Abstract

This project evaluated a web-based multimedia training for primary care providers in screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) for unhealthy use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Physicians (n=37), physician assistants (n=35), and nurse practitioners (n=20) were recruited nationally by email and randomly assigned to online access to either the multimedia training or comparable reading materials. At baseline, compared to non-physicians, physicians reported lower self-efficacy for counseling patients regarding substance use and doing so less frequently. All provider types in both conditions showed significant increases in SBIRT-related knowledge, self-efficacy, and clinical practices. Although the multimedia training was not superior to the reading materials with regard to these outcomes, the multimedia training was more likely to be completed and rated more favorably. Findings indicate that SBIRT training does not have to be elaborate to be effective. However, multimedia training may be more appealing to the target audiences.

Keywords: SBIRT, web-based training, primary care, brief intervention, substance use disorders

1. Introduction

Substance abuse continues to exact an immense toll on American society. It has been estimated that annual costs to the U.S. are over $220 billion due to excessive alcohol consumption (Bouchery, Harwood, Sacks, Simon, & Brewer, 2011) and over $190 billion each due to tobacco use (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011) and illicit drug use (National Drug Intelligence Center, 2011). It is impossible to put a cost on the considerable human suffering due to substance abuse. High rates of unmet need for substance use treatment across all racial and ethnic groups (Mulvaney-Day, DeAngelo, Chen, Cook, & Alegria, 2012) point to the potential benefit of universal screening. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) for substance use problems is a cost-effective, comprehensive, and integrated approach to the delivery of early intervention and treatment services for individuals who use tobacco, alcohol, or other drugs (Babor et al., 2007). In primary care settings, SBIRT has demonstrated efficacy for patients with unhealthy alcohol use (Jonas et al., 2012) and tobacco use (Land et al., 2012) though not for very heavy or dependent drinkers (Saitz, 2010; O'Donnell et al., 2014). While there exists some evidence in support of SBIRT in primary care for patients with unhealthy drug use (Madras et al., 2009), there have been few such trials to date and more studies are needed to examine the efficacy of SBIRT in this population (Saitz et al., 2010; Pilowsky & Wu, 2012). Nonetheless, a consensus group convened by the National Institute on Drug Abuse recently came out in support of providing care for substance use disorders, including risky drug use, in primary care settings (McLellan et al., 2014). Moreover, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that primary care providers (PCPs) routinely screen adult patients for alcohol use and provide brief behavioral counseling interventions to those engaged in risky or hazardous drinking (Moyer, 2013), echoing similar recommendations by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (American Society of Addiction Medicine, 1997), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2007), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2011), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (Levy & Kokotailo, 2011). In addition, the current clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, convened by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as authorized by the U.S. Congress, recommends that clinicians and health-care delivery systems identify and document tobacco use status and use a brief intervention for every tobacco user seen in a healthcare setting (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2009; Fiore et al., 2008).

Despite these recommendations, the provision of SBIRT services in primary care settings is lagging for alcohol (Horgan et al., 2013), tobacco (Tong, Strouse, Hall, Kovac, & Schroeder, 2010), and other drugs (Agley et al., 2014). Knowledge gaps and insufficient access to training in SBIRT for alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs among extant and emerging PCPs are barriers to implementation. For example, recent surveys of medical residents at major medical centers revealed that a majority did not know basic facts about standard drink units (Welsh et al., 2013) and felt unprepared to treat substance use disorders (Wakeman, Baggett, Pham-Kanter, & Campbell, 2013). Similarly, providers at SBIRT implementation demonstration clinics have expressed concerns about the adequacy of their training in preparing them to deliver SBIRT (Broyles et al., 2012; Johnson, et al., 2005; Satre, et al., 2012). Research suggests that training physicians in smoking cessation can increase adherence to PHS guidelines (Caplan, Stout, & Blumenthal, 2011), and training in alcohol screening and brief intervention would appear to hold similar promise (Seale et al., 2013).

A key question is how best to address knowledge and training gaps in support of SBIRT service provision (Gordon & Alford, 2012). As residency training programs are increasingly answering the call to integrate addiction medicine into graduate medication (O'Connor, Nyquist, & McLellan, 2011; Pringle, Kowalchuk, Meyers, & Seale, 2012), continuing medical education (CME) providers can seek to meet similar training needs among established medical professionals, who comprise an audience of considerable size. It was estimated that over 208,000 primary care physicians provided office-based primary care in the United States in 2010 (Petterson et al., 2012). Concurrently, there were estimated to be 56,000 nurse practitioners and 30,000 physician assistants practicing primary care (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2011), with comparable training needs that could potentially be addressed through CME. Although some research suggests that CME consumers prefer live lectures to other formats for continuing medical education (Stancic, Mullen, Prokhorov, Frankowski, & McAlister, 2003), live lectures present logistical challenges and are resource intensive. Online CME consumption has grown considerably over the last decade (Harris, Sklar, Amend, & Novalis-Marine, 2010). While many online CME courses use a text, slide show, or recorded lecture format (Harris et al., 2010), case-based video demonstrations are generally appreciated by users of web-based trainings (e.g., Kemper, Foy, Wissow, & Shore, 2008) and may enhance the effectiveness of teaching of the brief intervention and counseling skills that undergird SBIRT service provision.

Therefore, this project aimed to produce an online, case-based multimedia training program, called SBIRT-PC, to teach knowledge and skills related to SBIRT for alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs to primary care providers, including physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. We conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the educational effectiveness of SBIRT-PC, compared to online provision standard SBIRT training manuals, among PCPs across the U.S. We hypothesized that both online provision of standard SBIRT training materials and SBIRT-PC would be associated with increases in SBIRT-related knowledge, self-efficacy, clinical practice intentions, and self-reported clinical practices, but that training effects would be stronger among those receiving SBIRT-PC than those receiving the reading materials (Hypothesis 1). We also hypothesized that those receiving SBIRT-PC would be more likely to complete the training (Hypothesis 2) and to express greater satisfaction with the training (Hypothesis 3).

2. Materials and Methods

All study methods and materials were approved by Western Institutional Review Board.

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

Physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants were recruited via email. Email announcements were sent through email distribution lists at two local medical centers. In addition, we contracted with two commercial email broadcast service companies that maintain lists of healthcare providers, indexed by type, specialty, and state of practice. The first such recruitment email was sent by a company requiring a minimum of 3000 recipients. Thus, the email was broadcast to 2169 physicians and 831 nurse practitioners or physician assistants; characterized as having an office based practice; living in Washington, Oregon, Alaska, or Idaho; and primarily specializing in family practice, general practice, internal medicine, or obstetrics/gynecology. When this email did not meet recruitment targets, we selected a different company that maintained separate lists of physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners but required a minimum of 3000 recipients of each provider type.

