes the pretransition state of Gαi1, whereas the K180P mutation perturbs this state. Nevertheless, (K180P)Gαi1, (G202A)Gαi1, and Gαi1 all attain similar levels of GTPase activity in the presence of RGS4 (Table 1). Posner et al. (30) found that the EC50 of RGS4 for stimulation of the steady-state GTPase activity of (K180P)Gαi1 in the presence of M2 receptors is 10-fold higher than that for wild-type Gαi1, but its efficacy for the two Gα proteins is the same.

Table 2. Affinity of RGS4 for nucleotide-bound complexes of wild-type and mutant Gαi1.

| Protein | GDP | GppNHp | GDP·AlF4- | Ratio of GppNHp/GDP·AlF4- |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gαi1 | 430 (230) | 5.2 (0.9) | 0.13 (0.1) | 43 |

| (G202A)Gαi1 | 18 (2) | 1.4 (0.1) | 0.13 (0.8) | 11 |

| (K180P)Gαi1 | 670 (210) | 2.3 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.1) | 2 |

Data are expressed as Kd(in μM). Standard errors of measurement are given in parentheses.

Discussion

For Gαi1, GTP hydrolysis and conformational change are seemingly concerted. Single-turnover assays designed to measure the rate of GTP hydrolysis, product (Pi) release, and conformational change in Switch II yield progress curves that can be fit with similar first-order rate constants. In the presence of RGS4, all three events are apparently accelerated by the same factor. Release of Pi from the Gαi1·GDP·Pi occurs too rapidly to be distinguished accurately from the rate at which it is produced within the enzyme. Less apparent is the relationship between the reaction trajectory for GTP hydrolysis and the conformational change that is signaled by decay of the Mg2+-induced fluorescence of W211.

Mutation of G202 to Ala increases the turnover rate for GTP hydrolysis ≈10-fold. We have not succeeded in crystallizing this mutant and, therefore, can offer only a speculative rationale for its effect on GTP hydrolysis. In a model of (G202A)Gαi1·GTP based on the crystal structure of the wild-type protein, steric conflict arises from a 2-Å contact between the methyl side chain of A202 and the carbonyl oxygen atom of T181. This distance increases to 2.5-Å in the model of the (G202A)Gαi1 complex with GDP·AlF. By destabilizing the ground state (i.e., Gαi1·Mg2+·GTP), the G202A mutation may promote the structural transition to the pretransition state that is mimicked by the GDP·AlF complex. Accordingly, the selectivity of RGS4 for the Gαi1·GDP·AlF complex increases 4-fold in the background of the G202A mutation (Table 2).

The kinetic behavior of the K180P mutant suggests that otherwise concerted events in Gα-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis can be disengaged. That Trp quenching occurs 50-fold faster than GTP hydrolysis indicates that two distinct species arise after addition of Mg2+ to the Gαi1·GTP complex as indicated in the kinetic mechanism shown in Scheme 2. In this mechanism, species Q corresponds to GTP-bound (K180P)Gαi1 in which intrinsic Trp fluorescence is quenched, and Gα*·GTP is the Mg2+-activated complex with high intrinsic Trp fluorescence. Breakdown of Gαi1·GDP·Pi is considerably more favorable than formation, as indicated by insensitivity of the enzyme to inhibition by phosphate (32).

The rate constants kW and khyd (Table 1) are first-order approximations to the progress curves for the disappearance of Gα*·GTP (Fig. 1B) and appearance of Gα·GDP·Pi (Fig. 1A), respectively. Because state Q is not directly observable, the progress curves cannot be used to derive a unique set of values for all four constants in Scheme 2. However, the progress curves do place severe limits on the values of these rate parameters. Q must lie on a catalytically productive pathway because models in which the value of k2 is constrained to zero give poor fits to the progress curves. Such models produce clearly biphasic time courses that are readily distinguished from the observed time courses. Further, a model in which k3 is constrained to zero converges well to a solution with k1 = 3.9 min-1, k-1 ≈ 0, and k2 = 0.33 min-1. The SEMs of these fits to the experimental data are less than the standard errors of measurement. The kinetic parameters so derived point to a simple, irreversible reaction: T→Q→D, in which Q is an obligate reaction intermediate. Unconstrained fitting of all four parameters produce values of k1 and k-1 similar to those presented above, but k2 and k3 converge to 0.28 min-1 and 0.19 min-1, respectively. Although conversion of Q to Gα·GDP·Pi is modeled as an irreversible step, the kinetic data presented here do not rule out the possibility of rapid interconversion of the two species, as has been considered for GTPase-activating protein-stimulated Ras (33).

