Summary

Incidence rates for many cancers differ markedly by race/ethnicity and furthering our understanding of the genetic and environmental causes of such disparities is a scientific and public health need. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are widely acknowledged to provide important information about the etiology of common cancers. To date, these studies have been primarily conducted in European-derived populations. There are important reasons for extending the reach of GWAS studies to other groups and for conducting multiethnic genetic studies involving multiple populations and admixed populations. These include a (1) need to discover the full scope of variants that affect risk of disease in all populations, (2) furthering the understanding of disease pathways, and (3) to assist in fine mapping of genetic associations by exploiting the differences in linkage disequilibrium between populations to narrow the range of marker alleles demarking regions that contain a true biologically relevant variant. Challenges to multiethnic studies relating to study power, control for hidden population structure, imputation, and use of shared controls for multiple cancer endpoints are discussed.

Introduction

The etiology of human cancer is complex and for only a small of number of cancers, such as lung cancer (smoking) and cervical cancer (HPV infection) have risk factors been identified that account for a large fraction of disease in the population [1,2]. For most cancers, our understanding of the environmental constituents, genetic predisposition and the interplay between these etiologic components is far from complete. Varying prevalence of genetic and environmental risk factors is likely to be a major contributor to the observed variation in incidence and mortality of cancer within and across population subgroups; in the U.S., the high incidence rate of colorectal cancer observed among migrant Japanese but not Latinos - populations from host countries with low rates of colorectal cancer - is just one such example that highlights the importance of both genetic and environmental components and their complex interplay underlying disparities in cancer risk [3]. Over the past 4-5 years, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have emerged as a powerful approach to identify risk alleles for common diseases [4-6]. Unfortunately, GWAS in cancer have been limited primarily to populations of European ancestry. Understanding predisposition to cancer across populations will require discovery efforts in diverse populations, including those in subgroups at greatest risk; such studies are likely to be effective in identifying risk alleles that contribute to health disparities.

Race/Ethnicity and Genetics in Cancer Research

Much controversy has been raised about the use of race, ethnicity and ancestry as labels for population groups in health disparities research, in particular studies focused on genetics [7-14]. One's self-reported race/ethnicity captures a multitude of factors, many of which are shared among population subgroups, including social and cultural experiences, beliefs, and customs that impact health outcomes. These labels are also proxies for inheritance of genetic variation, population structure and the historical events (e.g. genetic drift, admixture, and founder effects) that have framed differences in allele frequencies observed between population groups today [15]. Conducting genetic association studies in multiple self-reported groups is clearly logical for addressing the hypothesis of a genetic basis contributing to subgroup differences in disease incidence. Even under a hypothesis that common disease alleles will act substantially similarly (raise or lower risk) in all racial/ethnic groups, many variants will be difficult (or impossible) to find in populations where the alleles are rare. Similarly, some variants are likely to be subgroup specific, thus requiring studies focused on defined populations. Genetic variants may also have different effects in different populations because of unmeasured (and perhaps unknown) environmental risk factors, for which race/ethnicity may be the best proxy, that modify the penetrance of the genetic variant. While, in the near future, studies aimed at discovery of genetic risk factors for cancer will continue to rely on self-reported labels of group membership, in the end it is clear that reducing health disparities will require the comprehensive assessment and dissection of the many biologic (e.g. genetic) and non-biologic correlates of race/ethnicity which are heavily intertwined.