The first recruitment email from the second company was broadcast to 3000 members of the American Medical Association characterized as having an office based practice; specializing in family practice, general practice, internal medicine, or obstetrics/gynecology; and living in Washington, Oregon, Alaska, or Idaho. The second email was broadcast to 3069 members of the American Academy of Physician Assistants specializing in family practice, general practice, internal medicine, or obstetrics/gynecology. It was necessary to increase the number of included states to 25 to reach the minimum number of 3000 recipients (Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Arizona, Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Arkansas, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, Illinois, and Minnesota). The third email was broadcast to 3047 nurse practitioners specializing in primary care, family practice, or obstetrics/gynecology. To reach the minimum number of 3000 recipients, nurse practitioner email addresses were drawn from 6 states (Washington, Oregon, Idaho, California, Nevada, and Arizona).

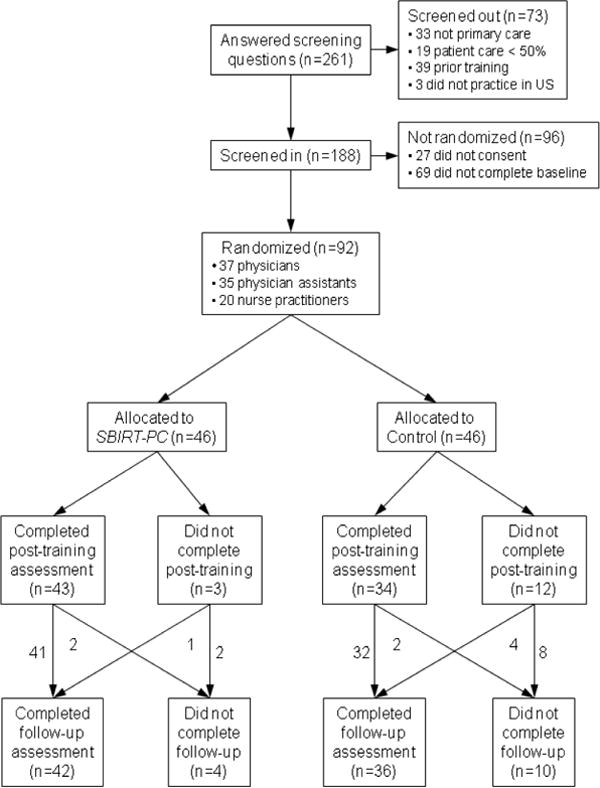

Interested individuals were able to follow a hyperlink in the recruitment email to the study website, where they could complete an eligibility screening. Eligibility criteria required participants to be PCPs who 1) spent 50% or more of their work time providing clinical services in a primary care setting (family practice, general practice, internal medicine or obstetrics/gynecology), 2) practiced in the U.S., and 3) within the past 2 years had not completed training on screening or treatment for substance abuse, other than tobacco. An exception was made for tobacco because we expected that recent provider training in tobacco screening and treatment (particularly nicotine replacement and other pharmacotherapy, promoted by drug companies) would be common. See Figure 1 for number of respondents screened out for each reason.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the randomized trial.

A total of 161 individuals consented to participate in the study. Of those, 142 completed the demographics questionnaire. Ninety-two completed all baseline questionnaires and were randomly assigned to either the experimental training (SBIRT-PC) or the control training (reading materials). The participant flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. Two thirds (67%) of randomized participants were women, 40% were physicians, 38% were physician assistants, and 22% were nurse practitioners. Participants ranged in age from 27 to 65 years, with a mean of 44.6 (SD = 10.8), and ranged in the number of years since residency training from 0 to 37 years, with a mean of 11.4 (SD = 8.3). Seven were resident physicians. Thirteen percent identified as racial minorities and 7% identified as Hispanic. In terms of setting, 40% were reportedly urban, 30%, suburban, and 22% rural. Fifteen states were represented, with multiple providers coming from Washington (39), California (12), Oregon (10), Arizona (8), Texas (6), Idaho (5), Colorado (3), and Illinois (2). One provider hailed from each of the following states: Alaska, Hawaii, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming. On average, participants reportedly 42.5 (SD = 15.5) hours in direct patient care per week. Eighty-seven percent reported prior education or training in tobacco dependence and treatment, 52% did so for substance abuse or addictions, and 30% did so for motivational interviewing. Participants characterized their “training regarding assessment and treatment of substance use problems” as minimal (14%), slight (64%), moderate (20%), or extensive (2%). Similarly, their “experience with addressing substance use problems with patients” was characterized as minimal (6%), slight (42%), moderate (47%), or extensive (6%).

2.2. Procedures

After reading an information statement and agreeing to take part in the study, participants completed baseline questionnaires and were randomly assigned by computer to receive access to either SBIRT-PC (experimental training condition) or to online SBIRT-related reading materials (control training condition). Experimental conditions were balanced according to provider type (physician/physician assistant/nurse practitioner) by the randomization algorithm. Participants were asked to complete the training to which they had been assigned within one week and were given up to 10 days. Participants who had not completed the post-training measures during the 10-day period were sent up to three email reminders were sent. Post-training measures were presented to those randomized to the experimental condition immediately after the last page of the training. Post-training measures were available to those randomized to the control condition immediately after they were randomized; they were asked to return to complete them once they finished the reading materials. All participants who completed post-training questionnaires (n = 77) were compensated $250. Regardless of their post-training completion status, all randomized participants were invited to complete a brief follow-up assessment 90 days later. Those 78 participants completing follow-up questionnaires were compensated $50.