The intermediate, Q, that is proposed to arise in the GTPase reaction catalyzed by (K180P)Gαi1, must adopt a conformation in which the fluorescence of Trp-211 is substantially quenched but is able to support GTP hydrolysis at a rate close to that of wild-type Gαi1 (k2 ≈ 0.3 min-1). The structures observed for wild-type and mutant Gαi1 bound to GDP or GDP·Pi, in which Switch II is substantially displaced or disordered, are not reasonable models for the Q state because the catalytic Gln in these structures is not in position to orient a water molecule for nucleophilic attack on GTP(14–16, 34). On the other hand, the GDP·Mg2+ complex of transducin (Gαt), a close homolog of Gαi1, is a viable model for the Q state (14). Relative to the GTPγS·Mg2+-bound complex (18) (which is virtually identical to that of Gαi1), the conformation of Switch II in Gαt·GDP·Mg2+ is altered such that Trp-207 (the counterpart of Trp-211 in Gαi1) is exposed to solvent. In this structure, Gln-200 (counterpart to Gln-204) remains in position to participate in catalysis, as is evident from modeling GTP into the active site.

The forgoing results indicate that mutation of a single residue can decouple the kinetics of conformational change in Switch II of Gαi1 from those of GTP hydrolysis. Conformational change, moreover, appears to be an obligate step in catalysis rather than a consequence of the reaction. We infer that similar intermediate conformational states occur in wild-type Gα, but are so nearly concerted with the chemical steps that they cannot be experimentally deconvoluted from them. It is important to note that (K180P)Gαi1 is not catalytically defective. RGS4 (although with lowered potency) stimulates the GTPase activity of the K180P mutant to wild-type levels. Therefore, it appears that the coordination of conformational with chemical steps is compromised by this mutation. The K180P mutation perturbs the structure of the GDP·AlF state, and this perturbation is manifested in loss of affinity for RGS4, which preferentially binds this state of Gαi1. Structural changes induced by the K180P mutation differentially affect the ground and pretransition states. In contrast, the G202A mutation appears to maintain chemomechanical coupling while speeding the GTPase reaction, thereby mimicking the action of RGS4. It is remarkable that the G202A mutation is also fully able to reverse the effects of K180P.

The separation of conformational from catalytic events in K180P raises the question whether the rate of functional deactivation of (K180P)Gαi1 corresponds more closely to the increased kW or to the decreased kPi. Deactivation of Gαi is best measured kinetically as the decay of GIRK channel K+ conductance in frog oocytes upon agonist removal (35, 36). Preliminary experiments by Q. L. Zhang and C. Doupnik (University of South Florida, Tampa; personal communication) suggest that (K180P)Gαi1 deactivates with a rate slower than that of wild-type, consistent with the idea that deactivation tracks with slowed GTP hydrolysis (and sequestration of Gβγ by Gα·GDP) rather than with the accelerated relaxation of Switch II.

The value of mutational analysis is realized in the insights gained into the function of the native protein. In this case, mutagenesis, together with a variety of other biochemical and structural observations, provides evidence for two distinct dynamic processes that underlie the reaction kinetics of Gαi1. The first of these corresponds to the conformational changes, primarily in Switch I, observed in the formation of the GDP·AlF-bound complex (6, 8); the second involves the reorganization of Switch II. These structural rearrangements are both required to position catalytic groups on the enzyme for transition state stabilization and to promote bond cleavage and phosphate release by eliminating hydrogen bond contact with the γ phosphate of GTP (16, 17). The rather long turnover rates characteristic of regulatory GTPases may, therefore, reflect a requirement for synchrony in the conformational and chemical events in their catalytic sites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank staff at the Structural Biology Center, Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL), and Advanced Light Source (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA) for assistance with data collection. We especially thank Craig Doupnik and Qing Li Zhang for sharing their data with us before publication, and Arne Strand for his assistance with the kinetic-modeling calculations. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK46371 (to S.R.S.) and GM30355 (to E.M.R.), Welch Foundation Grants I-1229 (to S.R.S.) and I-0982 (to E.M.R.), and a John W. and Rhonda K. Pate Professorship (to S.R.S.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: Gα, G protein α; RGS, regulators of G protein signaling; GppNHp, guanosine-5′-(βγ-imino)triphosphate; GNP, GppNHp·Mg2+; GDP·AlF, GDP·Mg2+·AlF4-; GTPγS, guanosine-5′-O-3-thiotriphosphate; MANT, N-methyl-anthranoyl; mGTP, 2′(3′)-O-(N-methylanthraniloyl)-guanosine-5′-triphosphate.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 1SVK and 1SVS for (K180P)Gαi1·GDP·Mg2+·AlF4- and (K180P)Gαi1·GppNHp·Mg2+, respectively].