A Genetic Contribution to Cancer Risk Across Populations

Most of what is currently known about genetic susceptibility to cancer has come from studies conducted in populations of European ancestry where large numbers of samples have been more readily obtained. Genetic risk of cancer results from both rare high-penetrant mutations mapped through genetic linkage studies in multiple case families, as well as common and less frequent alleles that contribute more modest risks as revealed through genetic association studies [16,17]. Studies conducted in diverse populations have revealed that both the identity and prevalence of disease-associated variants can vary widely [10]. As examples, founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been reported in specific populations, including those of African, Scandinavian and Jewish ancestry [18]. Common genetic variants at the 8q24 risk locus have been found to be appreciably more frequent in populations of African ancestry than in other groups, and are likely to contribute to the greater incidence of prostate cancer in African American men [19]. Notably, many of the associations observed with common risk variants identified in GWAS conducted in European-derived populations have failed to replicate in other racial/ethnic populations [20-23]. A potential explanation for the lack of generalization includes variable allele frequencies, and thus correlation, of the index signals and biologically relevant variants due to population history. Genetic and environmental modifiers are also likely to vary across populations, which in theory may amplify the signals in some groups more than others. These observations emphasize the importance of conducting detailed genetic investigations in multiple populations; such studies are required to define the complete spectrum of cancer-associated variants in the population and insight into a genetic contribution to disparities in cancer risk.

Leveraging Genetic Background in Studies of Cancer in Diverse Populations

An overwhelming emphasis has been laid on studying European populations for genetic determinants of disease, partly as a matter of convenience and partly as a matter of choice. In particular it has been often assumed that homogeneity in ancestry is a prerequisite to a powerful study free of unexpected levels of false-positive associations. This has lead to many genetic studies of cancer which have excluded minority participants of mixed genetic ancestry even when samples were available, since in most cases the largest single available homogeneous population was of European descent.

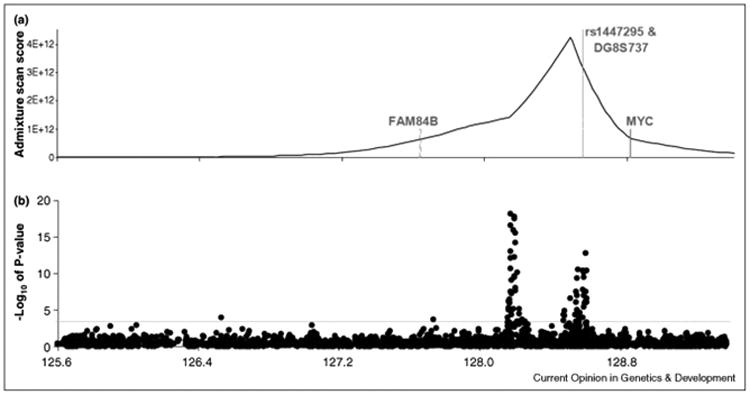

Recently admixed populations can be particularly useful when mapping common risk alleles for cancer that have important frequency differences between ancestral populations. Admixture mapping is a genome-wide scanning approach which seeks regions of the genome that are enriched for a given ancestry among cases with a given phenotype [24,25]. For a given admixed population, markers that vary in frequency between the underlying ancestral groups (i.e. African and European for African Americans) are used to infer local ancestry across the entire genome. Once estimated at each region of the genome, local ancestry is then compared to the genome-wide average of that ancestry for a given individual in search of regions where there is an excess of local ancestry in cases and no similar excess in controls. Genome-wide maps of local ancestry have been assembled and are currently being used for mapping studies in African Americans and Latinos [26,27]. While admixture mapping by itself is not sufficient for fine-mapping associations it can be used to place higher prior probability onto regions enriched for a given ancestry, increasing power to detect risk alleles that are associated with genetic ancestry (and disease) in those regions. This approach has been applied for a limited number of cancers with some success [28,29], and contributed to finding the risk variants for prostate cancer at 8q24 (Figure 1) common in African Americans [19,28]. A number of other cancer sites are suitable candidates for such an approach including multiple myeloma, which is more common in African Americans than European Americans [30]. Formal statistical methods for combing an admixture signal with an association signal are also being developed and implemented [31].

Figure 1.

Multiple risk regions for prostate cancer identified in a multiethnic sample.

Figure adapted from Haiman et al. [19]. A) The location of an ancestry signal at 8q24 from an admixture-based genome-wide scan conducted in African American men. B) Fine-mapping of the putative 8q24 risk locus in prostate cancer cases and controls from five racial/ethnic populations. P-values for each SNP highlight multiple regions harboring common risk alleles for prostate cancer that are defined by independent and highly statistically significant associations.