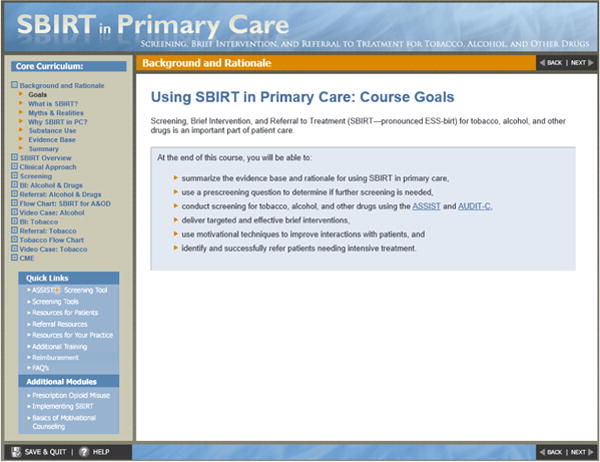

The experimental training and control training presented the same learning objectives (shown in Figure 2). The experimental training was developed first, and the control training was developed to be equivalent in terms of didactic content and visual appeal but different in instructional approach. Both consisted of two modules, the Core Curriculum and Motivational Counseling, which together were accredited for 2.5 prescribed continuing medical education credits by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Consistent with AAFP guidelines, to receive CME credit, participants were required to achieve at least a 75% score on both the 14-item knowledge test for the Core Curriculum and the 5-item knowledge test for Motivational Counseling. Those falling short were permitted to retake the test to earn CME credit, but only the first attempt was used to evaluate post-training knowledge (see Knowledge, under section 2.5 Measures, below).

Figure 2.

Screenshot from SBIRT-PC, showing the learning objectives that were common to both trainings.

2.3. Experimental Training

SBIRT-PC was developed through collaboration between subject matter experts, including physicians and clinical psychologists with a broad range of knowledge spanning primary care, treatment of substance use disorders, and SBIRT interventions, and professional specialists in instructional design, writing, website creation, and multimedia production. An iterative review and editing process was used to determine the final content.

The Core Curriculum module included sections on 1) the background, rationale, and evidence base for SBIRT, 2) the benefit of using an approach consistent with motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), 3) screening tools and procedures, 4) brief intervention and referral for alcohol and other drug use (Henry-Edwards, Humeniuk, Ali, Monteiro, & Poznyak, 2003), and 4) brief intervention and referral for tobacco use (Fiore, et al., 2008). The screening section advocated for the use of the NIDA-Modified Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Test (NM-ASSIST) (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2009) along with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C) (Bradley et al., 2007; Bradley et al., 1998) to provide a comprehensive assessment of substance use and risk level and risk-based recommendations for next steps. Each of the brief intervention and referral sections interwove an audio/video case example with the didactic content and ended with a video case illustrating a brief intervention from start to finish, one relating to alcohol and one relating to tobacco. See Figure 2 for a screenshot. The Motivational Counseling module presented additional information on motivational interviewing, including its definition, spirit, guiding principles, general concepts, and specific techniques. This module also ended with a video case illustrating the use of motivational interviewing techniques with a fictional marijuana user.

2.4. Control Training

The control training was presented as a website containing hyperlinks to downloadable reading materials in PDF format that are available online to the public, including treatment manuals and peer reviewed articles. See Figure 3 for a screenshot. All of the reading materials in the control condition were used as reference materials in the experimental training. Care was taken to ensure that participants in both conditions received comparable breadth and depth of SBIRT-related content. No demonstration videos or other case-related materials were provided in the control training.

Figure 3.

Screenshot from the control training.

2.5. Measures

Measures were selected to be consistent with the Integrated Behavioral Model (IBM, Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2008). In this model, the most proximal determinants of behavior–the primary targets to effect behavior change–are 1) knowledge and skills, 2) salience, 3) intentions, 4) environmental constraints, and 5) habit. Intentions, in turn, are determined by experiential and instrumental attitudes, injunctive and descriptive norms, perceived control, and self-efficacy. The rationale for the creation and evaluation of the SBIRT training in the present study was that poor uptake of SBIRT behaviors has been due to a lack of available training, leaving extant and emergent healthcare providers with relative deficits in knowledge, skills, self-efficacy, and intentions to engage in SBIRT-related behaviors. Therefore, these constructs were explicitly targeted by the training and measured at key time points, as described below.

Self-efficacy (baseline, post-training, follow-up)

Four items were developed to assess self-efficacy for the present study and administered using 5-point scales ranging from -2 = “Strongly Disagree” to 2 = “Strongly Agree,” similar to scales described elsewhere (Garg et al., 2007; Wamsley et al., 2013). Each item began “I feel confident counseling my patients…” and ended with an SBIRT-related topic area. Topic areas included “to quit smoking,” “about their drinking,” “about their abuse of prescription drugs,” and “about their illegal drugs use.”

Clinical practice behaviors (baseline, follow-up)

To assess clinical practice behaviors, relevant questions were adapted from the Preventive Medicine Attitudes and Activities Questionnaire (Murphy, Yeazel, & Center, 2000; Yeazel, Lindstrom Bremer, & Center, 2006) using 5-point scales: 1 = “Never/Rarely, 0-20%,” 2 = “Sometimes, 21-40%,” 3 = “Half time, 41-60%,” 4 = “Often, 61-80%,” and 5 = “Usually/Always, 81-100%”. To assess screening practices, participants were asked, “During the past 90 days, with an adult patient during a periodic health maintenance visit or routine check-up, how often did you do the following…” To assess brief interventions and referral for alcohol and other drug use, participants were asked, “During the past 90 days, when you saw a patient who was drinking heavily, abusing prescription drugs or using illicit substances, how often did you…” To assess brief interventions and referral for tobacco use, participants were asked, “During the past 90 days, when you saw a patient who was a smoker or tobacco user, how often did you…”

Clinical practice behavioral intentions (post-training)

To assess behavioral intentions, the questions adapted from the Preventive Medicine Attitudes and Activities Questionnaire (Murphy et al., 2000; Yeazel et al., 2006) to assess clinical practices were adapted further. Stems were modified to say, “In the upcoming 90 days…how often do you intend to…” Otherwise, the items were the same.

Knowledge (baseline, post-training)

Because we were unable to find a pre-existing valid and reliable measure of SBIRT-related knowledge, multiple choice knowledge questions were developed by the content experts to assess knowledge of the areas addressed in the trainings. Fourteen items were used to assess general knowledge about SBIRT and related clinical practices. Five additional items assessed knowledge about motivational counseling techniques. Please see the Appendix/Supplementary Material for the item content. A score was computed as a sum of the items. As described above, these items were used for the CME tests at post-training. Participants initially falling short of the 75% score required to earn CME credit were permitted to retake the test, but only the first attempt was used to evaluate post-training knowledge.

Training completion

Completing the training was operationalized as completing post-training measures because it was impossible to know objectively whether providers assigned to the reading materials condition did in fact read the materials.

