Abstract

Introduction

Hypomelanosis of Ito is a rare neurocutaneous disorder, characterized by streaks and swirls of hypopigmentation following the lines of Blaschko that may be associated to systemic abnormalities involving the central nervous system and musculoskeletal system. Despite the preponderance of reported sporadic hypomelanosis of Ito, few reports of familial hypomelanosis of Ito have been described.

Case presentation

A 6-month-old Caucasian girl presented with unilateral areas of hypomelanosis distributed on the left half of her body and her father presented with similar mosaic hypopigmented lesions on his upper chest. Whereas both blood karyotypes obtained from peripheral lymphocyte cultures were normal, a 16% trisomy 2 mosaicism was found in cultured skinfibroblasts derived from a hypopigmented skin area of her father.

Conclusions

Familial cases of hypomelanosis of Ito are very rare and can occur in patients without systemic involvement. Hypomelanosis of Ito constitutes a non-specific diagnostic definition including different clinical entities with a wide phenotypic variability, either sporadic or familial. Unfortunately, a large number of cases remain misdiagnosed due to both diagnostic challenges and controversial issues on cutaneous biopsies in the pediatric population.

Keywords: Hypomelanosis of Ito, Trisomy 2 mosaicism, Familial hypomelanosis of Ito, Neurocutaneous disorder, Blaschko lines

Introduction

Hypomelanosis of Ito (HMI) is a neurocutaneous phenotype characterized by hypopigmented anomalies along the Blaschko lines, with systemic abnormalities involving the central nervous and muscle-skeletal systems. It was firstly described as incontinentia pigmenti achromians in 1952 [1]. Because of its complex diagnosis the precise prevalence is difficult to estimate, but it has been calculated that HMI is present in 1 in 3,000 to 1 in 10,000 children [2]. Both sexes are affected with an approximately 2:1 female preponderance [3]. The clinical manifestations vary from small hypopigmented areas to hemisomatic large hypopigmented whorls. The streaks can be unilateral or bilateral and, generally, they follow the lines of Blaschko. Lesions appear within the first year of life in about three quarter of the patients. The different pigmented skin areas correspond to the distribution of the two distinct cell clones with different pigment potential in single individuals. The extra-cutaneous manifestations (such as scoliosis, vertebral anomalies and craniofacial malformations) involve the central nervous system and muscle-skeletal system in 33 to 94% of the cases, respectively [4]. However, cardiac, genitourinary and ophthalmic anomalies have been described. These extra-cutaneous manifestations probably do not reflect the variability of one single disorder, but can be due to the presence of different genetic defects. Usually HMI is considered a sporadic disorder, but dominant and recessive (including X-linked) inheritance has also been reported [1-3]. HMI can be due to gametic half chromatid or somatic mutations, or to chromosomal mosaicisms [5], which have been demonstrated in some of the affected patients by means of skin biopsies. Moreover, an association between HMI and ring chromosome 20, trisomy of chromosome 13, and other cytogenetic abnormalities have been described [2]. In this paper we present the clinical and cytogenetic characterization of a familial case of HMI (father and daughter), and we analyze all the familial cases of HMI reported in scientific literature. The criteria set forth by Ruiz-Maldonado et al. for the diagnosis of HMI were used [6]. Chromosomes were processed by standard GTG- and/or QFQ-banding techniques and analyzed at a resolution of 400 bands for a haploid set [International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN), 2013] for both the peripheral blood and fibroblasts from skin biopsy. A minimum of 100 metaphase spreads from two separate cultures for the peripheral blood, and six for the skin biopsy, were examined.