Incorporating genetic information from multiple different populations also assists in fine-mapping associations at defined risk loci since LD structure has been demonstrated to vary by race/ethnicity [32]. The physical proximity of marker alleles in high LD with an index signal in multiple populations serves as a guide for better defining the region to focus on for functional testing of possible risk alleles. An example is recent work on FGFR2 and breast cancer where fine-mapping in Asian, European and African-Americans around an index risk variant found in Europeans led to better definition of the risk region [33]. Given that a large fraction of the index signals from GWAS fail as pan-ethnic markers of cancer risk, and the observation that many risk loci harbor multiple independent risk alleles [34-36], some for which are population-specific [19], further multiethnic mapping seems appropriate for all risk regions identified in GWAS. Multiethnic mapping will not be productive in localizing alleles that are confined to a single population. However, through simulation studies using HapMap data, Zaitlen et al.[37] have shown an increase in average power by utilizing multiple populations rather than a single population in efforts to localize causal alleles.

Discovery efforts that include multiple racial/ethnic populations offer a broader testing of genetic variation and great power to detect alleles that are common globally (Figure 1). Earlier concerns about the potential for hidden population structure and admixture to induce false positive signals when non-homogeneous populations were under study can be alleviated using either selected ancestry informative SNPs for focused (candidate gene) studies or a larger number of randomly picked SNPs [38]. Principal components [38] and related techniques [39,40] now exist for controlling for differences in ancestry that could in the past bedevil studies of complexly mixed non-homogeneous populations and those that include samples from a range of genetic backgrounds. These methods permit genetic investigations to take advantage of the positive aspects of such studies. For example, standard population genetics models as well as work with real data (e.g. HapMap) shows that allele frequencies differ from population to population [41]. Based on our experience in conducting genetic studies in the Multiethnic Cohort [42], more alleles are common (above a given minor allele frequency) in a multiethnic population than are common in any one population. With very dense testing of common alleles (through genotyping and imputation, discussed below), the biologically relevant alleles should be “tagged” in most, if not all populations, making their overall frequency in the combined study population a primary determinant of the power to detect genetic effects. Moreover, if both allele frequencies and effect sizes (relative risk per allele) vary randomly from population to population, a large fraction of all disease alleles which are present in any population will be “detectable” (at a given probability or power) in a multiethnic study than in a similarly sized study of just one ethnic group. (Here detectability depends on overall allele frequency, effect size, and study sample size.) GWAS that include multiple populations offer great potential.

However, power may be reduced for such an approach if tagging is incomplete or is variable across populations, or for risk alleles that are only common or have detectable effects, perhaps due to modifiers, in defined populations (i.e. genetic heterogeneity).

Statistical and Design Issues of Multiethnic Studies

Control for unreported differences in ancestry is key to successful use of multiethnic and complexly mixed populations in reducing false positive rates (as judged by quantile plots of p-values for randomly chosen SNPs, for example) to acceptable levels. Case-control studies conducted within diverse populations (with cases and controls obtained from each population) can generally control for hidden structure and admixture using principal components methods without appreciable loss of statistical power for detecting an effect of a measured variant, compared to studying a homogeneous population, [38] while gaining the benefits of better fine-mapping of an association signal.