Satisfaction with the training (post-training)

Three satisfaction items were rated a 5-point scale ranging from -2 = “Strongly Disagree” to 2 = “Strongly Agree”: “I enjoyed using the program,” “The material was easy to read and understand,” and “I would recommend this training to my colleagues.”

2.6. Data Analytic Approach

Power analysis

A post-hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted using G*Power 3 software (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2007; Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009). Focusing on the within-between interaction to test Hypothesis 1 using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), with α error probability set to .05 and desired power of .80, given a final sample size of N = 77, the analysis indicated sensitivity to detect an effect size f = .ηequivalent to η2 = .10; Cohen, 1988), corresponding to a medium-to-large effect by convention.

Baseline relationships between prior training and clinical practices

We examined whether there was a relationship between prior training in tobacco dependence and treatment, substance abuse or addictions, and motivational interviewing on the one hand and self-reported baseline clinical practices on the other hand, using point biserial correlations. There were no significant relationships, with one exception; providers who reported prior training in substance abuse or addictions reported more frequently discussing ways for patients to change their substance use (r = .22, p = .034).

Baseline differences between experimental conditions

We examined whether randomization was successful in producing a comparable make-up between conditions at baseline in terms of all of the demographics described in the Recruitment and Participants section above, including prior training, and in terms of baseline scores on the dependent measures. Chi-square and t-tests revealed no significant differences in demographics, and a MANOVA revealed no differences in the baseline measures of dependent variables.

Baseline differences among provider types

Although we did not have any a priori hypotheses based on provider type, we conducted exploratory analyses examining whether provider types differed in terms of baseline scores on the dependent measures. MANOVA revealed a multivariate effect for provider type, Wilks' λ = .36, F(46, 134) = 2.0, p = .002, partial η2 = .40. Means and standard errors are given in Table 1. As shown, at baseline, compared to nurse practitioners, physicians were less confident counseling their patients regarding substance use and reported doing so less frequently.

Table 1. Dependent Variables at Baseline by Provider Type.

| MD/DO (n = 37) | NP (n = 20) | PA (n = 35) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| F(2,89) | p | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | |

| Knowledge test score | 1.84 | .164 | 8.3 | 0.4 | 8.1 | 0.6 | 9.2 | 0.4 |

| Self-efficacy items | ||||||||

| I feel confident counseling my patients to quit smoking | 7.58 | .001 | 0.5a | 0.1 | 1.5b | 0.2 | 1.1b | 0.1 |

| I feel confident counseling my patients about their drinking | 6.77 | .002 | 0.0a | 0.2 | 1.0b | 0.2 | 0.3a | 0.2 |

| I feel confident counseling my patients about their abuse of prescription drugs | 6.46 | .002 | -0.3a | 0.2 | 0.8b | 0.3 | 0.4b | 0.2 |

| I feel confident counseling my patients about their illegal drugs use | 8.80 | .000 | -0.5a | 0.2 | 0.8b | 0.2 | 0.1c | 0.2 |

| Clinical practice items | ||||||||

| During the past 90 days, with an adult patient during a periodic health maintenance visit or routine check-up, how often did you do the following: | ||||||||

| Screen for alcohol abuse or dependence | 0.22 | .803 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 0.3 |

| Screen for misuse of prescriptions drugs | 2.82 | .065 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 0.2 |

| Screen for illicit substance use | 1.12 | .331 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 3.3 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 0.3 |

| Screen for tobacco use | 0.29 | .751 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 4.7 | 0.2 | 4.6 | 0.1 |

| Use a standard validated measure to screen for alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs | 0.95 | .391 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.2 |

| Give patients feedback about screening results | 0.08 | .920 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.3 |

| Ask patients their thoughts about your feedback | 4.57 | .013 | 1.6a | 0.2 | 2.8b | 0.3 | 2.0a | 0.2 |

| During the past 90 days, when you saw a patient who was drinking heavily, abusing prescription drugs or using illicit substances, how often did you | ||||||||

| Describe the harms associated with continued substance use | 4.98 | .009 | 3.6a | 0.2 | 4.5b | 0.3 | 4.2b | 0.2 |

| Give clear advice to quit or cut back | 5.46 | .006 | 3.7a | 0.2 | 4.7b | 0.2 | 4.2b | 0.2 |

| Discuss ways for patients to change their substance use | 4.33 | .016 | 3.1a | 0.2 | 4.2b,c | 0.3 | 3.7a,c | 0.2 |

| Refer those needing specialized treatment | 2.91 | .060 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 0.3 |

| Follow-up with patients about their substance use at their next clinic visit | 3.40 | .038 | 3a | 0.2 | 4.1b,c | 0.3 | 3.5a,c | 0.3 |

| During the past 90 days, when you saw a patient who was a smoker or tobacco user, how often did you | ||||||||

| Advise them to quit | 0.70 | .499 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 4.7 | 0.2 | 4.6 | 0.1 |

| Assess their willingness to quit | 1.04 | .358 | 4.1 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.2 |

| Provide materials about tobacco use and quitting | 2.34 | .103 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 3.3 | 0.3 |

| Prescribe FDA approved medications for smoking cessation, if appropriate | 0.41 | .662 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 3.1 | 0.2 |

| Refer them to a quitline or other form of support | 8.12 | .001 | 2.5a | 0.2 | 4.1b | 0.3 | 3.4b | 0.2 |

| Follow-up with patients about their tobacco use at their next clinic visit | 2.17 | .120 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 3.7 | 0.2 |

Note. For each variable, means marked with different letters are significantly different. MD/DO = physician, NP = nurse practitioner, PA = physician assistant.

Hypothesis testing

Although experimental conditions were balanced by provider type, due to the multiple differences found between provider types at baseline, provider type was used as a covariate in all hypothesis testing. Two dummy variables were created to cover the three provider types: whether the provider was a physician (0, 1) and whether the provider was a nurse (0, 1). In other words, physician assistants were the reference category for the set of dummy variables (both variables equal to zero). To test Hypothesis 1 that increases in SBIRT-related knowledge, self-efficacy, clinical practice intentions, and self-reported clinical practices would be stronger among those receiving SBIRT-PC than those receiving the reading materials, we conducted a series of repeated-measures MANOVAs. The between-subjects factor was condition (intervention, control), and the within-subjects factor was time. To test Hypothesis 2 that those receiving SBIRT-PC would be more likely to complete the training, we conducted a Pearson chi-square test. To test Hypothesis 3 that those receiving SBIRT-PC would express greater satisfaction with the training, we conducted a MANOVA.