References

- 1.Sprang, S. R. (1997) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66, 639-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilman, A. G. (1987) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56, 615-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross, E. M. & Wilkie, T. M. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 795-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higashijima, T., Ferguson, K. M., Smigel, M. D. & Gilman, A. G. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 757-761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips, W. J. & Cerione, R. A. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 15498-15505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman, D. E., Berghuis, A. M., Lee, E., Linder, M. E., Gilman, A. G. & Sprang, S. R. (1994) Science 265, 1405-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman, D. E. & Sprang, S. R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 16669-16672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sondek, J., Lambright, D. G., Noel, J. P., Hamm, H. E. & Sigler, P. B. (1994) Nature 372, 276-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higashijima, T., Ferguson, K. M., Sternweis, P. C., Ross, E. M., Smigel, M. D. & Gilman, A. G. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 752-756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berman, D. M., Kozasa, T. & Gilman, A. G. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27209-27212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tesmer, J. J. G., Berman, D. M., Gilman, A. G. & Sprang, S. R. (1997) Cell 89, 251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slep, K. C., Kercher, M. A., He, W., Cowan, C. W., Wensel, T. G. & Sigler, P. B. (2001) Nature 409, 1071-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faurobert, E., Otto-Bruc, A., Chardin, P. & Chabre, M. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 4191-4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambright, D. G., Noel, J. P., Hamm, H. E. & Sigler, P. B. (1994) Nature 369, 621-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mixon, M. B., Lee, E., Coleman, D. E., Berghuis, A. M., Gilman, A. G. & Sprang, S. R. (1995) Science 270, 954-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berghuis, A. M., Lee, E., Raw, A. S., Gilman, A. G. & Sprang, S. R. (1996) Structure (London) 4, 1277-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raw, A. S., Coleman, D. E., Gilman, A. G. & Sprang, S. R. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 15660-15669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noel, J. P., Hamm, H. E. & Sigler, P. B. (1993) Nature 366, 654-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sunahara, R. K., Tesmer, J. J. G., Gilman, A. G. & Sprang, S. R. (1997) Science 278, 1943-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, E., Linder, M. & Gilman, A. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 237, 146-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berman, D. M., Wilkie, T. M. & Gilman, A. G. (1996) Cell 86, 445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lan, K. L., Zhong, H., Nanamori, M. & Neubig, R. R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33497-33503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webb, M. R. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 4884-4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiseman, T., Williston, S., Brandts, J. F. & Lin, L. N. (1989) Anal. Biochem. 179, 131-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J. S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., et al. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D 54, 905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engh, R. A. & Huber, R. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 392-400. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleywegt, G. J. & Jones, T. A. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D 54, 1119-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones, T. A., Zou, J. Y., Cowan, S. W. & Kjeldgaard, M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 110-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Posner, B. A., Mukhopadhyay, S., Tesmer, J. J., Gilman, A. G. & Ross, E. M. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 7773-7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Remmers, A. E., Posner, R. & Neubig, R. R. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13771-13778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleuss, C., Raw, A., Lee, E., Sprang, S. & Gilman, A. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 9828-9831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips, R. A., Hunter, J. L., Eccleston, J. F. & Webb, M. R. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 3956-3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman, D. E. & Sprang, S. R. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 14376-14385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chuang, H. H., Yu, M., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 11727-11732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doupnik, C. A., Davidson, N., Lester, H. A. & Kofuji, P. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 10461-10466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.