Risk allele discovery and fine-mapping can be enhanced also by the use of imputation of unmeasured alleles based upon LD structure between measured and unmeasured variants [43]. A typical example is the use of large-scale GWAS SNP chips (genotyping between 0.5-1 million SNPs) to impute all (common) SNPs in a reference panel (i.e. phase 2 of HapMap [41]) that have been genotyped for all target and predictor SNPs. For groups of single continental ancestry (Africans, Europeans, Asians) the HapMap phase 2 data provides an appropriate “discovery panel” and imputation has been well-validated as a tool in studies of single populations [44]. The situation for other populations (isolated or admixed) is not quite as well understood. While HapMap phase 3 now provides genotypes for many more populations (including Latinos and African Americans) than in phase 2, the number of common SNPs genotyped in phase 3 is substantially fewer. Increasing the number of SNPs that can be used as targets for imputation and thus, providing more comprehensive genome-wide coverage of common alleles in multiethnic studies is an important issue. One option is to use a “cosmopolitan” discovery panel consisting of data from the source populations (e.g. African and European for African Americans) from phase 2 of HapMap when imputing SNPs for admixed groups [45,46], however further evaluation of such strategies is necessary. Presumably much more will be learned about this problem as the 1000 Genomes Project (http://1000genomes.org) matures.

Another important issue relevant in conducting GWAS in multiethnic samples is the use of existing ethnic-specific genotype data, which can serve as an efficient mechanism to further enhance the statistical power of genetic studies. Numerous studies [47,48] have “reused” genetic data available for European-derived groups in GWAS. There are obvious cost benefits to being able to reuse controls especially in studies of minority groups which are general smaller in number and in sample size. Genetic association studies of a cancer with disparities in incidence by race will be enhanced if statistical methods are in place that will allow those studies to use existing genotype data from minority controls, rather than having to establish new control data sets de novo. Because for complexly mixed populations (e.g. African Americans and Latinos) the degree and sometimes sources of admixture varies according to geographical region within the U.S., reuse of the same control data for many studies of cases (widely distributed geographically) must be analyzed carefully. Some statistical work on this problem has recently been undertaken [49]. Both of these questions (imputation and reuse of controls) may become even more important as studies are now moving towards the (still costly) sequencing of cases and controls in order to deepen the coverage and testing of rarer variation.

Conclusions

GWAS conducted in populations of European ancestry have been highly successful in firmly identifying a number of common genetic variants that convey low risk for cancer (OR<1.5) (reviewed in Easton and Eeles [17]), and in providing clues to new important biological pathways involved in disease pathogenesis. While information from these studies as well as other ongoing scans may one day define the basis for new preventive and therapeutic strategies and play a significant role in shaping personalized cancer preventive and therapeutic medicine, for many researchers, the glass remains more than half-empty [50]. For common cancers, the genetic variants identified to date explain no more than 25% of the heritability (i.e. familial clustering) of the disease (with prostate cancer in the lead) [17], and in aggregate, appear to have only weak discriminative power to predict, with high likelihood, those who will and those who will not develop the disease [51]. Even in European populations, where the vast majority of the discoveries have been made, the clinical utility of this new genetic information is currently quite limited. While it is a misconception to assume that all genetic risk factors for cancer, biological insights and future preventive strategies will be identified through studies conducted solely in populations of European ancestry, assembling large numbers of samples for comparable well-powered genetic studies in non-European populations has been challenging. Consortia are needed, and have formed, to conduct GWAS for a number of cancers in African Americans, including breast, prostate, colorectal and lung cancer, breast cancer in Asians [52], and, similar collaborative coordinated efforts are needed for other sites and racial/ethnic groups. While these scans will provide insight into alleles that may be more relevant to each population (due to allele frequency or effect size), future pooling of data from these scans with those from Europeans will be powerful to reveal variants with pan-ethnic effects that are common globally, but below the level of detection in any one (or perhaps all) populations when examined separately.

The inability of common risk alleles to fully account for disease heritability has resulted in much speculation as to the spectrum of variants that contribute to genetic risk, with rare variants receiving much attention as the culprits (i.e. ‘dark matter’) explaining the missing heritability [53]. It is worth noting however that even if a very large number of rare disease alleles are involved in the heritability of disease susceptibility generally, large differences in risk by race/ethnicity probably are not the result of the cumulative effect of such variants. This is because the sum of the effect of many rare risk alleles with modest penetrance would tend to average out over large groups. It is interesting to note that for prostate cancer, a disease with a profound difference in disease rates between African and European-derived groups (and probably the biggest success story in terms of the fraction of cancer susceptibility due to common variants), a large fraction of this difference in risk between these groups can be accounted for by common risk alleles at the 8q24 locus [19]. Thus, a large fraction of unexplained disease disparities may be due to the action of a relatively few common variants that vary in frequency between populations.