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge Test Item Analysis and Scores

Using the Kuder-Richardson approach for dichotomous data (correct/incorrect), internal consistency alpha for the 19 knowledge items was .38 at baseline and .66 at post-training. Item difficulty indices, i.e., the proportion of test takers getting a particular item correct, ranged from .10 to .92 at baseline and from .53 to .96 at post-training. Item discrimination indices, i.e., point biserial correlations between individual items and the sum of the other items, ranged from -.09 to .38 at baseline and from .00 to .51 at post-training.

MANOVA revealed a multivariate main effect for time, Wilks' λ = .62, F(1, 77) = 47.8, p < .001, partial η2 = .38. No other effects or interactions were significant. Collapsing across conditions and covarying out provider type, overall mean scores were 8.6 at baseline, 95% CI [8.0, 9.2], and 13.2 at post-training, 95% CI [12.4, 14.1]. In other words, both conditions showed increases in knowledge from baseline to post-training, with no difference attributable to training type.

3.2. Self-Efficacy

MANOVA examining self-efficacy over the three time points by condition revealed a multivariate main effect for time, Wilks' λ = .57, F(8, 60) = 5.5, p < .001, partial η2 = .42. Univariate tests indicated the effect was significant for each of the self-efficacy items. Means controlling for provider type are shown in Table 2. The physician dummy variable was significant as a covariate, Wilks' λ = .79, F(4, 64) = 4.4, p = .003, partial η2 = .22, but the physician*time interaction term was not significant, indicating that being a physician did not moderate the effect of time, nor did time moderate the effect of being a physician. In general, physicians expressed less self-efficacy for counseling than non-physicians. There were no other significant multivariate effects or interactions.

Table 2. Self-Efficacy and Clinical Practices Over Time, Controlling for Provider Type.

| Baseline | Post-Training | Follow-Up | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| F | df 1 | df 2 | p | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | |

| Self-efficacy items | ||||||||||

| Confidence counseling patients to quit smoking | 9.31 | 1.7 | 114.9 | < .001 | 1.01a | 0.10 | 1.47b | 0.06 | 1.69c | 0.05 |

| Confidence counseling patients about their drinking | 24.70 | 1.7 | 112.1 | < .001 | 0.49a | 0.10 | 1.17b | 0.06 | 1.45c | 0.07 |

| Confidence counseling patients about their abuse of prescription drugs | 10.57 | 1.7 | 114.5 | < .001 | 0.24a | 0.13 | 0.93b | 0.08 | 1.28c | 0.07 |

| Confidence counseling patients about their illegal drugs use | 14.38 | 1.7 | 117.1 | < .001 | 0.11a | 0.12 | 0.87b | 0.10 | 1.28c | 0.07 |

| Clinical practice items | ||||||||||

| Screening for alcohol abuse or dependence | 24.88 | 1.57 | 105.34 | < .001 | 3.3a | 0.2 | 4.6b | 0.1 | 4.6b | 0.1 |

| Screening for misuse of prescriptions drugs | 31.22 | 1.95 | 130.47 | < .001 | 2.2a | 0.2 | 4.2b | 0.1 | 4.0b | 0.1 |

| Screening for illicit substance use | 32.38 | 1.78 | 118.94 | < .001 | 3.1a | 0.2 | 4.3b | 0.1 | 4.4b | 0.1 |

| Screening for tobacco use | 6.44 | 1.54 | 103.46 | .005 | 4.6a | 0.1 | 4.9b | 0.1 | 4.9b | 0.0 |

| Using a standard validated measure for screening | 21.52 | 1.97 | 132.21 | < .001 | 1.6a | 0.1 | 3.6b | 0.2 | 3.1c | 0.2 |

| Giving patients feedback about screening results | 16.88 | 1.85 | 123.94 | < .001 | 2.5a | 0.2 | 4.3b | 0.1 | 4.0b | 0.2 |

| Asking patients their thoughts about the feedback | 52.29 | 1.95 | 130.54 | < .001 | 2.0a | 0.2 | 4.5b | 0.1 | 4.1c | 0.1 |

| Describing the harms associated with continued substance use | 3.86 | 1.88 | 125.91 | .026 | 4.1a | 0.1 | 4.9b | 0.1 | 4.6c | 0.1 |

| Giving clear advice to quit or cut back using the substance | 6.94 | 1.92 | 128.92 | .002 | 4.1a | 0.1 | 4.9b | 0.0 | 4.7c | 0.1 |

| Discussing ways for patients to change their substance use | 11.34 | 1.79 | 120.12 | < .001 | 3.7a | 0.2 | 4.8b | 0.1 | 4.6b | 0.1 |

| Referring those needing specialized treatment for substance use | 9.84 | 1.93 | 129.61 | < .001 | 3.2a | 0.2 | 4.5b | 0.1 | 3.8c | 0.2 |

| Following up with patients about their substance use at the next visit | 13.95 | 1.96 | 131.59 | < .001 | 3.4a | 0.2 | 4.8b | 0.1 | 4.4c | 0.1 |

| Advising tobacco users to quit | 2.89 | 1.77 | 118.49 | .066 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 0.1 |

| Assessing tobacco users' willingness to quit | 10.22 | 1.53 | 102.22 | < .001 | 4.2a | 0.1 | 4.9b | 0.0 | 4.8b | 0.1 |

| Providing materials about tobacco use and quitting | 14.82 | 1.59 | 106.50 | < .001 | 3.1a | 0.2 | 4.7b | 0.1 | 4.2c | 0.1 |

| Prescribing FDA approved medications for smoking cessation | 16.76 | 1.97 | 131.96 | < .001 | 3.0a | 0.2 | 4.4b | 0.1 | 3.8c | 0.2 |

| Referring tobacco users to a quitline or other form of support | 16.45 | 1.83 | 122.49 | < .001 | 3.2a | 0.2 | 4.7b | 0.1 | 4.3c | 0.1 |

| Following up with patients about their tobacco use at the next visit | 15.67 | 1.94 | 129.74 | < .001 | 3.7a | 0.2 | 4.8b | 0.1 | 4.5b | 0.1 |

Note. Degrees of freedom are adjusted using a Greenhouse-Geisser correction for lack of sphericity.

For each variable, means marked with different letters are significantly different.