Case presentation

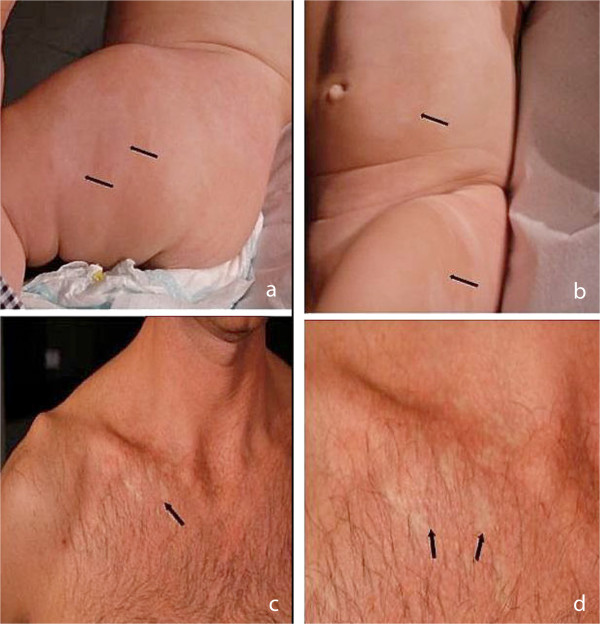

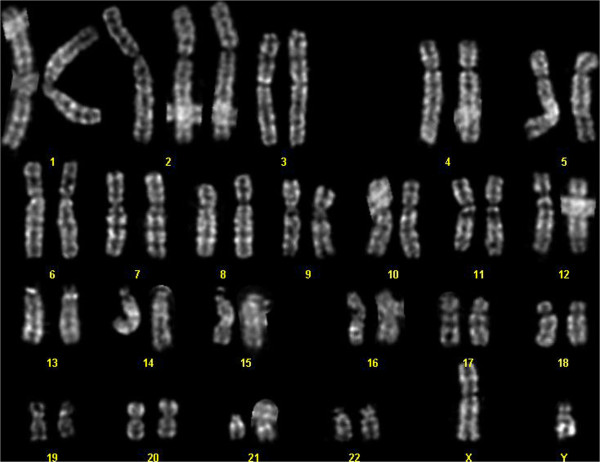

A 6-month-old Caucasian girl presented to our department for the evaluation of right hemisomatic hypopigmented streaks of the trunk and of one leg noted at 3-months-old after sun exposure. At no time were vesicobullous, lichenoid, or verrucous lesions observed and on clinical examination she did not show any other extra-cutaneous manifestations. Her growth and development since birth were within normal limits. Her physical examination was unremarkable, except for the presence of hypopigmented areas on the right leg and on the trunk and back in a pattern which did not cross the midline (Figure 1). Regarding the family history and examination of family members, similar hypomelanotic lesions had been present in her father since birth, but no other peculiar signs or symptoms were present in her genealogic tree. Her mother, 39-years-old at the time of delivery, was in excellent health. Moreover, there was no family history of congenital nervous or systemic abnormalities. The karyotypic analysis of the peripheral blood cultures of our patient and her father did not reveal any chromosomal anomaly. The karyotypic analysis from fibroblast cultures obtained from a skin biopsy of the hypopigmented area of the father of our patient showed the presence of a trisomy 2 cell line in a 16% mosaic with a normal cell line (karyotype: mos47,XY,+2(15)/46,XY(90); Figure 2). Her parents decided not to authorize the excisional biopsy on their daughter and the fibroblast karyotypic analysis could not be performed.

Figure 1.

Clinical features of two probands. (a and b) right hemisomatic hypopigmented streaks of the trunk and of one leg in our patient; (c and d) small hypopigmented areas on the upper chest in her father.

Figure 2.