Clearly however if the many rare variants/common disease hypothesis is true it is certain that the spectrum of disease causing variants will be different in each population. Large-scale sequencing studies will soon be mainstream (possibly replacing GWAS studies) and non-European populations ought to be central in these studies. Any given rare disease allele, even if not the cause of population disparities, may be confined to one given racial/ethnic group so that creating a genome-wide census of rare variation affecting risk will necessarily require multiple populations. Both technological and statistical approaches will need to address complexities related to population differences in the spectrum of alleles causing cancer and methods will need to evolve in parallel.

Acknowledgments

CAH and DOS are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA054281, CA098758, CA126895, CA129435, CA136792, HG004726 and HG004802), the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (BC075007A) and the California Breast Cancer Research Program (15UB-8402).

Contributor Information

Christopher A. Haiman, Email: haiman@usc.edu.

Daniel O. Stram, Email: stram@usc.edu.

References

- 1.Alberg AJ, Ford JG, Samet JM. Epidemiology of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132:29S–55S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370:890–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolonel LN, Altshuler D, Henderson BE. The multiethnic cohort study: exploring genes, lifestyle and cancer risk. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:519–527. doi: 10.1038/nrc1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarthy MI, Abecasis GR, Cardon LR, Goldstein DB, Little J, Ioannidis JP, Hirschhorn JN. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:356–369. doi: 10.1038/nrg2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manolio TA, Brooks LD, Collins FS. A HapMap harvest of insights into the genetics of common disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1590–1605. doi: 10.1172/JCI34772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Lander ES. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 2008;322:881–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1156409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sankar P, Cho MK, Condit CM, Hunt LM, Koenig B, Marshall P, Lee SS, Spicer P. Genetic research and health disparities. Jama. 2004;291:2985–2989. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rebbeck TR, Sankar P. Ethnicity, ancestry, and race in molecular epidemiologic research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2467–2471. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rebbeck TR, Halbert CH, Sankar P. Genetics, epidemiology, and cancer disparities: is it black and white? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2164–2169. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ioannidis JP, Ntzani EE, Trikalinos TA. ‘Racial’ differences in genetic effects for complex diseases. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1312–1318. doi: 10.1038/ng1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman AH. Why genes don't count (for racial differences in health) Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1699–1702. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein DB, Hirschhorn JN. In genetic control of disease, does ‘race’ matter? Nat Genet. 2004;36:1243–1244. doi: 10.1038/ng1204-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun L. Reifying human difference: the debate on genetics, race, and health. Int J Health Serv. 2006;36:557–573. doi: 10.2190/8JAF-D8ED-8WPD-J9WH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bamshad M. Genetic influences on health: does race matter? Jama. 2005;294:937–946. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.8.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg NA, Pritchard JK, Weber JL, Cann HM, Kidd KK, Zhivotovsky LA, Feldman MW. Genetic structure of human populations. Science. 2002;298:2381–2385. doi: 10.1126/science.1078311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponder BA. Cancer genetics. Nature. 2001;411:336–341. doi: 10.1038/35077207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Easton DF, Eeles RA. Genome-wide association studies in cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:R109–115. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurian AW. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations across race and ethnicity: distribution and clinical implications. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 22:72–78. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328332dca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **19.Haiman CA, Patterson N, Freedman ML, Myers SR, Pike MC, Waliszewska A, Neubauer J, Tandon A, Schirmer C, McDonald GJ, et al. Multiple regions within 8q24 independently affect risk for prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:638–644. doi: 10.1038/ng2015. This paper demonstrates the benefits of studies of multiple ethnic groups in discovering the scope of variants that affect disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng W, Cai Q, Signorello LB, Long J, Hargreaves MK, Deming SL, Li G, Li C, Cui Y, Blot WJ. Evaluation of 11 breast cancer susceptibility loci in African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2761–2764. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada H, Penney KL, Takahashi H, Katoh T, Yamano Y, Yamakado M, Kimura T, Kuruma H, Kamata Y, Egawa S, et al. Replication of prostate cancer risk loci in a Japanese case-control association study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1330–1336. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Kibel AS, Hu JJ, Turner AR, Pruett K, Zheng SL, Sun J, Isaacs SD, Wiley KE, Kim ST, et al. Prostate cancer risk associated loci in African Americans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2145–2149. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters KM, Le Marchand L, Kolonel LN, Monroe KR, Stram DO, Henderson BE, Haiman CA. Generalizability of associations from prostate cancer genome-wide association studies in multiple populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1285–1289. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith MW, O'Brien SJ. Mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium: advances, limitations and guidelines. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:623–632. doi: 10.1038/nrg1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson N, Hattangadi N, Lane B, Lohmueller KE, Hafler DA, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL, Smith MW, O'Brien SJ, Altshuler D, et al. Methods for high-density admixture mapping of disease genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:979–1000. doi: 10.1086/420871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith MW, Patterson N, Lautenberger JA, Truelove AL, McDonald GJ, Waliszewska A, Kessing BD, Malasky MJ, Scafe C, Le E. A high-density admixture map for disease gene discovery in African Americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1001–1013. doi: 10.1086/420856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price AL, Patterson N, Yu F, Cox DR, Waliszewska A, McDonald GJ, Tandon A, Schirmer C, Neubauer J, Bedoya G, et al. A genomewide admixture map for Latino populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1024–1036. doi: 10.1086/518313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **28.Freedman ML, Haiman CA, Patterson N, McDonald GJ, Tandon A, Waliszewska A, Penney K, Steen RG, Ardlie K, John EM, et al. Admixture mapping identifies 8q24 as a prostate cancer risk locus in African-American men. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14068–14073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605832103. Illustrates successful use of the admixture mapping approach for unearthing the genetic regions that are associated with risk disparities between groups. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fejerman L, Haiman CA, Reich D, Tandon A, Deo RC, John EM, Ingles SA, Ambrosone CB, Bovbjerg DH, Jandorf LH, et al. An admixture scan in 1,484 African American women with breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:3110–3117. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gebregziabher M, Bernstein L, Wang Y, Cozen W. Risk patterns of multiple myeloma in Los Angeles County, 1972-1999 (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:931–938. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **31.Price AL, Tandon A, Patterson N, Barnes KC, Rafaels N, Ruczinski I, Beaty TH, Mathias R, Reich D, Myers S. Sensitive detection of chromosomal segments of distinct ancestry in admixed populations. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000519. Provides a formal approach for estimating local ancestry of small regions of the genome typically in cases of admixed individuals with a phenotype that is correlated with racial origin. Gives a formal procedure for combing the results of admixture mapping and association testing within GWAS studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **32.A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. Gives comprehensive background information on the origin and results of the HapMap project. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **33.Udler MS, Meyer KB, Pooley KA, Karlins E, Struewing JP, Zhang J, Doody DR, MacArthur S, Tyrer J, Pharoah PD, et al. FGFR2 variants and breast cancer risk: fine-scale mapping using African American studies and analysis of chromatin conformation. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1692–1703. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp078. Illustrates the role of fine-mapping in populations with low linkage disequilibrium of GWAS hits found initially in European populations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng SL, Stevens VL, Wiklund F, Isaacs SD, Sun J, Smith S, Pruett K, Wiley KE, Kim ST, Zhu Y, et al. Two independent prostate cancer risk-associated Loci at 11q13. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1815–1820. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun J, Zheng SL, Wiklund F, Isaacs SD, Purcell LD, Gao Z, Hsu FC, Kim ST, Liu W, Zhu Y, et al. Evidence for two independent prostate cancer risk-associated loci in the HNF1B gene at 17q12. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1153–1155. doi: 10.1038/ng.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al Olama AA, Kote-Jarai Z, Giles GG, Guy M, Morrison J, Severi G, Leongamornlert DA, Tymrakiewicz M, Jhavar S, Saunders E, et al. Multiple loci on 8q24 associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1058–1060. doi: 10.1038/ng.