3.3. Clinical Practices

MANOVA comparing baseline clinical practices to post-training clinical practice intentions to follow-up clinical practices, by condition, revealed a multivariate main effect for time, Wilks' λ = .18, F(36, 32) = 4.1, p < .001, partial η2= .82. Univariate tests indicated the time effect was significant for all of the clinical practice items except screening for tobacco use, which was already high at baseline. Means controlling for provider type are shown in Table 2. There were no other significant multivariate effects or interactions

3.4. Training Completion

As shown in Figure 1, participants randomized to the control condition were significantly less likely to complete the training than those randomized to the SBIRT-PC condition, Pearson X2(1, N = 92) = 6.45, p = .011. There were no differences in training completion by provider type.

3.5. Satisfaction with Training

MANOVA revealed a multivariate main effect for condition, F(3, 71) = 3.3, p = .027, partial η2 = .12. Compared to those in the reading materials control condition, those in the SBIRT-PC condition agreed more strongly that they enjoyed using the program, F(1, 73) = 6.5, p = .013, partial η2 = .08, 95% CIs [0.75, 1.12] vs. [1.15, 1.55], that the material was easy to read and understand, F(1, 73) = 8.6, p = .005, partial η2= .11, 95% CIs [0.66, 1.16] vs. [1.17, 1.62], and that they would recommend the training to their colleagues, F(1, 73) = 8.7, p = .004, partial η2 = .11, 95% CIs [0.80, 1.23] vs. [1.26, 1.67]. The provider type covariates were not significant.

4. Discussion

In this study, we found support for our hypothesis that both standard SBIRT training materials and SBIRT-PC would be associated with increases in SBIRT-related knowledge, self-efficacy, clinical practice intentions, and clinical practices. We did not find support for our hypothesis that effects would be stronger among those receiving SBIRT-PC than those receiving reading materials. Results related to SBIRT knowledge should be interpreted with caution due to the low internal consistency of the measure, especially at baseline. Very low internal consistency at baseline could be at least partially explained by a significant amount of guessing at correct answers, as would be expected by participants who had not yet been exposed to the course material. Since all participants should have been exposed to the course material at post-training, the relatively low internal consistency observed could be reflective of a breadth of items rather than depth of items. Low internal consistency could also be reflective of a poor test with multiple correct answers per item; however, after carefully constructing the items, we do not believe such is the case. Future studies to establish the validity and reliability of these items are warranted.

Initially, compared to nurse practitioners, physicians were less confident counseling their patients regarding substance use and reported doing so less frequently. However, provider type did not moderate changes over time; MDs/DOs, NPs, and PAs self-reported increases in self-efficacy and SBIRT intentions and behaviors to a comparable extent in both conditions. These findings suggest that, to be effective with PCPs from different disciplines, training in SBIRT does not have to be elaborate or complicated; it can be as simple and straightforward as providing links to standard SBIRT training materials and specifying a time frame within which they are to be completed. Experienced primary care providers would appear to possess a solid foundation of clinical knowledge and patient counseling experience into which they can readily assimilate SBIRT training. Case examples and audio and video modeling of the SBIRT process did not enhance providers' learning or change their clinical behaviors, except perhaps in subtle ways that were not detected by the measures examined in the present study. When the bottom line was whether providers changed their practices so as to conduct more SBIRT-related activities, at least according to self-report, the two types of training evaluated in this study had equally strong positive effects.

That an internet-delivered, case-based multimedia training was no more effective than carefully selected PDF files with regard to SBIRT training is not inconsistent with the existing scientific literature. A 2008 meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of internet-based training across a variety of educational outcomes (knowledge, skills, and practices) found large effect sizes compared to no training but only small, nonsigificant effect sizes compared to non-internet based training (Cook et al., 2008). The authors noted, however, that effects varied widely from study to study, which would suggest that there may be certain characteristics associated with more effective internet-based trainings. A subsequent meta-analysis of internet-based training studies found that the more effective internet-based trainings were those that were more interactive (i.e., fostering cognitive engagement beyond online discussion), involved practice exercises, provided feedback, or used repetition (Cook et al., 2010). We expected SBIRT-PC to be more effective than standard reading materials primarily due to its emphasis on illustrative cases and video demonstrations, characteristics that were not examined in the aforementioned meta-analyses, but these characteristics were not associated with enhanced learning or practice change.

The SBIRT-PC training was, however, rated more enjoyable, easier to understand, and more likely to be recommended to colleagues, which may be important with regard to uptake. It is worth noting that participants in both conditions were incentivized to complete the training. Only those completing the training were able to complete the post-training questionnaires and earn $250. Those who did not complete the post-training questionnaires were only able to earn $50 for the follow-up questionnaires. Learners are usually only incentivized to complete trainings in research studies; in practice, incentives are typically not available. When an institution wishes its staff to be trained, an important question is how that institution gets its staff to comply. To that end, enjoyability, accessibility, and peer recommendations may go a long way. Indeed, despite the relatively large incentive for the post-training assessment in the present study, fewer participants assigned to the reading materials control condition completed the post-training assessment than those assigned to SBIRT-PC. The role of learner satisfaction in compliance with workplace continuing education requirements is an area for future study.

In summary, the present study suggests that training in SBIRT increases healthcare providers' provision of SBIRT-related services, at least in the 90 days following training. Important limitations to the present study include the lack of a no-training comparison condition, the relatively short-term follow-up period, and the reliance on self-report methods. It is unknown whether providers' self-reported practices would have changed over time without being provided with training materials, whether self-reported changes persisted beyond 90 days, and whether self-reported changes reflect actual behavioral changes. Because participants in this study were those who responded to an email recruitment campaign, rather than an nationally representative sample, it is unclear to what extent the present results may be generalizable to the broader population of primary care providers in the U.S. Future studies should examine these issues in addition to investigating whether SBIRT training improves patient-oriented outcomes, such as the percentage of patients being identified as having a substance-use disorder or the percentage receiving care for these disorders, compared to an education-as-usual control group.

Acknowledgments

This research, including the development of SBIRT-PC, was supported with federal funding under Small Business Innovation Research contract HHSN271200900035C from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services to Talaria, Inc. We thank John Baer, Ph.D., Beatriz Carlini, Ph.D., Paul Gianutsos, M.D., M.P.H., Megan Rutherford, Ph.D., and Molly Carney, Ph.D., for their assistance in the development of SBIRT-PC. As current or former employees of Talaria, Inc., we report that we have no conflicts of interest affecting the evaluation of SBIRT-PC as none of us holds an equity position in Talaria, Inc., or otherwise stands to benefit financially from SBIRT-PC.