Karyotypic analysis from fibroblast cultures obtained from a skin biopsy of the hypopigmented area showing trisomy 2.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge only 15 reports of familial HMI have been described in the current literature (Table 1). HMI may present in both sexes and dominant, recessive and X-linked inheritances have been reported [1-3] as chromosomal aberrations of this rare disorder. HMI may also be transmitted from parent to child with variable presentation and expressivity (Table 1). In the HMI family described by Sacrez et al. and Grosshans et al. [7,8], the mother and her three daughters were all affected. The daughters showed clinical and histopathological cutaneous changes typical of HMI, marked psychomotor retardation, strabismus, hypodontia and skeletal dysplasia. The mother had only non-specific hypopigmented areas. The inheritance in this family with four female individuals suggested an X-linked dominant trait. Cram and Fukuyama described HMI in a child, his mother and his maternal grandfather [9]. Patrizi et al. [10] reported two siblings, a boy and a girl, with typical HMI and neurological symptoms. The mother had typical pigmentary abnormalities without neurological defects [10]. Vormittag et al. [3] reported a family with an affected mother and daughter that was probably consistent with HMI. The mother showed hypopigmentation, eye anomalies, epileptic seizures and skeletal abnormalities. Her daughter displayed hypopigmentation following the lines of Blaschko and eye anomalies [3]. A pair of monozygotic and a pair of dizygotic twins with a patchy and linear hypopigmentation and autism were reported by Zappella [11]. He found that, in the family of the dizygotic twins, the father had three small depigmented spots and the mother had two depigmented streaks [11]. Our familial case showed only skin involvement without systemic alterations. Regarding the association between HMI and systemic features, Nehal et al. suggested that the incidence of associated abnormal features described in previous studies is overstated, and that pigmentary anomalies along the lines of Blaschko are associated with abnormal systemic features less often than previously reported [12]. In their retrospective case series the authors detected that extra-cutaneous abnormal features were present in 16 (30%) of 54 children with aberrant pigmentation along the lines of Blaschko and in particular in only 9 (33%) of 27 with hypomelanosis of Ito. Notably, however, the systemic manifestations can be related to the level of mosaicism in the affected organs. Although we cannot provide evidence of a common origin of the HMI in the father and his daughter in our case report, we postulate that the HMI in the daughter can be due to a rescue of the trisomy 2 zygote. When this is considered, the normal neurologic and systemic development of the young proband allows us to clinically exclude the effects of uniparental disomy (UPD) [13]. It is known that cases of HMI not only show considerable phenotypic variability, but also genotypic variability, with a wide spectrum of chromosomal mosaicisms. A trisomy 2 mosaicism as described in our case report has been reported only once in HMI to the best of our knowledge [14]. The authors described a newborn girl with classic skin findings of HMI with true (postnatal confirmation) trisomy 2 mosaicism. Complete trisomy 2 usually results in first trimester pregnancy losses; trisomy 2 is not fatal only when present in a mosaic style. Cases of infants born live with trisomy 2 mosaicism previously described are characterized by intrauterine growth retardation and multiple congenital systemic anomalies [15]. Due to the finding of different chromosomal aberrations, it has been suggested that HMI does not represent a single condition, but rather a non-specific manifestation of chromosomal mosaicism [4]. Our clinical observations suggest that HMI constitutes a general diagnostic definition that can include different sporadic and/or familial clinical phenotypes characterized by the distribution of hypopigmented streaks along the Blaschko lines.

Table 1.

Reported case of familial hypomelanosis of Ito (HMI)

| Citation | Year | Authors | HMI affected Members | Systemic features | Karyotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] |

1963 |

Masumizu |

Parents |

None |

Not performed |

| [17] |

1969 |

Piñol et al. |

Mother and her daughter |

Myopia, chorioretinal and retinal pigment epithelium atrophy in the right eye |

Not performed |

| [7] |

1970 |

Sacrez et al. |

Mother and three daughters |

Congenital encephalopathy |

Normal (peripheral lymphocytes) |

| |

(performed only in one daughter) |

||||

| [8] |

1971 |

Grosshans et al. |

Mother and three daughters |

Marked psychomotor retardation, strabismus, hypodontia and skeletal dysplasia |

Not performed |

| [18] |

1972 |

Rubin |

Two brothers, sister, father and paternal uncle |

None |

Not performed |

| [19] |

1973 |

Jelinek et al. |

Distant and deceased relatives, paternal great aunt |

Epileptic seizures and strabismus |

Not performed |

| [9] |

1974 |

Cram and Fukuyama |

Child, his mother and his maternal grandfather |

Epileptic seizures |

Not performed |

| [20] |

1975 |

Hellgren |

Mother, sister and brother |

Macrocheilia, iris pigmented spots and hair anomalies |

Not performed |

| [21] |

1975 |

Griffiths and Payne |

Mother and father (first cousins) |

Ocular hypertelorism, nails and fingers anomalies |

Not performed |

| [22] |

1977 |

Schwartz et al. |

Nephew and maternal grandmother |

Epileptic seizures, retardation, macrocephaly, delayed closure anterior fontanelle, leg length discrepancy, scoliosis and iridial heterochromia |