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaitlen N, Pasaniuc B, Gur T, Ziv E, Haperin E. Leveraging genetic variability across populations for the identification of causal variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. Outlines the most successful and popular approach to correcting for hidden differences in ancestry in GWAS and other studies. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi Y, Wijsman EM, Weir BS. Case-control association testing in the presence of unknown relationships. Genet Epidemiol. 2009;33:668–678. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rakovski CS, Stram DO. A kinship-based modification of the armitage trend test to address hidden population structure and small differential genotyping errors. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **41.Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Stuve LL, Gibbs RA, Belmont JW, Boudreau A, Hardenbol P, Leal SM, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. Describes the phase 2 HapMap data. The most comprehensive resource available for linkage disequilibrium information in three different continental groups. Updates the Nature 2005 paper with additional analyses and a vast increase in the number of variants considered. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Hankin JH, Nomura AM, Wilkens LR, Pike MC, Stram DO, Monroe KR, Earle ME, Nagamine FS. A multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles: baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:346–357. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **43.Li Y, Willer C, Sanna S, Abecasis G. Genotype imputation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:387–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164242. This and the paper by Marchini et describe the basic ideas behind large-scale genotype imputation for the purpose of enhancing the scope of genetic association studies (see below) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **44.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. Describes one of the most popularly used methods for imputing alleles that are not genotyped based on markers that are in LD with the ungenotyped alleles. In association studies the imputed alleles are then tested for their association with disease thereby enhancing the scope of a fixed genotyping platform, or used to compare the results of two or more GWAS that utilized different platforms with different markers genotyped in each study. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Egyud MR, Gajdos ZK, Butler JL, Tischfield S, Le Marchand L, Kolonel LN, Haiman CA, Henderson BE, Hirschhorn JN. Use of weighted reference panels based on empirical estimates of ancestry for capturing untyped variation. Hum Genet. 2009;125:295–303. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0627-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Bakker PI, Burtt NP, Graham RR, Guiducci C, Yelensky R, Drake JA, Bersaglieri T, Penney KL, Butler J, Young S, et al. Transferability of tag SNPs in genetic association studies in multiple populations. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1298–1303. doi: 10.1038/ng1899. Describes a cosmopolitan approach to conducting comprehensive LD-based association testing of common alleles in multiple ethnic groups. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stacey SN, Manolescu A, Sulem P, Thorlacius S, Gudjonsson SA, Jonsson GF, Jakobsdottir M, Bergthorsson JT, Gudmundsson J, Aben KK, et al. Common variants on chromosome 5p12 confer susceptibility to estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:703–706. doi: 10.1038/ng.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **48.Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. Illustrates the usefulness of sharing control genotype data in association studies conducted among Europeans. Acts as a proof of principle that such studies can detect known and unknown associations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *49.Luca D, Ringquist S, Klei L, Lee AB, Gieger C, Wichmann HE, Schreiber S, Krawczak M, Lu Y, Styche A, et al. On the use of general control samples for genome-wide association studies: genetic matching highlights causal variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.003. Discusses a formal statistical approach for the use of shared control data in genetic association studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldstein DB. Common genetic variation and human traits. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1696–1698. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0806284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kraft P, Hunter DJ. Genetic risk prediction--are we there yet? N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1701–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0810107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng W, Long J, Gao YT, Li C, Zheng Y, Xiang YB, Wen W, Levy S, Deming SL, Haines JL, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new breast cancer susceptibility locus at 6q25.1. Nat Genet. 2009;41:324–328. doi: 10.1038/ng.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, Hunter DJ, McCarthy MI, Ramos EM, Cardon LR, Chakravarti A, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]