Appendix/Supplementary Material

SBIRT and MI Knowledge Test Items

- All of the following are true of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) except:

- SBIRT provides an opportunity to reinforce positive health behaviors

- SBIRT is intended to identify patients with mild to severe substance use problems

- SBIRT requires that physicians provide specialized substance abuse treatment services*

- SBIRT is effective for patients abusing multiple substances

- Brief interventions have been shown to:

- Increase the likelihood patients will cut back on their tobacco and alcohol use

- Increase the likelihood patients will cut back on their cocaine and heroin use

- Both A and B*

- None of the above

- All of the following are true about the ASSIST (Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test) EXCEPT:

- The ASSIST screens for recent use rather than lifetime use*

- The ASSIST assesses multiple substance categories

- The ASSIST is able to discriminate among low, moderate, and high risk substance use

- The ASSIST has been validated in both primary and specialty care settings

- Of the following combinations of instruments, which would provide the most comprehensive picture of a patient's substance use?

- The CAGE and the CAGE-AID

- The MAST and the DAST

- The AUDIT and the DUDIT

- The ASSIST and the AUDIT-C*

- The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute of Drug Abuse recommend that primary care screening for alcohol and substance use should occur:

- At every visit with every patient

- Annually with every patient*

- At every visit with patients aged 16-45; annually with patients of other ages

- Semi-annually with patients suspected of alcohol or other drug use

- Compared to patient self-report via standardized instruments such as the ASSIST and AUDIT-C, urine drug screens:

- Provide more valid and reliable information about substance use

- Provide more sensitivity and specificity when it comes to diagnosing substance use disorders

- Both A and B

- Neither A nor B*

- When it comes to introducing the screening process, normalizing the discussion refers to:

- Letting patients know that inquiring about substance use is a routine part of an office visit*

- Reassuring patients that it's OK to be truthful because substance use is very common

- Both A and B

- Neither A nor B

- Brief interventions are often sufficient treatment for:

- Everyone

- Patients with only mild substance use problems

- Patients with mild to moderate substance use problems*

- No one—a BI is only the first step in a larger intervention

- The three key steps in completing brief interventions are, in order:

- Introduction, feedback, advice

- Feedback, advice, menu of options*

- Advice, referral, summary

- Feedback, referral, follow-up

- The right attitude can increase patients' willingness to change and decrease defensiven Attitudes should express:

- An understanding that addiction is a disease

- Belief that the patient can change*

- A commitment to abstinence as the ultimate goal

- Acknowledgement that substance use can impair a person's judgment

- All of the above

- When providing feedback:

- Maintain a warm, empathetic, and nonjudgmental tone

- Work quickly to minimize defensiveness

- Remind patients of the purpose of giving feedback

- Describe the range of possible screening results

- Note that any drug use is extremely dangerous

- Describe where the patient falls on the range compared to others

- A, C, E

- A, C, D, F*

- B, C, D, E

- After giving advice, we suggest the provider offer a menu of options that can support patients making changes. Why offer options?

- It demonstrates that there's more than one path towards abstinence

- It comforts the patient to know there are others with similar problems

- It gives the patient an opportunity to respond to the provider's interpretation of the screening results

- It communicates that the patients is responsible for making choices*

- All of the above

- All of the following medications are approved by the FDA to support relapse prevention for alcohol use disorder EXCEPT:

- Naltrexone

- Varenicline*

- Disulfiram

- Acamprosate

- Research shows that medical advice to quit tobacco increases the chances that a smoker will make a quit attempt and successfully quit. This advice should be clear, strong and personal, express confidence and be nonjudgmental and empathic. What does personal advice mean?

- It means mentioning providers' personal experiences with treating other smokers.

- It means sharing personal struggles of self, family and significant others with tobacco.

- It means linking the patient's tobacco use to the reason for the office visit.*

- None of the above.

- The spirit of MI can be characterized by all of these concepts except:

- Collaboration

- Depth of feeling*

- Respect for patient autonomy

- Evocation

- The “righting reflex” is a reaction that some clinicians may have when trying to help their patients. Which of these statements about the righting reflex is true?

- It keeps the discussion from getting heated.

- It is never functional.

- It is based in a provider's need to control a situation.

- It can make change less likely when patients are unsure about change.*

- Change talk includes the following types of speech except:

- Difficulties of change*

- Reasons for change

- Desire to change

- Commitment to change

- Ability to change

- What should clinicians do to elicit change talk when using MI?

- Use open and closed questions.

- Reflect what they hear.*

- De-emphasize change language they hear.

- All of the above

- When giving advice, MI suggests each of the following strategies except:

- Make it direct to minimize confusion.*

- Ask permission first.

- Ask first what patient already knows.

- Ask what patient thinks of advice once provided.

- Provide multiple options.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Susan A. Stoner, Talaria, Inc., Seattle, Washington; now affiliated with the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

A. Tasha Mikko, Talaria, Inc., Seattle, Washington; now at the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, Seattle, Washington

Kelly M. Carpenter, Talaria, Inc., Seattle, Washington; now at Alere Wellbeing, Seattle, Washington