Not performed |

| [10] |

1987 |

Patrizi et al. |

Mother and two sibs |

Neurological symptoms |

Not performed |

| [23] |

1990 |

Amon et al. |

Mother and daughter |

Ocular symptomatology |

Deletion of chromosome 15 |

| |

(peripheral lymphocytes and fibroblasts) |

||||

| [24] |

1991 |

Montagna et al. |

Mother and two sibs |

Mental and cerebellar signs, organic psychosis |

Normal (peripheral lymphocytes) |

| [3] |

1992 |

Vormittag et al. |

Mother and daughter |

Epileptic seizures, ophthalmologic abnormalities, scoliosis and lordosis |

Normal (peripheral lymphocytes) |

| |

Tetraploidy in #2 (23%), #5 (11%), #11 and #14 (6%), #18 and #21 (2%) (fibroblasts) |

||||

| [11] |

1993 |

Zappella |

A pair of monozygotic and a pair of dizygotic twins |

Autism, delayed psychomotor development and microcephaly |

Normal (peripheral lymphocytes) |

| |

2014 | Ponti et al. | Father and daughter | None | Normal (peripheral lymphocytes) |

| Paternal trisomy 2 (fibroblasts) |

Conclusions

Our case remarks the critical role of a careful clinical inspection of all close family members. We therefore suggest the importance of the of apparently innocent and small hypopigmented lesions in order to highlight and demonstrate the presence of a hereditary disorder of pigmentation. Regarding the definition of this peculiar disorder, it is known that the original name incontinentia pigmenti achromians results from the features of the peculiar depigmented changes corresponding to the negative of the morphologic changes characteristic of patients with incontinentia pigmenti [1-3]. However, it is well known that this definition is incorrect, because histologically no incontinent melanin is seen in the dermis, but only a decrease in the number of melanosomes. The most appropriate term hypomelanosis of Ito, pigmentary dysplasia and pigmentary mosaicism are synonyms of the same cutaneous signs. The name Ito syndrome is erroneous as a generic definition of this sporadic condition, and, in our opinion, should be reserved only to familial HMI cases in which the phenotype and the common chromosomal aberrations are documented in at least two first degree-relatives with a systemic involvement of several organs or tissues.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian(s) (including the patient's father) for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

HMI: Hypomelanosis of Ito; ISCN: International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature; UPD: uniparental disomy.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GP, AP and SS are the principal authors and made major contributions to the writing of the manuscript. AT, CR, VDM, KE, PC, CN, MC and GP analyzed and interpreted the patient data and reviewed the literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Giovanni Ponti, Email: giovanni.ponti@unimore.it.

Giovanni Pellacani, Email: pellacani.giovanni@gmail.com.

Aldo Tomasi, Email: aldo.tomasi@unimore.it.

Antonio Percesepe, Email: antonio.percesepe@unimore.it.

Carmelo Guarneri, Email: carmeloguarneri@gmail.com.

Azzurra Guerra, Email: guerra.azzurra@unimore.it.

Victor Desmond Mandel, Email: victor.desmond.mandel@gmail.com.

Elif Kisla, Email: elif_kisla@hotmail.com.

Piril Cevikel, Email: pcevikel@hotmail.com.

Claudia Neri, Email: nclaudia@tiscalinet.it.

Cristina Menozzi, Email: menozzi.cristina@policlinico.mo.it.

Stefania Seidenari, Email: seidenari.stefania@unimore.it.