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2011. Oct, [Accessed February 2, 2014]. The number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants practicing primary care in the United States: Primary care workforce facts and stats. at http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/primary/pcwork2/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Agley J, McIntire R, DeSalle M, Tidd D, Wolf J, Gassman R. Connecting patients to services: Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment in primary health care. Drugs: education, prevention and policy. 2014;(0):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 496: At-risk drinking and alcohol dependence: obstetric and gynecologic implications. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):383–388. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822c9906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Policy Statement on Screening for Addiction in Primary Care Settings. American Society of Addiction Medicine; Chevy Chase, MD: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, McRee BG, Kassebaum PA, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, Bray J. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Substance Abuse. 2007;28(3):7–30. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41(5):516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcoholism: Clinical and Expermental Research. 2007;31(7):1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, McDonell MB, Bush K, Kivlahan DR, Diehr P, Fihn SD. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcoholism: Clinical and Expermental Research. 1998;22(8):1842–1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyles LM, Rodriguez KL, Kraemer KL, Sevick MA, Price PA, Gordon AJ. A qualitative study of anticipated barriers and facilitators to the implementation of nurse-delivered alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for hospitalized patients in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2012;7(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan L, Stout C, Blumenthal DS. Training physicians to do office-based smoking cessation increases adherence to PHS guidelines. J Community Health. 2011;36(2):238–243. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9303-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use: Targeting the nation's leading killer, at a glance, 2011. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Internet-based learning in the health professions: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1181–1196. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Instructional design variations in internet-based learning for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Academic Medicine. 2010;85(5):909–922. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d6c319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Serwint JR, Higman S, Kanof A, Schell D, Colon I, Butz AM. Self-efficacy for smoking cessation counseling parents in primary care: an office-based intervention for pediatricians and family physicians. Clinical Pediatrics. 2007;46(3):252–257. doi: 10.1177/0009922806290694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AJ, Alford DP. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) curricular innovations: addressing a training gap. Substance Abuse. 2012;33(3):227–230. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.640156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JM, Sklar BM, Amend RW, Novalis-Marine C. The growth, characteristics, and future of online CME. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2010;30(1):3–10. doi: 10.1002/chp.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry-Edwards S, Humeniuk R, Ali R, Monteiro M, Poznyak V. Brief intervention for substance use: A manual for use in primary care (Draft Version 1.1 for Field Testing) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan CM, Garnick DW, Stewart MT, Hodgkin D, Reif S, Quinn A, et al. Provider payment approaches and incentives to implement screening. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice. 2013;8(Suppl 1):A34. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-8-S1-A34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TP, Booth AL, Johnson P. Physician beliefs about substance misuse and its treatment: Findings from a U.S. survey of primary care practitioners. Substance Use and Misuse. 2005;40:1071–1084. doi: 10.1081/JA-200030800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, Brown JM, Brownley KA, Council CL, Harris RP. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;157(9):645–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper KJ, Foy JM, Wissow L, Shore S. Enhancing communication skills for pediatric visits through on-line training using video demonstrations. BMC medical education. 2008;8(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land TG, Rigotti NA, Levy DE, Schilling T, Warner D, Li W. The effect of systematic clinical interventions with cigarette smokers on quit status and the rates of smoking-related primary care office visits. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SJ, Kokotailo PK. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1330–1340. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, Stegbauer T, Stein JB, Clark HW. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;99(1):280–295. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Starrels JL, Tai B, Gordon AJ, Brown R, Ghitza U, McNeely J. Can substance use disorders be managed using the Chronic Care Model? Review and recommendations from a NIDA consensus group. Public Health Reviews. 2014;35(2):2107–6952. doi: 10.1007/BF03391707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Montaño DE, Kasprzyk D. Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior, and the Integrated Behavioral Model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 67–95. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer VA. Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions in Primary Care to Reduce Alcohol Misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney-Day N, DeAngelo D, Chen CN, Cook BL, Alegria M. Unmet need for treatment for substance use disorders across race and ethnicity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125(Suppl 1):S44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KA, Yeazel M, Center BA. Validity of residents' self-reported cardiovascular disease prevention activities: the Preventive Medicine Attitudes and Activities Questionnaire. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31(3):241–248. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Drug Intelligence Center. The economic impact of illicit drug use on American society. Washington, DC: National Drug Intelligence Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician's Guide. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor PG, Nyquist JG, McLellan AT. Integrating addiction medicine into graduate medical education in primary care: the time has come. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;154(1):56–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell A, Anderson P, Newbury-Birch D, Schulte B, Schmidt C, Reimer J, et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2014;49(1):66–78. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker GD, Libart D, Higgs T, Schrader S, McCollom B, Fanning L, Dixon J. SBIRT in primary care: The struggles and rewards. Journal of Addictive Behaviors, Therapy & Rehabilitation. 2013;2(1):1–4. doi: 10.4172/2324-9005.1000104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10(6):503–509. doi: 10.1370/afm.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT. Screening for alcohol and drug use disorders among adults in primary care: a review. Substance abuse and rehabilitation. 2012;3(1):25–34. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S30057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle JL, Kowalchuk A, Meyers JA, Seale JP. Equipping residents to address alcohol and drug abuse: The national SBIRT residency training project. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2012;4(1):58–63. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00019.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care: Absence of evidence for efficacy in people with dependence or very heavy drinking. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2010;29(6):631–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Alford DP, Bernstein J, Cheng DM, Samet J, Palfai T. Screening and brief intervention for unhealthy drug use in primary care settings: randomized clinical trials are needed. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2010;4(3):123–130. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181db6b67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, McCance-Katz EF, Moreno-John G, Julian KA, O'Sullivan PS, Satterfield JM. Using needs assessment to develop curricula for screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in academic and community health settings. Substance Abuse. 2012;33(3):298–302. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.640100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale JP, Clark DC, Dhabliwala J, Miller D, Woodall H, Shellenberger S, Johnson JA. Impact of motivational interviewing-based training in screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment on residents' self-reported attitudes and behaviors. Addiction science & clinical practice. 2013;8(Suppl 1):A71. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-8-S1-A71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Systems-Level Implementation of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment Technical Assistance Publication (TAP) Series 33 HHS Publication No (SMA) 13-4741. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stancic N, Mullen PD, Prokhorov AV, Frankowski RF, McAlister AL. Continuing medical education: what delivery format do physicians prefer? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2003;23(3):162–167. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340230307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong EK, Strouse R, Hall J, Kovac M, Schroeder SA. National survey of U.S. health professionals' smoking prevalence, cessation practices, and beliefs. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(7):724–733. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. [Retrieved May 19, 2014];Counseling and Interventions to Prevent Tobacco Use and Tobacco-Caused Disease in Adults and Pregnant Women. 2009 Apr; from http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstbac2.htm.

- Wakeman SE, Baggett MV, Pham-Kanter G, Campbell EG. Internal medicine residents' training in substance use disorders: a survey of the quality of instruction and residents' self-perceived preparedness to diagnose and treat addiction. Substance Abuse. 2013;34(4):363–370. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.797540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamsley MA, Julian KA, O'Sullivan P, Satterfield JM, Satre DD, McCance-Katz E, Batki SL. Designing standardized patient assessments to measure SBIRT skills for residents: A literature review and case study. Journal of Alcohol & Drug Education. 2013;57(1):46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh C, Earley K, Delahanty J, Wright KS, Berens T, Williams AA, DiClemente CC. Residents' knowledge of standard drink equivalents: Implications for screening and brief intervention for at-risk alcohol use. American Journal on Addictions. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12080.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeazel MW, Lindstrom Bremer KM, Center BA. A validated tool for gaining insight into clinicians' preventive medicine behaviors and beliefs: the preventive medicine attitudes and activities questionnaire (PMAAQ) Preventive Medicine. 2006;43(2):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]