References

- Ito M. Studies on melanin. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1952;55:1–104. doi: 10.1620/tjem.55.Supplement_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronger S, Till M, Kanitakis J, Balme B, Thomas L. Hypomelanosis of Ito in a girl with Trisomy 13 mosaicism: a cytogenetic study. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130:1033–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vormittag W, Ensinger C, Raff M. Cytogenetic and dermatoglyphic findings in a familial case of Hypomelanosis of Ito (incontinentia pigmenti achromians) Clin Genet. 1992;41:309–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1992.tb03404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggieri M, Pavone L. Hypomelanosis of Ito: clinical syndrome or just phenotype? J Child Neurol. 2000;15:635–644. doi: 10.1177/088307380001501001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery DB, Byrd JR, Freeman WE, Perlman SA. Hypomelanosis of Ito: a cutaneous marker of chromosomal masaicism. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:A93. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Maldonado R, Toussaint S, Tamayo L, Laterza A, del Castillo V. Hypomelanosis of Ito: diagnostic criteria and report of 41 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1992;9:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1992.tb00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacrez R, Gigonnet JM, Stoll C, Grosshans E, Stoebner P. Quatre cas de maladie d'Ito familiale (encephalopathie congenitale et dyschromie): discussion nosologique [English translation: Four cases of familiar Hypomelanosis of Ito (congenital encephalopathy and dyschromia): nosological discussion] Rev Int Ped. 1970;7:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans EM, Stebner P, Bergoend H, Stoll C. Incontinentia pigmenti achromians (Ito) Dermatologica. 1971;142:65–78. doi: 10.1159/000252373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram DL, Fukuyama K. Proceedings: unilateral systematized hypochromic nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:416. doi: 10.1001/archderm.109.3.416b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrizi A, Masina M, Varotti C, Procaccianti G, Baruzzi A, Badiali De Giorgi L. Familial hypomelanosis of Ito. Pediatr Dermatol News. 1987;6:302–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zappella M. Autism and Hypomelanosis of Ito in twins. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1993;35:826–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1993.tb11734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehal KS, PeBenito R, Orlow SJ. Analysis of 54 cases of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation along the lines of Blaschko. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1167–1170. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1996.03890340027005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinzel A, Kotzot D, Brecevic L, Robinson WP, Dutly F, Dauwerse H, Binkert F, Baumer A, Ausserer B. Trisomy first, translocation second, uniparental disomy and partial trisomy third: a new mechanism for complex chromosomal aneuploidy. Eur J Hum Genet. 1997;5:308–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Shah S, Mcgaw A, Mercado T, Zaslav AL, Tegay D. Trisomy 2 mosaicism in hypomelanosis of Ito. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:2466–2468. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sago H, Chen E, Conte WJ, Cox VA, Goldberg JD, Lebo RV, Golabi M. True trisomy 2 mosaicism in amniocytes and newborn liver associated with multiple system abnormalities. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:343–346. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19971031)72:3<343::AID-AJMG18>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masumizu T. Incontinentia pigmenti achromians (Ito) Jpn J Dermatol (Tokyo) Ser B. 1963;73:303. [Google Scholar]

- Piñol J, Mascaró JM, Romaguera C, Asprer J. Considérations sur l'incontinentia pigmenti achromians of Ito: à propos de deux nouveaux cas [English translation: Considerations about Hypomelanosis of Ito: report of two new cases] Bull Soc Franç Dermatol Syphil. 1969;76:533–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin MB. Incontinentia pigmenti achromians. Multiple cases within a family. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:424–425. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1972.01620060062012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek JE, Bart RS, Schiff SM. Hypomelanosis of Ito ("incontinentia pigmenti achromians"). Report of three cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:596–601. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1973.01620190068017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren L. Incontinentia pigmenti achromians (Ito) Acta Derm Venereol. 1975;55:237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A, Payne C. Incontinentia pigmenti achromians. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:751–752. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1975.01630180079010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MF, Esterly NB, Fretzin DF, Pergament E, Rozenfeld IH. Hypomelanosis of Ito (incontinentia pigmenti achromians): a neurocutaneous syndrome. J Pediar. 1977;90:236–240. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(77)80636-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amon M, Menapace R, Kimbauer R. Ocular symptomatology in familial hypomelanosis Ito. Incontinentia pigmenti achromians. Ophtalmologica. 1990;200:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000310069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagna P, Procaccianti G, Galli G, Ripamonti L, Patrizi A, Baruzzi A. Familial hypomelanosis of Ito. Eur Neurol. 1991;31:345–347. doi: 10.1159/000116690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]